TL;DR#

Predicting the behavior of complex systems across various physical parameters is computationally expensive. Existing methods like score-based diffusion and flow-based modeling face challenges in handling high-dimensional systems, requiring multiple inference steps and struggling to generalize across parameters. These methods also typically focus on individual trajectories, whereas studying the overall population behavior might be more efficient.

This paper introduces a novel method, Higher-Order Action Matching (HOAM), which learns a reduced model of population dynamics by leveraging optimal transport theory. HOAM infers parameter-dependent gradient fields that approximate population dynamics, then uses these to rapidly generate sample trajectories. The method uses higher-order quadrature rules and Monte Carlo sampling to accurately estimate the objective from sample data and stabilize training, achieving accurate predictions with orders of magnitude speedups in inference compared to traditional methods and outperforming existing state-of-the-art approaches.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computational science and machine learning due to its novel approach to parametric model reduction. It offers significant speedups in predicting system behavior across varying parameters and addresses limitations of existing methods. This opens new avenues for tackling high-dimensional and complex systems.

Visual Insights#

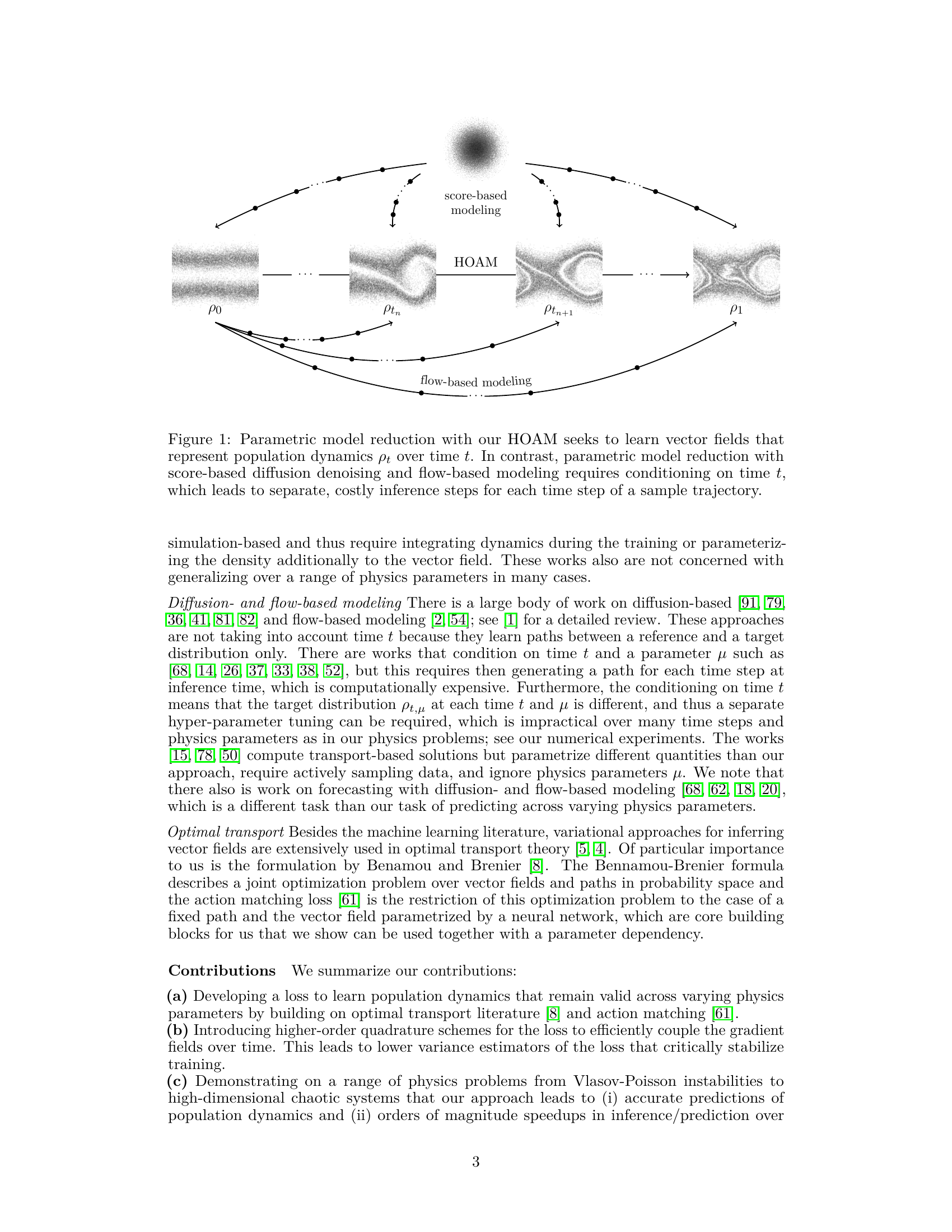

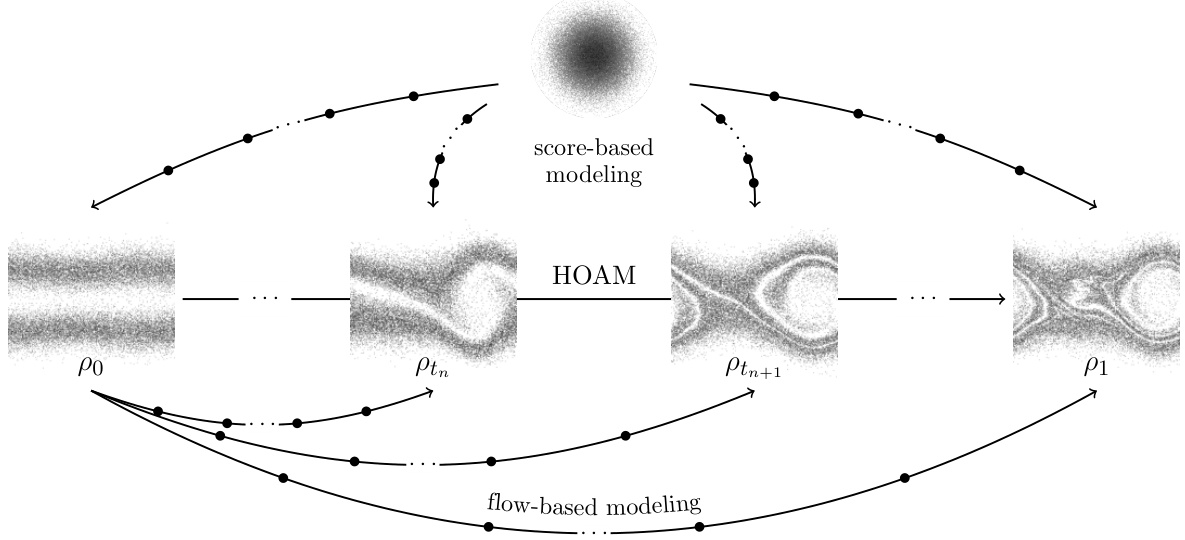

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the proposed HOAM method and compares it with other state-of-the-art methods for parametric model reduction. HOAM learns vector fields that represent the evolution of population dynamics over time, unlike score-based and flow-based models that condition on each time step, leading to more efficient inference. The figure visually depicts this difference by showcasing how HOAM directly predicts entire trajectories, whereas score-based and flow-based models require separate inference steps for each point in time.

read the caption

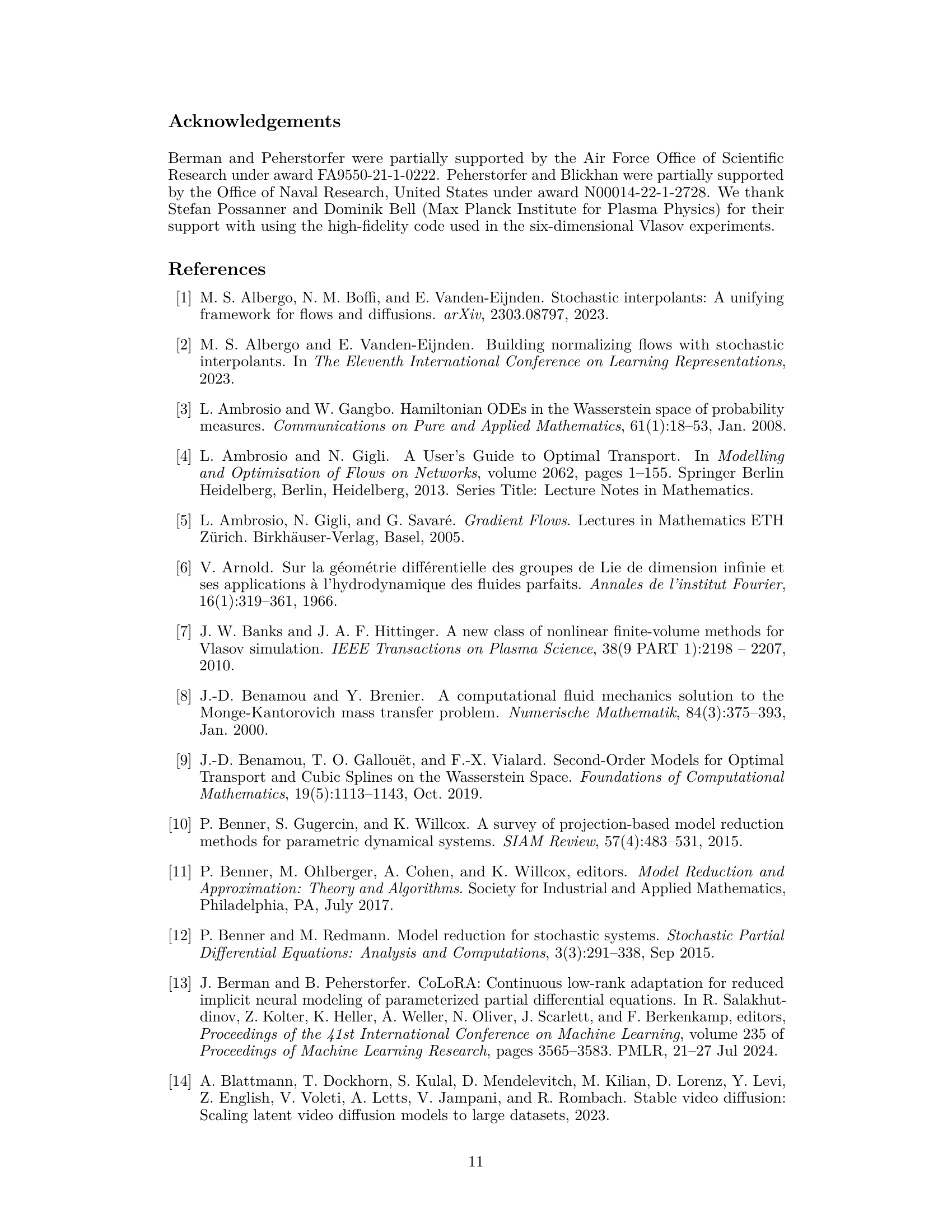

Figure 1: Parametric model reduction with our HOAM seeks to learn vector fields that represent population dynamics pt over time t. In contrast, parametric model reduction with score-based diffusion denoising and flow-based modeling requires conditioning on time t, which leads to separate, costly inference steps for each time step of a sample trajectory.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed Higher-Order Action Matching (HOAM) method with two different quadrature rules (Simpson’s and Gauss-Legendre) against three other state-of-the-art methods (CFM, NCSM, and AM) across six different examples of parametric dynamical systems. The metrics used for comparison are the relative error in the electric energy (e.e.) and the inference runtime (r.t.). The table demonstrates HOAM’s superior performance in terms of both accuracy and speed.

read the caption

Table 1: HOAM with Simpson's and Gauss quadrature outperforms state-of-the-art methods w.r.t. inference runtime (r.t.) with comparable errors when applied to various physics problems for parametric model reduction. Metrics: e.e. is the relative error in electric energy, see (25); for the Sinkhorn divergence, see Appendix B.5.

In-depth insights#

Higher-Order Matching#

Higher-order matching, in the context of the provided research paper, likely refers to a technique that refines the accuracy of action matching by incorporating higher-order information. Standard action matching might focus solely on first-order gradients, resulting in approximations that miss crucial higher-order dynamics. The proposed higher-order approach likely uses higher-order quadrature rules to more precisely estimate the training objective, leveraging more of the sample data’s information. This should yield improved accuracy in capturing the evolution of probability density functions over time and across varying parameter values. The method’s robustness is likely enhanced by mitigating numerical instabilities inherent in gradient estimations and potentially improving the generalization capability to unseen parameter regimes. The efficacy of this refinement in handling complex systems with stochastic and mean-field effects, as well as its computational efficiency and stability, are key areas explored in the paper. The higher-order nature likely offers superior performance compared to the first-order baselines due to the improved precision of the estimated gradients. Overall, this method addresses limitations of simpler action matching approaches and provides a more accurate and potentially more efficient approach to population dynamic modeling.

Physics Parameterization#

The effective incorporation of physics parameters is crucial for building accurate and generalizable reduced models. Parameterization methods must allow for efficient representation of parameter dependencies across various model components. Directly embedding parameters into neural network weights might lead to overfitting or poor generalization. Instead, weight modulation techniques, such as hypernetworks or attention mechanisms, can offer a more robust solution. These methods can dynamically adjust network behavior in response to physics parameters, potentially improving the model’s accuracy and reducing computational cost. The choice of parameterization heavily impacts inference time and model stability. Careful consideration of techniques such as low-rank adaptation and careful hyperparameter tuning is vital to balance model fidelity and computational efficiency. Careful design of the loss function and optimization process to avoid training instabilities is also essential when learning population dynamics. The effectiveness of parameterization should be rigorously evaluated and compared across different methods to ensure the overall performance is improved.

Variational Inference#

Variational inference is a powerful approximate inference technique commonly used when exact inference is intractable, which is often the case in complex probabilistic models. It works by approximating a complex posterior distribution with a simpler, more tractable distribution from a family of variational distributions. This simpler distribution is optimized to be as close as possible to the true posterior, typically measured by the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence. The optimization process involves minimizing the KL divergence, often using gradient-based methods, making variational inference computationally feasible even for high-dimensional problems. Different choices of variational families lead to various variational inference methods, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. For example, mean-field variational inference assumes the variational distribution factors across variables, simplifying the optimization but potentially leading to inaccurate approximations. While efficient, variational inference is sensitive to the choice of the variational family and can provide only an approximation of the true posterior; this means that the results may lack accuracy, particularly when the true posterior is far from the approximating family. Despite this limitation, variational inference remains a vital tool for Bayesian analysis and machine learning, enabling the use of probabilistic models in complex situations.

Numerical Experiments#

The Numerical Experiments section of this research paper is crucial for validating the proposed higher-order action matching (HOAM) method. The authors wisely selected diverse examples spanning various complexities: harmonic oscillators with noise, high-dimensional chaotic systems, and the challenging Vlasov-Poisson equations exhibiting instabilities. The choice of examples demonstrates a thorough evaluation across different problem types, highlighting the method’s generalizability. The inclusion of analytical solutions or high-fidelity numerical results for some examples allows for a direct comparison and quantification of accuracy. The section also appropriately addresses the critical role of numerical quadrature, highlighting its impact on stability and accuracy against Monte Carlo approaches. By comparing HOAM with baselines such as standard action matching and state-of-the-art methods, the paper strongly supports its claims of improved accuracy and efficiency. The detailed presentation of results, including error metrics and visualizations like histograms and electric energy plots, makes the findings readily understandable and compelling. This in-depth analysis of the numerical experiments significantly contributes to the paper’s overall credibility and impact.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the approach to encompass a broader range of physical systems is crucial, moving beyond the specific examples presented. This involves investigating the robustness and generalizability of the method to systems with diverse characteristics and complexities. A deeper investigation into the theoretical underpinnings of the higher-order action matching (HOAM) framework is warranted. This could involve a rigorous mathematical analysis of the method’s convergence properties and error bounds, potentially leading to improved training algorithms and enhanced predictive accuracy. Moreover, developing more efficient parameterization techniques for the learned vector fields is needed, particularly for high-dimensional systems. This would enable HOAM to scale effectively to even larger and more complex problems, making it a truly practical tool for scientific discovery. Finally, exploring hybrid approaches that combine HOAM with other advanced methods, like physics-informed neural networks or Bayesian techniques, could further enhance the predictive capabilities and reliability of the framework, pushing the boundaries of parametric model reduction.

More visual insights#

More on figures

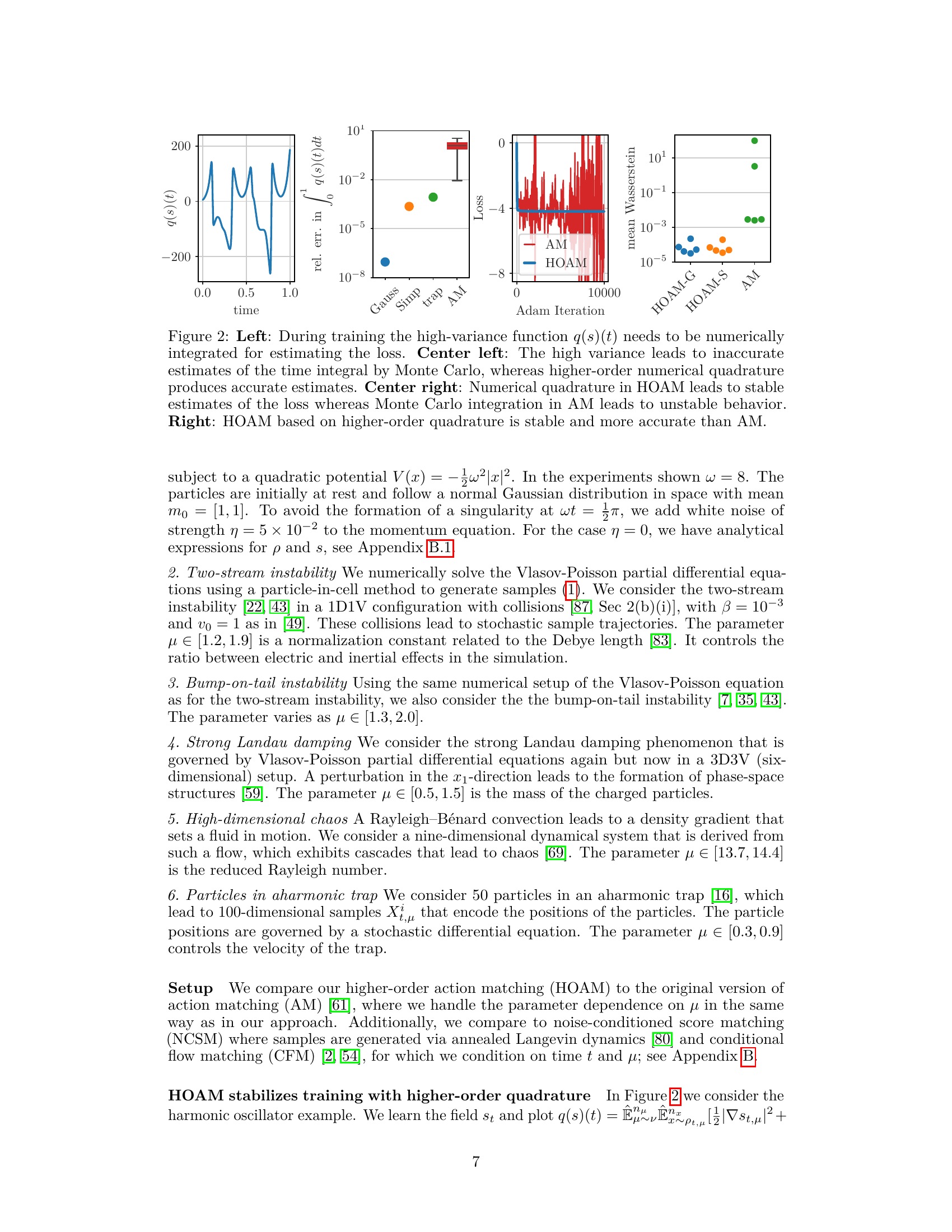

🔼 This figure shows the impact of using higher-order quadrature rules for numerical integration in training the model. The left panel shows the high-variance function that needs to be integrated to estimate the loss. The center-left panel compares the accuracy of Monte Carlo and higher-order quadrature methods for the time integral, highlighting the improved accuracy of higher-order quadrature. The center-right panel illustrates the training stability and the resulting loss estimates of the model when using Monte Carlo versus higher-order quadrature, with the latter displaying significantly improved stability. The right panel provides a comparison of the mean Wasserstein distance between the true and predicted solutions, demonstrating the superiority of the method that uses higher-order quadrature.

read the caption

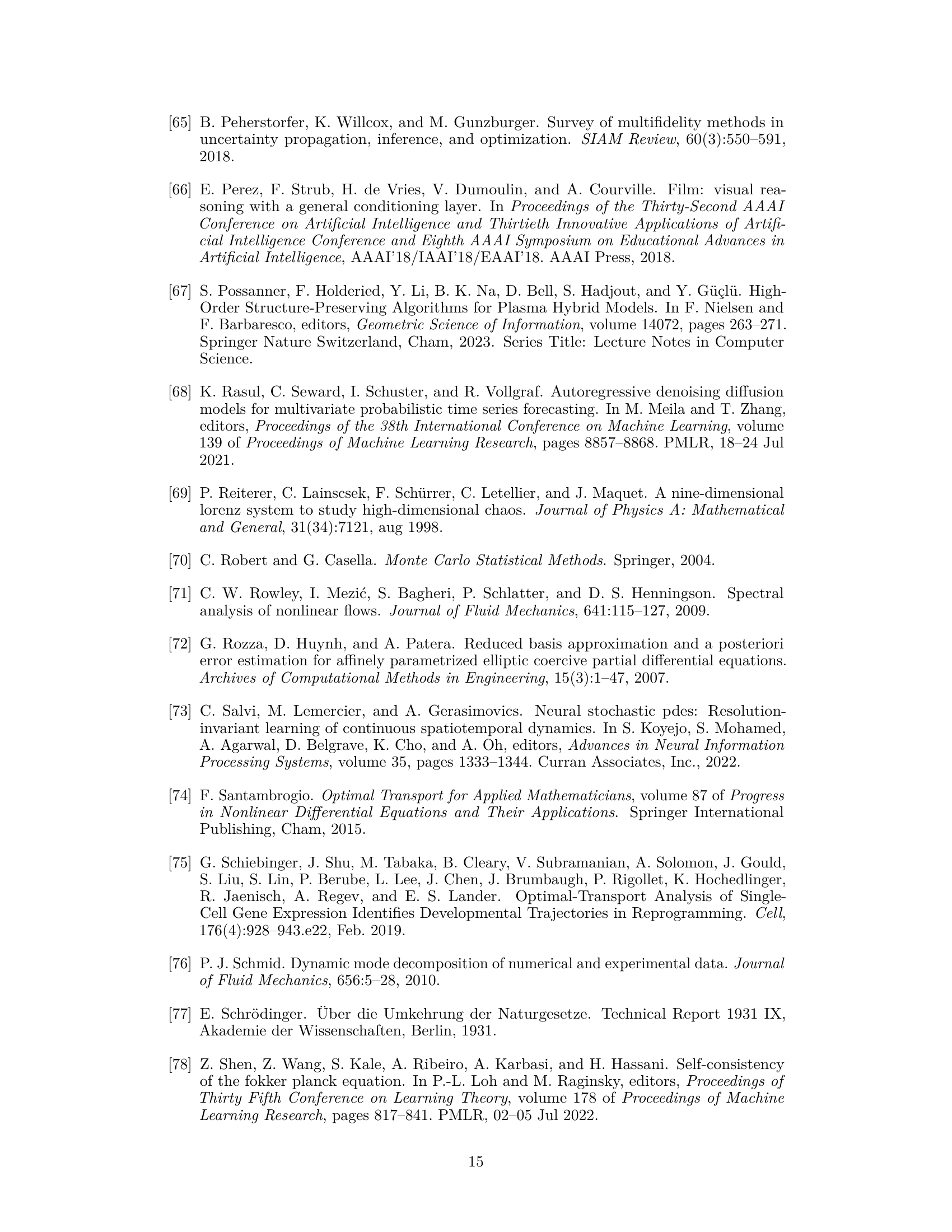

Figure 2: Left: During training the high-variance function q(s)(t) needs to be numerically integrated for estimating the loss. Center left: The high variance leads to inaccurate estimates of the time integral by Monte Carlo, whereas higher-order numerical quadrature produces accurate estimates. Center right: Numerical quadrature in HOAM leads to stable estimates of the loss whereas Monte Carlo integration in AM leads to unstable behavior. Right: HOAM based on higher-order quadrature is stable and more accurate than AM.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed HOAM method and other methods in predicting population density for various physical systems. The top row shows the bump-on-tail instability, the middle top row shows the two-stream instability, the middle bottom row shows the strong Landau damping, and the bottom row shows high-dimensional chaos. The results demonstrate that HOAM with Simpson’s and Gauss quadrature accurately predicts the population density in all four cases, outperforming other methods, especially in complex scenarios with multi-modality and high dimensionality.

read the caption

Figure 3: Histograms of solution fields. Top: Bump-on-tail (t = 20) instability. Middle top: two-stream (t = 20) instability. Middle bottom: Strong Landau damping (t = 4) instability. HOAM with Simpson's and Gauss quadrature accurately predicts the fine scale features and multi-modality of the population density in the Vlasov problems. AM does not converge on the 6 dimensional problem. Bottom: High-dimensional chaos [69] (t = 3.7, dim 3 vs dim 9). HOAM accurately predicts the low probability region that connects the two high probability regions while AM does not converge.

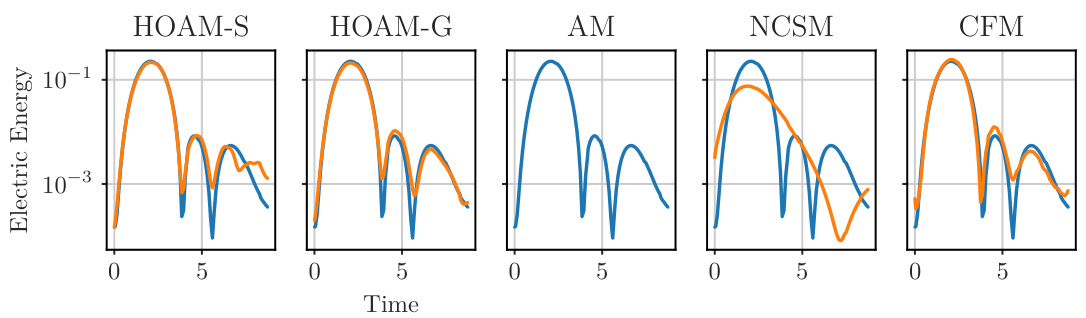

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different methods (HOAM-S, HOAM-G, AM, NCSM, CFM) in predicting the electric energy for the bump-on-tail and two-stream instabilities. The plots show the predicted energy (orange) against the ground truth (blue) over time. The results demonstrate that HOAM, using either Simpson’s or Gauss quadrature, provides a more accurate prediction of the energy growth and subsequent oscillations compared to the other methods. This highlights the effectiveness of HOAM in handling the complexities of these Vlasov-Poisson instabilities.

read the caption

Figure 4: Electric energy of bump-on-tail (top) and two-stream (bottom) instability. HOAM with Simpson's and Gauss quadrature accurately predicts the energy growth in the transient regime and oscillations at later times. The ground truth is displayed in blue.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed HOAM method against other methods (AM, NCSM, CFM) for predicting population density in various dynamical systems. The top row shows the bump-on-tail instability, the second row shows the two-stream instability and the strong Landau damping, and the bottom row shows the high-dimensional chaos. HOAM, using either Simpson’s or Gauss quadrature, accurately predicts the population density, especially the multi-modal distributions and fine-grained features in the Vlasov problems. In contrast, other methods struggle to accurately predict these features or do not converge at all in higher dimensions.

read the caption

Figure 3: Histograms of solution fields. Top: Bump-on-tail (t = 20) instability. Middle top: two-stream (t = 20) instability. Middle bottom: Strong Landau damping (t = 4) instability. HOAM with Simpson's and Gauss quadrature accurately predicts the fine scale features and multi-modality of the population density in the Vlasov problems. AM does not converge on the 6 dimensional problem. Bottom: High-dimensional chaos [69] (t = 3.7, dim 3 vs dim 9). HOAM accurately predicts the low probability region that connects the two high probability regions while AM does not converge.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different methods (HOAM-S, HOAM-G, AM, NCSM, CFM) in predicting the probability density of various physical systems at different time points. The top row shows the bump-on-tail instability, the middle rows show the two-stream and strong Landau damping instabilities, and the bottom row shows a high-dimensional chaotic system. HOAM methods show accurate predictions across all systems, highlighting their ability to capture fine details and multi-modal distributions, unlike the other methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Histograms of solution fields. Top: Bump-on-tail (t = 20) instability. Middle top: two-stream (t = 20) instability. Middle bottom: Strong Landau damping (t = 4) instability. HOAM with Simpson's and Gauss quadrature accurately predicts the fine scale features and multi-modality of the population density in the Vlasov problems. AM does not converge on the 6 dimensional problem. Bottom: High-dimensional chaos [69] (t = 3.7, dim 3 vs dim 9). HOAM accurately predicts the low probability region that connects the two high probability regions while AM does not converge.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different methods (HOAM-S, HOAM-G, AM, NCSM, CFM) in predicting the electric energy for the bump-on-tail and two-stream instabilities. The x-axis represents time, and the y-axis represents the electric energy. The blue line shows the ground truth, while the other lines show the predictions from the different methods. The figure demonstrates that HOAM-S and HOAM-G accurately predict the energy growth and oscillations, outperforming the other methods.

read the caption

Figure 4: Electric energy of bump-on-tail (top) and two-stream (bottom) instability. HOAM with Simpson's and Gauss quadrature accurately predicts the energy growth in the transient regime and oscillations at later times. The ground truth is displayed in blue.

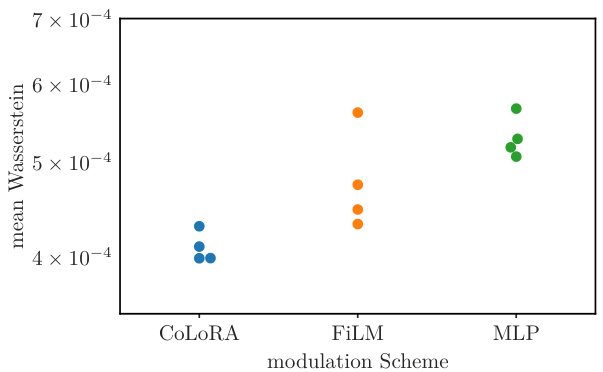

🔼 This figure compares three different modulation schemes (CoLoRA, FiLM, and MLP) used to parameterize the vector field in the harmonic oscillator example. The mean Wasserstein distance is used as a metric to evaluate the performance of each scheme. The results show that CoLoRA outperforms FiLM and MLP, achieving a lower mean Wasserstein distance and avoiding outliers with larger errors.

read the caption

Figure 8: Comparison of CoLoRA modulation scheme [13] versus FiLM [66] and MLP. CoLoRA layers achieve the lowest mean Wasserstein distance compared to FiLM and MLP. In particular, CoLoRA avoids outliers with larger errors.

Full paper#