TL;DR#

Remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) uses imaging to extract blood volume pulse signals, converting spatial-temporal data into time series. Existing rPPG methods often compute attention separately across spatial, temporal, and channel dimensions, limiting their accuracy and ability to generalize across different datasets. This creates a need for a more comprehensive approach to multidimensional attention that can improve rPPG signal estimation.

This research proposes FactorizePhys, which uses a novel Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM). FSAM computes multidimensional attention by jointly processing spatial-temporal information using nonnegative matrix factorization. FactorizePhys shows significantly improved accuracy and cross-dataset generalization compared to other rPPG methods. Ablation studies confirm the effectiveness of the architectural decisions and hyperparameters in FSAM, highlighting its potential as a broadly applicable multidimensional attention mechanism.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in remote physiological sensing because it introduces a novel multidimensional attention mechanism, FSAM, that significantly improves the accuracy and generalizability of rPPG signal estimation. FSAM’s unique approach to matrix factorization offers a new way to handle the complexity of spatial-temporal data, which is directly relevant to current research trends that emphasize advanced attention mechanisms. This work also opens up exciting avenues for further investigation into the application of matrix factorization in other deep learning tasks and its potential benefits for cross-dataset generalization.

Visual Insights#

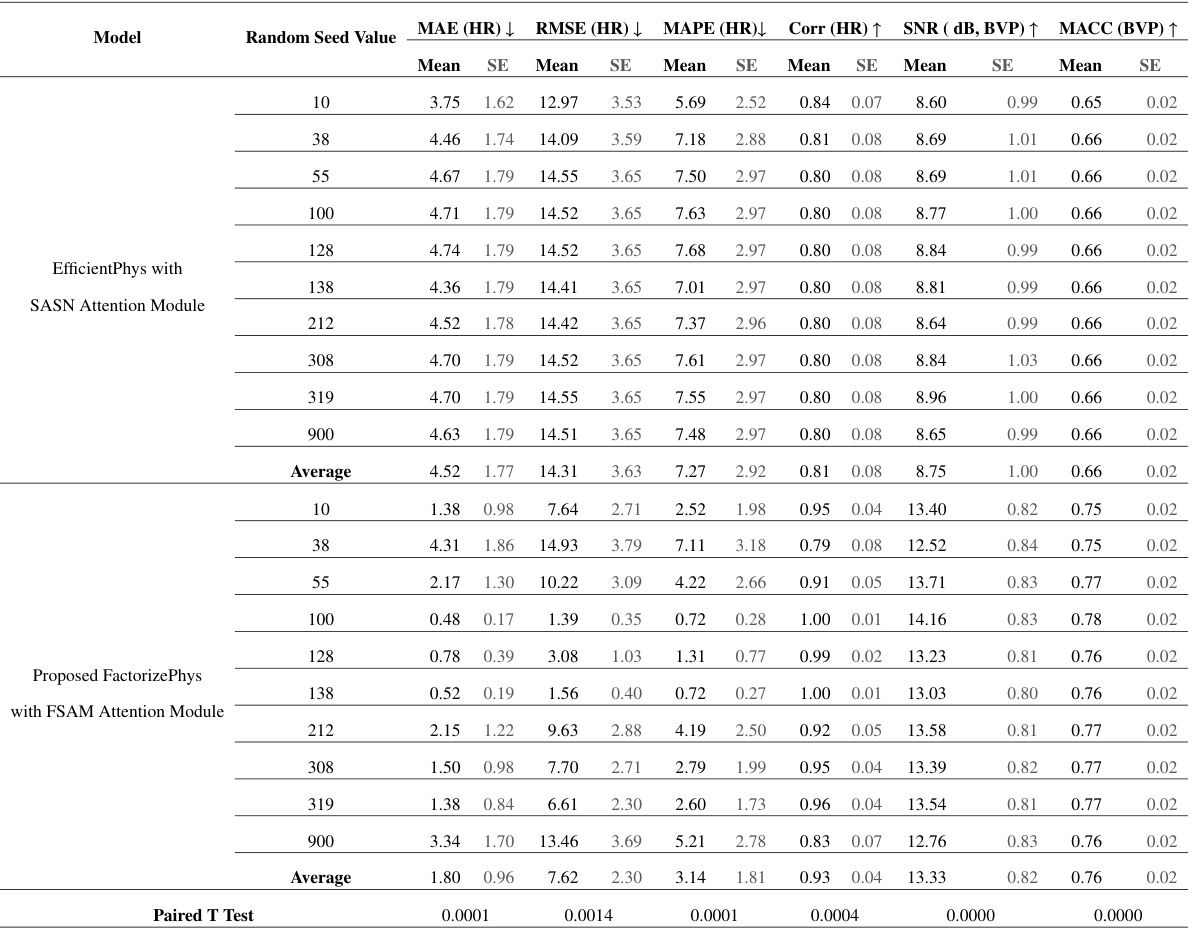

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF). NMF decomposes a large matrix (V) into two smaller matrices (W and H). Matrix W represents the basis matrix, containing the basis vectors, while matrix H represents the coefficient matrix, indicating how much each basis vector contributes to each column of the original matrix. The process aims to approximate the original matrix V as closely as possible by the product of W and H, resulting in an approximated matrix V. The difference between the original matrix V and the approximated matrix V is represented by the error matrix E.

read the caption

Figure 1: Formulation of Nonnegative Matrix Factorization (NMF)

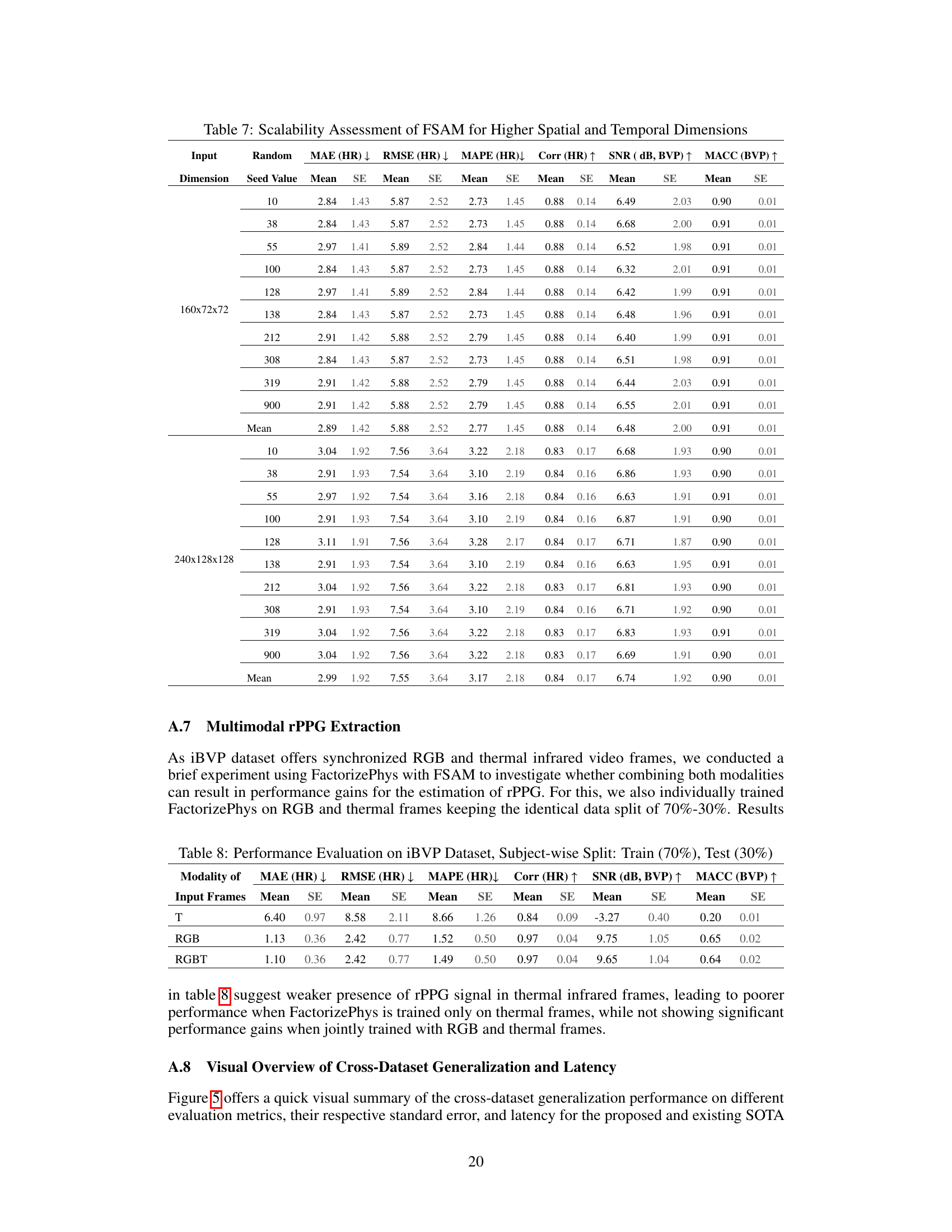

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study that investigates the effect of different mappings of voxel embeddings to the factorization matrix on the performance of the FactorizePhys model. The study explores three different mappings: 1) Mapping temporal features to M and spatial-channel features to N; 2) mapping channel features to M and spatial-temporal features to N; and 3) mapping spatial features to N and temporal-channel features to M. The results are evaluated in terms of MAE(HR), RMSE(HR), MAPE(HR), Corr(HR), SNR(BVP), and MACC(BVP) on three different datasets: PURE, UBFC-rPPG, and iBVP. The goal is to determine the optimal mapping for achieving the best performance in rPPG estimation.

read the caption

Table 1: Ablation Study for Different Mapping of Voxel Embeddings to Factorization Matrix

In-depth insights#

rPPG Attention#

Remote PPG (rPPG) signal extraction from videos heavily relies on attention mechanisms to effectively filter relevant information and suppress noise. Multidimensional attention, considering spatial, temporal, and spectral domains simultaneously, is crucial for robust performance. Traditional approaches often treat these dimensions separately, limiting their effectiveness. The core challenge lies in developing methods that effectively combine these dimensions to create a comprehensive representation of the data, crucial for accurate pulse estimation. A promising direction involves matrix factorization techniques, which can uncover latent relationships within multidimensional rPPG data and enhance the signal’s discriminative features. Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) is particularly well-suited due to its ability to discover parts-based representations in non-negative data. Furthermore, attention modules based on NMF present a computationally efficient and effective alternative to more complex attention methods, particularly relevant when dealing with high-dimensional rPPG data often seen in video-based extraction.

FSAM: NMF Power#

The heading “FSAM: NMF Power” suggests an exploration of the capabilities of the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) leveraging Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF). The core idea appears to be harnessing NMF’s dimensionality reduction and parts-based representation properties to enhance the attention mechanism. Instead of calculating attention separately across spatial, temporal, and channel dimensions, FSAM likely uses NMF to jointly compute multidimensional attention from voxel embeddings. This approach could offer advantages such as improved computational efficiency and the ability to capture complex interactions between different feature dimensions. The “power” aspect likely refers to the effectiveness of this integrated approach in tasks such as remote physiological signal (rPPG) estimation, potentially leading to better accuracy, robustness, and generalizability compared to traditional, disjoint attention mechanisms. A key contribution may be demonstrating that NMF-based FSAM provides a computationally efficient alternative to more complex attention methods while achieving comparable or superior performance.

3D-CNN Design#

A 3D-CNN architecture presents a unique opportunity to leverage the inherent spatiotemporal correlations in video data for rPPG signal extraction. The design choices within the 3D-CNN are crucial: kernel size, number of layers, and the use of techniques like instance normalization and residual connections significantly impact model performance and efficiency. The use of 3D convolutions allows the model to effectively capture spatiotemporal features, but the computational cost increases compared to 2D-CNNs. Careful consideration must be given to balancing performance and efficiency. Furthermore, the integration of attention mechanisms, such as the proposed Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM), further enhances the model’s ability to focus on relevant features, leading to potentially improved accuracy and robustness. Ablation studies investigating these design choices are essential for optimizing the network architecture and achieving optimal performance.

Cross-Dataset Gains#

The concept of “Cross-Dataset Gains” in a research paper would revolve around evaluating a model’s ability to generalize well across multiple, distinct datasets. A strong model demonstrates consistent performance regardless of the specific dataset used for testing. Analysis of cross-dataset results would involve comparing various performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) across different datasets. Significant improvements on unseen test sets compared to training sets highlight strong generalization. The discussion might explore reasons for these gains, such as robust architectural design, effective attention mechanisms, and perhaps even dataset characteristics. Conversely, performance degradation on certain test sets would signal limitations in the model’s generalization ability and potentially indicate areas needing further improvement in the model’s design or training methodology. The presence or absence of cross-dataset gains is a critical indicator of a model’s robustness and practical applicability.

Future of FSAM#

The Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) presents a promising avenue for multidimensional attention mechanisms. Future research could explore FSAM’s adaptability to various architectures beyond 2D and 3D CNNs, such as transformers or graph neural networks. Investigating its performance on a wider range of physiological signals beyond rPPG, like EEG or EMG, would further validate its versatility. Optimizing FSAM’s computational efficiency, especially for high-resolution data or real-time applications, is crucial. The impact of different NMF variants and the optimal rank selection for diverse tasks also warrants further study. Finally, thorough investigation into the interpretability of FSAM’s learned features could unlock deeper insights into physiological processes and lead to more advanced signal processing techniques.

More visual insights#

More on figures

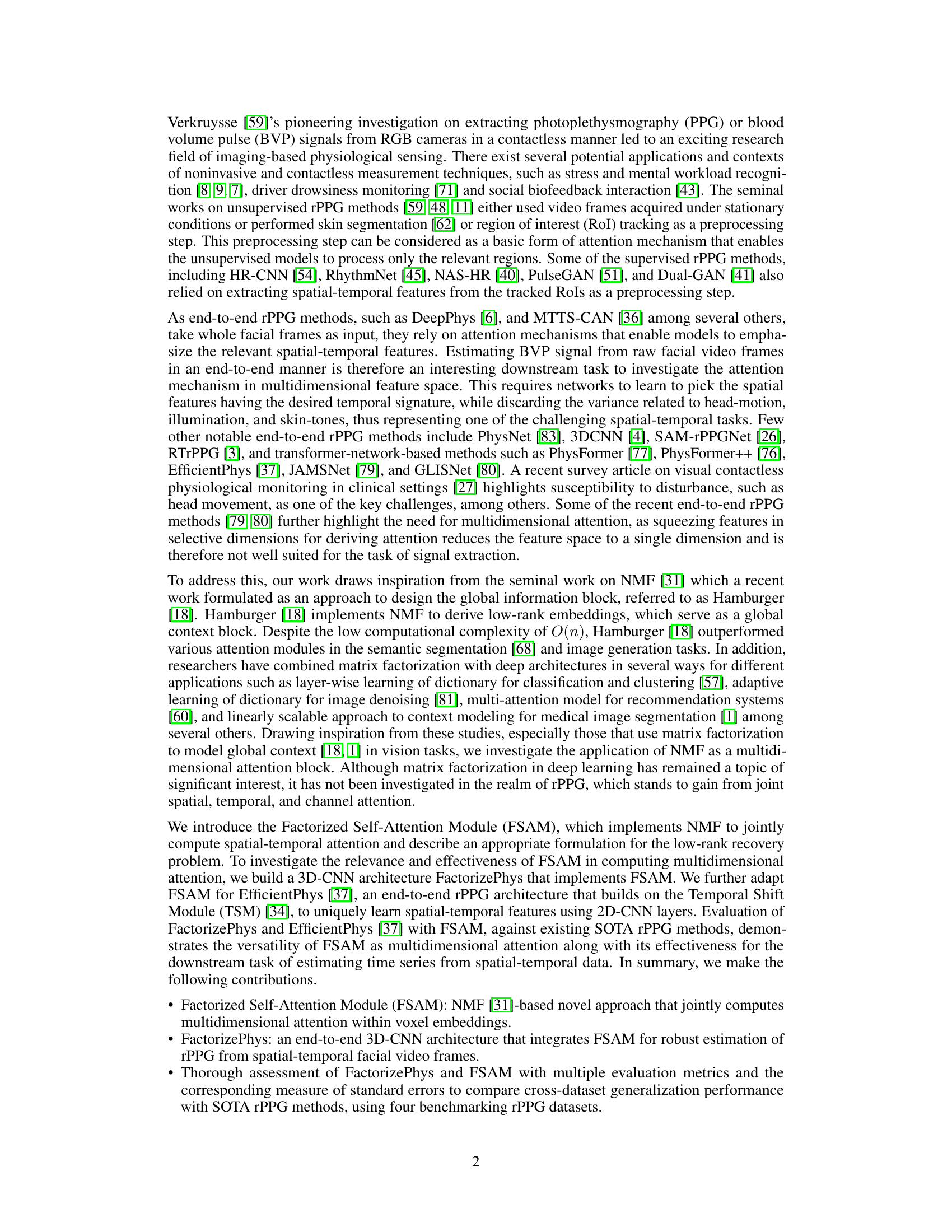

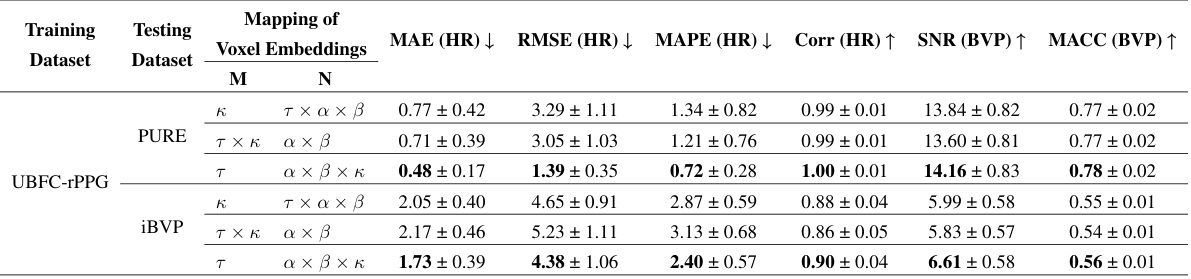

🔼 This figure illustrates the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) within a 3D-CNN architecture designed for remote PPG (rPPG) signal estimation. It shows how voxel embeddings from a video frame are transformed into a factorization matrix using a transformation function (Γκαβ↔MN). Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) is then applied to this matrix to obtain a low-rank approximation, which is transformed back into the embedding space. This approximated embedding is then used with instance normalization and residual connections to refine the voxel embeddings, eventually leading to an estimated blood volume pulse (BVP) signal.

read the caption

Figure 2: Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) illustrated for a 3D-CNN architecture for rPPG estimation.

🔼 This figure illustrates the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) within a 3D-CNN architecture designed for remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) estimation. The diagram shows the flow of data through the network, starting with raw video frames. The frames undergo a difference operation (Diff) to remove stationary components, followed by instance normalization. Then, voxel embeddings are generated and passed through the FSAM, which utilizes Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) for multi-dimensional attention. The output of the FSAM is then fed into the network head, which produces an estimated blood volume pulse (BVP) signal. The FSAM is highlighted as a key component, showing how it combines spatial, temporal, and channel information to enhance the accuracy of the rPPG estimation.

read the caption

Figure 2: Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) illustrated for a 3D-CNN architecture for rPPG estimation.

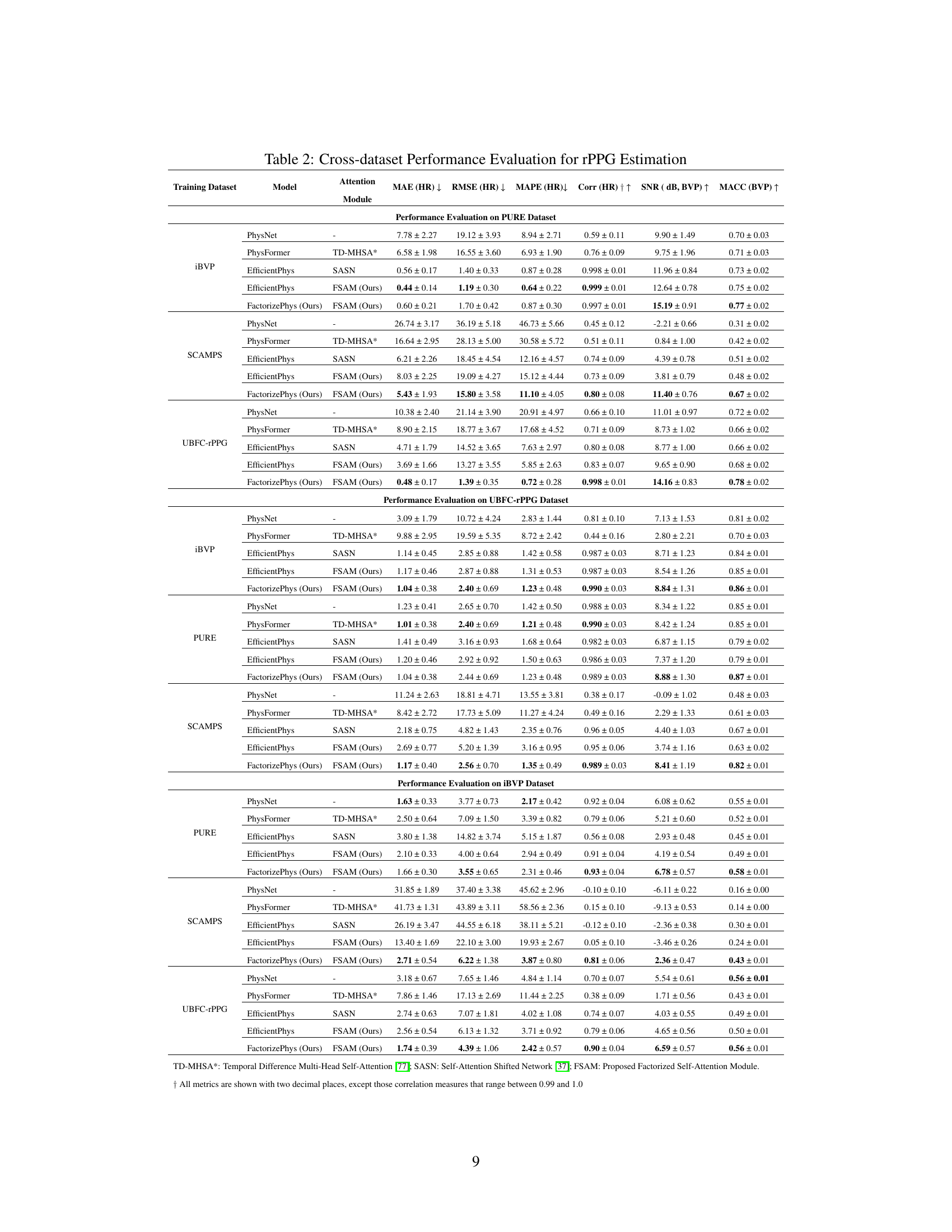

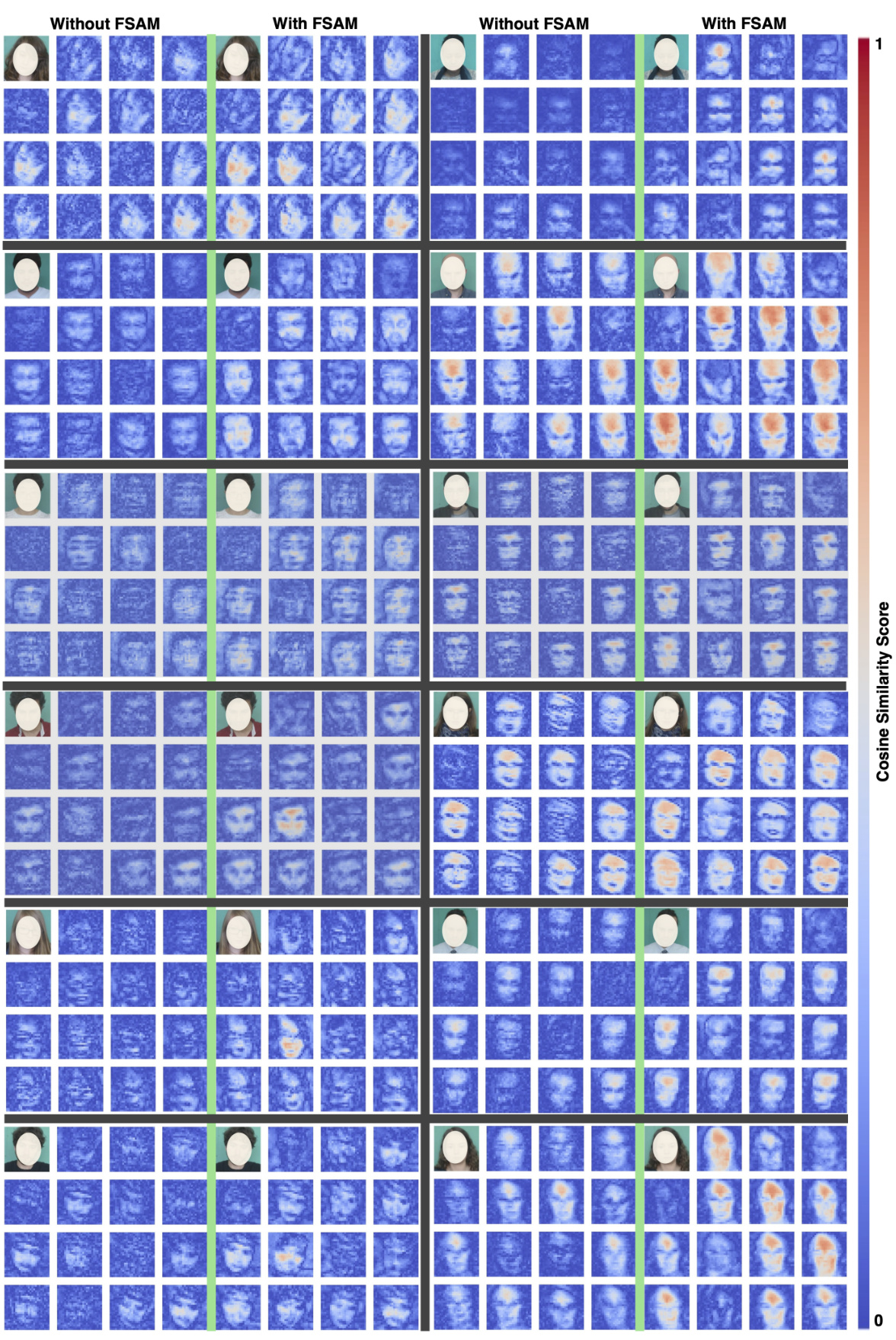

🔼 Figure 4 presents a comparison of the performance (MAE) against latency for various models, including FactorizePhys with and without FSAM. The size of the spheres corresponds to the number of parameters used by each model. Panel B shows a visualization of the learned spatial-temporal features to illustrate the effects of FSAM on attention mechanisms. It compares feature maps from a 3D-CNN model trained without FSAM (left) and with FSAM (right). The color intensity in these maps represents the cosine similarity scores between the learned features and the ground truth rPPG signal, highlighting how the model focuses on salient features.

read the caption

Figure 4: (A) Cumulative cross-dataset performance (MAE) v/s latency† plot. The size of the sphere corresponds to the number of model parameters; (B) Visualization of learned spatial-temporal features from the base 3D-CNN model trained without and with FSAM; † System specs: Ubuntu 22.04 OS, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 Laptop GPU, Intel® Core™ i7-10870H CPU @ 2.20GHz, 16 GB RAM.

🔼 This figure illustrates the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) within a 3D-CNN architecture designed for remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) signal estimation. The diagram shows the flow of data through the network, highlighting the steps involved in the FSAM. The input is raw video frames, which are processed through a feature extractor to produce voxel embeddings. These embeddings are then transformed into a matrix suitable for nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF), which is the core of the FSAM. The NMF produces low-rank approximations of the embeddings, capturing salient spatial-temporal features. These low-rank embeddings are then transformed back to the embedding space, combined with the original embeddings via a residual connection, and passed through a network head to produce the final rPPG signal. The figure provides a visual representation of how FSAM integrates with the 3D-CNN architecture to jointly compute spatial-temporal and channel attention, enhancing the estimation of the blood volume pulse signal from raw video.

read the caption

Figure 2: Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) illustrated for a 3D-CNN architecture for rPPG estimation.

🔼 This figure visualizes the learned spatial-temporal features from FactorizePhys, a 3D-CNN model, with and without the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM). The visualization uses a heatmap to represent the cosine similarity between the temporal dimension of the 4D embeddings (containing temporal, spatial, and channel dimensions) and the ground-truth signal for each channel. Higher cosine similarity scores indicate higher saliency of temporal features. The figure shows that FactorizePhys trained with FSAM demonstrates higher selectivity and better representation of salient spatial features, especially in challenging scenarios with occlusions.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visualization of Learned Spatial-Temporal Features

🔼 This figure illustrates the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) within a 3D-CNN architecture designed for remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) estimation. It shows the flow of data through the network, highlighting the key steps of voxel embedding generation, transformation into a factorization matrix using a voxel transformation, application of nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) within the FSAM to compute attention jointly across spatial, temporal, and channel dimensions, transformation back into the approximated embedding space, residual connection, and finally, the estimation of the blood volume pulse signal (PPG).

read the caption

Figure 2: Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) illustrated for a 3D-CNN architecture for rPPG estimation.

🔼 The figure illustrates the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) within a 3D-CNN architecture designed for remote PPG (rPPG) estimation. It shows the flow of data from input video frames through a feature extractor to voxel embeddings. These embeddings are then transformed into a factorization matrix for Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF), which computes a low-rank approximation. This approximation is transformed back to the embedding space and then used for a multidimensional self-attention mechanism involving spatial, temporal, and channel dimensions. This attention mechanism enhances the performance of the rPPG signal extraction. Finally, the approximated embeddings are passed through a network head to produce the estimated BVP (blood volume pulse) signal.

read the caption

Figure 2: Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) illustrated for a 3D-CNN architecture for rPPG estimation.

🔼 This figure illustrates the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) within a 3D-CNN architecture designed for remote photoplethysmography (rPPG) estimation. It shows the flow of data from input video frames through feature extraction, voxel embedding, transformation to factorization matrix using NMF, computation of low-rank matrix, transformation back to approximated embeddings, residual connection, and finally, to the network head for BVP signal estimation. The diagram highlights the key components of FSAM, including the input voxel embeddings, the nonnegative matrix factorization process, and the generation of approximated embeddings which are then used in a residual connection. The output is the estimated blood volume pulse (BVP) signal.

read the caption

Figure 2: Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) illustrated for a 3D-CNN architecture for rPPG estimation.

More on tables

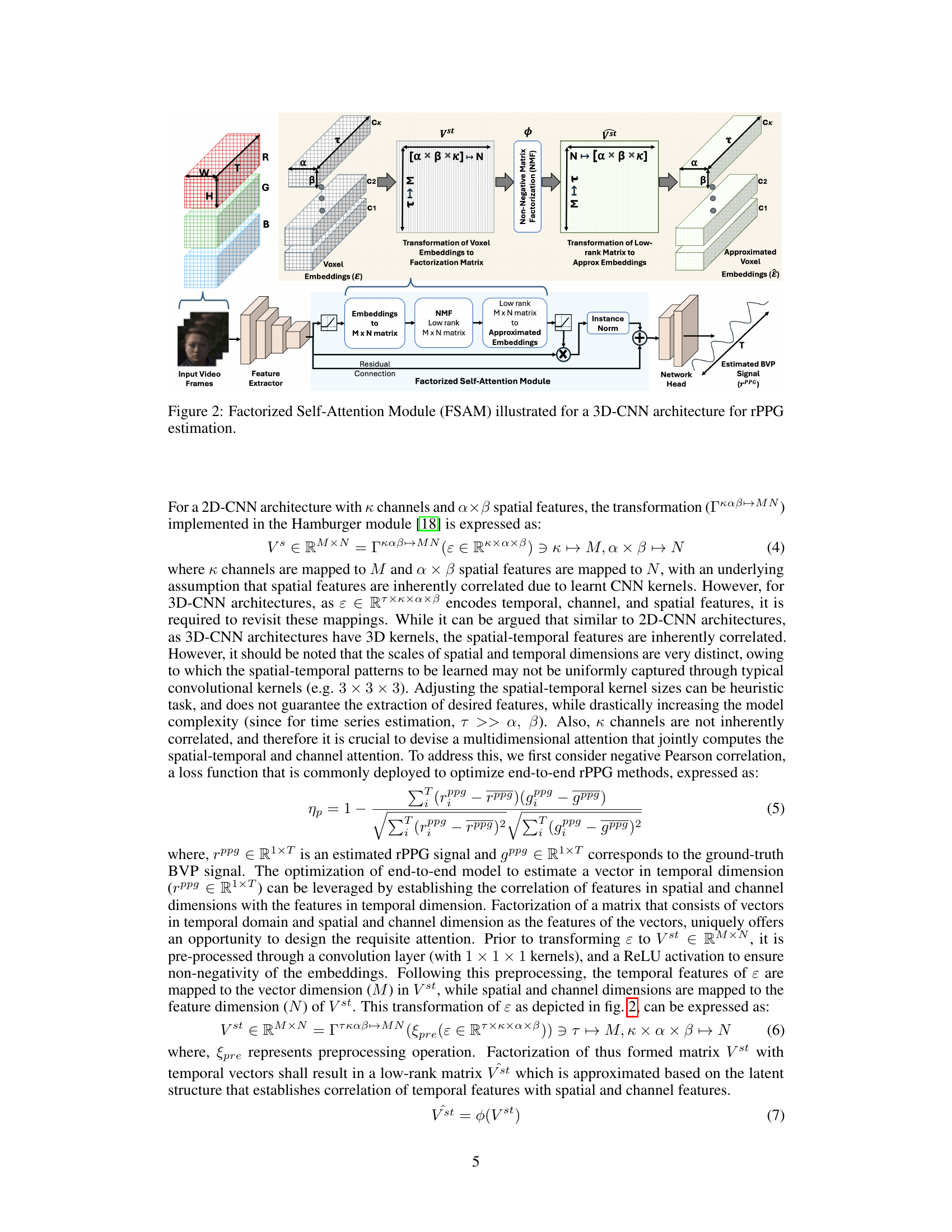

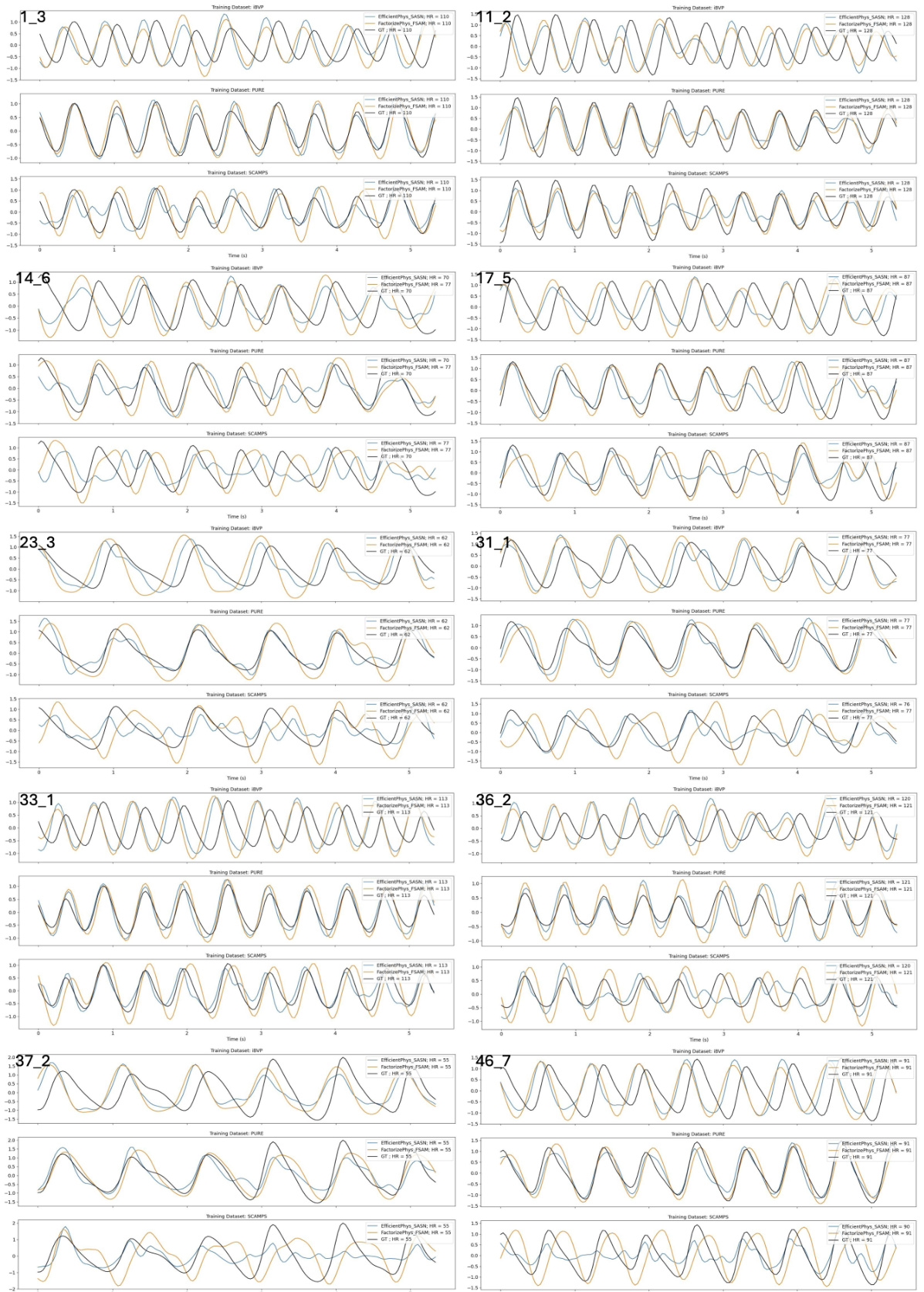

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive cross-dataset performance evaluation of the proposed FactorizePhys model with FSAM against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) rPPG methods. It shows the performance of different models (PhysNet, PhysFormer, EfficientPhys with SASN, EfficientPhys with FSAM, and FactorizePhys with FSAM) trained on one dataset and tested on three other datasets (PURE, UBFC-rPPG, and iBVP). The results are shown in terms of various metrics, including Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Correlation (Corr), Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), and Maximum Amplitude of Cross-Correlation (MACC) for both Heart Rate (HR) and Blood Volume Pulse (BVP). The standard errors are also provided to reflect the variability of the results.

read the caption

Table 2: Cross-dataset Performance Evaluation for rPPG Estimation

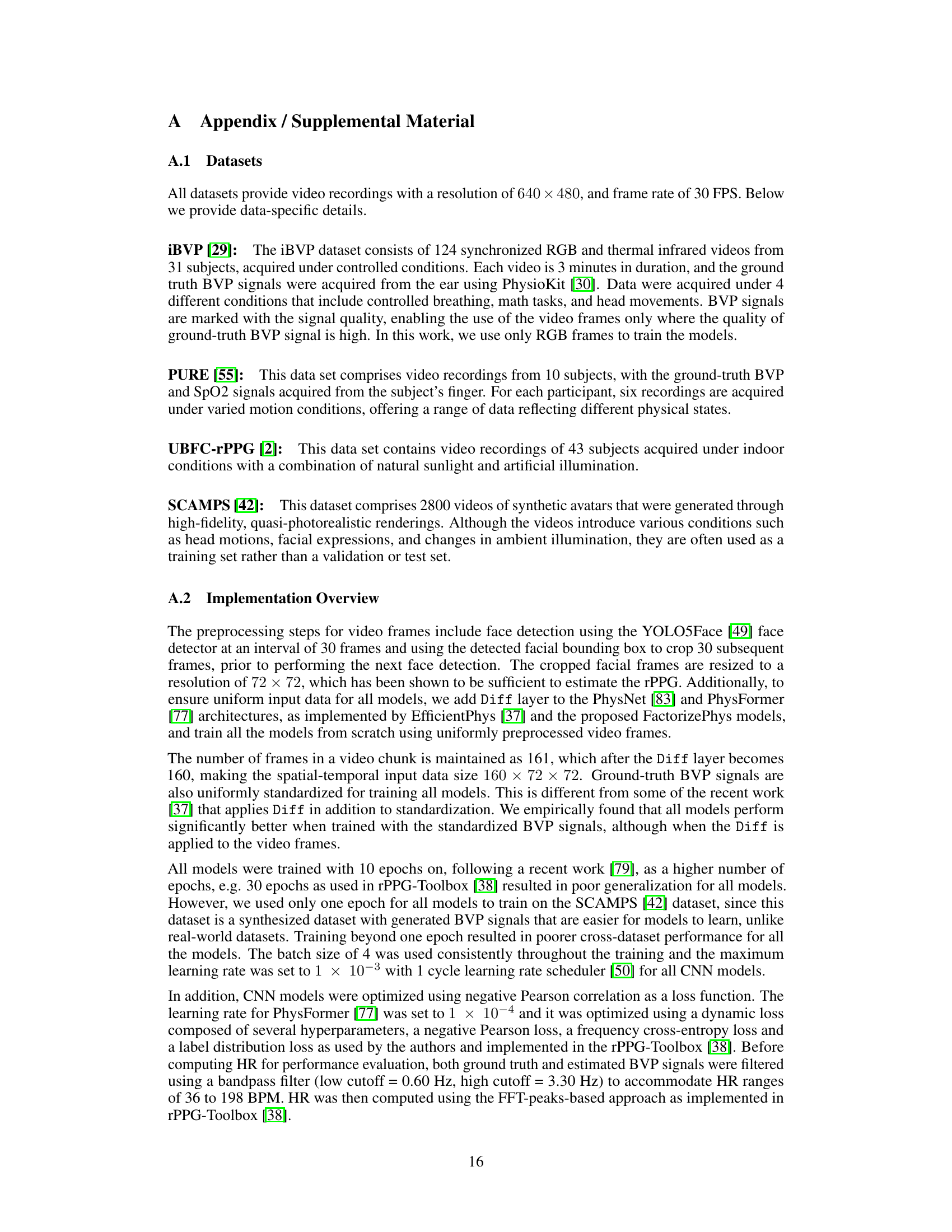

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of residual connections around the FSAM module and compares models trained with and without FSAM. It evaluates the models’ performance during inference with and without FSAM, demonstrating the effectiveness of FSAM even when not used during inference. The table shows performance metrics (MAE, RMSE, MAPE, Corr, SNR, MACC) for different model configurations on various datasets.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study to assess residual connection to FSAM Module, and to compare the models trained with FSAM, for their inferences without FSAM

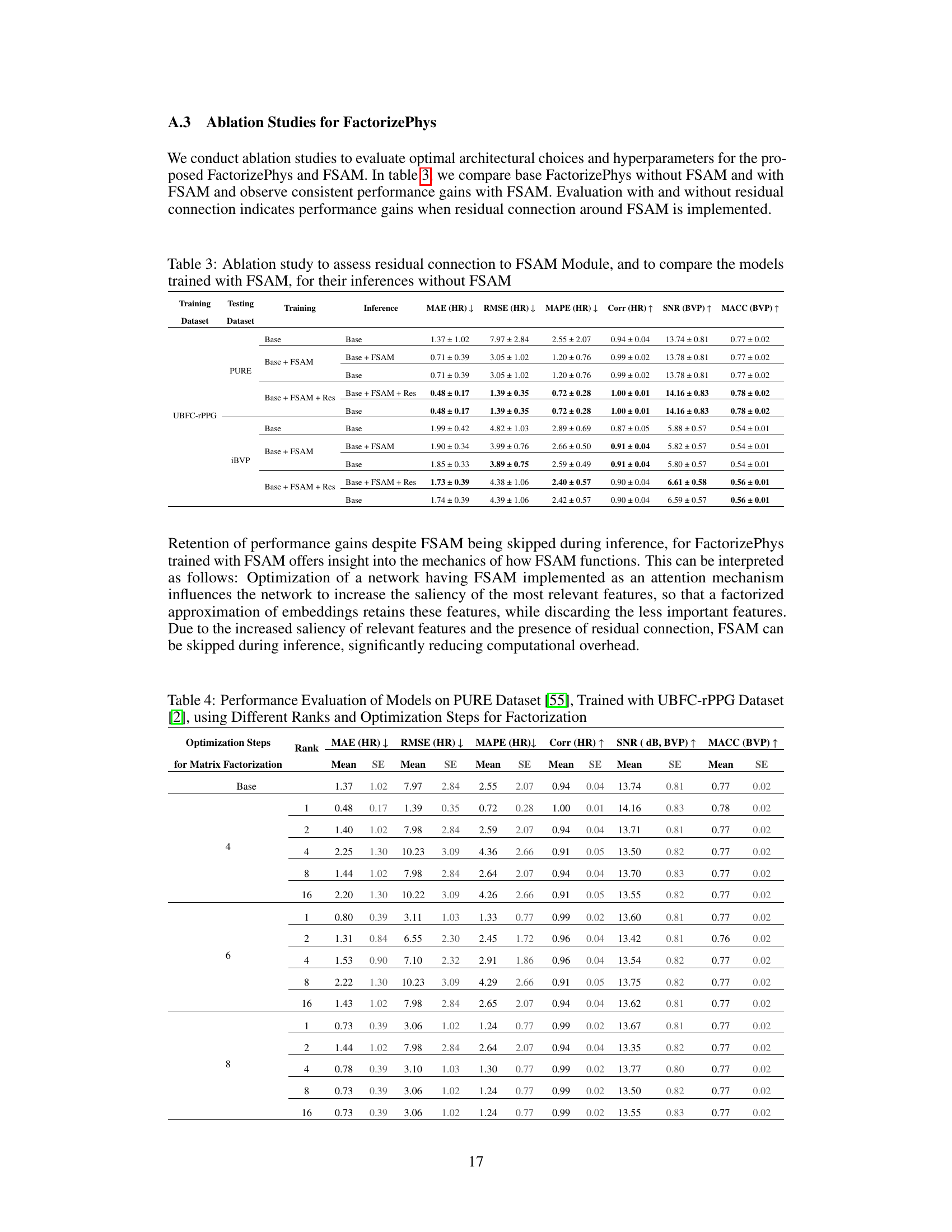

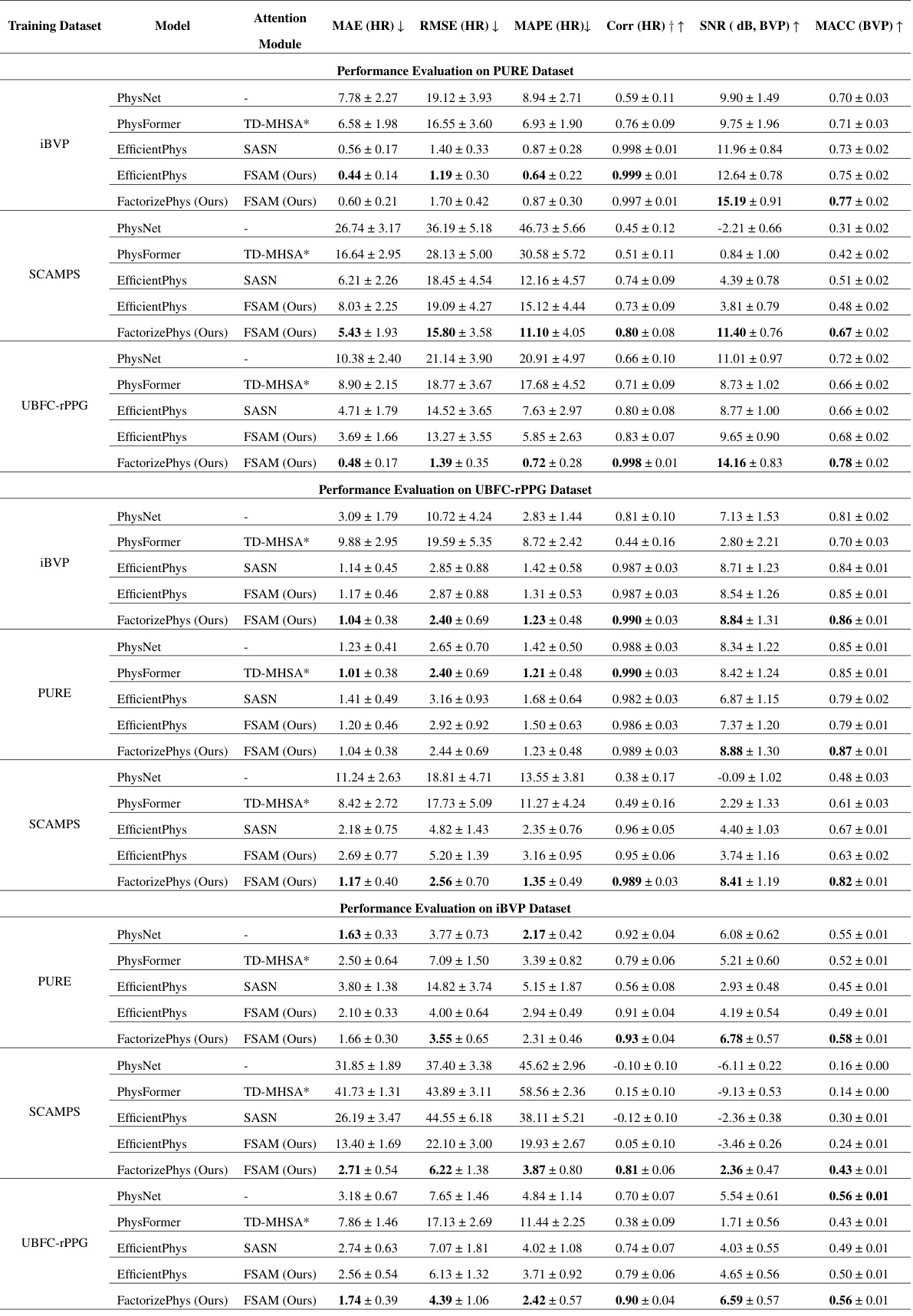

🔼 This table presents ablation study results on the PURE dataset. It shows the impact of using different ranks (1, 2, 4, 8, 16) in the nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) process within the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM), and varying the number of optimization steps (4, 6, 8) for the NMF. The results are evaluated using MAE (HR), RMSE (HR), MAPE (HR), Corr (HR), SNR (dB, BVP), and MACC (BVP). A base model without FSAM is also included for comparison.

read the caption

Table 4: Performance Evaluation of Models on PURE Dataset [55], Trained with UBFC-rPPG Dataset [2], using Different Ranks and Optimization Steps for Factorization

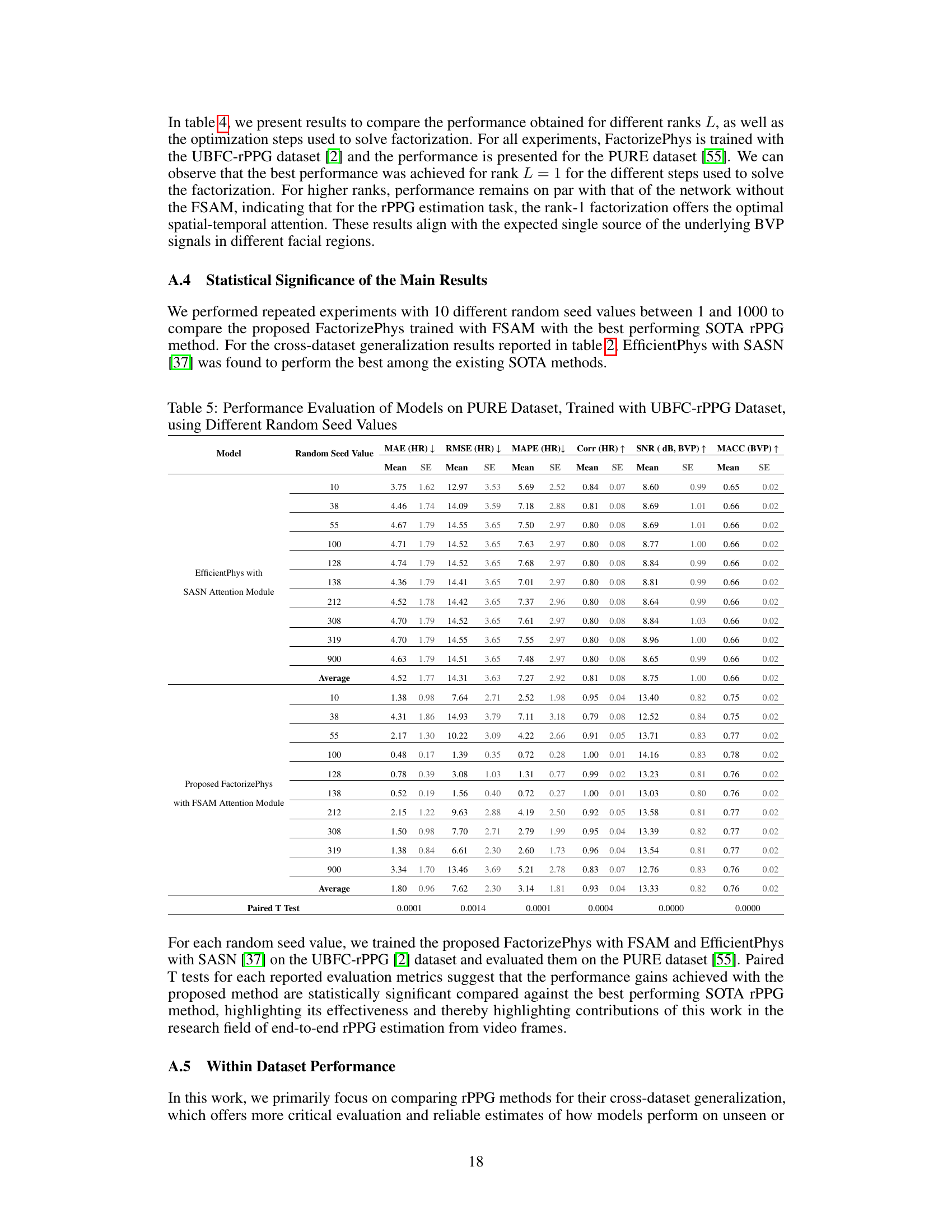

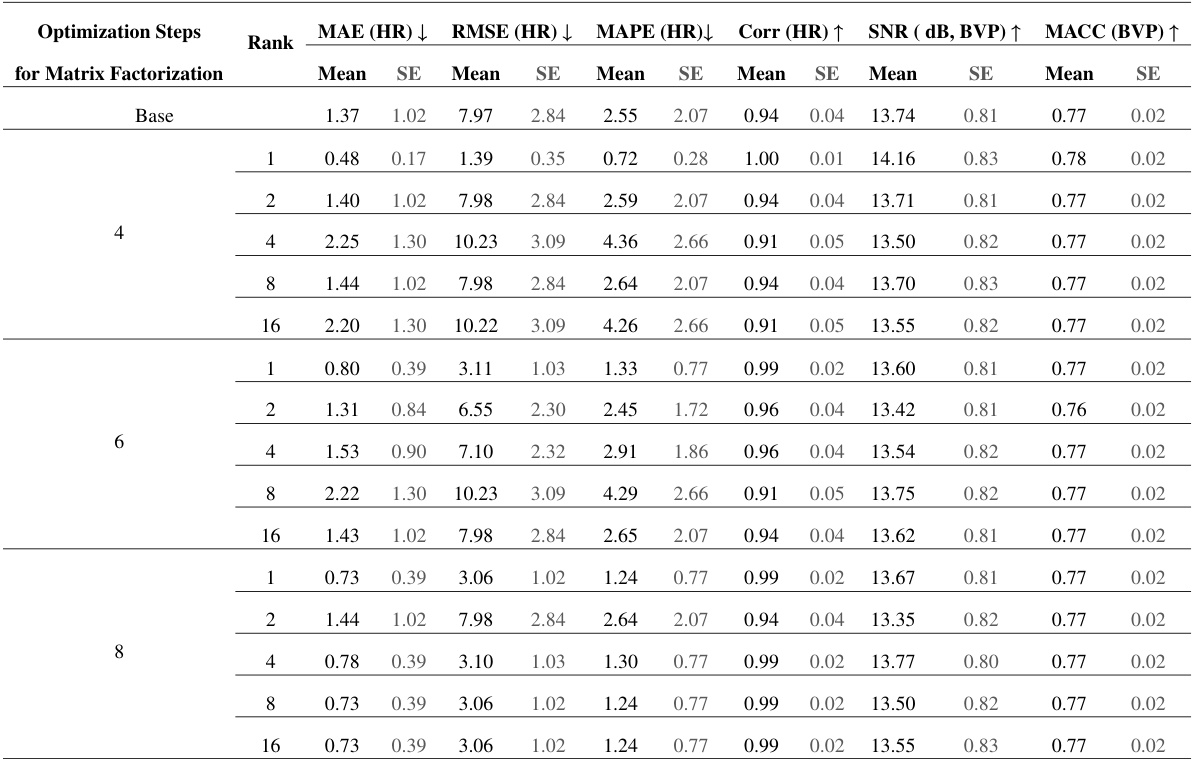

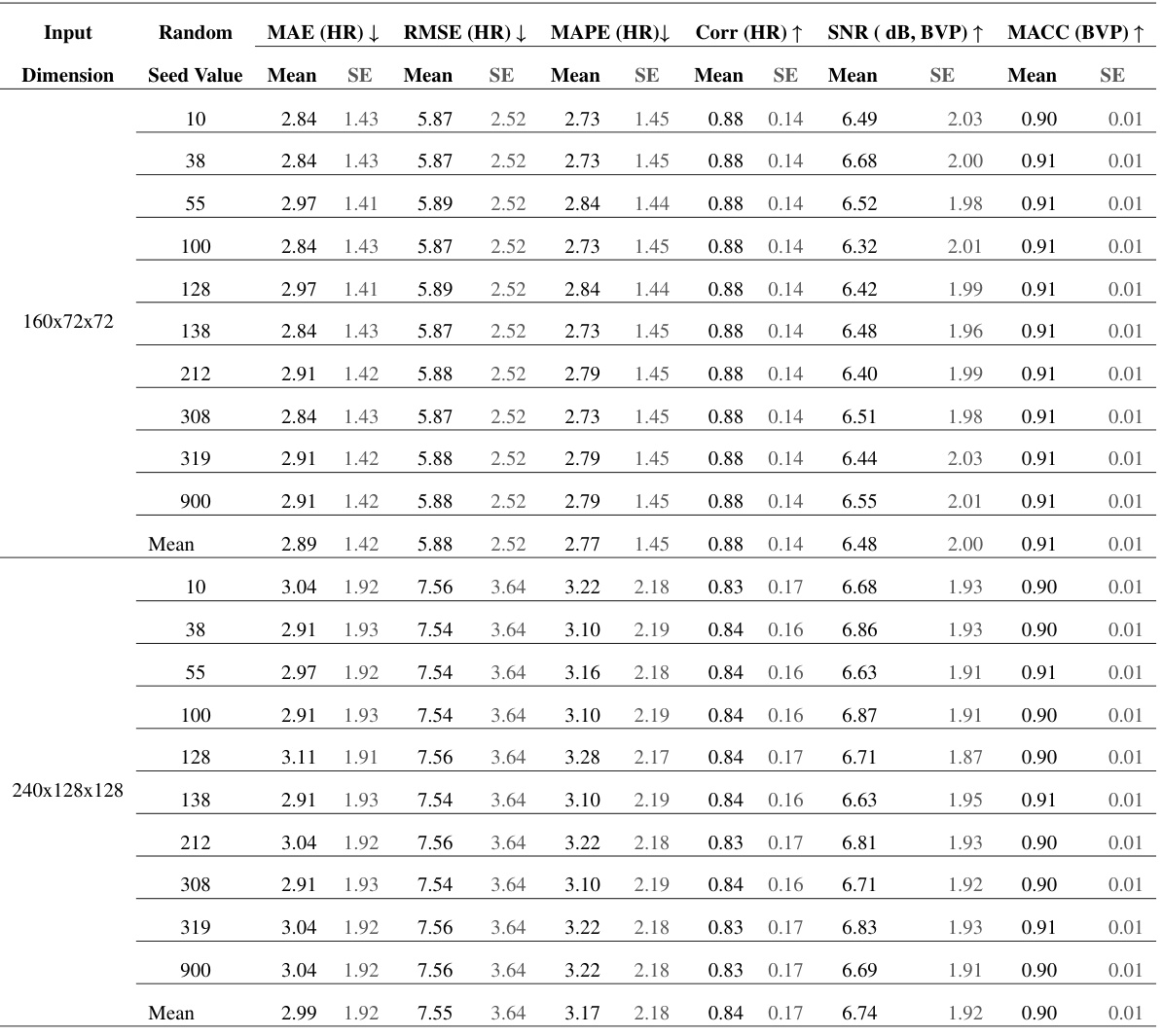

🔼 This table presents the results of a performance evaluation of different models on the PURE dataset. The models were trained using the UBFC-rPPG dataset. Multiple experiments were conducted using different random seed values to assess the consistency and reliability of the model’s performance. The metrics used for evaluation include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of Heart Rate (HR), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of HR, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of HR, Correlation (Corr) of HR, Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of Blood Volume Pulse (BVP), and Maximum Amplitude of Cross-Correlation (MACC) of BVP. Standard error (SE) is also reported for each metric.

read the caption

Table 5: Performance Evaluation of Models on PURE Dataset, Trained with UBFC-rPPG Dataset, using Different Random Seed Values

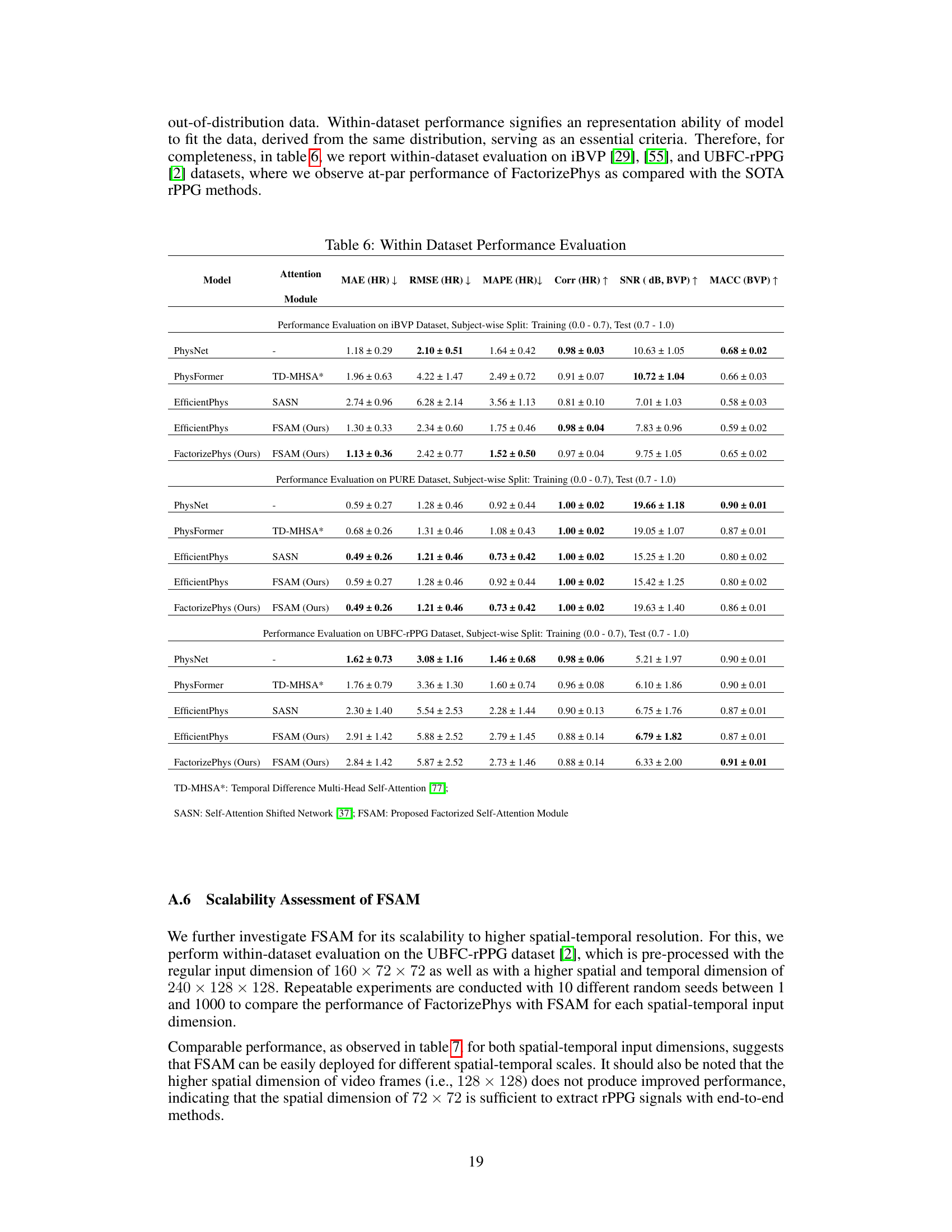

🔼 This table presents a comprehensive comparison of the proposed FactorizePhys model with state-of-the-art (SOTA) rPPG methods across four benchmark datasets (iBVP, PURE, UBFC-rPPG, and SCAMPS). For each dataset used for training, the table shows the performance of each model on the remaining three datasets as testing sets. The performance metrics include MAE (Mean Absolute Error), RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error), MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error), Corr (Correlation), SNR (Signal-to-Noise Ratio), and MACC (Maximum Amplitude of Cross-correlation) for both HR (heart rate) and BVP (blood volume pulse) signals. Standard errors are reported alongside each mean value to represent the variability of each model’s performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Cross-dataset Performance Evaluation for rPPG Estimation

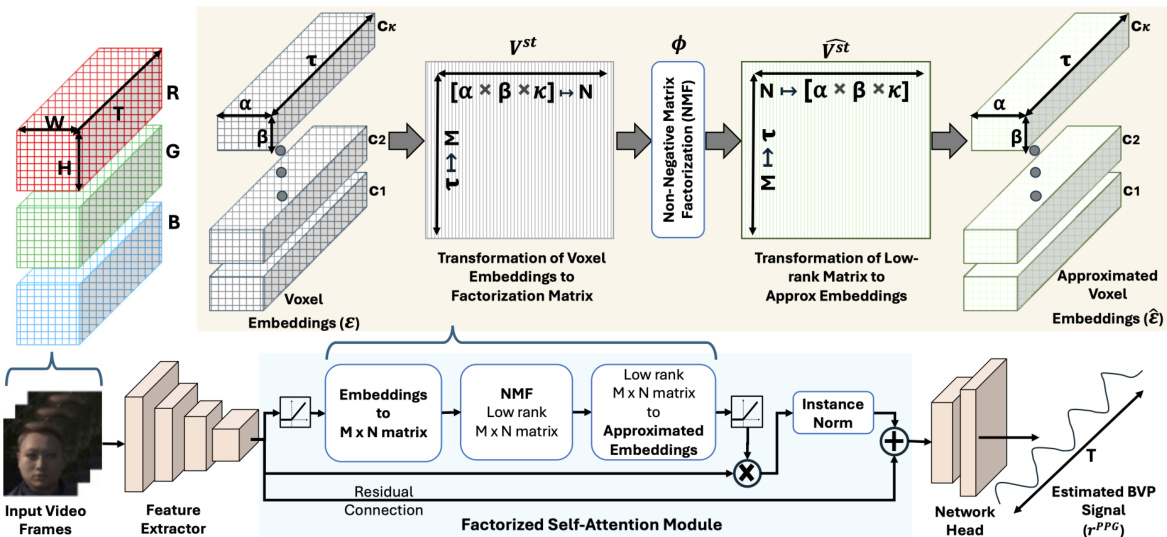

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted to evaluate the scalability of the Factorized Self-Attention Module (FSAM) to higher spatial and temporal resolutions. The experiments used two different input dimensions: 160x72x72 and 240x128x128, representing different spatial and temporal resolutions. For each input dimension, experiments were repeated with 10 different random seeds. The table shows the mean and standard error (SE) for various performance metrics (MAE, RMSE, MAPE, Corr, SNR, MACC) across the different random seeds and input dimensions. This table helps assess whether increasing spatial and temporal resolutions improves the performance or if the current resolution is already sufficient.

read the caption

Table 7: Scalability Assessment of FSAM for Higher Spatial and Temporal Dimensions

🔼 This table presents the performance of different models (PhysNet, PhysFormer, EfficientPhys with SASN, EfficientPhys with FSAM, and FactorizePhys with FSAM) on the iBVP dataset. The dataset is split into training (70%) and testing (30%) sets. The results are shown for three modalities of input frames: thermal only (T), RGB only, and RGB and thermal combined (RGBT). The metrics reported include Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for Heart Rate (HR), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for HR, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) for HR, Pearson Correlation Coefficient (Corr) for HR, Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) for Blood Volume Pulse (BVP), and Maximum Amplitude of Cross-Correlation (MACC) for BVP. Standard errors (SE) are also provided for each metric.

read the caption

Table 8: Performance Evaluation on iBVP Dataset, Subject-wise Split: Train (70%), Test (30%)

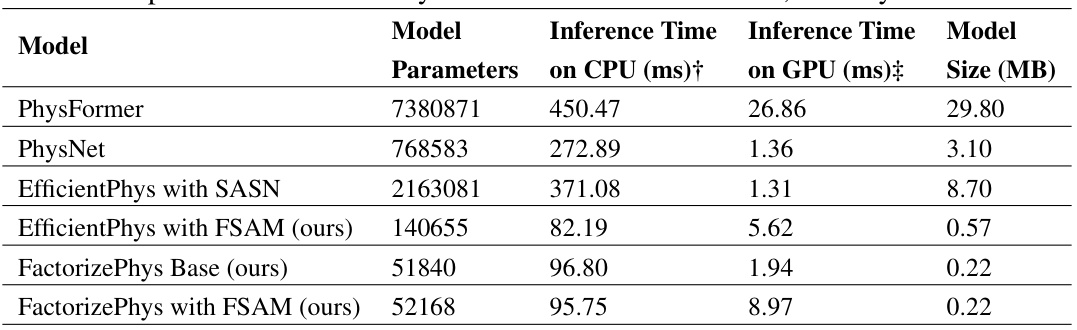

🔼 This table compares the model parameters, latency on GPU and CPU, and model size of the proposed FactorizePhys with FSAM with that of the existing SOTA rPPG methods. It highlights that FactorizePhys with FSAM uses significantly fewer parameters and achieves comparable latency on both CPU and GPU systems, despite having slightly higher latency than EfficientPhys due to the difference in FLOPS between 3D-CNN and 2D-CNN architectures. The table notes that FLOPS can be reduced by decreasing the spatial dimension of the input.

read the caption

Table 9: Comparison of FactorizePhys based on Model Parameters, Latency and Model Size

Full paper#