↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) excel at complex tasks but falter on simple logical reasoning, a phenomenon known as the ‘reversal curse.’ This means they struggle to infer ‘B ← A’ even after learning ‘A → B,’ hindering their ability to solve problems requiring reversed logical steps. This limitation poses a significant challenge, as it affects the models’ ability to generalize and hinders their real-world application. Existing solutions involve modifying the dataset or architecture, impacting other functionalities.

This paper addresses the reversal curse by providing a theoretical explanation through the lens of training dynamics. Using two auto-regressive models (a simplified one-layer transformer and a bilinear model), the researchers show that weight asymmetry—an imbalance in how strongly the model connects ‘A’ to ‘B’ versus ‘B’ to ‘A’—underlies the problem. This analysis opens up new research directions focusing on training methods that promote weight symmetry, potentially leading to more robust and logically sound LLMs. The research also extends this framework to explain chain-of-thought prompting and its importance in overcoming limitations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it offers a novel theoretical understanding of the reversal curse, a significant limitation in large language models. By analyzing training dynamics, it identifies weight asymmetry as the root cause and suggests new avenues for model improvement and enhancing logical reasoning capabilities. This will impact the design of future LLMs focusing on improved reasoning and generalization. It also provides a new perspective on chain-of-thought prompting.

Visual Insights#

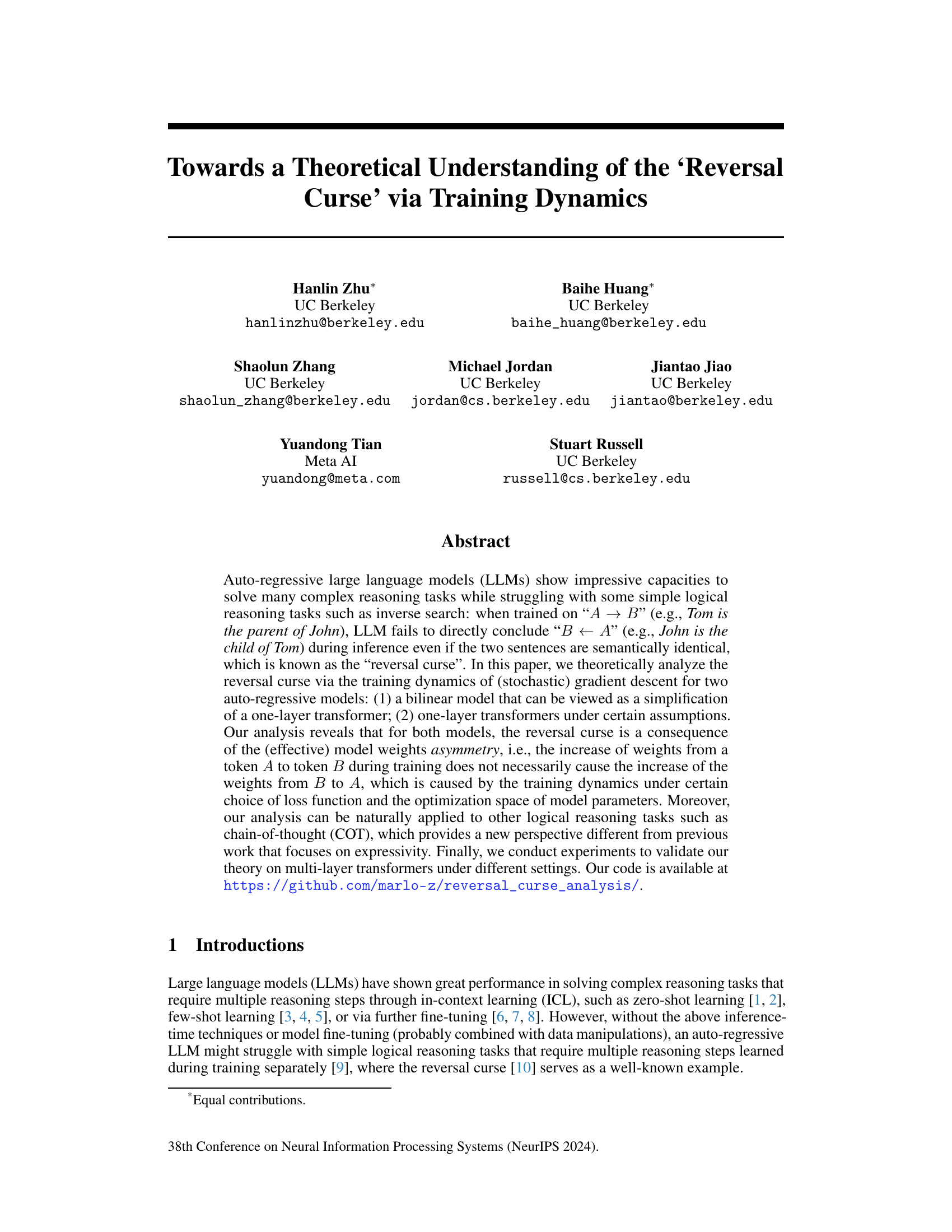

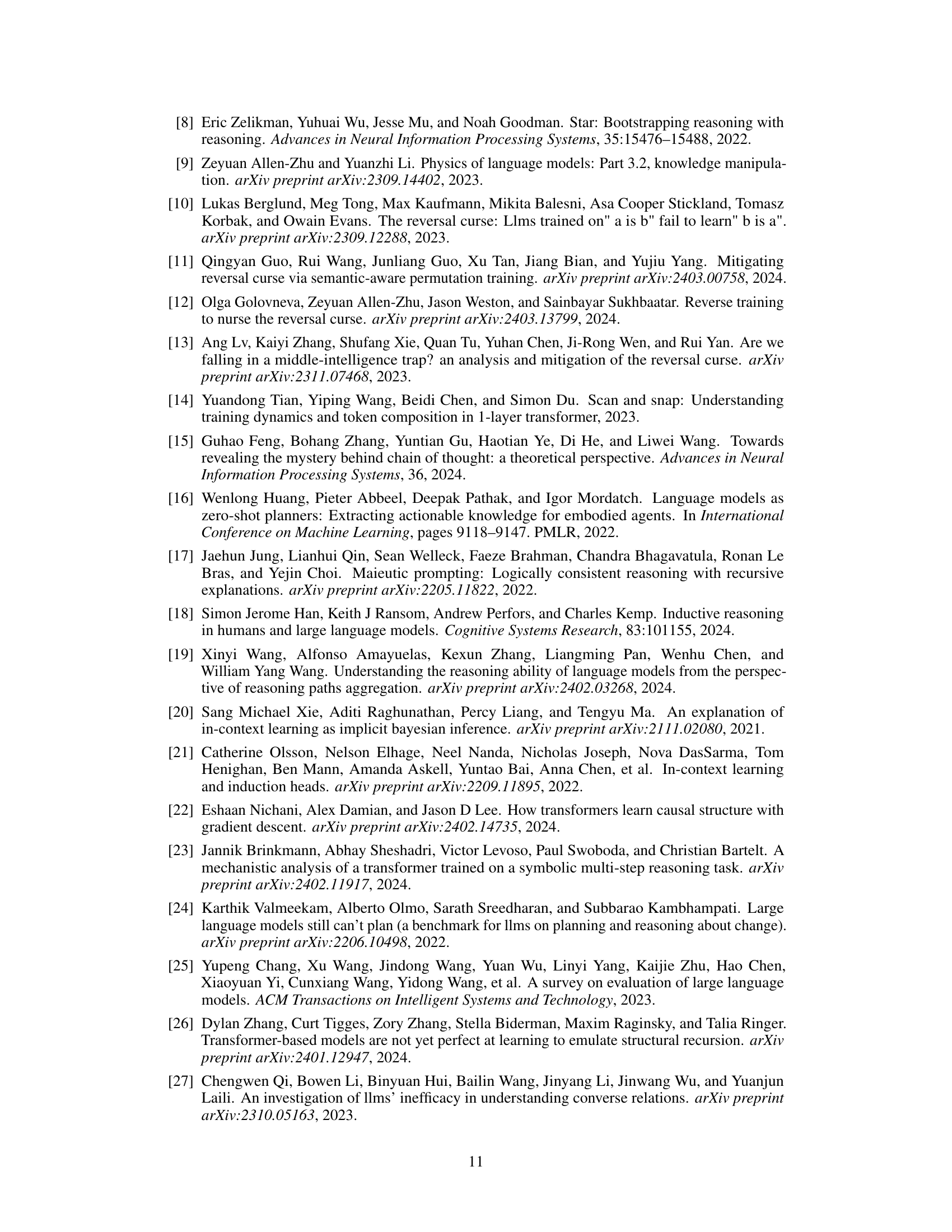

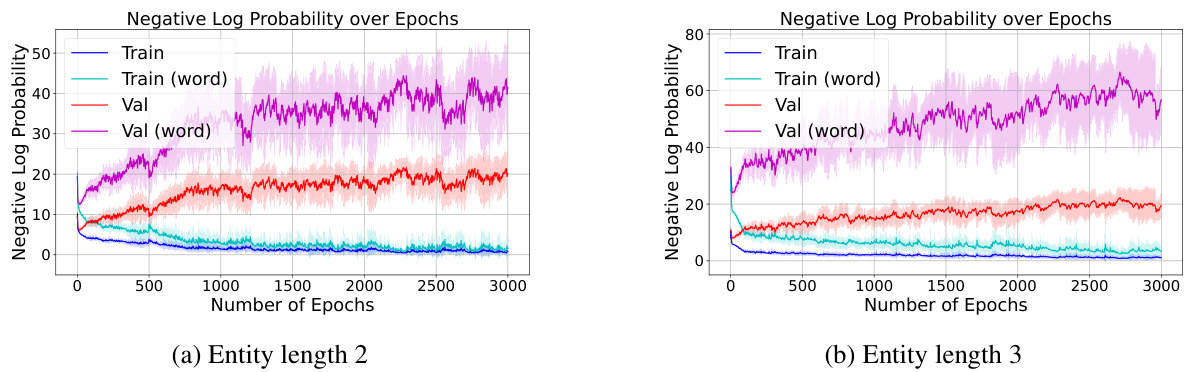

This figure shows the training and validation loss for a model trained on a reversal curse task. The training loss decreases sharply, indicating the model learns the forward relationship well. However, the validation loss remains high, showing the model fails to generalize to the reversed relationship. This demonstrates the reversal curse phenomenon.

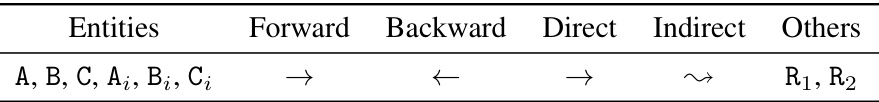

This table lists notations used for different types of tokens in Section 4 of the paper. It clarifies the meaning of symbols representing entities, forward/backward relationships (relevant to the ‘reversal curse’ phenomenon), and direct/indirect implications (relevant to Chain-of-Thought reasoning).

In-depth insights#

Reversal Curse Analysis#

Analyzing the “reversal curse” in large language models (LLMs) involves examining why models struggle to infer “B ← A” after training on “A → B”, even when the relationship is semantically identical. A key aspect is the asymmetry of model weights: simply increasing weights from A to B doesn’t guarantee increased weights from B to A. This highlights that LLMs don’t learn bidirectional relationships automatically, even with semantically equivalent statements. This asymmetry is linked to the training dynamics and the chosen loss function (often cross-entropy). Another crucial factor is the model’s architecture, particularly the autoregressive nature which inherently processes information sequentially. Analyzing different models (like bilinear models and one-layer transformers) can help dissect the impact of architectural choices on the reversal curse. Ultimately, this analysis reveals limitations in how LLMs learn logical relationships, suggesting a need for techniques like chain-of-thought prompting to explicitly guide the model’s reasoning process and overcome this inherent limitation. Understanding the curse necessitates a deeper dive into the training dynamics and weight matrices, providing valuable insights for improving LLM reasoning capabilities.

Training Dynamics#

Analyzing the training dynamics of large language models (LLMs) is crucial to understanding their capabilities and limitations. The paper investigates how the training process shapes the model’s weights, leading to phenomena like the ‘reversal curse’ where the model struggles to infer the inverse of a learned relationship. The authors analyze the dynamics for different models, such as bilinear models and one-layer transformers, and reveal that weight asymmetry, caused by training dynamics and loss function choices, is a key factor. This asymmetry implies that an increase in weights for ‘A → B’ doesn’t guarantee an increase for ‘B ← A’, explaining the reversal curse. The analysis also extends to other logical reasoning tasks like chain-of-thought (COT), providing a new perspective on their behavior. Importantly, empirical validation on multi-layer transformers supports the theoretical findings. The focus on training dynamics is a valuable contribution because it offers insights beyond mere expressivity analysis, providing a deeper understanding of LLM behavior and highlighting the importance of carefully designed training processes.

Bilinear Model Study#

A bilinear model study in the context of a research paper on the reversal curse in large language models (LLMs) would likely involve simplifying the LLM architecture to a basic bilinear form to make the model’s training dynamics more tractable for theoretical analysis. This simplification allows for a mathematical examination of how gradient descent, the typical training algorithm, updates the model’s weights during training. The focus would be on understanding how weight asymmetry arises, which is a central finding in many reversal curse studies. The analysis would likely demonstrate that weight updates from token A to token B don’t automatically lead to reciprocal updates from B to A, despite the semantic equivalence between the forward and reverse statements. This asymmetry directly causes the LLM to struggle with inferring the reverse logical relationship during inference, exhibiting the reversal curse. The bilinear model, with its reduced complexity, allows researchers to precisely pinpoint the impact of training dynamics and loss function choice in creating this asymmetry and provides a clear theoretical explanation for the empirical observation of the reversal curse. This study’s value would come from providing a foundational understanding that can then be extended to more complex models, offering a more generalizable theoretical framework to explain this phenomenon in LLMs.

Transformer Dynamics#

Analyzing transformer dynamics involves exploring how the model’s internal parameters evolve during training. Gradient descent, the primary optimization method, shapes the weight matrices, which in turn dictate the model’s attention mechanism and ability to learn complex patterns. Understanding this evolution helps to uncover why transformers exhibit specific behaviors, such as the reversal curse (difficulty inverting learned relationships) or their proficiency in chain-of-thought reasoning. By examining weight asymmetries and intransitivity, we gain insights into the model’s capacity for logical reasoning. Analyzing specific loss functions (such as cross-entropy) and optimization spaces further refine our understanding of these dynamics. Furthermore, model simplification (e.g., using bilinear models) allows for more tractable theoretical analysis, providing valuable insights which can be extended to more complex architectures. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of transformer dynamics is crucial for improving model design, addressing limitations, and enhancing their reasoning capabilities.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could involve extending the theoretical analysis to multi-layer transformers, moving beyond the simplified models used here. Investigating the impact of different architectural choices, such as the type of attention mechanism or the use of residual connections, on the reversal curse is crucial. A deeper exploration into the interaction between training dynamics and model expressivity is also needed, potentially combining these analyses to provide a more holistic understanding. Exploring different loss functions beyond cross-entropy and examining their effects on model weight asymmetry could yield valuable insights, as could exploring the influence of various regularization techniques on the reversal curse. Furthermore, investigating the reversal curse in other autoregressive models and diverse tasks such as question answering or text summarization could broaden the scope of the findings. Finally, developing mitigation strategies for the reversal curse and empirically evaluating their effectiveness in complex reasoning scenarios presents an important practical direction for future work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

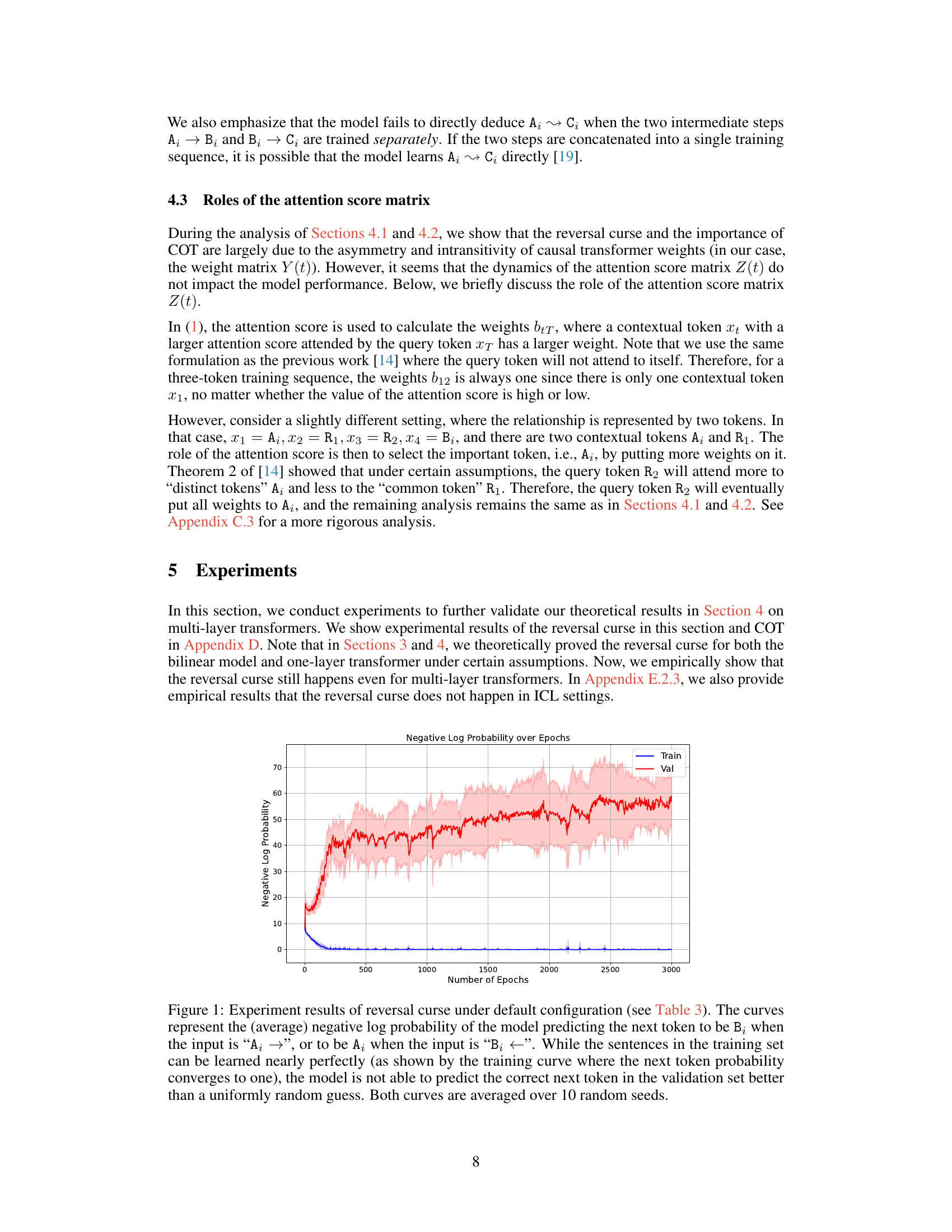

This figure visualizes the weights (logits) of a model trained on a reversal curse task. The heatmaps show the model’s learned weights for predicting a token given another token, differentiating between training and validation data, and seen vs. unseen directions. The diagonals of the matrices highlight the asymmetry: strong weights in the seen direction during training but weak weights in the reverse direction and in unseen validation data.

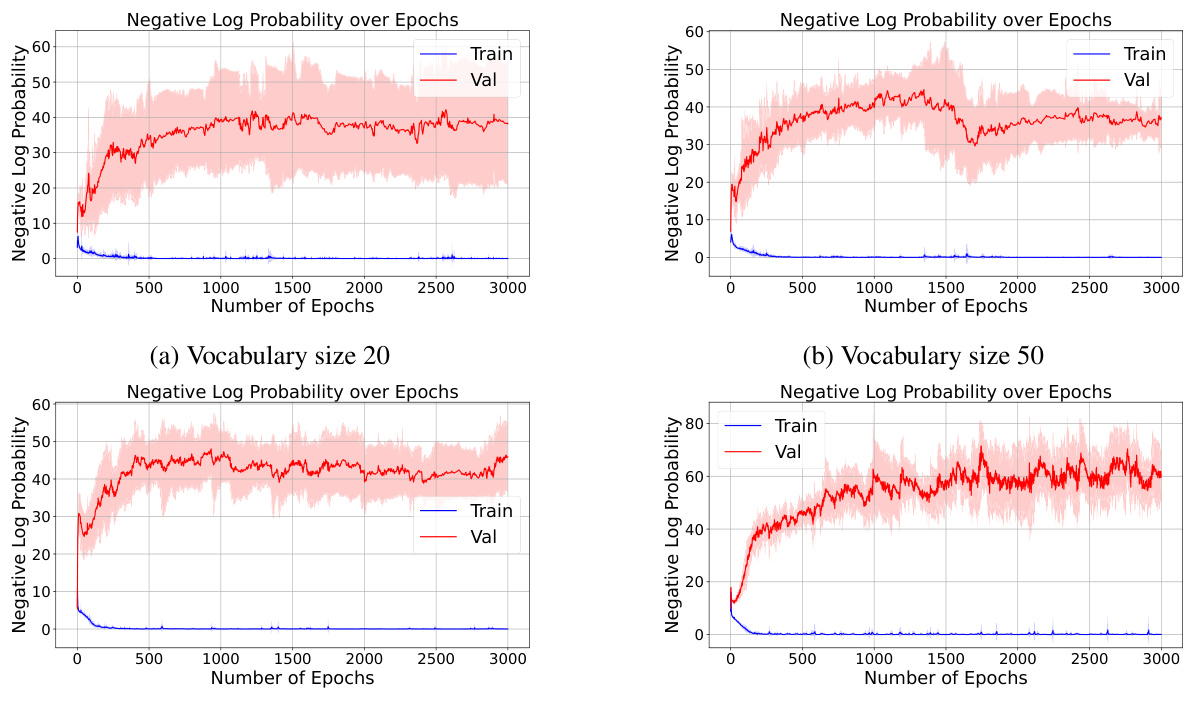

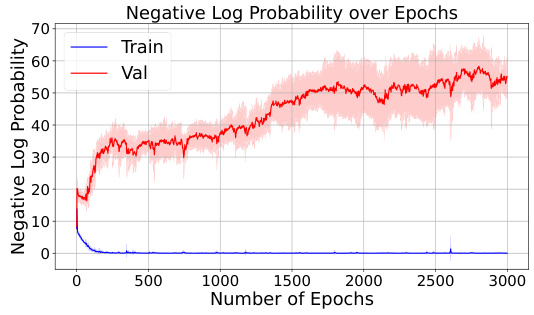

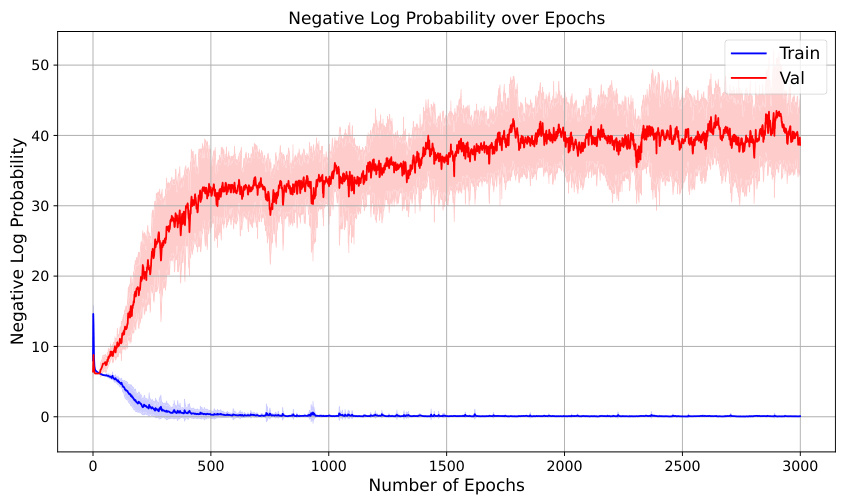

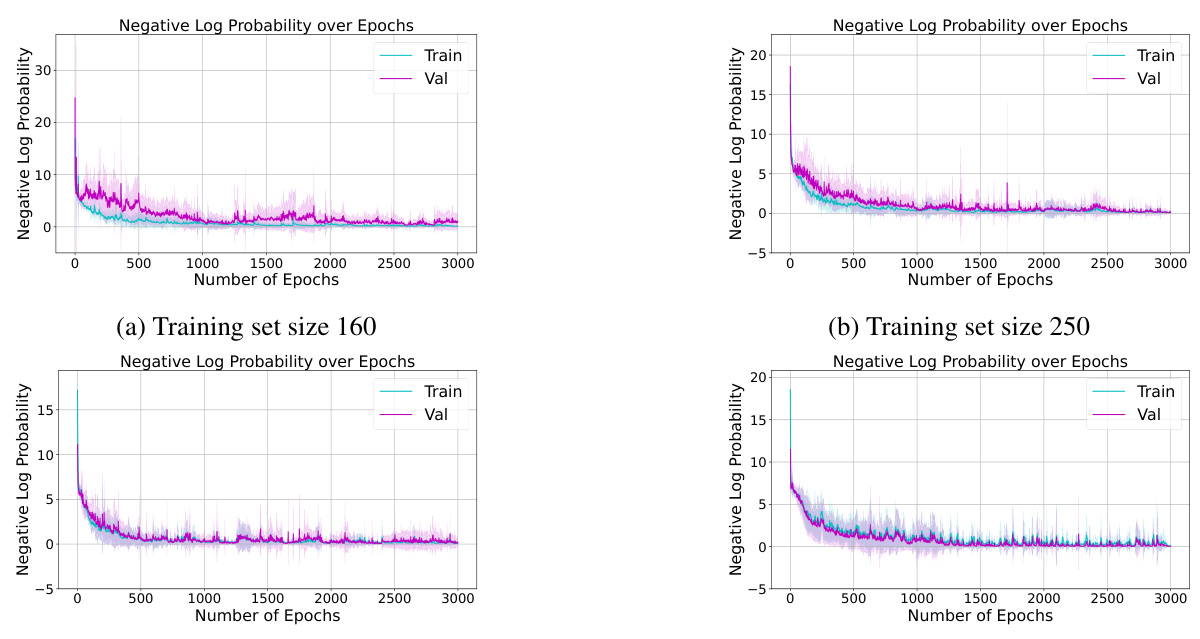

The figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training curve shows the model learns to predict the next token almost perfectly, achieving a negative log probability close to zero. However, the validation curve demonstrates that the model fails to generalize to unseen reverse examples; its performance is no better than random guessing, indicating the presence of a reversal curse.

This figure visualizes the weights (logits) of a model trained for the chain-of-thought (COT) experiment. It uses heatmaps to represent the weights from one token to another. The top row shows the weights for training data, illustrating strong weights along the diagonal (Aᵢ to Bᵢ, Bᵢ to Cᵢ). The bottom row displays the weights for validation data; here, the weights from Aᵢ to Cᵢ are significantly weaker, highlighting the model’s struggle to directly infer Aᵢ → Cᵢ without intermediate steps, thus demonstrating the importance of COT.

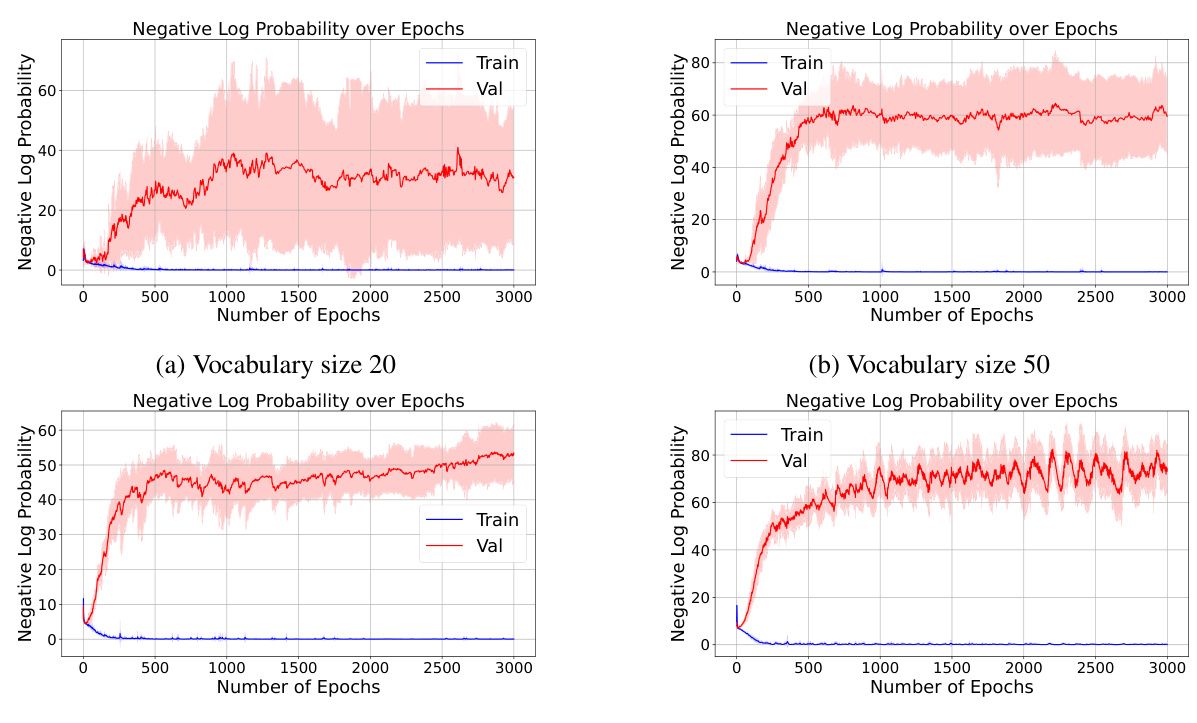

This figure displays the results of experiments on the reversal curse phenomenon, varying the vocabulary size while keeping other parameters consistent with Table 3. The training and validation set sizes are adjusted proportionally to the vocabulary size. The plots show negative log probability over epochs for both training and validation sets, illustrating the model’s performance at different vocabulary sizes.

The figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to a low value, indicating successful learning of forward and backward relationships. However, the validation loss remains high, suggesting a failure to generalize to unseen reverse relationships. The results are averaged over ten random seeds.

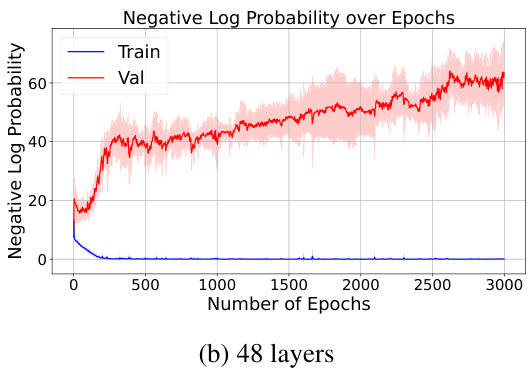

The figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to near zero, indicating that the model learns the training examples well. However, the validation loss remains high, showing that the model fails to generalize to unseen examples, indicating the reversal curse phenomenon.

The figure displays the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment using a default configuration. The model successfully learns to predict the next token for training sentences, but performs no better than random on unseen validation sentences. This demonstrates the reversal curse phenomenon where the model struggles to generalize from A → B to B ← A.

The figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training curve demonstrates that the model learns to predict the next token accurately during training. However, the validation curve shows that the model fails to generalize this ability to unseen data, performing no better than random chance. This illustrates the reversal curse phenomenon where a model trained on a forward relationship fails to predict the reverse relationship.

The figure shows the results of the reversal curse experiment when each entity consists of multiple tokens. The training curves show the model’s ability to learn the training sentences effectively. However, the validation curves indicate that the model struggles to predict the correct tokens in the unseen direction, even when entities contain multiple tokens, which is similar to the result obtained when each entity is represented by one token. This is consistent with the findings presented in the paper, which highlights the reversal curse phenomenon even when entities consist of multiple tokens.

The figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to near zero, indicating successful learning of the forward relationship. However, the validation loss remains high, showing the model’s failure to generalize to the reverse relationship.

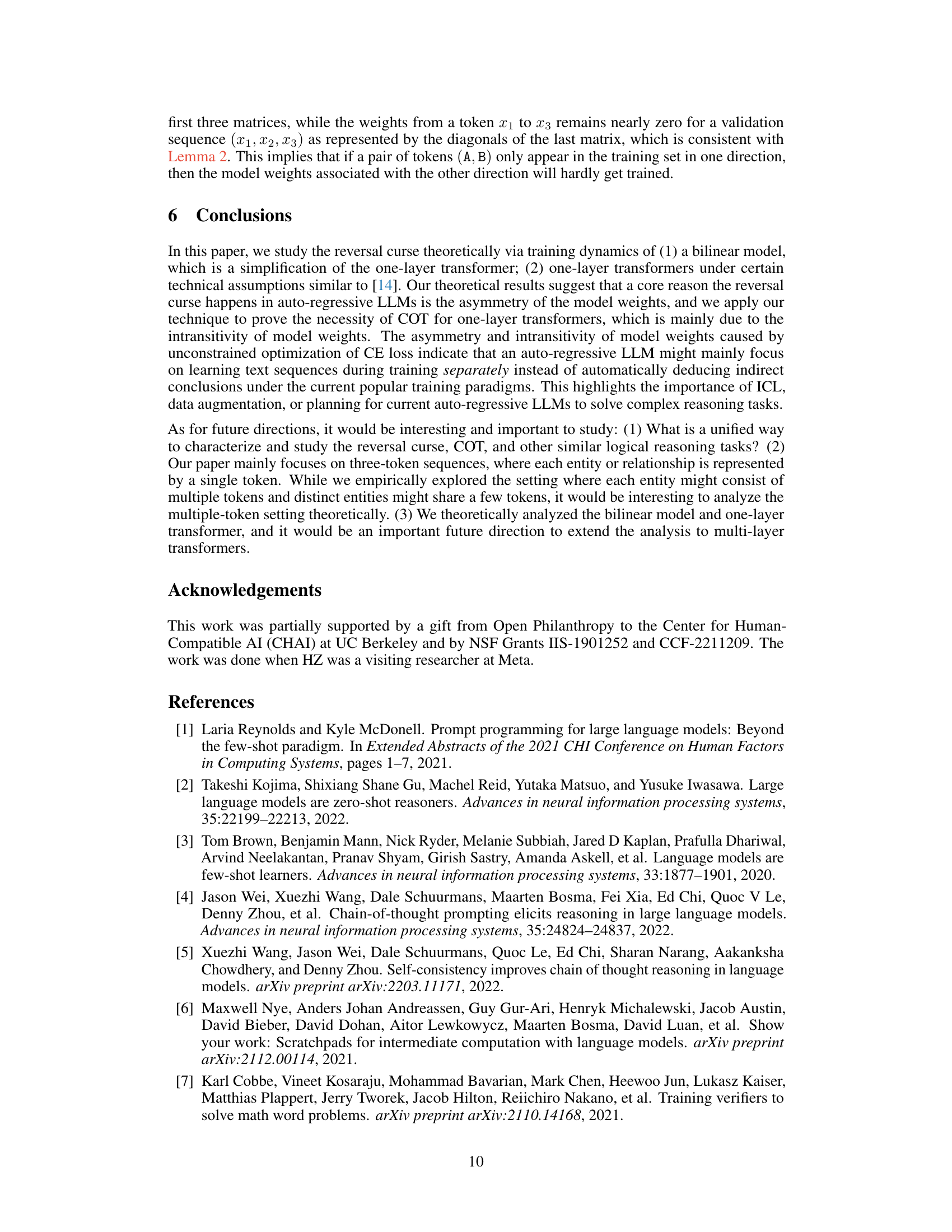

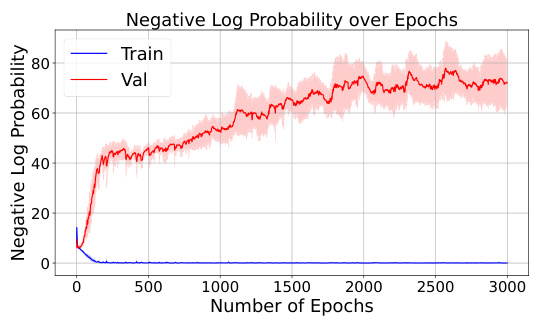

This figure shows the results of the reversal curse experiment under different numbers of layers and embedding dimensions. The x-axis represents the number of epochs, and the y-axis represents the negative log probability. Three different settings are shown: one layer with embedding dimension 20, one layer with embedding dimension 768, and 24 layers with embedding dimension 20. The training and validation curves are plotted for each setting. The results demonstrate that the reversal curse persists across various model configurations, suggesting the phenomenon is robust and not simply an artifact of specific hyperparameter choices.

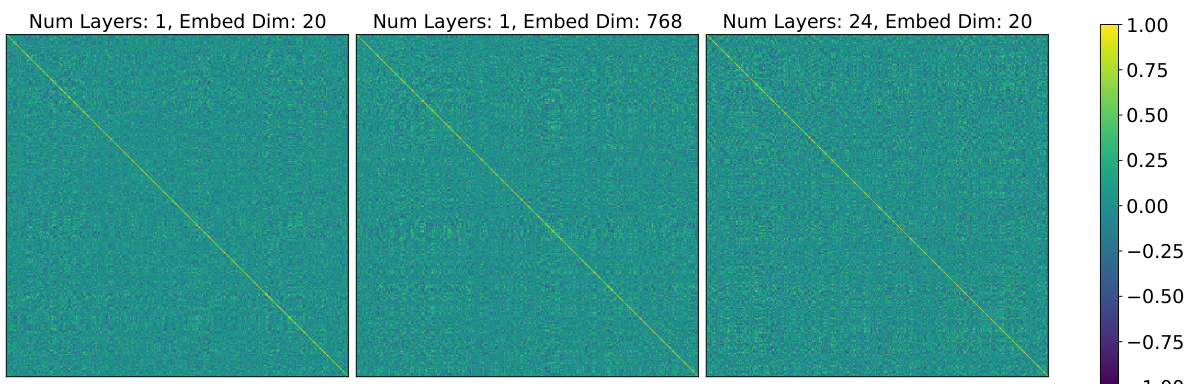

This figure shows heatmaps visualizing the cosine similarity between token embeddings for various experimental settings. The settings vary the number of layers and embedding dimensions of a transformer model. The heatmaps demonstrate that even with different model configurations, most of the non-diagonal entries show values close to zero. This finding supports the conclusion that embeddings of distinct tokens remain nearly orthogonal, which is a key assumption for the theoretical analysis presented in the paper.

The figure shows the training and validation loss for a model trained on a reversal curse task. The training loss converges to 0, indicating the model learns the forward and backward relationships perfectly in the training set. However, the validation loss remains high, showing the model fails to generalize to unseen instances.

This figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to a low value, indicating that the model learns the training data well. However, the validation loss remains high, indicating that the model fails to generalize to unseen data. This demonstrates the reversal curse phenomenon.

This figure shows the training and validation loss for the reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to 0, indicating that the model learns the training data perfectly. However, the validation loss remains high, suggesting that the model fails to generalize to unseen data and suffers from the reversal curse.

The figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to 0, indicating successful learning of the forward direction. However, the validation loss remains high, indicating a failure to generalize to the reverse direction, demonstrating the reversal curse phenomenon.

This figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to near zero, indicating successful learning of the forward direction. However, the validation loss remains high, showing that the model fails to generalize to reverse direction inference.

The figure shows the training and validation loss curves for a reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to 0, indicating that the model learns the training data well. However, the validation loss remains high, indicating that the model fails to generalize to unseen data. This demonstrates the reversal curse phenomenon.

This figure shows the training and validation loss curves for the reversal curse experiment. The training loss converges to a low value, indicating successful learning of the forward relationships. However, the validation loss remains high, demonstrating that the model struggles to generalize to the reverse relationships, illustrating the reversal curse phenomenon.

The figure shows the training and validation loss curves for the reversal curse experiment. The training loss decreases to near zero, indicating successful learning of the forward direction. However, the validation loss remains high, demonstrating a failure to generalize to the reverse direction. This confirms the model’s struggle with the reversal curse phenomenon.

More on tables

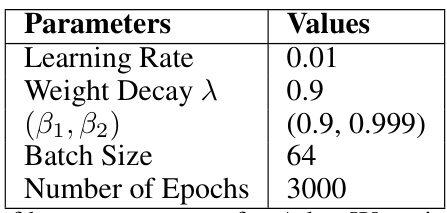

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the GPT-2 model in the experiments described in the paper. The hyperparameters include the learning rate, weight decay, beta parameters for AdamW, batch size, and number of epochs.

This table lists the different hyperparameter configurations used in the experiments for the reversal curse and chain-of-thought. It shows the range of values tested for the number of layers, number of heads, vocabulary size, entity length, positional encoding type (None, Absolute, Relative), and whether token and positional embeddings were learnable or frozen. The default settings used in the main experiments are highlighted in bold.

Full paper#