↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current multimodal models struggle with handling diverse modalities and tasks, often showing reduced performance compared to single-task models. This is due to challenges like negative transfer and difficulty balancing losses across various tasks. Existing models typically work with a small set of modalities, limiting their versatility.

This paper introduces 4M-21, a novel any-to-any vision model trained on 21 diverse modalities. It addresses the limitations of existing models by using a multimodal masked pre-training scheme, employing modality-specific tokenizers, and leveraging co-training on large-scale datasets. The model’s ability to handle diverse modalities without performance loss is a key contribution, surpassing the capabilities of existing models. Its open-sourced nature further accelerates research and development in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer vision and multimodal learning. It demonstrates a new approach to building any-to-any vision models, significantly advancing the field. This work opens up exciting avenues for further research, particularly in handling diverse modalities and developing more robust and efficient multitask learning models. Its open-sourced code and models also accelerate progress in this area.

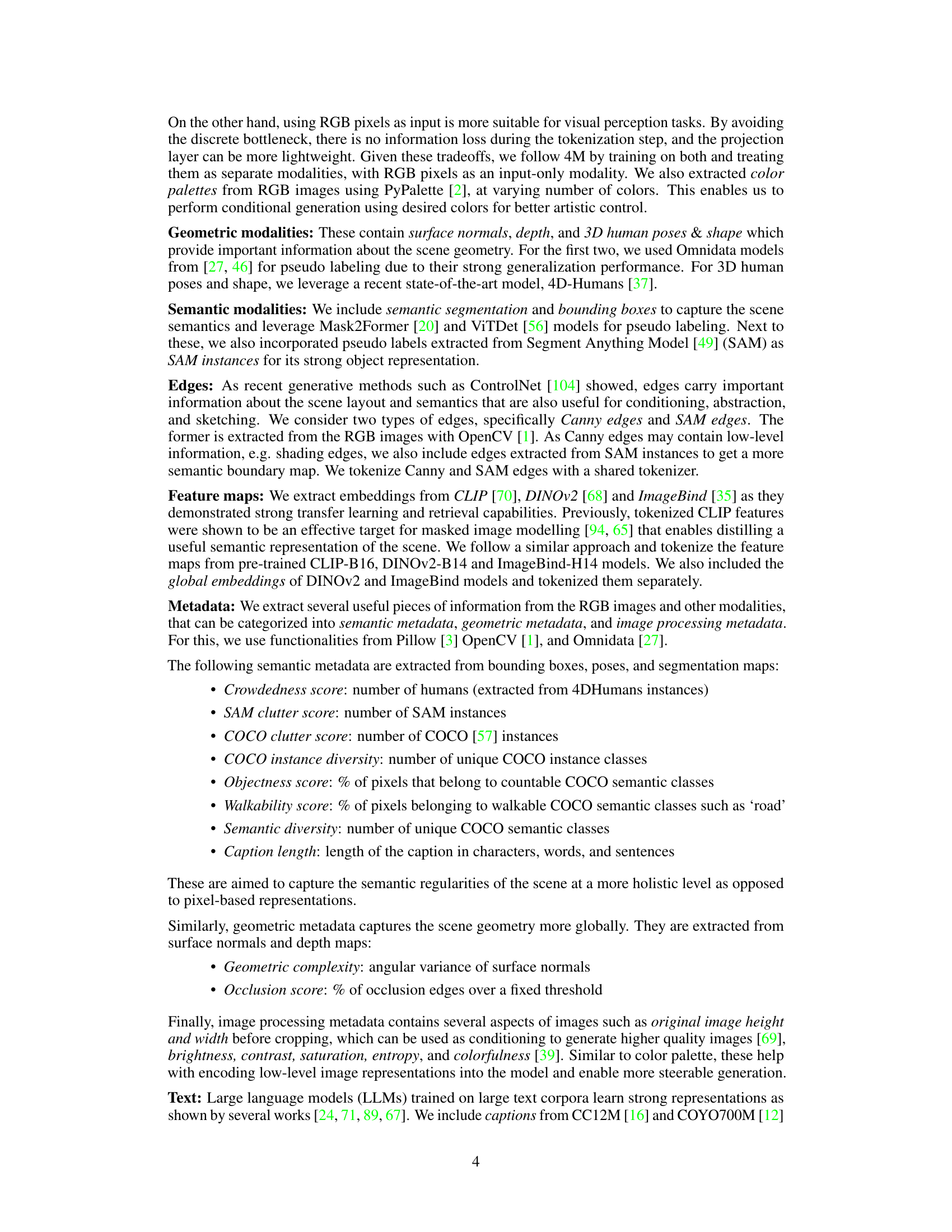

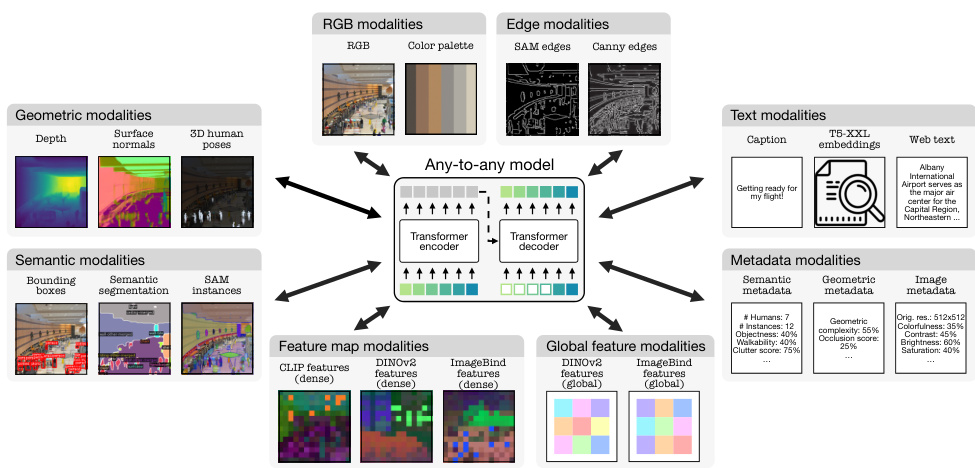

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the 4M-21 model, highlighting its ability to handle a wide variety of input modalities (images, text, depth maps, etc.) and generate corresponding outputs in any of those modalities. The model uses modality-specific tokenizers to convert the diverse inputs into a common representation that can be processed by a transformer-based encoder and decoder. This any-to-any capability is a key feature of the 4M-21 model, allowing for flexible and efficient multimodal processing.

read the caption

Figure 1: We demonstrate training a single model on tens of highly diverse modalities without a loss in performance compared to specialized single/few task models. The modalities are mapped to discrete tokens using modality-specific tokenizers. The model can generate any of the modalities from any subset of them.

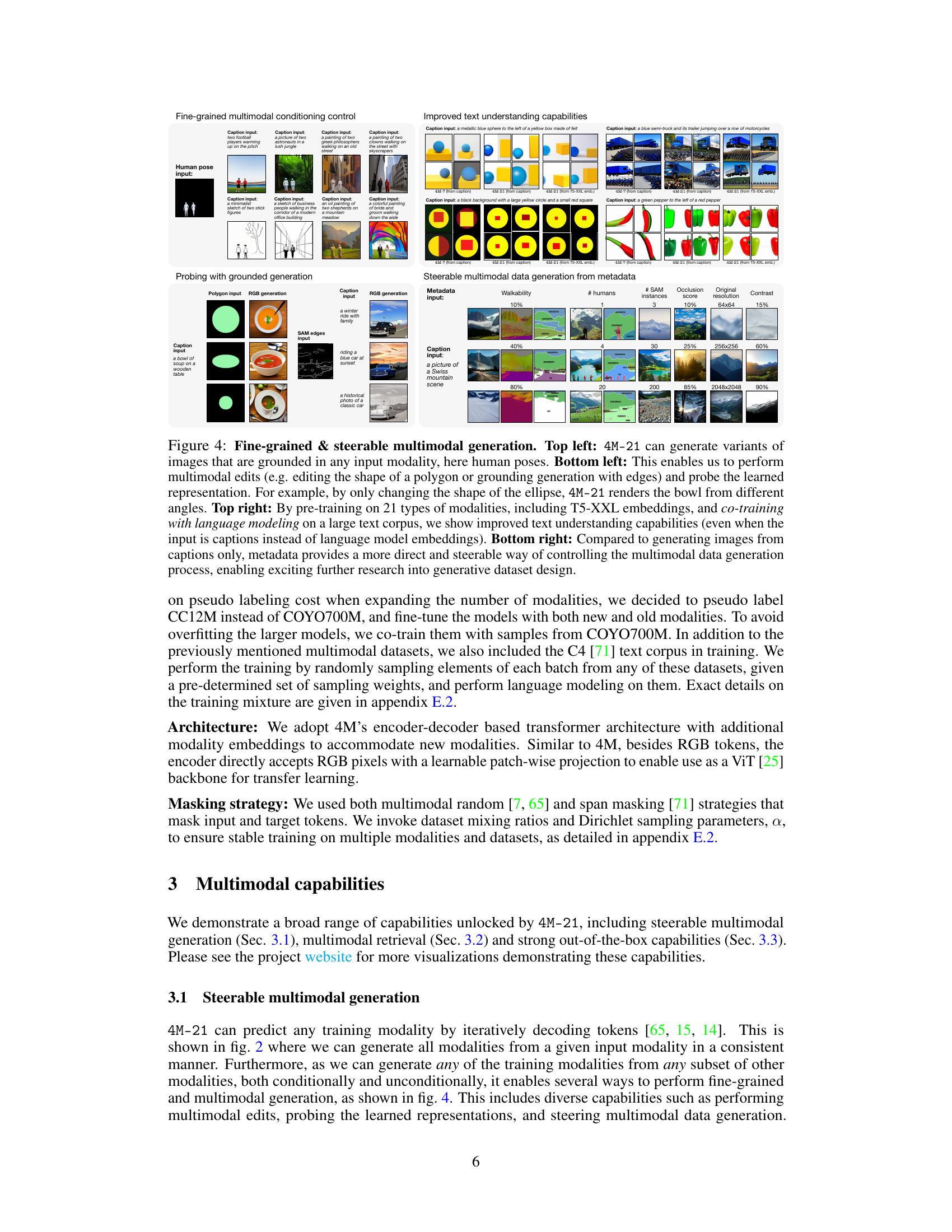

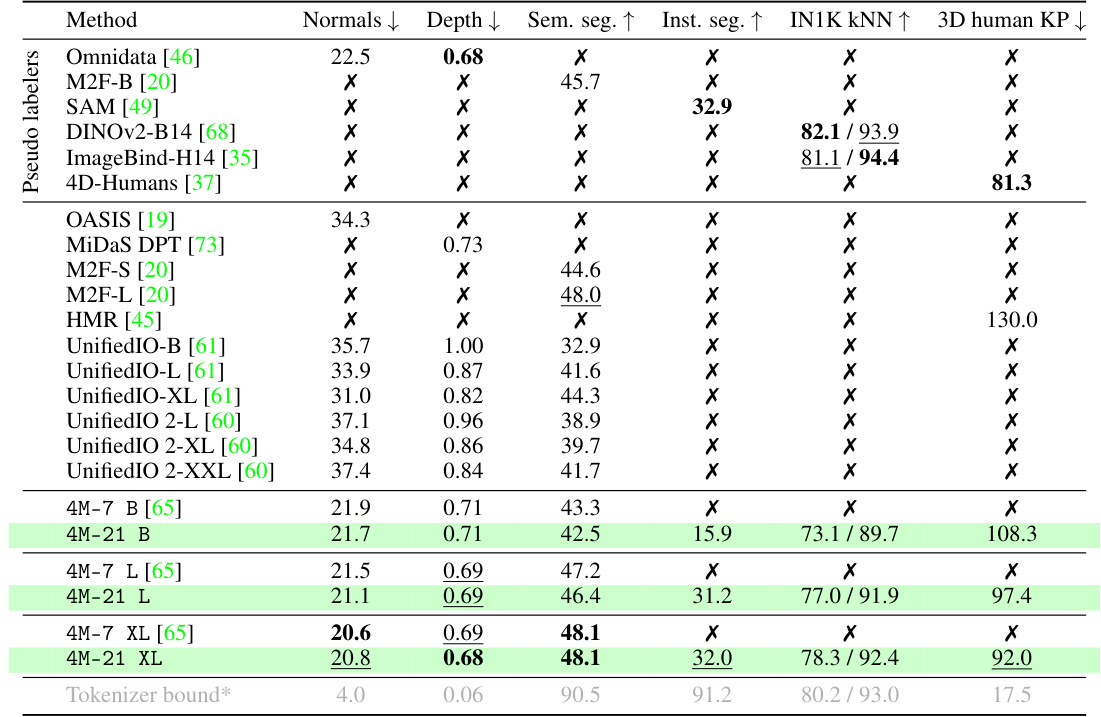

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of the 4M-21 model and several other models on four common vision tasks. The tasks are surface normal and depth estimation, semantic and instance segmentation, k-NN retrieval, and 3D human pose estimation. The comparison includes pseudo-labelers, strong baselines, and other multi-task models. The results demonstrate that 4M-21 performs competitively with, or even surpasses, specialized models on the tasks and notably maintains its performance while solving three times more tasks compared to the 4M-7 model.

read the caption

Table 1: Out-of-the-box (zero-shot) performance. We show the performance for a common subset of tasks: surface normals and depth estimation on DIODE [90], semantic and instance segmentation on COCO [57], k-NN retrieval on ImageNet-1K [79], and 3D human keypoint estimation on 3DPW [91]. We compare to a set of strong baselines and specialist models, including our pseudo labelers. The model learned to solve all the tasks without a loss of performance, is significantly better than the baselines, and is competitive with pseudo labelers, while being a single model for all tasks. Compared to 4M-7, the 4M-21 model preserved its performance while solving 3x more tasks. X denotes that a given model cannot solve the task out-of-the-box. * shows the tokenizer reconstruction quality and provides an estimate on the performance upper bound due to tokenization. See fig. 14 for qualitative comparisons. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

In-depth insights#

Any-to-Any Vision#

The concept of “Any-to-Any Vision” signifies a significant advancement in multimodal learning, aiming to build a unified model capable of handling diverse input and output modalities. This contrasts with traditional approaches that train separate models for specific tasks, resulting in reduced efficiency and scalability. A successful Any-to-Any Vision model would exhibit high flexibility allowing for seamless cross-modal interactions, such as generating an image from a text description, or retrieving relevant images based on audio input. Tokenization, the process of converting different modalities into a common representation, is crucial for enabling such a model. However, challenges remain, including handling the wide variance in data types and dimensions across modalities, and mitigating negative transfer during training. Addressing these challenges through novel training strategies and improved tokenization techniques is essential for unlocking the full potential of Any-to-Any Vision. The ultimate aim is to build more efficient, versatile, and powerful AI systems that can seamlessly integrate and interpret information from a vast range of sources.

Multimodal Tokenizers#

Multimodal tokenizers are crucial for enabling any-to-any vision models to handle diverse input modalities. The core idea is to translate different data types (images, text, depth maps, etc.) into a unified token representation, allowing a single model to process them seamlessly. Modality-specific tokenizers are employed, as different data types require distinct approaches for efficient and meaningful tokenization. For example, image data might leverage VQ-VAEs for vector quantization, while text data might use wordpiece tokenization. The choice of tokenizer is critical; it influences the model’s ability to capture relevant information and perform various tasks. Discretization of continuous data (like images) into tokens is key, facilitating tasks like iterative sampling for generation and enabling effective masked training strategies, which in turn enhance multimodal representation learning. The effectiveness of the tokenization process directly impacts overall model performance and the ability to achieve fine-grained control and cross-modal reasoning. A well-designed tokenization scheme allows for successful any-to-any prediction capabilities and efficient scalability across multiple modalities and tasks. The selection of the right tokenizer for each modality is non-trivial and requires careful consideration of the specific characteristics of the data.

Co-training Strategies#

Co-training strategies in multimodal learning aim to leverage the strengths of different modalities to improve model performance. Simultaneous training on vision and language datasets is a common approach, where the model learns to predict missing information across modalities. This approach facilitates better understanding of relationships between modalities and encourages generalization, but requires careful consideration of data alignment and loss function weighting. The success hinges on effectively integrating information from diverse data sources, demanding sophisticated techniques like multimodal masking and careful selection of datasets with strong cross-modal correlations. While computationally expensive, co-training has shown significant promise, resulting in models with superior performance compared to those trained on single modalities. Careful design of the training objective, such as a unified loss function across modalities, is crucial for preventing negative transfer and ensuring efficient learning. Future research should explore advanced techniques like curriculum learning or self-supervised pretraining to further enhance co-training effectiveness and reduce training complexity.

Multimodal Retrieval#

The section on “Multimodal Retrieval” presents a significant advance in cross-modal information access. The core idea is to leverage global feature embeddings from models like DINOv2 and ImageBind, enabling retrieval across diverse modalities. Instead of relying on single-modality queries, the approach allows for combined queries, significantly improving retrieval precision. Any modality can serve as input to retrieve any other modality, demonstrating flexibility and robustness. This capability is further enhanced by the model’s ability to combine multiple input modalities to create a more specific, constrained query. The results highlight that performance on multimodal retrieval tasks surpasses existing single-modality retrieval models, showcasing the power of the unified any-to-any model architecture.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this any-to-any vision model could significantly advance the field. Extending the model’s capabilities to even more diverse modalities, such as audio, tactile, or physiological signals, would create a truly comprehensive multisensory AI. Improving the model’s scalability is crucial; exploring techniques like efficient model architectures or distributed training would enable handling even larger datasets and more complex tasks. Developing more robust and nuanced tokenization methods is key to better handling subtle variations within modalities. Investigating the model’s emergent properties and potential for few-shot or zero-shot learning on unseen tasks and modalities warrants further investigation. This could unlock unprecedented levels of generalization in AI systems. Finally, a critical area of focus is to thoroughly investigate the ethical implications of such powerful multimodal AI, and develop strategies to mitigate potential biases and risks associated with its deployment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

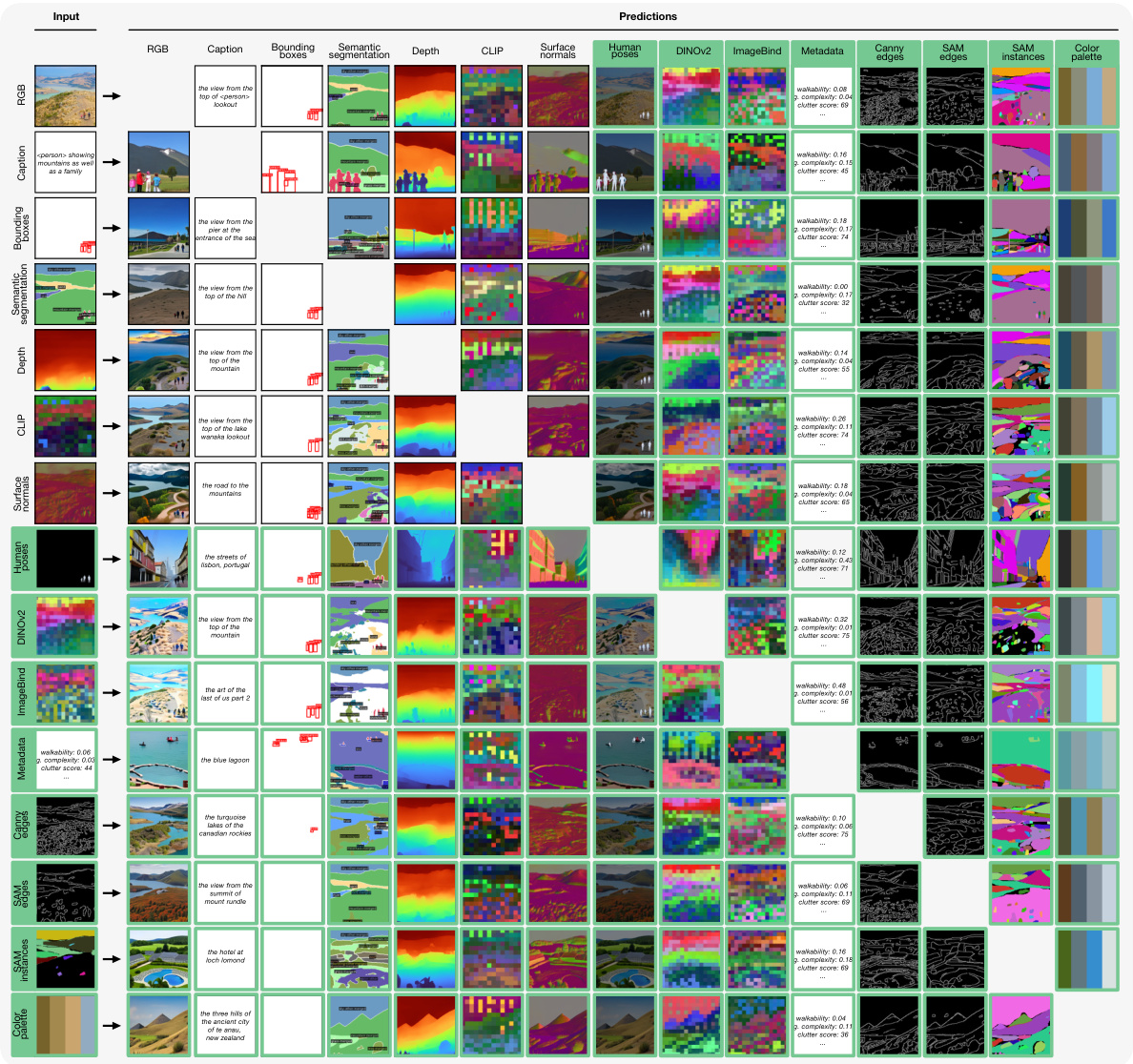

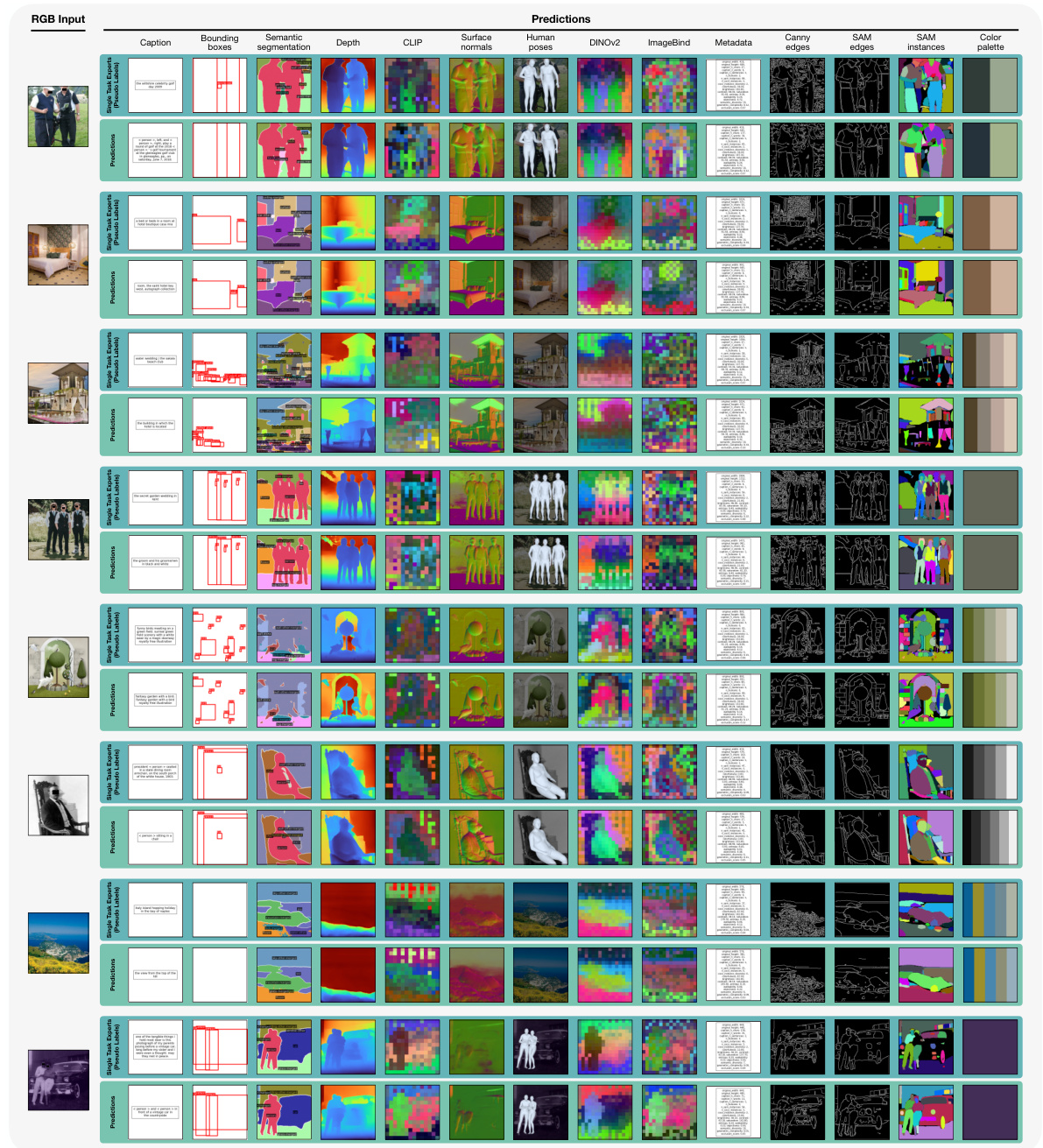

🔼 This figure demonstrates the any-to-any generation capabilities of the 4M-21 model. Starting from a single input modality (e.g., RGB image, depth map, caption), the model can generate all other modalities. The consistency across predictions for different modalities from the same scene highlights the model’s robustness and coherence. New capabilities beyond the previous 4M model are highlighted in green.

read the caption

Figure 2: One-to-all generation. 4M-21 can generate all modalities from any given input modality and can benefit from chained generation [65]. Notice the high consistency among the predictions of all modalities for one input. Each row starts from a different modality coming from the same scene. Highlighted in green are new input/output pairs that 4M [65] cannot predict nor accept as input. Note that, while this figure shows predictions from a single input, 4M-21 can generate any modality from any subset of all modalities.

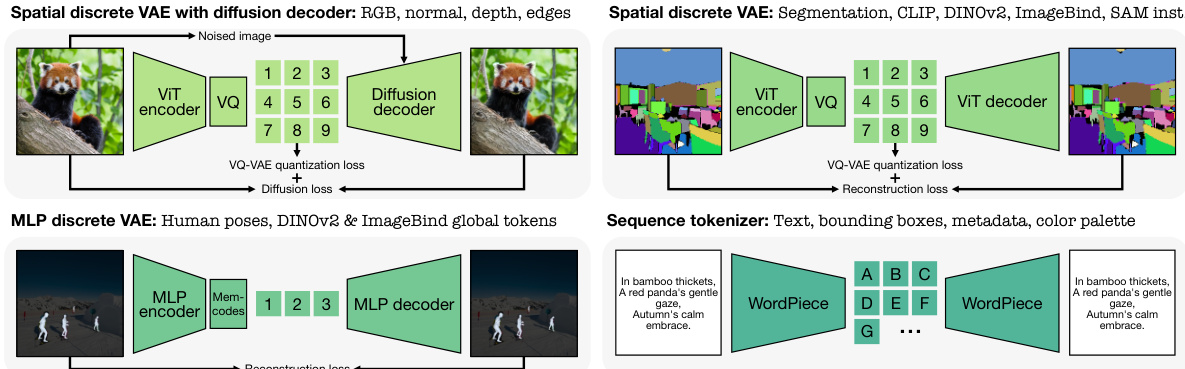

🔼 This figure illustrates the different tokenization methods used for various modalities in the 4M-21 model. Image-like data is tokenized using spatial VQ-VAEs, with diffusion decoders optionally used for high-detail modalities. Non-spatial data is tokenized using MLPs and Memcodes, while sequence data is handled with WordPiece tokenization. The low reconstruction error highlights the effectiveness of these methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Tokenization overview. We employ suitable tokenization schemes for different modalities based on their format and performance. For image-like modalities and feature maps, we use spatial VQ-VAEs [66] with optional diffusion decoders for detail rich modalities like RGB. For non-spatial modalities like global tokens or parameterized poses, we compress them to a fixed number of discrete tokens using Memcodes [62] with MLP encoders and decoders. All sequence modalities are encoded as text using WordPiece [24]. The shown examples are real tokenizer reconstructions. Notice the low reconstruction error. See appendix D for more details and Fig. 13 for visualizations.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the any-to-all generation capability of the 4M-21 model. It shows that the model can generate all 21 modalities starting from any single input modality. The consistency of the results across modalities, even when chaining generation (using an output modality as input for subsequent generation), is highlighted. New capabilities of 4M-21 compared to the previous 4M model are shown in green. The figure emphasizes that, while only one example input is shown per row, the model’s capability extends to generating any modality from any combination of input modalities.

read the caption

Figure 2: One-to-all generation. 4M-21 can generate all modalities from any given input modality and can benefit from chained generation [65]. Notice the high consistency among the predictions of all modalities for one input. Each row starts from a different modality coming from the same scene. Highlighted in green are new input/output pairs that 4M [65] cannot predict nor accept as input. Note that, while this figure shows predictions from a single input, 4M-21 can generate any modality from any subset of all modalities.

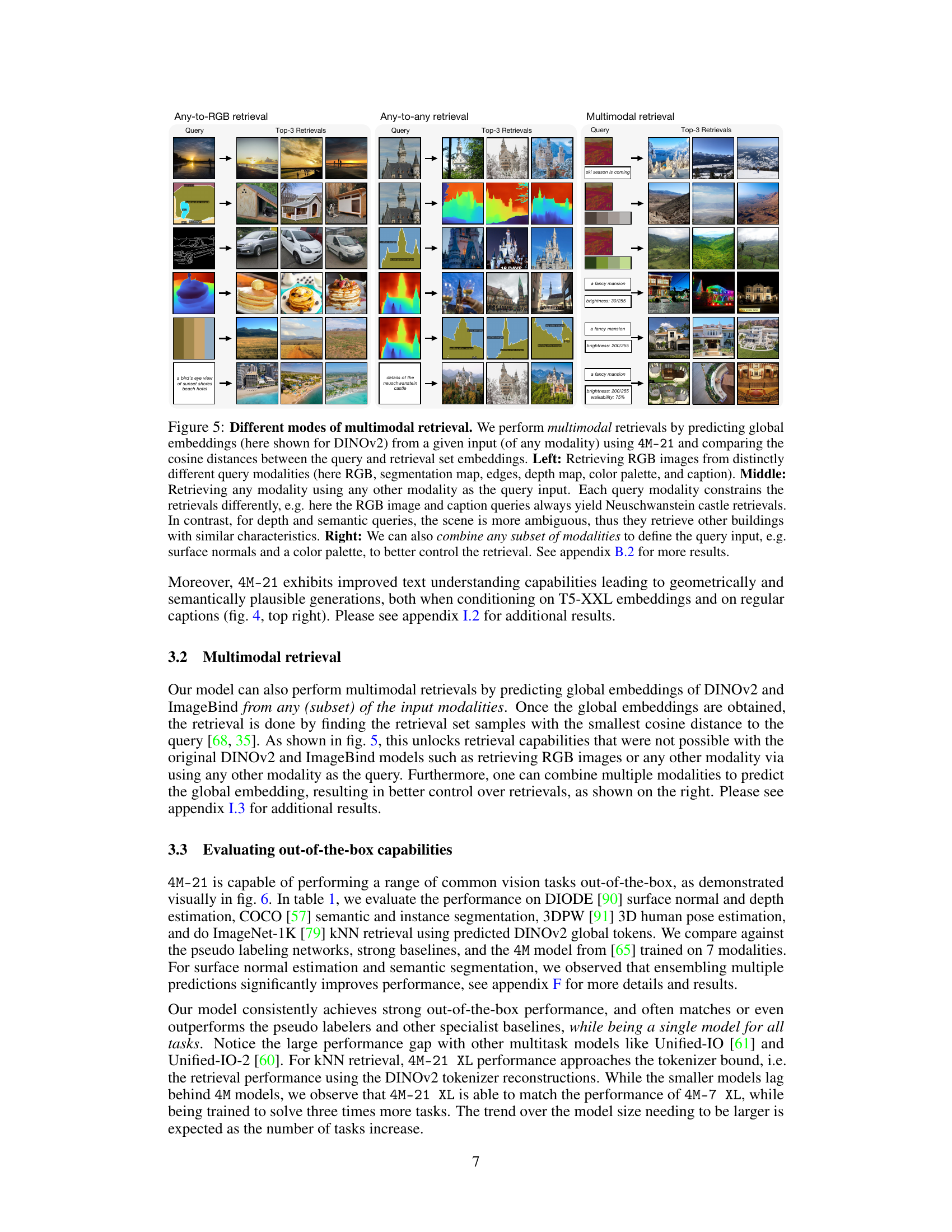

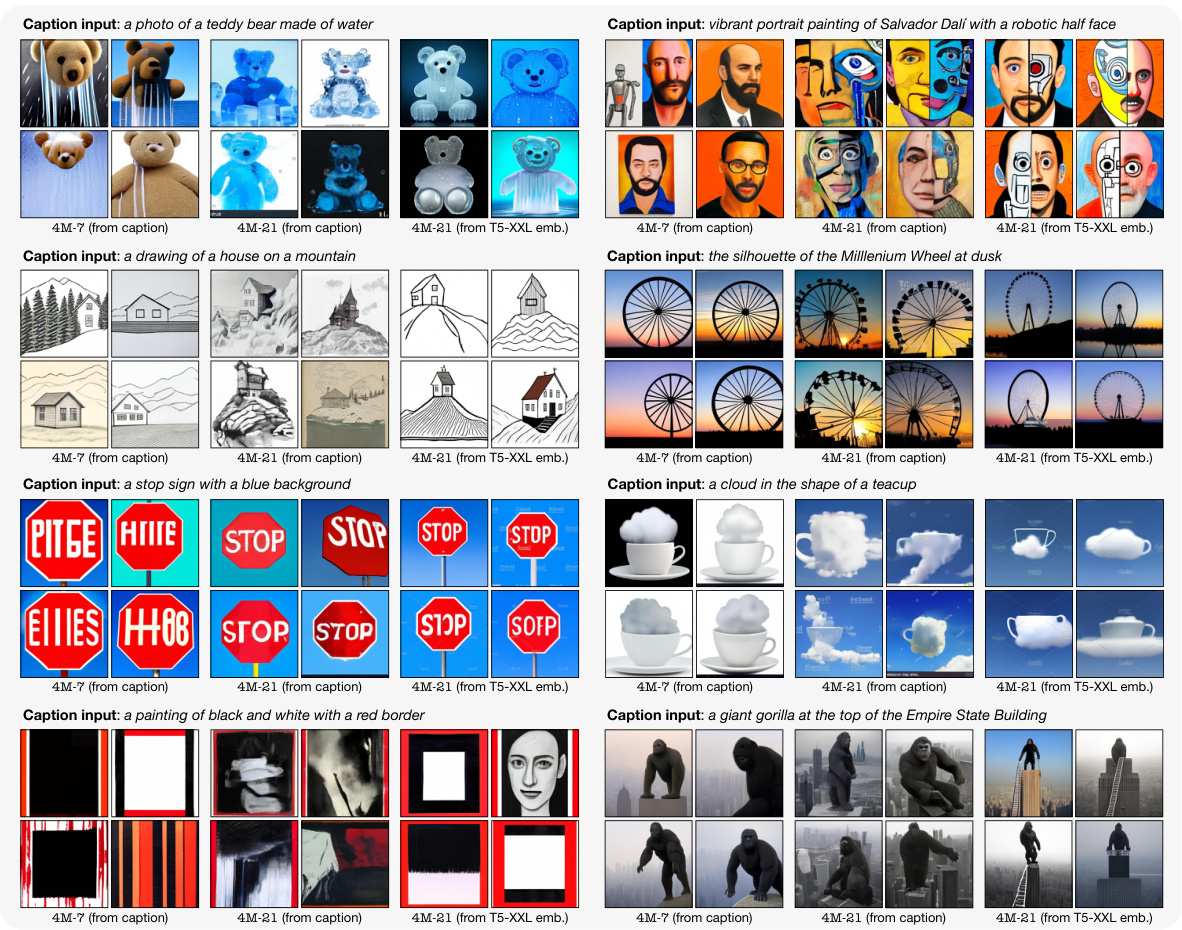

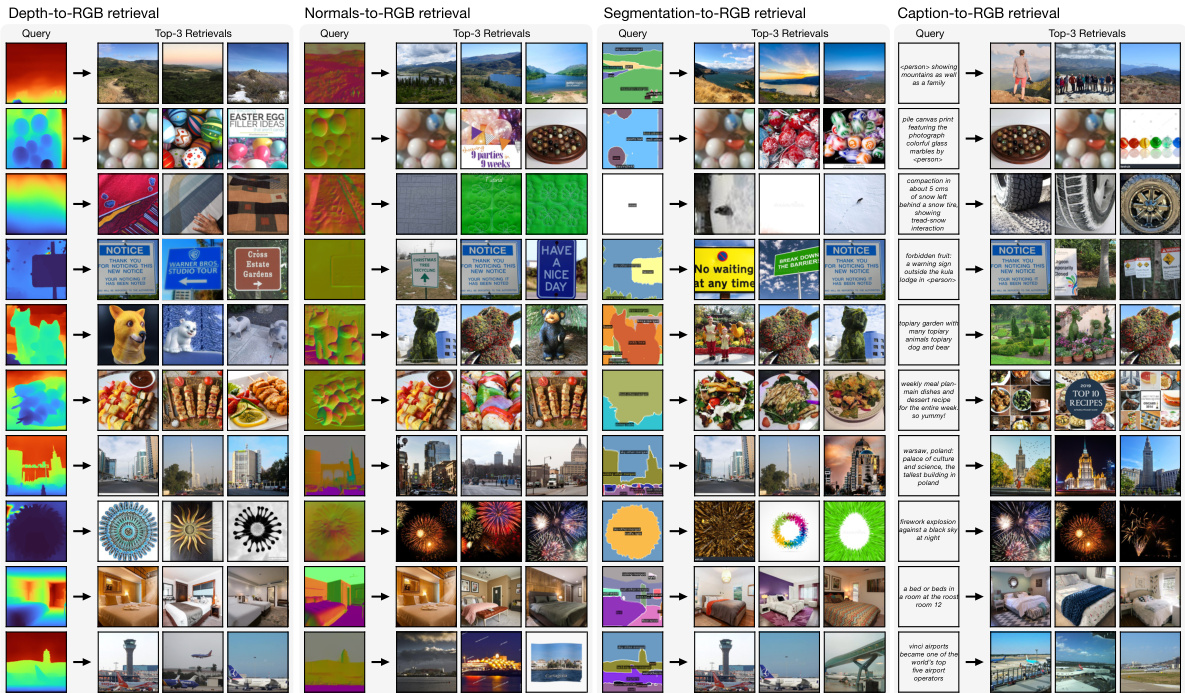

🔼 This figure demonstrates the multimodal retrieval capabilities of the 4M-21 model. It shows three scenarios: retrieving RGB images from various input modalities (left), retrieving any modality from any other modality (middle), and retrieving using a combination of modalities (right). The results highlight the model’s ability to perform cross-modal retrieval effectively and control the retrieval process through input modality selection.

read the caption

Figure 5: Different modes of multimodal retrieval. We perform multimodal retrievals by predicting global embeddings (here shown for DINOv2) from a given input (of any modality) using 4M-21 and comparing the cosine distances between the query and retrieval set embeddings. Left: Retrieving RGB images from distinctly different query modalities (here RGB, segmentation map, edges, depth map, color palette, and caption). Middle: Retrieving any modality using any other modality as the query input. Each query modality constrains the retrievals differently, e.g. here the RGB image and caption queries always yield Neuschwanstein castle retrievals. In contrast, for depth and semantic queries, the scene is more ambiguous, thus they retrieve other buildings with similar characteristics. Right: We can also combine any subset of modalities to define the query input, e.g. surface normals and a color palette, to better control the retrieval. See appendix B.2 for more results.

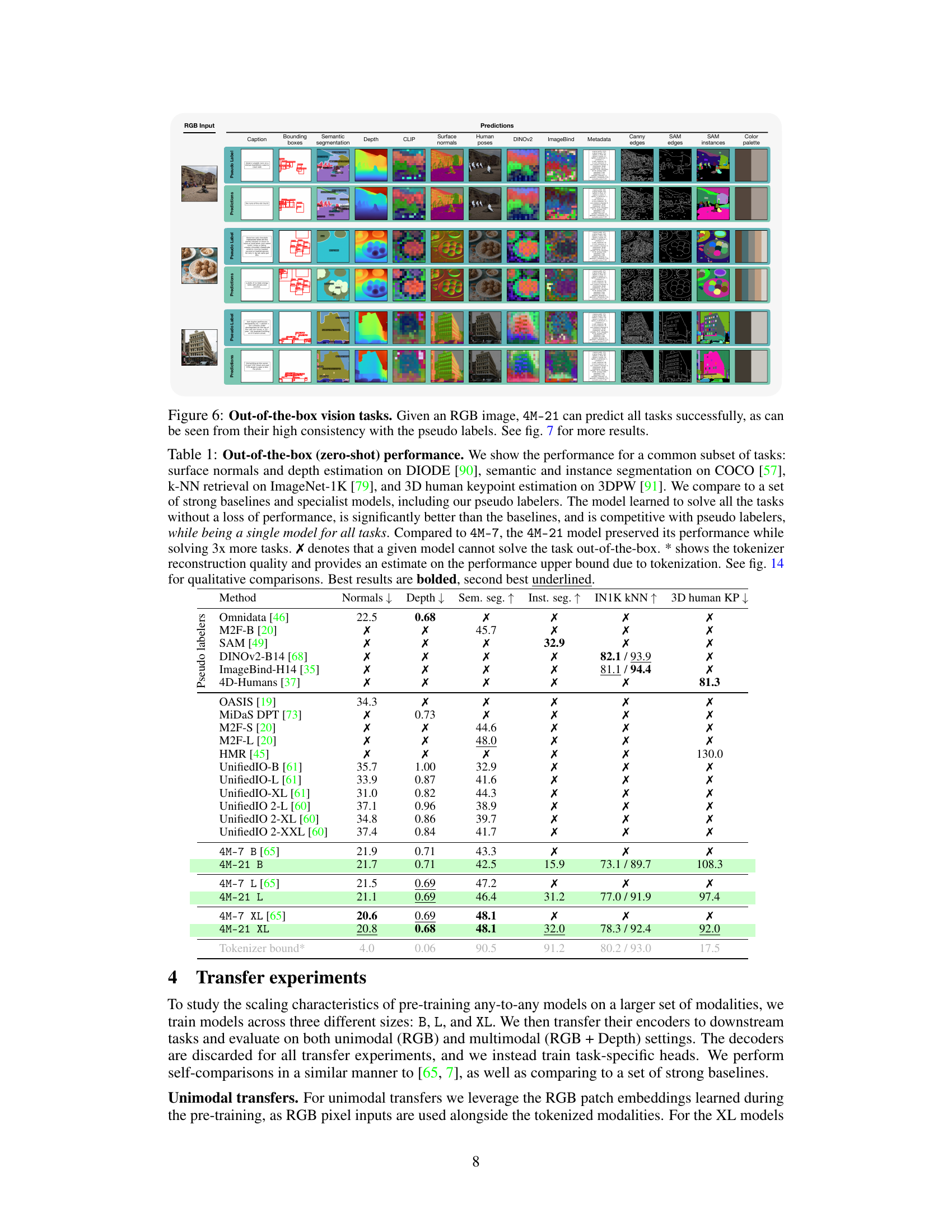

🔼 This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to perform several vision tasks (caption, bounding boxes, semantic segmentation, depth, CLIP, surface normals, human poses, DINOV2, ImageBind, metadata, Canny edges, SAM edges, SAM instances, and color palette) given only an RGB image as input. The predictions are compared against pseudo labels (predictions from specialist models), showcasing the model’s strong zero-shot capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 6: Out-of-the-box vision tasks. Given an RGB image, 4M-21 can predict all tasks successfully, as can be seen from their high consistency with the pseudo labels. See fig. 7 for more results.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to perform various vision tasks (surface normals, depth estimation, semantic segmentation, instance segmentation, keypoints detection, and caption generation) directly from an RGB image input. The high consistency between the model’s predictions and the pseudo labels from task-specific experts suggests the model’s strong performance on these tasks, even without any specific task training. Additional results illustrating more tasks are shown in Figure 7.

read the caption

Figure 6: Out-of-the-box vision tasks. Given an RGB image, 4M-21 can predict all tasks successfully, as can be seen from their high consistency with the pseudo labels. See fig. 7 for more results.

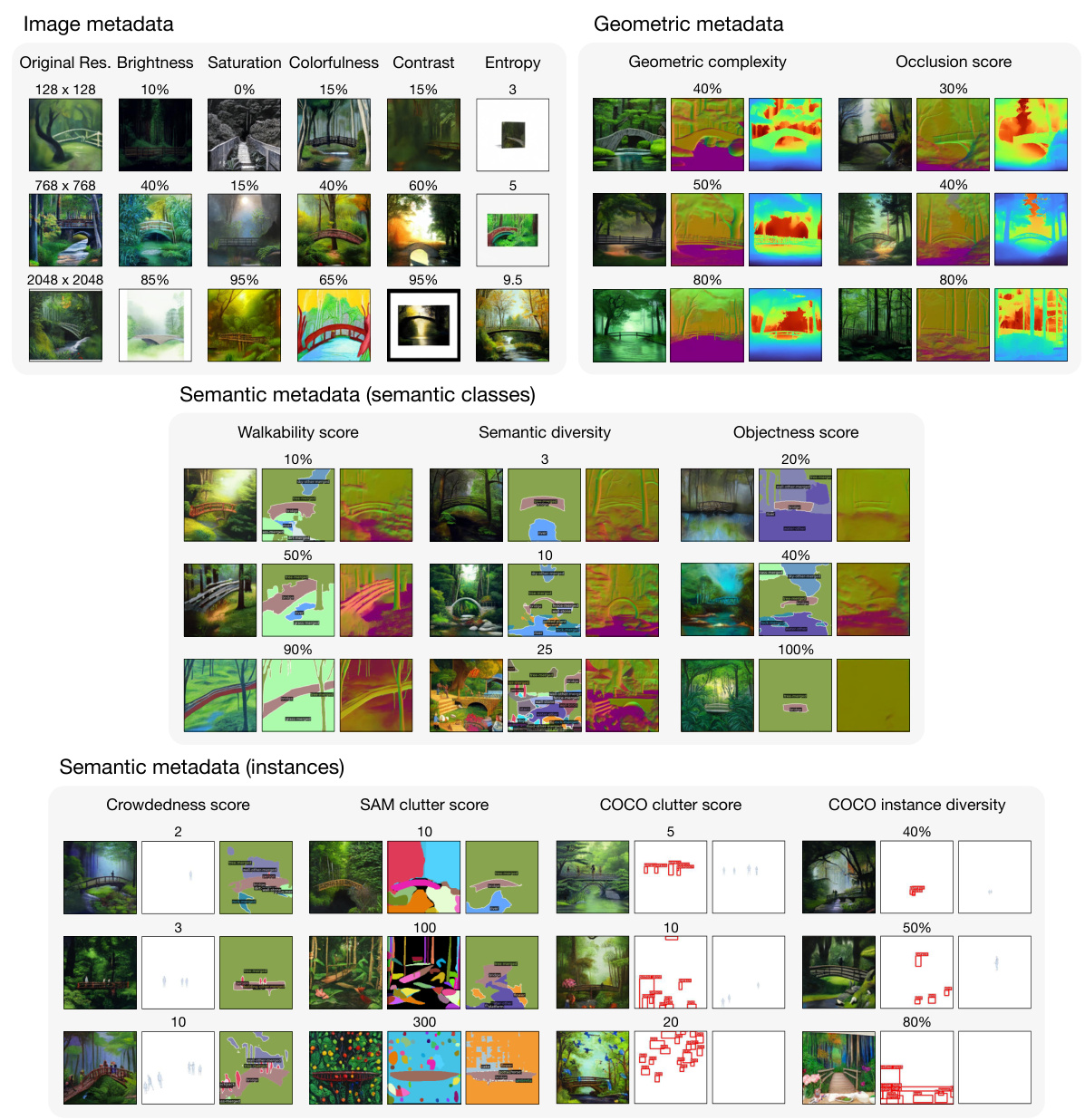

🔼 This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generate diverse modalities using metadata as control inputs. It shows how various image attributes (brightness, saturation, colorfulness, etc.), geometric properties (complexity, occlusion), and semantic information (walkability, diversity, objectness, instance counts, etc.) can be used to steer the generation process, resulting in different outputs for the same caption. This showcases fine-grained control over multimodal generation beyond simple text prompts.

read the caption

Figure 8: Steerable multimodal generation using metadata. This is an extension of fig. 4 and shows our model's capability of generating multimodal data by conditioning on a wide set of controls. The common caption for all examples is 'a painting of a bridge in a lush forest'.

🔼 This figure shows the model’s ability to generate images conditioned on various inputs. The top half demonstrates the effect of changing the shape of SAM instances while keeping the caption and color palette consistent. The bottom half shows how changing the color palette impacts the generated image while keeping the caption and normal map consistent.

read the caption

Figure 9: Probing with grounded generation. This is an extension of fig. 4 and further shows our model's capability on performing generation by conditioning on multimodal input. The top row varies SAM instances and combines them with a fixed caption and color palette input. The bottom row fixes the normals and caption inputs and varies the color palette.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generate images based on different combinations of input modalities. The top half shows how varying SAM (Segment Anything Model) instances impacts the generated image while keeping the caption and color palette constant. The bottom half shows the effect of varying color palettes while keeping the caption and normals constant. This highlights the model’s fine-grained control over image generation through multimodal conditioning.

read the caption

Figure 9: Probing with grounded generation. This is an extension of fig. 4 and further shows our model's capability on performing generation by conditioning on multimodal input. The top row varies SAM instances and combines them with a fixed caption and color palette input. The bottom row fixes the normals and caption inputs and varies the color palette.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the any-to-any generation capability of the 4M-21 model. Starting with a single input modality (e.g., RGB image, depth map, caption), the model generates all other modalities in a consistent manner. The high consistency highlights the model’s ability to understand the underlying scene regardless of the input modality. Green highlights show new modality pairs that previous models like 4M couldn’t handle.

read the caption

Figure 2: One-to-all generation. 4M-21 can generate all modalities from any given input modality and can benefit from chained generation [65]. Notice the high consistency among the predictions of all modalities for one input. Each row starts from a different modality coming from the same scene. Highlighted in green are new input/output pairs that 4M [65] cannot predict nor accept as input. Note that, while this figure shows predictions from a single input, 4M-21 can generate any modality from any subset of all modalities.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the multimodal retrieval capabilities of the 4M-21 model. It shows three different retrieval scenarios: retrieving RGB images from various input modalities, retrieving any modality from any other modality, and combining multiple input modalities to refine retrieval results. Each scenario highlights how different input modalities influence the retrieval process, showcasing the model’s ability to handle diverse input types and perform cross-modal retrieval effectively.

read the caption

Figure 5: Different modes of multimodal retrieval. We perform multimodal retrievals by predicting global embeddings (here shown for DINOv2) from a given input (of any modality) using 4M-21 and comparing the cosine distances between the query and retrieval set embeddings. Left: Retrieving RGB images from distinctly different query modalities (here RGB, segmentation map, edges, depth map, color palette, and caption). Middle: Retrieving any modality using any other modality as the query input. Each query modality constrains the retrievals differently, e.g. here the RGB image and caption queries always yield Neuschwanstein castle retrievals. In contrast, for depth and semantic queries, the scene is more ambiguous, thus they retrieve other buildings with similar characteristics. Right: We can also combine any subset of modalities to define the query input, e.g. surface normals and a color palette, to better control the retrieval. See appendix B.2 for more results.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the multimodal retrieval capabilities of the 4M-21 model. It shows three different retrieval scenarios: 1. Any-to-RGB: Retrieving RGB images using various input modalities (RGB image, segmentation, edges, depth, normals, caption). The results highlight that different input modalities lead to varying retrieval results. 2. Any-to-Any: Retrieving any modality using any other modality as input, demonstrating the model’s flexibility to handle different input-output modality pairs. 3. Multimodal Retrieval: Combining multiple modalities to define the query input, which results in more focused and controlled retrieval.

read the caption

Figure 5: Different modes of multimodal retrieval. We perform multimodal retrievals by predicting global embeddings (here shown for DINOv2) from a given input (of any modality) using 4M-21 and comparing the cosine distances between the query and retrieval set embeddings. Left: Retrieving RGB images from distinctly different query modalities (here RGB, segmentation map, edges, depth map, color palette, and caption). Middle: Retrieving any modality using any other modality as the query input. Each query modality constrains the retrievals differently, e.g. here the RGB image and caption queries always yield Neuschwanstein castle retrievals. In contrast, for depth and semantic queries, the scene is more ambiguous, thus they retrieve other buildings with similar characteristics. Right: We can also combine any subset of modalities to define the query input, e.g. surface normals and a color palette, to better control the retrieval. See appendix B.2 for more results.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the quality of the tokenization process for various input modalities. It shows several examples of input modalities (RGB, Depth, Surface Normals, Semantic Segmentation, SAM Instances, and Canny Edges) and their corresponding reconstruction after applying the modality-specific tokenizers. The results demonstrate that the tokenizers effectively capture the essential information of the input modalities, highlighting their capacity to convert diverse data into discrete tokens for the model’s processing.

read the caption

Figure 13: Tokenizer reconstruction quality. Our multimodal tokenizers can reconstruct the ground truth well. Here we show sample reconstructions of RGB, depth, surface normals, semantic segmentation, SAM instances, and canny edges on (pseudo) labels from the CC12M validation set at 224 × 224 resolution. Quantitative evaluations are provided in table 1 for different tasks and datasets (last row, Tokenizer bound), confirming the reconstruction quality.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the any-to-any generation capability of the 4M-21 model. It shows that the model can generate any of the 21 modalities from a single input modality, and that this generation remains consistent across multiple modalities. Highlighed in green are results that the previous 4M model could not generate. The figure highlights the model’s ability to chain generations, using the output of one modality prediction as the input for another.

read the caption

Figure 2: One-to-all generation. 4M-21 can generate all modalities from any given input modality and can benefit from chained generation [65]. Notice the high consistency among the predictions of all modalities for one input. Each row starts from a different modality coming from the same scene. Highlighted in green are new input/output pairs that 4M [65] cannot predict nor accept as input. Note that, while this figure shows predictions from a single input, 4M-21 can generate any modality from any subset of all modalities.

🔼 This figure showcases the reconstruction quality of different modality tokenizers used in the 4M-21 model. It shows examples of reconstructed images and other modalities (depth, surface normals, semantic segmentations, SAM instances, and Canny edges) compared to their ground truth versions. The quality is generally high, demonstrating effective tokenization.

read the caption

Figure 13: Tokenizer reconstruction quality. Our multimodal tokenizers can reconstruct the ground truth well. Here we show sample reconstructions of RGB, depth, surface normals, semantic segmentation, SAM instances, and canny edges on (pseudo) labels from the CC12M validation set at 224 × 224 resolution. Quantitative evaluations are provided in table 1 for different tasks and datasets (last row, Tokenizer bound), confirming the reconstruction quality.

🔼 This figure shows the reconstruction quality of different tokenizers used in the 4M-21 model. It provides visual examples of how well the tokenizers reconstruct various modalities (RGB images, depth maps, surface normals, semantic segmentations, SAM instances, and Canny edges) from their corresponding token representations. The results demonstrate that the tokenizers effectively capture the essential information of each modality.

read the caption

Figure 13: Tokenizer reconstruction quality. Our multimodal tokenizers can reconstruct the ground truth well. Here we show sample reconstructions of RGB, depth, surface normals, semantic segmentation, SAM instances, and canny edges on (pseudo) labels from the CC12M validation set at 224 × 224 resolution. Quantitative evaluations are provided in table 1 for different tasks and datasets (last row, Tokenizer bound), confirming the reconstruction quality.

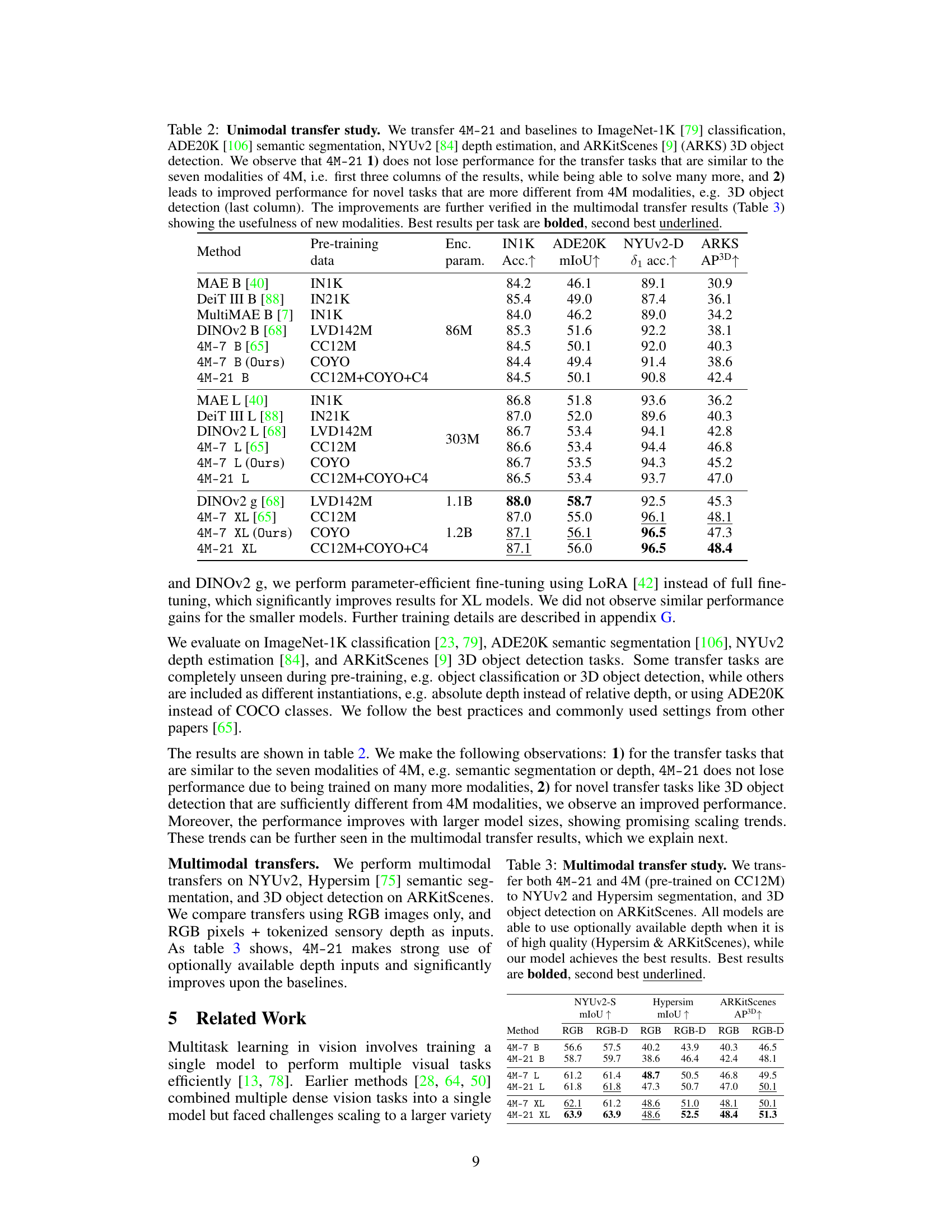

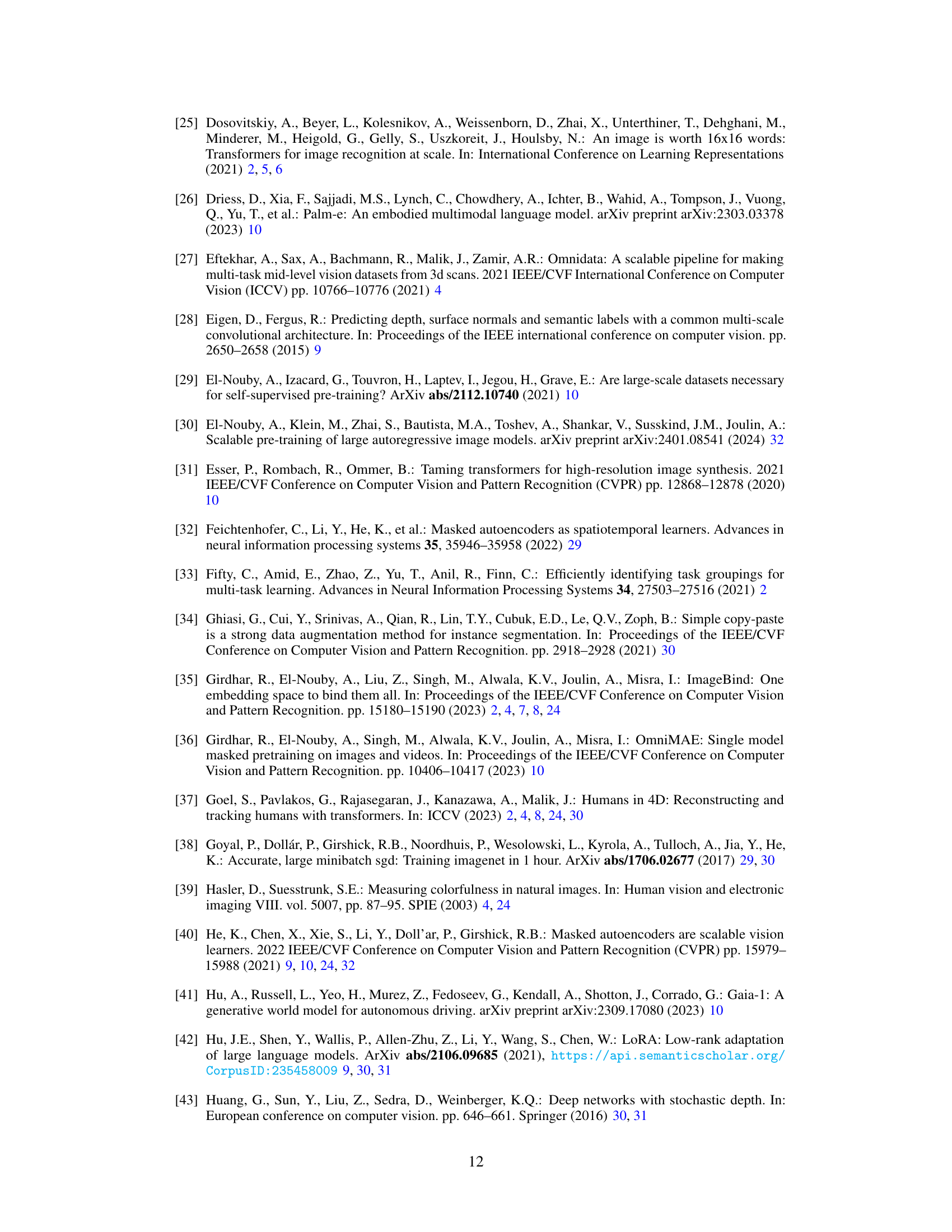

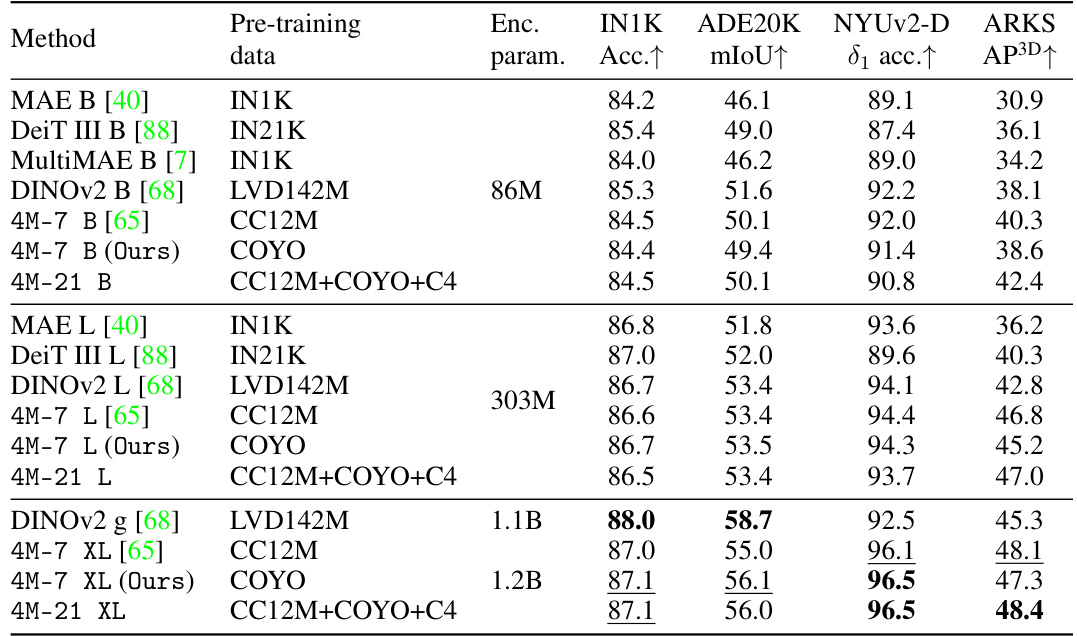

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of a unimodal transfer learning experiment. The authors transferred the encoders of various models (including their proposed 4M-21 model and several baselines) to four downstream tasks: ImageNet-1K classification, ADE20K semantic segmentation, NYUv2 depth estimation, and ARKitScenes 3D object detection. The table shows that 4M-21 maintains performance on tasks similar to those in its pre-training while improving on novel tasks, highlighting the benefits of training on a wider range of modalities. The table includes pre-training data, encoder parameters, and performance metrics for each task.

read the caption

Table 2: Unimodal transfer study. We transfer 4M-21 and baselines to ImageNet-1K [79] classification, ADE20K [106] semantic segmentation, NYUv2 [84] depth estimation, and ARKitScenes [9] (ARKS) 3D object detection. We observe that 4M-21 1) does not lose performance for the transfer tasks that are similar to the seven modalities of 4M, i.e. first three columns of the results, while being able to solve many more, and 2) leads to improved performance for novel tasks that are more different from 4M modalities, e.g. 3D object detection (last column). The improvements are further verified in the multimodal transfer results (Table 3) showing the usefulness of new modalities. Best results per task are bolded, second best underlined.

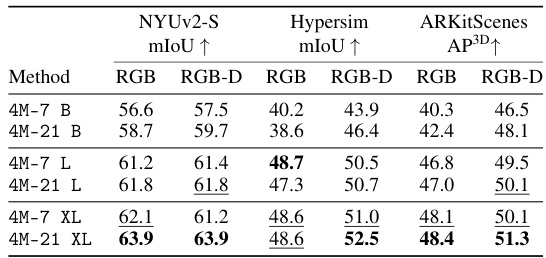

🔼 This table compares the performance of 4M-21 and 4M models on three multimodal transfer tasks: NYUv2 semantic segmentation, Hypersim semantic segmentation, and ARKitScenes 3D object detection. The results show how the models perform using only RGB images as input, and how performance changes when depth information is also available. 4M-21 consistently outperforms 4M across all tasks and model sizes. The use of depth data is shown to improve results for the Hypersim and ARKitScenes tasks.

read the caption

Table 3: Multimodal transfer study. We transfer both 4M-21 and 4M (pre-trained on CC12M) to NYUv2 and Hypersim segmentation, and 3D object detection on ARKitScenes. All models are able to use optionally available depth when it is of high quality (Hypersim & ARKitScenes), while our model achieves the best results. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

🔼 This table presents ablation studies on different pre-training data and modality combinations for the 4M-21 model (size B). It compares the performance of models trained with various combinations of CC12M, COYO700M, and C4 datasets, highlighting the impact of dataset diversity and modality mix on downstream transfer tasks.

read the caption

Table 4: Pre-training data and modality mixture ablation: We ablate different pre-training modality and dataset choices on B models. * represents the models initialized from the corresponding 4M models trained on COYO700M.

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on ensembling multiple predictions for improving the performance. The results demonstrate that ensembling multiple predictions for surface normal estimation on DIODE and semantic segmentation on COCO datasets improves the quantitative results (mean angle error and mean IoU).

read the caption

Table 5: Ensembling ablation: We ablate ensembling multiple predictions on DIODE normals and COCO semantic segmentation compared to no ensembling. As the results suggest, ensembling in all cases improves the quantitative results.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the 4M-21 model’s zero-shot performance on several common vision tasks against various strong baselines and specialist models. It highlights the model’s ability to perform well on multiple tasks simultaneously without performance degradation, outperforming baselines and matching the performance of specialized models. The results are compared using standard metrics for each task and consider tokenizer limitations.

read the caption

Table 1: Out-of-the-box (zero-shot) performance. We show the performance for a common subset of tasks: surface normals and depth estimation on DIODE [90], semantic and instance segmentation on COCO [57], k-NN retrieval on ImageNet-1K [79], and 3D human keypoint estimation on 3DPW [91]. We compare to a set of strong baselines and specialist models, including our pseudo labelers. The model learned to solve all the tasks without a loss of performance, is significantly better than the baselines, and is competitive with pseudo labelers, while being a single model for all tasks. Compared to 4M-7, the 4M-21 model preserved its performance while solving 3x more tasks. X denotes that a given model cannot solve the task out-of-the-box. * shows the tokenizer reconstruction quality and provides an estimate on the performance upper bound due to tokenization. See fig. 14 for qualitative comparisons. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of 4M-21 and several other models on four different vision tasks. The tasks are surface normal estimation, depth estimation, semantic segmentation, and 3D human keypoint estimation. The table shows that 4M-21 achieves comparable or better results than specialized models for each task, demonstrating its strong zero-shot capabilities. The table also includes the performance of pseudo-labelers, which are used to train the models, and several multi-task baselines.

read the caption

Table 1: Out-of-the-box (zero-shot) performance. We show the performance for a common subset of tasks: surface normals and depth estimation on DIODE [90], semantic and instance segmentation on COCO [57], k-NN retrieval on ImageNet-1K [79], and 3D human keypoint estimation on 3DPW [91]. We compare to a set of strong baselines and specialist models, including our pseudo labelers. The model learned to solve all the tasks without a loss of performance, is significantly better than the baselines, and is competitive with pseudo labelers, while being a single model for all tasks. Compared to 4M-7, the 4M-21 model preserved its performance while solving 3x more tasks. X denotes that a given model cannot solve the task out-of-the-box. * shows the tokenizer reconstruction quality and provides an estimate on the performance upper bound due to tokenization. See fig. 14 for qualitative comparisons. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of the 4M-21 model against several strong baselines and specialist models on four common vision tasks: surface normal and depth estimation, semantic and instance segmentation, k-NN retrieval, and 3D human keypoint estimation. The results demonstrate that 4M-21 achieves strong out-of-the-box performance, matching or exceeding specialist models while being a single model for all tasks. The table highlights the benefits of training a single, any-to-any model on a large number of modalities without any loss in performance compared to specialized single/few task models.

read the caption

Table 1: Out-of-the-box (zero-shot) performance. We show the performance for a common subset of tasks: surface normals and depth estimation on DIODE [90], semantic and instance segmentation on COCO [57], k-NN retrieval on ImageNet-1K [79], and 3D human keypoint estimation on 3DPW [91]. We compare to a set of strong baselines and specialist models, including our pseudo labelers. The model learned to solve all the tasks without a loss of performance, is significantly better than the baselines, and is competitive with pseudo labelers, while being a single model for all tasks. Compared to 4M-7, the 4M-21 model preserved its performance while solving 3x more tasks. X denotes that a given model cannot solve the task out-of-the-box. * shows the tokenizer reconstruction quality and provides an estimate on the performance upper bound due to tokenization. See fig. 14 for qualitative comparisons. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of the 4M-21 model against several strong baselines and specialized models on four common computer vision tasks. The tasks evaluated are surface normal and depth estimation, semantic and instance segmentation, k-NN retrieval, and 3D human keypoint estimation. The results demonstrate that the 4M-21 model performs competitively with or better than specialized models on all tasks, while being a single model capable of handling all of them. This showcases the model’s strong out-of-the-box capabilities, especially when compared to its predecessor (4M-7) which could only solve a third of the number of tasks. The table also includes an analysis of the upper bound of performance, considering the limitations of tokenization.

read the caption

Table 1: Out-of-the-box (zero-shot) performance. We show the performance for a common subset of tasks: surface normals and depth estimation on DIODE [90], semantic and instance segmentation on COCO [57], k-NN retrieval on ImageNet-1K [79], and 3D human keypoint estimation on 3DPW [91]. We compare to a set of strong baselines and specialist models, including our pseudo labelers. The model learned to solve all the tasks without a loss of performance, is significantly better than the baselines, and is competitive with pseudo labelers, while being a single model for all tasks. Compared to 4M-7, the 4M-21 model preserved its performance while solving 3x more tasks. X denotes that a given model cannot solve the task out-of-the-box. * shows the tokenizer reconstruction quality and provides an estimate on the performance upper bound due to tokenization. See fig. 14 for qualitative comparisons. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

🔼 This table presents the zero-shot performance of 4M-21 on four vision tasks (surface normal and depth estimation, semantic and instance segmentation, k-NN retrieval, 3D human pose estimation). It compares the model against strong baselines and specialist models, highlighting its ability to perform these tasks without specialized training. The results demonstrate comparable or superior performance to specialized models, even with 3 times more tasks than the comparable 4M-7 model.

read the caption

Table 1: Out-of-the-box (zero-shot) performance. We show the performance for a common subset of tasks: surface normals and depth estimation on DIODE [90], semantic and instance segmentation on COCO [57], k-NN retrieval on ImageNet-1K [79], and 3D human keypoint estimation on 3DPW [91]. We compare to a set of strong baselines and specialist models, including our pseudo labelers. The model learned to solve all the tasks without a loss of performance, is significantly better than the baselines, and is competitive with pseudo labelers, while being a single model for all tasks. Compared to 4M-7, the 4M-21 model preserved its performance while solving 3x more tasks. X denotes that a given model cannot solve the task out-of-the-box. * shows the tokenizer reconstruction quality and provides an estimate on the performance upper bound due to tokenization. See fig. 14 for qualitative comparisons. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the 4M-21 model’s zero-shot performance on several vision tasks against various baselines and specialized models. It demonstrates the model’s ability to perform multiple tasks simultaneously without significant performance loss compared to single-task models. The table highlights the model’s improvement over previous versions (4M-7) by solving three times more tasks without performance degradation.

read the caption

Table 1: Out-of-the-box (zero-shot) performance. We show the performance for a common subset of tasks: surface normals and depth estimation on DIODE [90], semantic and instance segmentation on COCO [57], k-NN retrieval on ImageNet-1K [79], and 3D human keypoint estimation on 3DPW [91]. We compare to a set of strong baselines and specialist models, including our pseudo labelers. The model learned to solve all the tasks without a loss of performance, is significantly better than the baselines, and is competitive with pseudo labelers, while being a single model for all tasks. Compared to 4M-7, the 4M-21 model preserved its performance while solving 3x more tasks. X denotes that a given model cannot solve the task out-of-the-box. * shows the tokenizer reconstruction quality and provides an estimate on the performance upper bound due to tokenization. See fig. 14 for qualitative comparisons. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the 4M-21 model’s zero-shot performance against various baselines and specialized models across four common vision tasks: surface normal and depth estimation, semantic and instance segmentation, k-NN retrieval, and 3D human keypoint estimation. It demonstrates that 4M-21 achieves competitive performance with specialized models while being a single model capable of handling all tasks, and shows significantly improved performance over existing multitask models.

read the caption

Table 1: Out-of-the-box (zero-shot) performance. We show the performance for a common subset of tasks: surface normals and depth estimation on DIODE [90], semantic and instance segmentation on COCO [57], k-NN retrieval on ImageNet-1K [79], and 3D human keypoint estimation on 3DPW [91]. We compare to a set of strong baselines and specialist models, including our pseudo labelers. The model learned to solve all the tasks without a loss of performance, is significantly better than the baselines, and is competitive with pseudo labelers, while being a single model for all tasks. Compared to 4M-7, the 4M-21 model preserved its performance while solving 3x more tasks. X denotes that a given model cannot solve the task out-of-the-box. * shows the tokenizer reconstruction quality and provides an estimate on the performance upper bound due to tokenization. See fig. 14 for qualitative comparisons. Best results are bolded, second best underlined.

Full paper#