↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a powerful tool for optimizing expensive-to-evaluate functions, but it can be inefficient when dealing with functions exhibiting invariance to a known set of transformations. This inefficiency stems from repeatedly sampling the same invariant information, resulting in unnecessary computational cost and slow convergence. The existing BO algorithms do not effectively leverage these invariances, highlighting a critical need for improved efficiency in handling invariant objectives.

This paper introduces invariance-aware BO algorithms that effectively address this issue. By integrating group invariances into the kernel of the Gaussian process model used in BO, the proposed algorithms achieve significant improvements in sample efficiency. The authors provide theoretical bounds on sample complexity, demonstrating the gain achieved by incorporating invariances. Furthermore, they apply their method to both synthetic and real-world problems, including a high-performance current drive design for a nuclear fusion reactor where non-invariant methods failed. This demonstrates the practical value and effectiveness of the developed method. The improved algorithms are particularly relevant for real-world applications involving expensive simulations, as they drastically reduce the computational cost and time needed for optimization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly improves the sample efficiency of Bayesian Optimization by incorporating known invariances, thus accelerating real-world applications like nuclear fusion reactor design where evaluations are expensive. It provides novel theoretical bounds and demonstrates practical gains, opening new avenues for research in optimization algorithms and their application to complex systems. The method’s robustness to quasi-invariance adds practical value.

Visual Insights#

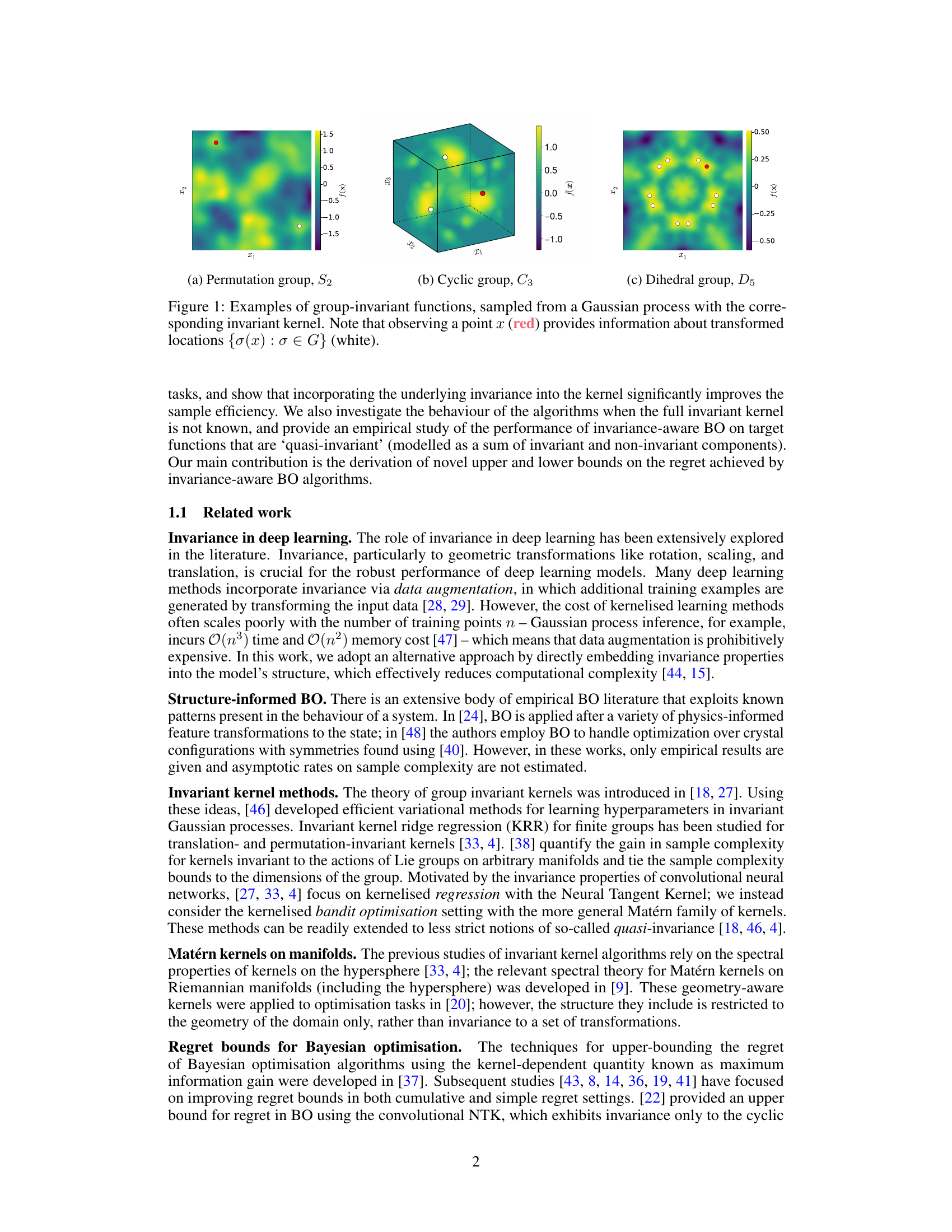

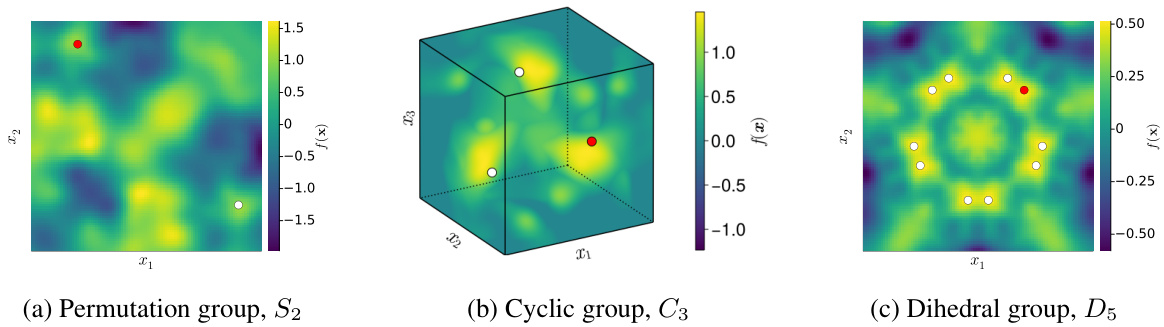

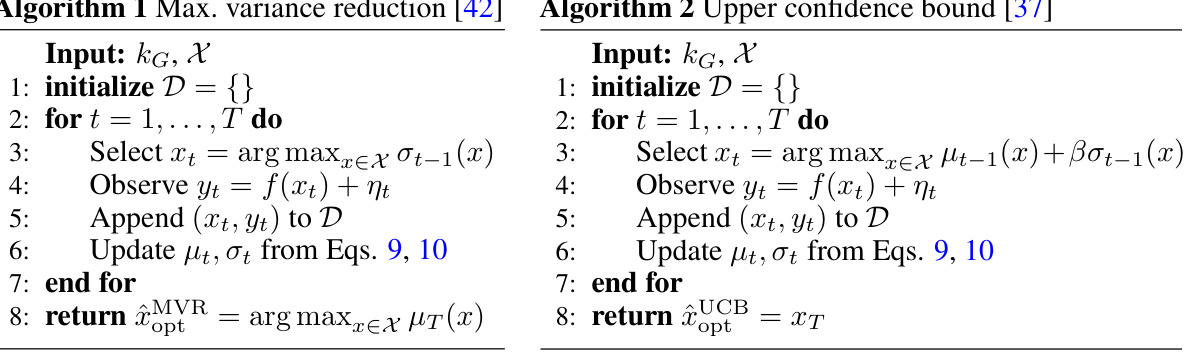

This figure shows three examples of group-invariant functions. Each function is sampled from a Gaussian process using a kernel that incorporates the invariance properties of a specific transformation group. The groups used are the permutation group S2, the cyclic group C3, and the dihedral group D5. The red point represents an observation location, and the white points represent other locations that provide information due to the function’s invariance under the group action.

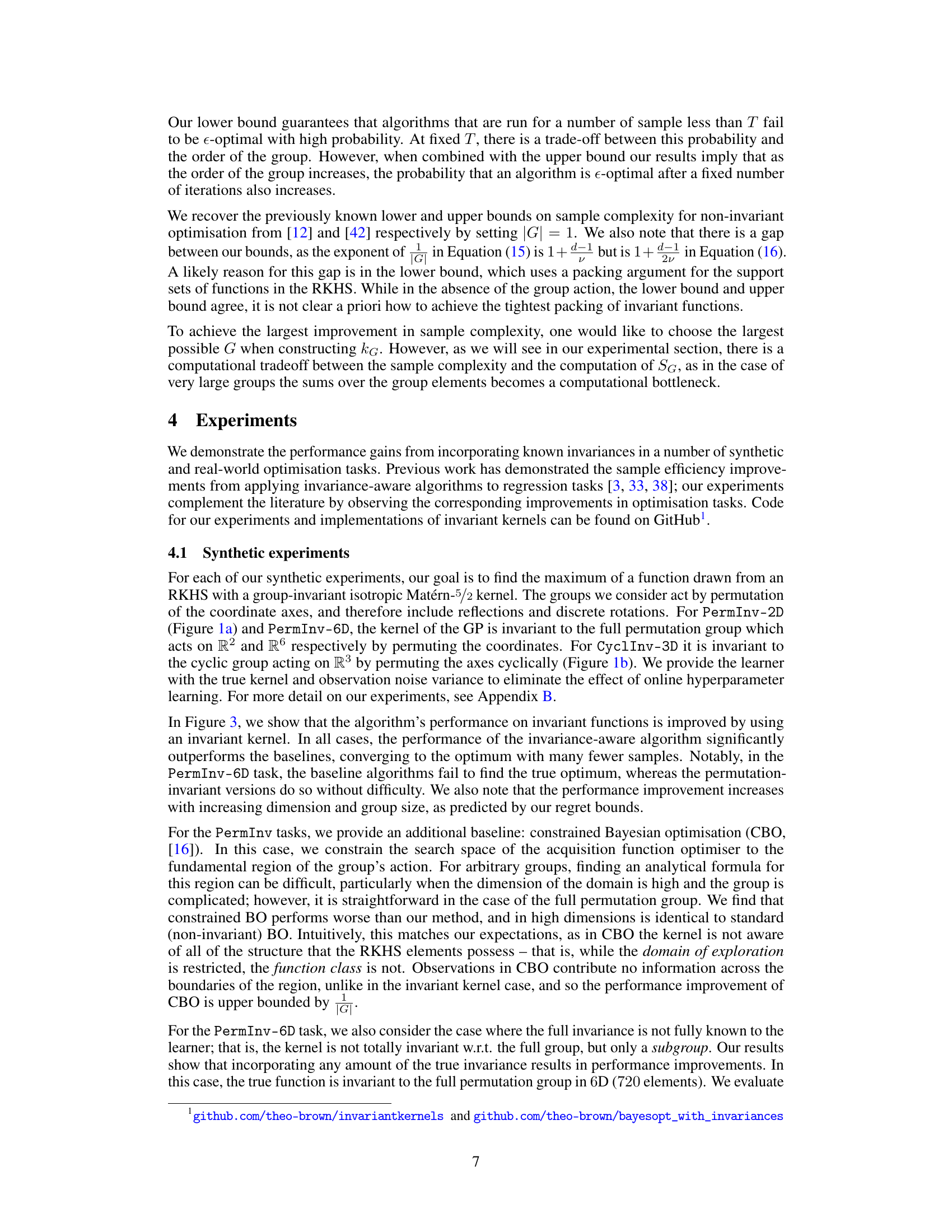

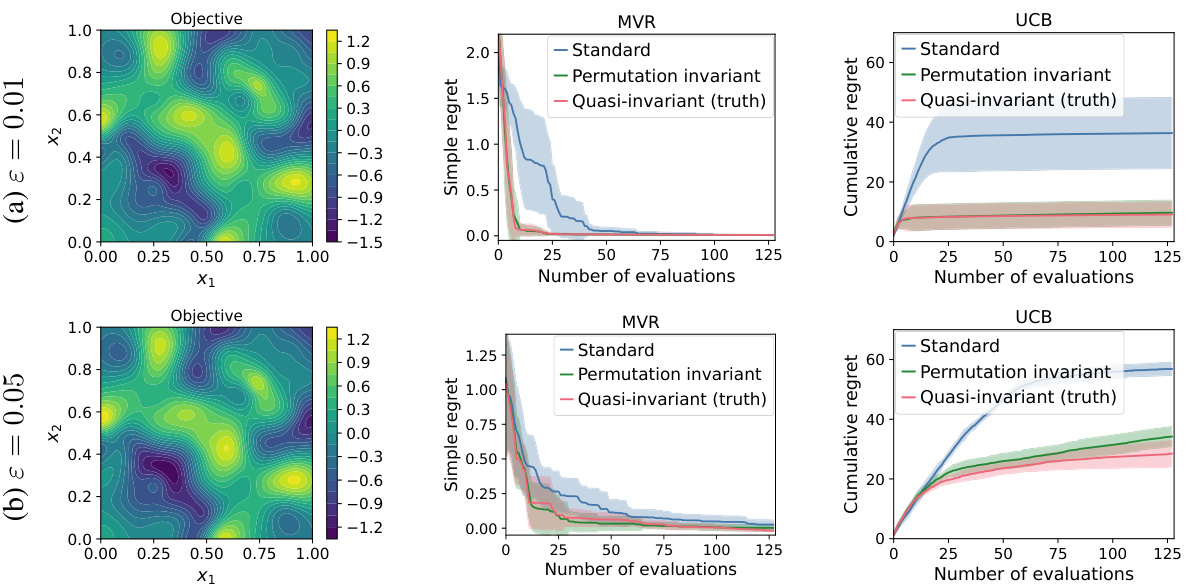

This figure compares the performance of UCB and MVR algorithms using standard kernels, invariant kernels, and partially invariant kernels on three synthetic optimization tasks with different types of invariances. It shows that using invariant kernels significantly improves performance, requiring fewer samples to reach the optimum. The results also demonstrate that even incorporating partial invariance can significantly boost performance, with a computational trade-off.

In-depth insights#

Invariant BO#

The concept of ‘Invariant Bayesian Optimization’ (Invariant BO) is a significant advancement in Bayesian optimization techniques. It leverages the inherent invariances present in many real-world optimization problems to improve sample efficiency. By incorporating known invariances into the Gaussian process kernel, Invariant BO algorithms reduce the number of expensive function evaluations needed to find an optimal solution. This is achieved by utilizing the knowledge that the objective function remains unchanged under certain transformations. This approach is especially powerful when dealing with high-dimensional or complex problems where traditional BO methods might struggle. The core innovation is the design of invariance-aware kernels within the Gaussian process framework. These kernels directly embed group-invariant properties, leading to reduced computational cost and improved performance. The paper also contributes by deriving theoretical bounds on the sample complexity of Invariant BO, demonstrating the significant gains in sample efficiency afforded by the use of invariant kernels. Furthermore, the work is validated through experiments on both synthetic and real-world applications, showcasing its effectiveness in solving challenging optimization tasks where standard BO methods fell short. In summary, Invariant BO offers a powerful and computationally efficient approach to solving complex optimization problems by exploiting inherent symmetries in the target objective.

Improved Efficiency#

The concept of “Improved Efficiency” in the context of a research paper likely refers to advancements resulting in a more efficient methodology or algorithm. This could manifest as a reduction in computational cost, memory usage, or sample complexity, all crucial factors for practical applications. Reduced sample complexity, for example, implies that fewer data points are required to achieve a similar level of accuracy or performance, directly impacting resource requirements and potentially accelerating the research process. Decreased computational cost highlights improvements in algorithm speed, making it suitable for large-scale datasets and complex analyses. Lower memory usage indicates better resource management, allowing for the processing of larger volumes of data without exceeding memory limits. The specific achievements under “Improved Efficiency” would depend on the research paper’s domain and methodology, and often involve a quantitative comparison against existing approaches, demonstrating the superior performance of the proposed method.

Regret Bounds#

Analyzing regret bounds in Bayesian Optimization (BO) unveils crucial insights into sample efficiency. Regret, measuring the difference between the objective function’s optimum and the algorithm’s choices, is a key performance metric. Upper bounds provide a theoretical limit on the maximum regret, offering guarantees on an algorithm’s worst-case performance. Tight upper bounds are valuable, indicating near-optimal sample complexity. Lower bounds, conversely, establish the minimum regret achievable by any algorithm, highlighting the inherent difficulty of the optimization problem. The interplay between upper and lower bounds reveals the gap between theoretical optimality and practical performance. Invariance-aware BO algorithms aim to leverage known symmetries to improve sample efficiency by reducing regret. Analyzing their regret bounds is crucial for quantifying the benefits of incorporating invariances. The derived bounds typically involve the size of the symmetry group, showing a decrease in regret with a larger group. Novel upper and lower bounds on sample complexity for such invariant algorithms are of significant interest and are often expressed as functions of various parameters like the group size and the kernel’s properties. The gap between upper and lower bounds signifies directions for future research in refining the theoretical understanding of invariant BO.

Fusion Reactor#

The application of Bayesian Optimization (BO) to the design of fusion reactor current drive systems is a significant contribution of this research. Fusion reactors present complex optimization challenges, involving expensive simulations and a need for high sample efficiency. The paper highlights how the inherent invariances within the physical system can be leveraged to improve BO’s performance. By incorporating these invariances into the kernel of the Gaussian Process model, the algorithm achieves superior sample efficiency and finds high-performance solutions where non-invariant methods fail. This is demonstrated by the application of this method to a real-world problem, showing that exploiting structural knowledge of the system is crucial for efficient optimization in this and similar complex settings. The results suggest that invariance-aware BO is a promising approach for tackling complex engineering design problems in fusion energy and potentially other domains with similar underlying structures.

Quasi-Invariance#

The concept of quasi-invariance offers a nuanced perspective on symmetry in Bayesian Optimization. It acknowledges that real-world functions may not exhibit perfect invariance under transformations, but rather approximate or partial invariance. This is a crucial consideration, as strict invariance is rarely found in practical applications. Quasi-invariance allows for the incorporation of known structural patterns without the need for exact symmetry, thus enhancing the robustness and practicality of invariance-aware algorithms. The key challenge lies in modeling the degree of deviation from perfect invariance and incorporating this into the kernel design. This might involve combining an invariant kernel with a non-invariant one, or developing novel kernels that specifically capture this approximate symmetry. Methods for quantifying and handling quasi-invariance are therefore essential for improving sample efficiency and generalisation performance in Bayesian Optimization. Further research is needed to explore suitable kernels, efficient methods for handling quasi-invariance, and rigorous theoretical guarantees for the performance of algorithms designed for such settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

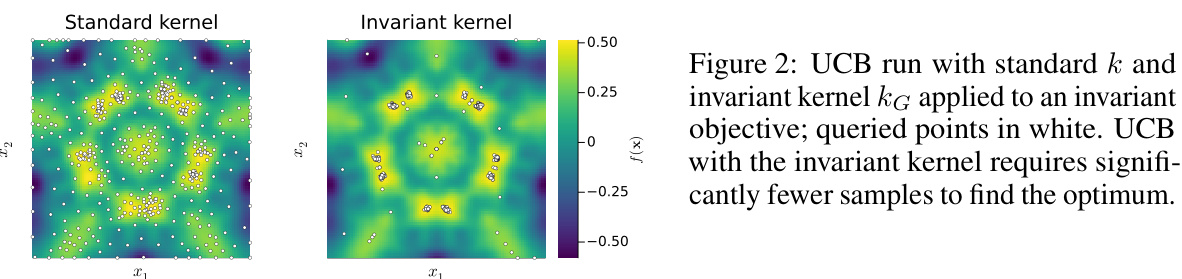

This figure compares the performance of the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithm using a standard kernel versus an invariant kernel (kG) on an invariant objective function. The queried points (where the function is evaluated) are shown in white. The plot demonstrates that the UCB algorithm using the invariant kernel converges to the optimum with far fewer function evaluations than the one using a standard kernel. This illustrates the efficiency gain achieved by incorporating known invariances into the kernel of the Bayesian optimization algorithm.

This figure compares the performance of UCB and MVR algorithms on three different synthetic optimization tasks using different kernels: standard, constrained, and invariant. The results demonstrate that incorporating group invariance into the kernel significantly improves sample efficiency compared to standard and constrained methods, even when only partial invariance is included.

This figure shows the results of experiments on quasi-invariant functions, which are functions that are almost invariant to a known group of transformations. The figure compares the performance of three different Bayesian optimization algorithms: the standard algorithm, the algorithm that uses an invariant kernel (kg), and the algorithm that uses a quasi-invariant kernel (kg + ɛk’). The results show that the algorithm that uses the invariant kernel performs almost as well as the algorithm that uses the quasi-invariant kernel, and that both of these algorithms outperform the standard algorithm. The plots show both simple regret and cumulative regret for the three algorithms, across different noise levels.

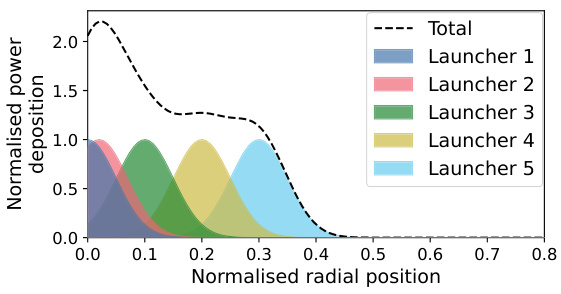

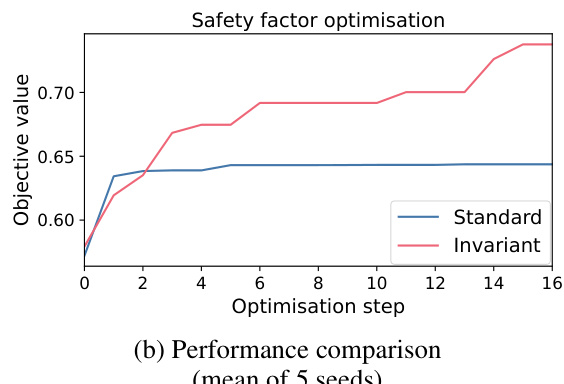

This figure shows the results of applying the invariance-aware Bayesian optimization method to a real-world problem in nuclear fusion engineering. Panel (a) illustrates an example of a current drive actuator profile, highlighting the permutation invariance property; the order of the launchers can be changed without affecting the total profile. Panel (b) compares the performance of the standard UCB algorithm with the invariance-aware UCB algorithm. The invariance-aware approach demonstrates significantly improved performance, achieving better results with fewer samples.

This figure shows the results of applying the invariant UCB algorithm to a real-world nuclear fusion problem. Subfigure (a) illustrates the current drive actuator profile, highlighting the permutation invariance of the system (changing the order of the launchers does not affect the total profile). Subfigure (b) presents a performance comparison between the standard UCB and the invariant UCB. The invariant UCB shows significantly improved performance, achieving better safety factor optimization values with fewer optimization steps.

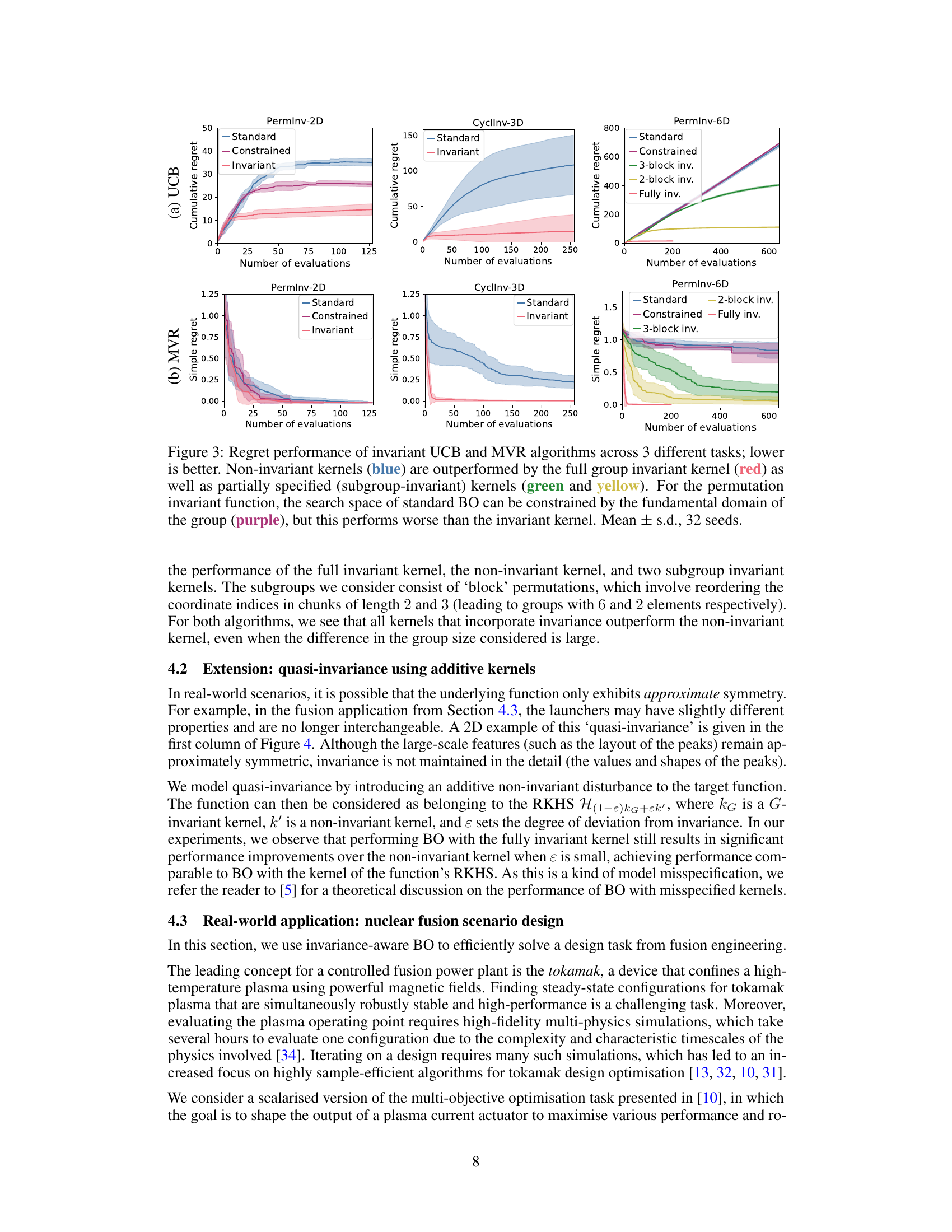

This figure compares the memory and time efficiency of using invariant kernels versus data augmentation for Bayesian Optimization. It shows that invariant kernels require significantly less memory and computation time, especially as the size of the symmetry group increases. The full invariance case using data augmentation runs out of GPU memory, highlighting the advantage of invariant kernels for high-dimensional problems with large symmetry groups.

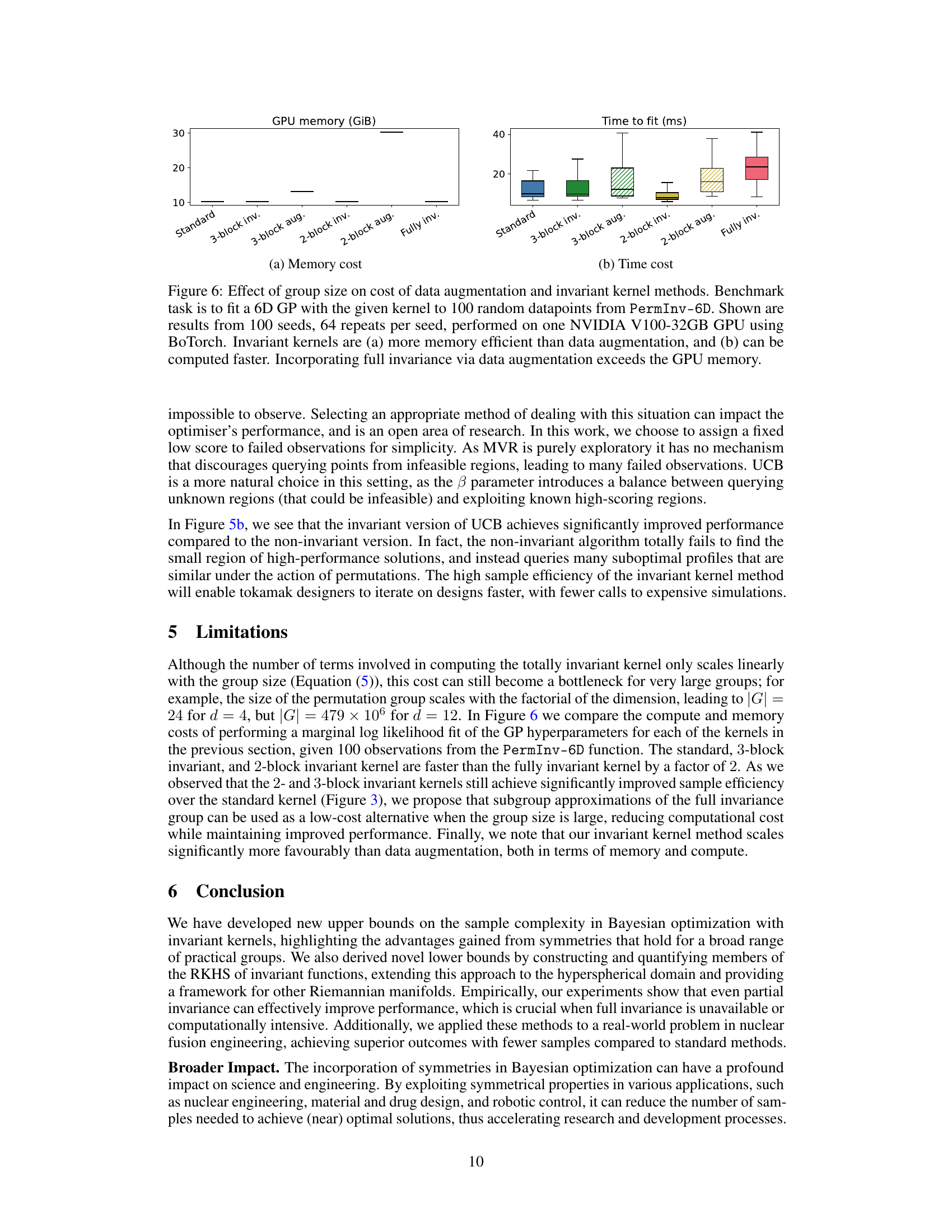

This figure shows two examples of invariant functions on a sphere. The left image (7a) displays a function invariant to a 10-fold rotation, while the right image (7b) shows a function invariant to all rotations about a single axis. The paper’s authors used functions like 7a (invariant under finite rotations) to construct a lower bound on sample complexity, explicitly excluding functions such as 7b that would lead to different function packing behaviors and affect the resulting bound.

Full paper#