↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training machine learning models with differential privacy (DP) is crucial to protect sensitive data but often results in significant performance degradation, hindering its applicability to large-scale tasks. Existing DP optimizers, like DP-SGD, inject noise to maintain privacy, significantly affecting accuracy. This trade-off limits the use of DP in many critical applications.

This paper introduces DOPPLER, a novel approach that leverages a low-pass filter to reduce the impact of DP noise in the frequency domain. By analyzing the frequency characteristics of both the gradients and the noise, DOPPLER effectively enhances the signal-to-noise ratio. Experimental results show substantial accuracy improvement (3%-10%) on various models and datasets, demonstrating DOPPLER’s effectiveness in mitigating the performance degradation associated with DP training. The study also provides theoretical guarantees for the proposed method.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on differentially private (DP) machine learning, particularly those dealing with large-scale models and training tasks. It introduces a novel signal processing approach that significantly improves the efficiency of DP training by filtering noise. This opens up new avenues for applying DP to sensitive applications previously deemed impractical due to the performance trade-off.

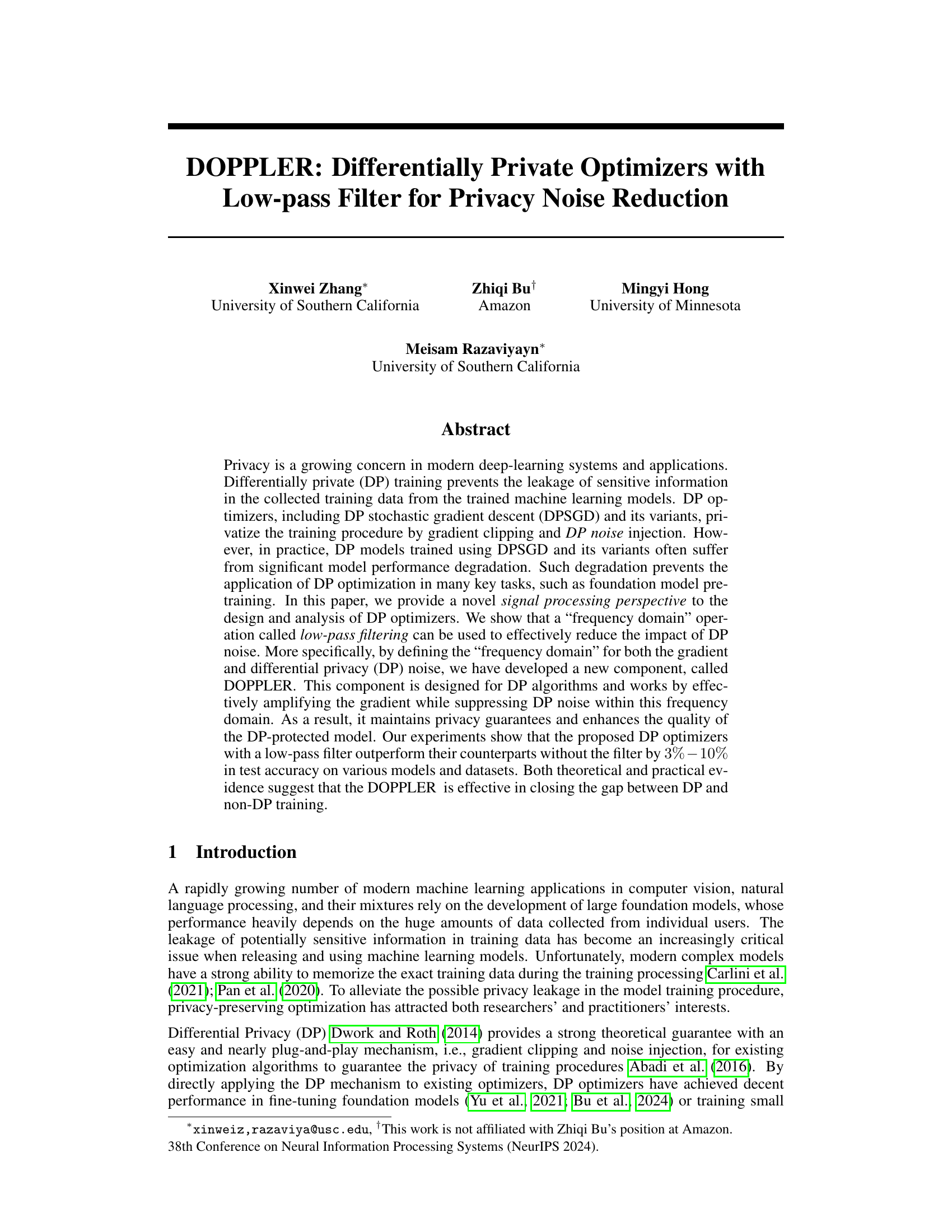

Visual Insights#

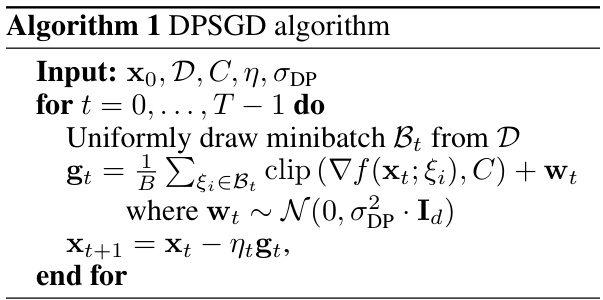

This figure demonstrates the concept of frequency domain analysis applied to gradient updates in differentially private optimization. Panel (a) shows the auto-correlation functions for both the gradient (blue) and noise (red) across different time lags (τ). The gradient exhibits high correlation for small lags, decaying as the lag increases, indicating a low-frequency signal. In contrast, the noise is only correlated with itself at a lag of zero (white noise). Panel (b) shows the power spectral density (PSD) corresponding to the auto-correlation functions in (a). The gradient’s PSD peaks at low frequencies, confirming its low-frequency nature. The noise, however, has a flat PSD across all frequencies. Panel (c) illustrates how an ideal low-pass filter can effectively separate the gradient signal from the high-frequency noise by allowing only the low-frequency components to pass through.

This table compares the test accuracy of different models on several language tasks using the ROBERTa-base model. The results are shown for different privacy budget levels (epsilon = 3 and epsilon = 8). It allows for comparison of the performance of different DP optimizers (DPAdam, DPAdamBC, and LP-DPAdamBC) under varying privacy constraints. The tasks evaluated are QQP, QNLI, MNLI, and SST-2.

In-depth insights#

DP Noise Filtering#

Differential Privacy (DP) mechanisms add noise to training data to protect individual privacy. However, this noise significantly degrades model accuracy. DP noise filtering techniques aim to mitigate this accuracy loss by selectively removing or reducing the impact of the added noise. These methods leverage signal processing principles, analyzing the frequency characteristics of the gradient updates and the noise. Low-pass filters are particularly effective, as they preserve the crucial low-frequency components of the gradients while suppressing high-frequency noise. The effectiveness of these filters is demonstrated empirically, showcasing improved model performance on various datasets and model architectures. The key challenge is to strike a balance: filtering too aggressively risks compromising the gradient information; insufficient filtering fails to reduce the impact of noise. Theoretical analysis often focuses on convergence rates and privacy guarantees, with advancements establishing the conditions for effective filtering without sacrificing privacy. Future research might explore adaptive filtering techniques that automatically adjust to the characteristics of both noise and gradient at each iteration, optimizing noise reduction based on signal-to-noise ratio in a dynamic manner.

Frequency Analysis#

Frequency analysis, in the context of this research paper, offers a novel perspective on differentially private (DP) optimizers. Instead of solely focusing on the time-domain characteristics of gradient updates, it examines the frequency spectrum of the gradients and noise. This shift reveals that the signal (gradient) is predominantly concentrated in lower frequencies, while the added DP noise is evenly distributed across all frequencies. This insight is crucial because it provides a basis for a new noise reduction strategy. By leveraging this frequency-domain information, the paper proposes a low-pass filtering method to selectively amplify low-frequency components (the true signal) and effectively suppress high-frequency noise. The theoretical analysis further supports this approach, showing a convergence guarantee while effectively managing the privacy budget. The effectiveness of this technique is demonstrated experimentally with significant improvement in the accuracy of DP-trained models.

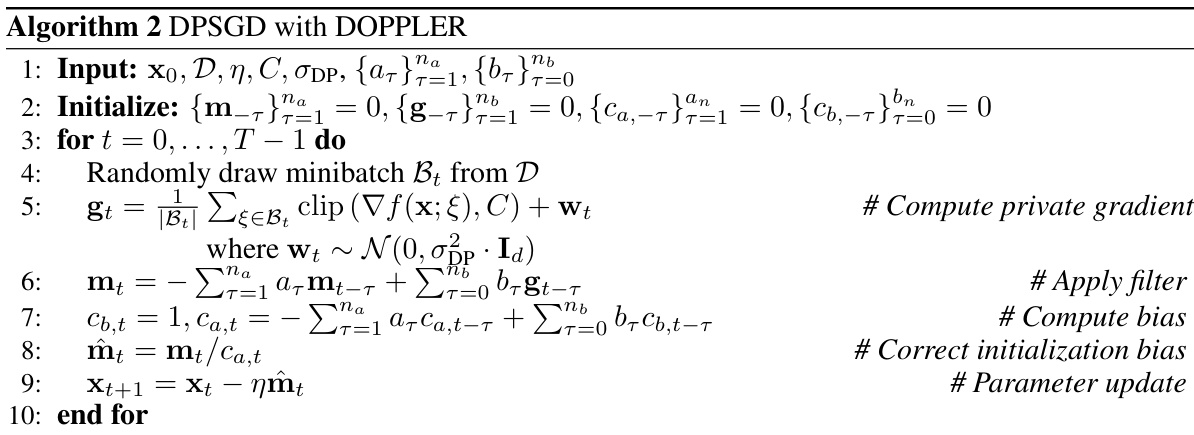

DOPPLER Module#

The DOPPLER module, as described in the context, is a novel signal processing component designed to enhance the performance of differentially private (DP) optimizers. Its core functionality involves a low-pass filter that operates in the frequency domain, distinguishing between the gradient signal and DP noise. By selectively amplifying low-frequency components (primarily the gradient signal) and suppressing high-frequency components (mostly the noise), DOPPLER effectively improves the signal-to-noise ratio. This approach is particularly beneficial for training large models where the accumulation of DP noise can severely degrade performance. The key advantage of DOPPLER lies in its orthogonal nature to existing DP noise reduction techniques. Unlike time-domain methods that target noise directly, DOPPLER works by enhancing the signal, thereby achieving improved accuracy without sacrificing privacy guarantees. The effectiveness of DOPPLER has been demonstrated through both theoretical analysis and empirical results, showcasing significant performance improvements across various models and datasets. Its compatibility with most existing optimizers further broadens its applicability and potential impact.

Empirical Results#

An Empirical Results section in a research paper should present findings in a clear, concise, and compelling manner. It needs to clearly state the metrics used to evaluate the proposed method (e.g., accuracy, precision, F1-score) and should compare these metrics to existing state-of-the-art methods. Visualizations like graphs and tables can enhance the understanding of the results, but they should be properly labeled and easy to interpret. Furthermore, the results should be discussed thoughtfully, noting any surprising or unexpected findings and attempting to provide explanations. A strong section will address any limitations of the experimental design and will also highlight the most significant contributions of the work. It should also consider the reproducibility of results and include details of experimental setup for transparency and validation.

Future of DP-SGD#

The future of DP-SGD hinges on addressing its limitations, primarily the trade-off between privacy and utility. Current methods struggle to achieve high accuracy while maintaining strong privacy guarantees, particularly when training large models. Future research should focus on improving the efficiency and scalability of DP-SGD, potentially through advanced noise injection techniques, more sophisticated clipping mechanisms, or alternative optimization methods. Adaptive privacy mechanisms that dynamically adjust noise based on the sensitivity of the gradients are promising. Exploring new theoretical frameworks for analyzing the convergence and privacy properties of DP-SGD under various assumptions is also crucial. Additionally, investigating how DP-SGD can be effectively combined with other privacy-enhancing techniques and model architectures could unlock significant improvements. Finally, exploring alternative DP optimization algorithms beyond SGD, which might be less sensitive to noise, represents a key area of research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

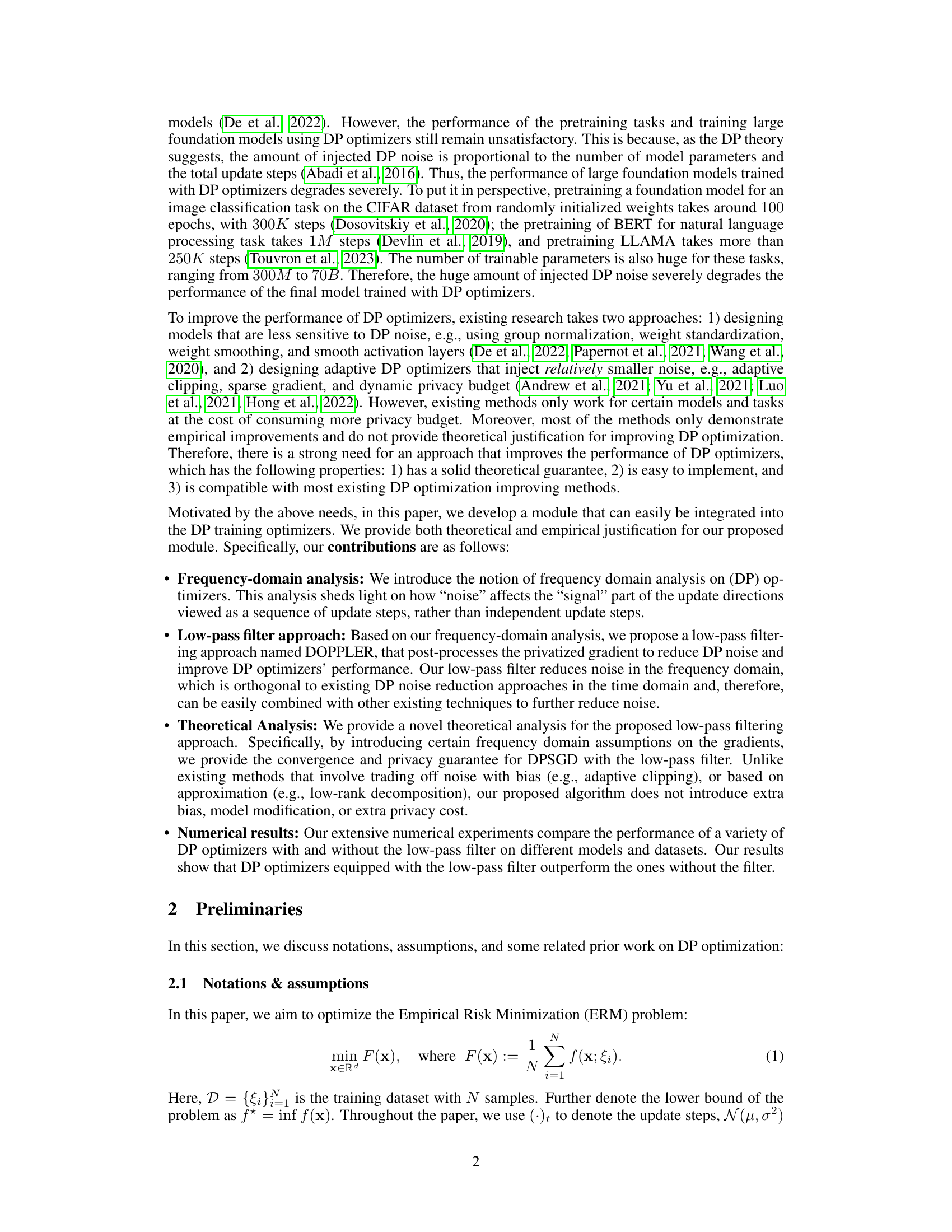

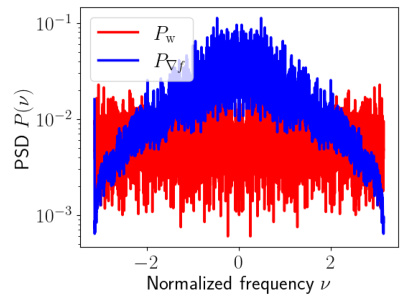

The figure shows the power spectral density (PSD) plots of the Gaussian noise and the stochastic gradients. The PSD of the Gaussian noise is flat across all frequencies, indicating white noise. In contrast, the PSD of the stochastic gradients shows a concentration of power at lower frequencies, indicating that the gradients are not white noise but exhibit correlation across iterations. Applying the low-pass filter to the gradients reduces the high-frequency components and enhances the signal-to-noise ratio. The low-pass filter is applied to suppress noise components, which makes the gradient have a better signal-to-noise ratio. The figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed low-pass filter in reducing the impact of DP noise by separating the signal (gradient) from the noise in the frequency domain.

This figure shows the Power Spectral Density (PSD) plots for the Gaussian noise (wt) and the stochastic gradients obtained using both standard SGD and the proposed LP-SGD method during the training of a ResNet-50 model on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The PSD of the noise shows a relatively flat distribution across all frequencies, indicating white noise characteristics. In contrast, the PSDs of the gradients from both methods are concentrated around lower frequencies, signifying that the gradient signal has less power at higher frequencies. Notably, the LP-SGD gradient PSD demonstrates a more pronounced suppression of high-frequency components, indicating that the low-pass filter effectively reduces high-frequency noise without significant alteration of the main signal.

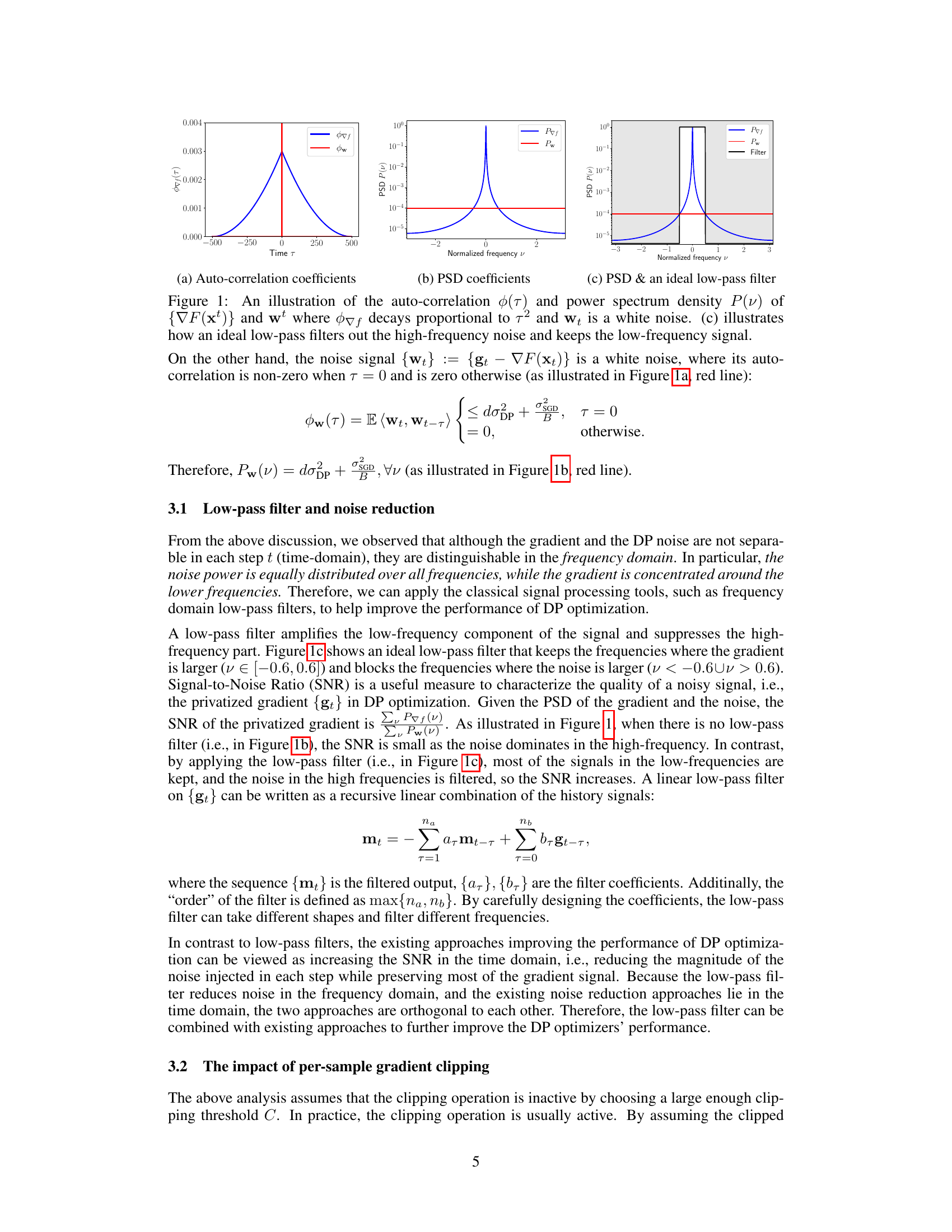

This figure compares the performance of DPSGD and LP-DPSGD (DPSGD with the proposed low-pass filter) during the pre-training phase on three different datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and MNIST. Each subfigure shows the test accuracy over epochs for both algorithms on a specific dataset. The results illustrate that LP-DPSGD consistently outperforms DPSGD across all three datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness of the low-pass filter in improving the performance of DP optimizers.

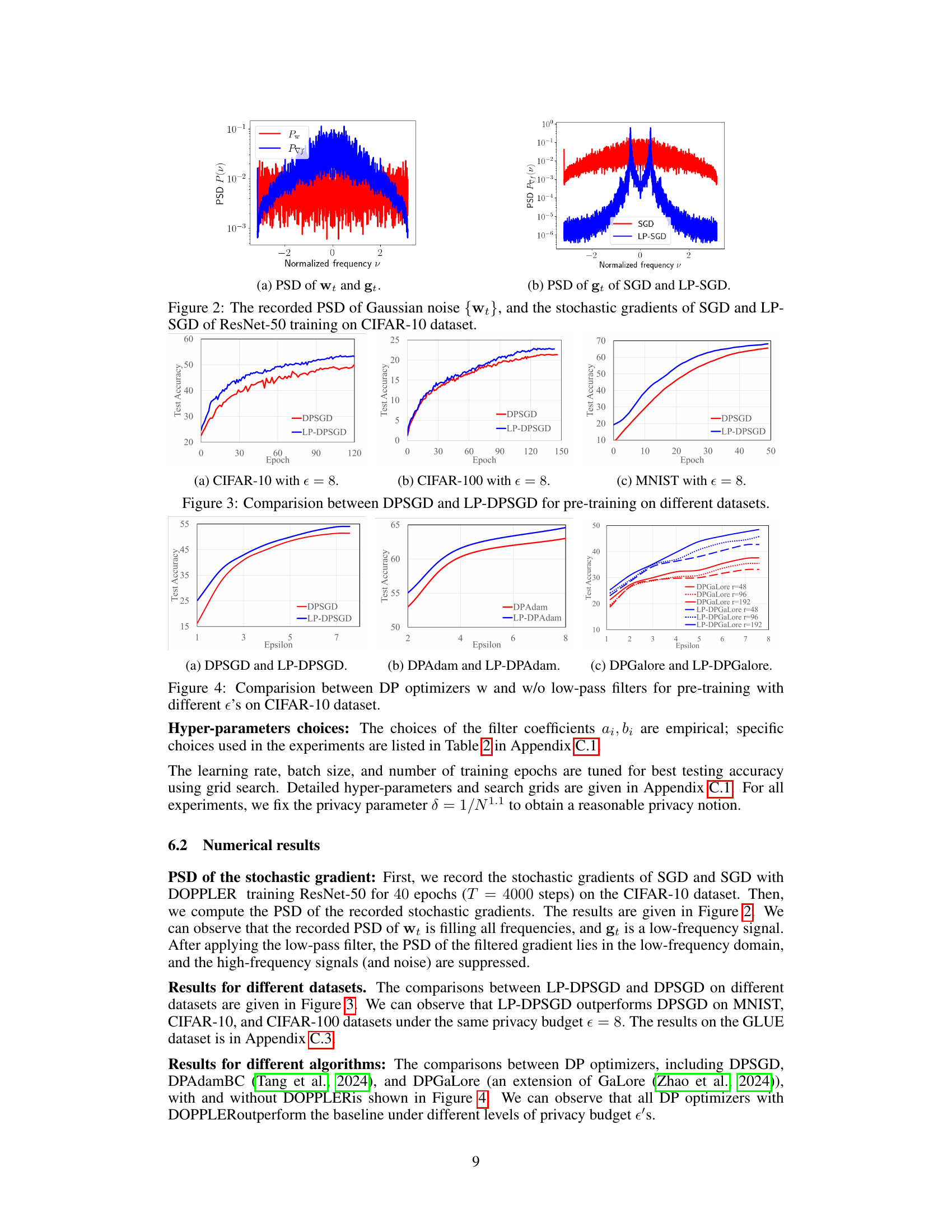

This figure compares the performance of three different differentially private (DP) optimizers (DPSGD, DPAdam, and DPGaLore) with and without the low-pass filter (LP) proposed in the paper. The comparison is done across various privacy budgets (epsilon values) during the pre-training phase on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The results show how the low-pass filter improves the test accuracy of each DP optimizer for different levels of privacy protection.

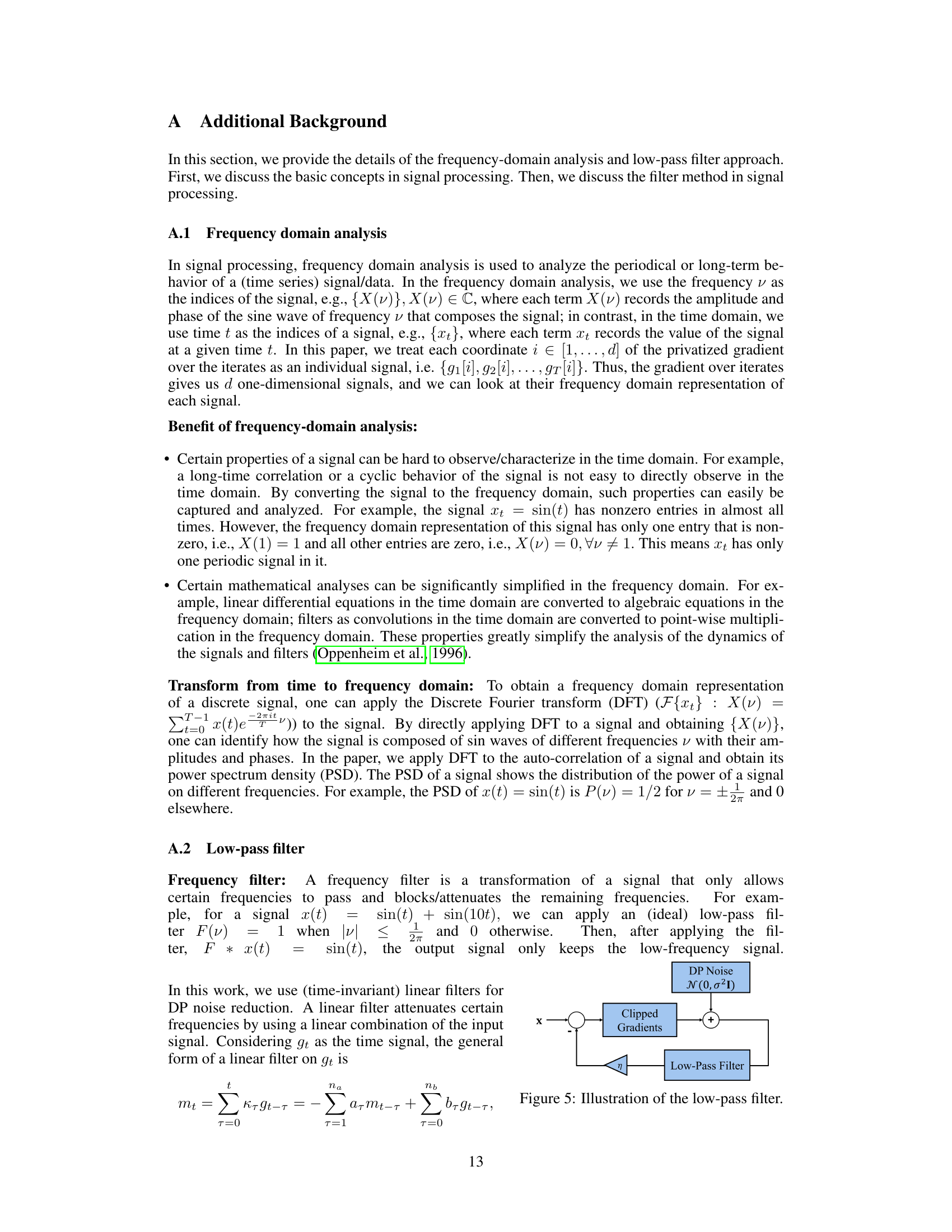

This figure illustrates how the low-pass filter works in the context of differentially private (DP) optimization. The input is the clipped gradients, which are then added to DP noise. Finally, the low-pass filter processes the noisy gradient to reduce the noise.

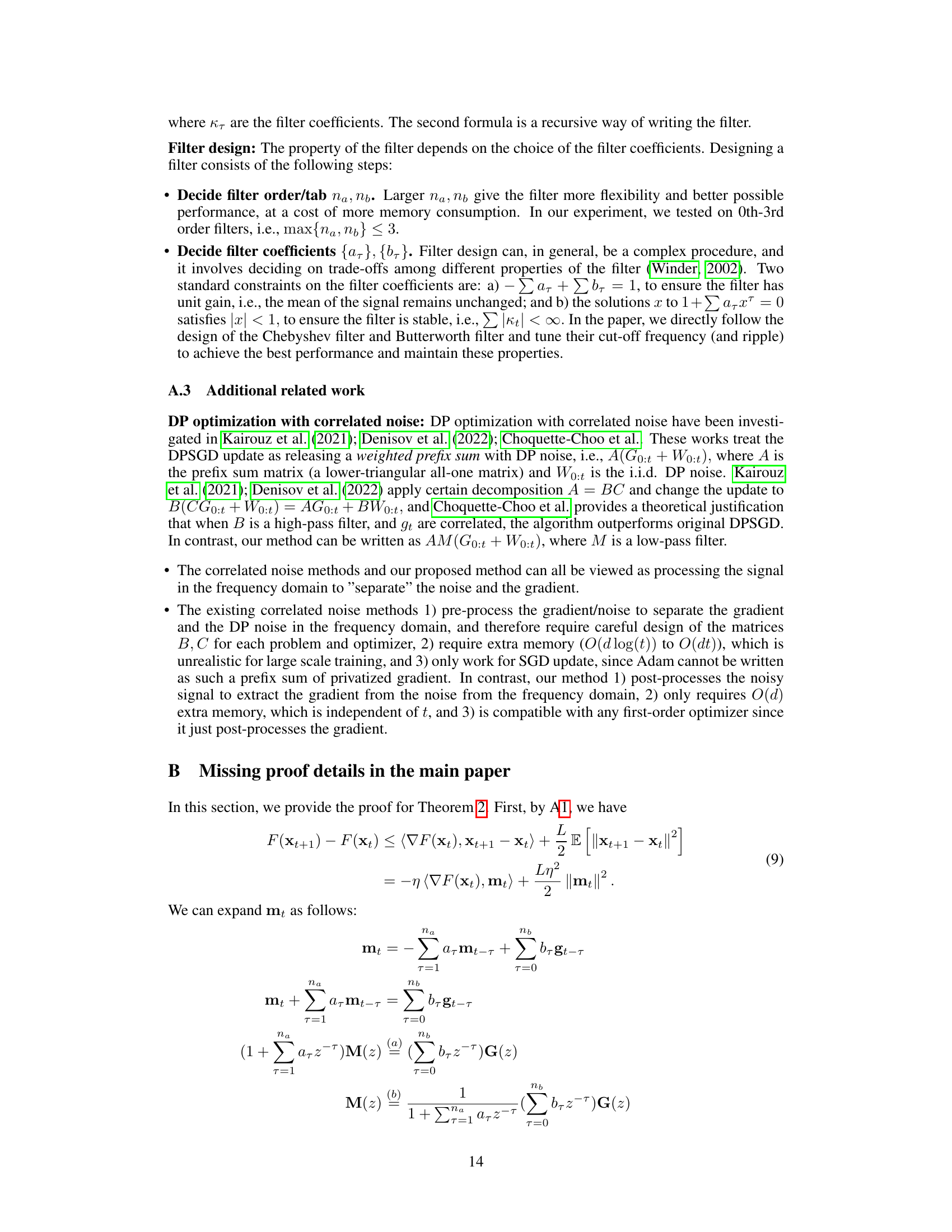

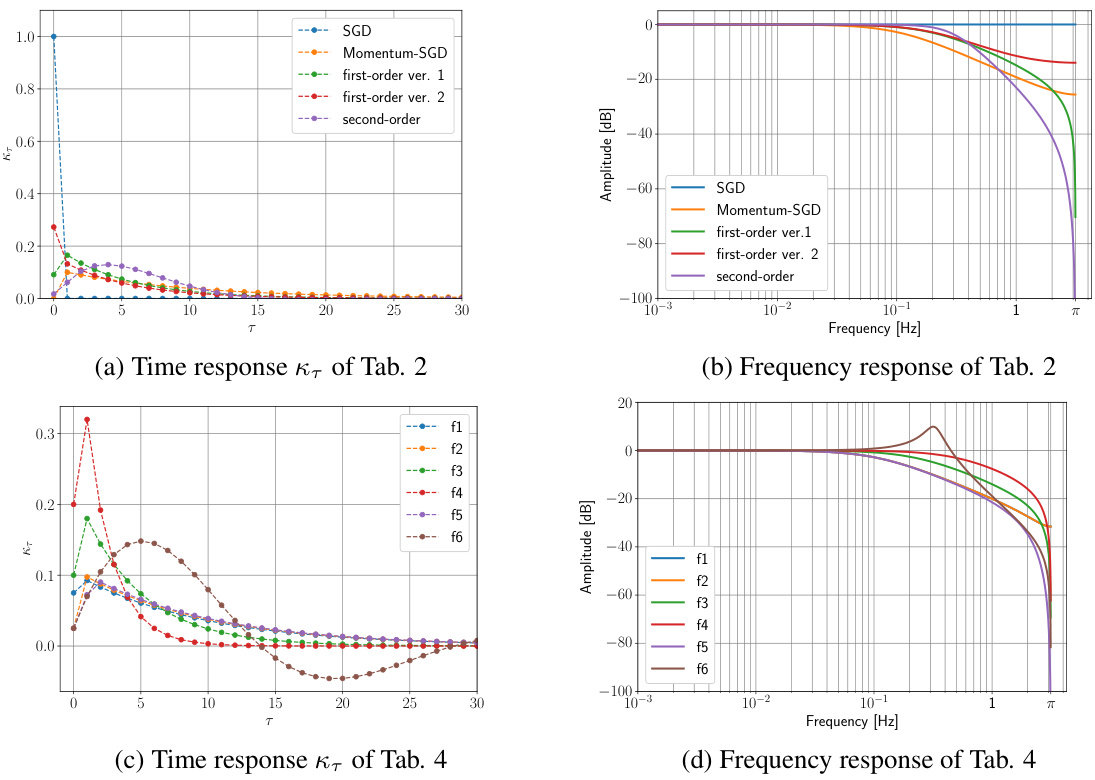

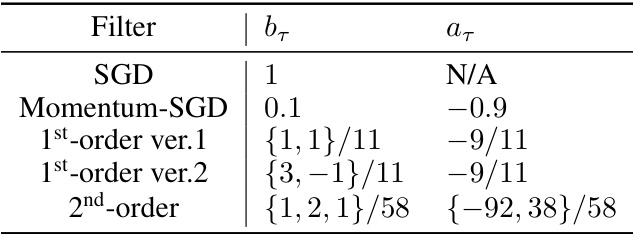

This figure visualizes the time and frequency responses of various filters used in the paper. Specifically, it illustrates the auto-correlation coefficients (time response) and power spectral density (frequency response) for several filter designs: SGD (no filter), Momentum-SGD, and first and second-order filters. This helps to understand how the different filter designs affect the balance between attenuating high-frequency noise and preserving low-frequency signal components of the gradients during training.

This figure shows the power spectral density (PSD) plots for Gaussian noise and the stochastic gradients obtained from training a ResNet-50 model on the CIFAR-10 dataset using both standard SGD and the proposed LP-SGD (low-pass filter SGD) methods. The PSD is a way to visualize how the power of the signal is distributed across different frequencies. In the context of this paper, the low-frequency components correspond to the actual gradient signal, while the high-frequency components are associated with the noise added for differential privacy. The figure visually demonstrates how the LP-SGD method effectively suppresses the noise, which is particularly useful in differential privacy applications where the goal is to protect sensitive data while still obtaining accurate gradients.

The figure compares the performance of DPSGD and LP-DPSGD (DPSGD with the low-pass filter) on four different models (5-layer CNN, Vit-small, EfficientNet, and ResNet-50) for pre-training on the CIFAR-10 dataset with a privacy budget (epsilon) of 8. Each subplot shows the test accuracy over epochs for a specific model, illustrating how the low-pass filter improves accuracy. The results highlight the consistent improvement in performance offered by the low-pass filter across diverse model architectures.

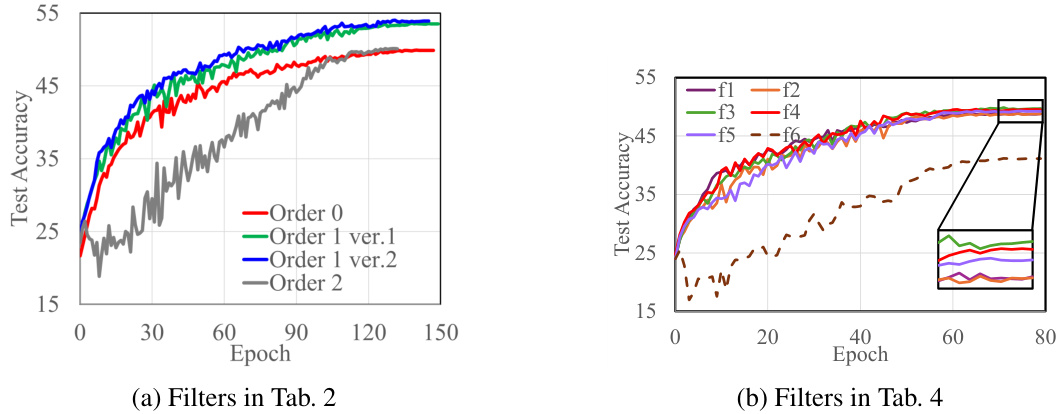

This figure compares the performance of the LP-DPSGD optimizer on the CIFAR-10 dataset using different low-pass filter coefficients. Subfigure (a) shows the results for filters described in Table 2 of the paper. Subfigure (b) shows the results for filters described in Table 4 of the paper. The different filter configurations demonstrate varying impacts on the training process and final test accuracy. The results illustrate the effectiveness of appropriately chosen low-pass filter in enhancing the performance of differentially private optimizers by reducing the noise introduced by the privacy mechanism.

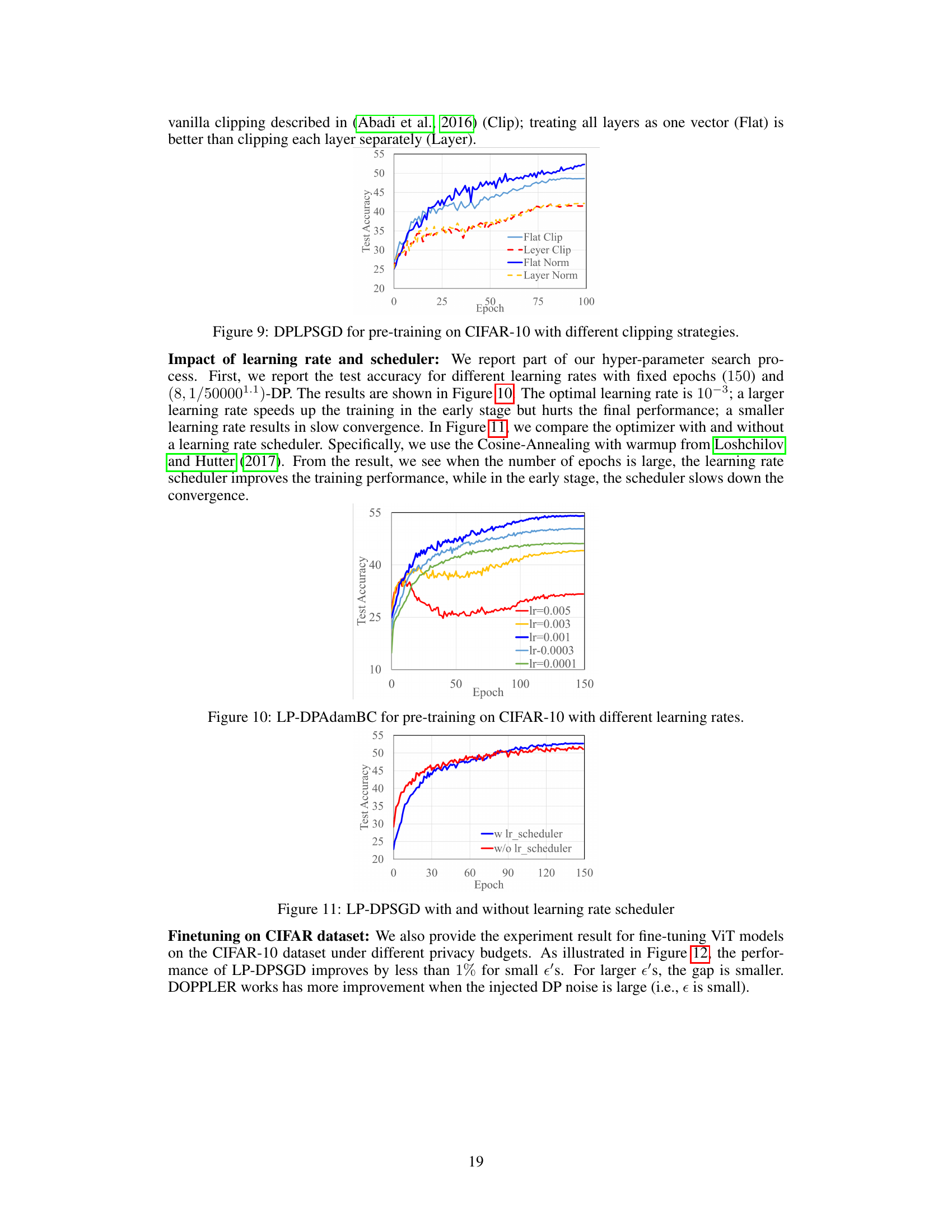

This figure shows the impact of different clipping strategies on the performance of the DP-LPSGD optimizer during pre-training on the CIFAR-10 dataset. Four different clipping methods are compared: Flat Clip (clipping the entire gradient vector), Layer Clip (clipping each layer’s gradient separately), Flat Norm (normalizing the entire gradient vector before clipping), and Layer Norm (normalizing each layer’s gradient before clipping). The x-axis represents the training epoch, and the y-axis represents the test accuracy. The results indicate that Flat Norm significantly outperforms other clipping strategies.

The figure shows the impact of different learning rates on the test accuracy of the LP-DPAdamBC optimizer during the pre-training phase on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It illustrates how the learning rate affects the convergence speed and the final test accuracy. A learning rate that is too high may lead to instability and prevent convergence to a good solution, while a learning rate that is too low will cause slow convergence and might not reach a good final accuracy. The optimal learning rate provides the balance between these two effects, leading to fast convergence and high accuracy.

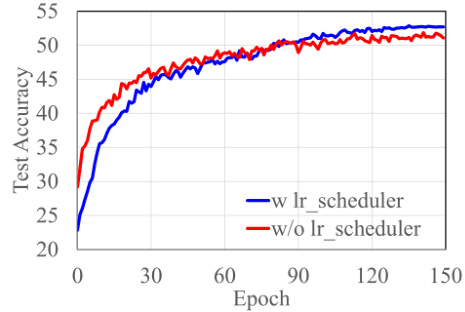

This figure compares the performance of the LP-DPSGD optimizer with and without a learning rate scheduler (Cosine-Annealing with warmup). The results show that when the number of epochs is large, using a learning rate scheduler improves the training performance. However, in the early stages of training, the scheduler slows down convergence.

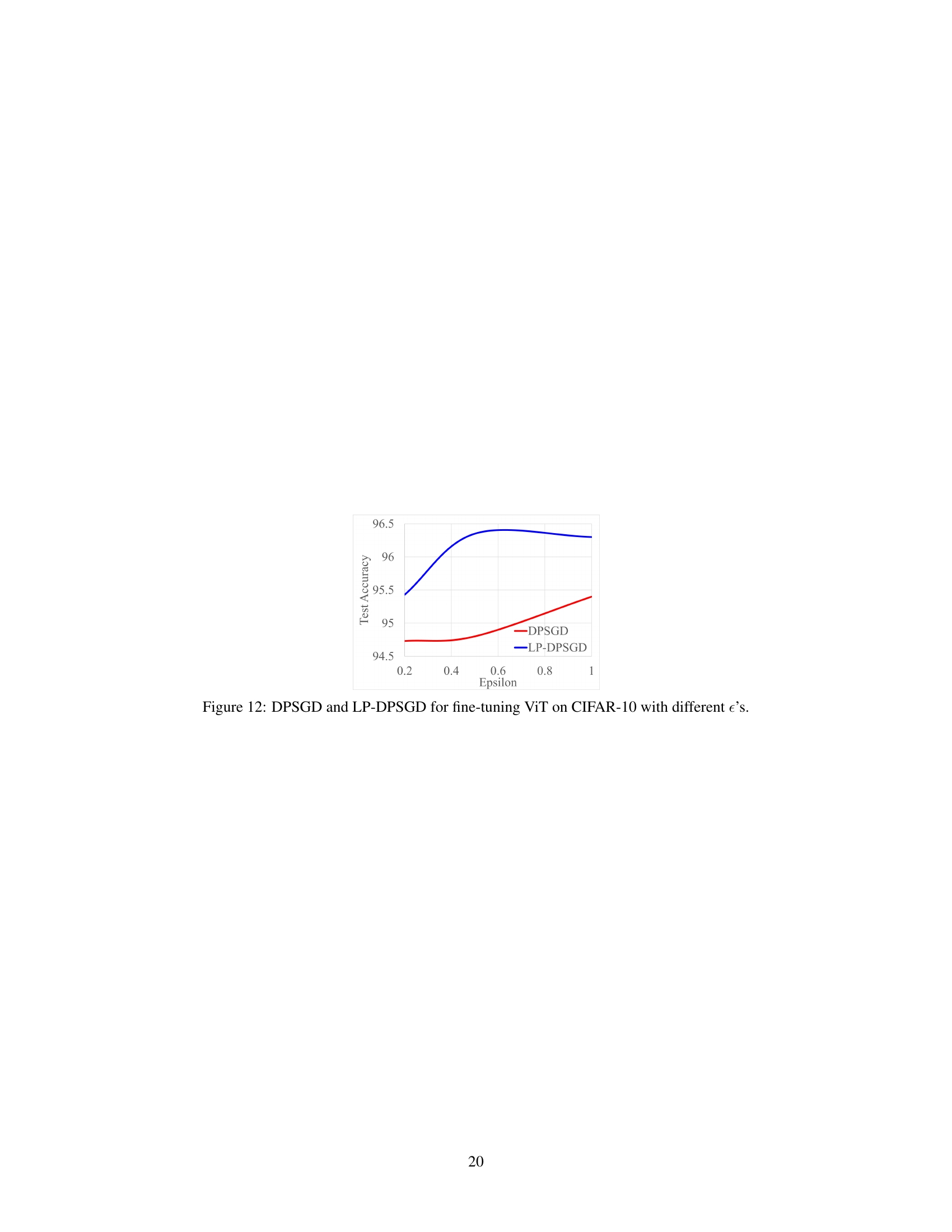

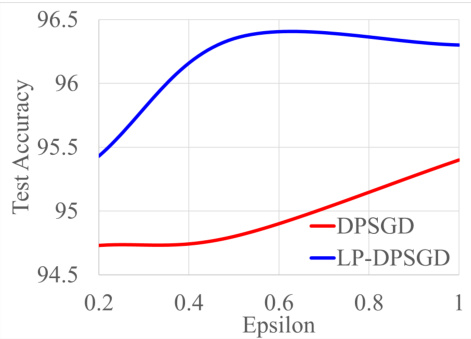

This figure shows the test accuracy of DPSGD and LP-DPSGD for fine-tuning a Vision Transformer (ViT) model on the CIFAR-10 dataset with varying privacy budgets (epsilon). The x-axis represents the privacy parameter epsilon, and the y-axis represents the test accuracy. The blue line represents LP-DPSGD, which incorporates a low-pass filter, while the red line represents standard DPSGD. The figure demonstrates the performance comparison of both methods under different levels of privacy protection.

More on tables

This table compares the test accuracy of different DP optimizers on various language tasks using the ROBERTa-base model. The results are presented for two different privacy budget values (epsilon = 3 and epsilon = 8), showing the impact of the privacy budget and the optimizer on the final performance. It specifically highlights the performance differences between different DP optimizers and their enhanced versions utilizing DOPPLER.

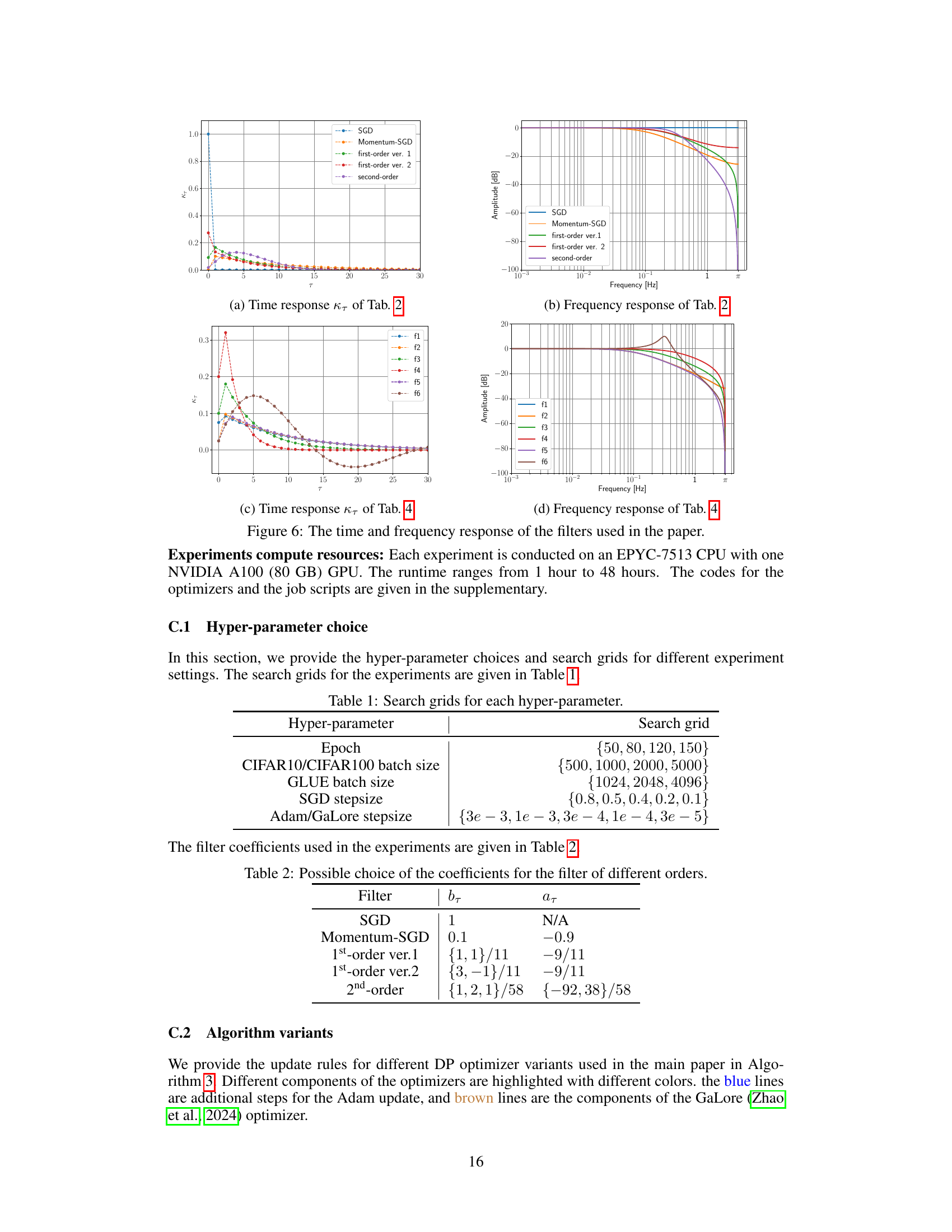

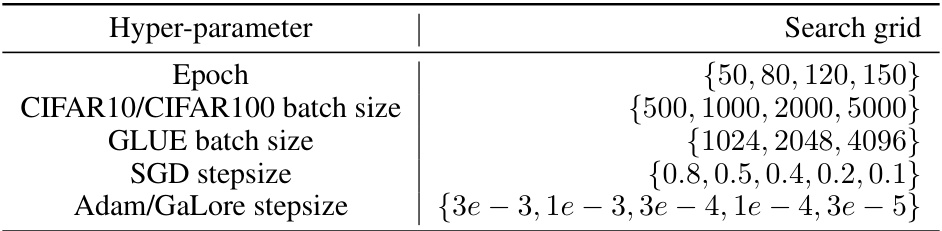

This table shows the range of hyper-parameters used in the grid search for different experiments in the paper. The hyper-parameters include the number of epochs, batch size for CIFAR10/CIFAR100 and GLUE datasets, and the learning rates for SGD, Adam, and GaLore optimizers.

This table lists the coefficients used for filters of different orders (0th to 2nd order). The coefficients determine the characteristics of the low-pass filter applied to the gradients in the DOPPLER method. Different filter orders offer different tradeoffs between computational cost and the effectiveness of noise reduction. The choices provided are based on empirical experimentation.

This table presents the results of fine-tuning a RoBERTa-base model on the GLUE benchmark dataset using different differentially private (DP) optimization methods. The table shows test accuracy scores across multiple tasks (MNLI, QQP, QNLI, SST-2) for two different privacy budgets (ϵ = 3 and ϵ = 8). The methods compared include DPAdam from existing literature and DPAdamBC and its variant with the low-pass filter (LP-DPAdamBC) proposed in this paper.

This table shows various choices of filter coefficients (a_τ and b_τ ) for low-pass filters of different orders (max{n_a, n_b}). The filter coefficients influence the frequency response of the filter, impacting how the filter attenuates high-frequency noise and passes low-frequency signal. Different choices lead to various trade-offs between the filter’s performance. For example, higher-order filters can provide more flexibility in shaping the frequency response but may require more computational resources.

Full paper#