↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

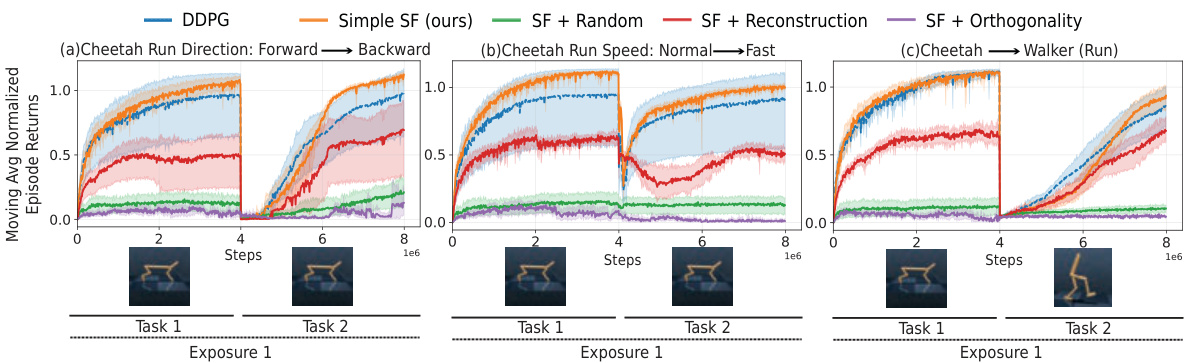

TL;DR#

Deep reinforcement learning (RL) often struggles with continual learning due to catastrophic forgetting and interference. Successor Features (SFs) offer a solution by disentangling reward and dynamics, but learning them from raw pixels often leads to representation collapse, where the model fails to capture meaningful variations. Existing SF learning methods can avoid this problem, but they involve complex losses and multiple training phases, reducing efficiency.

This paper introduces a simple method to learn SFs directly from pixels by using a combination of Temporal-Difference (TD) and reward prediction loss functions. This approach matches or outperforms existing SF learning methods in various 2D and 3D maze, as well as Mujoco environments. Importantly, it avoids representation collapse and is computationally efficient. This offers a new, streamlined technique for learning SFs from pixels, which is highly relevant to modern artificial intelligence and continual learning research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in deep reinforcement learning (RL) and continual learning. It offers a novel, efficient solution to a persistent challenge—representation collapse in Successor Feature learning— paving the way for more robust and adaptable RL agents in dynamic environments. The simple yet effective method introduced is highly relevant to current trends in continual and efficient RL research, opening exciting new avenues for future investigations.

Visual Insights#

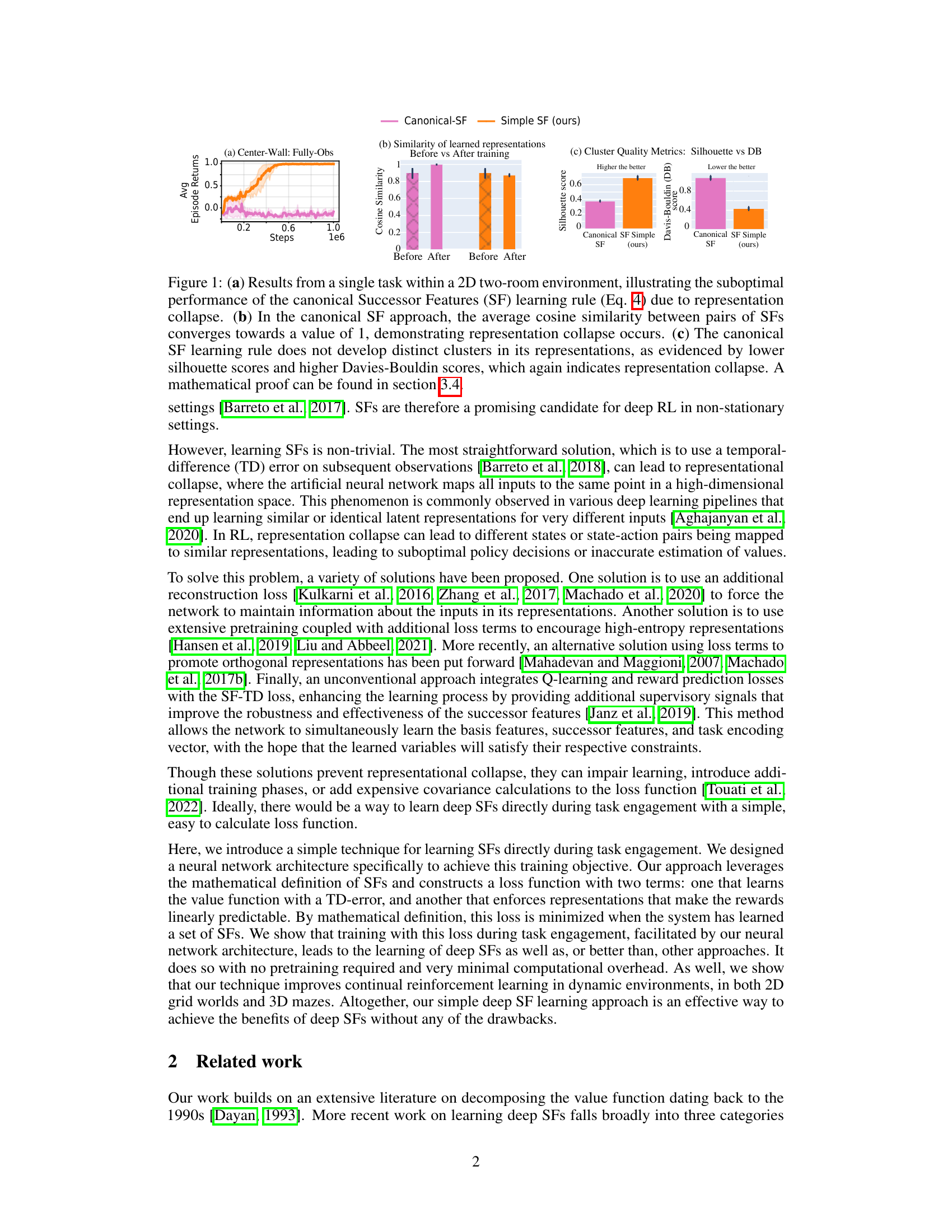

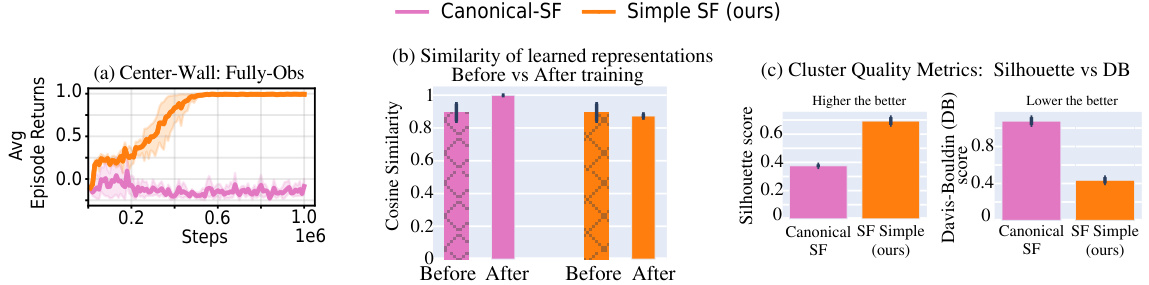

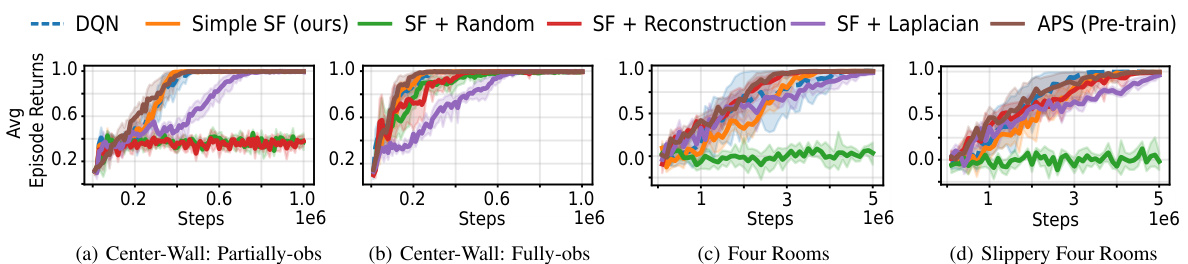

This figure demonstrates the limitations of the canonical Successor Feature learning approach, which suffers from representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a simple 2D environment, while panels (b) and (c) provide further evidence of the collapse using cosine similarity and cluster quality metrics.

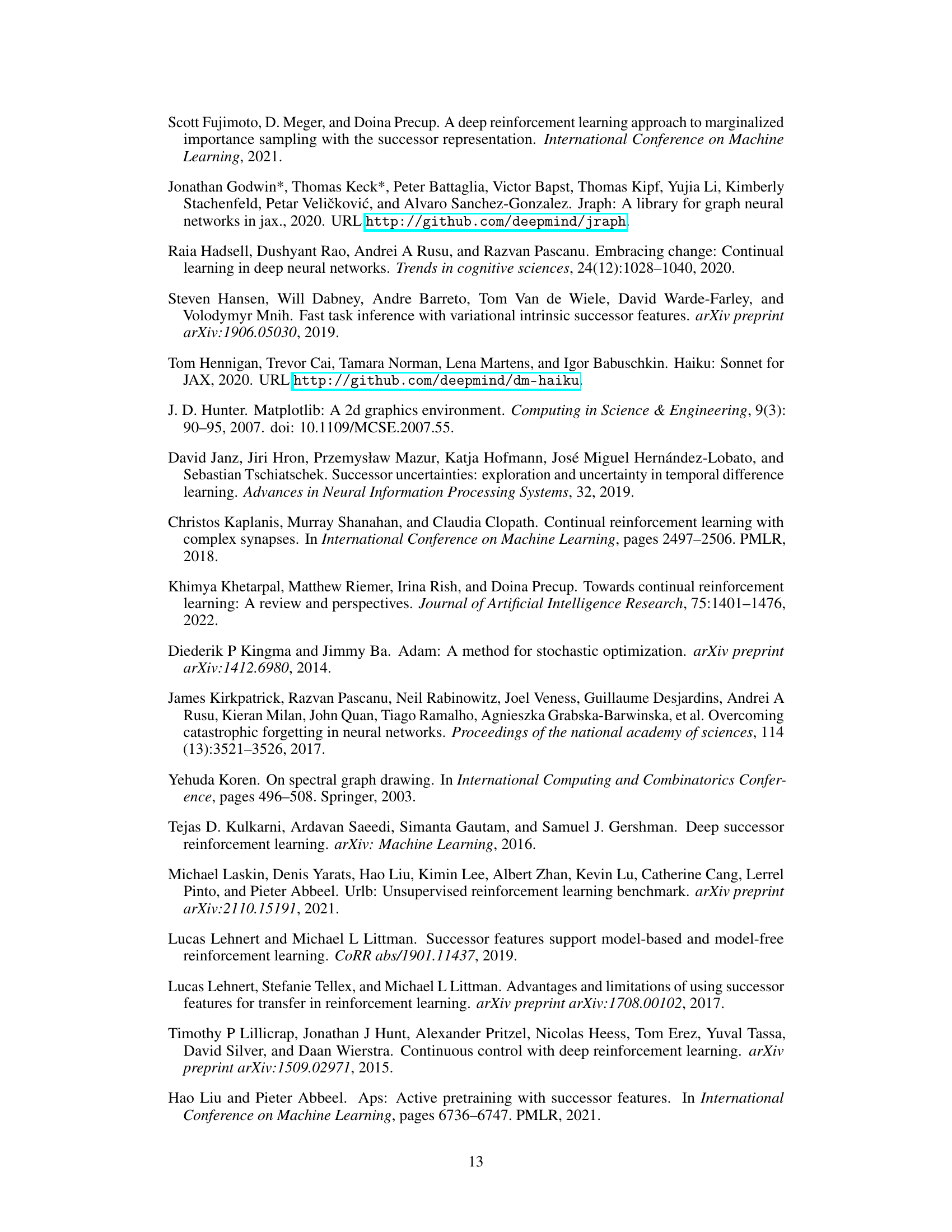

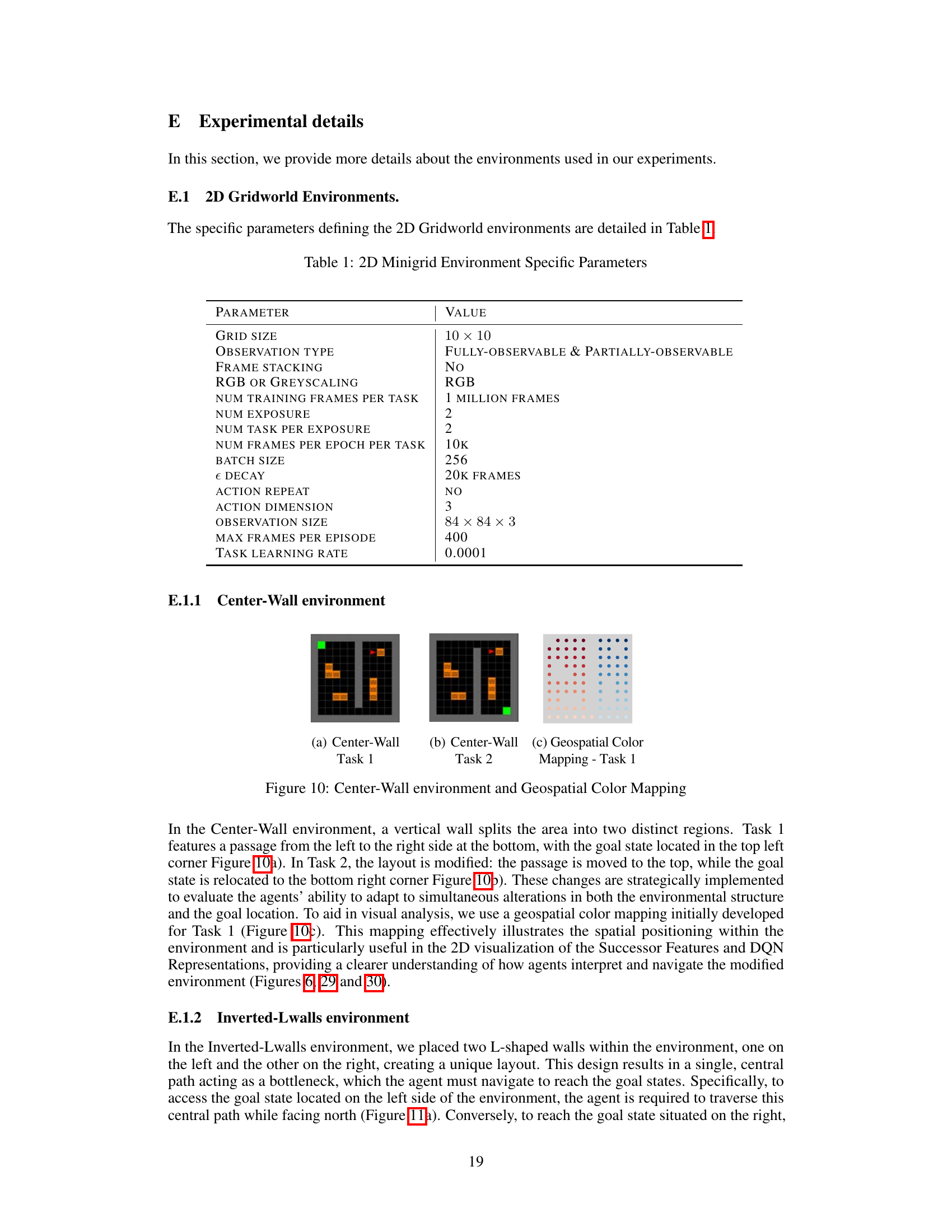

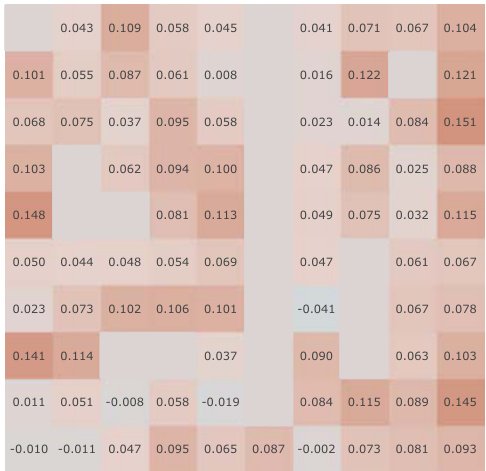

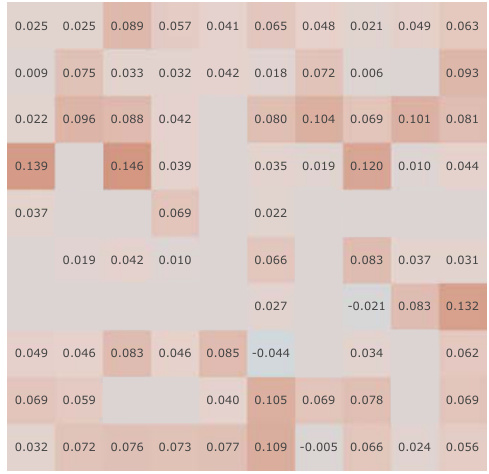

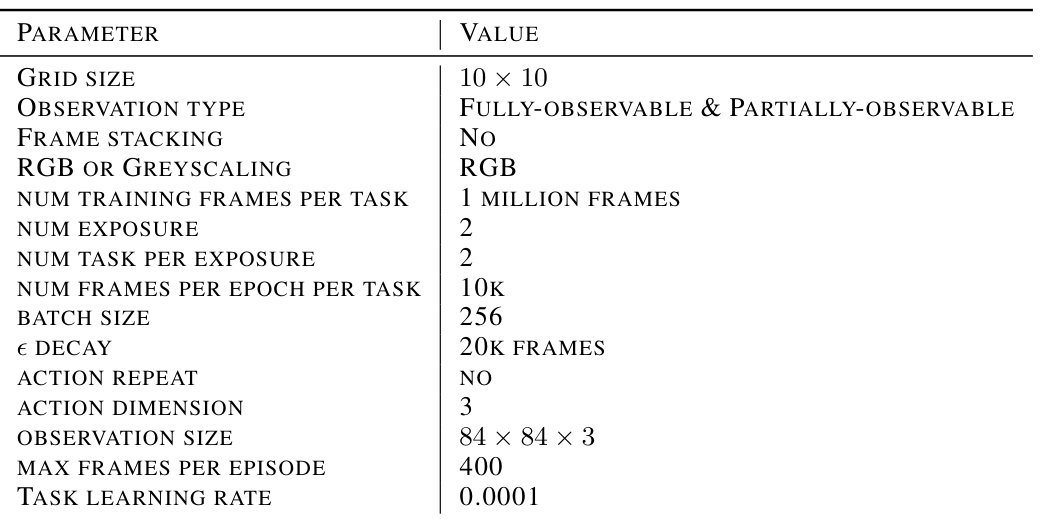

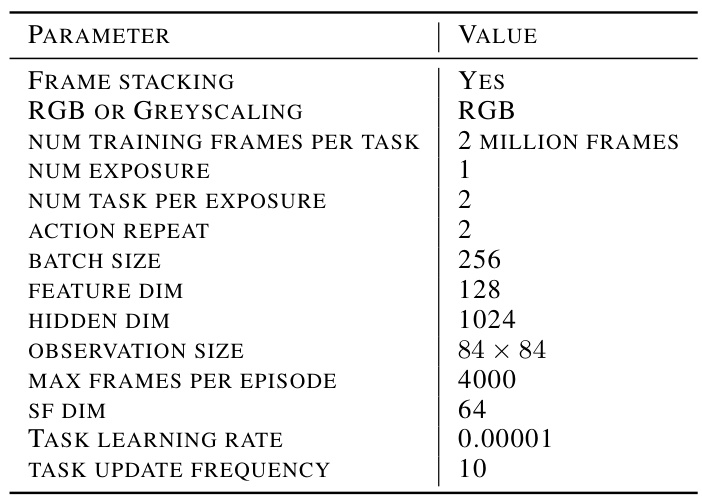

This table lists the specific parameters used to configure the 2D Minigrid environments for the experiments. The parameters include details about the grid size, observation type (fully-observable or partially-observable), whether frame stacking was used, the color scheme (RGB or grayscale), the number of training frames per task, the number of exposures, the number of tasks per exposure, the number of frames per epoch per task, the batch size, epsilon decay schedule, whether action repeat was used, the dimensionality of actions and observations, the maximum frames per episode, the task learning rate, and the epsilon decay rate.

In-depth insights#

SF Learning#

Successor Feature (SF) learning tackles the challenge of learning representations in reinforcement learning that are robust to non-stationary environments. Traditional methods often suffer from representation collapse, where the network fails to distinguish between meaningful variations in the data, leading to suboptimal performance. The paper explores various SF learning approaches, emphasizing the importance of avoiding representation collapse through techniques like reconstruction losses or promoting orthogonality among representations. A novel, simple method is proposed that learns SFs directly from pixel-level observations, which is shown to be efficient and effective across various environments. This method contrasts with previous approaches which often include complex losses and multiple learning phases. The paper’s focus on efficiency and straightforwardness in learning highlights the potential of deep SFs to improve the robustness of deep reinforcement learning agents. The simplicity and effectiveness of the proposed method suggest a significant advancement in the field, offering a streamlined technique for deep SF learning without pre-training.

Simple Deep SFs#

The concept of “Simple Deep SFs” suggests a streamlined approach to learning Successor Features (SFs) in deep reinforcement learning. This method likely contrasts with existing techniques by avoiding complex loss functions and multiple learning phases, thus enhancing efficiency. The “simple” aspect might involve a more straightforward loss function, possibly a combination of Temporal Difference (TD) error and reward prediction error, directly minimizing the mathematical definition of SFs. The “deep” aspect points to the use of deep neural networks to learn these features directly from high-dimensional pixel inputs, eliminating the need for pre-training or handcrafted feature extraction. This direct learning from pixels is a key advantage, overcoming representational collapse, a common issue in SF learning methods. The overall goal is to achieve the benefits of SFs (improved generalization and adaptation to non-stationary environments) in a more efficient and easily implementable way.

Continual Learning#

Continual learning, a crucial aspect of artificial intelligence, focuses on developing systems that can continuously learn and adapt without catastrophic forgetting. The challenge lies in maintaining previously acquired knowledge while simultaneously learning new information. This is especially relevant in dynamic, real-world environments where the underlying data distribution or task definition changes over time. The research paper delves into this challenge by exploring how successor features (SFs), a powerful representation learning technique, can enhance continual learning. Successor features have been shown to be robust to changes in reward functions and transition dynamics, making them an attractive tool for tackling the problem of catastrophic forgetting. However, challenges remain in learning SFs directly from high-dimensional data like pixel observations where representation collapse often occurs. The paper’s innovative method offers a promising solution, proposing a streamlined approach to learn SFs efficiently, and directly from pixels, matching or exceeding current state-of-the-art performance in diverse continual learning benchmarks.

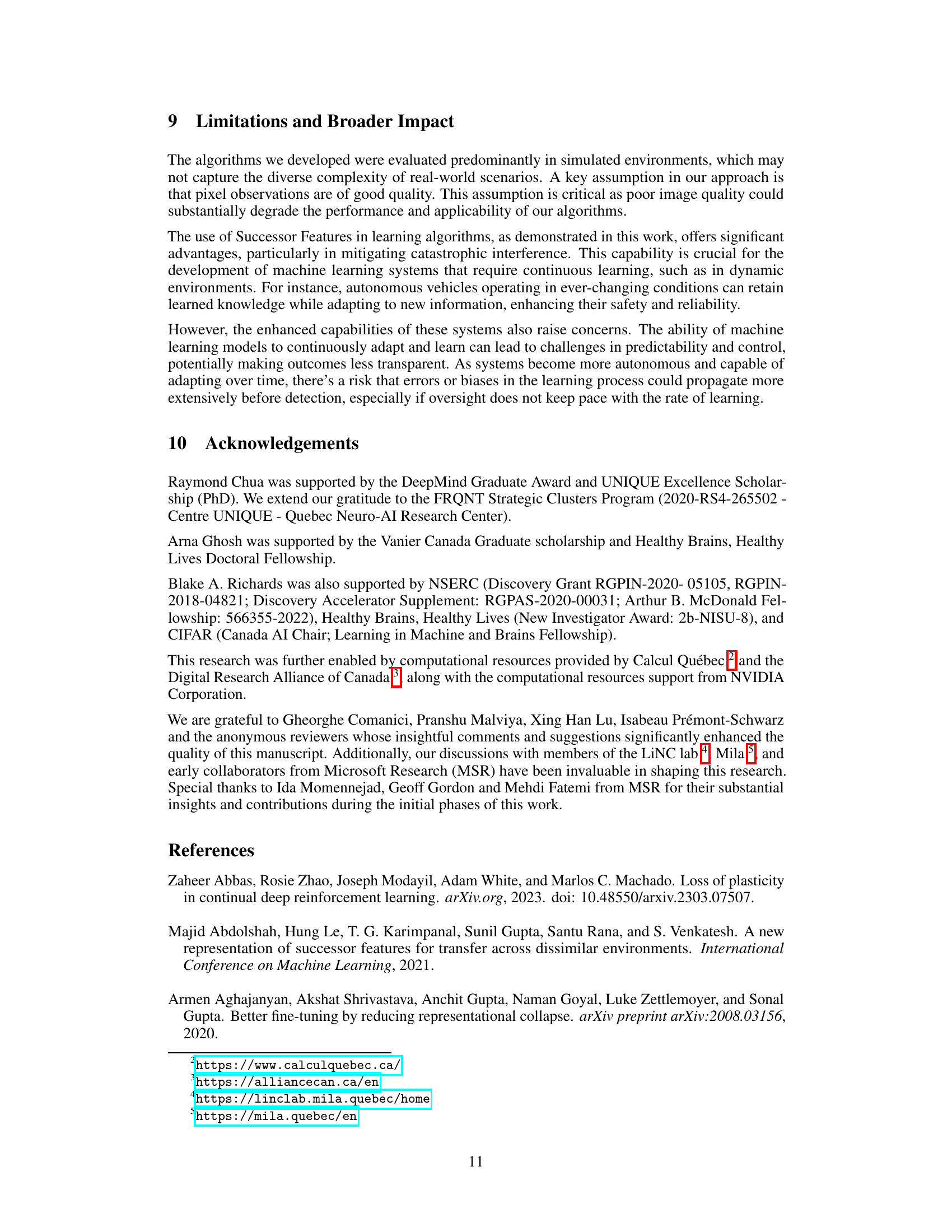

Efficiency Analysis#

An efficiency analysis of a machine learning model, especially in a resource-intensive field like deep reinforcement learning, is crucial. It should go beyond simply stating faster training times. A thorough analysis would compare the computational cost (measured by factors such as training time, memory usage, and inference speed) of the proposed method against existing state-of-the-art techniques. The analysis must show a clear advantage, not just a general improvement. Key performance indicators (KPIs) like steps to reach a policy exceeding a performance threshold, frames per second during training, and total training duration provide a more comprehensive evaluation than simply stating ‘faster’. Additionally, the analysis should investigate if the increased efficiency comes at the cost of reduced performance on the actual task. For instance, reducing the number of parameters could increase speed, but might affect generalization or accuracy. Finally, scalability analysis should be included, evaluating how the proposed method performs with larger datasets or more complex environments. A strong efficiency analysis highlights the practical impact of the model, showcasing its applicability beyond benchmarks.

Limitations#

A critical analysis of the limitations section of a research paper should delve into the methodological constraints, exploring factors like sample size, data quality, generalizability of findings to other contexts, and the reliance on specific models or algorithms. Addressing potential biases inherent in the data or methodology is crucial, acknowledging the impact of these biases on the study’s conclusions. Furthermore, a comprehensive review will discuss any limitations regarding the scope of the research, such as restricted time periods, geographical areas, or participant demographics. Technological limitations should also be analyzed, detailing any constraints imposed by software, hardware, or computational resources and their influence on the overall outcomes. Finally, unforeseen circumstances impacting data collection or analysis, like participant drop-out or unexpected technological issues, should be honestly acknowledged. A thorough evaluation of these points enhances the rigor and credibility of the research by fully disclosing the study’s boundary conditions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

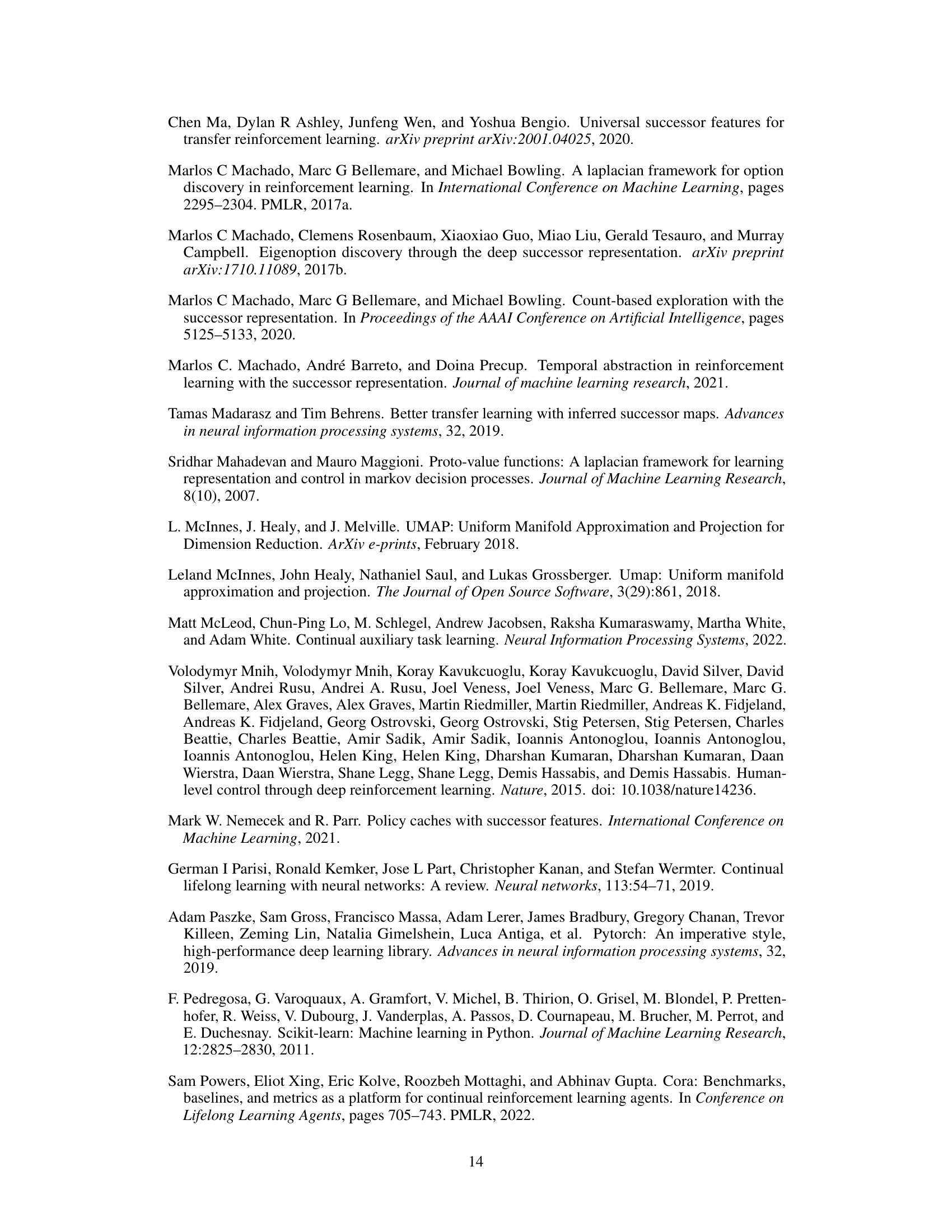

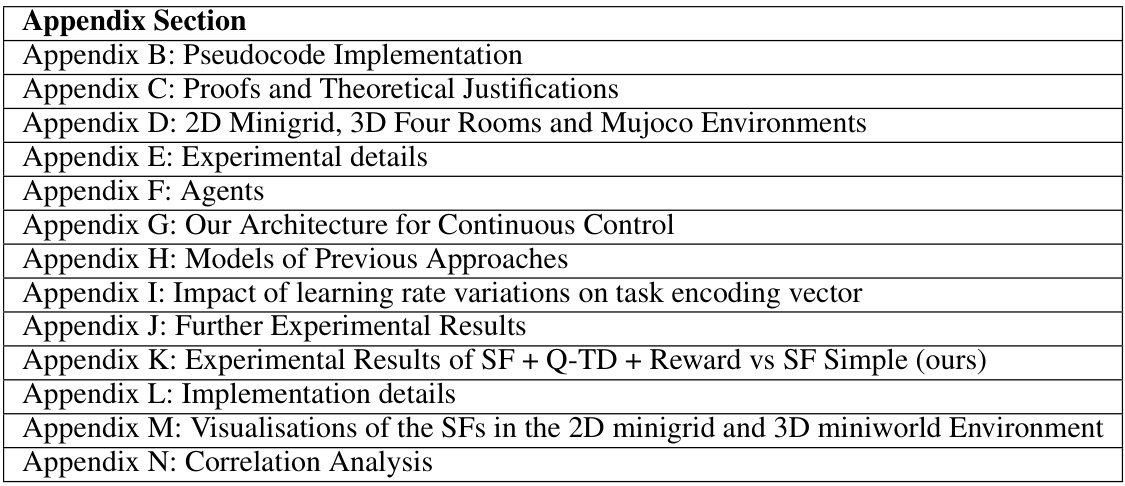

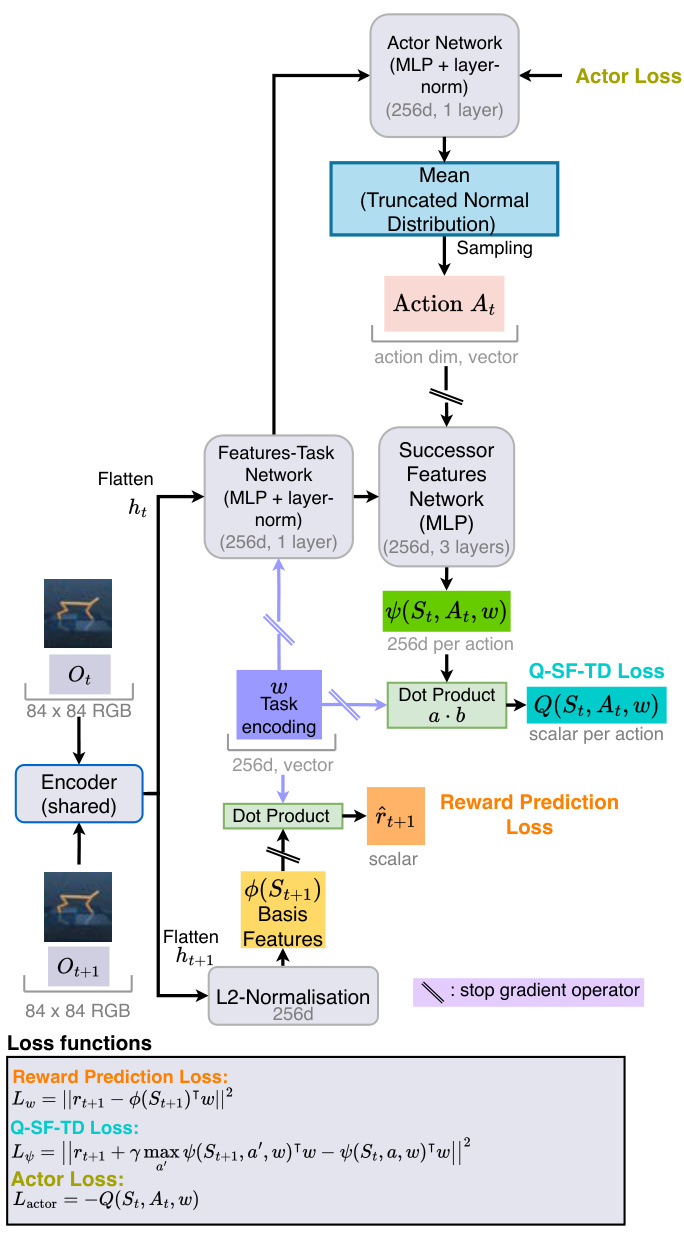

This figure shows the architecture of the proposed model for learning successor features. It uses a shared encoder to process pixel observations and generate latent representations. These representations are then used to compute both the basis features and the successor features. The model also learns a task encoding vector through reward prediction loss and minimizes Q-SF-TD loss to learn the successor features and Q-values. The figure includes a schematic showing how the components are connected and how the losses are computed.

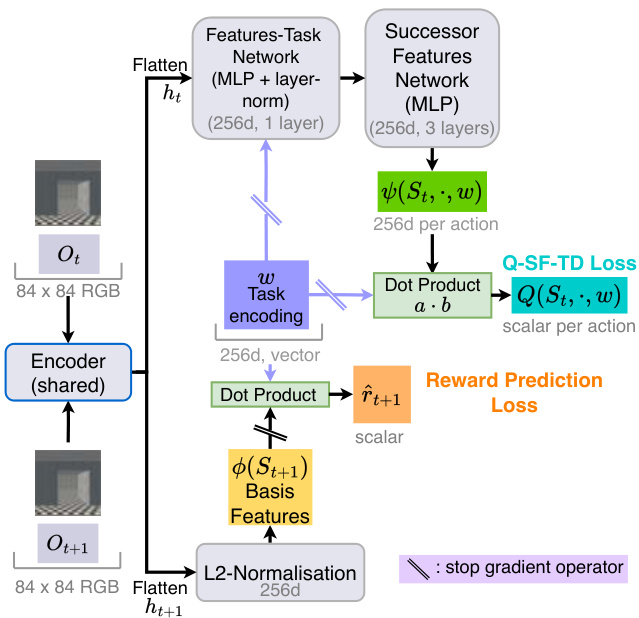

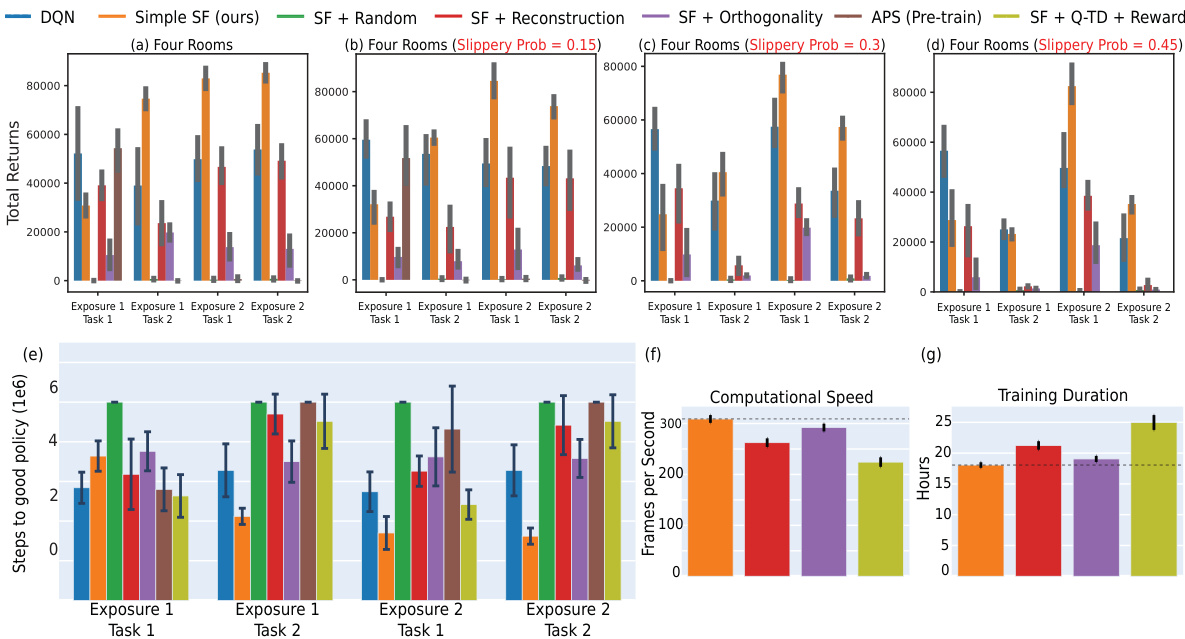

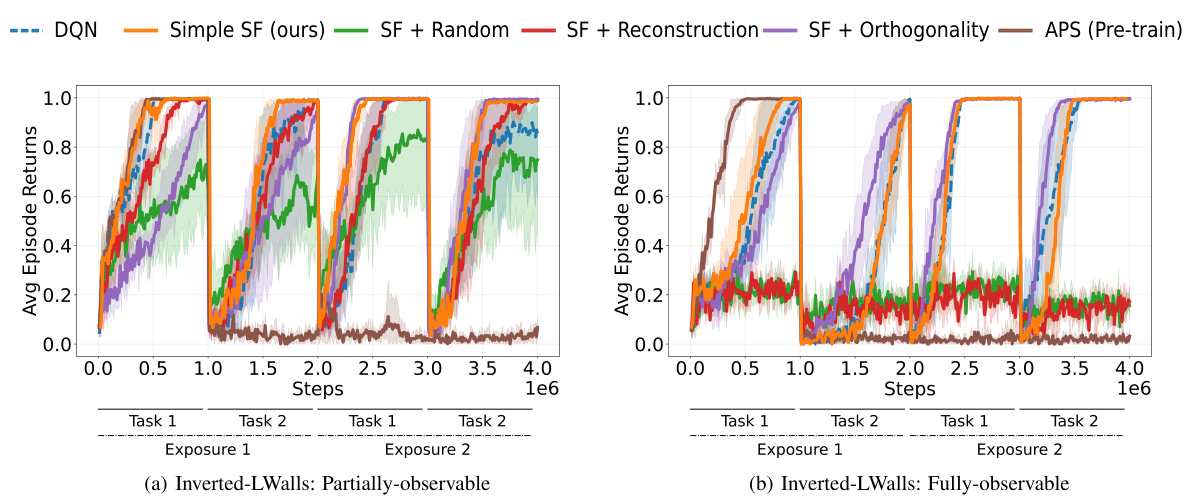

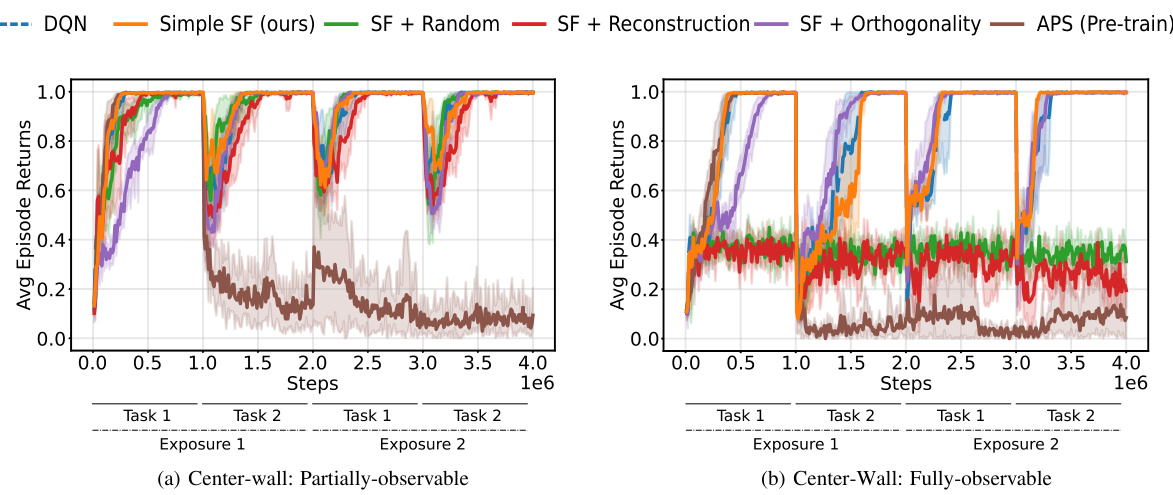

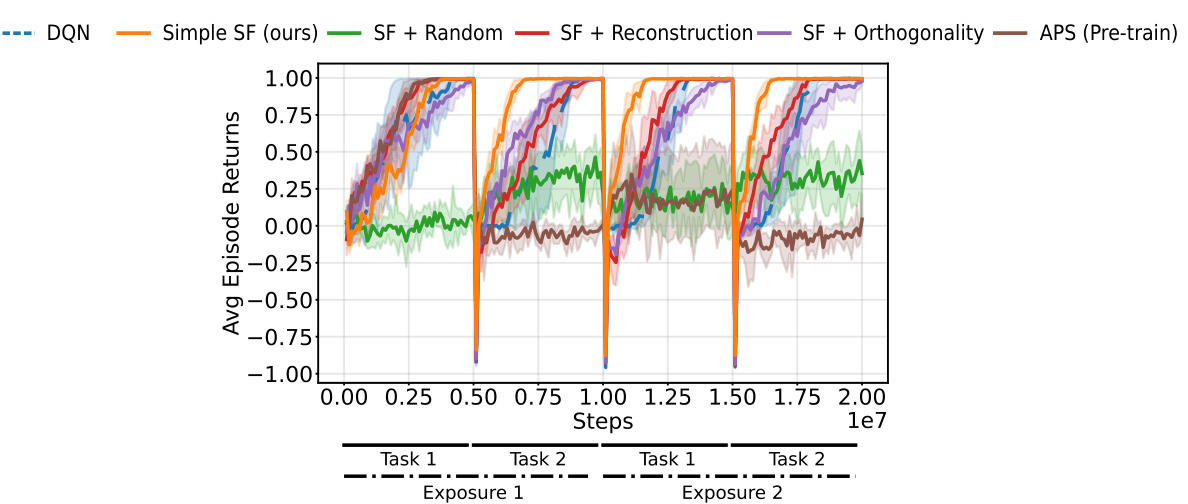

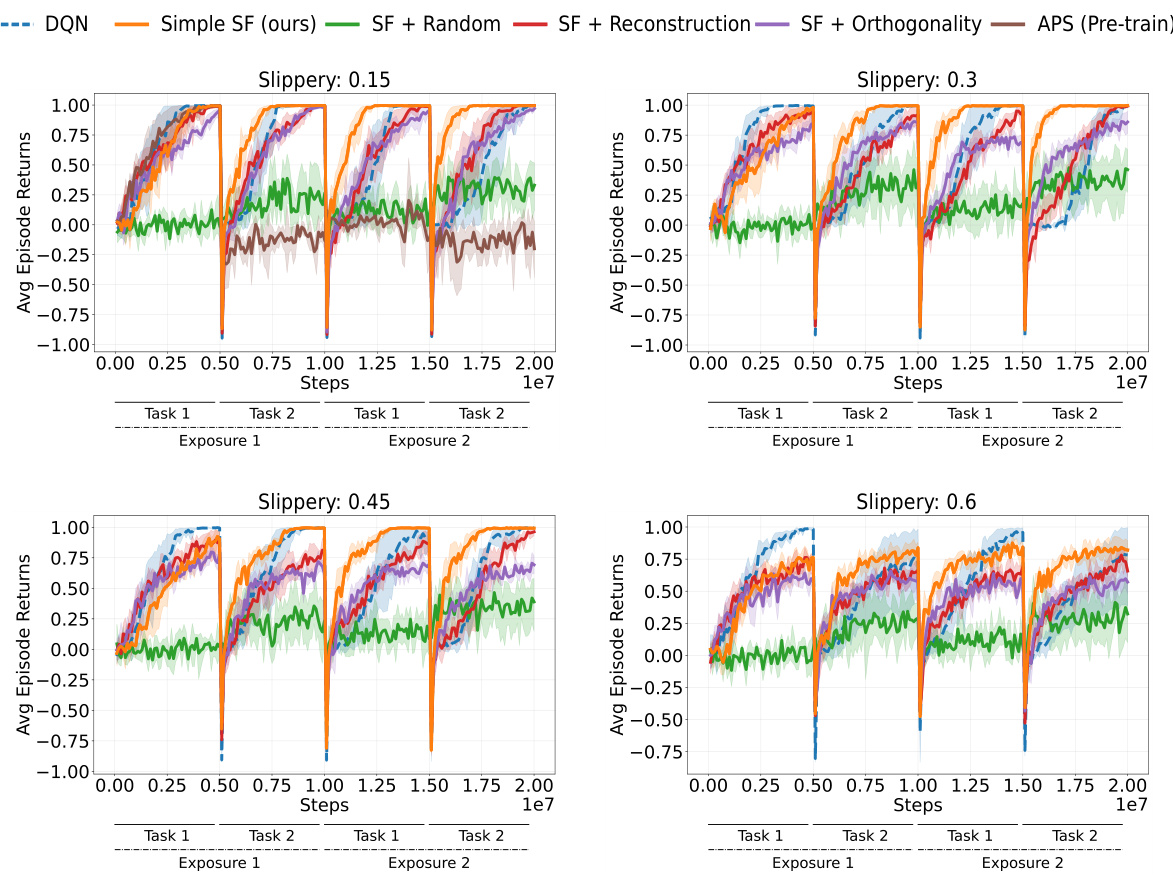

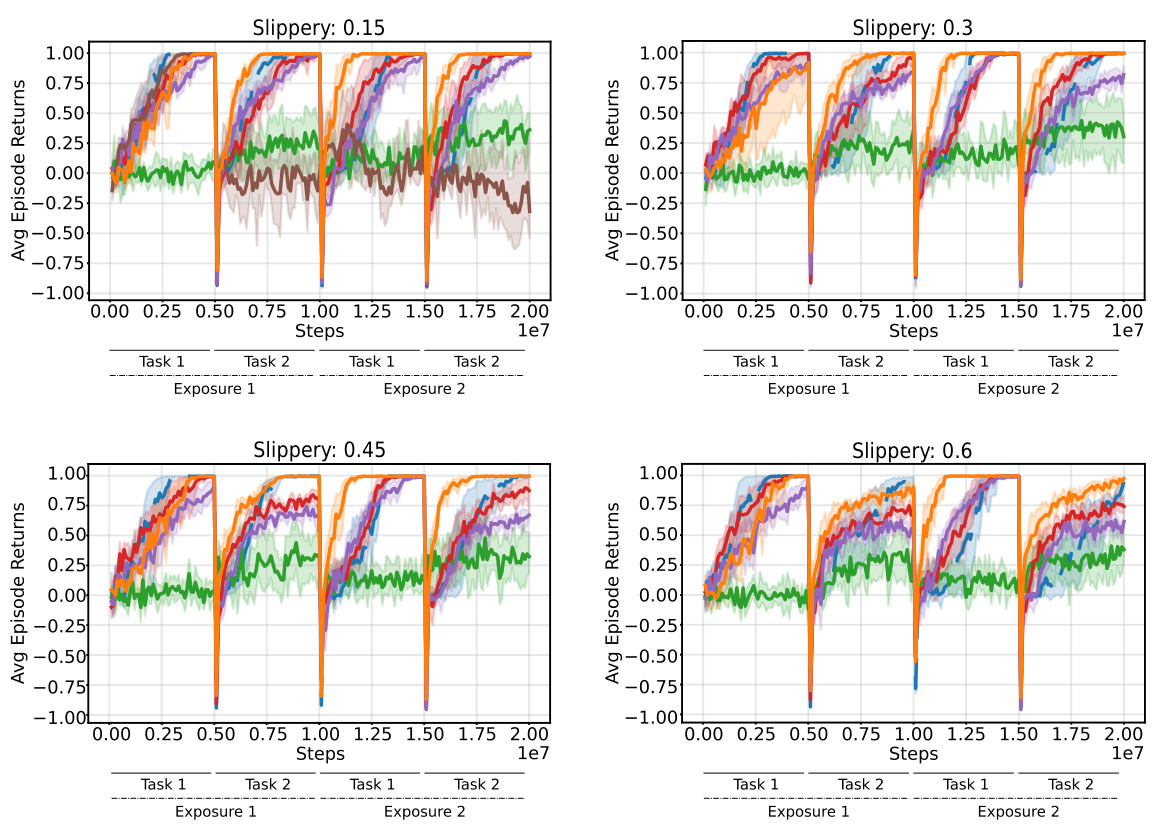

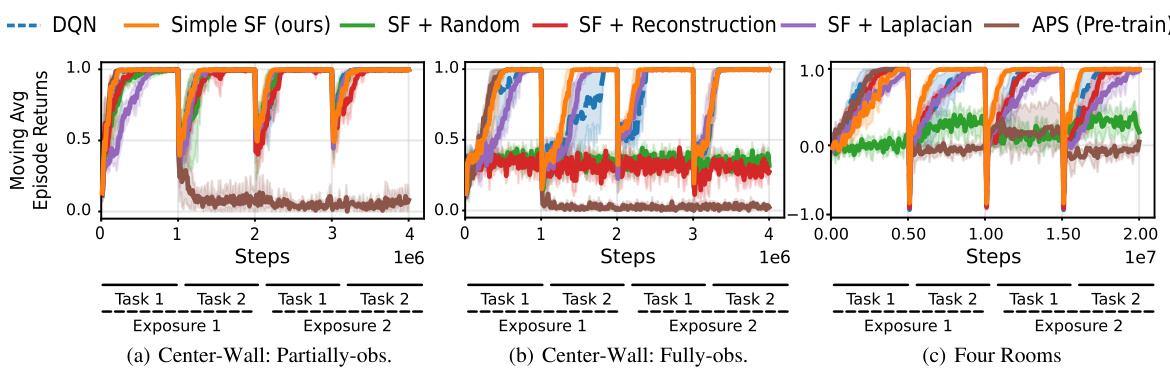

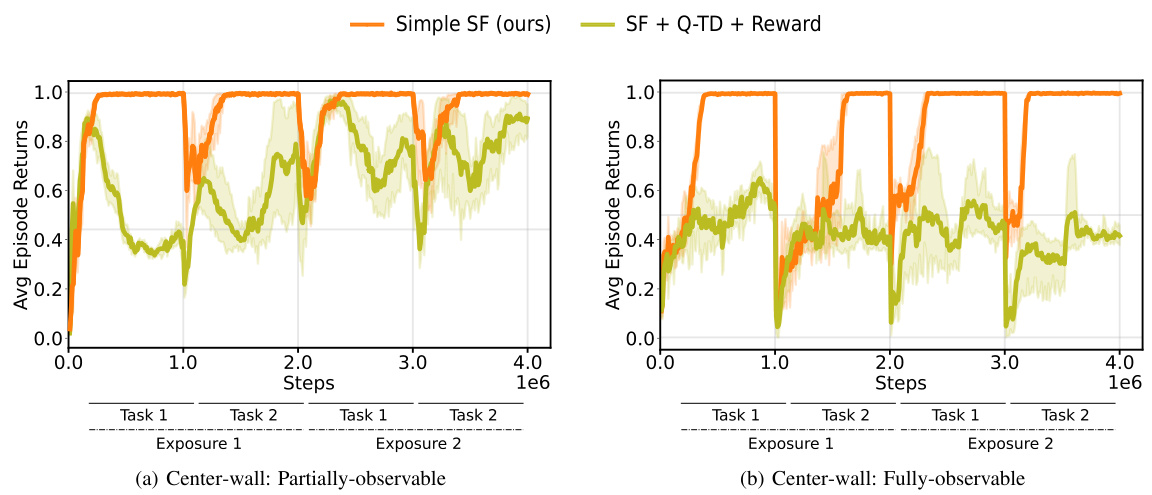

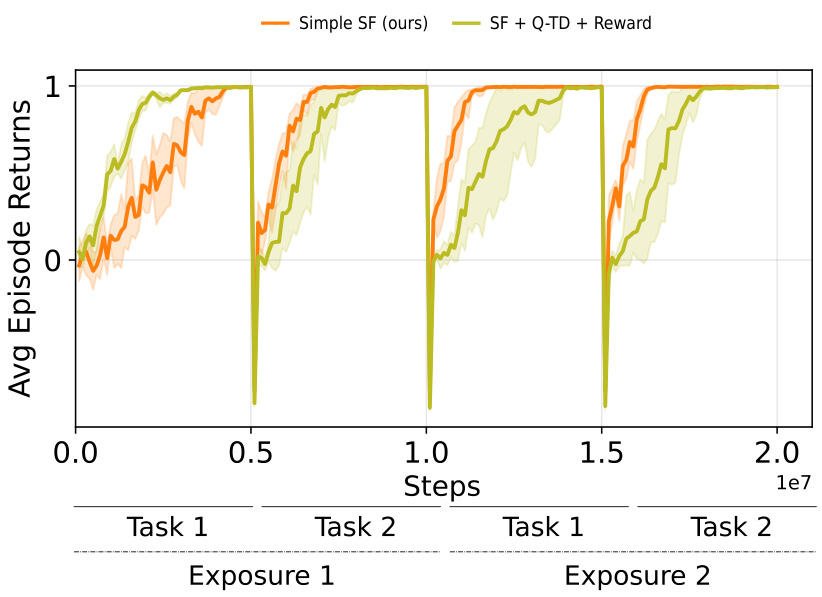

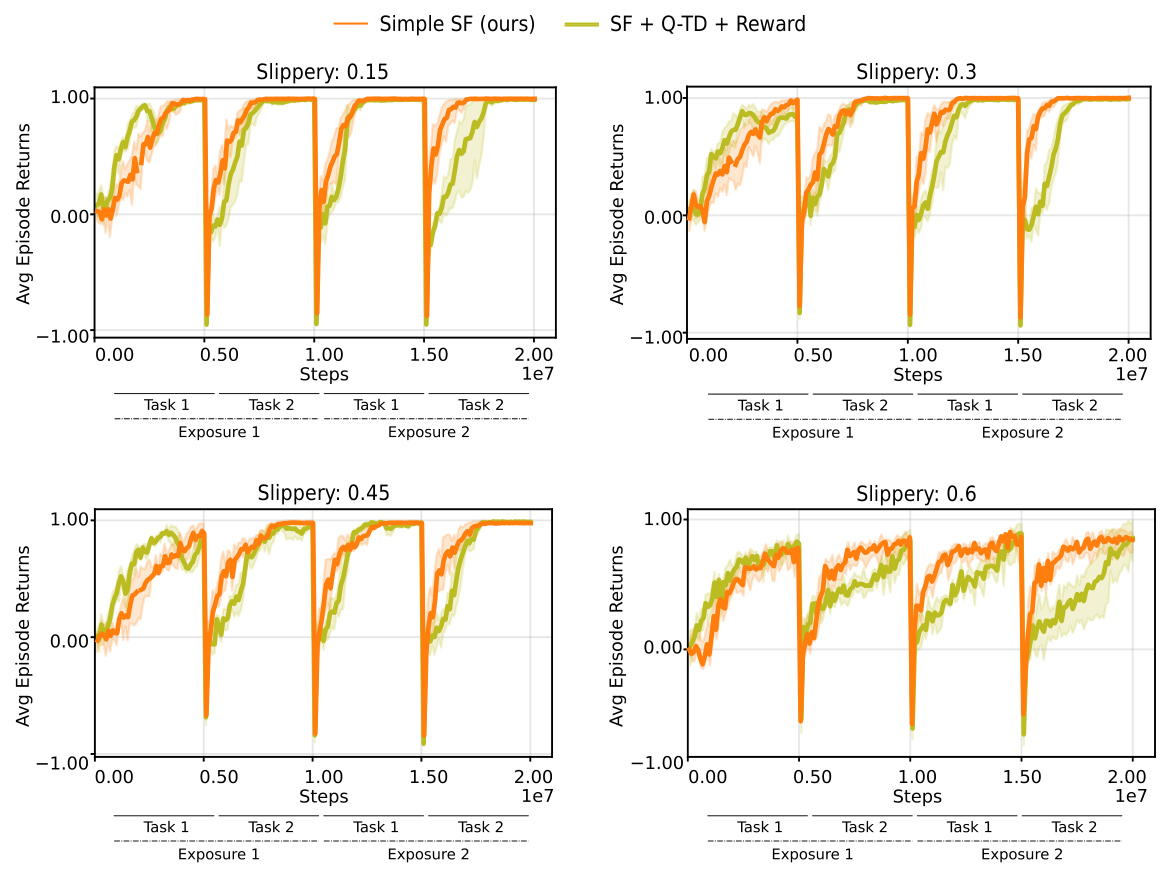

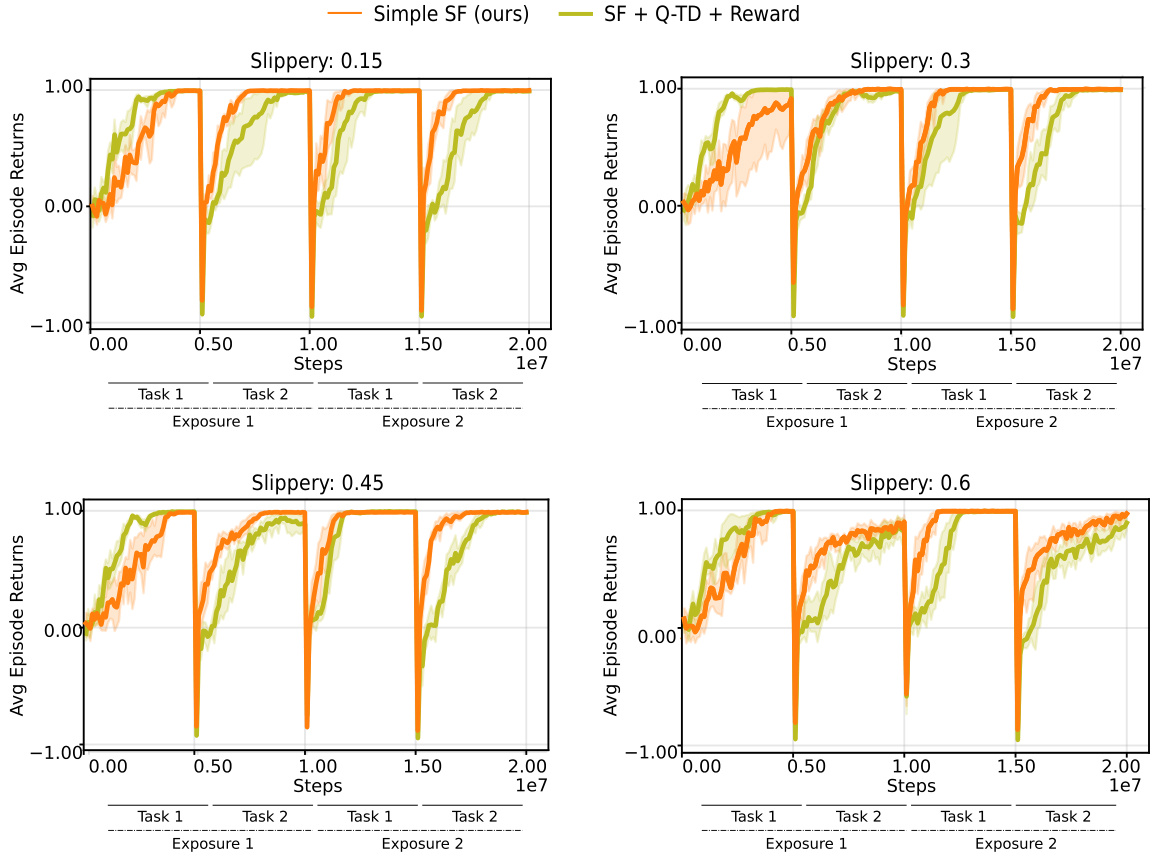

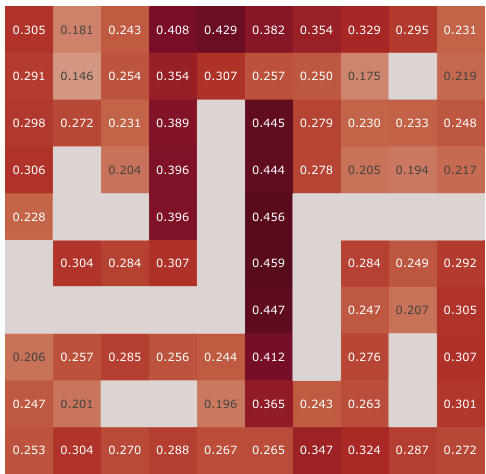

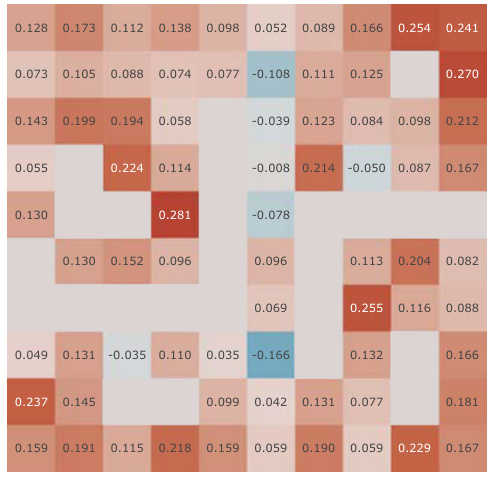

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using three different environments: 2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms (egocentric and allocentric views), and 3D Four Rooms (egocentric view). The experiments test the agents’ ability to learn and transfer knowledge across two tasks, with each task being repeated twice (Exposure 1 and 2). The key finding is that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ approach (orange bars) significantly outperforms the other methods, especially in the later tasks, highlighting its superior transfer learning capabilities and resilience to the negative impact of constraints on basis features.

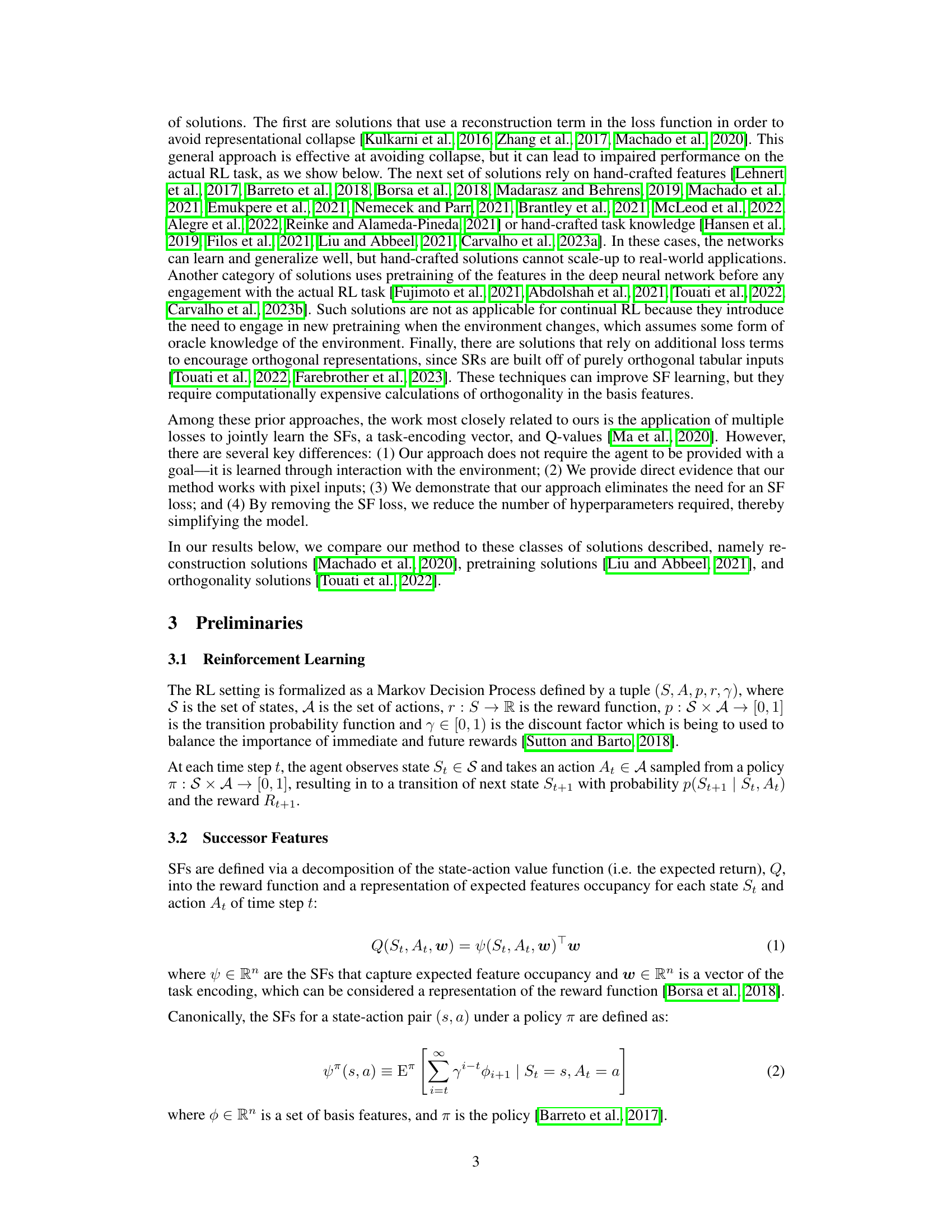

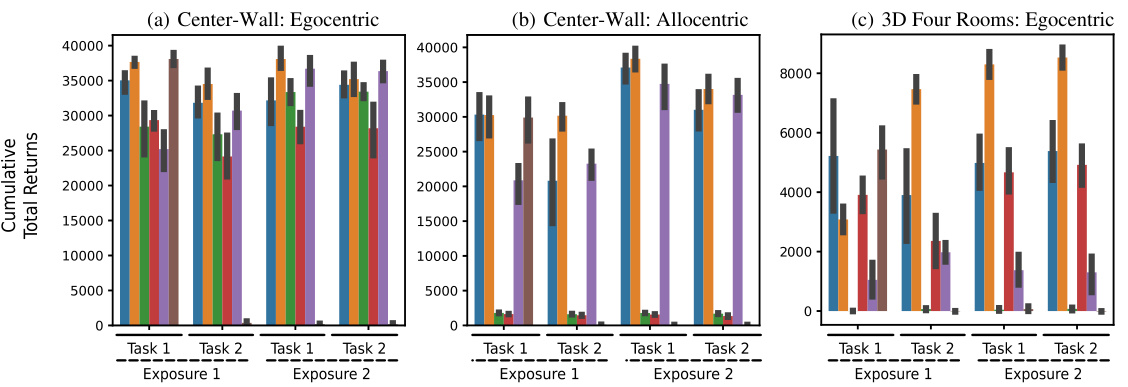

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments in the Mujoco environment using pixel observations. Three different scenarios are tested: changing the direction of running, increasing the speed of running and changing the agent’s model from a half-cheetah to a walker. The results demonstrate the Simple SF’s (the authors’ method) ability to adapt to these significant environmental changes, consistently outperforming baseline methods which struggle to adapt.

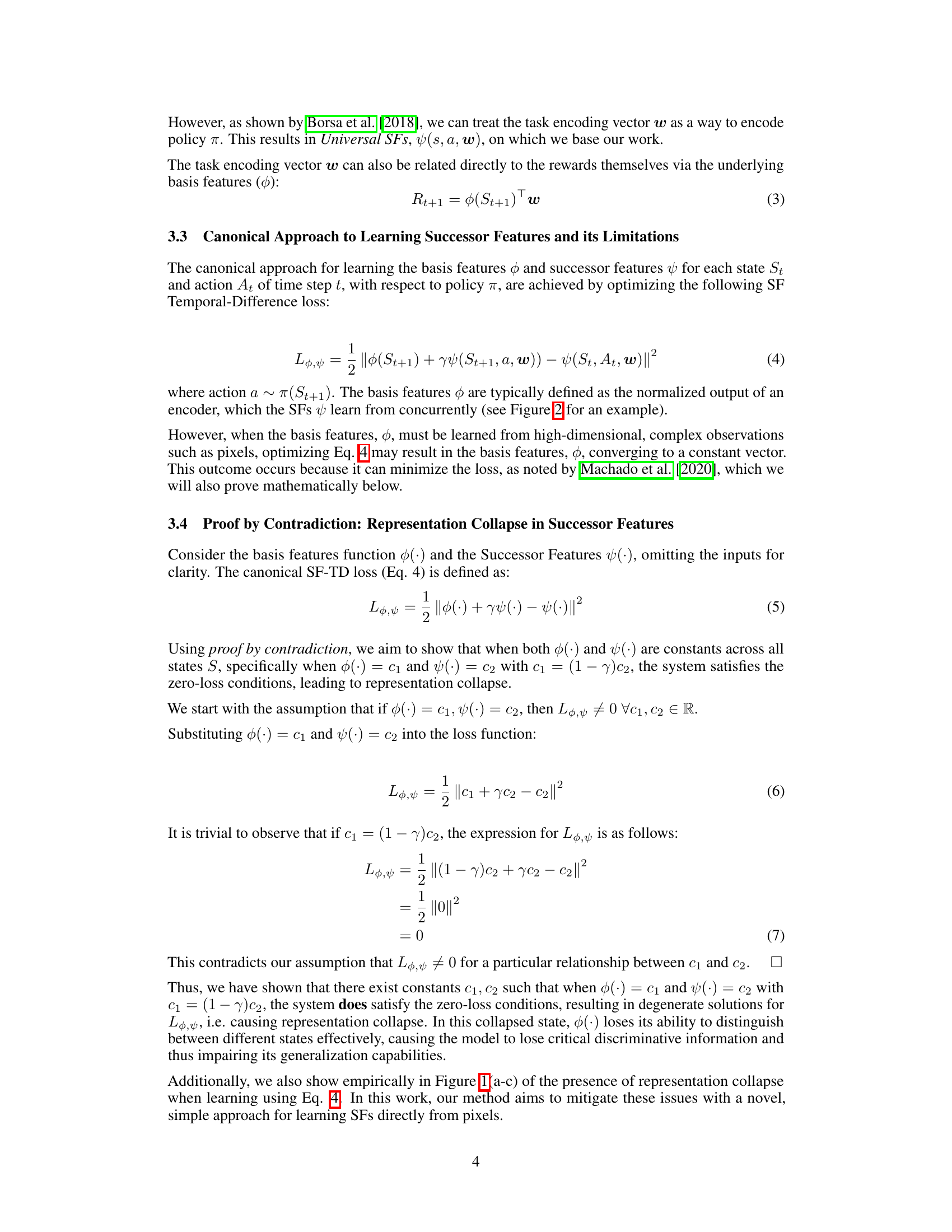

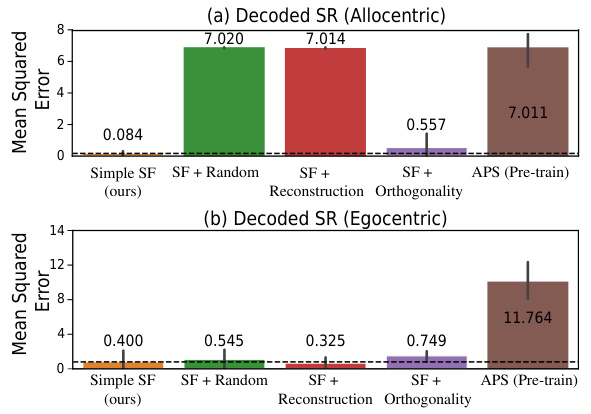

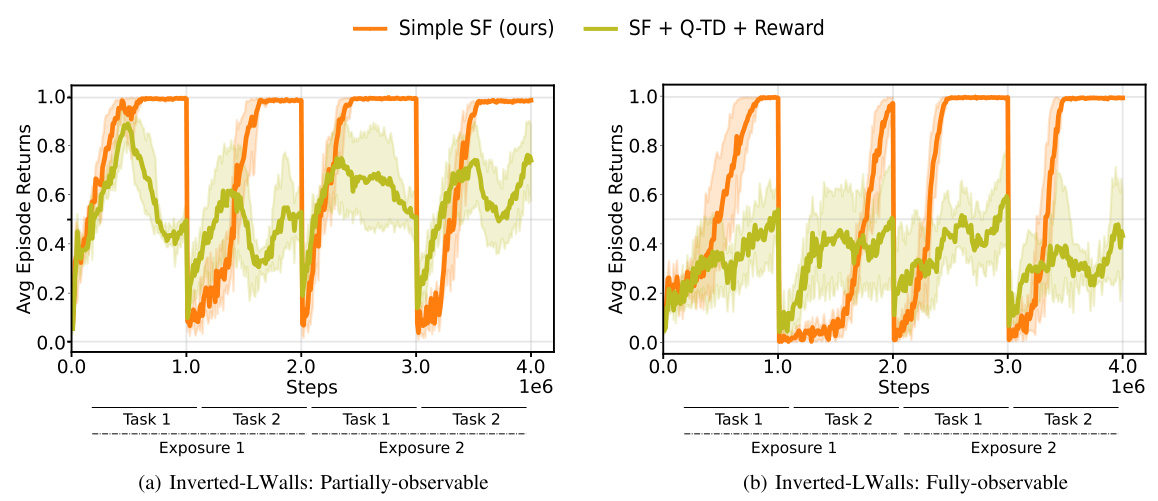

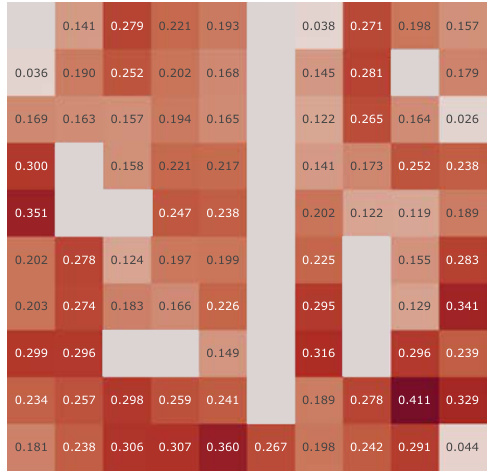

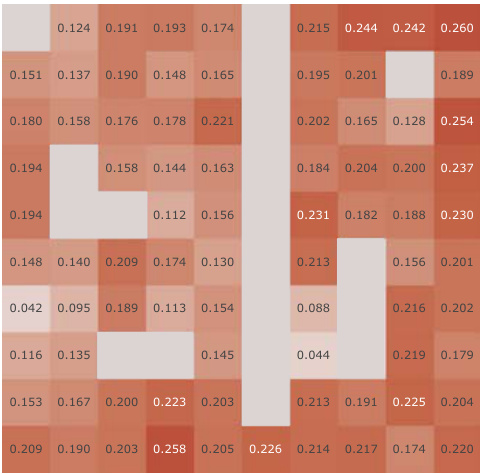

This figure shows the result of decoding the learned Successor Features (SFs) into Successor Representations (SRs) using a non-linear decoder. The Mean Squared Error (MSE) is used to quantify the difference between the decoded SRs and the analytically computed ground truth SRs. Lower MSE values indicate that the SFs better capture the transition dynamics of the environment. The figure compares the performance of different SF learning methods, including the proposed Simple SF method and several baselines (SF + Random, SF + Reconstruction, SF + Orthogonality, and APS (Pre-train)). The results are shown separately for allocentric and egocentric observations.

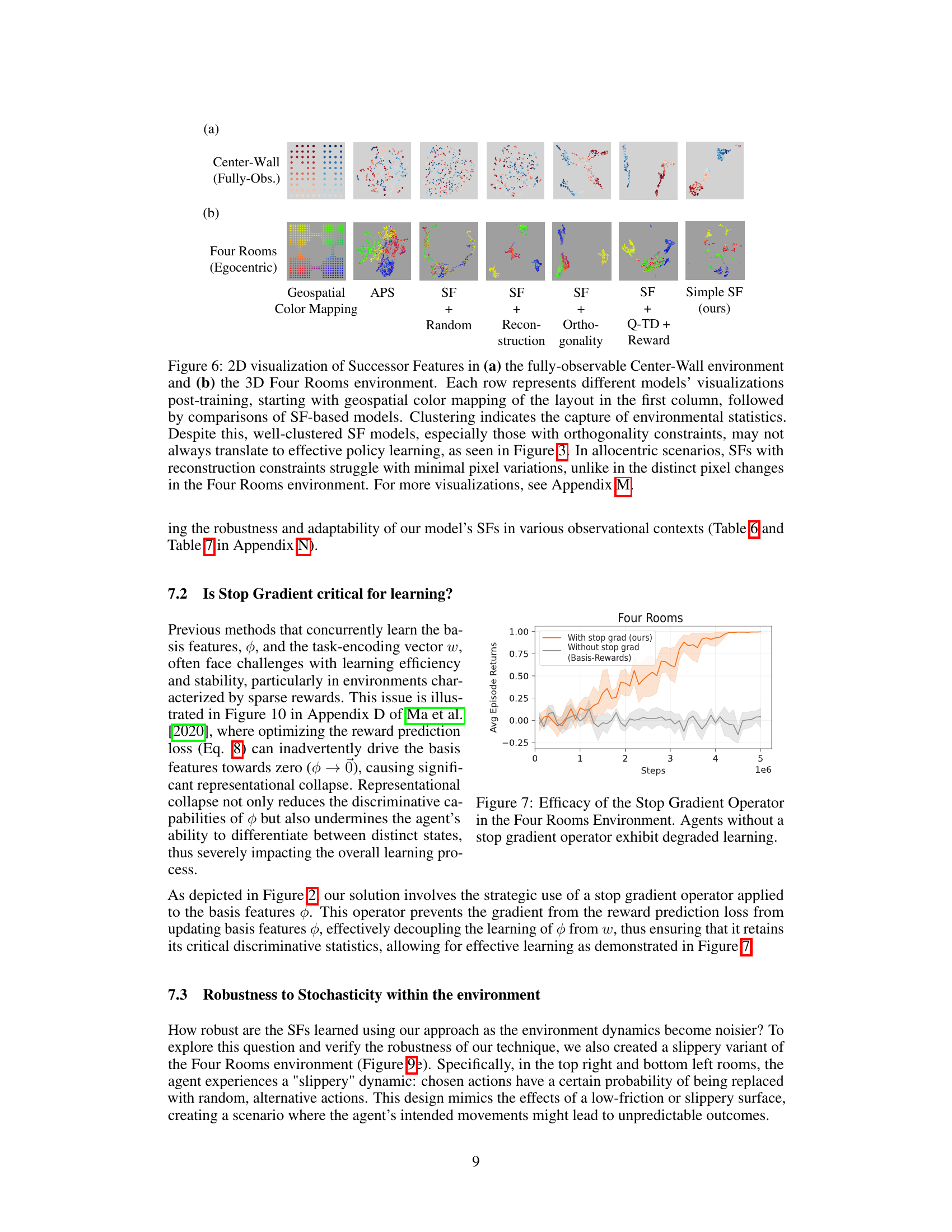

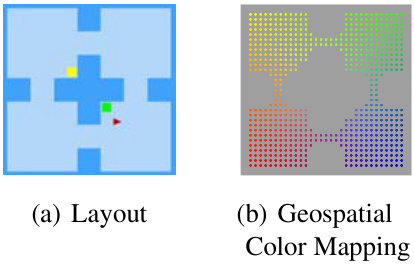

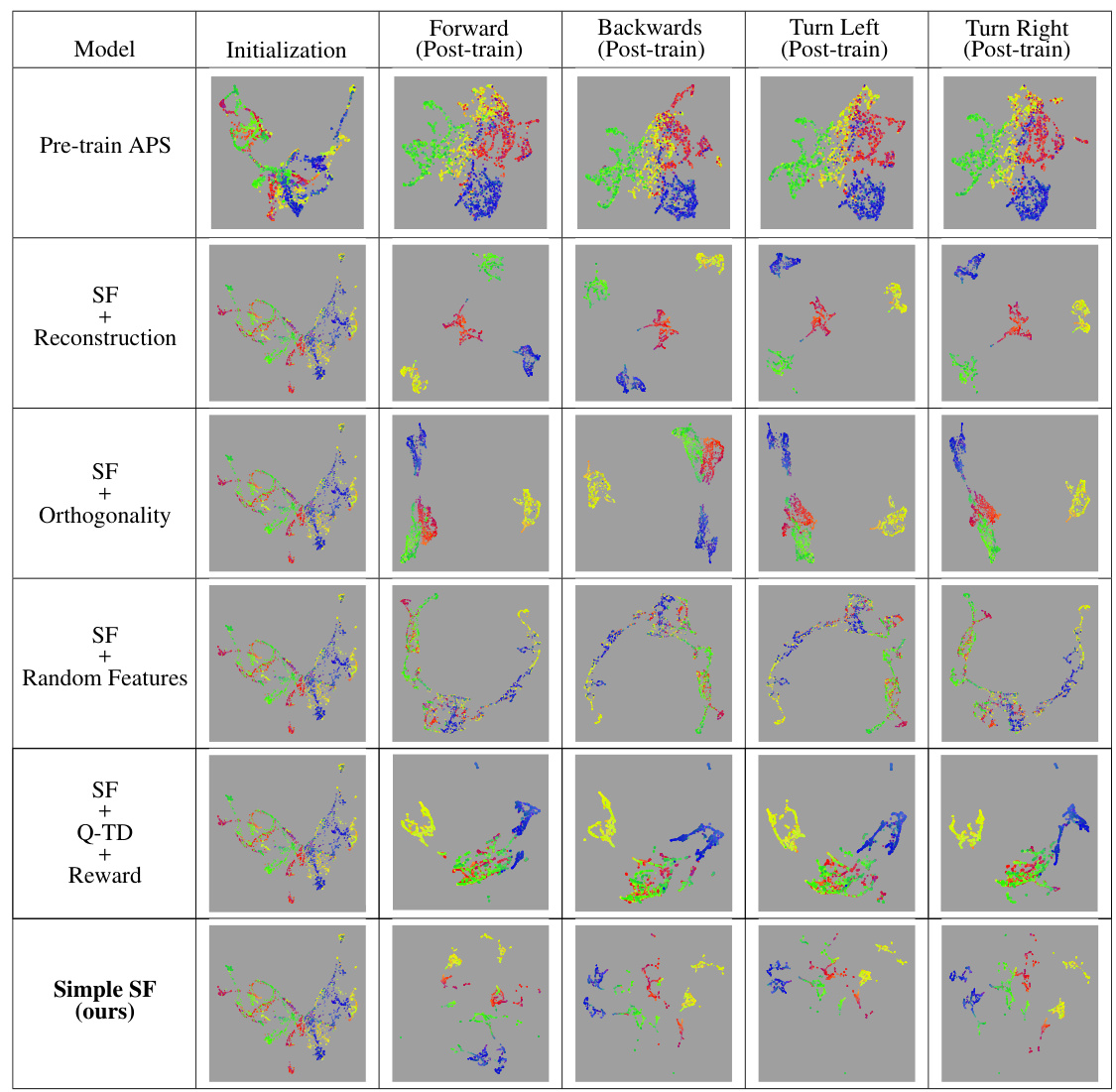

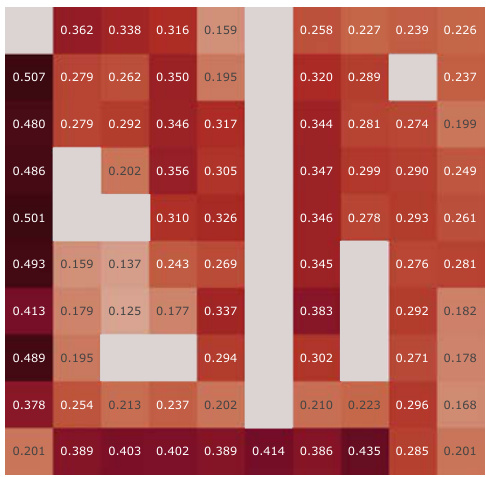

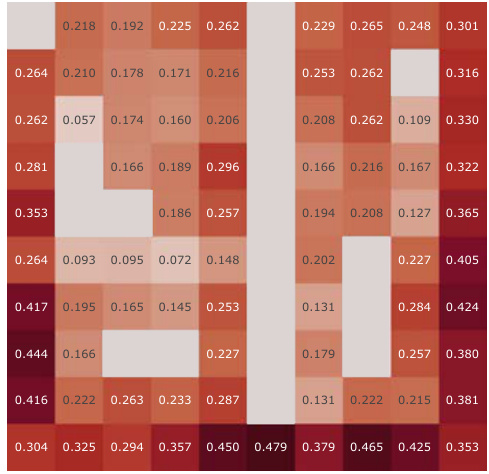

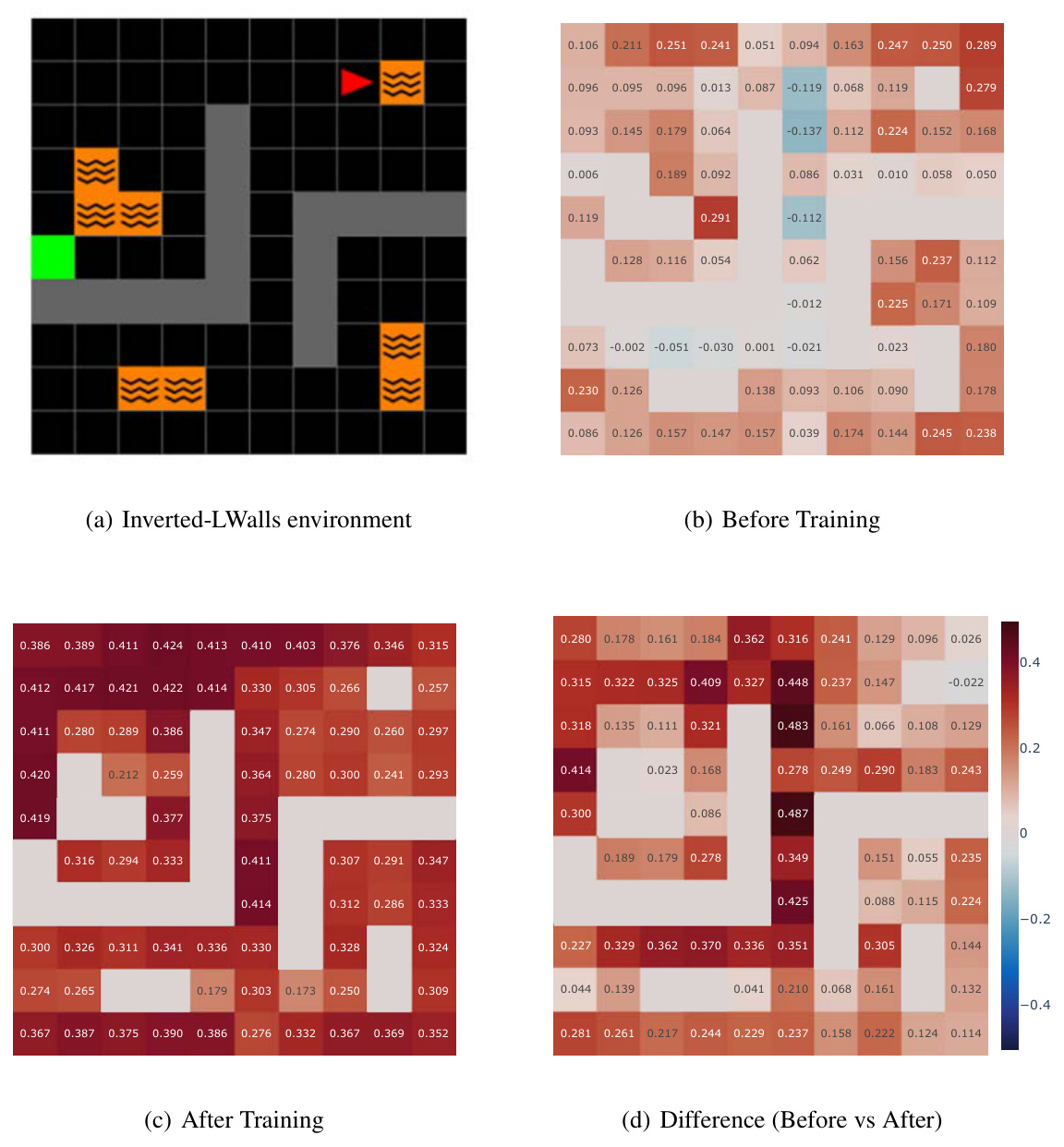

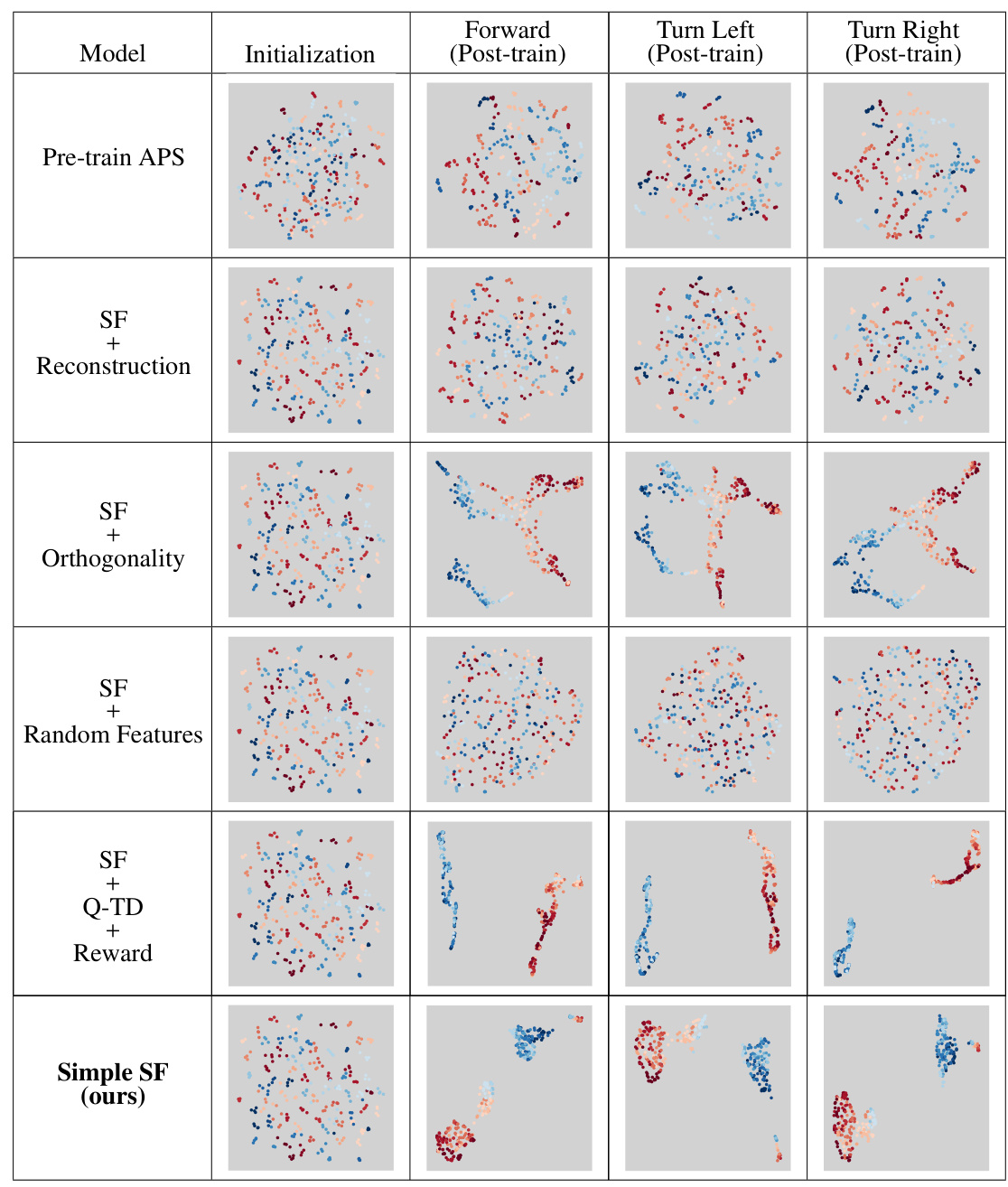

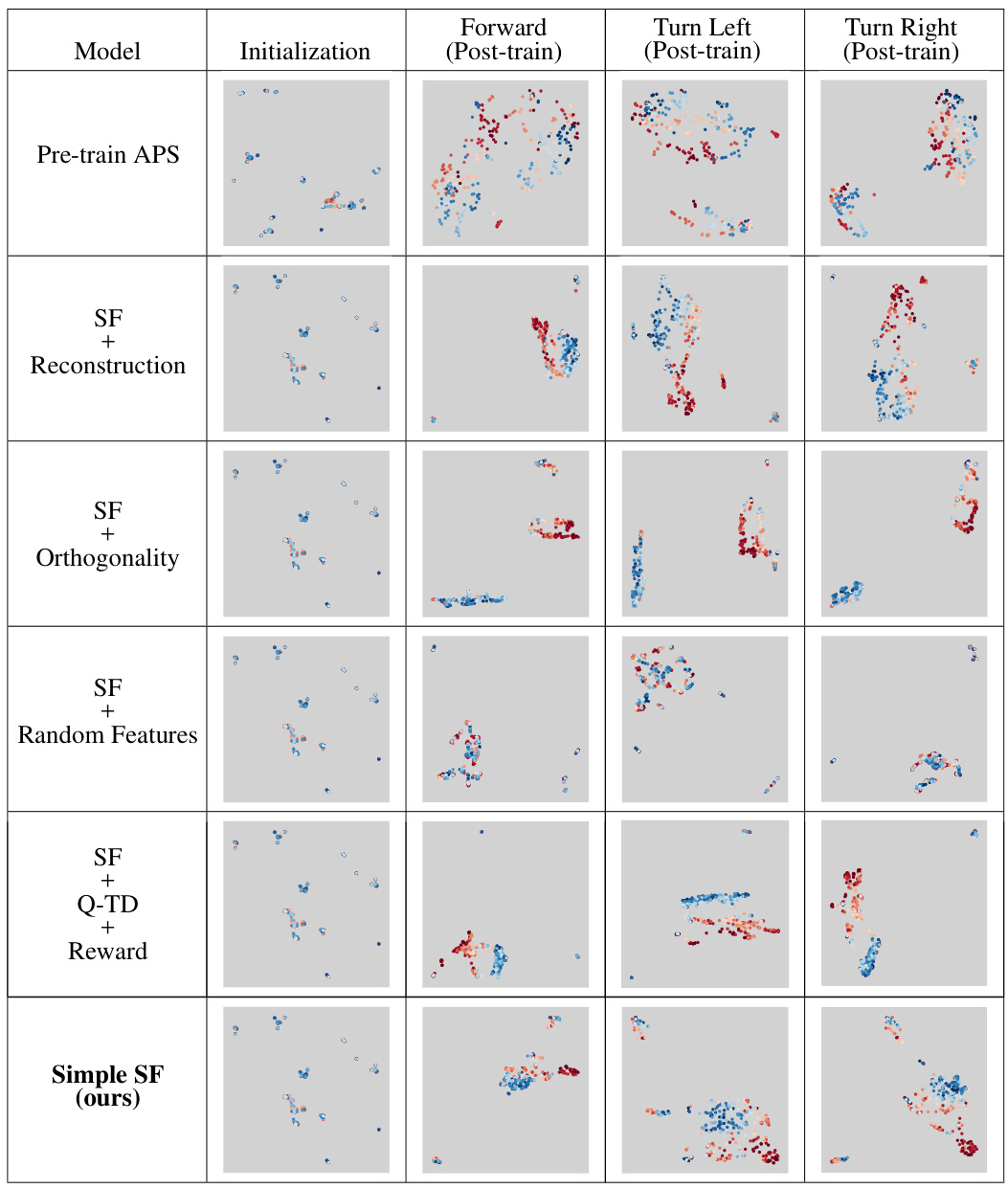

This figure visualizes successor features learned by different models in two environments: a fully-observable 2D environment and a partially-observable 3D environment. The visualizations use 2D plots with geospatial color mapping to show how well the learned features cluster in the space. The results show that while well-clustered representations may be correlated with good learning, they do not guarantee good policy learning. The analysis also shows that minimal changes in pixel values in a fully-observable environment can hurt the learning of models using reconstruction methods. Different performance is shown by the same model in the two environments.

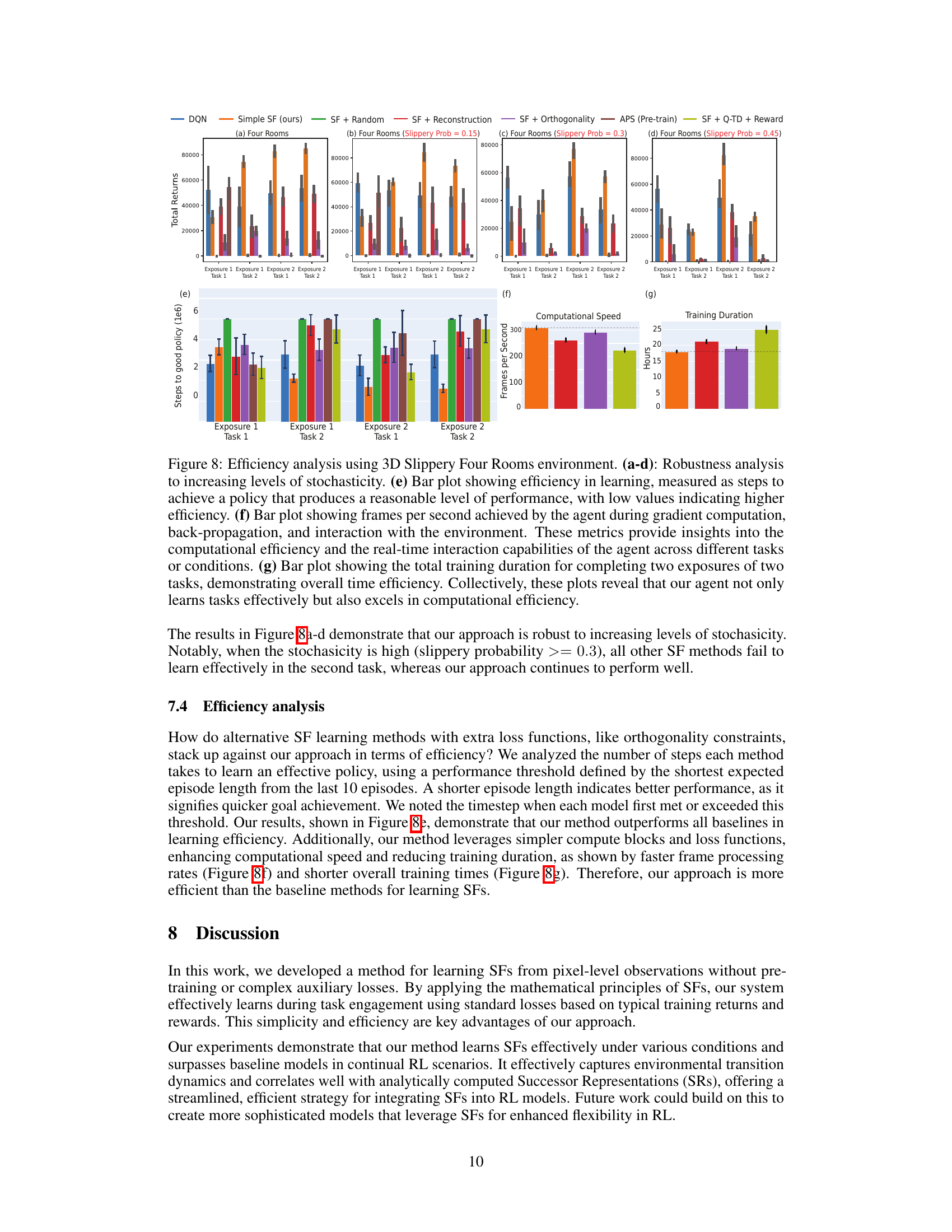

This figure shows the average episode returns of two agents learning in the Four Rooms environment over 5 million time steps. The orange line represents an agent using the proposed method with a stop gradient operator applied to the basis features. The gray line shows an agent learning without the stop gradient operator. The shaded areas represent the standard deviations across 5 random seeds. The results demonstrate that the stop gradient operator is crucial for effective learning, as the agent without it exhibits significantly degraded performance.

This figure presents the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments conducted in 2D and 3D environments using pixel observations. The experiments involved two tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset at each task transition to simulate drastic distribution shifts. The plots show the total cumulative returns achieved by different agents, including DQN and agents that incorporate additional constraints for learning Successor Features (SFs). The results demonstrate that the proposed Simple SF method outperforms other approaches in terms of both performance and transfer learning across multiple tasks and environments.

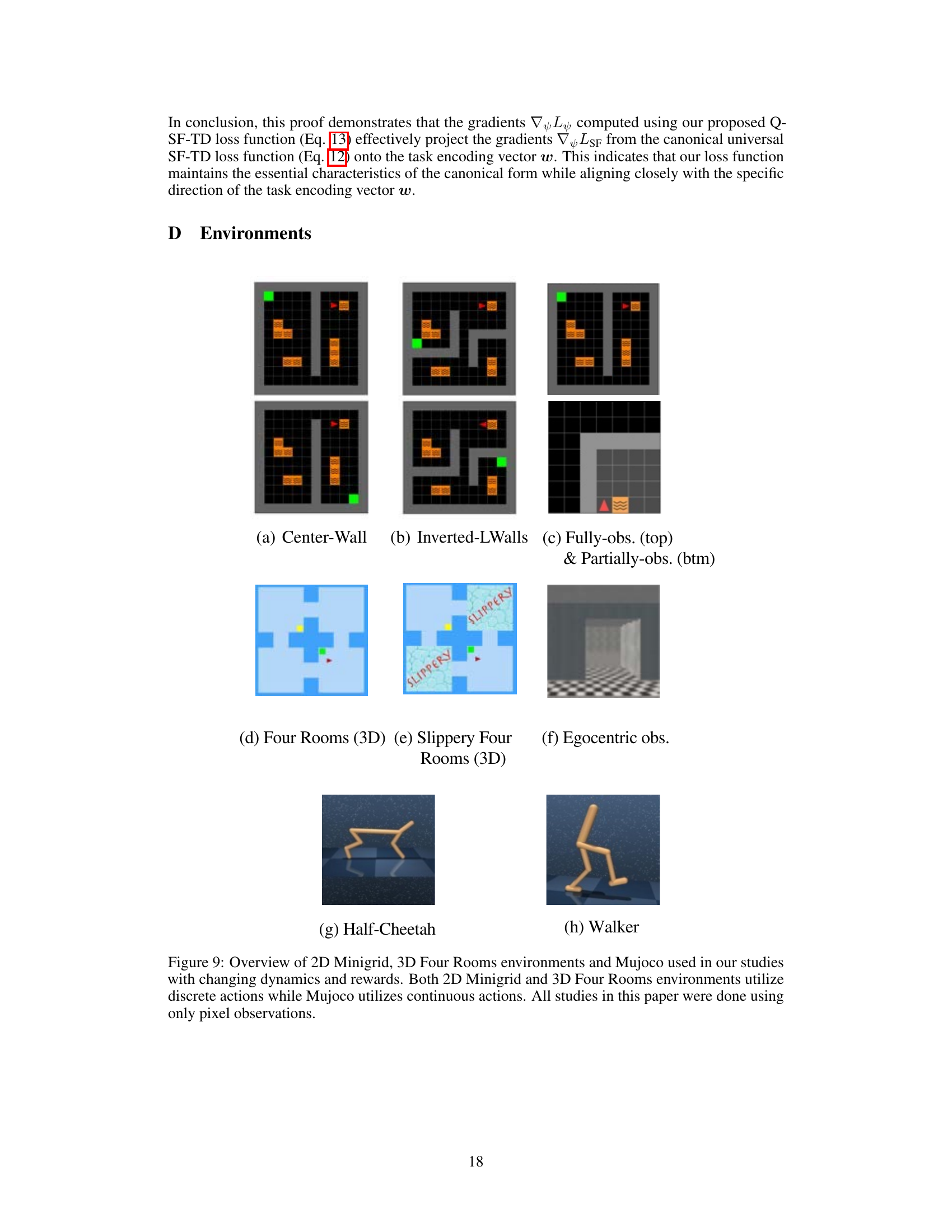

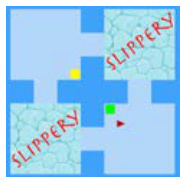

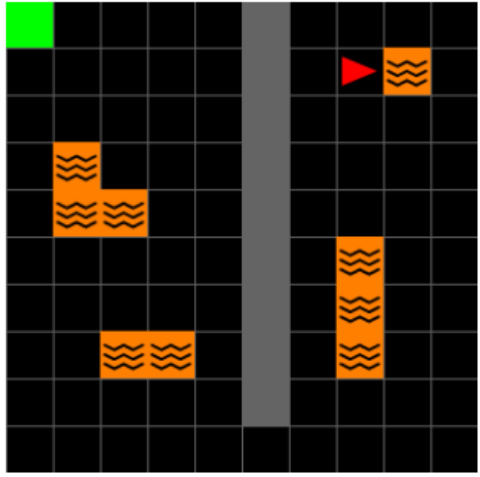

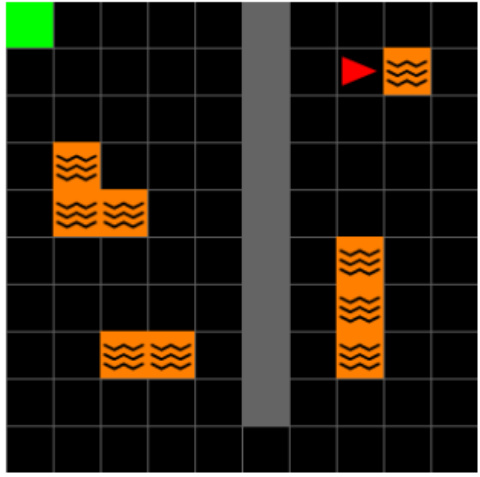

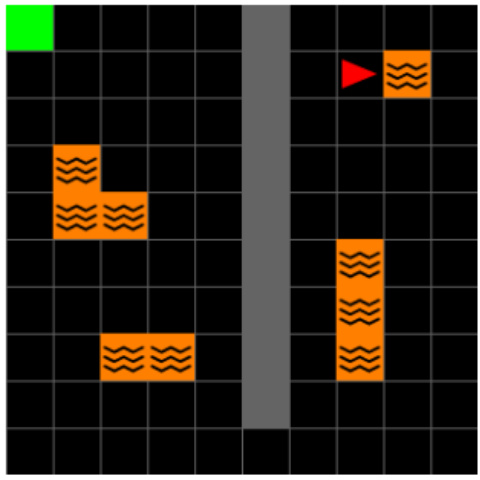

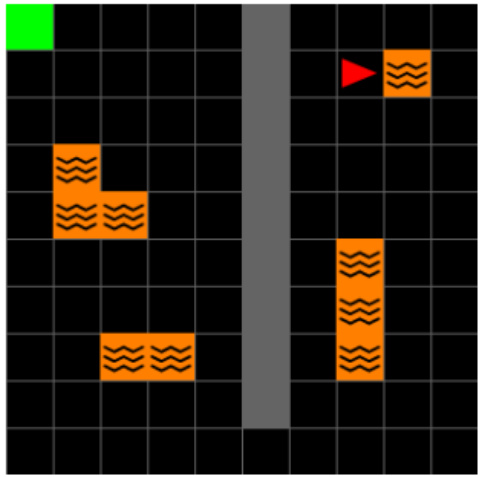

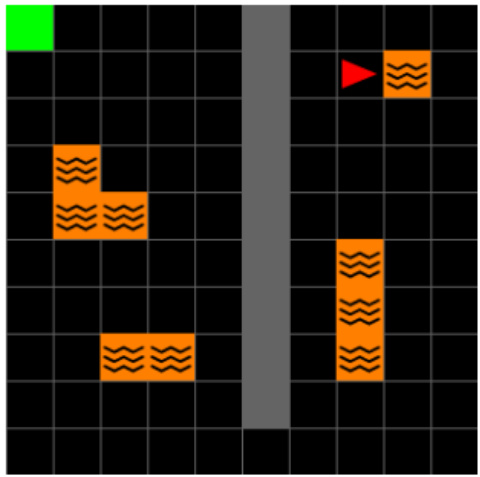

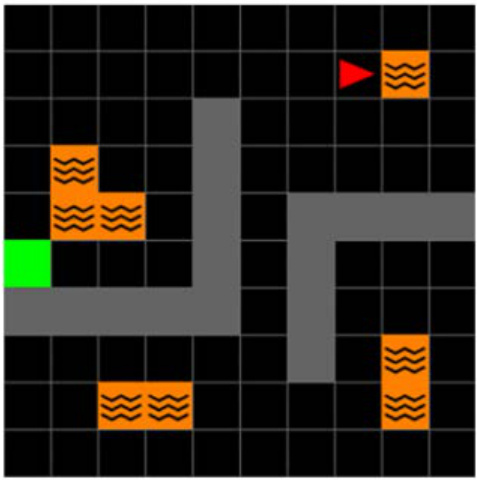

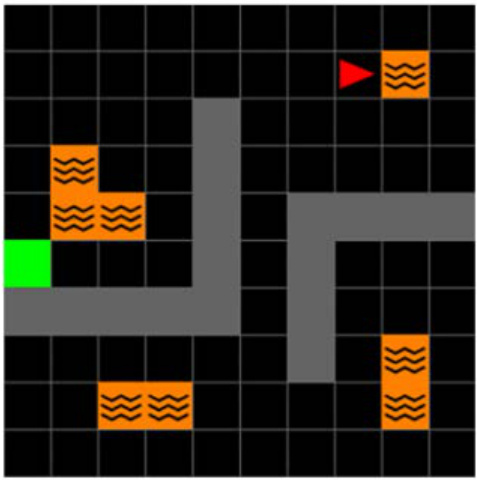

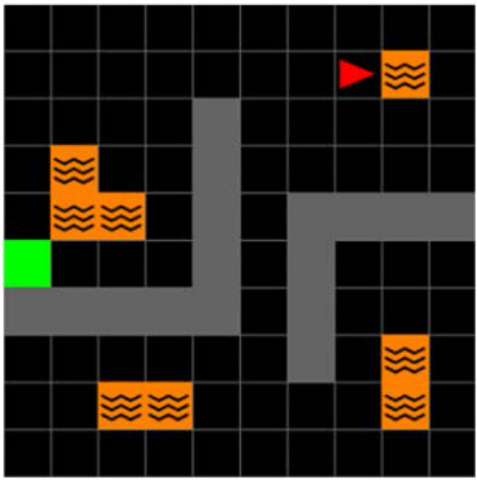

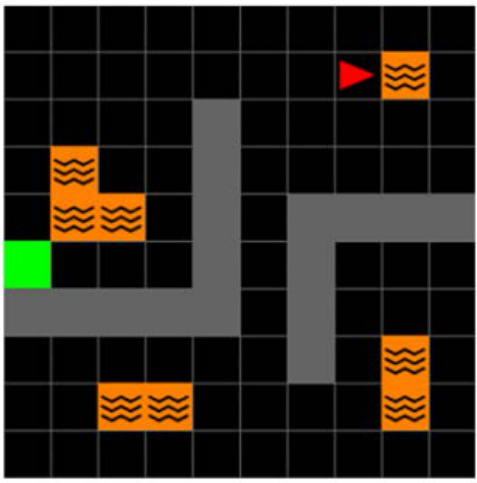

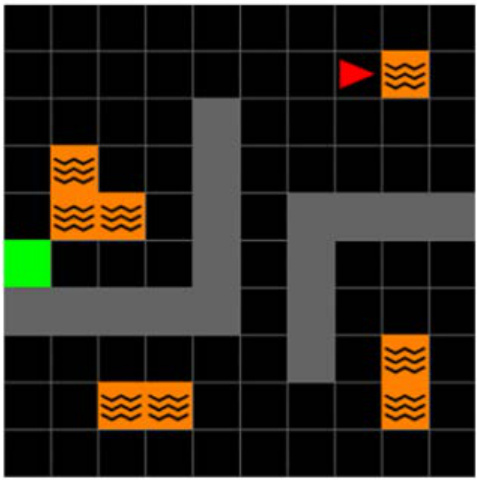

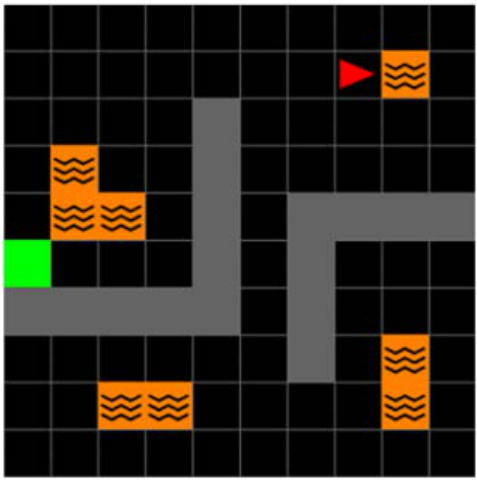

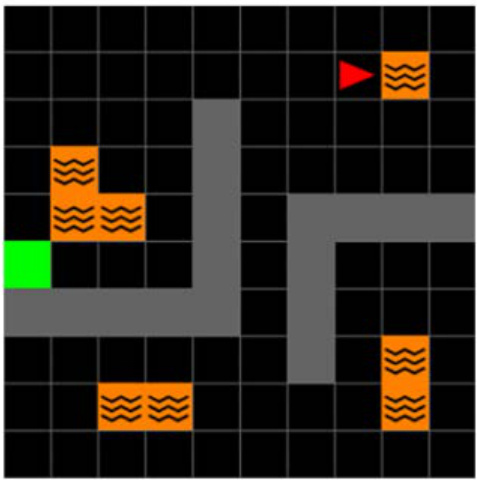

This figure shows the different environments used in the paper’s experiments. It includes several 2D grid worlds with variations in layout and observability, a 3D four-room environment (with and without slippery floors), and two continuous control tasks from MuJoCo (half-cheetah and walker). The key point is that all experiments used pixel observations, allowing the authors to test their algorithm’s ability to handle raw visual input.

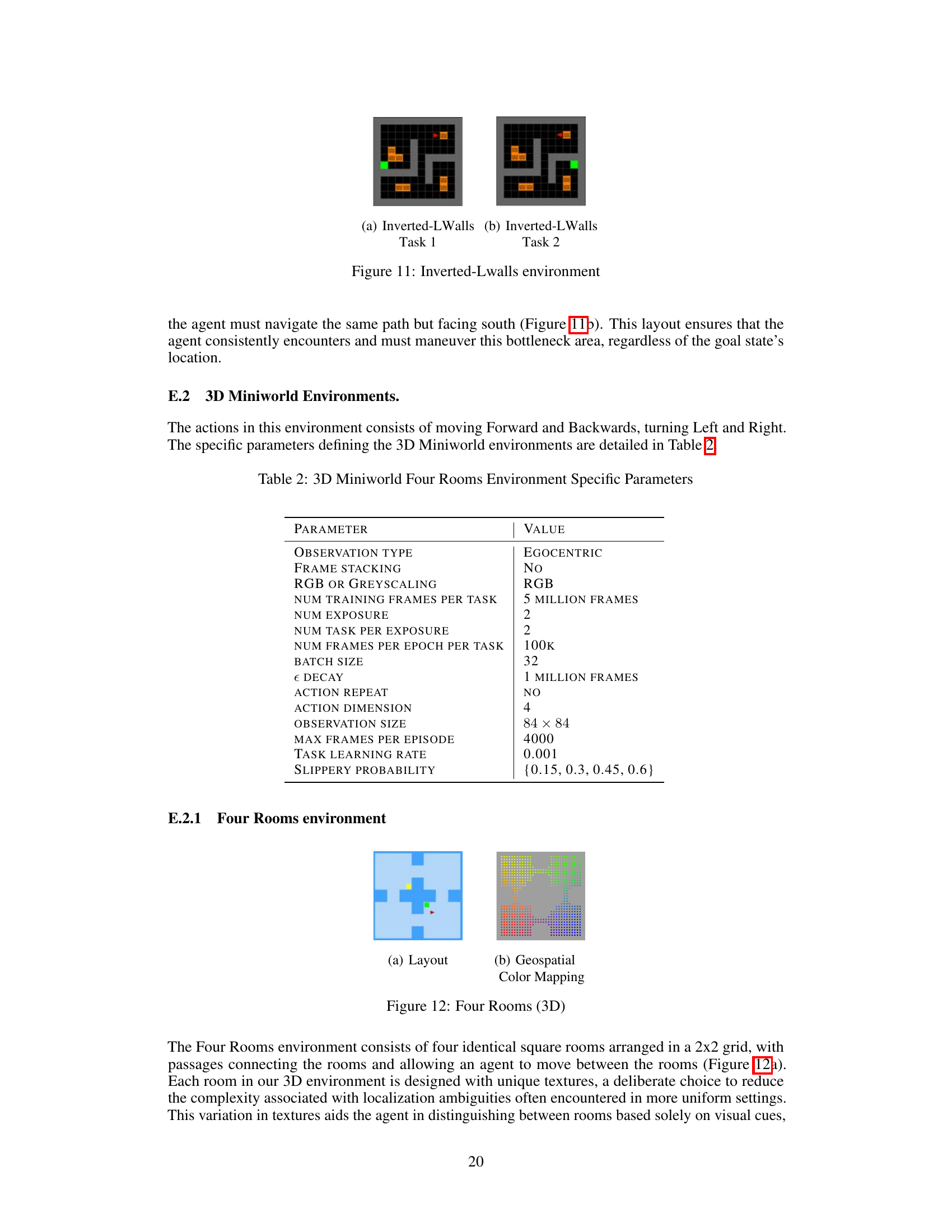

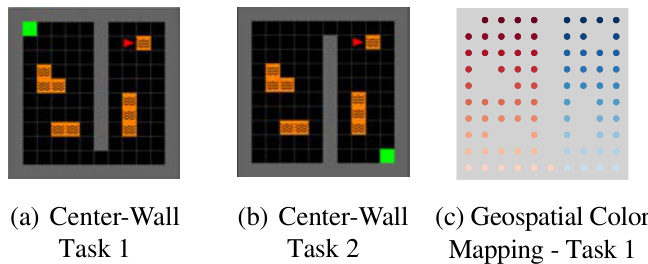

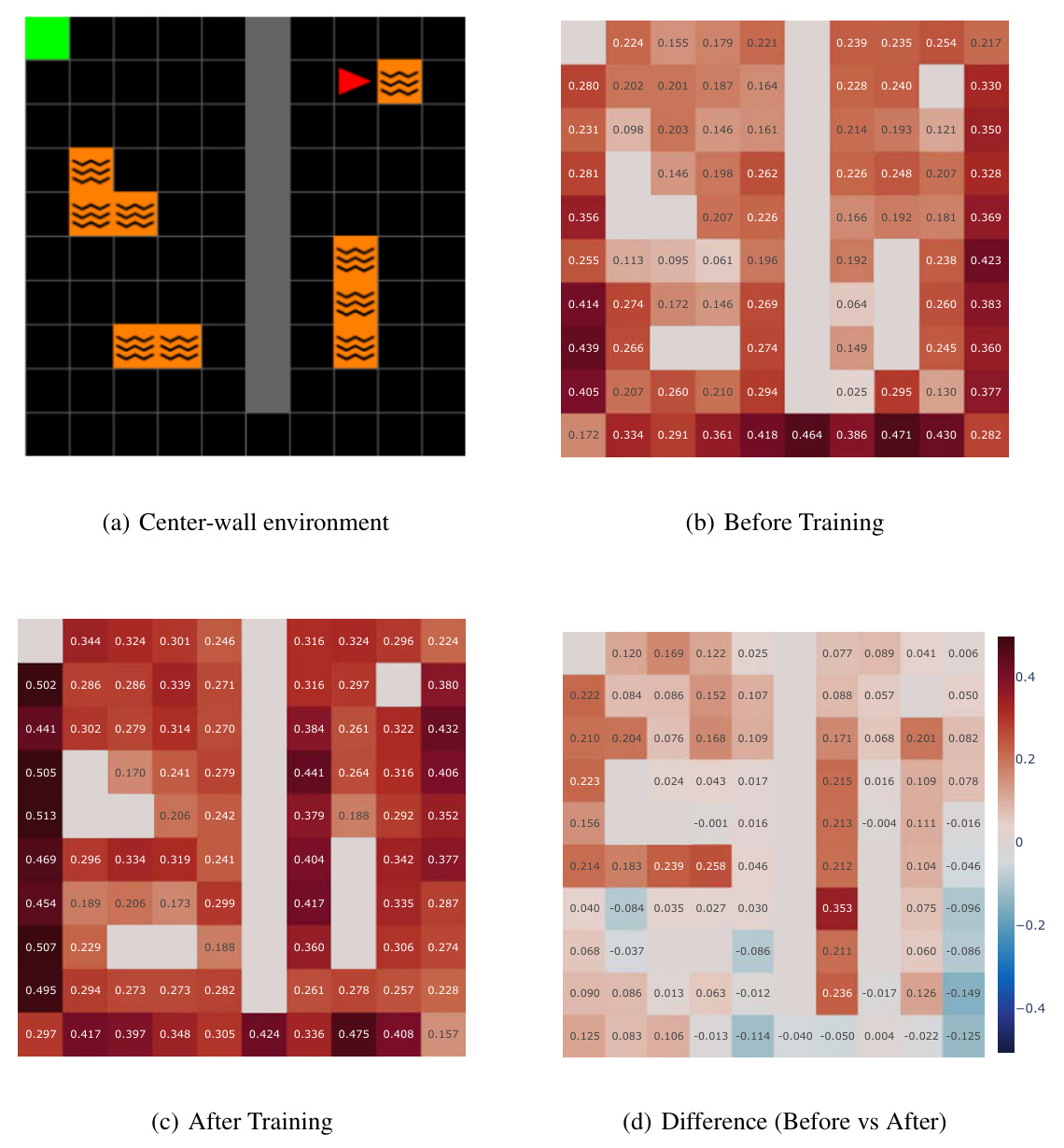

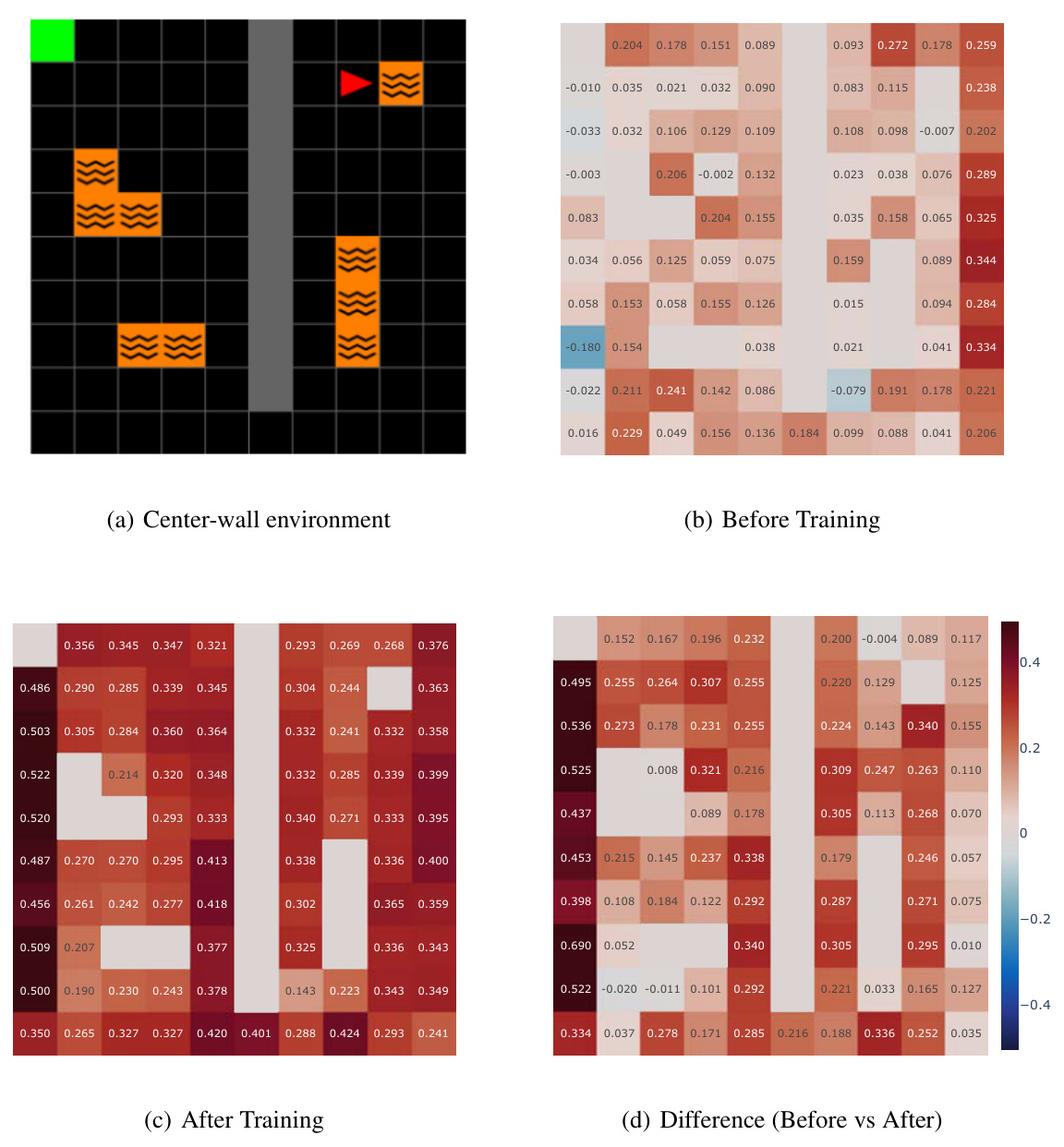

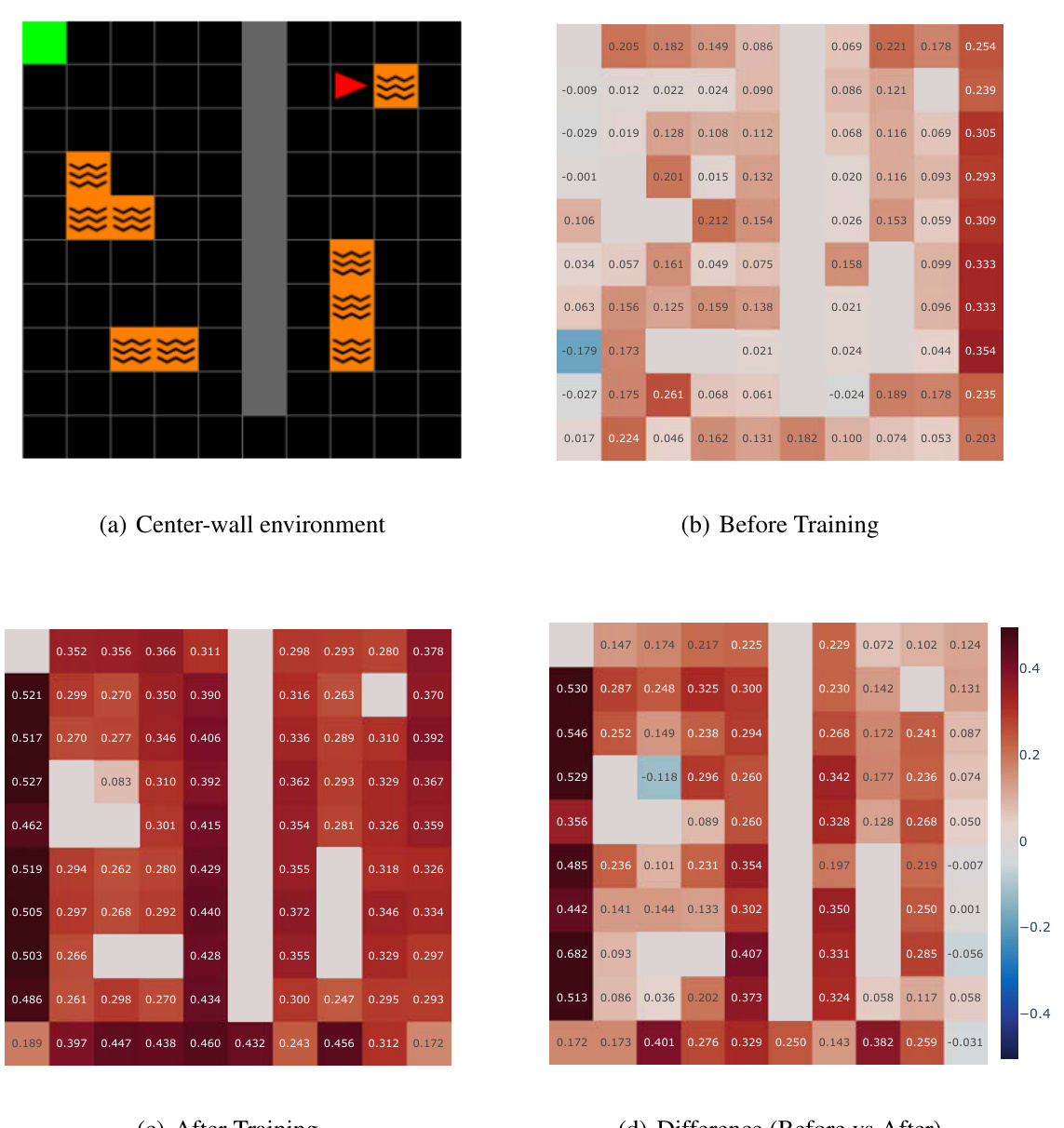

This figure shows the layout of the Center-Wall environment in two different tasks. Task 1 has a passage at the bottom, while task 2 has the passage at the top. The goal location also changes between the tasks. A geospatial color mapping is used to visualize the environment.

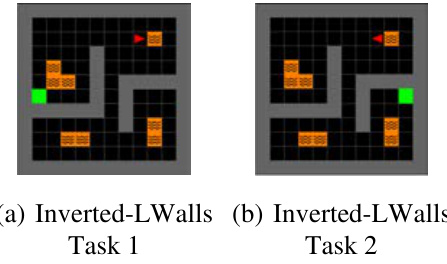

This figure shows two different layouts of the Inverted-Lwalls environment used in the paper’s experiments. In Task 1, the goal is on the left side of the environment and in Task 2, the goal is on the right side. The agent needs to navigate the same path but must face in opposite directions to reach the goal. The layouts ensure that the agent consistently encounters the bottleneck area, regardless of the goal’s location.

The figure shows the layout of the Center-Wall environment with two different tasks. In Task 1, the goal is located in the top-left corner, and in Task 2, the goal is moved to the bottom-right corner. To aid in visual analysis, a geospatial color mapping is included, which illustrates the spatial positioning within the environment and helps in understanding how agents interpret and navigate the modified environment. This is useful in visualizing the Successor Features and DQN Representations.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper. The top row shows the 2D grid world environments (Minigrid), the middle row shows the 3D grid world environments (Miniworld), and the bottom row shows the Mujoco environments. The figure highlights that all experiments are conducted using only pixel observations, despite the environments offering both discrete (Minigrid and Miniworld) and continuous (Mujoco) actions. The environments offer variation in the complexity of the tasks, such as partially and fully observable states, changes in reward locations, and alterations in the transition dynamics (such as the ‘slippery’ variant of the Four Rooms).

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed model for learning Successor Features (SFs). It uses a shared encoder to extract latent representations from pixel inputs, then uses these representations to learn the basis features, and finally, learns the SFs and task-encoding vector by minimizing the reward prediction loss and the Q-SF-TD loss. The use of a stop-gradient operator during the training process prevents instability, as described in the paper. The architecture is designed to directly learn from pixel observations without any pre-training.

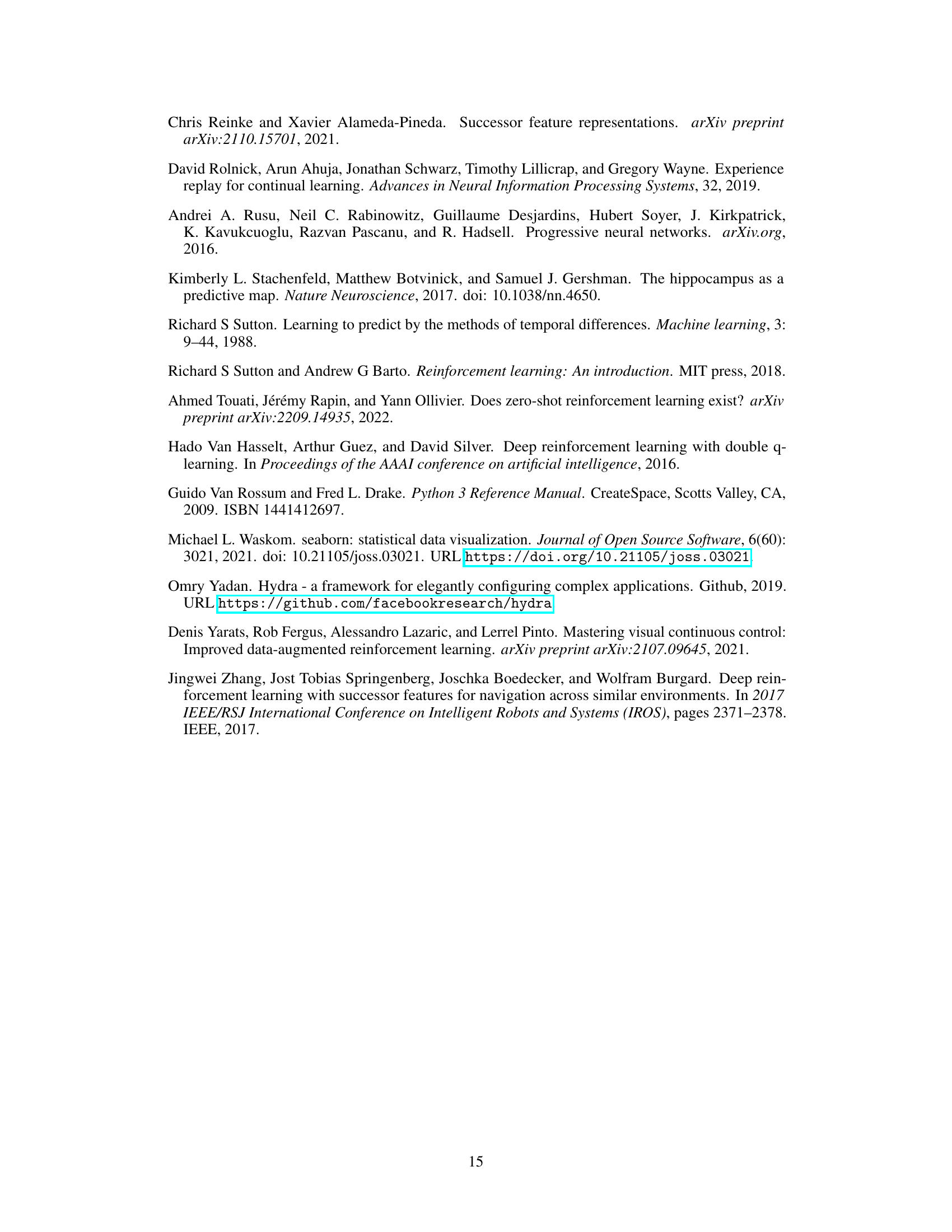

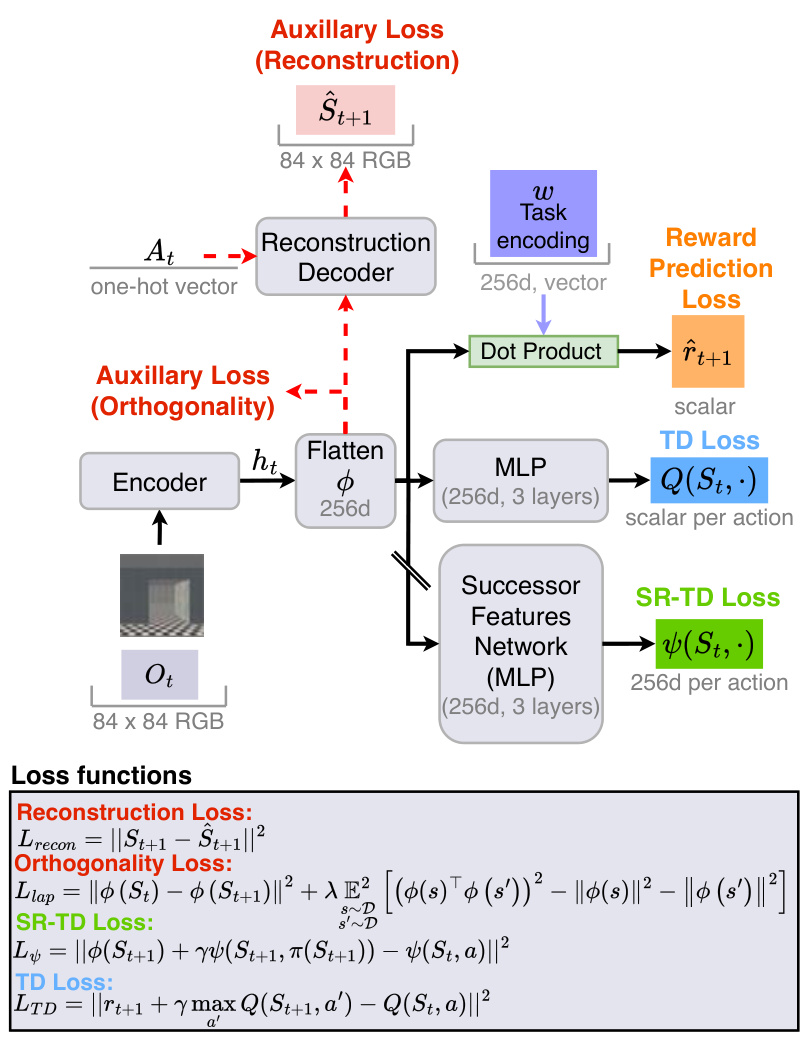

This figure illustrates the model architectures of previous approaches to prevent representation collapse in learning successor features from pixel observations. It shows the use of additional loss terms like reconstruction loss and orthogonality loss along with the standard SR-TD loss and TD loss, and the use of a stop gradient operator to avoid the basis features from being updated when optimizing the SF-TD loss.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments conducted in 2D and 3D environments. Three different tasks were performed sequentially, with each repeated twice. The graph compares the total cumulative rewards earned by different agents across the tasks, illustrating how the proposed ‘Simple SF’ approach outperforms other methods, especially those with additional constraints on the learning process. This highlights the advantage of the Simple SF method for continual learning in dynamic environments.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning method due to representation collapse. The first subplot shows that the method fails to learn effectively in a simple 2D environment. The second subplot shows that the learned representations converge to the same point, demonstrating representation collapse. The third subplot shows that the representations don’t form distinct clusters, which is further evidence of representation collapse. A mathematical proof is given in section 3.4.

This figure shows the failure of canonical Successor Feature (SF) learning methods due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance in a 2D environment. Panel (b) demonstrates that the learned representations collapse, as shown by the cosine similarity between them approaching 1. Panel (c) further demonstrates this collapse by using clustering metrics (silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores).

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments conducted in 2D and 3D environments using pixel observations. The agents were trained on two tasks, each repeated twice with the replay buffer reset between each task (to simulate drastic distribution shifts). The total cumulative rewards are plotted over training time for different algorithms, including DQN and several methods using Successor Features (SFs) with various constraints. The results demonstrate that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method outperforms baselines, especially those with constraints that can hinder learning.

This figure shows the results of a continual reinforcement learning experiment across three different environments (2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms, and Mujoco). The experiment evaluates the performance of several agents, including the proposed Simple SF agent, in adapting to changes in reward functions and transition dynamics across multiple sequential tasks. The results demonstrate the superiority of the Simple SF agent in achieving continual learning compared to other agents, particularly those with additional constraints on their learned representations.

This figure shows the results of a continual reinforcement learning experiment comparing different algorithms, including the proposed Simple SF method, in 2D and 3D environments. The experiment involved two tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset between tasks to simulate drastic environmental changes. The plots show the cumulative returns over time. The Simple SF method consistently outperforms other algorithms, particularly those with added constraints, demonstrating its superior adaptability and efficiency.

This figure presents the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D Minigrid and 3D Four Rooms environments. The experiments simulated drastic distribution shifts by resetting the replay buffer at each task transition. The agents were trained on two sequential tasks, each repeated twice. The figure shows the total cumulative returns accumulated during training, comparing the performance of the proposed Simple SF method to DQN and other SF methods with added constraints (reconstruction and orthogonality). The Simple SF method demonstrates superior performance and better transfer learning.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D and 3D environments. The performance of the proposed Simple SF method is compared to several baselines including DQN and other SF methods with additional constraints. The results demonstrate that Simple SF outperforms the other methods across different scenarios, showing better transfer learning and adaptation to new tasks. The cumulative returns over time are presented, highlighting Simple SF’s superior performance in continual learning tasks. The figure highlights the negative impact of constraints such as reconstruction and orthogonality on the performance of other SF methods.

This figure demonstrates the failure of canonical Successor Features learning methods due to representation collapse in a simple 2D environment. Panel (a) shows that the canonical method fails to achieve good performance. Panels (b) and (c) show that the learned representations degenerate into nearly identical vectors, a phenomenon called representational collapse, which is mathematically proven in section 3.4.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Features (SFs) learning method due to representation collapse. Subfigure (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a simple 2D environment. Subfigure (b) shows that the cosine similarity between pairs of SFs approaches 1, indicating that the representations are collapsing into a single point. Subfigure (c) shows that the learned representations fail to form distinct clusters, further supporting the representation collapse. The paper provides a mathematical proof of this phenomenon.

The figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D Minigrid and 3D Four Rooms environments. The experiments simulate drastic distribution shifts by resetting the replay buffer at each task transition. The agents performed two sequential tasks (Task 1 and Task 2), each repeated twice (Exposure 1 and Exposure 2). The plot displays the moving average of episode returns over time for various learning algorithms, including Simple SF (the authors’ method), and other baselines. The results are shown separately for different environment types (egocentric and allocentric 2D Minigrid, and egocentric 3D Four Rooms).

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D and 3D environments. Three different scenarios are presented, each with two sequential tasks repeated twice. The cumulative returns accumulated over training are plotted for the different environments. The authors’ method (Simple SF, orange) consistently outperforms other agents, particularly those with constraints on the basis features, suggesting that these constraints impede learning.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D Minigrid and 3D Four Rooms environments. The experiments involved two tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset at each task transition to simulate drastic changes in the environment’s distribution. The plots display the total cumulative returns accumulated during training. The results demonstrate that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method significantly outperforms both a Deep Q-Network (DQN) baseline and other Successor Feature (SF) learning methods that incorporate additional constraints (reconstruction, orthogonality). These constraints, while aiming to address representation collapse, appear to hinder the learning process.

This figure visualizes the successor features learned by different RL agents in a fully observable environment. Each agent and action has a panel showing the initial (pre-training) and learned (post-training) successor features. The visualization uses a geospatial color mapping technique for better understanding. The results highlight the various encoding strategies used by different agents and how full observability impacts learning.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Features learning method due to representation collapse. Subfigure (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a 2D environment. Subfigure (b) shows that the cosine similarity between pairs of successor features approaches 1, indicating that the learned representations collapse to a single point. Subfigure (c) visually confirms this collapse using silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores, which indicate that the representations do not form distinct clusters. This demonstrates that the straightforward approach of using a temporal difference (TD) error on subsequent observations can lead to this problem.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning approach due to representation collapse. The first subplot shows the learning curve of a canonical SF agent in a 2D environment, which performs poorly compared to the proposed method. The second subplot shows that the learned representations in the canonical approach become highly similar, indicating a collapse in the representation space. The third subplot further supports this, showing that the representations do not form distinct clusters, as measured by silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores. A mathematical proof of representation collapse in the canonical approach is given in section 3.4.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Features learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the poor performance of the canonical method on a simple navigation task. Panels (b) and (c) provide further evidence of this collapse by showing that the learned representations become highly similar (cosine similarity close to 1) and fail to form distinct clusters (low silhouette, high Davies-Bouldin scores).

This figure presents the results of a continual reinforcement learning experiment using pixel observations. Three different environments are shown: a 2D Minigrid environment, a 3D Four Rooms environment, and a Mujoco environment. Each environment consists of two sequential tasks, each repeated twice. The figure shows that the proposed method (Simple SF, orange) outperforms other methods, including Deep Q-Network (DQN, blue) and methods with additional constraints (such as reconstruction and orthogonality), in terms of total cumulative returns accumulated during training. In all cases, the Simple SF method shows better transfer learning to later tasks and faster learning.

This figure presents the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D Minigrid and 3D Four Rooms environments. The experiments involved two tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset between tasks to simulate significant environmental shifts. The figure shows that the proposed method (‘Simple SF’, in orange) outperforms Deep Q-Network (DQN, in blue) and other successor feature methods with added constraints in terms of cumulative returns accumulated over the training process. This improvement is particularly evident in later tasks, indicating better transfer learning. Importantly, the results also show that adding constraints like reconstruction or orthogonality can negatively impact learning performance.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper’s experiments: 2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms, and Mujoco. The 2D and 3D environments have discrete action spaces, while Mujoco has a continuous action space. Importantly, all experiments in the paper used only pixel-level observations as input to the agents.

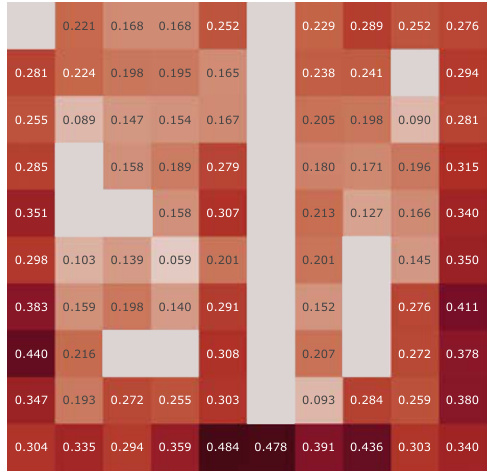

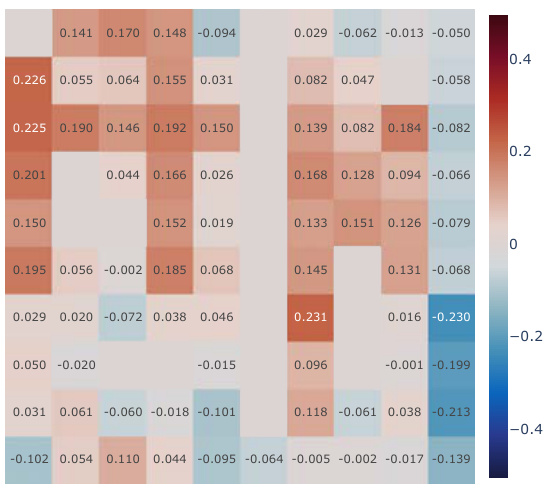

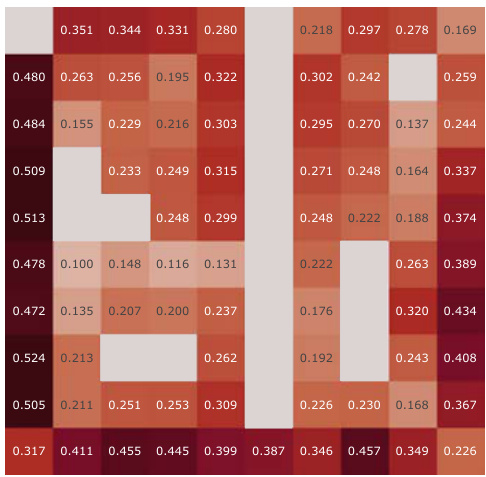

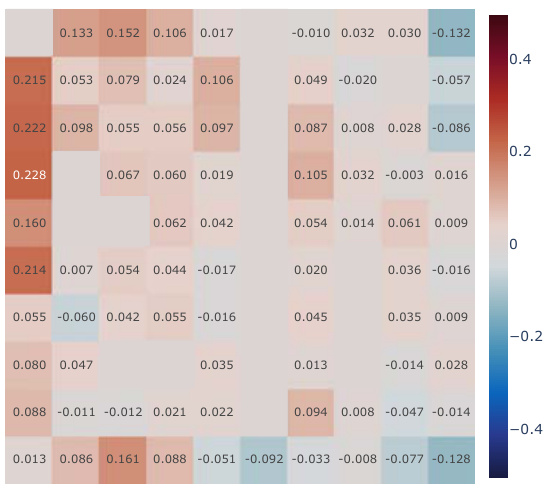

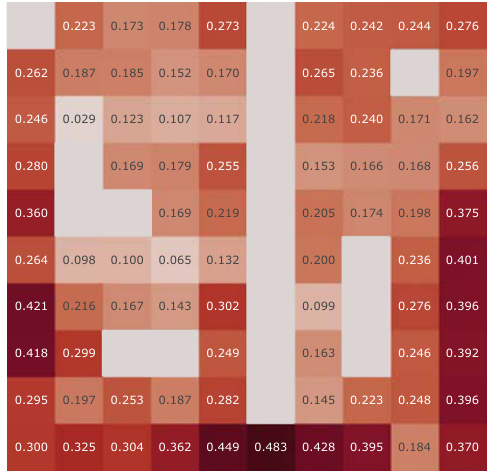

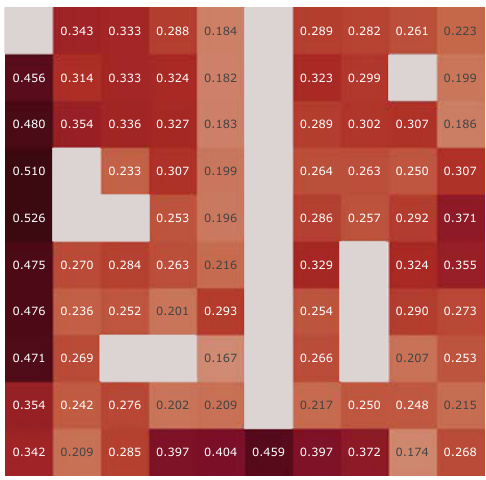

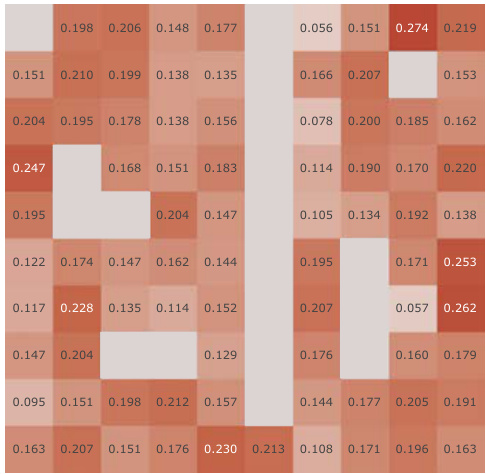

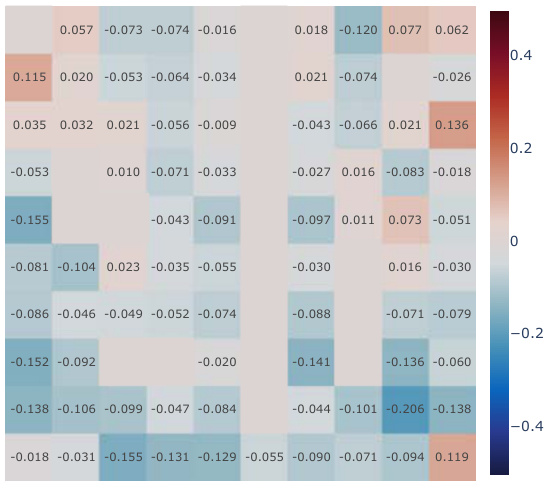

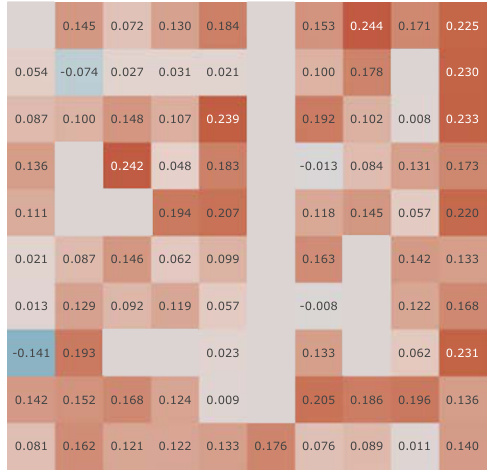

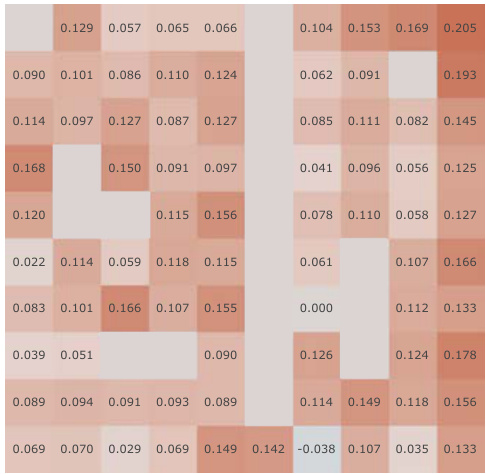

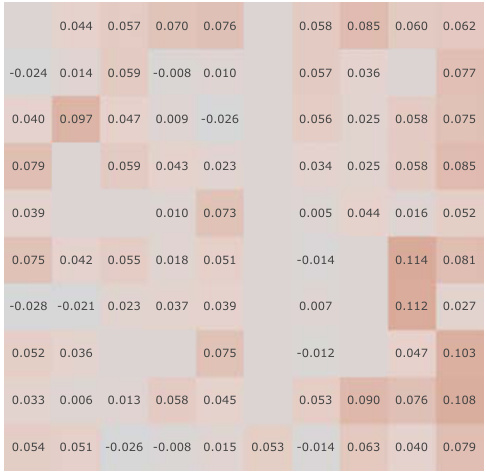

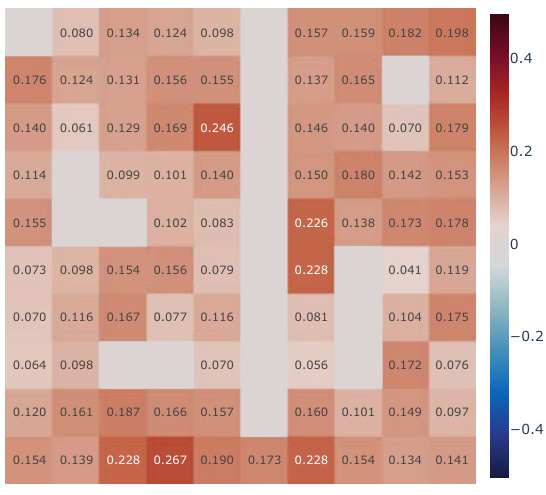

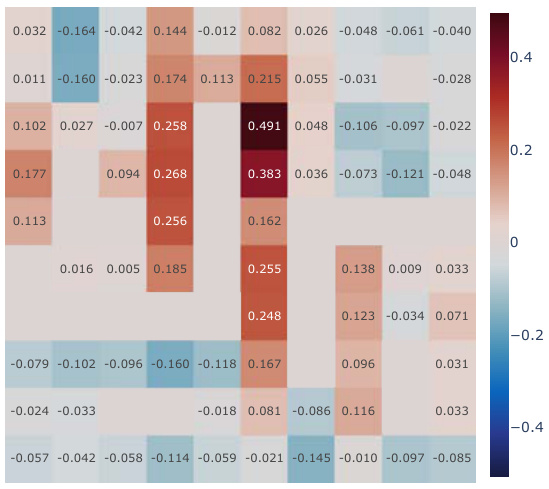

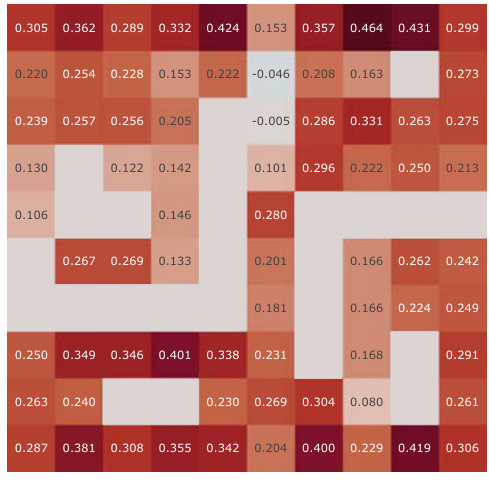

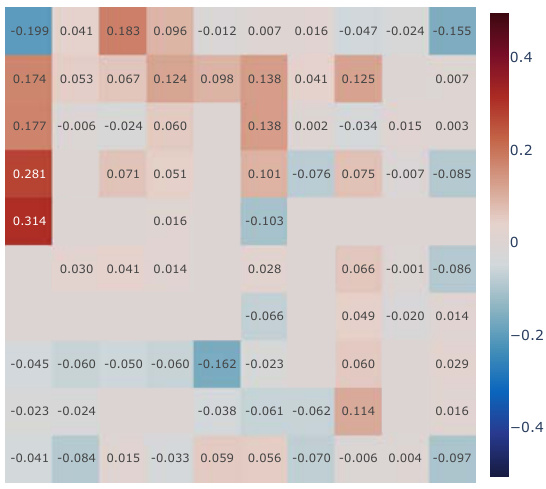

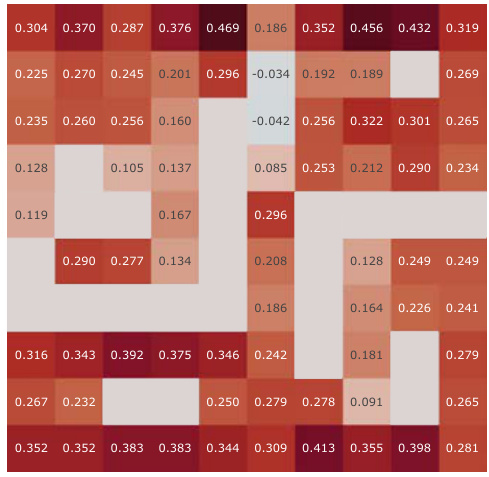

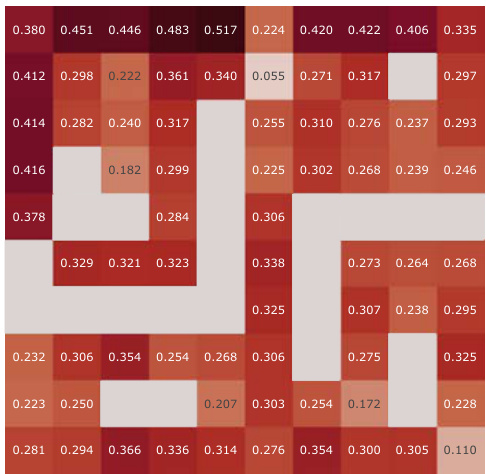

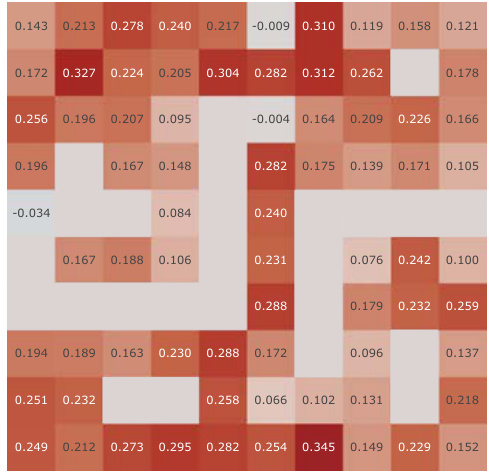

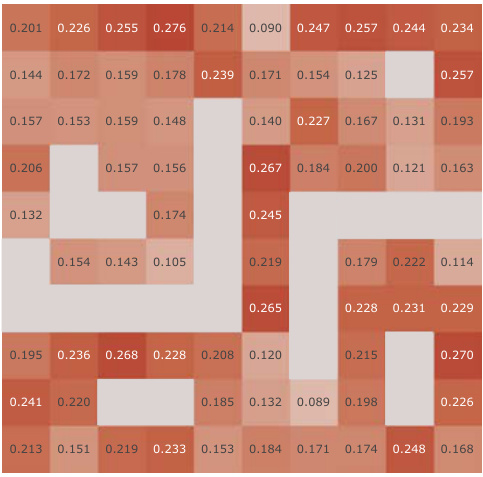

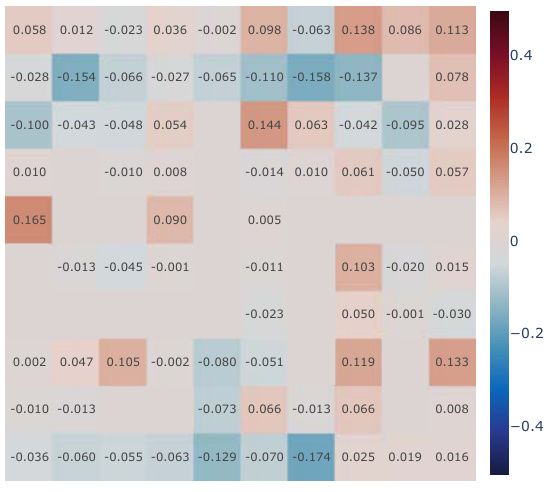

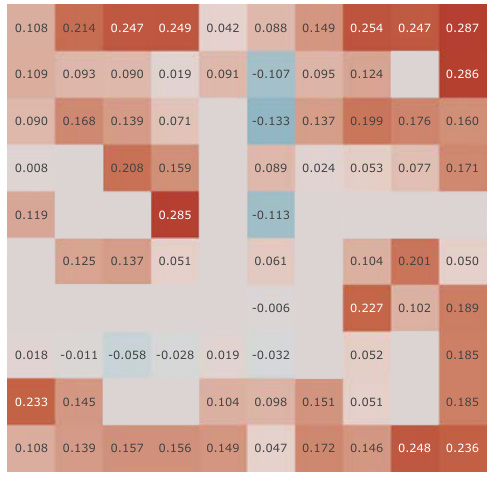

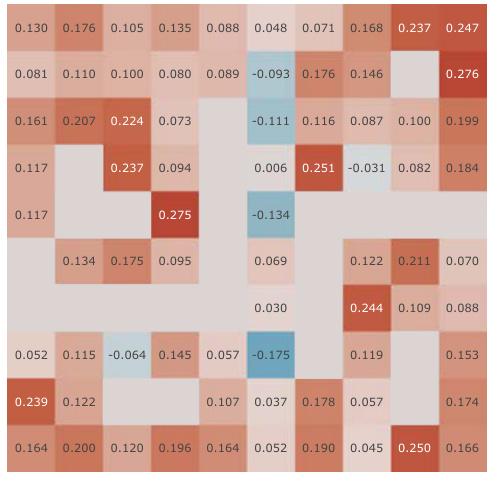

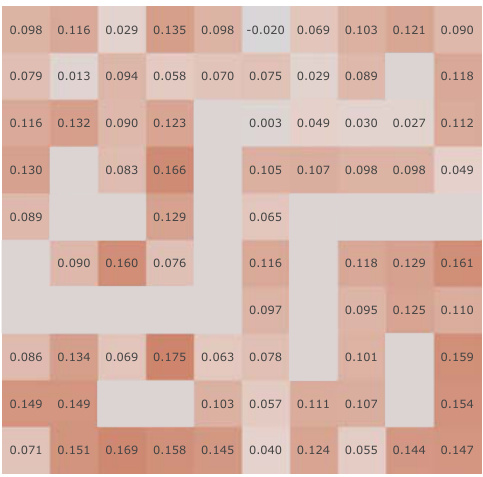

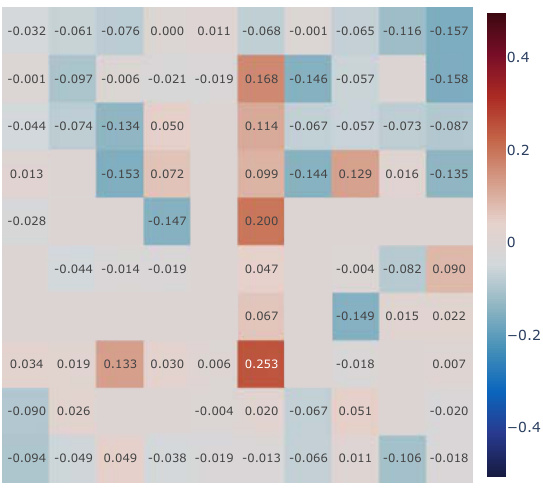

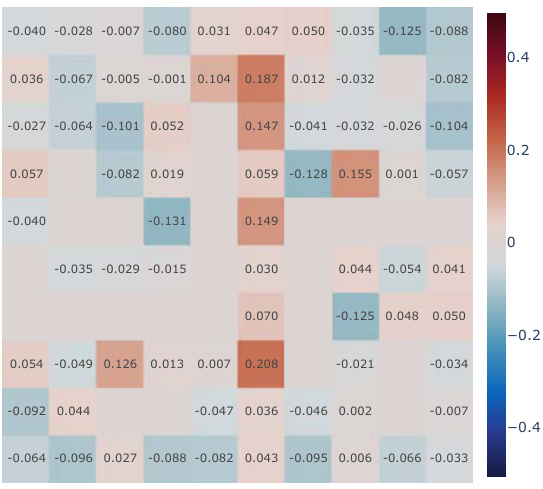

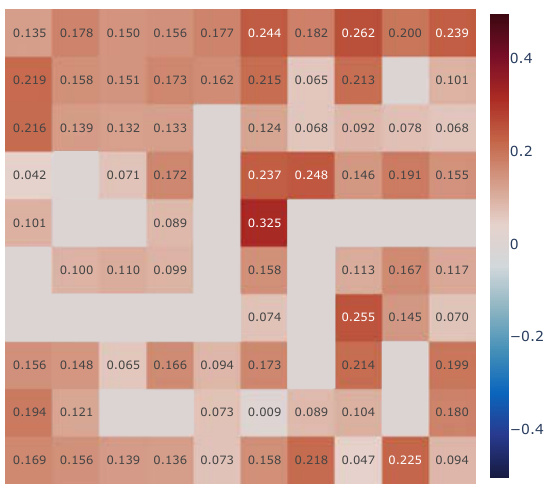

This figure presents a correlation analysis between the learned Simple Successor Features and the analytically computed Successor Representation. The analysis is performed for all positions in the Center-Wall environment under a partially-observable scenario. The heatmaps visualize the correlation values before and after training, along with the differences. It demonstrates how the correlation changes as the agent learns, highlighting the agent’s adaptation to the environment.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments conducted in 2D and 3D environments using pixel observations. Three scenarios are presented: a 2D two-room environment (with egocentric and allocentric views), and a 3D four-room environment. In each, agents learned using several different methods, including a standard DQN and several variations of Successor Feature learning. The plots show the total cumulative returns over training. The key takeaway is that the proposed Simple SF method (orange) consistently outperforms other methods, particularly those that incorporate additional constraints (reconstruction, orthogonality) that often hinder learning performance.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D Minigrid and 3D Four Rooms environments. The experiments evaluate the performance of the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method against several baselines, including DQN and other SF learning methods with additional constraints (reconstruction and orthogonality). The results demonstrate that the Simple SF method outperforms the baselines in terms of cumulative returns and transfer learning across multiple tasks, highlighting the impact of representation collapse in other methods.

This figure shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical Successor Features (SF) learning rule due to representation collapse. Panel (a) displays the average episode returns over training steps in a 2D environment. Panel (b) shows that the average cosine similarity between pairs of learned SFs converges to 1, indicating representation collapse. Panel (c) uses silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores to demonstrate that the canonical SFs do not form distinct clusters, further supporting the presence of representation collapse. A mathematical proof of this collapse is provided in section 3.4 of the paper.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D and 3D environments. The experiment involves two tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset between each task to simulate a drastic shift in the data distribution. The plots (a-c) present the total cumulative returns achieved during training, demonstrating that the proposed Simple SF (orange) method significantly outperforms a Deep Q-Network (DQN, blue) baseline and other methods incorporating additional constraints on the basis features (like reconstruction or orthogonality). These constraints appear to hinder learning performance.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments in 2D and 3D environments. Three different scenarios are shown, each with two tasks performed twice. The results show that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method significantly outperforms other methods, particularly those that use additional constraints, indicating that simpler methods are more effective in this scenario.

This figure shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical Successor Features learning rule due to representation collapse. The average cosine similarity between pairs of SFs approaches 1, indicating collapse. Representation clusters are not well-formed, with low silhouette scores and high Davies-Bouldin scores confirming the representation collapse. A mathematical proof is included in the paper.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) displays the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a simple 2D environment. Panel (b) demonstrates that the cosine similarity between learned representations approaches 1, indicating collapse. Panel (c) shows that the resulting representations fail to form distinct clusters, providing further evidence of collapse. The mathematical proof for this collapse is detailed in section 3.4 of the paper.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Features learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of this method in a simple 2D environment. Panel (b) illustrates that representation collapse occurs because the cosine similarity between pairs of SFs converges to 1. Panel (c) demonstrates that the learned representations do not form distinct clusters.

This figure presents a correlation analysis between the learned successor features from our proposed model and the analytically computed successor representation in a partially-observable Center-Wall environment. The analysis is performed before and after training, highlighting the difference in correlation. Heatmaps visualize the spatial distribution of correlations, showing how well the learned successor features capture the spatial relationships in the environment. This analysis is crucial to understand how effectively our model learns the successor representation and whether the learned representation corresponds well to the true spatial structure.

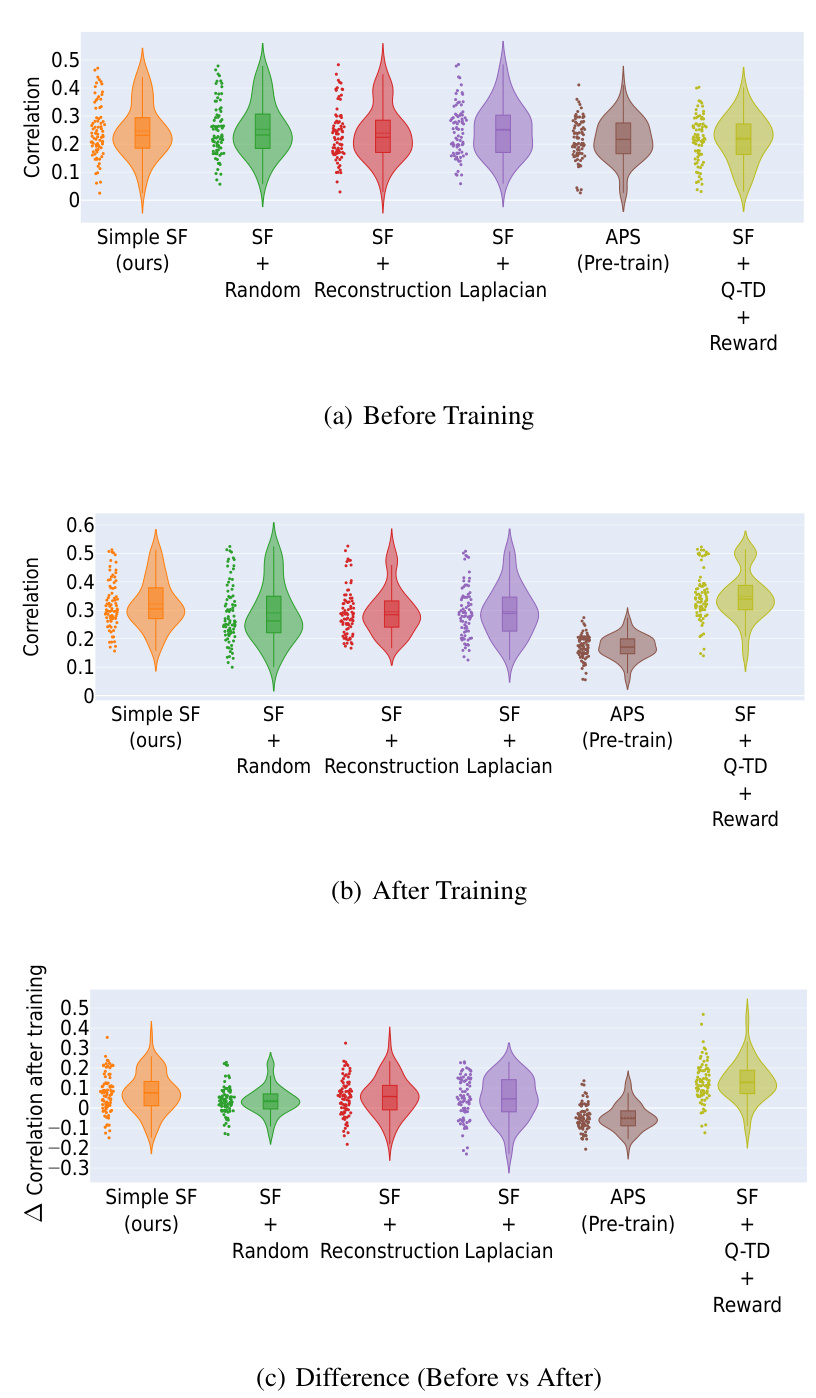

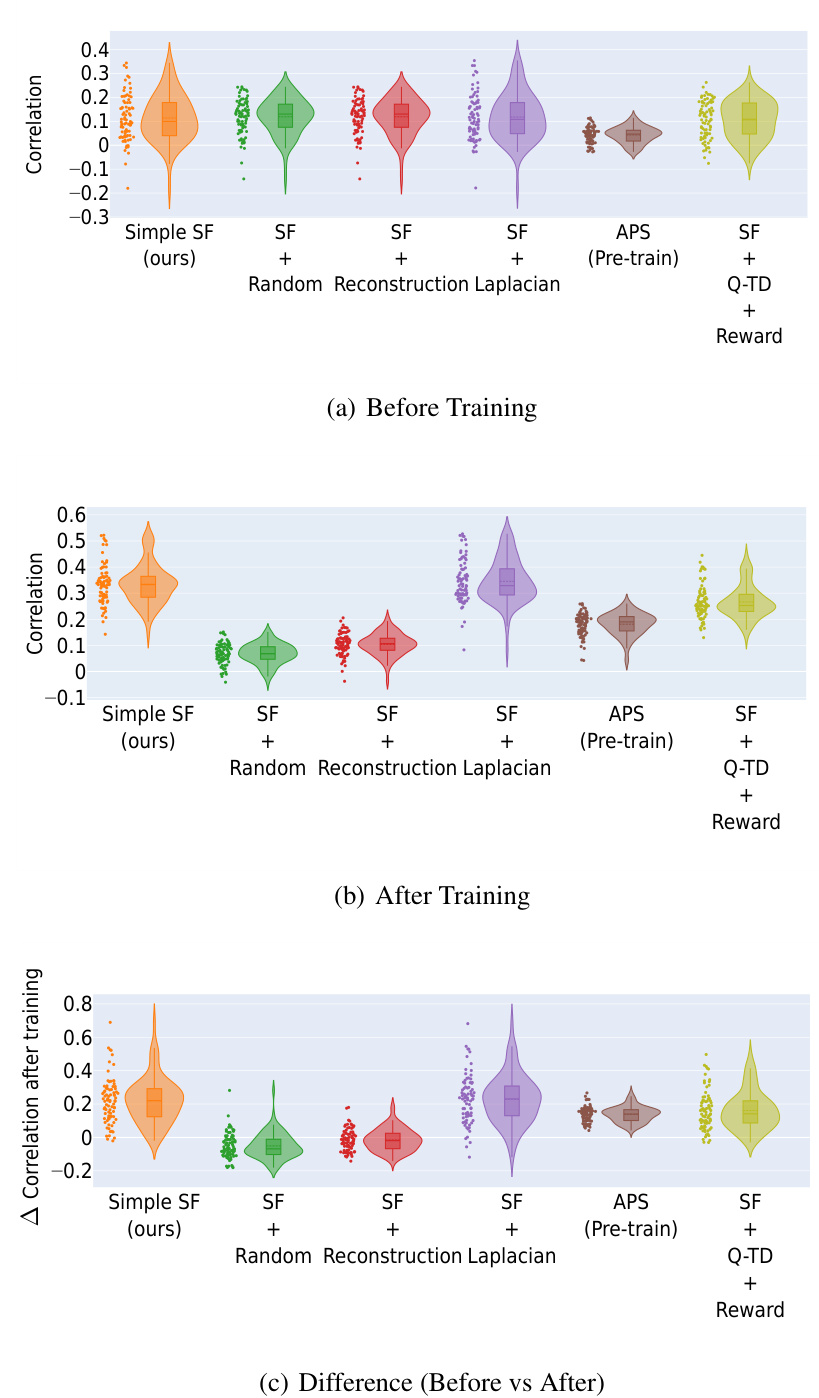

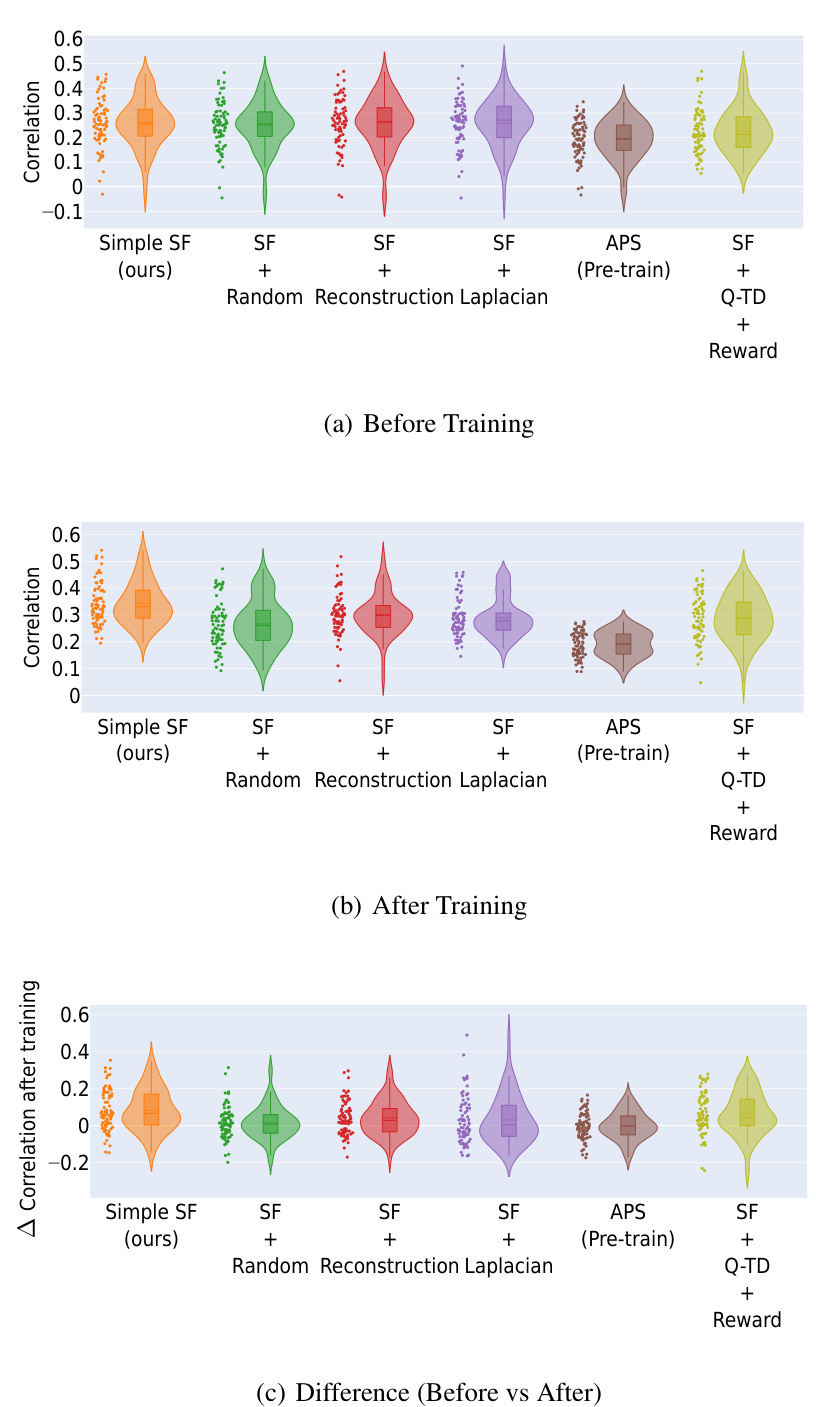

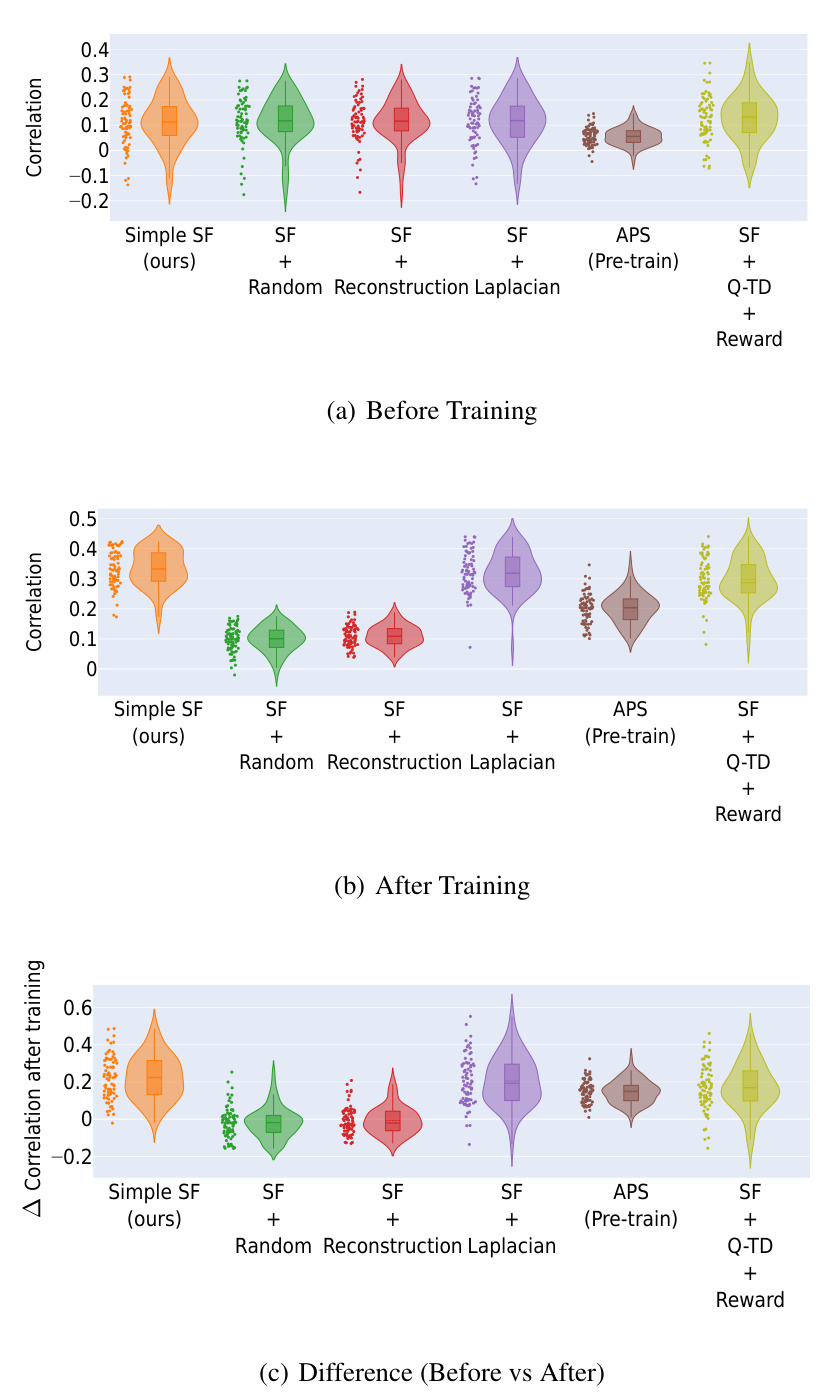

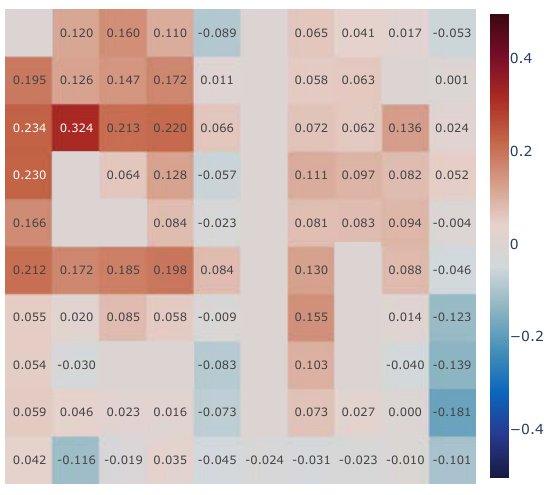

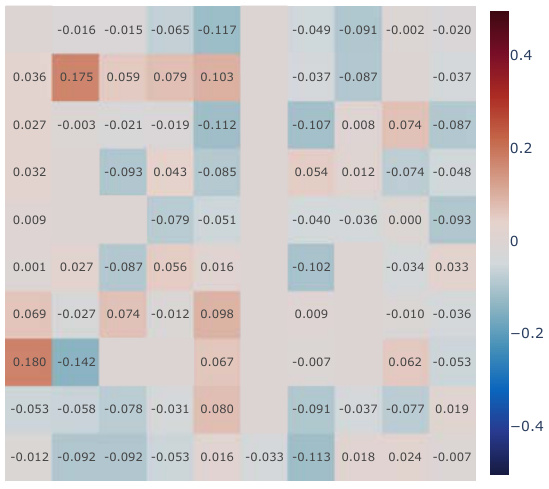

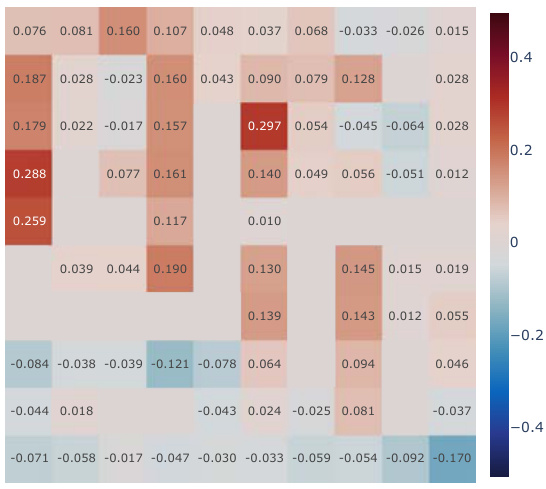

This figure displays the results of a correlation analysis comparing learned Successor Features (SFs) against analytically computed Successor Representations (SRs) for all positions within the Center-Wall environment under partially-observable conditions. Violin plots visually represent the distribution of correlations (Spearman’s rank correlation) across different positions for various methods. The analysis is broken down into three phases: Before Training, After Training, and the difference between these two. The figure shows how the correlation of the different methods change after the training process.

This figure shows the failure of canonical Successor Features learning methods due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of canonical SF learning, (b) shows the cosine similarity converging to 1 (indicating collapse), and (c) illustrates the lack of distinct clusters in the representations using silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments comparing different successor feature learning methods in 2D and 3D environments. The experiments involved two tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset between tasks to simulate a drastic shift in data distribution. The figure displays the total cumulative rewards over training, demonstrating that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method outperforms existing techniques, especially those that include additional constraints on the features.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of this method in a simple 2D environment. Panel (b) shows that the cosine similarity between learned representations converges to 1, indicating collapse. Panel (c) shows that the learned representations do not form distinct clusters, further supporting the collapse.

This figure presents a correlation analysis comparing learned Successor Features (SFs) against analytically computed Successor Representations (SRs) for all positions within a partially-observable Center-Wall environment. The analysis is broken down into three stages: before training, after training, and the difference between those two stages, to show how well the learned SFs capture the transition dynamics of the environment. Violin plots illustrate the distribution of correlations across positions, offering insights into how well various models learn to capture those environmental dynamics.

This figure shows the failure of canonical Successor Feature learning methods due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of this method in a 2D environment, while panels (b) and (c) provide further evidence through cosine similarity and clustering metrics, respectively. A mathematical proof of the collapse is included in the paper.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Features learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance in a 2D environment. Panel (b) demonstrates representation collapse by showing that the cosine similarity between pairs of SFs approaches 1. Panel (c) shows that the learned representations fail to form distinct clusters, confirming representation collapse. A mathematical proof of this collapse is provided in section 3.4.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Features learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a simple 2D environment. Panel (b) shows that the learned representations degenerate, with all states being represented similarly. Finally, Panel (c) quantitatively shows that the representations do not form distinct clusters, further supporting representation collapse.

This figure displays the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments in 2D and 3D environments. Three scenarios are shown: Center-Wall (egocentric and allocentric views), and 3D Four Rooms (egocentric view). The x-axis represents training steps, and the y-axis represents the cumulative total return. The authors’ method (Simple SF, orange) is compared to Deep Q-Network (DQN, blue) and other successor feature (SF) methods that include additional constraints (reconstruction, orthogonality). The Simple SF method outperforms all other methods.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Features (SFs) learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a 2D environment. Panel (b) shows that the cosine similarity between pairs of SFs converges to 1, indicating representation collapse. Panel (c) demonstrates that distinct clusters are not formed in the representations, further supporting representation collapse.

This figure shows a correlation analysis between learned Successor Features and analytically computed Successor Representations for all positions within the Center-Wall environment. The analysis is performed under partially observable conditions. The figure likely presents violin plots visualizing the distribution of correlation values for various algorithms (including the authors’ proposed method), categorized by different stages (before training, after training, and the change). This analysis helps assess how well the learned Successor Features capture the actual Successor Representation and evaluate the effectiveness of different learning methods.

The figure shows two layouts of the Center-Wall environment in a 2D Minigrid. In Task 1, a passage is located at the bottom and the goal is at the top left. In Task 2, the passage moves to the top and the goal moves to the bottom right. The geospatial color mapping aids visualization by showing spatial positioning in the environment. This mapping is particularly useful in the 2D visualization of Successor Features and DQN Representations, showing how agents interpret and navigate the modified environment.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments in 2D and 3D environments. Three different scenarios are shown, each with two tasks repeated twice. The results demonstrate that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method outperforms other methods, especially those with constraints on basis features, showing better transfer learning and higher cumulative rewards across tasks.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments in 2D and 3D environments. Three different scenarios are presented: a two-room environment with egocentric and allocentric observations, and a 3D four-room environment with egocentric observations. In each scenario, the agents are trained on two sequential tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset at each task transition to simulate drastic distribution shifts. The figure demonstrates that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method (orange) outperforms both the Deep Q-Network (DQN) baseline (blue) and other Successor Feature (SF) methods with additional constraints, showcasing its superiority in continual learning settings.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a simple 2D environment. Panel (b) shows that the cosine similarity between pairs of SFs converges to 1, indicating representation collapse. Panel (c) shows that the canonical method does not form distinct clusters, confirming representation collapse. A mathematical proof of this phenomenon is provided in section 3.4.

The figure shows the layout of the Center-Wall environment in 2D Minigrid for two different tasks. Task 1 has a passage at the bottom, with the goal at the top-left. In Task 2, the passage is at the top, and the goal is at the bottom-right. The geospatial color mapping in the third subfigure is provided to aid in visualizing how the agent navigates and interprets the environment. This color map is consistent for Task 1, highlighting changes in agent position in relation to the environment.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments in 2D and 3D environments. Three different tasks were performed sequentially, each repeated twice. The cumulative returns show that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method significantly outperforms other methods, including Deep Q-Networks (DQN) and methods using additional constraints that prevent representational collapse (e.g., reconstruction, orthogonality). The results highlight that adding constraints to prevent representational collapse can negatively impact performance.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Feature (SF) learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical SF learning approach in a simple 2D environment. Panels (b) and (c) provide further evidence of the collapse by showing that the learned representations are highly similar (cosine similarity near 1) and fail to form distinct clusters, as measured by silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores.

This figure displays the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments in 2D and 3D environments using pixel observations. Three different scenarios are presented: a 2D Minigrid environment with egocentric and allocentric observations, and a 3D Four Rooms environment with egocentric observations. The experiments involve two sequential tasks, each repeated twice with a reset of the replay buffer between tasks. The results show the total cumulative reward accumulated during training. The proposed method (‘Simple SF’, orange) significantly outperforms DQN (blue) and other methods that incorporate additional constraints on the successor features. These additional constraints, such as reconstruction and orthogonality, actually hinder performance.

This figure presents a correlation analysis between the learned successor features from our proposed simple method and the analytically computed successor representation (SR). The analysis is conducted in the Center-Wall environment under partially-observable conditions. The heatmaps illustrate the correlation before and after training, along with the difference between them. This visualization effectively demonstrates the spatial distribution of correlation values, providing insights into how the agent’s learned SFs align with the true SR, thereby indicating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper’s experiments: 2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms, and Mujoco. The 2D and 3D environments use discrete actions, while Mujoco uses continuous actions. Importantly, all experiments in the paper used only pixel observations as input.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a 2D environment. Panel (b) shows that the average cosine similarity between pairs of SFs converges to 1, indicating representation collapse. Finally, panel (c) shows that the canonical SFs do not form distinct clusters, which further indicates representation collapse.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning method due to representation collapse. Subfigure (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the method in a simple 2D environment. Subfigures (b) and (c) provide further evidence of the representation collapse using cosine similarity and clustering metrics, respectively. The representation collapse is mathematically proven in Section 3.4.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Features learning approach due to representation collapse. Panel (a) displays the suboptimal performance of this approach in a simple 2D environment. Panel (b) demonstrates the collapse through near-perfect cosine similarity between successor feature vectors after training. Finally, Panel (c) visually confirms the lack of distinct clusters in the learned representations using silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper’s experiments: 2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms, and Mujoco. It highlights that all three environments were tested using only pixel-level observations as input to the agent. The environments vary in complexity, with 2D Minigrid being relatively simple, 3D Four Rooms being more complex, and Mujoco being the most complex due to its continuous action space.

This figure presents a correlation analysis between the Successor Features learned by our proposed model and analytically computed Successor Representations. The analysis is performed for all positions within the Center-Wall environment under a partially-observable scenario. The heatmaps visualize the correlations before and after training, highlighting the improvement achieved by our method. The visualization shows a spatial distribution of correlations, offering insights into how effectively the model represents different areas in the environment.

This figure shows the results of a single task in a 2D two-room environment. Panel (a) compares the performance of the canonical SF learning rule (Eq. 4) against a novel method. Panel (b) shows that the canonical method leads to representation collapse. Panel (c) shows that the canonical method fails to develop distinct clusters in its representations.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning method due to representation collapse. Subfigure (a) shows the poor performance of the canonical method in a simple 2D environment. Subfigures (b) and (c) provide further evidence of the collapse through cosine similarity and clustering metrics, respectively. The authors provide a mathematical proof in the paper that supports their claims.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper’s experiments. The 2D Minigrid environment is a simple grid world with walls and a goal location. The 3D Four Rooms environment is a more complex 3D environment with multiple rooms and a goal location. The Mujoco environment is a physics-based simulation environment. All of the experiments in the paper used pixel observations.

This figure demonstrates the failure of canonical Successor Feature learning methods due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical SF method in a simple 2D environment. Panels (b) and (c) provide quantitative evidence of this collapse by showing that learned representations become highly similar (cosine similarity near 1) and fail to form distinct clusters.

This figure displays the results of a correlation analysis comparing learned Successor Features (SFs) against analytically computed Successor Representations (SRs). The analysis is performed across all spatial positions within the Center-Wall environment under partially-observable conditions. Violin plots illustrate the distribution of correlation values for different SF learning methods (Simple SF, SF + Random, SF + Reconstruction, SF + Orthogonality, APS (Pre-train), SF + Q-TD + Reward) both before and after training. The plot also shows the difference in correlation between before and after training, highlighting the effectiveness of different methods in capturing environment dynamics.

This figure shows that a simple method for learning Successor Features (SFs) from pixel observations leads to representation collapse, which is when different inputs are mapped to the same point in representation space. The canonical SF learning rule (Eq. 4) is shown to be suboptimal due to this representation collapse. The figure includes plots showing average episode return, cosine similarity between learned representations, and clustering metrics (silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores) to demonstrate the effects of the representation collapse.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper’s experiments: 2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms, and Mujoco. It highlights that the first two environments use discrete actions, while Mujoco uses continuous actions. Importantly, all experiments in the paper used only pixel observations as input.

This figure shows the results of a continual reinforcement learning experiment using pixel observations in 2D and 3D environments. The experiment consists of two tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset between tasks. The results, shown as total cumulative returns, demonstrate that the proposed Simple SF method (orange) outperforms a Deep Q-Network (DQN, blue) and other methods that include additional constraints (like reconstruction and orthogonality losses), highlighting the benefit of the simpler approach.

This figure presents a correlation analysis between the successor features learned by our model and the analytically computed successor representation in the Center-Wall environment. The heatmaps visualize the correlation before and after training, as well as the difference between these two. The color intensity represents the correlation strength. In the partially-observable scenario, this analysis reveals the ability of our model to capture spatial relations during learning.

This figure shows the results of a continual reinforcement learning experiment comparing different successor feature (SF) learning methods. Three environments are used: a 2D two-room environment, a 3D four-room environment and the Mujoco environment. Each task involves a change in reward locations or dynamics. The results show that the proposed Simple SF method outperforms other SF methods, particularly when constraints like reconstruction and orthogonality are imposed on the basis features. The proposed method also demonstrates better transfer learning to subsequent tasks.

This figure displays the results of a continual reinforcement learning experiment conducted in 2D and 3D environments. The experiment involves two tasks, each repeated twice, with a replay buffer reset between each task. The performance of different agents, including a standard DQN and agents using various Successor Feature learning methods (with added constraints like reconstruction and orthogonality), are compared. The results show that the proposed ‘Simple SF’ approach significantly outperforms other methods in terms of cumulative returns and transfer learning ability between tasks.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper: 2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms, and Mujoco. The 2D and 3D environments use discrete actions, while Mujoco uses continuous actions. The key point highlighted is that all experiments in the paper used only pixel observations as input.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Features (SFs) learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical method in a simple 2D environment. Panel (b) shows that the cosine similarity between pairs of SFs converges to 1, indicating that the representations have collapsed. Panel (c) uses clustering metrics (silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores) to further demonstrate the collapse. The mathematical proof of the collapse is detailed in section 3.4 of the paper.

This figure shows the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments using pixel observations in 2D and 3D environments. The experiment involved two tasks, each repeated twice, with the replay buffer reset between tasks to simulate significant distribution shifts. The graphs display cumulative rewards over training for three different scenarios (Center-Wall egocentric, Center-Wall allocentric, 3D Four Rooms egocentric). The Simple SF (orange) method consistently outperforms DQN (blue) and other methods with added constraints, suggesting that enforcing constraints can negatively impact learning.

This figure shows the results of a continual reinforcement learning experiment conducted in 2D and 3D environments. Three different scenarios are presented, each showing the cumulative reward obtained over two tasks, each repeated twice. The Simple SF method (orange) consistently outperforms other methods (DQN in blue, and other SF approaches), particularly demonstrating better transfer learning. The results highlight that adding constraints, such as reconstruction and orthogonality, can negatively impact performance.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper’s experiments: 2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms, and Mujoco. The 2D and 3D environments use discrete actions, while Mujoco uses continuous actions. All experiments used only pixel observations as input.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of this method on a simple navigation task. Panels (b) and (c) show that the learned representations collapse to a single point, indicated by high cosine similarity and poor clustering quality metrics.

This figure shows the results of a single task in a 2D two-room environment using the canonical Successor Features (SF) learning rule. The results show that the canonical SF learning rule leads to representation collapse, which means that the network maps all inputs to the same point in a high-dimensional representation space. This figure also shows that the average cosine similarity between pairs of SFs converges to 1, which demonstrates representation collapse. Finally, the canonical SF learning rule does not develop distinct clusters in its representations, which again indicates representation collapse.

This figure presents the results of continual reinforcement learning experiments conducted in 2D and 3D environments using pixel observations. Three different scenarios are shown (center-wall egocentric and allocentric, 3D four rooms egocentric) showing cumulative total returns over two sequential tasks. The authors’ proposed method, Simple SF (orange), consistently outperforms other methods, including DQN (blue), highlighting the method’s effectiveness even when faced with drastic changes in the environment, and the detrimental effects of adding constraints on basis features.

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper’s experiments. The 2D Minigrid is a simple grid world environment with discrete actions, while the 3D Four Rooms environment has discrete actions and introduces changes in reward location and dynamics across tasks. Mujoco is a physics-based simulation environment with continuous actions that allows for more complex scenarios and reward structure variations. All experiments use only pixel-level observations.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Features learning method due to representation collapse. Subfigure (a) shows the suboptimal performance of canonical SF learning in a 2D environment. Subfigure (b) shows that the average cosine similarity between learned SFs converges to 1, a strong indicator of representation collapse. Subfigure (c) shows that canonical SF learning doesn’t lead to distinct clusters, further highlighting the representation collapse.

This figure demonstrates the failure of the canonical Successor Features (SFs) learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance in a 2D environment, while (b) shows that the learned representations become highly similar, indicating a collapse. Finally, (c) shows that the learned representations do not form distinct clusters, further supporting the claim of representation collapse. A mathematical proof of this phenomenon is provided in section 3.4 of the paper.

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Features learning method due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical approach in a simple 2D environment. Panels (b) and (c) provide further evidence of the collapse using cosine similarity and cluster quality metrics (silhouette and Davies-Bouldin scores).

This figure shows the three different environments used in the paper’s experiments: 2D Minigrid, 3D Four Rooms, and Mujoco. The 2D and 3D environments use discrete actions, while Mujoco uses continuous actions. All experiments in the paper used only pixel-level observations. The figure visually represents the layouts of each environment, illustrating the different reward structures and dynamic elements (e.g., the ‘slippery’ floor in the Four Rooms environment).

This figure shows the failure of the canonical Successor Feature learning approach due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of this method in a simple 2D environment. Panel (b) demonstrates that representation collapse happens because the cosine similarity between different SFs converges to 1. Panel (c) shows that the canonical method does not produce distinct clusters in representation space, which is another indicator of representation collapse. A mathematical proof is provided in section 3.4 of the paper.

This figure demonstrates the failure of canonical Successor Feature learning methods due to representation collapse. Panel (a) shows the suboptimal performance of the canonical SF approach in a 2D environment. Panels (b) and (c) provide quantitative evidence of this collapse using cosine similarity and clustering metrics, respectively. A mathematical proof of the collapse is referenced.

This figure presents the results of a continual reinforcement learning experiment conducted in 2D and 3D environments. Agents learned to perform two tasks sequentially, with the replay buffer reset between each task to simulate drastic changes in the environment’s distribution. The results show that the proposed method (Simple SF, in orange) consistently outperforms a Deep Q-Network (DQN, in blue) and other SF methods with added constraints (reconstruction and orthogonality). These constraints, while attempting to improve performance, actually hurt performance.

More on tables

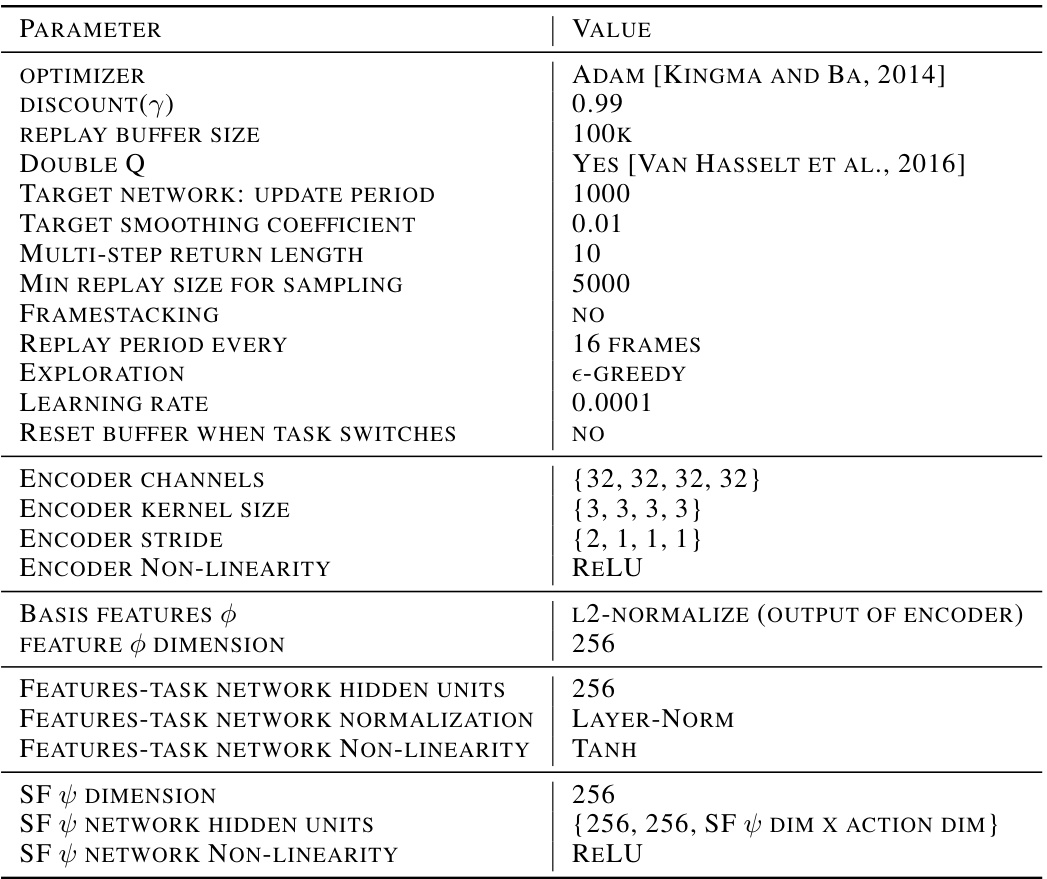

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Simple Successor Features (SFs) model. It specifies details such as the optimizer used (Adam), discount factor (γ), replay buffer size, whether double Q-learning is employed, target network update frequency, target smoothing coefficient, multi-step return length, minimum replay buffer size before sampling, framestacking parameters, replay buffer reset frequency, exploration method, learning rate, and other relevant parameters specific to the encoder, basis features, and the SF network architecture. These hyperparameters were tuned using grid search and five random seeds to optimize the performance of the model in both 2D Minigrid and 3D Four Rooms environments.

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the 2D Minigrid environment experiments. It specifies details such as grid size, observation type (fully or partially observable), whether frame stacking was used, color space (RGB or Greyscale), the number of training frames, number of exposures and tasks per exposure, frames per epoch, batch size, epsilon decay schedule, action repeat, action dimensionality, observation size, maximum frames per episode, and task learning rate.

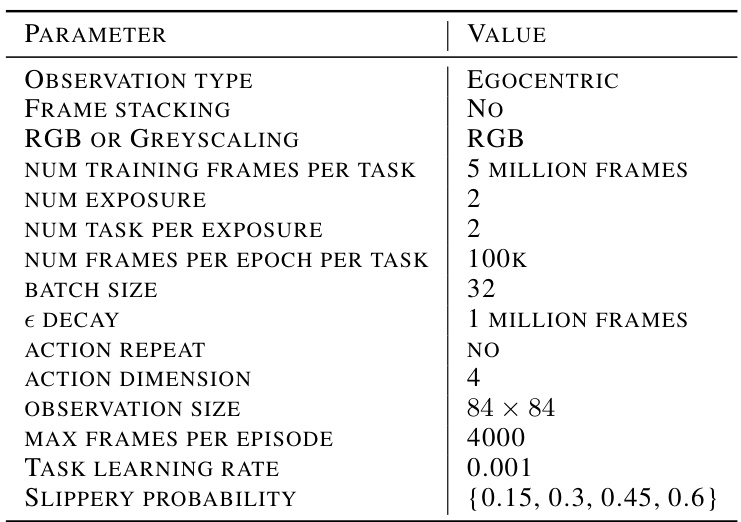

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the 3D Miniworld Four Rooms environment experiments. It specifies details such as observation type (egocentric), whether frame stacking is used, color scheme (RGB), the number of training frames per task, the number of exposures and tasks per exposure, frames per epoch, batch size, epsilon decay schedule, action repeat frequency, action dimensionality, observation size, maximum frames per episode, task learning rate, and the range of slipperiness probabilities tested.

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the Mujoco environment experiments. It includes settings related to frame stacking, color space, training frames per task, the number of exposures and tasks, action repeat frequency, batch size, feature and hidden dimensions, observation size, maximum frames per episode, successor feature dimension, task learning rate, and the frequency of task updates.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the Simple Successor Features (SFs) model. It details the optimizer, discount factor, replay buffer size, target network update settings, exploration strategy, and learning rates. It also specifies the architecture of the encoder (used to extract basis features from observations) and the successor feature network. Different parameters are provided for the encoder and the SF network.

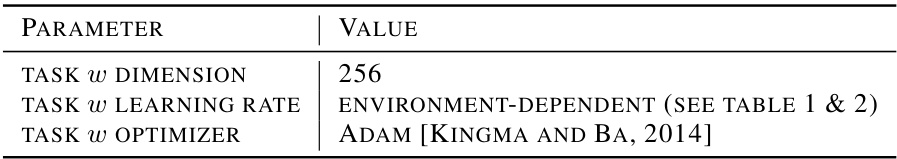

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the task encoding vector w. It includes the dimension of w, the learning rate which is dependent on the environment (see Tables 1 & 2 for details), and the optimizer used (Adam).

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the Simple Successor Feature (SF) model proposed by the authors. It covers optimizer settings, replay buffer details, target network update specifics, exploration strategy, learning rates, and network architecture aspects such as encoder and successor feature network configurations (channels, kernel sizes, non-linearities, etc.).

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the Simple Successor Feature model proposed in the paper. It covers various aspects of the model’s training process, including optimizer, learning rate, replay buffer specifics, and network architecture details (e.g., number of layers, activation functions, normalization methods). The hyperparameter values are listed in the right column.

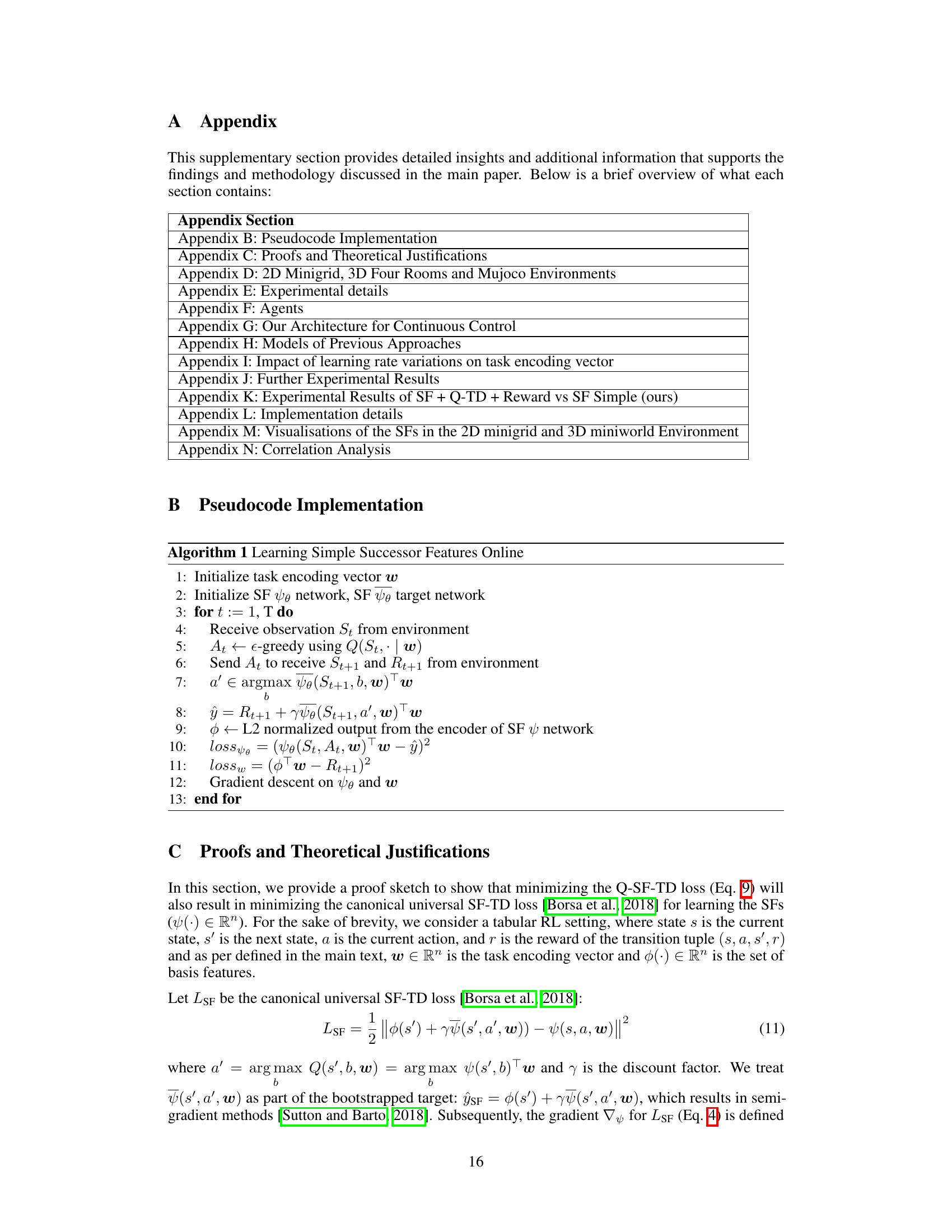

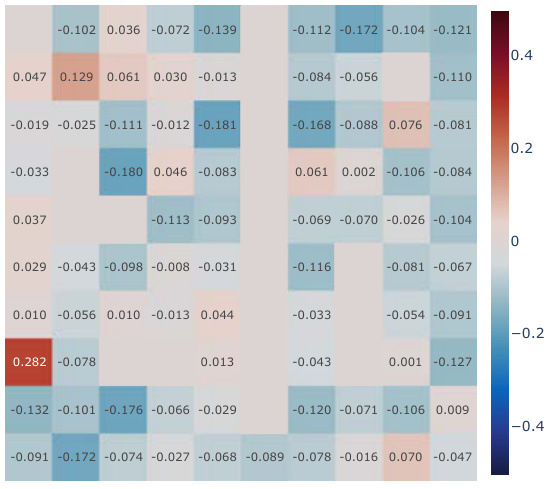

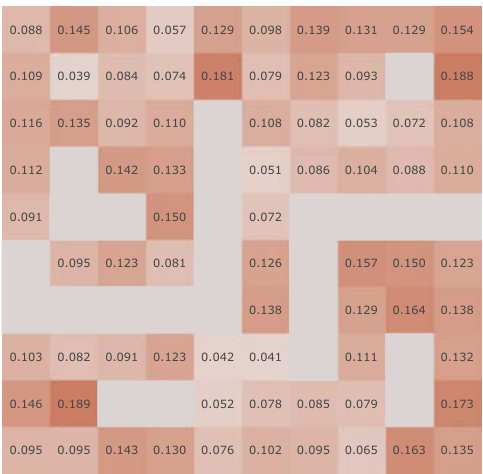

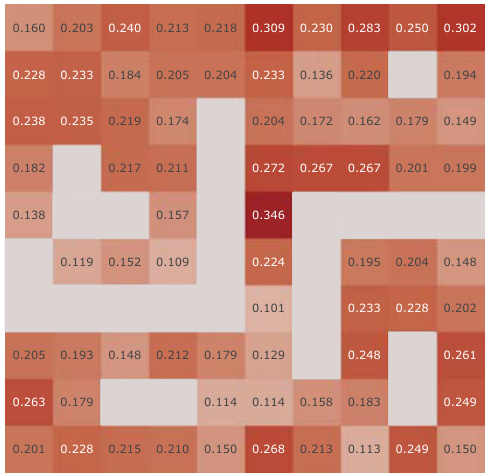

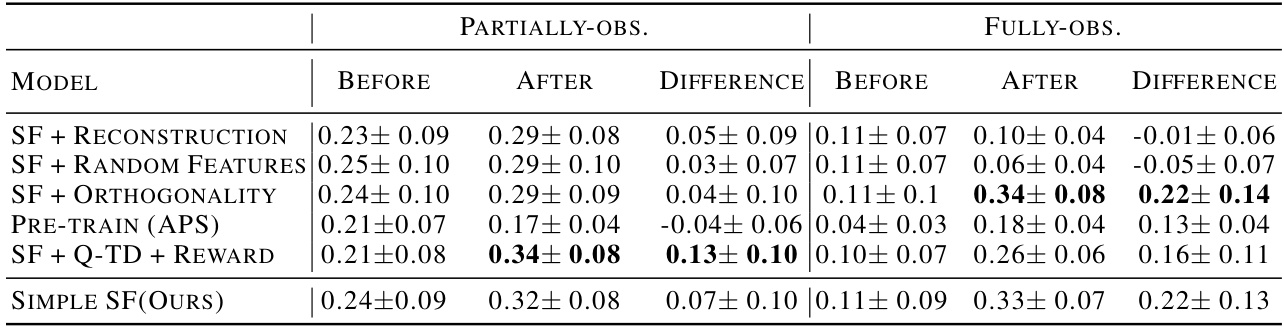

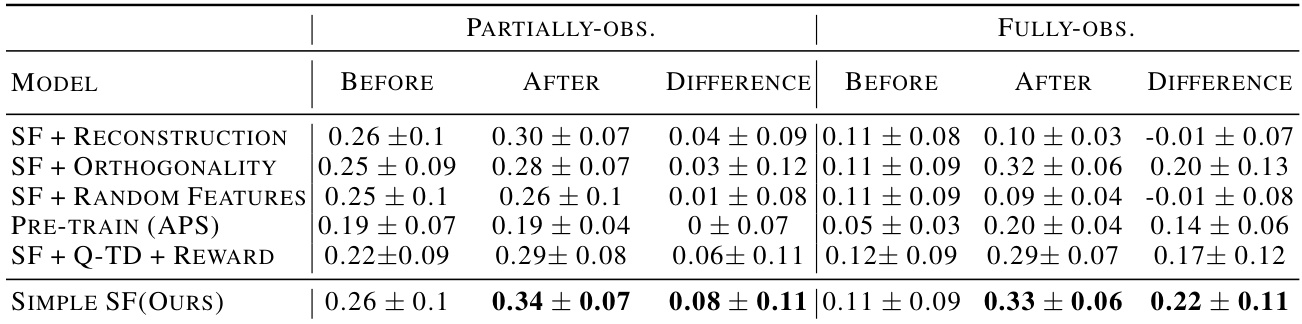

This table presents the results of a correlation analysis comparing analytically computed Successor Representations (SRs) with learned Successor Features (SFs) from different RL agents in the Center-Wall environment. The analysis is broken down by whether the environment was partially or fully observable, and considers three phases: before training, after training, and the change in correlation after training. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the correlation values for each agent and condition, highlighting which agents show the strongest correlation with the SRs, especially after training. The table emphasizes the superior performance of the proposed ‘Simple SF’ method, particularly in partially-observable settings.

This table presents the results of a correlation analysis comparing analytically computed Successor Representations (SRs) with learned Successor Features (SFs) from different reinforcement learning agents. The analysis is performed across two settings: partially observable and fully observable Center-Wall environments. The table displays mean and standard deviations of the Spearman’s rank correlations for three phases: before training, after training, and the difference between them. This allows for a quantitative assessment of how different SF learning methods and their resulting representations compare to the ground-truth SRs. The results highlight the performance of the proposed method in different observation settings and its significant improvement after training compared to baselines, notably in the partially-observable case.

Full paper#