↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Motion planning, crucial for both brains and AI agents, involves choosing actions to reach a goal. Current understanding of the underlying neural mechanisms is limited, lacking a unifying theoretical framework. This paper addresses this gap by framing motion planning as a ‘Lie group operator search.’ This means finding the right mathematical operation to transform the current state into the desired goal state.

This research proposes a two-layer feedforward neural circuit that efficiently solves this Lie group operator search problem. The circuit uses simple components, connection phase shift, nonlinear activation, and pooling. Remarkably, this circuit mirrors the structure of Drosophila’s goal-directed navigation circuits. The study provides geometric interpretations and computational analysis, demonstrating efficiency even surpassing some standard algorithms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in neuroscience and AI because it bridges the gap between abstract mathematical concepts and biological neural circuits. It provides a novel framework for understanding motion planning in the brain, translating complex computations into a biologically plausible neural circuit model. This opens new avenues for developing brain-inspired AI algorithms and furthering our understanding of the neural basis of decision-making and action selection.

Visual Insights#

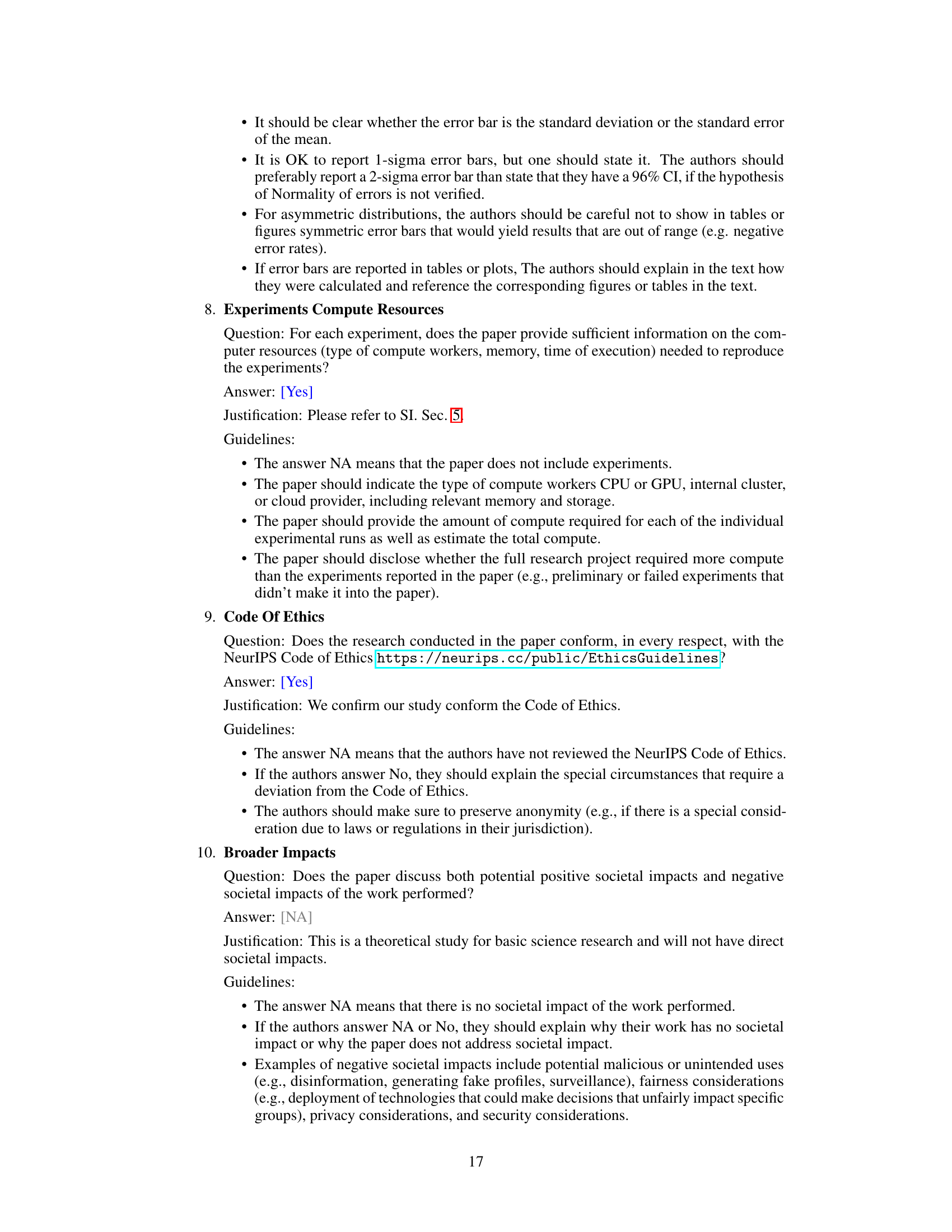

This figure illustrates the sensory-action loop, showing how the brain uses sensorimotor transformation to plan motor actions based on the world state and goals. Panel (A) shows the overall loop. Panel (B) demonstrates the equivariant map of sensory neuron responses. Panel (C) uses a 1D rotation group as an example, showing how sensory neurons code heading direction. Panel (D) explains how to find the desired operator via group convolution, finding the peak of the cross-correlation function.

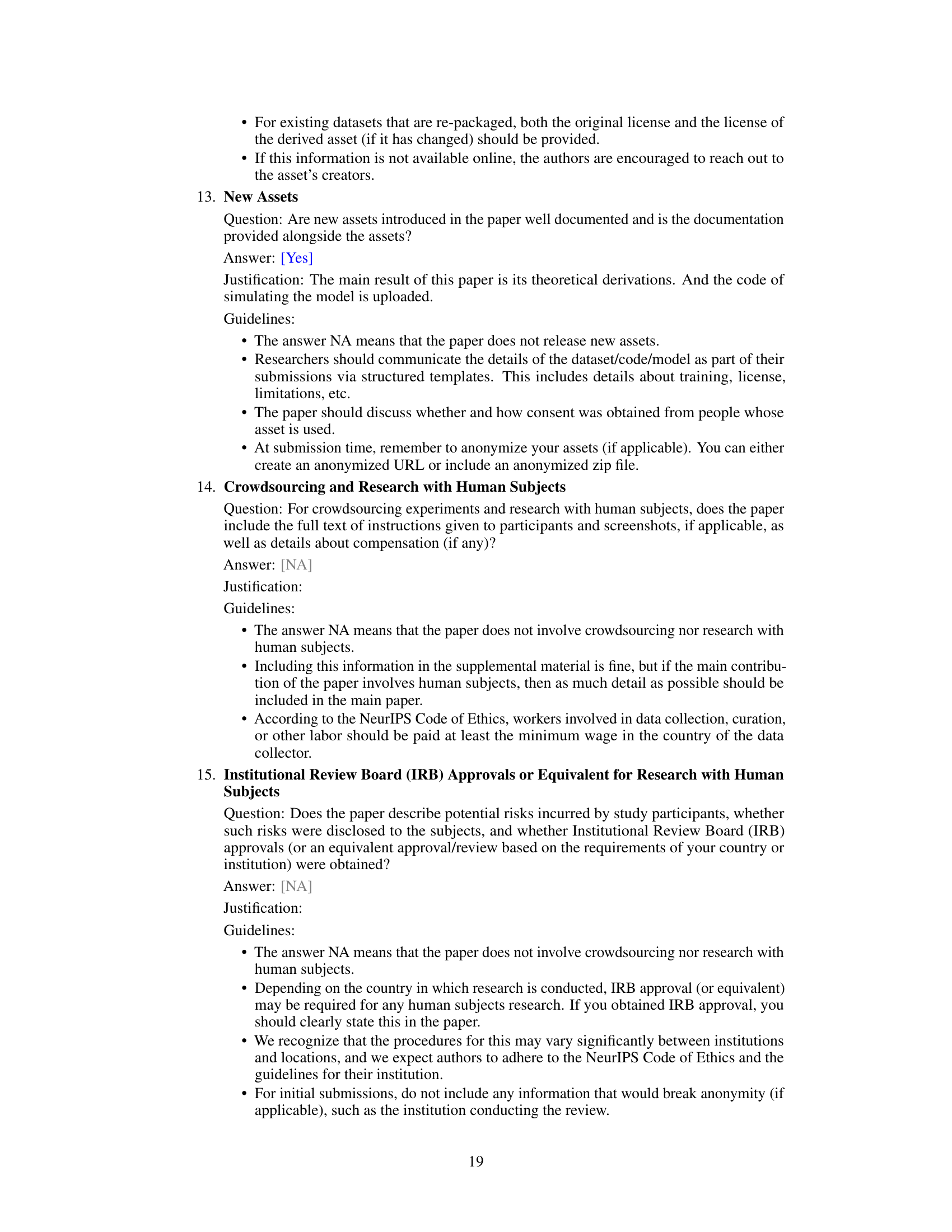

This table compares the computational complexities of three different approaches for finding rotation operators: group convolution, representation space via FFT, and a feedforward circuit. It shows that the feedforward circuit offers the lowest computational complexity, especially when the distance between the initial state and the goal state is small.

In-depth insights#

Lie Group Navigation#

Lie group navigation represents a novel framework for analyzing motion planning in goal-directed navigation. It leverages the mathematical elegance of Lie groups to model the continuous nature of movement and the transformations involved. This approach offers a powerful theoretical foundation for understanding how neural circuits might implement complex navigation behaviors. By formulating the motion planning problem as a search for optimal Lie group operators, researchers can develop computationally efficient algorithms and biologically plausible neural network models that accurately mirror the brain’s navigational capabilities. A key strength of this framework is its ability to bridge abstract mathematical concepts with concrete biological implementations, providing a deeper understanding of the underlying neural mechanisms. The use of the 1D rotation group as an example in the research helps elucidate general principles, while emphasizing the potential to extend the methodology to more complex scenarios. The findings suggest that even seemingly simple tasks like navigating along a single dimension can be intricately structured, making the Lie group approach a powerful tool for future research.

Neural Circuit Design#

A thoughtful exploration of “Neural Circuit Design” in the context of a research paper would involve a multi-faceted analysis. First, it necessitates a precise definition of the design principles employed, which may include computational considerations (e.g., efficiency, accuracy), biological plausibility (e.g., mimicking known neural structures and mechanisms), and functional requirements (e.g., achieving a specific task like motion planning). A deeper dive requires examining the circuit architecture, including the number of layers, neuron types, and connection patterns, which often reveal the fundamental information processing capabilities. Analysis should also explore how learning and plasticity are incorporated into the design to address potential challenges. Finally, evaluating the robustness of the design to noise and variations in parameters is crucial, particularly in the context of biological systems where these factors are inherent. A comprehensive assessment would consider all of these factors to offer a deep understanding of the proposed “Neural Circuit Design”.

Geometric Interpretation#

A geometric interpretation of a mathematical concept, such as motion planning in this case, offers valuable insights by visualizing abstract ideas in a concrete space. This approach enhances understanding by connecting mathematical formalism to intuitive geometric representations. For instance, representing the space of possible actions as a Lie group and visualizing transformations within this space facilitates a deeper grasp of how actions modify states. In this specific application, the geometric interpretation might show how sequences of rotations move a point (representing a state) toward a target location. This visualization can reveal inherent properties like symmetries and constraints not readily apparent from purely algebraic formulations. Moreover, geometric interpretations can be useful to design biologically plausible neural circuits that mimic the underlying mathematical operations. By relating geometrical objects, transformations, and their interactions to the structure and functionality of neural networks, researchers can gain a more intuitive and comprehensive understanding of the entire system.

Computational Complexity#

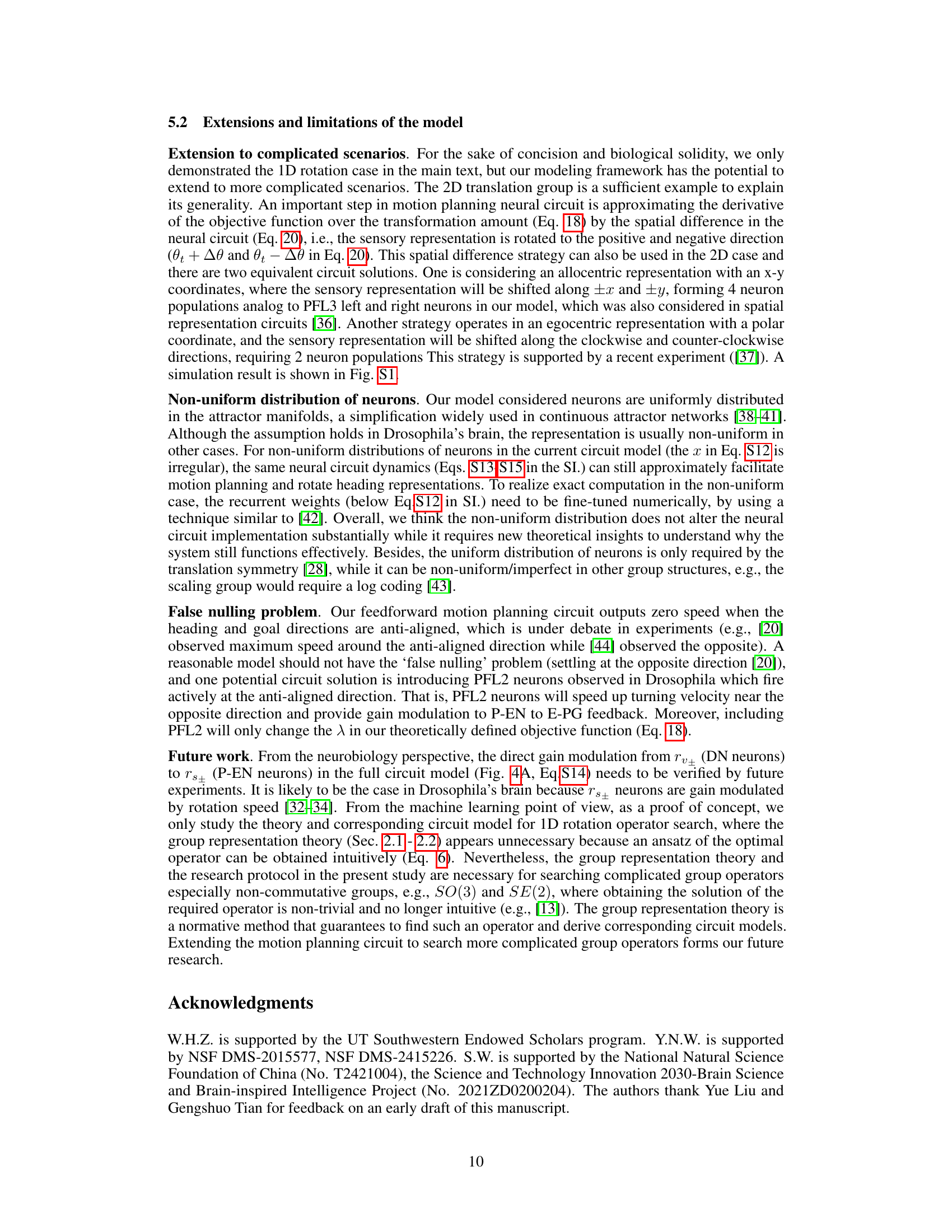

The analysis of computational complexity in the context of motion planning is crucial for evaluating the efficiency and scalability of proposed algorithms. The paper highlights the computational cost of various approaches, contrasting the O(N²) complexity of group convolution with the O(N log N) efficiency achieved by utilizing the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) in the representation space. This efficiency gain is significant for high-dimensional problems, where the number of neurons (N) becomes substantial. Furthermore, the paper demonstrates that a feedforward neural circuit implementation can further reduce computational complexity, achieving O(N log|h-s|) under certain conditions. This result is particularly important as it establishes the possibility of achieving efficient motion planning using biologically plausible neural circuits. The comparison of complexities underscores the importance of algorithm selection based on the specific demands of the task and the computational resources available. Future work should explore the generalizability of this complexity analysis to more complex Lie groups and motion planning scenarios.

Future Research#

The ‘Future Research’ section of this paper highlights several promising avenues. Extending the 1D rotation model to more complex scenarios, such as 2D translation or 3D rotation, is crucial. Addressing the limitations of the current model, specifically the assumption of uniform neuron distribution and potential ‘false nulling’ issues, will enhance robustness and biological realism. Investigating the impact of different nonlinear activation functions on the feedforward circuit’s performance is essential for practical applications. Finally, exploring the use of group representation theory for searching non-commutative group operators offers a significant theoretical challenge and potential for groundbreaking advancements in understanding and modeling more complex biological systems. This research program represents an exciting intersection of neuroscience, mathematics, and engineering.

More visual insights#

More on figures

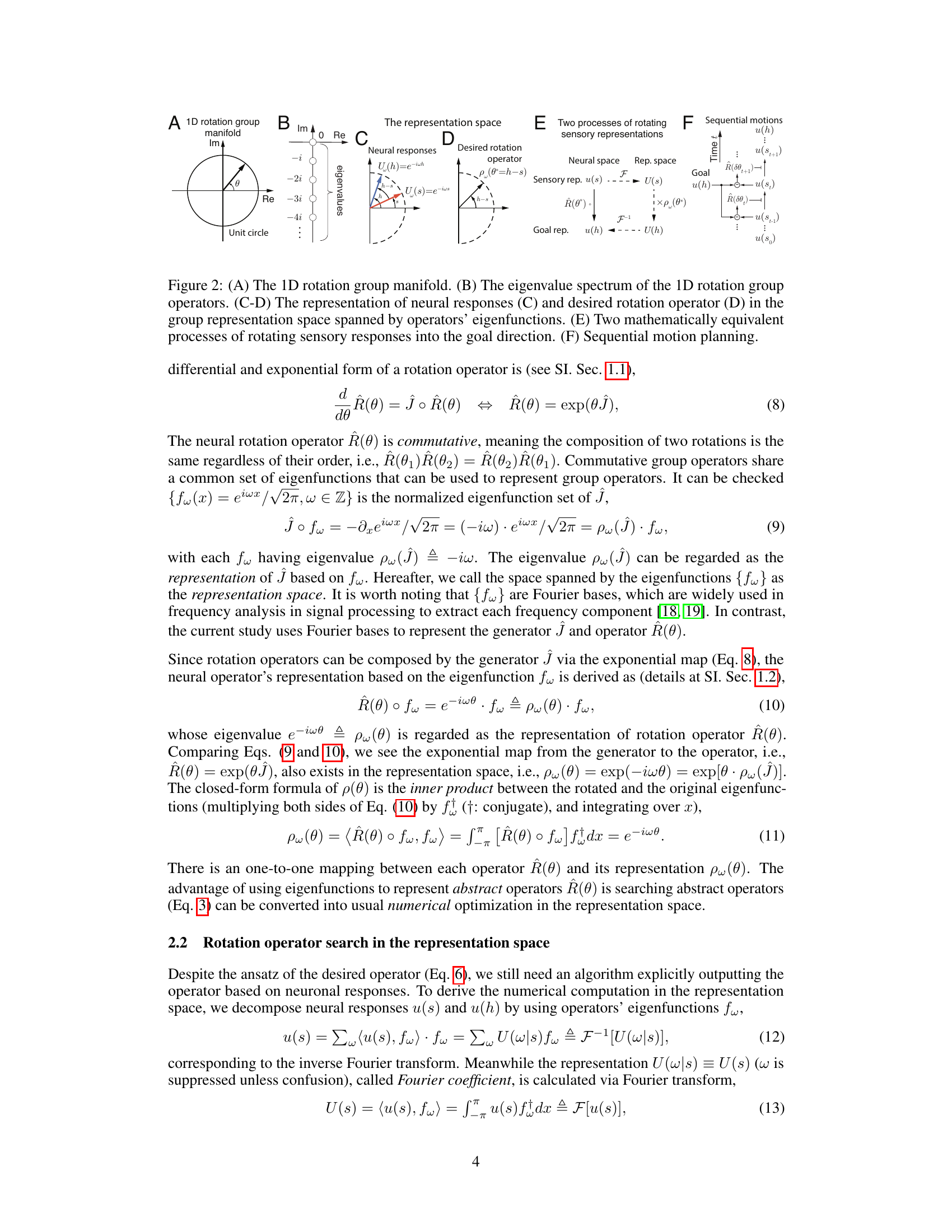

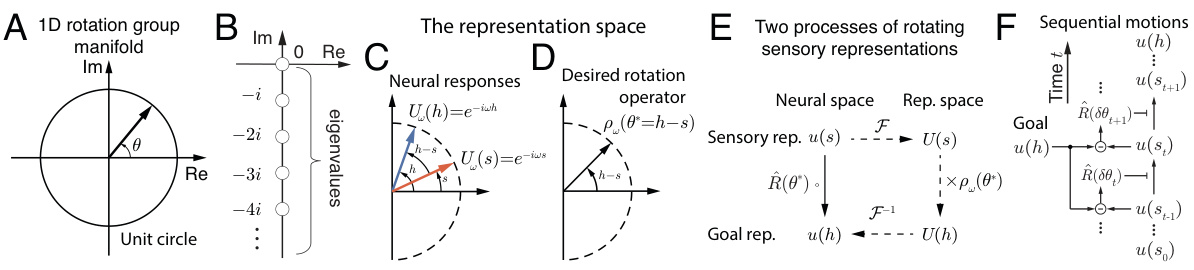

This figure illustrates the mathematical concepts behind the 1D rotation group operator search. Panel A shows the U(1) group manifold, a unit circle. Panel B displays the eigenvalue spectrum of the rotation group operators. Panels C and D show how neural responses and the desired rotation operator are represented in the group representation space using eigenfunctions. Panel E illustrates two ways to rotate sensory responses to the goal direction, either by applying the rotation operator directly or by using the representation space. Finally, Panel F depicts the process of sequential motion planning, which breaks down a complex motion into a series of smaller rotations.

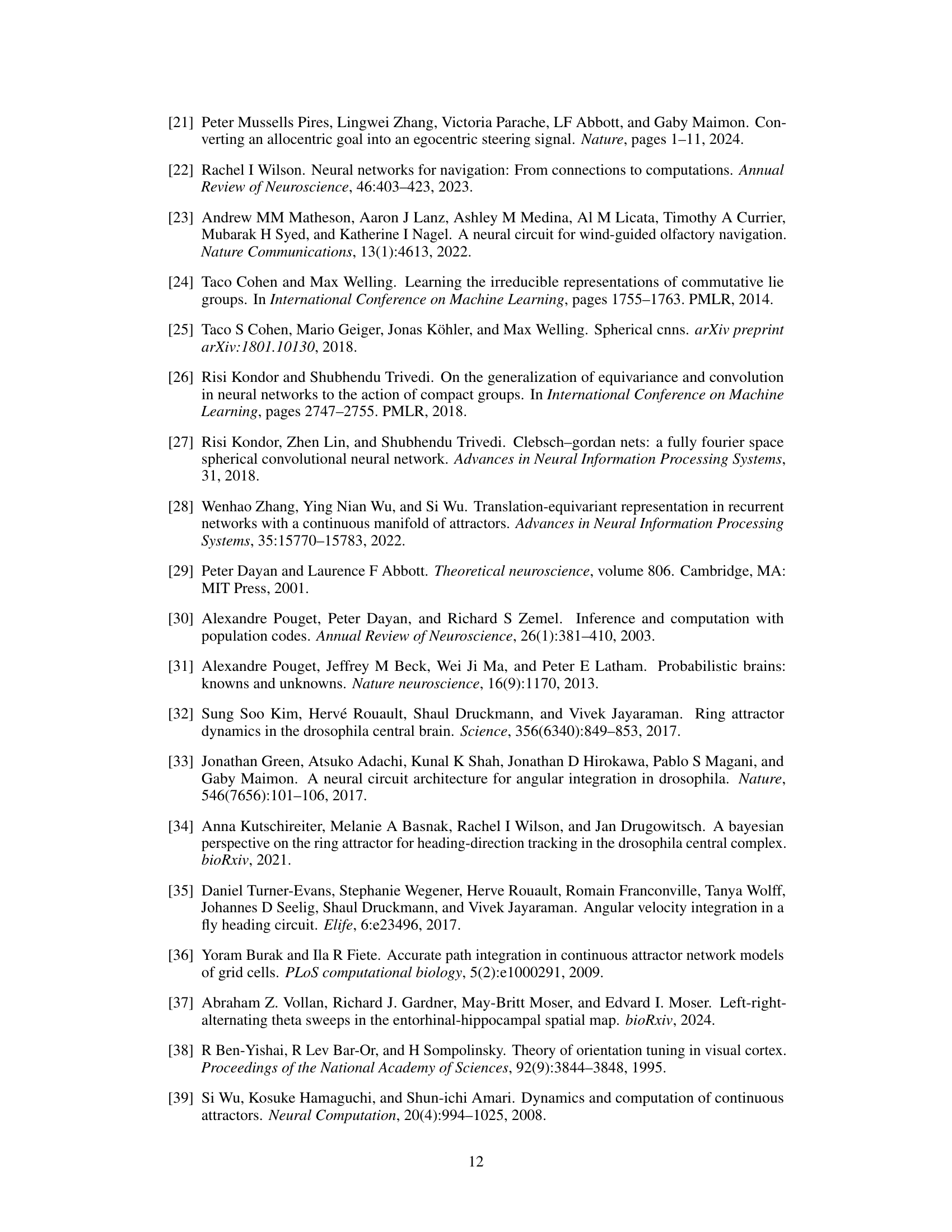

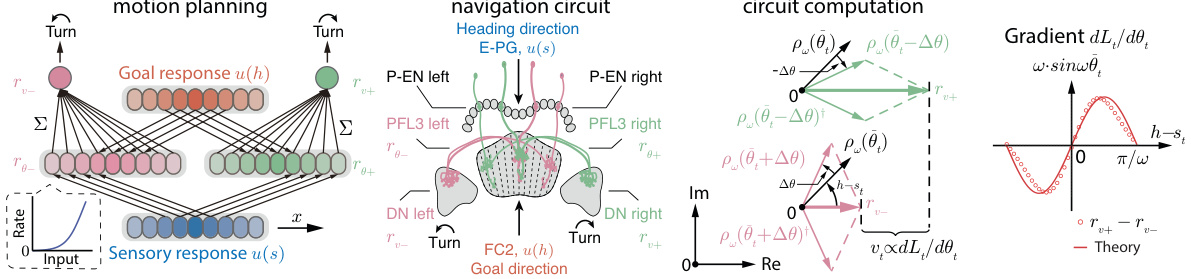

This figure details a two-layer feedforward circuit for motion planning, comparing it to Drosophila’s goal-directed navigation circuit. It illustrates the circuit motifs (phase shift, nonlinear activation, pooling) and shows how the circuit computes rotation speed. The geometry of computation in representation space is also depicted, highlighting the sine function relationship between rotation speed and distance to the goal.

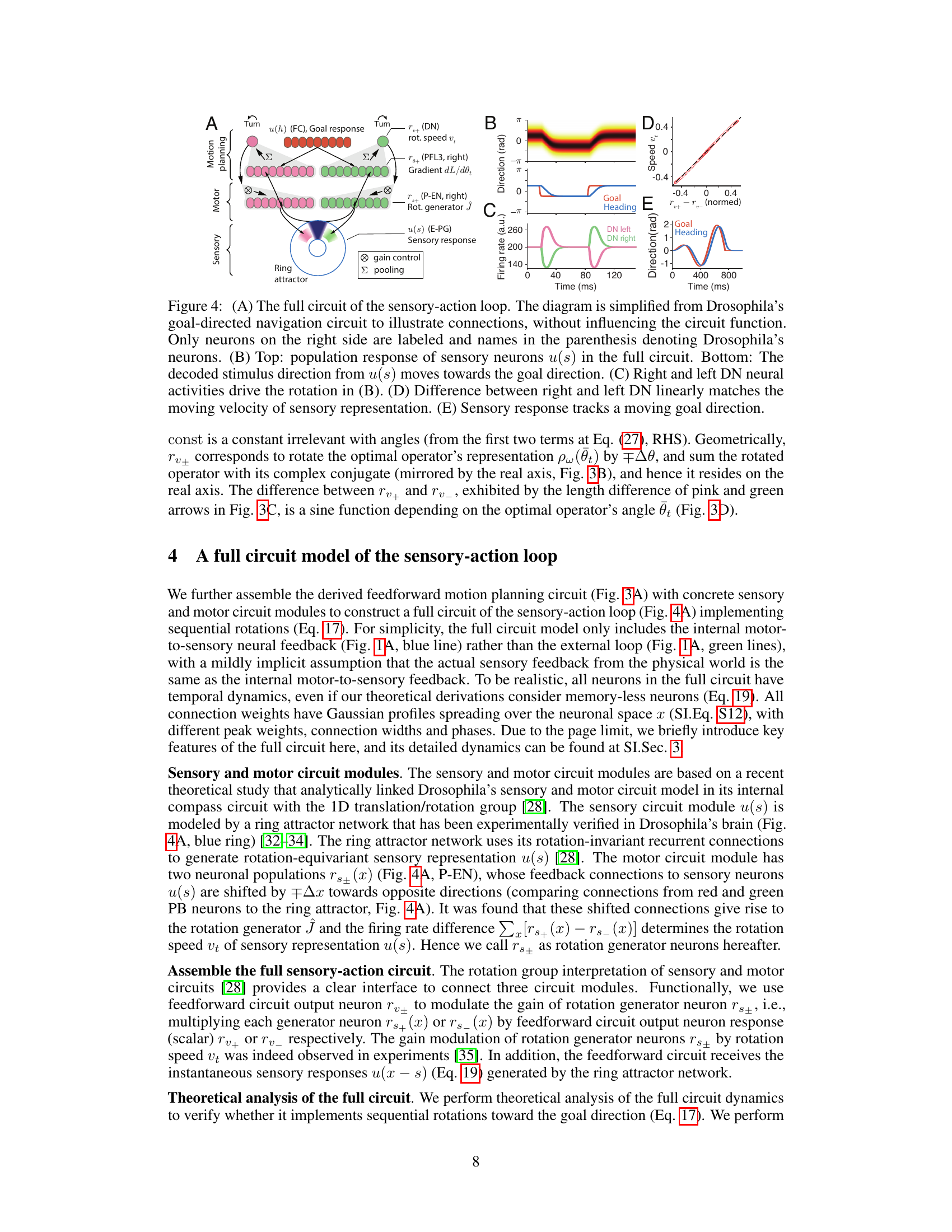

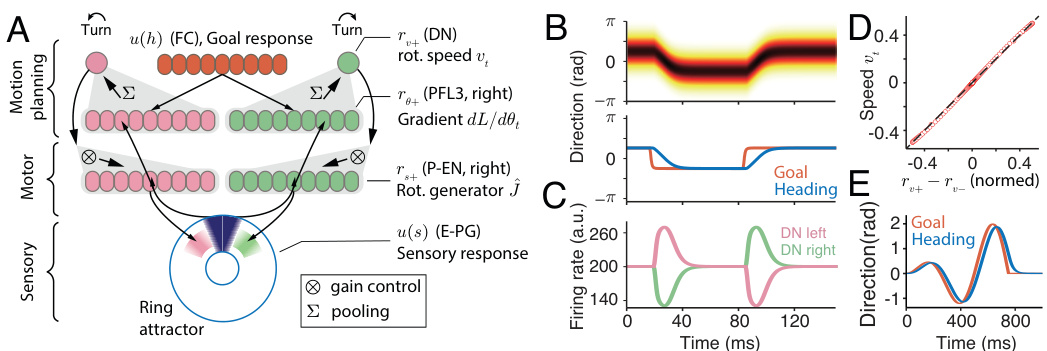

This figure shows a complete model of the sensory-action loop incorporating the feedforward motion planning circuit. Panel A illustrates the circuit’s structure, which simplifies Drosophila’s goal-directed navigation circuit for clarity, highlighting key connections and modules. Panel B demonstrates the population response of sensory neurons (top) and how the decoded stimulus direction moves towards the goal (bottom). Panel C shows the neural activities driving the rotation. Panel D illustrates the relationship between the difference in right and left DN neural activities and the speed of sensory representation movement. Finally, Panel E showcases the sensory response tracking a moving goal direction.

Full paper#