↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many biological systems exhibit collective motion, but deciphering the underlying interaction rules is complex, particularly in mixed-species systems with non-reciprocal forces. Existing system identification methods often struggle with these complexities, limited by computational costs or assumptions about interaction types. This paper addresses these issues by focusing on a novel deep learning framework for estimating two-body interactions.

This framework cleverly combines Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to model complex interactions between entities and Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (neural ODEs) to learn the system dynamics. The method’s efficacy was demonstrated through numerical experiments, including a toy model for parameter tuning and a more realistic model mimicking cellular slime mold behavior. The results showed accurate estimations of two-body interactions, even when these forces are non-reciprocal, thereby successfully replicating individual and collective behaviors.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers studying collective motion because it introduces a novel method for estimating two-body interactions in mixed-species systems. It offers a significant advancement over existing techniques by effectively handling complex, non-reciprocal interactions between different entities, thus opening new avenues for analyzing emergent properties in complex biological systems. The proposed deep learning framework combines the strengths of GNNs and neural ODEs to model these interactions accurately and efficiently. This research could facilitate a deeper understanding of collective behavior in various biological contexts and inspire the development of novel AI models for similar complex systems.

Visual Insights#

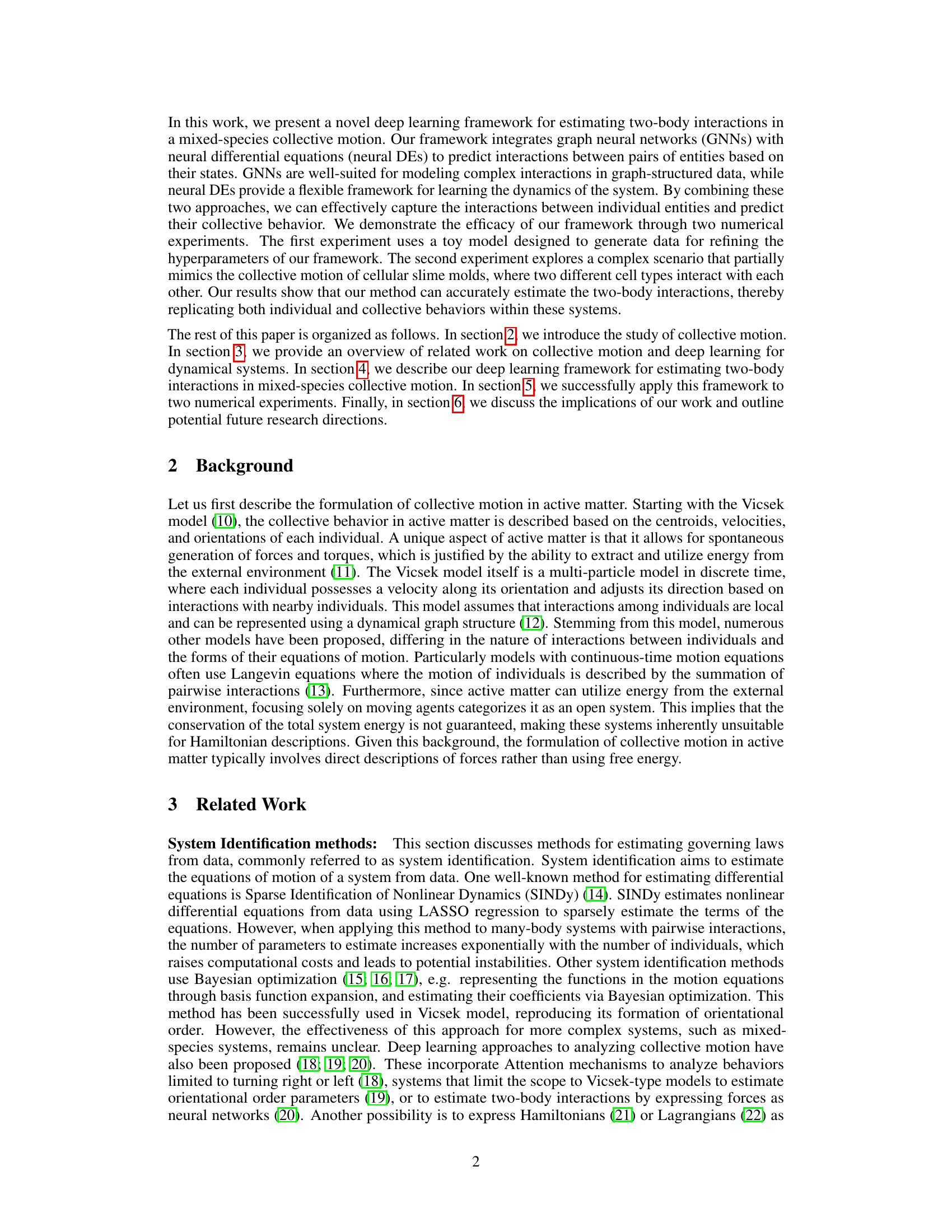

This figure shows the workflow of integrating Graph Neural Networks (GNN) and neural Ordinary Differential Equations (neural ODEs) to estimate the interactions between entities in collective motion. The initial state is fed into a neural ODE, which interacts with a GNN at each time step. The GNN defines the edges based on a distance function and calculates interactions between connected entities (F²) and self-generated forces (F¹). These forces are fed back into the neural ODE, allowing it to update the state and repeat the process until the end of the time series. This iterative process effectively estimates the two-body interactions by learning the dynamics of individual entities and their interactions within the collective system.

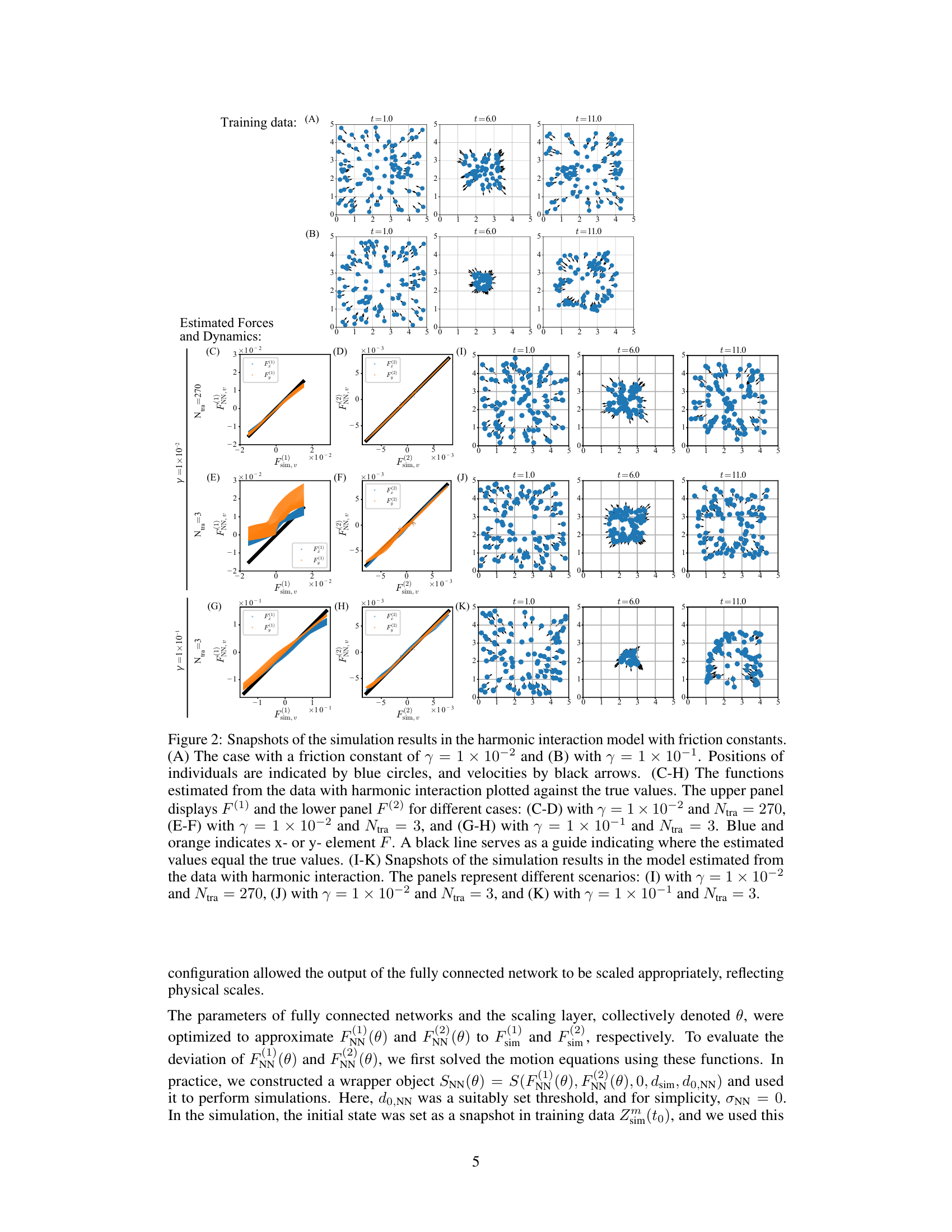

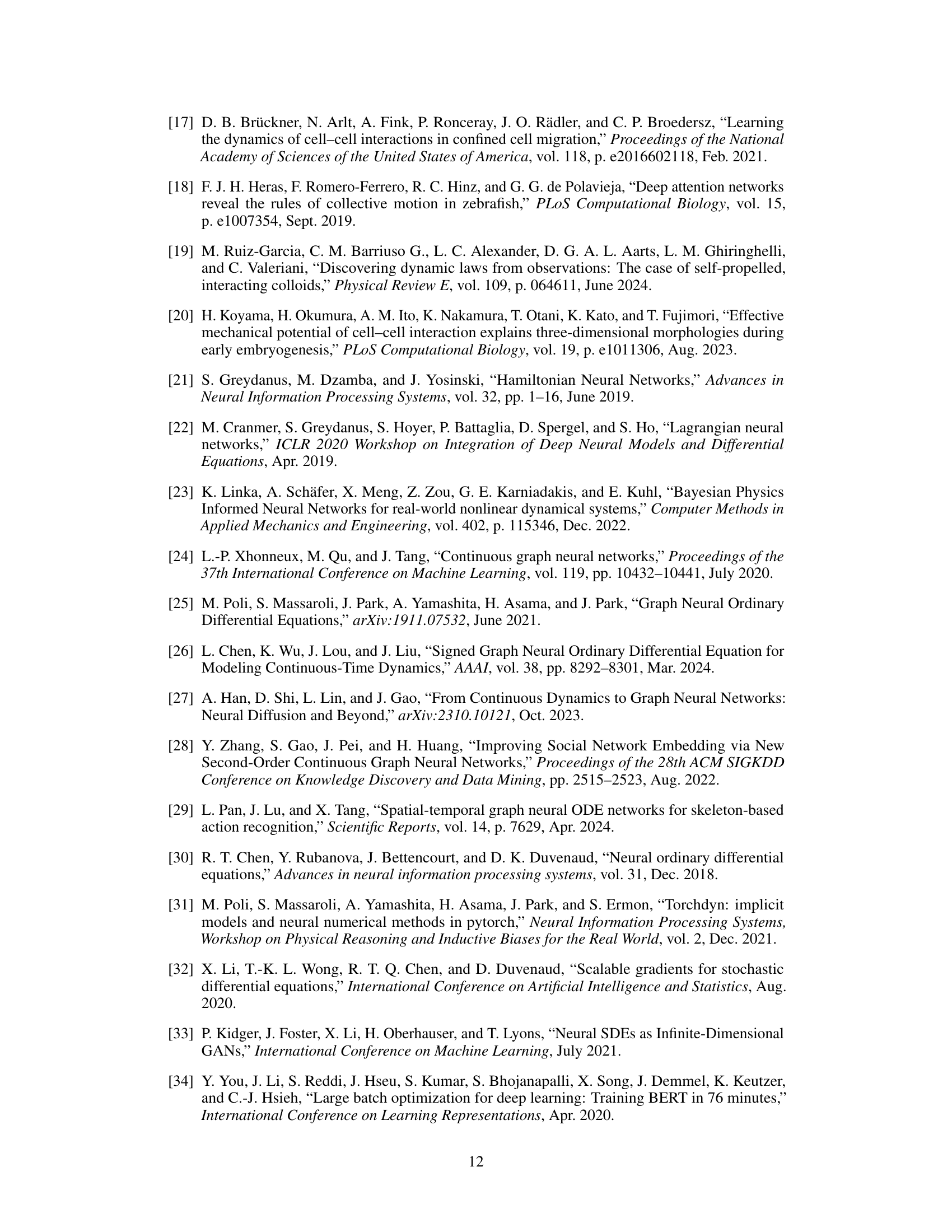

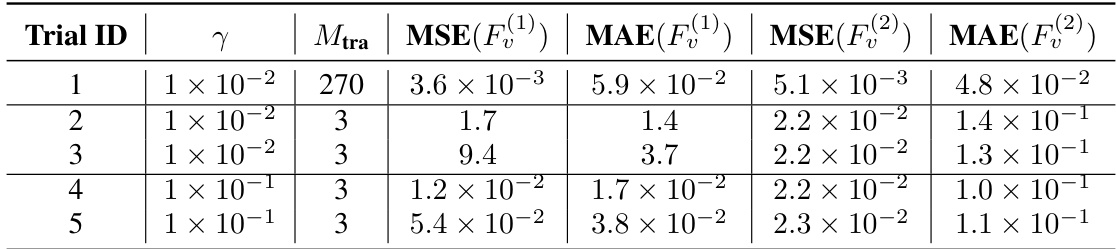

This table presents the normalized Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for the estimation of self-propulsion forces (F(1)) and interaction forces (F(2)) in a harmonic interaction model. The results are separated into five trials, each with different friction constants (γ) and training data sizes (M_tra). The table quantifies the accuracy of the model’s estimations of these forces in different simulation scenarios. Lower values indicate higher accuracy.

In-depth insights#

Collective Motion#

The concept of collective motion, as discussed in the provided research paper, centers on the coordinated movement of multiple entities within biological systems. This phenomenon is prevalent across various scales, from flocks of birds and schools of fish to cellular slime molds and human crowds. The research highlights the crucial role of inter-entity interactions in shaping collective behavior, emphasizing the need to understand the underlying equations of motion governing these dynamics. The paper particularly focuses on mixed-species collective motion, where the interactions between different types of entities become more complex and challenging to model. This necessitates advanced modeling techniques that can effectively capture non-reciprocal interactions, leading to the proposed use of graph neural networks and neural differential equations to estimate the governing laws from observed trajectories. Understanding these interactions is fundamental to comprehending the emergent properties and collective behaviors within these complex systems.

GNN-Neural ODEs#

The proposed framework cleverly integrates Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) with Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs) to model complex interactions within collective motion systems. GNNs excel at capturing the relationships between interacting entities, represented as a graph, enabling the framework to effectively handle mixed-species interactions where the relationships between individuals may be dynamic and not fully known. The use of Neural ODEs allows the system to learn the continuous-time dynamics of these interactions, providing a more realistic model compared to discrete-time approaches. This combined approach shows significant promise for analyzing intricate collective dynamics, especially in systems with non-reciprocal and complex interactions between multiple agents. The strength lies in its capacity to learn both individual and collective behaviors directly from observed trajectories, overcoming challenges inherent in traditional modeling methodologies. This is particularly noteworthy because it does not require predefining interaction forms or making strong assumptions about the underlying dynamics.

Mixed-Species#

The concept of ‘Mixed-Species’ in collective motion research, as explored in the provided PDF, focuses on understanding the dynamics of systems where multiple types of biological agents (e.g., cells of different types, or different species of animals) interact. The key challenge lies in disentangling the individual behaviors and interactions between species to reveal the governing rules of the collective behavior. The research likely investigates how differences in size, shape, motility, and response mechanisms between species influence both individual trajectories and overall collective patterns. A central theme is likely the non-reciprocal nature of interactions; that is, how the influence of one species on another is not necessarily symmetrical. This necessitates sophisticated modeling approaches, potentially involving graph neural networks and neural ODEs to handle the complexity of interactions and capture non-linear behaviors. The goal is likely to develop predictive models that can accurately capture both individual and collective behaviors, thus offering insights into the emergent properties of such mixed-species systems.

Model Estimation#

In the realm of collective motion modeling, model estimation is a critical process. It involves using observed trajectory data to infer the underlying rules governing agent interactions. This often necessitates employing sophisticated machine learning techniques, such as graph neural networks (GNNs) coupled with neural ordinary differential equations (NODEs), to estimate the complex, often non-reciprocal, forces between individuals. A key challenge lies in handling the high dimensionality of the data and the need to identify parameters that accurately reflect both individual and collective behavior. Successful model estimation allows for the prediction of future movement, the synthesis of novel collective dynamics, and a deeper understanding of the biological principles driving collective motion in diverse systems. The accuracy of these estimations heavily depends on the quality of the data, the chosen model’s complexity, and the efficacy of the chosen learning algorithm. Robustness to noise and outliers is also essential, particularly in real-world biological datasets. Furthermore, the interpretability of the estimated model remains a crucial aspect, allowing researchers to relate the model parameters to real-world biological mechanisms.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework to handle more complex interactions, such as those involving more than two bodies or incorporating higher-order interactions, would significantly enhance its applicability to real-world scenarios. Investigating the impact of noise and stochasticity on the accuracy and robustness of the model is also crucial. Developing efficient methods for handling large-scale datasets is essential for applying this approach to large biological systems. Further research should focus on improving the interpretability of the learned models and developing techniques to extract biologically meaningful insights. Finally, applying the framework to diverse biological systems and experimentally validating the predictions generated by the model will solidify its utility and broaden its impact on the field of collective motion research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

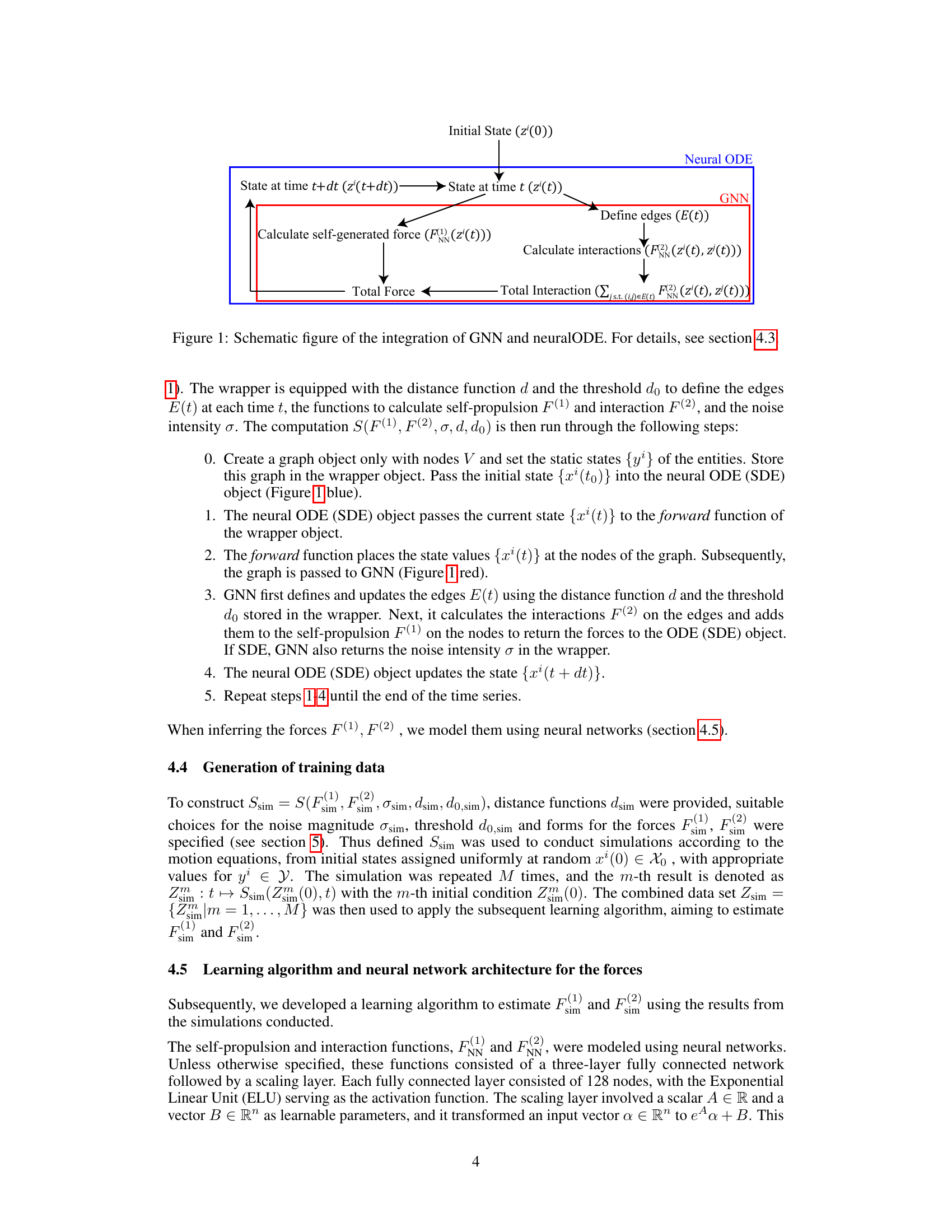

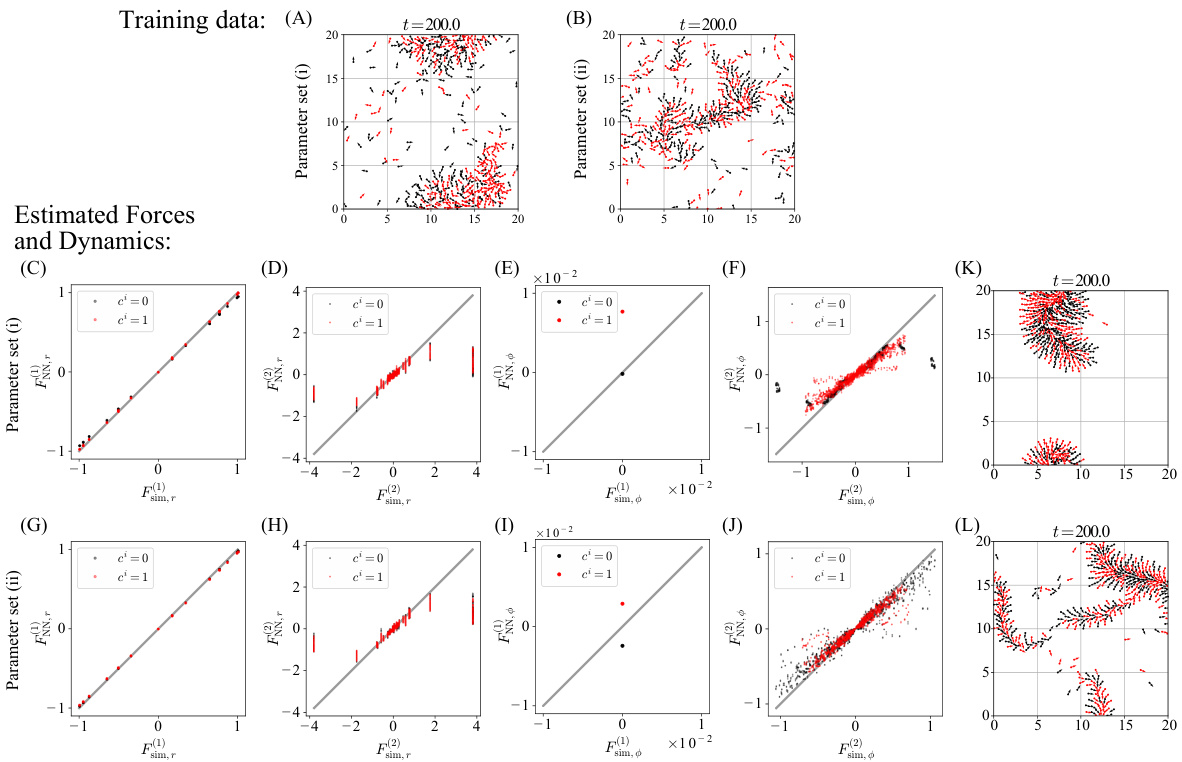

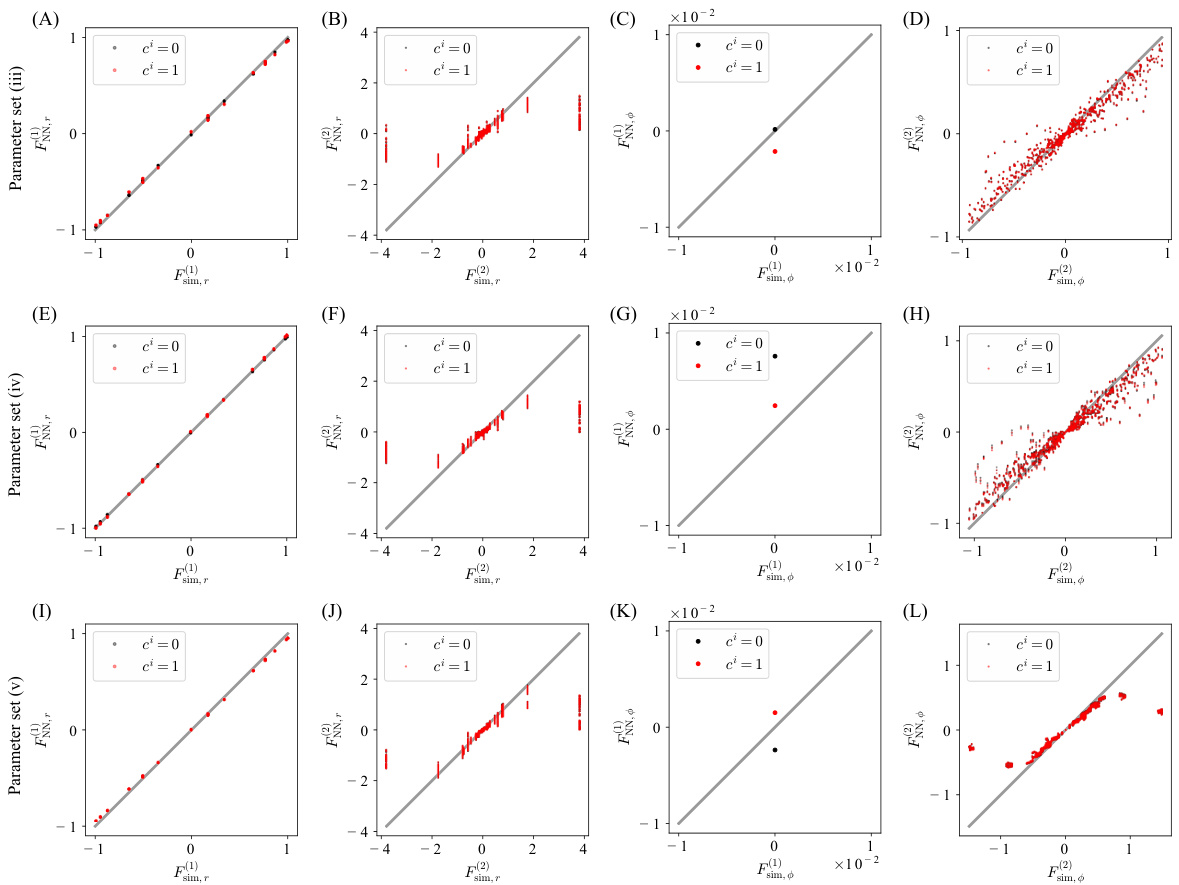

Figure 2 shows simulation results for a toy model with harmonic interactions and friction. It compares the estimated interaction forces (F(1) and F(2)) against the true values under different conditions (friction coefficient and training dataset size). The figure also displays snapshots of the particle positions and velocities for both the original simulation and the model estimations.

Figure 2 presents simulation results for a toy model of particles interacting harmonically with friction. It shows the positions and velocities of particles (A, B), and compares estimated and true forces (C-H). The impact of different friction coefficients (γ) and dataset sizes (Ntra) on the accuracy of force estimation is visualized. Finally, it displays simulations using the estimated forces (I-K).

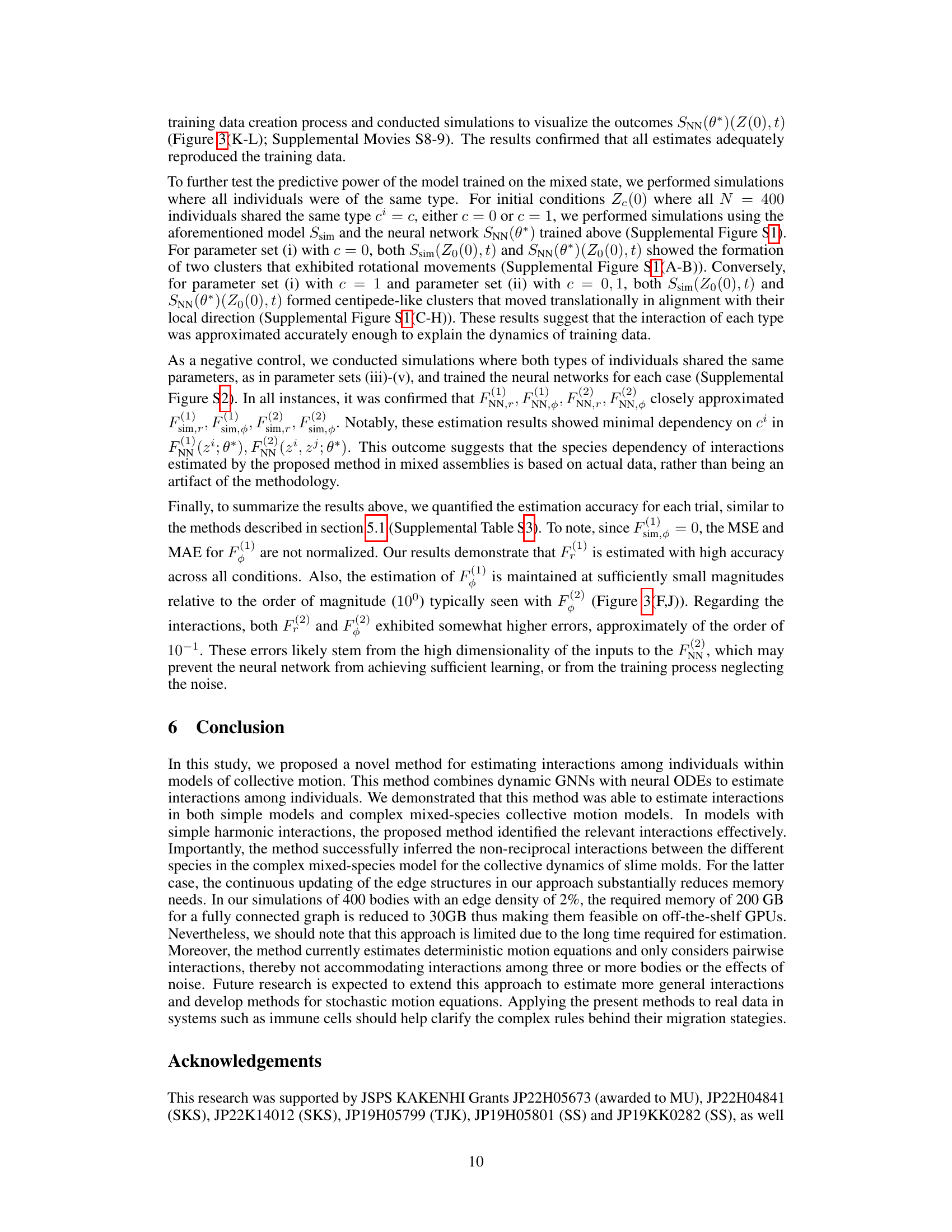

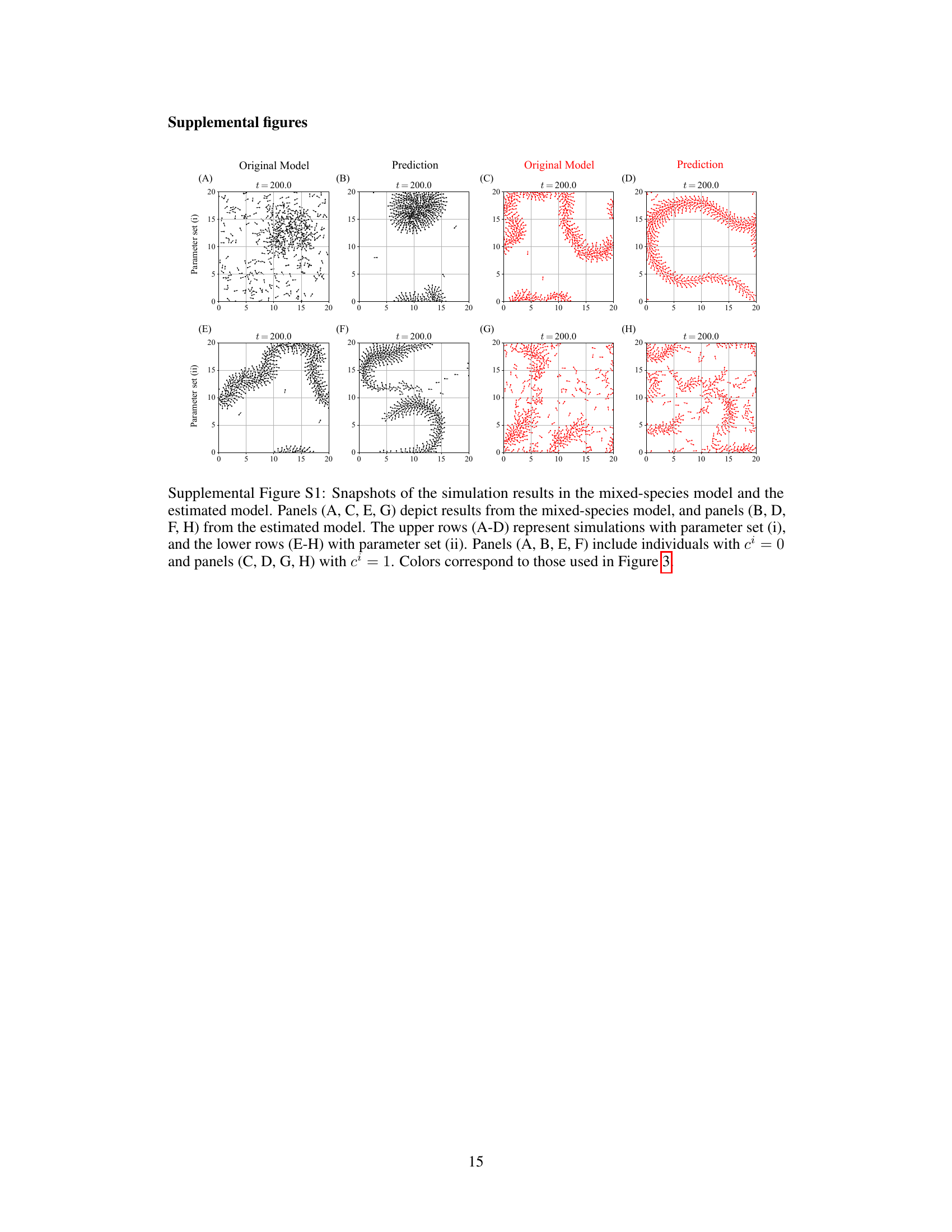

Figure 3 shows simulation results for a mixed-species collective motion model. Panel A and B show snapshots of the training data with two different parameter sets. Panels C to J compare the estimated functions against true values for these sets. Panels K and L illustrate snapshots of simulations using the estimated models.

Figure 2 shows the results of simulations using a toy model to test the proposed method. Panel A and B show the positions and velocities of particles in the simulation. Panels C-H show the comparison of estimated and actual forces. Panels I-K show snapshots of simulations using the model estimated from the data.

More on tables

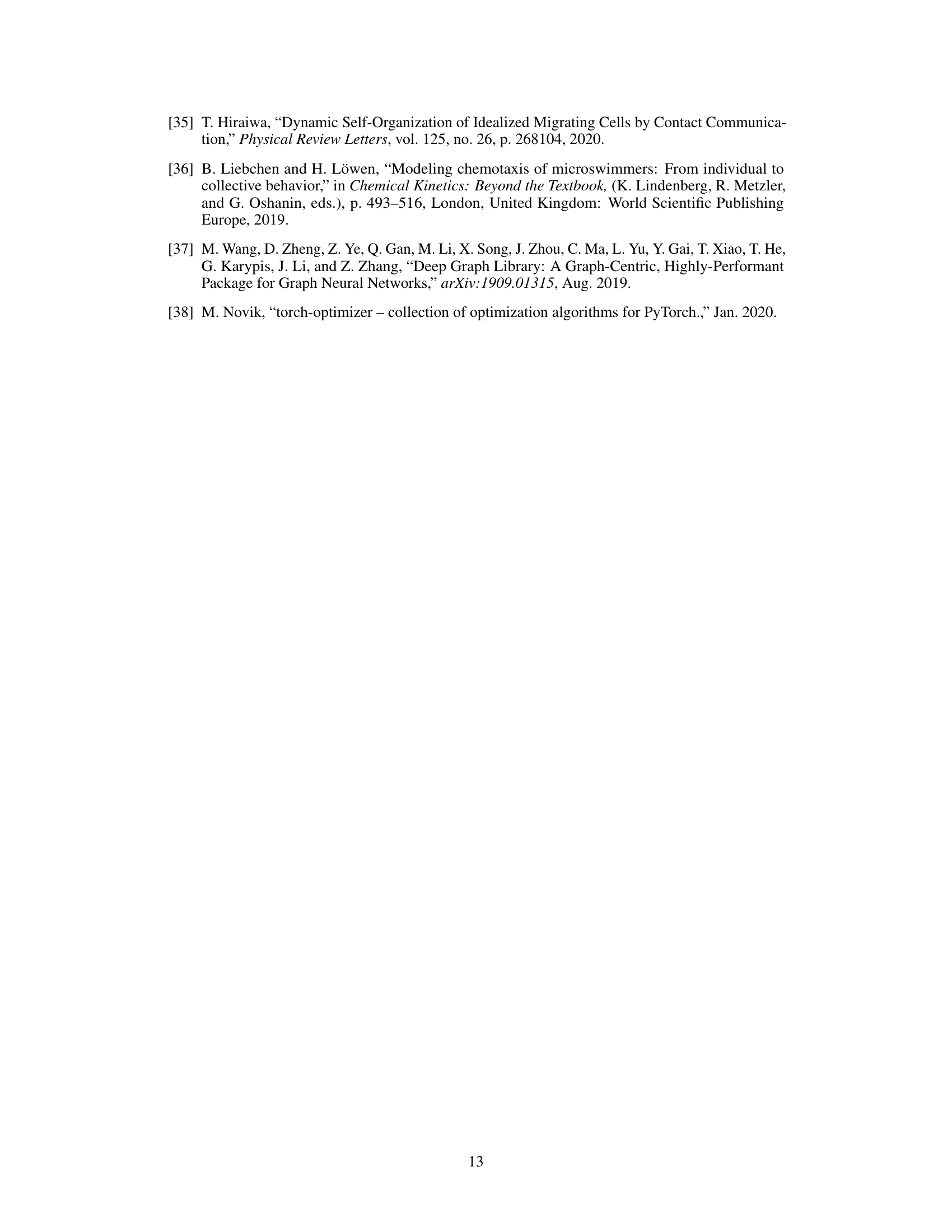

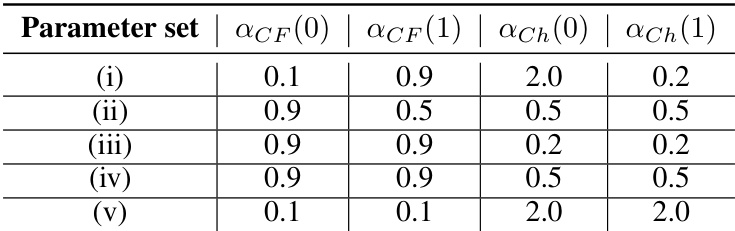

This table lists the different parameter sets used in the simulations of the mixed-species model. Each parameter set represents a different combination of values for ACF(0), ACF(1), αCh(0), and αCh(1). These parameters control the strengths of contact following and chemotaxis, which are species-dependent in the mixed-species model. The different parameter sets lead to distinct collective behaviors.

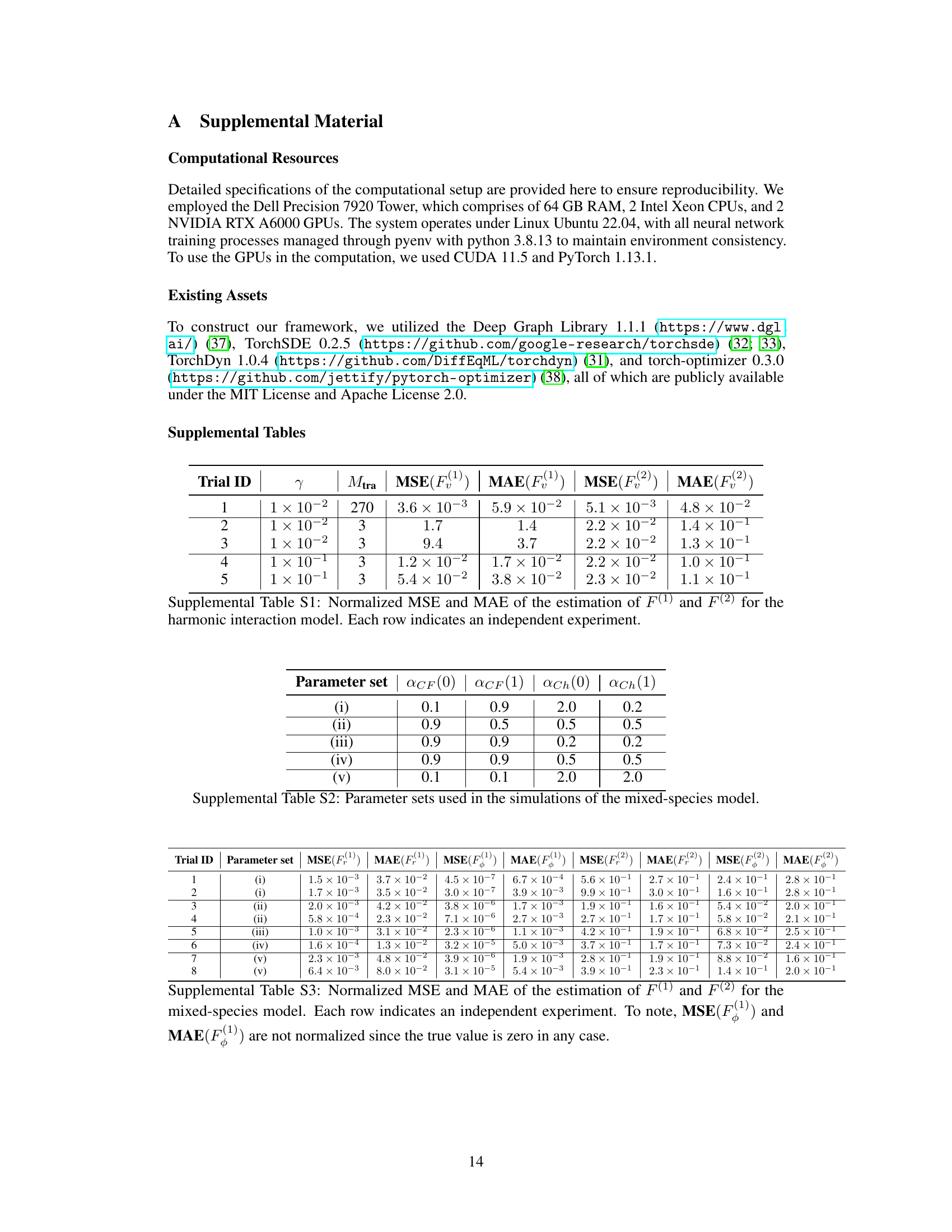

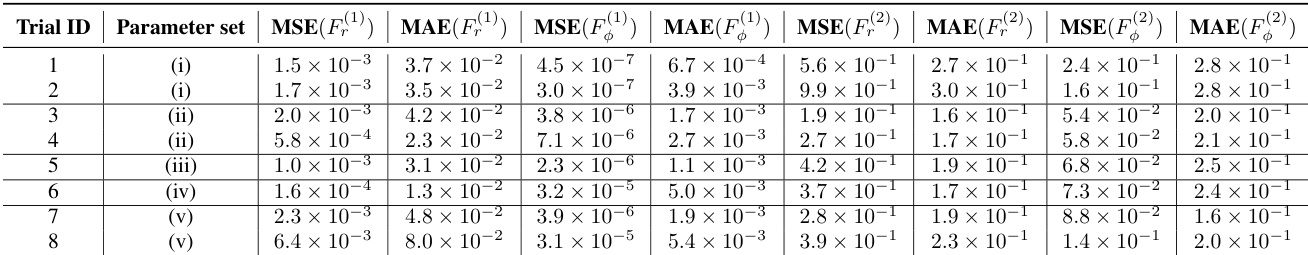

This table presents the normalized Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for the estimation of self-propulsion forces (F(1)) and interaction forces (F(2)) in a mixed-species collective motion model. The results are shown for eight independent experiments, each using a different parameter set. Note that MSE and MAE for F(1) are not normalized as the true values are zero.

Full paper#