↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional dataflow analysis techniques rely on successful compilation and expert customization, limiting their applicability and usability for uncompilable or evolving programs. This creates a critical need for more flexible and adaptable approaches that can effectively handle the complexities of real-world code analysis and address evolving analysis needs. The inherent limitations of traditional methods have hindered progress in areas such as on-the-fly code flaw analysis within Integrated Development Environments (IDEs).

LLMDFA addresses these challenges by leveraging the power of Large Language Models (LLMs). It presents a compilation-free and customizable dataflow analysis framework. The method decomposes the problem into subtasks (source/sink extraction, dataflow summarization, path feasibility validation), using LLMs to synthesize code that outsources intricate reasoning to external expert tools (parsing libraries, SMT solvers). Few-shot chain-of-thought prompting enhances accuracy by aligning LLMs with program semantics. Evaluations on synthetic programs and real-world Android applications show LLMDFA achieves high precision and recall, surpassing existing techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers because it introduces a novel, LLM-powered framework for dataflow analysis that overcomes limitations of traditional methods. Its compilation-free and customizable nature expands the applicability of dataflow analysis to a wider range of scenarios, including incomplete and evolving programs. The use of LLMs for code understanding and automated tool synthesis opens exciting avenues for future research in program analysis and bug detection.

Visual Insights#

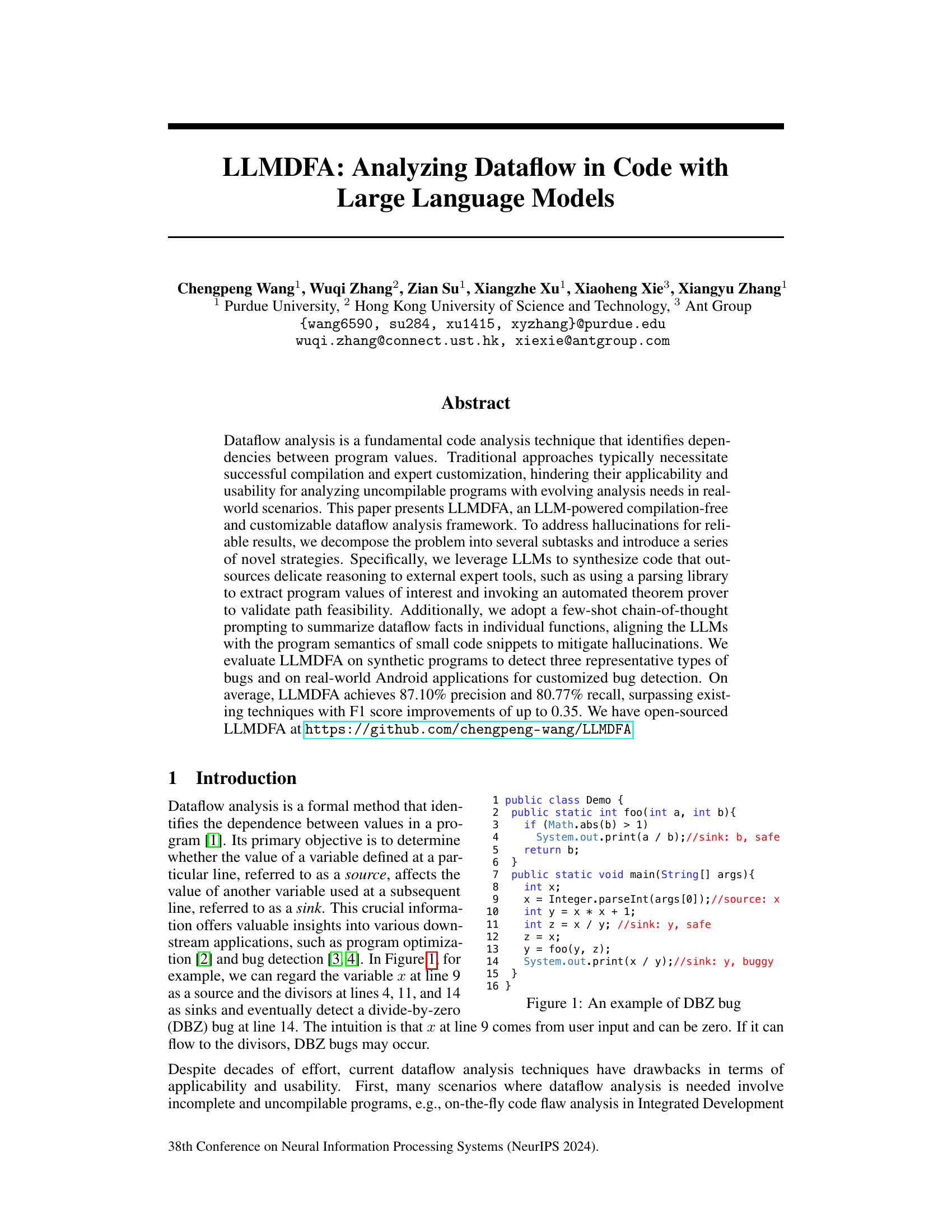

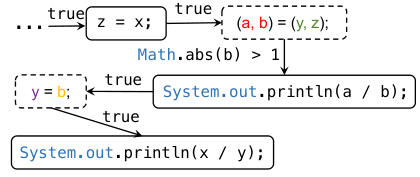

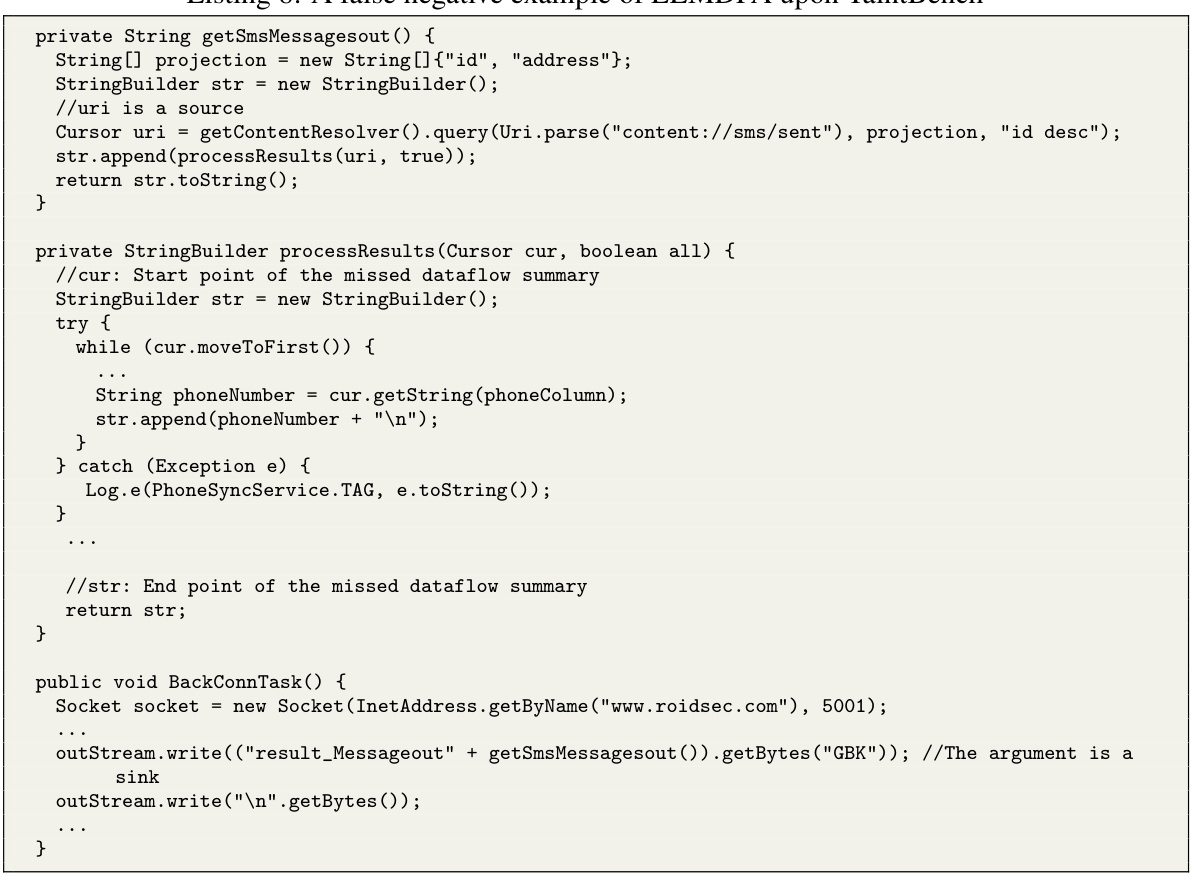

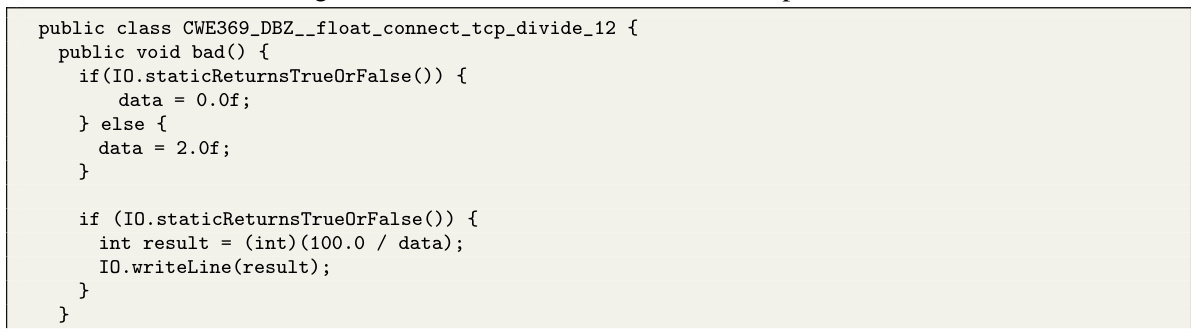

This figure shows a Java program with a potential divide-by-zero (DBZ) bug. The variable

xat line 9 is identified as a source, potentially receiving a zero value from user input. Variablesbat line 4 andyat lines 11 and 14 are sinks because they are used as divisors. The program demonstrates how a zero value from the source could lead to a DBZ error at line 14 if the flow of the variablexis not carefully handled. The safe and buggy instances show the context of the vulnerability.

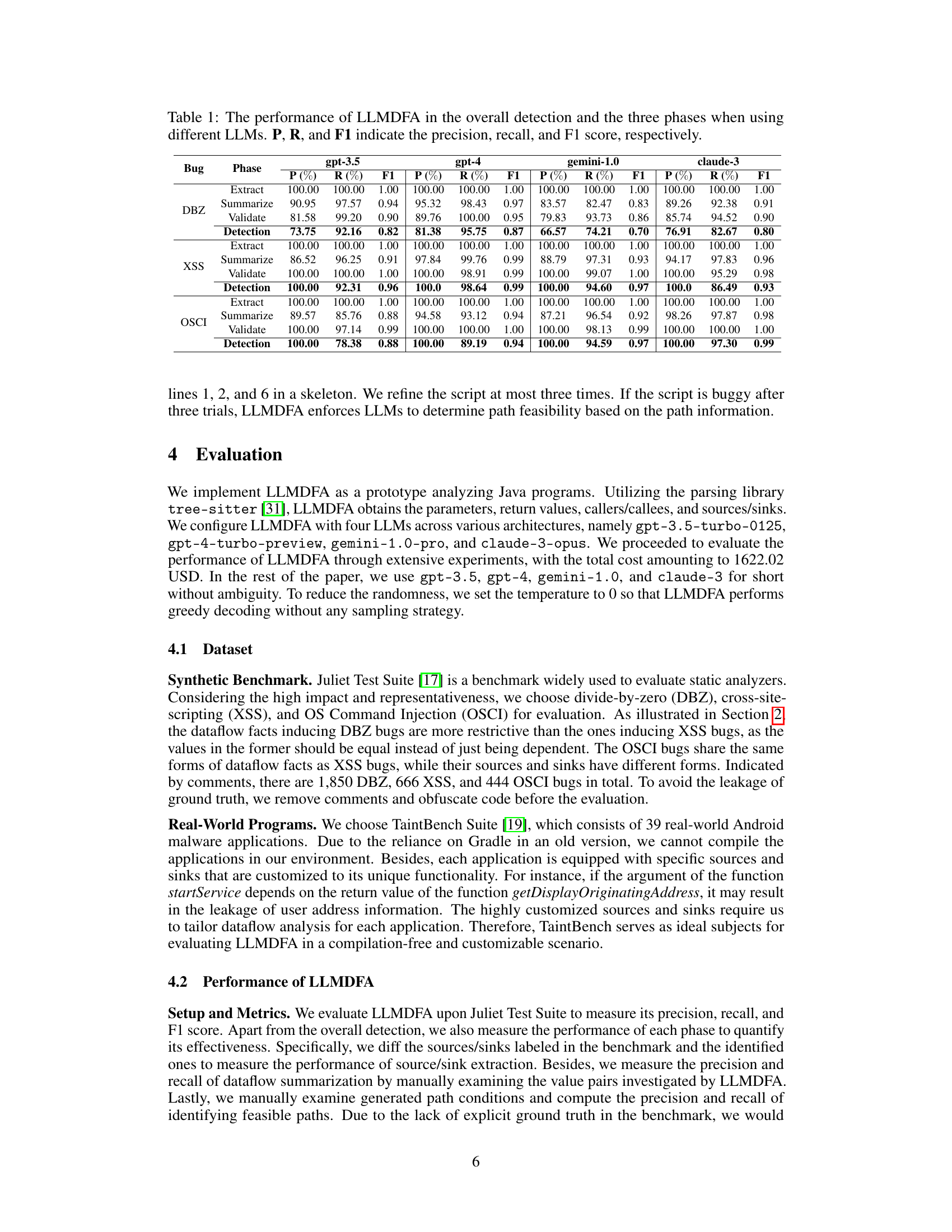

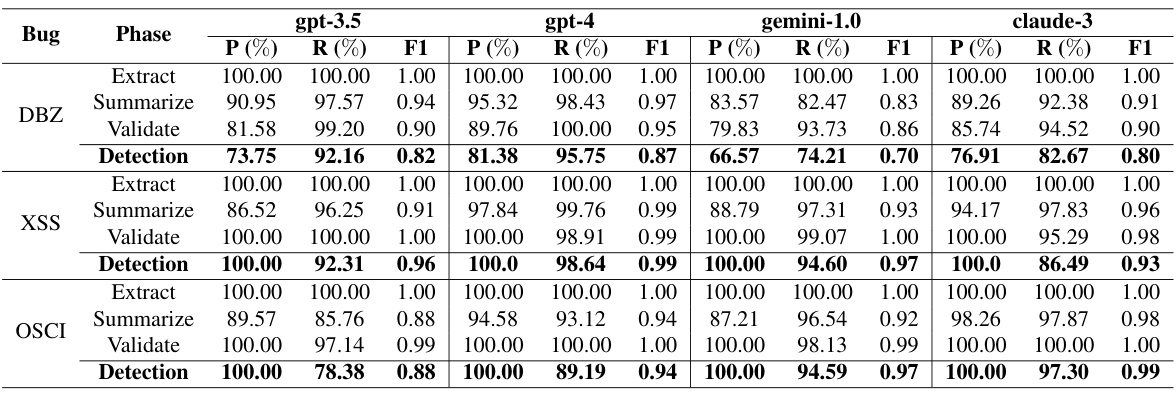

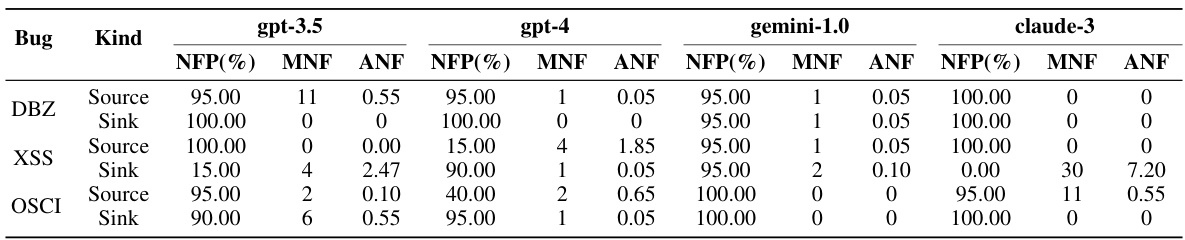

This table presents the performance results of LLMDFA across different phases (extraction, summarization, validation) and overall detection for three bug types (DBZ, XSS, OSCI) using four different LLMs (gpt-3.5, gpt-4, gemini-1.0, claude-3). It shows the precision, recall, and F1-score for each LLM and phase, providing a comprehensive view of LLMDFA’s performance.

In-depth insights#

LLM-powered DFA#

LLM-powered Data Flow Analysis (DFA) represents a significant paradigm shift in software analysis. Traditional DFA methods heavily rely on compilation, limiting their applicability to incomplete or uncompilable code. LLM-powered DFA bypasses this limitation by directly analyzing the source code, leveraging the power of Large Language Models (LLMs) to understand program semantics and identify data dependencies without the need for compilation. This opens up new possibilities for analyzing codebases in dynamic environments such as IDEs, where code is constantly evolving. However, hallucinations, a common issue with LLMs, pose a significant challenge. To address this, robust strategies are needed to ensure reliable results. This might involve decomposing the problem into smaller, more manageable subtasks (like source/sink identification and path feasibility validation), using LLMs to synthesize code that leverages external tools for precise reasoning (e.g., automated theorem provers), and employing techniques like few-shot prompting to align the LLMs more closely with program semantics. The success of LLM-powered DFA will ultimately depend on the ability to mitigate these inherent LLM limitations, creating a reliable and accurate system for a wide range of applications.

Hallucination Mitigation#

The core of this research lies in addressing the challenges posed by Large Language Models (LLMs) in dataflow analysis, specifically their propensity for hallucinations. The authors creatively tackle this issue through a three-phased approach: Source/Sink Extraction, Dataflow Summarization, and Path Feasibility Validation. Each phase incorporates strategies to mitigate inaccuracies. In Source/Sink extraction, LLMs synthesize scripts leveraging external parsing libraries, outsourcing the delicate task of identifying program values. This reduces reliance on the LLM’s inherent reasoning capabilities for this crucial step, thereby minimizing erroneous results. Dataflow Summarization leverages few-shot chain-of-thought prompting to align the LLM’s understanding with program semantics. Finally, Path Feasibility Validation employs LLMs to synthesize scripts that use external SMT solvers for validating the feasibility of identified dataflow paths, rather than relying solely on LLM’s potentially unreliable logical reasoning. This multi-pronged strategy, decomposing the problem into smaller, more manageable subtasks and using external tools, proves highly effective in mitigating the risk of hallucinations, leading to a more robust and reliable dataflow analysis framework.

Phase-Based Analysis#

A phase-based approach to analysis is a powerful strategy for tackling complex problems by breaking them down into smaller, more manageable steps. Each phase focuses on a specific aspect of the problem, allowing for focused attention and the application of specialized techniques. This methodical process enhances accuracy, reduces the risk of errors, and facilitates a deeper understanding of the overall problem. Well-defined phases improve the transparency and reproducibility of the analysis, making it easier to validate results and ensure consistency. A crucial aspect is establishing clear criteria for transitioning between phases, providing a structured workflow. Effective communication between phases is also critical to ensuring that insights from one phase inform the subsequent phases. By carefully planning the sequencing of the phases, one can optimize the analysis workflow for maximum efficiency and effectiveness. A critical benefit of using a phase-based analysis is its adaptability to various problem contexts, as the specific tasks of each phase can be customized based on the analysis goals. This makes it a versatile method for addressing a range of challenges. Finally, a phase-based approach enhances the overall interpretability of the analysis, producing a more coherent and easily understood narrative of the findings.

Benchmark Results#

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section in a research paper would ideally present a detailed comparison of the proposed method against existing state-of-the-art techniques. This would involve selecting relevant and publicly available benchmarks, ensuring that the chosen benchmarks appropriately reflect the problem’s complexity and scale. Quantitative metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, accuracy, and efficiency (e.g., execution time) would be crucial for a fair and comprehensive evaluation. Furthermore, statistical significance testing should be performed to support claims of performance improvements. The discussion should not only focus on the overall performance, but also on specific aspects, especially in scenarios where the proposed method excels or underperforms. Presenting results visually (e.g., using tables and graphs) can aid readers in understanding the performance differences. In addition, it is vital to provide a thorough explanation of any discrepancies observed, suggesting possible reasons for performance variations. A robust benchmark analysis strengthens the research paper’s credibility and offers valuable insights into the proposed method’s strengths and limitations.

Future Extensions#

Future extensions for this research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency of LLM interaction is crucial; reducing prompt lengths and developing more efficient prompting strategies would significantly enhance performance and cost-effectiveness. Expanding the range of supported programming languages beyond Java and exploring the integration of LLMDFA within existing IDEs would enhance usability and practicality. Addressing the challenges of handling complex code structures and large codebases remains a key area for improvement. Investigating the applicability of LLMDFA to other code analysis tasks such as vulnerability detection beyond the three types examined (DBZ, XSS, and OSCI) is warranted. Finally, a formal analysis of LLMDFA’s limitations, along with a detailed examination of potential biases in the LLMs’ outputs, would significantly strengthen the research’s robustness and provide a deeper understanding of its capabilities and its scope.

More visual insights#

More on figures

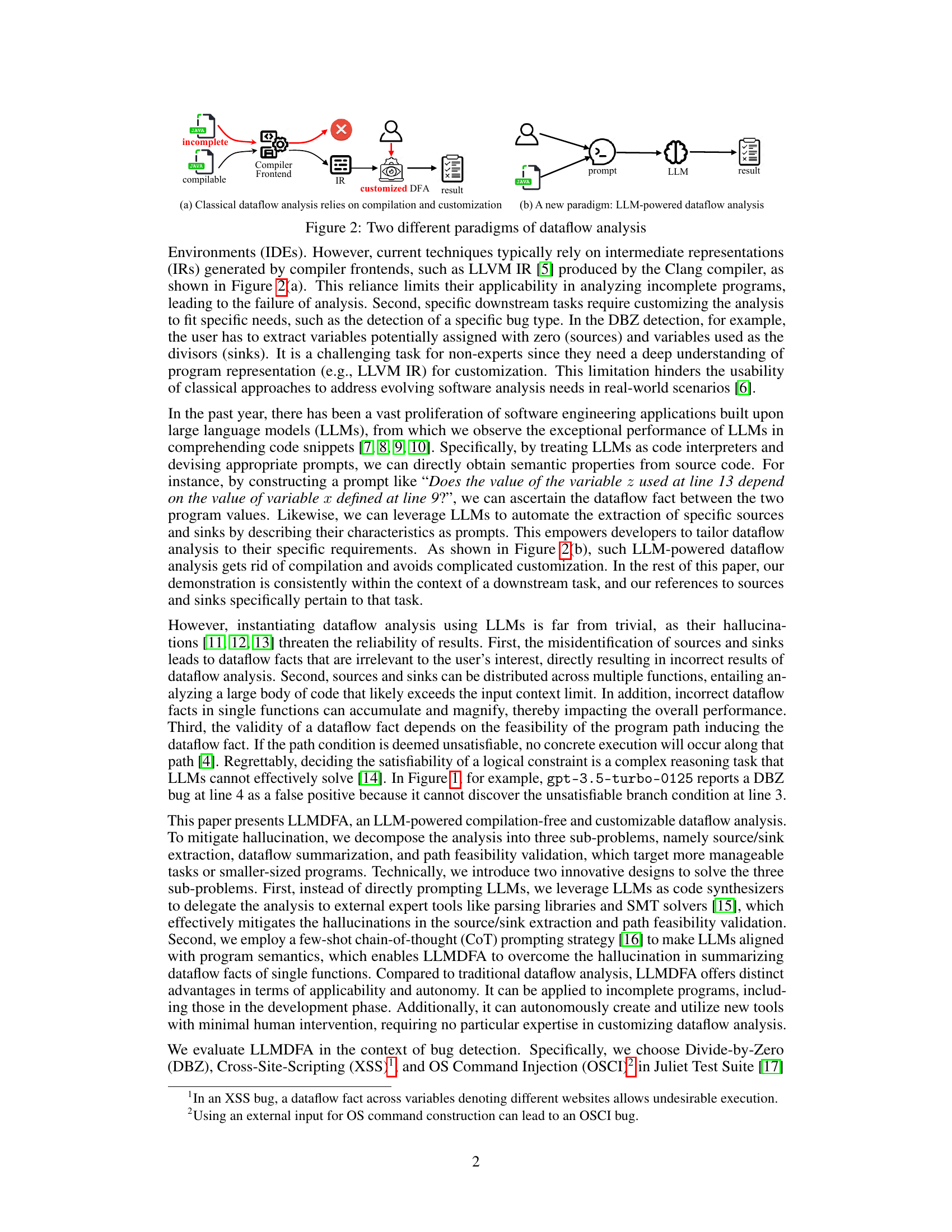

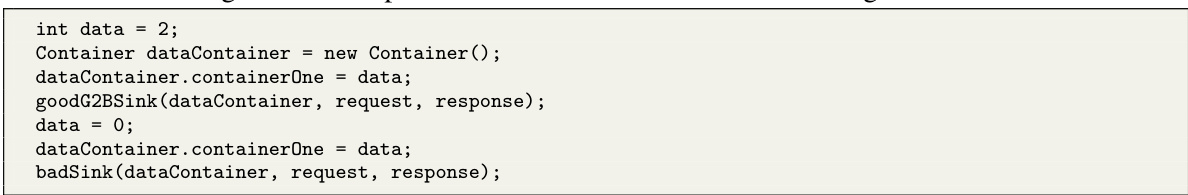

This figure compares classical dataflow analysis with the proposed LLM-powered approach. Classical dataflow analysis (left) relies on compilation and requires customization by experts for specific analysis needs. The intermediate representation (IR) generated by the compiler is used in the analysis, which limits its applicability to incomplete programs. The LLM-powered method (right) is compilation-free. It directly analyzes the source code and can be customized by the user through prompts, making it more flexible and applicable to real-world scenarios. The LLM synthesizes code that outsources tasks to external tools, leading to more reliable and robust analysis.

This figure shows a partial CFG (Control Flow Graph) of the Java program example in Figure 1. The CFG visually represents the flow of control within the program, showing the sequence of statements executed and the conditions that govern those transitions. It highlights aspects like branch conditions (e.g.,

Math.abs(b) > 1), function calls (shown with dashed boxes representing argument passing and return value), and assignments. The dashed boxes represent the data flowing from arguments to parameters and from the function’s return value to the program’s output value. This illustrative CFG helps to understand how program values propagate, which is fundamental to dataflow analysis.

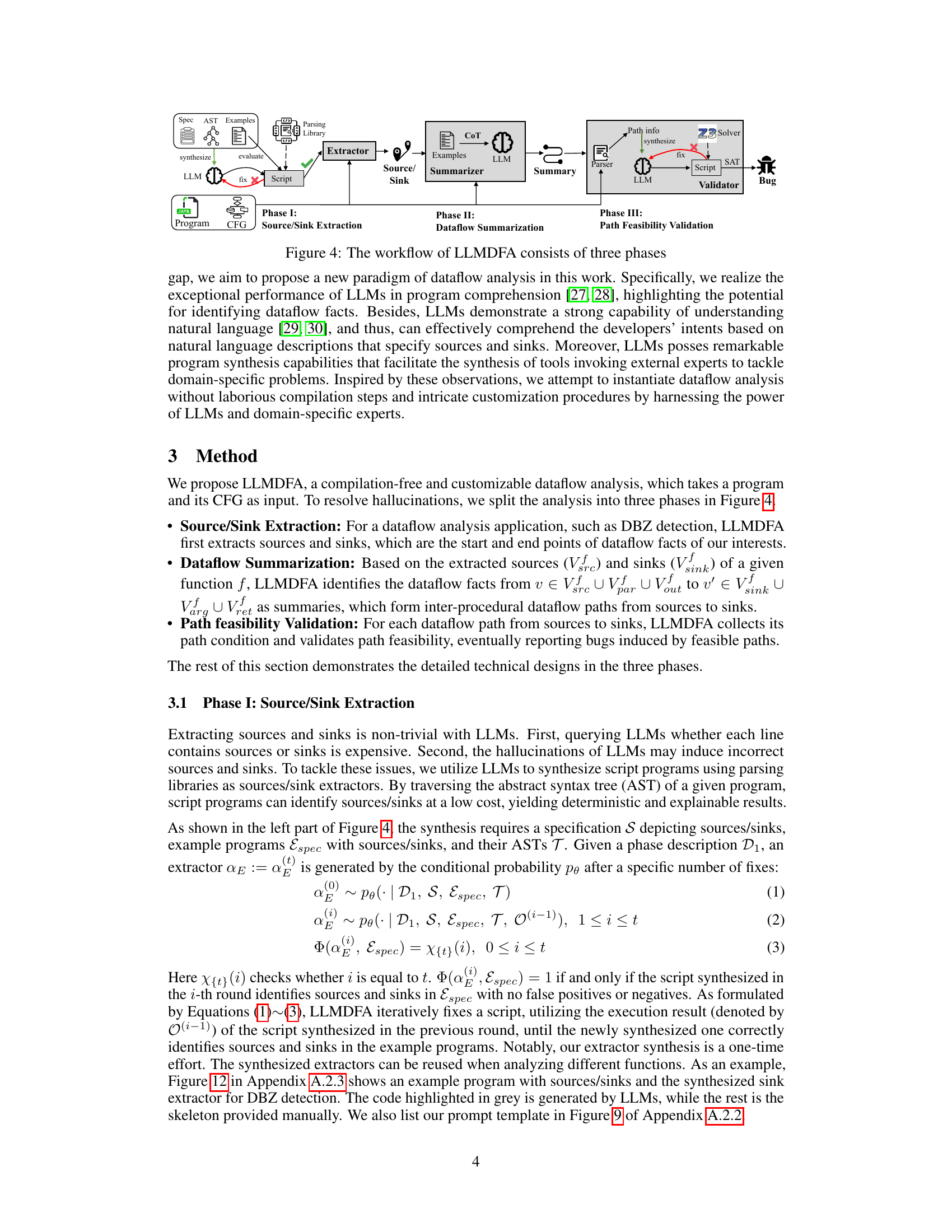

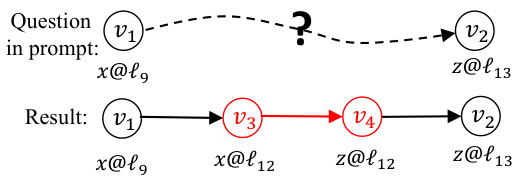

The workflow of LLMDFA is divided into three phases: Source/Sink Extraction, Dataflow Summarization, and Path Feasibility Validation. In the first phase, LLMs synthesize scripts leveraging parsing libraries to extract sources and sinks from the program’s Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). The second phase employs few-shot chain-of-thought prompting to summarize dataflow facts within individual functions. The third phase leverages LLMs to synthesize Python scripts that invoke Z3 solver to validate the feasibility of discovered dataflow paths. Each phase helps mitigate the hallucinations of LLMs, improving the accuracy and reliability of the dataflow analysis.

This figure illustrates how the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting method helps LLMs reason step by step to discover dataflow facts. It depicts a query asking whether there is a dataflow between variable x at line 9 and variable z at line 13. The LLM’s response indicates a positive dataflow, showing the intermediate variables x@l12 and z@l12 that form the path between the initial variables. This demonstrates the CoT’s effectiveness in summarizing and explaining the dataflow path.

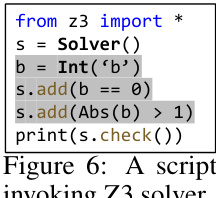

This figure shows a short Python script that uses the Z3 solver to check the satisfiability of a constraint. The constraint,

Abs(b) > 1andb == 0, is clearly unsatisfiable; however, the script demonstrates how LLMDFA uses external tools to validate path feasibility and avoid hallucinations. LLMs generate this type of script to outsource complex reasoning tasks to more reliable tools.

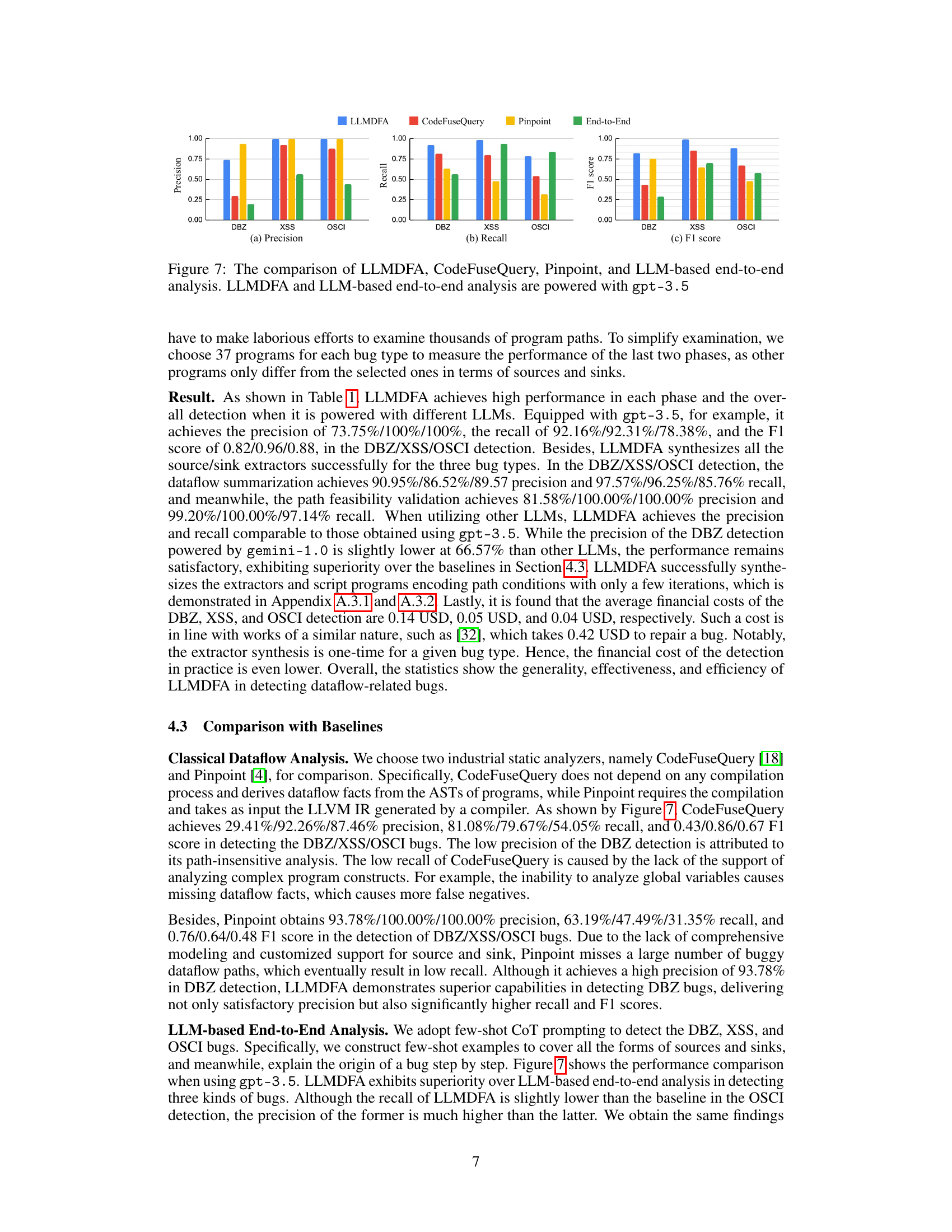

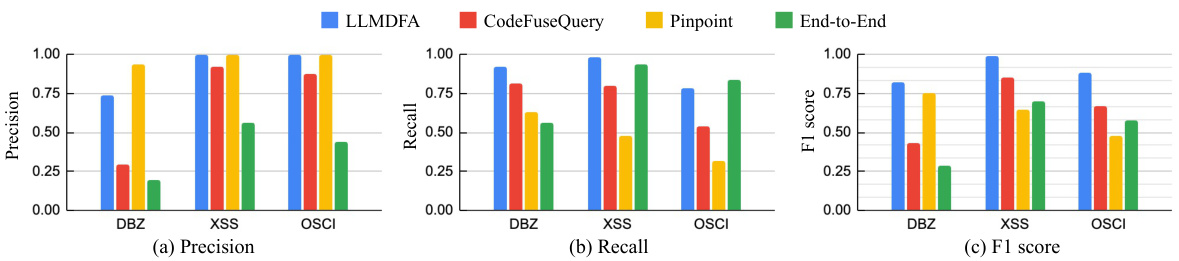

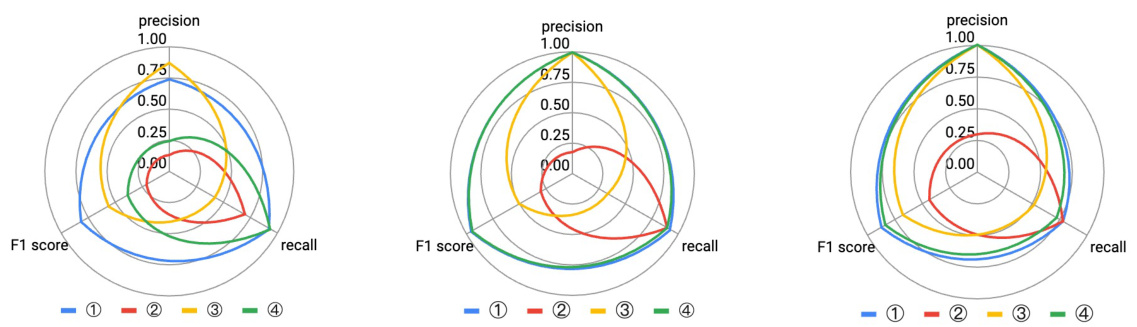

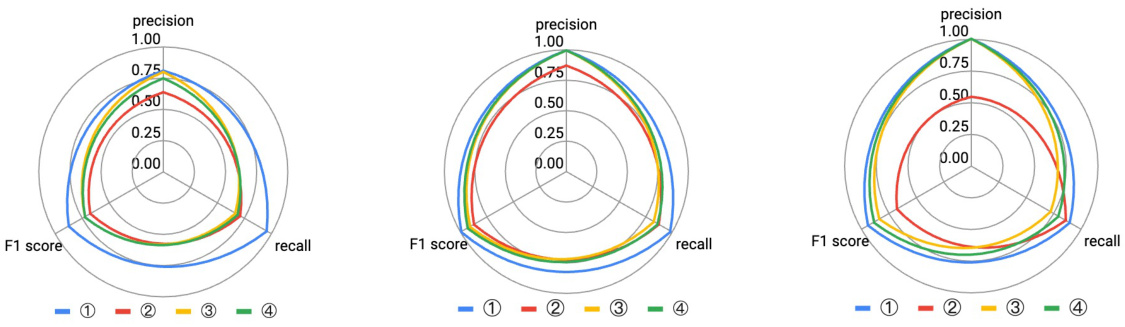

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA with three other methods for detecting three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, and OSCI) in terms of precision, recall, and F1 score. LLMDFA and an end-to-end LLM-based approach both utilize gpt-3.5. The other two methods are CodeFuseQuery and Pinpoint, representing more traditional static analysis techniques. The chart visually demonstrates LLMDFA’s superiority in terms of overall performance across all three bug types.

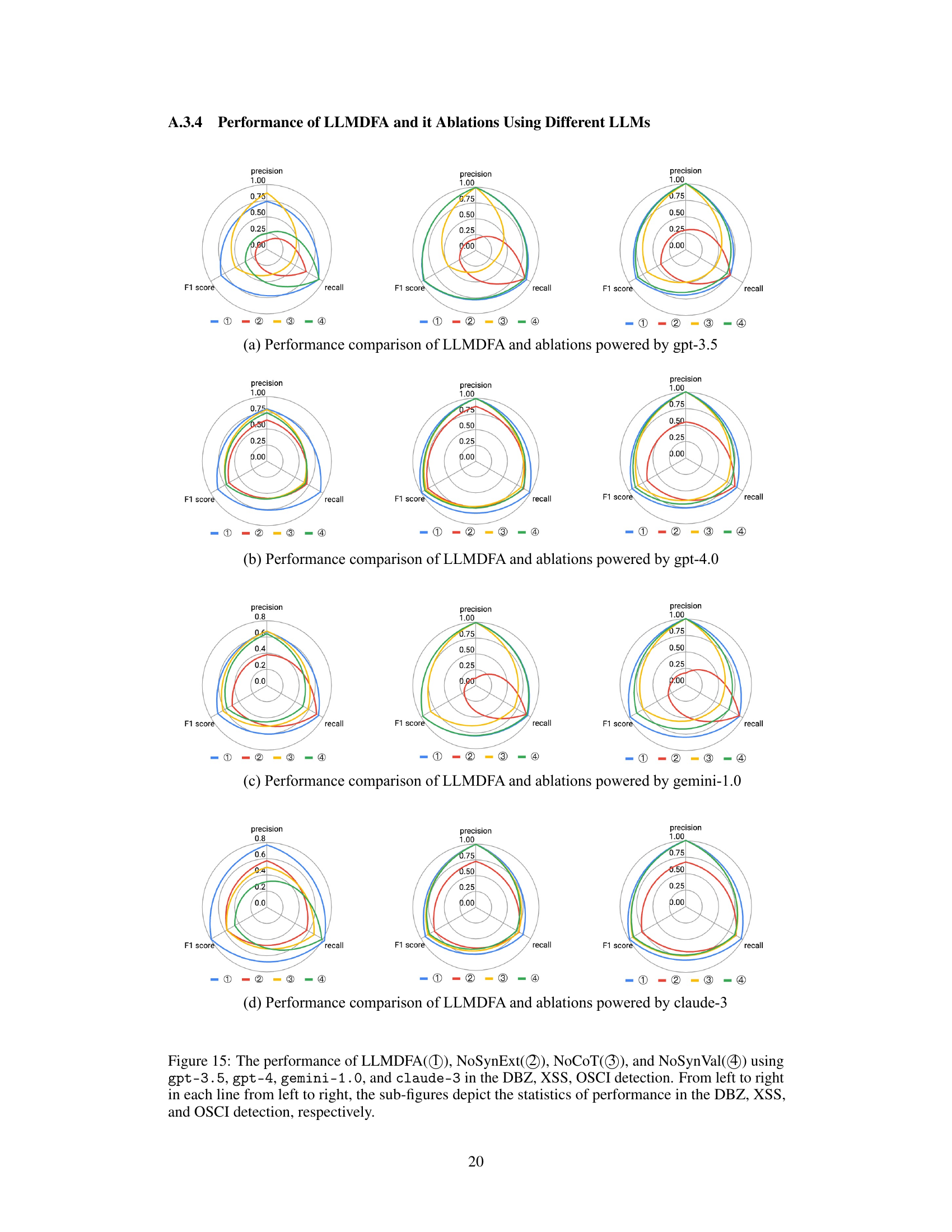

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA with three ablation studies: NoSynExt (no synthesized extractors), NoCoT (no chain-of-thought prompting), and NoSynVal (no synthesized validation scripts). The results are shown separately for DBZ, XSS, and OSCI bug detection, illustrating the impact of each component on precision, recall, and F1 score. The radar chart format facilitates a visual comparison of the different methods across these three metrics.

This figure shows an example of how Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting is used in LLMDFA to summarize dataflow facts. The prompt asks if there is a dataflow from variable x at line 9 to variable z at line 13. The LLM’s response, facilitated by CoT, breaks down the dataflow path into intermediate steps (x@l9 → x@l12 and z@l12 → z@l13), eventually confirming the dataflow fact x@l9 → z@l13. This demonstrates how CoT helps LLMs align with program semantics and reduce hallucinations.

The workflow of LLMDFA is decomposed into three phases: Source/Sink Extraction, Dataflow Summarization, and Path Feasibility Validation. In the first phase, LLMs synthesize scripts that use parsing libraries to extract sources and sinks from the program’s Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). The second phase uses few-shot chain-of-thought prompting to summarize dataflow facts in individual functions. Finally, the third phase leverages LLMs to generate Python scripts that utilize Z3 solver to validate the feasibility of program paths, mitigating hallucinations and ensuring reliable analysis results.

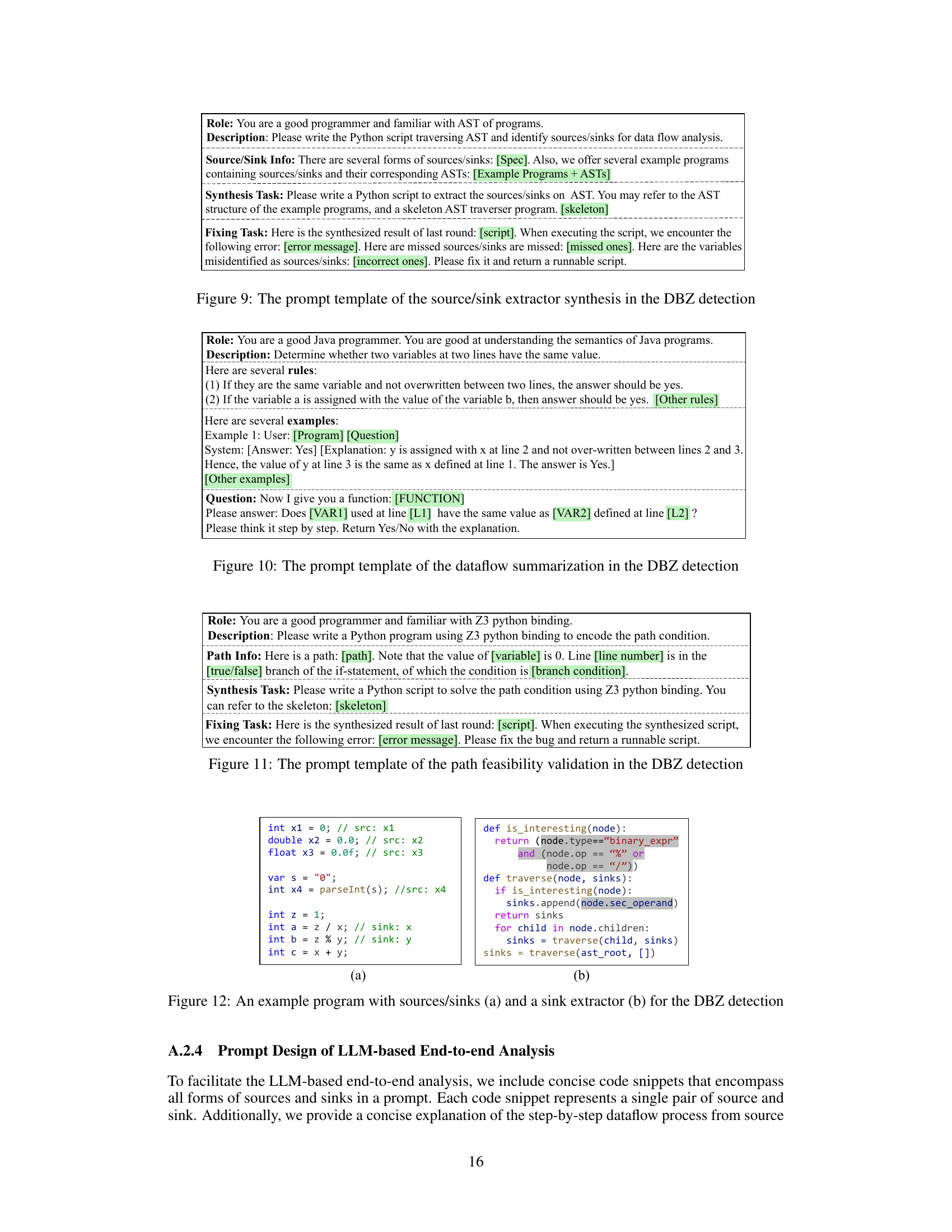

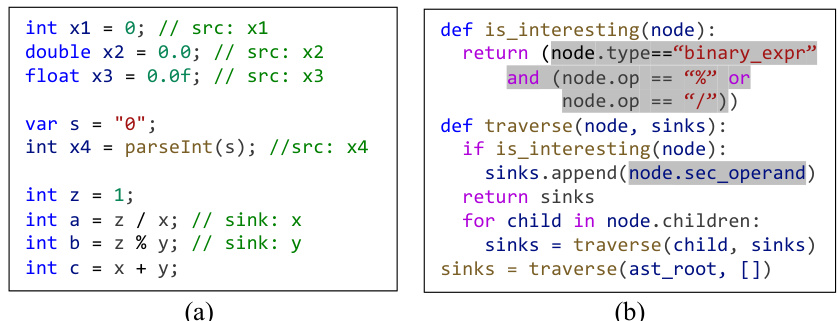

This figure shows an example program with identified sources and sinks for divide-by-zero bug detection. Part (a) displays the Java code snippet illustrating various source variables (x1, x2, x3, x4) which can potentially lead to zero values, along with a sink variable (x) used as a divisor. Part (b) presents the Python code for a sink extractor. The sink extractor, automatically generated by LLMs, traverses the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) of the program and identifies sinks (variables used in division or modulo operations). This demonstrates how LLMs are utilized in LLMDFA for automated source/sink extraction.

This figure shows the number of times the Python scripts synthesized by LLMDFA for path feasibility validation needed to be fixed before successfully encoding the path conditions correctly. The results are broken down by the specific bug type (DBZ, XSS, OSCI) and the LLM used (gpt-3.5, gpt-4, gemini-1.0, claude-3). It illustrates the number of paths where no fixes were needed (#Fix = 0), one fix (#Fix = 1), two fixes (#Fix = 2), three fixes (#Fix = 3), or where the system ultimately fell back to using the LLM directly (#Using LLM).

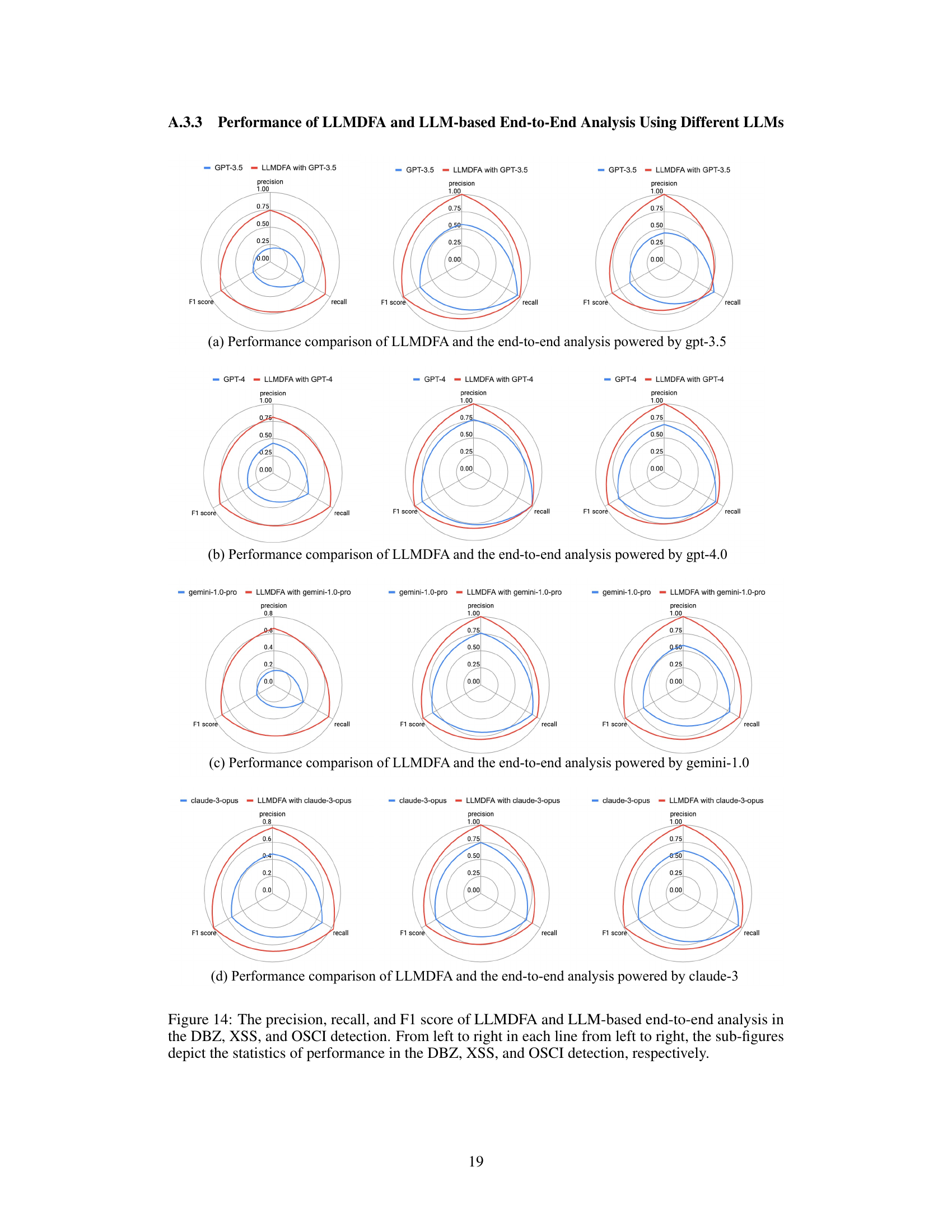

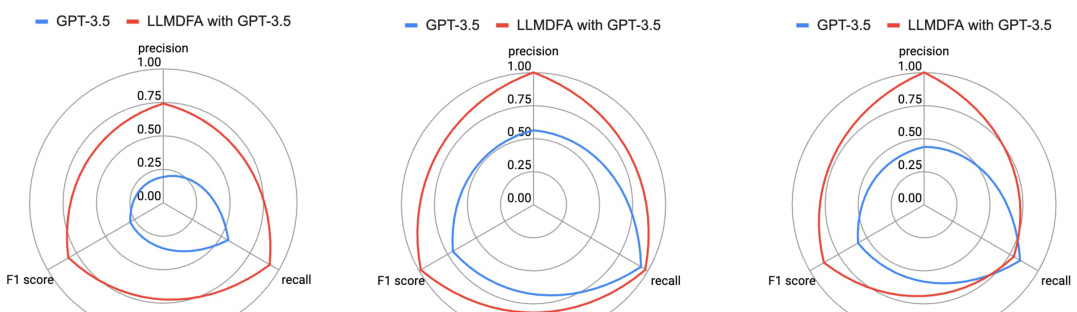

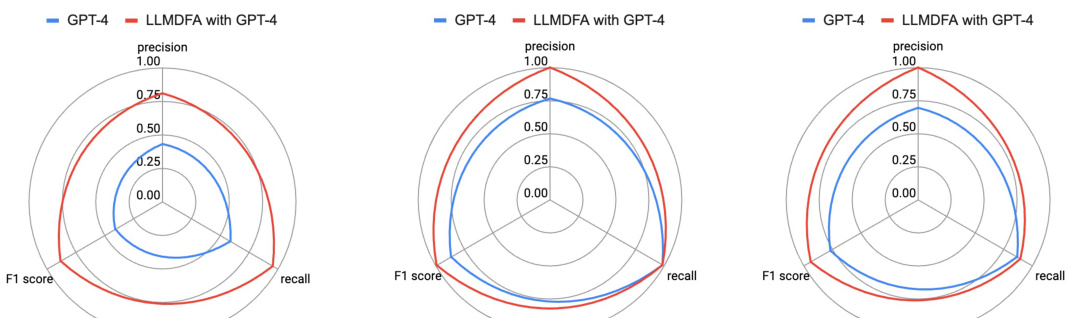

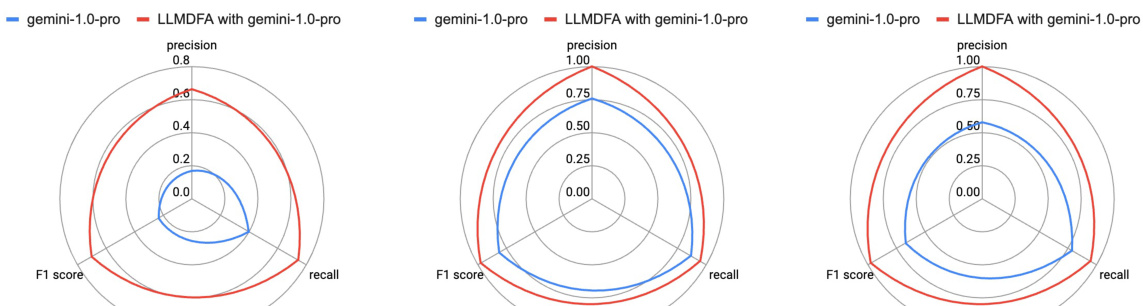

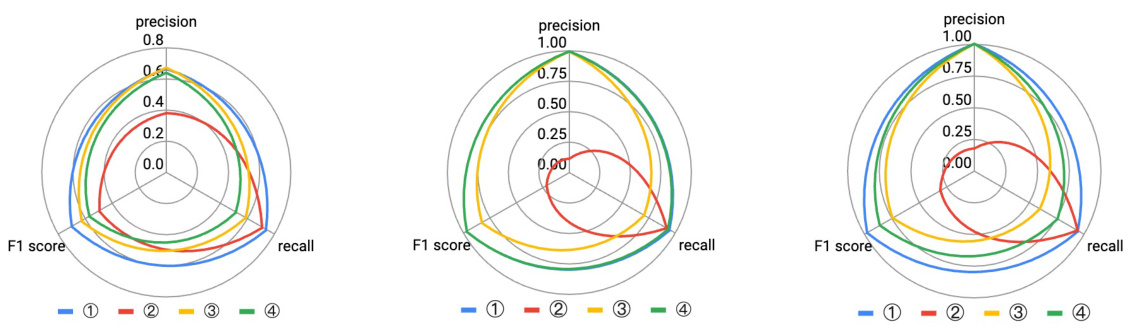

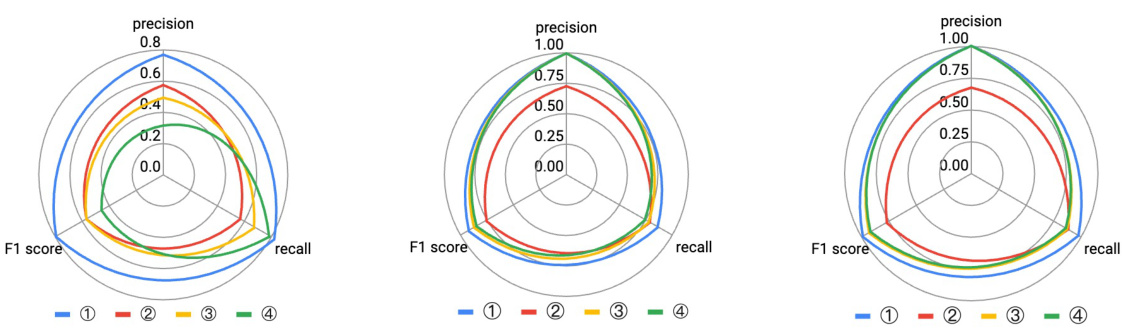

This figure presents a comparison of the performance of LLMDFA and a baseline LLM-based end-to-end analysis method across three different bug types: Divide-by-Zero (DBZ), Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), and OS Command Injection (OSCI). The comparison is shown using radar charts that visualize the precision, recall, and F1-score for each method and bug type. Each chart shows the relative strengths and weaknesses of each approach in terms of identifying these specific types of bugs. The figure allows for a visual assessment of how LLMDFA performs compared to the baseline, highlighting its superior performance in several instances.

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA against three other methods for detecting bugs: CodeFuseQuery, Pinpoint, and an LLM-based end-to-end approach. It shows precision, recall, and F1 score for three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, and OSCI). LLMDFA demonstrates higher overall performance across all metrics, indicating that it’s better at accurately identifying bugs and avoiding false positives or negatives.

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA and a baseline LLM-based end-to-end approach across three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, and OSCI). It uses radar charts to visualize the precision, recall, and F1 score for each method and bug type. The results show LLMDFA generally outperforming the baseline approach in terms of precision, recall, and F1 score for all bug types. Note that each small radar chart represents a different bug type.

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA and a baseline LLM-based end-to-end approach across three different bug types: Divide-by-Zero (DBZ), Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), and OS Command Injection (OSCI). The radar charts show precision, recall, and F1-score for each method and bug type. It allows for a visual comparison of the two approaches’ effectiveness in detecting these types of vulnerabilities.

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA with three other methods for detecting three types of bugs: Divide-by-Zero (DBZ), Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), and OS Command Injection (OSCI). The three other methods are CodeFuseQuery (a classical dataflow analyzer), Pinpoint (another classical dataflow analyzer), and an LLM-based end-to-end approach. The comparison is done in terms of precision, recall, and F1-score for each bug type and each method. The figure clearly shows that LLMDFA significantly outperforms the other three methods in almost all cases.

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA with three ablation studies (NoSynExt, NoCoT, and NoSynVal) using the gpt-3.5 language model. Each ablation represents a modification to the LLMDFA approach, removing a key component (source/sink extraction, few-shot chain-of-thought prompting, or path feasibility validation). The radar charts visualize the precision, recall, and F1 score for each method across three types of bugs: DBZ, XSS, and OSCI. This illustrates the impact of each component on the overall performance of the dataflow analysis.

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA and its three ablation models (NoSynExt, NoCoT, NoSynVal) across three different bug types (DBZ, XSS, OSCI). Each ablation removes a key component of LLMDFA’s design to isolate its impact on overall performance. The results, presented as radar charts, show precision, recall, and F1-score for each model and bug type. This allows for a quantitative assessment of the contributions of each component of the LLMDFA framework. LLMDFA consistently outperforms each ablation, demonstrating the effectiveness of its multi-faceted approach in mitigating the hallucinations inherent in LLM-based dataflow analysis.

This figure compares the performance of LLMDFA with three other methods: CodeFuseQuery, Pinpoint, and an LLM-based end-to-end approach. It shows precision, recall, and F1 scores for each method across three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, and OSCI). The comparison highlights LLMDFA’s superior performance, particularly its improved F1 score, indicating a better balance of precision and recall compared to the other techniques.

The workflow of LLMDFA is presented as a flowchart, highlighting its three main phases: Source/Sink Extraction, Dataflow Summarization, and Path Feasibility Validation. Each phase utilizes LLMs and external tools to mitigate hallucinations and improve the reliability of dataflow analysis. The Source/Sink Extraction phase leverages LLMs to generate scripts that use parsing libraries to identify sources and sinks. The Dataflow Summarization phase employs few-shot chain-of-thought prompting to summarize dataflow facts within individual functions. Finally, the Path Feasibility Validation phase utilizes LLMs to synthesize scripts that use SMT solvers to check the feasibility of identified dataflow paths. This decomposition of the problem into smaller, more manageable subtasks is a key aspect of LLMDFA’s approach to minimizing inaccuracies from large language model outputs.

The figure illustrates the three-phase workflow of LLMDFA. Phase I, Source/Sink Extraction, uses LLMs to synthesize scripts leveraging parsing libraries to extract sources and sinks from the program’s CFG. Phase II, Dataflow Summarization, employs few-shot chain-of-thought prompting to align LLMs with program semantics and summarize dataflow facts. Phase III, Path Feasibility Validation, utilizes LLMs to synthesize Python scripts invoking Z3 solvers to validate the feasibility of the dataflow facts. This multi-step approach aims to mitigate the hallucinations inherent in using LLMs for complex reasoning tasks.

The figure shows a detailed workflow of LLMDFA, which is divided into three phases: Source/Sink Extraction, Dataflow Summarization, and Path Feasibility Validation. Each phase utilizes LLMs in conjunction with external tools to mitigate hallucinations and improve accuracy. The Source/Sink Extraction phase leverages LLMs to generate scripts that use parsing libraries to identify sources and sinks in the code. The Dataflow Summarization phase employs few-shot chain-of-thought prompting to summarize dataflow facts within functions. Finally, the Path Feasibility Validation phase uses LLMs to generate scripts that use Z3 solvers to validate the feasibility of identified dataflow paths.

More on tables

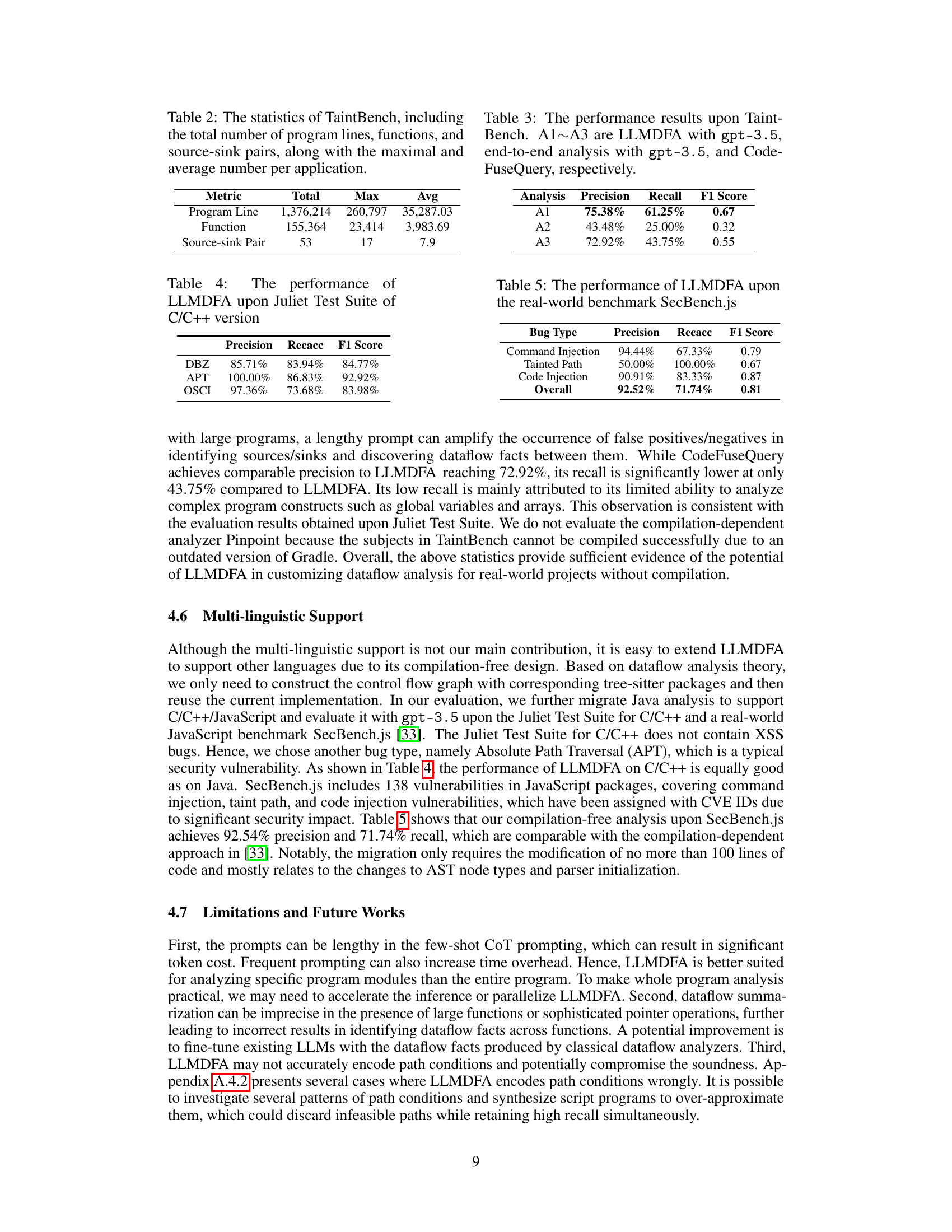

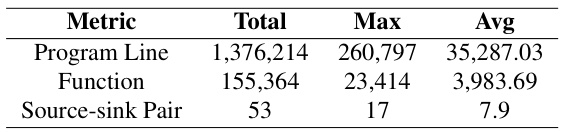

This table presents a statistical overview of the TaintBench dataset, a collection of real-world Android malware applications used for evaluating dataflow analysis techniques. It shows the total number of lines of code, functions, and source-sink pairs across all applications in the dataset. It also provides the maximum and average values for each metric, offering insights into the size and complexity variation within the dataset.

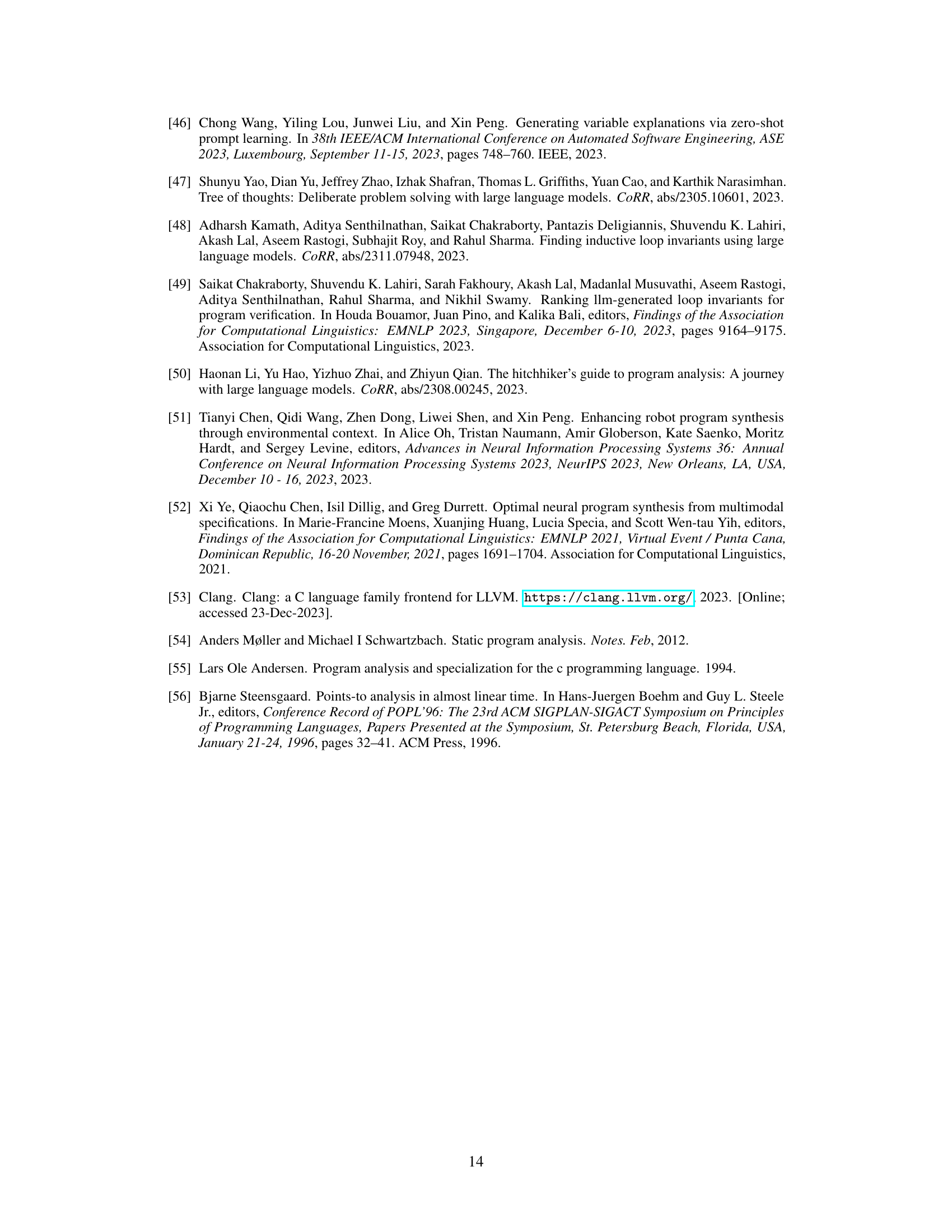

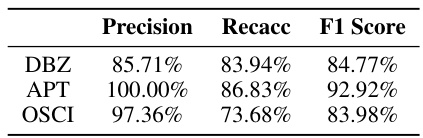

This table presents the performance of LLMDFA (a novel LLM-powered dataflow analysis framework) on the Juliet Test Suite for C/C++ code. It shows the precision, recall, and F1 score achieved by LLMDFA in detecting three types of bugs: Divide-by-Zero (DBZ), Absolute Path Traversal (APT), and OS Command Injection (OSCI). The results demonstrate LLMDFA’s effectiveness across different bug types in C/C++ code.

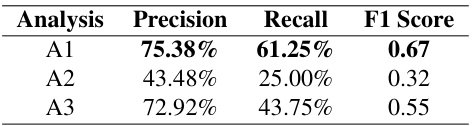

This table presents the performance comparison results of three different dataflow analysis methods on the TaintBench dataset. A1 represents the performance of LLMDFA using the gpt-3.5 language model, A2 shows the results of a baseline end-to-end analysis method also using gpt-3.5, and A3 displays the results of the CodeFuseQuery method. The metrics used for comparison include precision, recall, and F1 score, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of each method in detecting dataflow-related issues within real-world Android applications.

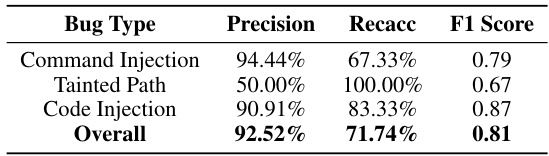

This table presents the performance of LLMDFA on the SecBench.js benchmark, a real-world dataset of JavaScript vulnerabilities. The results show the precision, recall, and F1-score achieved by LLMDFA in detecting three types of vulnerabilities: command injection, tainted paths, and code injection. The overall performance is also included.

This table presents the performance of LLMDFA, a large language model-powered dataflow analysis framework, in detecting three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, OSCI) using four different LLMs (gpt-4, gpt-3.5, gemini-1.0, claude-3). It breaks down the performance into three phases: source/sink extraction, dataflow summarization, and path feasibility validation, showing the precision, recall, and F1-score for each phase and the overall detection. This allows for a detailed analysis of LLMDFA’s performance across different LLMs and stages of the dataflow analysis process.

This table presents the performance of LLMDFA, a large language model-powered dataflow analysis framework, across different phases (source/sink extraction, dataflow summarization, path feasibility validation) and overall detection. It shows the precision, recall, and F1 score achieved using four different LLMs (gpt-4, gpt-3.5-turbo-0125, gemini-1.0, and claude-3) for three types of bugs: Divide-by-Zero (DBZ), Cross-Site-Scripting (XSS), and OS Command Injection (OSCI). The results demonstrate LLMDFA’s effectiveness across various LLMs and bug types.

This table presents the performance of the LLMDFA model in detecting three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, and OSCI) using four different LLMs (gpt-3.5, gpt-4, gemini-1.0, and claude-3). The performance is broken down into three phases: source/sink extraction, dataflow summarization, and path feasibility validation. For each phase and the overall detection, the precision, recall, and F1-score are reported for each LLM.

This table presents the performance of the LLMDFA model in detecting three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, OSCI) using four different LLMs (gpt-4, gpt-3.5, gemini-1.0, claude-3). It breaks down the performance into three phases: source/sink extraction, dataflow summarization, and path feasibility validation. For each phase and the overall detection, the precision, recall, and F1-score are reported for each LLM. This allows for a comparison of the model’s performance across different LLMs and phases of the analysis.

This table presents the performance of LLMDFA in detecting three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, and OSCI) using four different LLMs. It breaks down the performance into three phases: source/sink extraction, dataflow summarization, and path feasibility validation. For each phase and the overall detection, the precision, recall, and F1-score are provided for each LLM, offering a comprehensive view of the model’s accuracy and reliability in different aspects of the dataflow analysis process.

This table presents the performance of LLMDFA, a large language model-powered dataflow analysis framework, across different phases of its operation (extraction, summarization, validation) and overall bug detection. The performance is evaluated using various LLMs (gpt-4, gpt-3.5, gemini-1.0, claude-3) for three types of bugs (DBZ, XSS, OSCI) in the Juliet Test Suite benchmark. The metrics used for evaluation are precision, recall, and F1 score.

This table presents the performance of LLMDFA (a large language model-powered dataflow analysis framework) across different phases (source/sink extraction, dataflow summarization, path feasibility validation, and overall detection) and various LLMs (gpt-4, gpt-3.5, gemini-1.0, and claude-3). The metrics used are precision (P), recall (R), and F1 score (F1), which provide a comprehensive evaluation of the method’s accuracy and effectiveness for different bug types (DBZ, XSS, OSCI).

This table presents the performance of the LLMDFA model in detecting bugs and across its three phases (source/sink extraction, dataflow summarization, and path feasibility validation). It shows precision, recall, and F1-score for each phase and overall detection. The results are shown for four different LLMs: gpt-4, gpt-3.5-turbo-0125, gemini-1.0, and claude-3.

Full paper#