↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Differentially private top-k selection identifies the k items with the highest scores from a dataset while preserving individual privacy. Existing methods like the JOINT mechanism, while accurate, suffer from high computational costs, particularly when dealing with large datasets. This is problematic as many real-world applications (e.g., search engines, recommendation systems) require processing enormous amounts of data.

This research proposes a novel algorithm that dramatically improves the efficiency of differentially private top-k selection. By using a joint exponential mechanism combined with a pruning technique, the algorithm achieves a significantly reduced time and space complexity of O(d + k²/ɛlnd), where d is the number of items and k is the number to select. The method is shown to be orders of magnitude faster than previous approaches while maintaining comparable accuracy, making differentially private top-k selection more practical for large-scale applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in differential privacy and algorithm design. It significantly improves the efficiency of top-k selection, a fundamental task with broad applications. The faster algorithm enables the scaling of differentially private techniques to larger datasets, opening new avenues for research and practical applications. This work directly addresses limitations in existing methods and provides a valuable solution for improving the scalability and practicality of differentially private data analysis.

Visual Insights#

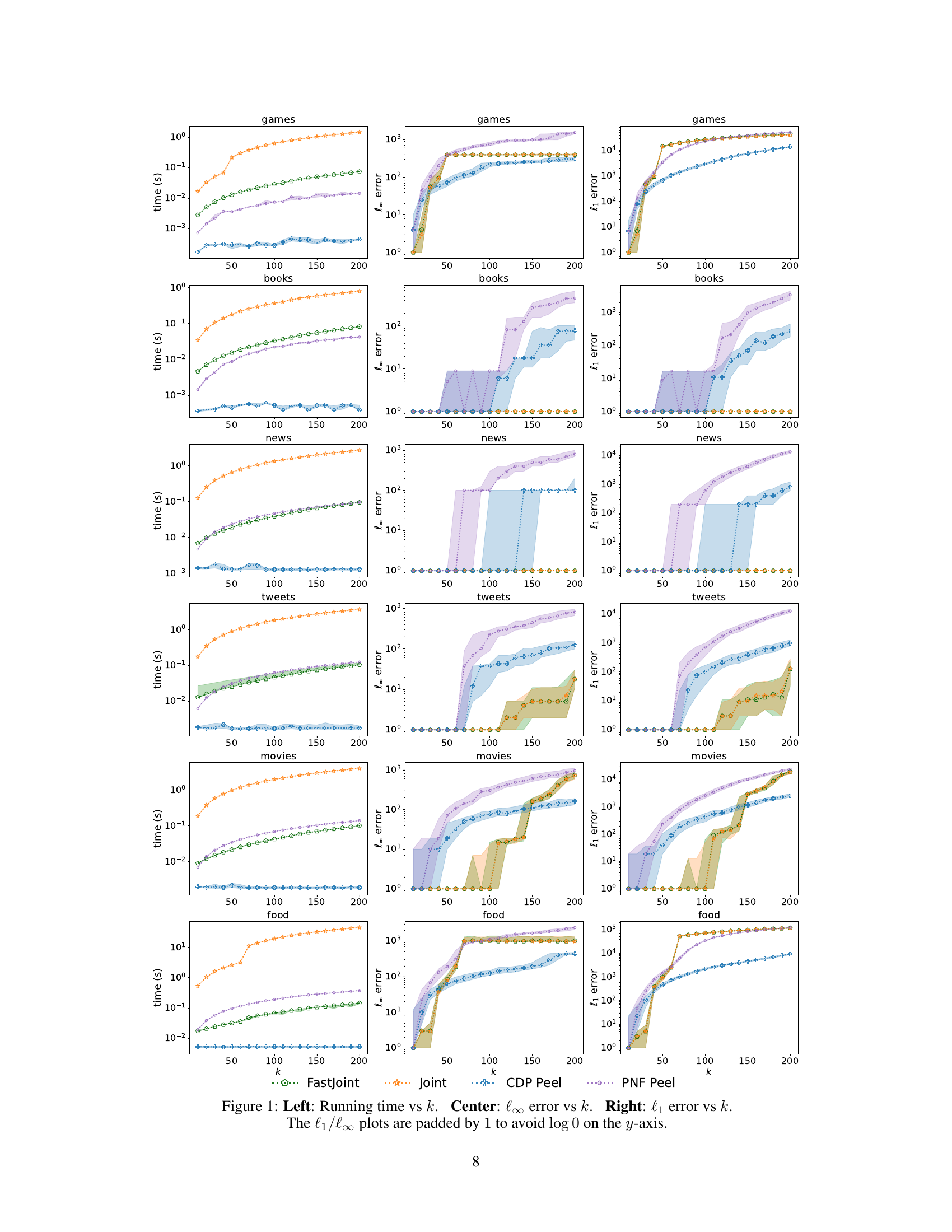

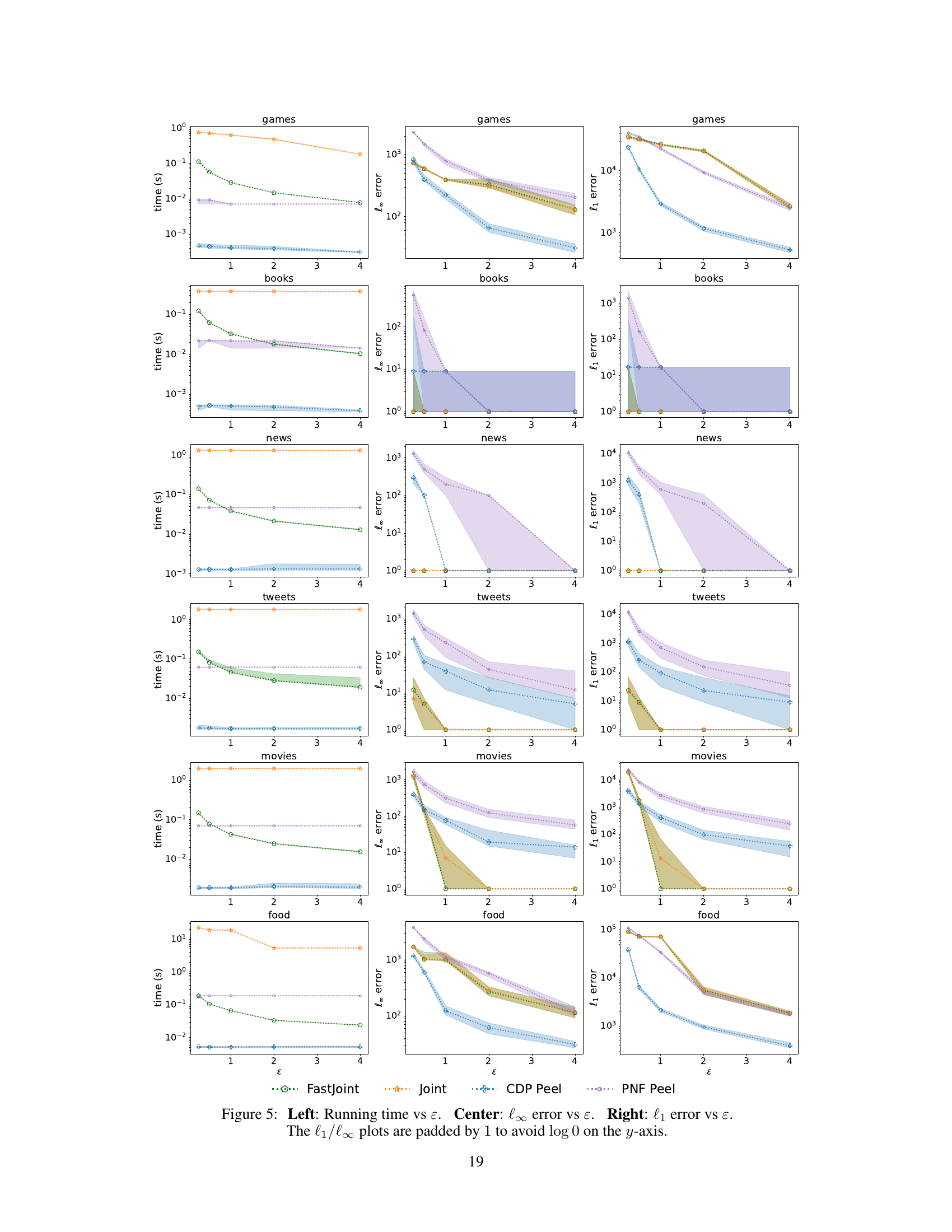

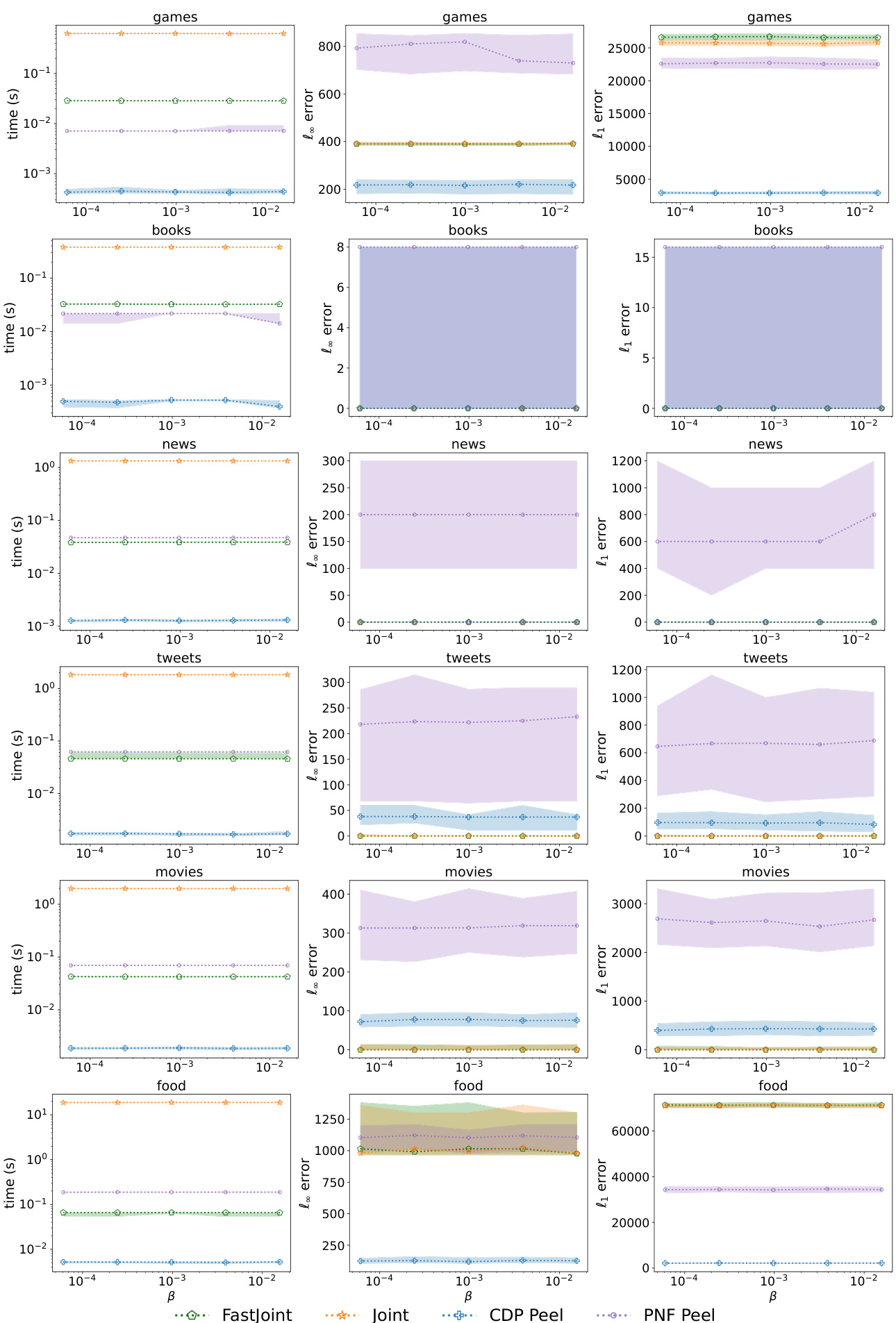

This figure compares four different algorithms (FastJoint, Joint, CDP-Peel, and PNF-Peel) across six different datasets (Games, Books, News, Tweets, Movies, and Food) in terms of their running time and error. The x-axis represents the value of k (number of top items to select), and the y-axis represents either the running time in seconds or the l∞ error or l₁ error. The l∞ error measures the maximum difference between the scores of selected items and the actual top-k items, and the l₁ error measures the sum of these differences. The plots show that FastJoint generally has the lowest running time while maintaining comparable accuracy to the Joint algorithm, which outperforms other algorithms in terms of accuracy.

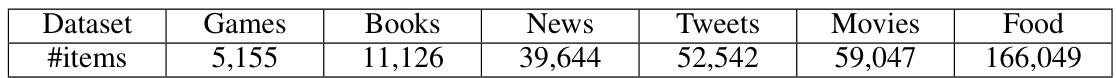

This table lists the six datasets used in the paper’s experiments, along with the number of items in each dataset. The datasets represent various domains, including games, books, news articles, tweets, movies, and food items, and vary significantly in size, from thousands to hundreds of thousands of items.

In-depth insights#

Joint Exp Mechanism#

The concept of a “Joint Exponential Mechanism” suggests a novel approach to differentially private top-k selection, potentially improving upon existing methods. It likely involves a mechanism that samples directly from the space of all possible length-k sequences rather than iteratively selecting items. This holistic approach could lead to better empirical accuracy as it avoids the potential compounding errors in iterative methods. However, directly sampling from the vast sequence space presents computational challenges, therefore efficient sampling strategies and pruning techniques are crucial for practical applicability. The “joint” aspect likely refers to the combined consideration of multiple items or scores when determining the utility function, allowing for a more sophisticated evaluation of the selected sequence rather than individual rankings.

Pruning for Speed#

A hypothetical section titled ‘Pruning for Speed’ in a differentially private top-k selection research paper would likely detail an algorithmic optimization strategy. The core idea would be to reduce computational cost by intelligently discarding less promising search paths or candidate solutions early in the process. This might involve techniques that prune the search space based on a threshold or probabilistic estimates of solution quality. Efficiency gains could be substantial, potentially reducing the runtime complexity from a super-linear dependence on the dataset size (d) to something closer to linear. The method would likely balance computational savings with maintaining sufficient accuracy; careful consideration of the privacy-preserving properties is paramount. Effectiveness would be measured by comparing the accuracy and running time of the pruned algorithm to unpruned versions. The section would likely also analyze the trade-off between speed and accuracy depending on various parameters, including the privacy budget (ε) and the desired number of top-k items (k).

Empirical Accuracy#

Empirical accuracy in a research paper refers to the real-world performance of a proposed method, algorithm, or model. It’s measured by evaluating the method’s output against ground truth or established baselines on real-world datasets. In contrast to theoretical accuracy, which is derived from mathematical analysis and often focuses on asymptotic behavior, empirical accuracy offers a practical assessment of effectiveness. A high empirical accuracy demonstrates that the approach performs well in practice, complementing theoretical results and providing crucial evidence of its usability and reliability. Factors influencing empirical accuracy include the choice of dataset, evaluation metrics, parameter settings, and experimental setup. A comprehensive evaluation typically involves multiple datasets, varied parameters, and multiple metrics to demonstrate robustness and generalizability. Reporting results with error bars or statistical significance tests is important to support the accuracy claims and quantify uncertainty. Discrepancies between theoretical and empirical accuracy can reveal important insights into the limitations and challenges of the method, potentially prompting further investigation and improvements.

Time & Space Complexity#

The research paper’s analysis of time and space complexity is crucial for understanding its practicality. The authors highlight a significant improvement by presenting an algorithm with a complexity of O(d + k²/ε ln d), contrasting with prior art’s O(dk) complexity. This improvement is particularly important for large datasets (large ’d’) where the difference becomes substantial. The asymptotic notation used helps reveal the scaling behavior, but concrete runtimes would be valuable for practical comparisons. Further investigation is warranted into the algorithm’s performance under various parameter settings (especially ‘k’ and ‘ε’) and dataset characteristics to fully validate the complexity claims. The discussion should also explore the trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency – does the improved speed come at a cost to precision? Finally, a deeper analysis of the algorithm’s memory usage, including constant factors hidden within the big-O notation, is needed for a complete picture of its space efficiency.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the algorithm to handle scenarios with significantly larger values of k, while maintaining efficiency, is a crucial next step. The current algorithm’s performance is highly dependent on the structure and gaps in the data; therefore, investigating and improving its robustness to various data distributions warrants further investigation. Another important direction is to develop more sophisticated pruning strategies to further accelerate the algorithm, perhaps utilizing adaptive pruning based on estimated error bounds. Finally, exploring the applicability of the joint exponential mechanism with pruning to other differentially private data analysis tasks beyond top-k selection, such as heavy hitters or frequent itemset mining, would be beneficial. This will offer a powerful and efficient approach to various privacy-preserving data analysis challenges.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares the performance of four differentially private top-k selection algorithms (FASTJOINT, JOINT, CDP-PEEL, and PNF-PEEL) across six real-world datasets. The left panel shows the running time of each algorithm as a function of k (the number of top items to select). The center and right panels display the l∞ error (maximum absolute error) and l₁ error (sum of absolute errors), respectively, also as functions of k. The plots show that FASTJOINT is significantly faster than JOINT while maintaining comparable accuracy. CDP-PEEL is faster than FASTJOINT but has slightly worse accuracy, and PNF-PEEL is the slowest and least accurate. Note that the y-axis is log-scaled.

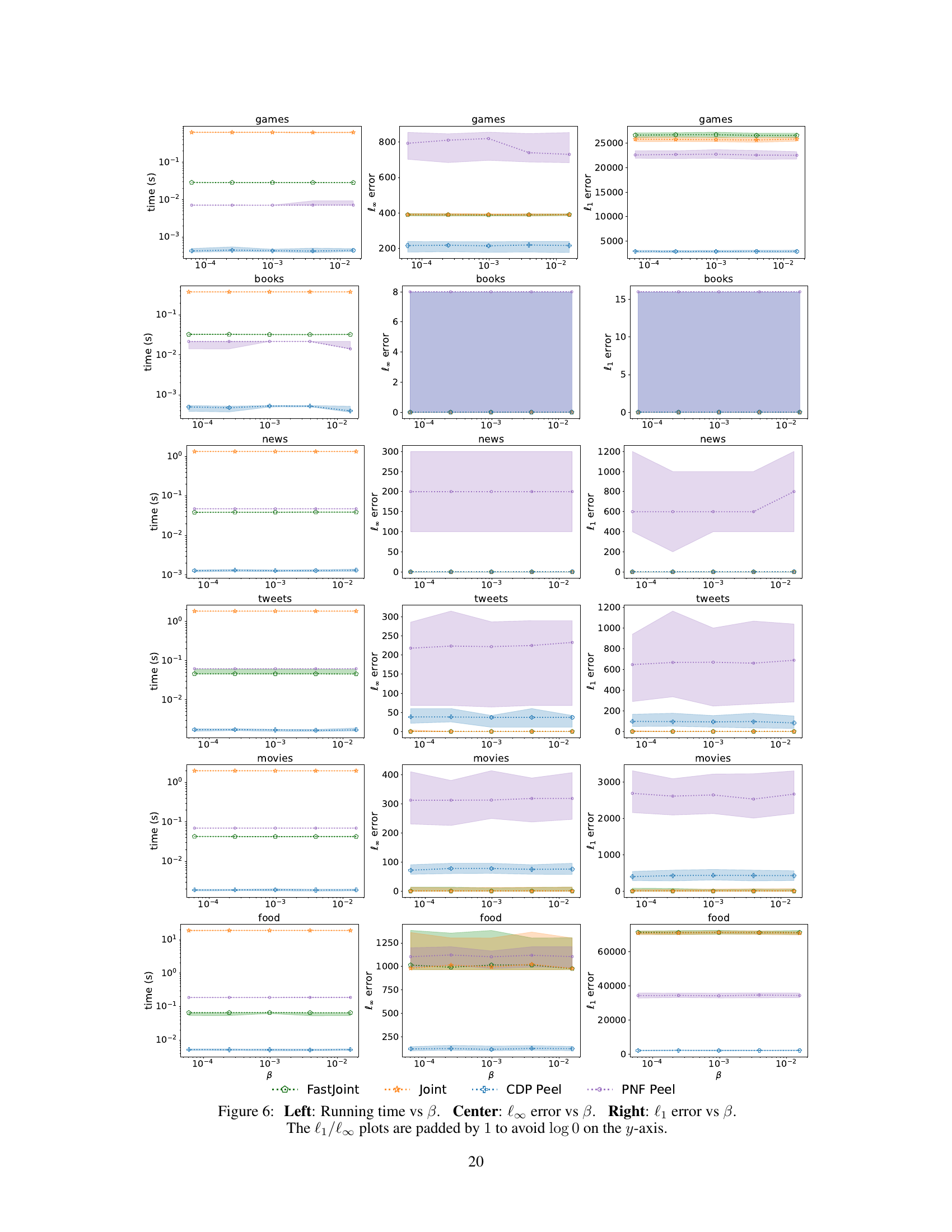

This figure shows the results of varying the beta (β) parameter in the FASTJOINT algorithm, which controls the tradeoff between accuracy and running time. The left panel shows running time, the center panel shows the l∞ error (maximum absolute error), and the right panel shows the l₁ error (sum of absolute errors). The plots demonstrate that the running time remains relatively stable across different β values while maintaining a comparable accuracy compared to the JOINT algorithm. The l∞ and l₁ error plots also show consistently low errors, suggesting that the accuracy is not overly sensitive to the β parameter. The y-axis padding of 1 is applied to avoid taking the logarithm of 0.

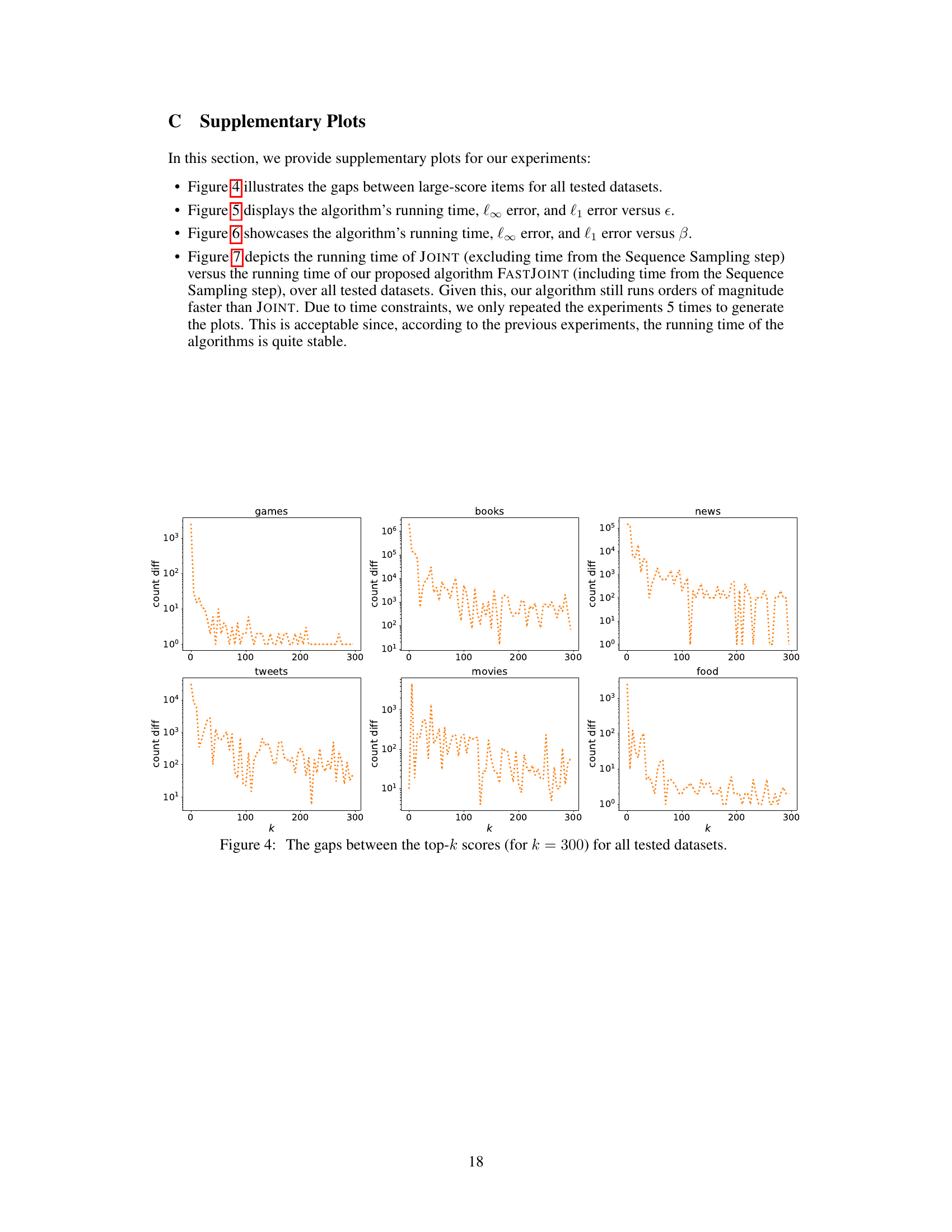

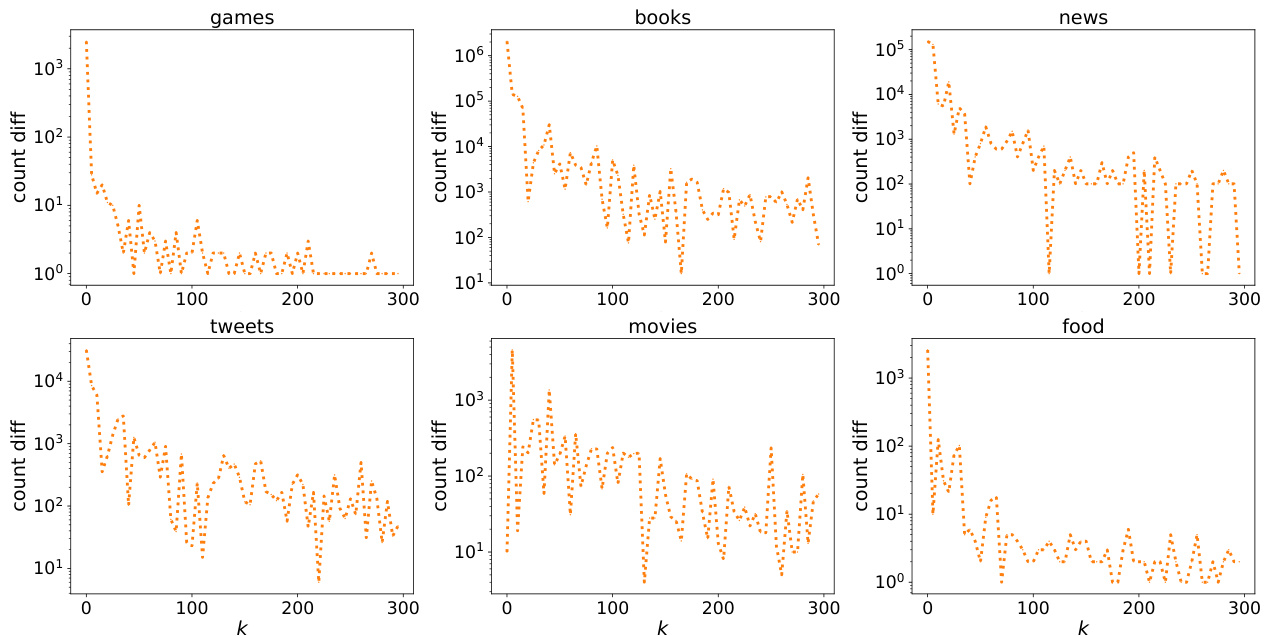

This figure shows the differences between the scores of the top 300 items for six different datasets. The x-axis represents the rank (k from 1 to 300) and the y-axis shows the difference in scores between consecutive items (count diff). The datasets are Games, Books, News, Tweets, Movies, and Food. The plots illustrate the distribution of score gaps within each dataset, highlighting the variations in data characteristics.

This figure compares the performance of four algorithms (FastJoint, Joint, CDP-Peel, and PNF-Peel) across six different datasets. The left panel shows the running time of each algorithm as a function of k (the number of top items to select). The center and right panels display the l∞ error and l₁ error, respectively, also as a function of k. The padding of 1 in the l₁/l∞ plots is to handle potential log(0) errors on the y-axis.

This figure shows the results of experiments varying the privacy parameter epsilon (ɛ). It displays three key metrics across six different datasets: running time, l∞ error (maximum absolute difference between true and estimated top-k scores), and l₁ error (sum of absolute differences between true and estimated top-k scores). The plots illustrate how these metrics change as ɛ increases, providing insights into the algorithm’s performance trade-offs between efficiency and accuracy.

This figure compares the performance of four different algorithms (FASTJOINT, JOINT, CDP-PEEL, and PNF-PEEL) for differentially private top-k selection across six different datasets (Games, Books, News, Tweets, Movies, Food) with varying values of k. The left panel shows the running time, the center panel shows the l∞ error, and the right panel shows the l₁ error. The results demonstrate that FASTJOINT significantly outperforms JOINT in terms of running time while maintaining comparable accuracy. CDP-PEEL is generally faster than FASTJOINT, while PNF-PEEL’s accuracy is lower.

Full paper#