↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many optimization algorithms require careful tuning of step sizes based on problem-specific constants which are often unknown in practice. This leads to suboptimal performance or inefficient algorithms. Adaptive methods address this by automatically adjusting step sizes, but theoretical guarantees are often limited to specific problem classes. This paper tackles this challenge by developing a class of adaptive gradient methods.

The paper introduces UniSgd and UniFastSgd algorithms that use AdaGrad stepsizes. These algorithms are shown to achieve optimal convergence rates under various assumptions on the smoothness of the problem and the variance of stochastic gradients. The authors demonstrate three key results: (1) The methods work well with uniformly bounded variance. (2) Implicit variance reduction occurs under refined variance assumptions. (3) Explicit variance reduction using SVRG techniques significantly speeds up the algorithms. Both basic and accelerated versions of the methods are analyzed, showcasing impressive improvements over existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents universally applicable stochastic gradient methods that achieve state-of-the-art convergence rates without requiring knowledge of problem-dependent constants. This addresses a major limitation of existing adaptive methods and opens avenues for further research in optimizing various problem classes (smooth, nonsmooth, Hölder smooth), particularly in machine learning where such constants are often unknown or difficult to estimate. The findings are significant for researchers working on diverse optimization problems and have the potential to improve the efficiency and practicality of many existing algorithms.

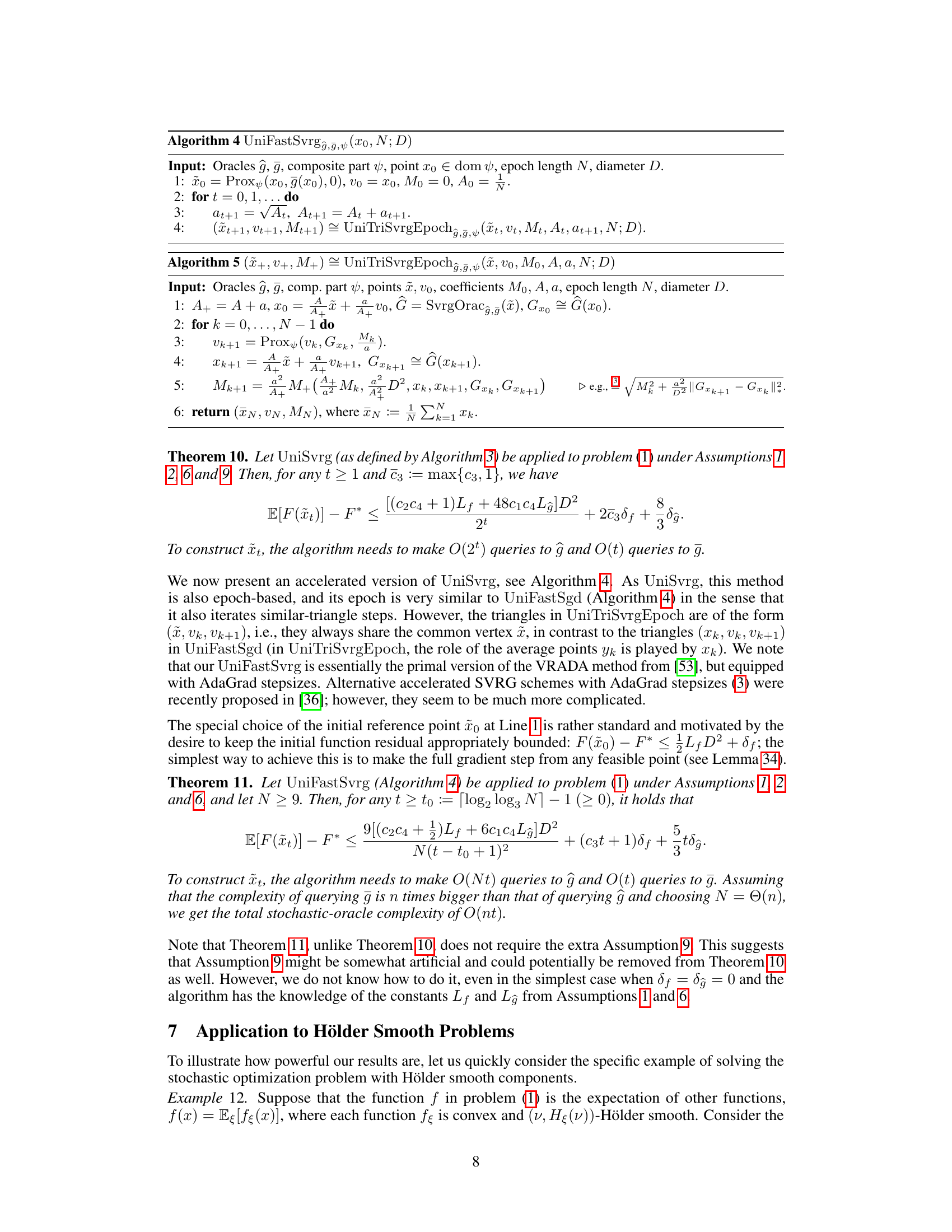

Visual Insights#

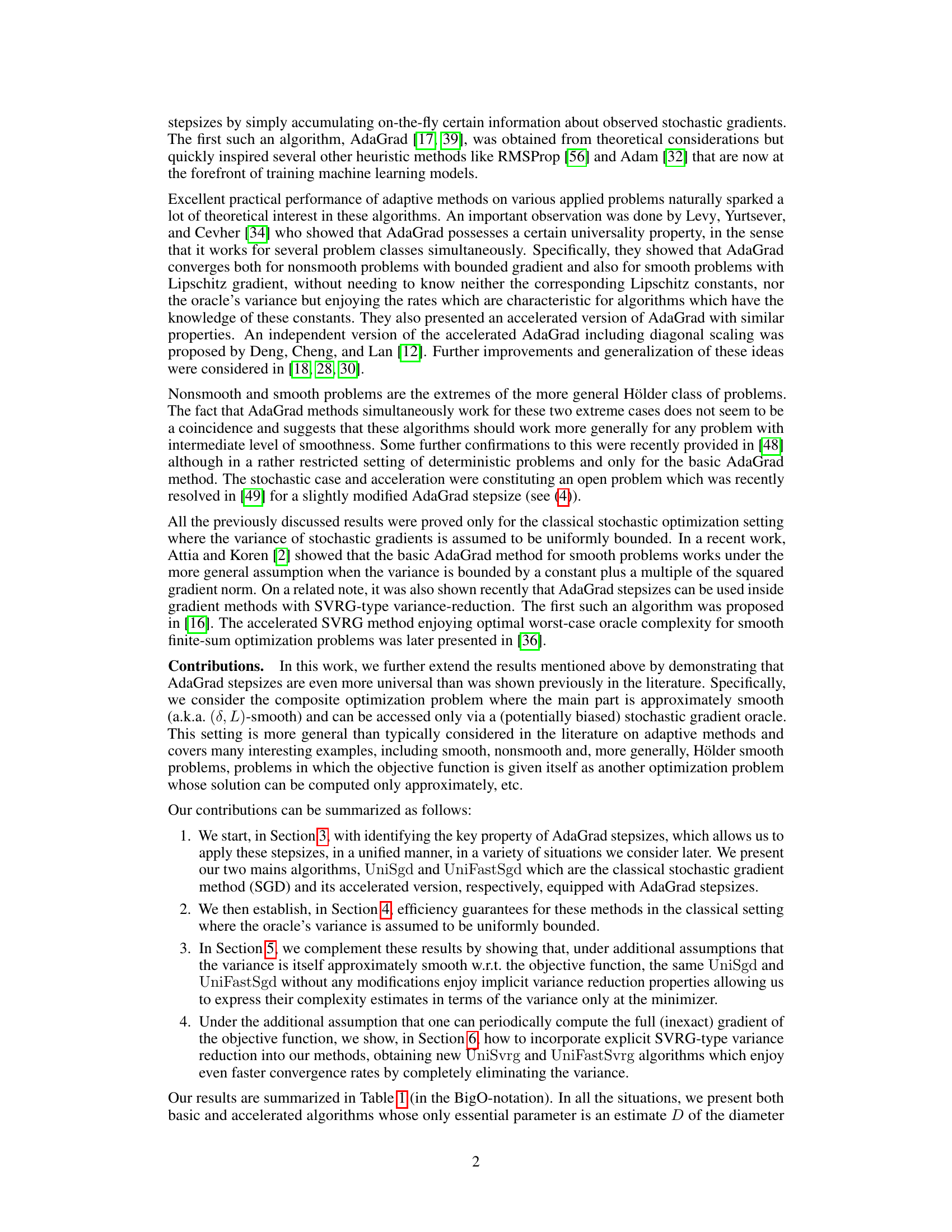

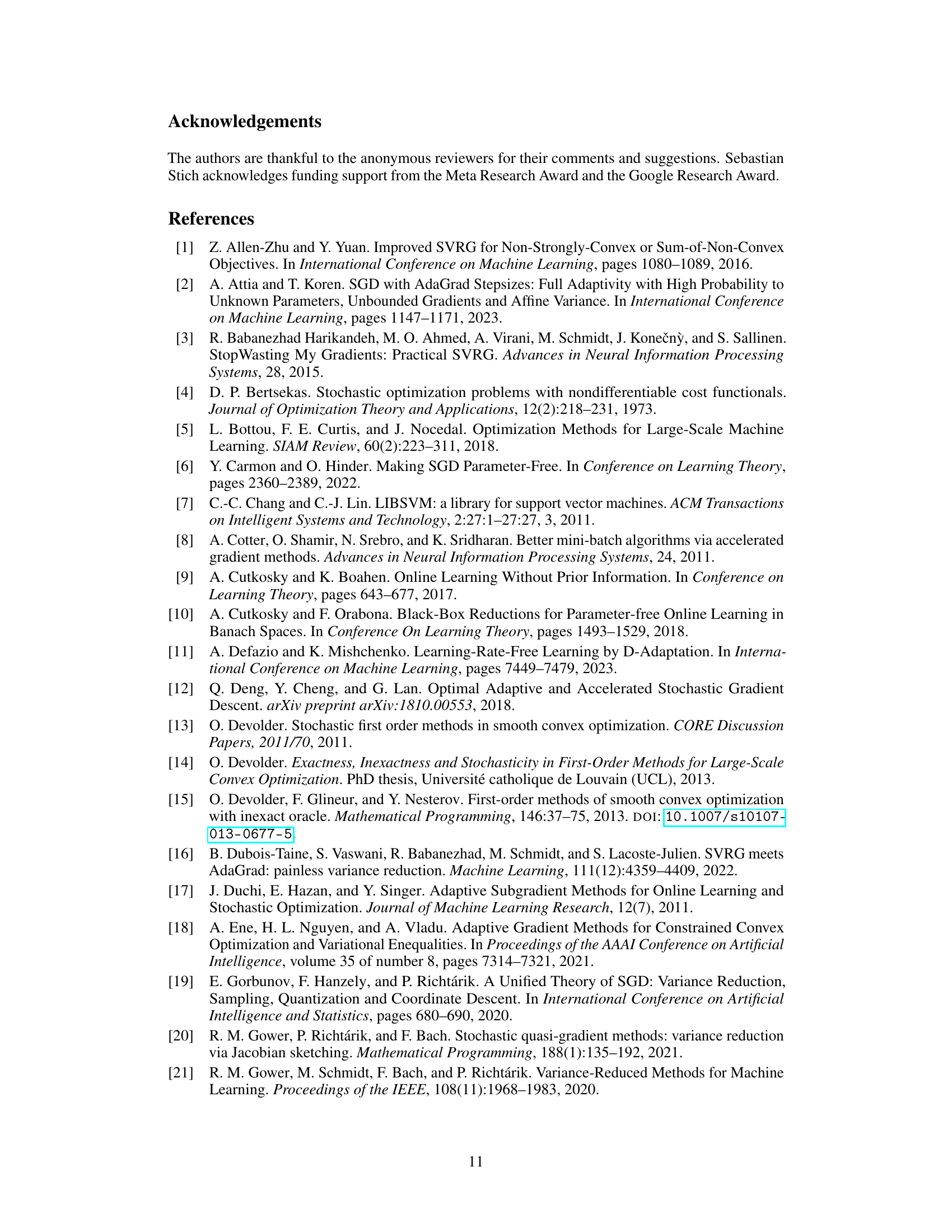

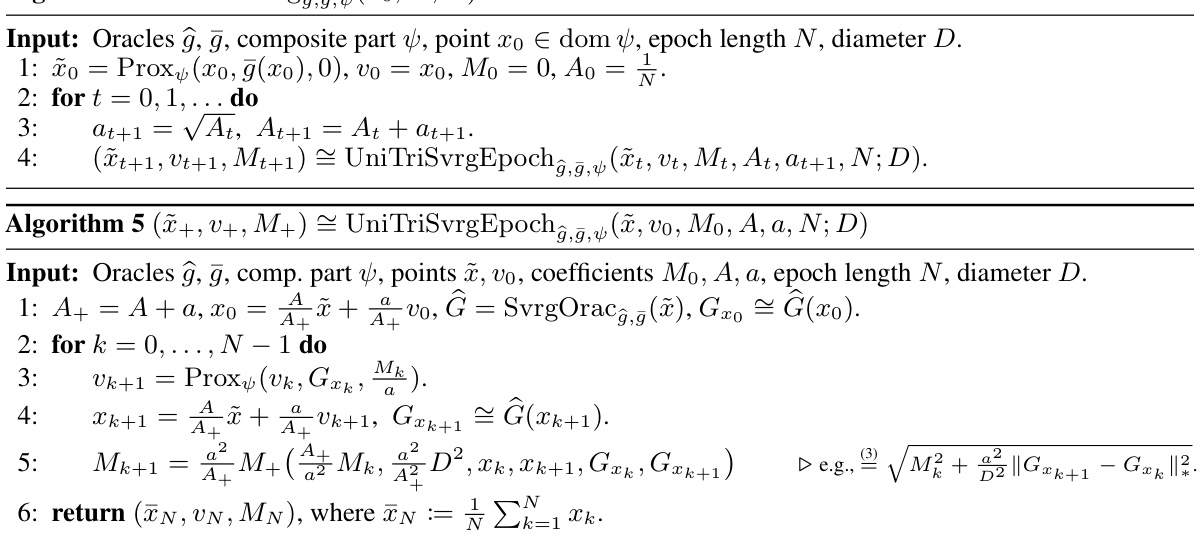

This figure compares the performance of several optimization algorithms on a polyhedron feasibility problem. The algorithms include UniSgd, UniFastSgd, AdaSVRG, UniSvrg, AdaVRAG, AdaVRAE, and FastSVRG. The x-axis represents the number of stochastic oracle calls, and the y-axis represents the function residual. The graph shows how quickly each algorithm converges to a solution, with different lines representing different algorithms and different colors representing different values of q (the Hölder smoothness parameter).

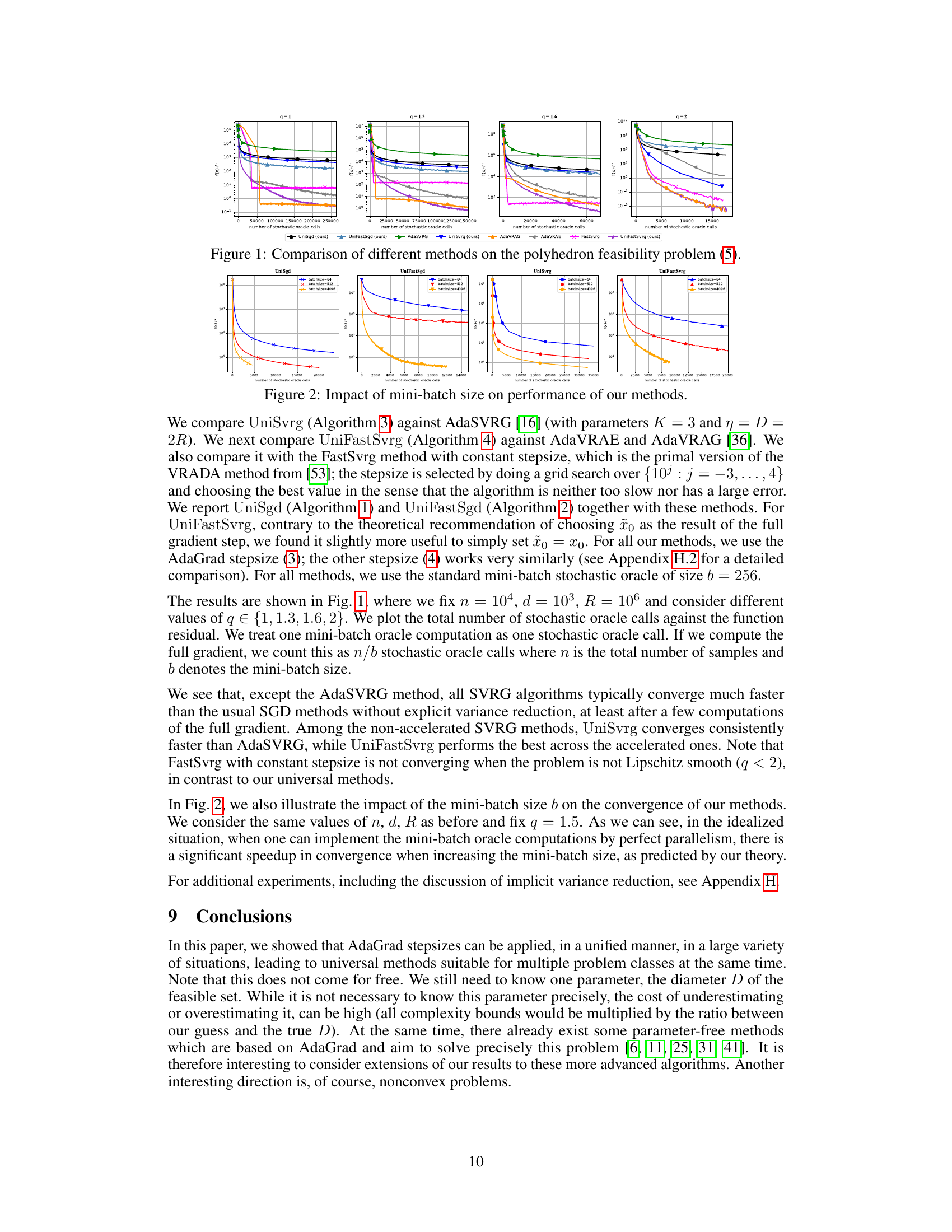

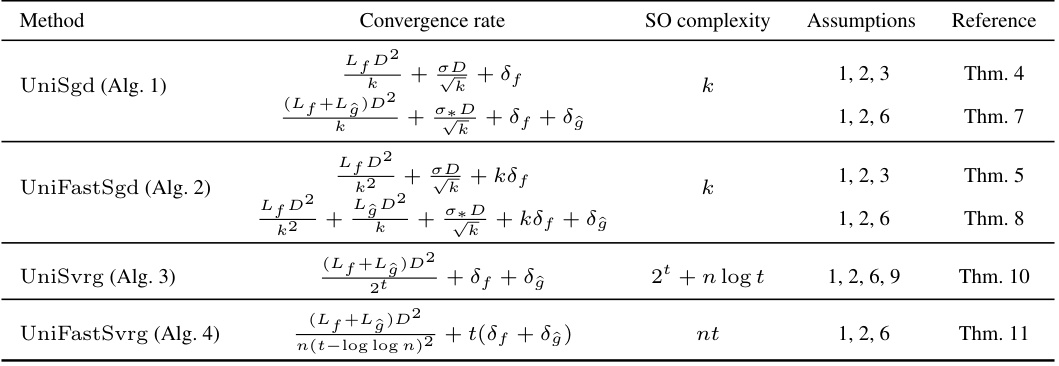

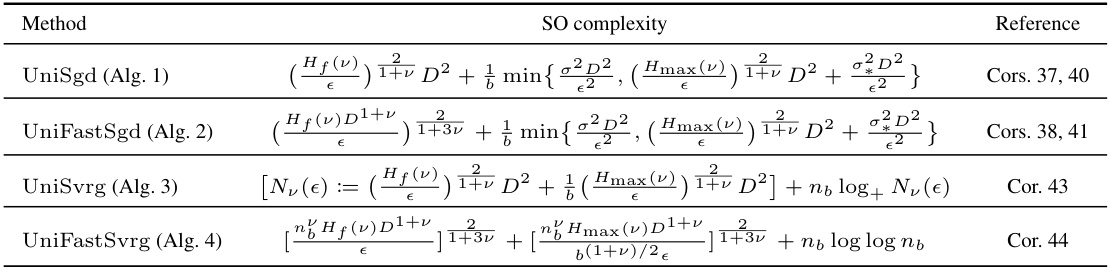

This table summarizes the main results of the paper, presenting the convergence rate and stochastic oracle complexity for four different algorithms: UniSgd, UniFastSgd, UniSvrg, and UniFastSvrg. These algorithms are variations of stochastic gradient descent methods that use AdaGrad stepsizes. The table shows how the performance of these algorithms varies depending on different assumptions about the problem and the stochastic oracle. The assumptions relate to the smoothness of the objective function and the variance of the stochastic gradient. The convergence rates are expressed in terms of the expected function residual, while the stochastic oracle complexity measures the total number of queries to the stochastic gradient oracle.

In-depth insights#

AdaGrad’s Universality#

AdaGrad’s universality lies in its ability to achieve optimal convergence rates across diverse convex optimization problems without requiring prior knowledge of problem-specific parameters. Adaptive stepsizes, central to AdaGrad, automatically adjust to the problem’s inherent smoothness and noise characteristics, eliminating the need for manual tuning. This adaptability extends to scenarios with inexact oracles and non-uniform variance, showcasing its robustness. The key property enabling this universality is an inequality relating the algorithm’s progress, stepsize updates, and variance, implying that even with noisy gradient estimates, AdaGrad’s inherent mechanisms guarantee convergence at optimal rates. Implicit variance reduction emerges as a result of this adaptability, further contributing to its efficiency and widespread applicability. The algorithm’s dependence solely on an estimate of the feasible set’s diameter makes it exceptionally practical and universally applicable in various contexts.

Variance Reduction#

The concept of variance reduction is central to optimizing stochastic gradient descent (SGD) methods. High variance in gradient estimations slows convergence. Variance reduction techniques aim to reduce this variance, leading to faster convergence rates. This is achieved by incorporating information from full gradients or cleverly designed sampling strategies. The paper explores both implicit and explicit variance reduction. Implicit methods leverage refined assumptions on the stochastic oracle’s variance to demonstrate faster convergence without algorithmic modification. Explicit methods, like SVRG, directly incorporate full gradient estimations into the update rule, significantly reducing variance. The paper’s analysis of both approaches provides a comprehensive understanding of how variance impacts the efficiency of SGD and highlights the effectiveness of AdaGrad stepsizes even in scenarios where variance isn’t uniformly bounded.

Adaptive Methods#

Adaptive methods in optimization are crucial for handling problems with unknown or varying characteristics. Unlike traditional methods requiring predefined parameters, adaptive techniques adjust their behavior during the optimization process. This is particularly valuable in situations with noisy or uncertain data, as seen in machine learning where data distributions and model complexities are often unpredictable. AdaGrad, a prominent adaptive method, demonstrates the power of adjusting step sizes dynamically based on accumulated gradient information. This inherent adaptability enables efficient learning even in the absence of precise problem-specific constants, leading to improved robustness and better convergence rates. However, adaptive methods can be sensitive to noise and require careful consideration of their specific properties. Therefore, theoretical analysis and performance evaluation are essential to ensure reliable application and avoid potential issues.

Algorithm Analysis#

A rigorous algorithm analysis is crucial for validating the effectiveness and efficiency of any proposed method. It involves a multifaceted approach, starting with clearly defined assumptions about the problem domain (e.g., convexity, smoothness, noise characteristics). The analysis then proceeds to establish theoretical guarantees, often expressed as convergence rates or complexity bounds, that quantify the algorithm’s performance. Key metrics include the number of iterations required to achieve a given level of accuracy, computational complexity per iteration (measured by oracle calls or operations), and memory usage. A robust analysis should consider various scenarios such as different levels of smoothness or noise, and ideally provide insights into the algorithm’s behavior in practical settings. Proofs are indispensable for establishing the validity of theoretical guarantees. The analysis should also assess the algorithm’s dependence on problem-specific parameters and ideally demonstrate its adaptability to diverse settings. Finally, the analysis should address potential limitations and discuss aspects like the practicality of the algorithm, its scalability, and the ease of implementation. A comprehensive algorithm analysis is essential for understanding its strengths and weaknesses and for evaluating its potential compared to existing methods.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to non-convex settings is crucial, as many real-world machine learning problems fall into this category. Investigating the impact of different variance reduction techniques, beyond the SVRG-type explored here, on the convergence and efficiency of AdaGrad-based methods would be highly valuable. A deeper investigation into the practical implications of the implicit variance reduction property observed is warranted, including a comprehensive empirical analysis across various datasets and problem types. Finally, developing more sophisticated step-size adaptation mechanisms that could dynamically adjust to problem characteristics without relying on estimations, could lead to even more robust and versatile optimization algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

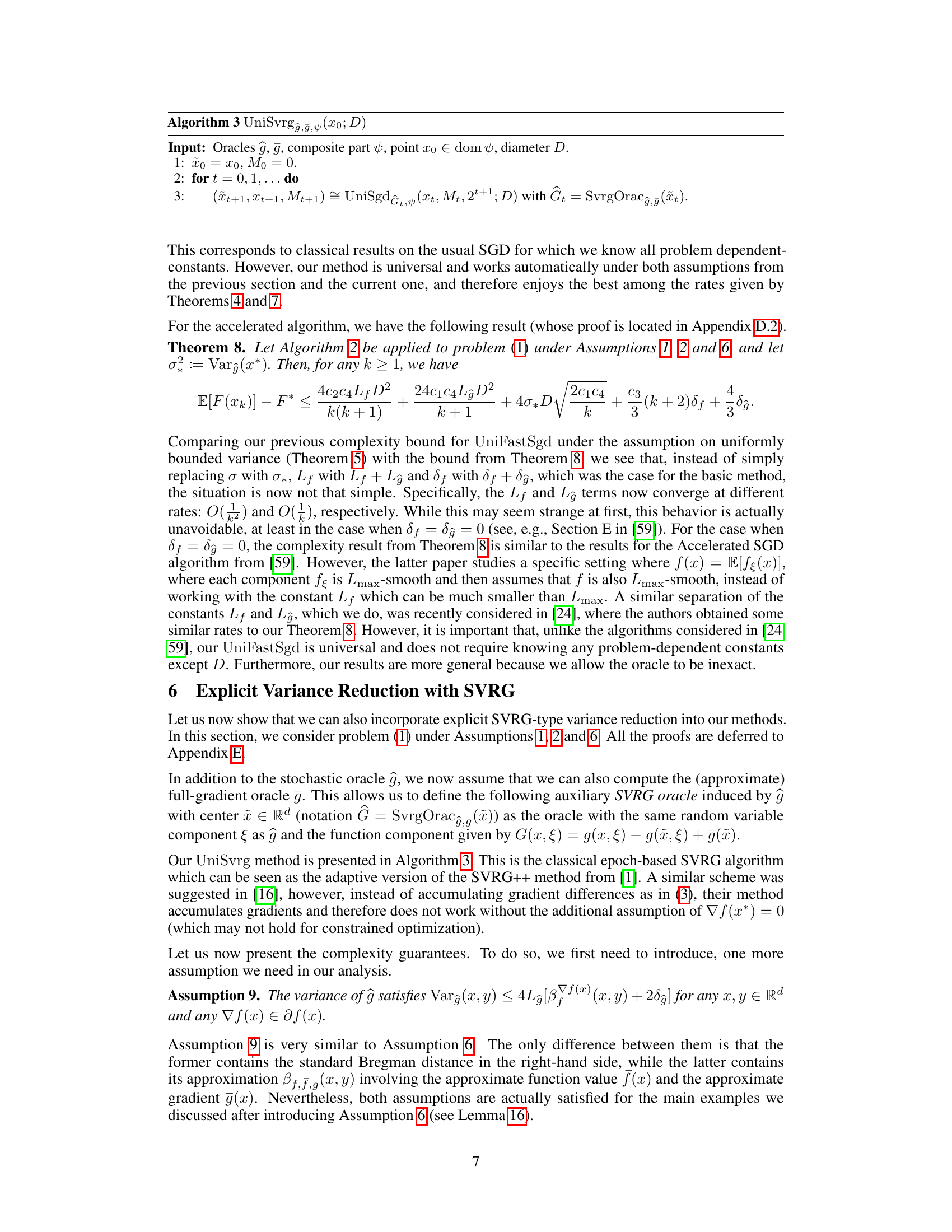

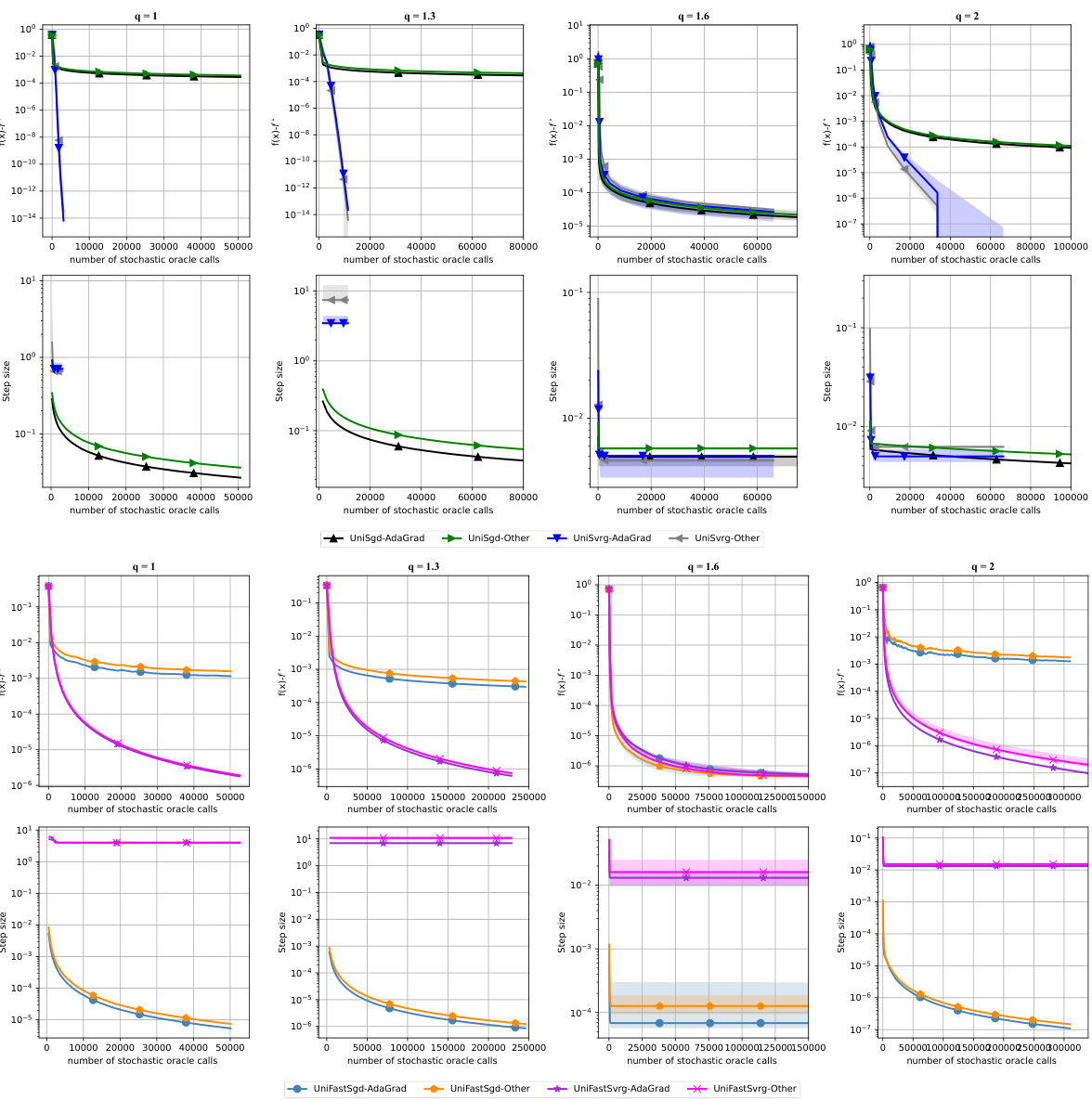

The figure shows how the performance of four different algorithms (UniSgd, UniFastSgd, UniSvrg, and UniFastSvrg) varies with different mini-batch sizes (64, 512, and 4096) when applied to the polyhedron feasibility problem. Each algorithm is represented by three lines corresponding to the three mini-batch sizes. The y-axis is the function residual and the x-axis is the number of stochastic oracle calls.

This figure compares the performance of various optimization algorithms on the polyhedron feasibility problem (5), which involves finding a point within a polyhedron while satisfying a constraint. The algorithms are UniSgd, UniFastSgd (both introduced in the paper), AdaSVRG, UniSvrg, AdaVRAG, AdaVRAE, and FastSvrg. The x-axis represents the number of stochastic oracle calls, and the y-axis represents the function residual (f(x) - f*). The plots show how quickly each algorithm reduces the function residual. Different line colors and styles correspond to different algorithms, allowing a clear visual comparison of their convergence rates.

This figure compares the performance of four different methods (UniSgd, UniSvrg, UniFastSgd, UniFastSvrg) using two different stepsize update rules (AdaGrad and another rule). The performance is evaluated on the polyhedron feasibility problem for various values of the parameter q (1.0, 1.3, 1.6, 2.0), which affects the smoothness of the problem. The plots show the function residual and the step size (inverse of M) against the number of stochastic oracle calls. The results demonstrate that the two stepsize update rules perform very similarly for all methods and problems.

This figure compares the performance of four different methods (UniSgd, UniFastSgd, UniSvrg, UniFastSvrg) using two different stepsize update rules (AdaGrad and another rule) on the polyhedron feasibility problem. The plot shows how the function residual (f(x) - f*) decreases over the number of stochastic oracle calls for different values of q (1, 1.3, 1.6, 2), representing different smoothness levels. It also plots the step size (1/M) over the same x-axis for each scenario. The figure aims to demonstrate the impact of stepsize rules on the overall performance and convergence rates.

More on tables

This table summarizes the convergence rates and stochastic oracle complexities for four algorithms: UniSgd, UniFastSgd, UniSvrg, and UniFastSvrg. The convergence rate is expressed in terms of the expected function residual, and the stochastic oracle complexity represents the number of queries to the stochastic gradient oracle. Assumptions made for each algorithm are also listed. The algorithms are variations on stochastic gradient descent, employing AdaGrad stepsizes and incorporating variance reduction techniques where appropriate.

This table summarizes the convergence rates and stochastic oracle complexities of four algorithms: UniSgd, UniFastSgd, UniSvrg, and UniFastSvrg. These algorithms are all variants of stochastic gradient descent methods, each with different properties (basic vs accelerated, and with or without variance reduction). The table shows how their convergence rates and computational costs scale with the number of iterations (k or t), problem parameters, and variance of stochastic gradients. The ‘SO complexity’ column indicates the number of stochastic gradient evaluations required by each algorithm.

This table summarizes the convergence rates and stochastic oracle complexities of four algorithms proposed in the paper for solving a composite optimization problem. The algorithms are UniSgd, UniFastSgd (accelerated version of UniSgd), UniSvrg (incorporating SVRG variance reduction), and UniFastSvrg (accelerated version of UniSvrg). The table shows the convergence rate (in terms of expected function residual), the stochastic oracle complexity (number of queries to the stochastic oracle), and the assumptions under which each algorithm achieves its reported complexity.

Full paper#