↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning models’ behaviors are largely influenced by their training datasets. While influence functions help understand single data points’ impact, identifying the most influential subsets of training data is complex. This study focused on the

Most Influential Subset Selection (MISS) problem, which aims at finding data subsets that, when removed, lead to the biggest change in the model’s output. The study found that existing MISS algorithms often fail due to the non-additive nature of the problem and influence function inaccuracies.

The authors demonstrate that adaptive greedy algorithms iteratively refine their sample selection based on the effects of already selected samples are much more effective. They prove theoretically and experimentally that this adaptive selection significantly outperforms static influence-based greedy methods in various scenarios, including linear and nonlinear models. This highlights the importance of considering adaptive approaches for a more accurate understanding of training data influence in machine learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals critical flaws in existing methods for identifying influential data subsets in machine learning models. It challenges the common assumption of additivity in influence functions and proposes an adaptive approach for more accurate results. This is vital for improving model interpretability, robustness, and fairness, which are major focuses in the current machine learning landscape.

Visual Insights#

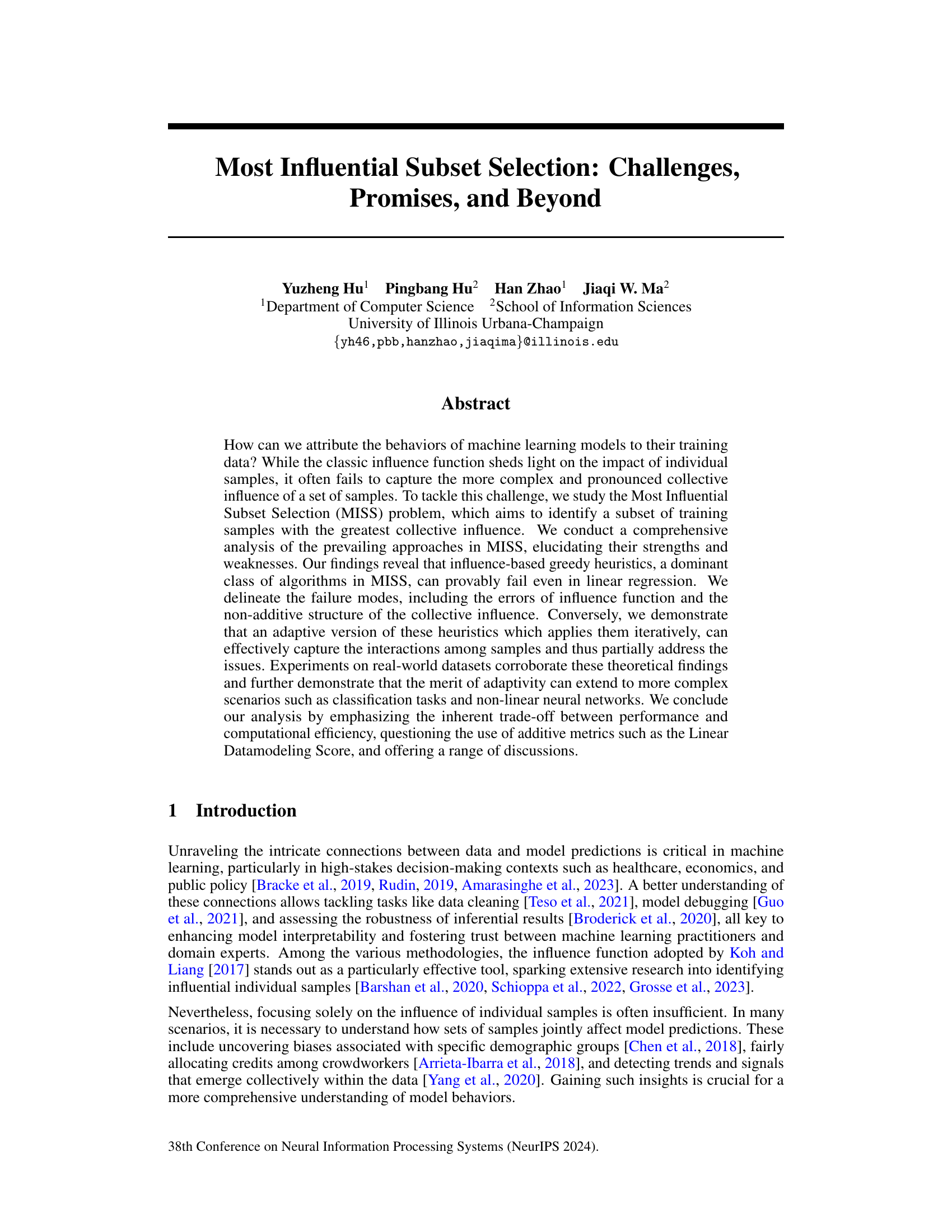

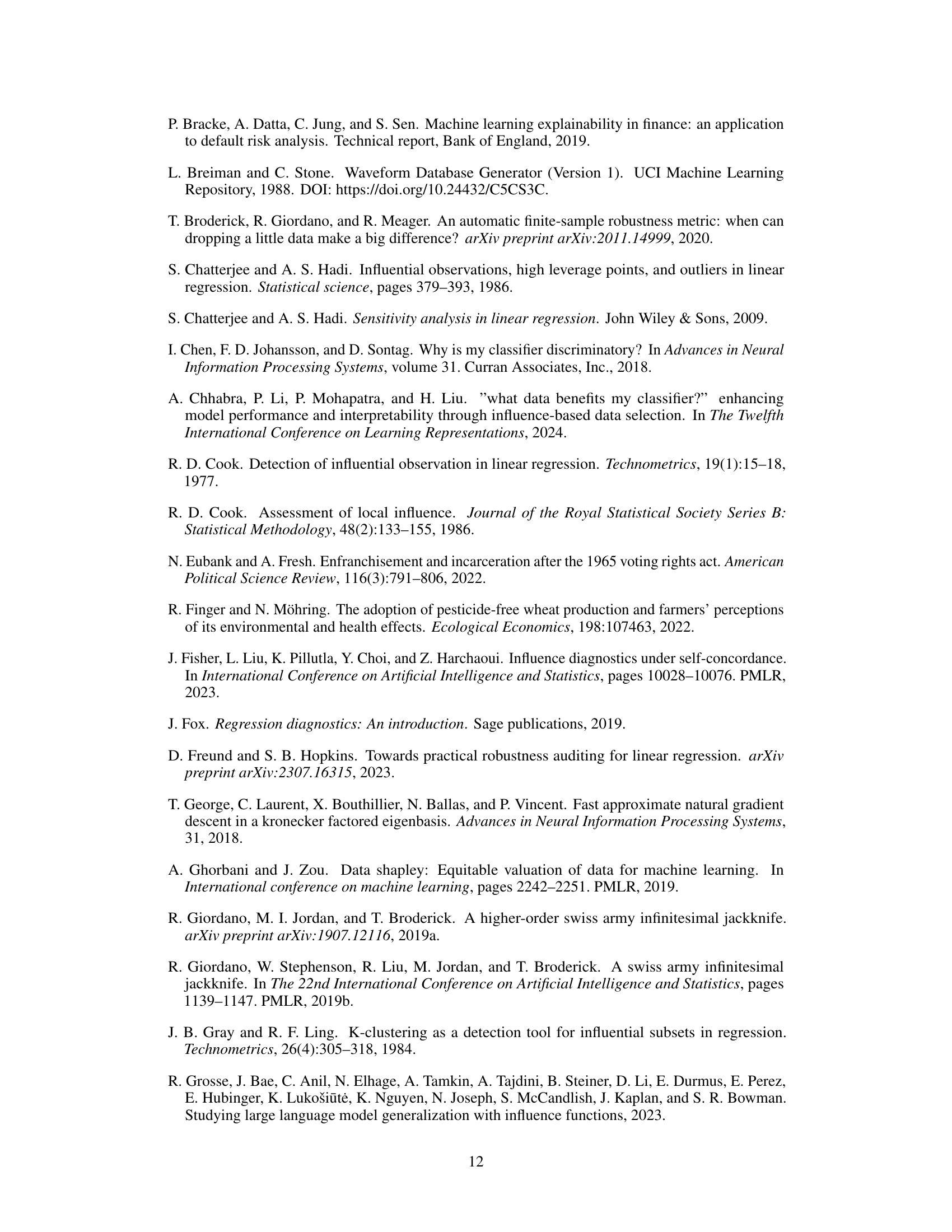

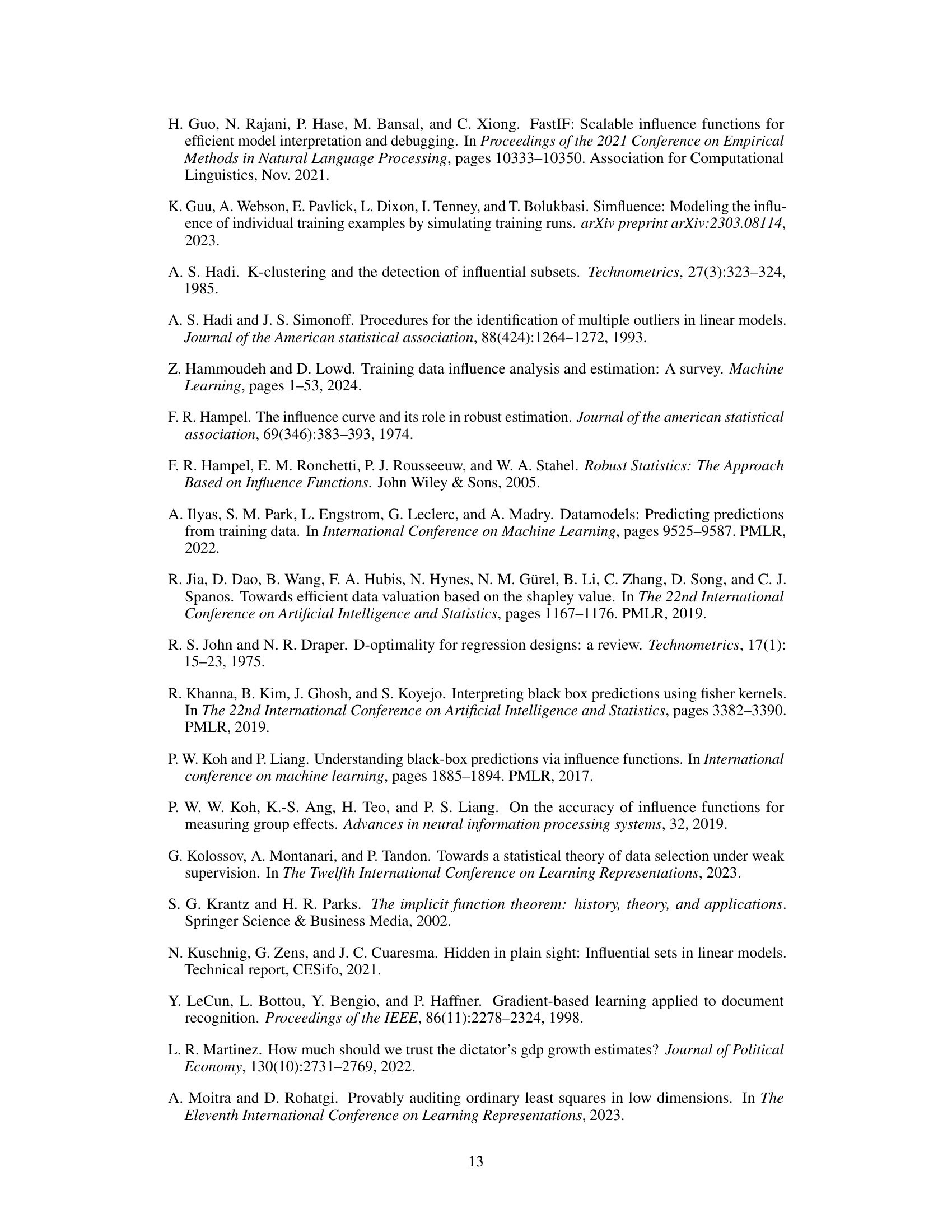

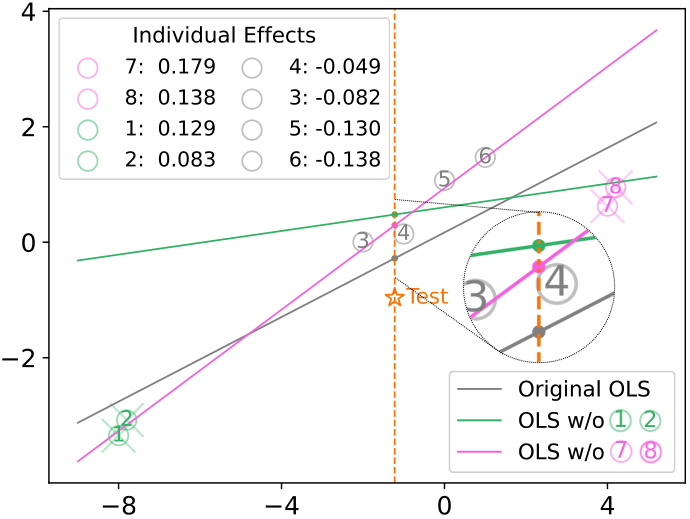

This figure illustrates how influence estimates, used in greedy heuristics for subset selection, can be inaccurate even in linear models. The plot shows influence estimates (calculated using the influence function) for several samples against the actual effect of removing each sample individually. The discrepancy between the influence estimate and the actual effect is particularly pronounced for samples with high leverage scores (points further from the origin). This inaccuracy leads to the failure of 1-MISS (finding the single most influential sample) because the algorithm may select samples with high influence estimates but low actual effects. The dotted vertical line indicates the test sample’s input. The three lines show the original OLS regression line, and the regression lines resulting after removing points 1 and 8 respectively.

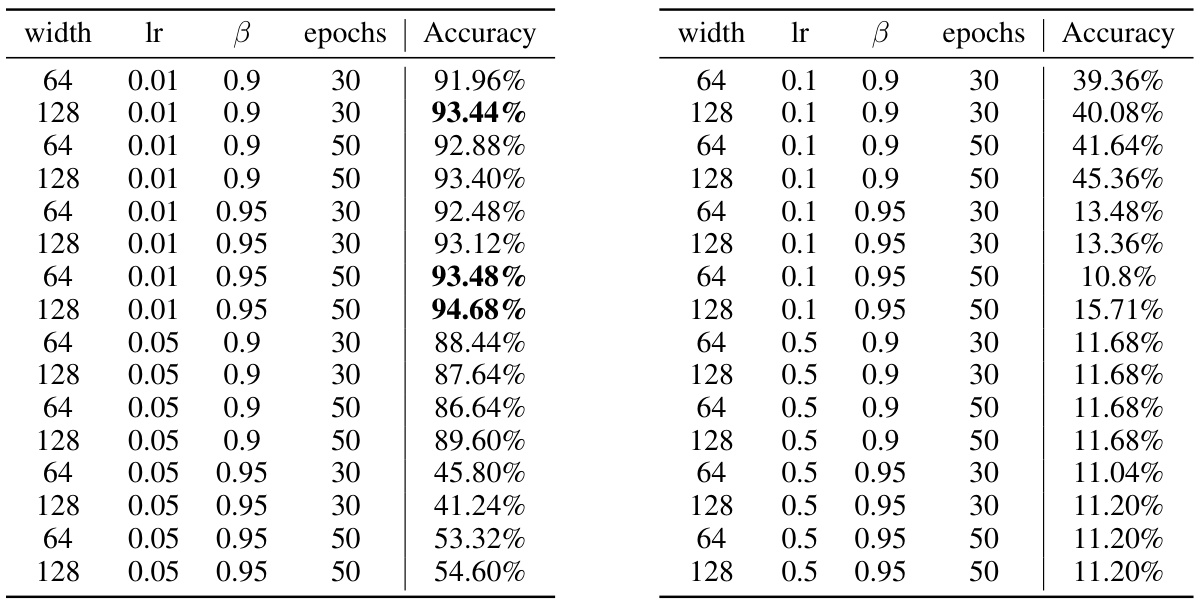

This table presents the results of a hyperparameter search for a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model trained on the MNIST dataset. It shows the accuracy achieved with different combinations of hyperparameters: the width (number of neurons) in the hidden layer, the learning rate (lr), the momentum (β), and the number of training epochs. The table helps determine the optimal hyperparameter settings for the model.

In-depth insights#

MISS Challenges#

The Most Influential Subset Selection (MISS) problem, while aiming to pinpoint the most impactful subset of training data, faces significant challenges. Influence-based greedy heuristics, a common approach, are shown to fail even in linear regression settings due to the non-additive nature of collective influence and inaccuracies in influence function estimations. This highlights the limitations of relying on additive metrics and individual influence scores, as these methods cannot capture the intricate interactions between samples. Adaptivity, through iteratively updating influence scores, offers a partial solution by better capturing these interactions. However, even adaptive methods face limitations, especially in more complex models. The trade-off between performance and computational efficiency remains a critical concern in MISS. The additive assumption, underlying many current approaches, is a major factor contributing to the challenges in tackling this problem effectively and accurately.

Greedy Heuristics#

Greedy heuristics, in the context of Most Influential Subset Selection (MISS), offer computationally efficient approximations to identify the most impactful subset of training samples. These methods typically involve iteratively selecting samples based on their individual influence scores, which are often estimated using influence functions. While computationally attractive, a critical limitation is their inability to effectively capture the complex, non-additive interactions between samples, leading to suboptimal subset selection. This failure stems from both the inherent limitations of influence functions and the assumption of additivity in collective influence. Adaptive versions of greedy heuristics, which iteratively update sample scores based on prior selections, offer a partial remedy by accounting for these interactions, thus leading to improved performance in more complex scenarios. However, even adaptive methods still grapple with the inherent trade-off between accuracy and computational cost and may not provide provable guarantees on solution optimality.

Adaptive MISS#

Adaptive Most Influential Subset Selection (MISS) tackles the limitations of traditional greedy MISS algorithms. These traditional methods often fail to capture the complex interactions among samples due to the non-additive nature of collective influence and inaccuracies in influence function estimations. Adaptive MISS addresses this by iteratively updating sample scores, incorporating the impact of previously selected samples. This dynamic approach allows for a more accurate representation of the collective influence and leads to improved subset selection, demonstrated through theoretical analysis and experiments on various datasets and model types. Adaptivity is shown to mitigate the issues of influence function errors and non-additive influence, achieving superior results compared to static greedy methods. However, the adaptive approach introduces a computational cost trade-off which needs further investigation. Future research should explore the theoretical guarantees and efficiency improvements of adaptive MISS and its application in complex settings such as non-linear models.

Non-Additive Effects#

The concept of “Non-Additive Effects” in the context of a research paper likely delves into scenarios where the combined impact of multiple factors or variables is not simply the sum of their individual effects. This non-linearity is crucial because additive models often fail to capture complex interactions and dependencies between elements. The research likely explores how these non-additive effects emerge, how they manifest in different systems (e.g., biological systems, social networks, or machine learning models), and how to account for them in modeling and analysis. Identifying and quantifying non-additive effects is essential for accurate predictions and a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms at play. The paper might introduce new methods for detecting and characterizing non-additive effects, and these methods might be crucial for improving the accuracy and reliability of models and predictions in various fields. The presence of non-additive effects necessitates a departure from simpler linear models, potentially towards more complex frameworks that incorporate interaction terms or non-linear relationships. Therefore, the paper will likely discuss various advanced statistical or computational techniques employed for unraveling such complex interactions and highlight their implications for interpreting model outputs.

Future of MISS#

The future of Most Influential Subset Selection (MISS) hinges on addressing its current limitations. Influence-based greedy heuristics, while computationally efficient, suffer from the non-additivity of collective influence and inaccuracies in influence function estimations, especially in complex models. Adaptive greedy algorithms offer improvements by iteratively updating sample scores, better capturing interactions, but lack theoretical guarantees beyond simple scenarios. Future research should focus on developing theoretically sound algorithms that can efficiently handle the non-additive nature of group influence. Exploring alternative metrics beyond the Linear Datamodeling Score, which assumes additivity, is crucial. Developing robust influence function estimators for complex models is also vital. Finally, addressing the inherent trade-off between computational efficiency and performance will be key to achieving more accurate and scalable MISS solutions. The development of algorithms with provable guarantees for complex tasks, potentially employing submodularity or other theoretical frameworks, remains a significant challenge.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the limitations of influence estimates in selecting the most influential sample in linear regression. It shows that samples with high leverage scores can be significantly underestimated by the influence function, leading to incorrect selection by algorithms like ZAMinfluence which rely on these estimates. The plot compares influence estimates with the actual effect of removing individual data points from a linear regression model. The discrepancy highlights the inaccuracy of influence functions in capturing the true impact of individual samples in MISS, especially for high-leverage points.

This figure illustrates how influence estimates, used in influence-based greedy heuristics for subset selection, can be inaccurate even in linear models. Specifically, it shows that the influence function underestimates the impact of high-leverage samples. The figure compares influence estimates with the actual effects of removing single data points. In this scenario, removing data point ⑧, which has the highest leverage score, causes the largest change in the prediction, but its influence is underestimated compared to other points. This demonstrates why using influence functions alone can lead to the failure of methods aiming for identifying the most influential subset of data points.

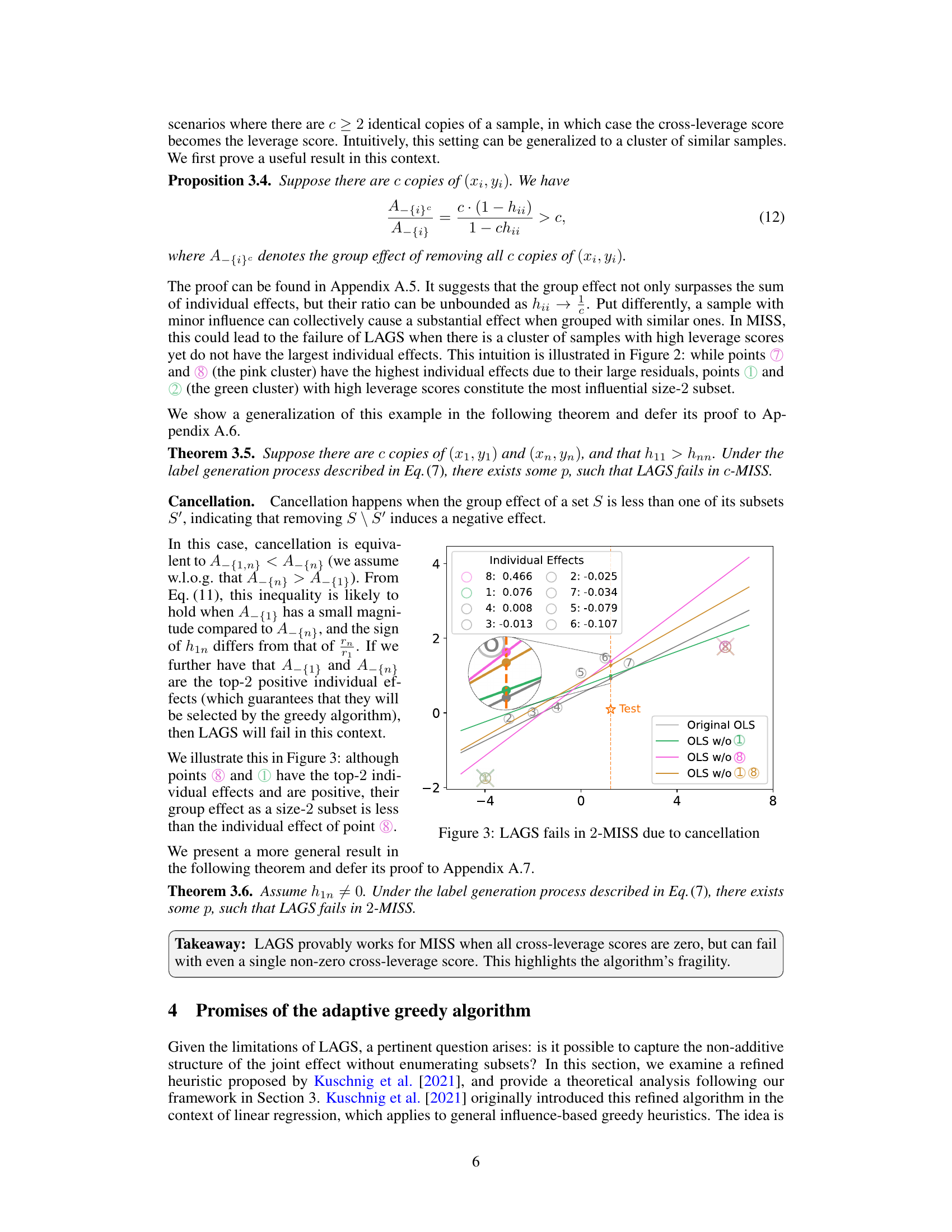

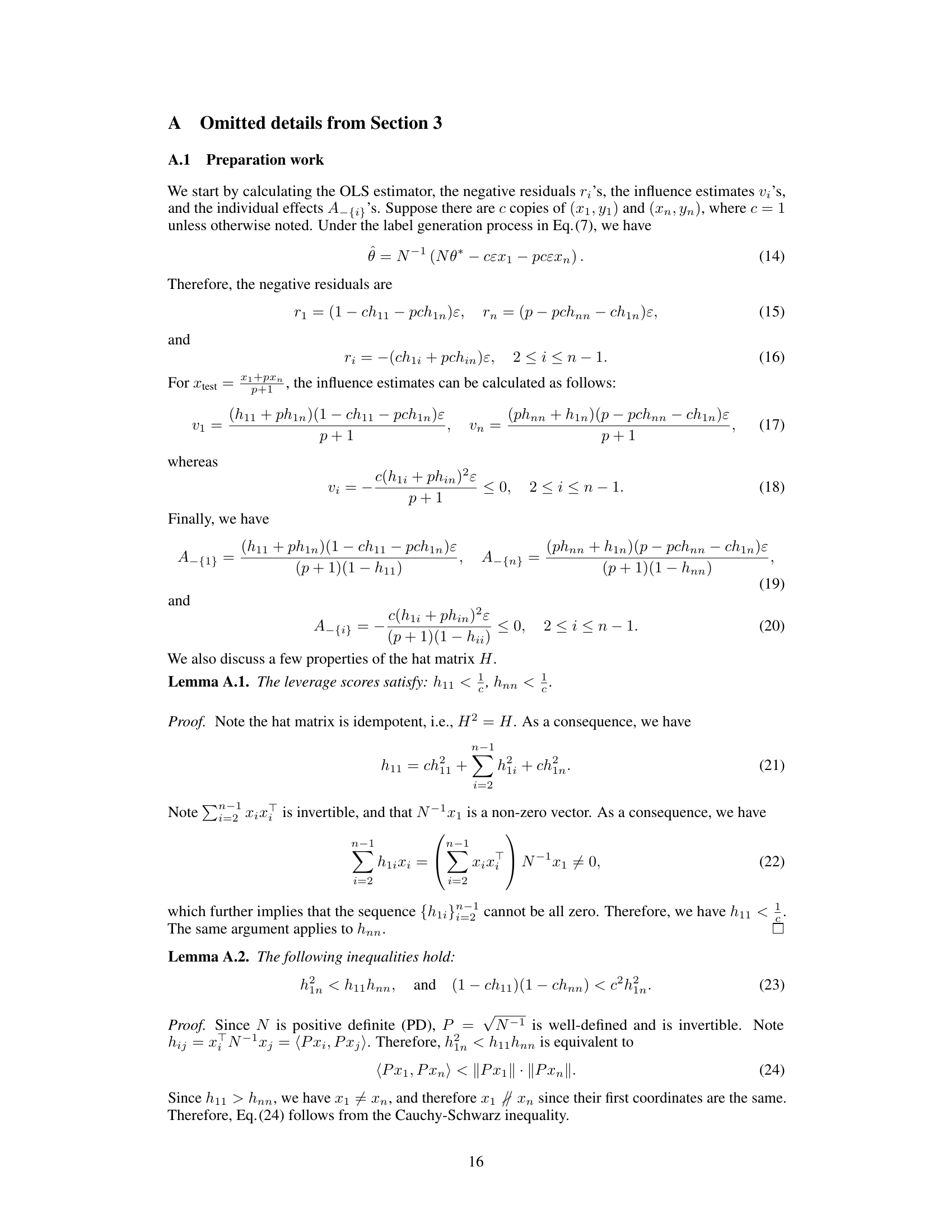

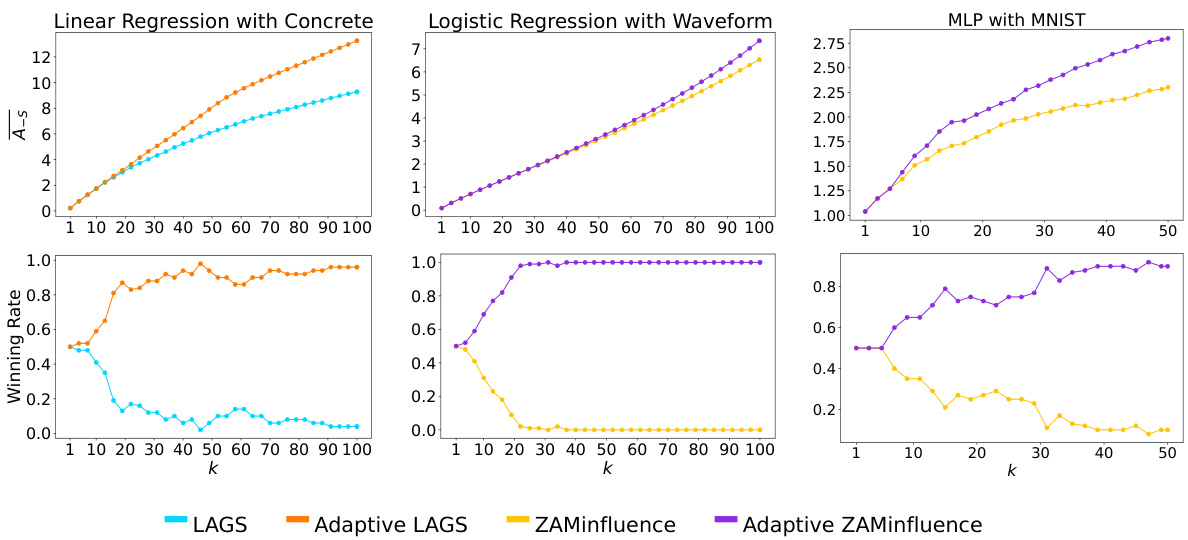

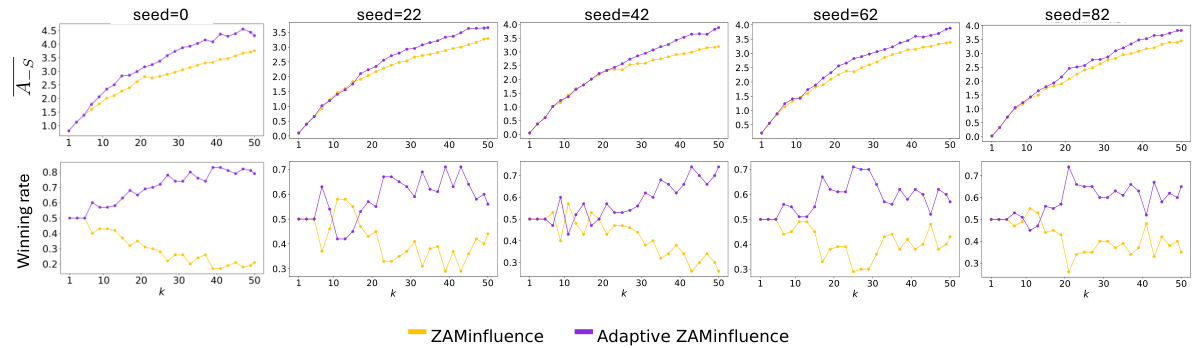

This figure compares the performance of greedy and adaptive greedy algorithms across three different machine learning tasks: linear regression, logistic regression, and multi-layer perceptron (MLP) classification. The top row shows the average actual effect (A_s), a measure of the algorithm’s ability to identify influential subsets. The bottom row displays the winning rate, indicating how often each algorithm achieved a larger actual effect than its counterpart. Across all tasks, the adaptive greedy algorithms consistently outperform the standard greedy algorithms in terms of both average actual effect and winning rate, particularly as the subset size (k) increases. This highlights the advantage of adaptively updating sample scores during subset selection, rather than using static scores.

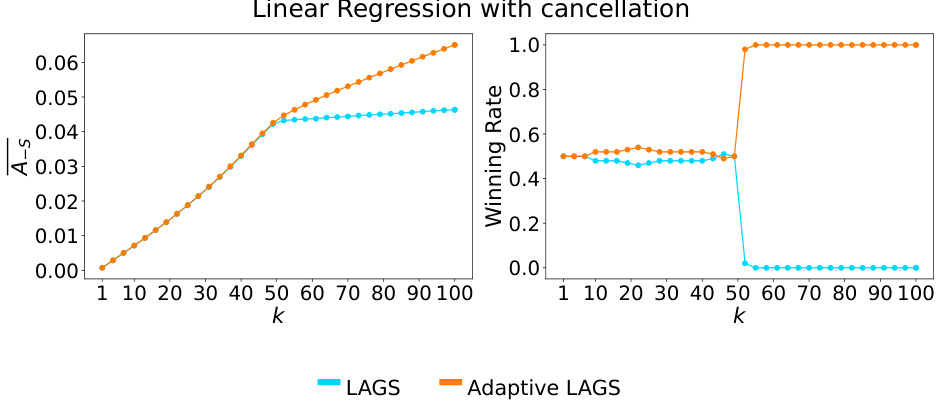

This figure shows a comparison of the performance of the greedy and adaptive greedy algorithms on a linear regression task with cancellation. The left panel displays the average actual effect (A_s), a measure of how much the model’s output changes when a subset of training data is removed. The right panel presents the winning rate, which shows the percentage of times each algorithm outperforms the other. As the size of the removed subset (k) increases, the average actual effect increases for both algorithms, but the adaptive greedy algorithm consistently achieves a larger effect. The winning rate plot clearly shows that the adaptive algorithm significantly outperforms the greedy algorithm as k grows beyond the cluster size.

This figure compares the performance of greedy and adaptive greedy algorithms for subset selection. The top row shows the average actual effect (A_s) achieved by each algorithm across different subset sizes (k). The bottom row presents the winning rate, indicating how often each algorithm outperforms the other. The results are shown for three different machine learning models: linear regression, logistic regression, and a multi-layer perceptron (MLP). The adaptive greedy algorithm consistently demonstrates a higher average actual effect and a higher winning rate, suggesting its superiority.

Full paper#