↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current AI alignment methods rely heavily on human supervision, limiting AI capabilities to human levels. This poses a significant challenge as AI systems are rapidly advancing beyond human capabilities. The research tackles this problem by exploring “easy-to-hard generalization.” This approach trains reward models (evaluators) using human annotations on simple tasks and utilizes these trained evaluators to assess solutions for more complex problems. This allows for scalable AI alignment beyond human expertise.

The proposed easy-to-hard generalization approach uses process-supervised reward models trained on easy tasks to evaluate and improve the generators on hard tasks. Experiments demonstrate successful easy-to-hard generalization across various tasks and model sizes, achieving significant performance gains, particularly in challenging mathematical reasoning benchmarks. The research also investigates various RL approaches for optimizing generators against evaluators, achieving state-of-the-art results. This novel alignment methodology enables AI progress beyond the boundaries of human supervision, which is a significant step towards robust, scalable, and reliable AI development. The key insight is that an evaluator trained on easy tasks can be effectively used to evaluate solutions for harder tasks, thus enabling easy-to-hard generalization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the critical challenge of aligning AI systems that surpass human capabilities. It offers a scalable solution by leveraging human supervision only on easier tasks to evaluate and train models on increasingly complex problems, opening new avenues for research in AI alignment and generalization.

Visual Insights#

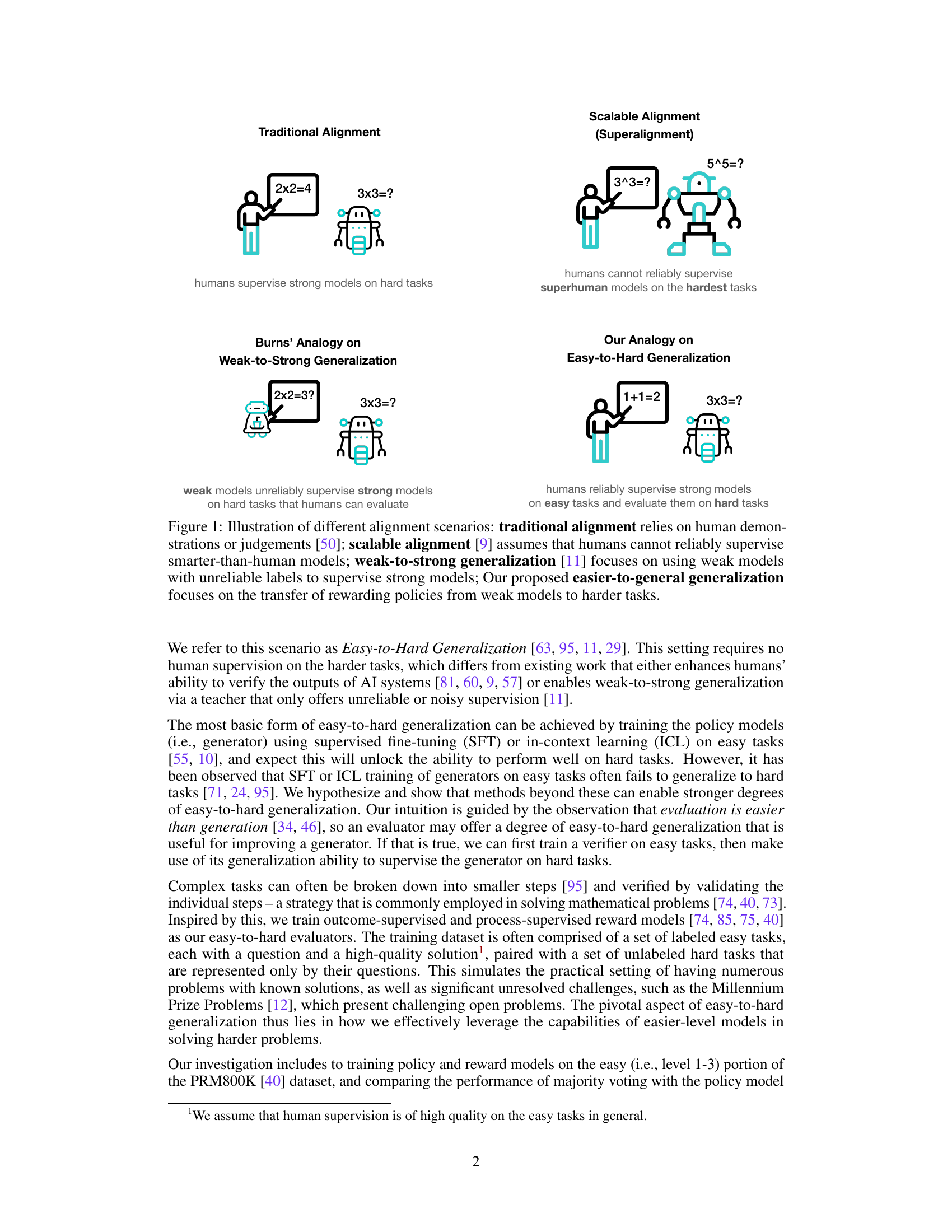

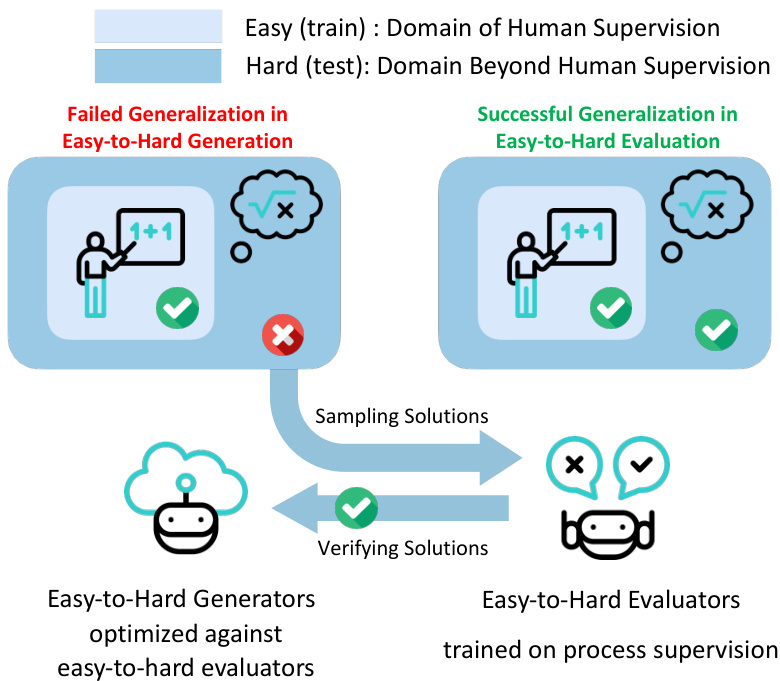

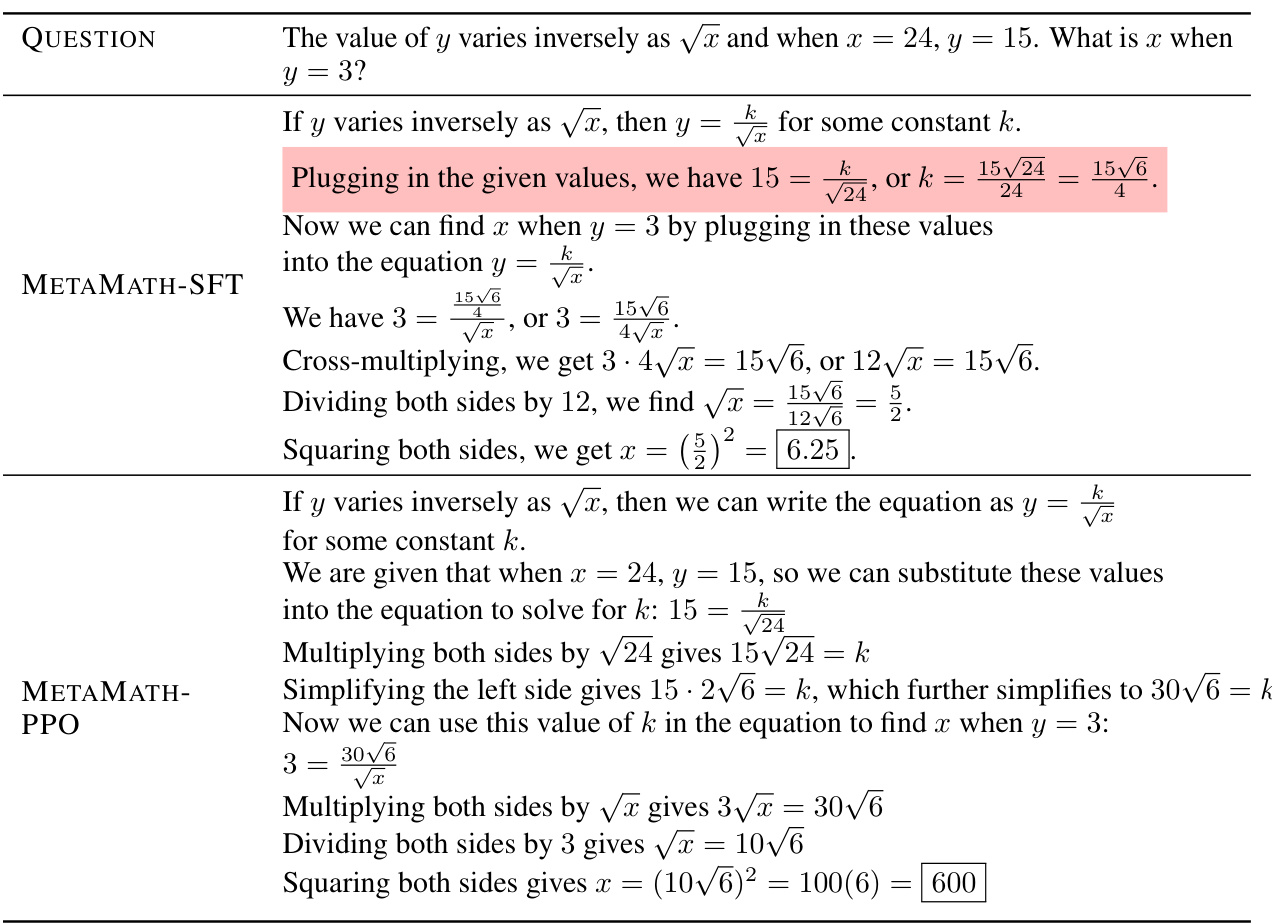

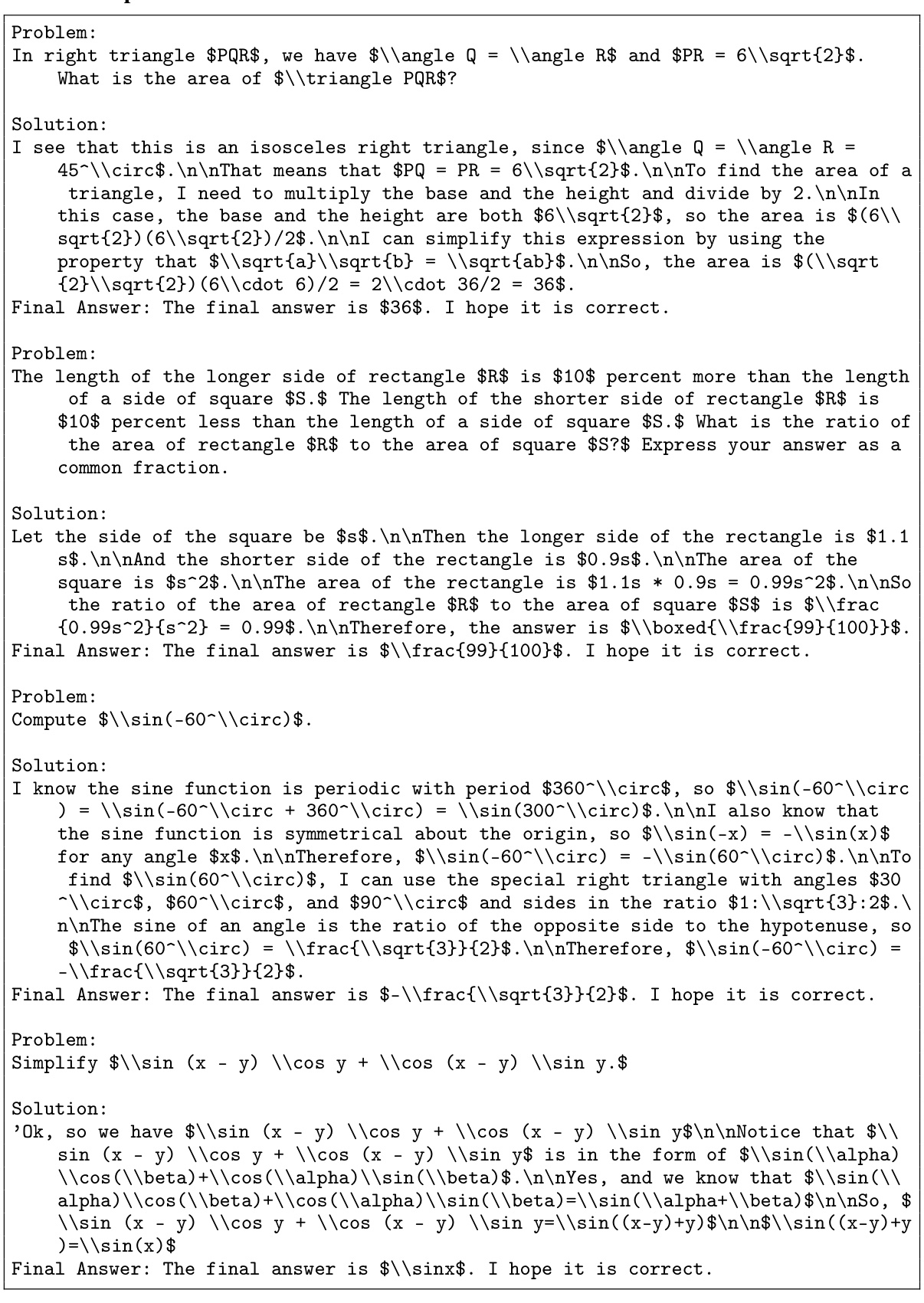

This figure illustrates different AI alignment approaches. Traditional alignment uses human supervision for both easy and hard tasks. Scalable alignment acknowledges the limitations of human supervision when dealing with superhuman models. Weak-to-strong generalization uses weaker models to supervise stronger ones. This paper proposes easy-to-hard generalization, which leverages human supervision on easy tasks to improve performance on harder tasks.

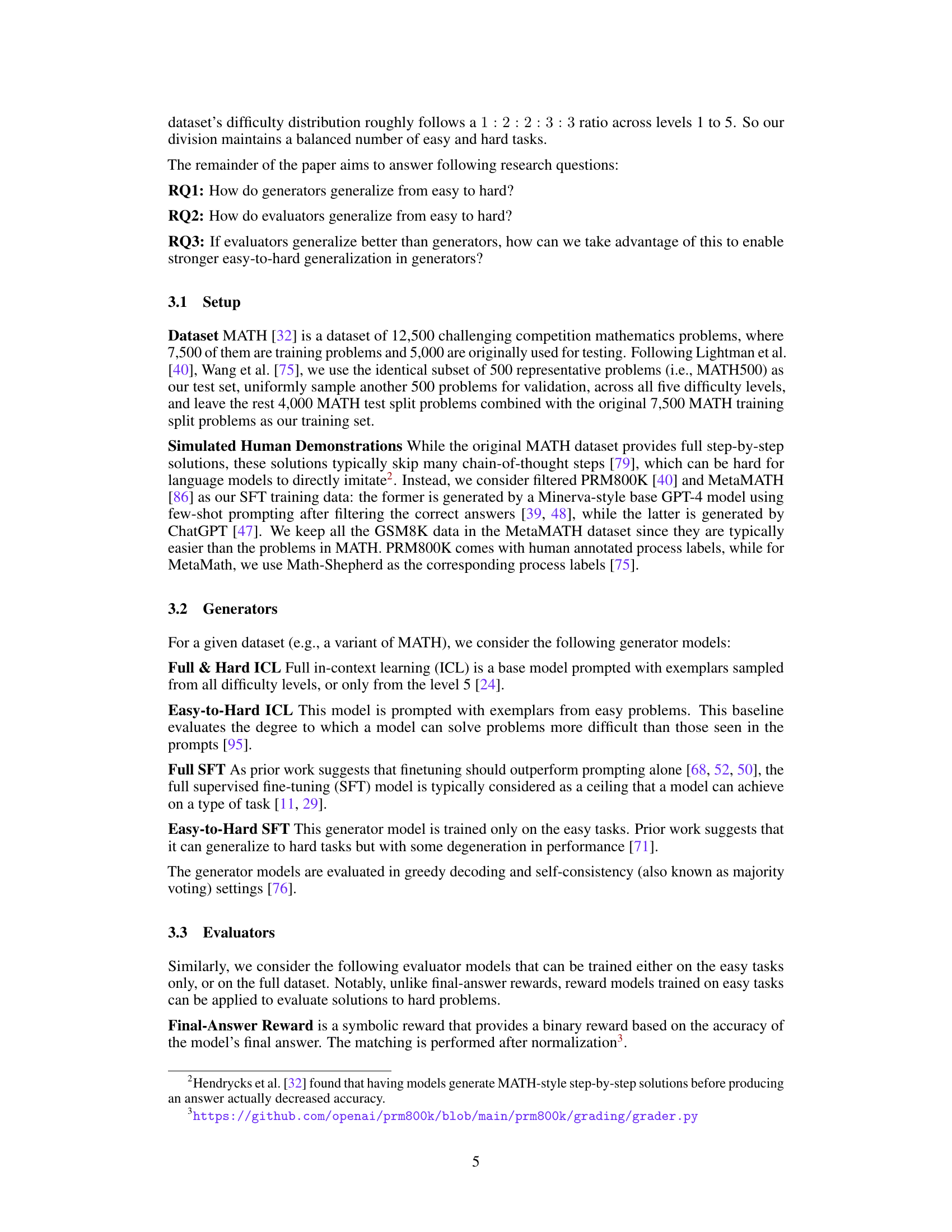

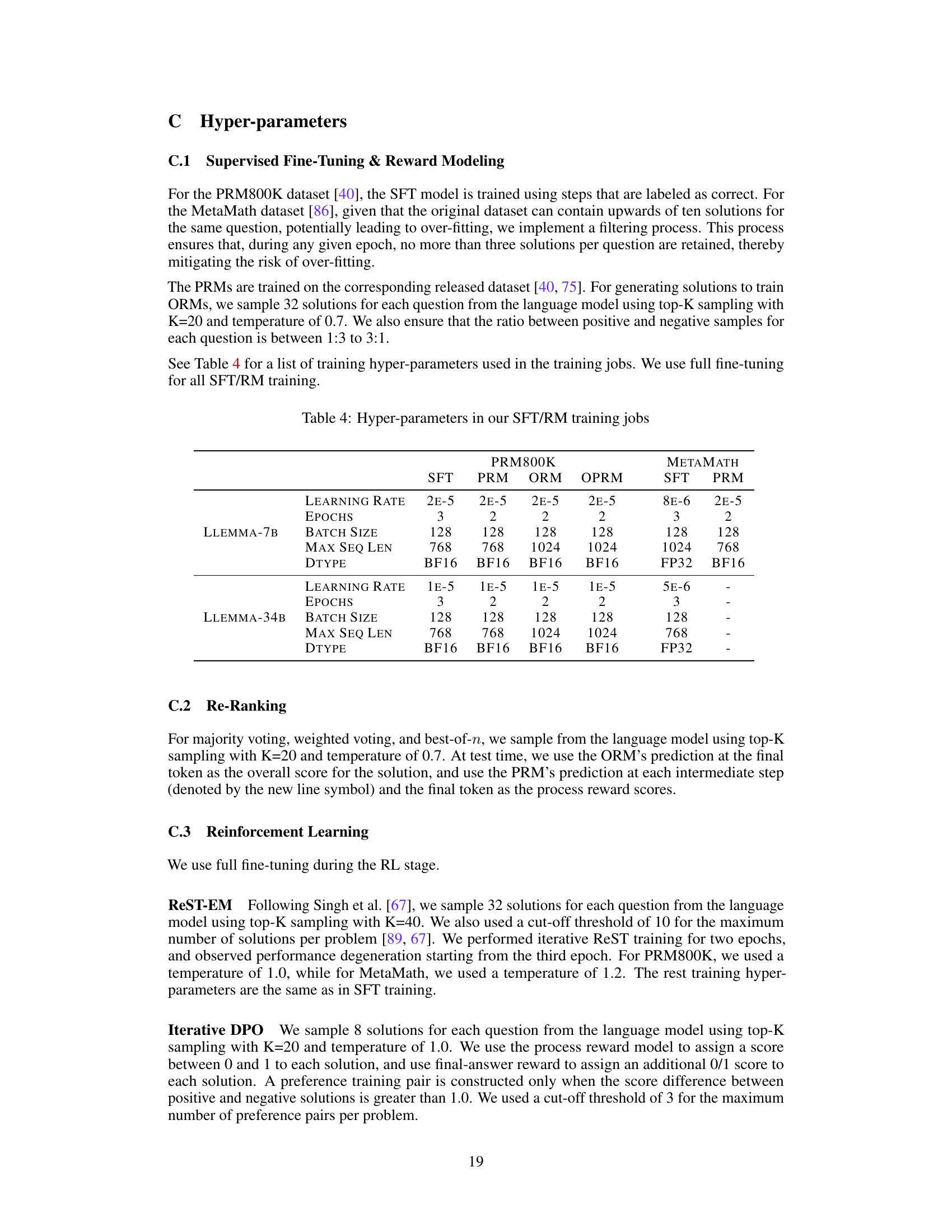

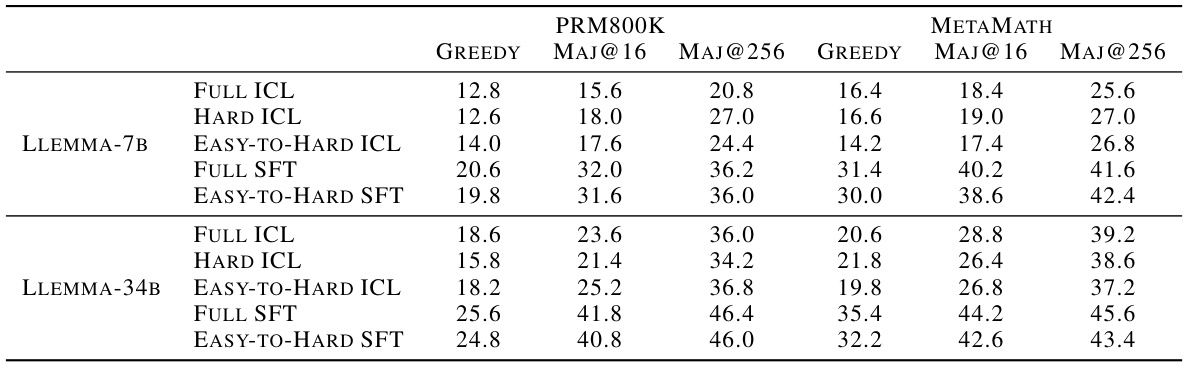

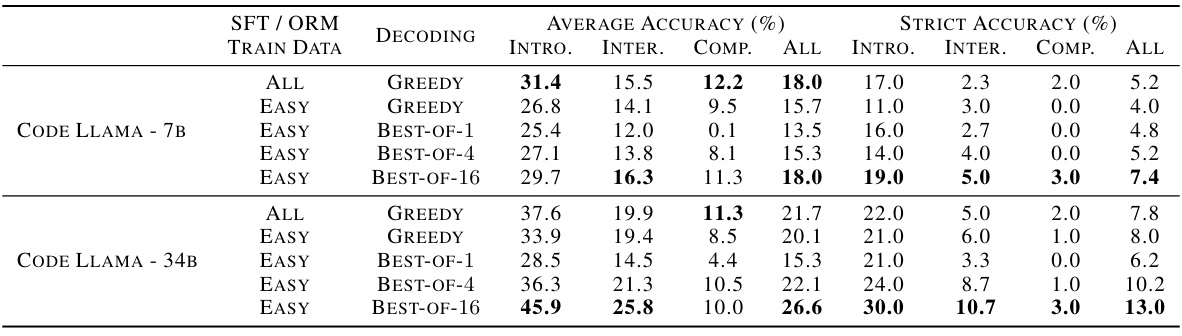

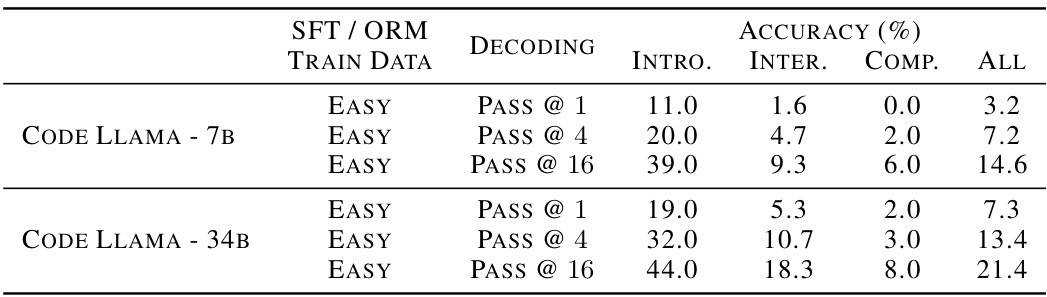

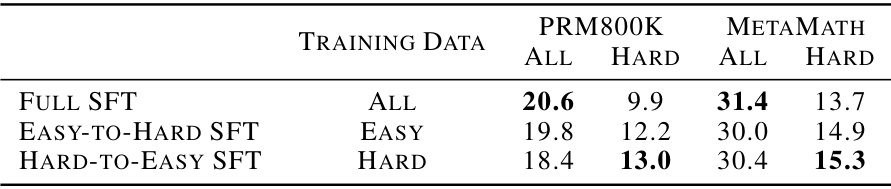

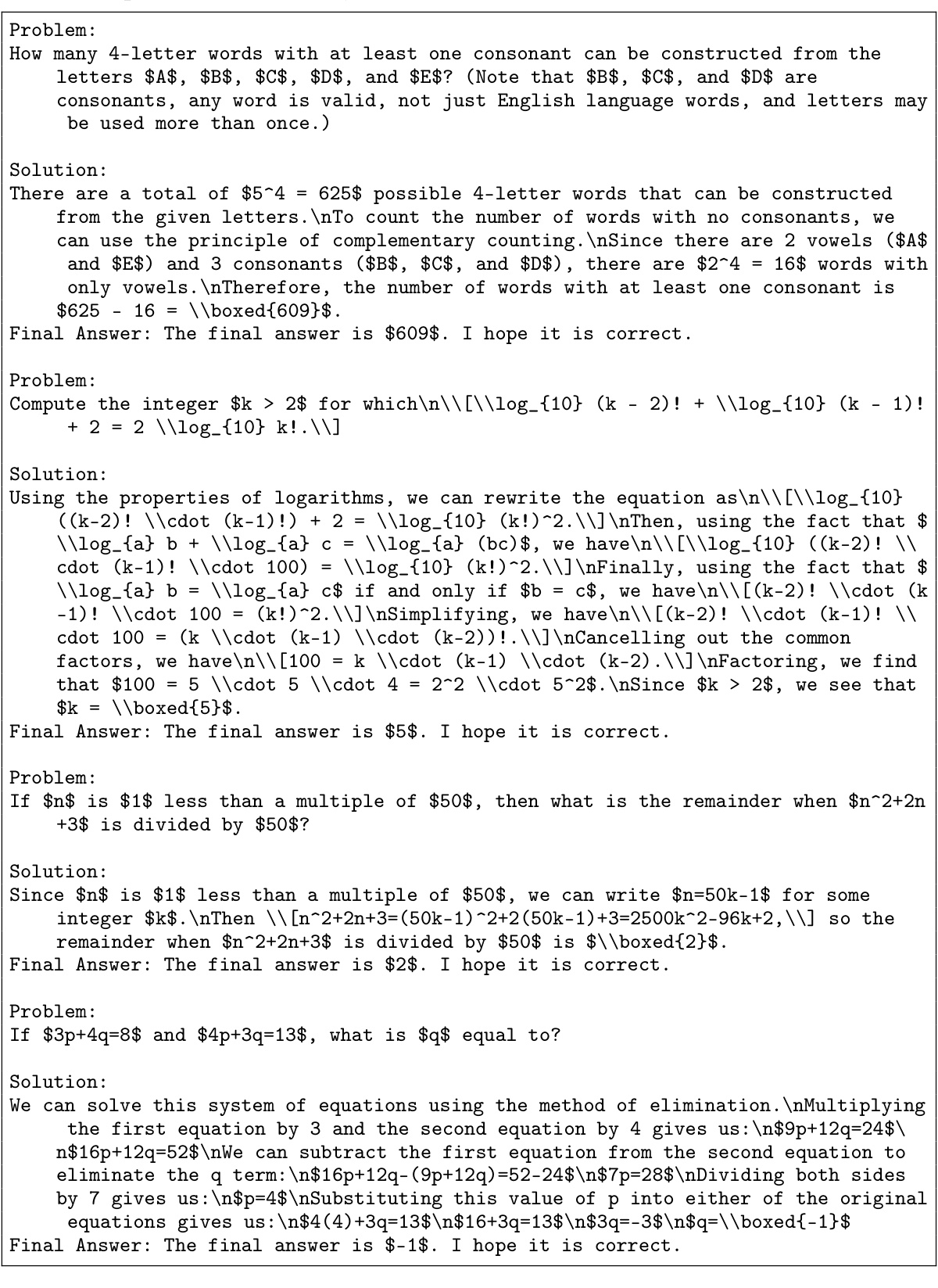

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the easy-to-hard generalization performance of different language models (generators) using various decoding methods. It compares the performance of models trained with different methods (supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and in-context learning (ICL)) and on different datasets (PRM800K and METAMATH). The results are evaluated using accuracy metrics on the MATH500 test set, categorized by decoding settings (Greedy, Majority Voting @16, and Majority Voting @256). The table helps to analyze how effectively different training strategies enable models to generalize from easy to hard tasks.

In-depth insights#

Easy-to-hard scaling#

Easy-to-hard scaling in AI research focuses on training models on simpler tasks before progressing to more complex ones. This approach is valuable because it can mitigate the need for extensive human annotation on difficult problems, which is often expensive, time-consuming, and even impossible for tasks exceeding human capabilities. The core idea is that learning from easier tasks helps the model acquire foundational knowledge and skills that transfer to harder tasks, improving generalization. A key aspect is the design of appropriate reward models or evaluation metrics that work effectively across both easy and hard task domains, providing sufficient guidance during training. Successful easy-to-hard scaling hinges on the model’s ability to effectively transfer knowledge, highlighting the importance of careful feature engineering, architectural choices, and training strategies that facilitate knowledge transfer. Challenges include ensuring the reward model’s robustness and preventing the model from overfitting to the easier tasks, potentially hindering performance on the more challenging problems. Further research should explore optimal training strategies, more sophisticated reward model designs, and rigorous evaluation methodologies to fully realize the potential of easy-to-hard scaling.

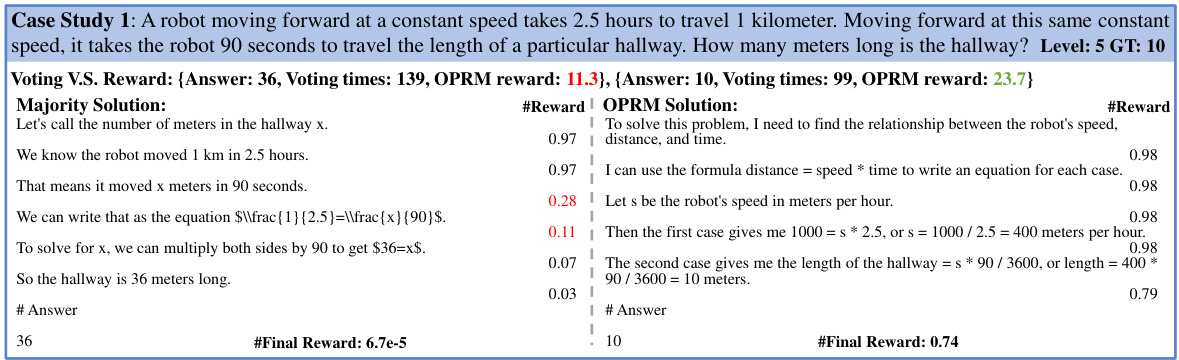

Reward model power#

The concept of “Reward model power” in the context of AI alignment is crucial. A powerful reward model effectively guides the AI agent towards desired behavior, especially in complex tasks beyond human supervision. The accuracy and generalizability of the reward model are paramount. A model trained only on easy tasks, exhibiting easy-to-hard generalization, might still provide effective feedback for complex scenarios. Process-supervised reward models (PRMs) and Outcome & Process Reward Models (OPRMs), by focusing on the step-by-step reasoning or the final outcome, respectively, demonstrate improved performance in guiding AI systems towards correct solutions. However, the quality of training data significantly influences the reward model’s performance. High-quality data leads to stronger easy-to-hard generalization and better model performance. Conversely, less-quality data might result in a model that overfits to superficial aspects of tasks, hindering its applicability to harder problems. Ultimately, the success hinges on a synergistic interplay between reward model design, training data quality, and reinforcement learning strategies to ensure alignment.

RL surpasses SFT#

The assertion that “RL surpasses SFT” in the context of AI alignment necessitates a nuanced examination. While Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) directly leverages human-labeled data for model training, Reinforcement Learning (RL) introduces a feedback loop, allowing models to iteratively refine their behavior based on performance. This iterative process, guided by reward models, is particularly effective in aligning models to complex and subjective human preferences, exceeding the capabilities of SFT which is limited by the static nature of its training data. However, RL’s success hinges critically on the quality and design of the reward model. A poorly designed reward model can lead to unintended and harmful behaviors, whereas a well-crafted one empowers RL to achieve alignment beyond what’s achievable through SFT alone. Therefore, a direct comparison of RL and SFT’s efficacy is insufficient without acknowledging the significance of the reward model’s role in RL’s performance. The claim that RL surpasses SFT should thus be considered in the context of sophisticated and carefully designed reward mechanisms, rather than as a general, unconditional statement.

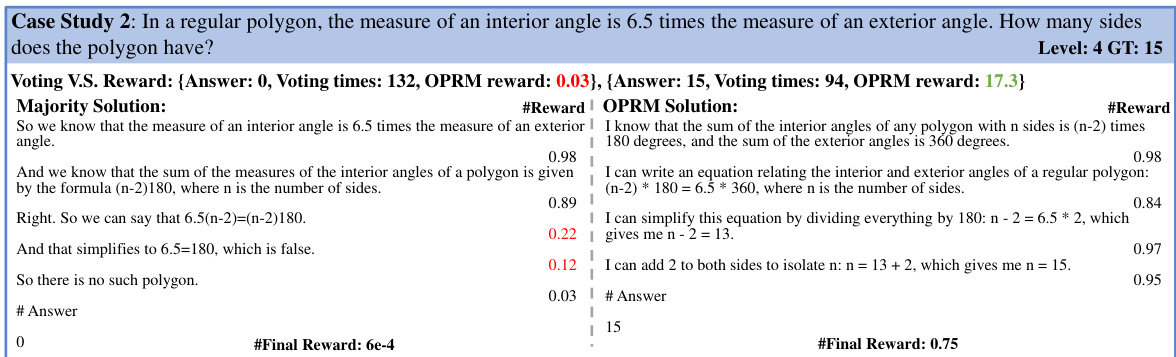

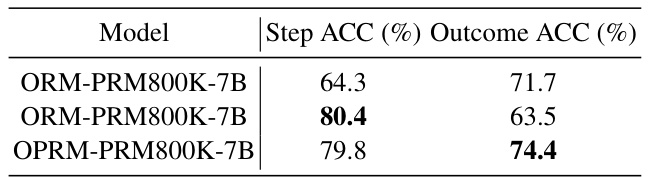

OPRM effectiveness#

The effectiveness of the Outcome & Process Reward Model (OPRM) is a central theme, demonstrating its ability to improve the accuracy of hard tasks significantly compared to using only Outcome Reward Models (ORMs) or Process Reward Models (PRMs). This stems from OPRM’s unique combination of evaluating both the correctness of individual reasoning steps and the final outcome, leading to a more robust and comprehensive evaluation of solution quality. Training the OPRM on a mix of PRM and ORM data enhances its capabilities, achieving better performance than either model alone. The results highlight OPRM’s capacity to generalize effectively from easier to harder tasks, suggesting its potential for training AI systems that advance beyond human supervision and improve the reliability of AI-generated solutions for complex problems. Importantly, the performance gains were noted on various datasets, suggesting a significant advance in the field of AI alignment.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this easy-to-hard generalization work could explore several promising avenues. Improving the scalability of the approach is crucial, potentially through more efficient reward model training or the development of techniques that require less human supervision in the initial easy-task training phase. Another key area is exploring alternative reward model architectures. While the study uses process-supervised reward models, further investigation into outcome-based reward models, or hybrid approaches, could potentially lead to even greater improvements in generalizability. Extending the methodology to other domains beyond mathematical problem-solving remains a valuable pursuit. The success of the approach hinges on the availability of easy tasks for initial supervision, so identifying appropriate easy-to-hard task decompositions in different application areas like code generation or scientific discovery is key. Finally, a deeper understanding of why and when easy-to-hard generalization fails would refine the methodology. Careful analyses of model behaviors across different task domains and difficulty levels could yield insights into the robustness and limitations of this approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates four different alignment scenarios. Traditional alignment uses human demonstrations or judgments for training models on hard tasks. Scalable alignment, or superalignment, acknowledges the limitations of human supervision for superhuman models, which means human cannot reliably supervise superhuman models on hardest tasks. Weak-to-strong generalization utilizes weak models with unreliable labels to supervise strong models, and this paper proposes easier-to-hard generalization which focuses on transferring rewarding policies from easy tasks to harder tasks.

This figure illustrates four different AI alignment scenarios. Traditional alignment uses human demonstrations or judgements to supervise models, limiting capabilities to human levels. Scalable alignment acknowledges that humans can’t supervise superhuman models. Weak-to-strong generalization utilizes weaker models with unreliable labels to supervise stronger ones. The paper introduces easy-to-hard generalization, transferring rewarding policies from easier tasks to improve performance on harder tasks, overcoming the limitations of other methods.

This figure illustrates four different AI alignment approaches. Traditional alignment uses human supervision for both easy and hard tasks. Scalable alignment acknowledges the limitations of human supervision for superhuman models. Weak-to-strong generalization explores the use of weaker models for supervision, accepting lower reliability. The authors’ proposed Easy-to-Hard generalization focuses on transferring reward policies learned from easier tasks to harder tasks, minimizing reliance on human supervision for challenging problems.

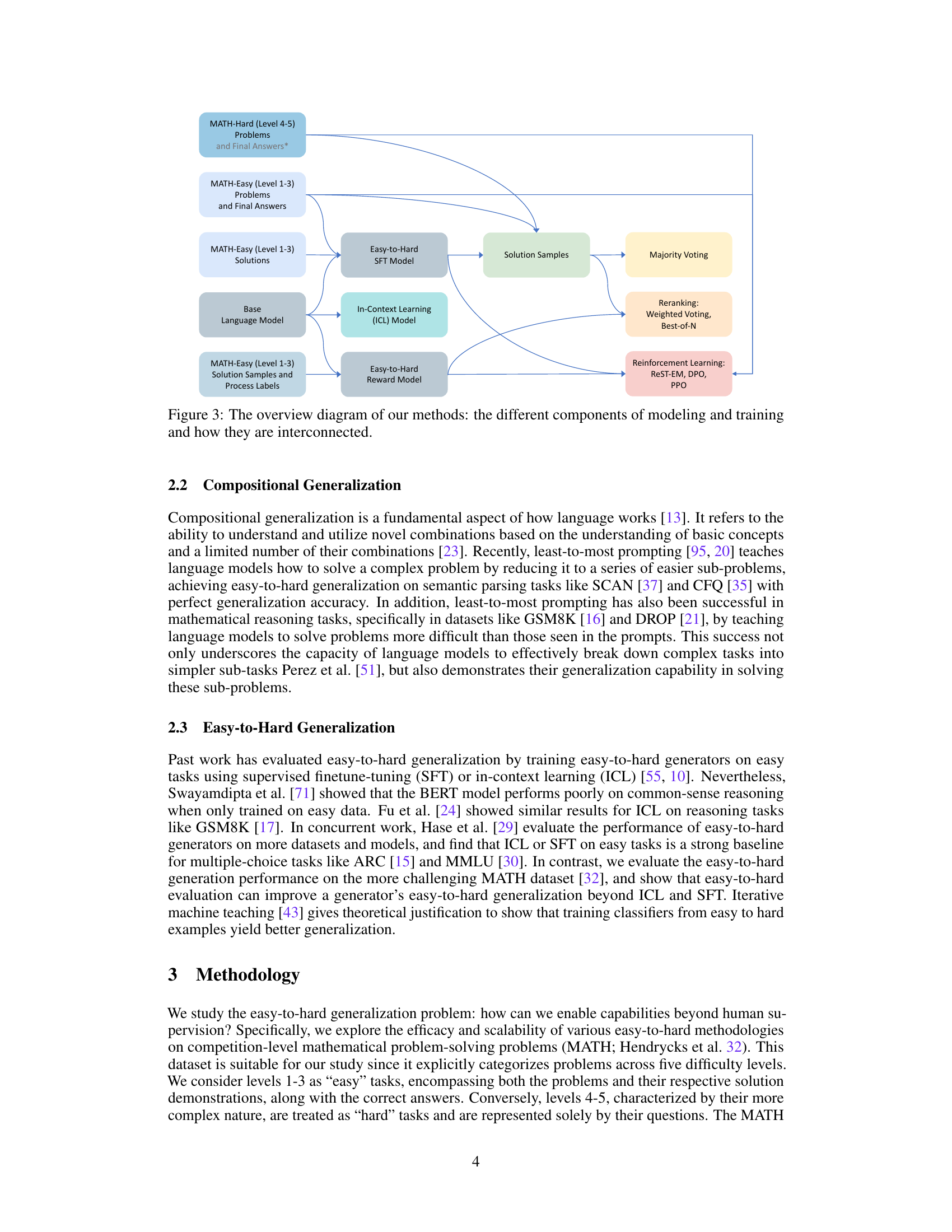

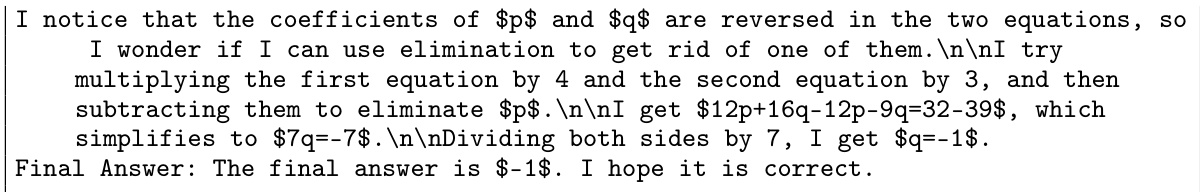

This figure illustrates the two-stage training process proposed in the paper. First, an evaluator model is trained using process supervision on easier tasks. This trained evaluator is then used to assess the output of a generator model on harder tasks. The generator model can be optimized through techniques like re-ranking or reinforcement learning based on the evaluator’s feedback, enabling generalization from easy to hard tasks without relying on human supervision for the harder tasks.

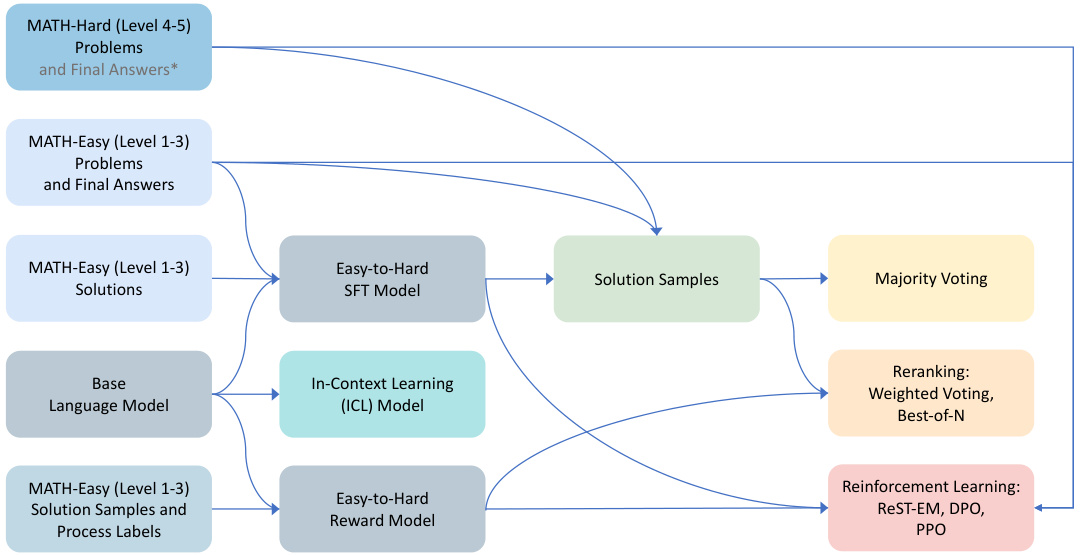

This figure shows a flowchart of the training process for the proposed easy-to-hard generalization method. It details the different components used: a base language model, easy-to-hard supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and in-context learning (ICL) models (generators), and an easy-to-hard reward model (evaluator). The generators produce solution samples, which are then evaluated by majority voting, reranking methods (weighted voting, best-of-N), or reinforcement learning (REST-EM, DPO, PPO). The training data consists of easy and hard mathematical problems. Easy problems and their solutions (including process labels for the reward model) are used to train the models. The performance of the trained models is then evaluated on hard problems.

This figure illustrates the two-stage process of the proposed easy-to-hard generalization approach. First, an evaluator model (reward model) is trained using process supervision (or outcome supervision as a proxy) on easier tasks. This trained evaluator is then used to assess candidate solutions generated for harder tasks, guiding the generation process through either re-ranking or reinforcement learning (RL). This shows how leveraging evaluation on easy tasks can enable generation on hard tasks, thereby scaling alignment beyond human supervision.

This figure illustrates the two-stage process of the proposed easy-to-hard generalization approach. First, an evaluator (reward model) is trained using process supervision (or outcome supervision as a proxy) on easy tasks. This trained evaluator is then used to facilitate generation on harder tasks by either re-ranking candidate solutions generated by a separate generator model or through reinforcement learning (RL) where the evaluator provides feedback to guide the generator’s improvement on harder problems.

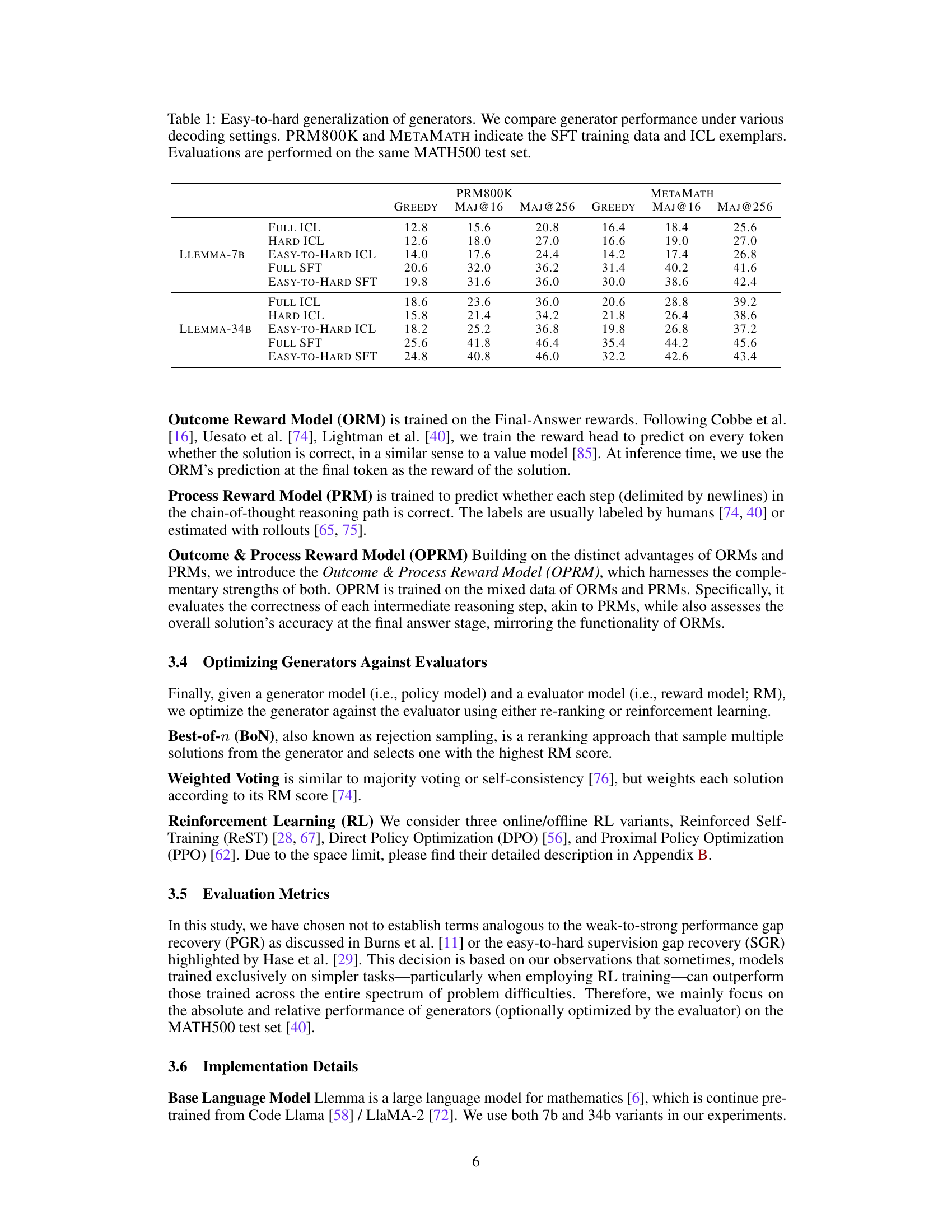

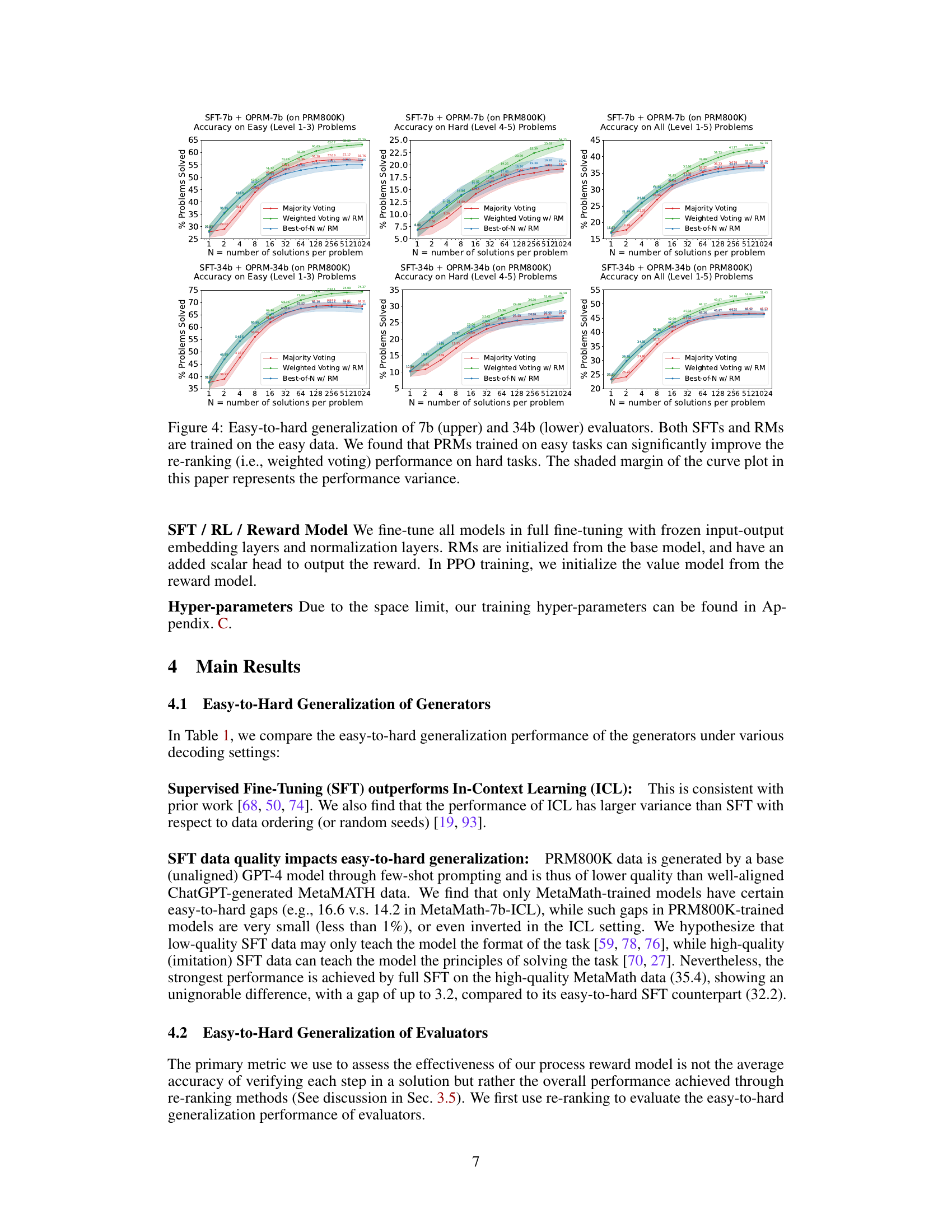

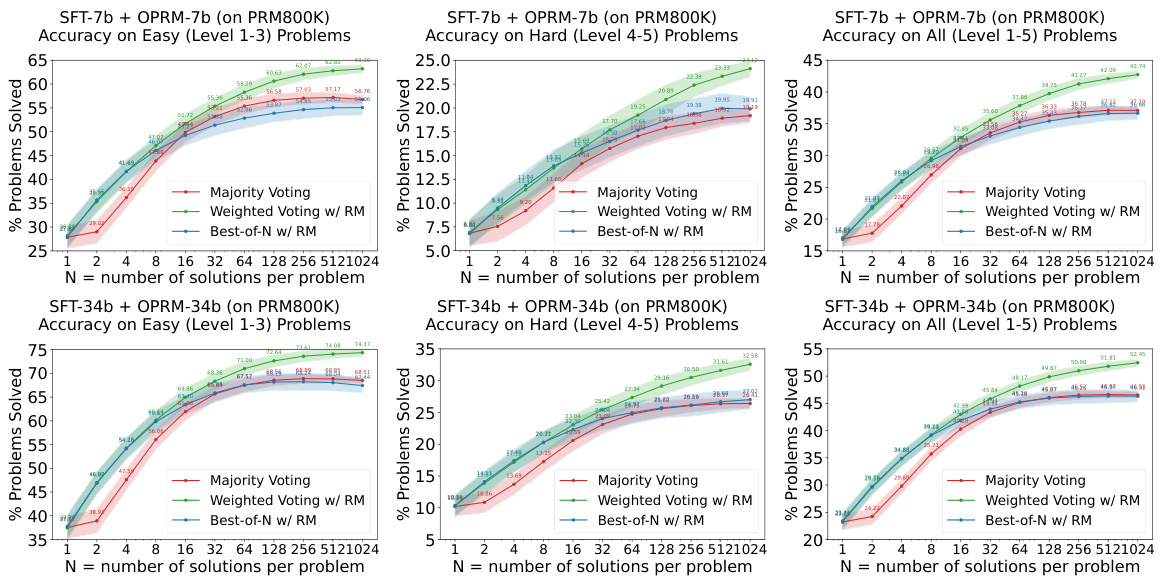

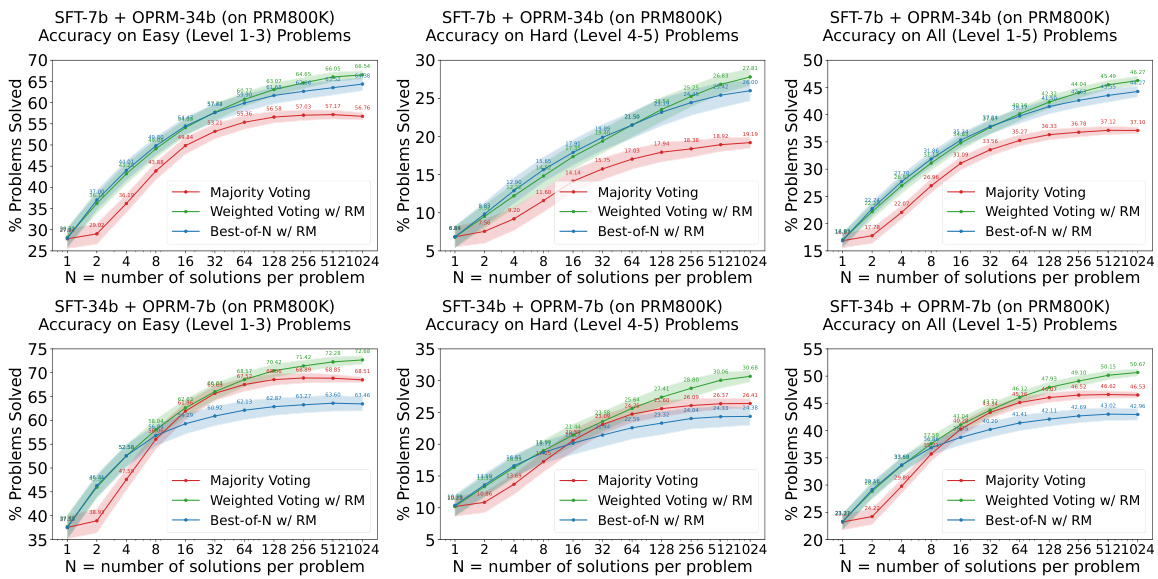

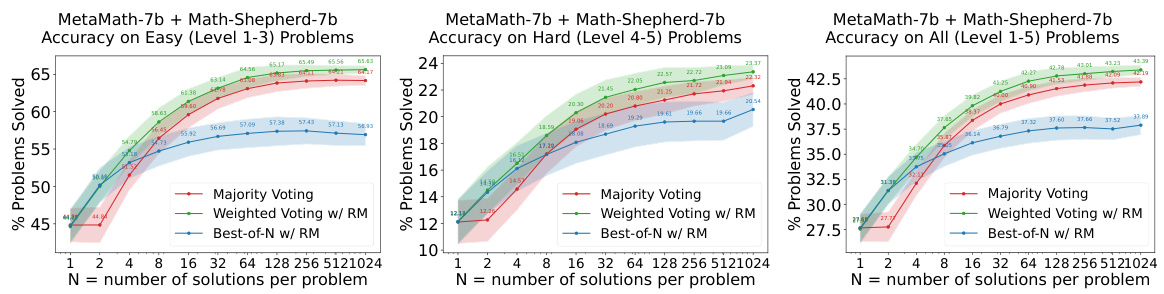

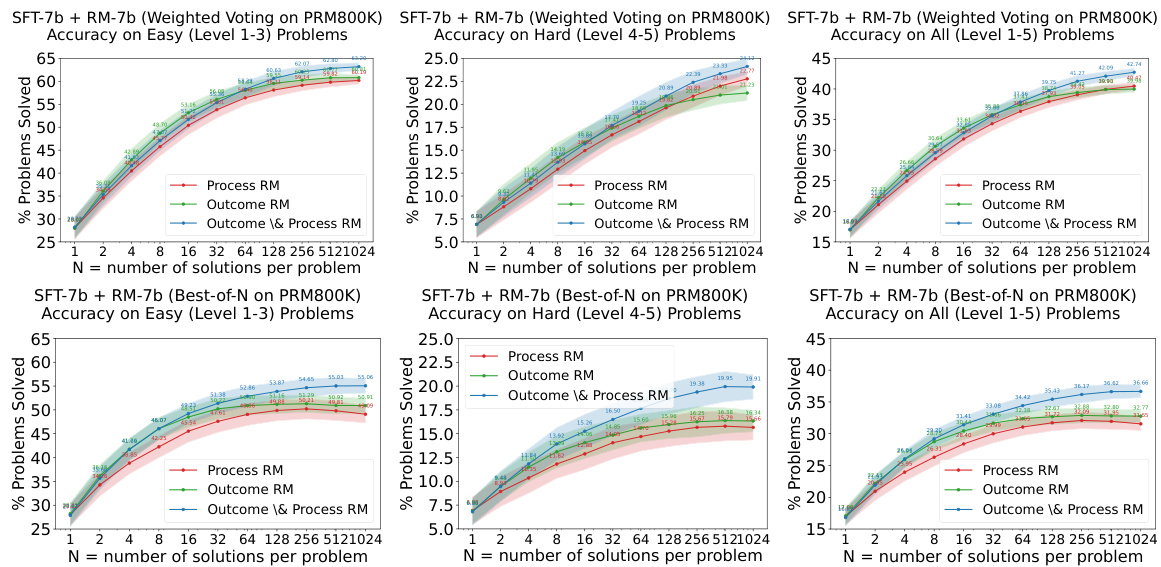

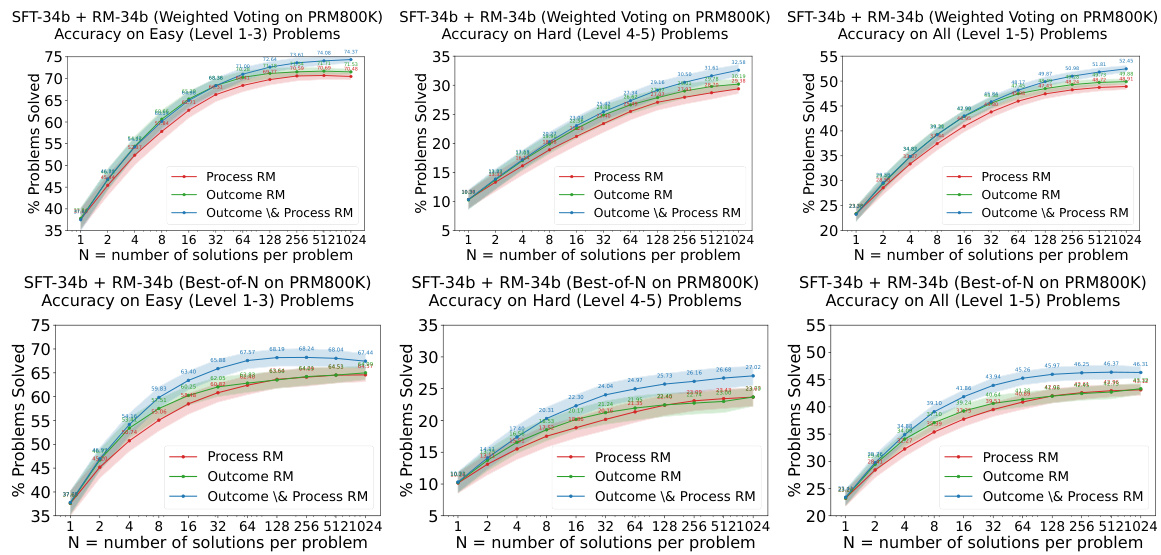

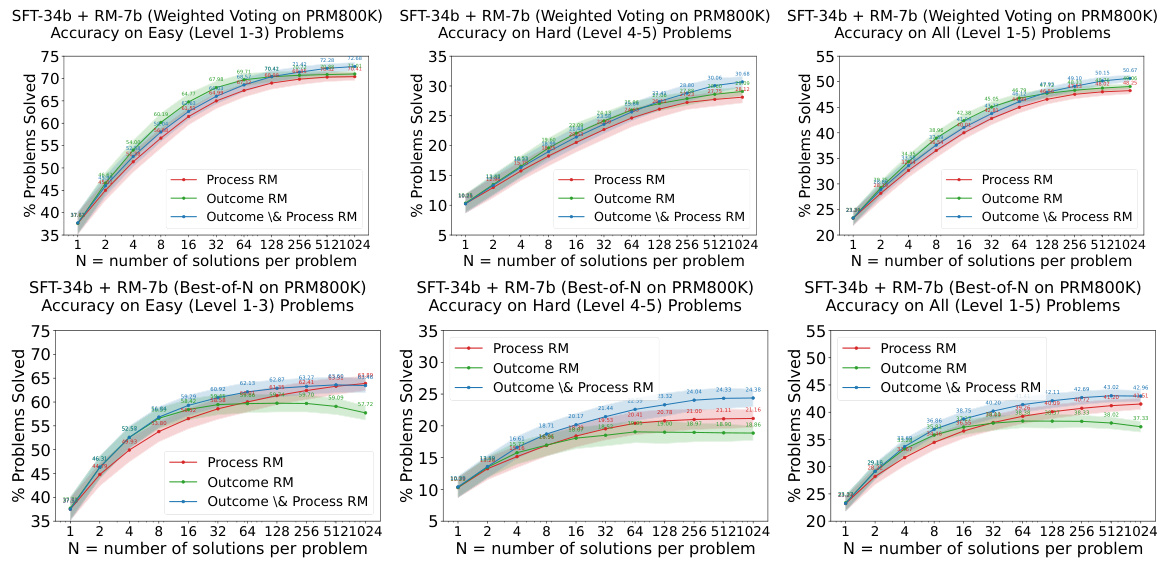

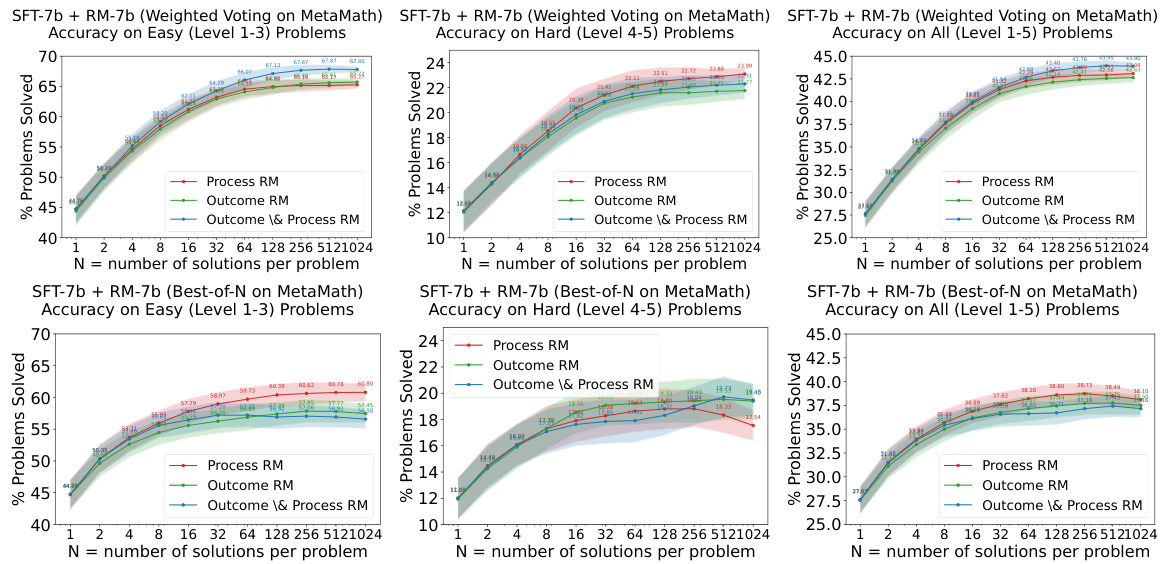

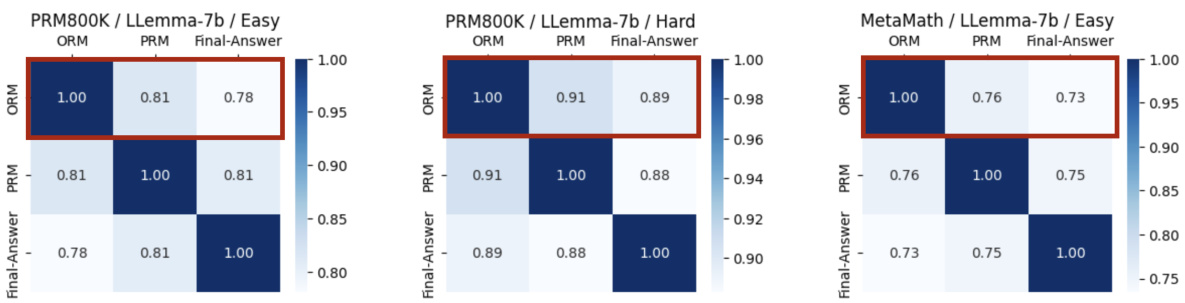

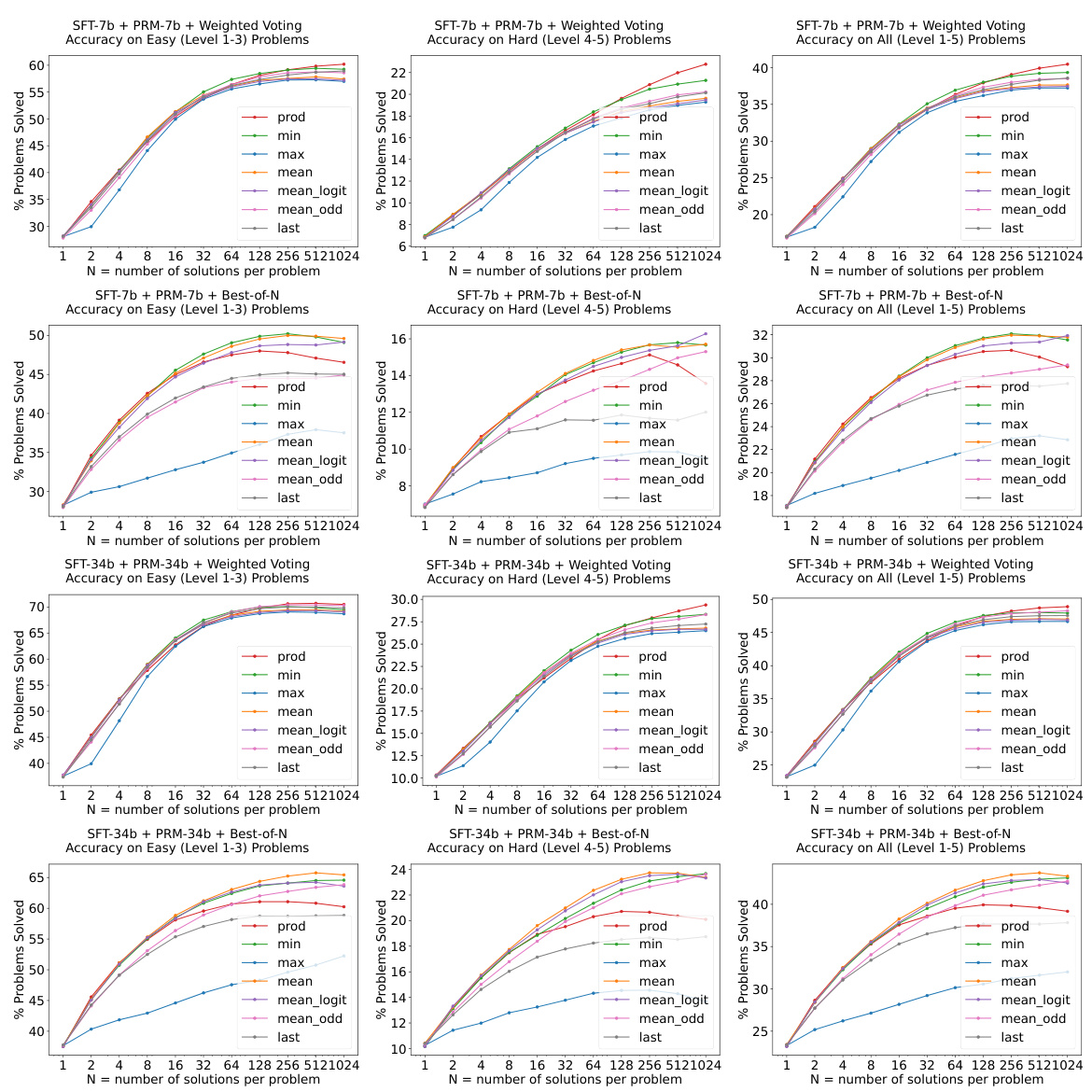

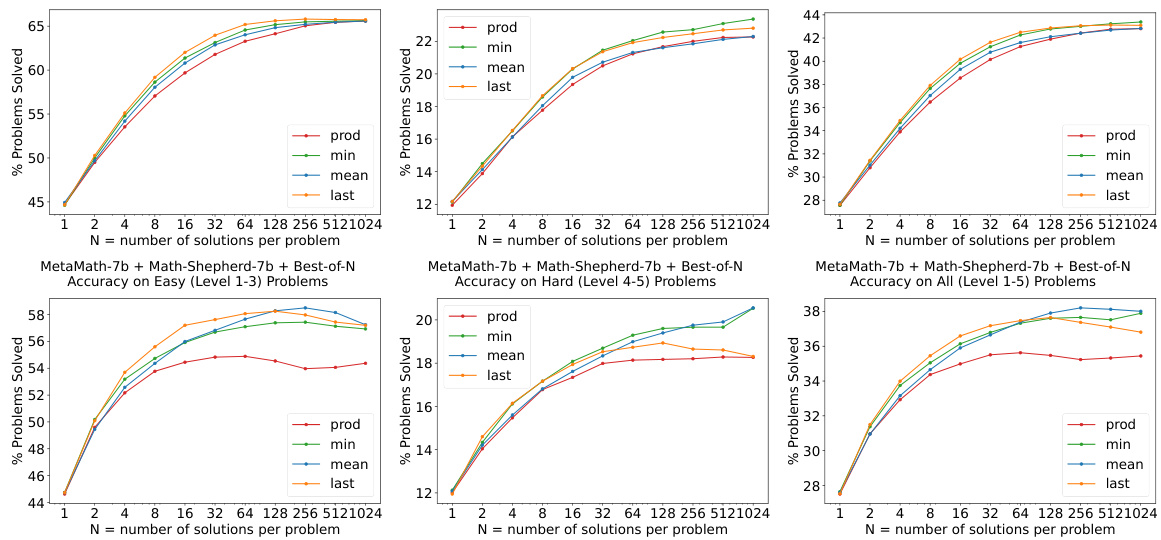

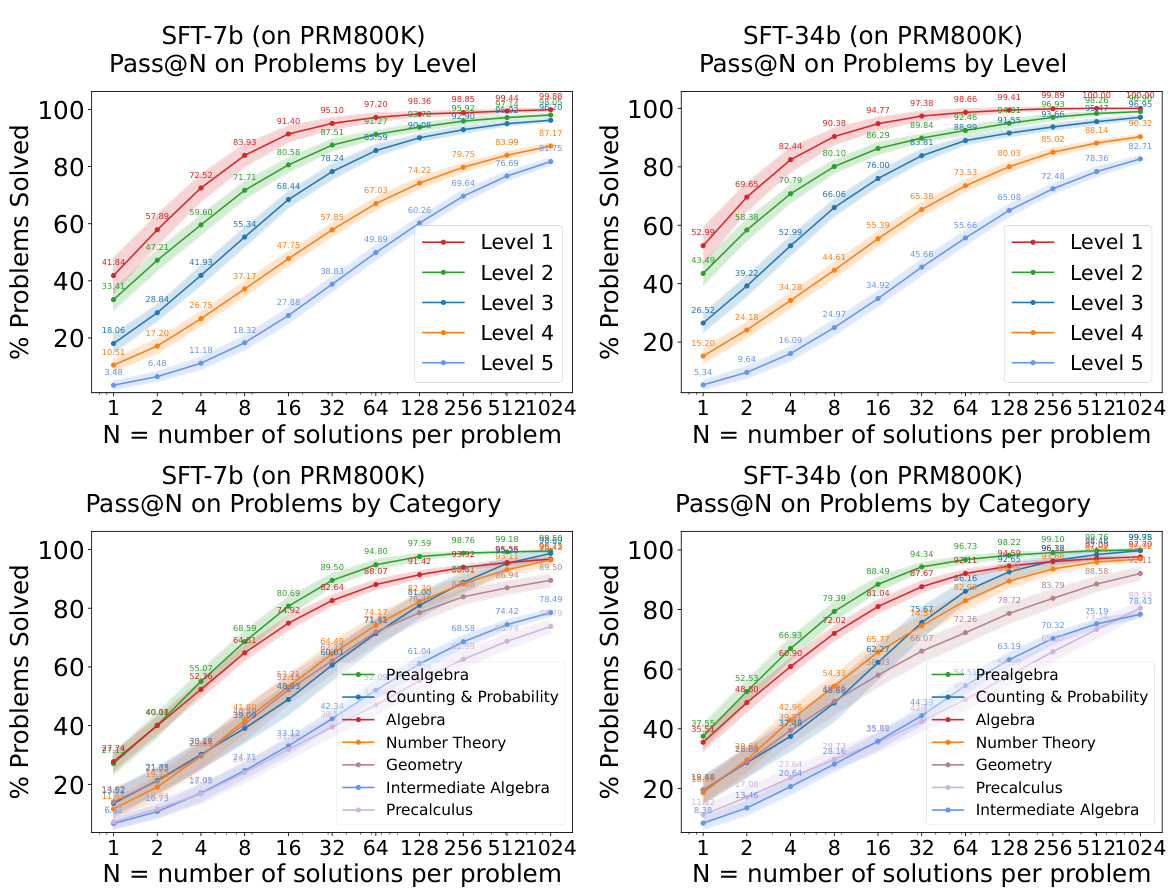

This figure shows the results of experiments evaluating the easy-to-hard generalization capabilities of 7B and 34B evaluators. Both the Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) models and Reward Models (RMs) were trained only on easy problems. The figure demonstrates that Process Reward Models (PRMs), when used for re-ranking (weighted voting), significantly improve performance on hard tasks compared to using the SFT models alone. The shaded regions represent the performance variance across multiple runs.

This figure shows the performance of 7B and 34B evaluators on easy and hard tasks using different re-ranking methods (Majority Voting, Weighted Voting with Reward Model, and Best-of-N with Reward Model). The results demonstrate that reward models (RMs), particularly those trained on easier problems (PRM), significantly enhance the performance of re-ranking methods, especially on harder tasks.

This figure illustrates the overall process of the proposed easy-to-hard generalization approach. It consists of two main stages: training an evaluator (reward model) and using it to optimize a generator (policy model). The evaluator is trained on easy problems with either process supervision (step-by-step guidance) or outcome supervision (only final answer is supervised), to allow easy-to-hard generalization. Then, this trained evaluator is used to assess the performance of the generator in hard tasks, to improve its performance through re-ranking (selecting best solutions) or reinforcement learning (RL).

This figure illustrates the process of easy-to-hard generalization. It shows that an evaluator model, trained on process supervision from easier tasks, can be used to effectively evaluate candidate solutions for harder tasks. This evaluation is then used to improve the generator model’s performance on these harder tasks through techniques like re-ranking or reinforcement learning. The diagram visually represents the two stages: training the evaluator and then using it to improve the generator.

This figure illustrates the process of easy-to-hard generalization. It starts by training evaluators (reward models) on easy tasks using either process supervision or outcome supervision (simulated process supervision). These trained evaluators are then used to score candidate solutions for harder tasks, thus facilitating easy-to-hard generalization in generators (policy models). This generalization is achieved through either re-ranking of generated solutions based on the evaluator scores or via reinforcement learning (RL), where the evaluator’s scores act as rewards to guide the learning process of the generator.

This figure illustrates the pipeline of the proposed easy-to-hard generalization approach. It starts by training an evaluator model (reward model) on easy tasks using process supervision or outcome supervision. This trained evaluator is then used to assess candidate solutions generated for harder tasks. This assessment is used to improve the solution generation process through re-ranking or reinforcement learning (RL), enabling the model to generalize from easy to hard tasks without direct human supervision on the hard tasks.

This figure displays the performance of 7B and 34B evaluators (reward models) on easy and hard tasks from the MATH dataset. Both the SFT (supervised fine-tuning) models and Reward Models (RMs) are initially trained only on the easier tasks (levels 1-3). The figure demonstrates that using process-supervised reward models (PRMs) trained on the easier tasks leads to significantly improved performance in re-ranking (specifically weighted voting) on harder tasks (levels 4-5). The shaded regions around the lines show the performance variance.

This figure illustrates the two-stage training process of the proposed method. First, evaluators are trained using process supervision or outcome supervision (simulating process supervision) on easy problems to facilitate easy-to-hard evaluation. Subsequently, these trained evaluators are used to improve the generation process on hard problems. This improvement is done via re-ranking techniques or Reinforcement Learning (RL).

This figure illustrates the proposed easy-to-hard generalization approach. It shows a two-stage process: first, training an evaluator (reward model) using process or outcome supervision on easy tasks; and second, using this trained evaluator to improve the performance of generators (policy models) on hard tasks via re-ranking or reinforcement learning (RL). The figure visually depicts the flow of information and the distinct roles of evaluators and generators in achieving scalable alignment beyond human supervision.

This figure illustrates the easy-to-hard generalization framework. It shows how evaluators, trained on easier tasks with process supervision (or outcome supervision simulating this), are used to assess solutions to harder tasks. This assessment then facilitates the generation of solutions to harder tasks via techniques like re-ranking (selecting the best solutions based on evaluator scores) or reinforcement learning (RL, using evaluator scores as rewards to guide model training). The figure highlights the successful transfer of evaluation capabilities from easy to hard tasks, thereby enabling scalable alignment beyond the limits of human supervision.

This figure showcases the results of experiments evaluating the easy-to-hard generalization capabilities of 7B and 34B evaluators (reward models). Both the supervised fine-tuning (SFT) models and reward models (RMs) were trained only on easy-level problems. The key finding is that process reward models (PRMs) trained on easy problems significantly enhance the performance of re-ranking (weighted voting) methods on difficult problems. The shaded areas represent the variance in performance across multiple runs.

This figure illustrates the methodology of the proposed approach. It shows that the evaluators are trained using process supervision or outcome supervision on easy tasks to enable easy-to-hard evaluation. Then, the trained evaluators are used to improve the generators by facilitating easy-to-hard generation via re-ranking or reinforcement learning (RL).

This figure shows the results of experiments evaluating the easy-to-hard generalization performance of 7B and 34B evaluators. The evaluators (Reward Models) were trained only on easy tasks (levels 1-3), then tested on easy, hard (levels 4-5), and all tasks. The results demonstrate that process-supervised reward models (PRMs) trained on easy tasks significantly improve the accuracy of re-ranking (weighted voting and best-of-N) methods on harder tasks. The shaded areas represent performance variance.

This figure illustrates the two-stage training process of the proposed easy-to-hard generalization method. In the first stage, an evaluator model (reward model) is trained on easier tasks using process or outcome supervision. In the second stage, this trained evaluator is then used to improve the performance of a generator model (policy model) on harder tasks through re-ranking or reinforcement learning. This demonstrates the effectiveness of using easy-to-hard evaluation to facilitate easy-to-hard generalization in the generator.

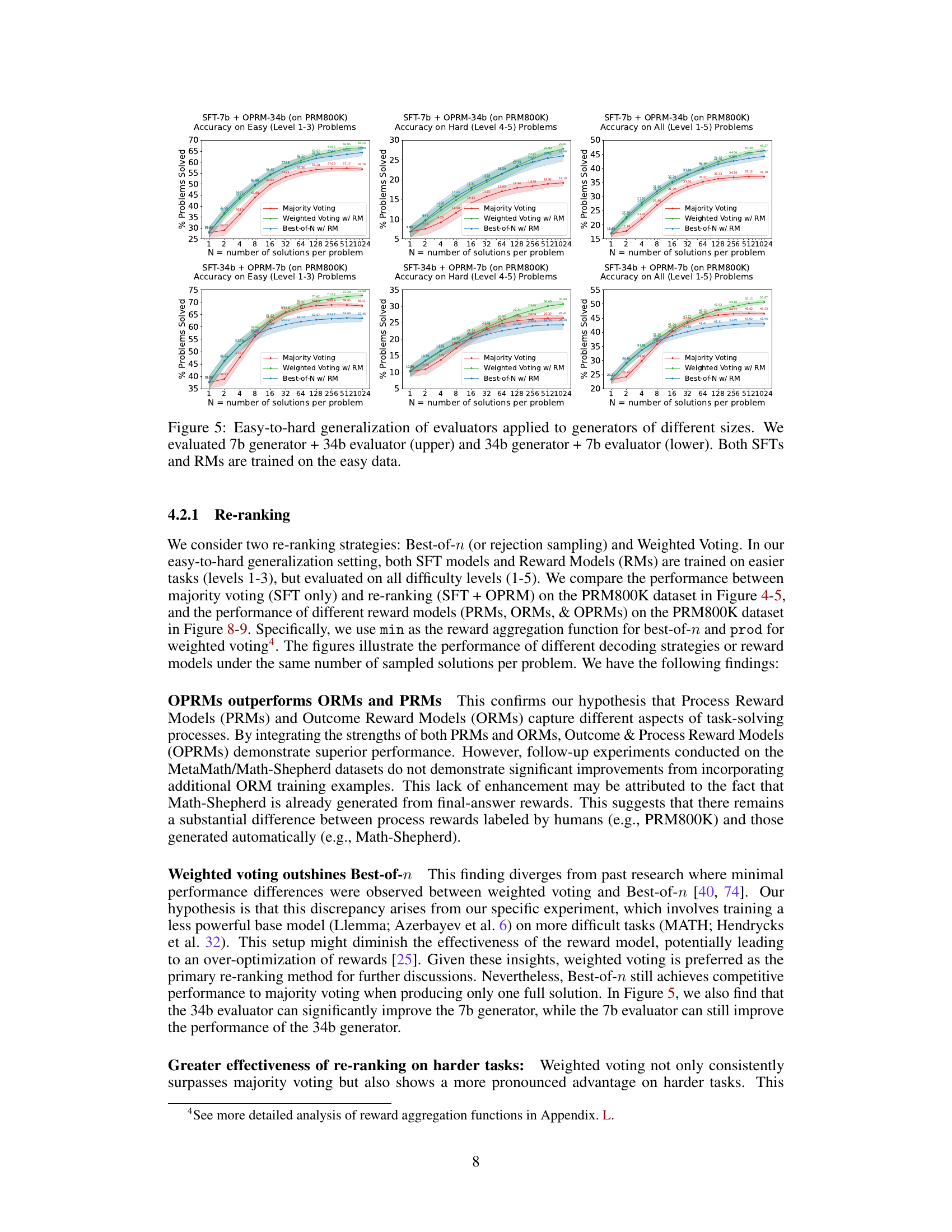

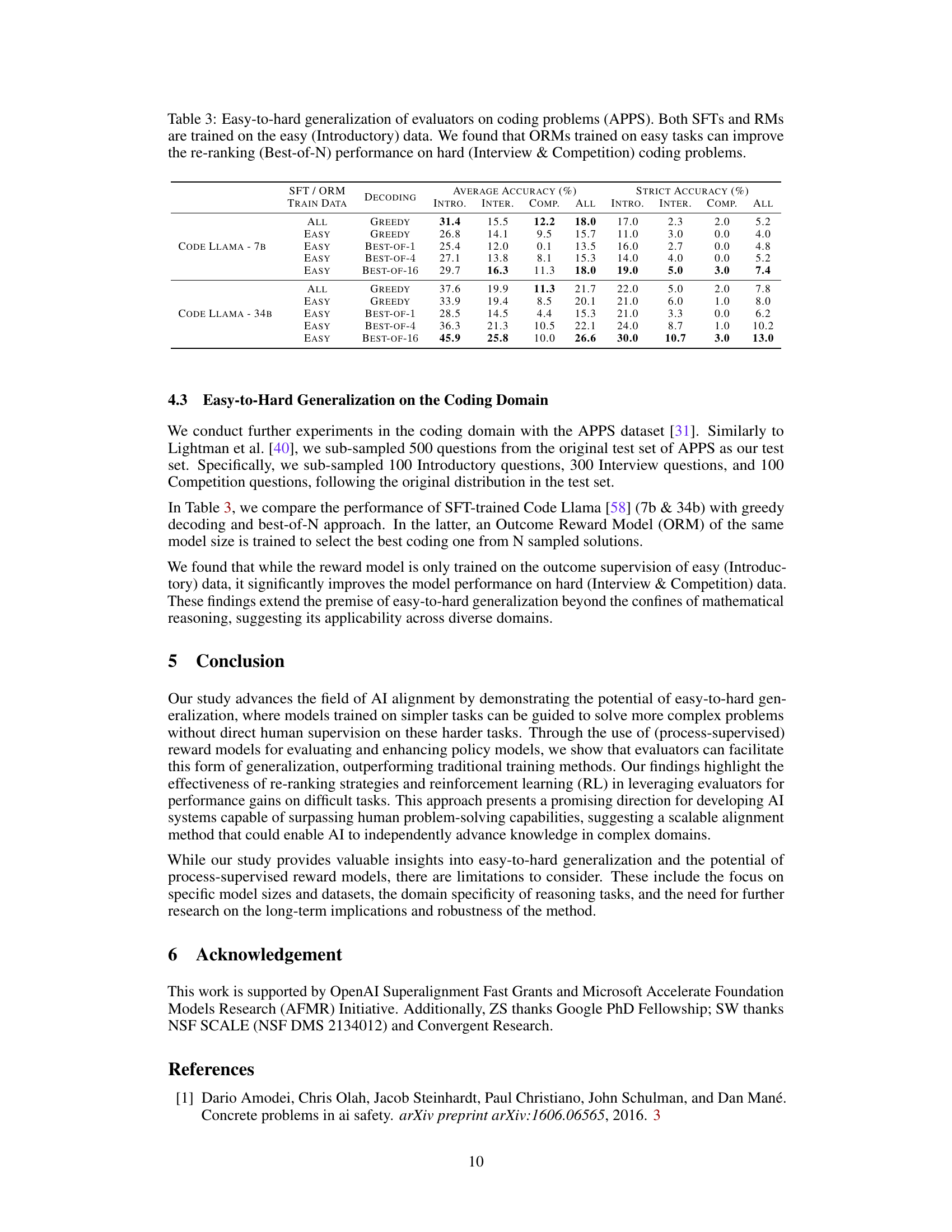

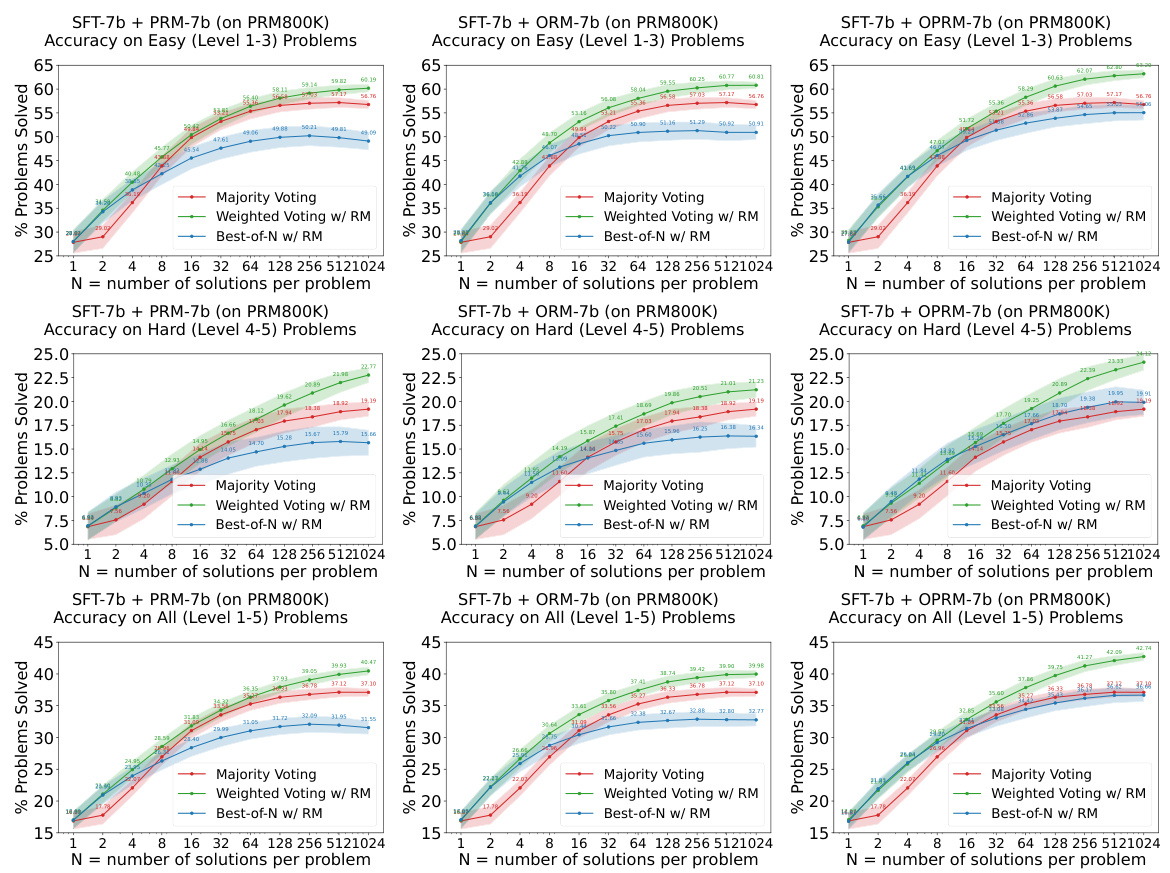

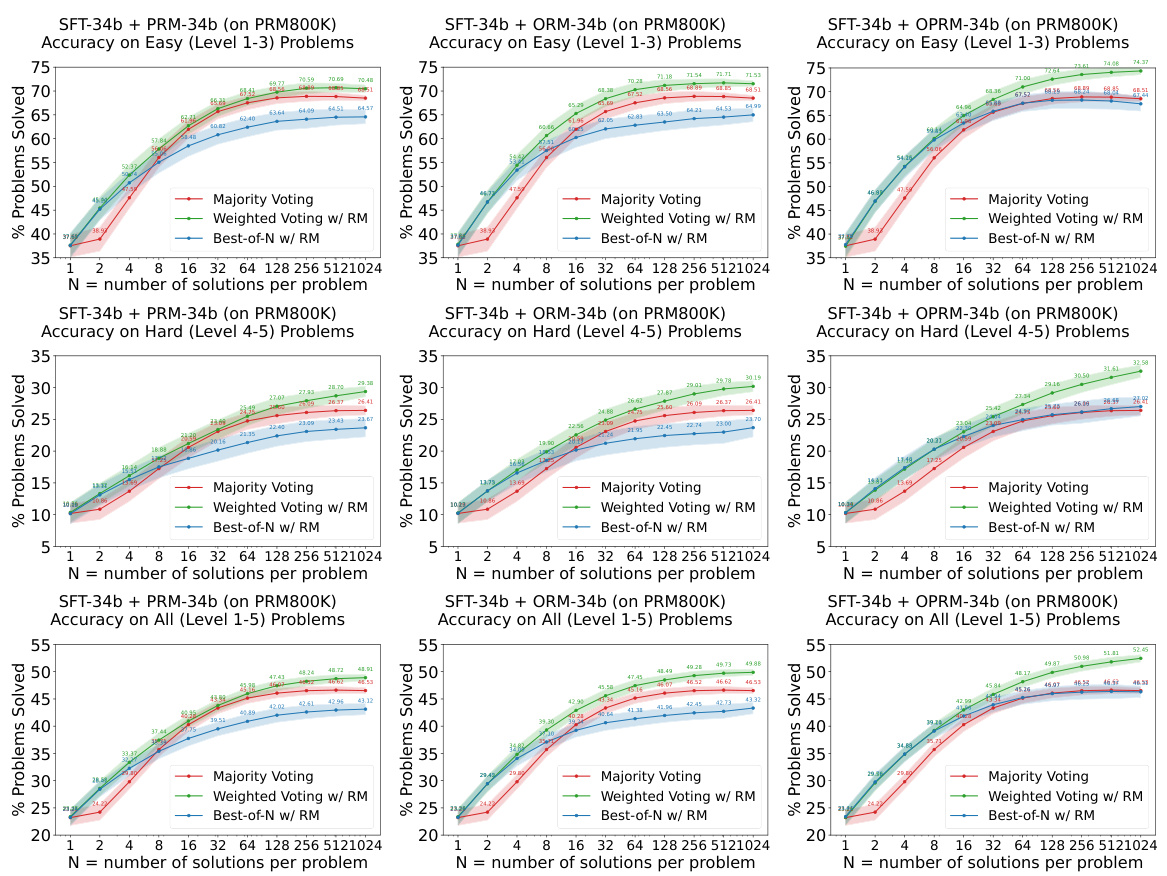

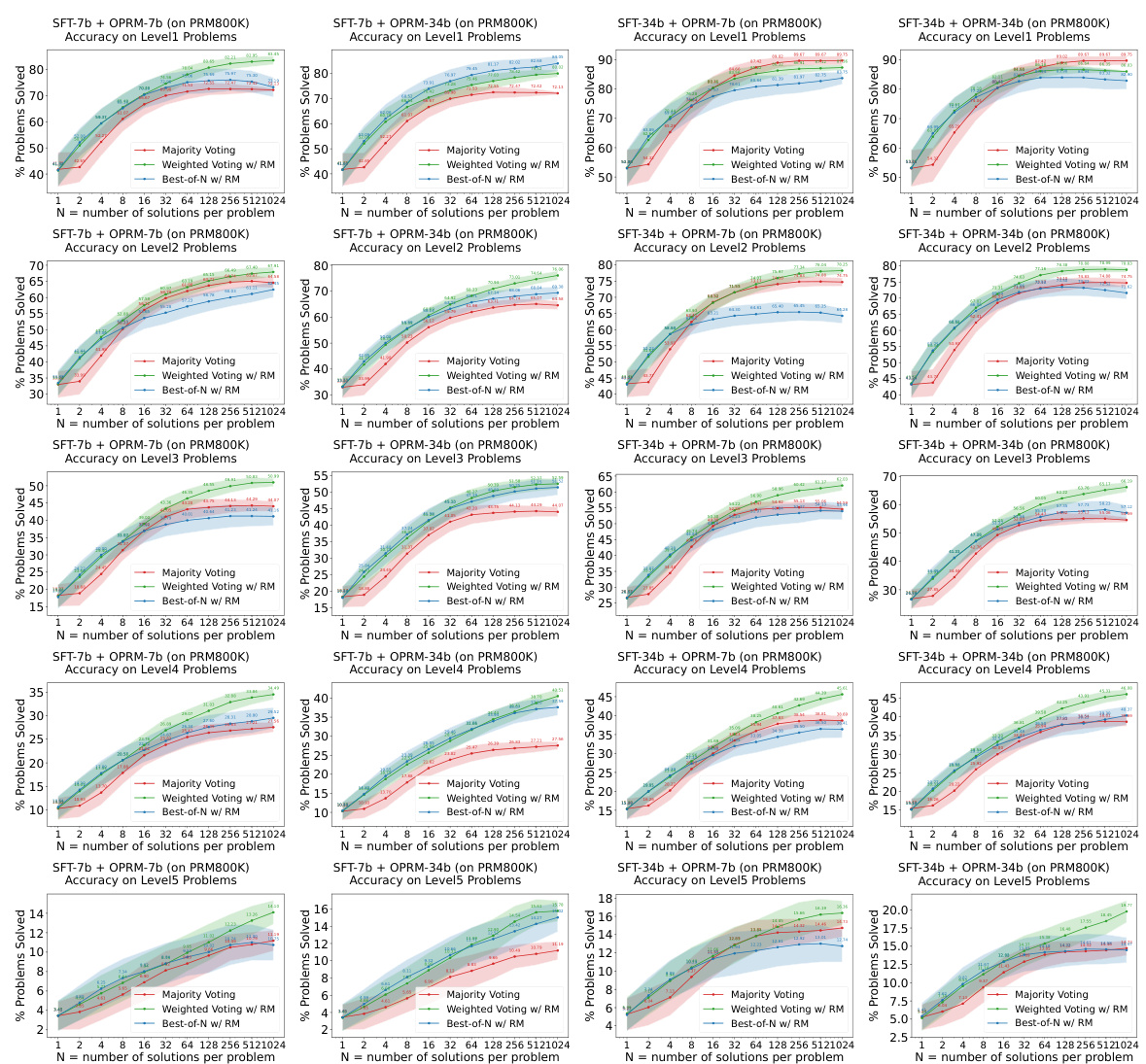

This figure shows the performance of different types of reward models (process reward models, outcome reward models, and outcome & process reward models) on various types of math problems (algebra, counting & probability, geometry, intermediate algebra, number theory, prealgebra, and precalculus). The results demonstrate the ability of the models to generalize from easier tasks to harder tasks, especially for certain problem types. It also compares the effectiveness of different re-ranking strategies (majority voting, weighted voting with reward model, and best-of-N with reward model).

This figure shows the results of experiments evaluating the easy-to-hard generalization ability of 7B and 34B evaluators (reward models). Both the SFTs and Reward Models (RMs) were trained only on easy tasks. The plots show the accuracy on easy (level 1-3), hard (level 4-5), and all (level 1-5) tasks using three different re-ranking strategies: Majority Voting, Weighted Voting with Reward Models, and Best-of-N with Reward Models. The shaded area represents the performance variance.

This figure illustrates the two-stage training process of the proposed method. First, an evaluator model is trained using process supervision or outcome supervision on easy tasks. This evaluator is then used to facilitate easy-to-hard generation in two ways: re-ranking or reinforcement learning (RL). The figure visually represents the flow of data and model training.

This figure illustrates the two-stage process of the proposed easy-to-hard generalization approach. First, an evaluator model (reward model) is trained using process supervision or outcome supervision on easier tasks. This trained evaluator is then used to score candidate solutions generated by a policy model (generator) on harder tasks, guiding the generator towards better performance through either reranking or reinforcement learning. The figure visually represents the training and evaluation stages for both the evaluator and the generator models.

This figure shows the performance of 7B and 34B evaluators on easy and hard tasks using different re-ranking methods. The evaluators (reward models) are trained only on easy tasks (levels 1-3). The results demonstrate that PRMs (Process-supervised Reward Models) trained on easy tasks can significantly improve the performance of re-ranking methods, such as weighted voting and best-of-N on hard tasks (levels 4-5). The shaded areas indicate the performance variance.

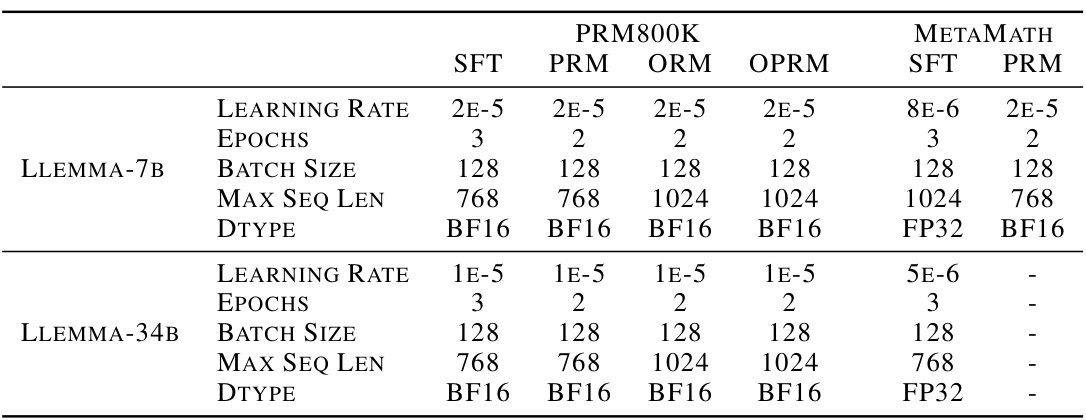

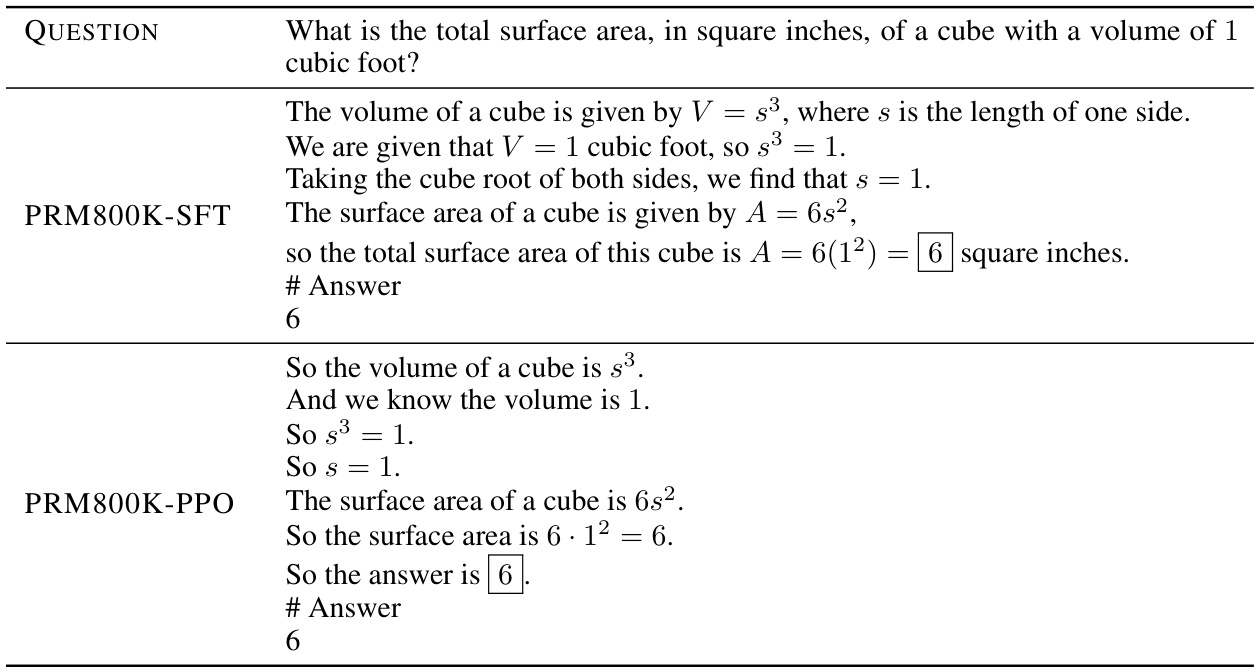

More on tables

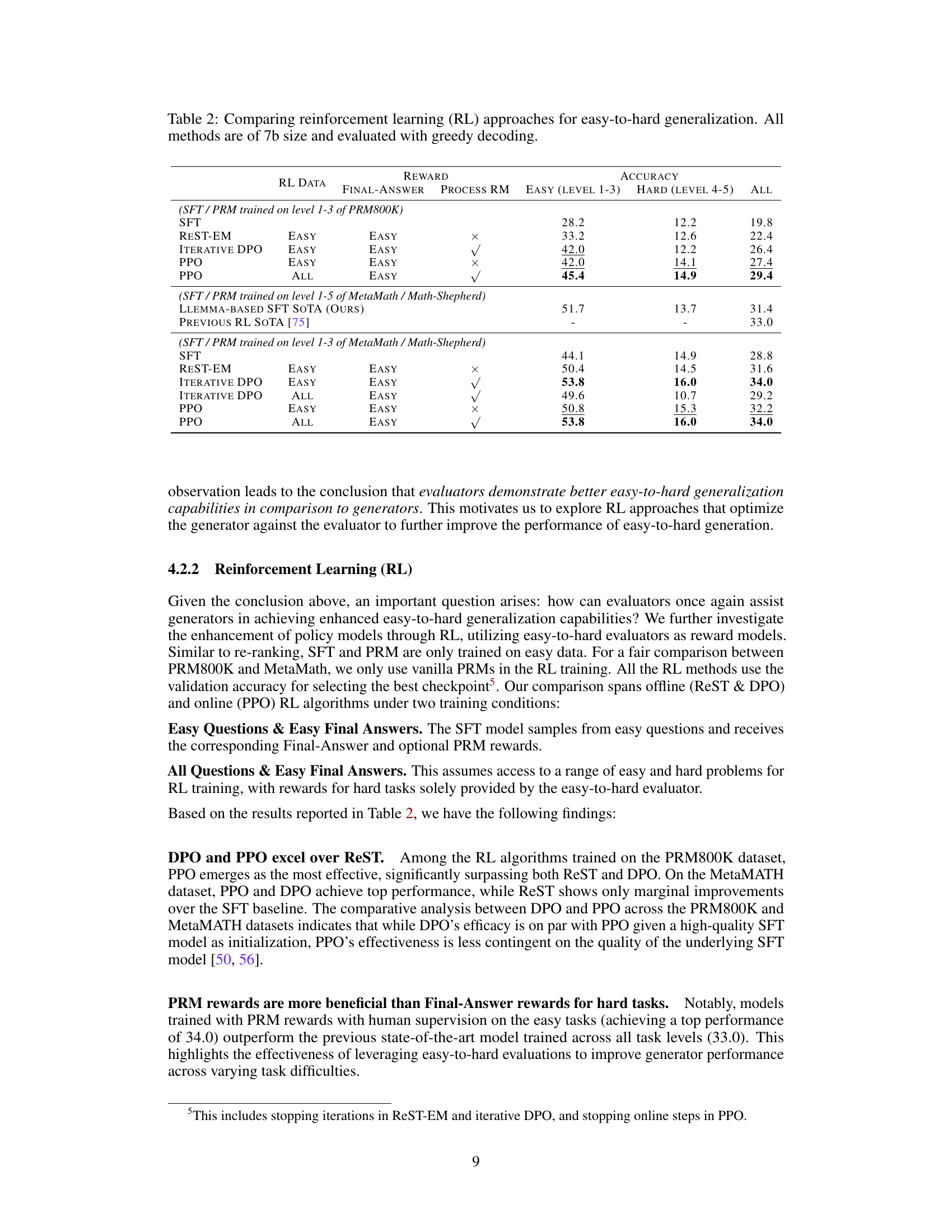

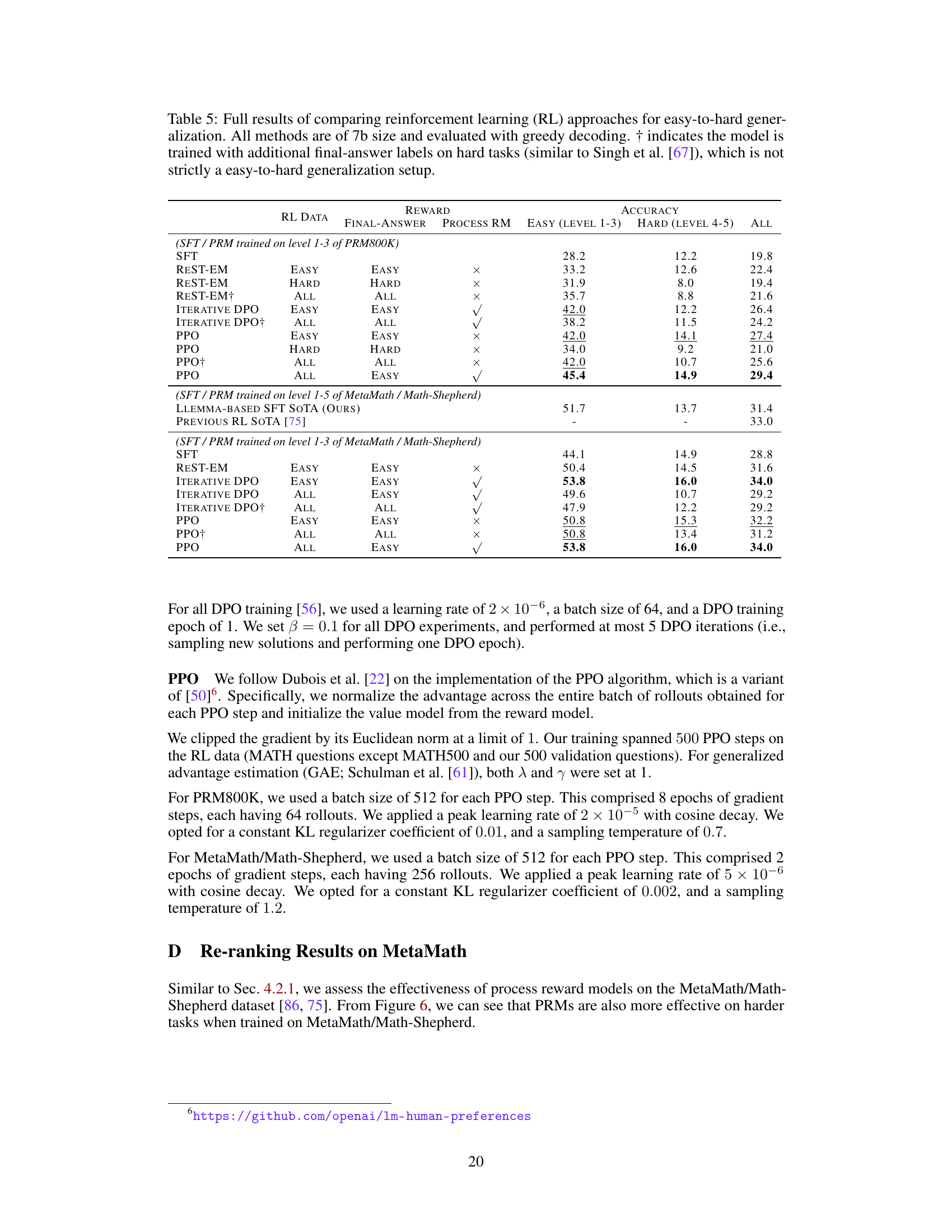

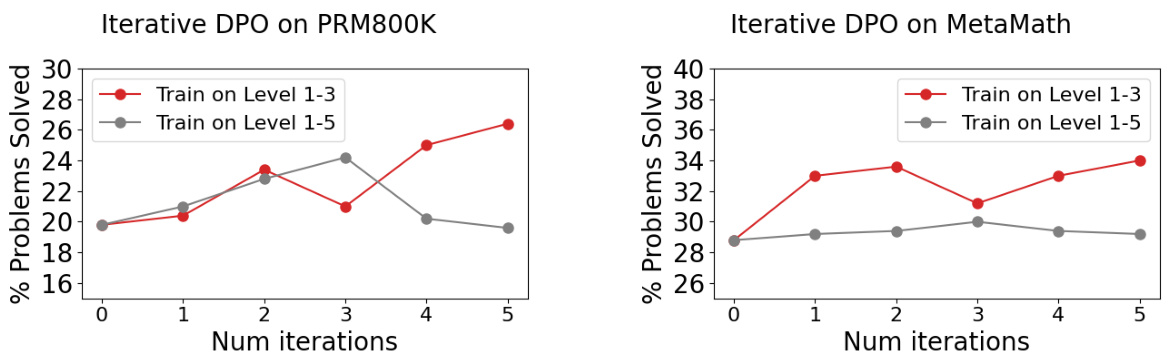

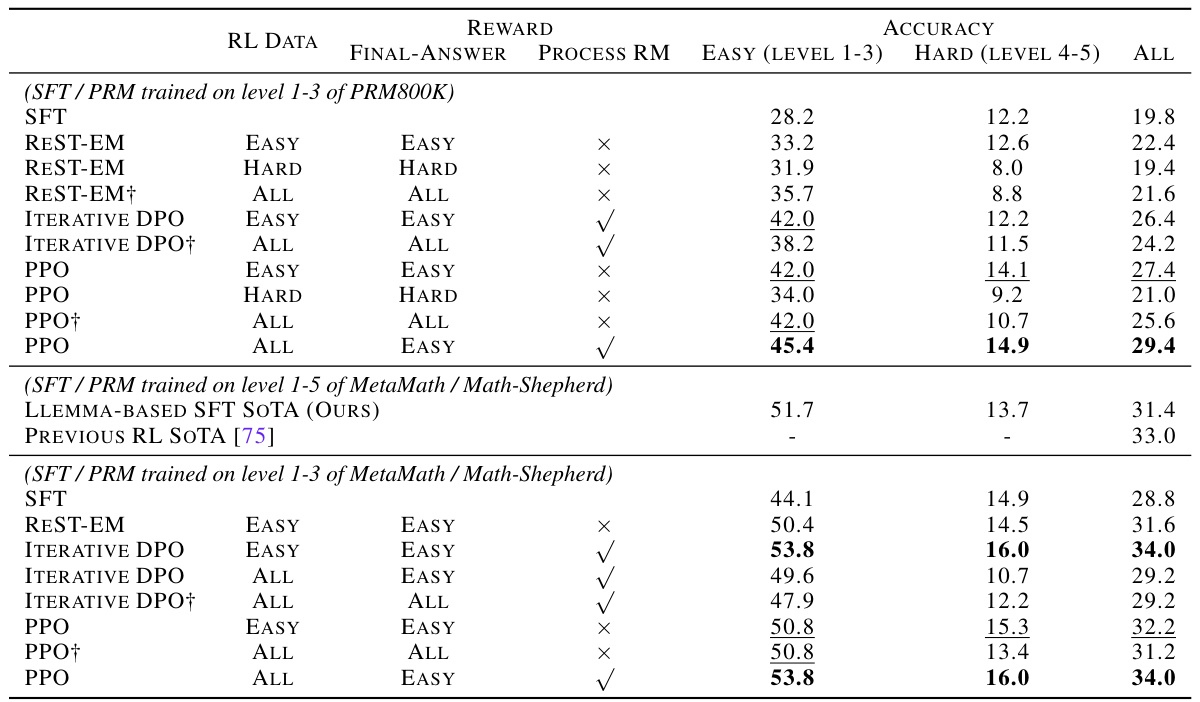

This table compares the performance of different reinforcement learning (RL) methods for easy-to-hard generalization. All models used have 7 billion parameters (7b) and utilize greedy decoding. The table shows the accuracy achieved on easy tasks (level 1-3), hard tasks (level 4-5), and overall accuracy across all task levels. Different RL approaches (REST-EM, Iterative DPO, PPO) are compared, trained with different data and reward model configurations (process-supervised reward models). The results highlight the impact of the evaluator (reward model) on the generalization capability of the generator (policy model) in hard tasks.

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating different methods for generating solutions to math problems. The methods are categorized as different types of generators trained on either easy or hard problems or a mixture. The performance of these models is compared across various decoding settings (greedy, majority voting, best-of-N). The table shows that supervised fine-tuning (SFT) generally outperforms in-context learning (ICL), and that models trained on both easy and hard data (Full SFT) perform best.

This table presents the results of different generator models trained on easy and hard tasks, comparing their performance using various decoding settings. PRM800K and METAMATH datasets are used for supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and in-context learning (ICL). The performance is evaluated on the MATH500 test set. The table highlights the performance differences between various training methods and decoding settings. It’s used to assess the easy-to-hard generalization ability of the generators.

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating different methods for generating solutions to mathematical problems, focusing on ’easy-to-hard’ generalization. It compares various generator models trained under different settings (supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and in-context learning (ICL)) using different datasets (PRM800K and METAMATH). The performance is measured by accuracy on the MATH500 test set using greedy decoding and majority voting with different numbers of samples (MAJ@16 and MAJ@256). The table helps to understand how different training data and methods affect the ability of the models to generalize from easy to hard problems.

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the easy-to-hard generalization capabilities of different generator models. It compares the performance of several methods for generating solutions to mathematical problems, varying both the decoding strategies used and the training data provided. The models were evaluated on the MATH500 dataset. PRM800K and METAMATH refer to different datasets used for supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and in-context learning (ICL), respectively.

The table presents a comparison of different methods for generating solutions to mathematical problems, focusing on the ability of models trained on easier problems to generalize to harder ones. It compares the performance of various generator models (In-context Learning and Supervised Fine-Tuning) under different decoding settings (greedy, majority voting, and best-of-N) on the MATH500 test set. The data used for training the models is indicated (PRM800K and METAMATH).

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing the performance of different methods for generating solutions to mathematical problems. The experiment tested several generator models under various decoding settings, including greedy decoding and majority voting. The training data used included PRM800K and METAMATH datasets. The performance is evaluated on the MATH500 test set.

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the easy-to-hard generalization performance of different language models used as generators. The models are evaluated under various decoding settings (greedy, majority voting, etc.). Two datasets, PRM800K and METAMATH, are used as training data, representing Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) and In-Context Learning (ICL) approaches. The performance is measured on the MATH500 test set, allowing comparison across different model architectures, training data, and decoding methods.

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the easy-to-hard generalization performance of different generator models. It compares various decoding settings (greedy, majority voting, etc.) applied to models trained using different datasets (PRM800K, Metamath) and methods (in-context learning, supervised fine-tuning). The results are shown in terms of accuracy on the MATH500 test set.

This table compares the performance of different language models (generators) on a mathematical reasoning task (MATH500). It shows how well models trained with different methods (supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and in-context learning (ICL)) on easier problems generalize to harder problems. The table also shows performance under various decoding settings (greedy, majority voting, etc.) and with different training datasets (PRM800K and METAMATH).

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating different methods for generating solutions to mathematical problems, specifically focusing on the ability of models to generalize from easier to harder problems. It compares the performance of several generator models under various decoding settings (greedy, majority voting at different numbers of samples), trained on either the full dataset (Full ICL/SFT) or only the easier portion (Easy-to-Hard ICL/SFT). The results are evaluated on the MATH500 test set, and the training data used (PRM800K or MetaMath) is specified. This table helps to demonstrate whether training on easier tasks leads to successful generalization to more complex ones and provides a benchmark for the different methods explored.

This table presents the results of different generator models on the MATH500 dataset. The models are evaluated under various decoding settings (greedy, majority voting, etc.). The training data used includes PRM800K and MetaMATH, representing supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and in-context learning (ICL), respectively. The table shows the performance of each generator model on different levels of the MATH500 test set. This helps to analyze how well different methods generalize from easier to harder tasks.

Full paper#