↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep learning models often suffer from overfitting, where they memorize training data instead of learning generalizable patterns. Traditional weight decay, a common regularization technique, uniformly penalizes model parameters to combat overfitting but can be too restrictive or insufficient for individual parameters. This paper identifies this as a key problem limiting the performance of deep learning models.

The authors introduce a novel regularization method called Constrained Parameter Regularization (CPR) that addresses this issue. Instead of uniform penalization, CPR dynamically adjusts the regularization strength for each parameter based on its statistical measure (like L2-norm), ensuring neither over nor under-regularization. Experiments across various deep learning tasks (image classification, language modelling, and medical image segmentation) demonstrated that CPR outperforms traditional weight decay, improving both pre-training and fine-tuning performance. Moreover, CPR achieves this with minimal hyperparameter tuning, showcasing its practicality and efficiency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers as it introduces Constrained Parameter Regularization (CPR), a novel method that significantly improves deep learning optimization. CPR addresses limitations of traditional weight decay by dynamically adapting regularization, leading to enhanced model generalization and performance gains across various tasks. This opens up new avenues for research in regularization techniques and offers a hyperparameter-efficient alternative to current approaches. The results are impactful and relevant to current research trends in deep learning, showing significant performance improvements, especially in pre-training and fine-tuning scenarios.

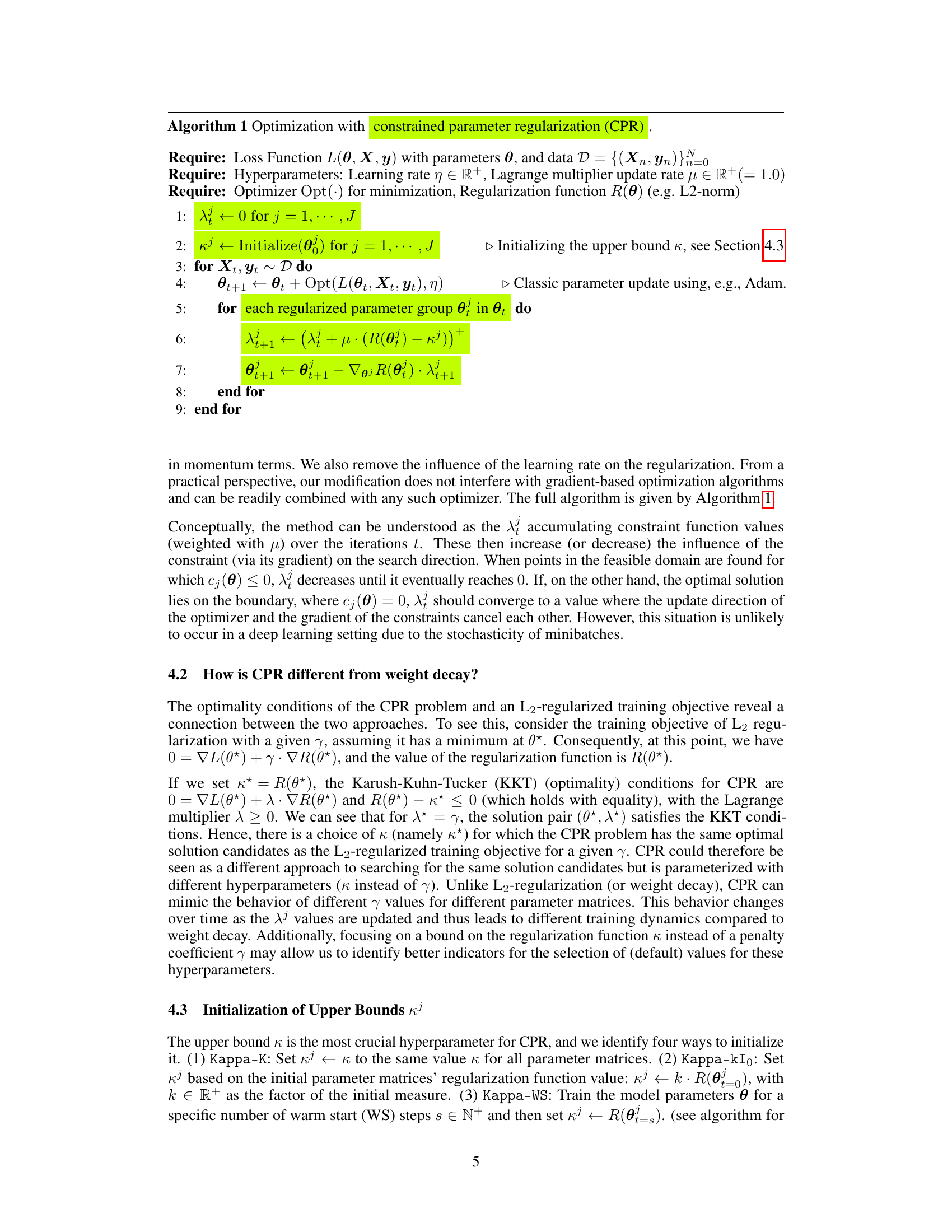

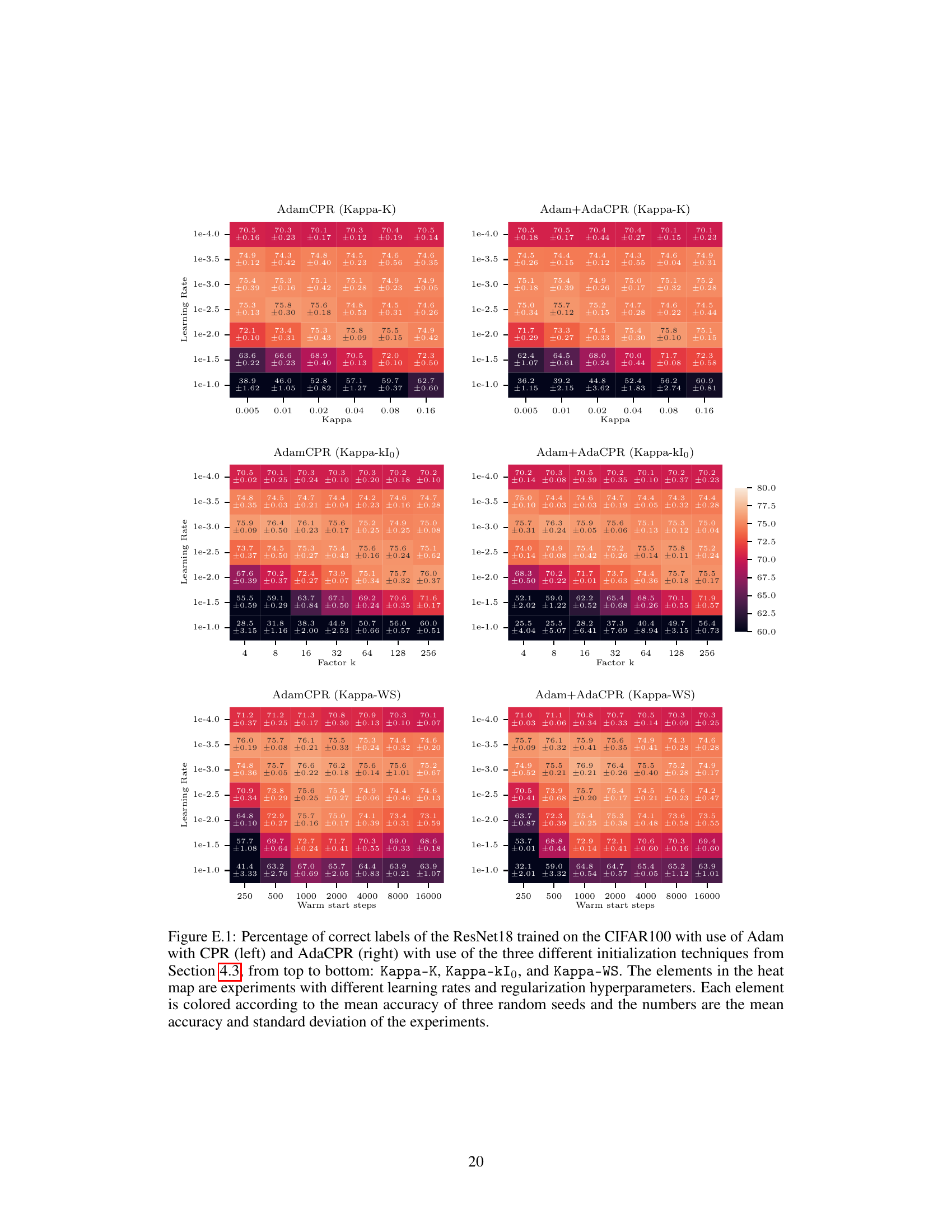

Visual Insights#

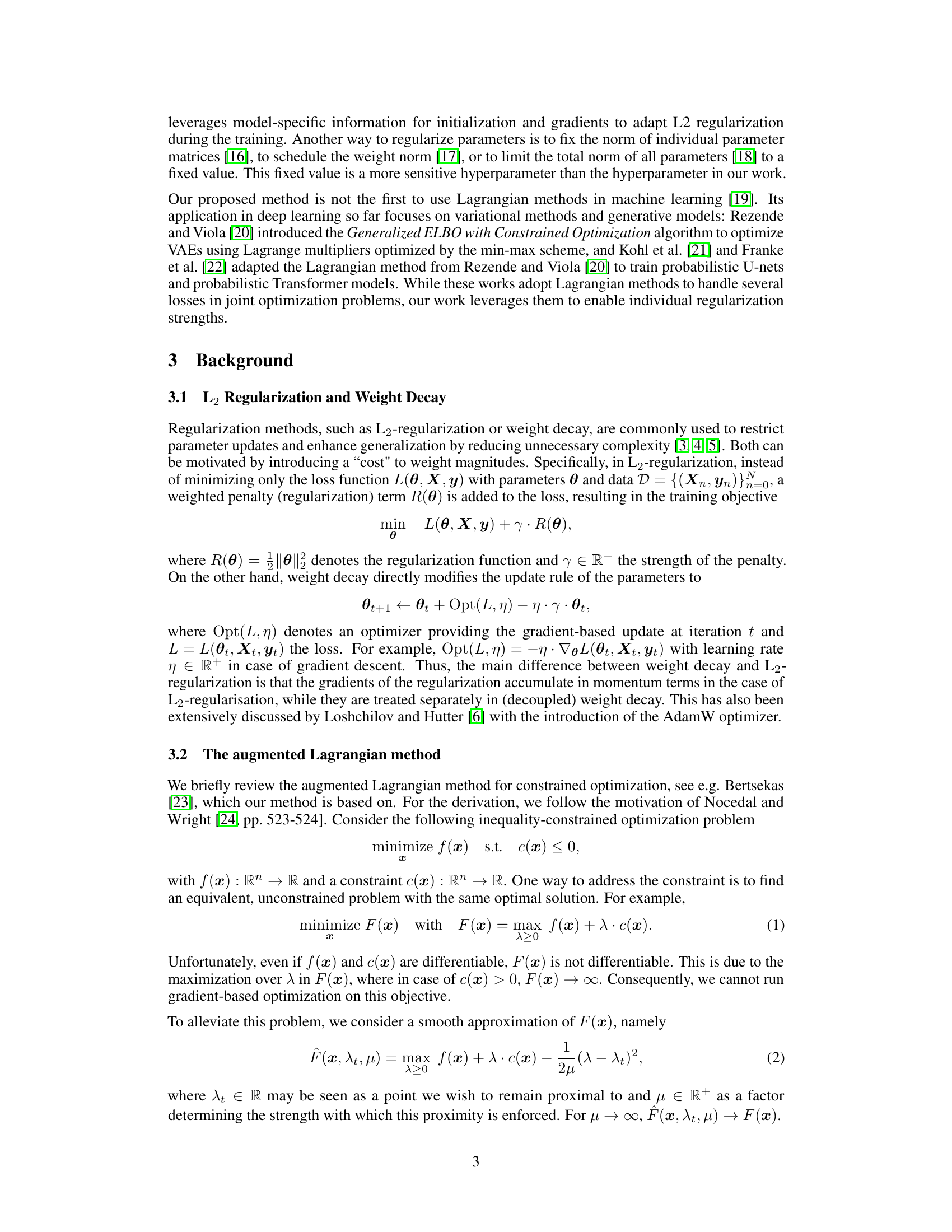

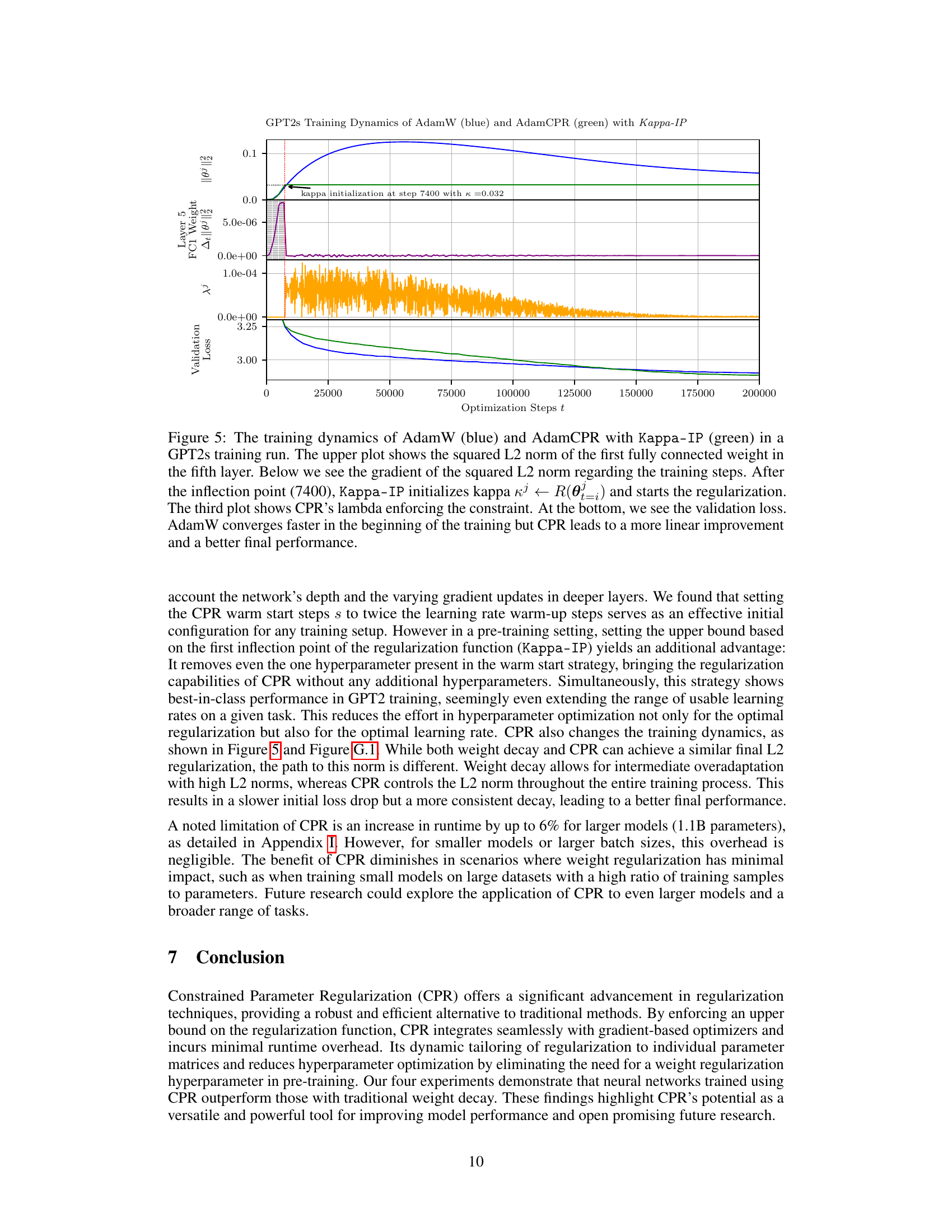

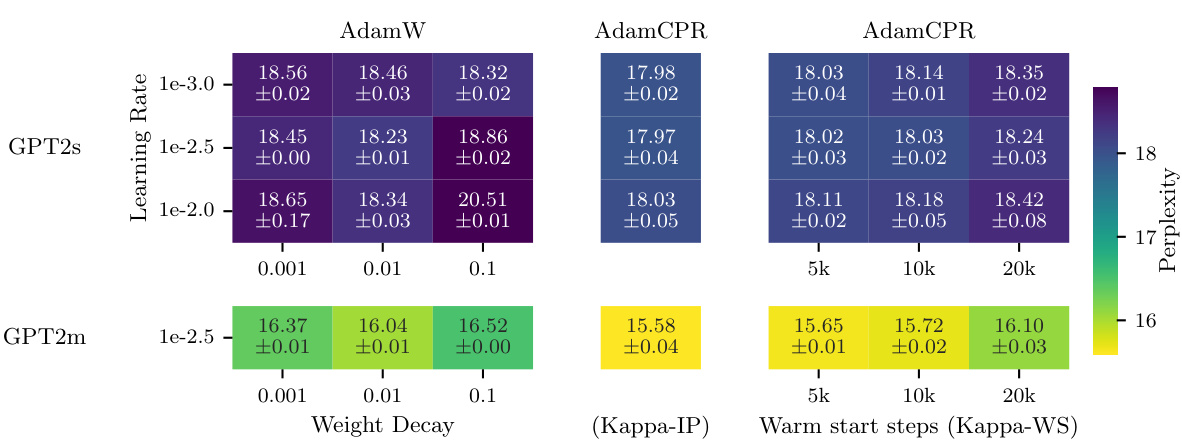

This figure shows the perplexity of a GPT-2 small language model during training using two different optimization methods: AdamW (with weight decay) and AdamCPR (with the Kappa-IP constraint initialization). The plot demonstrates that AdamCPR achieves a lower perplexity (better performance) than AdamW within the same number of optimization steps (training budget). Furthermore, it highlights that AdamCPR reaches the same perplexity level as AdamW trained for 300k steps, but using only 200k steps. This demonstrates the efficiency of the AdamCPR optimization method.

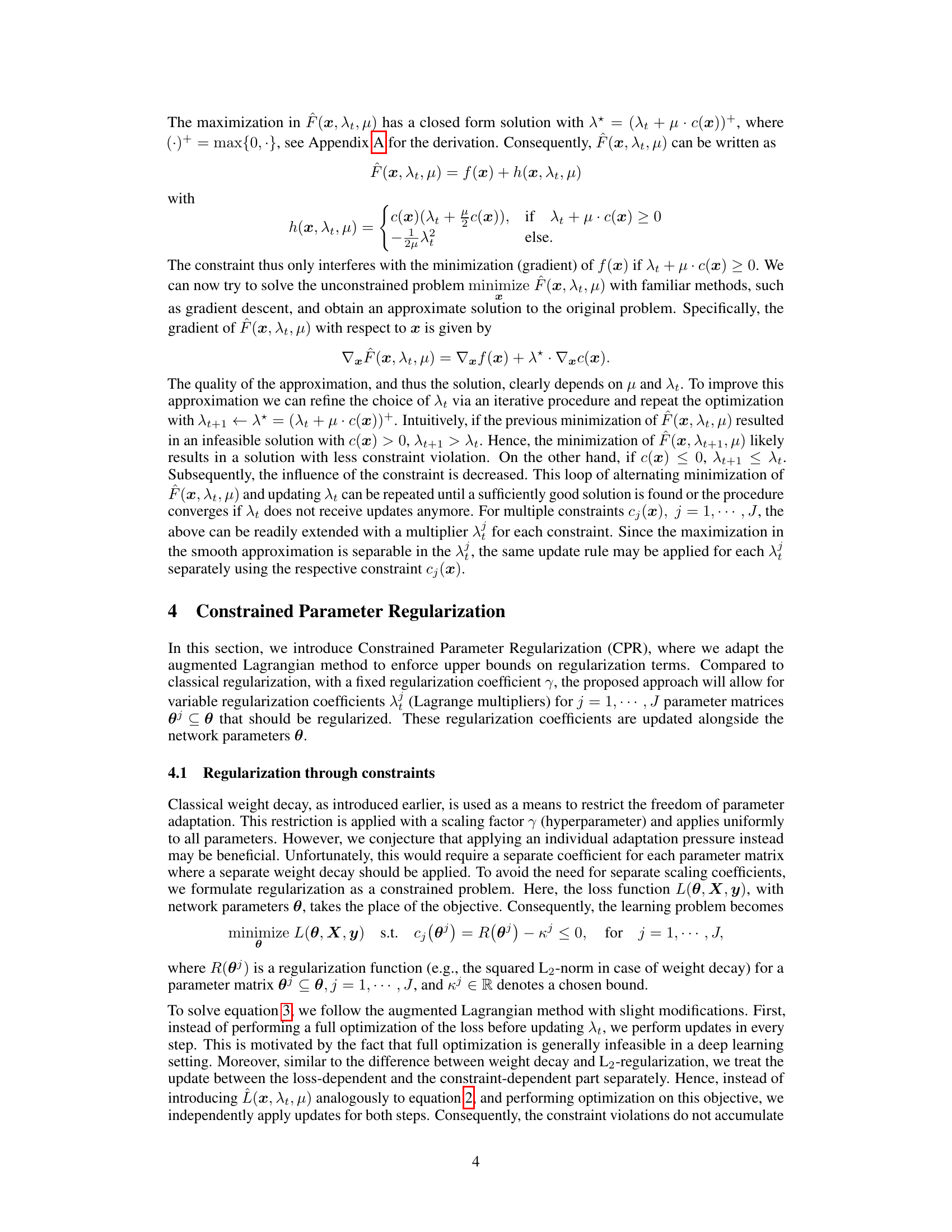

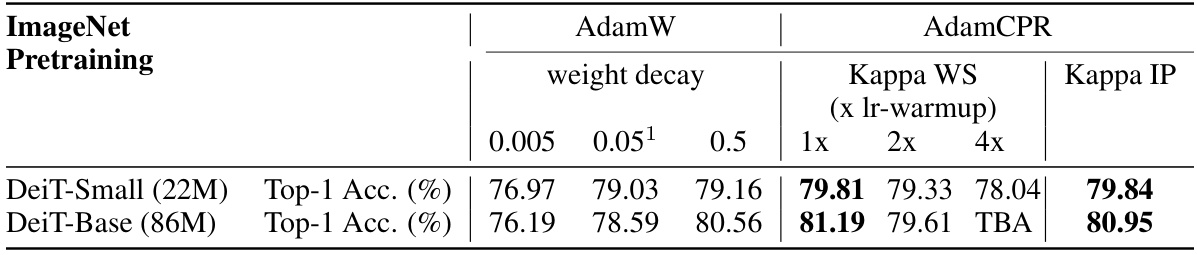

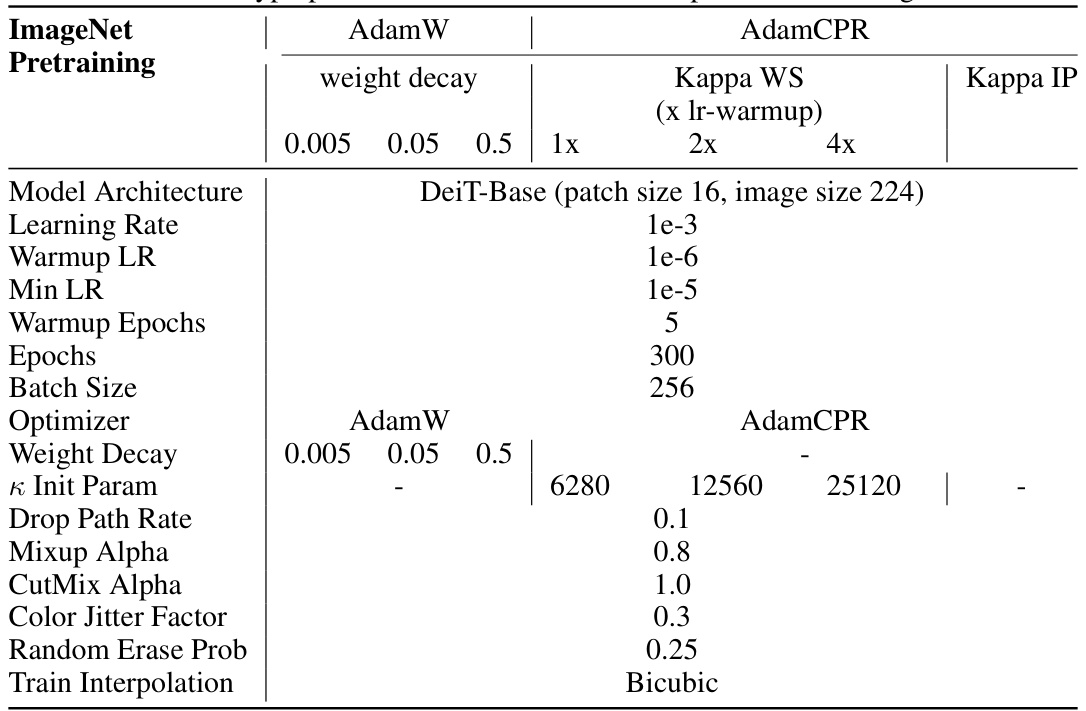

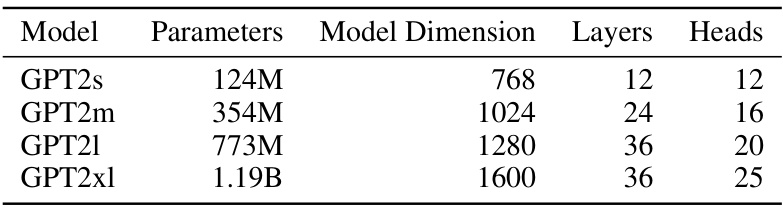

This table compares the performance of AdamW and AdamCPR on DeiT-Small (22M parameters) and DeiT-Base (86M parameters) models trained on the ImageNet dataset. It shows the Top-1 Accuracy achieved using AdamW with different weight decay values (0.005, 0.05, 0.5) and AdamCPR with Kappa WS initialization (1x, 2x, 4x lr-warmup) and Kappa IP initialization. The results highlight the impact of different regularization strategies on model accuracy in pre-training.

In-depth insights#

CPR: A New Regularizer#

Constrained Parameter Regularization (CPR) is presented as a novel regularization technique that dynamically adjusts penalty strengths for individual parameter matrices, unlike traditional weight decay’s uniform approach. CPR enforces upper bounds on statistical measures (like L2-norm) of these matrices, transforming the problem into a constrained optimization one. This is effectively solved via an augmented Lagrangian method, adapting regularization strengths automatically. The method is computationally efficient, only slightly impacting runtime, and requires minimal hyperparameter tuning. Empirical evaluations across diverse tasks (computer vision, language modeling, and medical image segmentation) demonstrate CPR’s consistent performance improvements over standard weight decay, showcasing its effectiveness in both pre-training and fine-tuning scenarios. CPR’s adaptive nature, driven by the augmented Lagrangian approach, allows for customized regularization based on parameter behavior and task specifics, potentially offering a more flexible and effective alternative to traditional weight decay techniques.

Augmented Lagrangian#

The Augmented Lagrangian method is a powerful technique for solving constrained optimization problems. It addresses the limitations of standard Lagrangian methods by adding a penalty term to the Lagrangian function, effectively transforming a constrained problem into an unconstrained one. This penalty term, parameterized by a coefficient (μ), increases as the constraint violation grows, encouraging convergence towards feasibility. The method iteratively updates the primal variables (the model’s parameters in this context) and the dual variables (Lagrange multipliers), gradually adjusting the penalty and improving both feasibility and optimality. The choice of the penalty coefficient (μ) is crucial, influencing convergence speed and stability. A carefully selected update rule for the Lagrange multipliers ensures a smooth and effective approach. In the context of the research paper, this method is cleverly adapted to enforce individual parameter constraints in deep learning, effectively allowing the model to learn with customized regularization strengths for each parameter matrix, rather than a universally applied penalty as is common with weight decay.

ImageNet & Beyond#

The heading ‘ImageNet & Beyond’ suggests an exploration of advancements in computer vision that move beyond the limitations of ImageNet, a benchmark dataset known for its impact on the field. The authors likely discuss how models trained on ImageNet, while achieving impressive performance, often fail to generalize well to real-world scenarios because of biases and limitations inherent in the dataset. Beyond ImageNet, the discussion could cover the use of larger, more diverse datasets, addressing issues such as class imbalance, domain adaptation, and robustness to noise. It could also delve into innovative training methodologies, exploring self-supervised learning, transfer learning, and the development of more generalizable architectures. Furthermore, ethical considerations related to bias and representation within the datasets are likely addressed, emphasizing the importance of fair and responsible AI development. The section will likely showcase empirical results and comparison of performance using more sophisticated techniques than those solely reliant on ImageNet.

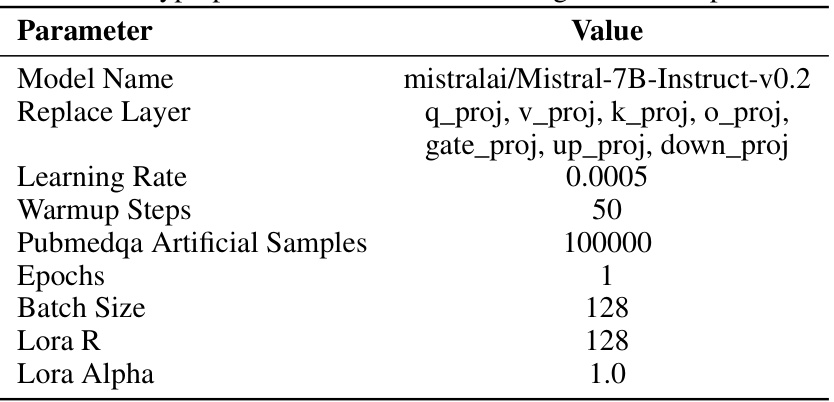

LLM Fine-tuning#

The section on “LLM Fine-tuning” would likely explore adapting large language models (LLMs) for specialized tasks. This involves fine-grained control over the model’s parameters, often focusing on specific layers or components to avoid catastrophic forgetting. The authors would likely discuss different fine-tuning strategies, comparing their effectiveness and efficiency. Key considerations might include the size of the pre-trained LLM, the amount of task-specific data available, and the computational resources required. Performance metrics would center around the model’s accuracy, efficiency, and robustness on the target task. Successful fine-tuning is crucial for deploying LLMs effectively, as it allows tailoring their impressive capabilities to specific needs, enabling them to excel in narrow domains where massive pre-training alone might prove insufficient. Transfer learning principles would likely be highlighted, emphasizing the ability to transfer knowledge from the general LLM to a specific application.

Limitations of CPR#

While Constrained Parameter Regularization (CPR) offers advantages over traditional weight decay, it also presents limitations. Computational overhead, although minor, may still impact training time, especially on large models. Hyperparameter sensitivity remains an issue; although CPR significantly reduces the need for hyperparameter tuning compared to traditional approaches, the upper bound (κ) still requires careful initialization. The optimal initialization strategy might depend on the specific task and model architecture, thus requiring some experimentation. Theoretical guarantees for CPR’s performance remain limited, relying heavily on empirical results. Finally, the generalizability of CPR’s performance across various network architectures and tasks requires further investigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

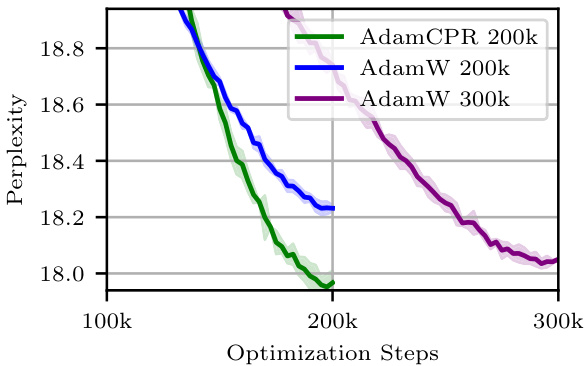

This figure compares the performance of three different optimization methods: AdamW with weight decay, AdamCPR with Kappa-IP, and AdamW with a larger training budget. The y-axis represents perplexity (a measure of how well the model predicts the next token in a sequence), and the x-axis shows the number of optimization steps. The plot demonstrates that AdamCPR (using the Constrained Parameter Regularization method with Kappa-IP initialization) achieves a lower perplexity than AdamW with the same training budget, and reaches a similar perplexity score as AdamW with a larger budget using only two-thirds of the steps. This highlights the efficiency and effectiveness of the AdamCPR method.

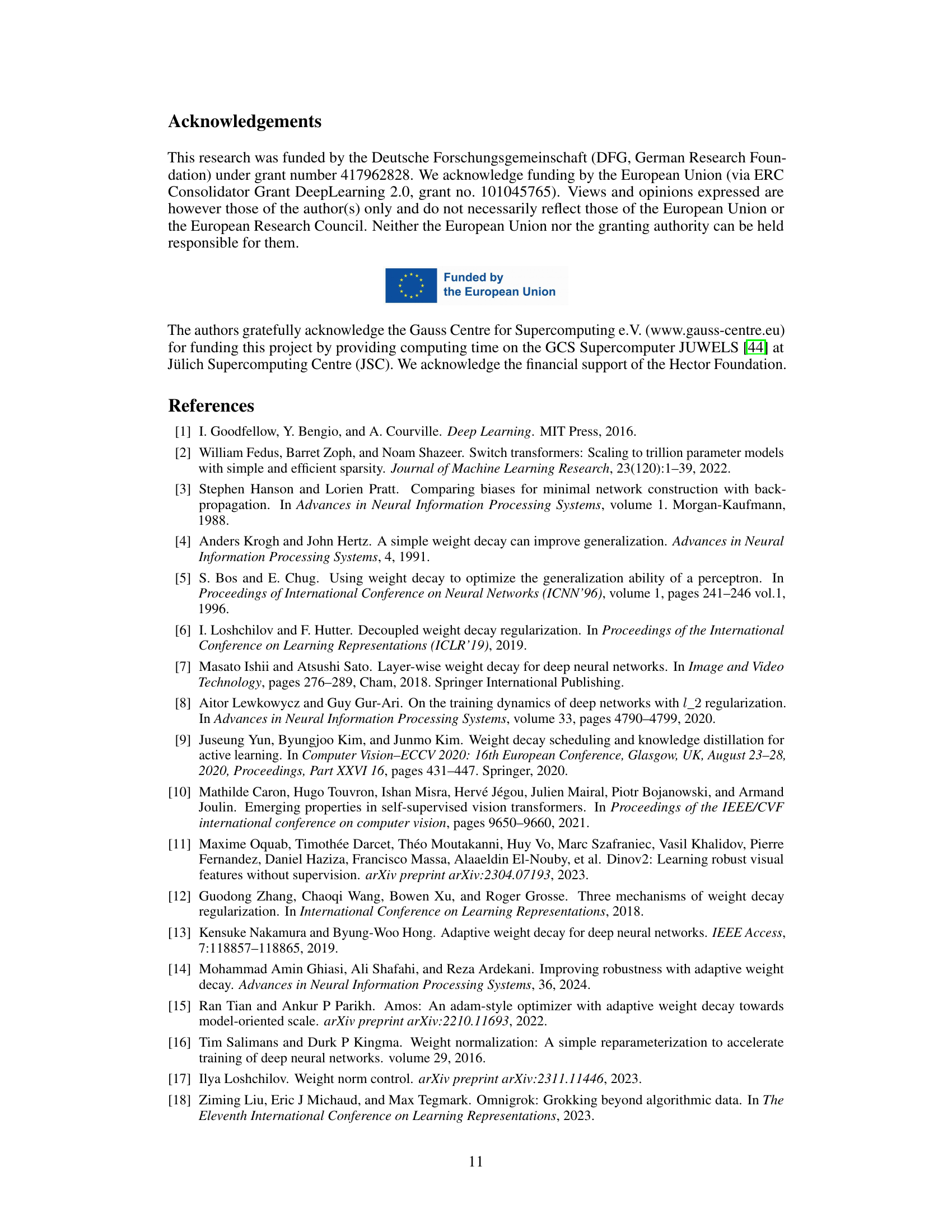

This figure shows the training curves of a GPT-2 small language model trained using the Adam optimizer with either weight decay (AdamW) or the proposed Constrained Parameter Regularization (CPR) method. The x-axis represents the number of optimization steps, and the y-axis represents the perplexity, a measure of the model’s performance. The figure demonstrates that AdamCPR with Kappa-IP initialization achieves the same perplexity as AdamW but with fewer optimization steps (approximately 2/3 of the steps). This illustrates CPR’s efficiency in achieving comparable results with reduced computational cost.

The figure shows the perplexity (a measure of how well a language model predicts a sequence of words) over the course of training a GPT-2 small language model. Two different optimization methods are compared: AdamW (a widely used optimizer with weight decay) and AdamCPR (the proposed method with constrained parameter regularization). AdamCPR consistently achieves lower perplexity than AdamW, indicating better model performance. Notably, AdamCPR reaches a similar perplexity to AdamW with fewer optimization steps, highlighting its efficiency.

This figure shows the perplexity of a GPT2s language model trained using two different optimizers: AdamW (with weight decay) and AdamCPR (with Kappa-IP constraint initialization). The x-axis represents the number of optimization steps, and the y-axis represents the perplexity (a lower perplexity indicates better performance). AdamCPR achieves a lower perplexity than AdamW using the same number of optimization steps. Furthermore, AdamCPR reaches a similar level of perplexity as AdamW using approximately 2/3 of the optimization steps, demonstrating its efficiency.

The figure shows the perplexity (a measure of how well a language model predicts a sequence of words) over the number of optimization steps during the training of a GPT-2 small language model. Two different optimization methods are compared: AdamW (a popular optimizer with weight decay) and AdamCPR (the proposed method using constrained parameter regularization). AdamCPR (using the Kappa-IP initialization strategy) achieves a lower perplexity than AdamW, indicating better performance, and reaches the same perplexity with fewer optimization steps (approximately 2/3 the number of steps). This demonstrates the efficiency of AdamCPR in achieving the same level of performance with reduced computational cost.

This figure shows the perplexity (a measure of how well a language model predicts text) over the course of training a GPT-2 small (GPT2s) language model. Two optimization methods are compared: AdamW (a popular optimizer with weight decay) and AdamCPR (the proposed method using constrained parameter regularization). The results demonstrate that AdamCPR achieves a lower perplexity (better performance) than AdamW with the same training budget (optimization steps). Furthermore, AdamCPR reaches the same perplexity as AdamW using only two-thirds of the training steps, indicating improved efficiency.

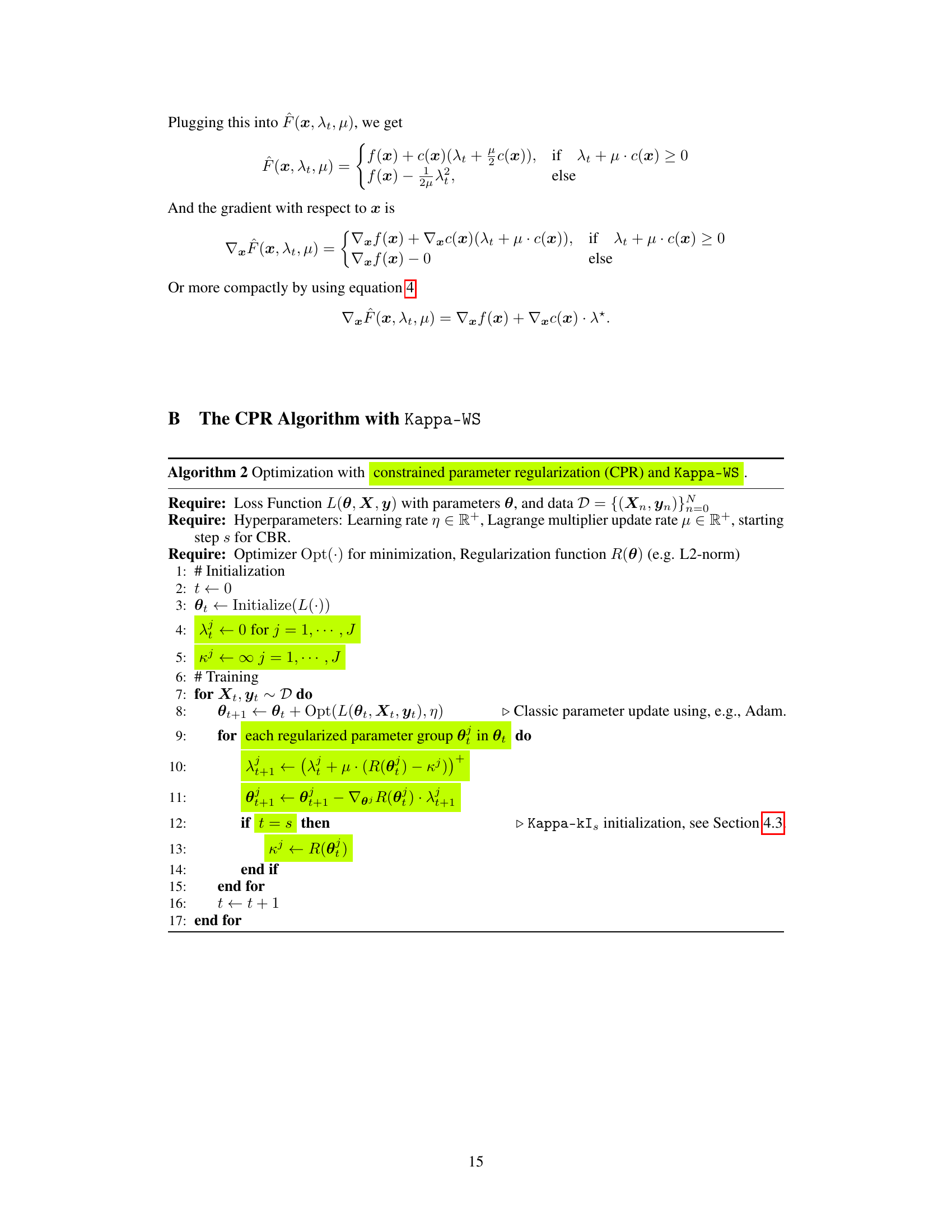

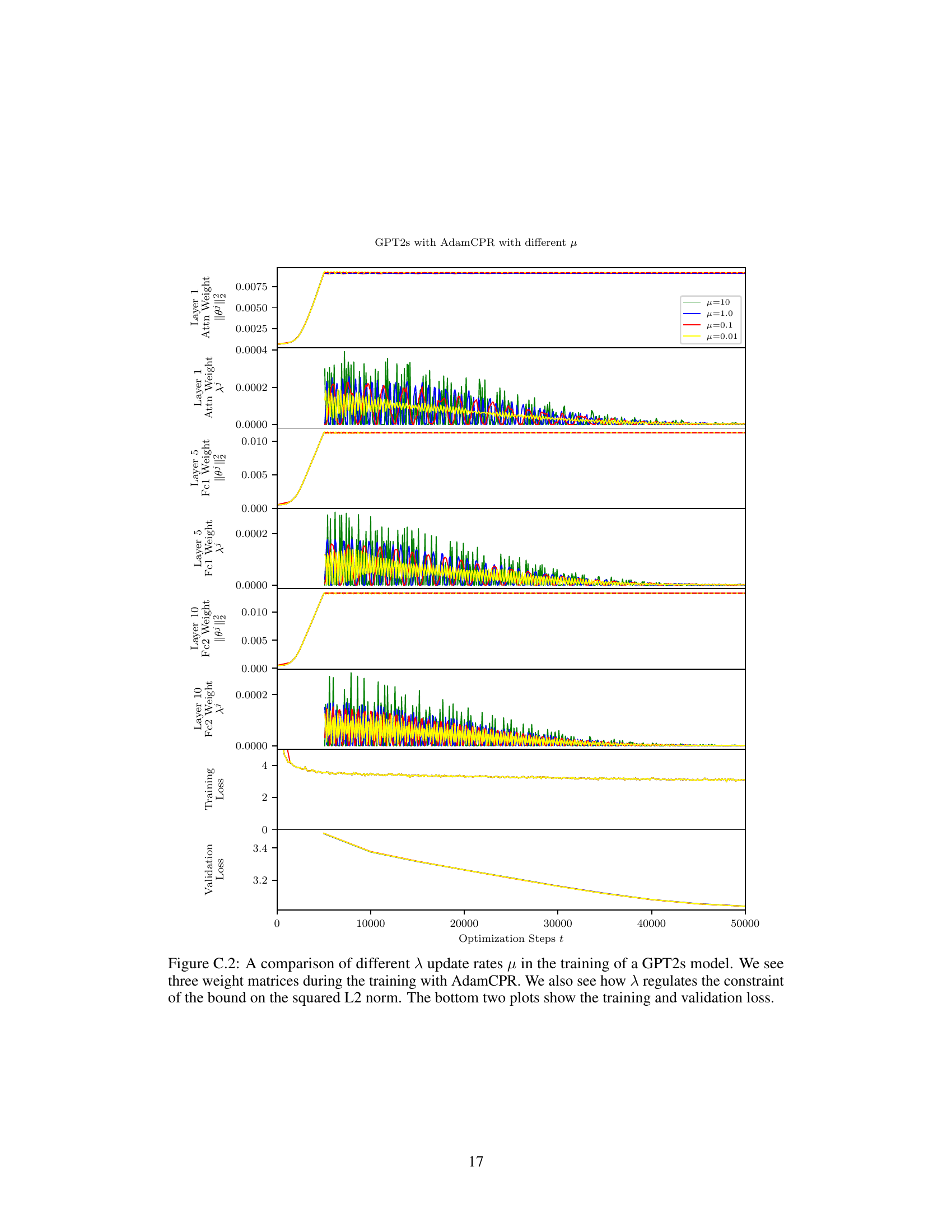

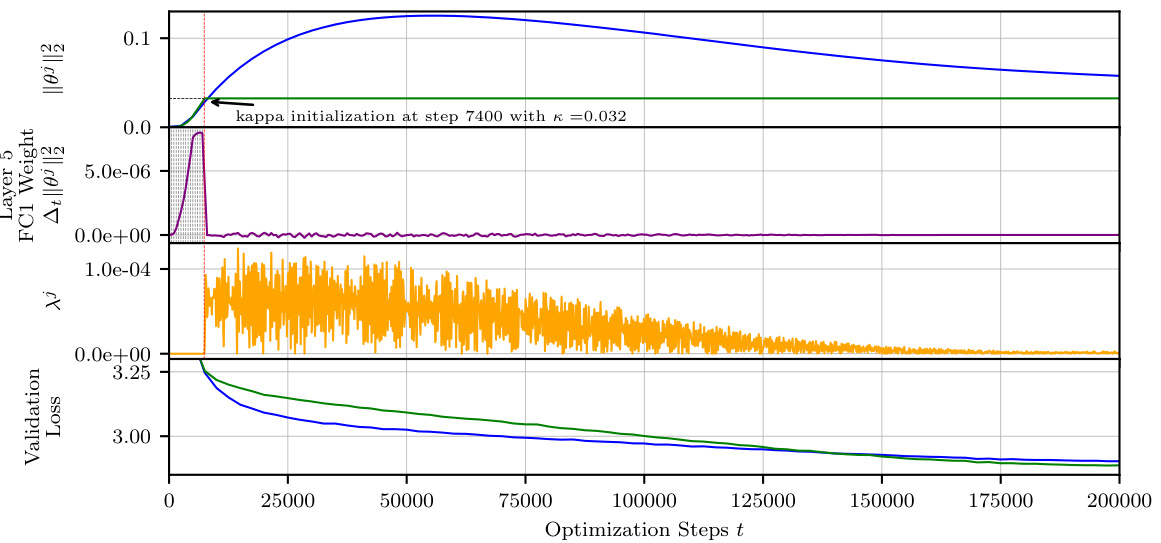

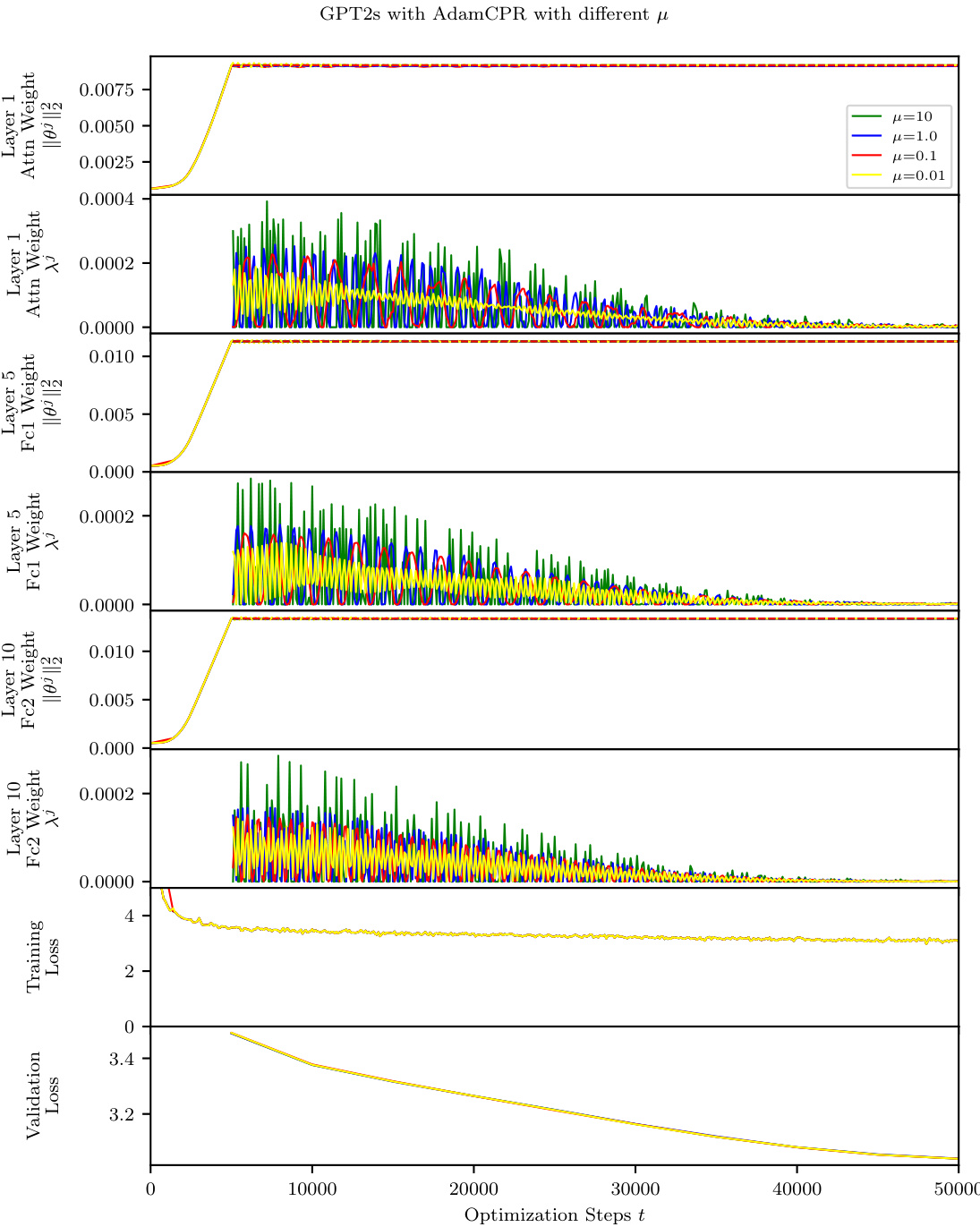

This figure compares the training dynamics of AdamCPR with different values of the Lagrange multiplier update rate (μ) on a GPT2s model. The top three panels display the squared L2-norm of the weight matrices for three different layers of the network over training iterations. These demonstrate the effect of μ on constraining the weight matrices. The bottom two panels show the training and validation loss curves, illustrating the overall performance achieved with varying values of μ. The results show that the algorithm’s stability and overall performance are largely insensitive to the specific choice of the μ parameter within a wide range.

This figure shows the training curves of a GPT-2 small language model trained using the Adam optimizer with either weight decay (AdamW) or constrained parameter regularization (CPR) using the Kappa-IP initialization strategy. The y-axis represents the perplexity, a measure of the model’s performance, and the x-axis represents the number of optimization steps. The figure demonstrates that CPR outperforms AdamW, achieving a similar perplexity score with fewer optimization steps, suggesting improved training efficiency.

The figure shows the training curves of a GPT2s model trained using two different optimizers: AdamW (with weight decay) and AdamCPR (with the Kappa-IP constraint initialization). The x-axis represents the number of optimization steps, and the y-axis shows the perplexity. The results demonstrate that AdamCPR achieves lower perplexity (better performance) than AdamW using fewer optimization steps, indicating improved efficiency and potentially better generalization.

This figure compares the performance of the AdamW optimizer with weight decay against the AdamCPR optimizer with the Kappa-IP initialization strategy. The y-axis represents the perplexity of a GPT2s language model during training, a measure of how well the model predicts the next word in a sequence. The x-axis shows the number of optimization steps. The figure demonstrates that AdamCPR achieves a lower perplexity (better performance) than AdamW, and reaches the same level of performance with approximately two-thirds the number of training steps.

This figure compares the training performance of GPT-2 small model using AdamW (Adam with weight decay) and AdamCPR (Adam with Constrained Parameter Regularization) using the Kappa-IP initialization strategy. The x-axis represents the number of optimization steps, and the y-axis shows the perplexity, a measure of how well the model predicts the next token in a sequence. The results demonstrate that AdamCPR achieves a lower perplexity (better performance) than AdamW, and it reaches the same perplexity with significantly fewer optimization steps. This highlights the efficiency of CPR in deep learning optimization.

The figure shows the training curves of perplexity vs. optimization steps for three different training methods: AdamW with a weight decay of 200k steps, AdamW with a weight decay of 300k steps, and AdamCPR with Kappa-IP and 200k steps. AdamCPR outperforms AdamW with the same budget (200k steps) and reaches the same score as AdamW with 300k steps by only using 2/3 of the budget.

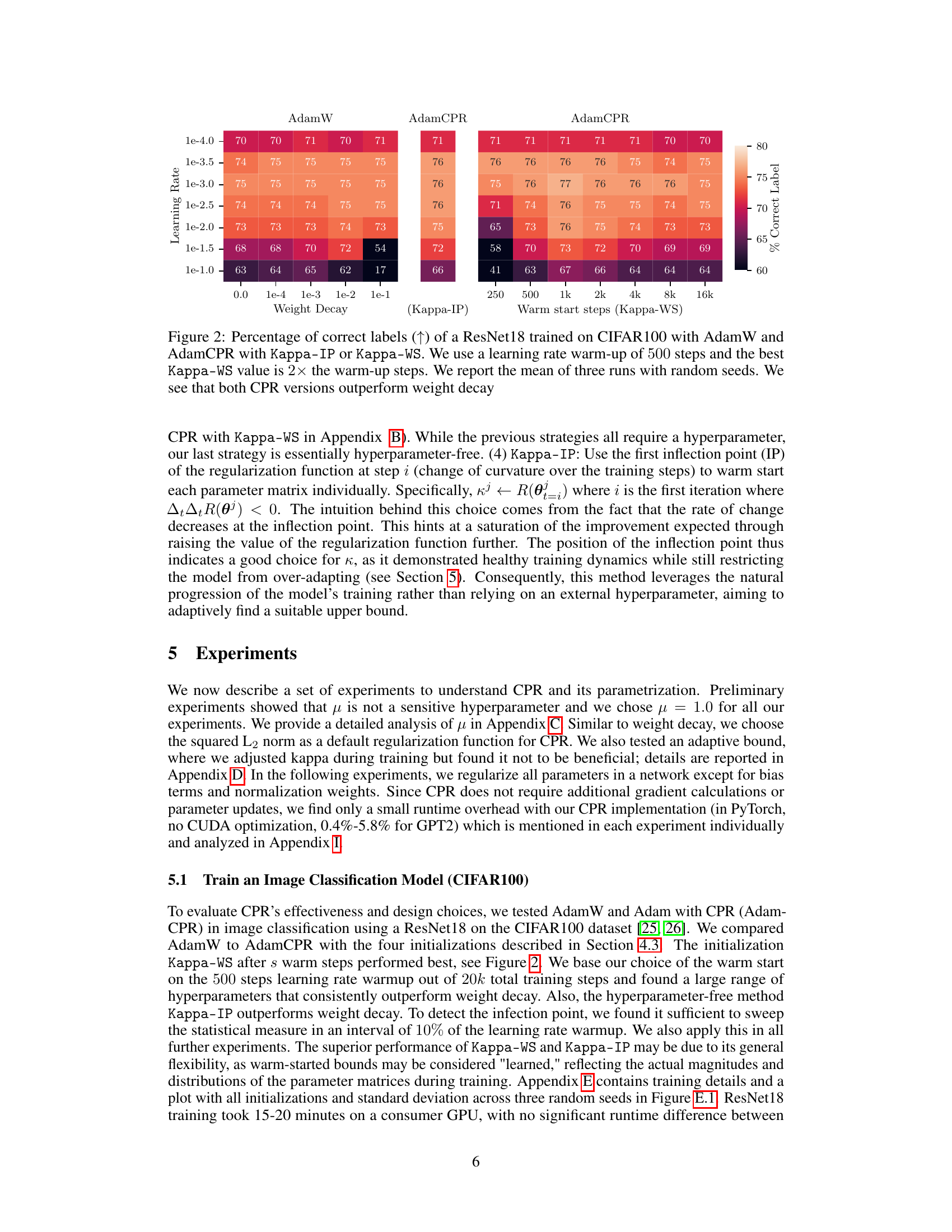

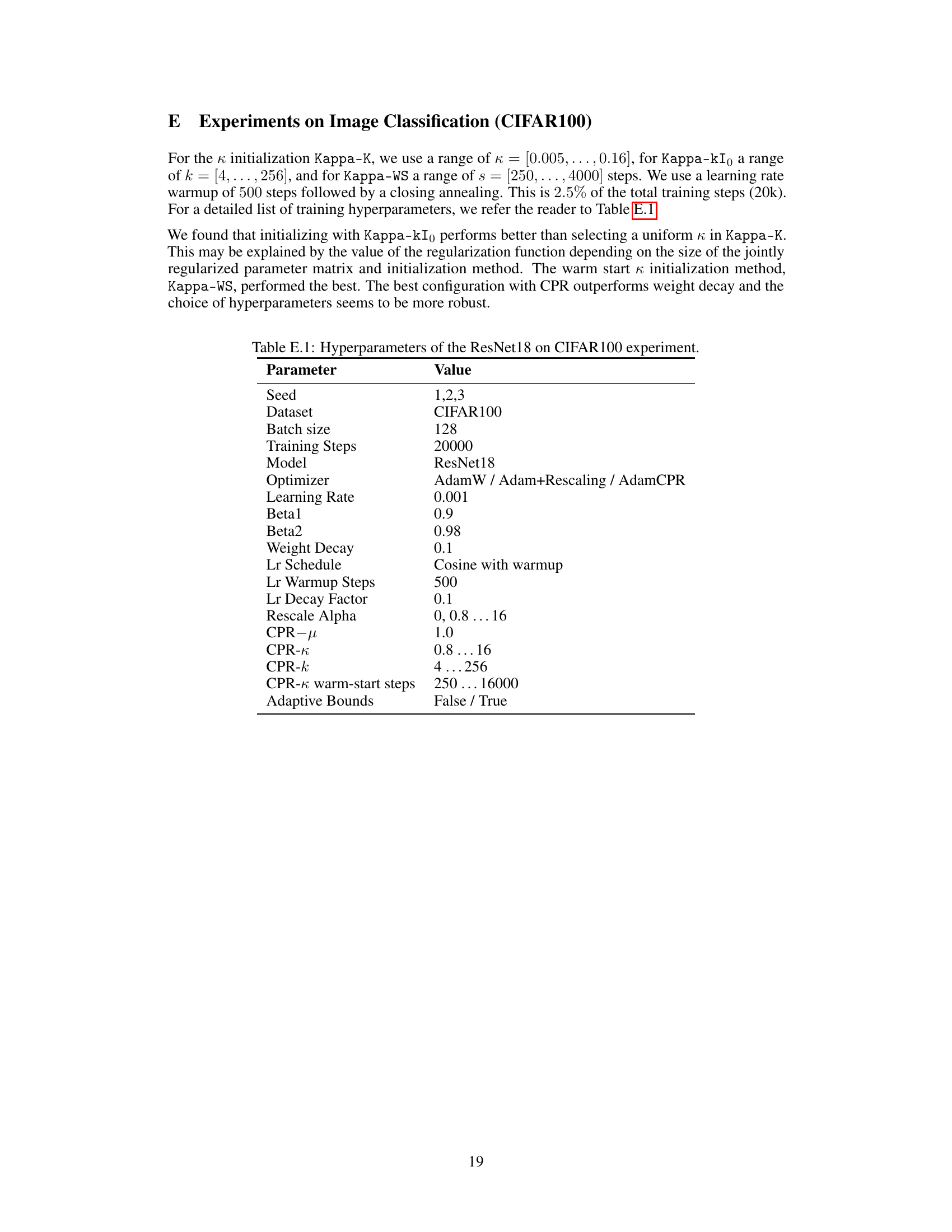

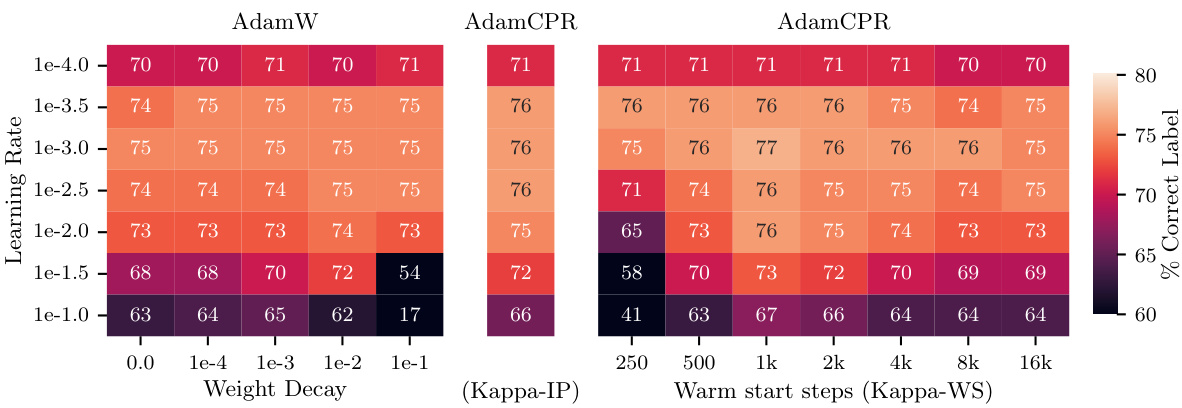

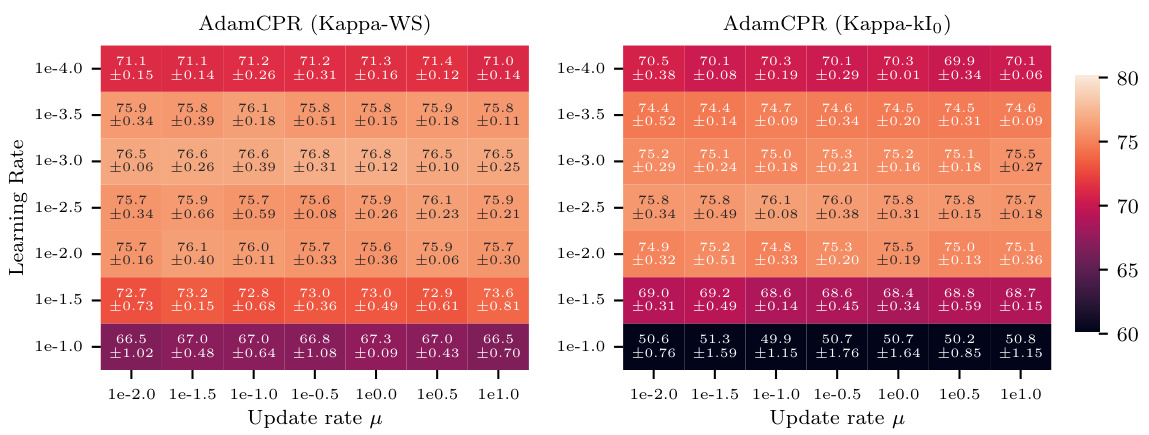

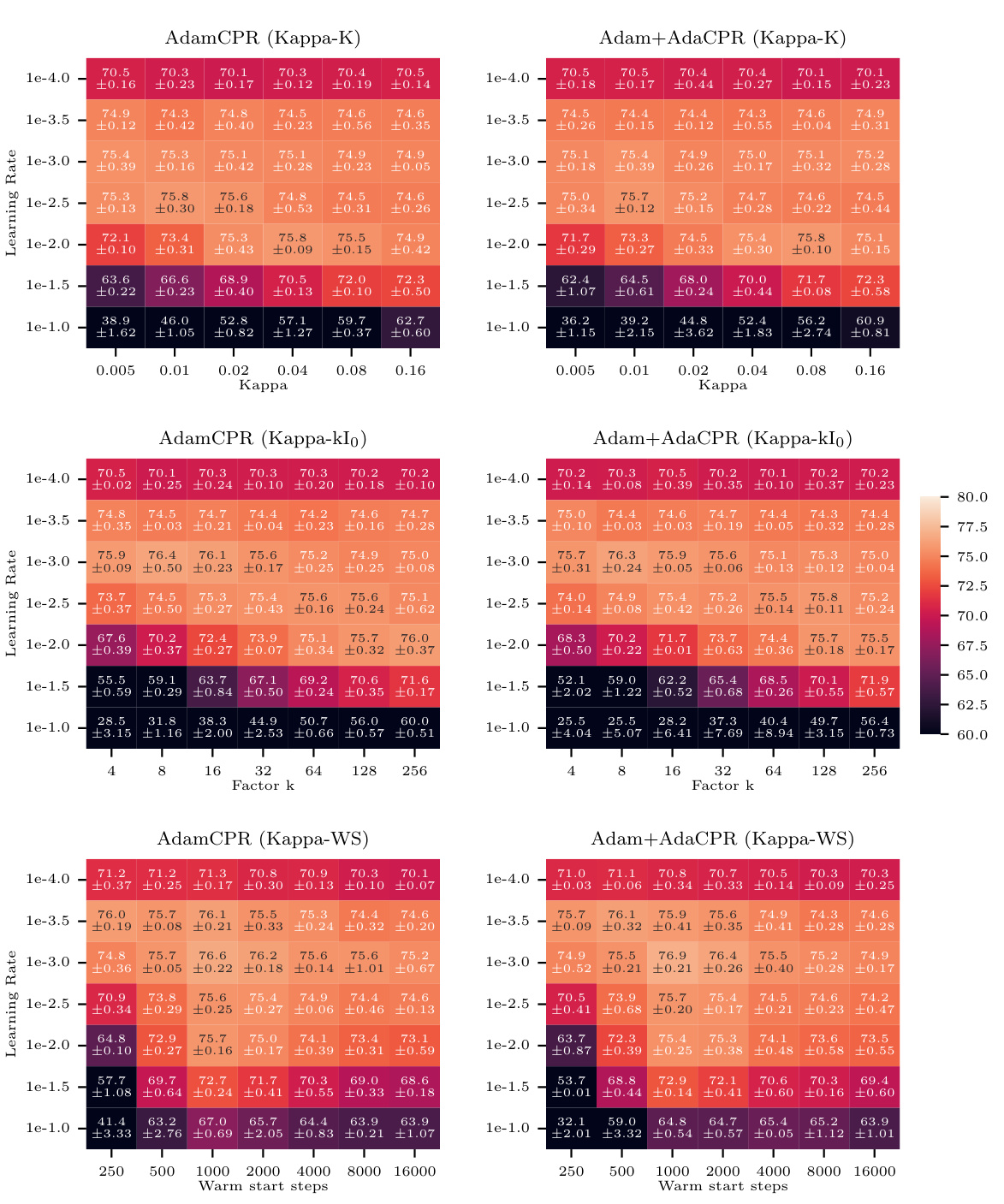

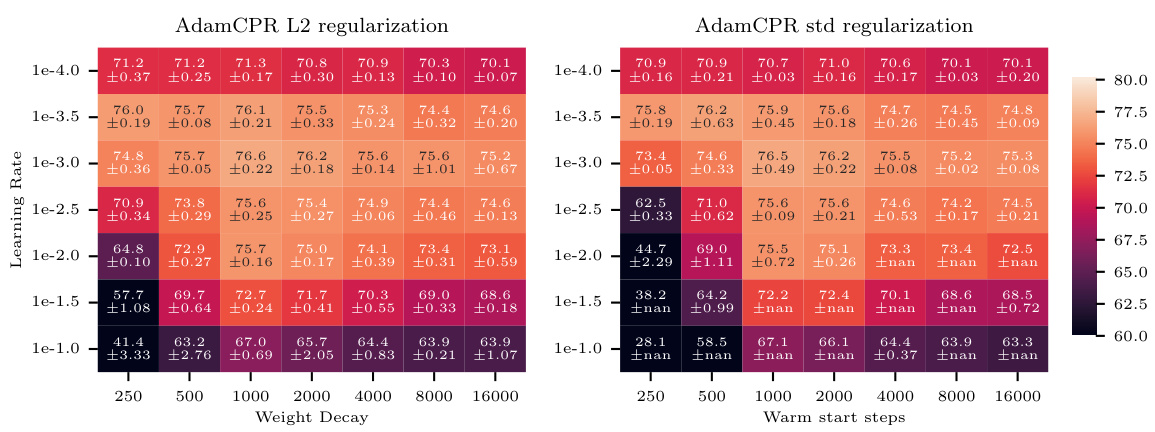

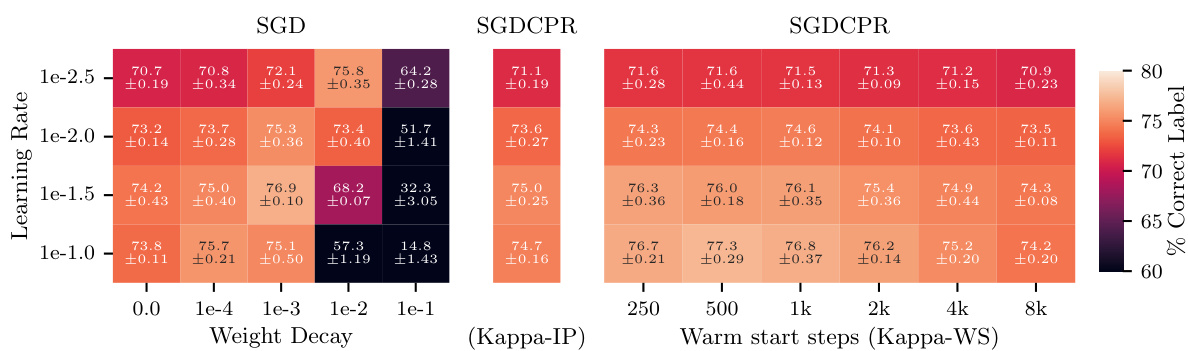

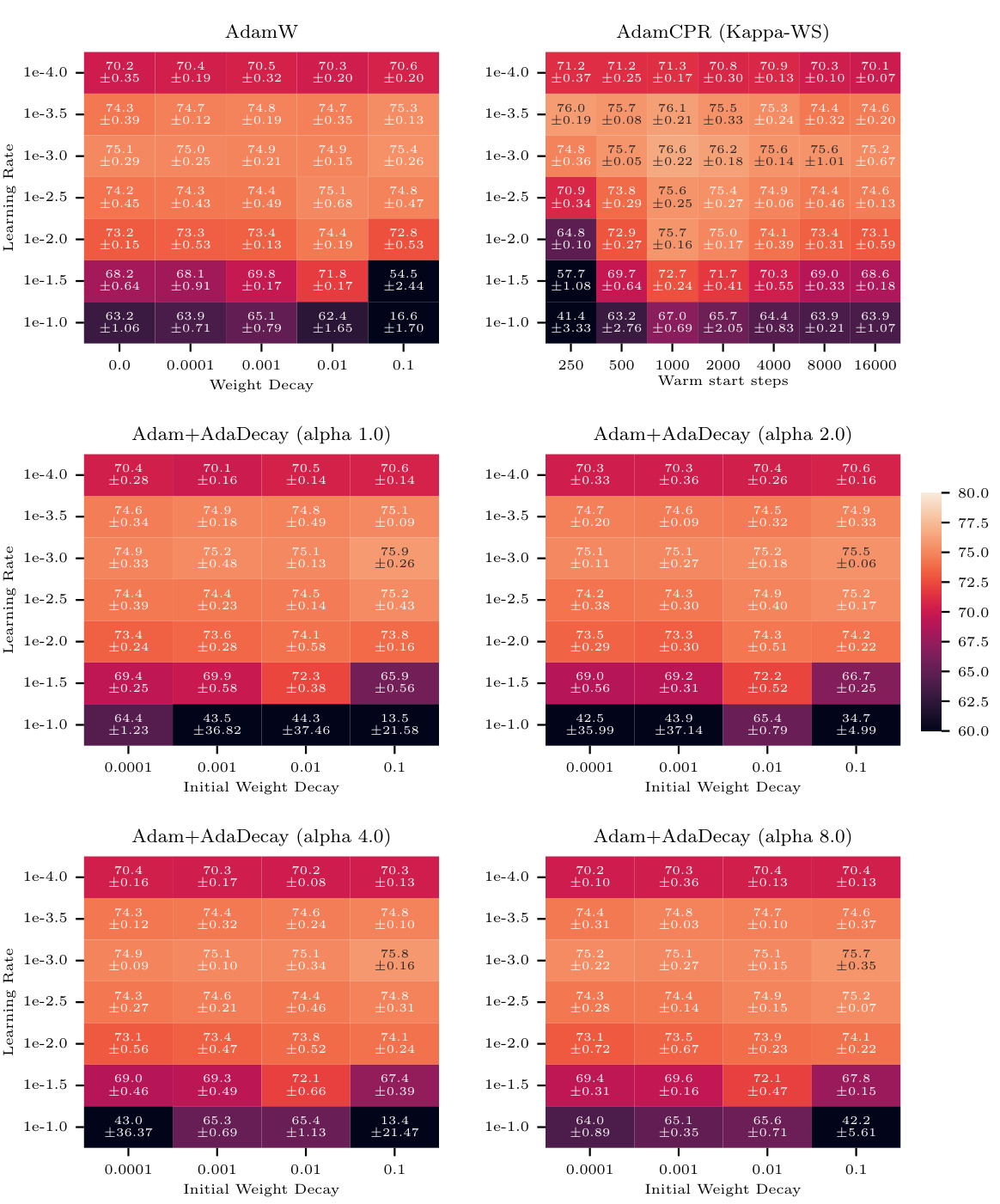

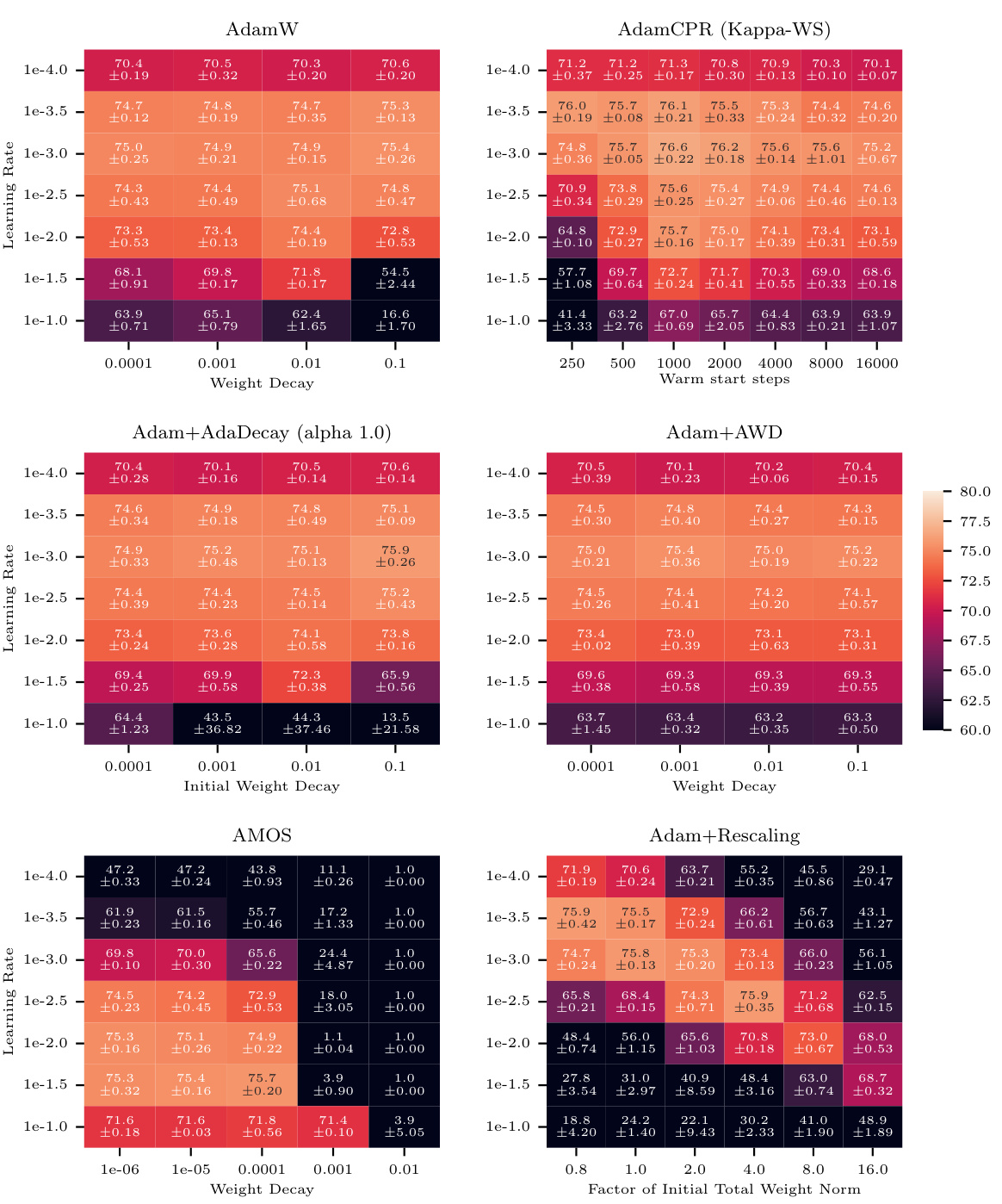

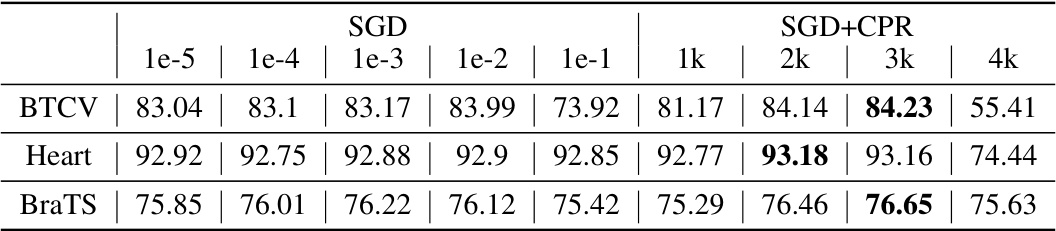

This figure displays the performance of AdamW and AdamCPR (with Kappa-IP and Kappa-WS initialization strategies) on the CIFAR100 image classification task using a ResNet18 model. The results show the percentage of correctly classified labels, plotted against various weight decay values (for AdamW) and warm start steps (for Kappa-WS). The experiment used a learning rate warm-up of 500 steps, and the optimal Kappa-WS value was determined to be twice the warm-up steps. The mean accuracy over three separate runs with different random seeds is reported, demonstrating that both CPR approaches surpass the performance of AdamW across a range of hyperparameter settings.

The figure shows the perplexity (a measure of how well a language model predicts a sequence of words) over training steps for three different training methods using the GPT-2 small model. AdamW (with weight decay) and AdamCPR (with Kappa-IP initialization) are compared. AdamCPR shows lower perplexity than AdamW with the same number of training steps, demonstrating superior performance. Another AdamW training run is shown for comparison, highlighting the significant advantage of AdamCPR using the same training budget. It demonstrates that CPR using Kappa-IP can reach the same score while using less than two-thirds of the optimization steps.

This figure shows the performance of AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers on the CIFAR100 image classification task. Two variants of CPR are compared: Kappa-IP (hyperparameter-free) and Kappa-WS (one hyperparameter). The experiment uses a ResNet18 model, and the results show that both CPR methods outperform AdamW with weight decay across a range of learning rates and weight decay values.

The figure shows the training curves of GPT-2 small model using Adam optimizer with weight decay and Adam optimizer with CPR (Constrained Parameter Regularization). The CPR method uses Kappa-IP initialization strategy, which is a hyperparameter-free method. The results show that Adam with CPR outperforms AdamW, achieving the same perplexity with only 2/3 of the optimization steps (training budget). This demonstrates the effectiveness of CPR in improving the optimization process of deep learning models.

The figure shows the training curves of a GPT-2 small language model trained with the Adam optimizer using either weight decay (AdamW) or constrained parameter regularization (CPR). The CPR method uses the Kappa-IP initialization strategy. The graph plots perplexity against the number of optimization steps. The results demonstrate that AdamCPR achieves lower perplexity (better performance) than AdamW within the same training budget (number of steps), and it reaches a comparable level of performance with approximately 2/3 of the computational cost.

This figure shows the training curves for a GPT-2 small language model trained using the Adam optimizer with either weight decay (AdamW) or Constrained Parameter Regularization (CPR) using the Kappa-IP initialization strategy. The y-axis represents the perplexity, a measure of how well the model predicts the next word in a sequence. The x-axis represents the number of optimization steps. The figure demonstrates that CPR achieves a lower perplexity (better performance) than AdamW with the same training budget (number of steps), and even reaches the same performance level with only two-thirds of the computational resources.

More on tables

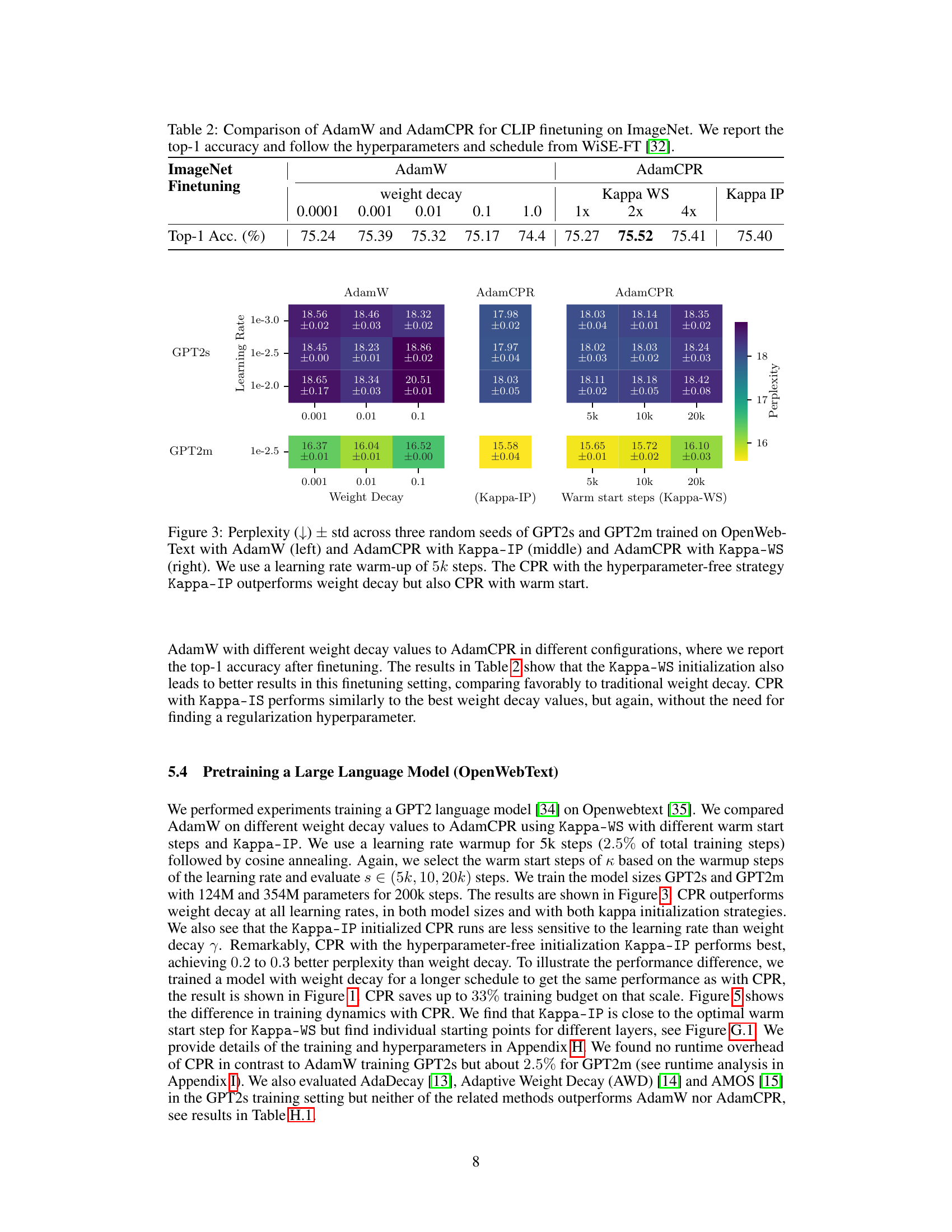

This table presents the results of a fine-tuning experiment using the CLIP model on the ImageNet dataset. It compares the performance of AdamW (with varying weight decay values) against AdamCPR (using Kappa WS and Kappa IP initializations, each with different multiples of the learning rate warmup). The top-1 accuracy is reported for each configuration, highlighting the effectiveness of AdamCPR in this fine-tuning task. The hyperparameter settings used in this experiment adhere to those defined in the WiSE-FT paper.

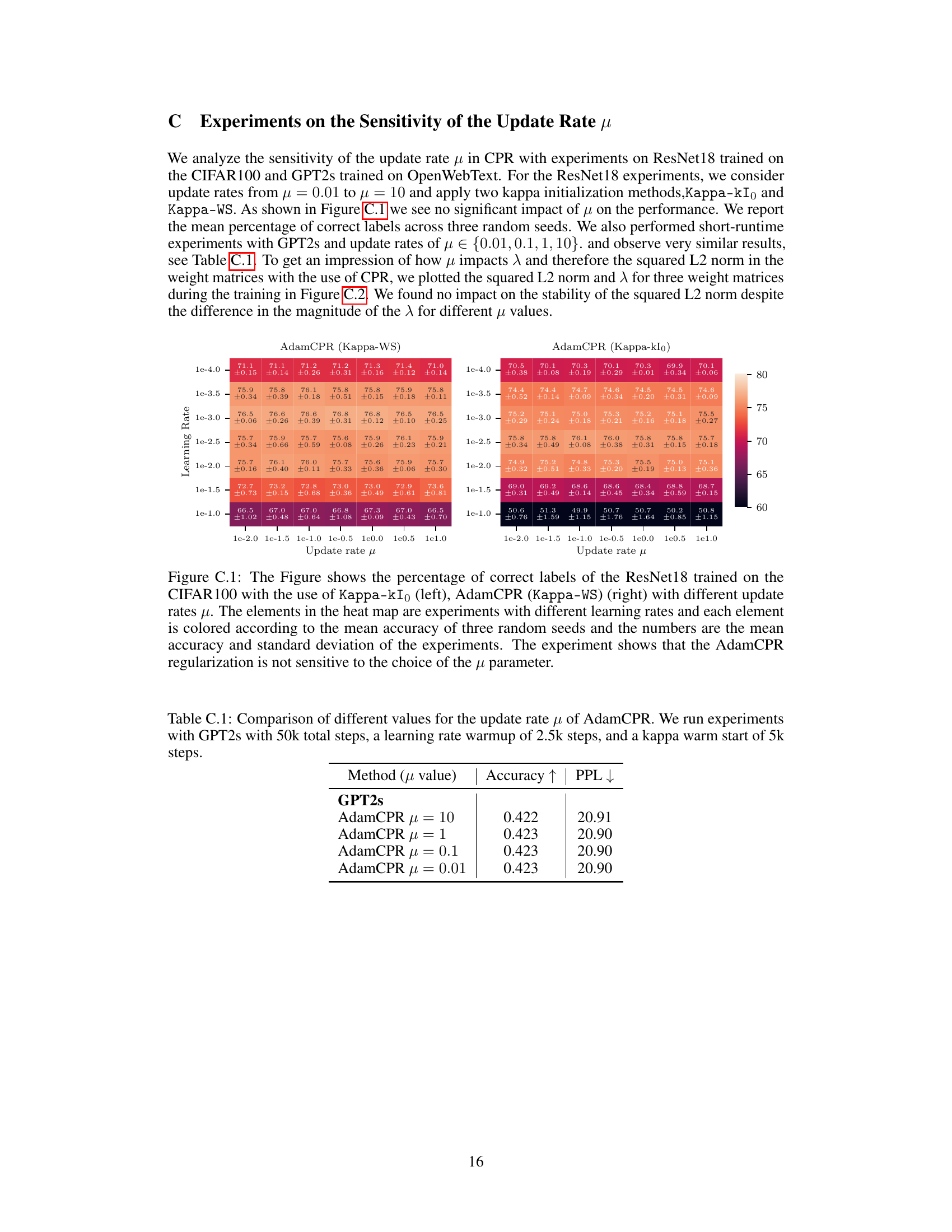

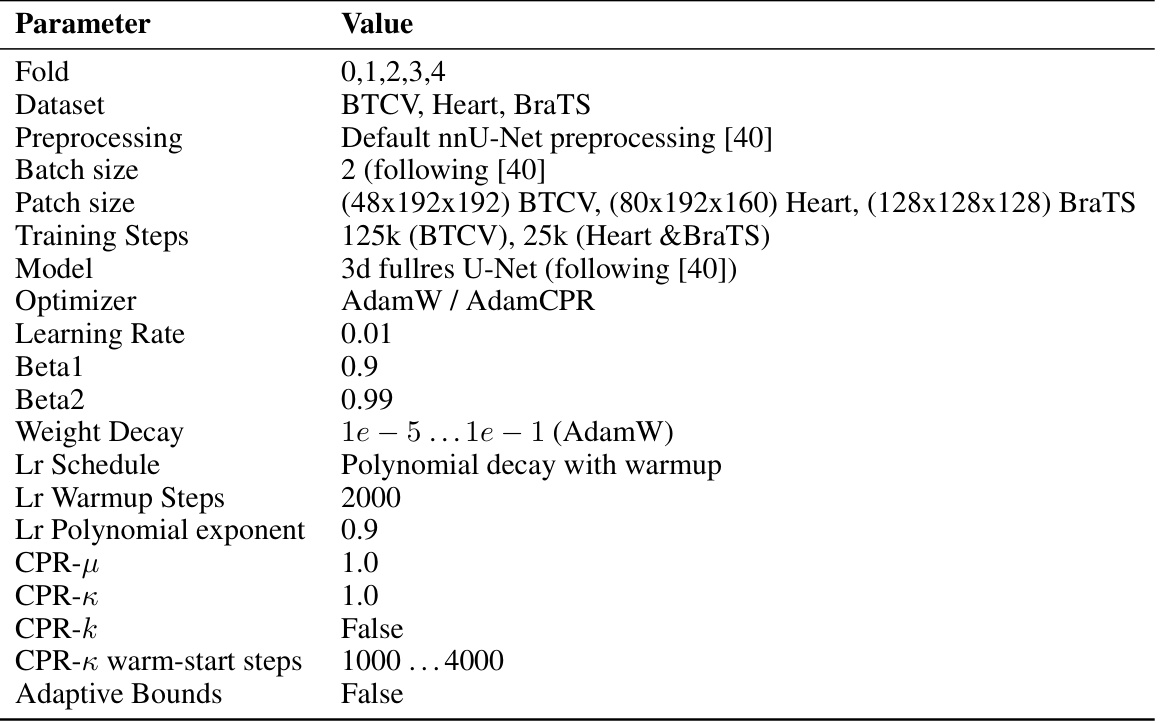

This table presents the results of experiments on the sensitivity of the update rate (μ) in the CPR method. The experiments used the GPT2s model and involved 50,000 total training steps, a learning rate warm-up of 2,500 steps, and a kappa warm start of 5,000 steps. Four different values for μ were tested (10, 1, 0.1, and 0.01), and the accuracy and perplexity scores are reported for each value.

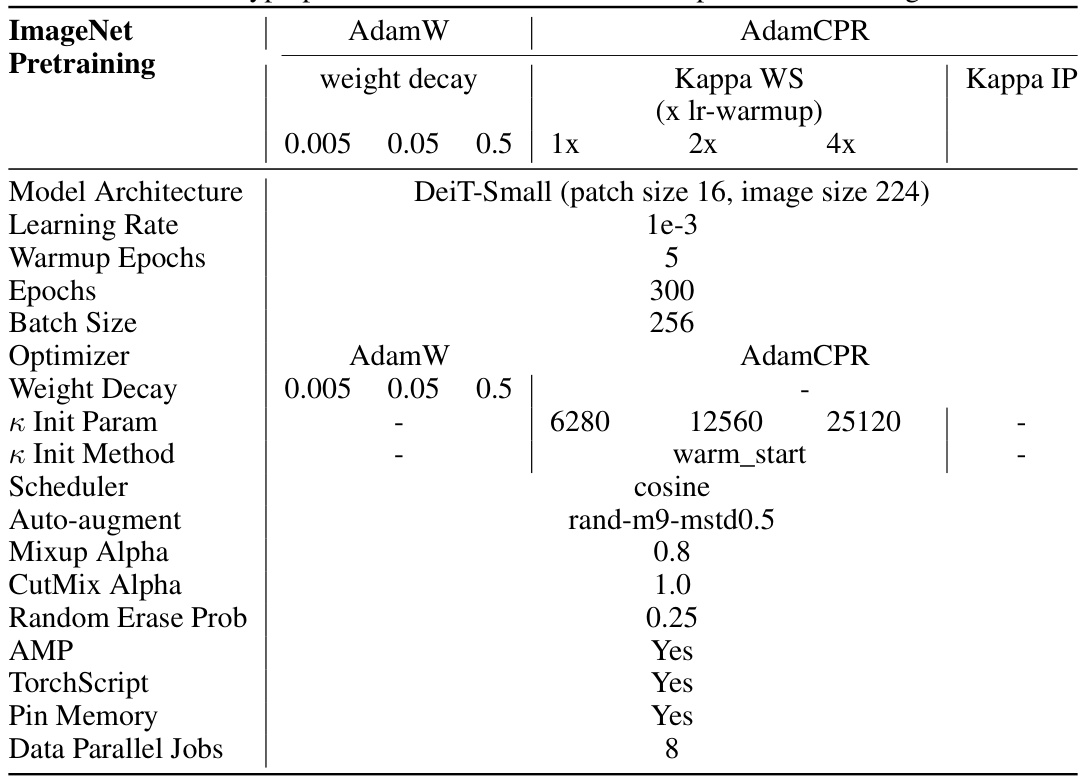

This table compares the performance of AdamW and AdamCPR on the ImageNet dataset using two different DeiT models: a small model with 22 million parameters and a base model with 86 million parameters. It shows the top-1 accuracy achieved by each optimizer for different weight decay values (for AdamW) and different Kappa-WS and Kappa-IP values (for AdamCPR). The table highlights the impact of different regularization strategies on the accuracy of pre-trained vision transformers.

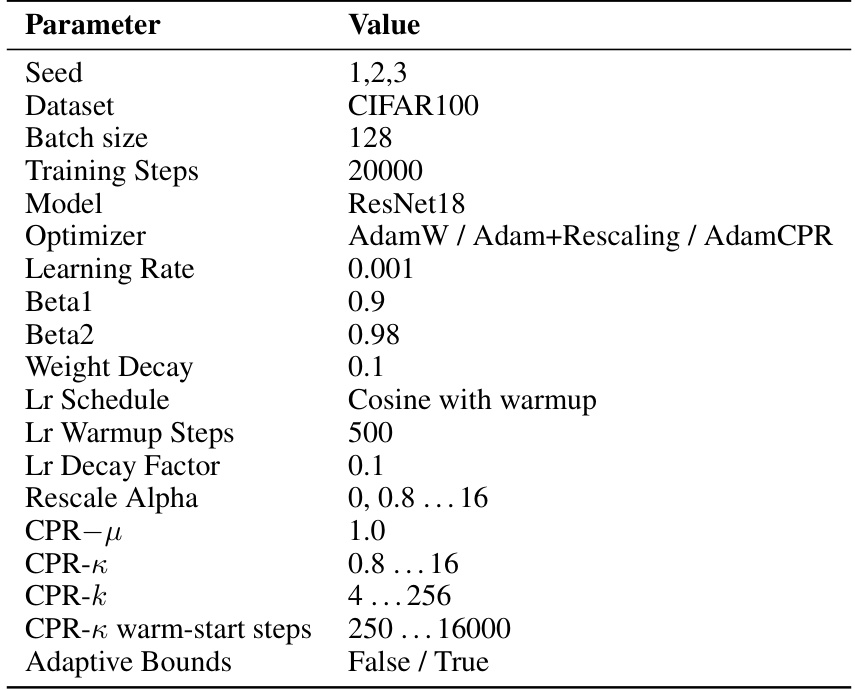

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the DeiT-Small model on the ImageNet dataset. It specifies settings for both AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers, including weight decay values, learning rate, warmup epochs, training epochs, batch size, and data augmentation techniques. The table also shows the initialization parameters and methods for the CPR optimizer’s constraint values.

This table presents the results of comparing AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers on DeiT (Data-efficient Image Transformer) models for ImageNet image classification. Two model sizes are used: a small model with 22 million parameters and a base model with 86 million parameters. The comparison focuses on the Top-1 accuracy achieved using different weight decay values (for AdamW) and different initialization strategies for CPR (Kappa WS and Kappa IP). The table highlights the performance gains achieved with CPR compared to AdamW under various conditions.

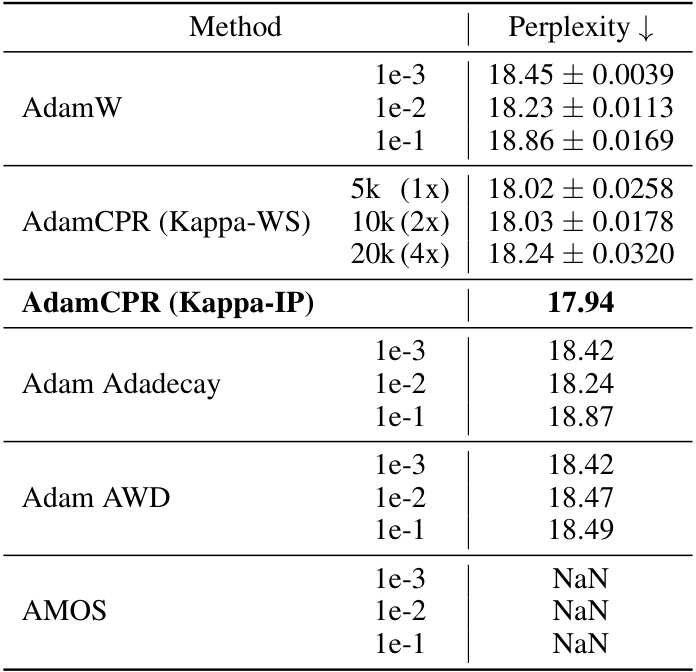

This table compares the performance of different optimization methods (AdamW, AdamCPR with Kappa-WS and Kappa-IP, AdaDecay, AWD, AMOS) on a GPT2s language model trained using the OpenWebText dataset. The results are presented as perplexity scores, a lower score indicating better performance. For AdamW and AdamCPR, average perplexity over three runs is reported, while for other optimizers a single run’s results are shown. The numbers next to each method indicate the corresponding weight decay coefficient (γ) for AdamW, AdaDecay, AWD, and AMOS, while for AdamCPR it indicates the number of warm-up steps used for the Kappa-WS initialization strategy. Note that AMOS resulted in NaN (Not a Number) perplexity values across the board.

This table presents the results of comparing AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers on DeiT models (small and base sizes) for ImageNet image classification. The models were trained with varying weight decay values for AdamW and different Kappa initialization strategies for AdamCPR (Kappa WS and Kappa IP). The table shows the Top-1 accuracy achieved for each model size and optimizer configuration.

This table presents a comparison of the AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers on DeiT models (small and base versions) trained on the ImageNet dataset. It showcases the performance (Top-1 accuracy) achieved using different weight decay values for AdamW and different parameter initialization strategies (Kappa-WS and Kappa-IP) for AdamCPR. The results highlight the impact of different regularization techniques on the models’ performance.

This table compares the performance of AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers on DeiT models (small and base sizes) trained on the ImageNet dataset. It shows the top-1 accuracy achieved using different weight decay values (for AdamW) and different Kappa initialization methods (for AdamCPR). The results highlight the impact of various regularization strategies on model accuracy for different model sizes.

This table compares the performance of AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers on DeiT models (small and base versions) for ImageNet image classification. It shows the top-1 accuracy achieved using different weight decay values for AdamW and different Kappa (WS and IP) initializations for AdamCPR. The results highlight the performance gains using AdamCPR compared to AdamW, particularly with the hyperparameter-free Kappa IP.

This table compares the performance of AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers on DeiT models (small and base versions) for ImageNet image classification. It shows the top-1 accuracy achieved using different weight decay values (for AdamW) and different initialization strategies (Kappa WS, Kappa IP) for AdamCPR. The results demonstrate that AdamCPR with appropriate parameter initialization can surpass the performance of AdamW.

This table presents the results of comparing AdamW and AdamCPR optimizers on DeiT models (small and base sizes) for ImageNet image classification. Different weight decay values are used for AdamW, while AdamCPR utilizes the Kappa-WS and Kappa-IP initialization strategies. The table shows Top-1 accuracy achieved by each configuration, highlighting the performance differences between the optimizers and initialization methods.

This table compares the performance of AdamW and AdamCPR on the ImageNet dataset using DeiT, a vision transformer model. Two model sizes are used: small (22M parameters) and base (86M parameters). Different weight decay values are tested for AdamW, while AdamCPR uses the Kappa-WS and Kappa-IP initialization strategies. The top-1 accuracy is reported for each configuration.

Full paper#