↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Understanding how the brain learns is a fundamental challenge in neuroscience. A key aspect of learning is synaptic plasticity—the ability of connections between neurons to change their strength. Inferring the precise rules governing this change has been incredibly difficult due to the complexity of neural systems and limitations in recording techniques. This is further complicated by the fact that synaptic dynamics are not directly observable, and it remains a major challenge to infer synaptic plasticity rules from experimental data.

This paper introduces a novel computational method to overcome these challenges. The authors developed a model-based inference approach that approximates plasticity rules using parameterized functions, optimizing these parameters to accurately match observed neural activity or behavioral data. This method is validated by successfully recovering established rules, as well as more intricate plasticity rules involving reward modulation and long-term dependencies. Importantly, the application of this technique to real-world behavioral data from Drosophila revealed an active forgetting component in a reward-learning task, which was missed by previous models, improving predictive accuracy. This finding underscores the importance of incorporating active forgetting into our models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is vital for neuroscientists seeking to understand learning mechanisms. It offers a novel, robust method to infer complex synaptic plasticity rules from both neural and behavioral data, opening exciting avenues for creating more biologically realistic AI models and furthering our understanding of the brain. Its impact extends to various fields requiring refined learning algorithms, such as AI and neuromorphic computing.

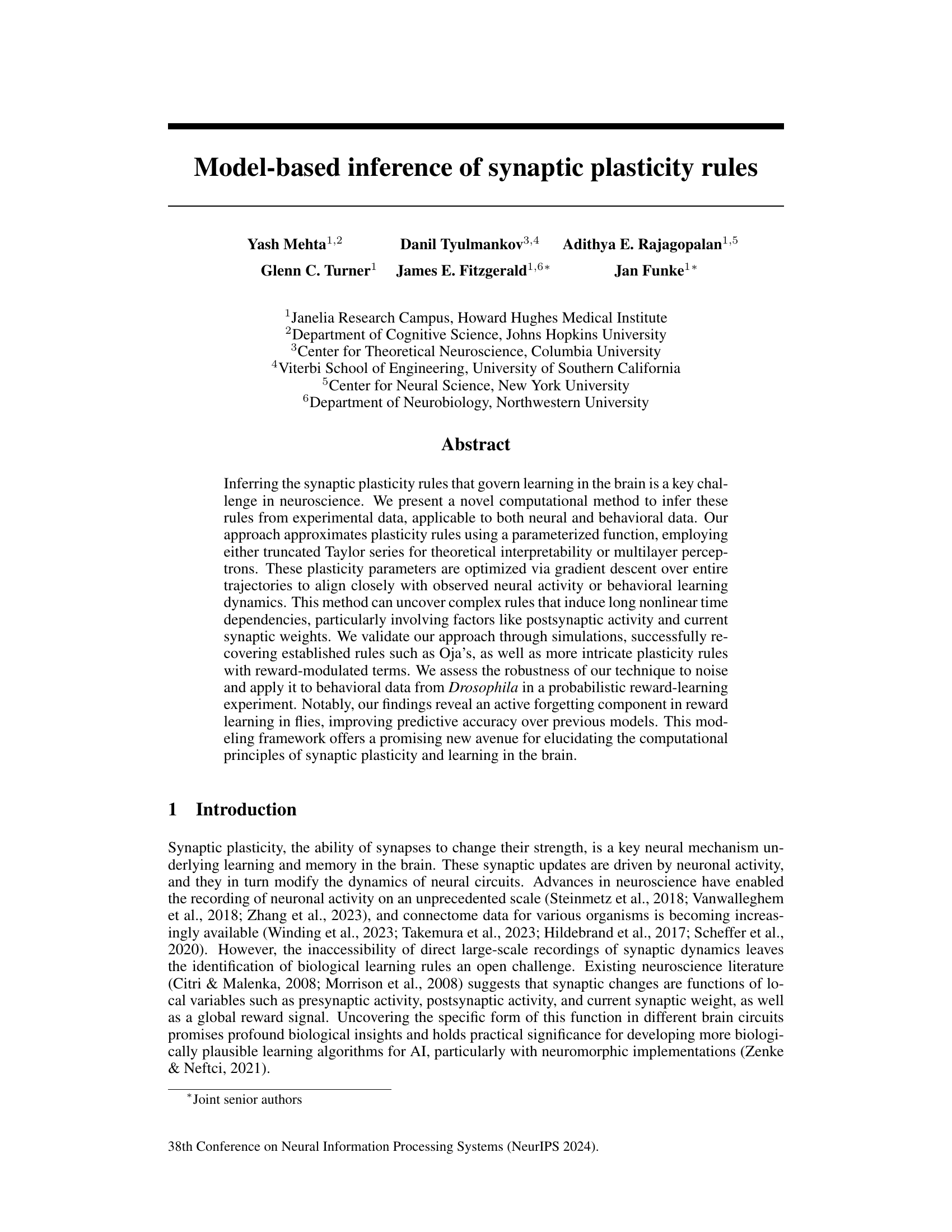

Visual Insights#

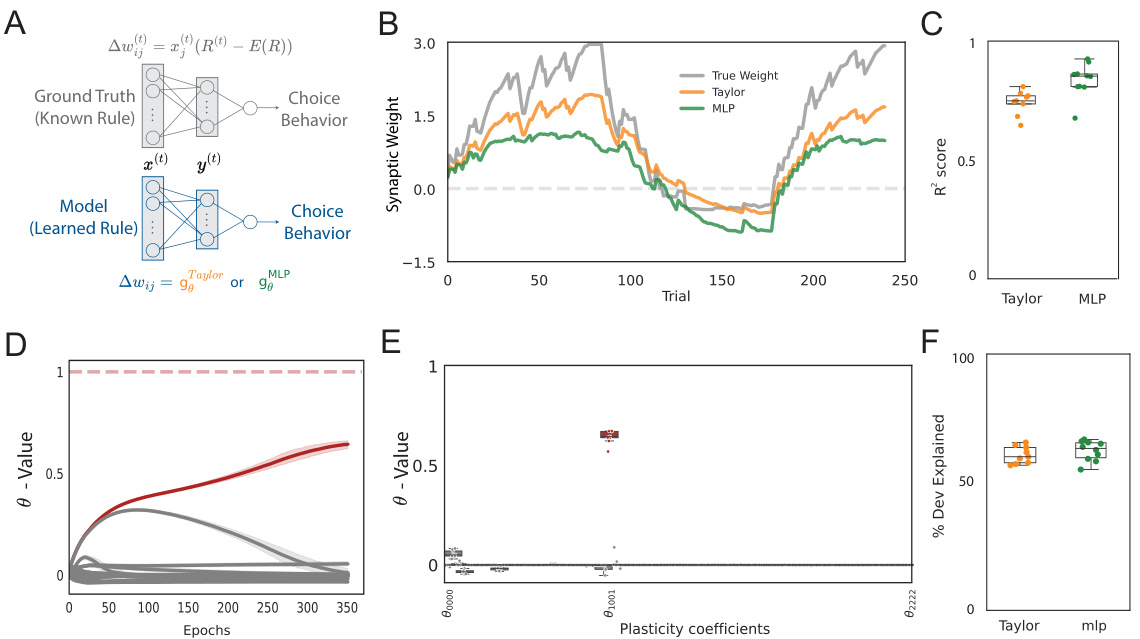

This figure illustrates the model-based inference method for synaptic plasticity rules. Animal-derived time-series data (neural activity or behavioral traces) are compared to the model’s output. A loss function quantifies the difference between the model’s prediction and the actual data, generating a gradient used to optimize the model’s parameters (θ) and infer the underlying synaptic plasticity rule (gθ). The model uses either a parameterized function (e.g., truncated Taylor series) or a neural network to approximate the plasticity rule.

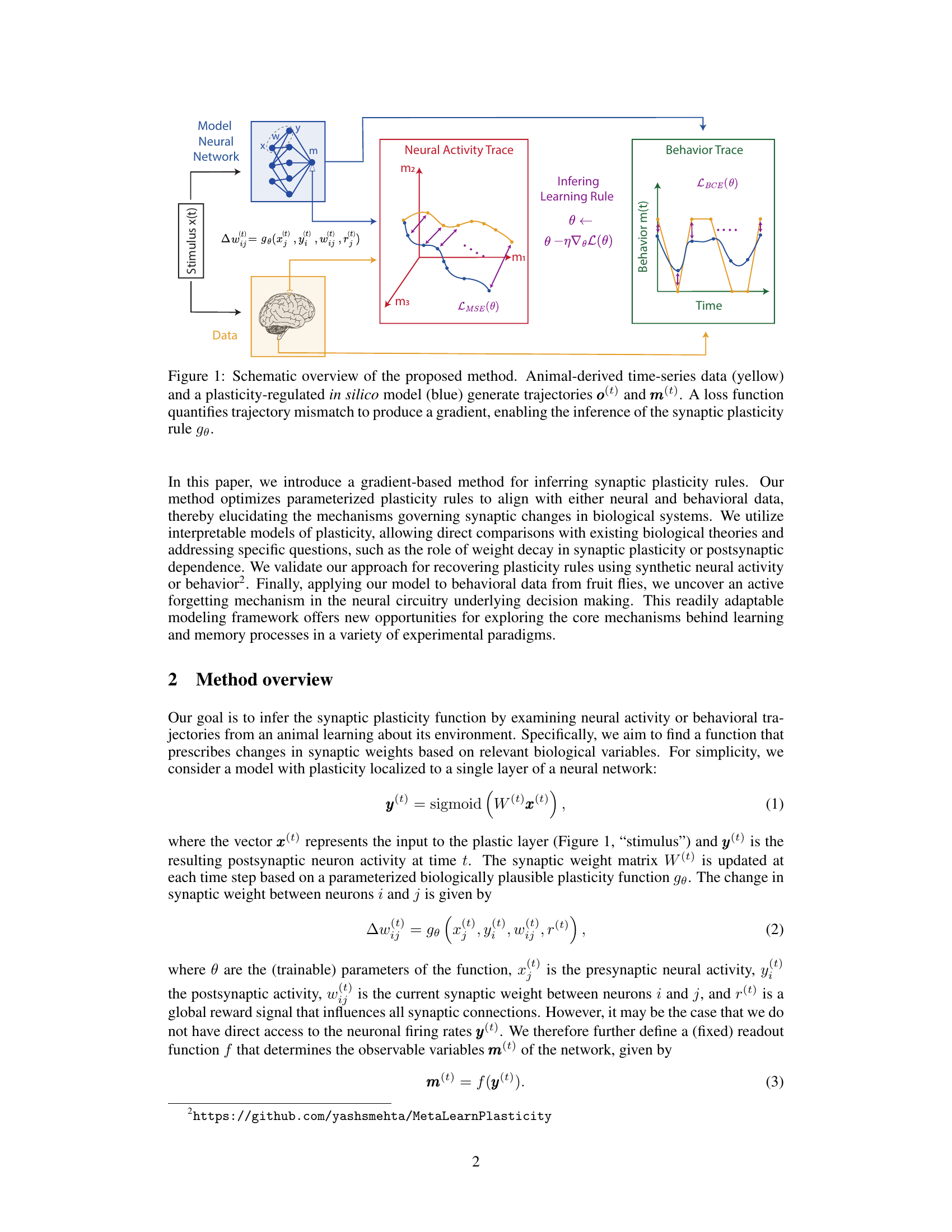

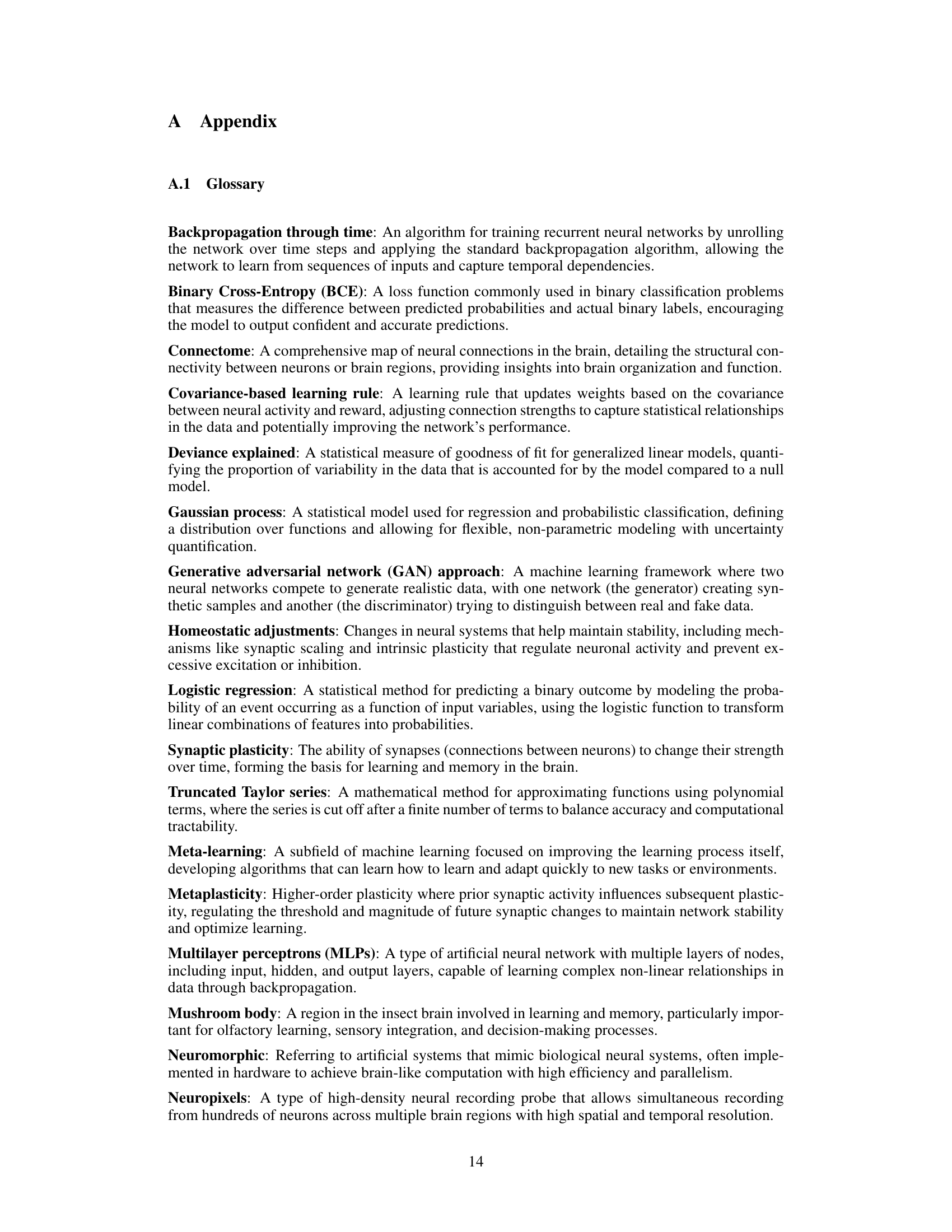

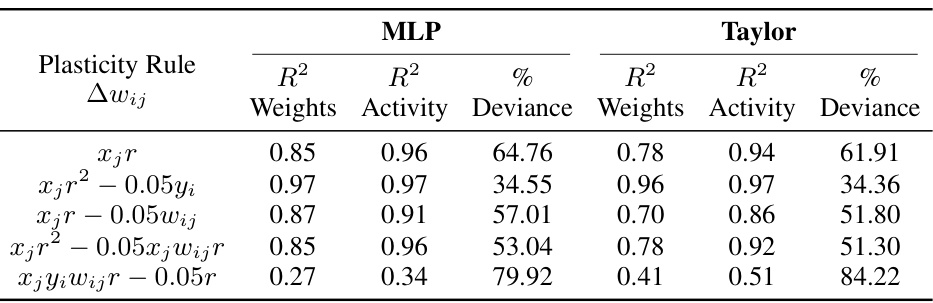

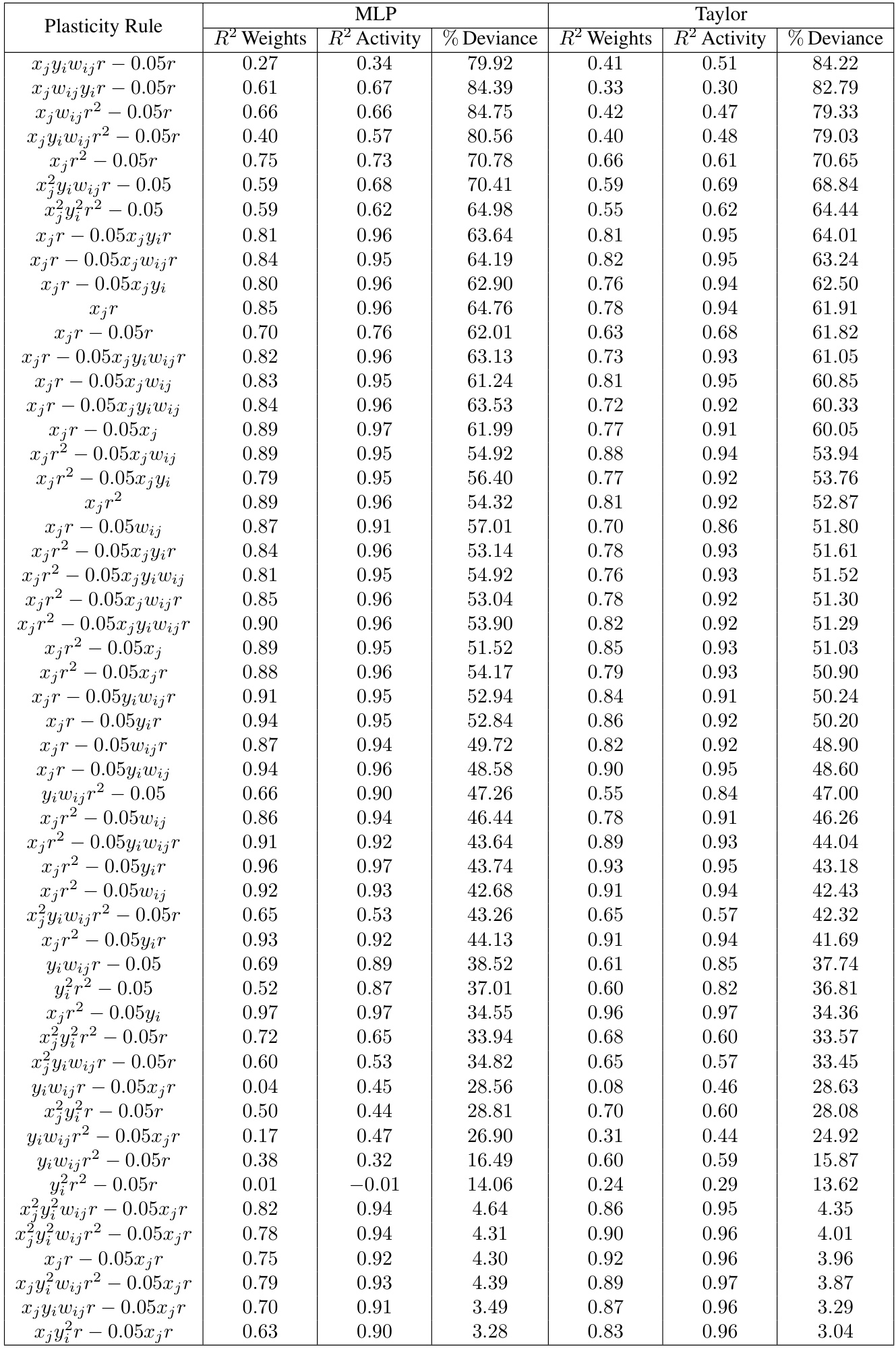

This table presents the performance of different reward-based plasticity rules in terms of R-squared values for weight and neural activity trajectories, and the percentage of deviance explained for behavior. It compares the results obtained using two different models: Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and Taylor series approximation of the plasticity function. The table demonstrates that different plasticity rules yield varying levels of success in predicting both neural and behavioral data. Appendix Table 3 provides a more extensive list of the plasticity rules that were evaluated.

In-depth insights#

Synaptic Plasticity Rules#

The concept of “Synaptic Plasticity Rules” centers on how synapses, the connections between neurons, modify their strength. These rules dictate how learning and memory are encoded in the brain’s neural circuitry. The paper explores computational methods for inferring these rules from experimental data. The core idea is to model synaptic weight changes using parameterized functions, allowing for complex, non-linear relationships between pre- and post-synaptic activity, as well as factors like reward and existing synaptic strength. This modeling framework allows researchers to move beyond simple theoretical models and discover nuanced rules that govern synaptic plasticity. The ability to recover known rules, as well as uncover more complex ones, validates the approach and suggests its potential for advancing neuroscience. A key finding from applying this method to behavioral data in Drosophila is the discovery of an active forgetting mechanism, indicating more sophisticated learning dynamics than previously thought. The implications of these findings extend to understanding learning and memory processes more comprehensively and informing the design of more biologically plausible artificial intelligence algorithms.

Gradient-Based Inference#

Gradient-based inference, in the context of this research paper, represents a powerful computational technique for uncovering the underlying rules governing synaptic plasticity. The approach leverages the concept of gradient descent, an optimization algorithm used to iteratively refine model parameters until an optimal fit with experimental data is achieved. This involves defining a loss function that quantifies the mismatch between the model’s predictions and the observed neural activity or behavioral outcomes. The method’s strength lies in its ability to handle complex, parameterized plasticity rules which can capture long, non-linear dependencies on factors like presynaptic activity, postsynaptic activity, and the current synaptic weight. This approach is validated through simulations where established plasticity rules are successfully recovered, demonstrating its robustness. Furthermore, the application to behavioral data reveals potentially new insights about the mechanisms underlying learning and forgetting, exceeding the performance of previous models. The method’s adaptability, allowing for use with both neural and behavioral data, makes it a valuable tool for future research aimed at understanding synaptic plasticity and learning in the brain.

Oja’s Rule Recovery#

The Oja’s rule recovery experiment is a crucial validation of the proposed method’s ability to infer synaptic plasticity rules. The experiment’s design, using simulated neural activity generated by a known Oja’s rule, allows for a direct comparison between the inferred and ground-truth rules. Successful recovery of the Oja’s rule parameters (θ110 and θ021) demonstrates the method’s capacity to identify established plasticity rules. The assessment of robustness to noise and sparsity in the neural data adds further credence to its reliability in real-world scenarios where data is often incomplete or noisy. The study highlights the technique’s ability to handle complex, nonlinear time dependencies inherent in biological systems, moving beyond simpler linear models. However, the limitations of accurately recovering parameters under high noise and sparsity levels should be noted. This section effectively showcases the method’s strengths and limitations in a controlled environment, providing a solid foundation for applying it to more complex and biologically relevant datasets.

Reward-Based Learning#

Reward-based learning, a core concept in reinforcement learning, is explored in the context of synaptic plasticity. The research delves into how neural circuits adapt to reward signals, uncovering the underlying mechanisms that govern learning and memory. This involves developing computational models to infer synaptic plasticity rules from both neural and behavioral data. The approach uses parameterized functions—either truncated Taylor series or multilayer perceptrons—optimized via gradient descent to match observed behavior. The key finding is the discovery of an active forgetting mechanism alongside the reward learning, suggesting that forgetting isn’t passive but rather an active process regulated by the system. This challenges previous models that omitted this crucial factor, improving the accuracy of the modeling framework. The methodology itself is adaptable to various experimental paradigms, offering a powerful avenue for exploring the computational principles of learning in the brain and other complex systems. Further investigation might explore the interaction between reward prediction error and synaptic weight decay, potentially refining the models to better capture the subtleties of biological learning processes.

Fruit Fly Plasticity#

The research on fruit fly plasticity reveals valuable insights into learning and memory mechanisms. The study leverages a novel computational method to infer synaptic plasticity rules from behavioral data, moving beyond previous limitations of relying solely on neural recordings. This approach allows the exploration of more complex rules, including those with long nonlinear time dependencies, and factors like postsynaptic activity and current synaptic weights. The key finding is the identification of an active forgetting component in reward learning in fruit flies, significantly improving the predictive accuracy of models compared to previous approaches. This active forgetting, potentially driven by a homeostatic weight decay mechanism, suggests a dynamic equilibrium between learning and forgetting, contrary to simpler models that focus solely on learning. This research offers a promising avenue for a more comprehensive understanding of plasticity and its underlying computations, bridging the gap between detailed biological observations and computational modeling.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure demonstrates the recovery of Oja’s plasticity rule from simulated neural activity using the proposed method. Panel A shows a schematic of the models. Panel B shows the mean-squared difference between ground truth and learned synaptic weights over time and training epochs. Panel C shows the evolution of the plasticity rule parameters during training, highlighting the recovery of Oja’s rule values. Panel D shows the R-squared scores for different noise and sparsity levels. Panels E and F show boxplots of the R-squared scores for different noise and sparsity levels. Panel G shows the evolution of learning rule coefficients during training under high noise and sparsity conditions, demonstrating the robustness of the method.

This figure demonstrates the model’s ability to infer reward-based plasticity rules from simulated behavioral data. Panel A shows the model architecture. Panel B compares the evolution of synaptic weights in the ground truth model versus those learned using Taylor series and MLP approaches. Panel C shows the R-squared values indicating the goodness of fit across different simulations. Panel D and E demonstrate the learning dynamics of parameters in the inferred model, while Panel F displays the overall model fit to the ground truth behavioral data.

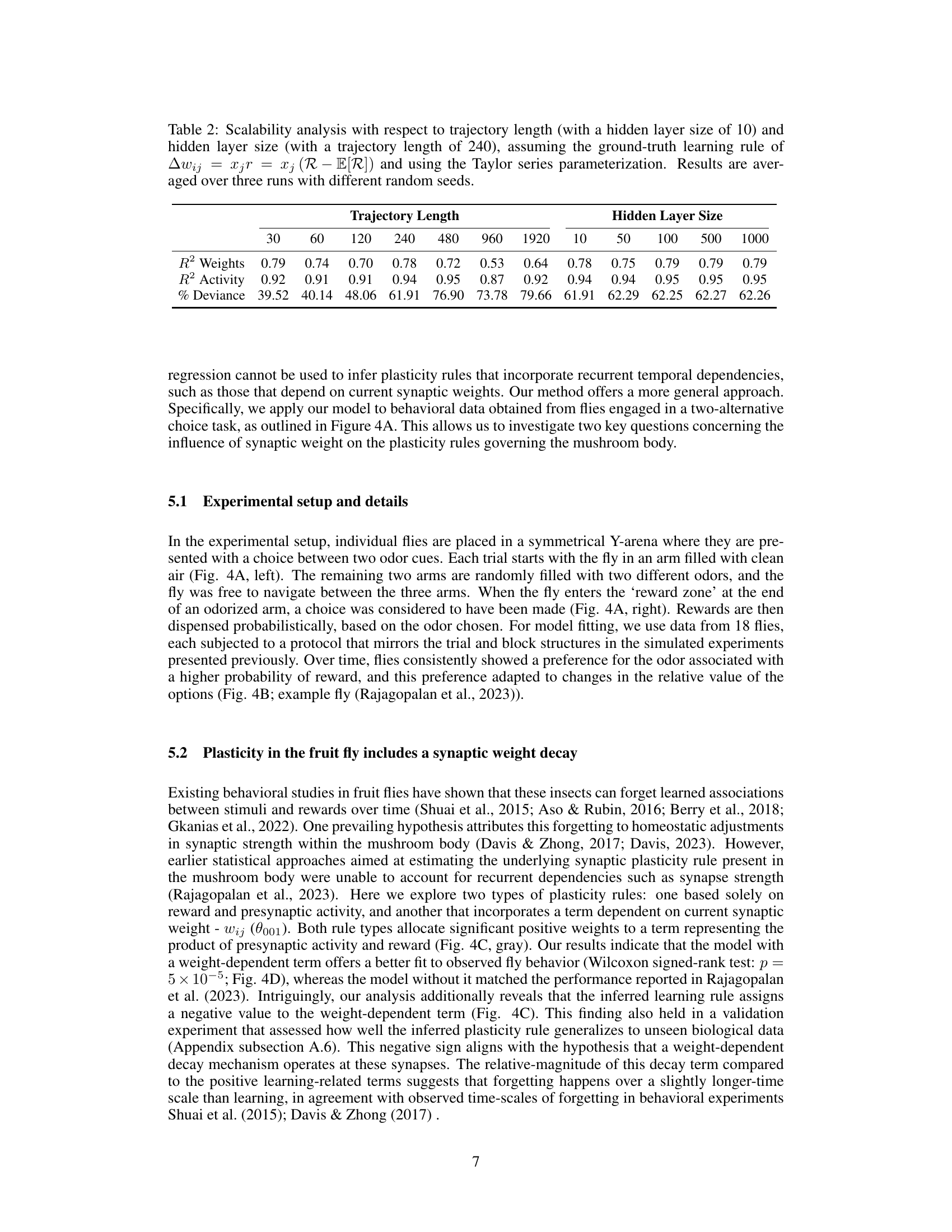

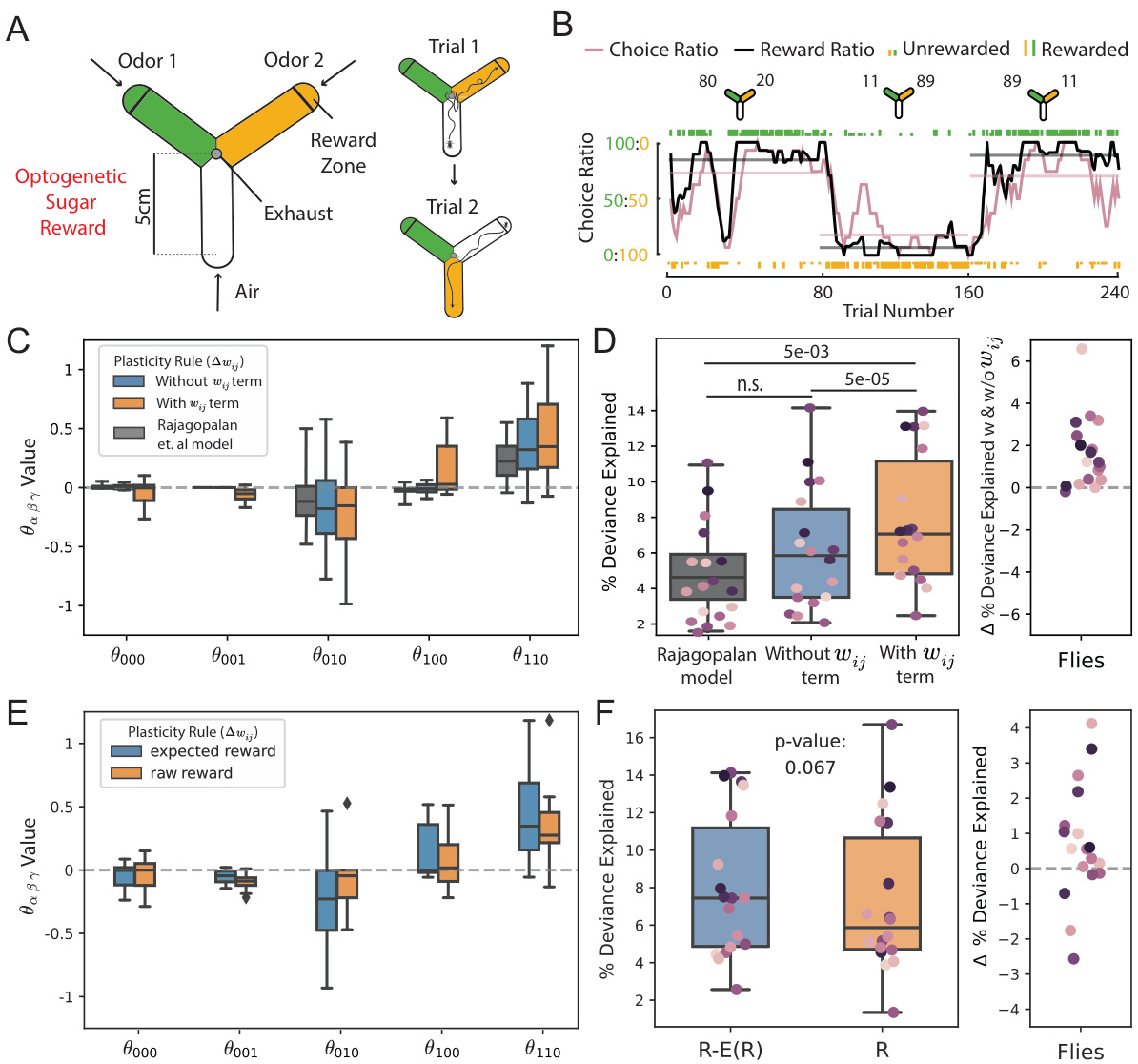

This figure demonstrates the application of the proposed method to real behavioral data from Drosophila flies performing a two-alternative choice task. It shows the experimental setup, an example fly’s behavior, the inferred plasticity rule parameters, and a comparison of model fits with and without a weight-dependent term and reward expectation. The results highlight the importance of incorporating both weight-dependent decay and reward expectation to accurately model the learning process in flies.

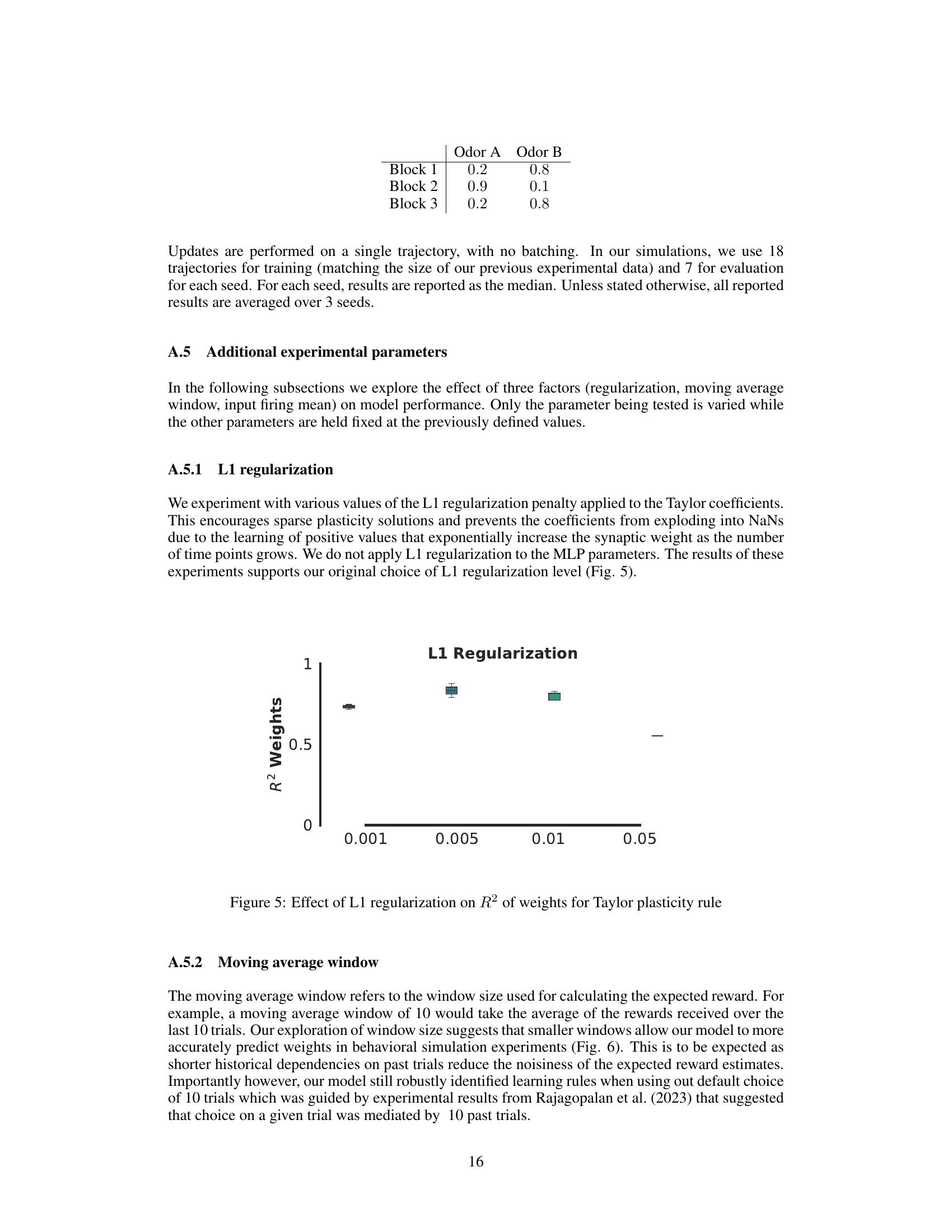

This figure shows the effect of different L1 regularization strengths on the performance of the Taylor plasticity rule model. The x-axis represents different L1 regularization values, and the y-axis shows the R-squared values for the model’s weight predictions. The box plot visualization shows the median, quartiles, and potential outliers in the R-squared values for each regularization strength. It helps to determine the optimal level of L1 regularization for this model, balancing model performance and preventing overfitting.

The box plot shows the effect of different moving average window sizes (5, 10, and 20 trials) on the R-squared values for the weights obtained from both Taylor series and MLP models. The results suggest that using smaller moving average windows generally leads to better performance, likely because shorter historical dependencies reduce the noisiness of the expected reward estimates. However, the difference in performance across window sizes is relatively small, indicating that the method is robust to this hyperparameter.

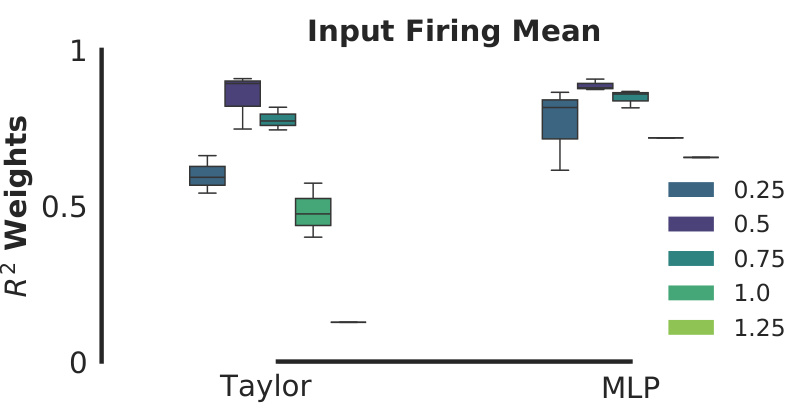

This figure shows the effect of varying the input firing mean (a parameter used to represent odor in the behavioral experiments) on the performance of the learned plasticity rule. The plot displays boxplots of R-squared values for weights, comparing the performance of two plasticity models (Taylor and MLP) under different input firing means (0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, and 1.25). It illustrates the robustness of the models across various input ranges.

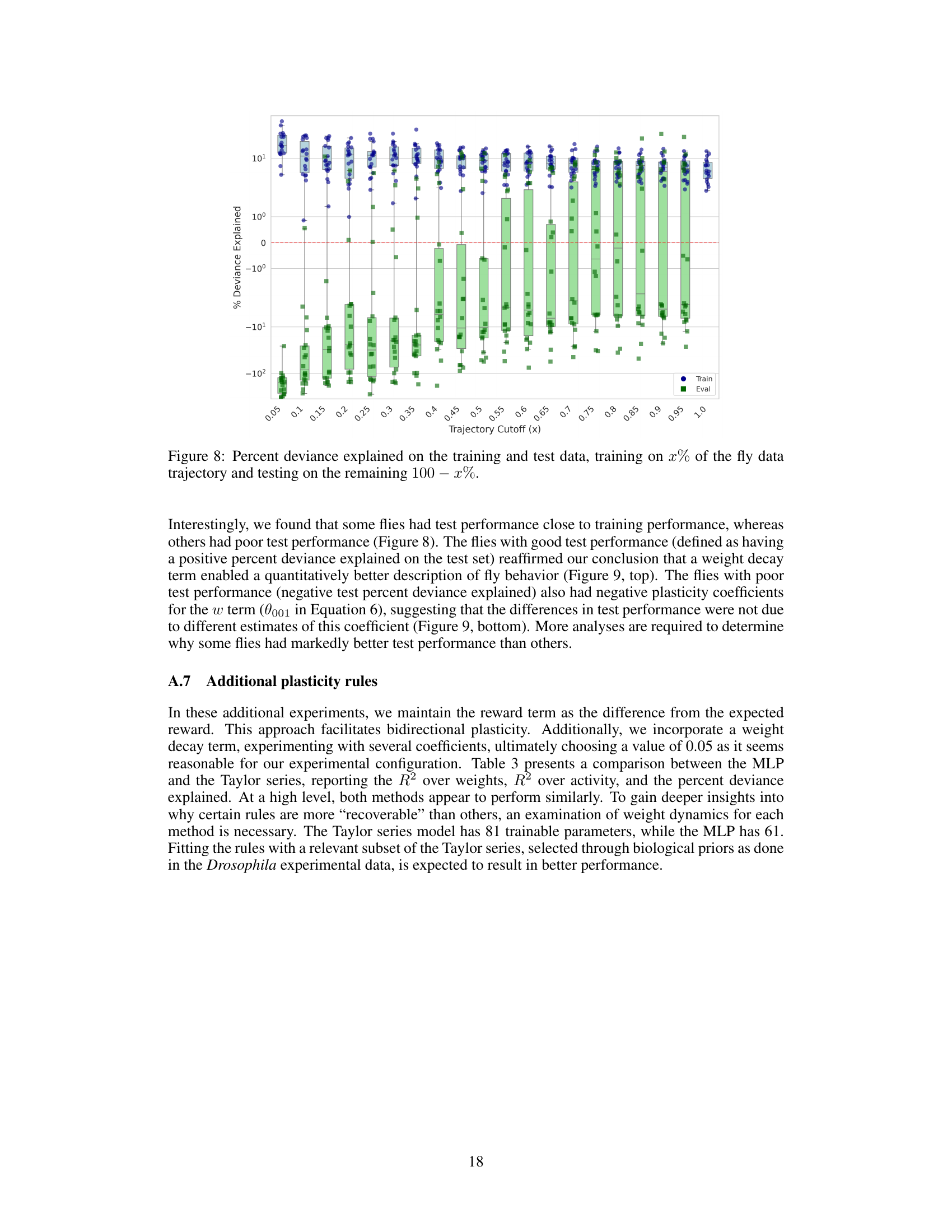

This figure shows the results of a validation experiment performed to evaluate the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. The model was trained using a portion (x%) of each fly’s behavioral trajectory data and then tested on the remaining (100-x%) portion. The x-axis represents the percentage of data used for training, and the y-axis shows the percent deviance explained, a measure of how well the model fits the data. The plot includes boxplots to show the distribution of results across different flies for both training and testing data. The red line indicates zero percent deviance explained. A positive percent deviance explained signifies a good fit to the data, while a negative value indicates a poor fit.

This figure shows the weight decay coefficient (θ₀₀₀₁) learned in the Taylor series parametrized plasticity rule (Equation 6) for flies with positive (top) and negative (bottom) test set percent deviance explained. It illustrates how the model’s performance in predicting fly behavior relates to the learned weight decay term across various training set sizes (trajectory cutoffs). Positive percent deviance explained signifies a good fit between model predictions and observations while negative indicates a poor fit.

More on tables

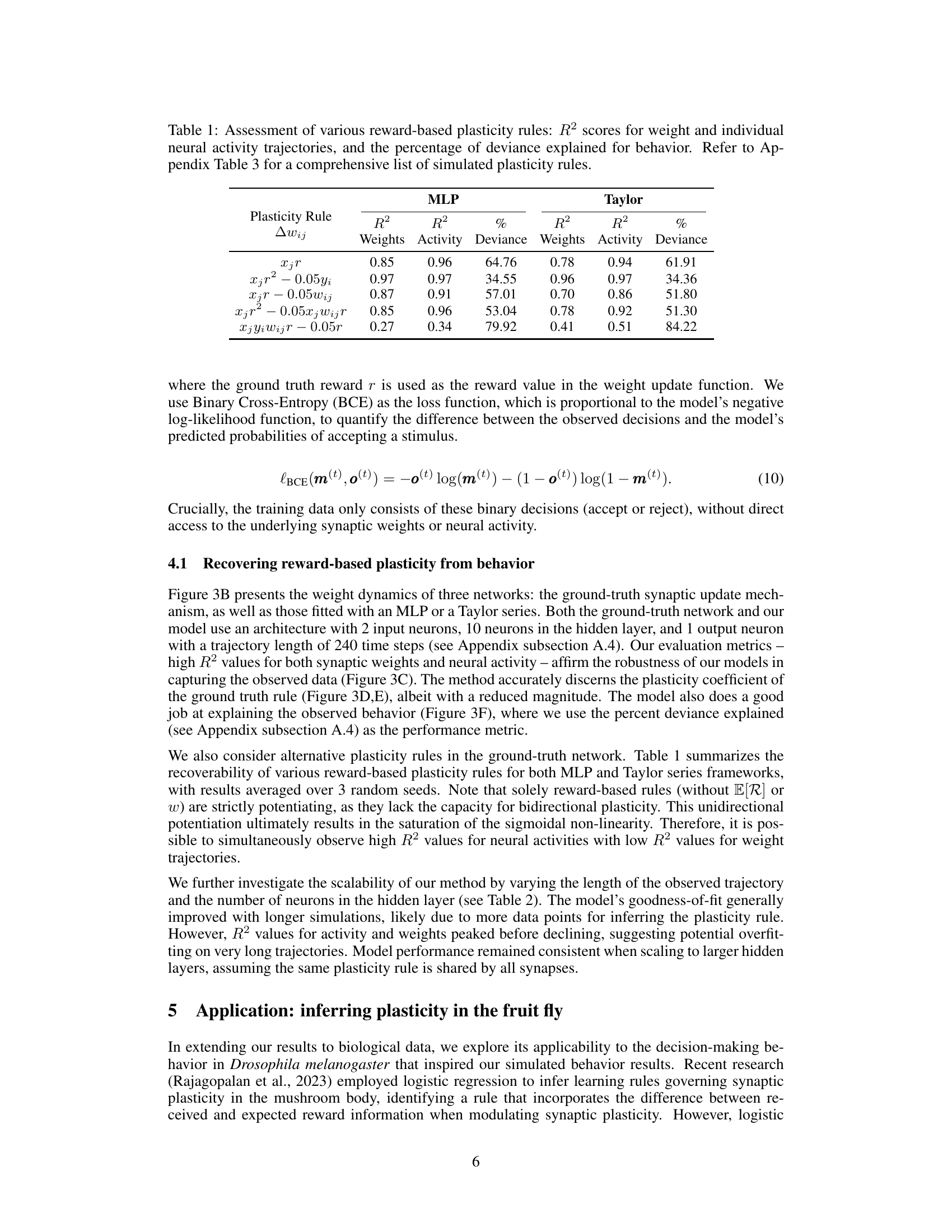

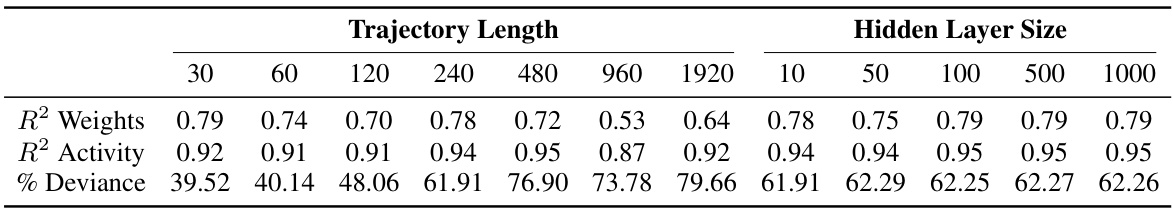

This table shows the scalability of the proposed method for inferring plasticity rules from simulated behavioral data. It demonstrates how the model’s performance (measured by R-squared values for weights and activity, and percentage of deviance explained) changes with varying trajectory lengths and hidden layer sizes in the neural network model. The results suggest the model’s robustness across different scales and parameters, highlighting its generalizability.

This table presents the performance of different reward-based plasticity rules in terms of their ability to explain simulated behavioral data. The rules were evaluated using both MLP and Taylor series models, with R-squared values provided for weight and neural activity trajectories, alongside the percentage of deviance explained for behavior. Appendix Table 3 provides additional detail on the plasticity rules.

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the performance of different reward-based plasticity rules using both MLP and Taylor series models. It shows the R-squared values for weights and neural activity trajectories, along with the percentage of deviance explained for behavior. The purpose is to compare various plasticity functions to determine which model best fits the observed behavior and neural data, identifying the most effective way to incorporate reward information into synaptic plasticity models.

Full paper#