↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current multi-view neural scene reconstruction methods often struggle to produce physically realistic 3D models, hindering applications requiring accurate physical properties. This is mainly due to a lack of physics modeling in these methods and their inability to recover intricate geometrical structures, such as slender shapes. These limitations restrict the use of such reconstructions in domains like robotics and embodied AI that demand precise physical accuracy.

PHYRECON addresses this issue by integrating differentiable rendering and differentiable physics simulation to learn implicit surface representations. It introduces a novel differentiable particle-based physical simulator and an efficient algorithm (SP-MC) for converting between implicit and explicit surface representations. The model also incorporates rendering and physical uncertainty to handle inconsistent and inaccurate input data and improve the learning of slender structures. Experiments demonstrate PHYRECON significantly improves reconstruction quality and physical plausibility, paving the way for physics-based applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly significant for researchers in computer vision and graphics because it introduces a novel approach to 3D scene reconstruction that leverages both differentiable rendering and differentiable physics simulation. This is important because existing methods often produce physically implausible results, limiting their utility in various applications. PHYRECON’s ability to improve physical plausibility opens up new avenues for research in physics-based graphics and robotics, allowing for more realistic and robust simulations and applications.

Visual Insights#

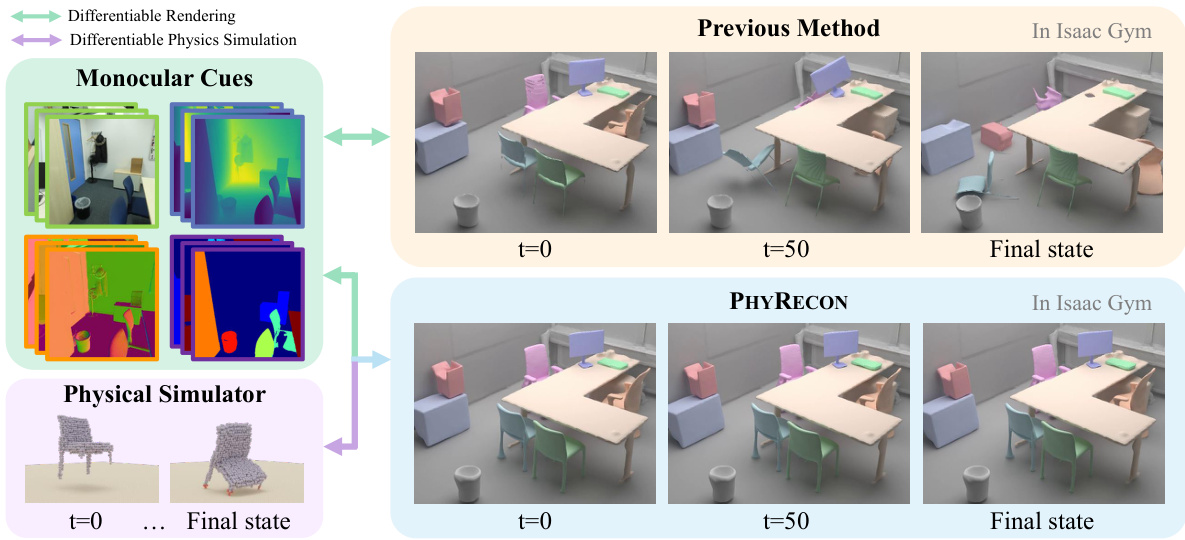

This figure compares the results of PHYRECON with those of previous methods in terms of physical stability and reconstruction quality. The top part shows the pipeline of PHYRECON, highlighting the integration of differentiable rendering and physics simulation. The bottom part shows the results of the different methods in the Isaac Gym simulator. Previous methods fail to maintain physical stability during a simple drop simulation, often collapsing or losing geometric integrity. In contrast, PHYRECON produces reconstructions that remain stable, demonstrating significantly improved physical plausibility.

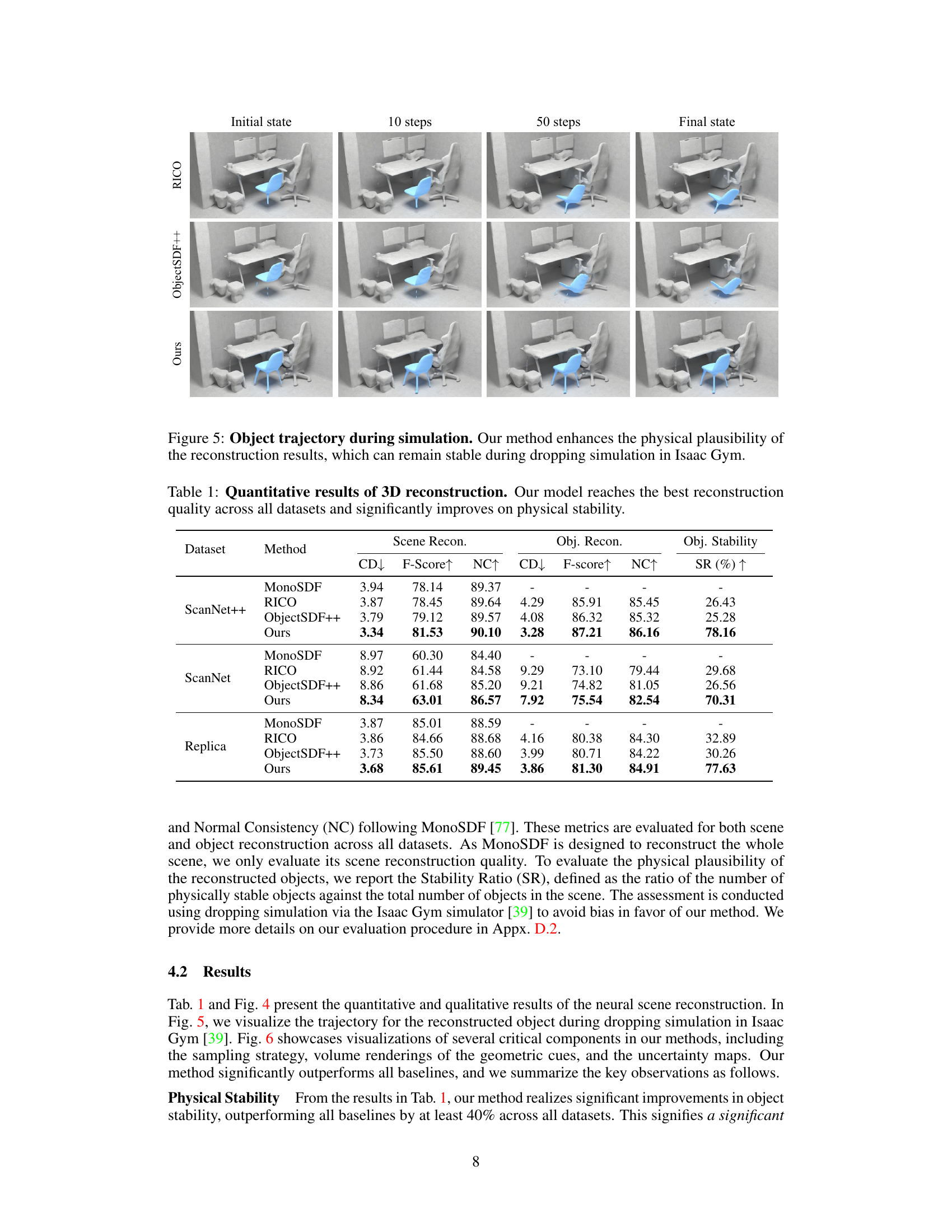

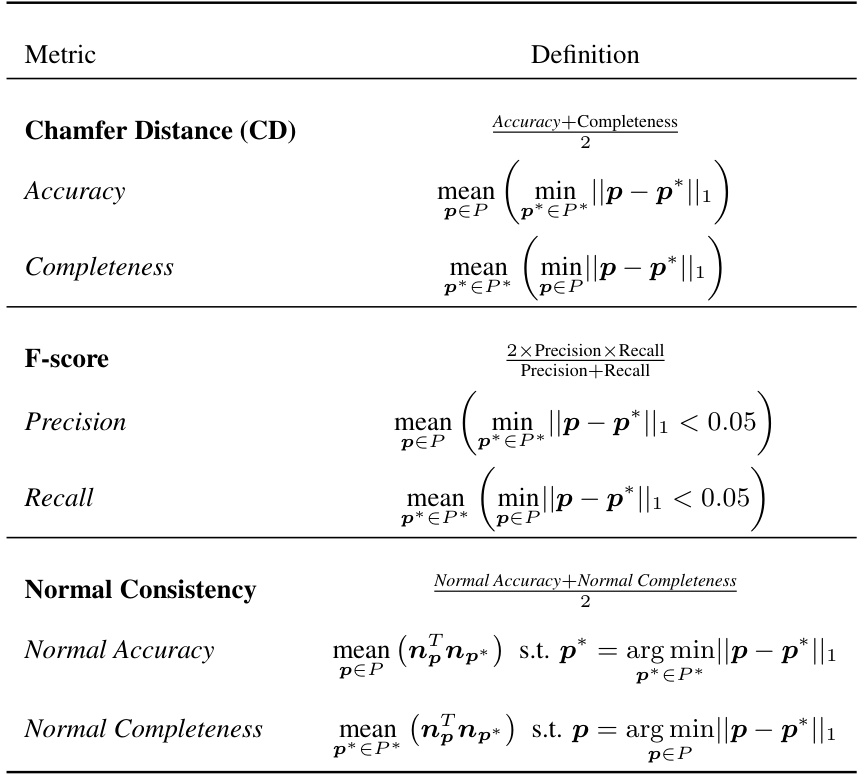

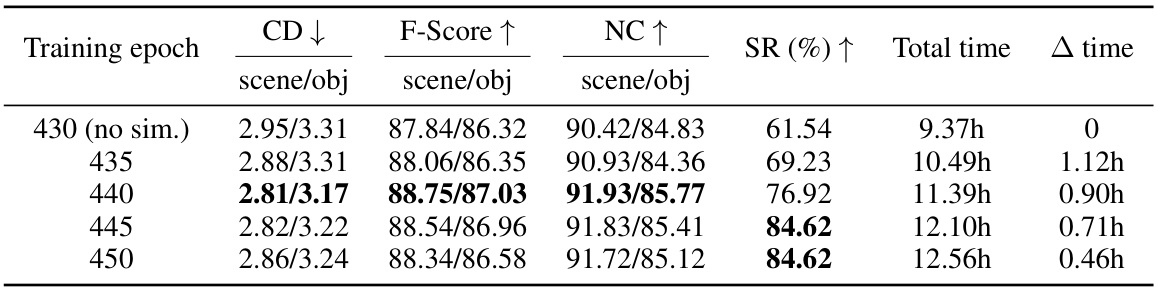

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed PHYRECON model against three state-of-the-art baselines (MonoSDF, RICO, and ObjectSDF++) on three different datasets (ScanNet++, ScanNet, and Replica). The evaluation metrics include Chamfer Distance (CD) and F-score for both scene and object reconstruction, as well as Normal Consistency (NC) to measure the accuracy of normal estimation. Crucially, it also reports Object Stability (SR), indicating the percentage of reconstructed objects that maintain physical stability during a drop test simulation. The results demonstrate that PHYRECON achieves superior performance in terms of reconstruction quality and physical stability compared to the existing baselines across all datasets.

In-depth insights#

Physically-Plausible 3D#

Physically-plausible 3D modeling presents a significant challenge, demanding a departure from traditional methods that prioritize visual fidelity over physical accuracy. Implicit neural representations, while popular for their ability to capture complex shapes from multi-view images, often lack the physics-based constraints necessary for realistic simulations. The core issue lies in the absence of differentiable physics modeling in current methods. To address this, innovative techniques that integrate differentiable rendering with differentiable physics simulation are crucial. This involves creating particle-based physical simulators that can directly interact with the implicit surface representations, enabling the joint optimization of geometry and physics through loss functions that consider both rendering and physical constraints. Furthermore, a robust approach needs to account for modeling uncertainties, which is critical to avoid erroneous priors. This can be achieved through mechanisms such as joint uncertainty modeling, accounting for both rendering and physical uncertainty, and physics-guided pixel sampling to effectively learn and reconstruct slender structures that are crucial for physical plausibility and stability. This combined approach will enhance reconstruction quality and significantly improve the physical stability of generated models in simulations.

Differentiable Physics#

Differentiable physics, a burgeoning field, integrates the principles of physics into differentiable programming frameworks. This allows for the seamless incorporation of physical constraints and simulations within machine learning models, enabling the optimization of systems that involve complex physical interactions. The key advantage is enabling gradient-based optimization of physical systems. This is achieved by making the simulation itself differentiable, meaning that gradients can be backpropagated through it, making it possible to use gradient descent to find optimal solutions that satisfy both physical laws and other objectives. Differentiable physics paves the way for novel applications in robotics, computer graphics, and scientific modeling, where the integration of physics-based simulation with data-driven methods can lead to more realistic and robust results. However, the computational cost of differentiable physics simulations can be high, especially for complex systems. Furthermore, developing accurate and efficient differentiable physics simulators remains a significant challenge. Despite these challenges, differentiable physics is a rapidly evolving field with the potential to transform numerous domains.

Uncertainty Modeling#

The concept of uncertainty modeling is crucial for robust and reliable 3D scene reconstruction, especially when dealing with inherent ambiguities in visual data and the complexities of physical simulations. The authors thoughtfully address these challenges by incorporating joint uncertainty modeling, encompassing both rendering uncertainty and physical uncertainty. Rendering uncertainty mitigates inconsistencies arising from multi-view and multi-modal geometric priors (depth and normal), improving the fidelity of learned representations. Crucially, physical uncertainty reflects the dynamic behavior of the object in the differentiable physical simulator and addresses the challenges of reconstructing slender structures by focusing on regions lacking sufficient physical support. This combined approach allows for physics-guided pixel sampling, enhancing the learning of detailed and physically plausible geometries. The incorporation of these uncertainty models leads to significant improvements in reconstruction quality and physical stability, highlighting the value of explicitly accounting for uncertainty when bridging vision and physics.

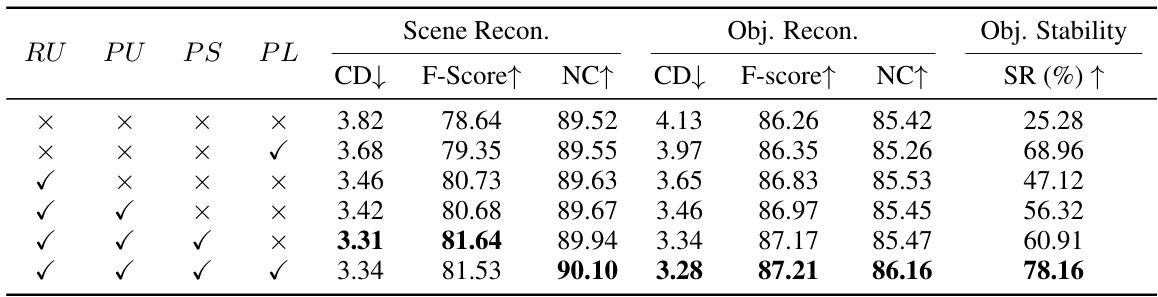

Ablation Study Results#

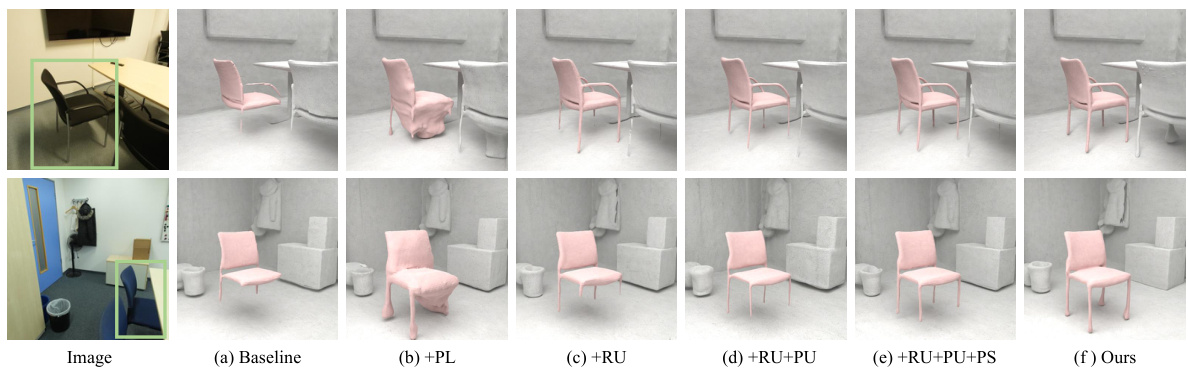

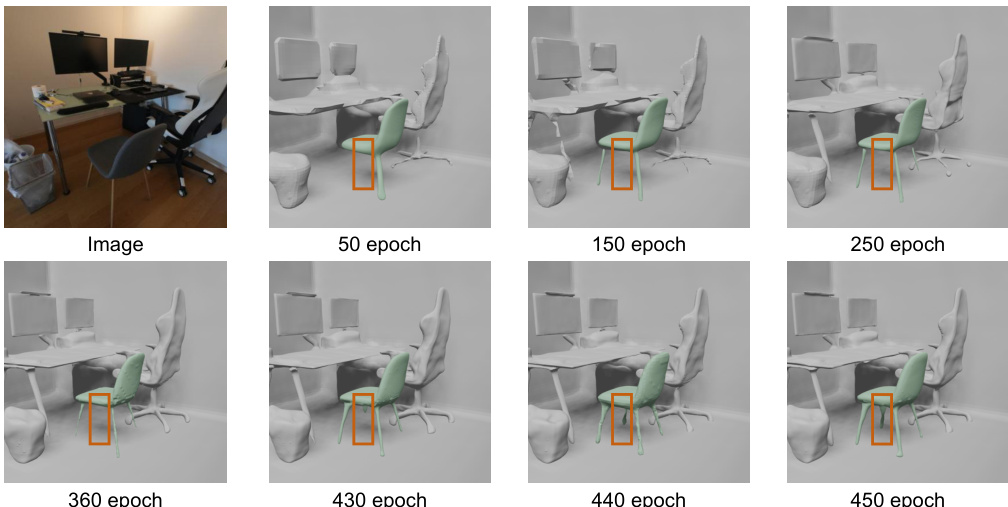

An ablation study for a 3D reconstruction model systematically removes components to assess their individual contributions. The results reveal the critical role of physical loss in enhancing stability, although it alone isn’t sufficient for high-quality reconstruction. Combining physical loss with rendering and physical uncertainty significantly improves the reconstruction quality, particularly for slender structures. This suggests a synergistic effect between physics-based and appearance-based optimization. Physics-guided pixel sampling further enhances the reconstruction of intricate geometries. The ablation study provides strong evidence that the model’s success stems from the careful integration of different modules, highlighting the importance of a holistic approach for physically plausible neural scene reconstruction.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this physically plausible neural scene reconstruction work could involve several key areas. Improving the efficiency and scalability of the differentiable physics simulator is crucial for handling larger and more complex scenes. Exploring more advanced physics models, such as soft-body dynamics or fluid simulation, will enhance the realism and applicability. Furthermore, extending the approach to handle diverse scene types, beyond indoor scenes, and incorporating more diverse sensor modalities (e.g., depth sensors, LiDAR) are promising avenues. A deeper investigation into joint uncertainty modeling and how to effectively leverage it for robust reconstructions remains critical. Finally, the potential of this method for various downstream tasks in robotics, augmented reality, and computer graphics should be thoroughly investigated. This includes the development of new applications that directly benefit from the enhanced physical accuracy and stability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

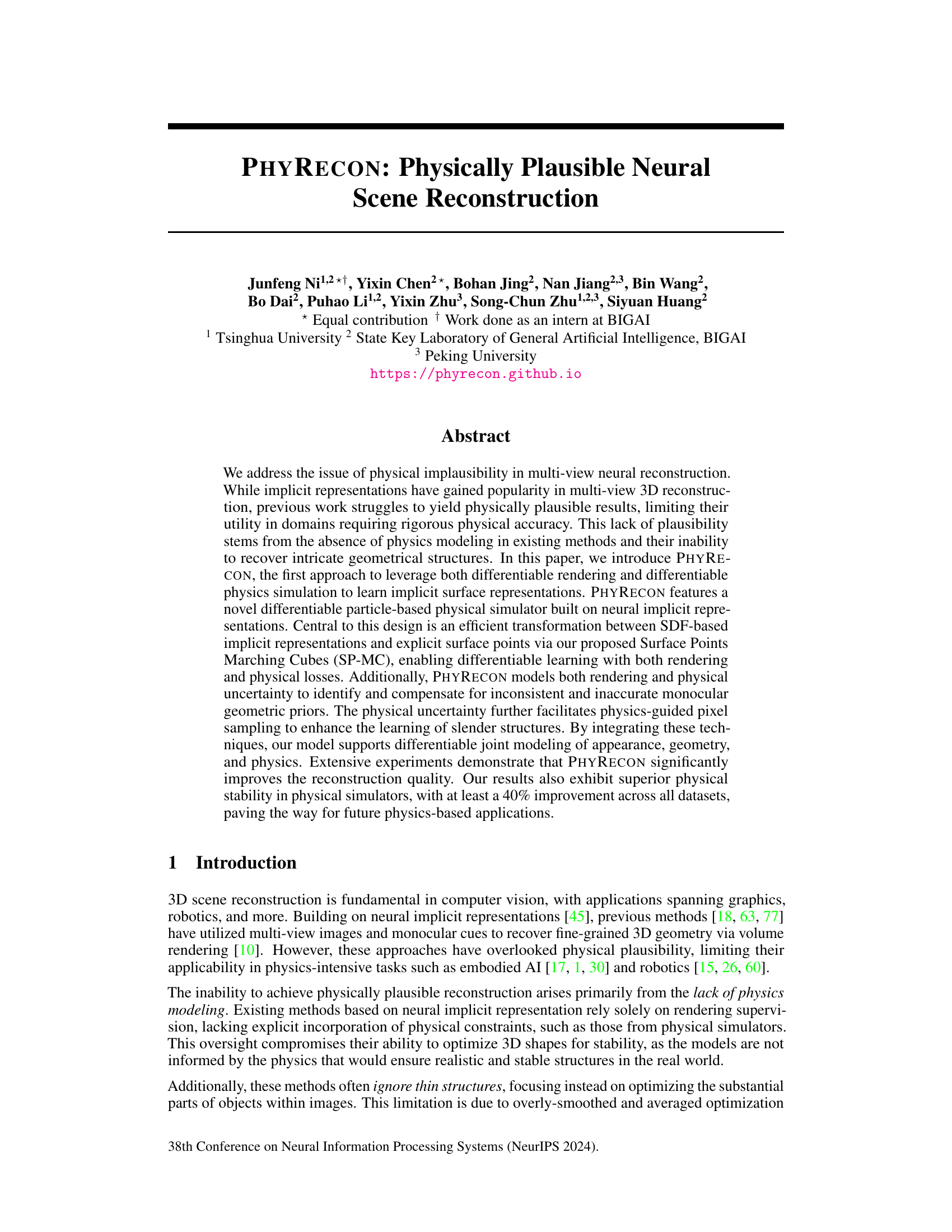

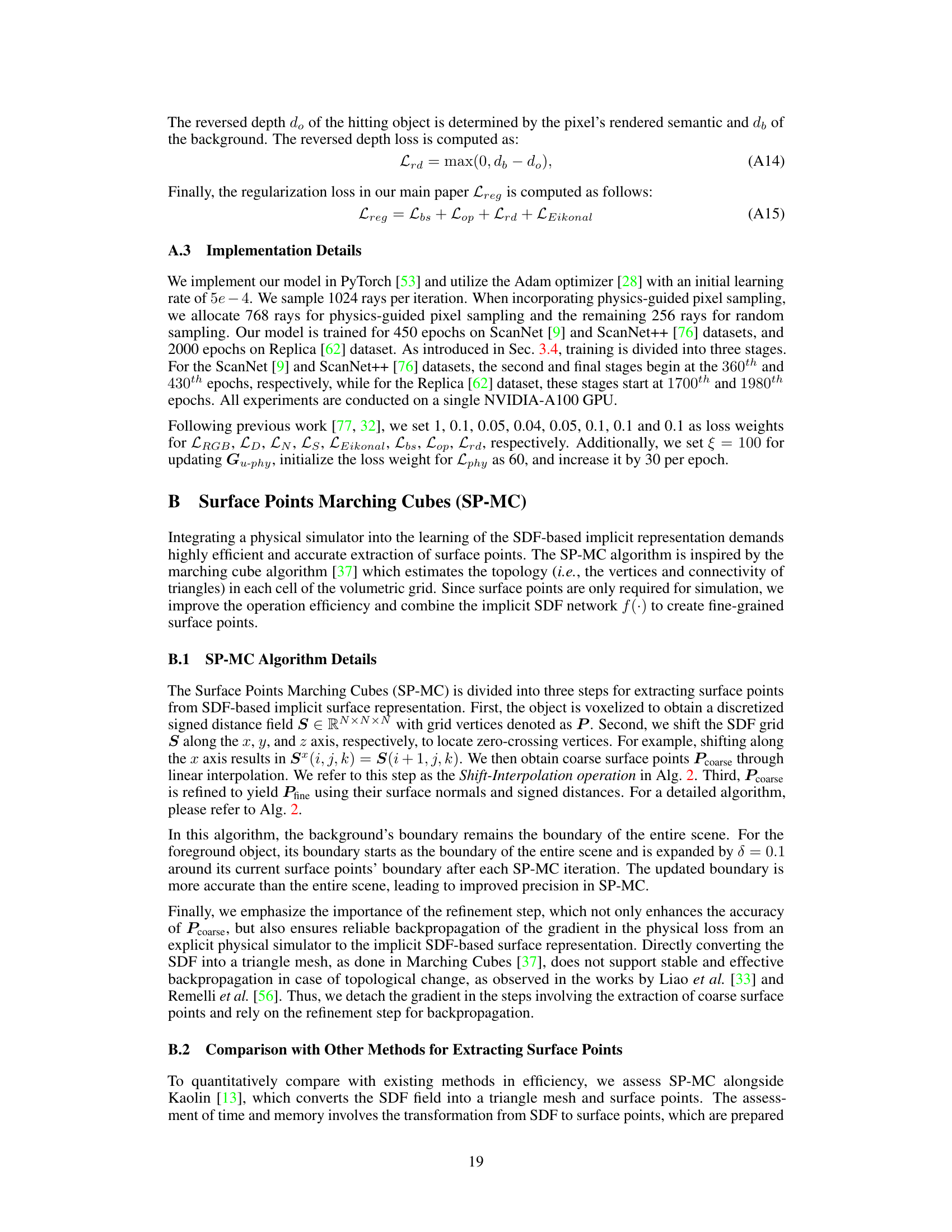

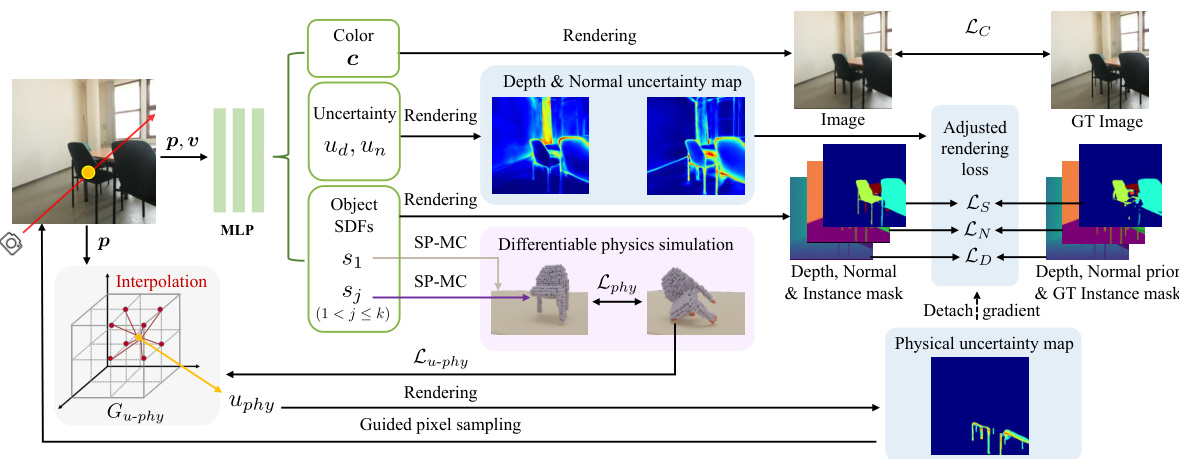

The figure shows a schematic overview of the PHYRECON framework. It starts with monocular cues (images) and uses differentiable rendering and a differentiable particle-based physical simulator to reconstruct the scene. Uncertainty modeling (both rendering and physical) is incorporated to improve reconstruction accuracy. The SP-MC (Surface Points Marching Cubes) module efficiently transforms between implicit surface representations and explicit points used in physics simulation. This integrated approach allows the model to learn from both rendering and physical losses, leading to improved reconstruction quality and physical plausibility.

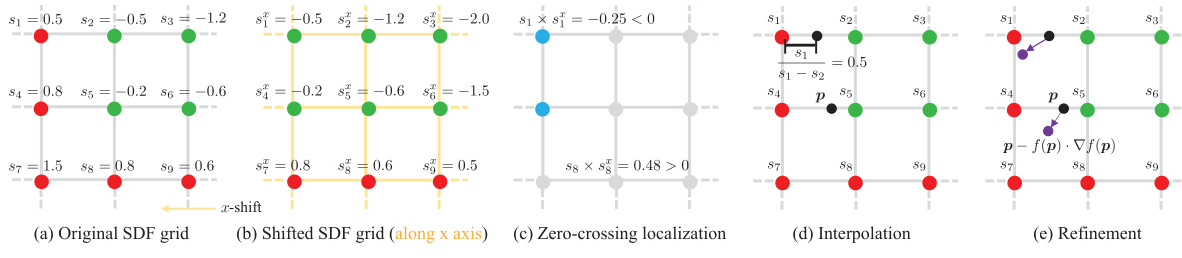

This figure illustrates the steps of the Surface Points Marching Cubes (SP-MC) algorithm. It starts with an original SDF grid (a). The grid is then shifted along the x-axis (b) to identify zero-crossings, indicating where the surface is (c). Linear interpolation is used to get initial, coarse surface points (d), which are then refined by querying the SDF network to produce accurate surface points (e).

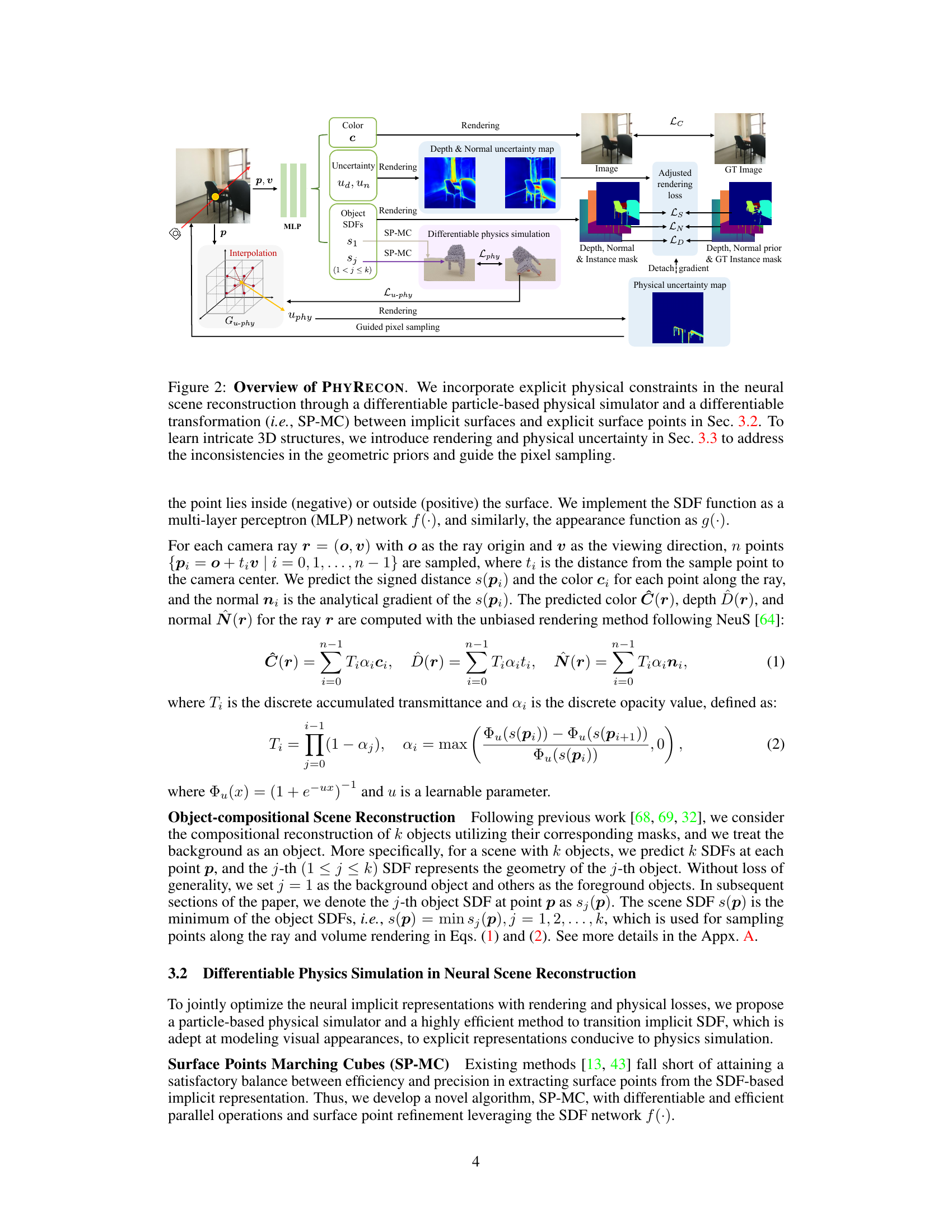

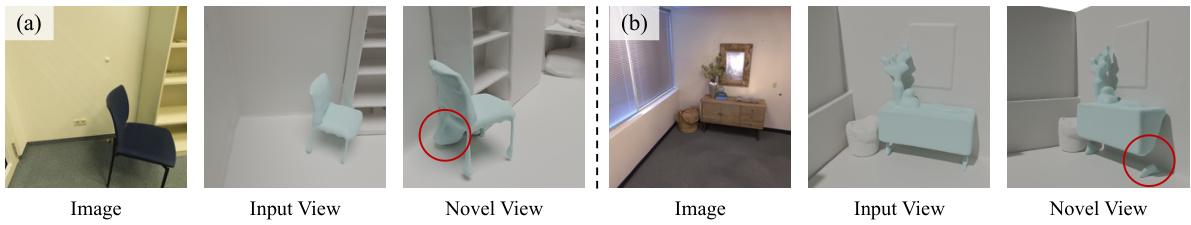

This figure showcases qualitative results comparing the proposed PHYRECON model against three baseline methods (MonoSDF, RICO, and ObjectSDF++) on three datasets (ScanNet++, ScanNet, and Replica). The results demonstrate that PHYRECON produces higher-quality reconstructions with more detailed and accurate representations of slender structures (like chair legs) and more physically plausible object support relationships. Zoom-in boxes highlight these improvements.

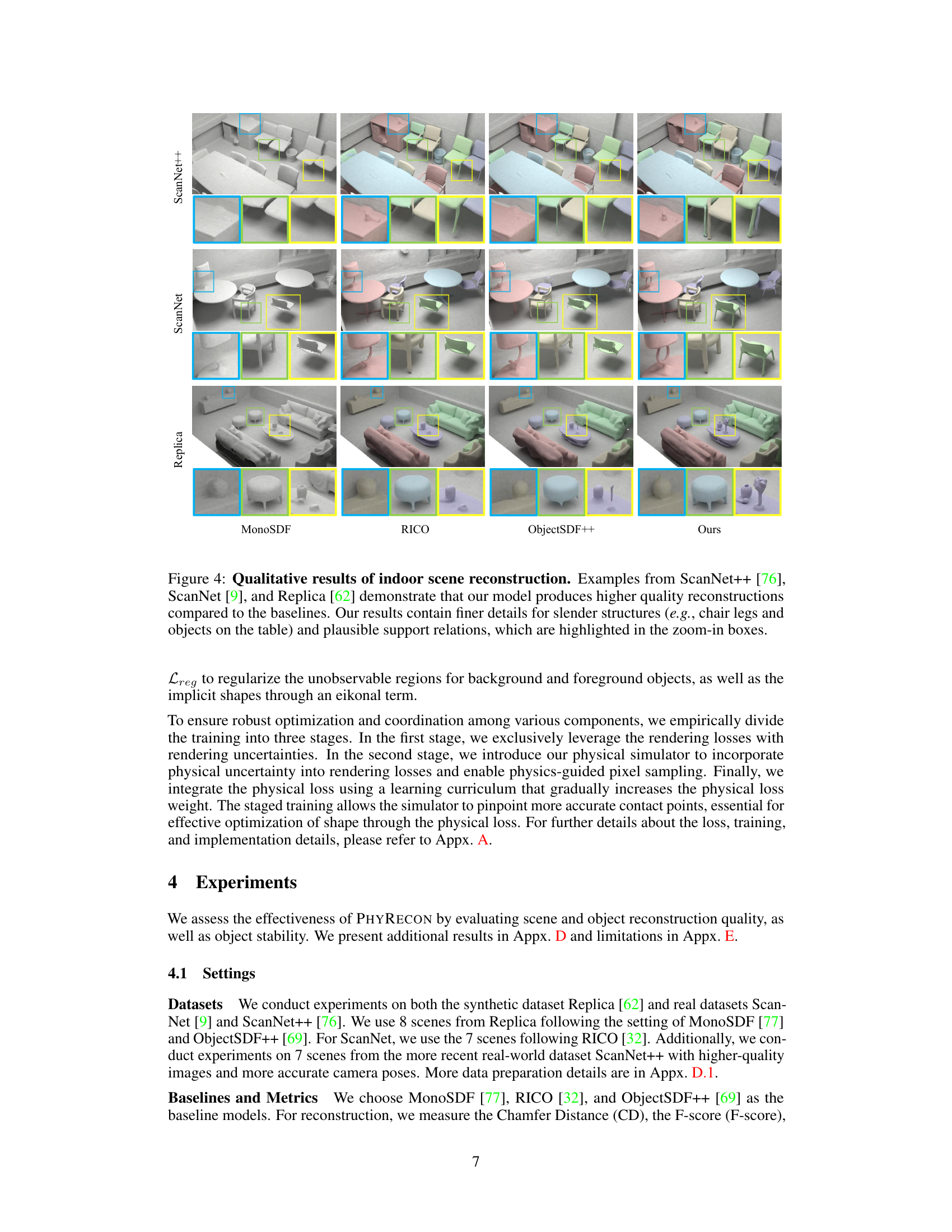

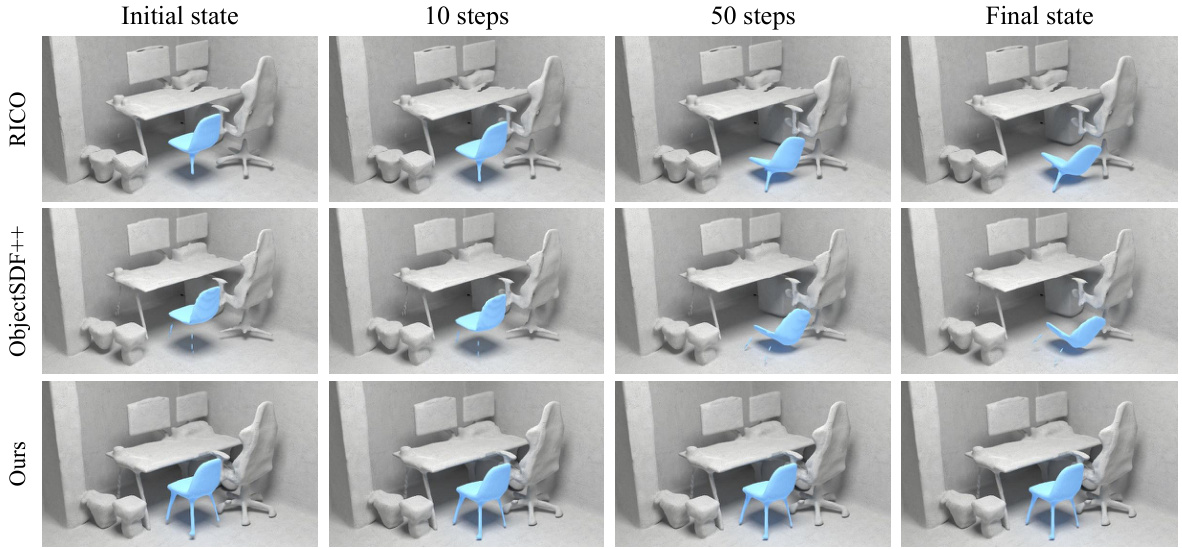

This figure shows a comparison of the stability of 3D object reconstruction results obtained by three different methods (RICO, ObjectSDF++, and the proposed PHYRECON) when subjected to a dropping simulation in Isaac Gym. Each row represents a different method, and each column shows the state of the scene at different time steps: initial state, after 10 steps, after 50 steps, and the final state. The figure demonstrates that PHYRECON significantly improves the physical plausibility of the reconstruction, as the reconstructed objects remain stable throughout the simulation, unlike the results produced by the other two methods, where the objects topple over.

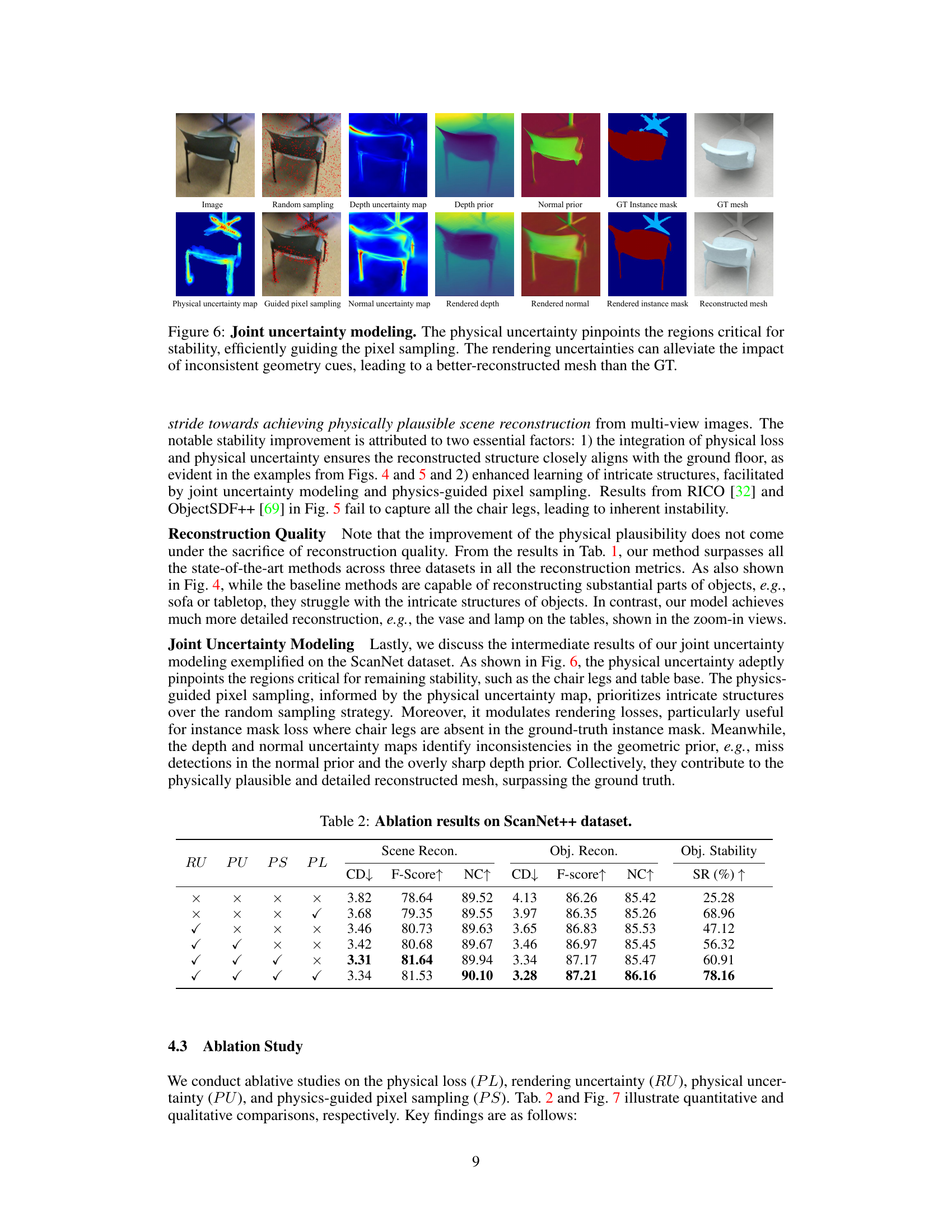

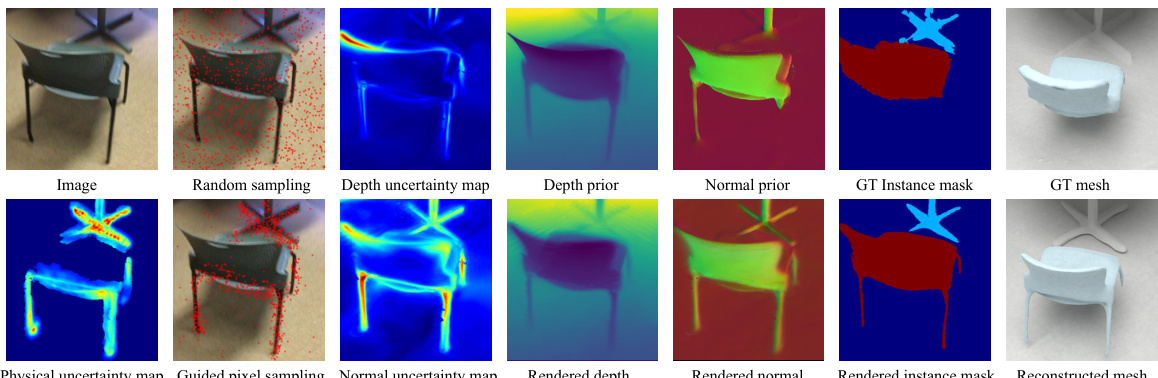

This figure shows a detailed breakdown of the joint uncertainty modeling process in PHYRECON. It visually demonstrates how physical uncertainty helps identify areas needing structural support, guiding pixel sampling towards finer details. Meanwhile, rendering uncertainties mitigate inconsistencies from multi-view geometry priors, leading to a more accurate reconstruction than the ground truth mesh.

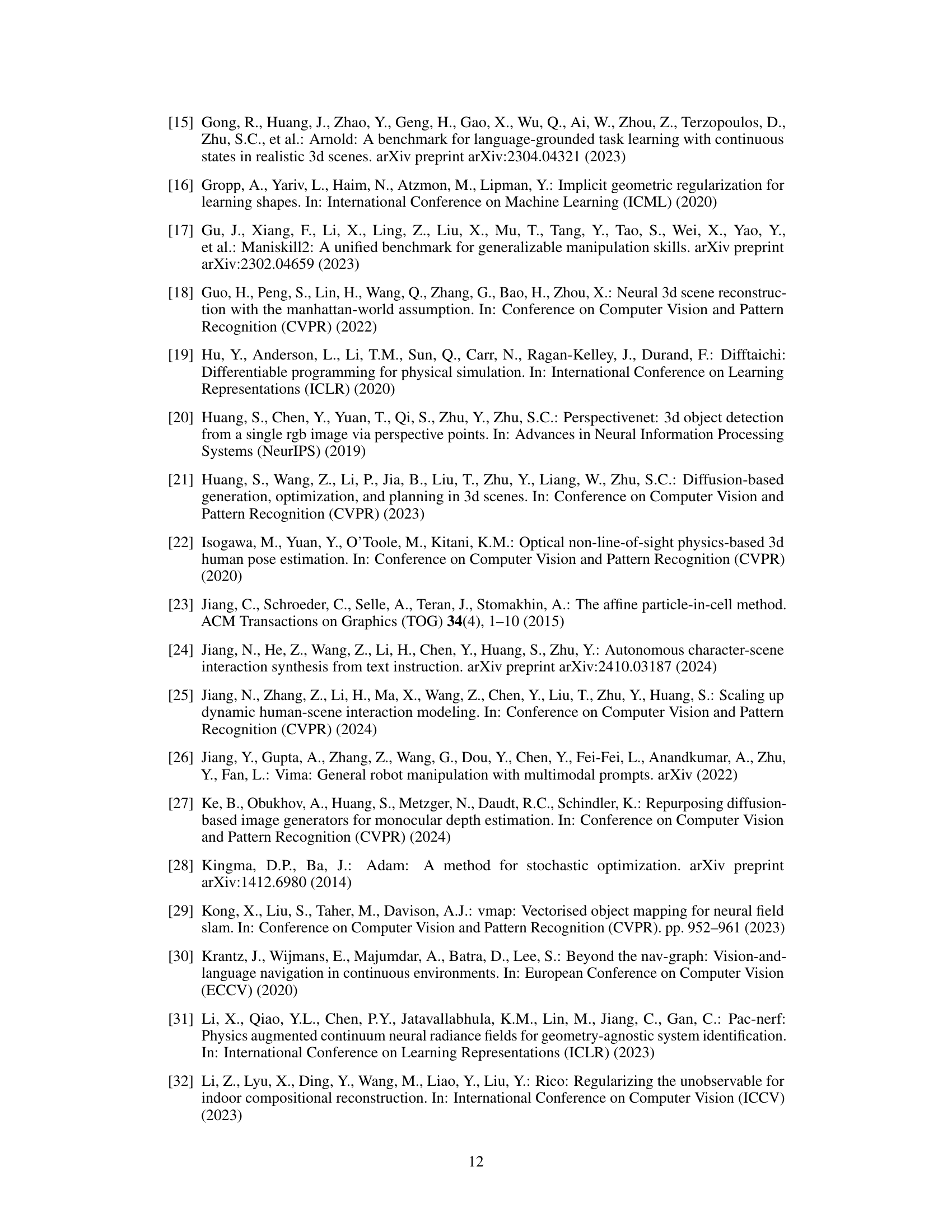

This figure shows a visual comparison of the ablation study. It compares the results of using different combinations of the physical loss (PL), rendering uncertainty (RU), physical uncertainty (PU), and physics-guided pixel sampling (PS). The (a) Baseline column shows results without any of these components. Subsequent columns show the results of adding each component in sequence. The final column (f) shows the results of the complete PHYRECON model, which incorporates all four components. The comparison highlights the impact of each component on the reconstruction quality, particularly regarding the stability and detail of thin structures such as chair legs.

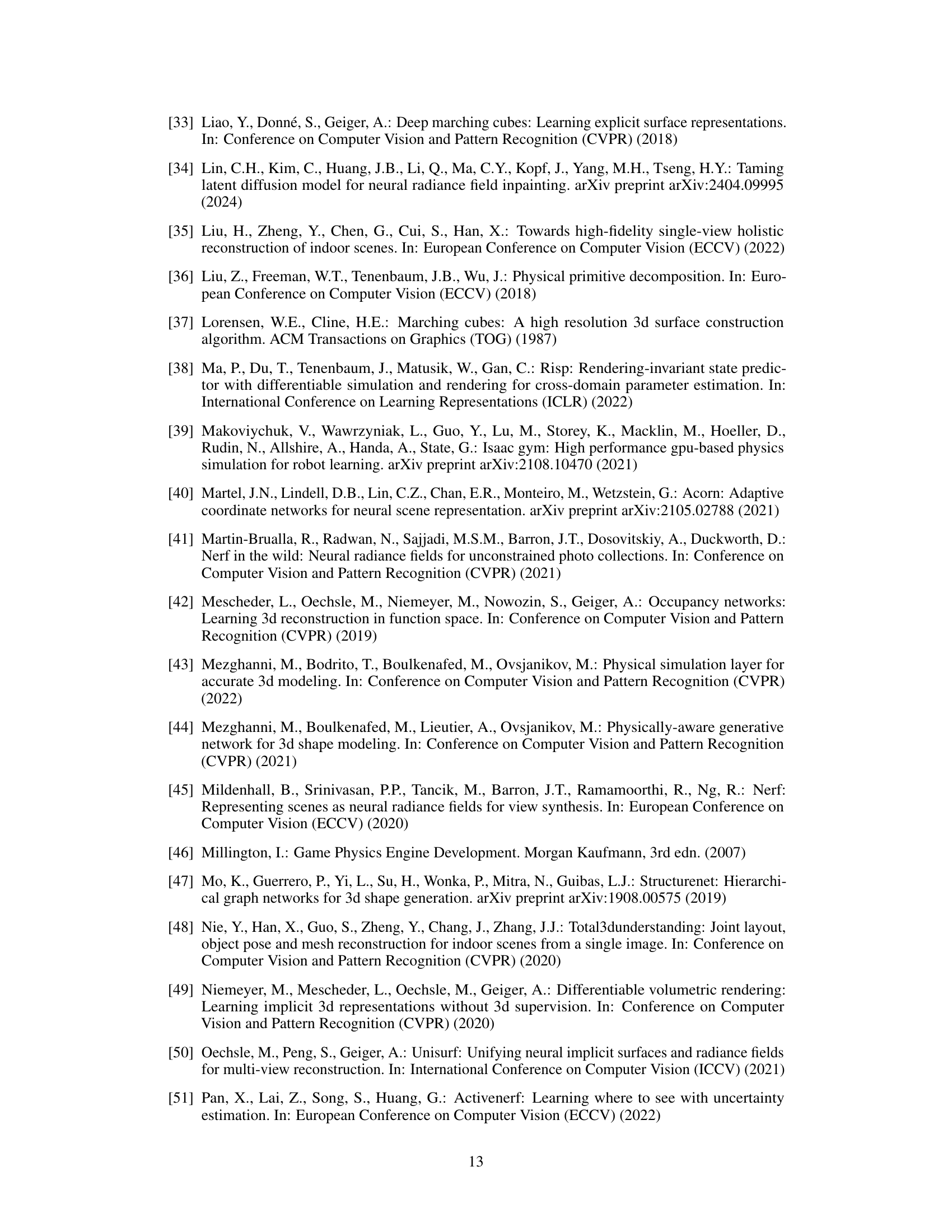

This figure shows two examples where the proposed method fails. (a) shows a scene with a chair whose legs are not fully reconstructed, leading to instability. (b) shows an example where the objects are divided into several disconnected parts, resulting in instability and lack of structural integrity. These cases highlight the challenges in achieving physically plausible reconstruction, particularly for thin structures and complex object interactions.

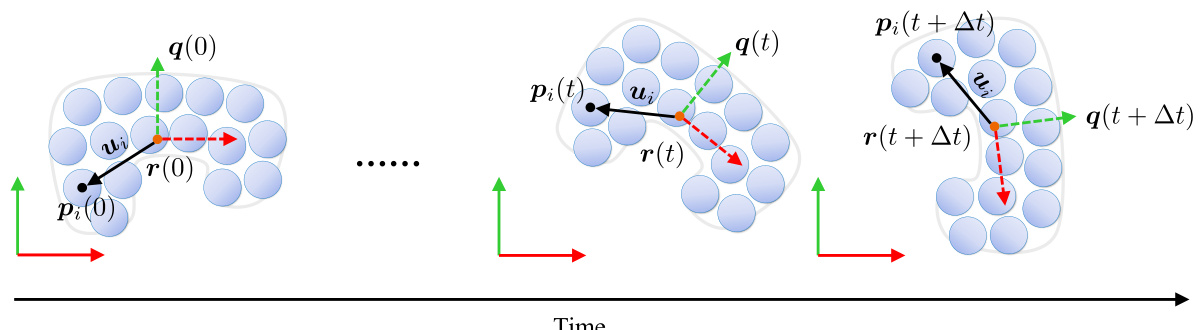

This figure illustrates the dynamics of a rigid body represented as a collection of particles. The world coordinate system is shown in solid lines, while the rigid body’s coordinate system (which moves with the body) is shown in dashed lines. The figure shows three points in time: the initial state (t=0), an intermediate state (t), and the final state after a time step Δt (t+Δt). The movement of the rigid body’s center of mass (r) and its orientation (q) are shown by red and green dashed arrows respectively. The movement of individual particles (Pi) within the rigid body is also shown. This illustration helps explain how the simulator calculates the rigid body’s dynamics based on the forces acting on each particle.

This figure illustrates the architecture of PHYRECON, highlighting the key components: differentiable rendering, differentiable physics simulation, and joint uncertainty modeling. It shows how monocular cues are used to inform the neural implicit surface representation, which is then refined through both rendering and physical losses. The SP-MC module enables differentiable transformation between implicit surfaces and explicit surface points, facilitating the physics simulation. The model incorporates rendering and physical uncertainty to address inconsistencies and guide pixel sampling, leading to improved reconstruction quality, especially for intricate and slender structures.

More on tables

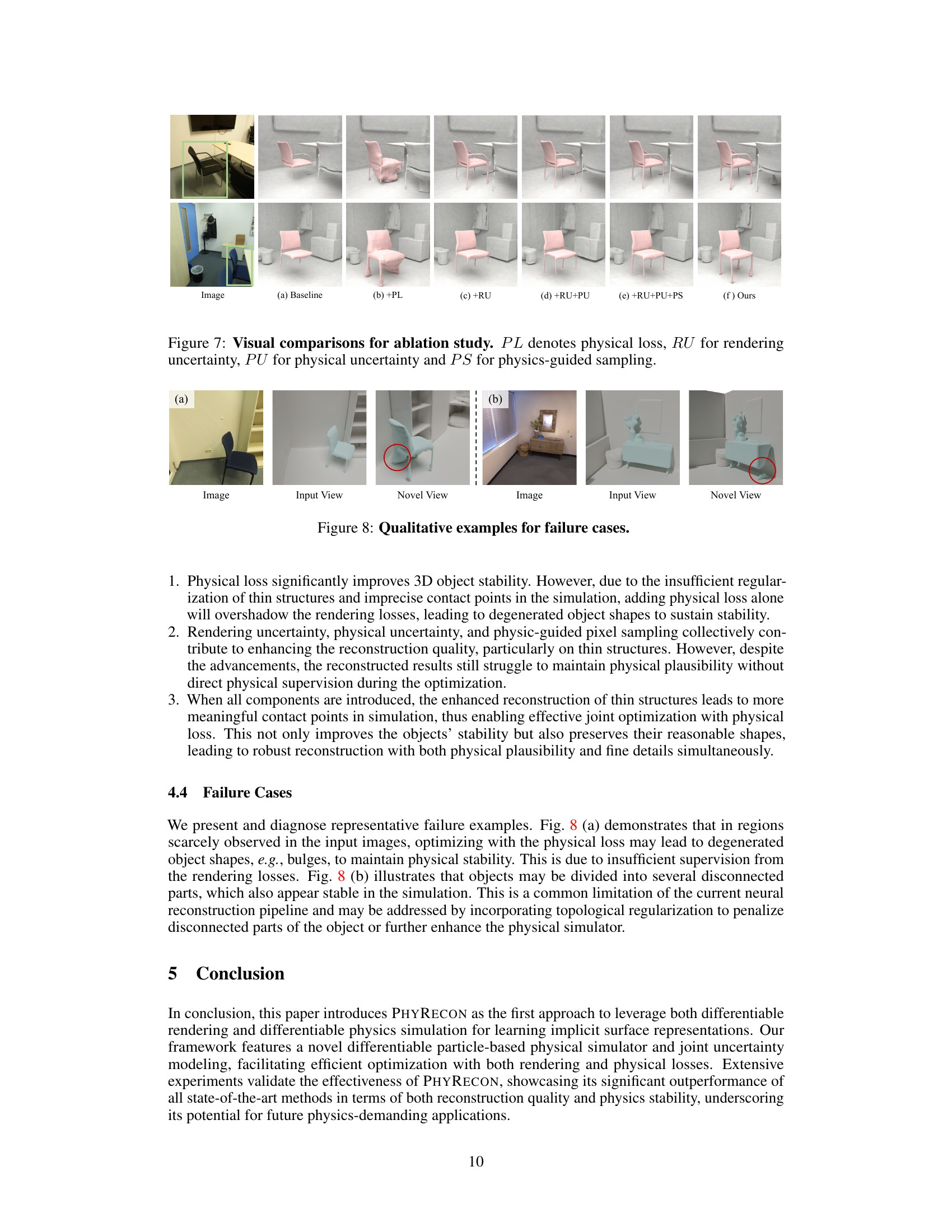

This table presents the ablation study results on the ScanNet++ dataset. It shows the impact of each component (rendering uncertainty (RU), physical uncertainty (PU), physics-guided pixel sampling (PS), and physical loss (PL)) on the overall performance. The metrics used are Chamfer Distance (CD), F-score, Normal Consistency (NC), and Object Stability (SR). The results demonstrate the importance of each component for improving reconstruction quality and physical stability. The final row shows the performance of PHYRECON with all components integrated.

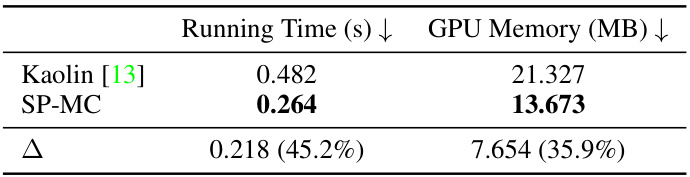

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of the proposed Surface Points Marching Cubes (SP-MC) algorithm against the Kaolin algorithm [13] in terms of running time and GPU memory consumption. The comparison highlights the efficiency gains achieved by SP-MC in extracting surface points from a signed distance function (SDF). The results show that SP-MC is significantly faster and requires less GPU memory than Kaolin.

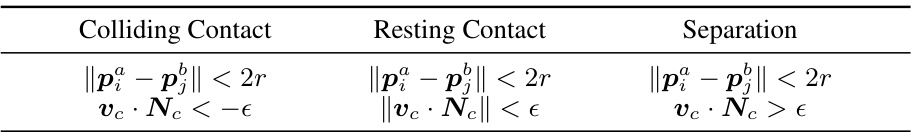

This table presents three different contact states between rigid bodies in the physics simulation: Colliding Contact, Resting Contact, and Separation. For each state, it provides specific criteria based on the distance between the particles (’||pai - pbj|| < 2r’) and the relative velocity at the contact points (‘vc • Nc’). The criteria help distinguish between the three states during the simulation process.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of 3D reconstruction results across different datasets (ScanNet++, ScanNet, Replica) and methods (MonoSDF, RICO, ObjectSDF++, PHYRECON). It shows the Chamfer Distance (CD), F-score, and Normal Consistency (NC) for both scene and object reconstruction, providing a comprehensive evaluation of reconstruction quality. Furthermore, it includes the Object Stability (SR), indicating the percentage of objects that remain stable in a physical simulation, highlighting PHYRECON’s improved physical plausibility.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed PHYRECON model against three baseline methods (MonoSDF, RICO, ObjectSDF++) across three datasets (ScanNet++, ScanNet, Replica). The metrics used are Chamfer Distance (CD), F-Score, Normal Consistency (NC), and Object Stability (SR). Lower CD values indicate better reconstruction quality, while higher F-Score and NC values suggest better accuracy and consistency. The SR metric, expressed as a percentage, signifies an improvement in the physical stability of reconstructed objects when evaluated using a physical simulator.

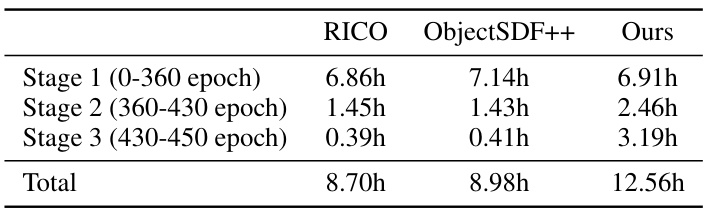

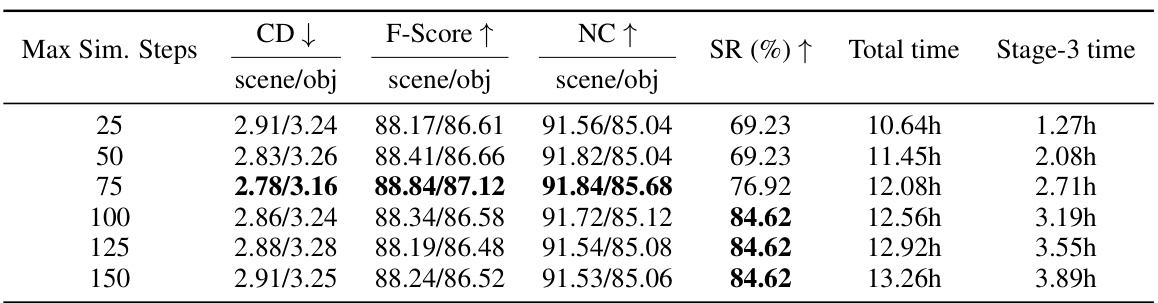

This table presents the results of a sensitivity analysis conducted to determine the impact of varying the maximum number of simulation steps on the performance of the physics-based simulation. The metrics evaluated include Chamfer Distance (CD), F-score, Normal Consistency (NC), Stability Ratio (SR), and the total time taken for the simulation. The analysis shows that increasing the maximum number of steps generally improves the final stability of the objects, although this effect diminishes significantly once the maximum steps exceed 100, and the total simulation time increases.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of 3D reconstruction results across three datasets (ScanNet++, ScanNet, and Replica) using four different methods: MonoSDF, RICO, ObjectSDF++, and the proposed PHYRECON. For each method and dataset, it reports the Chamfer Distance (CD), F-score, Normal Consistency (NC), and Object Stability (SR). Lower CD values indicate better reconstruction accuracy. Higher F-score, NC, and SR values indicate better performance. PHYRECON achieves the best performance in all metrics, notably significantly improving physical stability compared to existing methods.

Full paper#