↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Modern representation learning often focuses on recovering latent generative factors, but ensuring identifiability requires strong assumptions and many interventions. This approach is often infeasible for high-dimensional data like images or text. Furthermore, even if such factors were identified, there is no guarantee that they would be human-interpretable, especially if there are an enormous number of such factors.

This paper proposes to sidestep this limitation by focusing on a smaller set of interpretable concepts, which are defined geometrically as linear subspaces in the latent space. The key idea is to use conditioning rather than strict interventions. The paper provides theoretical guarantees on concept identifiability under this framework and supports these claims with experiments across synthetic data, CLIP embeddings, and large language models. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach, showing that it recovers interpretable concepts from diverse data with minimal assumptions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers seeking interpretable representations from complex data. It offers a novel approach that bridges the gap between causal and concept-based learning, offering a more accessible and efficient path to identifying human-interpretable concepts. Its theoretical foundations and experimental validations on diverse data types (synthetic data, CLIP models, LLMs) make it highly relevant to various research areas. This work opens new avenues for identifiable representation learning and concept discovery across multiple domains.

Visual Insights#

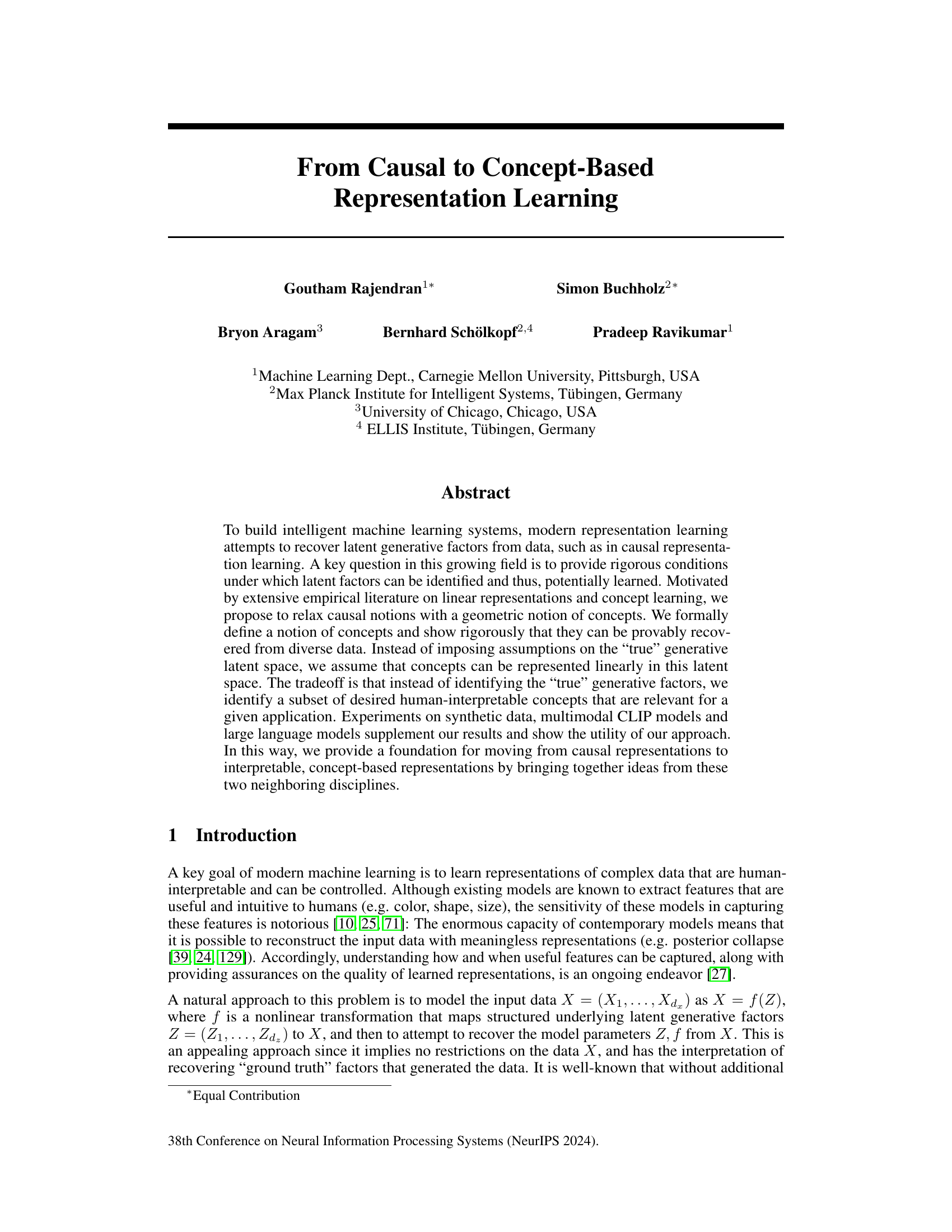

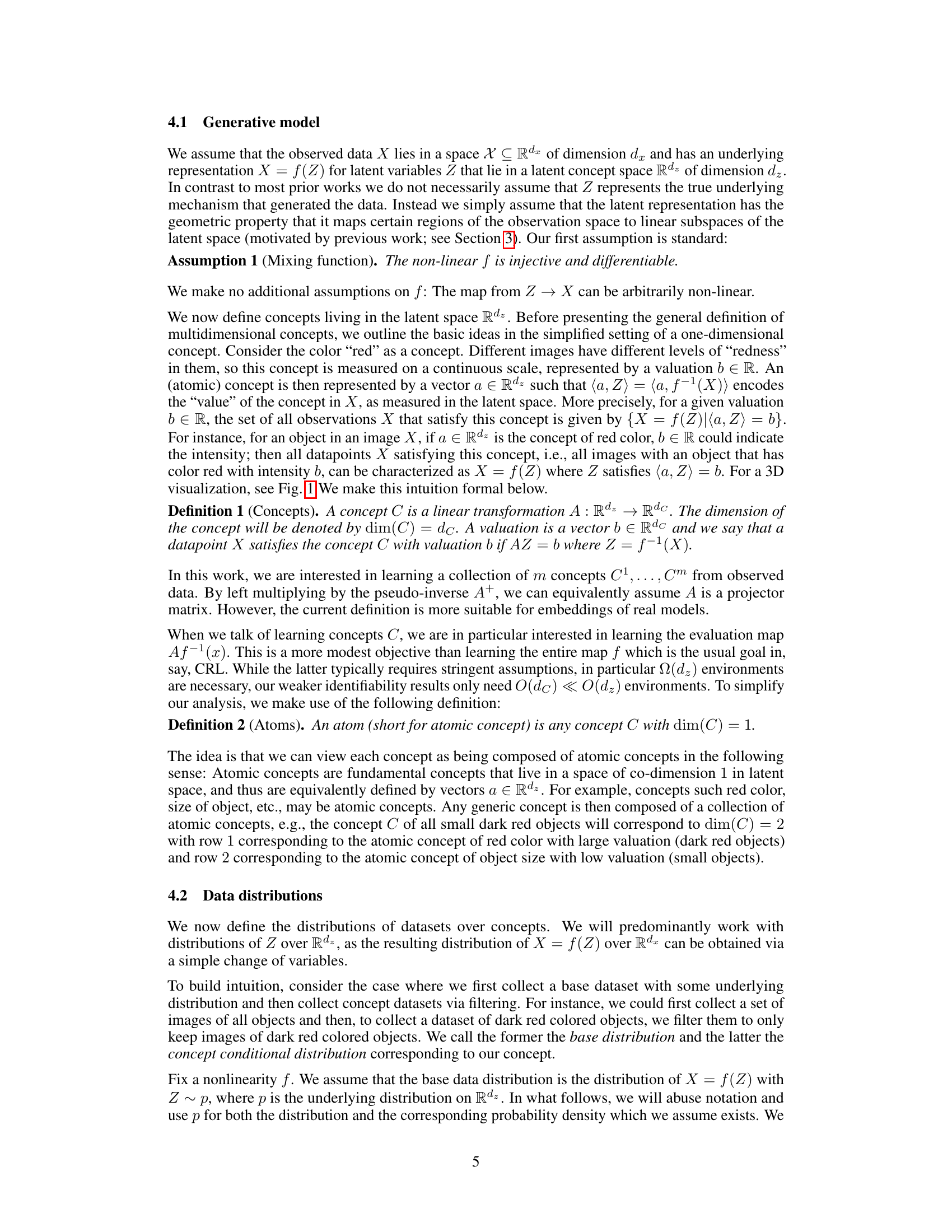

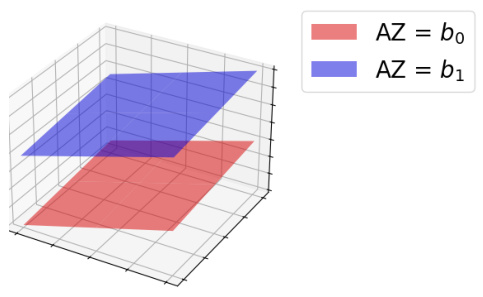

This figure illustrates the geometric notion of concepts as affine subspaces in the latent space. It shows two parallel planes representing the same concept but with different valuations (values of the concept). The concept is defined by a linear transformation A, where AZ represents the concept valuation. The figure visually demonstrates that the same concept can have different valuations depending on the specific instance of the data being represented.

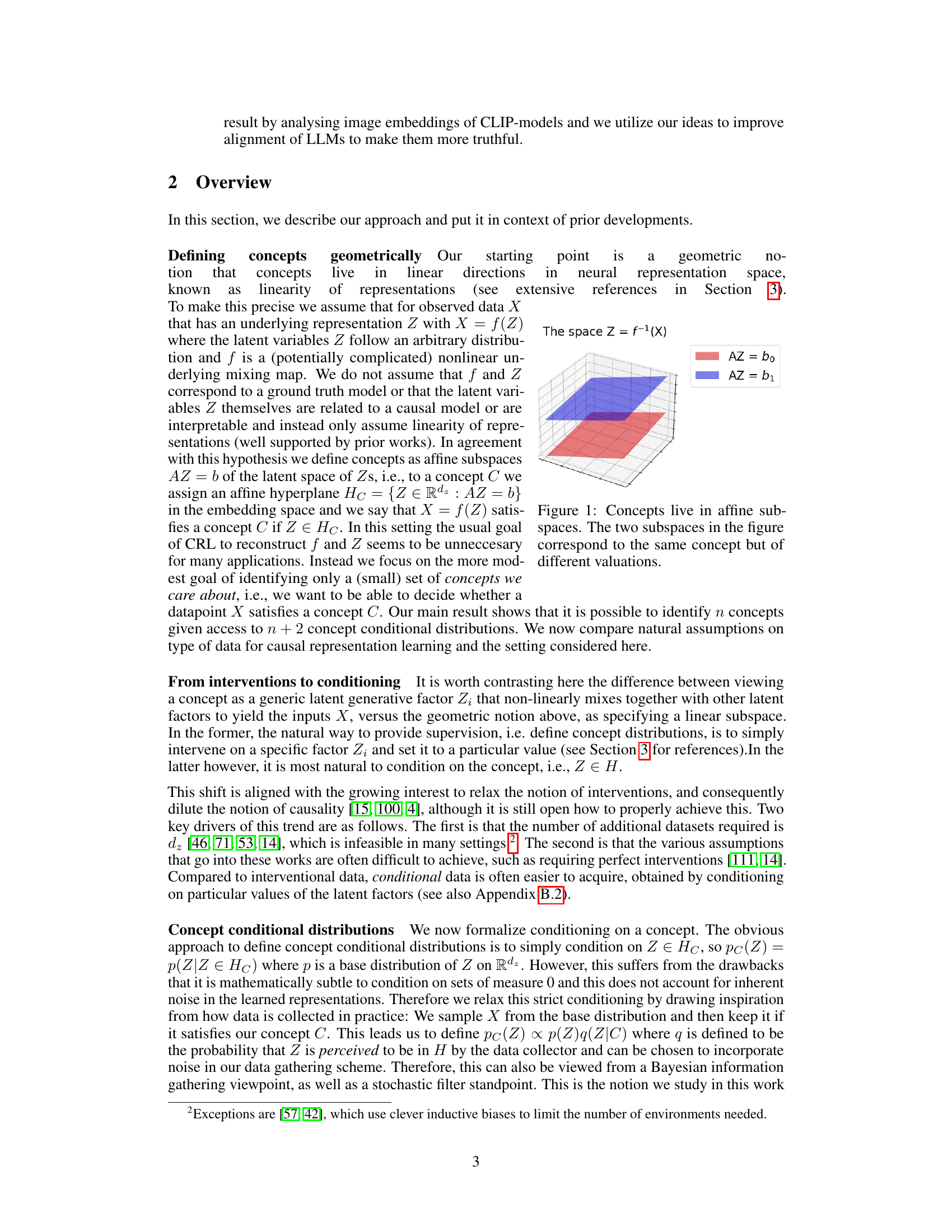

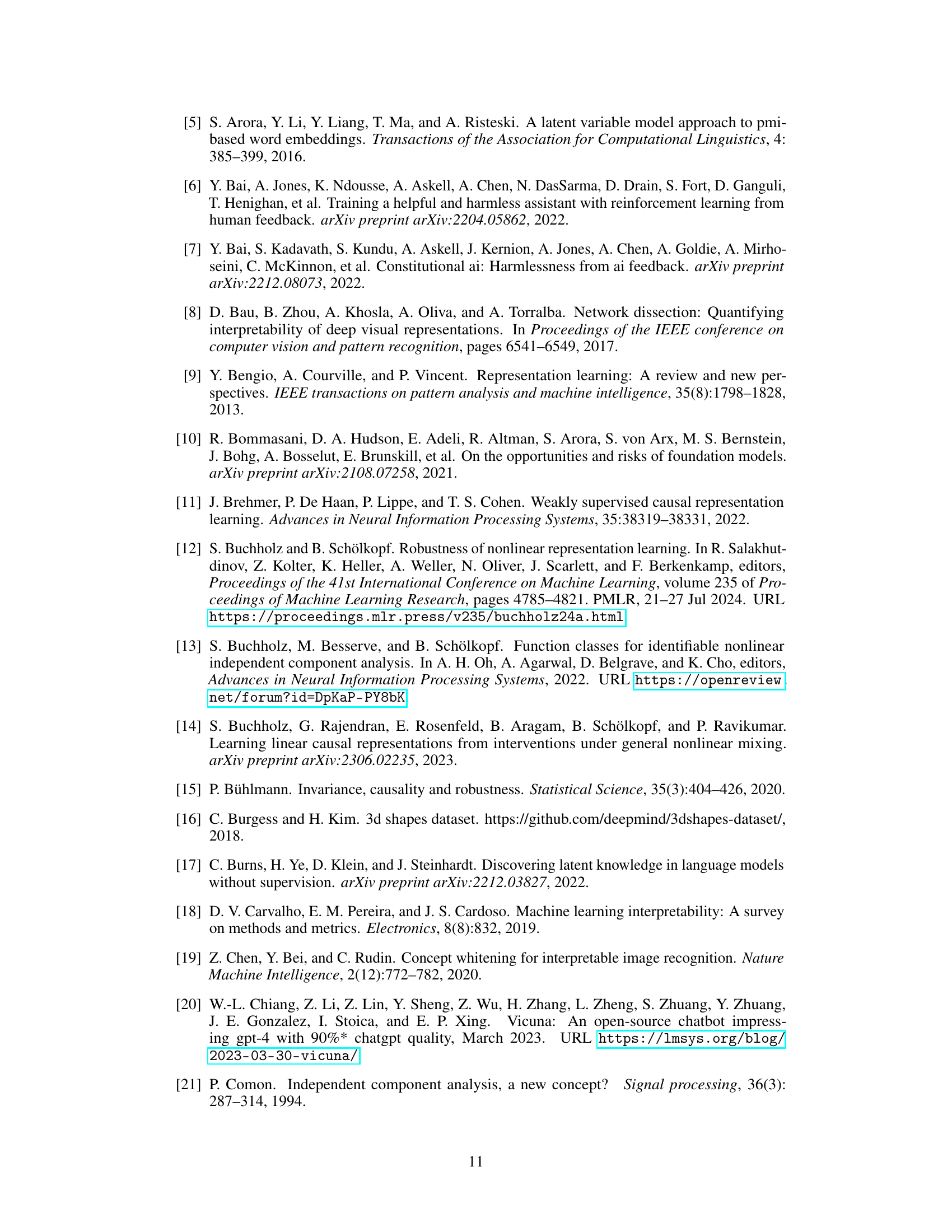

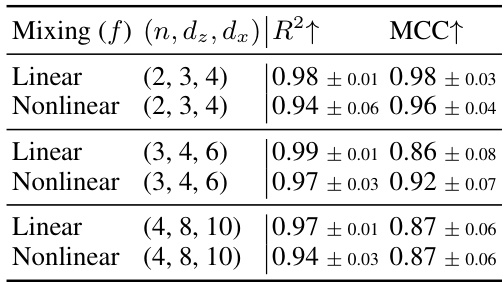

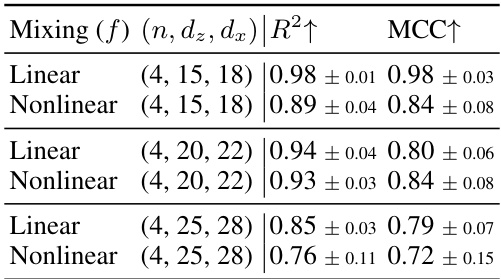

This table presents the results of experiments on linear identifiability when the number of concepts (n) is less than the latent dimension (dz) with different observed dimensions (dx). The results are averaged over five seeds, providing a measure of the robustness of the findings. The table shows the R² (R-squared) and MCC (Matthews correlation coefficient) metrics, which quantify the accuracy of the linear identifiability of the concepts. Higher values indicate better performance.

In-depth insights#

Concept Formalization#

Formalizing the concept of a “concept” is crucial for bridging the gap between human intuition and machine learning. A strong formalization should be mathematically rigorous, enabling precise definitions and enabling provable guarantees on learnability. The approach taken should consider various factors: representation in latent space (linear vs. non-linear), concept granularity (atomic vs. composite concepts), and the method of concept acquisition (interventional vs. observational). Handling noisy or uncertain data is also critical, as perfect information is rarely available in real-world applications. Ideally, the formalization should be flexible enough to encompass the diverse ways that humans perceive and categorize data, while simultaneously providing sufficient structure for computational analysis and theoretical guarantees. Successful concept formalization would pave the way for more robust and human-interpretable machine learning models.

Identifiability Theory#

Identifiability theory, in the context of representation learning, tackles the crucial question of whether underlying latent factors can be uniquely recovered from observed data. This is essential because many representation learning methods aim to discover these latent factors, which might represent meaningful concepts or causal mechanisms. However, without strong assumptions, the problem is ill-posed; multiple combinations of latent factors and generative functions can equally explain the data. Identifiability theory thus focuses on establishing sufficient conditions under which unique recovery is guaranteed, often through assumptions about the data distribution, generative process, or the structure of the latent factors themselves. A key area of focus is the impact of interventions and conditioning; these operations provide additional information that can constrain the possibilities and improve identifiability. The theory is vital for assessing the reliability and interpretability of learned representations, ensuring that inferred concepts or causes are not simply artifacts of the model’s capacity but reflect genuine underlying structure in the data.

Contrastive Learning#

Contrastive learning, a self-supervised learning technique, shines a light on the intricate relationships between data points by comparing similar and dissimilar examples. Its core principle lies in maximizing the similarity between positive pairs (similar data points) while simultaneously widening the gap between negative pairs (dissimilar ones). This approach is particularly valuable in scenarios where labeled data is scarce or acquiring labels is expensive. By cleverly designing the contrast function, contrastive learning empowers models to capture complex, high-dimensional data structures effectively. A significant advantage lies in its ability to leverage unlabeled data for pre-training, thus laying a foundation for subsequent fine-tuning on limited labeled datasets. Moreover, this technique’s flexibility in employing various architectural choices and data augmentation strategies adds to its power and versatility. However, careful consideration of the contrast function is essential to avoid trivial solutions and ensure effective learning, and a well-defined similarity metric is key to its success. The computational cost associated with comparing numerous data points also needs consideration for large-scale applications. Despite these challenges, contrastive learning offers a powerful paradigm for representation learning, consistently pushing the boundaries of self-supervised learning.

CLIP & LLMs#

The intersection of CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) and LLMs (Large Language Models) offers exciting avenues for research. CLIP’s ability to connect image and text embeddings allows LLMs to access and process visual information, bridging the gap between modalities. This opens the possibility of creating more sophisticated AI systems that can understand and interact with the world in a more comprehensive manner. For example, the combination could enable improved image captioning, visual question answering, and even more advanced applications in areas like robotics and content creation. However, challenges remain, including the potential for biases inherited from the training data of either model, and ensuring the ethical use of such powerful technology. Further research is needed to fully explore the synergies and address the limitations of integrating these two powerful approaches, particularly focusing on mitigating biases and ensuring responsible development.

ITI Refinement#

ITI Refinement, in the context of large language model (LLM) alignment, focuses on enhancing the Inference-Time Intervention (ITI) technique. ITI originally used steering vectors to nudge LLM activations toward desired attributes like truthfulness. Refinement efforts likely explore improvements by moving beyond single vectors to incorporate richer representations. This could involve using matrices instead of vectors to simultaneously influence multiple concepts or employing context-dependent weights for finer control. The goal is to make interventions more precise, efficient and less prone to unintended consequences, ensuring the LLMs are steered accurately towards the desired behaviour without sacrificing their other capabilities. Such advancements would improve the effectiveness of LLM alignment techniques and enhance the human interpretability and reliability of AI systems. A key consideration would be computational efficiency and the need to maintain real-time inference capabilities.

More visual insights#

More on tables

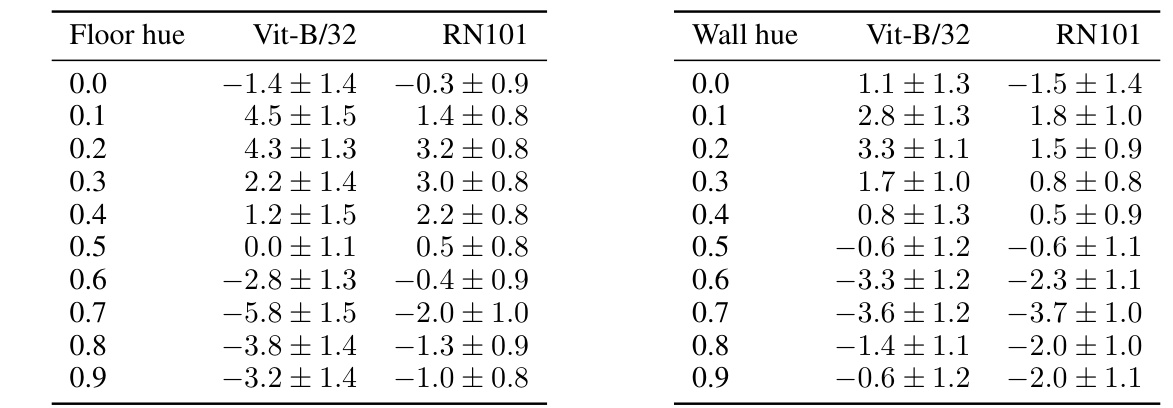

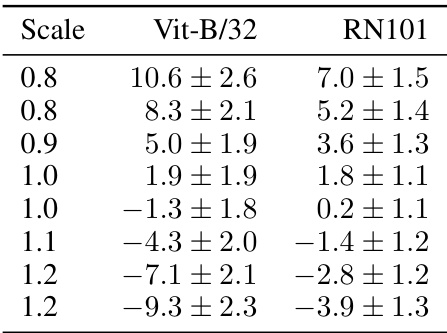

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the concept valuations for the floor hue and wall hue attributes on a test set, using two different CLIP models (ViT-B/32 and RN101). Each row represents a specific hue value (0.0 to 0.9), and the columns show the mean and standard deviation of the valuations for each model. The data illustrates the distributions of the valuations for each hue and how consistent the valuations are between the models.

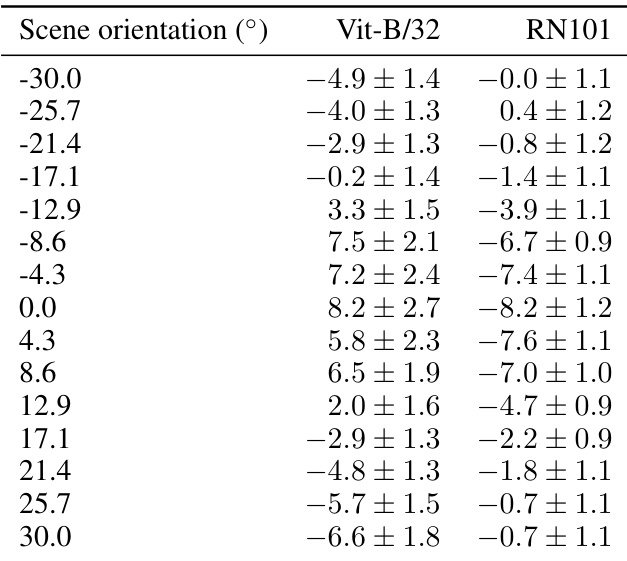

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the concept valuations for object hue and scene orientation attributes obtained from two different CLIP models (ViT-B/32 and RN101). The results show the average value and variability of the learned concepts for different values of the attributes on a held-out test set. The variations of object hue are 0.0 to 0.9, with corresponding mean valuations reported for each CLIP model.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the concept valuations for the object hue and scene orientation attributes on a test set. The valuations were obtained using two different pretrained CLIP models (ViT-B/32 and RN101). The data shows the concept valuations for different values of the hue and orientation, allowing for an analysis of how well these concepts are captured by the models. The results are relevant to the paper’s investigation into the linear representation hypothesis for human-interpretable concepts in multimodal models.

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of concept valuations for the scale and shape attributes obtained from two different CLIP models (ViT-B/32 and RN101) on a test set. The results are broken down by the specific values of the scale and shape attributes. The table helps evaluate the linearity of representation hypothesis by examining the concept valuations across different models and values.

This table shows the mean and standard deviation of the concept valuations for the scale and shape attributes on the test set, using two different CLIP models (ViT-B/32 and RN101). The results are separated for different shapes (cube, cylinder, ball, ellipsoid) and for different scales (0.8, 0.9, 1.0, 1.1, 1.2). The concept valuation is the value of the linear projection of the image embedding into the concept vector.

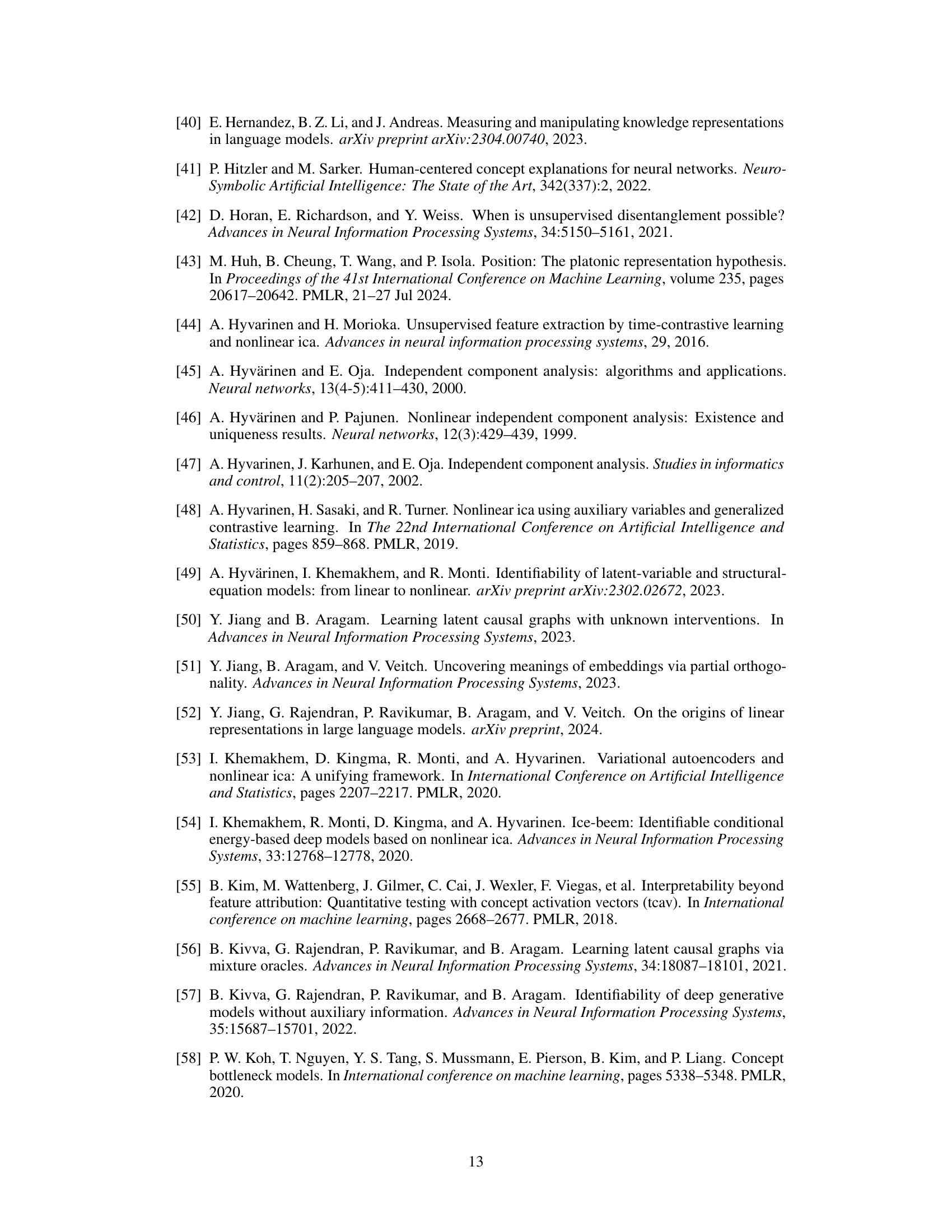

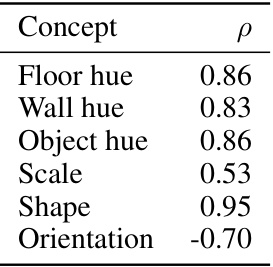

This table shows the correlation coefficients between the concept valuations obtained from two different CLIP models (ViT-B/32 and RN101) for six different factors of variation in the 3D-Shapes dataset. High correlation suggests that the concept valuations learned from different models are consistent, up to a linear transformation. The factors of variation included are floor hue, wall hue, object hue, scale, shape and orientation.

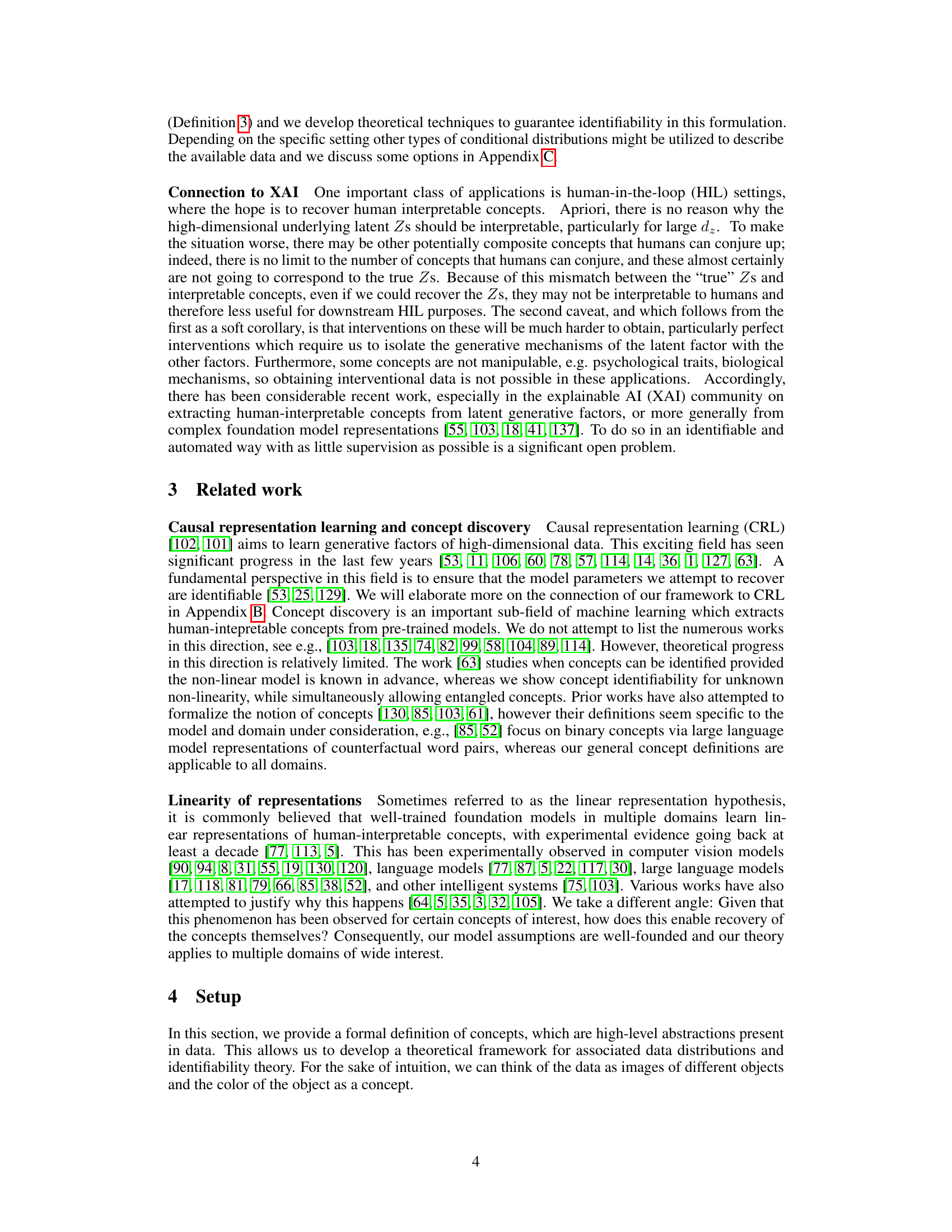

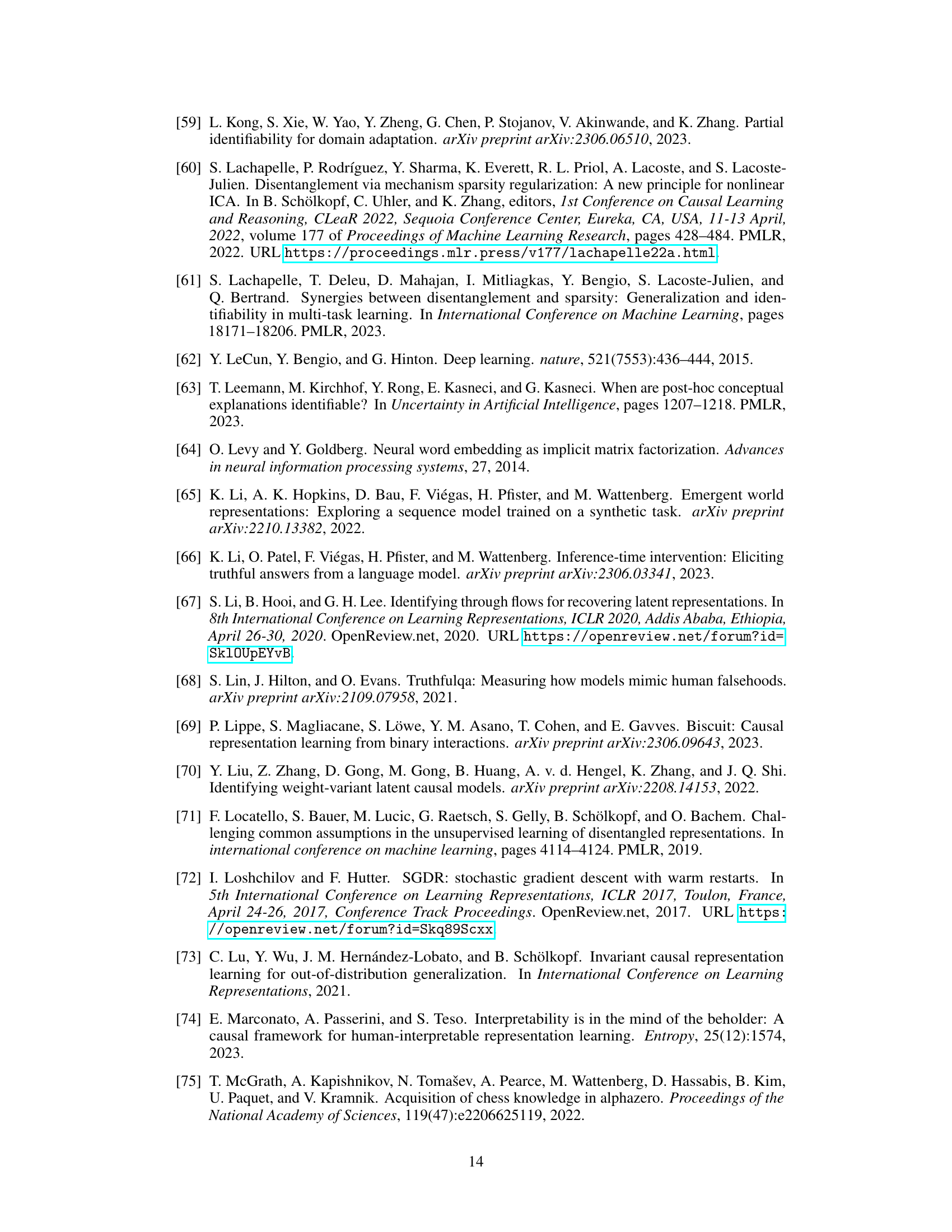

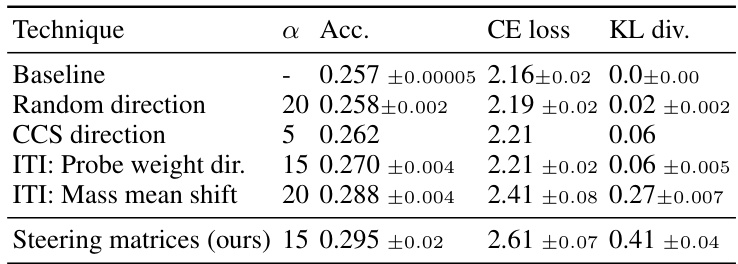

This table compares the performance of different steering vector techniques for improving the truthfulness of LLMs using the TruthfulQA benchmark. The techniques compared include a baseline, a random direction, a CCS direction, two variants of ITI (Probe weight and Mass mean shift), and a novel approach using steering matrices. The table shows the accuracy, cross-entropy loss, and KL divergence for each technique, providing a quantitative comparison of their effectiveness in aligning LLMs toward truthfulness.

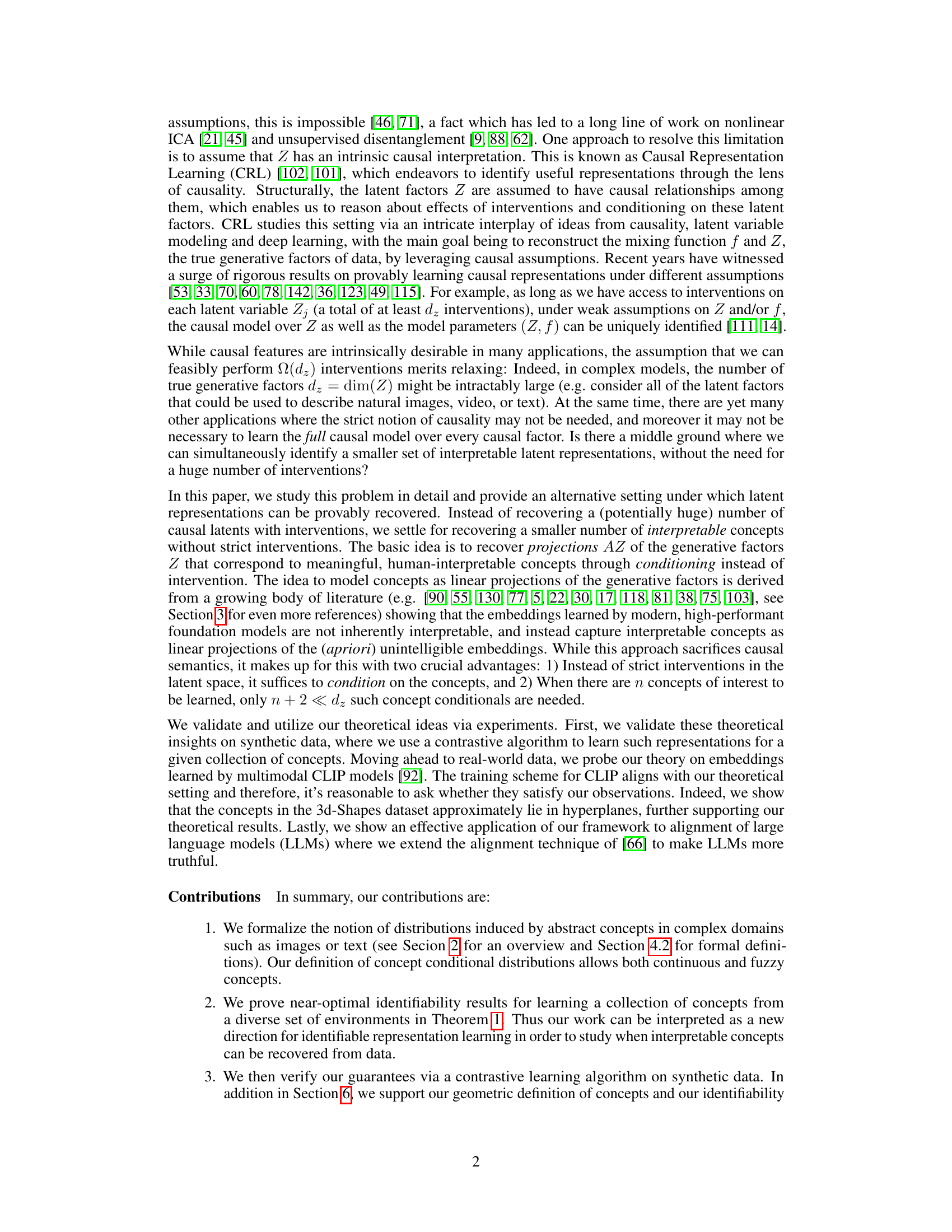

This table presents the results of linear identifiability experiments conducted on synthetic data. The experiments varied the number of concepts (n), the latent dimension (dz), and the observed dimension (dx). The table shows the R-squared (R2) and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) values obtained, averaged over five different random seeds, for both linear and non-linear mixing functions. Higher R2 and MCC values indicate better identifiability.

Full paper#