↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are computationally expensive to train and their copyright protection is a growing concern. Existing methods are limited by their inability to uniquely identify the base model, especially after further fine-tuning or modifications. Additionally, many methods either expose sensitive model parameters or interfere with the model’s training process. This creates challenges in practically protecting LLM copyrights.

HuRef, a novel method, addresses these limitations by generating human-readable fingerprints based on stable internal model properties. This is achieved without exposing parameters or hindering training. The system uses three invariant terms that uniquely identify an LLM’s base model, mapping them to a natural image for easy verification. Furthermore, zero-knowledge proofs ensure the authenticity and integrity of these fingerprints. HuRef provides a practical and trustworthy method for LLM copyright protection.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it proposes a novel solution to the crucial problem of LLM copyright protection. It introduces HuRef, a human-readable fingerprint that uniquely identifies the base model of LLMs without revealing sensitive parameters or interfering with training. This addresses a significant challenge in the field and opens new avenues for research in model provenance and copyright enforcement. The use of zero-knowledge proofs enhances trustworthiness and practicality.

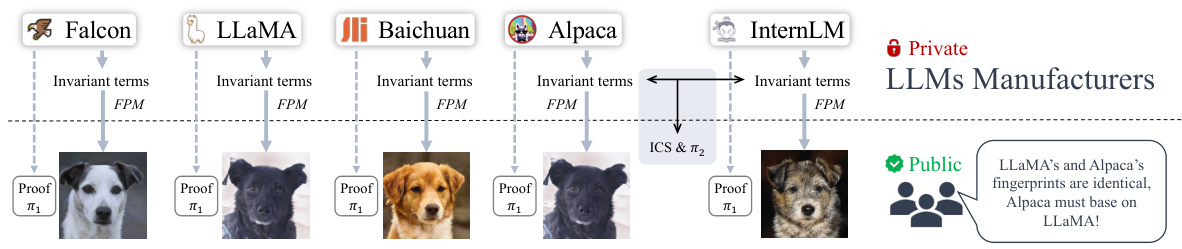

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the proposed framework for protecting LLMs using fingerprints. LLM manufacturers compute invariant terms from their models’ parameters, which are then fed into a fingerprinting model (FPM). The FPM generates a fingerprint image, which along with zero-knowledge proofs, is released publicly. This allows anyone to easily compare fingerprint images to identify LLMs sharing a common base model. A secondary, limited one-to-one comparison scheme is also included to provide further verification. The zero-knowledge proof ensures the integrity of the fingerprints and comparisons without revealing sensitive model information.

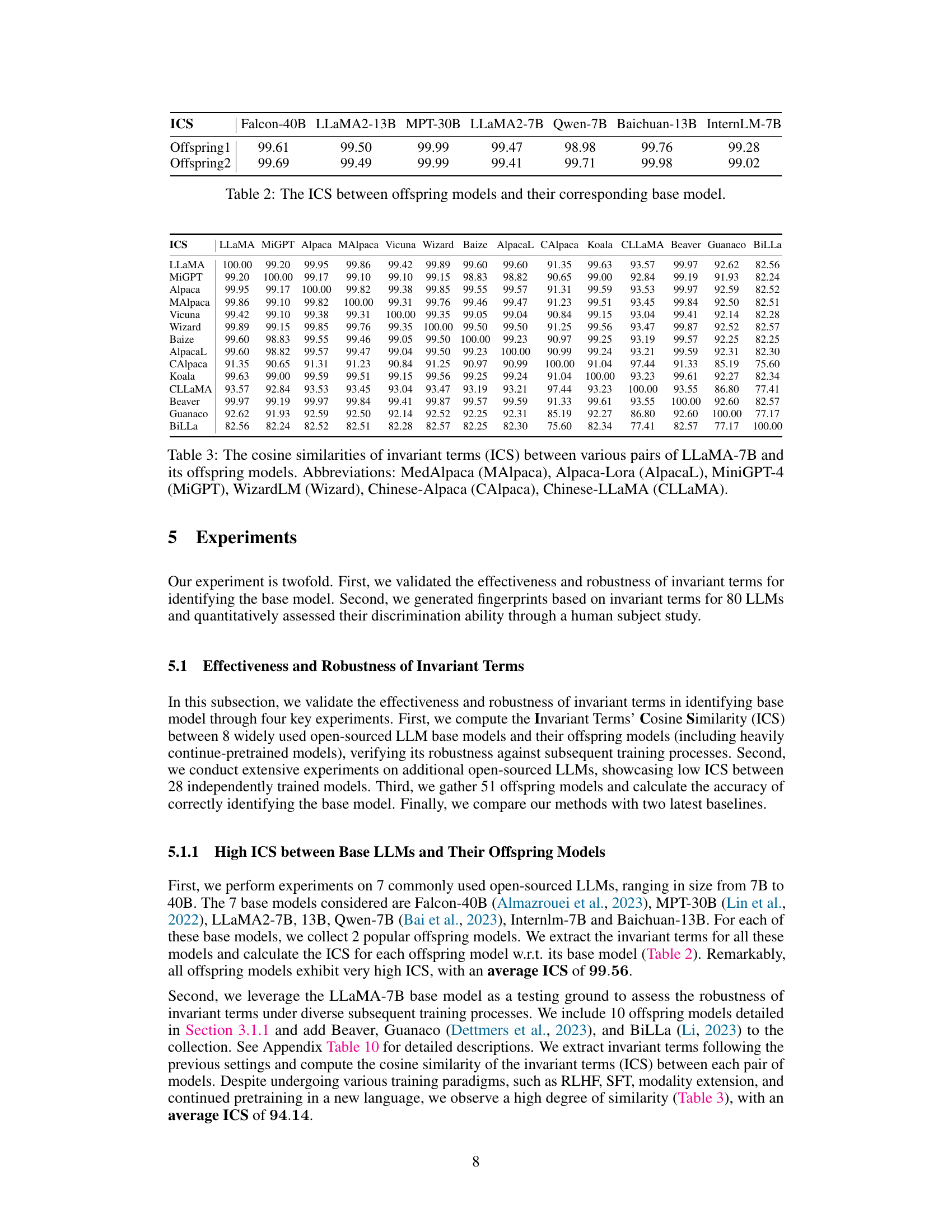

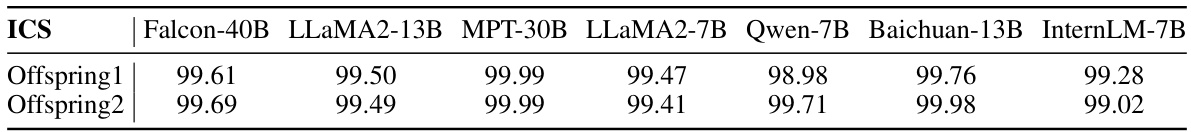

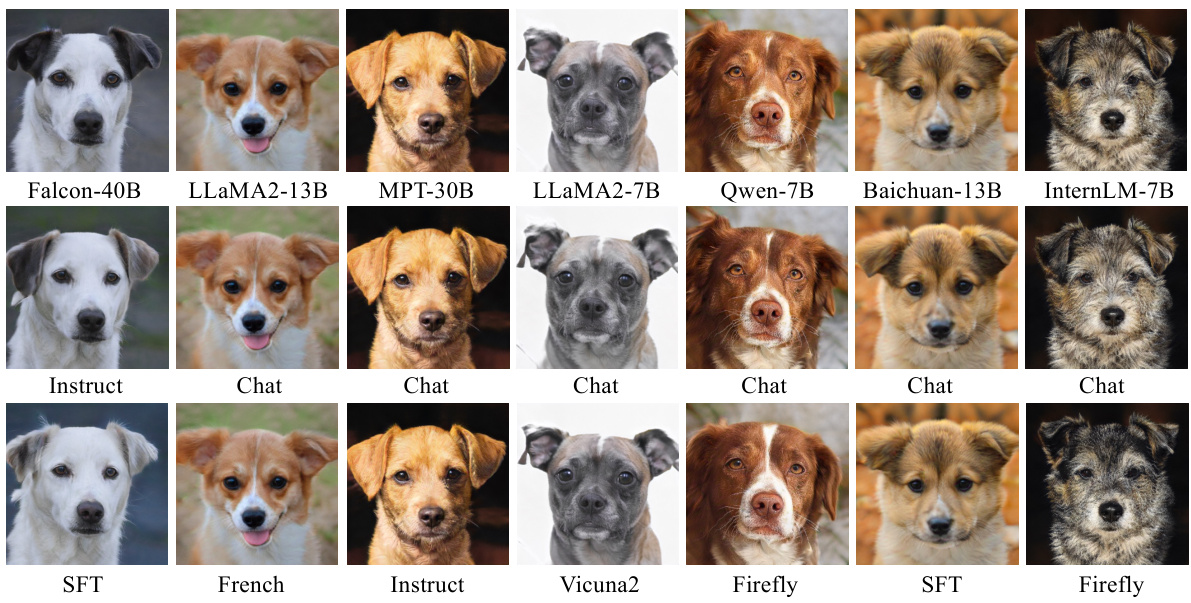

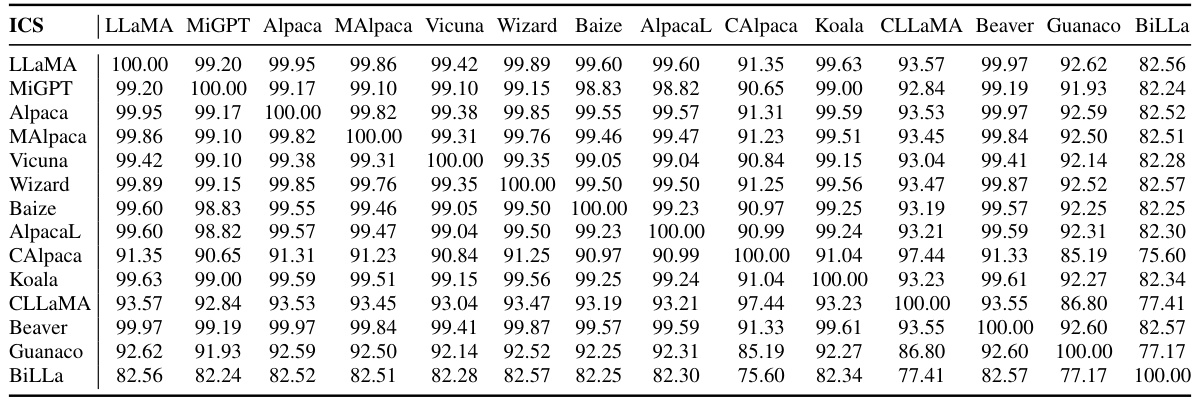

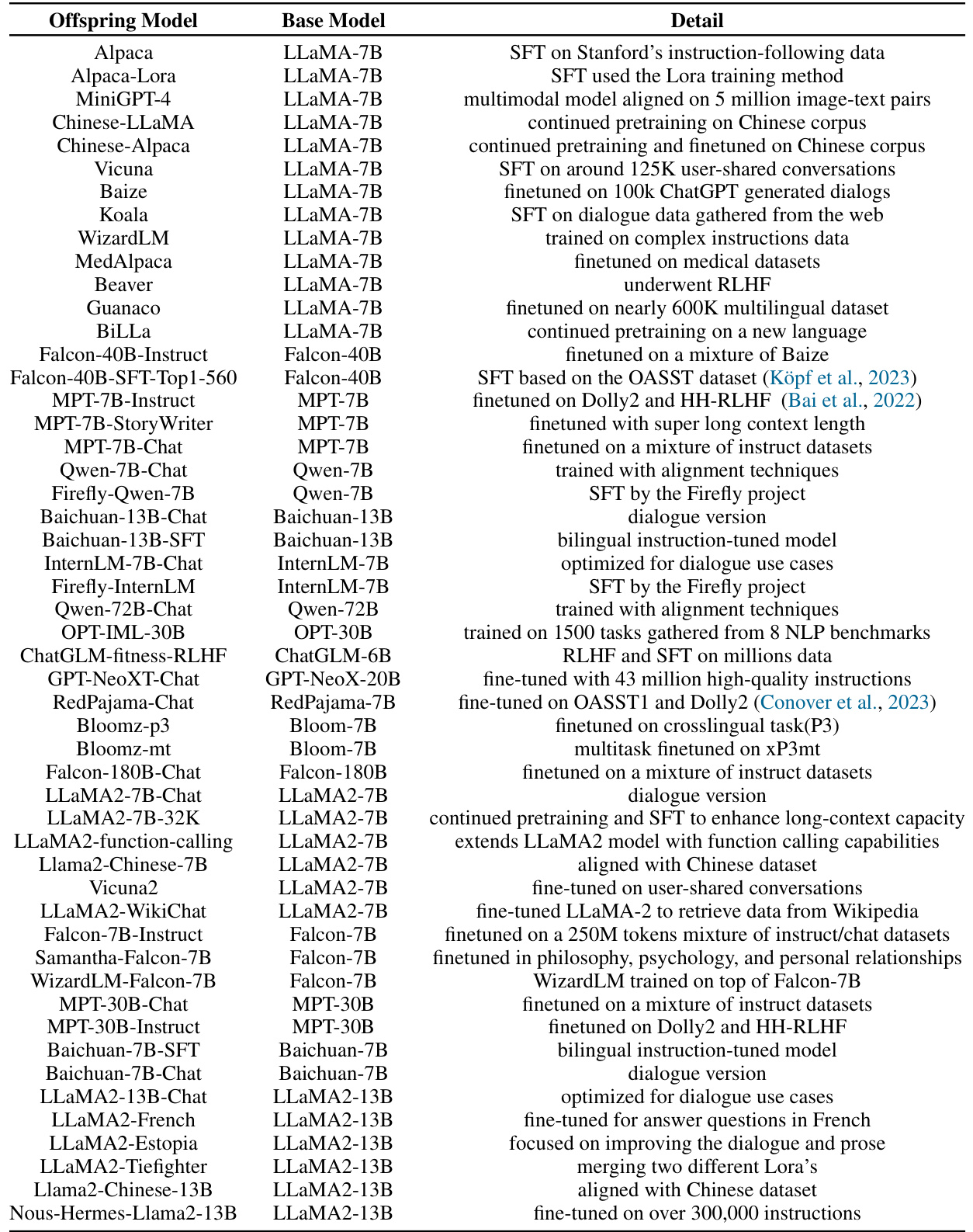

This table displays the Invariant Terms’ Cosine Similarity (ICS) scores between various offspring LLMs and their corresponding base models. The offspring models were derived from seven base models: Falcon-40B, LLaMA2-13B, MPT-30B, LLaMA2-7B, Qwen-7B, Baichuan-13B, and InternLM-7B. For each base model, two offspring models are included, representing different training paradigms or modifications. The high ICS scores indicate that the parameter vector direction of the base model remains largely stable across various offspring models, despite subsequent training steps.

In-depth insights#

LLM Fingerprint#

The concept of “LLM Fingerprint” in research papers centers on the challenge of copyright protection for Large Language Models (LLMs). LLMs are computationally expensive to train, making their unauthorized copying a significant concern. A fingerprint acts as a unique identifier, allowing for the detection of the original base model even after modifications like fine-tuning or parameter alterations. Ideal fingerprints should be robust to such changes, while being easily verifiable without exposing model parameters publicly. Research often involves exploring methods to generate these fingerprints, focusing on features that remain stable across various training phases. Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) is frequently integrated to ensure the fingerprint’s authenticity, guaranteeing its honest generation without compromising the model’s secrecy. The effectiveness and security of any proposed method are typically evaluated against various attacks designed to manipulate or disguise the fingerprint. The balance between robustness, verifiability, and security is crucial in LLM fingerprint research.

Invariant Terms#

The concept of “Invariant Terms” in the context of a research paper on Large Language Model (LLM) fingerprinting is crucial for robust copyright protection. These terms, derived from the LLM’s internal parameters, must remain stable across various training stages. This stability is essential because LLMs often undergo multiple training phases, including fine-tuning and reinforcement learning, which could alter parameters. The invariance ensures that the fingerprint generated from these terms reliably identifies the base LLM despite such modifications. The paper highlights the vulnerability of simple parameter vector directions to attacks, such as permutation or matrix rotation. Therefore, the identification of invariant terms resistant to these attacks is key to generating a reliable and unalterable fingerprint, allowing for reliable LLM provenance tracking. The choice to map invariant terms to images using StyleGAN2 is a clever solution to address the risk of information leakage and to facilitate easy comparison. The image serves as a human-readable and easily verifiable fingerprint.

HuRef Framework#

The HuRef framework presents a novel approach to copyright protection for Large Language Models (LLMs) by generating a human-readable fingerprint. HuRef’s core innovation lies in its use of invariant terms derived from the LLM’s internal structure, making the fingerprint resistant to common model alterations like fine-tuning or continued pre-training. These invariant terms are then mapped to a natural image using StyleGAN2, ensuring both uniqueness and public verifiability. The integration of Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) is crucial as it guarantees the fingerprint’s authenticity without exposing sensitive model parameters. This framework uniquely addresses the challenge of LLM copyright protection in a black-box setting, offering a robust and practical solution for identifying base models while maintaining model secrecy and integrity. HuRef’s strength is its blend of robust mathematical foundations and human-interpretable outputs, enabling easy identification of model origins through image comparison. The framework’s reliance on inherent model properties, rather than external watermarks, makes it highly resilient against various attacks.

ZKP in HuRef#

The integration of Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP) within HuRef is a critical security enhancement, addressing the inherent vulnerability of revealing model parameters when verifying fingerprint authenticity. HuRef’s fingerprint, while visually representing model parameters, inherently risks leaking information if directly published. ZKP elegantly solves this by allowing verification of fingerprint integrity without exposing the underlying parameters. This maintains the black-box nature of HuRef, crucial for protecting intellectual property, while simultaneously ensuring that the published fingerprint is genuinely representative of the claimed base model. The reliance on ZKP makes HuRef robust against malicious alterations or substitution attacks, as any attempt to generate a fraudulent fingerprint would fail the verification process. In essence, ZKP acts as a trust mechanism, assuring users of the fingerprint’s authenticity without compromising the confidentiality of the model’s internal workings.

HuRef Limitations#

HuRef’s limitations primarily stem from its reliance on invariant terms derived from LLM parameter vector directions. While these terms are shown robust to various fine-tuning methods, they remain vulnerable to sophisticated attacks that rearrange weight matrices without performance degradation. The current method also lacks a thorough analysis of its performance against adversarial examples specifically designed to evade detection. Zero-Knowledge Proof (ZKP), while employed for honest fingerprint generation, adds complexity and may not fully guarantee trustworthiness against determined adversaries. Moreover, HuRef’s applicability is currently confined to transformer-based LLMs. Therefore, future work should focus on addressing robustness issues, expanding to other LLM architectures, and further strengthening security against potential attacks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

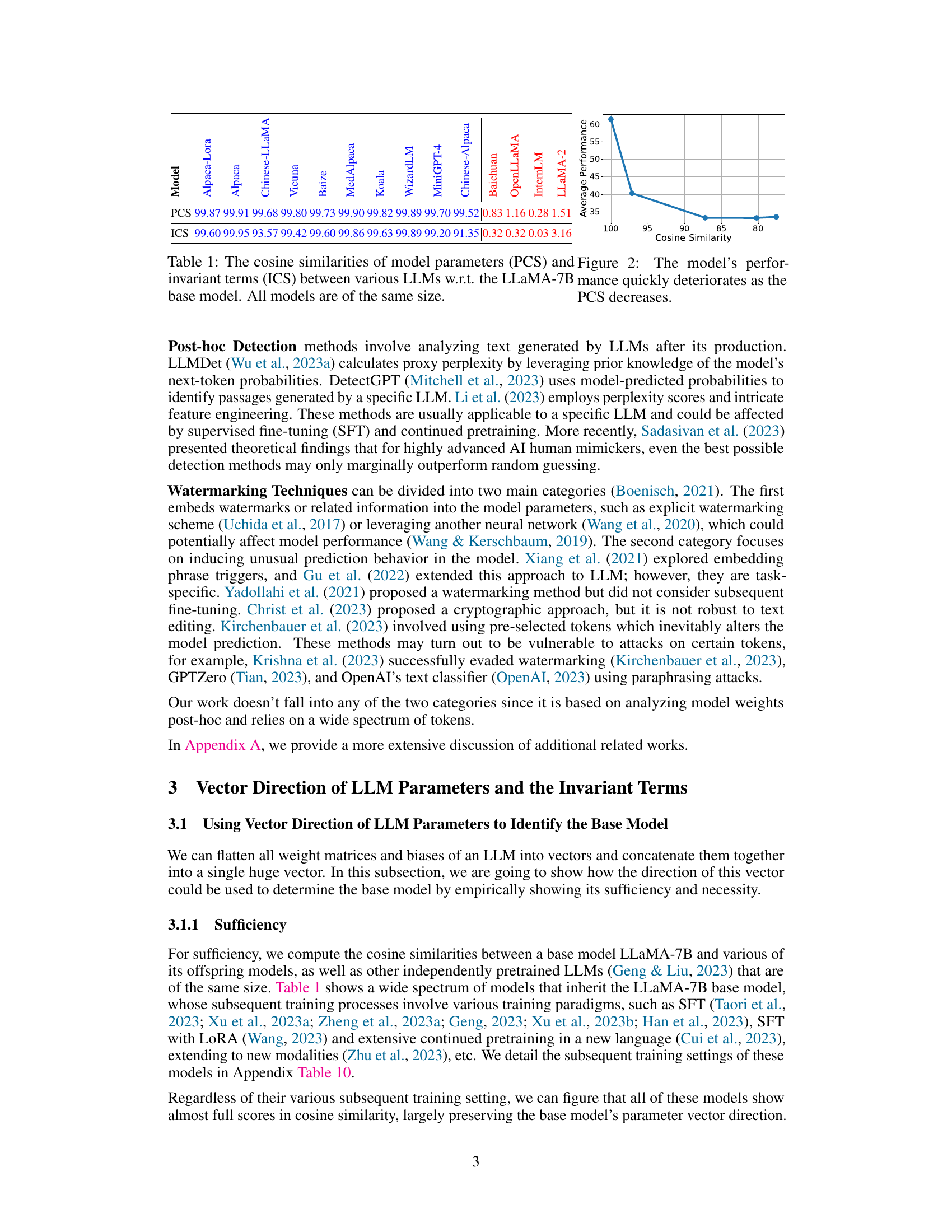

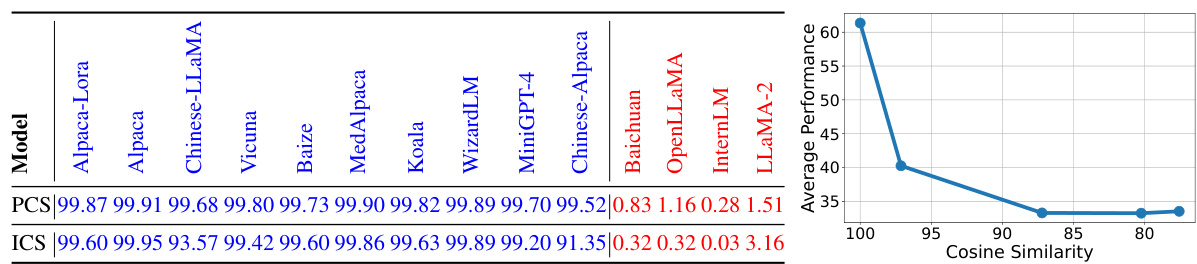

This figure shows the relationship between the cosine similarity of model parameters (PCS) and the model’s performance. As the cosine similarity decreases (meaning the model parameters’ direction deviates further from that of the base model), the model’s performance drops significantly, demonstrating the necessity of preserving the base model’s parameter vector direction to maintain performance. The performance is measured on a set of standard benchmarks.

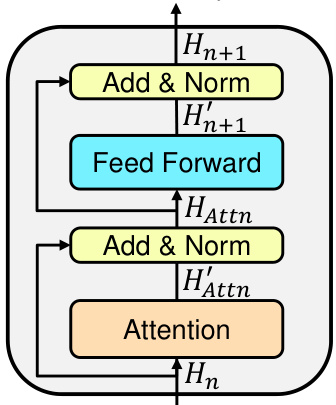

This figure shows a detailed diagram of a single Transformer layer. It illustrates the flow of information, highlighting the key components: Attention, Add & Norm, and Feed Forward. The arrows indicate the direction of data processing within the layer, starting with the input hidden state (Hn) and culminating in the output hidden state (Hn+1). The different colors represent different sub-layers or modules within the Transformer block, visually separating the attention mechanism, the feed-forward network, and the layer normalization steps. This visualization is crucial for understanding the mathematical operations described in section 3.2 of the paper, especially when analyzing potential attacks that rearrange model weights.

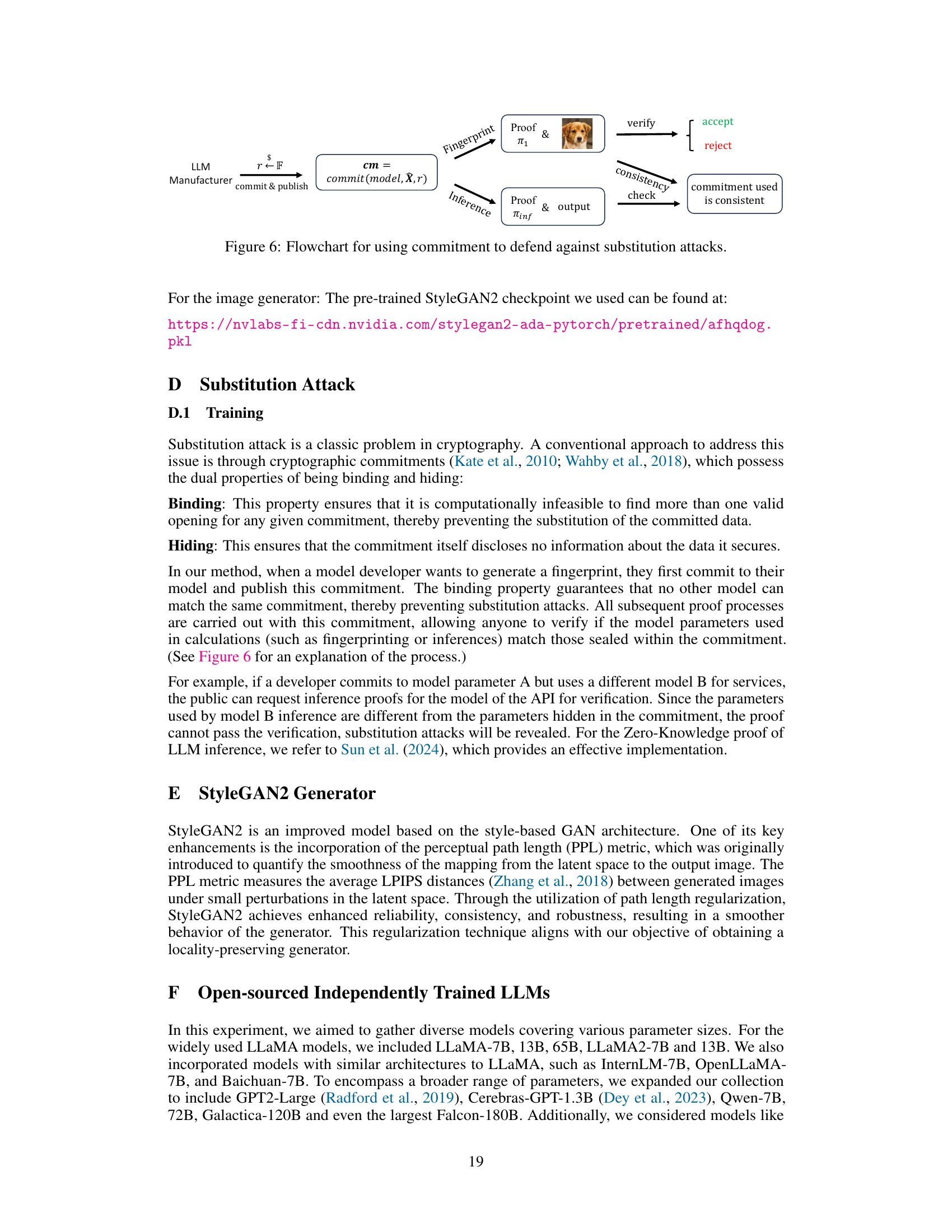

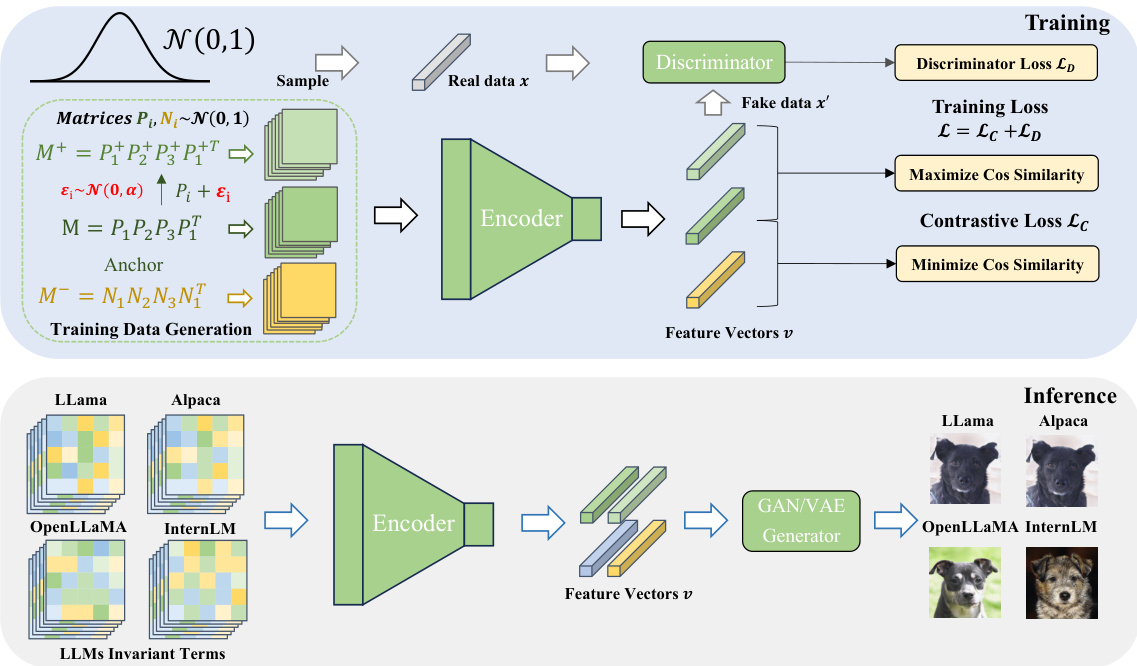

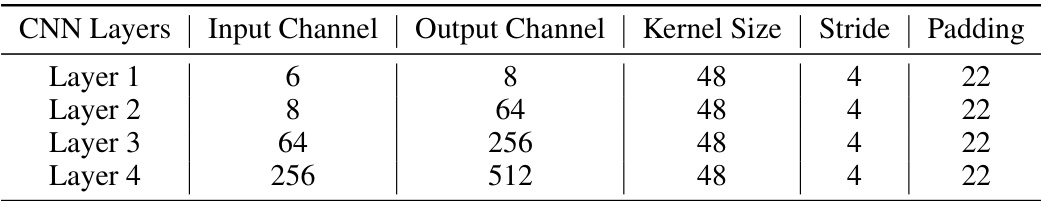

This figure illustrates the training and inference processes of the fingerprinting model. During training, the model learns a mapping between the invariant terms extracted from LLMs and their corresponding Gaussian vectors using a contrastive learning approach with a GAN for Gaussian distribution. In the inference stage, the trained encoder maps invariant terms from LLMs to Gaussian vectors, and a GAN-based image generator converts the vectors into human-readable fingerprint images.

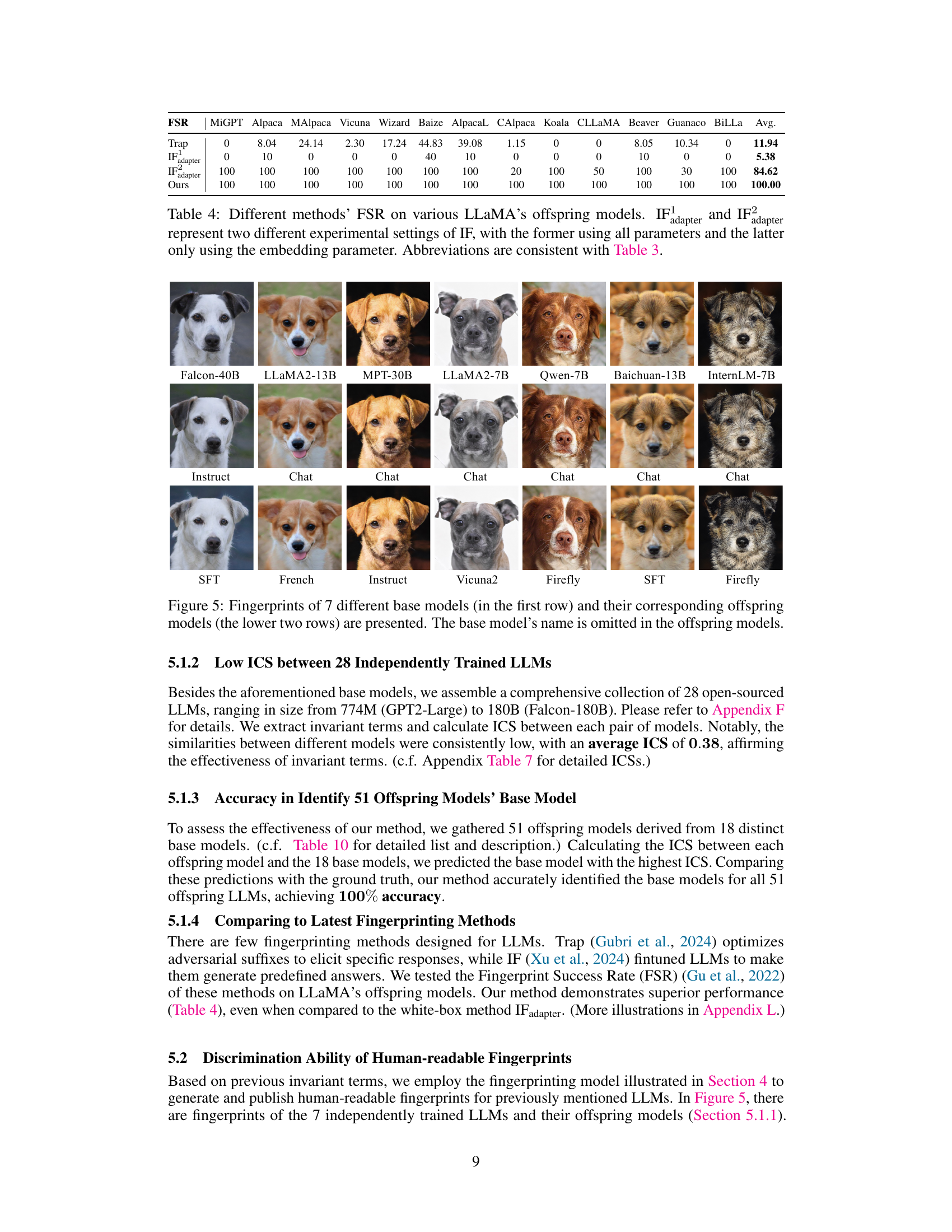

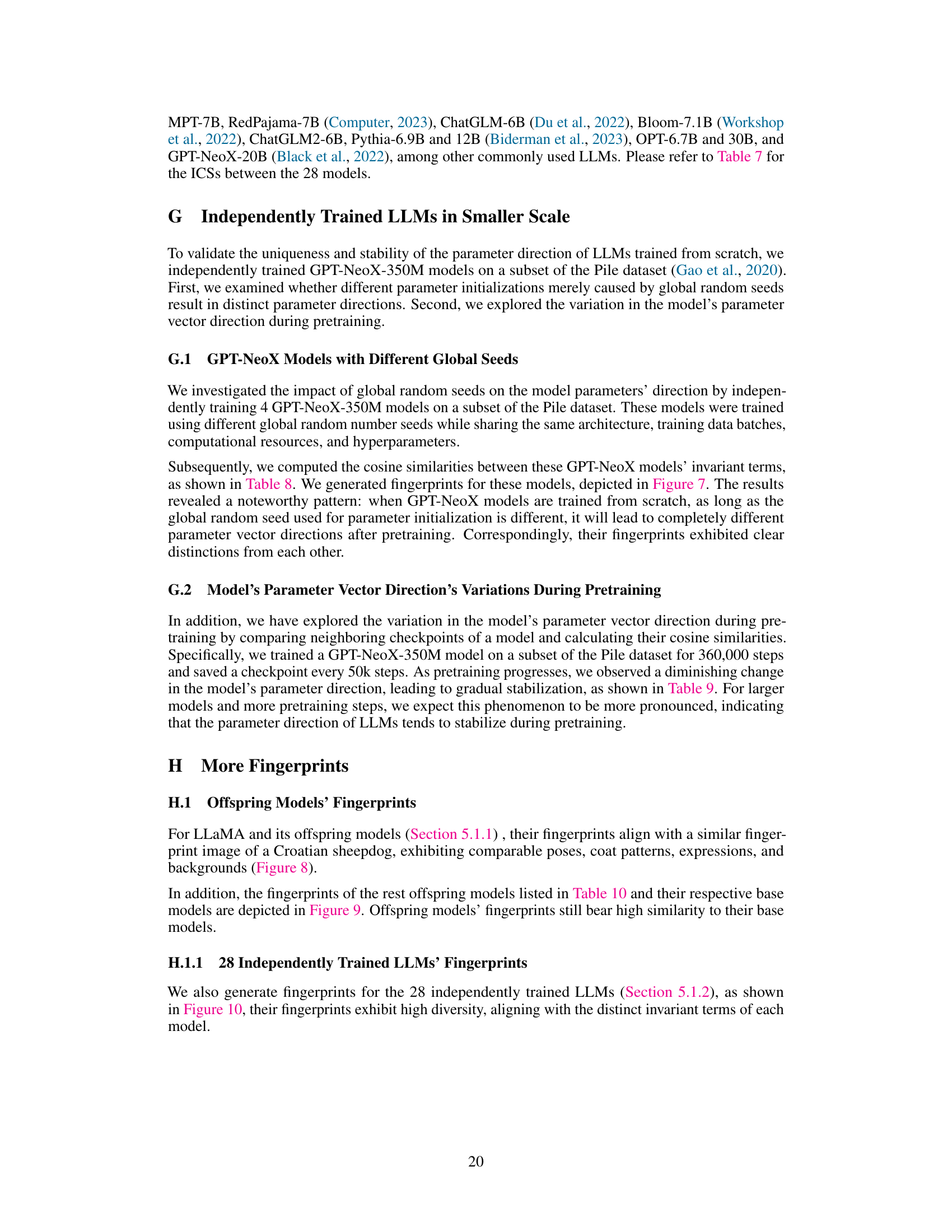

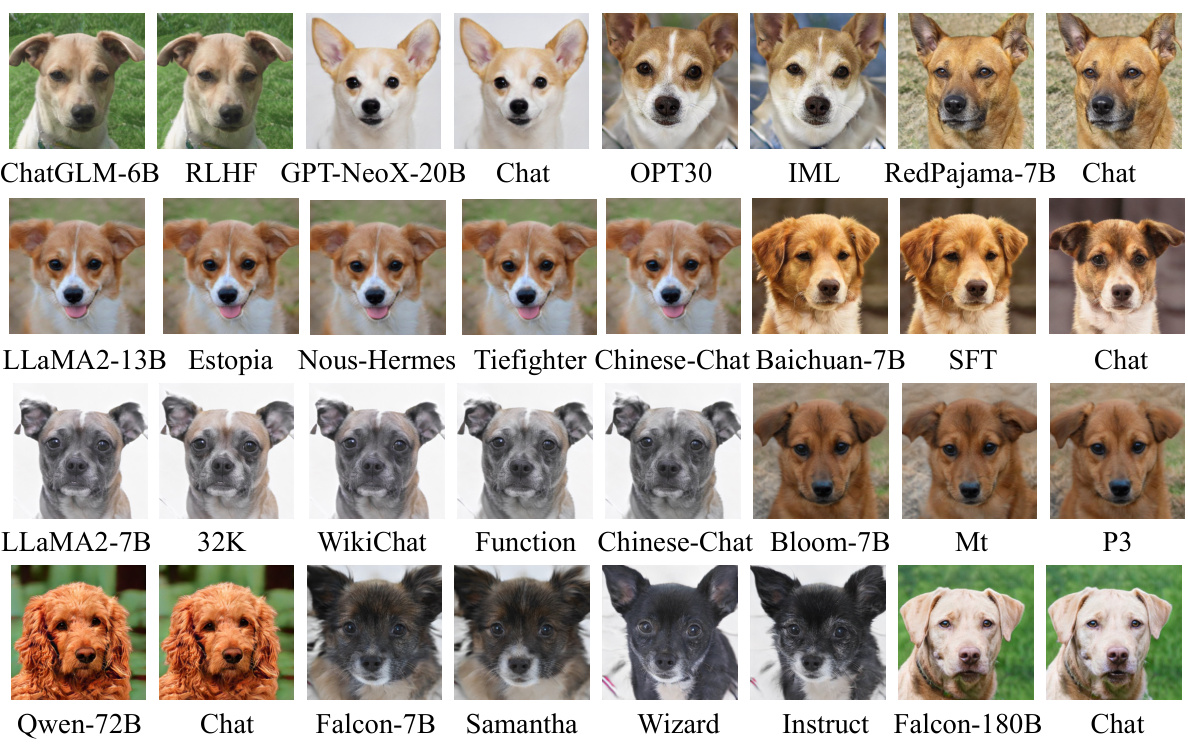

This figure shows the fingerprints generated by HuRef for seven different base LLMs and their offspring models. The top row displays the fingerprints of the base models (Falcon-40B, LLaMA2-13B, MPT-30B, LLaMA2-7B, Qwen-7B, Baichuan-13B, InternLM-7B), while the bottom two rows showcase the fingerprints of their corresponding offspring models, created through various training techniques such as Instruction fine-tuning (Instruct), supervised fine-tuning (SFT), and reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). The figure visually demonstrates HuRef’s ability to distinguish between base models and their derivatives, even after undergoing significant training modifications.

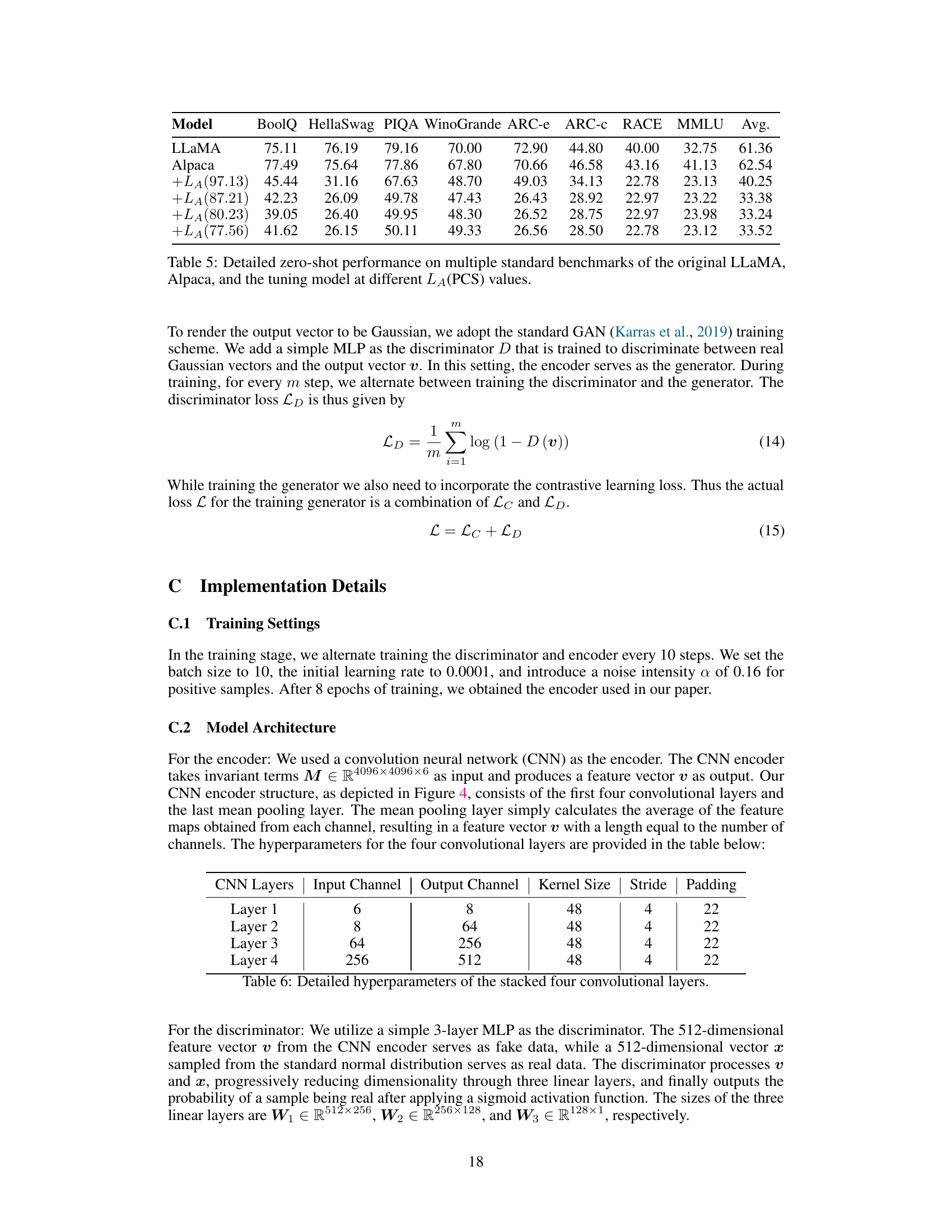

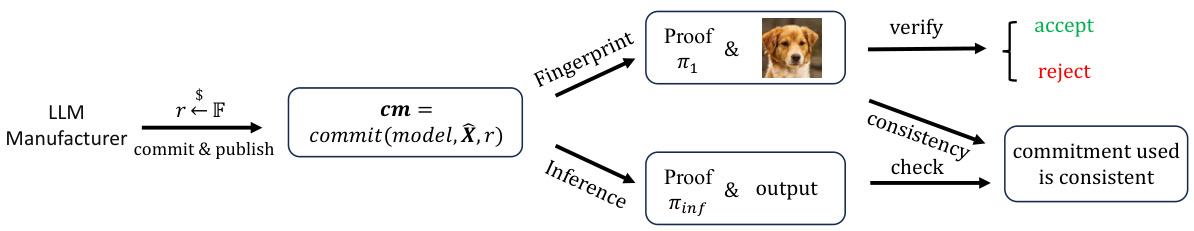

The flowchart illustrates the process of using cryptographic commitments to protect against substitution attacks in the context of LLM fingerprinting. The LLM manufacturer computes a commitment using the model’s parameters, a random value (r), and an input (X). This commitment (cm) is publicly published along with the fingerprint image. A verification process then involves checking the consistency of the commitment with the fingerprint. The process involves the generation of a zero-knowledge proof (π₁) to ensure the fingerprint was honestly generated from the claimed model and a proof (πinf) that verifies the consistency of the commitment with the output.

This figure illustrates the framework for protecting LLMs using fingerprints. LLM manufacturers compute invariant terms internally and use a fingerprinting model to create a fingerprint image. This image and zero-knowledge proofs are publicly released, enabling identification of models with shared base models. A quantitative comparison scheme is included as a complement, and the zero-knowledge proofs ensure the reliability of the fingerprints without revealing model parameters.

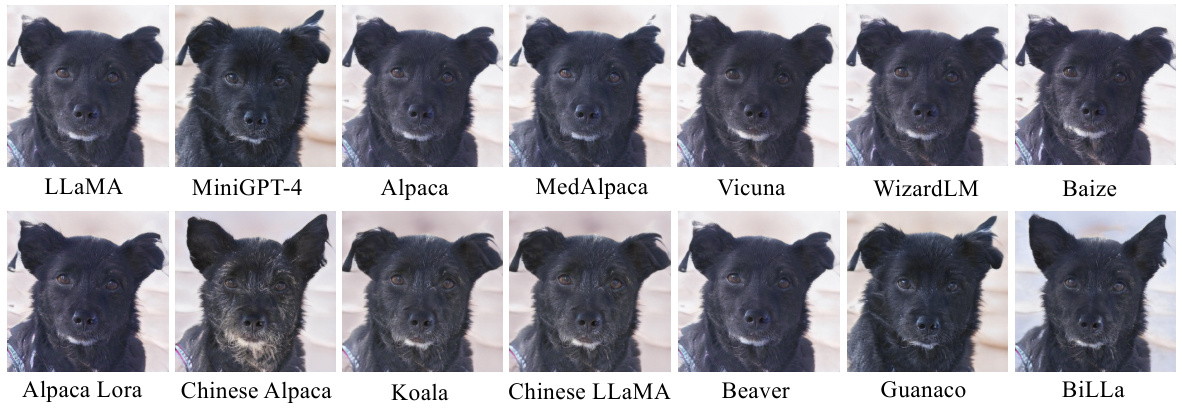

This figure visually shows the fingerprints generated by the HuRef model for LLaMA-7B and ten of its offspring models. Each fingerprint is a StyleGAN2-generated image that uniquely identifies the base model. The visual similarity between the fingerprints of the base model and its offspring models demonstrates the effectiveness of the HuRef method in preserving model identity even after fine-tuning or continued pretraining. The differences in appearance between the fingerprints of different base models highlight the unique identity assigned by HuRef.

This figure shows the fingerprints generated by the HuRef model for 7 base LLMs and their offspring models. Each fingerprint is a StyleGAN2-generated image representing the invariant terms derived from the LLM parameters. The figure demonstrates that offspring models have very similar fingerprints to their base models, while independently trained models have distinct fingerprints. The top row shows fingerprints of the base models and the two bottom rows show the fingerprints of their offspring models. Base model names are not displayed for offspring models.

This figure shows the fingerprints generated by the HuRef model for 28 independently trained LLMs. Each fingerprint is a StyleGAN2-generated image that uniquely identifies the base model of the corresponding LLM. The diversity of the fingerprints highlights the ability of HuRef to distinguish between different LLMs, even those trained independently.

This figure illustrates the process of using HuRef for LLM copyright protection. LLM manufacturers calculate invariant terms from their model’s parameters, use a fingerprinting model to generate a fingerprint image from those terms, and then publish the image along with zero-knowledge proofs. This allows others to verify that different LLMs share the same base model by comparing their fingerprint images. A quantitative comparison scheme is also included as a secondary verification method.

This figure shows a sample question from a human subject study designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method for identifying base LLMs from their offspring models using generated fingerprints. Participants were given an offspring model’s fingerprint (OPT-IML-30B in this example) and asked to choose the most similar fingerprint from a selection of 18 base model fingerprints. Correct identification required an exact match to the base model of the offspring model (OPT-30B).

More on tables

This table presents the cosine similarity scores of model parameters (PCS) and invariant terms (ICS) between various LLMs with respect to the LLaMA-7B base model. It demonstrates the high cosine similarity between models that share a common base model, regardless of subsequent training steps, and the sharp decrease in performance when the parameter vector direction deviates from that of the base model.

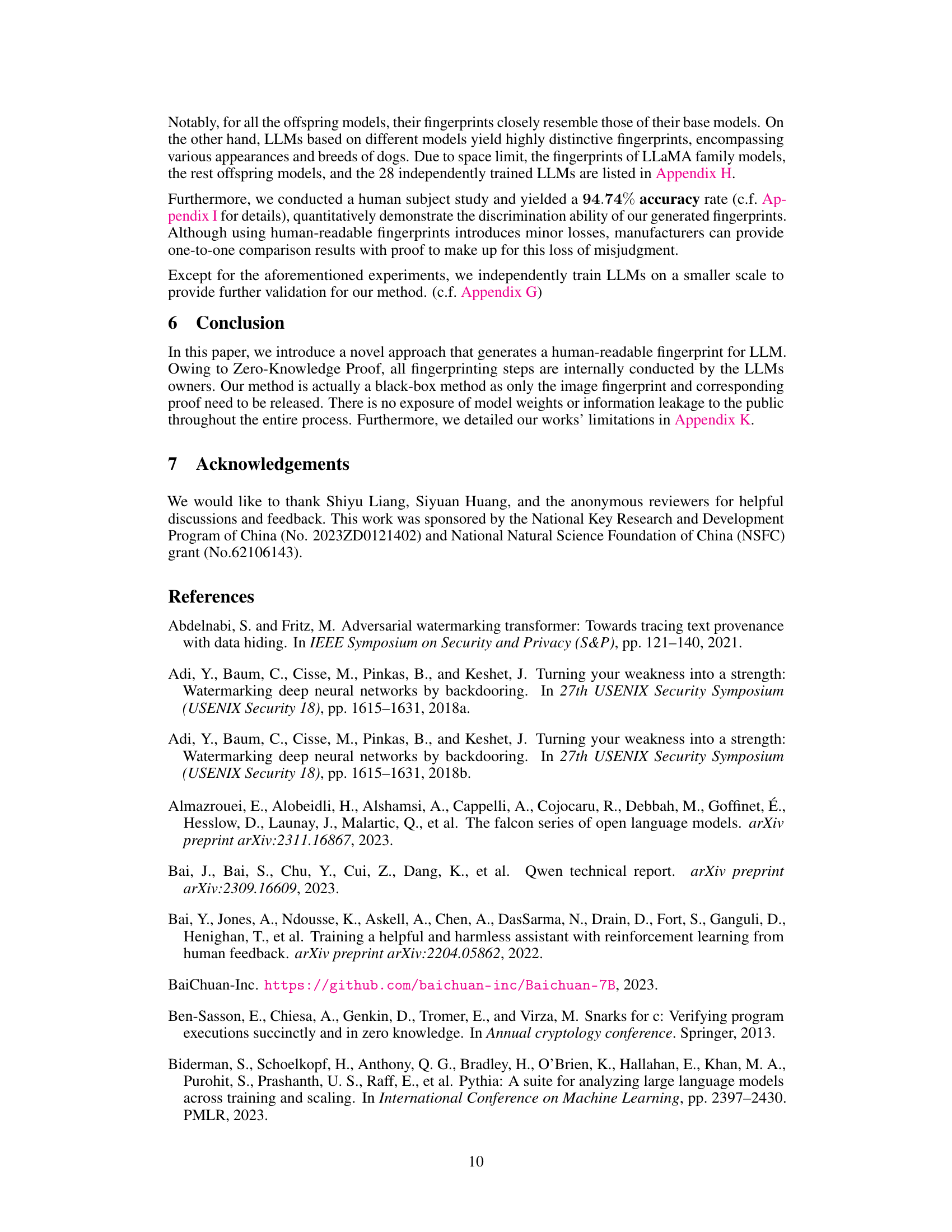

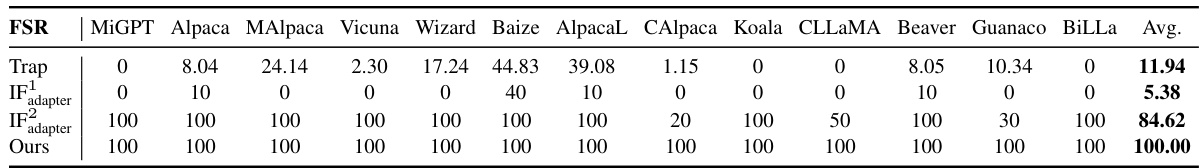

This table compares the Fingerprint Success Rate (FSR) of different methods for identifying the base model of LLaMA offspring models. The methods compared include Trap, IF (with two variations: IF1 using all parameters and IF2 using only embedding parameters), and the proposed HuRef method. The table shows that HuRef achieves a perfect FSR of 100%, significantly outperforming Trap and IF.

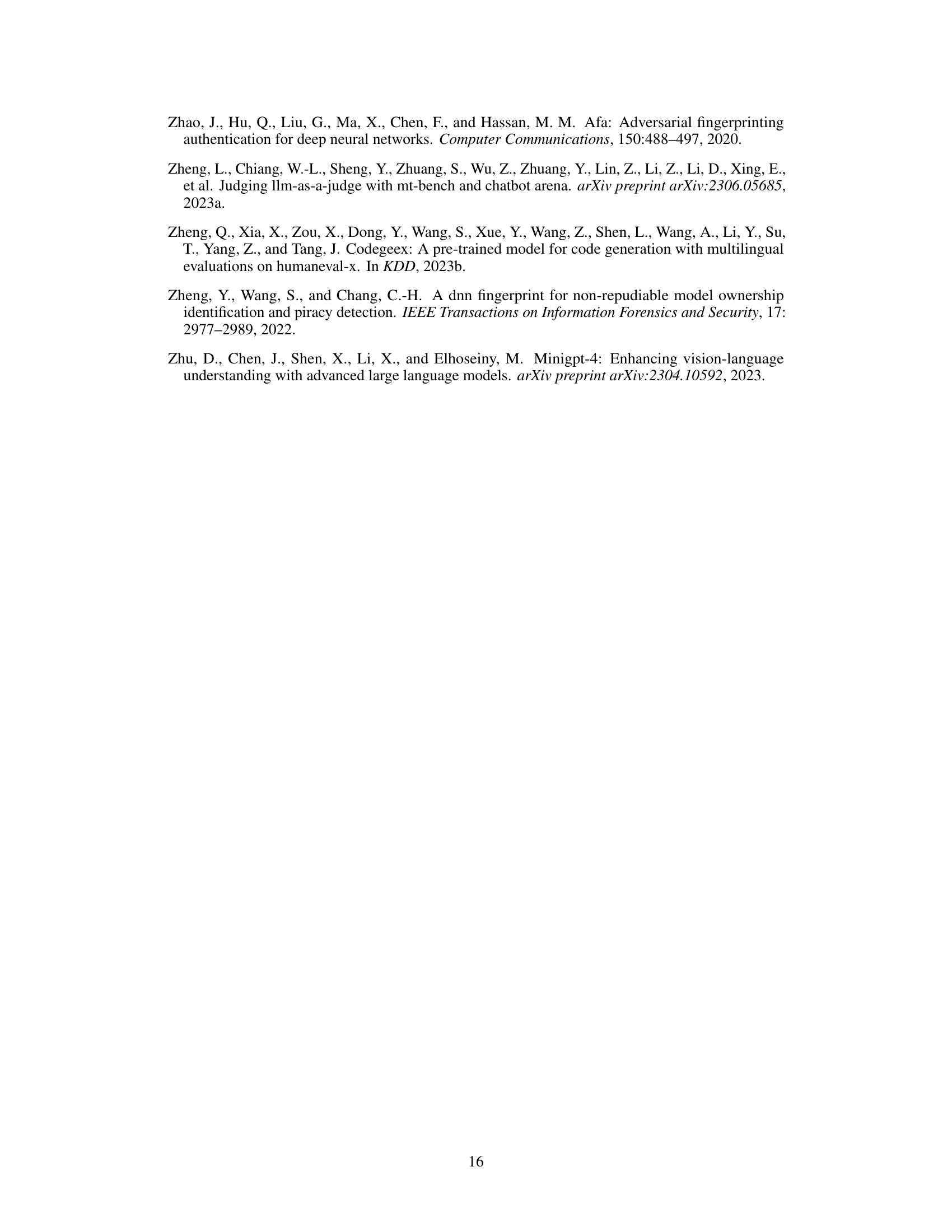

This table presents the results of a zero-shot experiment conducted on several standard benchmarks using three different models: the original LLaMA model, the Alpaca model, and a fine-tuned model. The Alpaca model is a fine-tuned version of the LLaMA model. The fine-tuned model was trained with an additional term (LA) in the loss function which minimized the cosine similarity to the original LLaMA model’s parameters. The cosine similarity acts as an indicator of how close the model parameters are to those of the base model. The table shows the performance of each model on various tasks, indicating how changes to the model’s parameter direction due to fine-tuning affect its overall performance.

This table displays the cosine similarity of model parameters (PCS) and invariant terms (ICS) between various LLMs and the LLaMA-7B base model. The PCS measures the similarity of the raw model parameters, while the ICS reflects the similarity of the derived invariant terms, which are more robust to attacks. The table demonstrates that the PCS values are very high for models that are derived from LLaMA-7B, while the ICS is much lower for independently-trained models. The accompanying figure shows the relationship between model performance and PCS, revealing a sharp decline in performance when PCS decreases. This suggests the importance of the invariant terms in identifying the base model.

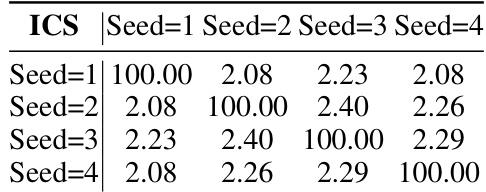

This table presents the cosine similarities (ICS) of invariant terms between four GPT-NeoX-350M models. Each model was trained independently from scratch using different global random seeds, while sharing the same architecture, training data, computational resources, and hyperparameters. The high diagonal values (close to 100) represent the high similarity of a model’s invariant terms to itself. The low off-diagonal values (close to 2) indicate the low similarity between models trained with different seeds. This demonstrates that even subtle differences in initial conditions lead to distinct parameter vector directions after pretraining.

This table shows the cosine similarity of model parameters (PCS) and invariant terms (ICS) between various LLMs with respect to the LLaMA-7B base model. The PCS values show how similar the overall parameter vectors are between different models. A high PCS suggests that two LLMs might share a common base model. The ICS values indicate the similarity of invariant terms extracted from the models, which are robust to attacks that rearrange model weights. Figure 2 visually shows the correlation between the model’s performance and PCS. As the PCS decreases, the performance quickly deteriorates, showcasing the importance of the parameter vector direction in identifying the base model.

This table displays the cosine similarity scores of model parameters (PCS) and invariant terms (ICS) for various LLMs compared to the LLaMA-7B base model. It shows that LLMs derived from LLaMA-7B exhibit high cosine similarity scores, indicating preservation of the base model’s parameter vector direction, even after substantial fine-tuning or continued pretraining. The figure demonstrates the correlation between PCS and model performance, showing that performance drops significantly when the parameter vector direction differs substantially from the base model.

Full paper#