↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reverse engineering binary code into human-readable source code (HOBRE) is challenging due to the lack of symbolic information in binary code. Existing methods rely on uni-modal models, leading to suboptimal performance. This limitation motivates the need for innovative approaches that effectively bridge the binary-source semantic gap.

This paper introduces ProRec, a novel probe-and-recover framework that addresses this challenge by incorporating both binary-source encoder-decoder models and black-box LLMs. ProRec synthesizes relevant code fragments as context, enhancing the LLMs’ ability to accurately summarize binary functions and recover function names. Experimental results demonstrate significant performance gains over existing methods, highlighting the effectiveness of ProRec in automating and improving binary code analysis.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in binary analysis and reverse engineering. It presents a novel framework, ProRec, that significantly improves the accuracy of automated binary code analysis by leveraging the power of multi-modal models. This work is highly relevant to current trends in transfer learning and large language model applications, opening exciting new avenues for research in software security, program comprehension, and automated software development.

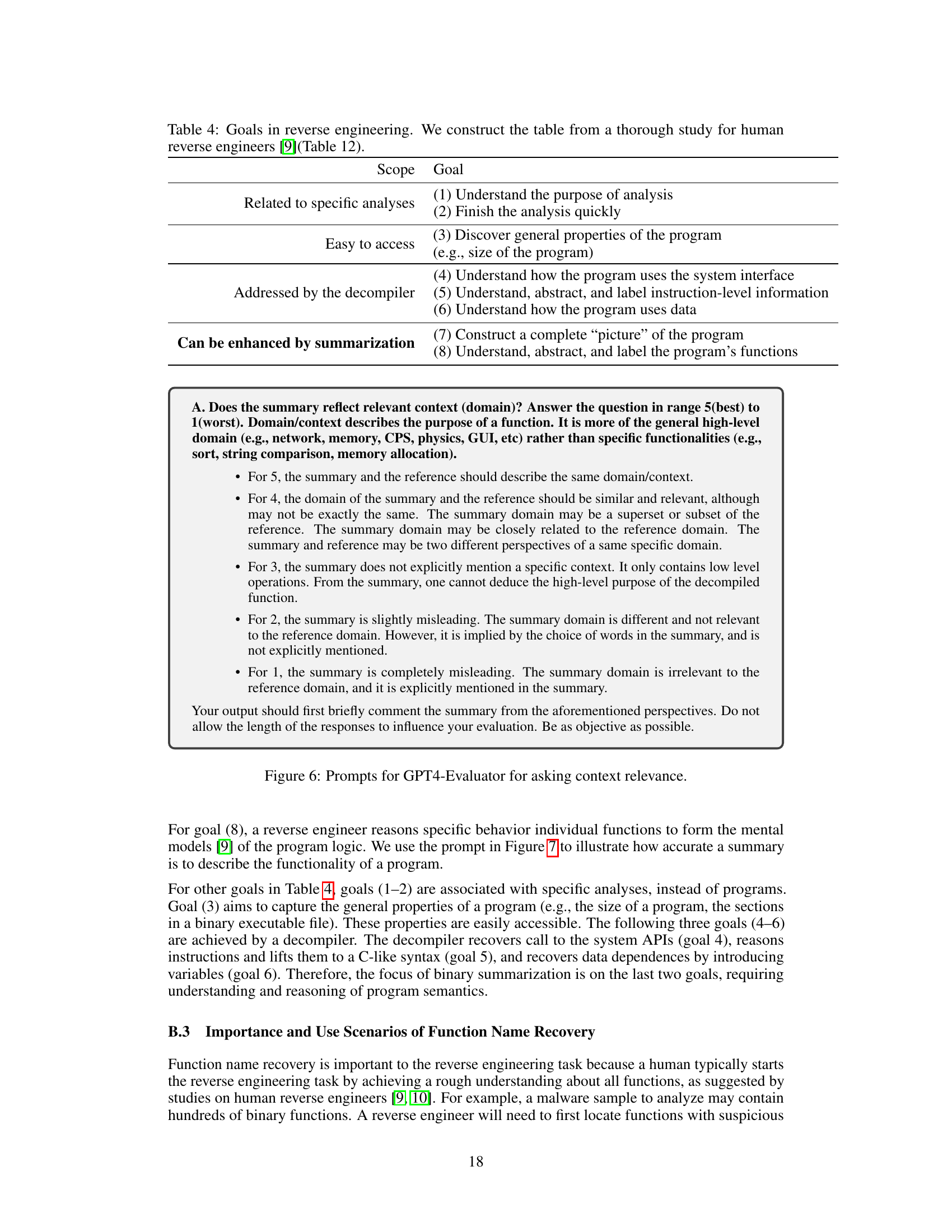

Visual Insights#

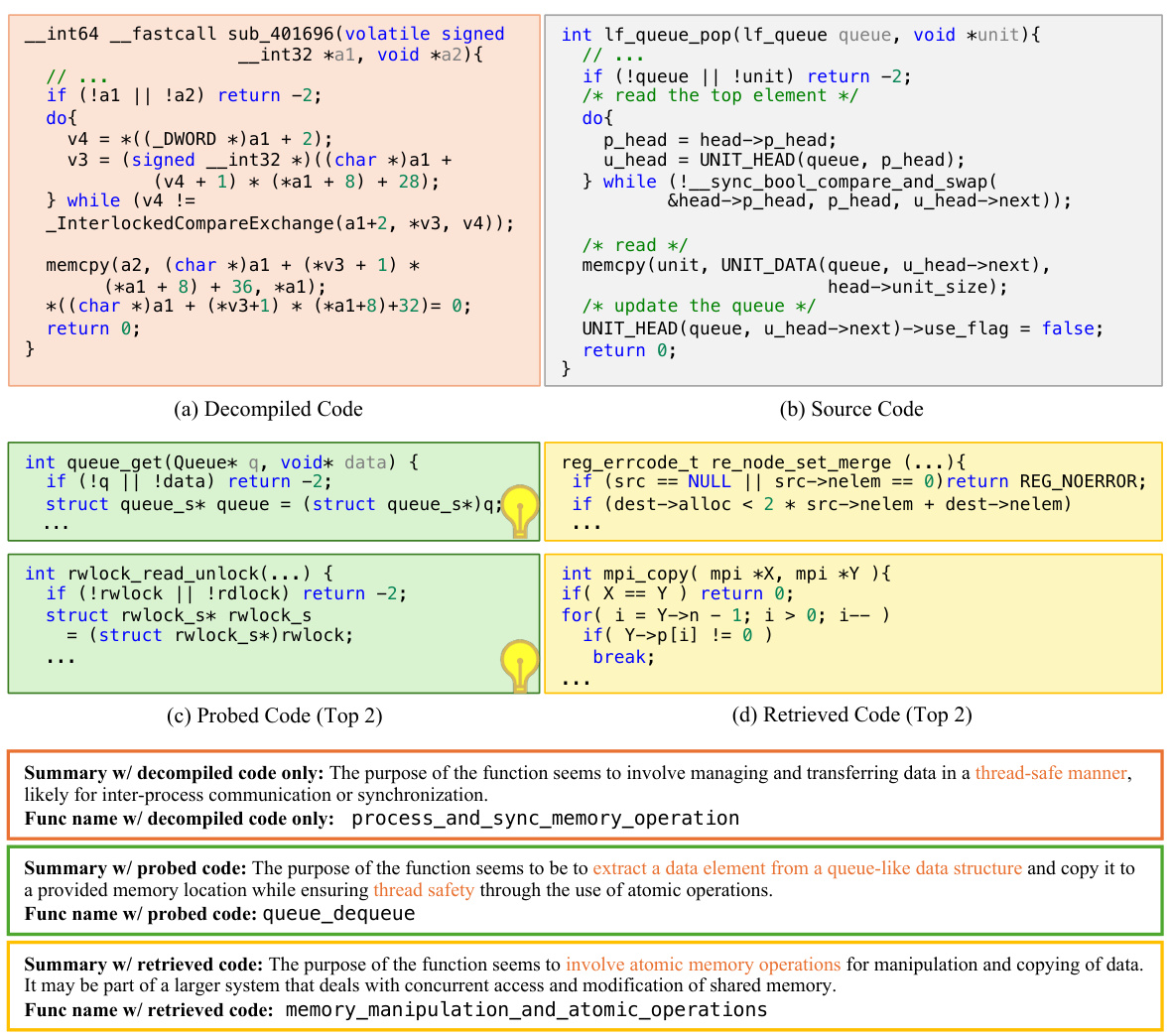

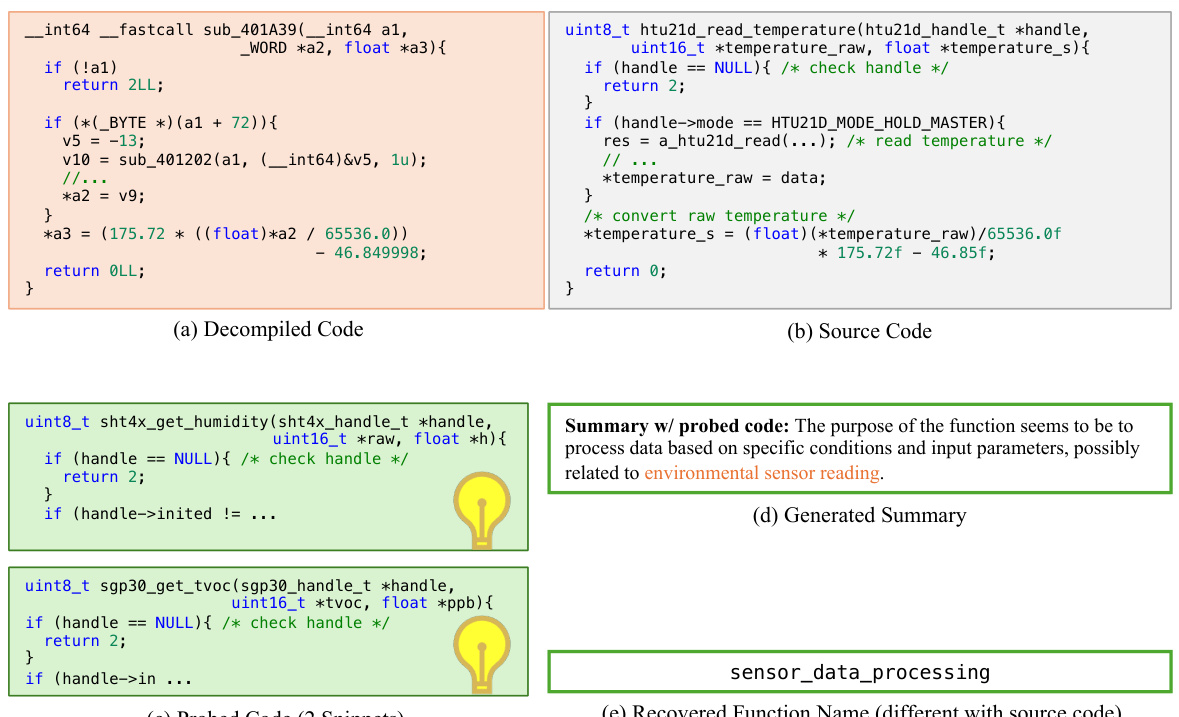

This figure illustrates the ProRec framework, which is a novel probe-and-recover framework for human-oriented binary reverse engineering (HOBRE). It shows how the framework uses a binary-source encoder-decoder model and black-box LLMs to bridge the semantic gap between binary code and source code. The framework synthesizes source code fragments (probed contexts) that are similar to the original source code, but not identical. These contexts help the LLMs recover high-level information and functionality from the binary, resulting in more accurate and human-readable summarizations, rather than simply low-level operation descriptions. The example shown focuses on lifting a cumsum function.

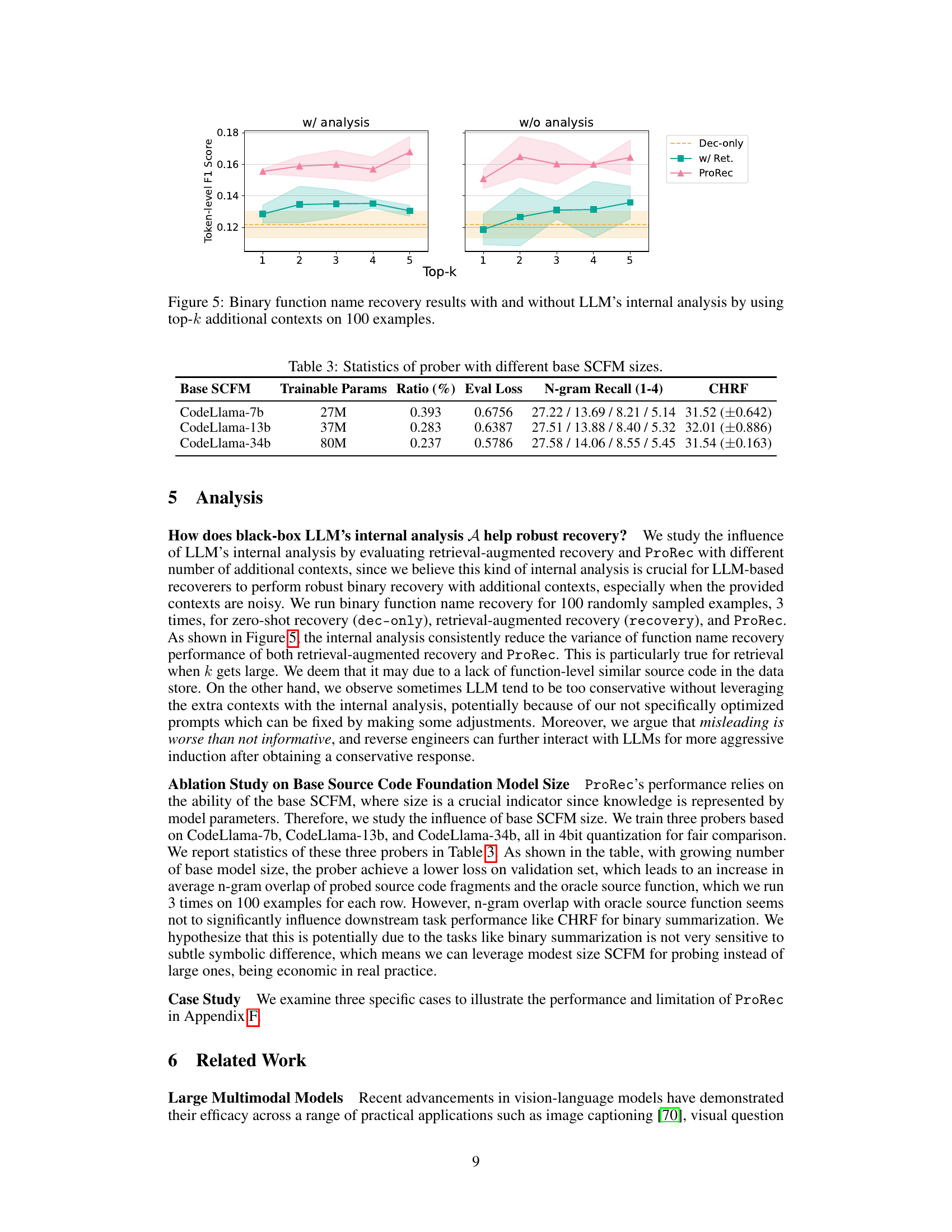

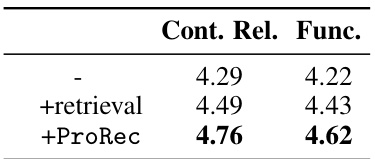

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted on two core tasks: binary summarization and binary function name recovery. It compares the performance of three different approaches: using only the decompiled code, using retrieval-augmented code, and using the ProRec framework. The results are reported using various metrics, including CHRF, GPT4-based metrics for functionality and context relevance, and token and character-level precision, recall, and F1 scores.

In-depth insights#

Transfer Learning in HOBRE#

Transfer learning presents a powerful paradigm shift for Human-Oriented Binary Reverse Engineering (HOBRE). Leveraging pre-trained models from related domains, such as source code foundation models (SCFMs) and large language models (LLMs), offers a significant advantage over training HOBRE models from scratch. This approach mitigates the scarcity of labeled binary-source code data, a significant bottleneck in HOBRE. By transferring knowledge from abundantly available source code data, SCFMs can provide valuable context and semantic understanding, improving the accuracy and efficiency of binary analysis tasks like function summarization and name recovery. The integration of LLMs further enhances the capabilities of transfer learning by enabling complex reasoning and contextual understanding. The effectiveness hinges on a robust alignment strategy between the uni-modal source code and binary models, ensuring that transferred knowledge remains relevant and informative within the binary analysis context. However, challenges remain. The semantic gap between high-level source code and low-level binary code necessitates careful consideration of knowledge representation and transfer mechanisms. Furthermore, ensuring the generalizability and robustness of transferred knowledge across various binary code styles and architectures is crucial for practical applicability. Future research directions include exploring more sophisticated alignment techniques, investigating alternative transfer learning strategies, and addressing the inherent limitations of LLMs in handling the nuanced semantics of binary code.

ProRec Framework#

The ProRec framework, as presented in the research paper, proposes a novel approach to Human-Oriented Binary Reverse Engineering (HOBRE) by bridging the semantic gap between binary and source code. Its core innovation lies in a probe-and-recover strategy that leverages the strengths of both binary analysis models and pre-trained Source Code Foundation Models (SCFMs). A key component is a cross-modal knowledge prober, which synthesizes relevant source code fragments (probed contexts) based on the input binary code. These fragments serve as enhanced contexts for a black-box Large Language Model (LLM), thereby enabling the accurate recovery of human-readable information from the binary. The framework’s effectiveness is demonstrated through improvements in zero-shot binary summarization and function name recovery. The compute-efficient alignment of the binary encoder with the SCFM is another notable feature, contributing to the model’s efficiency and performance. The use of a black-box LLM as a ‘recoverer’ provides flexibility and generalizability, allowing for the adaptation of various LLM architectures. The overall design of ProRec showcases a sophisticated approach to HOBRE, offering a promising direction for automating and enhancing binary code analysis.

Cross-Modal Probing#

Cross-modal probing, in the context of the research paper, is a technique to bridge the semantic gap between binary code and its corresponding source code. It leverages the strengths of both uni-modal models—binary understanding models and source code foundation models (SCFMs)—to effectively synthesize relevant source code fragments given binary input. This is achieved by aligning the binary encoder with the SCFM using a compute-efficient cross-modal alignment approach, avoiding the heavy computational cost associated with retraining large models. The aligned binary-source model acts as a cross-modal knowledge prober, effectively querying the SCFM by conditioning the generation of source code fragments on binary inputs. These fragments, acting as informative context, enhance the accuracy of the black-box LLMs used in downstream tasks like binary summarization and function name recovery. The probing strategy is crucial because, by introducing relevant source code context, the LLMs are less susceptible to noise and sub-optimal performance inherent in dealing with low-level binary code. The efficiency of this approach is highlighted by the utilization of only limited trainable parameters during the alignment process, and the use of a pre-trained SCFM. Thus cross-modal probing is a key component in the proposed framework, enabling the effective transfer of knowledge from source code to facilitate the analysis and understanding of binary code.

LLM-based Recovery#

LLM-based recovery in the context of binary analysis represents a significant advancement, leveraging the power of large language models to bridge the semantic gap between low-level binary code and high-level source code representations. The core idea is to use LLMs not just as a direct translator, but as sophisticated reasoners capable of synthesizing meaningful information from various sources. This approach addresses the limitations of traditional decompilers, which often produce functionally equivalent but semantically opaque C-style code. By incorporating context, such as symbol names and code structure (potentially generated by another model trained on source code and binary code mappings), LLMs can produce more human-understandable summaries and function name recovery. This multi-modal approach has the potential to significantly automate and improve binary code analysis, especially for tasks involving code comprehension and documentation. However, challenges remain, such as dealing with noisy or incomplete decompiled code, handling the diversity of programming styles, and ensuring the reliability and robustness of LLM inferences. Furthermore, the ethical implications of using LLMs in this domain necessitate careful consideration. Future work should focus on improving the accuracy and generalizability of LLM-based recovery, addressing the aforementioned challenges, and exploring the responsible use of these powerful models within security-sensitive applications.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for this research could explore several promising avenues. Expanding the model’s capabilities to handle inter-procedural analysis would significantly boost its practical applicability, moving beyond single functions to encompass the complexities of entire programs. Investigating different base SCFMs and binary encoders could further improve performance and generalizability. Exploring different LLMs for the recovery step could reveal further potential for enhanced performance. Additionally, improving the efficiency and scalability of the current architecture is crucial for broader adoption. A particularly interesting area for future work involves exploring the interaction and potential synergistic effects between the probe and recover components. Further research could focus on the development of more sophisticated cross-modal alignment techniques, enabling the model to better capture the nuances of the semantic relationships between binary and source code. Finally, a comprehensive evaluation of ProRec on a broader range of benchmarks would solidify its position in the field and highlight its strengths and limitations more accurately.

More visual insights#

More on figures

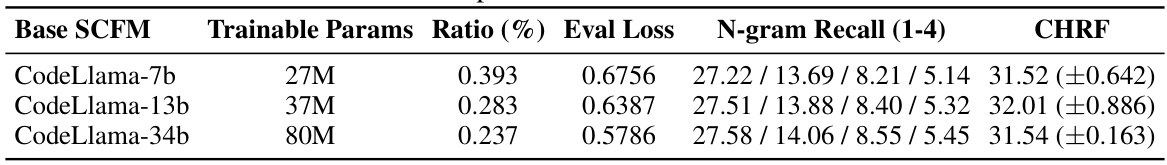

This figure shows the architecture of the cross-modal knowledge prober used in the ProRec framework. The prober takes as input a disassembled binary function and its dependency graph. It uses a structure-aware binary function encoder (CODEART) to extract features from the binary code. These features are then projected into the embedding space of a pre-trained source code foundation model (SCFM, like CodeLlama). A key aspect highlighted is the compute-efficient alignment strategy; only a small part of the model (the projection layer and the last block of the binary encoder) is trainable, while the SCFM remains frozen to leverage its pre-trained knowledge efficiently. The resulting embeddings are then used to synthesize relevant source code fragments.

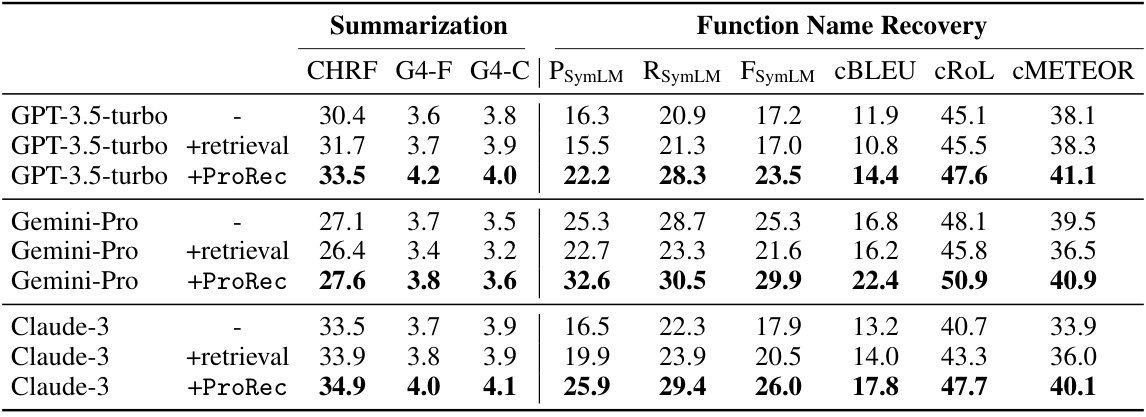

This figure shows a scatter plot comparing the negative log-likelihood (NLL) estimations of source code functions. One estimation is from a base Source Code Foundation Model (SCFM) and the other is from the aligned prober (a model that conditions the SCFM on binary code). The strong positive correlation and the trendline suggest that the aligned prober effectively leverages the pre-trained knowledge in the base SCFM while incorporating information from binary code.

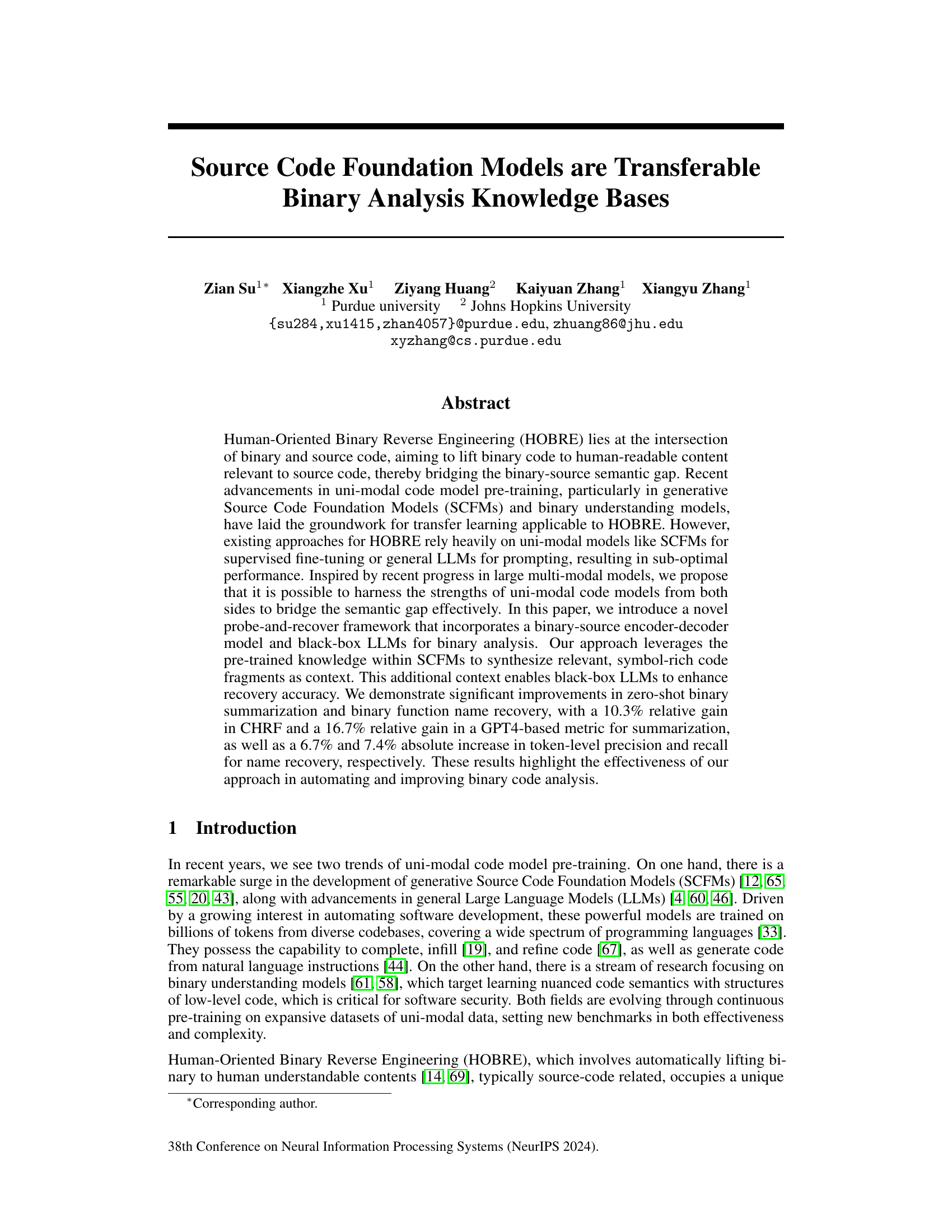

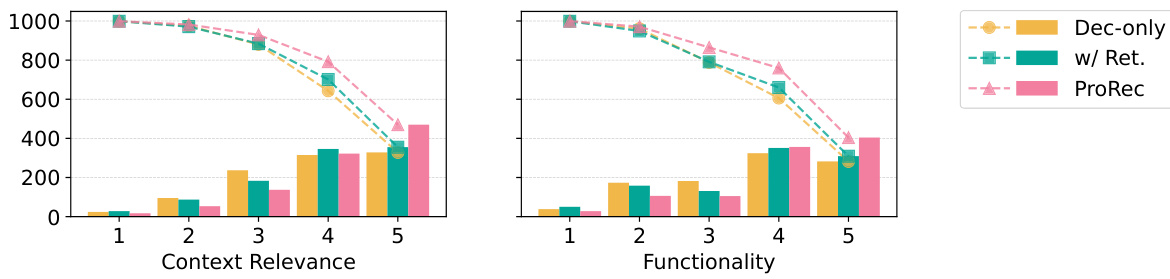

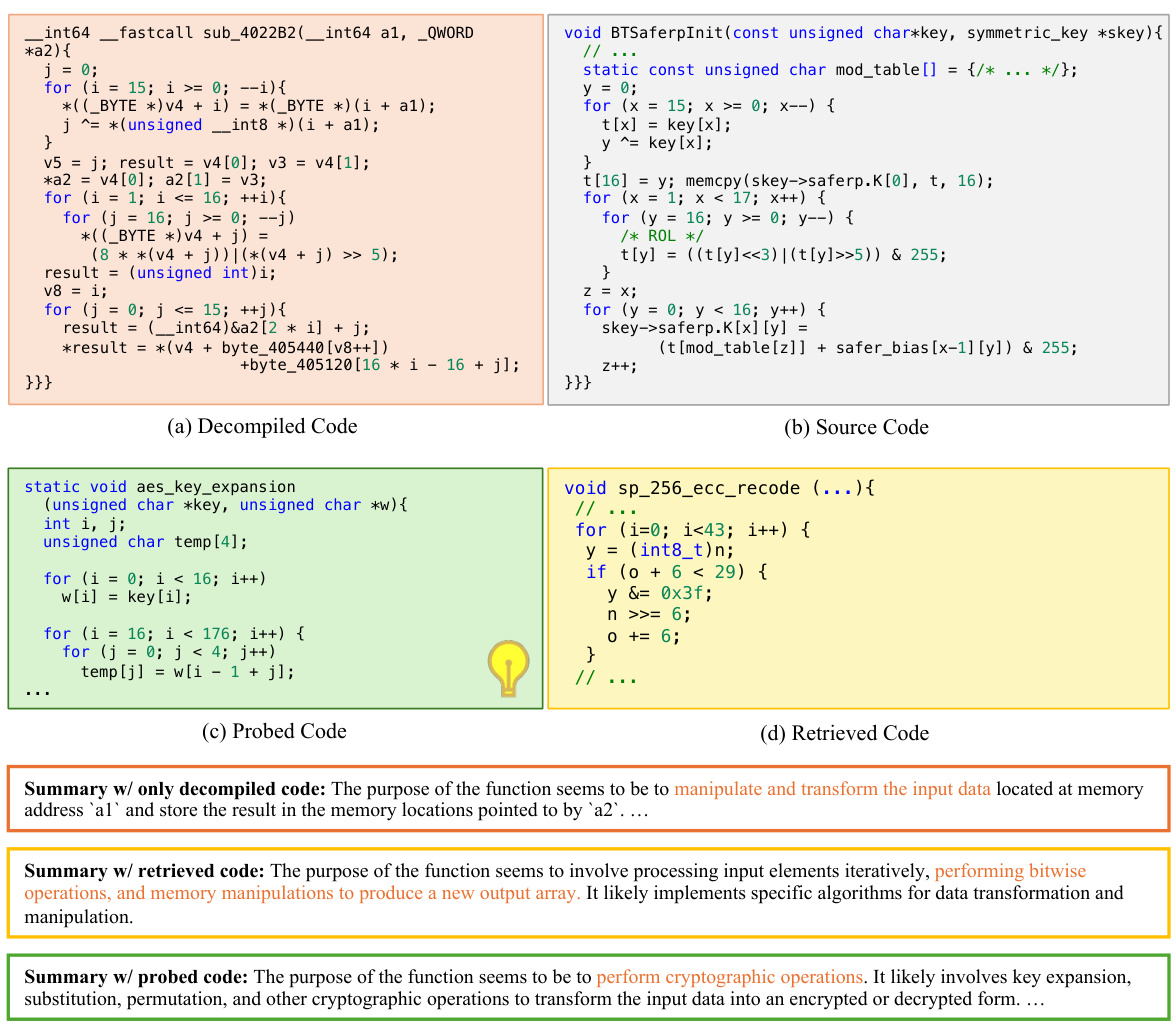

This figure presents the results from a GPT4-based evaluator assessing the quality of summaries generated using three different methods: directly from decompiled code only, using retrieval-augmented approach, and using the proposed ProRec framework. The x-axis represents the scores (1-5, with 5 being the best) given by the evaluator for two criteria: context relevance and functionality. The y-axis shows the number of summaries that received each score (bars) and the cumulative number of summaries that received at least that score (dashed lines). The bars and lines are color-coded for each method to compare their performance across different scores and criteria. The results show that ProRec generally outperforms the other two methods in both context relevance and functionality.

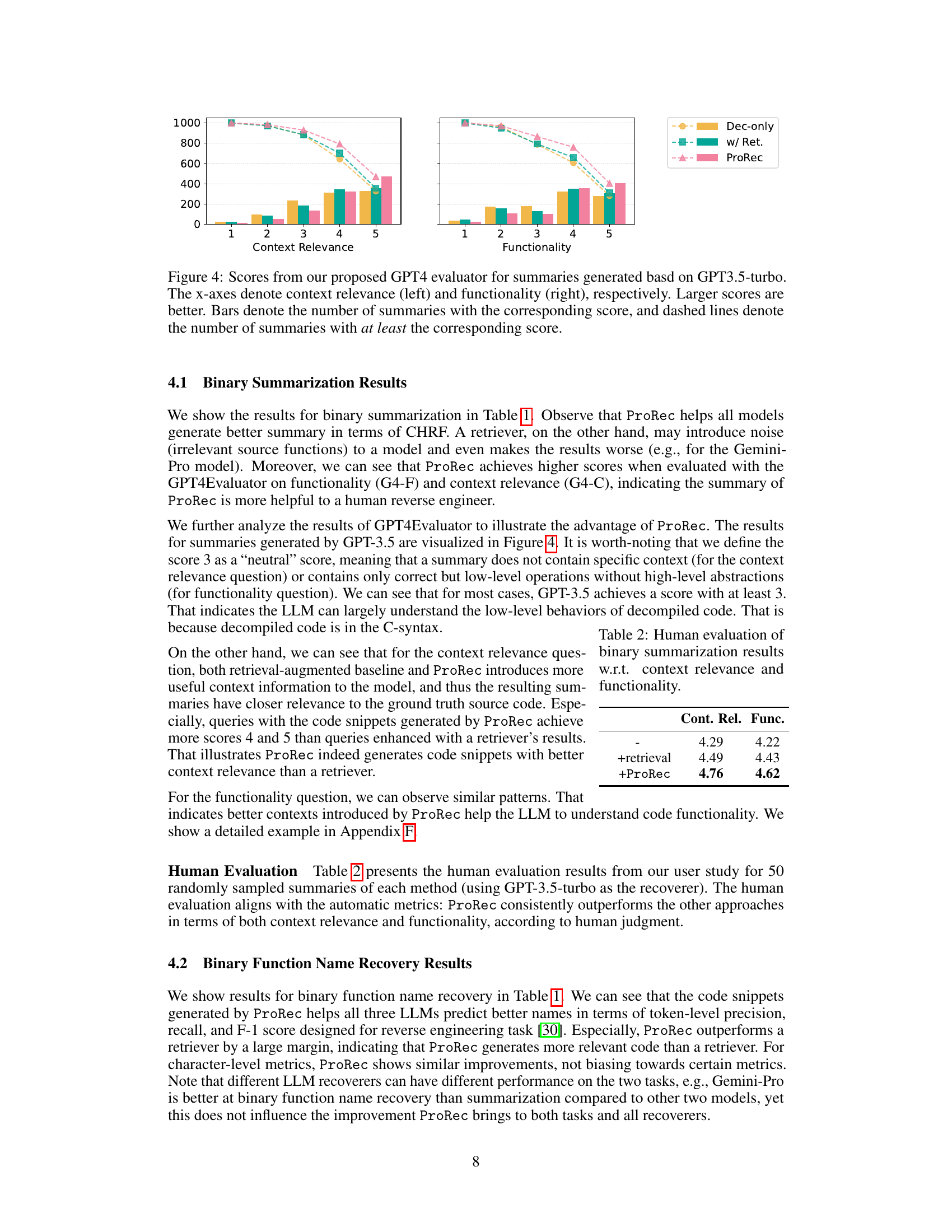

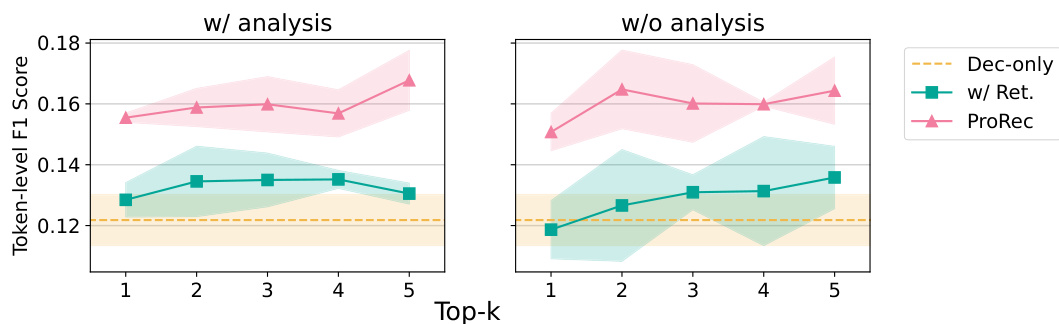

This figure shows the results of binary function name recovery experiments with and without using the internal analysis feature of LLMs. The experiments used different numbers of additional contexts (Top-k) and compared three approaches: direct prompting (Dec-only), retrieval-augmented approach (+Ret), and the proposed ProRec framework. The left panel shows results when LLM’s internal analysis is used, while the right panel displays results without it. The shaded areas represent confidence intervals, illustrating the variability in performance. The results show that the use of LLM’s internal analysis generally leads to more consistent performance, especially when a larger number of additional contexts is provided. The Token-level F1 score is shown on the y-axis.

The figure illustrates the ProRec framework, a novel approach to human-oriented binary reverse engineering (HOBRE). It shows how a cross-modal knowledge prober uses a binary-source encoder-decoder model and a black-box LLM to synthesize relevant source code fragments as context for the LLM. This context helps the LLM to generate human-readable summaries of binary functions that accurately capture high-level functionality, rather than just low-level operations. An example of lifting a cumulative sum function from binary to a human-readable summary is provided.

This figure illustrates the ProRec framework, which is a novel probe-and-recover framework for human-oriented binary reverse engineering (HOBRE). It shows how the framework uses a binary-source encoder-decoder model and black-box LLMs to lift a binary function’s cumsum function to human-readable summarization. The key is using a cross-modal knowledge prober to synthesize relevant source code fragments as context, enhancing the accuracy of the black-box LLM’s recovery of high-level functionality.

This figure illustrates the ProRec framework, a novel approach to human-oriented binary reverse engineering (HOBRE). It demonstrates how the framework uses a cross-modal knowledge prober and a black-box LLM to convert binary code into a human-readable summary. The prober synthesizes source code fragments, which, despite not being identical to the original, provide valuable context for the LLM to generate an accurate and high-level summary of the binary function’s functionality.

This figure illustrates the ProRec framework, a novel approach to human-oriented binary reverse engineering. It shows how a binary cumsum function is processed. First, a cross-modal knowledge prober, using a binary-source encoder-decoder model and a pre-trained source code foundation model (SCFM), synthesizes relevant source code fragments as context. These fragments, even if not identical to the original source code, provide valuable information, such as symbol names and loop structures. Then, a black-box large language model (LLM) acts as a recoverer, using the binary function and the synthesized context to generate a human-readable summarization of the function’s high-level functionality, bridging the semantic gap between binary and source code.

This figure illustrates the ProRec framework, which bridges the semantic gap between binary and source code for human-oriented binary reverse engineering. It shows how a binary function (a cumsum function in this example) is processed through a cross-modal knowledge prober and a black-box LLM to generate a human-readable summarization. The prober synthesizes relevant source code fragments, which, even if not identical to the original source code, provide valuable symbolic information and structural context. This enhanced context allows the LLM to generate a summary that accurately reflects the high-level functionality of the binary function, surpassing summaries based solely on low-level decompiled code.

More on tables

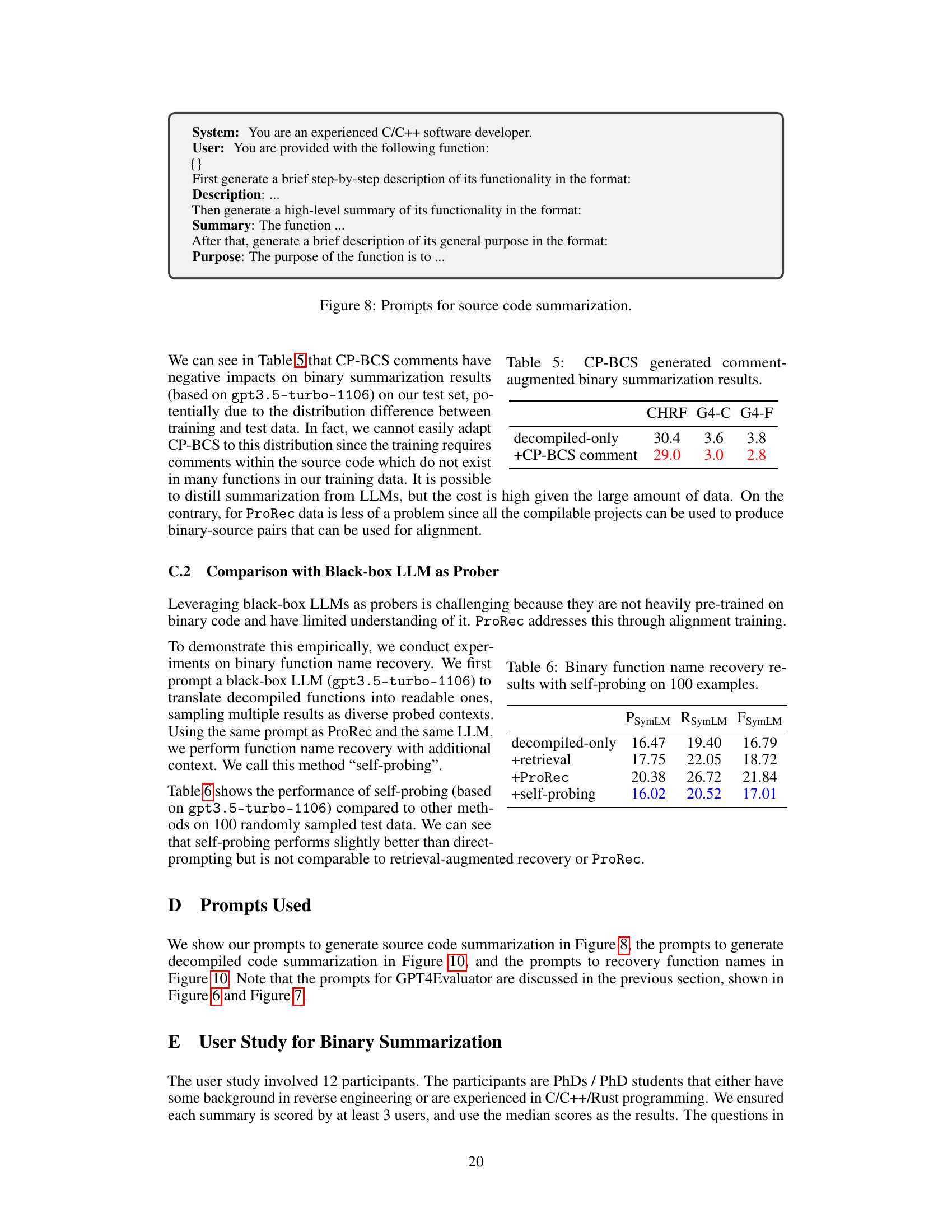

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted on two tasks: binary summarization and binary function name recovery. It compares three different approaches: using only the decompiled code, using retrieval-augmented methods, and using the proposed ProRec framework. The results are evaluated using various metrics: CHRF, GPT-4 based evaluations for context relevance (G4-C) and functionality (G4-F), token-level precision/recall/F1 (PsymLM, RSymLM, FSymLM), and character-level BLEU, ROUGE-L, and METEOR. The table highlights the improvements achieved by ProRec across all metrics.

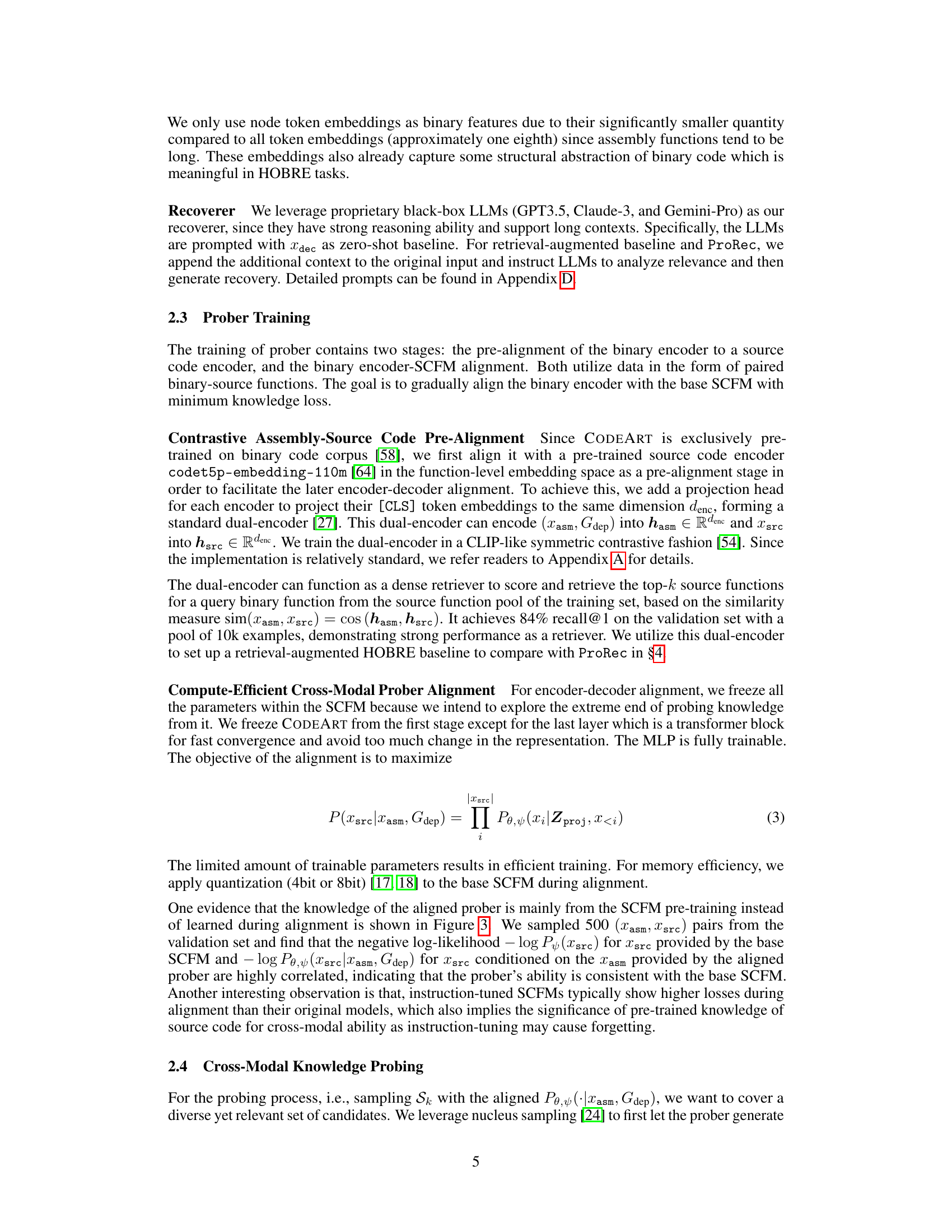

This table presents the statistics of the cross-modal knowledge prober using different sizes of base source code foundation models (SCFMs). It shows the number of trainable parameters in the prober, the ratio of trainable parameters to the total parameters, the evaluation loss, the n-gram recall at different n-gram lengths (1-4), and the CHRF score. These statistics illustrate the impact of the base SCFM size on the prober’s performance.

This table presents the quantitative results of the proposed ProRec framework on two main tasks: binary summarization and binary function name recovery. It compares the performance of three different model setups: using only the decompiled code, retrieval augmented baseline, and ProRec. Evaluation metrics include various automatically computed scores (CHRF, GPT-4 based scores for functionality and context relevance, token-level precision/recall/F1 score, character-level BLEU/ROUGE-L/METEOR) to assess the quality of the generated summaries and recovered function names.

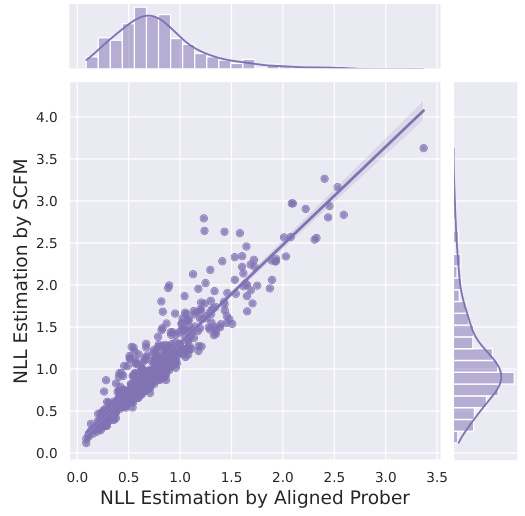

This table presents the quantitative results of the proposed ProRec framework on two core tasks: binary summarization and binary function name recovery. It shows the performance of different LLMs (GPT-3.5-turbo, Gemini-Pro, Claude-3) with three setups: using only the decompiled code, using the code with retrieval-augmented method, and using the code with ProRec. Multiple metrics are used to assess the quality of the generated summaries and the accuracy of recovered function names, including CHRF, GPT4-based metrics for context relevance and functionality, and token-level/character-level precision, recall, and F1 scores.

This table presents the quantitative results of the proposed ProRec framework on two binary reverse engineering tasks: binary summarization and binary function name recovery. It compares the performance of three different approaches (using only decompiled code, retrieval-augmented baseline, and ProRec) across multiple large language models (LLMs). The metrics used to evaluate the performance of the summarization task include CHRF, GPT4-based metrics for functionality (G4-F) and context relevance (G4-C), character-level BLEU, ROUGE-L, and METEOR. For function name recovery, token-level precision, recall, F1-score, and character-level BLEU, ROUGE-L, and METEOR are reported.

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted in the paper on two tasks: binary summarization and binary function name recovery. For each task, results are shown for three different settings: using only the decompiled code, using the decompiled code along with source code snippets retrieved from a datastore (retrieval-augmented baseline), and using the decompiled code along with source code snippets generated by ProRec (the proposed method). The metrics used to evaluate the results include CHRF, GPT4-based metrics (G4-F and G4-C) for summarization, and token-level and character-level metrics (PsymLM, RSymLM, FSymLM, cBLEU, cRoL, CMETEOR) for function name recovery.

This table presents the results of binary function name recovery experiments using self-probing with 100 examples. It compares the performance of three different approaches: using only the decompiled code, using the decompiled code along with source code snippets retrieved from a datastore (retrieval), and using the decompiled code along with source code snippets generated by self-probing. The performance is evaluated using token-level precision (PSymLM), recall (RSymLM), and F1-score (FSymLM) metrics.

This table presents the main results of the experiments conducted on two tasks: binary summarization and binary function name recovery. For binary summarization, it shows the performance of different models (GPT-3.5-turbo, Gemini-Pro, and Claude-3) with three different setups: (1) using only the decompiled code, (2) using decompiled code plus retrieved source code, and (3) using decompiled code plus source code generated by ProRec. The metrics used are CHRF, GPT4-based scores for functionality and context relevance, and character-level BLEU, ROUGE-L, and METEOR scores. For binary function name recovery, the table presents token-level precision, recall, and F1-score, along with the same three setups as above. This provides a quantitative comparison of ProRec’s effectiveness against baseline methods for both tasks.

Full paper#