↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) model is widely used in survival analysis due to its interpretability and predictive power. However, current training algorithms based on the Newton method often struggle with convergence issues, especially when dealing with high-dimensional datasets or highly correlated features. This limitation arises from vanishing second-order derivatives outside the local region of the minimizer. The paper highlights the problem with existing approaches, including exact, quasi, and proximal Newton methods, that struggle with convergence and precision.

To address these shortcomings, FastSurvival introduces new optimization methods that leverage hidden mathematical structures of the CPH model. By constructing and minimizing surrogate functions, these new methods guarantee monotonic loss decrease and global convergence. Importantly, they achieve linear-time complexity (O(n)) for computing first and second-order derivatives. Empirical results demonstrate a significant increase in computational efficiency compared to existing methods, enabling the construction of sparse, high-quality models for cardinality-constrained CPH problems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with Cox Proportional Hazards models because it addresses critical limitations of existing optimization methods. It offers novel, efficient algorithms that guarantee convergence and high precision, overcoming challenges related to high dimensionality and correlated features. The introduced methods are easily implementable and applicable to various problems, including variable selection. This work opens doors for further research on the CPH model’s mathematical structure and its applications.

Visual Insights#

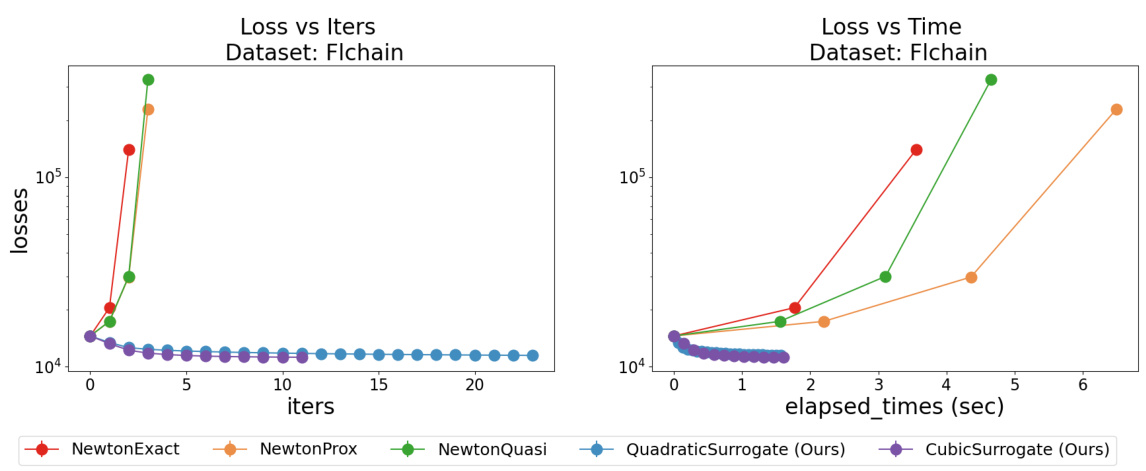

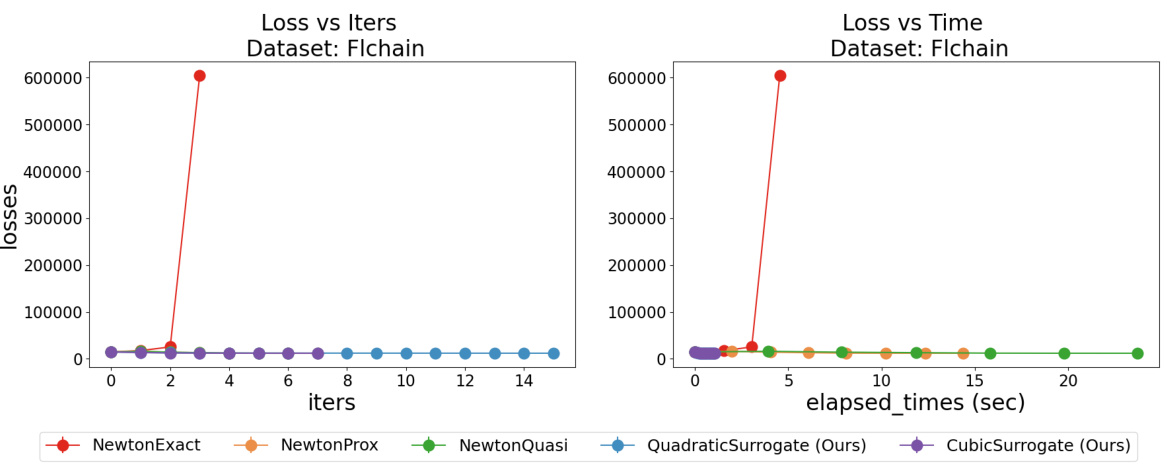

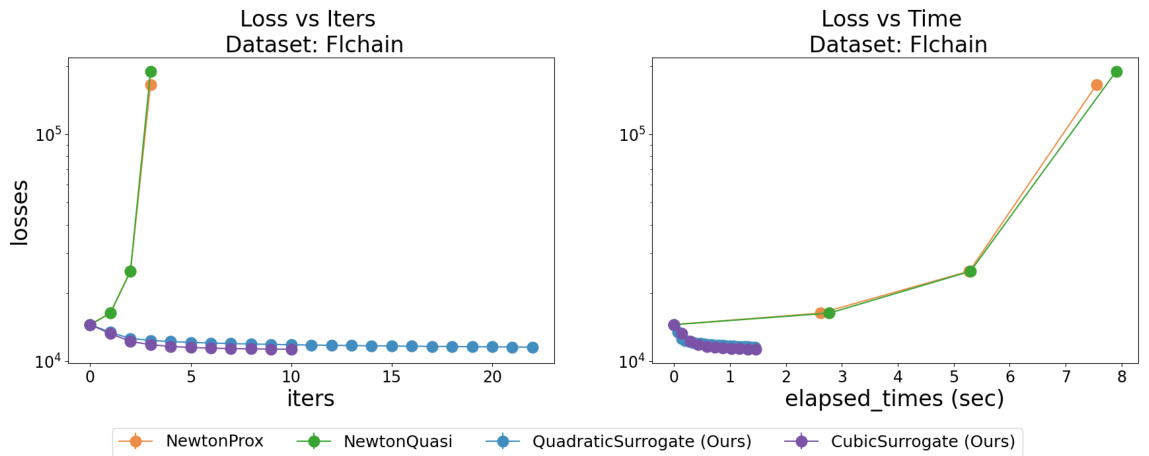

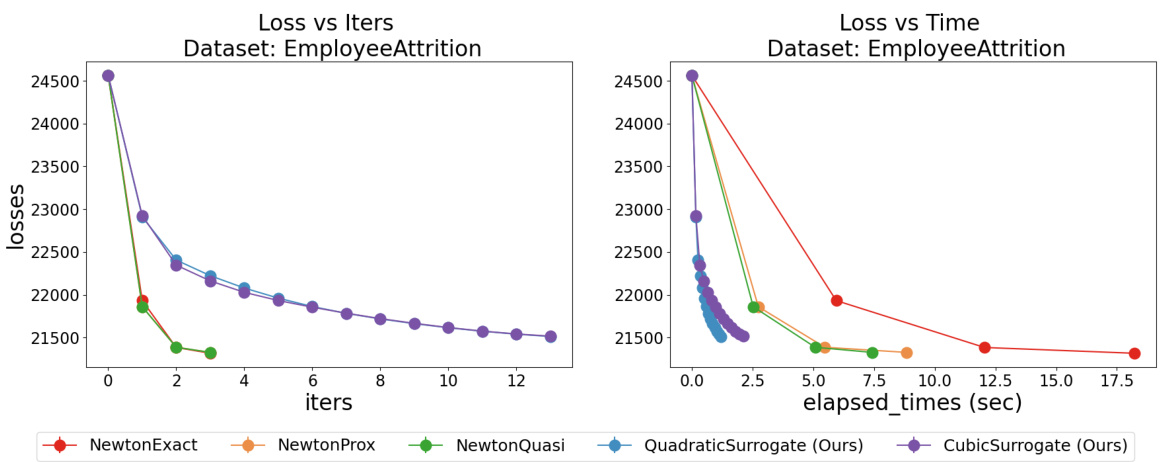

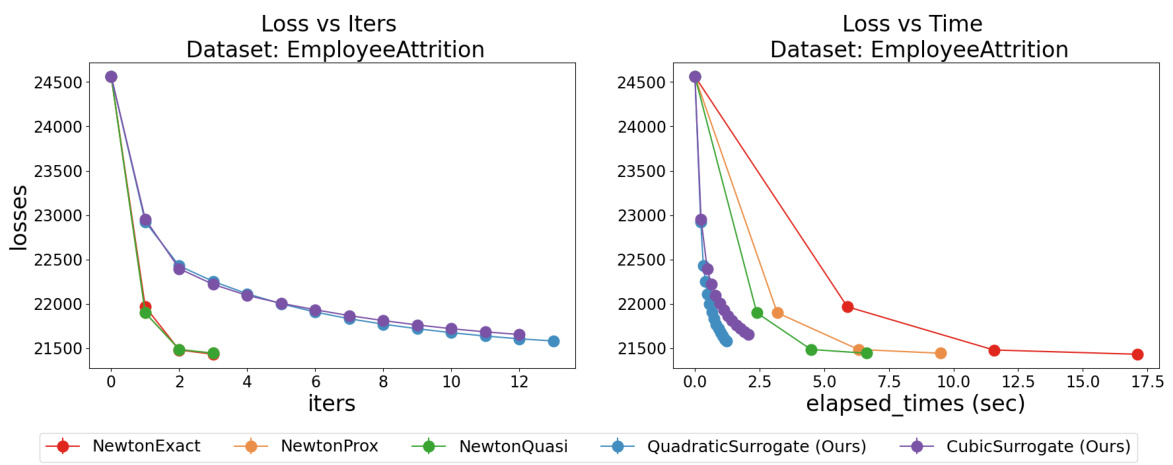

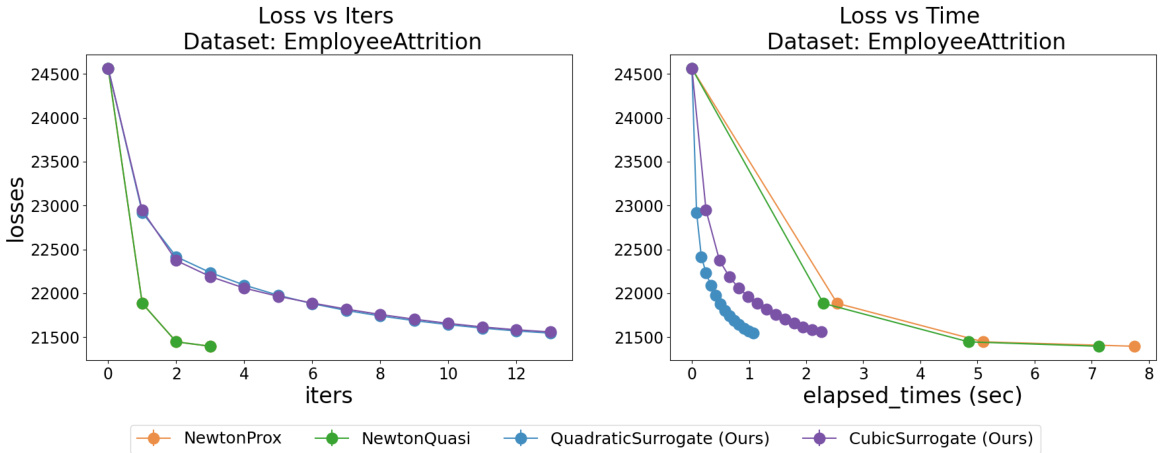

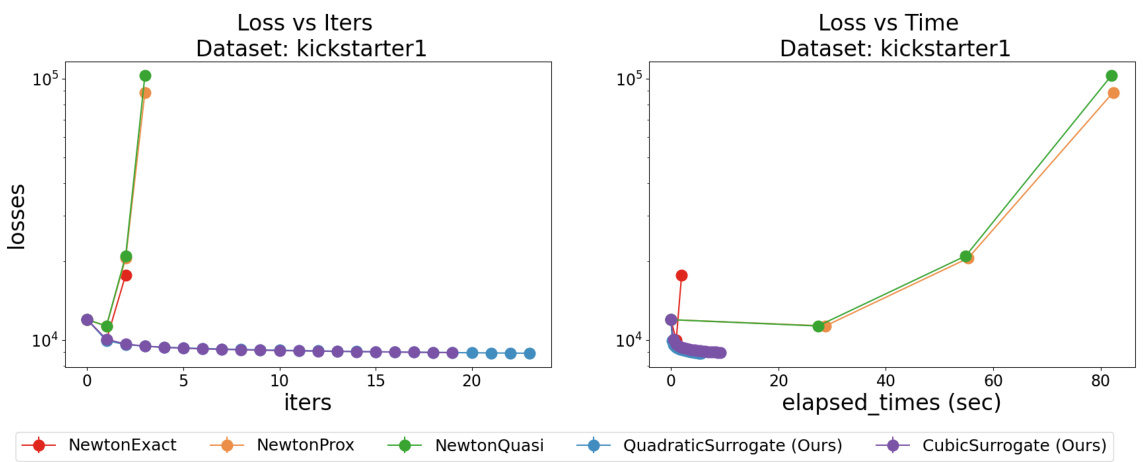

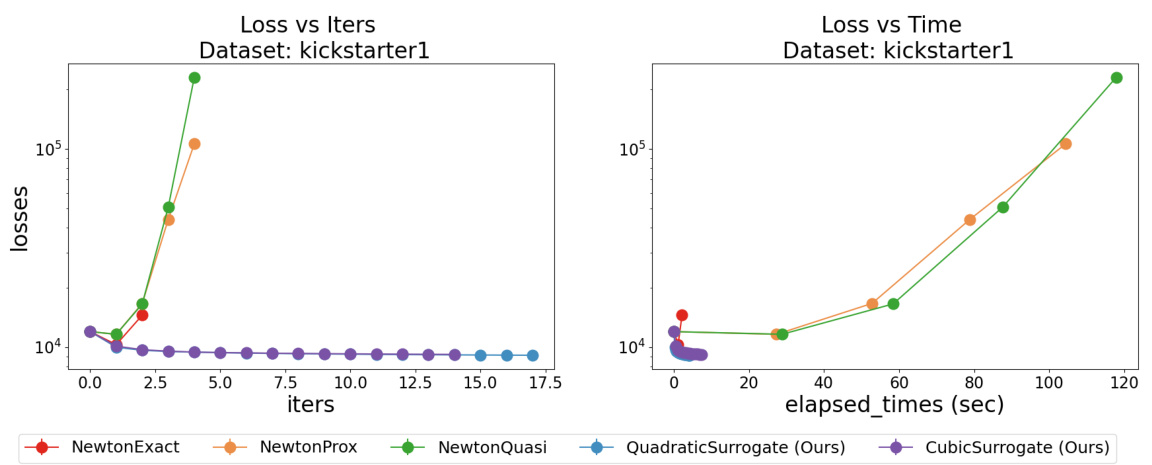

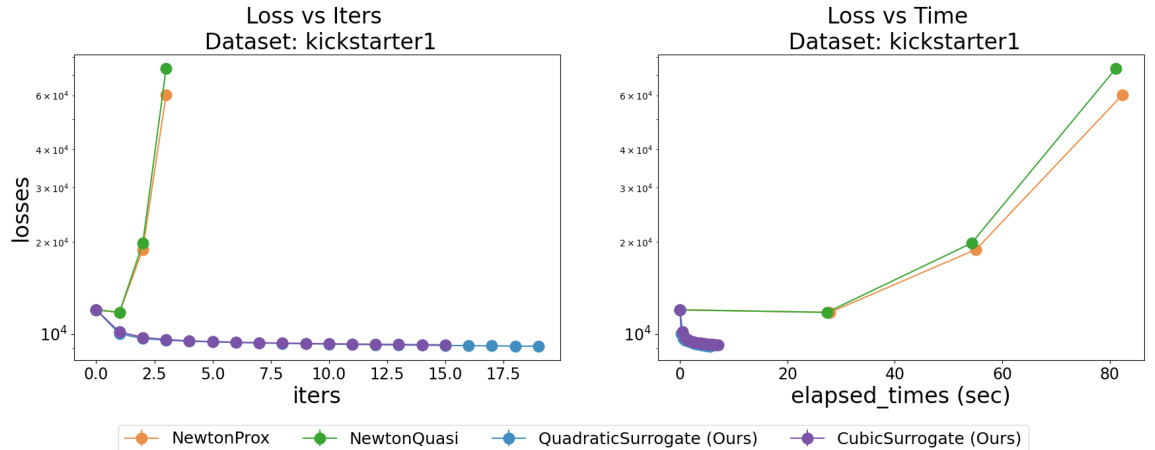

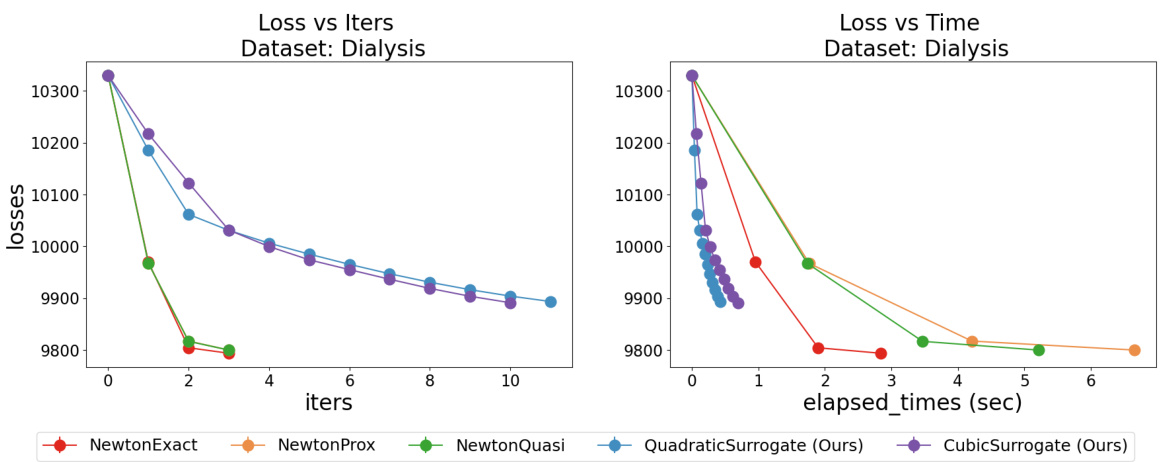

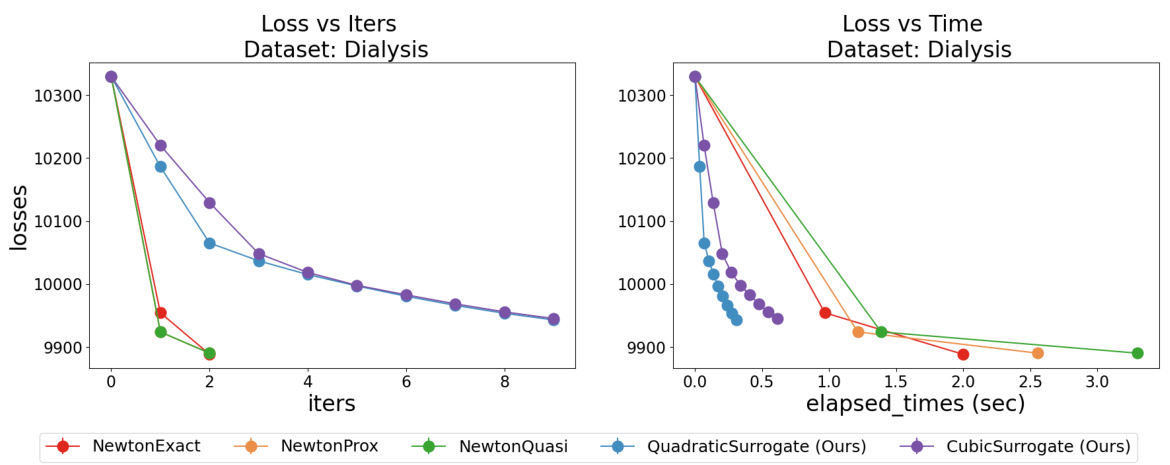

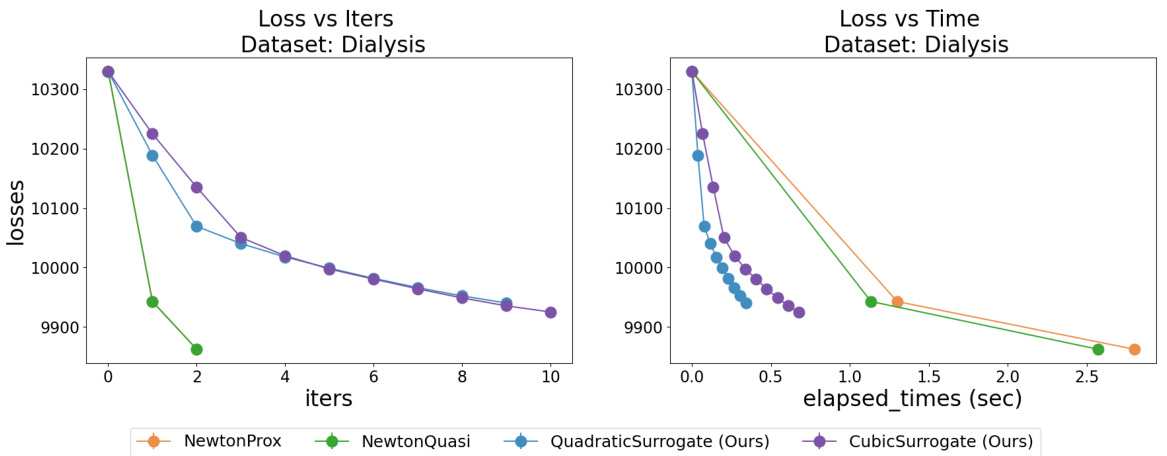

This figure compares the performance of the proposed optimization methods (quadratic and cubic surrogates) against existing Newton-type methods (exact Newton, quasi-Newton, proximal Newton) for training Cox Proportional Hazards models. Two regularization scenarios are shown: l2 regularization and combined l1 + l2 regularization. The plots demonstrate that the proposed methods achieve monotonic loss decrease and superior speed compared to existing methods. Note that the Newton-type methods fail to converge for weak regularization in the l2 scenario, while in the l1+l2 scenario, their speed is considerably lower than that of the proposed methods.

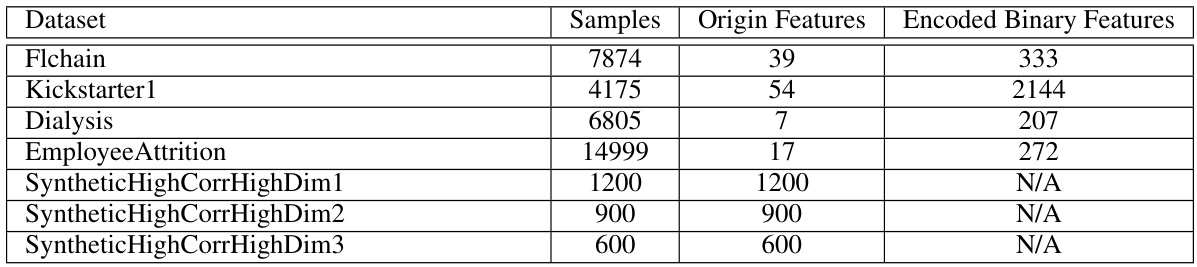

This table summarizes the datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it shows the number of samples, the number of original features, and the number of encoded binary features (after binarization of continuous features, if applicable). The datasets include real-world datasets (like Flchain, Kickstarter1, Dialysis, and EmployeeAttrition) and synthetic datasets created to specifically test performance in situations with high feature correlation (SyntheticHighCorrHighDim1, SyntheticHighCorrHighDim2, SyntheticHighCorrHighDim3).

In-depth insights#

CPH Optimization#

This research paper focuses on improving the training process of Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models, a crucial tool in survival analysis. The core issue addressed is the inefficiency and convergence problems associated with current optimization algorithms for CPH models, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional datasets and correlated features. The authors pinpoint the limitations of existing Newton-type methods, highlighting their susceptibility to vanishing second-order derivatives and slow convergence. Their proposed solution introduces novel optimization techniques that leverage hidden mathematical structures within the CPH model. By constructing and minimizing surrogate functions (quadratic and cubic), they achieve faster convergence speeds with guaranteed monotonic loss decrease and global convergence. This methodological breakthrough enables the practical application of CPH models to more complex, high-dimensional scenarios. A key contribution is the ability to efficiently solve cardinality-constrained CPH problems, leading to sparse, high-quality models that were previously impractical to obtain. The empirical results demonstrate the substantial improvement in computational efficiency and the superior performance of the proposed methods compared to state-of-the-art approaches.

Surrogate Functions#

The concept of surrogate functions is central to the proposed optimization method in the research paper. Surrogate functions offer a computationally tractable approximation of the complex, original cost function associated with training Cox Proportional Hazards models. The authors cleverly exploit the mathematical structure of the CPH model to construct quadratic and cubic surrogate functions. The use of surrogate functions ensures monotonic decrease of loss and global convergence, overcoming the limitations of Newton-based methods that suffer from convergence issues due to vanishing second-order derivatives. These surrogate functions are strategically chosen to enable efficient analytical solutions, facilitating fast and precise model training. The mathematical justification for using quadratic and cubic surrogates, including the derivation of Lipschitz constants, is a significant theoretical contribution and is crucial to the algorithms’ efficiency and convergence guarantees. The effectiveness of this approach is empirically demonstrated and highlights a key advantage of the proposed methodology.

Variable Selection#

The paper explores variable selection within the context of Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models, a significant challenge due to high dimensionality and correlated features in modern datasets. Traditional methods based on the Newton method struggle with convergence, especially when precision is required. The authors’ novel approach addresses this by introducing new optimization techniques that exploit hidden mathematical structures within the CPH model. These techniques yield efficient algorithms that guarantee monotonic loss decrease and global convergence, outperforming existing methods in terms of both speed and precision. A key application highlighted is solving the cardinality-constrained CPH problem, enabling the creation of sparse, high-quality models not previously feasible. The connection between the CPH model’s derivatives and central moments provides the mathematical basis for their efficient, exact calculations, circumventing approximations used in prior methods. Empirical evidence across synthetic and real-world datasets demonstrates the superior performance of their variable selection method, especially in the presence of highly correlated features, where it significantly improves F1 scores and produces models with far fewer coefficients while retaining predictive performance. This work represents a methodological breakthrough for CPH model training, opening doors for further research in optimization and theoretical understanding of the model’s mathematical structure.

Computational Speed#

The research paper emphasizes achieving computational efficiency in training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models. Current methods, based on Newton’s method, suffer from slow convergence, particularly with high-dimensional data and correlated features. The authors address this by designing new optimization methods that exploit the hidden mathematical structure of the CPH model. This leads to exact, linear-time calculations for first and second-order partial derivatives, a significant improvement over existing O(n²) methods. Empirically, the proposed algorithms demonstrate superior speed and high-precision convergence, outperforming traditional Newton-type methods in multiple scenarios. This breakthrough opens up new optimization opportunities for the CPH model and addresses challenges previously hindering its application in large-scale settings, including variable selection within highly correlated feature spaces.

Future Research#

The paper’s ‘Future Research’ section implicitly suggests several promising avenues. Extending the methodology to handle time-varying features and incorporating stratifications within the Cox Proportional Hazards model would significantly broaden its applicability. The exploration of higher-order partial derivatives and their Lipschitz continuity offers a compelling theoretical challenge that could yield further algorithmic improvements. Furthermore, investigating the mathematical structure of CPH to uncover additional hidden blessings for optimization, along with a systematic exploration of other CPH-related applications, is crucial. Finally, exploring the potential of adaptive optimization strategies that combine the strengths of first and second-order methods presents an exciting direction. Successfully addressing these points would enhance both the theoretical understanding and practical usability of the CPH model, likely leading to more efficient and robust solutions for a wider array of applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

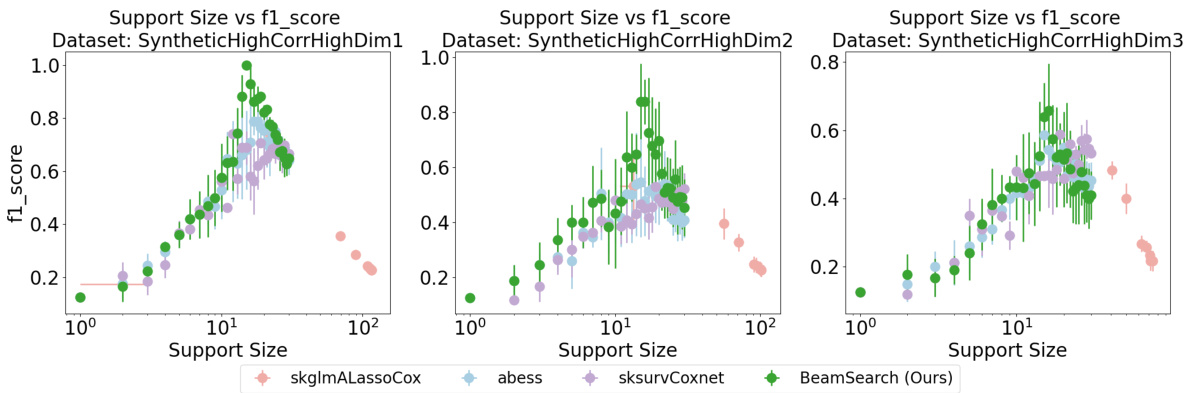

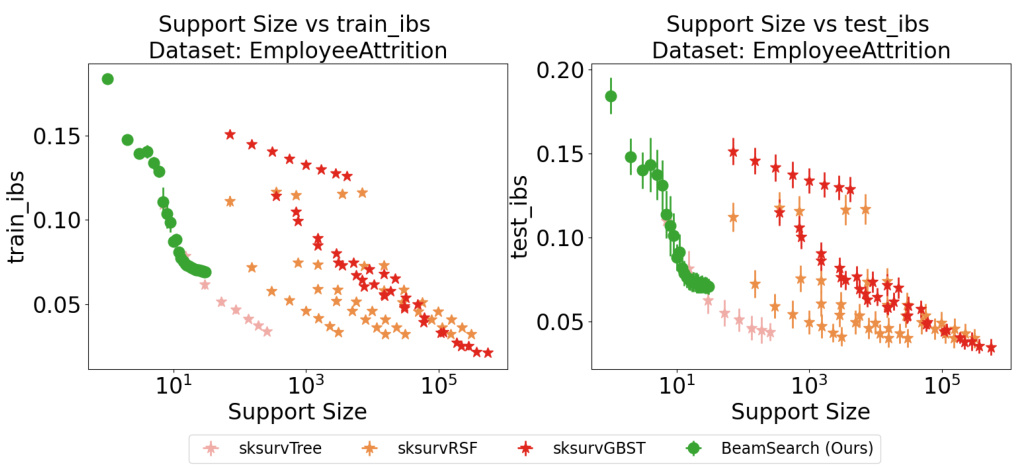

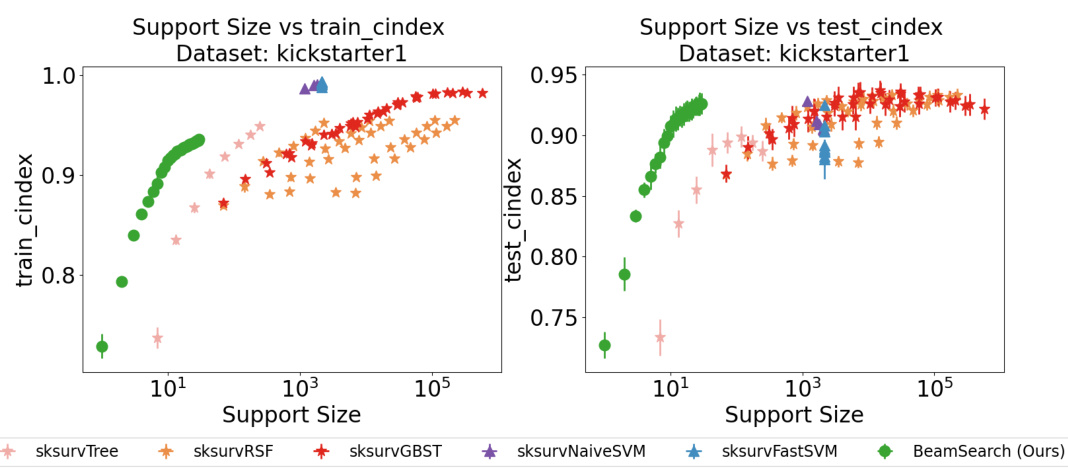

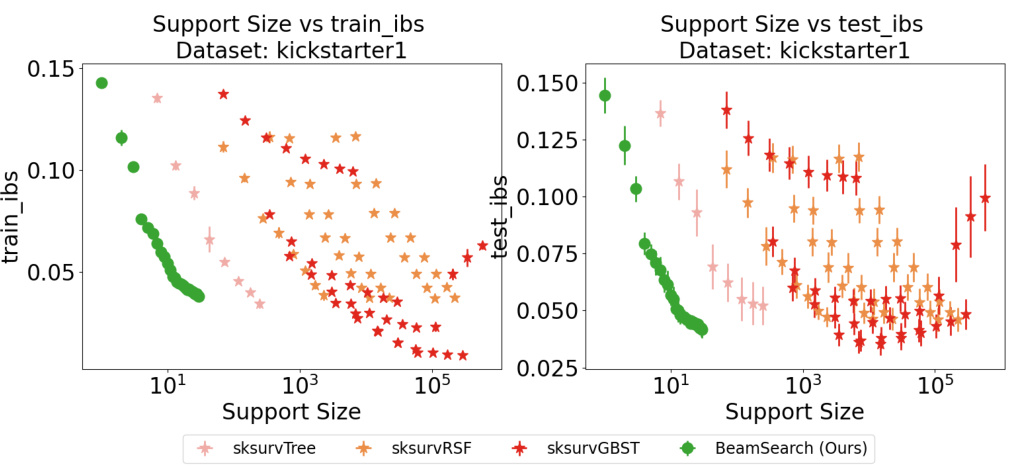

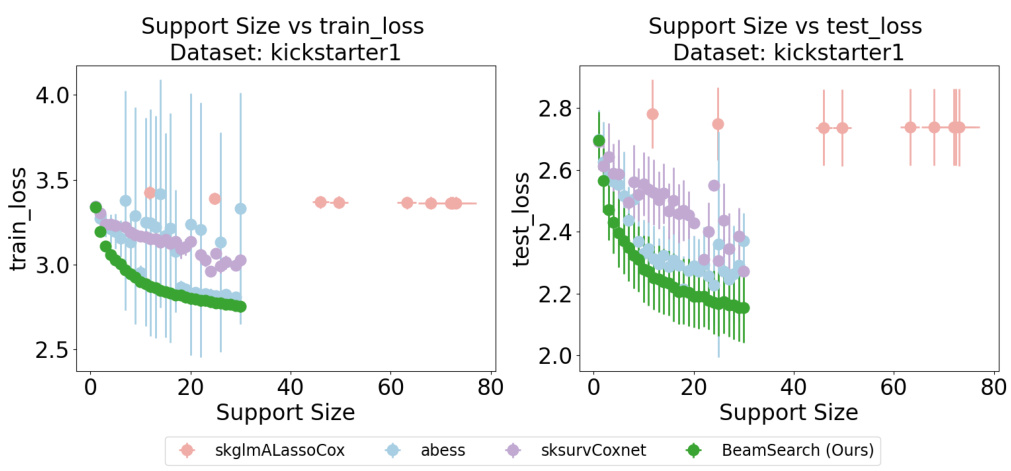

This figure compares the performance of four different variable selection methods on three synthetic datasets with high feature correlation. The datasets vary in sample size (1200, 1000, and 800). The x-axis represents the number of selected features (support size), and the y-axis represents the F1-score, a metric that balances precision and recall in feature selection. The results show that the proposed ‘BeamSearch (Ours)’ method significantly outperforms existing methods, achieving 100% support recovery on the largest dataset. As expected, performance degrades slightly as the sample size decreases for all methods.

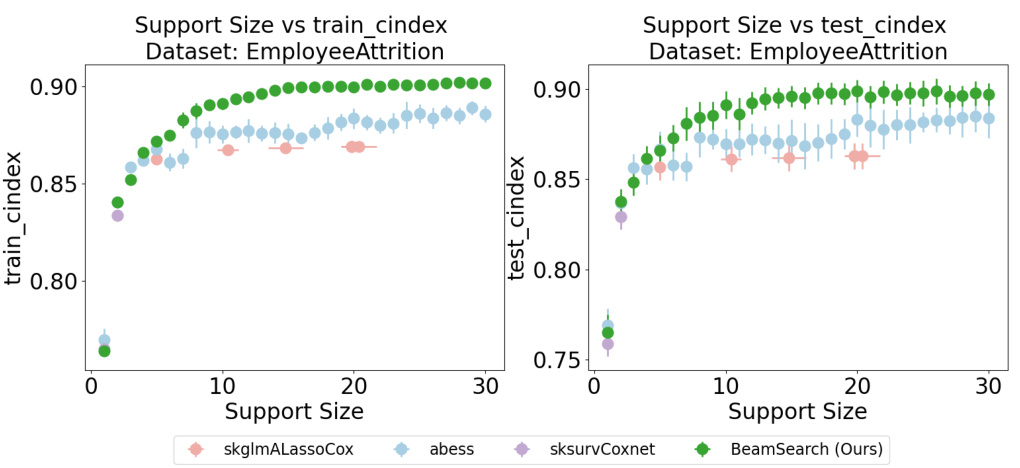

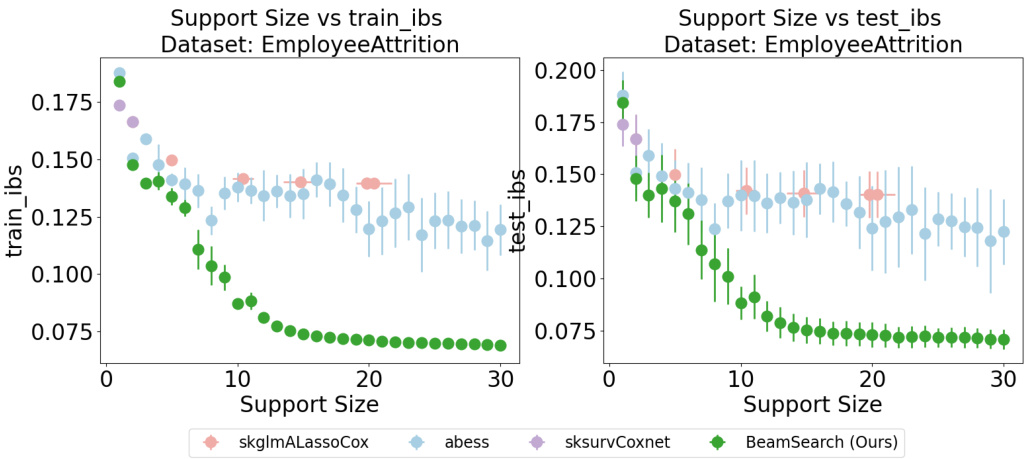

This figure compares the performance of several Cox models (skglmALassoCox, abess, sksurvCoxnet, and BeamSearch) on the Employee Attrition dataset. The plots show the relationship between support size (number of selected features) and the concordance index (C-index), a measure of predictive accuracy for survival models. The top row displays training C-index versus support size while the bottom row displays testing C-index versus support size. The goal is to show that our BeamSearch method can achieve a good C-index (high predictive accuracy) with a smaller support size (fewer features) than other existing Cox models. This indicates it is more efficient and potentially more interpretable.

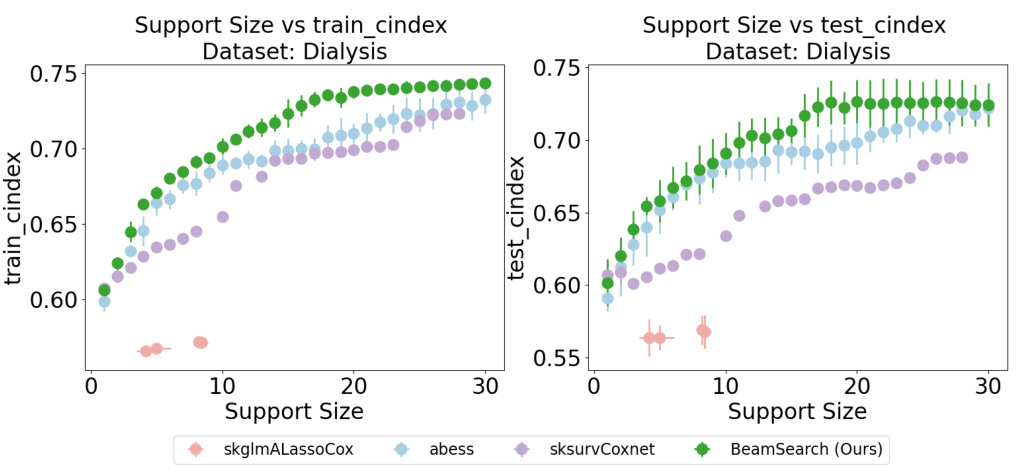

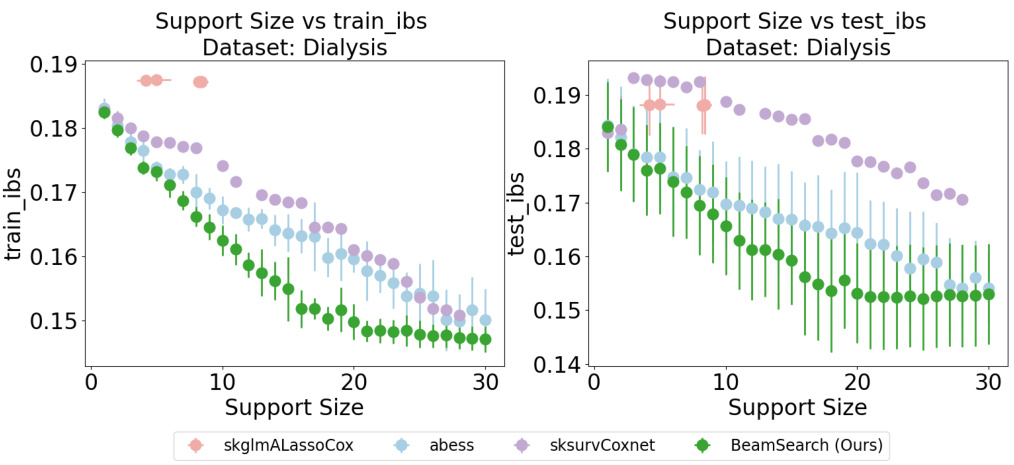

This figure compares the performance of different Cox proportional hazards models on the Dialysis dataset in terms of C-index. The x-axis represents the support size (number of selected features), and the y-axis represents the C-index for both training and testing sets. The plot shows that BeamSearch (the authors’ method) achieves higher C-index values with smaller support sizes compared to other methods like skglmALassoCox, abess, and sksurvCoxnet. This demonstrates the effectiveness of BeamSearch in selecting important features and building a sparse yet accurate model.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method with existing Newton-type methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards models on the Flchain dataset. The plots show that FastSurvival converges faster and avoids the loss explosion issues encountered by the Newton-type methods, especially when regularization is weak. Both l2 and l1+l2 regularization scenarios are shown.

The figure compares the performance of the proposed optimization methods (quadratic and cubic surrogates) with existing Newton-type methods (exact Newton, quasi-Newton, and proximal Newton) for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models on the Flchain dataset. The left plots show loss vs. iterations for l2-regularized (λ2 = 1) and l1 + l2-regularized (λ1 = 1, λ2 = 5) CPH problems. It demonstrates that the proposed methods ensure monotonic loss decrease, unlike the Newton-type methods which show loss explosion or slow convergence in the l2 case and slower convergence in l1 + l2. The right plots show loss vs. time, highlighting the superior computational efficiency of the proposed methods. Appendix D provides more results on different datasets.

The figure compares the performance of the proposed methods (quadratic and cubic surrogates) with three baseline Newton-type methods (exact Newton, quasi-Newton, proximal Newton) for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models on the Flchain dataset. It shows that the proposed methods maintain monotonically decreasing loss functions, while the baselines often encounter issues of loss explosion, especially when regularization is weak. Furthermore, the proposed methods achieve significantly faster convergence times.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method against existing optimization methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models. The plots show the loss function value over iterations and time for both l2-regularized and l1+l2-regularized CPH problems, highlighting the superior speed and convergence of FastSurvival, especially when handling weak regularization where other methods fail to converge.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method against several baseline methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards models. The left plots demonstrate that FastSurvival avoids the issue of exploding losses observed in the baseline Newton-type methods, especially when regularization is weak. The right plots showcase that FastSurvival achieves significant speed improvements compared to the baselines due to its efficient computation of first and second-order derivatives, leading to faster convergence in terms of wall-clock time.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method with existing methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards models on the Flchain dataset. It shows that FastSurvival achieves monotonic loss decrease and is significantly faster than existing methods, even when dealing with high-dimensional or highly correlated data, addressing the vanishing second-order derivative issues of existing Newton-based methods.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method against existing Newton-type methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models. It shows that FastSurvival converges much faster and more reliably than other methods, particularly when regularization is weak. The plots illustrate both the number of iterations and the elapsed time to reach convergence for l2 and l1+l2 regularized CPH problems, highlighting FastSurvival’s computational efficiency.

The figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method against existing Newton-type methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards models on the Flchain dataset. It shows that FastSurvival ensures monotonic loss decrease and converges faster, especially when regularization is weak, highlighting its computational efficiency and robustness.

The figure compares the performance of the proposed methods with existing Newton-type methods in solving l2-regularized and l1+l2-regularized CPH problems. The left plots show the loss versus the number of iterations, while the right plots illustrate the loss versus the elapsed time. The results demonstrate that the proposed methods converge faster and maintain monotonic loss decrease, unlike the Newton-type methods which often show loss explosion.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival methods against existing Newton-type methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards models on the Flchain dataset. It demonstrates that FastSurvival achieves monotonic loss decrease and superior speed, particularly when regularization is weak, unlike the Newton-type methods which experience loss explosions.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival methods against existing Newton-type methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards models on the Flchain dataset. It shows that under weak regularization, Newton methods fail to converge, while FastSurvival maintains monotonically decreasing loss. Furthermore, it demonstrates that FastSurvival’s computational efficiency leads to faster convergence in wall-clock time, even when compared to approximate Newton methods.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method against other optimization methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards models. It shows that FastSurvival ensures monotonic loss decrease and faster convergence compared to baseline methods, even when dealing with high-dimensional and correlated datasets.

The figure shows the efficiency of the proposed methods against existing methods for l2 and l1+l2 regularized Cox proportional hazard models. The results indicate that the proposed methods are significantly faster than existing methods and ensure monotonic loss decrease, unlike existing methods that show loss explosion when regularization is weak.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed optimization methods (quadratic and cubic surrogates) with existing Newton-type methods (exact Newton, quasi-Newton, proximal Newton) for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models on the Flchain dataset. Two regularization scenarios are shown: l2 regularization (λ2 = 1) and combined l1 + l2 regularization (λ1 = 1, λ2 = 5). The plots illustrate loss versus number of iterations and loss versus elapsed time. The results demonstrate the superior convergence speed and stability of the proposed methods compared to the baselines.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed optimization methods (quadratic and cubic surrogates) against existing Newton-type methods (exact, quasi, and proximal Newton) for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models on the Flchain dataset. It shows that the proposed methods exhibit faster convergence and prevent loss explosion, a common issue with Newton-type methods, especially when regularization is weak. The efficiency of the proposed methods is attributed to their low computational cost per iteration.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed methods (quadratic and cubic surrogates) with existing Newton-type methods (exact Newton, quasi-Newton, and proximal Newton) for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models on the Flchain dataset. It shows that under weak regularization, Newton-type methods fail to converge, while the proposed methods demonstrate monotonic loss decrease. Furthermore, even under stronger regularization, the proposed methods show significantly faster convergence in terms of both iterations and wall-clock time.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method against existing Newton-type methods (exact Newton, quasi-Newton, proximal Newton) for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models. Two regularization scenarios are shown: l2 regularization (λ2 = 1 and λ2 = 5) and l1 + l2 regularization (λ1 = 1, λ2 = 5). The plots demonstrate that FastSurvival exhibits faster convergence and avoids the loss explosion issues observed in the baseline Newton methods.

This figure compares the performance of different Cox proportional hazards models on the Dialysis dataset in terms of C-index. The x-axis represents the support size (number of features used in the model), while the y-axis shows the C-index (a measure of predictive accuracy). The plot includes results for four models: skglmALassoCox, abess, sksurvCoxnet, and BeamSearch (the authors’ proposed method). Separate lines display the training and testing C-indices for each model. The results suggest that BeamSearch achieves similar or better predictive performance with a substantially smaller support size than the other methods, highlighting its ability to select important features and build more efficient models.

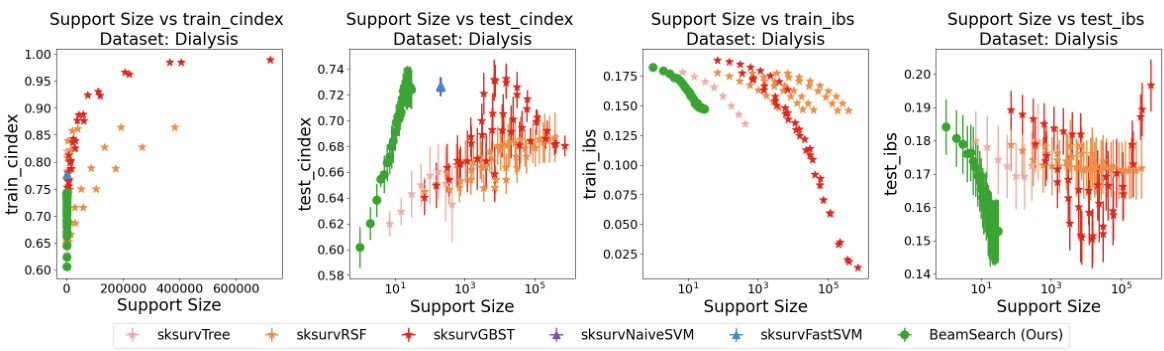

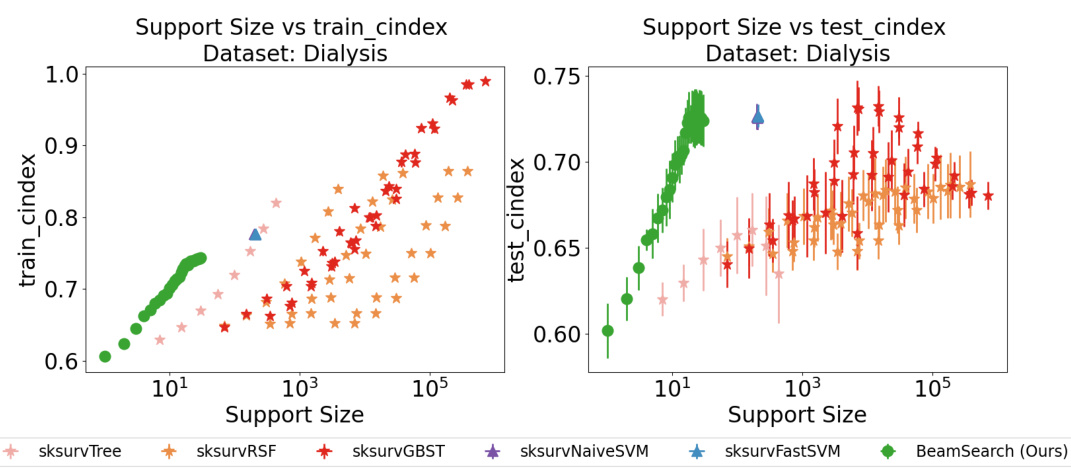

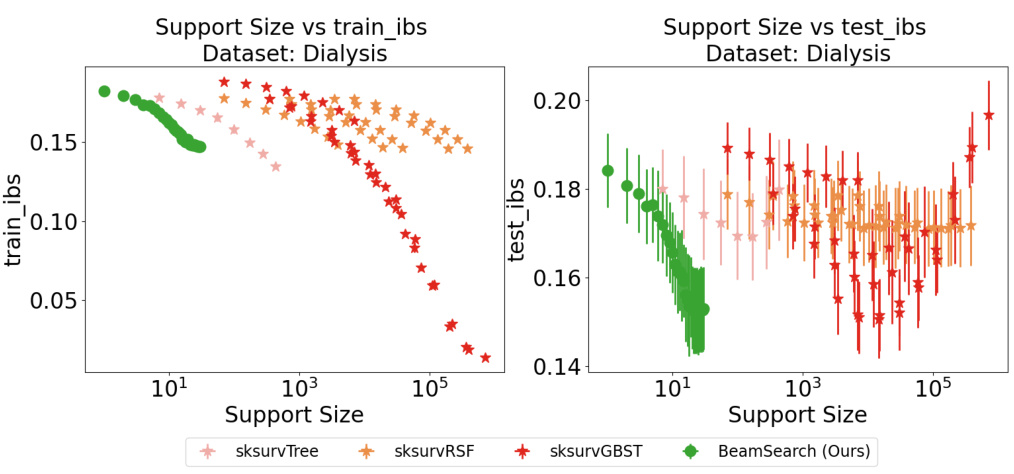

This figure compares the performance of the proposed BeamSearch method with several non-Cox models on the Dialysis dataset, using the C-index metric. The x-axis represents the support size (number of selected features), while the y-axis represents the C-index score (higher is better), a measure of a model’s ability to correctly rank survival times. Error bars indicate variability across the 5-fold cross-validation runs. The plot shows that, as support size increases, the BeamSearch method achieves a higher C-index on both training and testing sets compared to other methods, indicating superior performance in variable selection for the Cox proportional hazards model.

This figure compares the performance of different Cox proportional hazards models on the Dialysis dataset in terms of C-index. The x-axis represents the support size (number of selected features), and the y-axis represents the C-index, a measure of predictive accuracy. The plot shows that as support size increases, C-index improves for all models but the BeamSearch (Ours) model consistently outperforms baselines. The error bars depict the standard deviation across 5-fold cross-validation. This suggests that the proposed beam search method is effective for variable selection in Cox models, leading to improved performance with a sparser model.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed beam search method with other variable selection methods on three synthetic datasets with varying sample sizes. The datasets are designed to have a high correlation level between the features (p=0.9). The F1 score, which measures the accuracy of the variable selection, is used as the evaluation metric. The results show that the proposed beam search method achieves significantly better F1 scores than other methods, particularly in the datasets with larger sample sizes (1200 and 1000 samples). As the sample size decreases, the F1 scores decrease for all methods, reflecting the challenges associated with variable selection when the data is limited.

This figure compares the performance of different Cox proportional hazards models on the Dialysis dataset in terms of C-index. The x-axis represents the support size (number of features used in the model), while the y-axis shows the C-index, a measure of predictive accuracy. The plot displays the results for training and testing data, revealing how different models perform with varying levels of sparsity. The green line represents the proposed BeamSearch method.

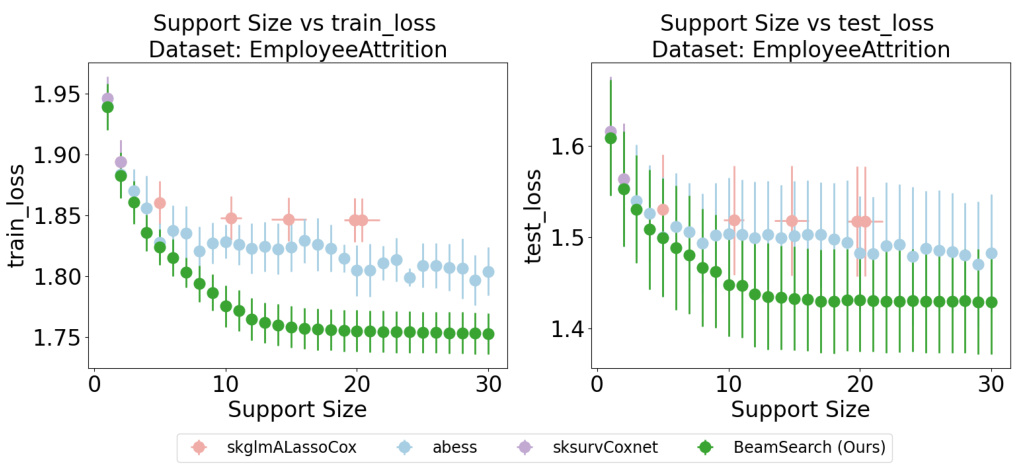

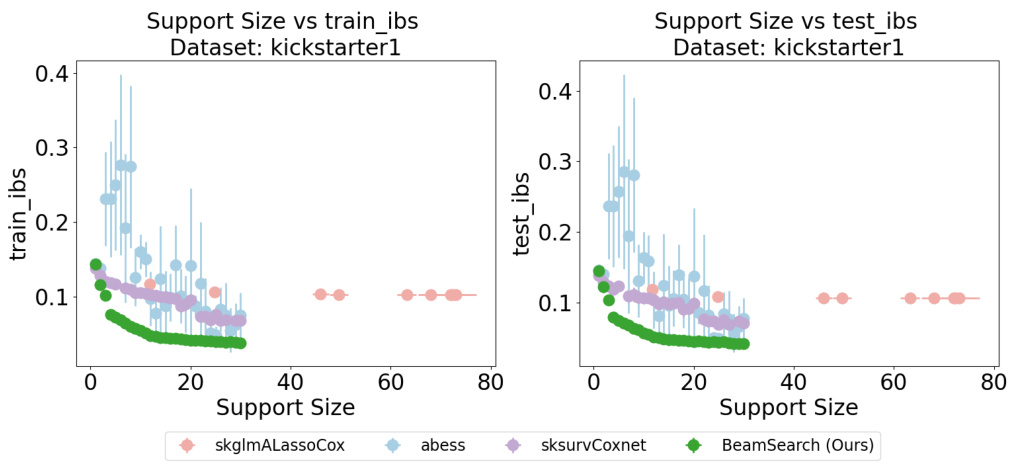

This figure displays the results of a 5-fold cross-validation experiment on the EmployeeAttrition dataset, comparing the performance of four different Cox models in terms of the C-index metric. The x-axis represents the support size (number of selected features), while the y-axis shows the C-index values. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the C-index across the five folds. The four models compared are: skglmALassoCox, abess, sksurvCoxnet, and BeamSearch (the authors’ proposed method). The figure helps illustrate the tradeoff between model sparsity (support size) and predictive performance (C-index) for each model. It is particularly useful in showing how well the BeamSearch method performs compared to other established Cox models for variable selection, especially when handling highly correlated data.

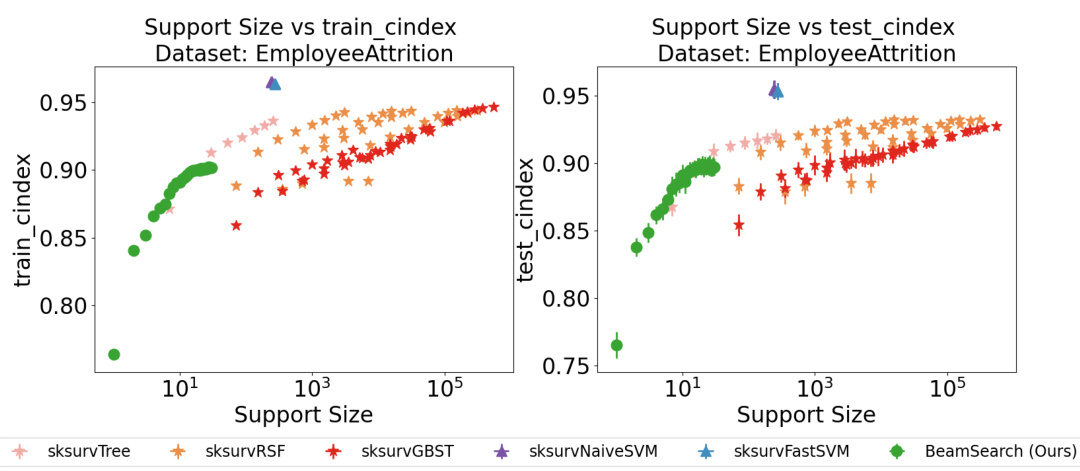

This figure compares the performance of different variable selection methods on the Employee Attrition dataset, focusing on the C-index metric. The x-axis represents the support size (number of selected features), and the y-axis shows the C-index. The plot visualizes how the C-index varies as more features are included in the model. Several different models, both Cox-based and non-Cox-based, are compared, illustrating how the new BeamSearch method compares against well-established techniques.

This figure compares the performance of different Cox proportional hazards models on the Dialysis dataset in terms of C-index. The x-axis represents the support size (number of features used in the model), and the y-axis represents the C-index score (a measure of the model’s ability to correctly rank the risk of failure for different samples). The plot shows that as support size increases, the C-index generally increases for all methods, indicating improved predictive performance. However, the BeamSearch (Ours) method appears to consistently outperform the baselines, suggesting better variable selection capabilities and potentially a more efficient model.

This figure displays the results of variable selection experiments on three synthetic datasets with high feature correlation (p=0.9). Each dataset has a different sample size (1200, 1000, and 800). The plots show the F1 score (a measure of accuracy in recovering the true relevant features) plotted against the number of selected features (support size). The results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed BeamSearch method, especially in larger datasets, highlighting its ability to accurately identify relevant features even with high correlation. As the sample size decreases, the performance of all methods degrades.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed FastSurvival method against existing optimization methods for training Cox Proportional Hazards (CPH) models. It shows the convergence speed and computational efficiency of FastSurvival on the Flchain dataset under both l₂ and l₁+l₂ regularization. The results highlight that FastSurvival maintains a monotonically decreasing loss, unlike the baseline methods that often experience loss explosion. The superior efficiency is attributed to the cost of each iteration being linearly proportional to the sample size (O(n)).

This figure compares the performance of different Cox proportional hazards models on the Dialysis dataset in terms of C-index, a metric for evaluating the discriminatory ability of survival models. The models compared include skglmALassoCox, abess, sksurvCoxnet, and BeamSearch (the authors’ proposed method). The x-axis represents the number of features (support size) used in the model, and the y-axis shows the C-index for both training and test sets. The plot helps demonstrate the trade-off between model sparsity (number of features) and prediction accuracy.

The figure shows the results of a 5-fold cross-validation experiment on the Dialysis dataset. The experiment compares the performance of several Cox proportional hazards models, including the authors’ proposed BeamSearch method, across different support sizes (number of selected features). The metric used to evaluate performance is the Concordance Index (CIndex), a measure of how well the model ranks observations according to their risk of experiencing an event (e.g. death). The plots show both the training CIndex and test CIndex for each model and support size. The goal is to assess how the performance of each method varies as the number of selected features changes.

This figure compares the performance of different Cox proportional hazards models on the Dialysis dataset using 5-fold cross-validation. The metric used to evaluate performance is the concordance index (C-index), which measures the ability of the model to correctly rank the survival times of two randomly selected individuals. The x-axis represents the support size (number of features included in the model), and the y-axis shows the C-index. The figure shows that our proposed BeamSearch method generally achieves higher C-index scores (better performance) with smaller support sizes compared to other Cox models such as skglmALassoCox, abess, and sksurvCoxnet.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed beam search method with other methods for variable selection on synthetic datasets with high feature correlation. The x-axis shows the support size (number of selected features), and the y-axis shows the F1 score, a metric representing the accuracy of feature selection. The results demonstrate that the proposed beam search method significantly outperforms other methods, achieving perfect recovery of the true features (F1 score = 1.0) on datasets with larger sample sizes (1200, 1000). As the sample size reduces to 800, the F1 score decreases for all methods, but the proposed method maintains better performance than the baselines.

This figure compares the performance of different Cox proportional hazards models on the Dialysis dataset using 5-fold cross-validation. The metric used is the concordance index (C-index), which measures the ability of the model to correctly rank pairs of observations based on their predicted risk of experiencing an event (in this case, likely death or some failure related event). The x-axis represents the support size (the number of features used in the model), and the y-axis represents the C-index. It visualizes the trade-off between model sparsity (fewer features, smaller support size) and predictive accuracy (higher C-index). The lines likely represent mean values, and the error bars indicate variability (e.g. standard deviation) across the folds.

Full paper#