↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many computational tasks are best solved by combining neural networks and programs (neural programs). However, training these composites is challenging when the program part is a black-box (e.g., an API call or LLM). Existing methods either struggle with sample efficiency or require modifying the program for differentiability.

This paper introduces ISED, a novel algorithm tackling this problem. ISED uses reinforcement learning to estimate gradients using only input/output examples. It’s tested on various tasks, showing better performance and efficiency than baselines, especially in tasks using modern LLMs. The improved data efficiency addresses a significant bottleneck in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it presents ISED, a novel algorithm that significantly improves data and sample efficiency in neural program learning. This addresses a key limitation in the field, enabling researchers to train models more effectively with limited data and resources, opening new avenues in neurosymbolic AI.

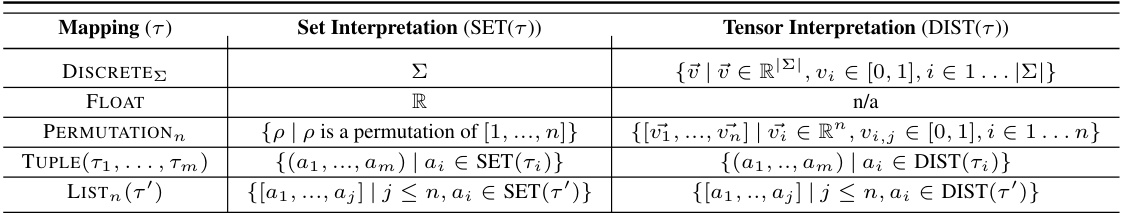

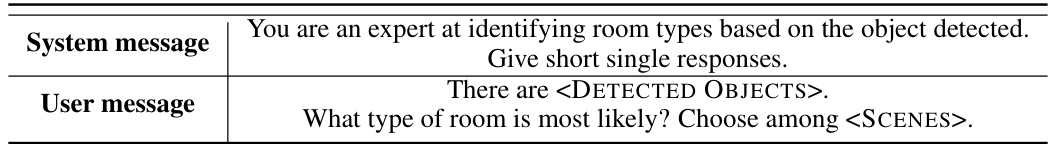

Visual Insights#

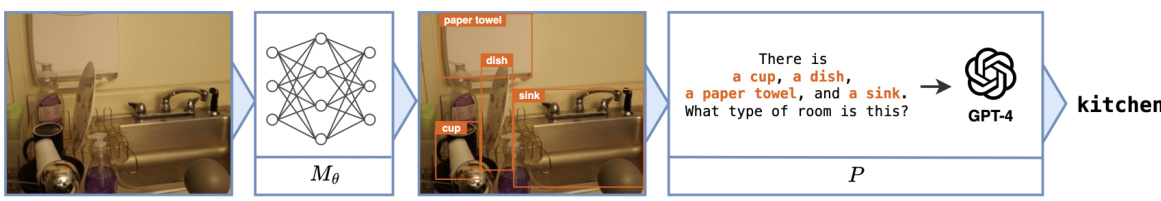

This figure illustrates the decomposition of a scene recognition task into a neural model and a program. The neural model (Mθ) processes an image and identifies objects within the scene. The output of the neural model is then fed into a program (P) that utilizes a large language model (LLM), specifically GPT-4 in this instance, to determine the room type based on the identified objects. The input image shows a kitchen scene with a sink, cup, dish and paper towel. The neural model detects these objects and provides this information as input to the program. The program then utilizes this input to query the LLM, resulting in the final output of ‘kitchen.’

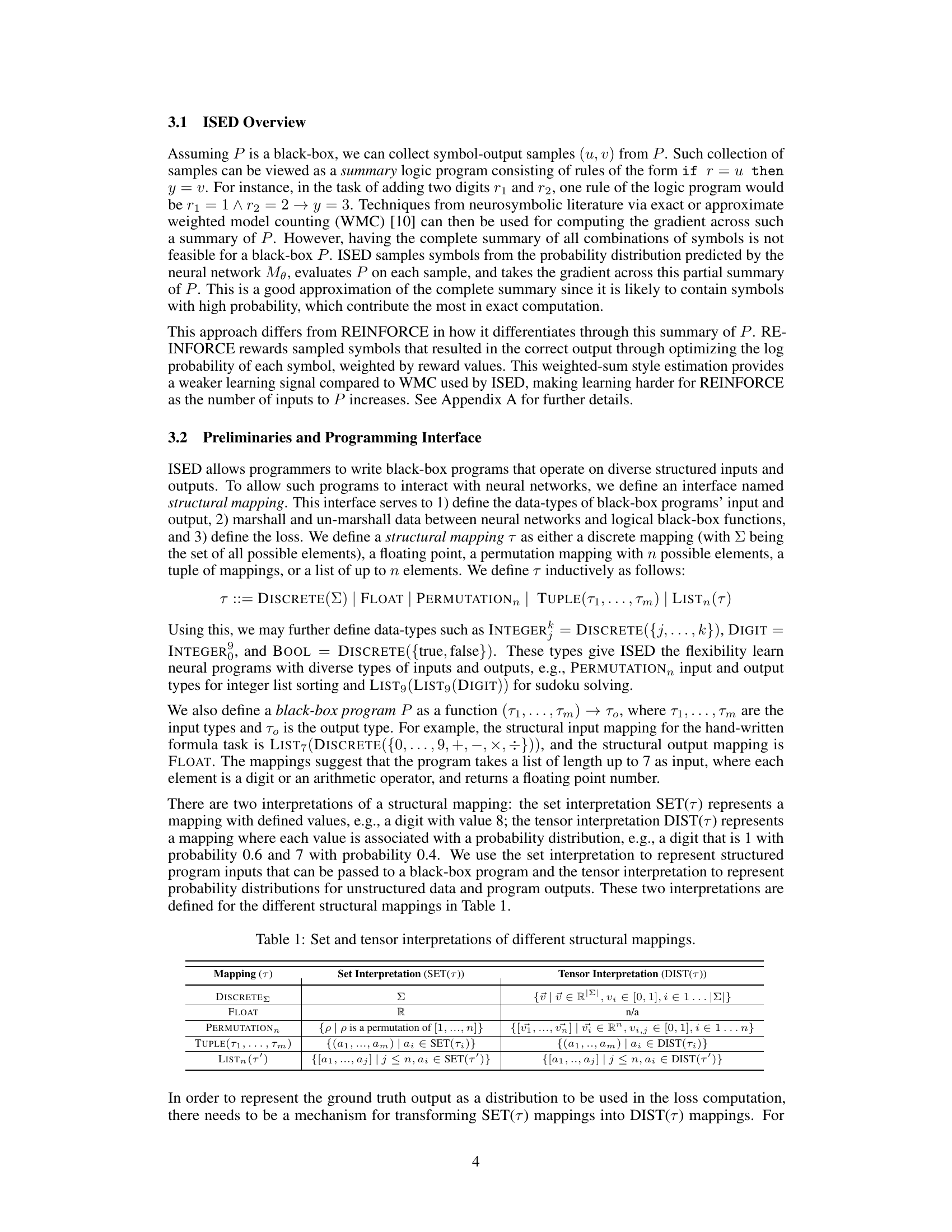

This table presents the accuracy results of different methods on various benchmark tasks. The methods are categorized into three groups: neurosymbolic, black-box gradient estimation, and REINFORCE-based. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on several tasks, including sum, HWF, leaf classification, scene recognition, and sudoku. ‘TO’ indicates that the method timed out, and ‘N/A’ means the task was not applicable to the given method.

In-depth insights#

Neural Program Learning#

Neural program learning combines the strengths of neural networks and symbolic programming, aiming to overcome limitations of each. Neural networks excel at perception and pattern recognition, but struggle with reasoning and symbolic manipulation. Conversely, symbolic methods are strong at reasoning but lack the ability to learn from data efficiently. Neural program learning seeks to bridge this gap by expressing tasks as a composition of a neural model (e.g., for feature extraction) followed by a program (e.g., for reasoning or decision-making). This hybrid approach leverages the data efficiency of neural networks and the reasoning power of symbolic programming. Key challenges in this field include making the program component differentiable (or approximating gradients effectively), handling programs written in non-differentiable languages, and achieving efficient learning when dealing with large or complex programs. The ultimate goal is to create systems that can learn and reason effectively in a way that is both data efficient and capable of solving complex tasks that cannot be solved by either neural networks or symbolic programs alone.

ISED Algorithm#

The ISED algorithm, introduced for data-efficient learning with neural programs, cleverly addresses the challenge of gradient calculation with black-box components. ISED’s core innovation lies in its infer-sample-estimate-descend (ISED) framework. It begins by inferring a probability distribution over program inputs using a neural model. Then, it samples representative inputs and executes the black-box program to generate corresponding outputs, effectively creating a summarized symbolic program. This allows ISED to estimate gradients using reinforcement learning principles without directly differentiating the black-box. This indirect gradient approach is key to ISED’s data efficiency, as it sidesteps the limitations of REINFORCE and other black-box gradient methods. However, while efficient, ISED’s scalability may be limited by the dimensionality of the program’s input space; the choice of aggregator function also impacts the final accuracy. Despite these limitations, ISED demonstrates comparable or superior performance across various neural program benchmarks compared to other neurosymbolic and neural-only approaches, highlighting its potential in scenarios with limited labeled data.

Benchmark Tasks#

The selection of benchmark tasks is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of a novel neural program learning algorithm like ISED. A diverse set of tasks is needed to demonstrate the algorithm’s generalizability and robustness. The paper’s choice to include tasks involving modern LLMs (like GPT-4) is a strong point, showcasing the algorithm’s applicability beyond traditional neurosymbolic domains. The inclusion of established neurosymbolic benchmarks provides a fair comparison against existing methods, allowing a more nuanced evaluation of ISED’s performance. However, the specific choice of tasks and datasets requires careful consideration. It’s important to examine whether the selected tasks adequately represent the full range of potential applications for neural program learning, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation rather than focusing solely on specific problem types. Ultimately, the success of the evaluation depends on the representativeness and difficulty of the benchmark tasks; the paper should justify the choices made in this aspect.

Sample Efficiency#

Sample efficiency, a crucial aspect in machine learning, is thoroughly investigated in this research. The authors demonstrate that their proposed ISED algorithm significantly improves upon existing methods, such as REINFORCE and IndeCateR, in terms of data requirements for achieving comparable accuracy. ISED’s enhanced sample efficiency stems from its unique approach to gradient estimation, which leverages sampled symbol-output pairs to create a summarized logic program, thereby providing a stronger learning signal than REINFORCE-based alternatives. This advantage is particularly pronounced when dealing with complex programs or large input spaces, as demonstrated by the experimental results showing ISED’s superior performance across various benchmarks. The improved sample efficiency translates to reduced computational costs and faster training times, making ISED a more practical solution for real-world applications where data is often scarce or expensive to acquire. The study highlights the trade-off between sample complexity and model complexity; while ISED shines in sample efficiency, limitations emerge with high-dimensional inputs, pointing to a potential avenue for future research and improvements.

Future Directions#

The paper’s exploration of future directions highlights several key areas for improvement and expansion. Addressing the scalability limitations of ISED with high-dimensional input spaces is paramount, suggesting the need for advanced sampling strategies perhaps borrowing from Bayesian optimization. Another crucial direction lies in combining the strengths of white-box and black-box methods, potentially creating a more robust and efficient neurosymbolic programming language. This would leverage ISED’s ability to handle black-box components while integrating the benefits of explicit symbolic reasoning where appropriate. Further research could focus on enhancing ISED’s performance with complex programs by investigating superior gradient estimation techniques. Finally, a significant area for exploration involves applying ISED to a broader range of tasks and domains, demonstrating its generalizability and practicality for real-world applications. This could involve expanding beyond the benchmarks already tested and exploring its compatibility with diverse programing languages and APIs.

More visual insights#

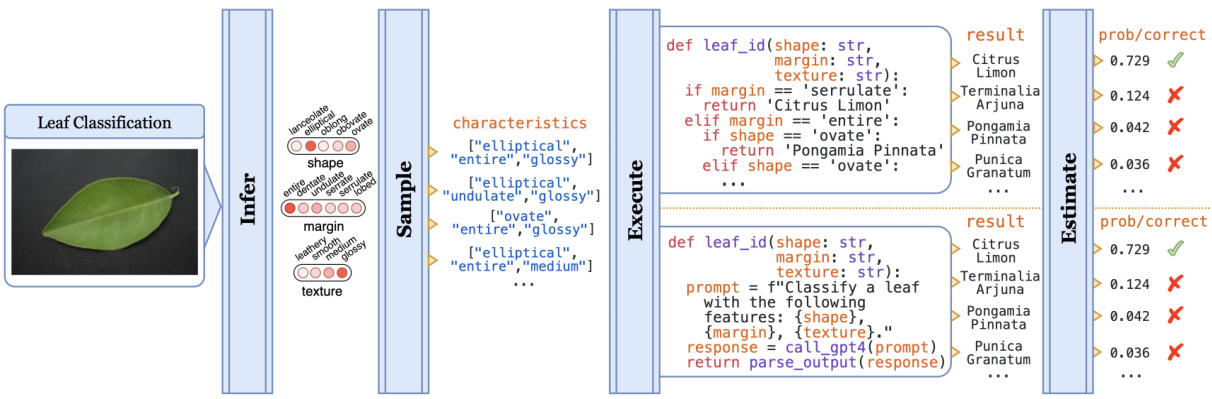

More on figures

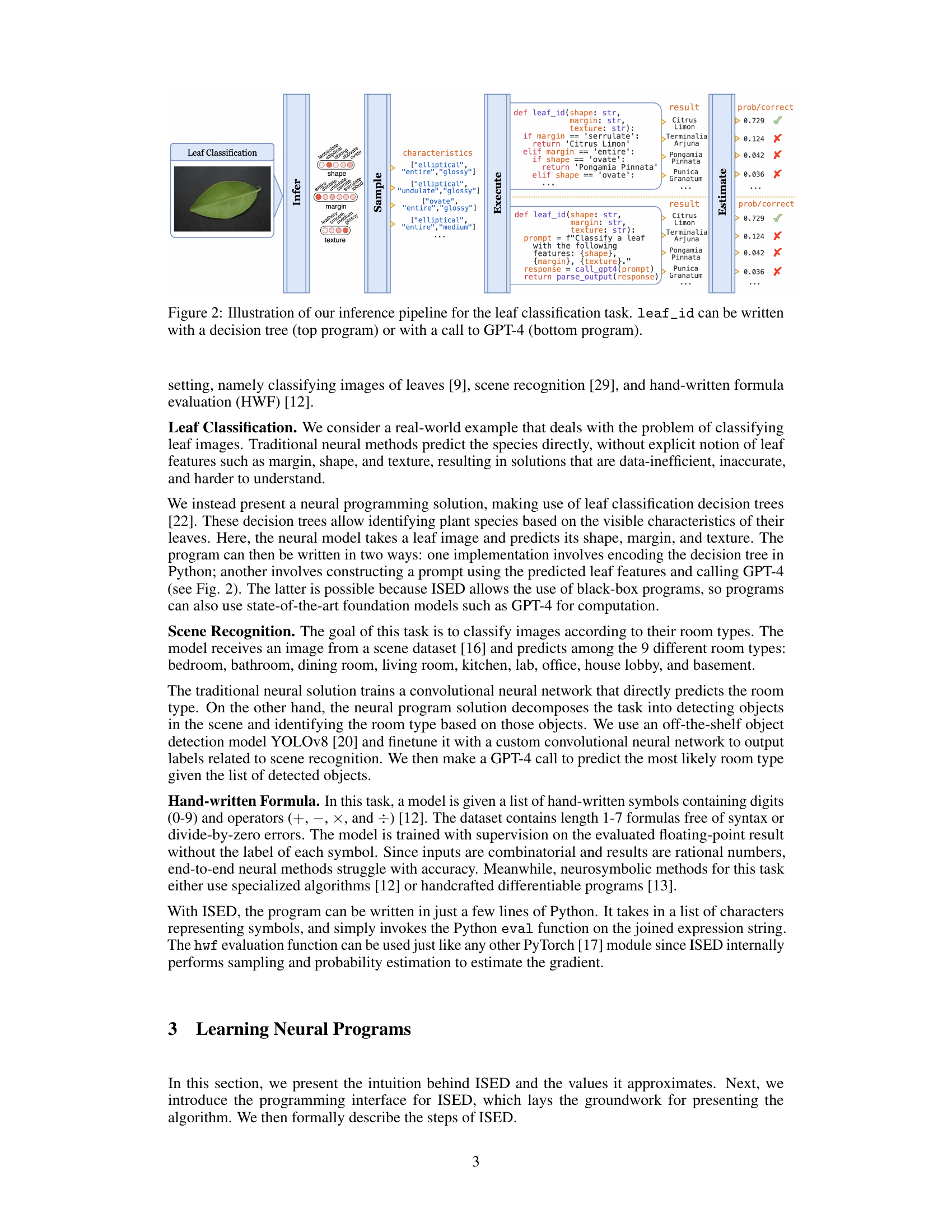

This figure illustrates the inference pipeline for the leaf classification task. The input is a leaf image, which is processed by a neural model to predict three leaf characteristics: shape, margin, and texture. These characteristics are then used as input to a program, leaf_id, which can be implemented either as a traditional decision tree or as a call to GPT-4. The output of leaf_id is a classification of the leaf species along with a probability score indicating the confidence of the prediction.

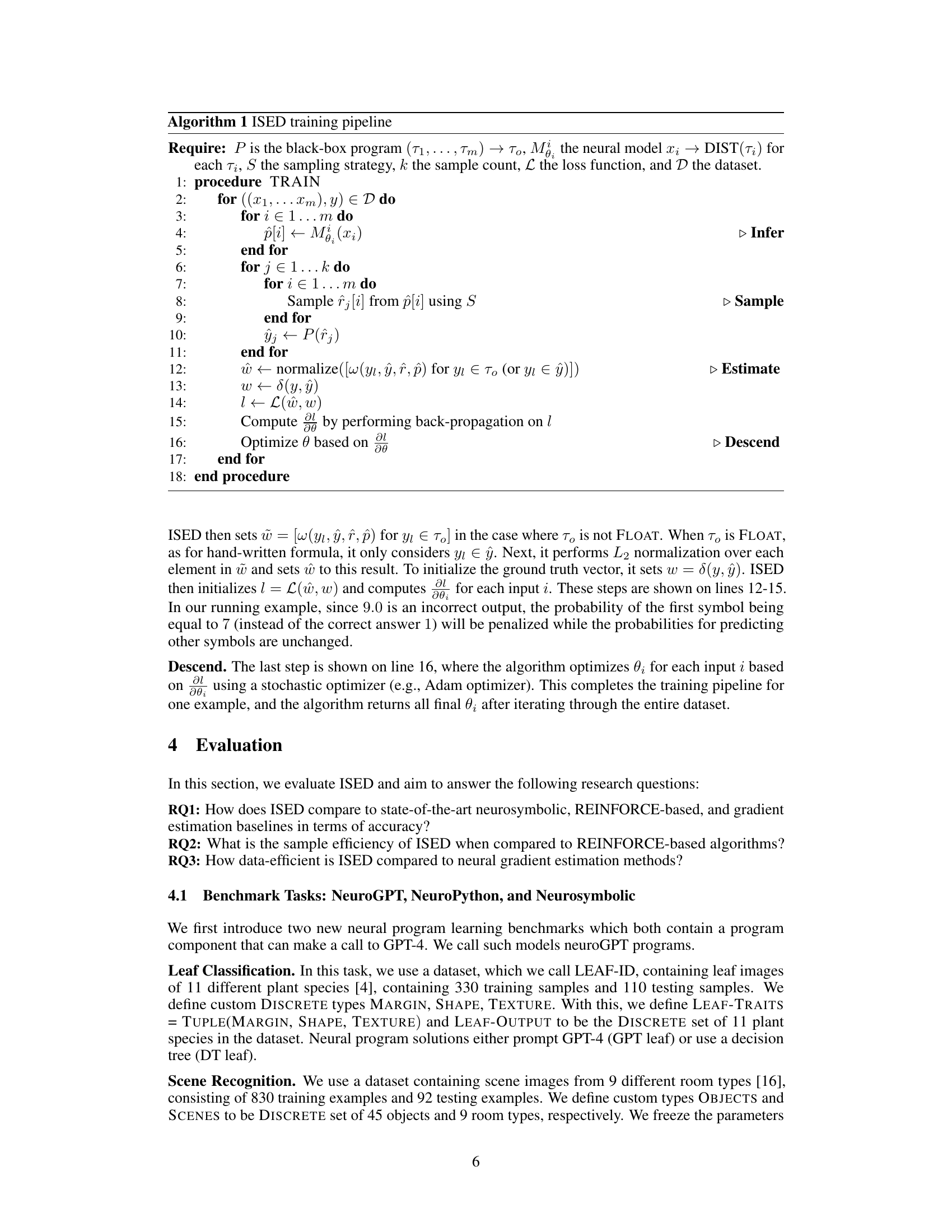

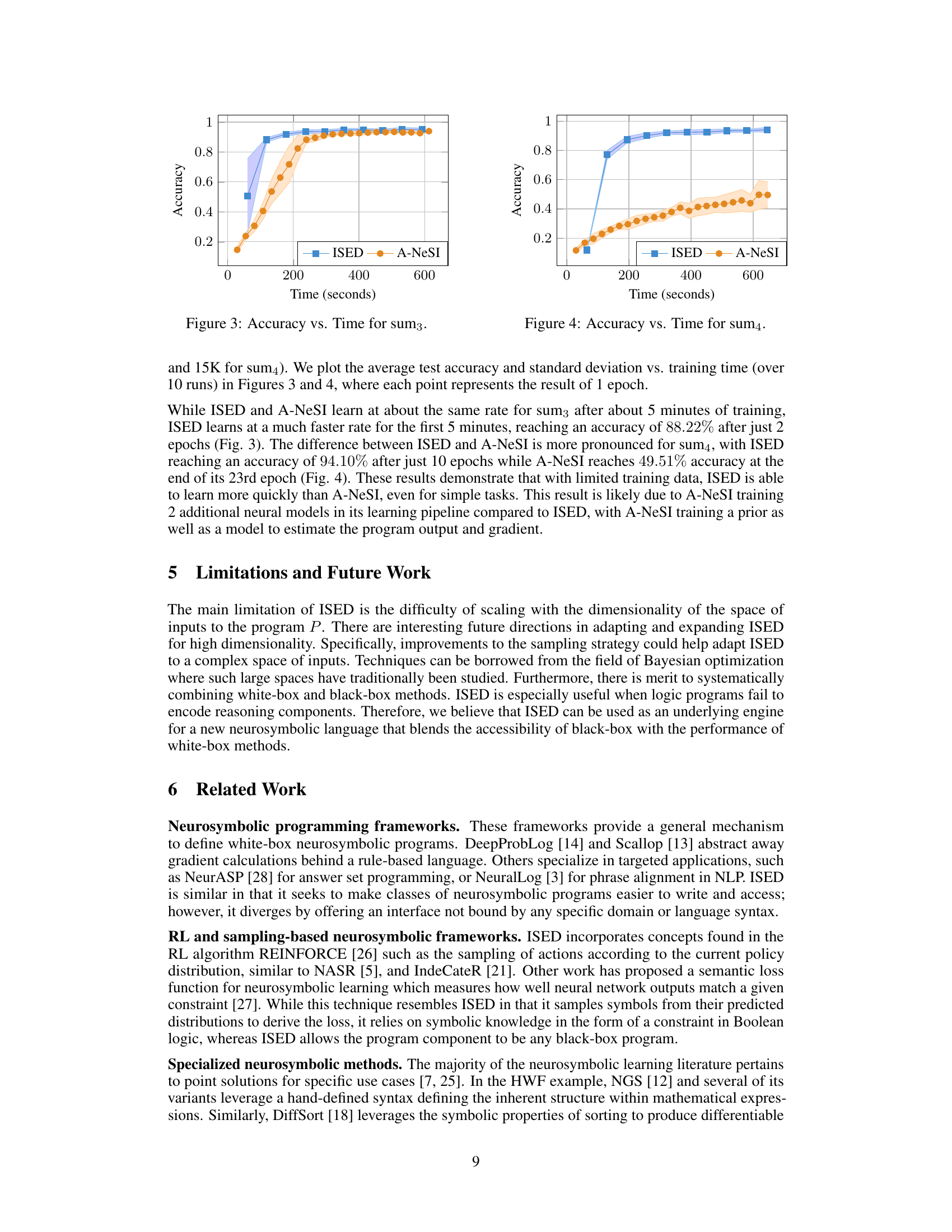

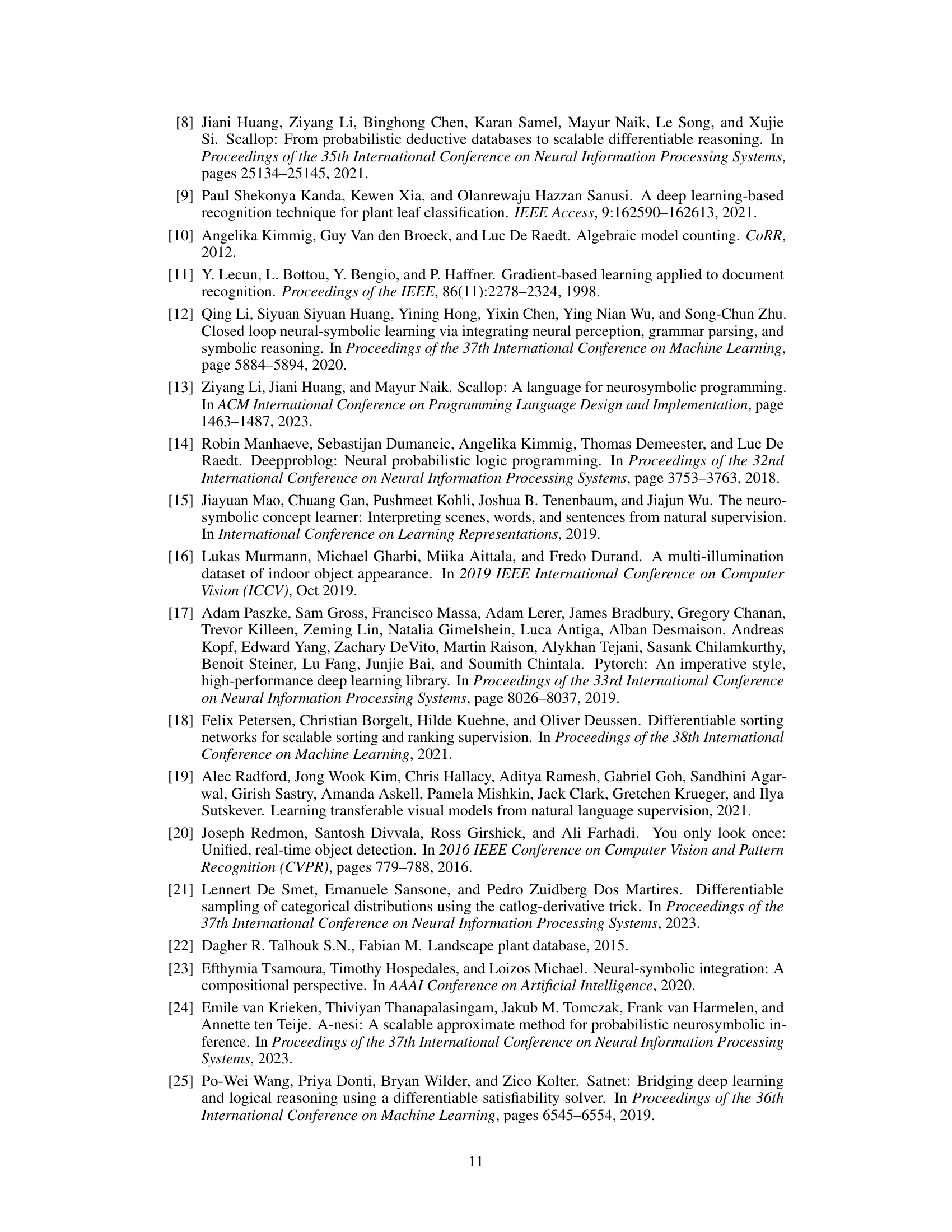

This figure shows a comparison of the accuracy over time for the ISED and A-NeSI methods on the ‘sum3’ task from the MNIST-R benchmark. The x-axis represents training time in seconds, and the y-axis shows the accuracy. The blue line and squares represent ISED, while the orange line and circles represent A-NeSI. Shaded areas show standard deviations. The figure illustrates that ISED achieves higher accuracy more quickly than A-NeSI in the early stages of training.

This figure shows the accuracy of ISED and A-NeSI over training time (in seconds) for the sum3 task from the MNIST-R benchmark. ISED demonstrates significantly faster learning, reaching a higher accuracy much sooner than A-NeSI, highlighting ISED’s greater sample efficiency. The shaded regions represent standard deviations.

More on tables

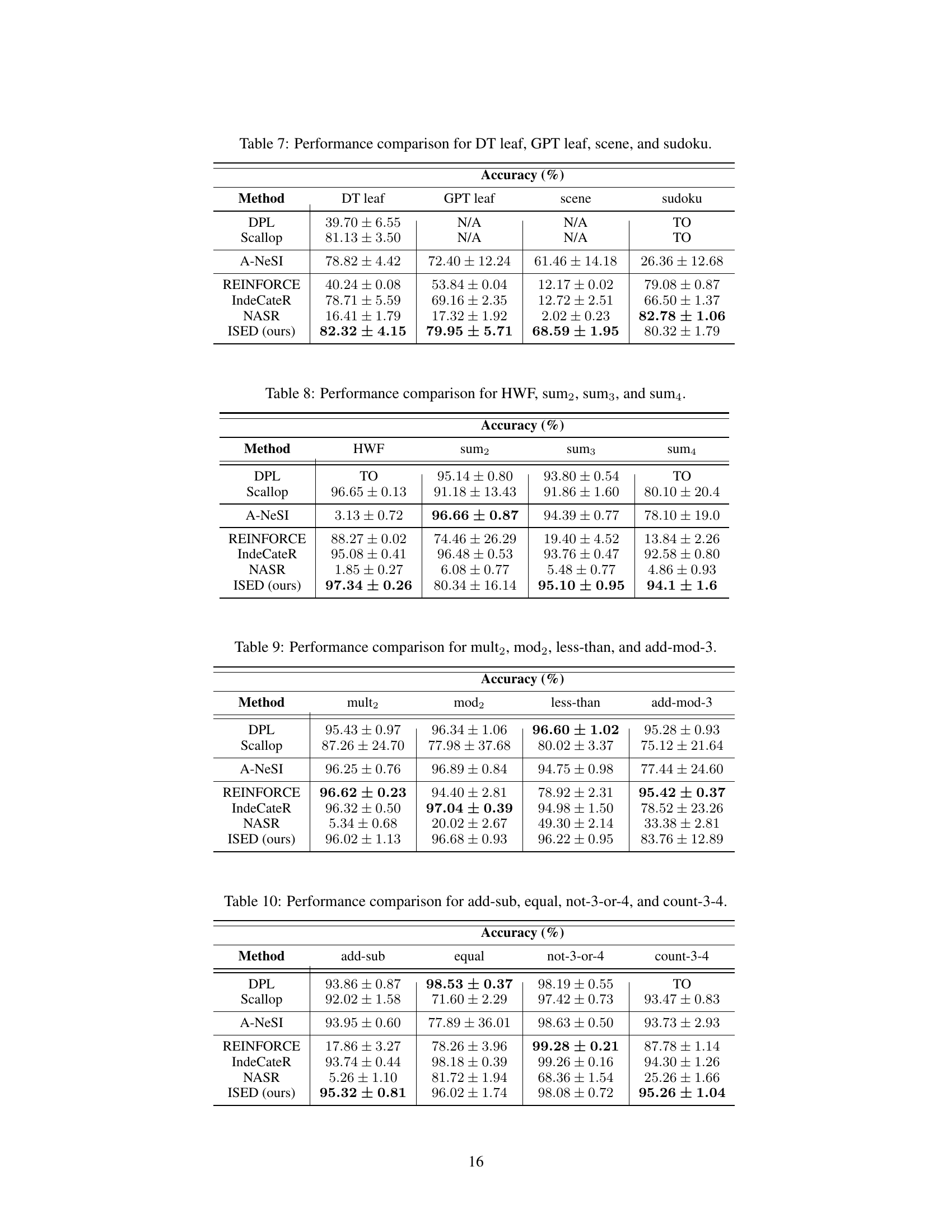

This table presents the accuracy of different methods on several benchmark tasks. The methods are categorized into three groups: neurosymbolic methods, black-box gradient estimation methods, and REINFORCE-based methods. The accuracy is presented as a percentage for each method and task. ‘TO’ indicates that the method timed out on the task, while ‘N/A’ means the task could not be implemented using that framework.

This table presents the accuracy results of different methods on several benchmark tasks. The methods are categorized into three groups: neurosymbolic, black-box gradient estimation, and REINFORCE-based. The table shows the performance of each method on various tasks, including sum2, sum3, sum4, HWF, DT leaf, GPT leaf, scene, and sudoku. ‘TO’ indicates that the method timed out on the specific task, and ‘N/A’ means that the task was not applicable for that method.

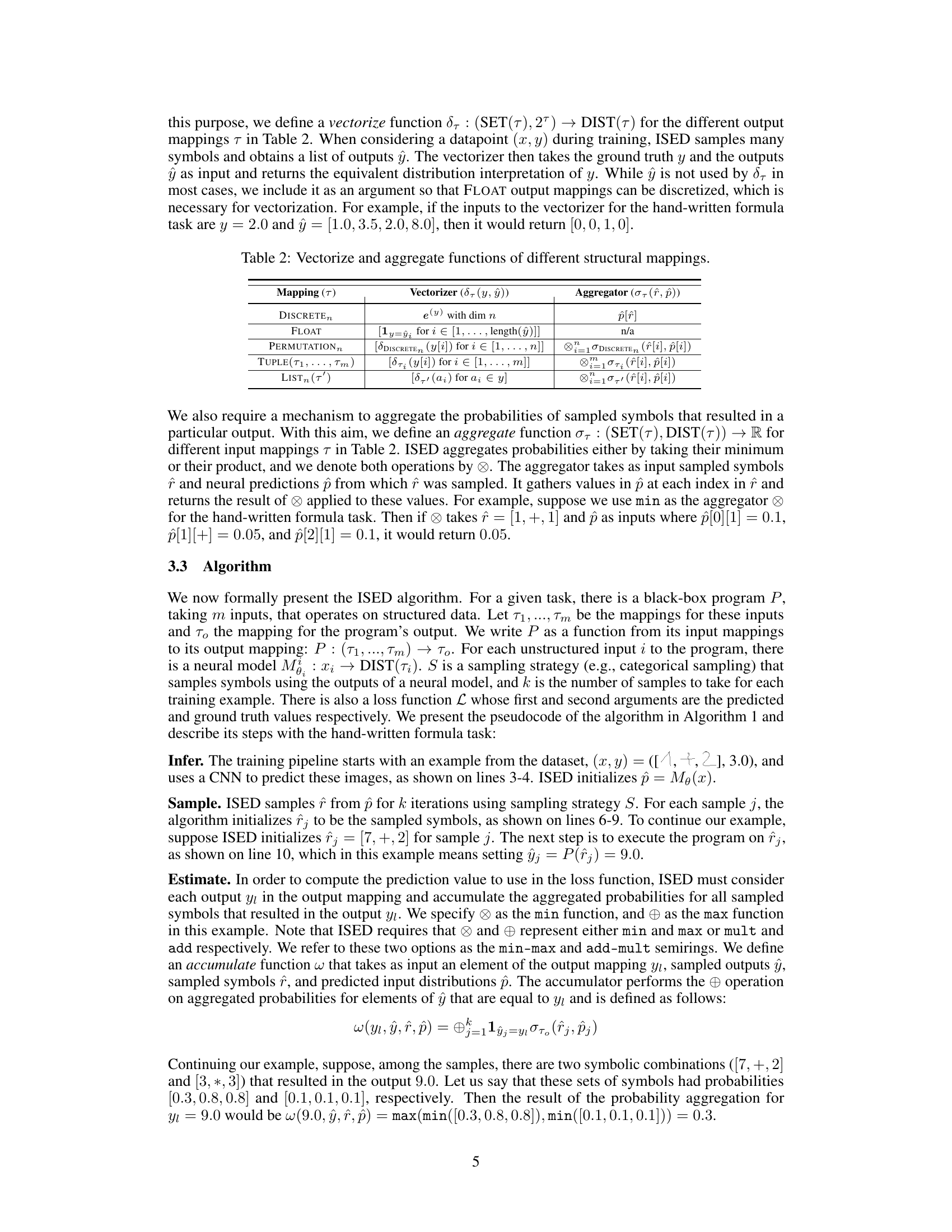

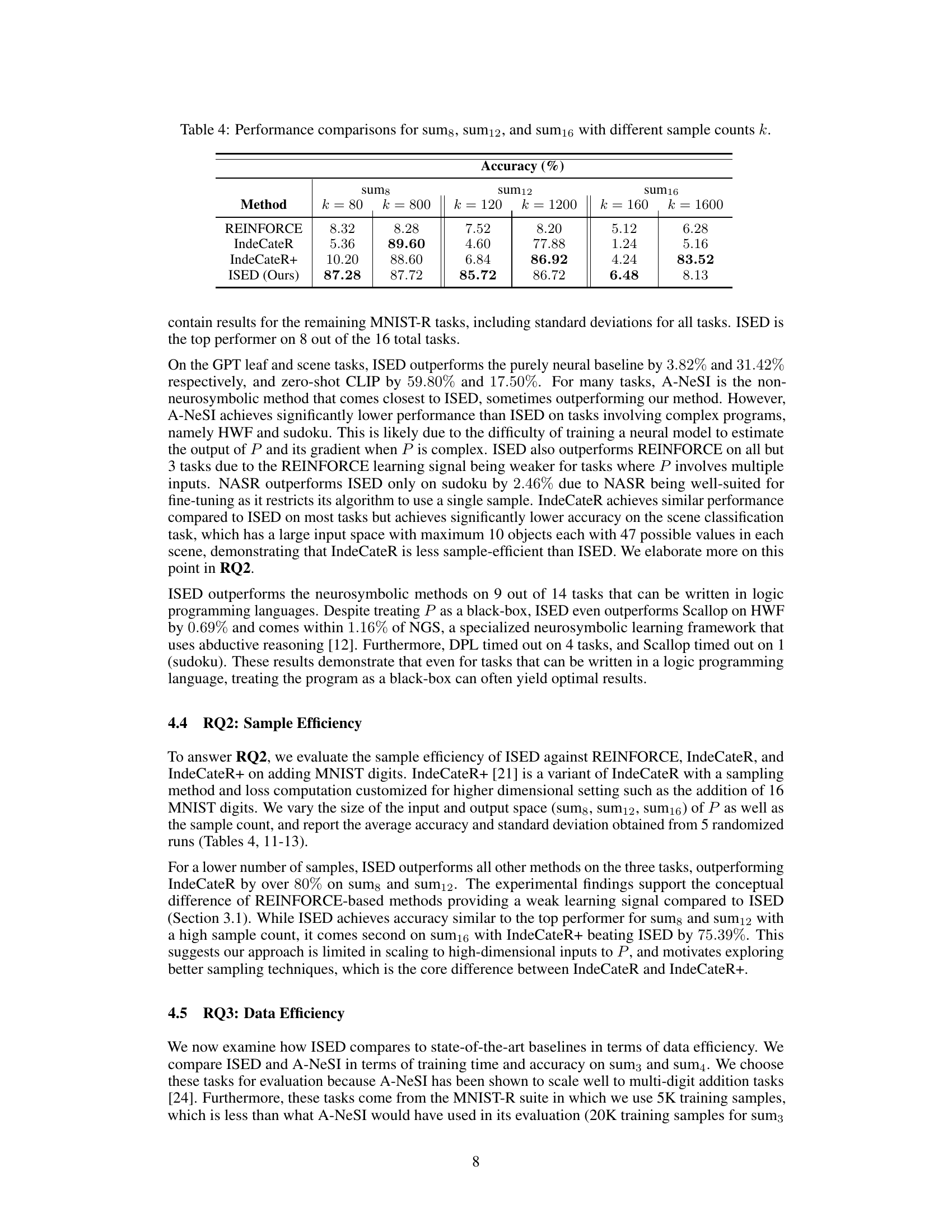

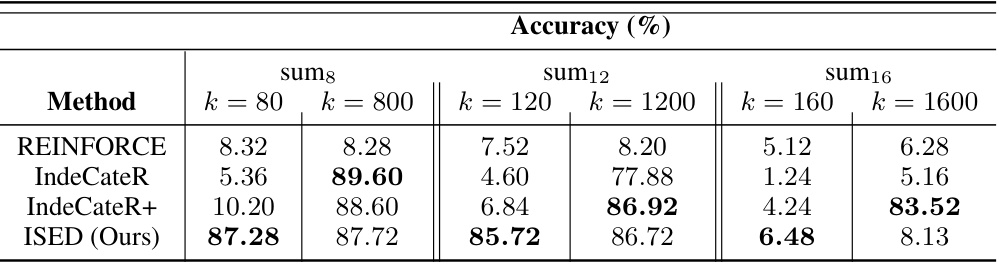

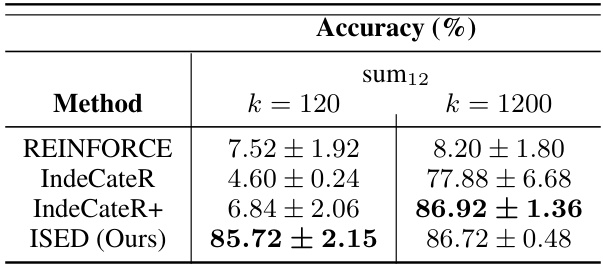

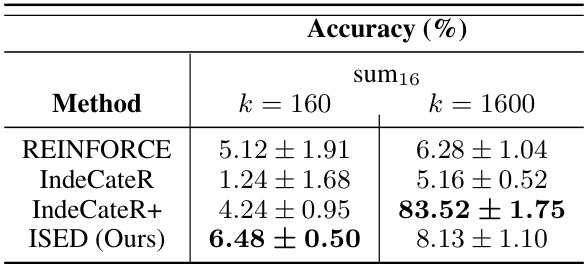

This table presents the accuracy results for three different tasks (sum8, sum12, and sum16) using four different methods (REINFORCE, IndeCateR, IndeCateR+, and ISED) with varying sample counts (k = 80, 800, 120, 1200, 160, 1600). The tasks involve adding different numbers of MNIST digits. The table demonstrates the sample efficiency of each method by showing how accuracy changes as the number of samples increases.

This table presents the accuracy results of different methods on several benchmark tasks. The benchmarks are categorized into three types: neurosymbolic, black-box gradient estimation, and REINFORCE-based. Each row represents a different learning method. Each column represents the accuracy of the method on a specific benchmark. ‘TO’ indicates that the method timed out on that benchmark, and ‘N/A’ indicates that the benchmark was not applicable to that method. The table allows for comparison of various approaches to neural program learning.

This table presents the accuracy of different methods on various benchmark tasks. The methods are categorized into three groups: neurosymbolic, black-box gradient estimation, and REINFORCE-based. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method on several tasks, including those involving sum, HWF, leaf classification, scene recognition, and sudoku. ‘TO’ indicates that the method timed out for the given task, and ‘N/A’ means the task could not be implemented using that method.

This table presents the accuracy results (%) of different methods on various benchmark tasks. The methods are categorized into three groups: neurosymbolic methods (DPL, Scallop, A-NeSI), black-box gradient estimation methods (REINFORCE), and REINFORCE-based methods (IndeCateR, NASR, ISED). The benchmarks include tasks from various domains such as sum, HWF, leaf classification, and scene recognition. ‘TO’ indicates that the method timed out on the task, and ‘N/A’ indicates that the task could not be implemented with the particular method. ISED represents the proposed method of the paper.

This table presents the accuracy of different methods on several benchmark tasks. The methods are categorized into three groups: neurosymbolic, black-box gradient estimation, and REINFORCE-based. The table shows the accuracy for each method on different tasks, with ‘TO’ indicating a timeout and ‘N/A’ indicating that the task could not be performed by the given method. This allows for a comparison of the performance of different approaches across various types of tasks.

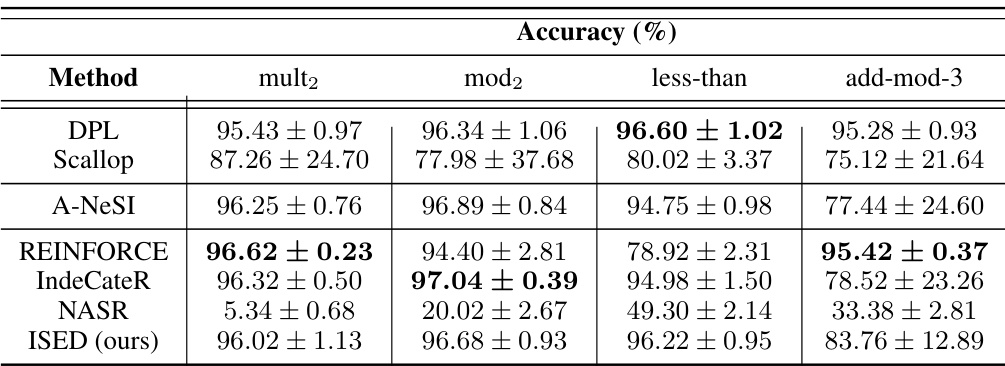

This table presents a comparison of the accuracy achieved by various methods (DPL, Scallop, A-NeSI, REINFORCE, IndeCateR, NASR, and ISED) on four different MNIST-R tasks: mult2, mod2, less-than, and add-mod-3. Each task involves performing a specific arithmetic or comparison operation on pairs of handwritten digits from the MNIST dataset. The table shows the accuracy of each method, along with the standard deviation, illustrating the performance variations. This allows for a comparison of the relative performance of different approaches on these tasks.

This table presents the accuracy results for four different MNIST-R tasks (add-sub, equal, not-3-or-4, and count-3-4). It compares the performance of several methods: DPL, Scallop, A-NeSI, REINFORCE, IndeCateR, NASR, and ISED (the proposed method). The accuracy is given as a percentage, with standard deviations.

This table presents a comparison of the accuracy achieved by different methods (REINFORCE, IndeCateR, IndeCateR+, and ISED) on three tasks (sum8, sum12, and sum16) with varying sample counts (k = 80, 800, 120, 1200, 160, 1600). The tasks involve adding a certain number of MNIST digits, testing the algorithms’ sample efficiency and performance under different input sizes and complexities. The results highlight how the accuracy of each method changes with the increasing sample count and input size.

This table presents the accuracy achieved by four different methods (REINFORCE, IndeCateR, IndeCateR+, and ISED) on three different tasks (sum8, sum12, and sum16) with two different sample counts (k=80/800, k=120/1200, k=160/1600). The tasks involve adding up to 8, 12, and 16 MNIST digits respectively. The table shows how the accuracy of each method changes with varying sample counts, demonstrating the sample efficiency of each approach. The results highlight that ISED generally outperforms the other methods, especially with lower sample counts.

This table presents the accuracy results for three different tasks (sum8, sum12, sum16) under varying sample counts (k=80, 800, 120, 1200, 160, 1600). The tasks involve adding MNIST digits. The table compares the performance of four different methods: REINFORCE, IndeCateR, IndeCateR+, and ISED. It shows how the accuracy of each method changes as the sample count increases for each task, demonstrating the sample efficiency of the algorithms.

Full paper#