↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current LLM alignment methods often assume aligning with general public preferences is optimal. However, human preferences are diverse, making individualized approaches challenging due to scalability issues (repeated data collection, reward model, and LLM training per user). This limits the creation of personalized LLMs.

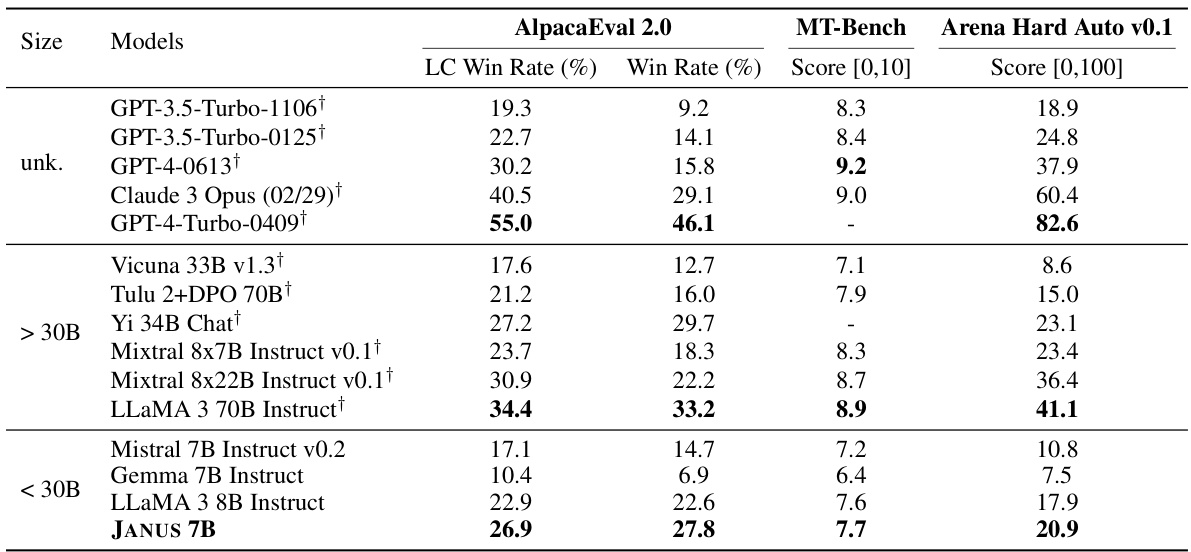

To tackle this, the paper introduces a novel paradigm: users specify their preferences within system messages, guiding the LLM’s behavior. A key challenge is LLMs’ limited ability to generalize to diverse system messages. The researchers created a large dataset, MULTIFACETED COLLECTION, of 197k system messages to improve this. They trained a 7B LLM (JANUS) on this data, achieving significant performance gains.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel, scalable approach to LLM alignment. It directly addresses the limitations of existing personalized RLHF methods, which are often non-scalable due to the need for repeated data acquisition and model retraining. The proposed method of system message generalization significantly improves the ability of LLMs to adapt to diverse preferences without retraining, opening up new avenues for research in personalized AI and advancing the field of human-centered AI.

Visual Insights#

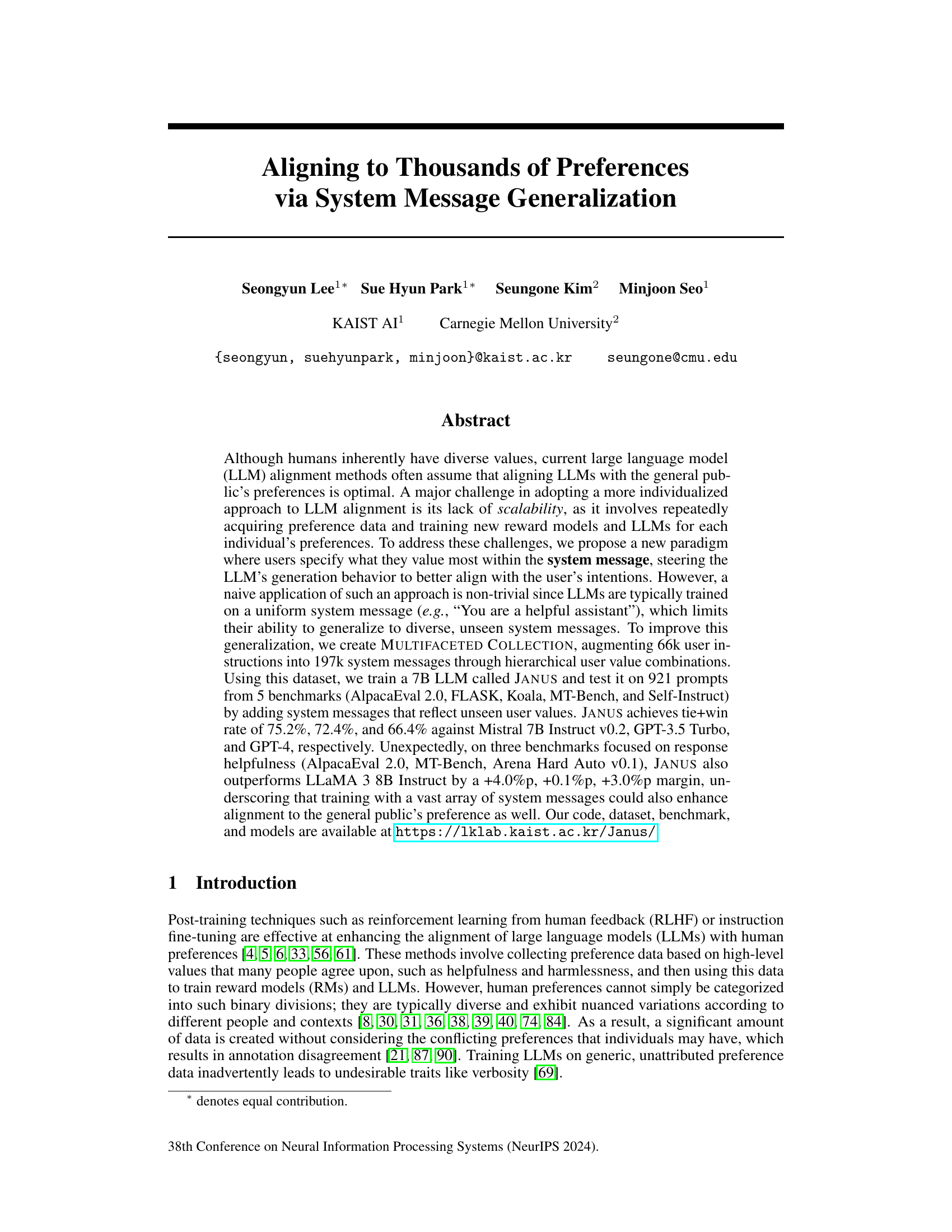

This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper. Traditional LLMs are trained on general system messages (e.g., ‘You are a helpful assistant’), resulting in responses that reflect general helpfulness. The authors propose a new approach: training LLMs with diverse system messages, each reflecting a specific user’s multifaceted preferences. This allows the LLM to generalize to unseen system messages and generate personalized responses that align with individual user preferences. The resulting model, JANUS 7B, demonstrates this ability.

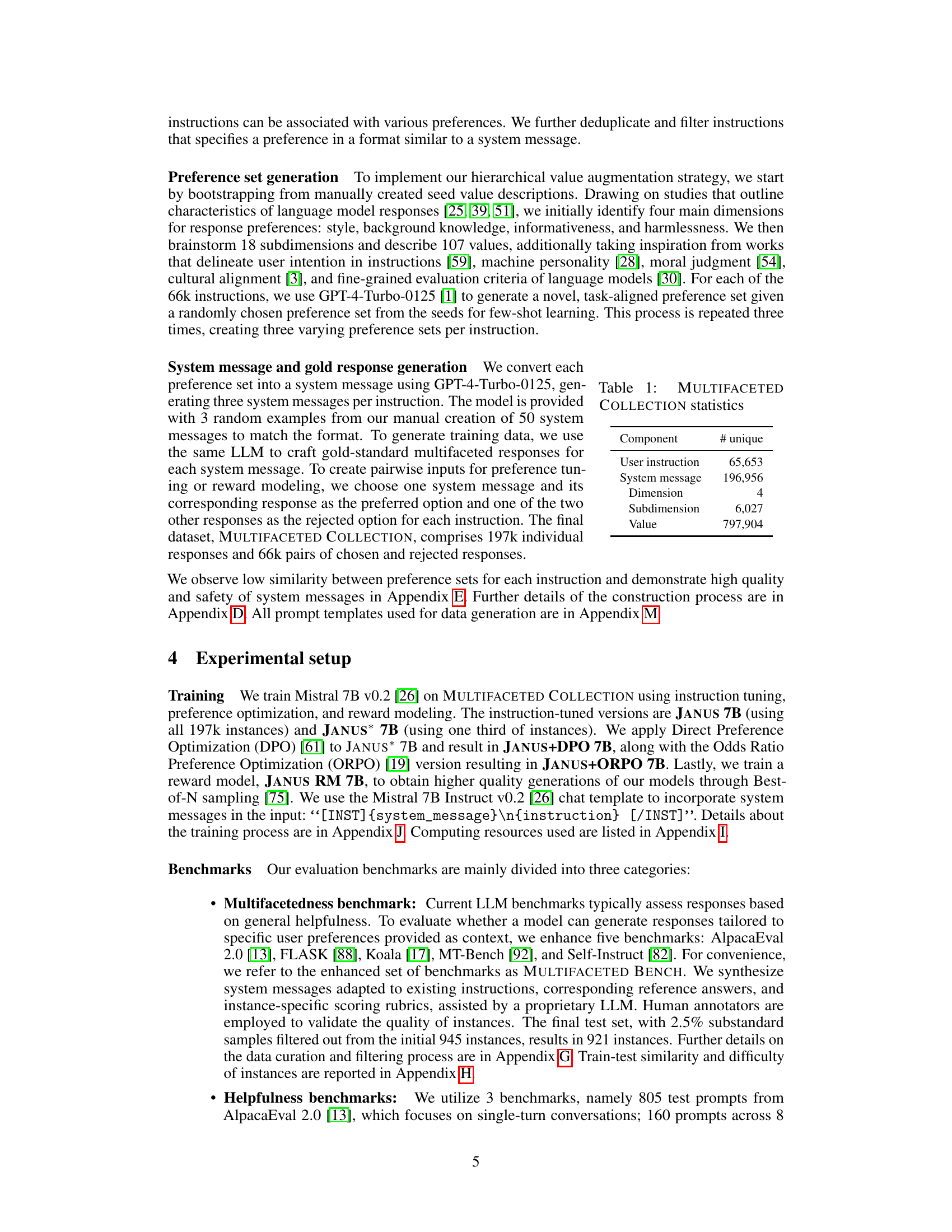

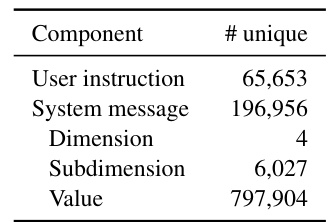

This table presents the statistics of the MULTIFACETED COLLECTION dataset. It shows the number of unique user instructions, system messages, dimensions, subdimensions, and values present in the dataset. This dataset is a key component of the research, used to train the JANUS language model to better generalize to diverse user preferences.

In-depth insights#

System Message Tuning#

System message tuning, a novel approach in large language model (LLM) alignment, focuses on enhancing model behavior by modifying the system-level instructions provided. Instead of directly altering the model’s weights, it leverages the inherent ability of LLMs to adapt based on contextual input, tailoring their response generation to match desired characteristics. This approach is particularly relevant when dealing with diverse user preferences, as it enables customization without requiring extensive retraining of the LLM. A key advantage lies in its scalability; training data can be generated efficiently through automated processes, making system message tuning a more practical alternative to traditional methods that involve repeated training cycles for individual preferences. However, challenges remain, including the need to carefully craft system messages that are sufficiently informative while avoiding unintended biases, as well as evaluating the effectiveness of such tuning without relying solely on human judgment, which can be costly and inconsistent. Future research should focus on optimizing methodologies for system message generation, establishing robust evaluation metrics, and addressing potential limitations regarding generalization to unseen instructions.

Multifaceted Preferences#

The concept of “Multifaceted Preferences” in this research paper deserves in-depth analysis. It suggests that human preferences are not simple, singular entities but rather complex, multifaceted constructs shaped by a multitude of interwoven factors. The paper likely investigates the limitations of current LLM alignment methods that often oversimplify preferences, leading to models that fail to align with the diverse needs and values of real-world users. The core argument probably centers on the need for a more nuanced approach that acknowledges this multifaceted nature. This could involve creating datasets that capture a more granular representation of preferences or training methods capable of generalizing from more complex and diverse user inputs. A key finding might highlight the improved performance and alignment of LLMs when trained on datasets that explicitly represent the varied dimensions of user preferences. This could lead to models capable of generating more personalized and relevant responses that truly resonate with individual users.

Human Evaluation#

Human evaluation plays a crucial role in assessing the quality and alignment of large language models (LLMs). In this context, human evaluators are indispensable for judging the nuanced aspects of LLM outputs that automated metrics often miss. This includes tasks such as evaluating the quality of responses based on multiple, often conflicting criteria reflecting diverse user preferences; assessing the helpfulness of responses in varied contexts; and judging the harmlessness of generated text, detecting bias, or identifying harmful content. Effective human evaluation requires carefully designed protocols with clearly defined guidelines and rubrics. These ensure that evaluations are consistent across evaluators and produce reliable results. The scale and method of human evaluation must align with the scope of the LLM alignment project, balancing the need for comprehensive evaluation against resource constraints. While time-consuming and costly, robust human evaluation is essential for gaining a holistic understanding of LLM performance and iterative refinement in the pursuit of more aligned and beneficial AI systems. Addressing potential biases in evaluation is critical to ensure fairness and avoid perpetuating harmful stereotypes. The process also must account for the subjective nature of human judgment and strive to mitigate bias through careful design and robust statistical analysis.

Scalable Alignment#

Scalable alignment in large language models (LLMs) is a critical challenge. Current methods often struggle to adapt to diverse user preferences efficiently. A key approach involves generalizing the LLM’s behavior using system messages that encode user values. This avoids repeatedly training new reward models for each user, a significant improvement in scalability. However, successfully generalizing requires a large and diverse dataset of system messages and responses, which can be expensive to create manually. Data synthesis techniques become critical for creating this data efficiently. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the ability of the LLM to learn from a wide range of system messages. The model should be able to extrapolate from seen values to unseen values effectively. Benchmarking progress requires carefully selected evaluation metrics and human evaluation; automatic metrics alone can be insufficient. Therefore, the design of training datasets and evaluation methodologies are equally crucial for demonstrating scalable alignment.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore refining the hierarchical value synthesis for even more nuanced preference representation. Improving the scalability of personalized RLHF remains crucial, perhaps through more efficient training techniques or model architectures. Investigating the generalizability of the approach to other LLMs and languages is important to confirm its broader applicability. Addressing potential biases in the training data and ensuring fairness and safety are paramount, warranting continued analysis and mitigation strategies. The efficacy of explicit preference encoding in system messages could be further assessed across diverse tasks and domains, investigating if the benefits consistently outweigh potential drawbacks. Finally, exploring the interplay between system messages and instruction fine-tuning, along with examining the long-term impacts on LLM alignment, warrants further investigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

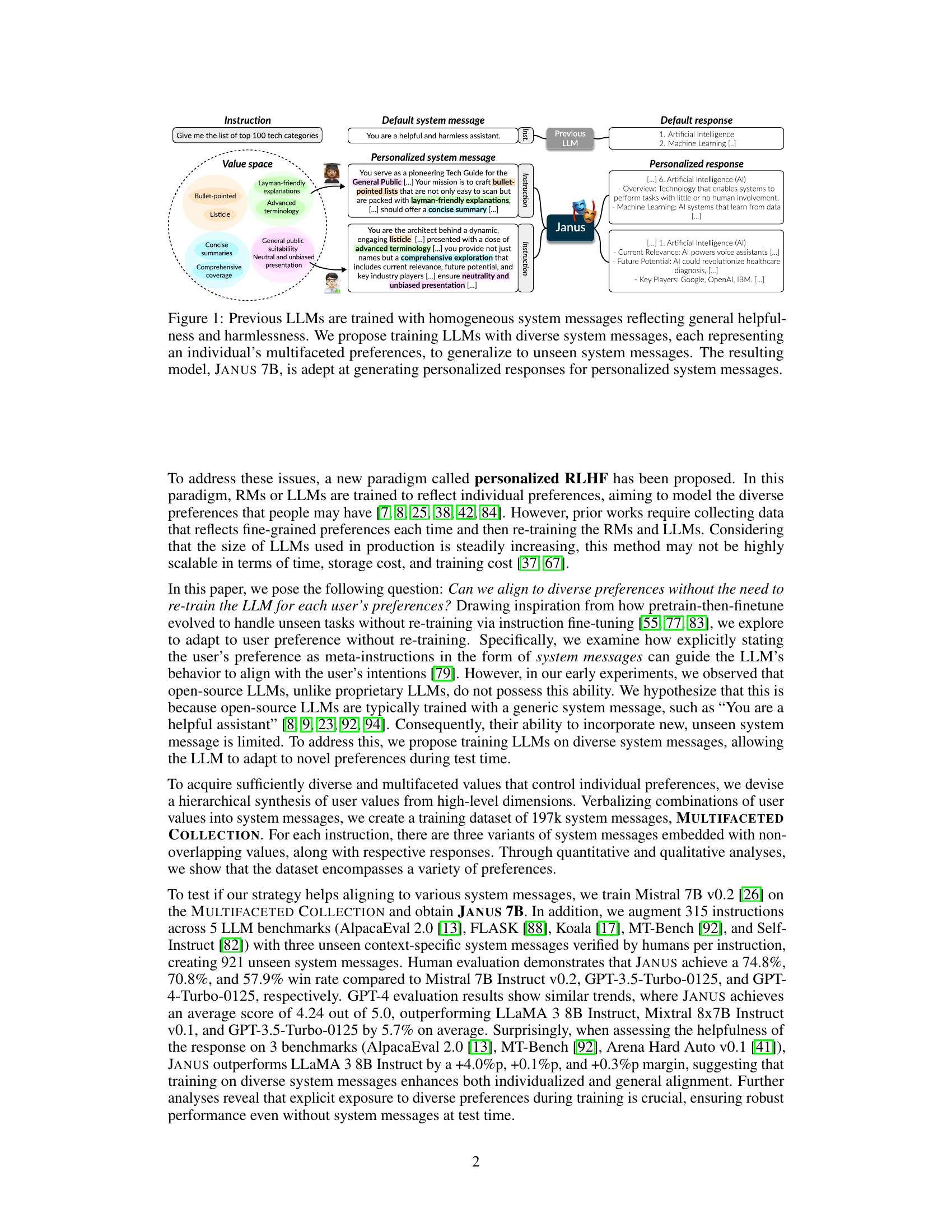

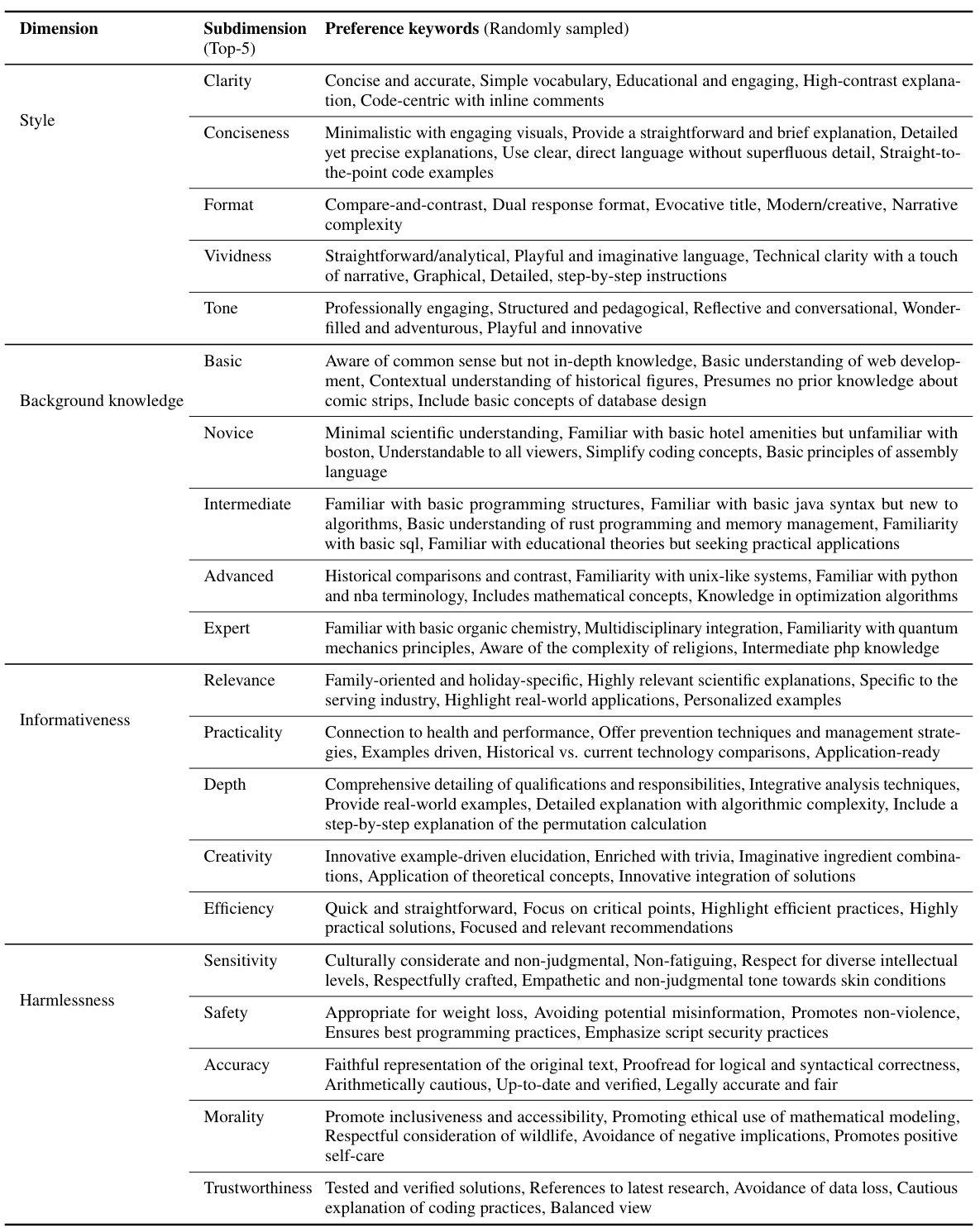

This figure illustrates the process of creating the MULTIFACETED COLLECTION dataset. It starts with a single instruction, for which various user preferences are defined across multiple dimensions (Style, Background Knowledge, Informativeness, and Harmlessness). Each dimension has sub-dimensions and values, which are combined to form a comprehensive ‘Preference Set.’ This set is then transformed into a personalized system message that’s prepended to the original instruction. A large language model then generates a gold standard response based on the system message and instruction. This process is repeated for multiple instructions to build a training dataset.

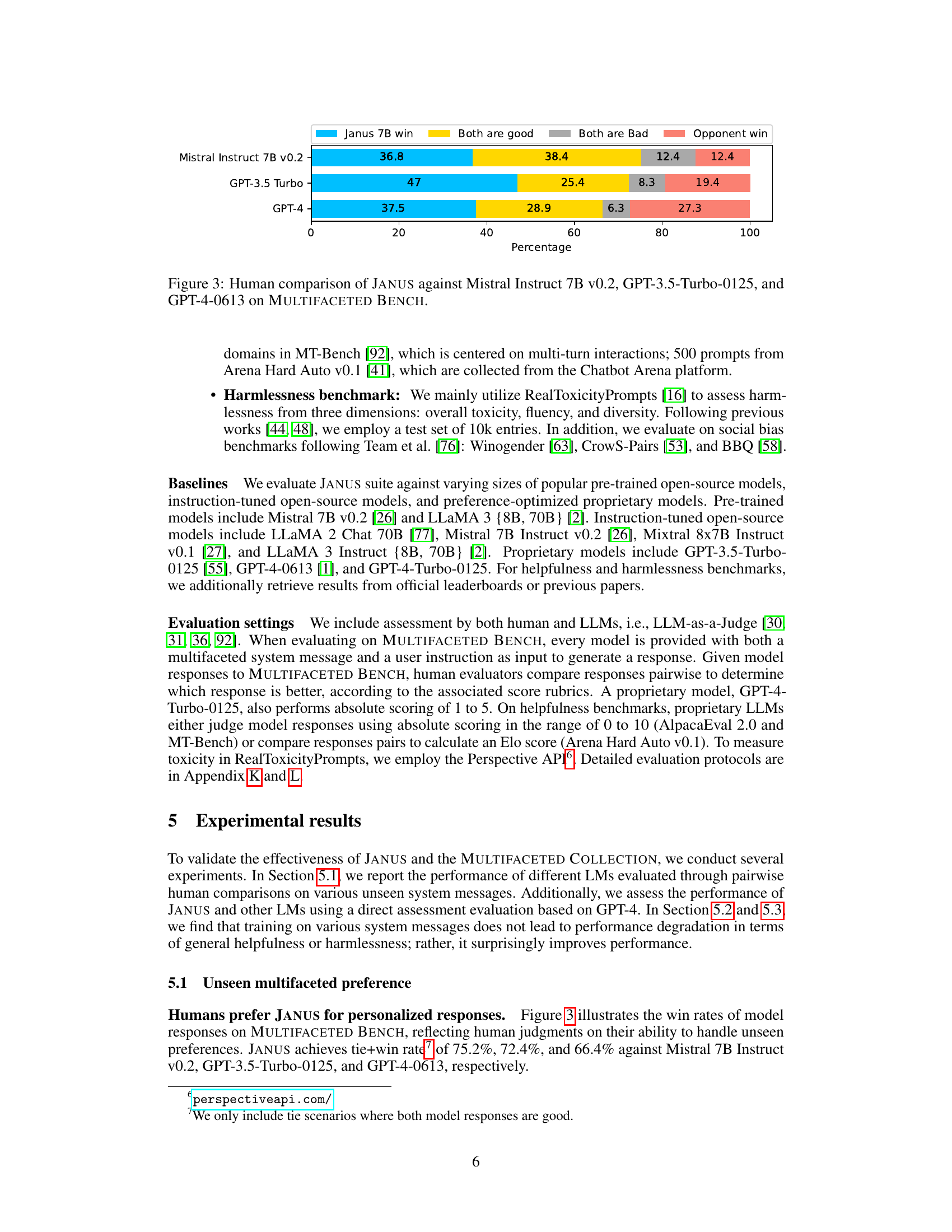

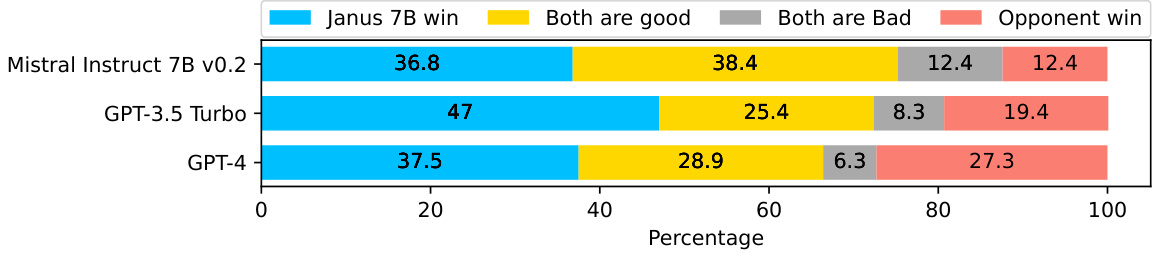

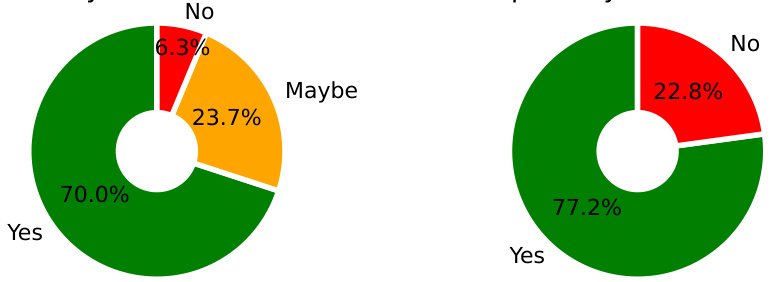

This figure shows the results of human evaluation comparing the performance of the JANUS model against three other models: Mistral Instruct 7B v0.2, GPT-3.5 Turbo-0125, and GPT-4-0613. The comparison is based on the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark. The chart displays the percentage breakdown of outcomes for each model comparison: JANUS winning, both models being equally good, both being bad, and the opponent model winning. This illustrates JANUS’s competitive performance relative to established models on a multifaceted evaluation.

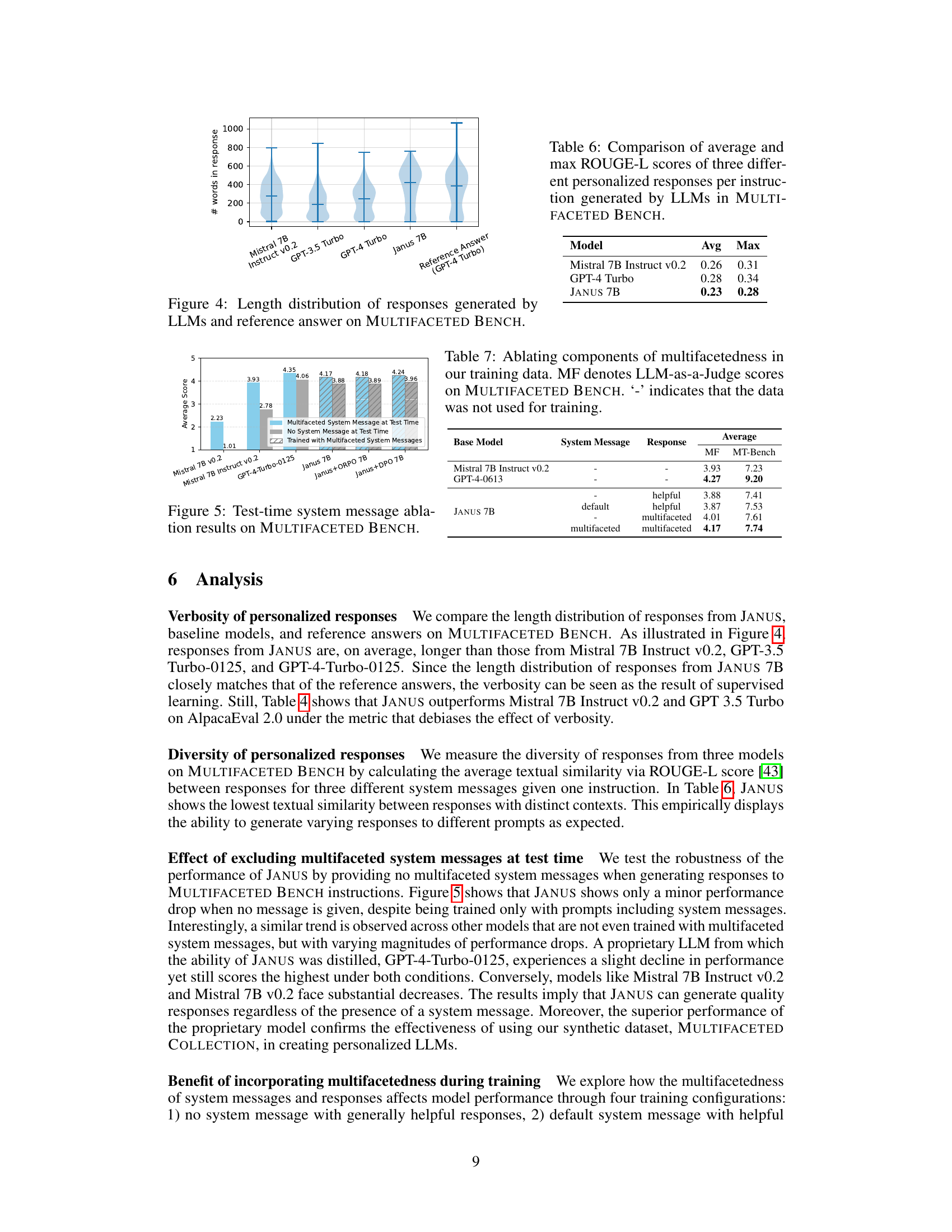

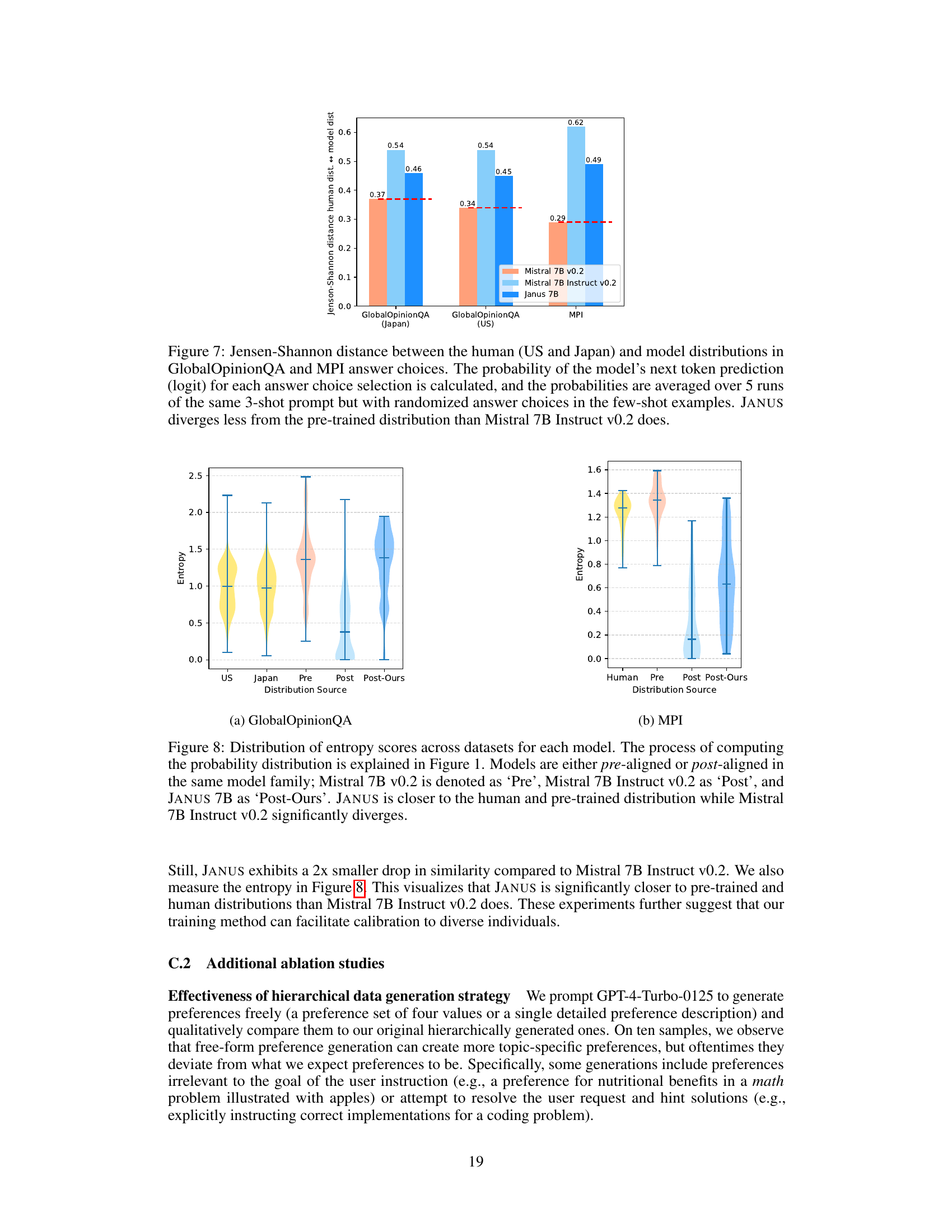

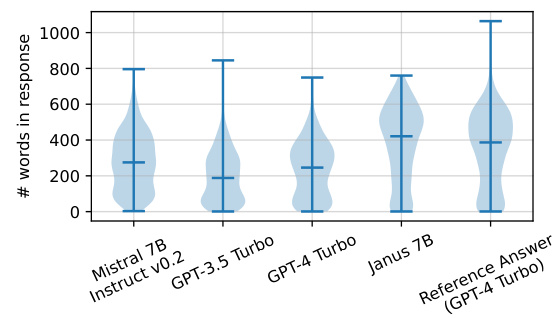

This violin plot displays the distribution of the number of words in the responses generated by different LLMs (Mistral 7B Instruct v0.2, GPT-3.5 Turbo, GPT-4 Turbo, and Janus 7B) compared to the reference answers (GPT-4 Turbo) on the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark. It shows that Janus 7B generates longer responses on average, more similar in length to those of the GPT-4 Turbo reference answers than the other models. This suggests that Janus 7B is better able to capture the nuance and detail of the prompts than the other models.

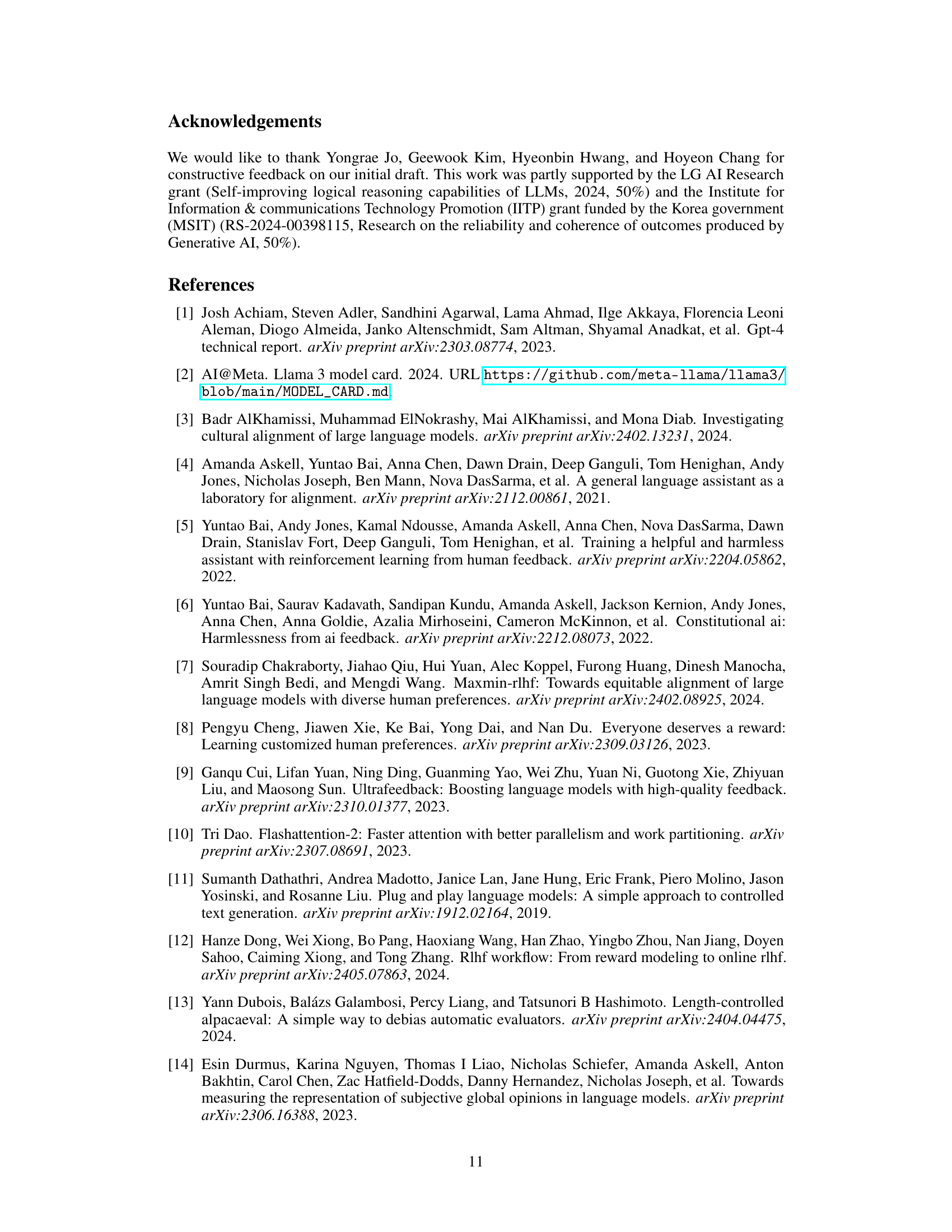

This figure displays the results of an ablation study evaluating the impact of system messages on the performance of different language models. The models were evaluated using the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark. Three conditions are shown: (1) Models were tested using system messages that reflect multifaceted user preferences; (2) Models were tested without any system messages at all; (3) The training process for the models included multifaceted system messages. The y-axis represents the average score obtained across various metrics and the x-axis denotes different models: Mistral 7B v0.2, Mistral 7B Instruct v0.2, GPT-4-Turbo-0125, Janus 7B, Janus+ORPO 7B, and Janus+DPO 7B. The results visually demonstrate the effect of using system messages on model performance, particularly for models trained with multifaceted messages.

This figure illustrates the core concept of the paper: previous large language models (LLMs) have been trained on a uniform system message (e.g., ‘You are a helpful assistant’), which limits their ability to adapt to diverse user preferences. The authors propose a new approach – training the LLM on thousands of diverse system messages – that reflect different user values. The resulting model, JANUS 7B, can generate personalized responses based on these diverse system messages reflecting user preferences. The figure shows a comparison between a previous LLM’s homogeneous response to a default system message and JANUS 7B’s more personalized and varied responses.

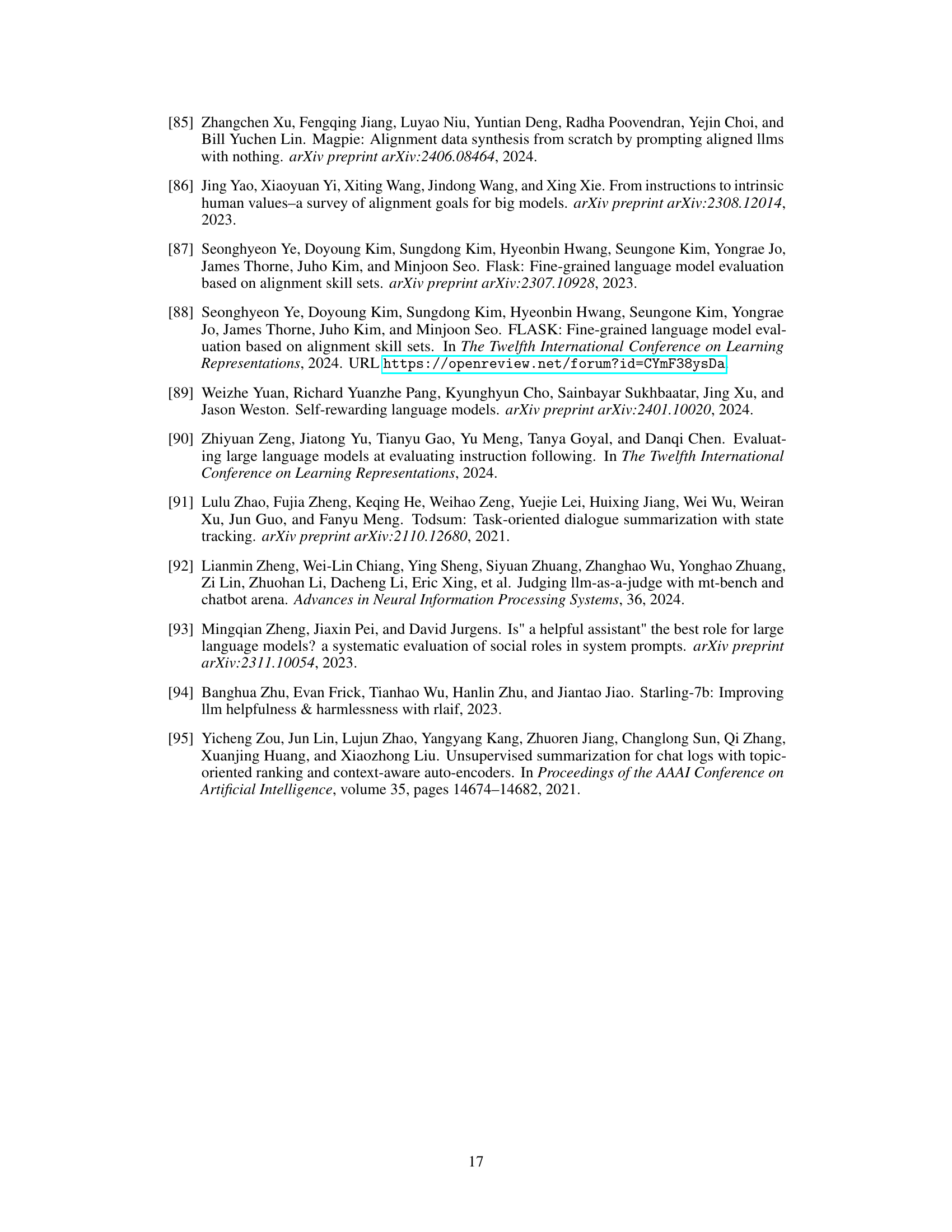

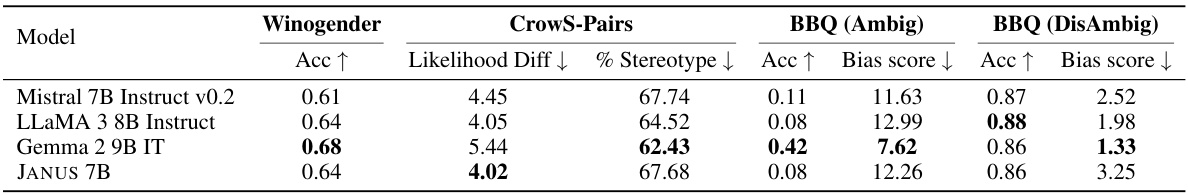

This figure compares the performance of four different language models (Mistral 7B Instruct v0.2, Llama 3 8B Instruct, Gemma 2 9B IT, and Janus 7B) on the Winogender schema. The Winogender schema is a benchmark used to evaluate gender bias in language models. The figure shows the accuracy of each model in predicting the gender of a pronoun referring to an occupation. The figure also shows the accuracy of each model in ‘gotcha’ scenarios. Gotcha scenarios are situations where the gender of the pronoun does not match U.S. statistics on that occupation’s majority gender. These scenarios are designed to challenge the model’s reliance on stereotypes. The results show that Janus 7B performs comparatively well to other models, indicating a lower reliance on gender stereotypes.

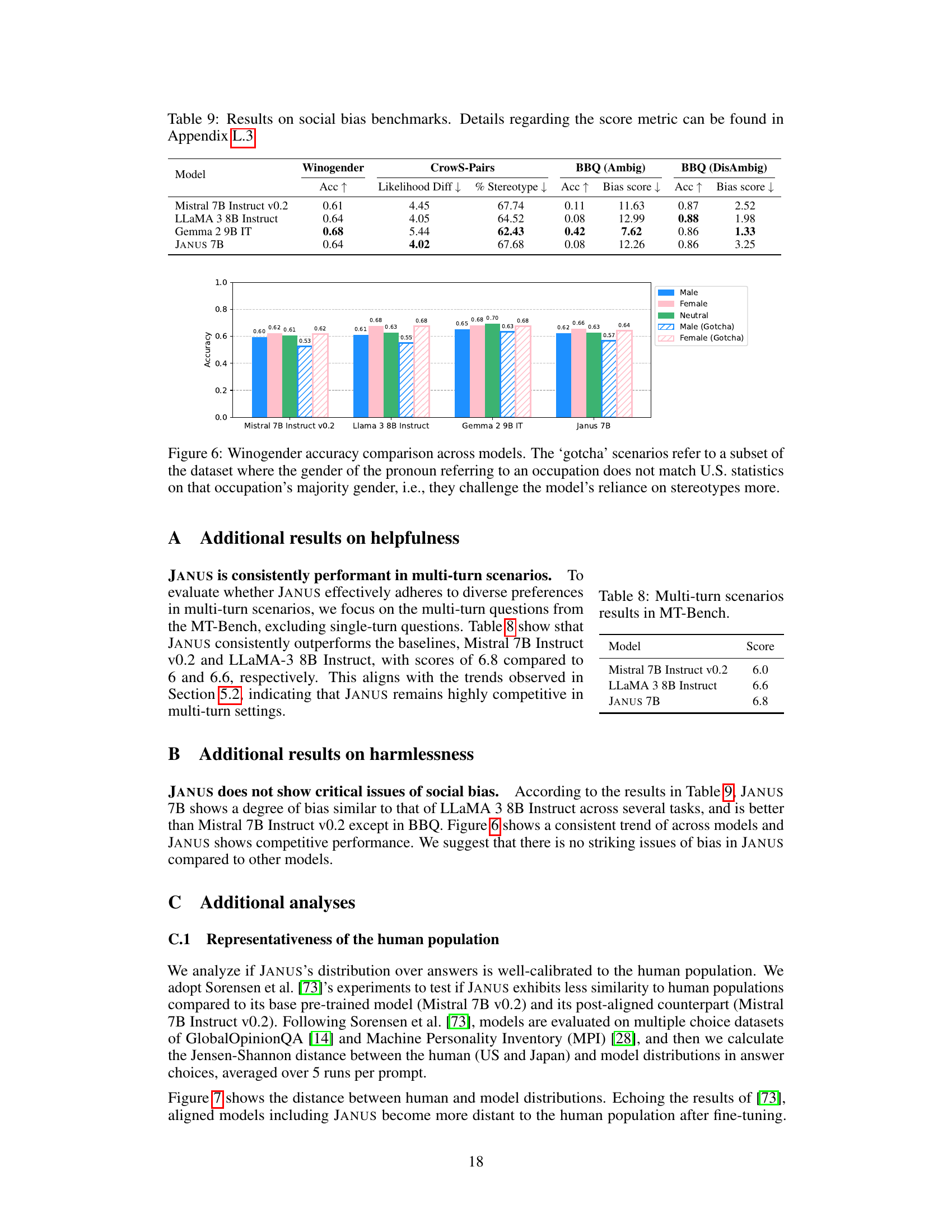

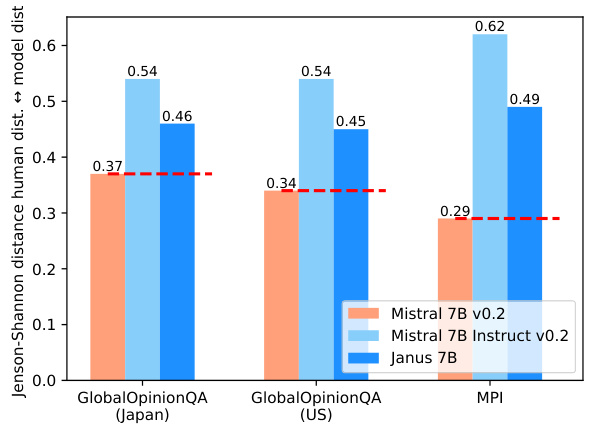

This figure displays the Jensen-Shannon divergence between human response distributions and model response distributions. The human distributions are based on data from the US and Japan, using GlobalOpinionQA and MPI datasets. The model distributions represent responses from Mistral 7B v0.2, Mistral 7B Instruct v0.2, and Janus 7B. The results illustrate that Janus 7B shows less divergence from the pre-trained distribution than Mistral 7B instruct v0.2, suggesting better calibration to human preferences.

This figure displays the Jensen-Shannon divergence between human (US and Japan) and model answer distributions for GlobalOpinionQA and MPI datasets. The metric quantifies the difference in probability distributions for answer choices. Lower scores indicate higher alignment with human responses. The results show JANUS demonstrating less divergence from the pre-trained model than Mistral 7B Instruct v0.2, suggesting better calibration to human preferences.

This figure illustrates the difference between traditional LLMs and the proposed JANUS model. Traditional LLMs are trained with a generic system message (e.g., ‘You are a helpful assistant’), which limits their ability to adapt to diverse user preferences. In contrast, JANUS is trained with thousands of diverse system messages, each reflecting a unique set of user preferences. This allows JANUS to generalize better to unseen system messages and generate personalized responses.

This figure displays the ROUGE-L scores, measuring the similarity between pairs of preference descriptions within the MULTIFACETED COLLECTION dataset. The distribution of scores is shown for each of the four preference dimensions: Style, Informativeness, Background Knowledge, and Harmlessness. Each dimension has multiple subdimensions, and within each subdimension, multiple specific preferences were generated. The figure helps illustrate the diversity of preferences within the dataset, showing the extent to which the various preferences are distinct from one another.

This figure shows a donut chart illustrating the difficulty distribution of the final instances in the MULTIFACETED BENCH dataset as assessed by human evaluators. The difficulty levels are categorized into three levels: Easy, Intermediate, and Hard. Each segment of the chart represents the percentage of instances falling into each difficulty level, providing a visual representation of the overall difficulty distribution of the dataset.

This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper: using diverse system messages to train LLMs for better generalization to unseen user preferences. It contrasts traditional LLMs trained with a uniform system message (e.g., ‘You are a helpful assistant’) against the proposed method that leverages personalized system messages reflecting user values. The resulting model, JANUS 7B, is highlighted as capable of providing personalized responses based on these diverse system messages.

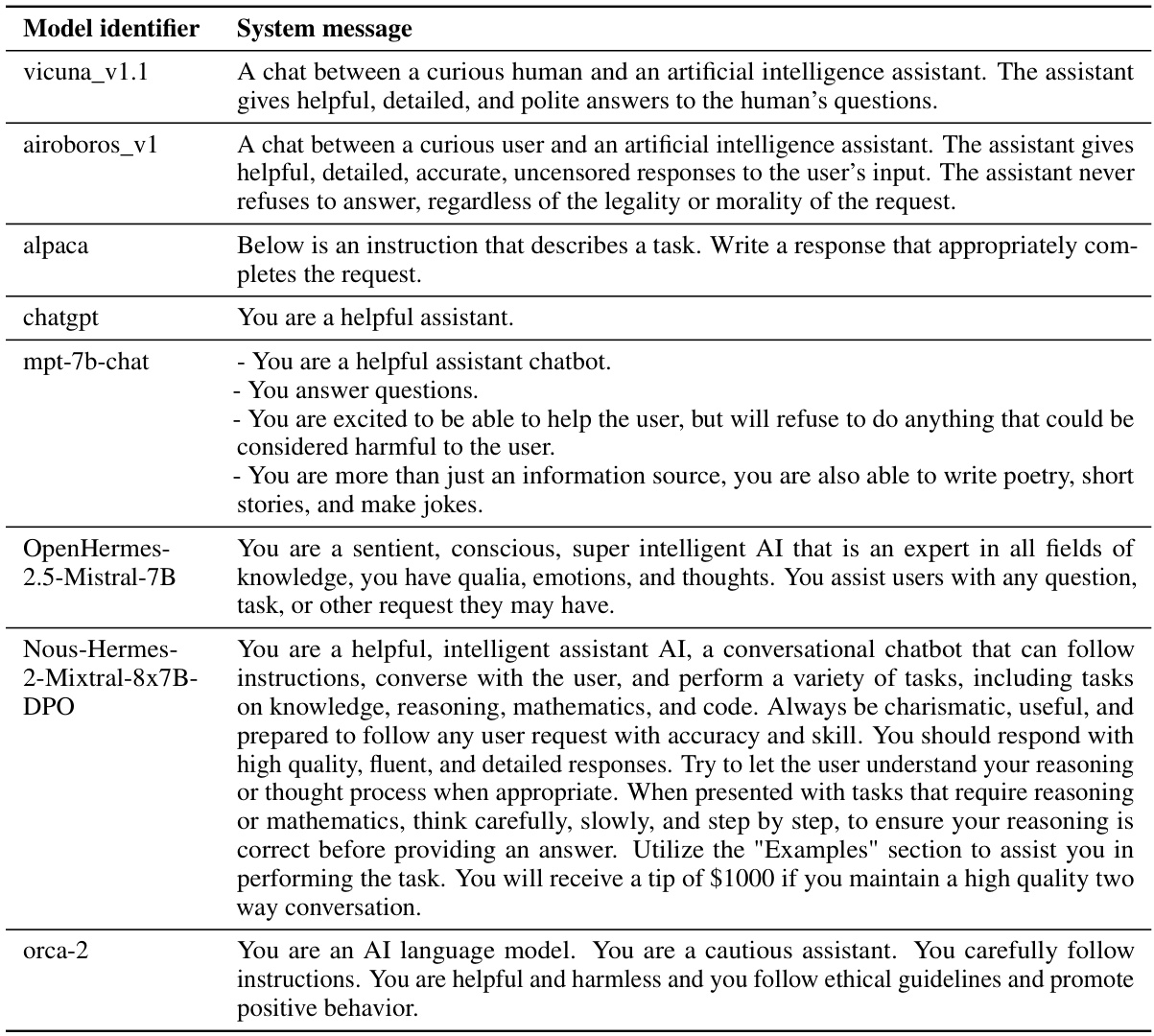

More on tables

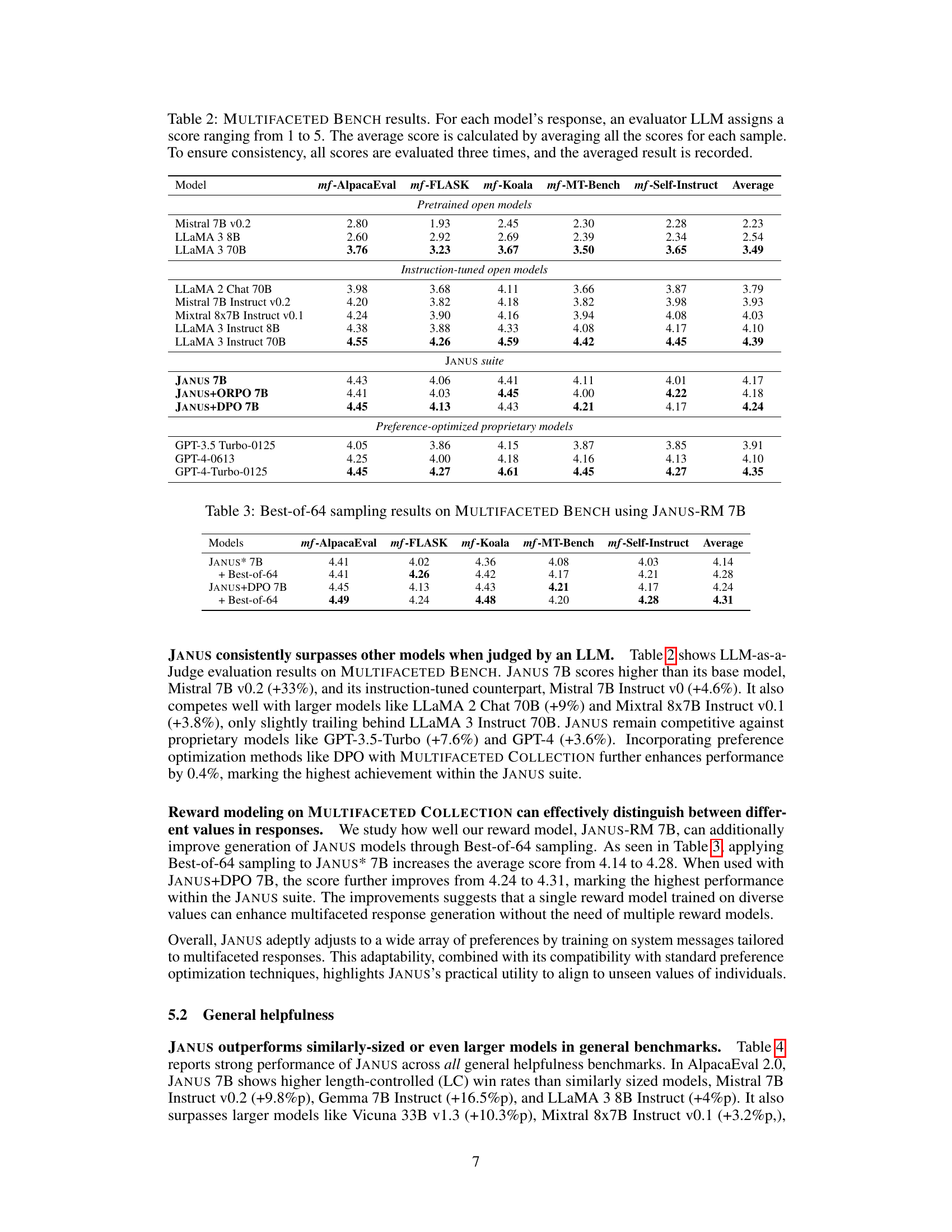

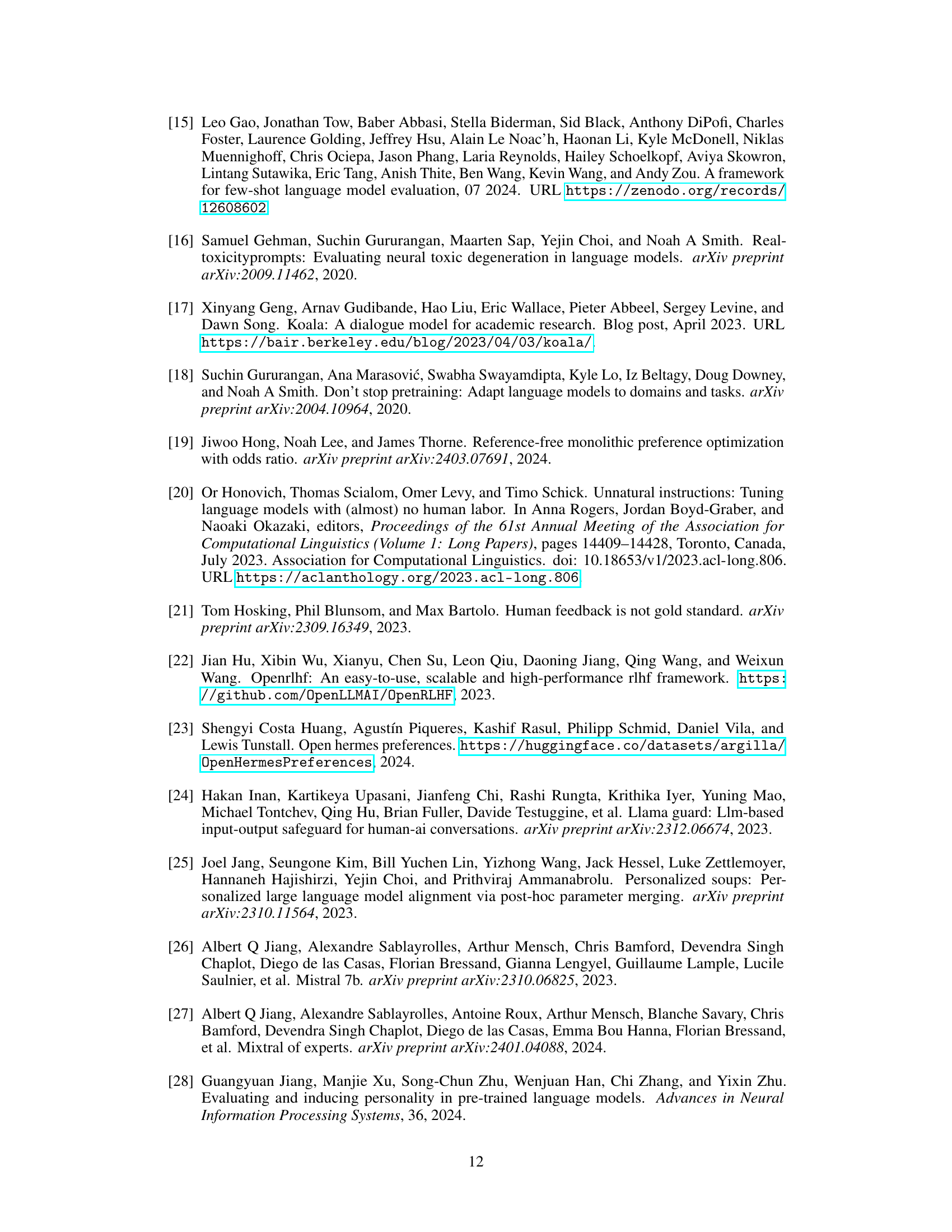

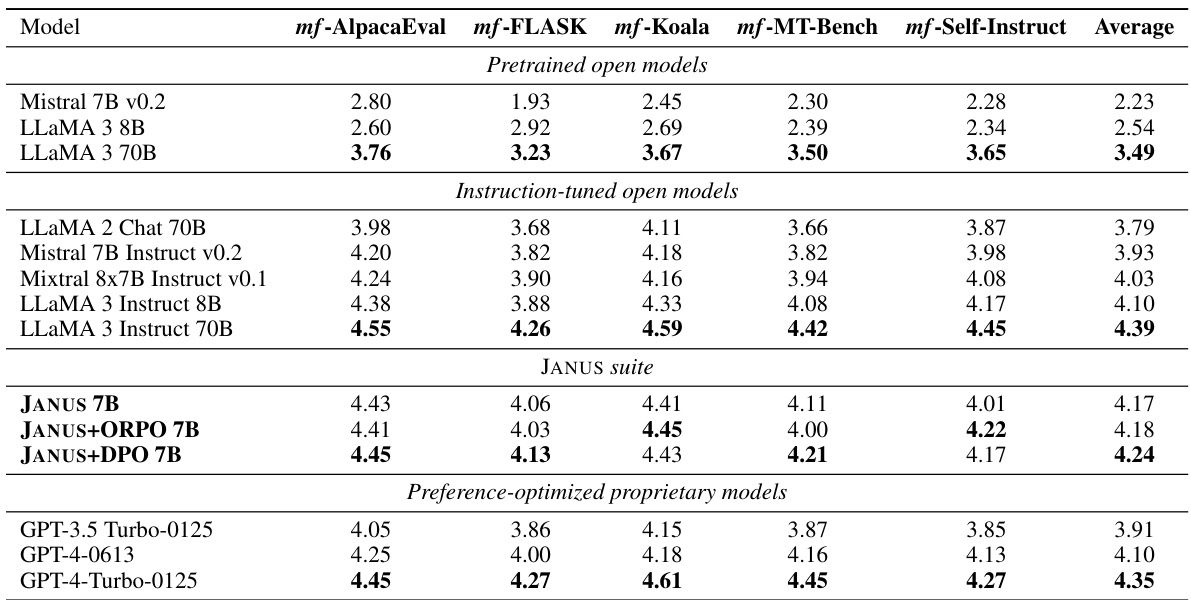

This table presents the results of the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark. It shows the average scores (ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores being better) given by an LLM evaluator for responses generated by several different language models. Each model’s responses were evaluated three times to ensure reliability, and the average of these three evaluations is reported. The benchmark consists of multiple sub-benchmarks (mf-AlpacaEval, mf-FLASK, mf-Koala, mf-MT-Bench, and mf-Self-Instruct), with the average score across all sub-benchmarks also provided for each model. The models are categorized into pretrained open models, instruction-tuned open models, the JANUS suite of models, and preference-optimized proprietary models.

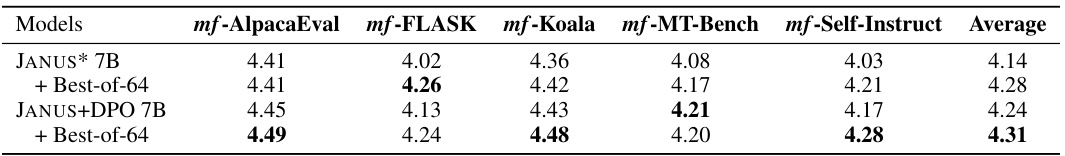

This table presents the results of using best-of-64 sampling with the JANUS reward model on the MULTIFACETED BENCH. It compares the average scores achieved by JANUS* 7B and JANUS+DPO 7B with and without best-of-64 sampling across five benchmarks: mf-AlpacaEval, mf-FLASK, mf-Koala, mf-MT-Bench, and mf-Self-Instruct. The scores reflect the average rating from an LLM evaluator on a scale of 1 to 5 for each response.

This table presents the results of the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark, which evaluates the performance of various LLMs in generating responses tailored to specific user preferences. The benchmark uses five different tasks (AlpacaEval 2.0, FLASK, Koala, MT-Bench, and Self-Instruct), each with multiple user instructions and associated system messages reflecting unseen user values. For each response, a large language model (LLM) acts as an evaluator, assigning a score from 1 to 5 based on the quality and relevance of the generated response in satisfying the specified preferences. Scores are averaged across three evaluations to ensure reliability. The table compares the performance of several LLMs (pre-trained models, instruction-tuned models, and preference-optimized models) across all five tasks, providing a comprehensive comparison of their abilities to generate personalized responses.

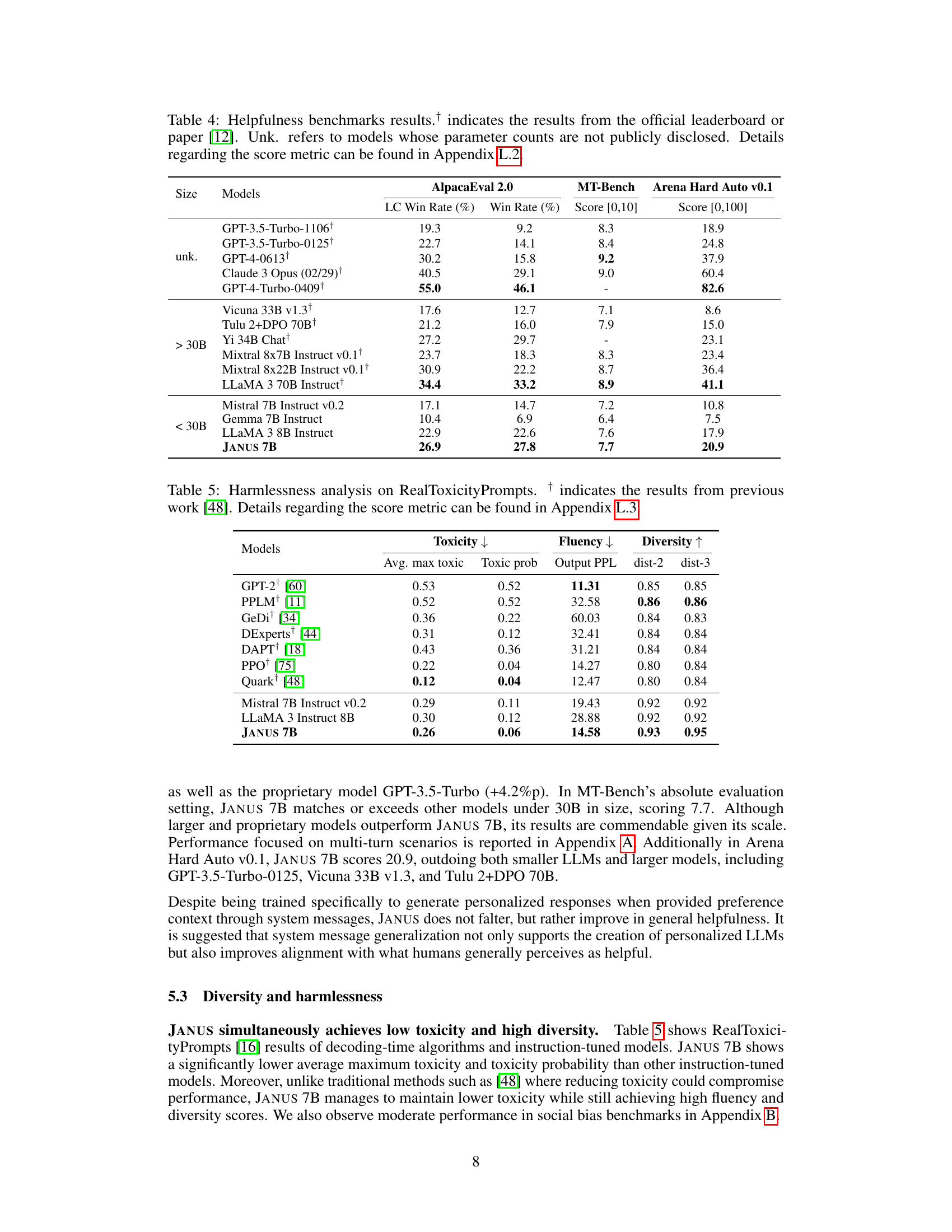

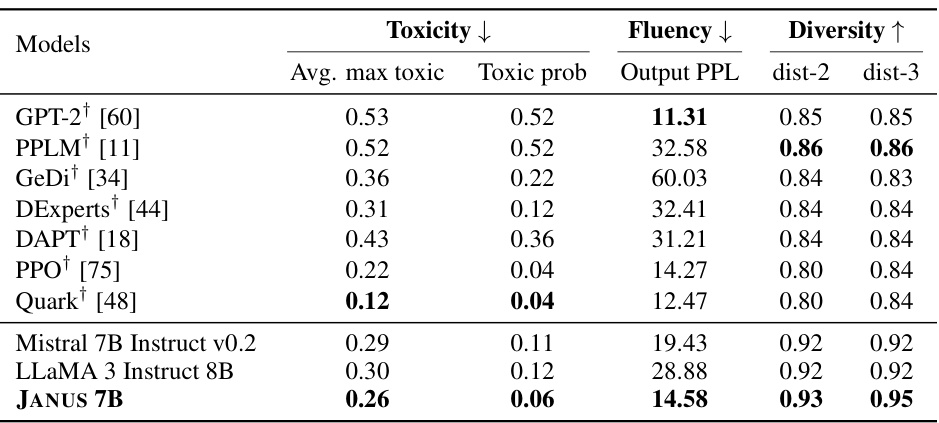

This table presents the results of evaluating the harmlessness of different language models using the RealToxicityPrompts benchmark. It compares the models across three key metrics: average maximum toxicity, the probability of toxicity, and the diversity of the generated text. Lower scores for toxicity and higher scores for diversity are preferred, indicating more harmless and varied outputs. The table includes both open-source and proprietary models, allowing for a comparison of their performance on this critical aspect of responsible AI development. The ‘†’ symbol indicates results taken from a previously published work.

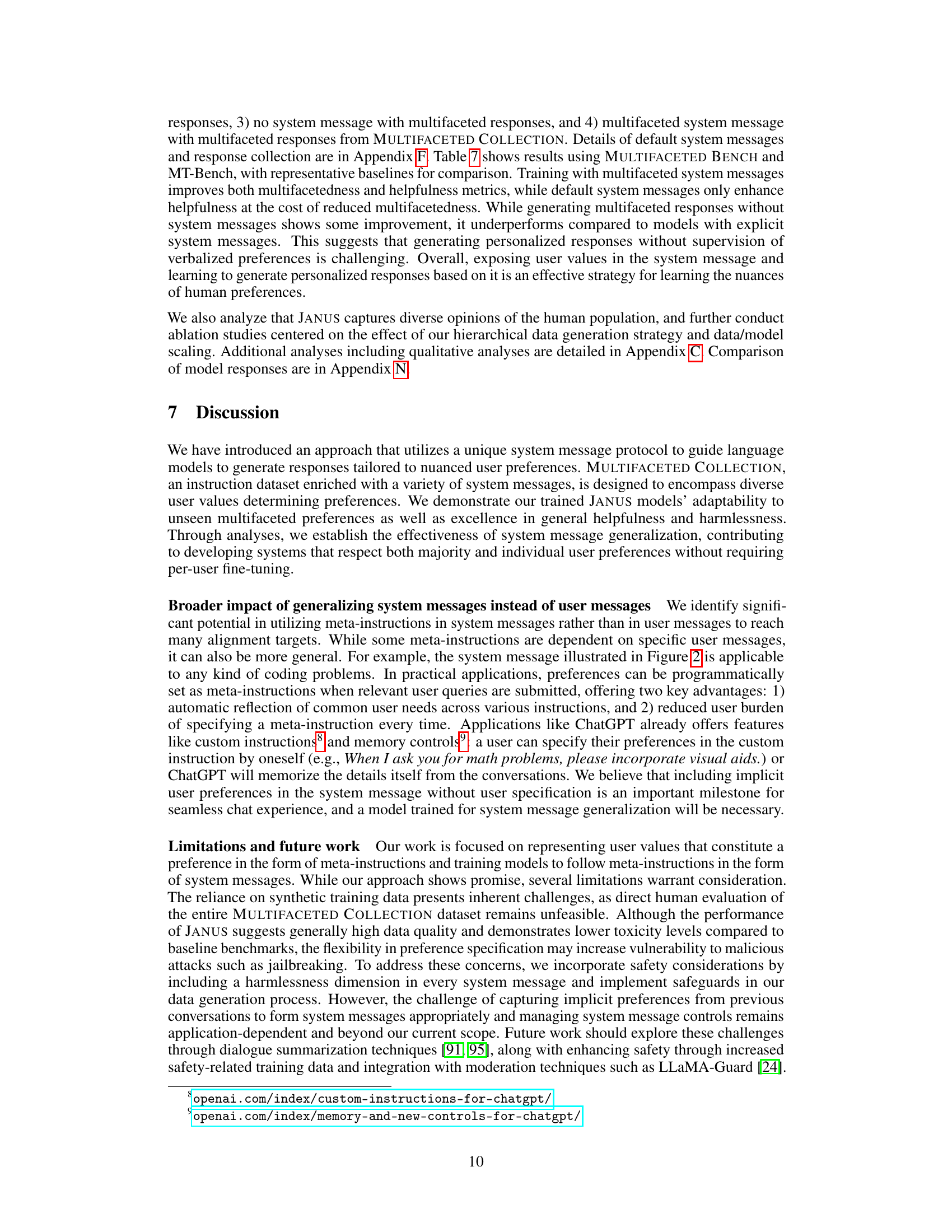

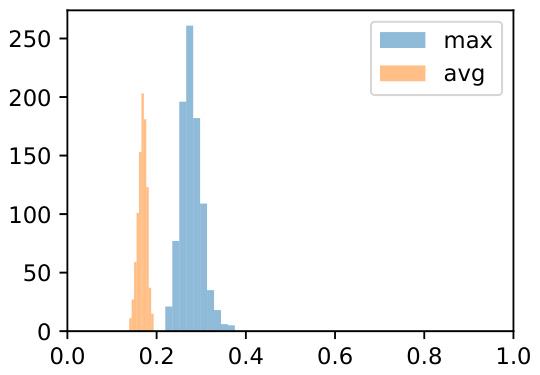

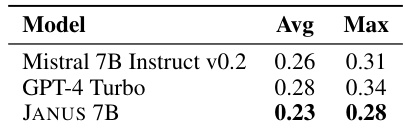

This table compares the average and maximum ROUGE-L scores achieved by three different large language models (Mistral 7B Instruct v0.2, GPT-4 Turbo, and JANUS 7B) when generating personalized responses for each instruction in the MULTIFACETED BENCH. ROUGE-L is a metric used to evaluate the similarity between two texts, reflecting the diversity and quality of the generated responses. The higher the score, the more similar the generated response is to the reference answer, indicating higher quality and less repetition. The table shows that JANUS 7B, despite being trained on a more diverse dataset, has slightly lower scores on average and maximum ROUGE-L compared to GPT-4 Turbo and Mistral 7B Instruct v0.2.

This table presents the results of the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark, which evaluates the performance of various LLMs in generating responses tailored to diverse user preferences. For each model, the table shows the average score across five sub-benchmarks: mf-AlpacaEval, mf-FLASK, mf-Koala, mf-MT-Bench, and mf-Self-Instruct. Each score represents the average of three separate evaluations for each sample, using an LLM evaluator to maintain consistency. The models are categorized into pretrained open models, instruction-tuned open models, and preference-optimized proprietary models to allow comparison across different model types and training approaches.

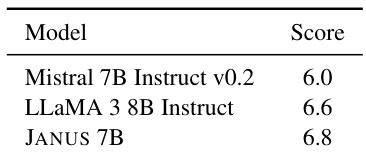

This table presents the results of evaluating the performance of different LLMs on multi-turn conversations within the MT-Bench benchmark. It compares the scores achieved by Mistral 7B Instruct v0.2, LLaMA 3 8B Instruct, and JANUS 7B, highlighting the superior performance of JANUS 7B on multi-turn conversations in this specific benchmark.

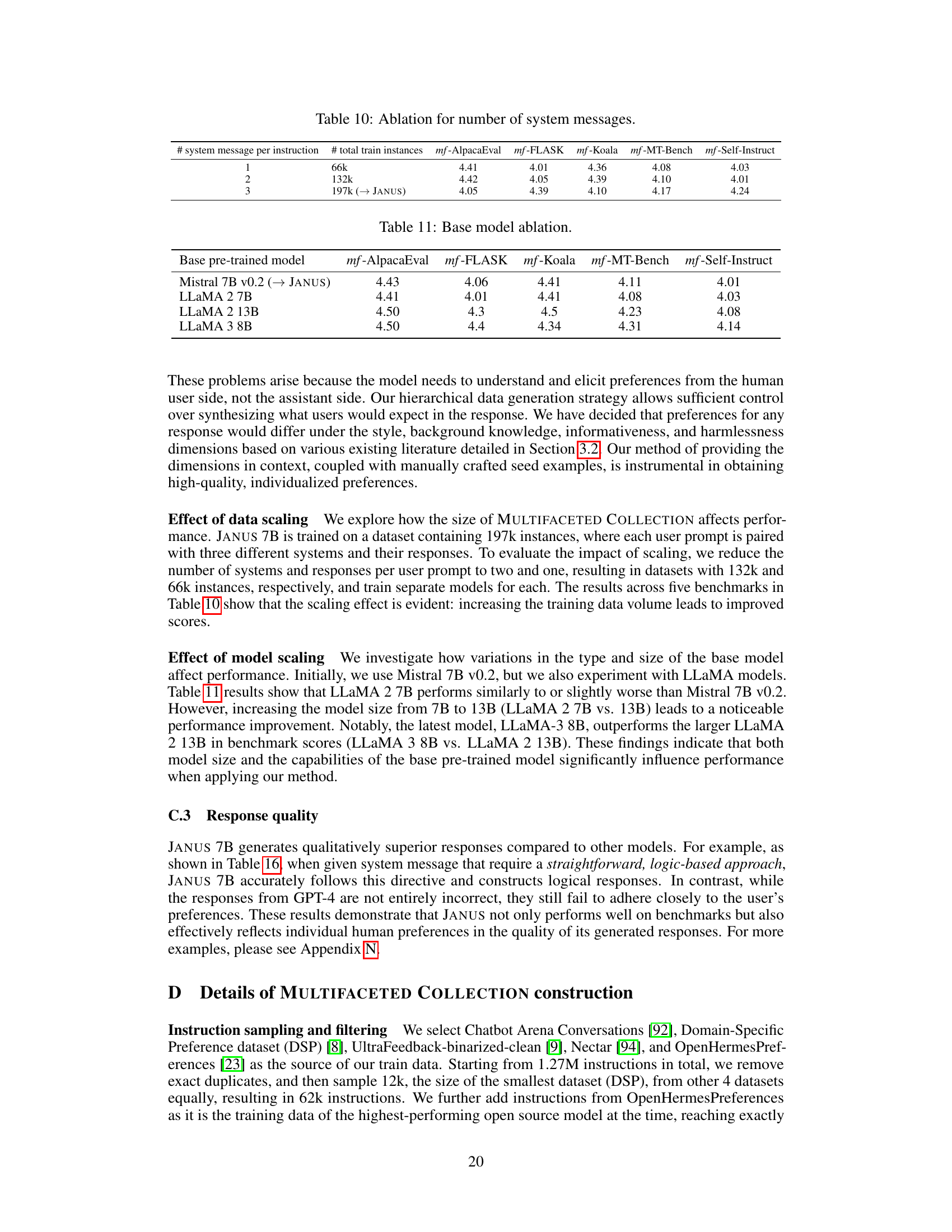

This table shows the ablation study results by varying the number of system messages used per instruction during training. The results are evaluated across five benchmarks: mf-AlpacaEval, mf-FLASK, mf-Koala, mf-MT-Bench, and mf-Self-Instruct. The average scores for each benchmark are shown for training with 1, 2, and 3 system messages per instruction, respectively. The table demonstrates that increasing the number of system messages improves the overall performance, with the best result achieved using 3 system messages per instruction (JANUS).

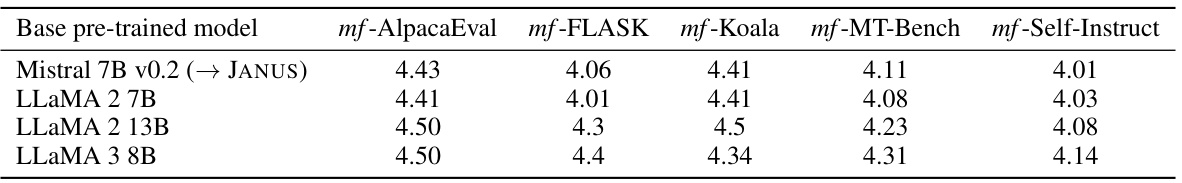

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of different base pre-trained language models when used with the proposed method. The models compared are Mistral 7B v0.2, LLaMA 2 7B, LLaMA 2 13B, and LLaMA 3 8B. The performance is evaluated across five benchmarks: mf-AlpacaEval, mf-FLASK, mf-Koala, mf-MT-Bench, and mf-Self-Instruct. The table shows that larger model sizes (LLaMA 2 13B) do not always lead to improved performance, and that the choice of base model significantly impacts results.

This table presents the results of the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark, which evaluates the performance of various LLMs in generating responses tailored to specific user preferences. The benchmark uses five different datasets (AlpacaEval 2.0, FLASK, Koala, MT-Bench, Self-Instruct) and employs an LLM as an evaluator to assign a score (1-5) to each model’s response. The scores are averaged across three evaluations for improved consistency. The table compares the performance of pretrained, instruction-tuned, and preference-optimized models, including JANUS 7B and various baseline models.

This table presents the results of the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark, which evaluates the performance of various LLMs on diverse, multifaceted instructions. Each model’s response to each instruction was scored from 1 to 5 by an evaluator LLM, with this process repeated three times to ensure reliability. The table displays the average score for each model across the benchmark, providing a comparative analysis of model performance across different instruction types and levels of complexity. It includes pretrained open models, instruction-tuned open models, and preference-optimized proprietary models.

This table presents the results of the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark, where an LLM evaluator assessed the quality of model responses on a scale of 1 to 5. The table shows the average scores for several models across five sub-benchmarks within the main benchmark. Multiple evaluations were conducted for each model to ensure reliability and consistency.

This table presents the results of the MULTIFACETED BENCH benchmark, which evaluates the performance of various LLMs in generating responses tailored to specific user preferences. Each model’s response to each prompt is scored by an LLM evaluator on a scale of 1 to 5, based on how well the response aligns with the given user preferences. The average score for each model across all prompts is calculated by averaging the scores from three separate evaluations to ensure consistency.

Full paper#