↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Generating realistic 3D models of articulated objects (objects with moving parts) remains a significant challenge. Existing methods often struggle with quality, consistency, and the ability to control the generation process. They also lack interpretability, making it difficult to understand how the models are created and why they look the way they do. These limitations hinder the application of these models in various fields.

MIDGARD, a new framework, tackles these challenges by employing a modular approach. It separates the generation process into two stages: structure generation (defining the object’s parts and joints) and shape generation (creating the 3D mesh for each part). This allows for better control and interpretability. The use of diffusion models and a novel graph representation further enhances quality and consistency. Experiments demonstrate MIDGARD’s superiority over existing methods, showing improved quality, consistency, and controllability in generated assets, which are also fully simulatable.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in 3D modeling, robotics, and AI. It introduces a novel framework for generating high-quality, simulatable 3D articulated objects, a significant challenge in current research. The modular, interpretable approach and superior results over existing methods make it highly relevant and open up new avenues for research in various fields such as digital content creation and embodied AI.

Visual Insights#

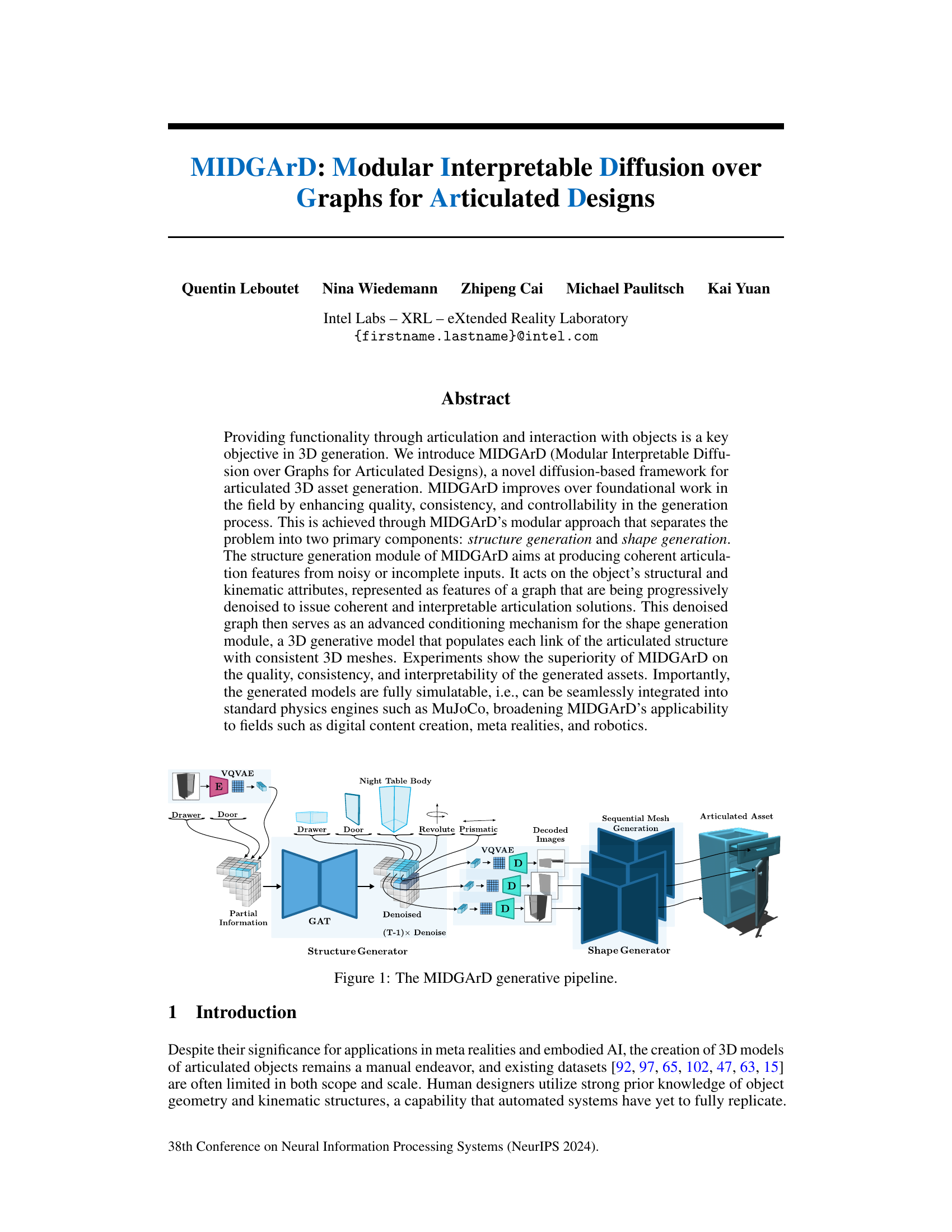

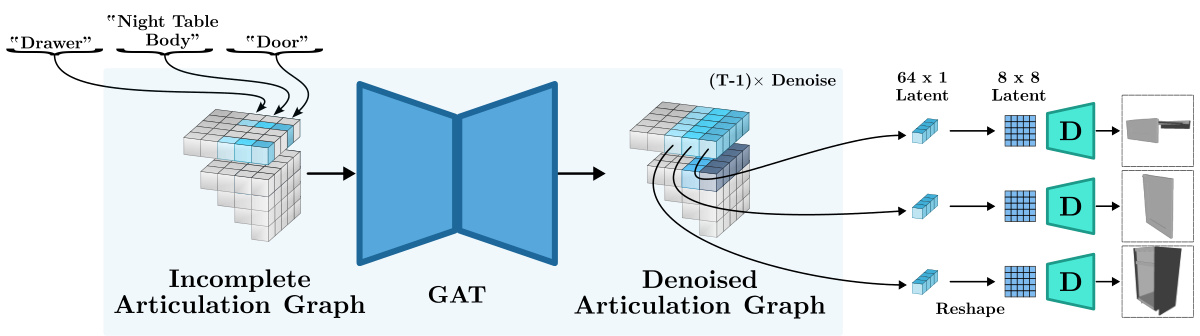

The figure illustrates the MIDGARD generative pipeline, which consists of two main components: a structure generator and a shape generator. The structure generator takes partial or noisy information about an articulated object (e.g., a nightstand with drawers and a door) and uses a graph attention network (GAT) to generate a denoised graph representing the object’s structure and kinematics. This denoised graph is then used to condition the shape generator, which is a 3D generative model that creates high-fidelity 3D meshes for each part of the articulated object. The output of the pipeline is a complete, fully simulatable articulated 3D asset.

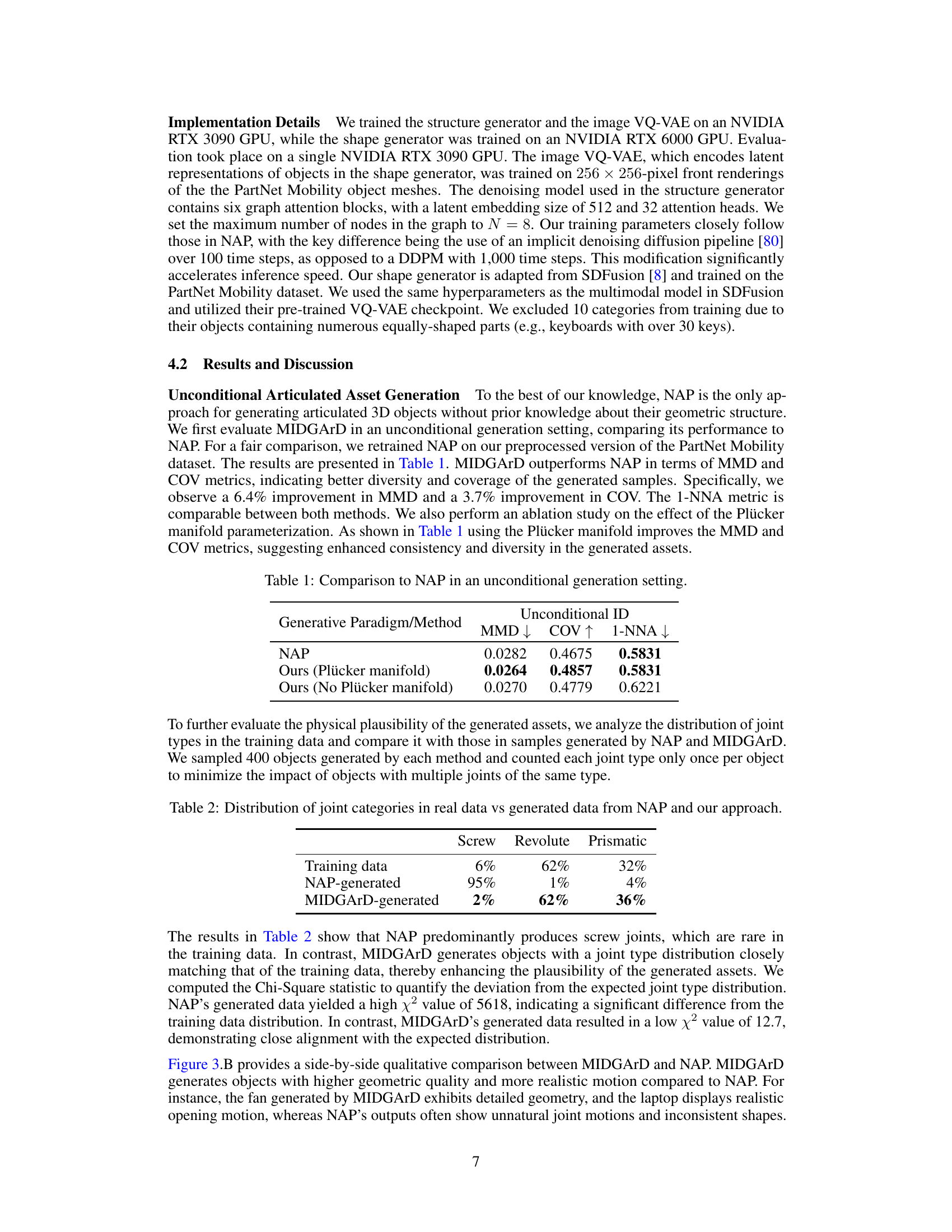

This table presents a comparison of the proposed MIDGARD model and NAP in an unconditional generation setting. The metrics used for comparison are the Unconditional ID, MMD, COV, and 1-NNA. Lower MMD values indicate better diversity, higher COV values indicate better coverage, and lower 1-NNA values indicate better accuracy. The results show that MIDGARD with Plücker manifold outperforms NAP across all metrics.

In-depth insights#

Modular Diffusion#

Modular diffusion models present a powerful paradigm shift in generative modeling. By breaking down the generation process into smaller, independent modules, they offer significant advantages in controllability, interpretability, and scalability. Each module can be trained and optimized separately, focusing on a specific aspect of the generation process, such as structure or shape. This modularity allows for easier experimentation with different architectures and training strategies, leading to more efficient and robust model development. Furthermore, the modular design enhances the interpretability of the model, making it easier to understand the factors influencing the generation process. This granular control also facilitates generating highly complex outputs through the sequential composition of simpler modules and better leverages different data modalities for effective conditioning. Improved consistency and quality are also direct benefits. However, careful design of the interfaces between the modules is crucial to ensure seamless integration and prevent inconsistencies in the overall generated output. The challenge lies in managing the complexity arising from the interactions between modules while maintaining the individual modules’ simplicity and efficiency.

Graph-Based Encoding#

Graph-based encoding offers a powerful paradigm for representing complex structured data within machine learning models. Articulated objects, with their inherent hierarchical structures and kinematic relationships between parts, are ideally suited for this representation. By encoding the object as a graph, where nodes represent individual parts and edges define their connections (joints), the model can learn to understand both the geometric and kinematic properties simultaneously. This approach contrasts sharply with traditional methods, which often treat 3D models as unstructured point clouds or meshes, failing to capture the crucial articulation information. The key advantage lies in the ability to leverage graph neural networks (GNNs) to process the encoded information, enabling the model to learn sophisticated relationships and dependencies between parts. This representation also facilitates enhanced interpretability, as the graph structure itself provides a direct, visual mapping of the object’s composition and articulation. Furthermore, this allows for more efficient control over the generation process by directly manipulating the graph representation, for example, conditioning the model on a specific structural configuration or kinematics. However, challenges remain in optimally encoding diverse object properties as graph features and managing the scalability of the graph representation for complex articulated objects. Future work should focus on refining the graph encoding schemes, exploring more advanced GNN architectures, and addressing the scalability limitations to unlock the full potential of graph-based encoding in the context of articulated object modeling.

Plücker Manifold#

The utilization of the Plücker manifold in MIDGARD offers a novel approach to representing and manipulating articulation parameters within a diffusion model framework. Traditional methods often struggle with the complexities of joint parametrization, especially when dealing with a wide range of joint types and their associated constraints. By operating directly on the Plücker manifold, MIDGARD avoids the need for projection steps that would otherwise be required to maintain the constraints inherent to Plücker coordinates. This results in improved consistency and efficiency during the denoising process, leading to higher-quality and more interpretable articulated asset generation. The choice of this representation directly addresses the limitations of previous approaches which often suffer from unnatural motions or inconsistent shapes, significantly enhancing the overall quality and plausibility of the generated assets. The elimination of projection operations simplifies the computational workflow, enhancing both speed and efficiency of the generation process. This thoughtful application of geometric concepts significantly improves the robustness and controllability of the MIDGARD framework. The effectiveness of this choice highlights the importance of choosing appropriate mathematical representations when dealing with complex geometric problems within machine learning contexts. Further exploration of this approach in different generative modelling tasks could reveal additional beneficial applications.

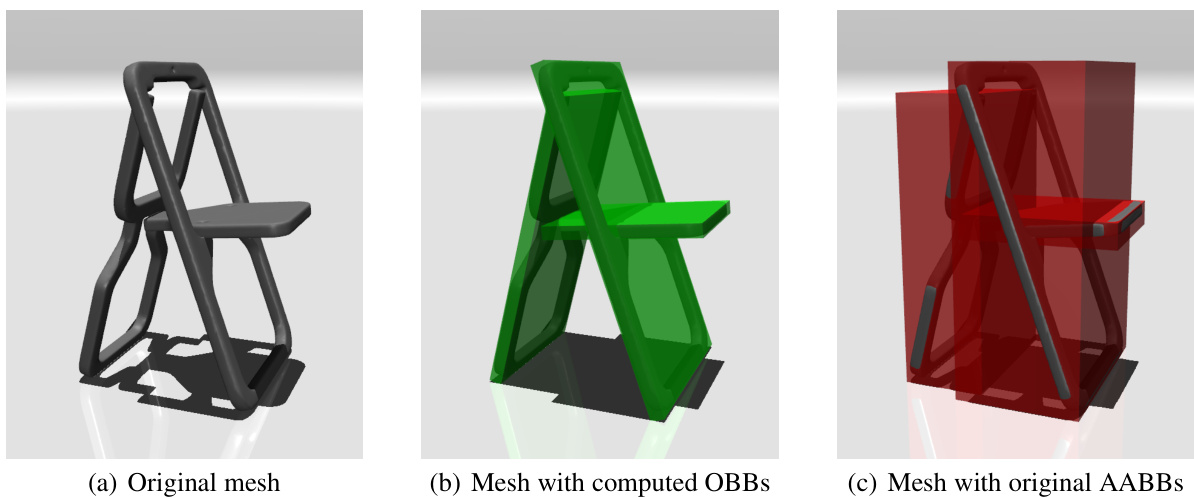

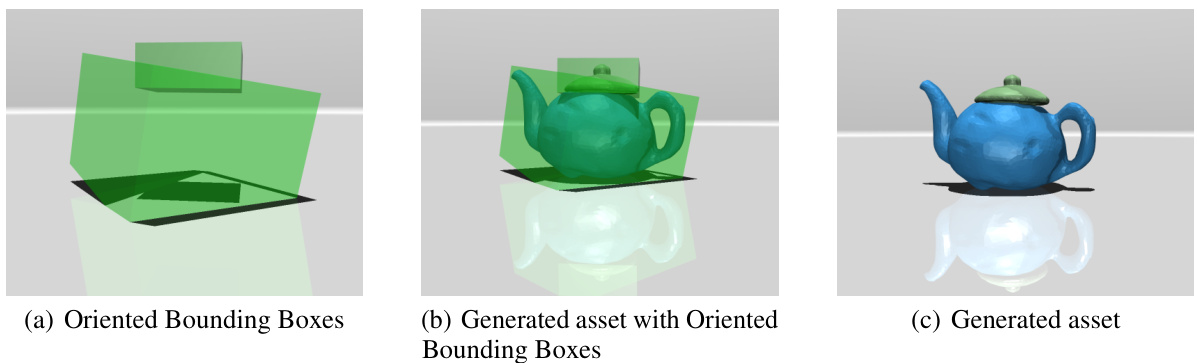

Bounding Box Prior#

The concept of a ‘Bounding Box Prior’ in 3D articulated object generation is a crucial innovation addressing the challenge of generating consistent and realistic object parts. It leverages the inherent spatial relationships between parts by using bounding boxes as constraints during the shape generation process. Instead of generating object components independently, which can lead to size and orientation inconsistencies, this approach uses predefined bounding boxes to guide the shape generation process, ensuring that parts fit together coherently. The bounding boxes provide both geometric constraints (size) and spatial constraints (orientation), improving the consistency and overall quality of the generated articulated assets. This method tackles the challenge of shape generation in a sequential and part-wise manner, where the structure generator provides the essential spatial and kinematic information which is then used as input for the shape generator. This method also introduces significant enhancements in terms of interpretability and controllability, as users can adjust bounding box parameters to fine-tune the generation process. The success of this method lies in its ability to bridge the gap between the abstract structural representation and the concrete 3D mesh generation, resulting in higher-quality and more realistic articulated 3D models.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize enhancing MIDGARD’s scalability to handle more complex articulated objects with numerous parts. Addressing the limitations of current articulation graph representations is crucial, possibly through exploring alternative graph structures or incorporating more sophisticated relational information. Investigating the integration of diverse input modalities beyond images and text, such as haptic data or point clouds, could further improve the quality and controllability of generated assets. Developing more robust evaluation metrics specifically tailored to articulated object generation is needed to provide a more comprehensive assessment of model performance. Finally, exploring alternative generative models beyond diffusion-based approaches could unlock new possibilities, and investigating physics-aware generative models would enhance the realism and usability of the generated assets within simulation or robotics applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

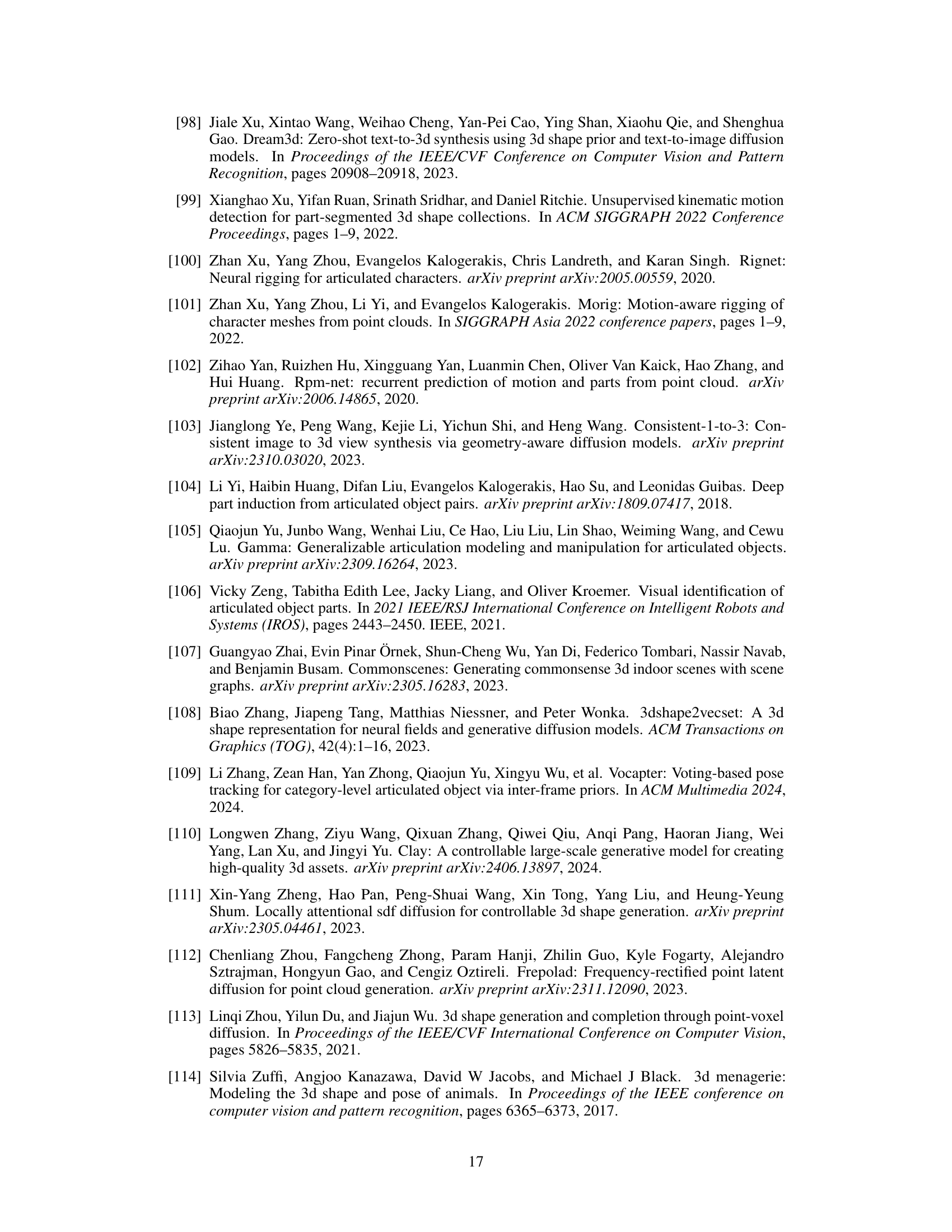

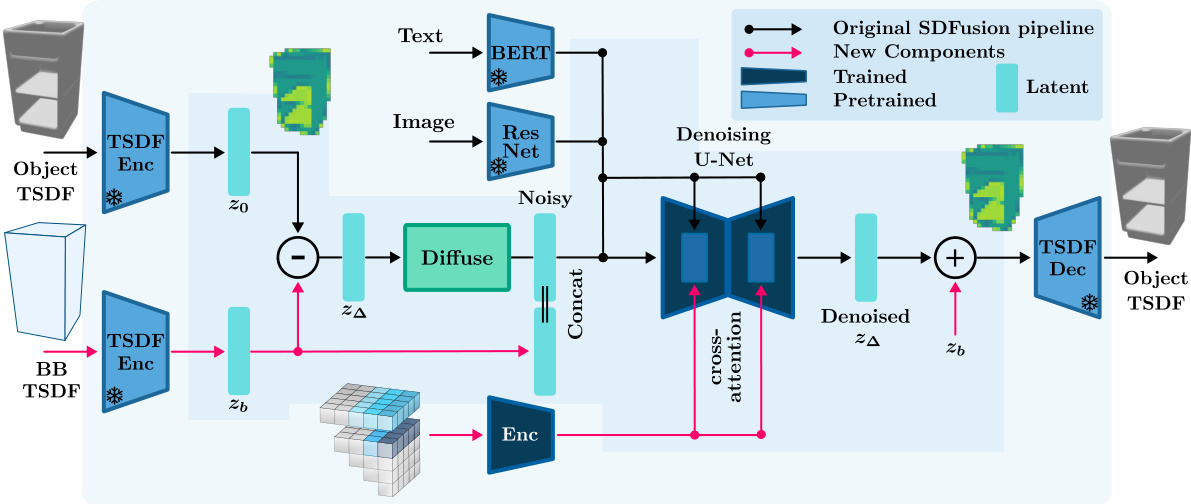

The figure illustrates the architecture of the Shape Generator component of MIDGARD. It details how the model takes in multimodal inputs (image, text, and graph features), processes them through a U-Net architecture for denoising, incorporates a bounding box constraint for consistent shape generation, and finally outputs the mesh representation of the object part. The diagram highlights the original SDFusion pipeline components and new additions made within MIDGARD to achieve improved shape generation.

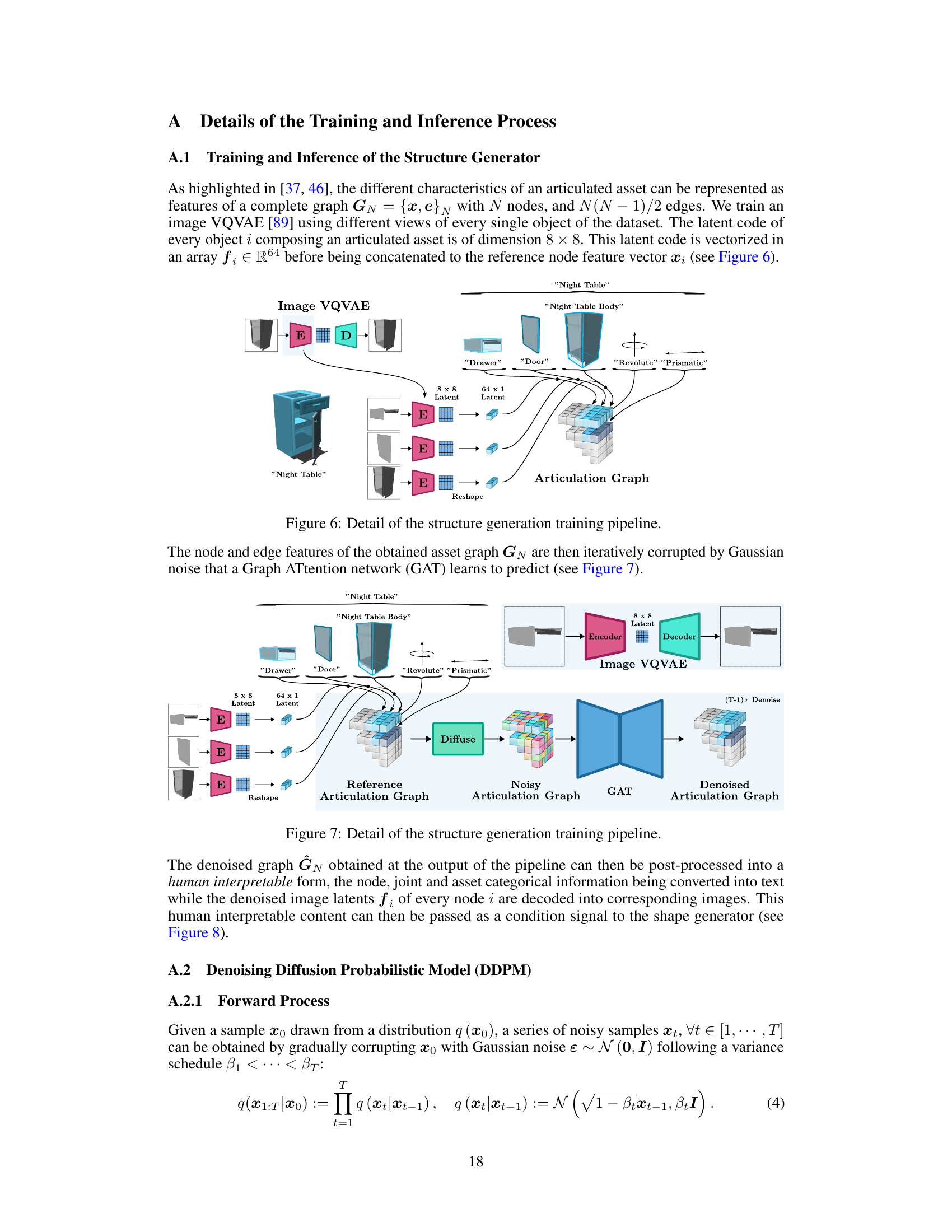

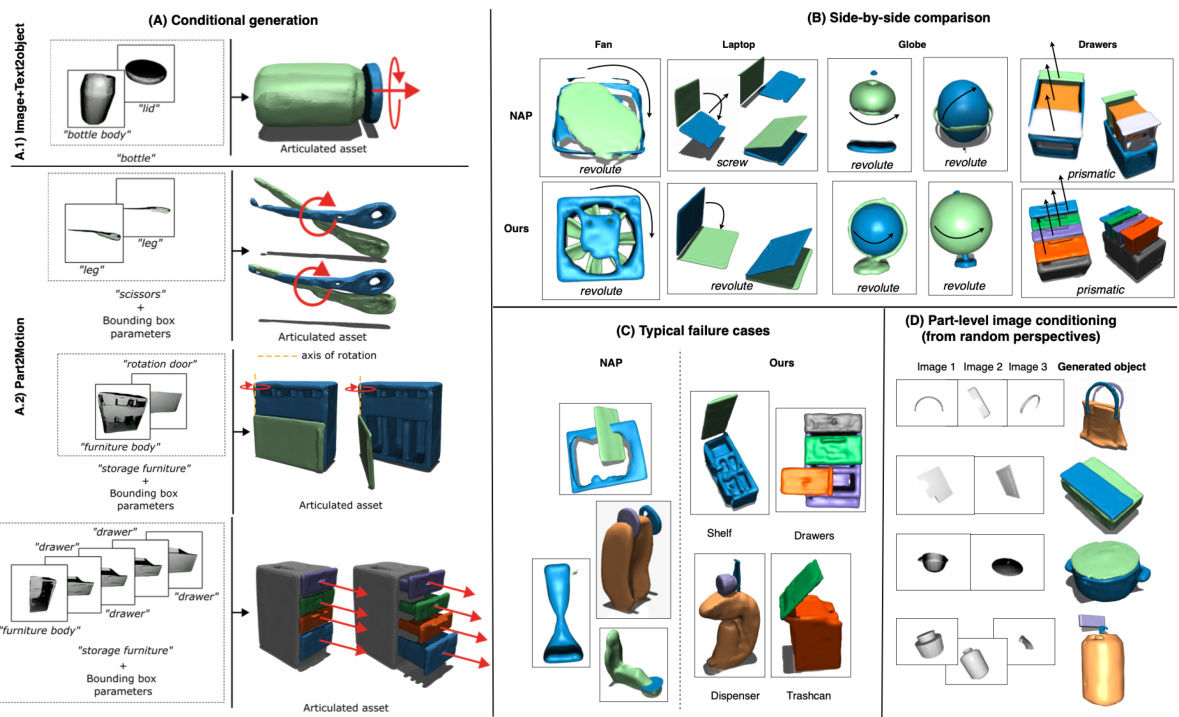

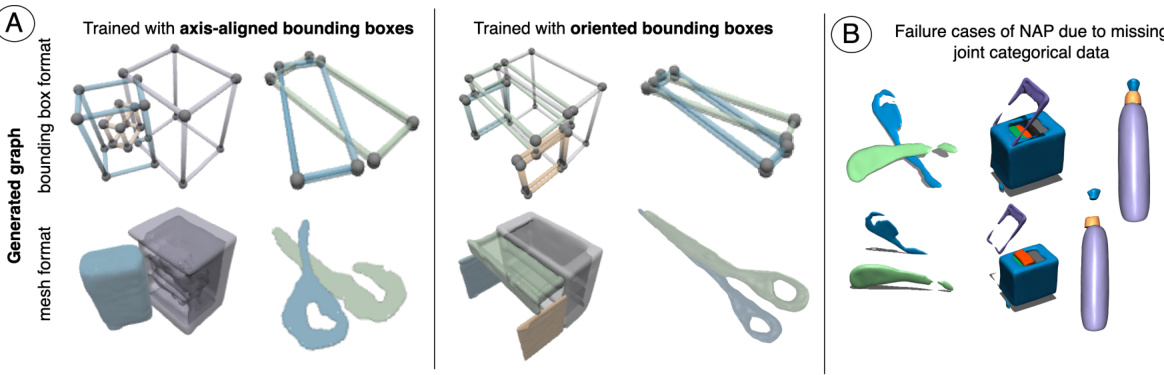

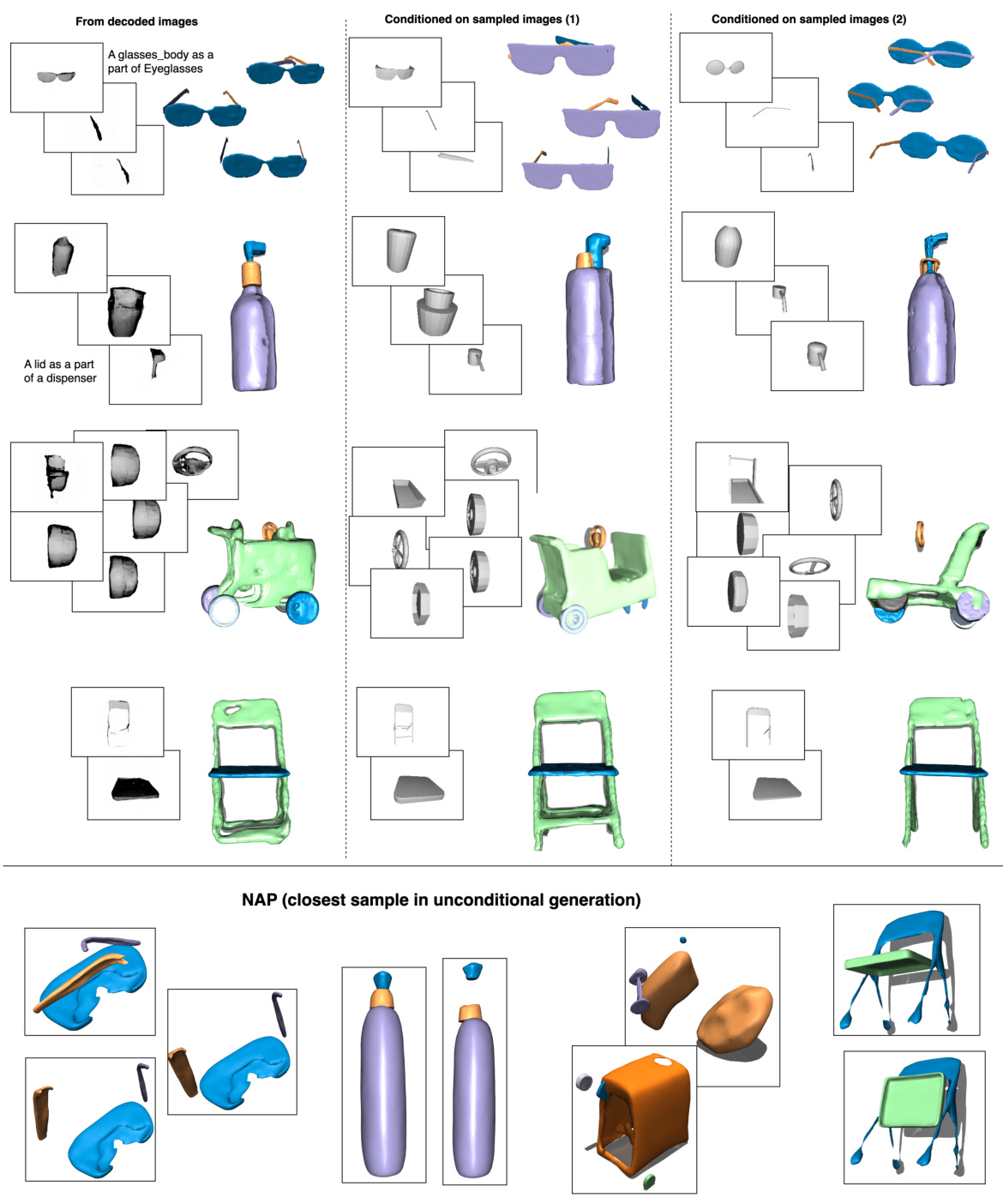

This figure presents a comparative analysis of MIDGARD and NAP across various aspects of articulated object generation. (A) showcases MIDGARD’s ability to generate articulated assets using either image+text or part-level information, highlighting its controllability and conditional generation capabilities. (B) provides a direct comparison of assets generated by MIDGARD and NAP, illustrating MIDGARD’s superior quality, consistency, and natural joint motions. (C) illustrates typical failure cases encountered with NAP, including mismatched parts and unnatural joint movements, while emphasizing MIDGARD’s robustness to these issues. Finally, (D) demonstrates MIDGARD’s part-level image conditioning capability, showing how different input images influence the generated part appearances.

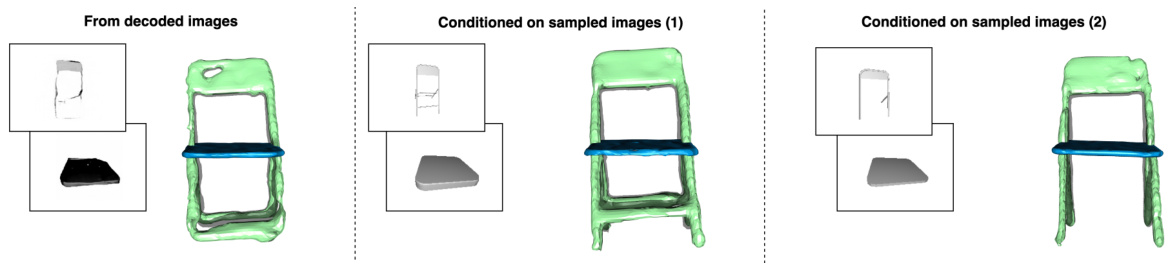

This figure demonstrates the impact of image inputs on the shape generation process within MIDGARD’s framework. By modifying the image inputs, while keeping other factors constant (such as text and graph features), users can adjust the generated parts to achieve a desired aesthetic or functional outcome. This showcases MIDGARD’s flexibility and controllability on a part-level.

This figure shows the failure cases due to the use of axis-aligned bounding boxes and parameter discretization. The left part (A) shows that using axis-aligned bounding boxes tends to confuse the 3D generation model, leading to incorrect results. The right part (B) demonstrates that using the categorical joint variable in MIDGARD helps achieve better joint motion resolution and filters out unrealistic solutions generated by previous methods.

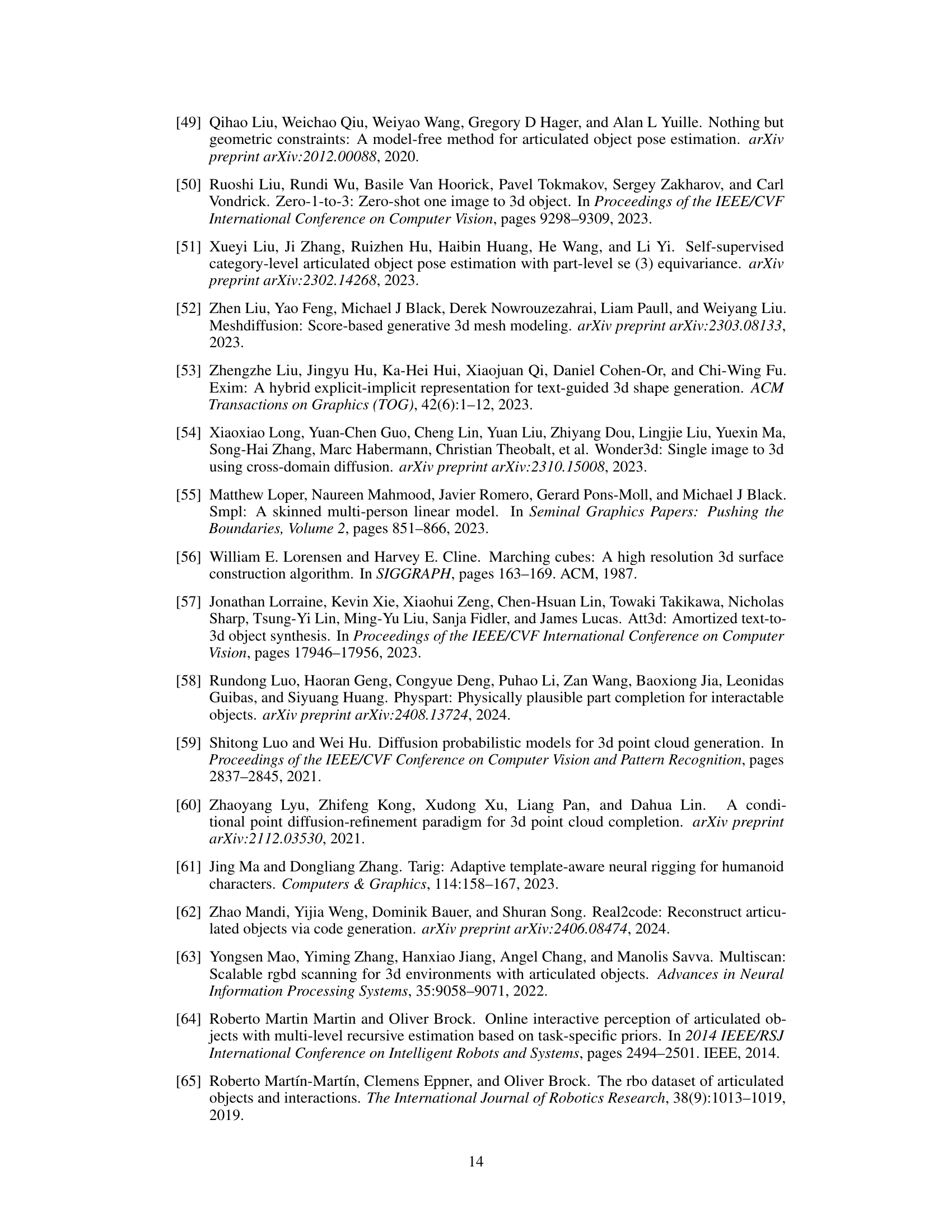

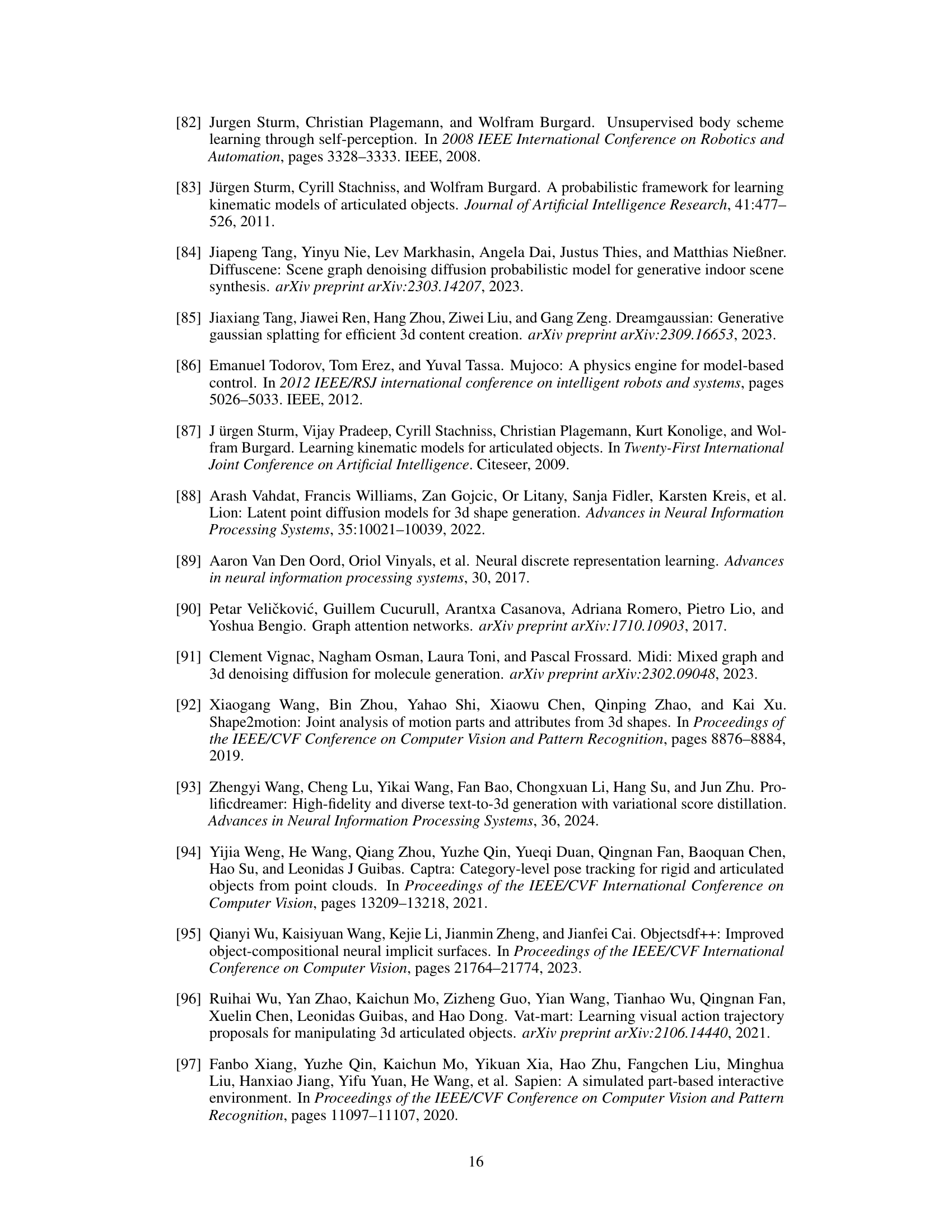

The figure shows the detailed process of the structure generation training pipeline in MIDGARD. It illustrates how an image VQVAE encodes different views of each object part into an 8x8 latent code that is then reshaped into a 64x1 latent vector. These vectors, along with textual descriptions of the parts (e.g., ‘Night Table Body,’ ‘Drawer’) and their joint types (e.g., ‘Revolute,’ ‘Prismatic’), are combined to form the node and edge features of the articulation graph. The graph then serves as input to a Graph Attention Network (GAT) for processing. The entire process aims to generate coherent and interpretable articulation features from noisy or incomplete inputs.

This figure shows the detailed structure generation training pipeline. The input is an articulated asset represented as a graph. Each part of the asset is encoded into an 8x8 latent image using a VQVAE. This latent representation is then concatenated with other relevant features to form a 64x1 latent vector, which is further processed by a Graph Attention Network (GAT). This GAT attempts to predict a clean version of the noisy articulation graph. The figure illustrates the flow of data through the different components (VQVAE, Reshape, GAT, and the Articulation Graph) and their interactions.

This figure illustrates the inference stage of the structure generator in the MIDGARD model. An incomplete articulation graph, representing the object’s structure and joints, is input to a Graph Attention Network (GAT). The GAT processes the input graph and outputs a denoised articulation graph. Latent image codes (8x8) are extracted for each link and then reshaped into 64x1 latent vectors. This denoised graph, along with the latent image codes, provides information for the subsequent shape generation step.

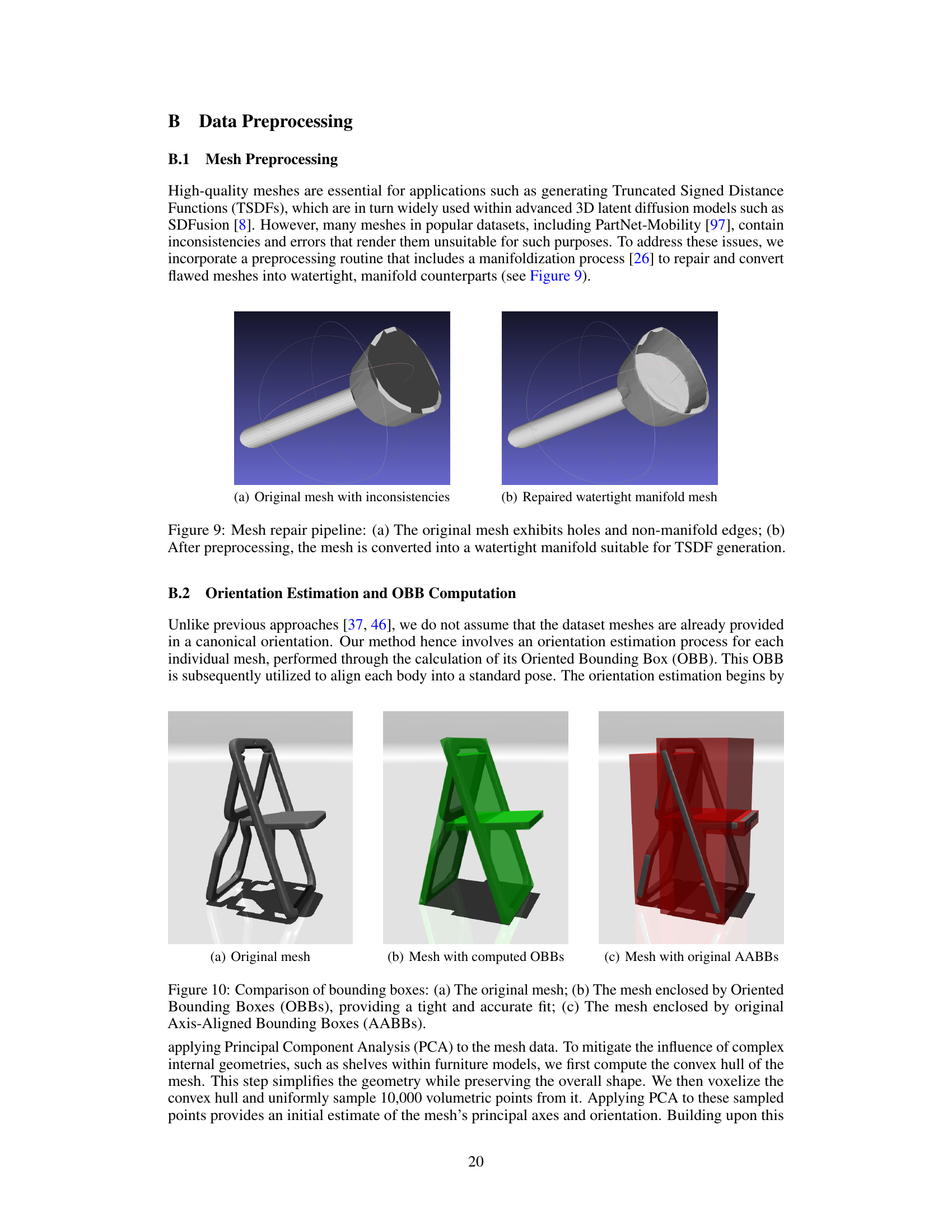

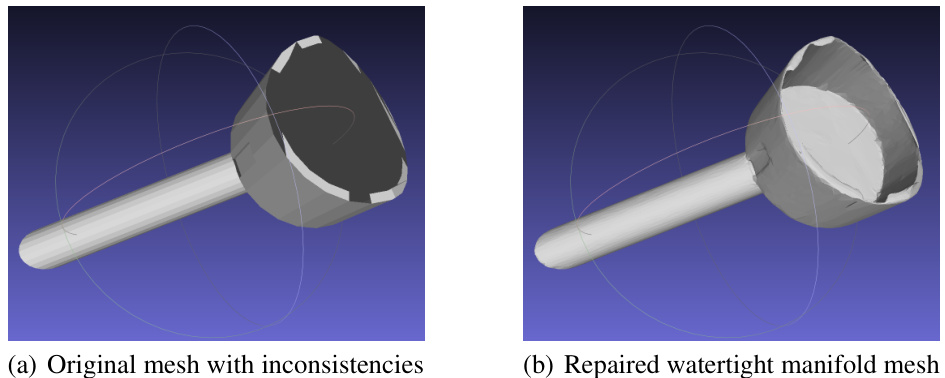

This figure shows the result of the mesh repair pipeline used in the preprocessing step. The original mesh (a) contains holes and non-manifold edges, which are common issues in 3D models. The pipeline processes these issues to create a watertight manifold mesh (b), making it suitable for further processing such as generating a Truncated Signed Distance Function (TSDF), a representation commonly used in 3D generative models.

This figure illustrates the pipeline of the MIDGARD generative model. It starts with a VQVAE (Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoder) which encodes the input images. Then, the decoded images and partial information are processed by the Structure Generator (using GAT, Graph Attention Network) to generate a denoised articulation graph. This denoised graph is further used by the Shape Generator to generate the final articulated asset.

This figure shows an example of an articulated object generated by MIDGARD and simulated within the MuJoCo physics engine. It showcases the successful generation of a teapot, complete with handle and lid, and its ability to be rendered and simulated realistically in a physics environment. The green translucent boxes represent the oriented bounding boxes calculated during the preprocessing stage, indicating proper alignment and size consistency of the generated parts.

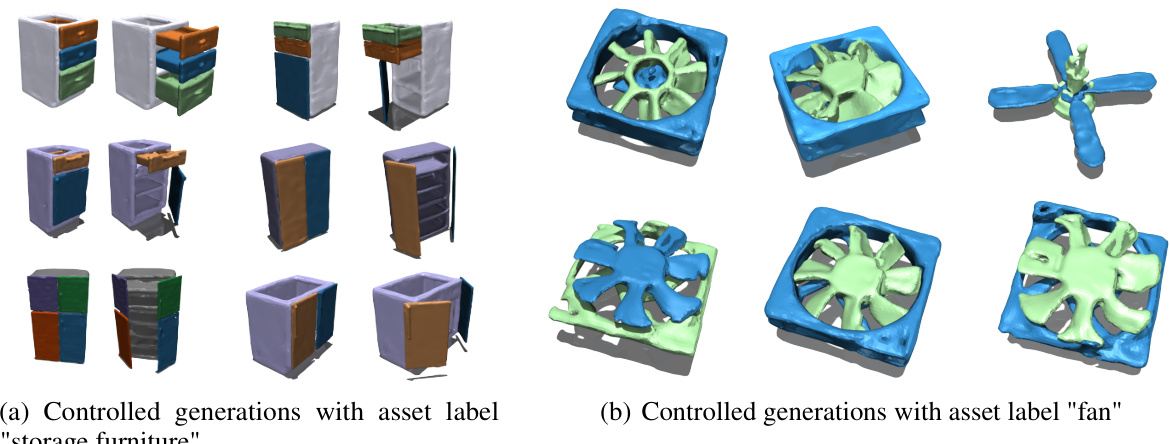

This figure shows examples of 3D articulated objects generated by MIDGARD using only asset-level labels as input. The top row displays various ‘storage furniture’ assets, showcasing differences in overall structure and component arrangement, while the bottom row shows variations of ‘fan’ assets. These examples highlight MIDGARD’s ability to generate diverse and plausible articulated objects based on high-level semantic information alone, demonstrating its controllability and flexibility.

This figure showcases the controllability of MIDGARD’s shape generation module. By changing the input image, the generated part’s appearance changes accordingly. The top row shows examples where replacing the input image successfully changes the appearance of the generated part. The bottom row contrasts this with results from NAP, a previous method, which shows the failure of that method to generate high-quality and realistic parts, particularly when many parts are involved.

More on tables

This table compares the distribution of joint types (Screw, Revolute, Prismatic) in the real training data with the distributions generated by NAP and MIDGARD. It highlights the discrepancy between NAP’s generated data and the real data, showing that NAP heavily overgenerates screw joints. In contrast, MIDGARD’s generated data shows a much closer alignment with the distribution in the real data, indicating better realism and consistency.

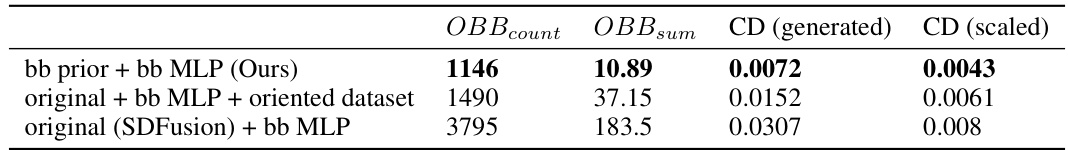

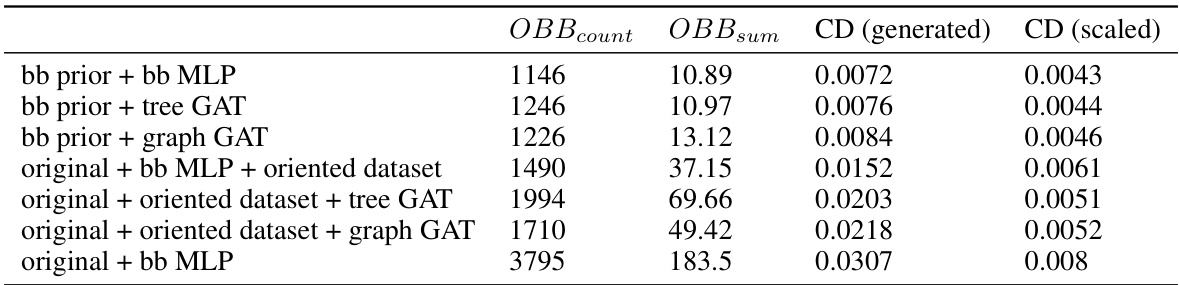

This table presents an ablation study evaluating the effectiveness of the bounding-box constrained shape generation approach. It compares the performance of the original SDFusion model with three modifications: 1) using only the bounding box constraints, 2) adding the pre-processing step of aligning dataset objects to canonical poses, and 3) using the bounding-box prior method. The results are measured using OBBcount, OBBsum, and Chamfer distance (CD) both for generated meshes and meshes that have been post-processed by resizing.

This table presents the ablation study on the effectiveness of using graph attention networks (GATs) for encoding object-level information in the shape generation process. It compares the performance of using an MLP versus a GAT for generating shapes with different graph structures (a tree structure and a complete graph). The evaluation metrics used are OBBcount, OBBsum, and Chamfer distance (CD), both for the generated meshes and for the meshes scaled to fit within a bounding box. The results show that using an MLP significantly outperforms using a GAT for this task.

Full paper#