↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are expensive to run, especially with long sequences, largely due to the computationally intensive self-attention mechanism. This often involves fetching the entire preceding state from memory at each step, creating memory and computational bottlenecks. Several strategies exist to mitigate this, but often with a trade-off in accuracy.

This paper introduces Loki, a sparse attention method that addresses this by focusing on the dimensionality of key vectors in the self-attention mechanism. The authors show that these vectors consistently occupy a much lower-dimensional space across various models and datasets. Loki leverages this to rank and select tokens in the KV-cache based on low-dimensional attention scores, efficiently computing full-dimensional scores only for the selected tokens. This approach achieves substantial speedups (up to 45%) while preserving model accuracy better than many existing sparse attention methods. Loki’s efficiency is further boosted by optimized Triton kernels, minimizing data movement and computation. The findings provide valuable insights for future research in efficient LLM inference.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on large language models (LLMs) and efficient deep learning. It offers a novel approach to speed up the computationally expensive self-attention mechanism while maintaining accuracy. This is a significant advancement given the growing size and cost of LLMs, making the research highly relevant to current trends in AI. Furthermore, the discovery of the low-dimensionality of key vectors opens new avenues for improving the efficiency of LLMs, inviting further research in exploring this property.

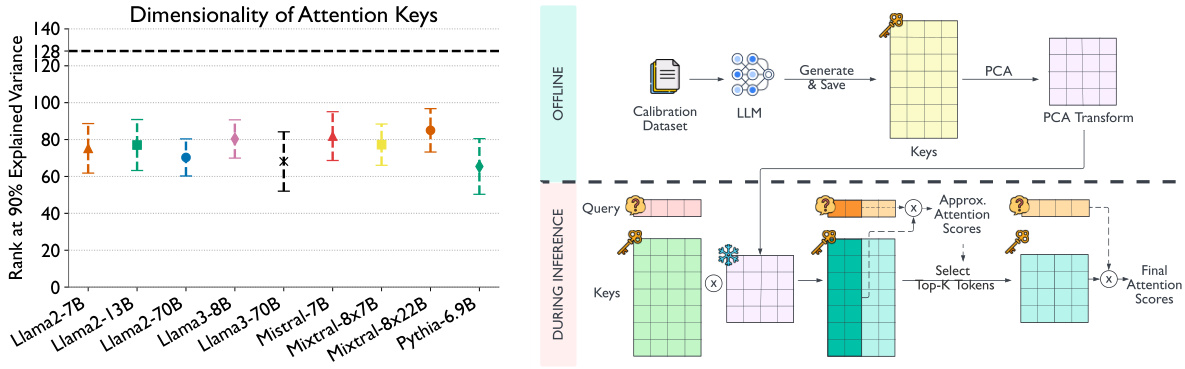

Visual Insights#

The left plot shows the dimensionality of attention keys across various large language models. It demonstrates that a surprisingly small number of principal components (around 80) explain 90% of the variance in the key vectors, despite the key vectors having a much larger dimensionality (e.g., 128). This observation motivates the Loki method. The right plot provides a visual overview of the Loki algorithm: during offline calibration, PCA is used to obtain a low-dimensional representation of the key vectors, which is then used during inference to efficiently select the most relevant tokens based on approximate attention scores. Finally, the full-dimensional keys are used to compute the final attention scores for the selected tokens.

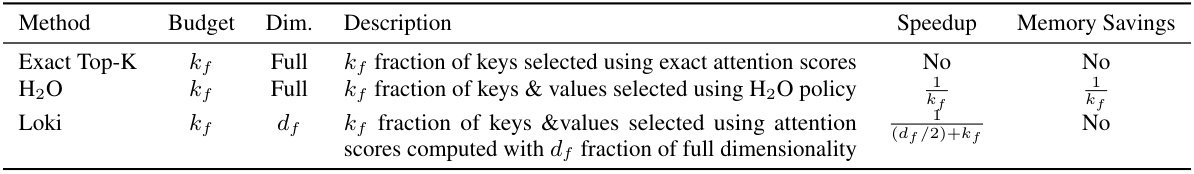

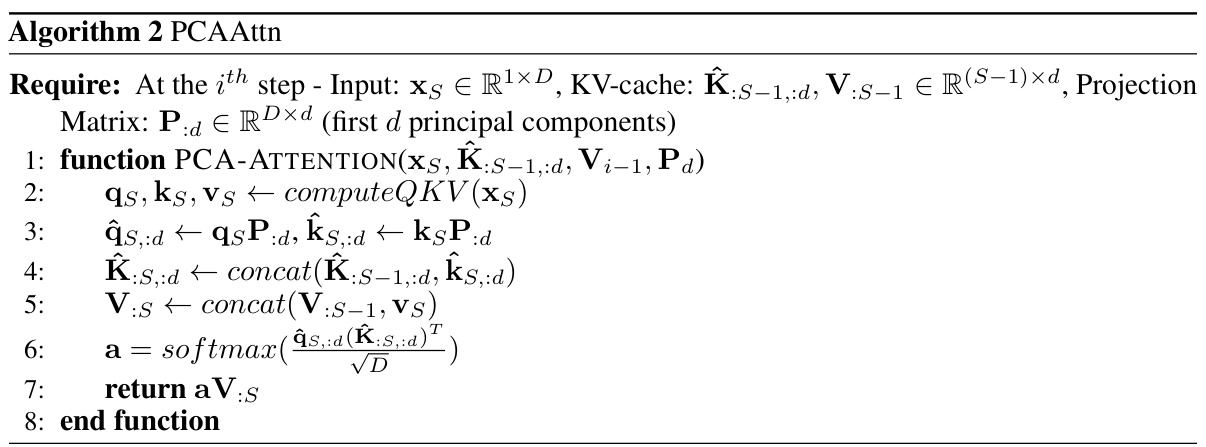

This table compares three different sparse attention methods: Exact Top-K, H2O, and Loki. For each method, it specifies the budget (fraction of keys or keys & values used), the dimensionality of the keys used for attention score computation, a description of the method, the expected speedup compared to full attention, and any memory savings. Exact Top-K computes exact attention scores for a subset of keys; H2O uses a heuristic to select keys & values, and Loki uses low-dimensional projections of the keys to select keys & values for efficient attention.

In-depth insights#

Low-Rank Attention Keys#

The concept of “Low-Rank Attention Keys” introduces a novel approach to optimizing the efficiency of attention mechanisms, a critical component of large language models (LLMs). The core idea revolves around the observation that key vectors in attention layers, despite their high dimensionality, often exhibit a significantly lower effective rank. This means that these vectors lie within a much smaller subspace, characterized by a few principal components. Exploiting this low-rank property offers the potential for significant computational savings. By employing dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), these key vectors can be efficiently represented in a lower-dimensional space, significantly reducing the computational burden of the dot product calculations at the heart of the attention mechanism. This approach not only accelerates inference but also minimizes memory requirements, as the reduced-dimension key vectors occupy less storage. This strategy, in essence, achieves a form of attention sparsity by focusing on the most relevant information within the key vectors, rather than relying on uniform sparsity patterns that might discard valuable information. The effectiveness of this approach is supported by theoretical analysis and empirical evaluations, demonstrating that significant speedups can be achieved without compromising the model’s accuracy. This technique presents a promising avenue for improving the scalability and efficiency of LLMs, paving the way for deploying larger and more complex models with reduced computational costs and energy consumption.

Loki: Sparse Attention#

Loki, a novel sparse attention mechanism, tackles the computational burden of large language models (LLMs) by focusing on the low-dimensional nature of key vectors within the self-attention block. Instead of directly pruning or employing fixed sparsity patterns, Loki dynamically selects key tokens based on attention scores calculated in a lower-dimensional space, offering a more efficient and accurate approximation. This approach is grounded in a detailed analysis demonstrating the consistent low dimensionality of key vectors across various models and datasets. By leveraging PCA for dimensionality reduction and employing optimized Triton kernels, Loki achieves significant speedups without substantial loss in model quality. The method demonstrates efficiency gains through reduced data movement and compute costs while maintaining the efficacy of the models. Although Loki’s primary focus is on accelerating computation, the inherent low-rank structure of attention keys opens avenues for future research in memory optimization and further performance enhancements for LLMs. The method is shown to be generalizable across different datasets and models, improving computational efficiency and paving the way for more efficient LLM deployments.

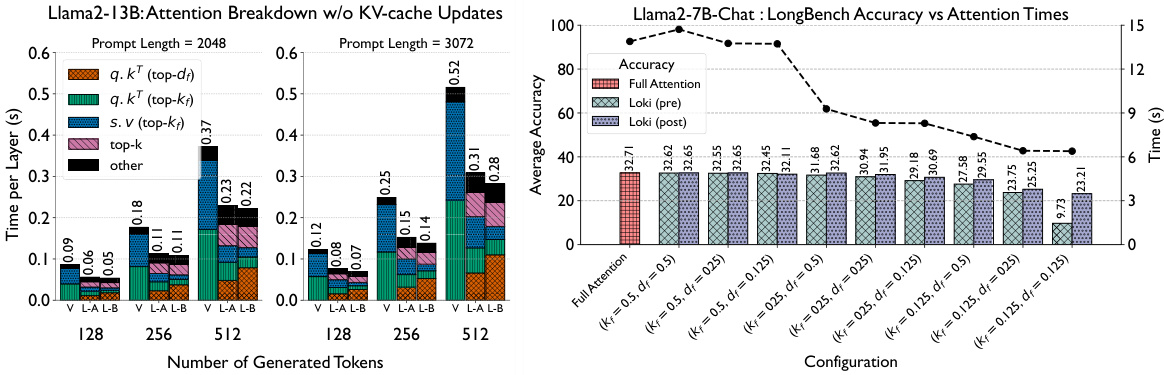

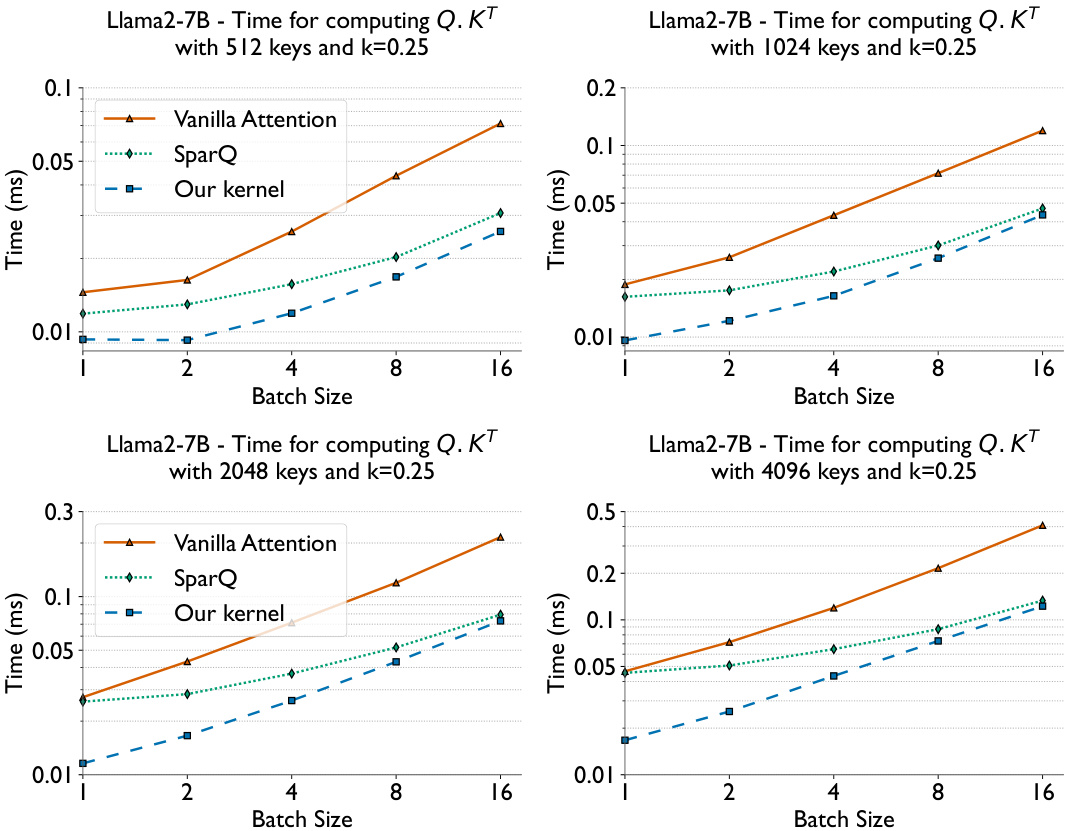

Loki’s Computational Cost#

Loki’s computational efficiency is a crucial aspect of its design. The paper highlights that Loki’s speedup stems from reduced data movement and computation, achieved by focusing on the low dimensionality of key vectors in the self-attention mechanism. Loki leverages PCA to identify a lower-dimensional representation of key vectors, significantly reducing the computational burden of attention calculations. By computing attention scores in this low-dimensional space and then selecting top-k tokens, Loki achieves a substantial speedup over standard attention while maintaining accuracy. The paper presents a detailed theoretical complexity analysis supporting this claim. Implementation of Loki using Triton further optimizes performance by minimizing data movement and leveraging GPU register operations. This contributes to substantial speedups over both standard and existing sparse attention methods, empirically validated in experiments. However, the impact of KV-cache append operations remains a limiting factor, suggesting potential for further optimization via improved inference systems or more efficient KV-cache management techniques.

Loki’s Generalizability#

The generalizability of Loki, a sparse attention mechanism, is a critical aspect of its practical value. The core idea hinges on the low-dimensionality of attention keys, a property discovered across various LLMs and datasets. Loki’s effectiveness relies on this inherent characteristic being consistent across models and datasets not used in its training. The paper investigates this by applying PCA to key vectors from diverse models and datasets, consistently finding a low-rank structure. This demonstrates that the low-dimensional representation isn’t a model-specific artifact but a general property of attention mechanisms. The success of Loki’s transferable PCA transformations highlights its robustness and scalability, implying the method is not narrowly tailored to specific models or datasets. This is further validated by experiments showing comparable performance across different calibration datasets, thereby confirming the widespread applicability and reliability of the core assumption behind Loki’s design.

Future Work on Loki#

Future work on Loki could explore several promising avenues. Improving memory efficiency is crucial; Loki currently doesn’t directly address the quadratic memory scaling of self-attention. Integrating techniques like KV-cache offloading to CPU or employing more aggressive token pruning methods could synergistically enhance both speed and memory usage. Extending Loki’s applicability to different modalities beyond natural language is another area worthy of investigation. The low-rank nature of attention keys might be a universal property, making Loki a potential candidate for vision or other modalities. Investigating the optimal choice of dimensionality reduction (d and k) is another important direction; adaptive or dynamic strategies to determine these parameters based on context or input properties could further boost performance and accuracy. Enhancing Loki’s robustness is key: evaluating its performance under various conditions (noisy data, shorter sequences, etc.) and developing strategies to handle these scenarios effectively will make Loki a more reliable and practical solution. Finally, detailed analysis of the interplay between Loki and other optimization techniques (e.g., quantization, FlashAttention) should be conducted to fully realize the potential for significant efficiency gains in large language models.

More visual insights#

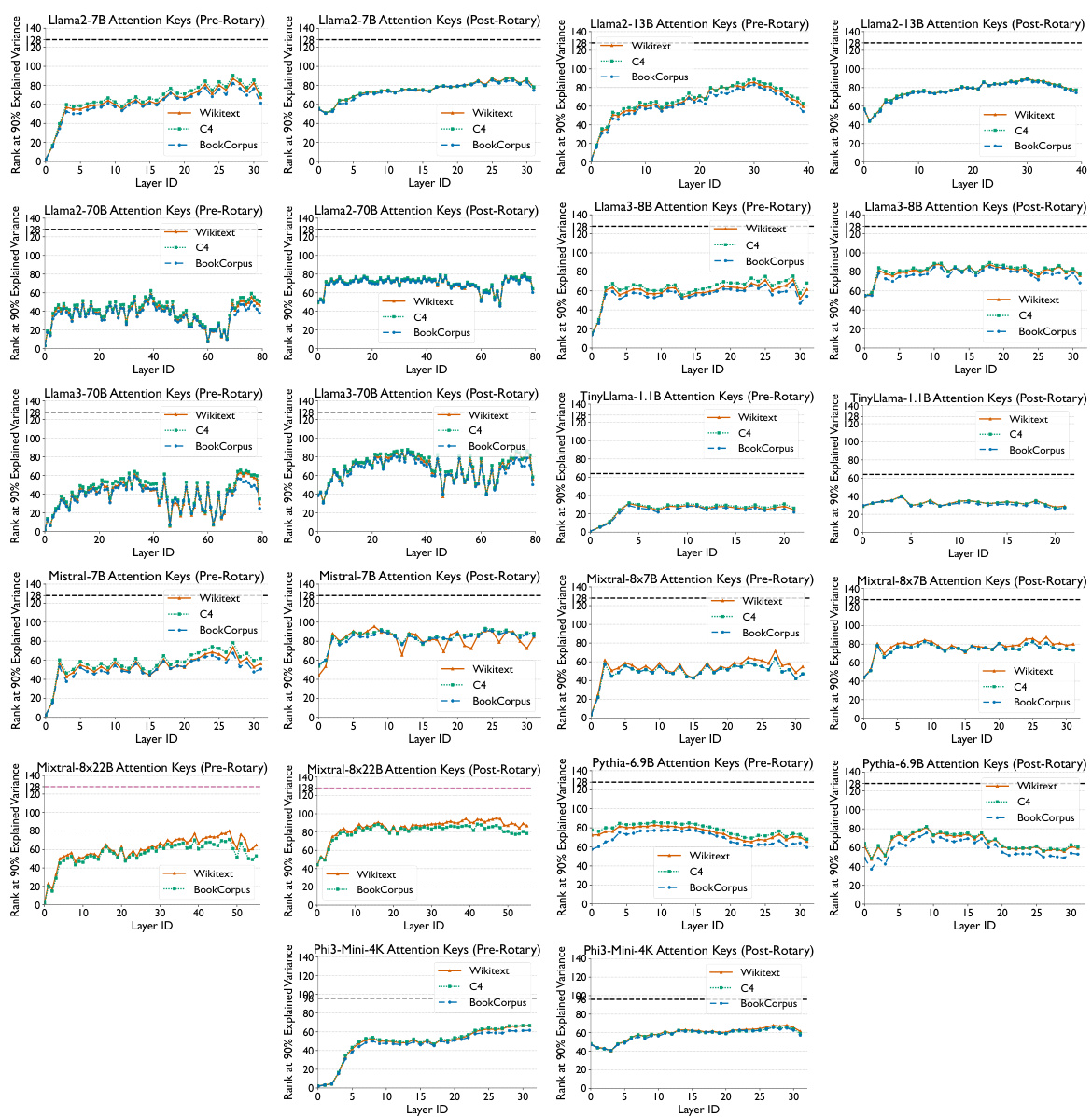

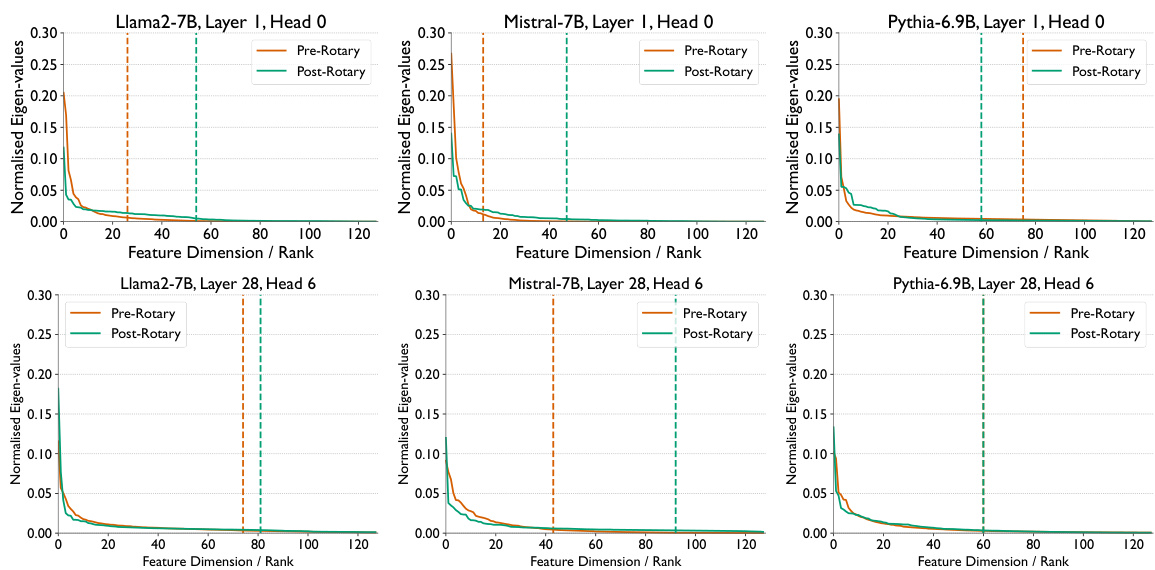

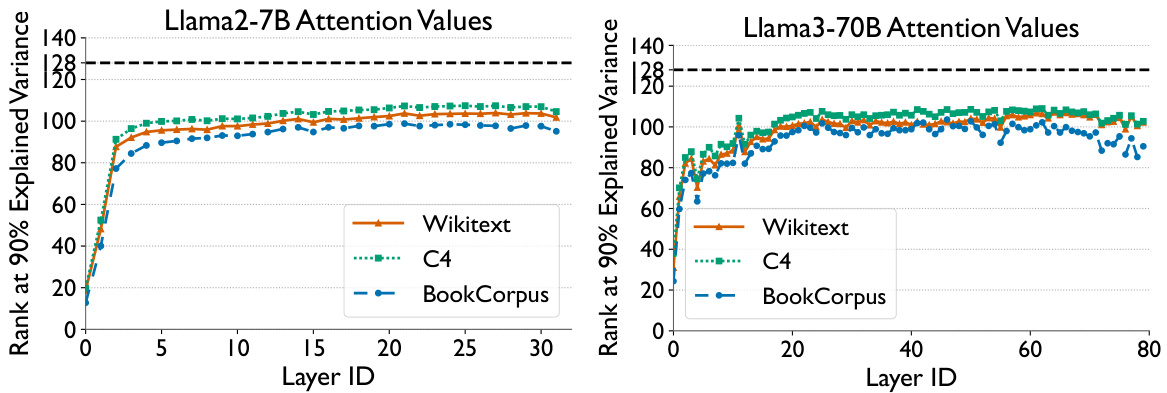

More on figures

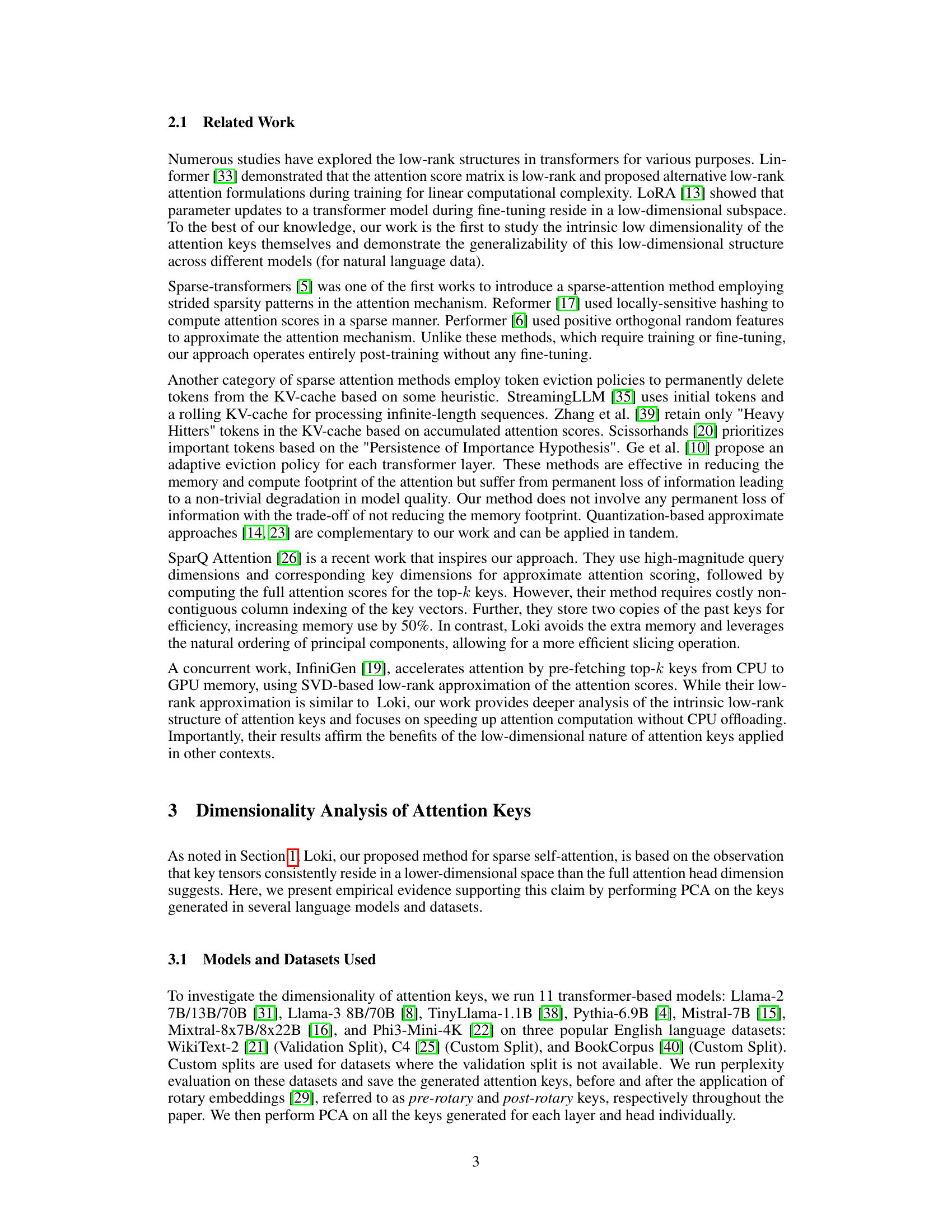

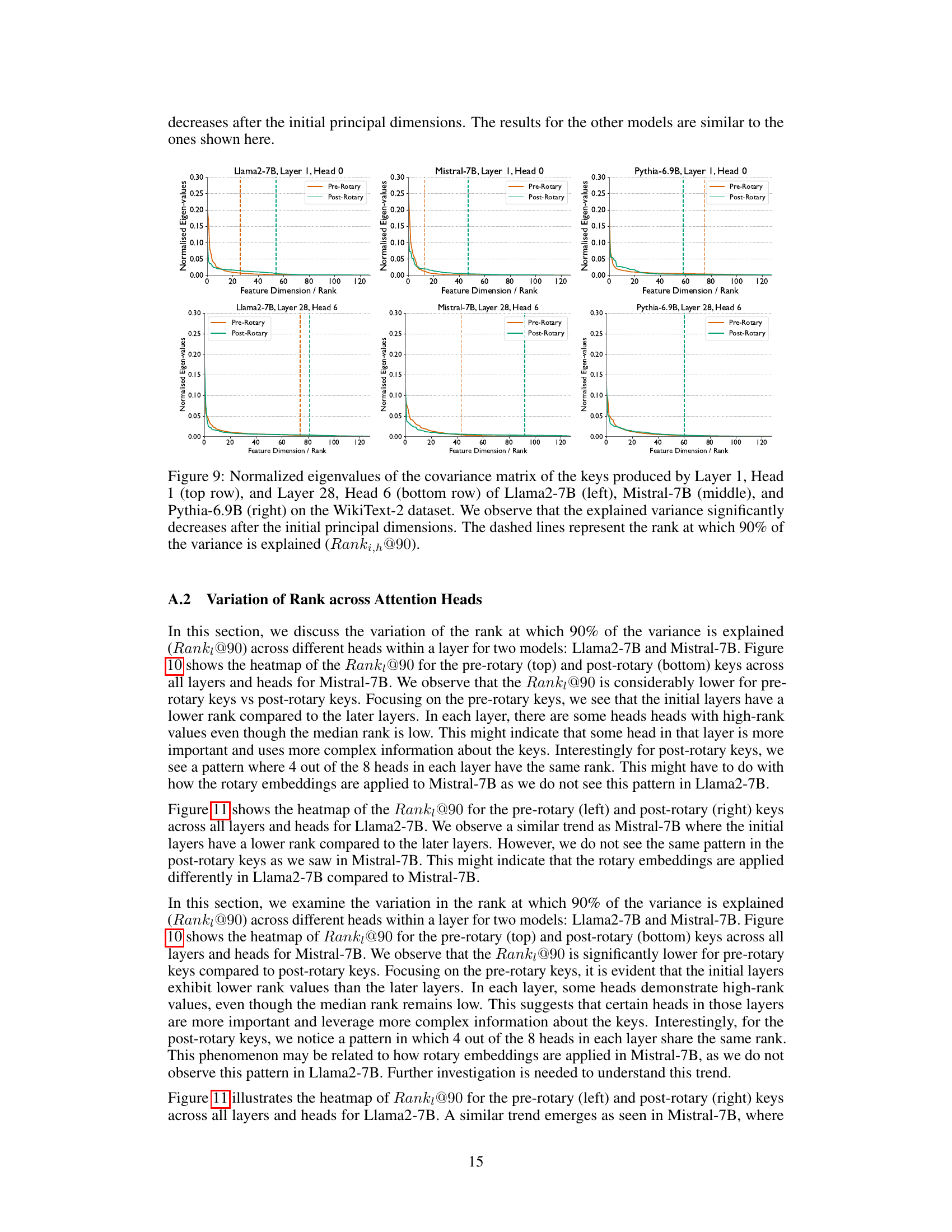

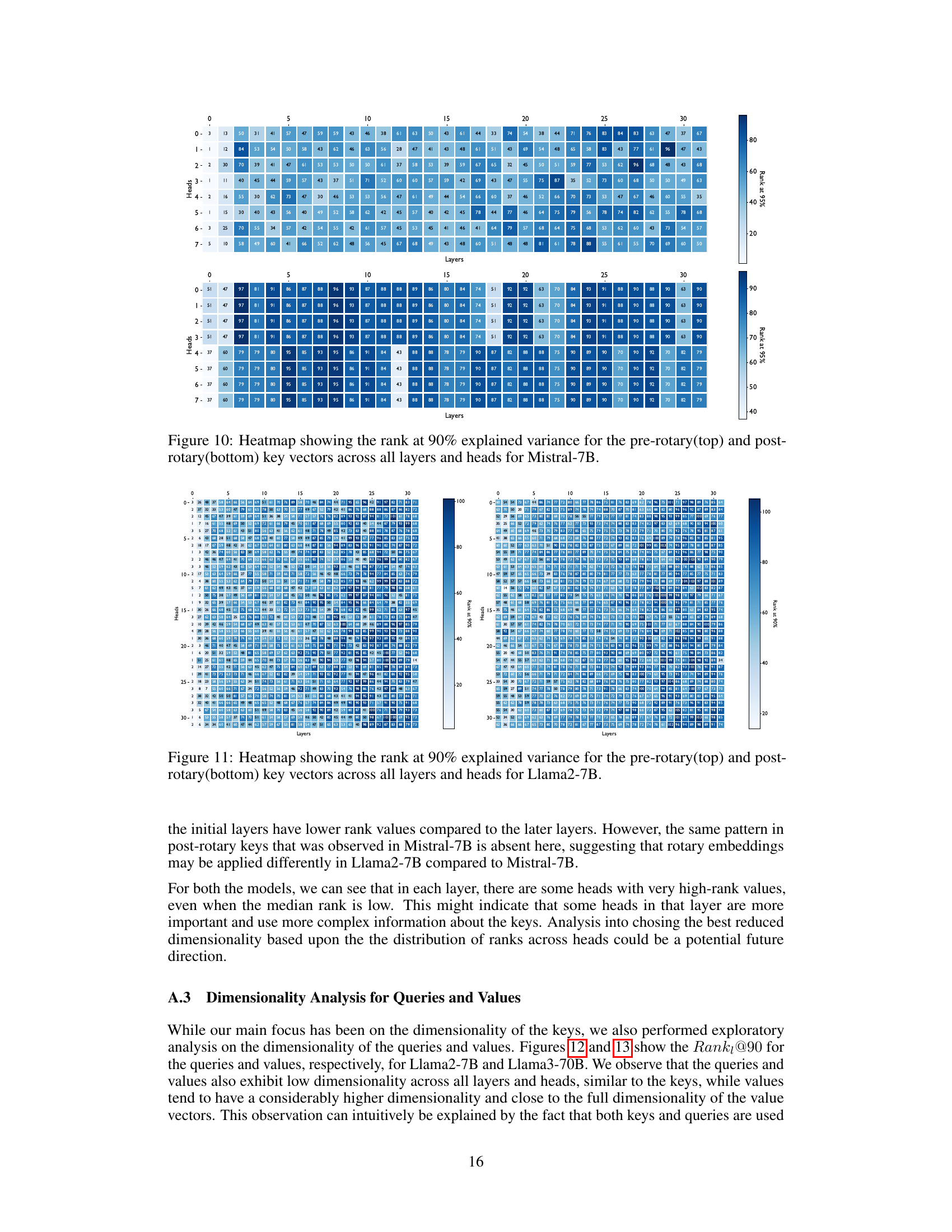

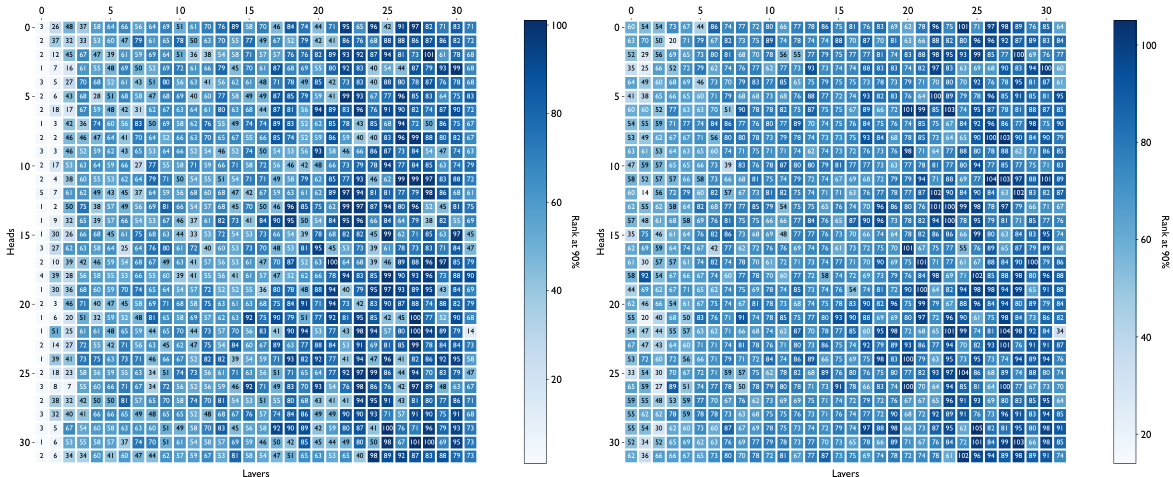

This figure shows the results of a principal component analysis (PCA) on the attention keys from several different large language models (LLMs). For each model, the graph displays how many principal components are needed to capture 90% of the variance in the key vectors, broken down by layer. The x-axis represents the layer number and the y-axis the rank at 90% explained variance. The results indicate that the key vectors across various LLMs consistently occupy a significantly lower-dimensional space than the full attention head dimension, supporting the claim that attention keys lie in a low-dimensional space and that this property is consistent across various datasets and LLMs.

This figure shows two plots. The left plot is a bar chart showing the rank at which 90% of the variance in attention keys is explained for various large language models (LLMs). The x-axis represents the different LLMs considered, and the y-axis represents the rank. A black dashed line indicates the full rank of the keys. The right plot is a schematic diagram illustrating the Loki algorithm proposed in the paper, which uses low-dimensional key vector projections for sparse attention.

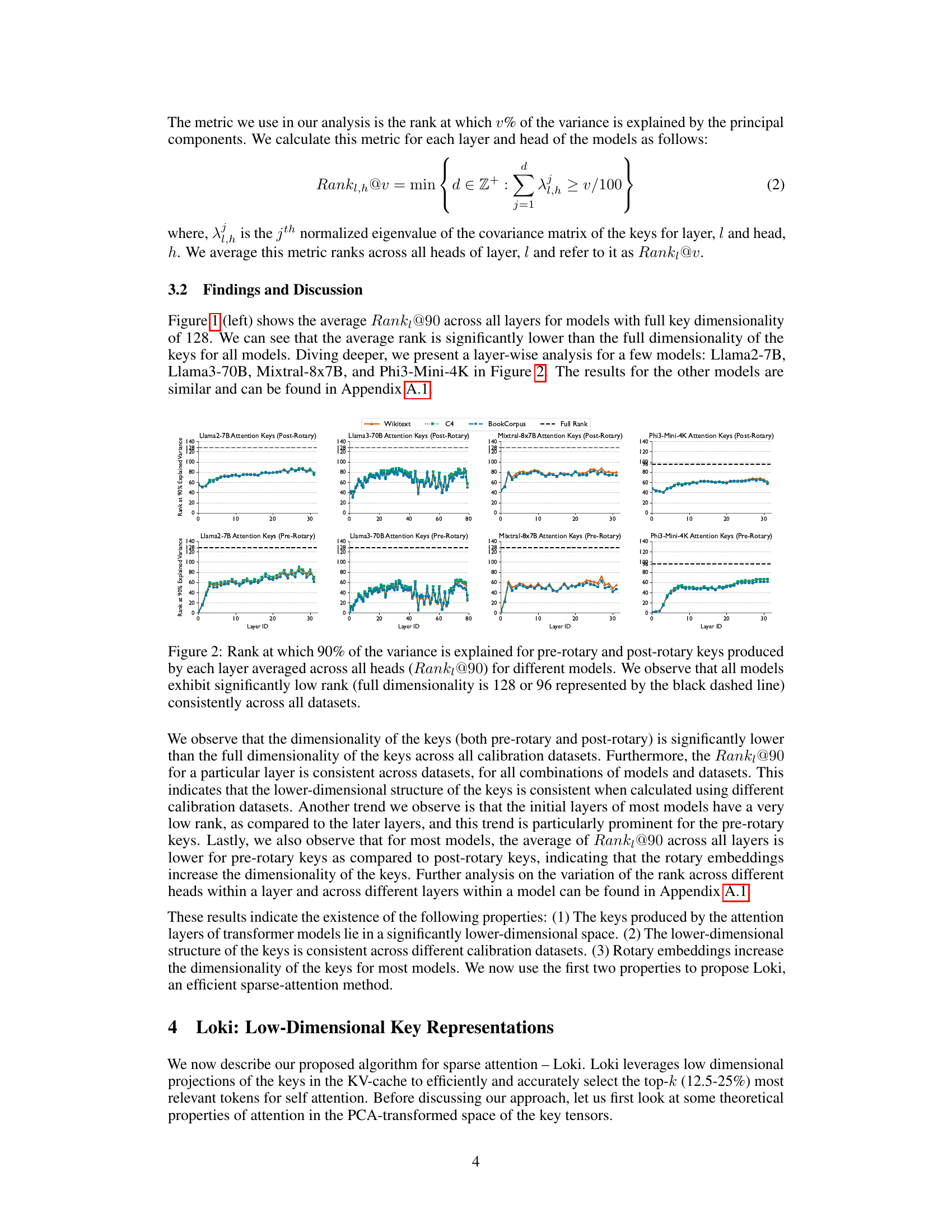

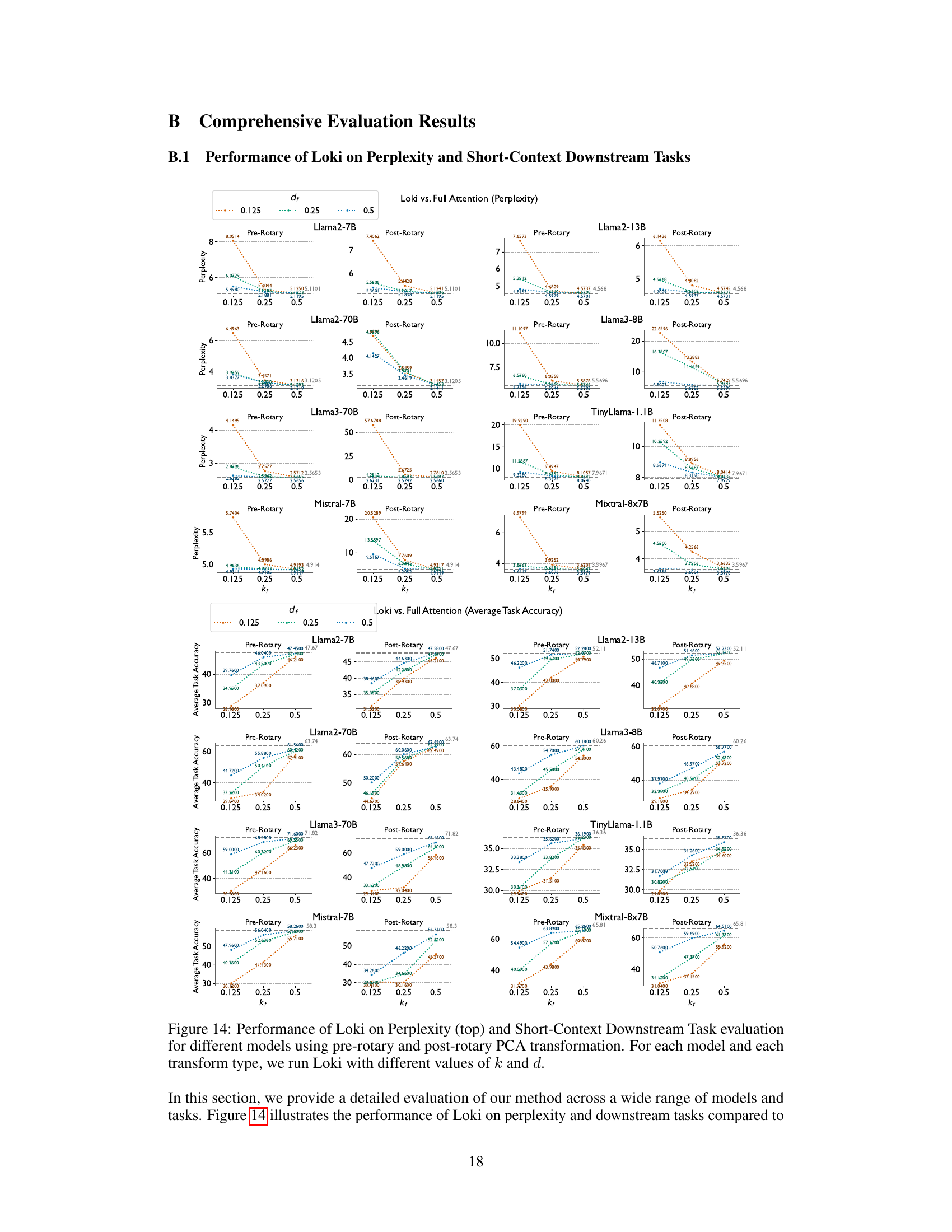

This figure shows the results of evaluating Loki’s performance against a full attention model for various LLMs, focusing on perplexity and short-context downstream tasks. The left plot displays perplexity scores, while the right plot shows average task accuracy across multiple downstream tasks. Different configurations of Loki (using pre-rotary and post-rotary PCA transforms with varying values of k and d) are compared against the full attention model to demonstrate Loki’s efficacy and minimal performance degradation.

This figure displays the results of evaluating Loki’s performance on perplexity and several downstream tasks, comparing it against the performance of a full attention model. The left plot shows perplexity scores across various models (Llama2-7B, Llama2-13B, Llama3-8B, Llama3-70B, Mistral-7B, Mixtral-8x7B) for different configurations of Loki’s hyperparameters (kf and df). The right plot illustrates average task accuracy across the same models and hyperparameter settings. The results indicate Loki’s effectiveness in maintaining model quality and achieving comparable performance to the full attention model, despite using fewer resources. Note that pre- and post-rotary key versions of the models are also compared in the left graph.

The left plot shows the rank (dimensionality) at which 90% of the variance in attention keys is explained for different language models. It demonstrates that a significantly lower dimensionality than the full key vector size captures most of the variance. The right plot provides a schematic overview of the Loki algorithm, illustrating how it uses PCA to reduce the dimensionality of key vectors before computing sparse attention scores and selecting top-k tokens.

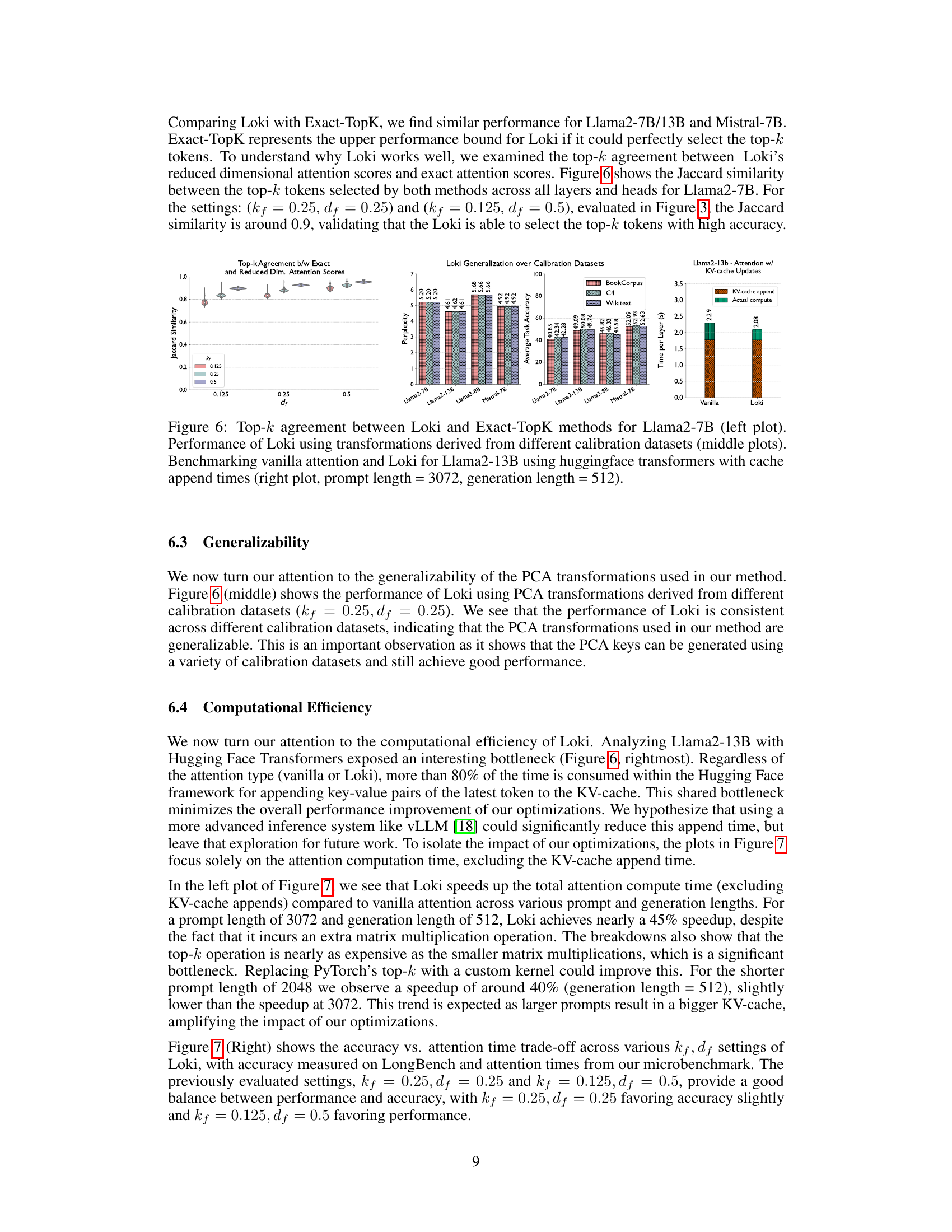

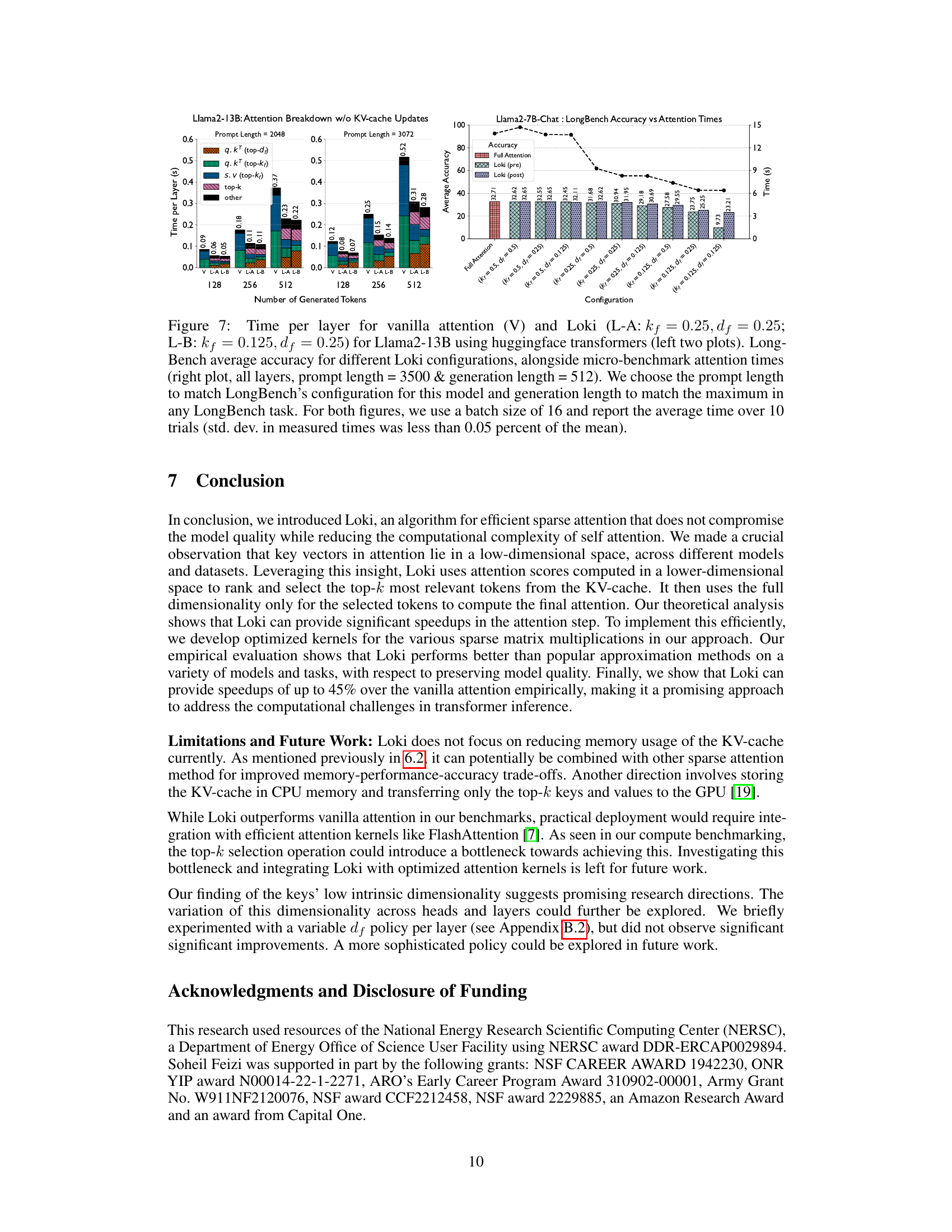

This figure presents a comparison of the computation time per layer for vanilla attention and Loki on Llama2-13B model using HuggingFace transformers. It showcases the breakdown of time spent on various operations within the attention mechanism for both methods at different prompt and generated token lengths. The right plot shows LongBench average accuracy across various Loki configurations, demonstrating the trade-off between accuracy and speed of attention computation. It highlights the impact of different parameter settings (kf and df) on both accuracy and time.

The figure shows two plots. The left plot is a bar chart showing the rank at which 90% of the variance in the attention keys is explained for various large language models (LLMs). The x-axis represents the different LLMs, and the y-axis represents the rank. The right plot is a diagram showing the overall process of the Loki model, including its offline calibration phase and its online token selection process during inference.

The left plot shows the dimensionality of attention keys across different large language models. It demonstrates that a surprisingly small number of principal components (around 80) capture 90% of the variance in the key vectors, even though the full dimensionality is much higher (128). This observation motivates the Loki method. The right plot is a schematic overview of the Loki algorithm: during offline calibration, PCA is applied to the keys to obtain low-dimensional representations; during inference, top-k tokens are selected based on approximate attention scores calculated in this low-dimensional space; the final attention scores are then computed using these top-k tokens in full dimensionality.

The left plot shows the dimensionality of attention keys for various LLMs. It demonstrates that a surprisingly small number of principal components (around 80) can explain 90% of the variance in the key vectors, despite the much higher dimensionality of the full attention heads. This observation forms the basis for the Loki algorithm. The right plot provides a visual overview of Loki’s operational steps: It begins by generating approximate attention scores for all tokens using a lower-dimensional representation (learned offline). Then, it selects top-k most relevant tokens based on these scores and only computes the final attention scores for those selected tokens.

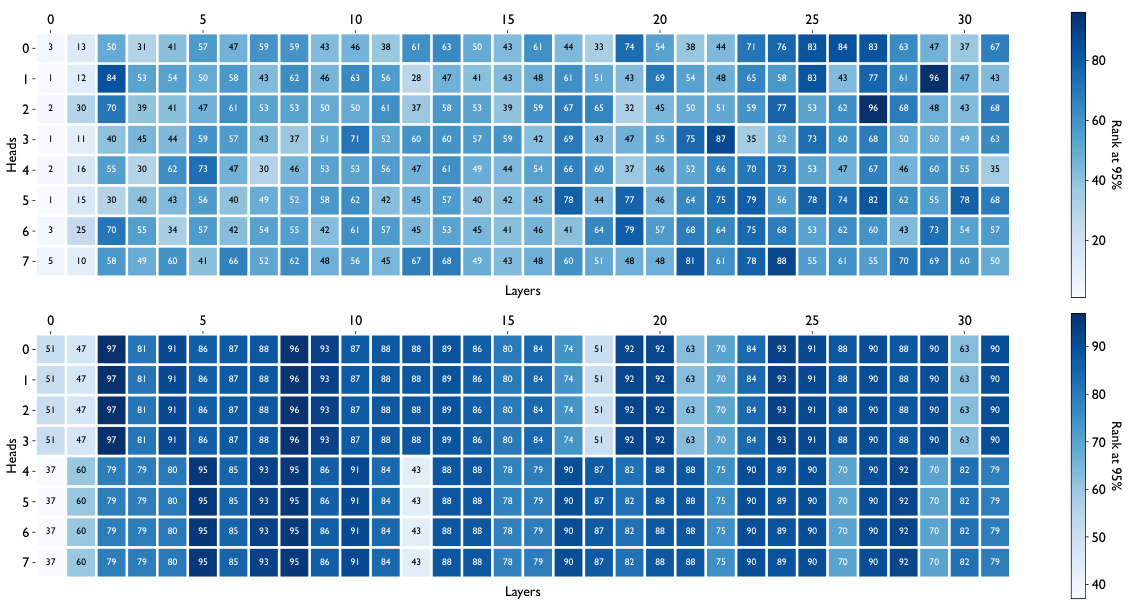

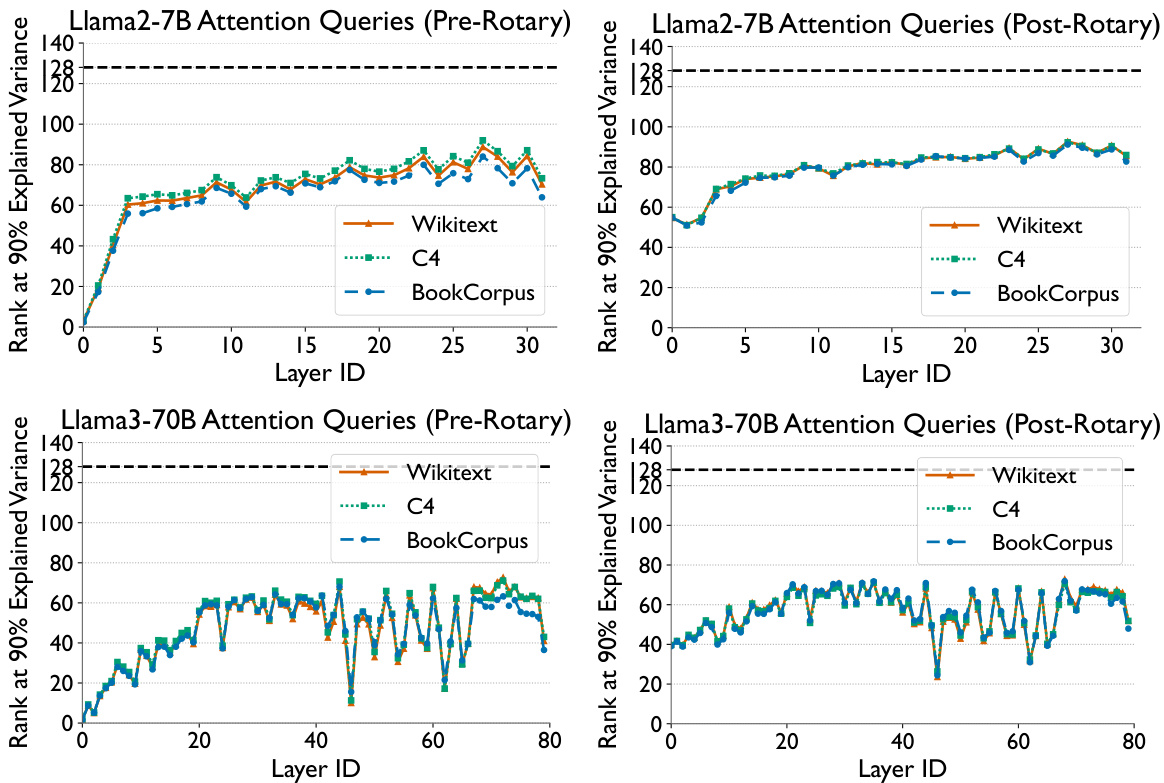

This figure displays the rank at which 90% of the variance is explained for pre-rotary and post-rotary keys across different layers for four different language models. Each model’s data is shown across three datasets: WikiText, C4, and BookCorpus. The results demonstrate that the key vectors consistently occupy a significantly lower dimensional space (around 80) than the full attention head dimension (128 or 96), across various models and datasets. This observation is consistent regardless of whether rotary embeddings are applied to the keys or not. The black dashed line represents the full dimensionality of the keys.

The left plot shows the dimensionality of attention keys across different large language models. The key observation is that a relatively small number of principal components (around 80) capture most of the variance (90%) in the key vectors, despite the larger dimensionality of the attention heads (128). This suggests that key vectors effectively live in a lower-dimensional subspace. The right plot provides a schematic overview of the Loki method. Loki uses PCA on a calibration dataset to identify the most relevant tokens (based on low-dimensional attention scores) and only computes the exact attention scores for the selected tokens. This strategy is expected to improve efficiency and reduce computation costs.

The left plot shows the dimensionality of attention keys across different large language models. It demonstrates that a surprisingly small number of principal components (around 80) explain 90% of the variance in the key vectors, even though the full dimensionality is much higher (128). This observation is key to the Loki method. The right plot provides a schematic overview of the Loki algorithm: using a calibration dataset, PCA is performed on the key tensors offline to generate approximate attention scores, and these scores are used to select only the most relevant tokens from the KV-cache, speeding up inference without substantial accuracy loss. For these selected tokens, the full dimensional key vectors are used to compute the final attention scores.

The left plot shows the rank (dimensionality) at which 90% of the variance in key vectors is explained, averaged across all layers and heads for various LLMs. The full rank (dimensionality of the key vector) is shown as a black dashed line for reference. The plot shows that a significantly lower-rank representation captures almost all the information in the key vectors, demonstrating their intrinsic low-dimensionality. The right plot provides a schematic overview of the Loki method. Loki leverages this low dimensionality to achieve computational efficiency.

This figure shows the low dimensionality of attention keys across various large language models. The left panel displays a bar chart, with error bars, illustrating the rank at which 90% of the variance in attention keys is explained for each model. The results demonstrate that a relatively low rank captures most of the variance, indicating a low-dimensional structure. The right panel provides a schematic overview of the Loki algorithm, summarizing the steps involved in dimensionality reduction, token selection, and final attention computation.

The left plot shows the dimensionality of attention keys across different large language models. It demonstrates that a surprisingly small number of principal components (around 80) are sufficient to capture 90% of the variance in the key vectors, even though the full dimensionality of the keys is much larger (128). This observation motivates the Loki method. The right plot provides a schematic overview of the Loki algorithm, highlighting the key steps: offline PCA on keys from a calibration dataset, online selection of top-k tokens using low-rank attention scores, and the final full-rank attention computation on the selected tokens.

The figure on the left shows the dimensionality of attention keys across different LLMs. It plots the rank at which 90% of the variance in the key vectors is explained by principal component analysis (PCA), averaged across all layers and heads within each model. The black dashed line indicates the full dimensionality of the key vectors, showing that a significantly lower dimensionality captures most of the variance. The figure on the right shows an overview of the Loki algorithm, illustrating the process of offline calibration using PCA, online token selection based on low-dimensional attention scores, and the computation of final attention scores using the full dimensionality for the selected tokens.

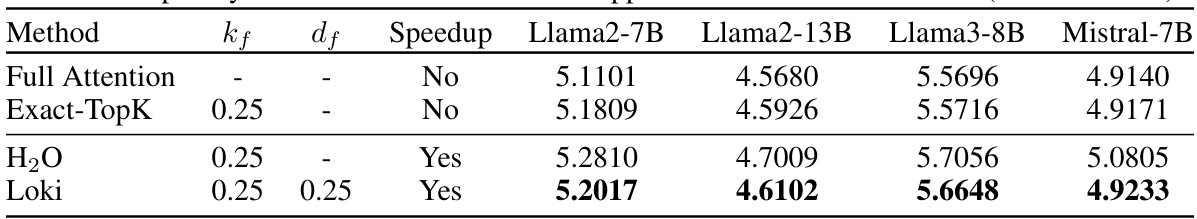

More on tables

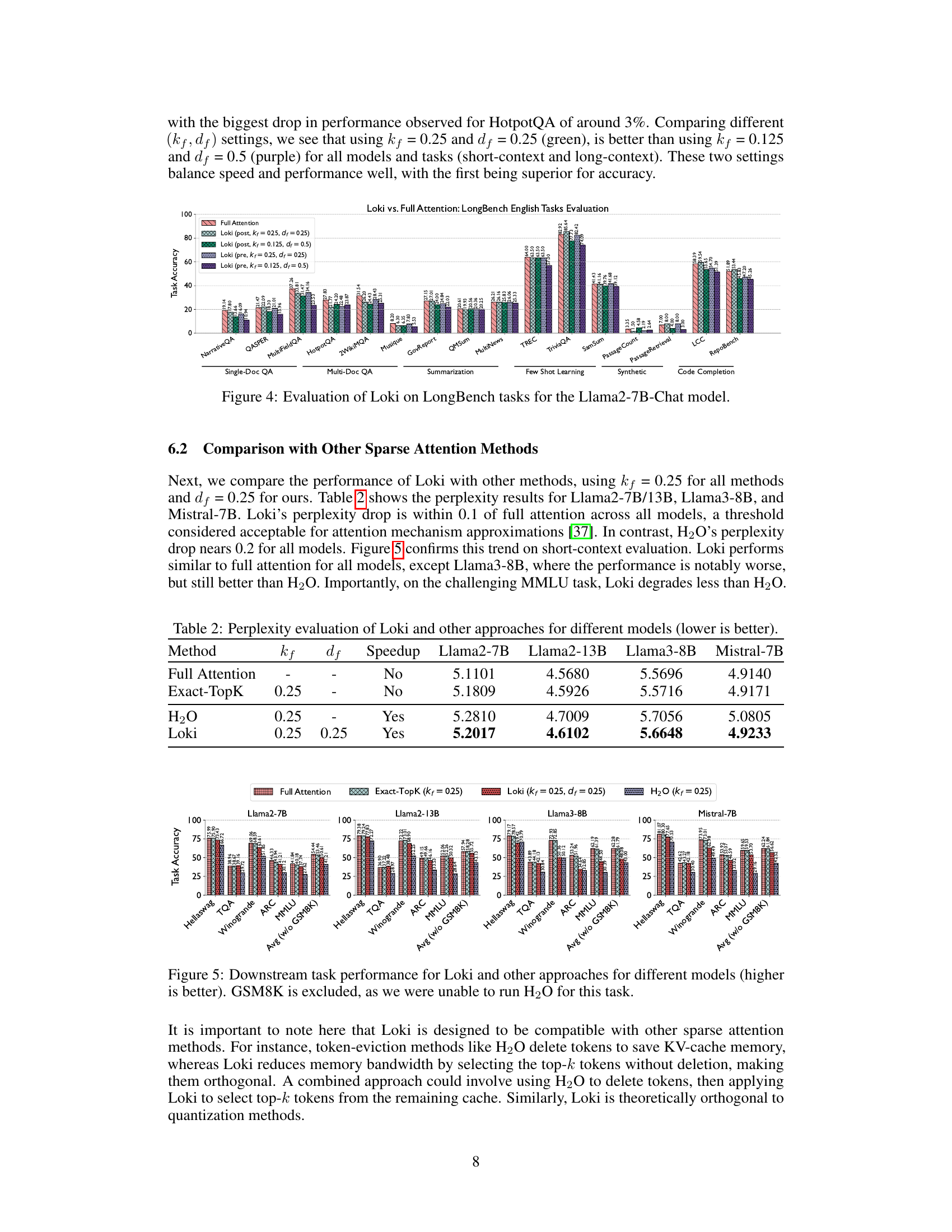

This table compares the perplexity scores achieved by four different methods: Full Attention (baseline), Exact-TopK (a sparse attention method), H2O (another sparse attention method), and Loki (the proposed method). The perplexity is a measure of how well the model predicts a sequence of tokens. Lower perplexity indicates better performance. The table shows the perplexity for four different large language models (LLMs): Llama2-7B, Llama2-13B, Llama3-8B, and Mistral-7B. The ‘kf’ column indicates the fraction of keys kept in the key-value cache for the sparse attention methods. The ‘df’ column shows the fraction of the full dimensionality used for the keys in the Loki method. The ‘Speedup’ column indicates whether the method uses speedup techniques. The results demonstrate the relative performance of Loki compared to other sparse attention techniques, showing that Loki achieves comparable performance to the baseline method while incorporating speedup techniques.

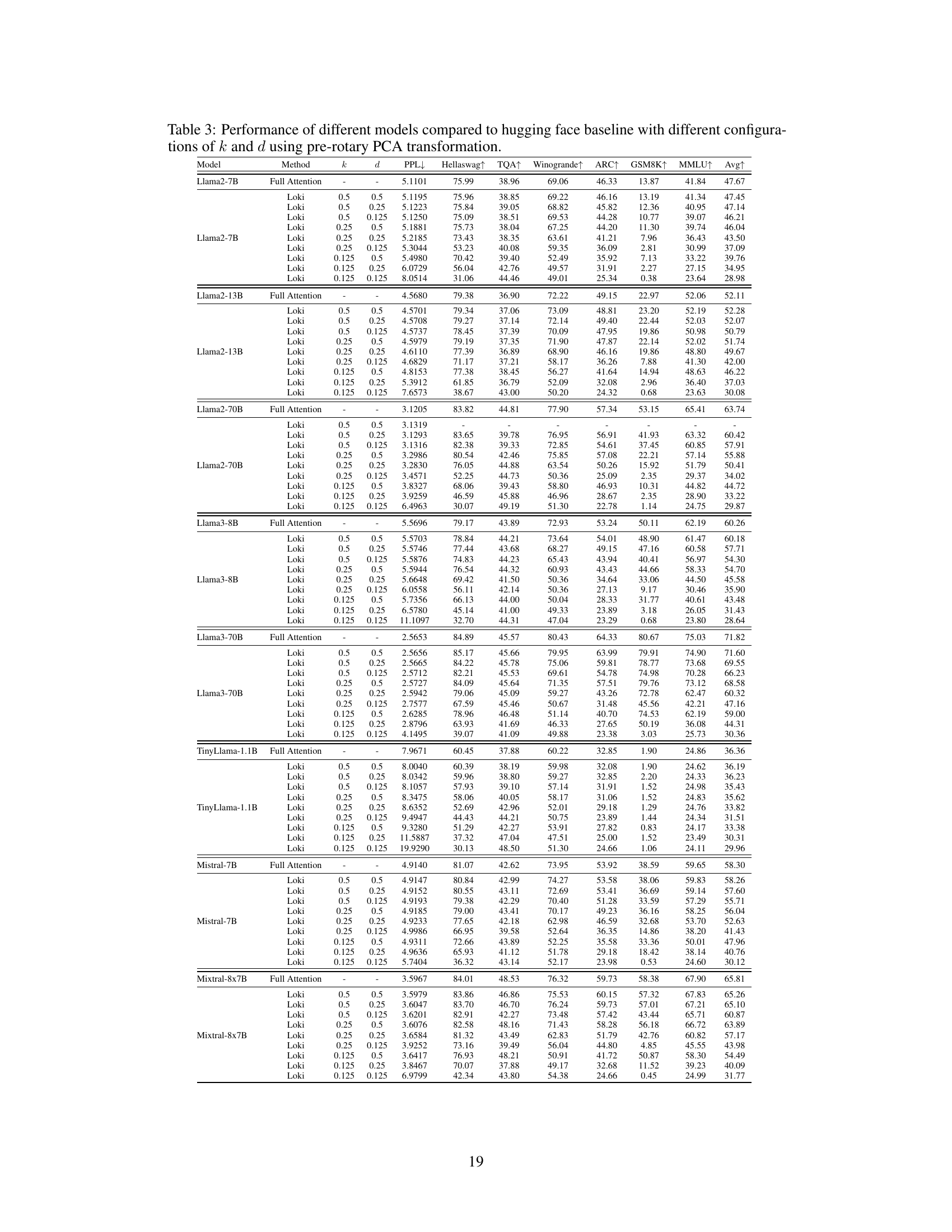

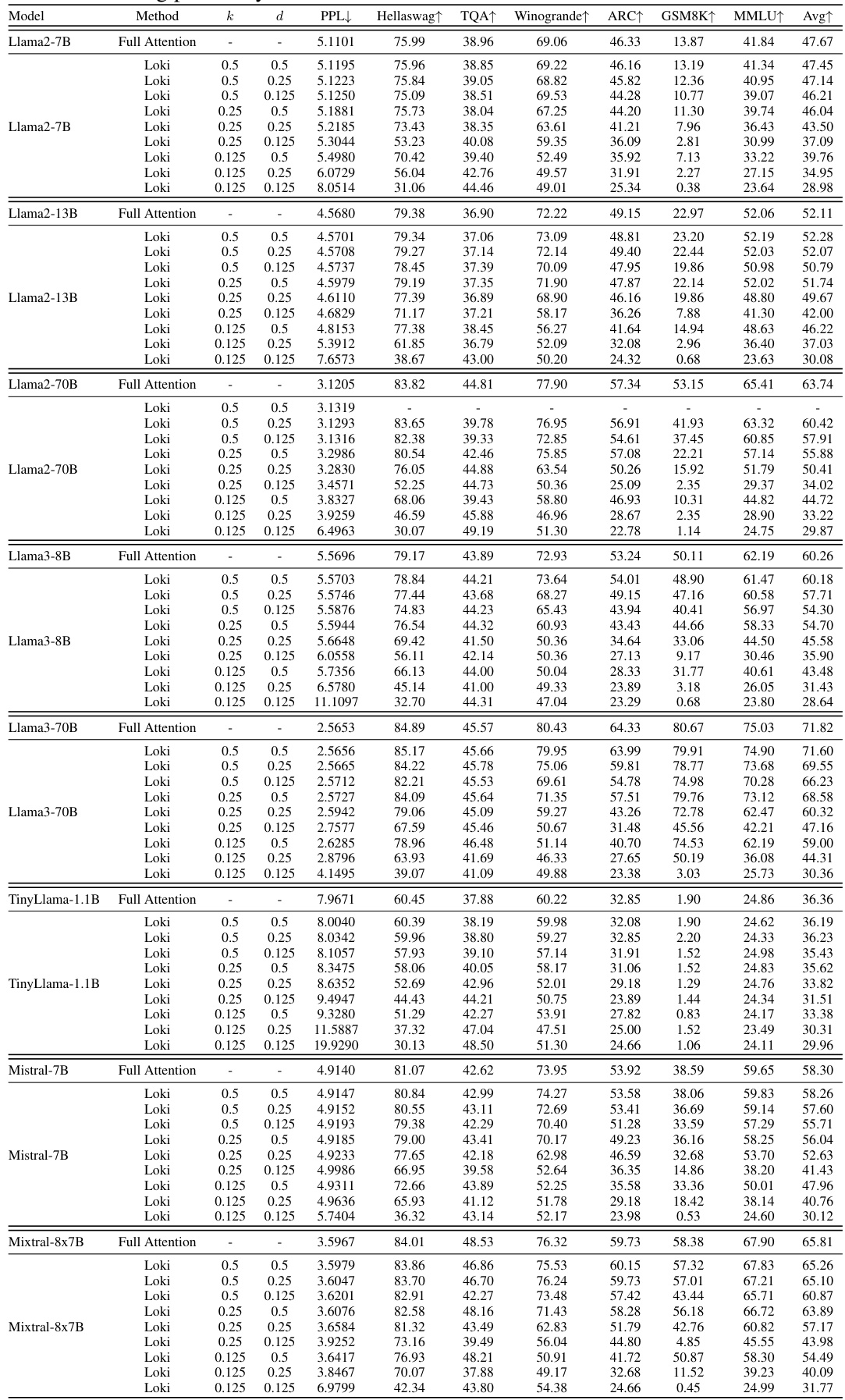

This table presents the performance comparison of various LLMs (Llama2-7B, Llama2-13B, Llama2-70B, Llama3-8B, Llama3-70B, TinyLlama-1.1B, Mistral-7B, Mixtral-8x7B) using different configurations of the Loki model against the Hugging Face baseline. The metrics include perplexity (PPL), Hellaswag, TQA, Winogrande, ARC, GSM8K, and MMLU. Different values of k (fraction of keys selected) and d (reduced dimensionality) are explored to analyze their impact on performance.

This table compares the performance of several large language models (LLMs) using the Loki method with different settings of hyperparameters (k and d) against the Hugging Face baseline. The models are evaluated on a range of downstream tasks, including perplexity, Hellaswag, TQA, Winogrande, ARC, GSM8K, and MMLU. The table shows the performance differences for various combinations of the hyperparameters, allowing for an analysis of how these parameter choices affect model performance across multiple evaluation metrics.

This table presents the performance of the PCAAttn method (a variant of Loki that directly uses reduced-dimensional attention scores) compared to full attention, Exact TopK, and H2O on two different models (Llama2-7B and Mistral-7B) using different cache configurations (kf=0.5, kf=0.25). The metrics used are Perplexity and several downstream task accuracies (Hellaswag, Winogrande, MathQA, OpenbookQA, RTE, COPA). The results showcase the poor performance of PCAAttn compared to the baselines, suggesting that the dimensionality reduction approach used in this method is not effective in the presence of rotary embeddings.

Full paper#