↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Transformer models struggle with long sequences, limiting their performance in many applications. Existing positional encoding methods are fixed and fail to adapt dynamically to varying input lengths, hindering performance on long sequences.

The paper introduces Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE), a novel method that dynamically adjusts positional encoding based on both input context and learned priors. DAPE significantly improves model performance on long sequences and enables better length generalization compared to traditional methods. Experiments on real-world datasets demonstrate statistically significant improvements in performance. The visualization of DAPE shows that it learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, highlighting its effectiveness in capturing relationships between tokens in long sequences.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical limitation of transformer models: their inability to effectively handle long sequences. The proposed data-adaptive positional encoding (DAPE) method significantly improves model performance on long sequences, which is crucial for many real-world applications involving long documents or complex reasoning tasks. Researchers working on transformer models and long-sequence processing will find this paper highly relevant, as it introduces a novel and effective approach to overcome a major challenge in the field. DAPE’s demonstrated advantages in length generalization and overall performance offer significant potential for improving various NLP tasks involving long input contexts. The findings also open up new research avenues to explore adaptive positional encoding techniques in transformer models.

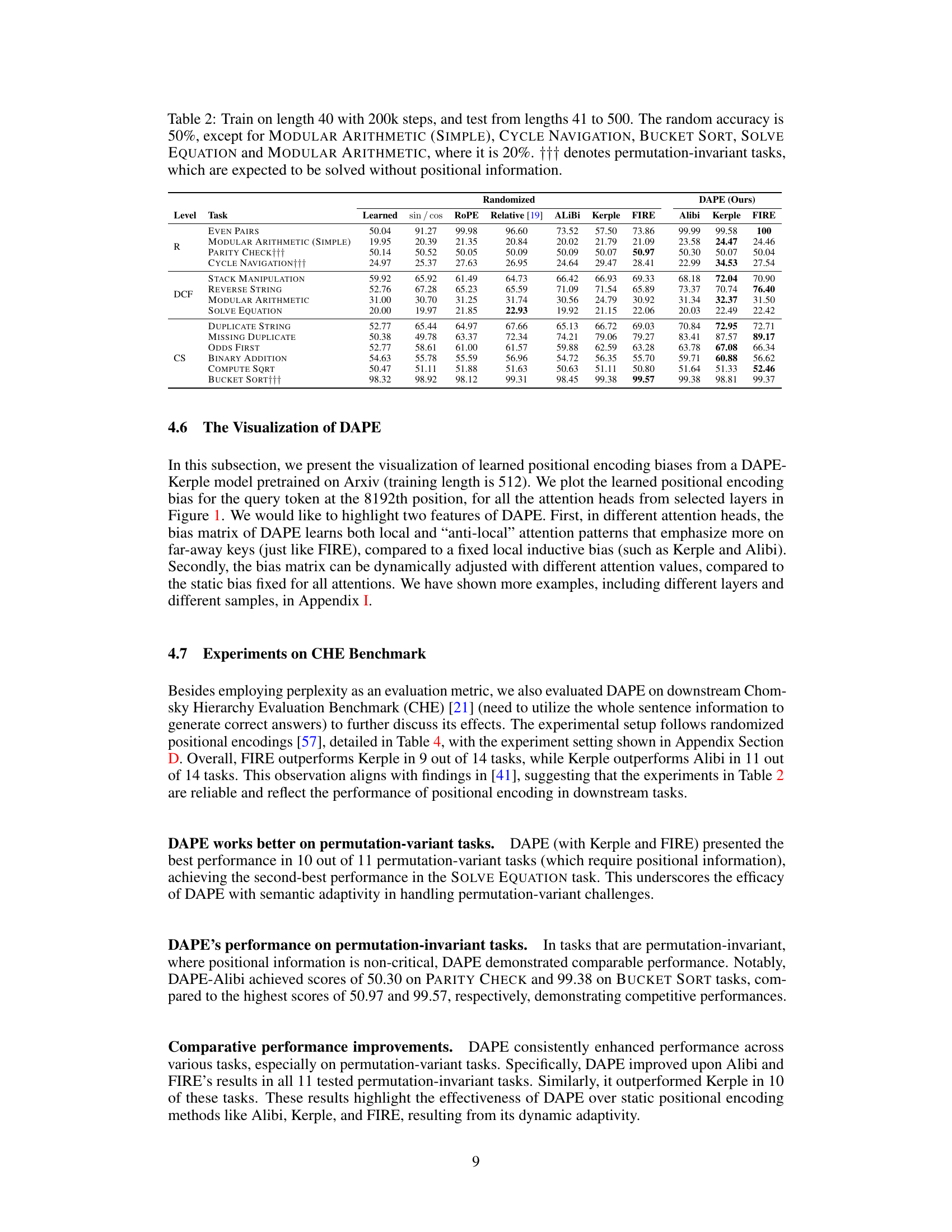

Visual Insights#

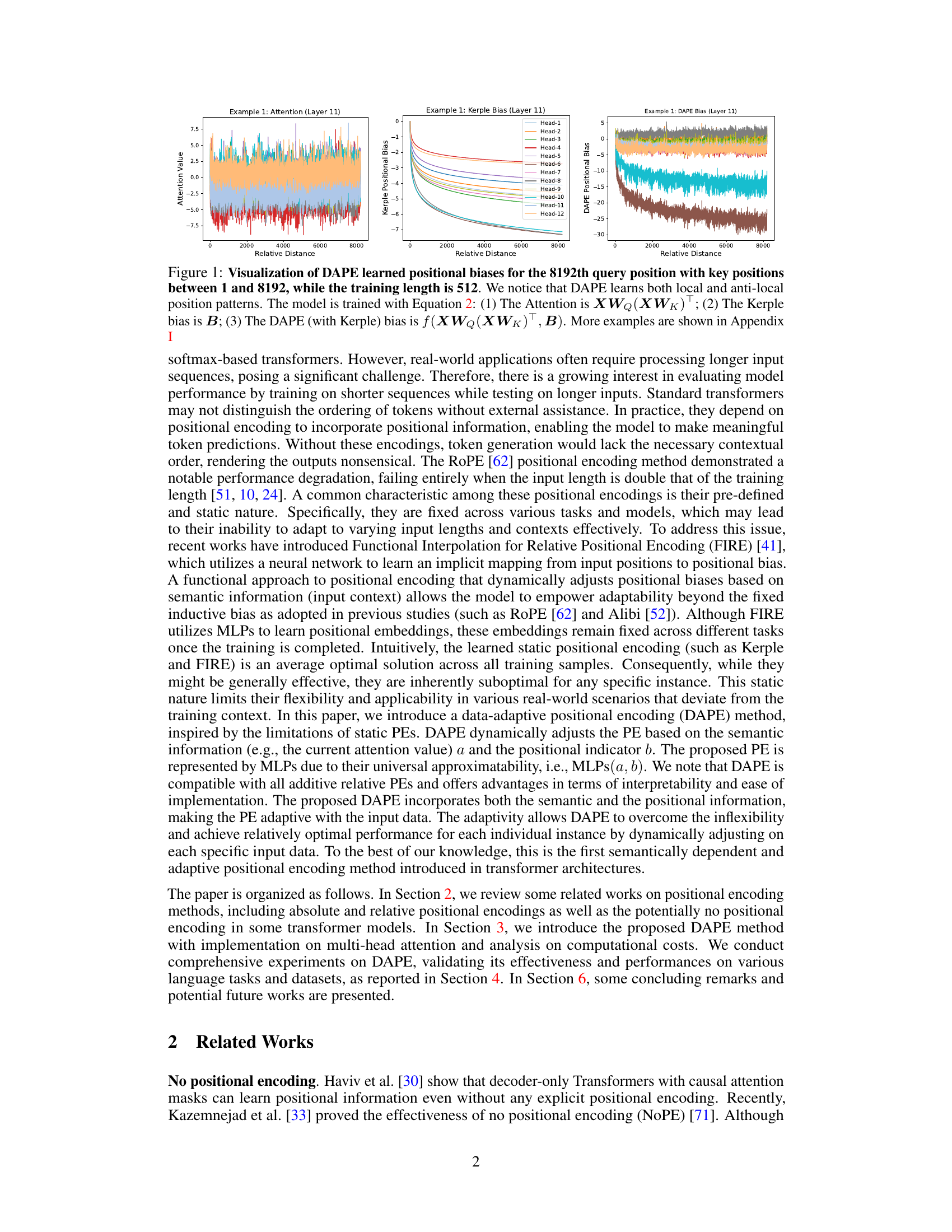

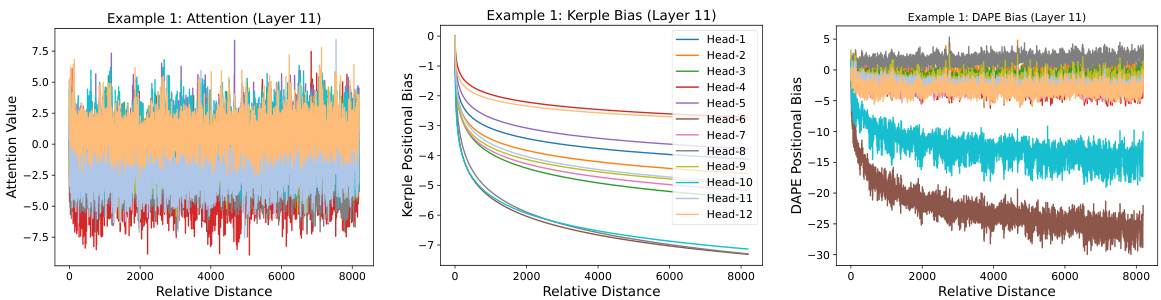

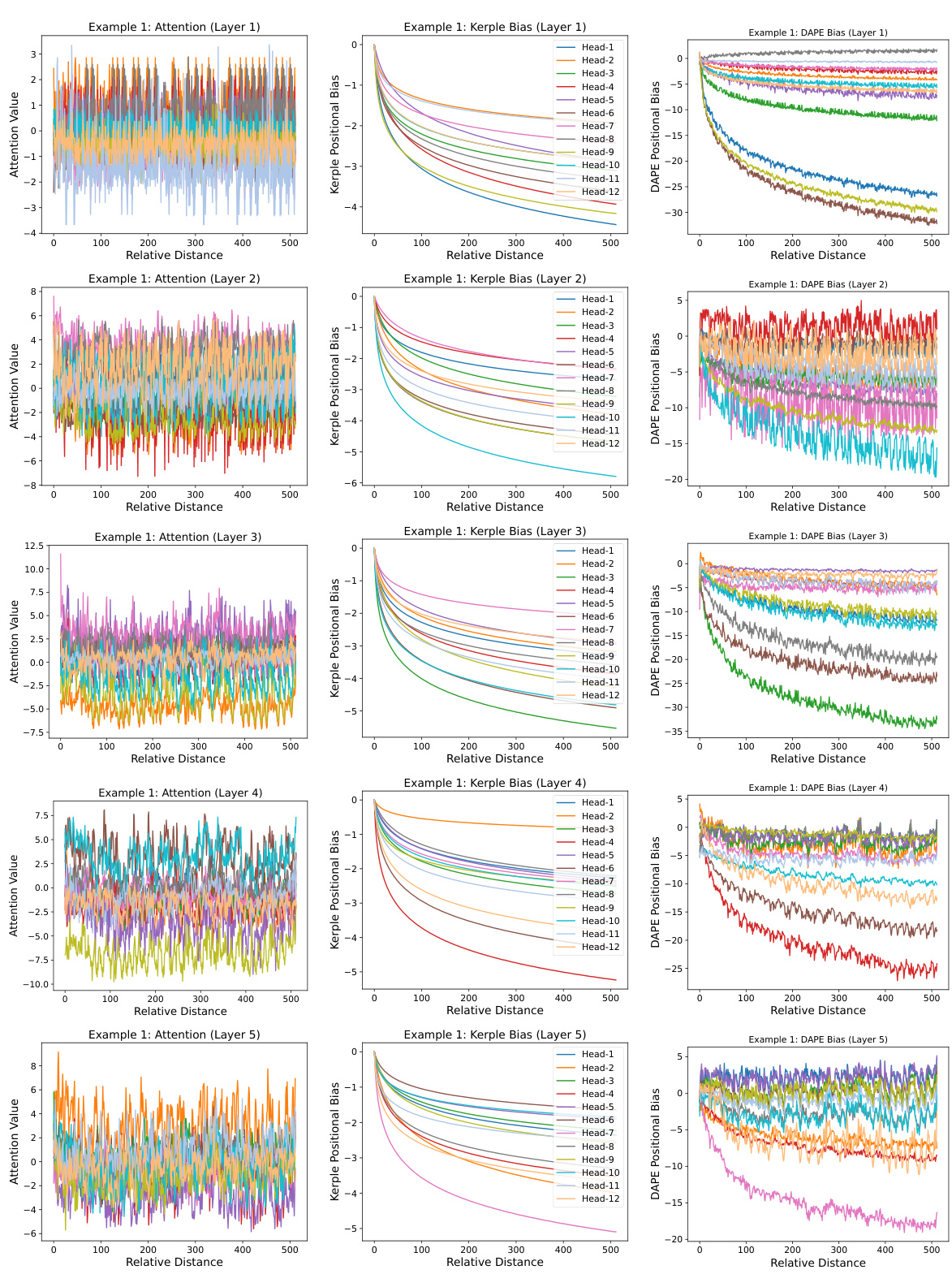

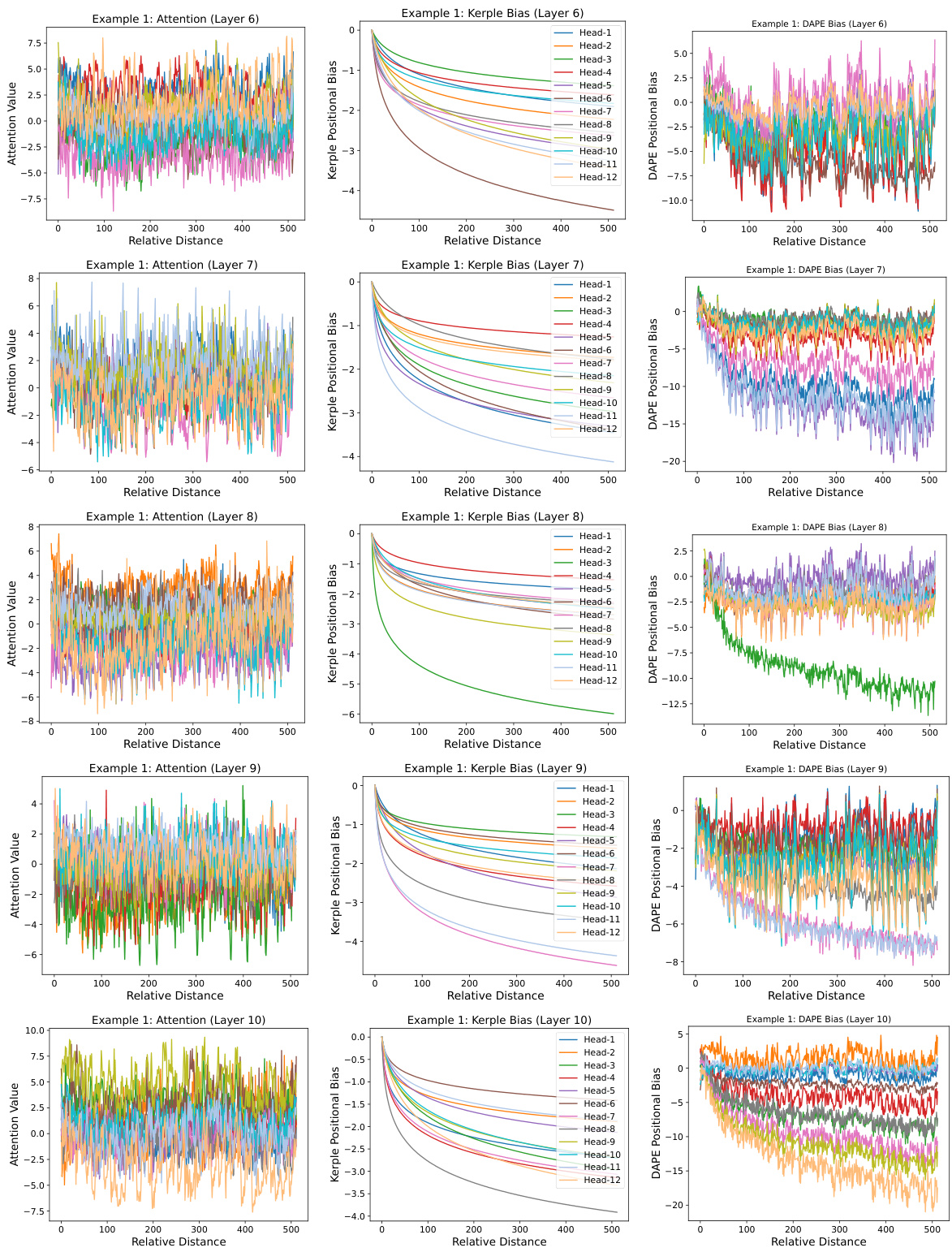

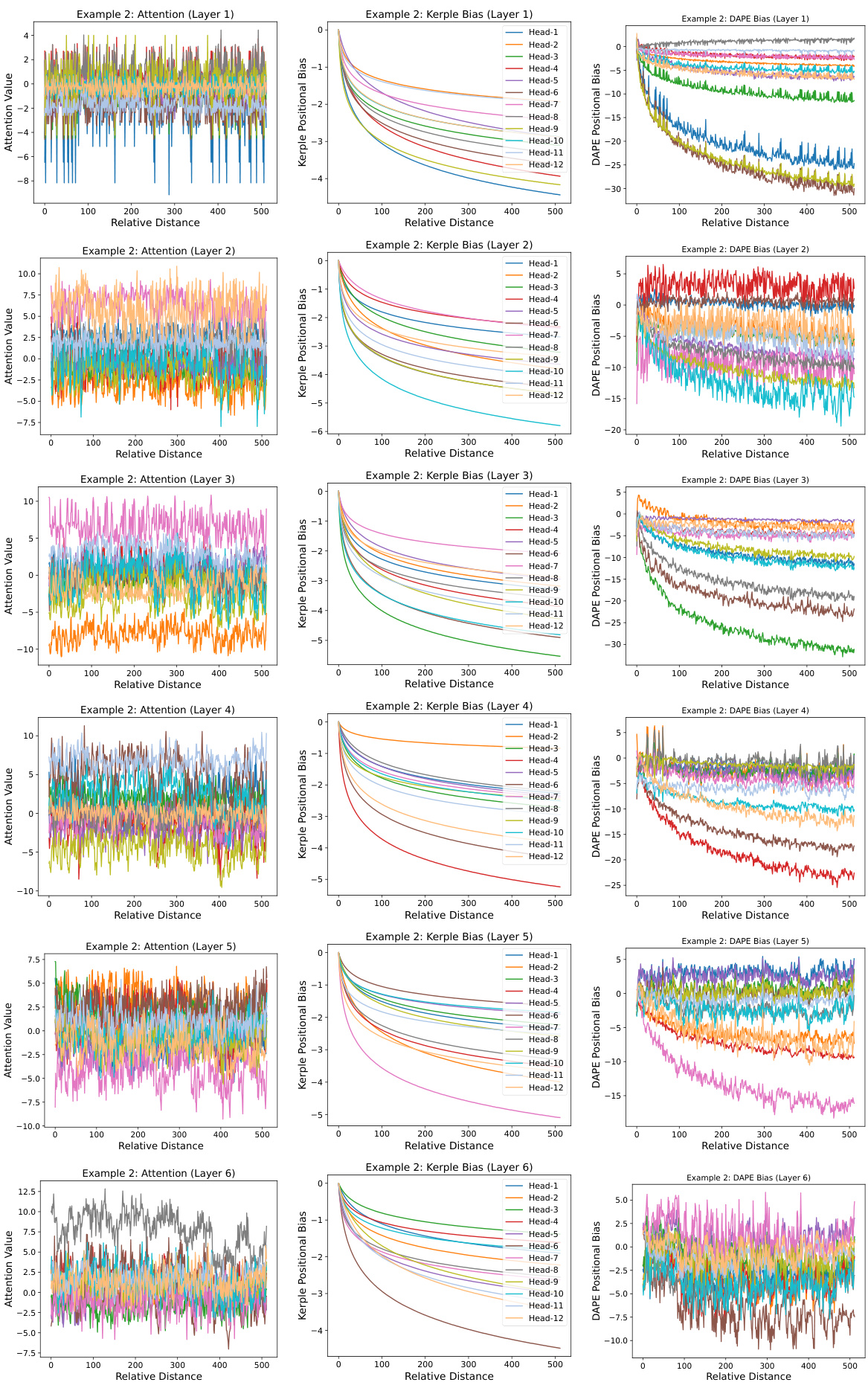

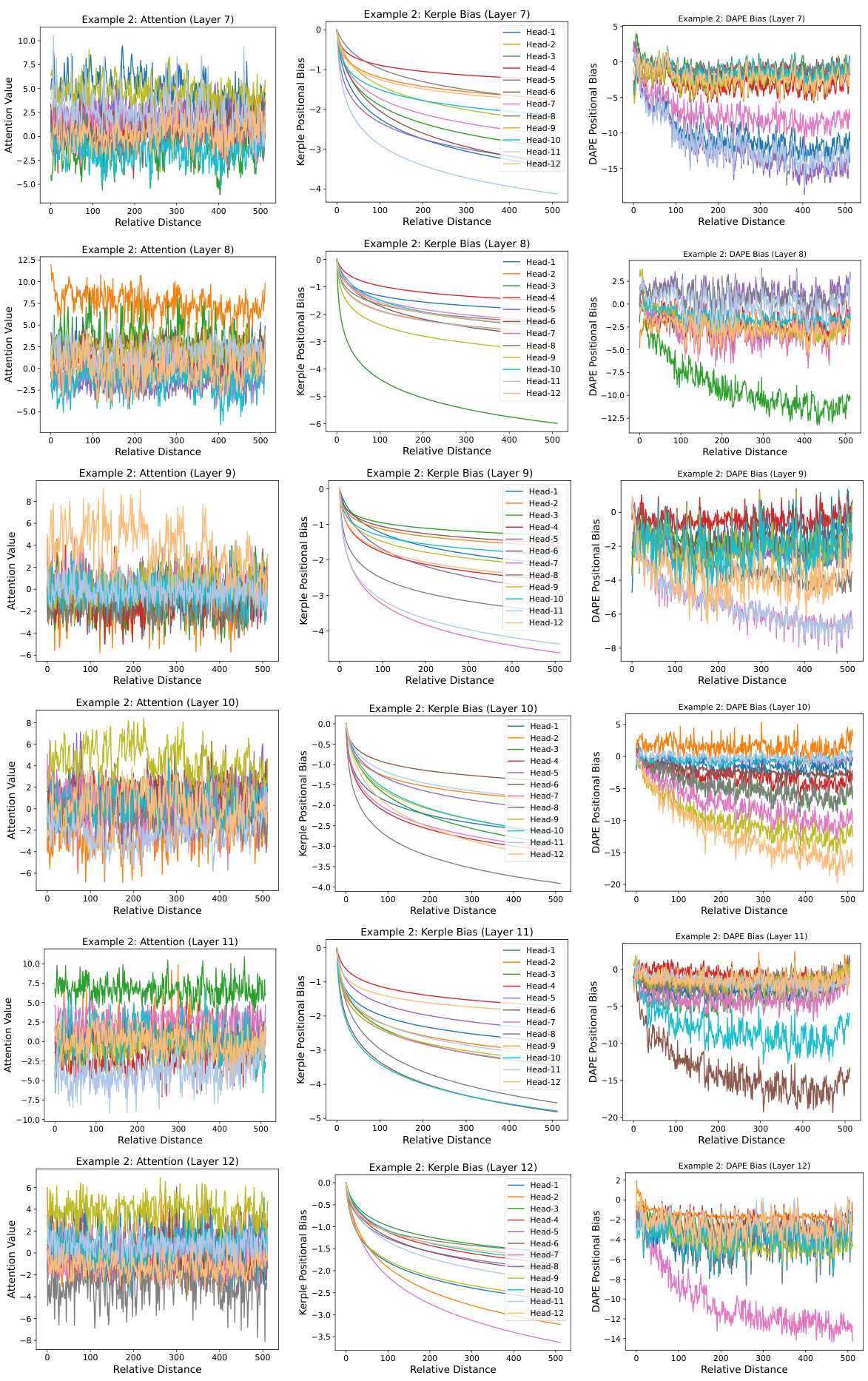

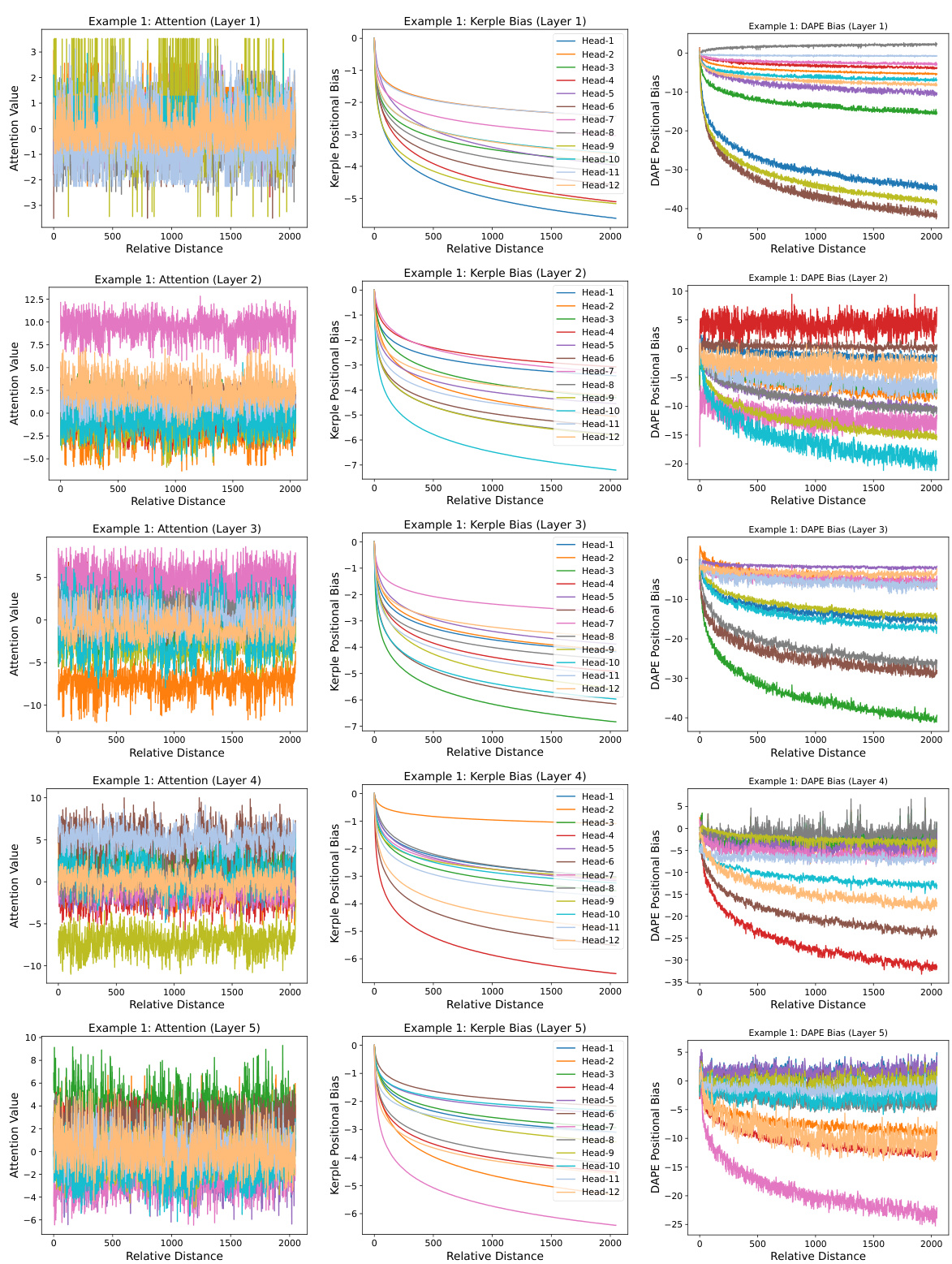

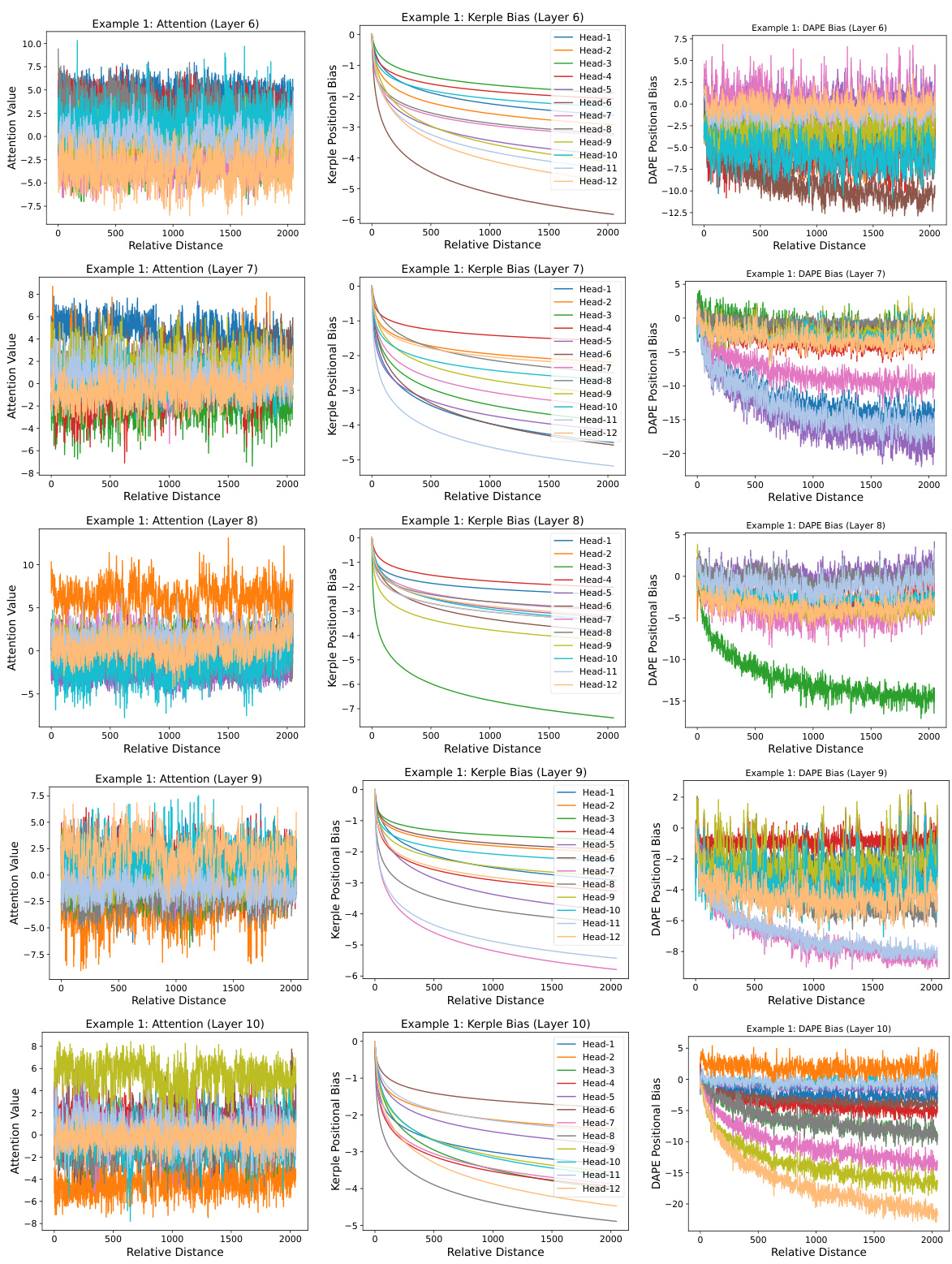

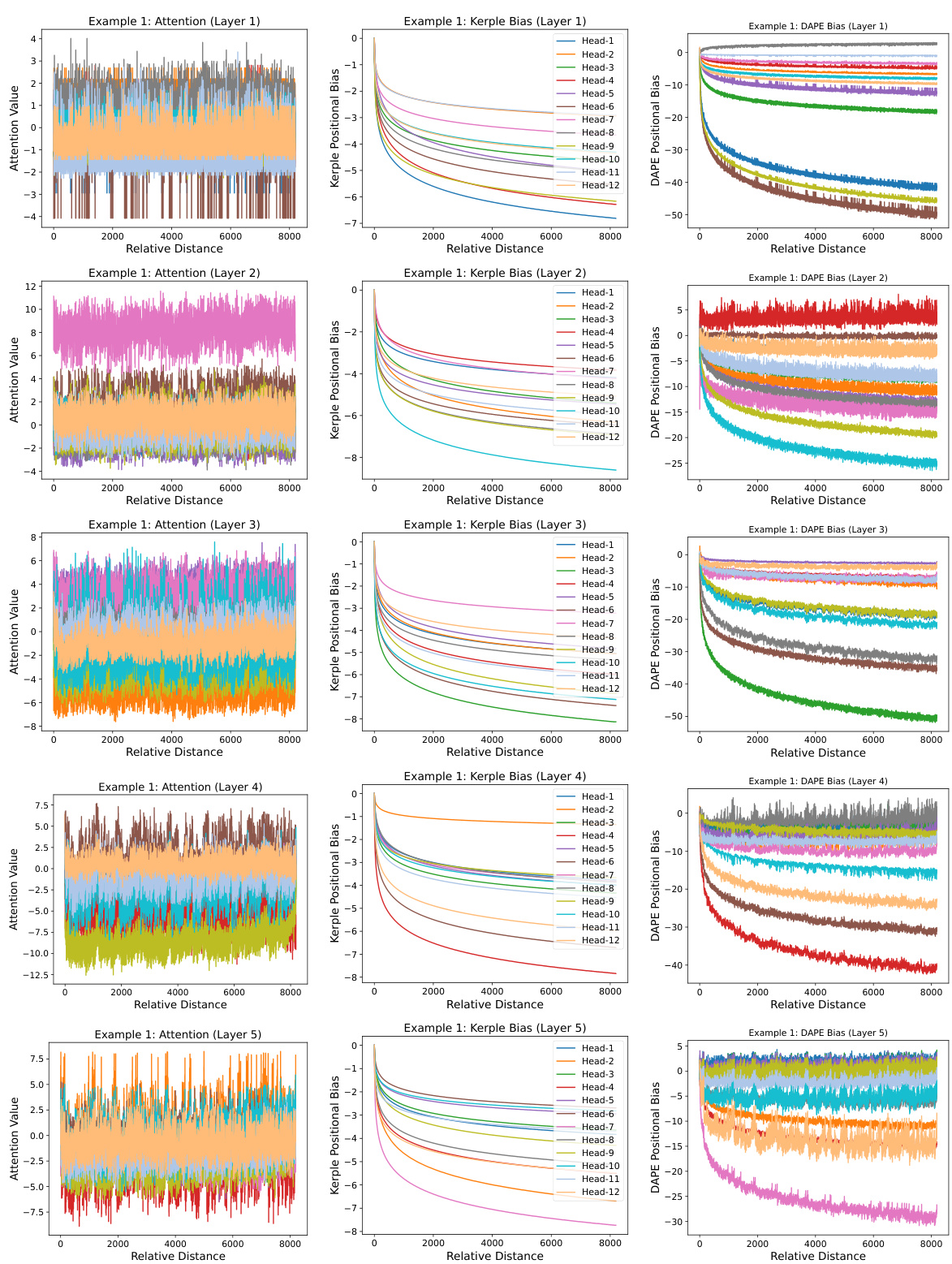

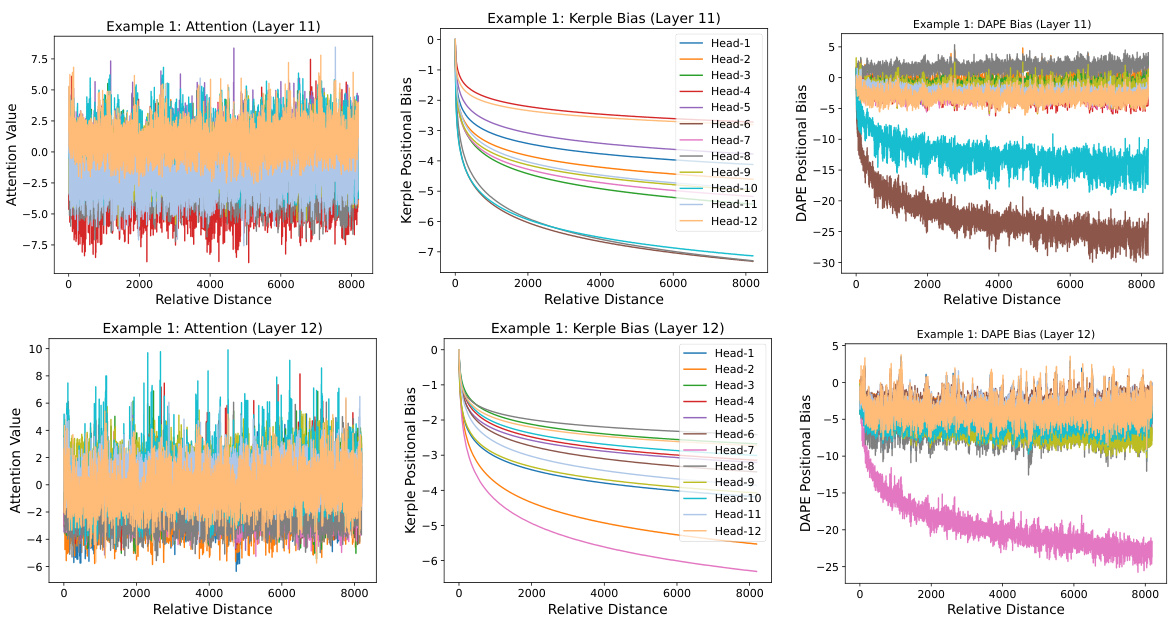

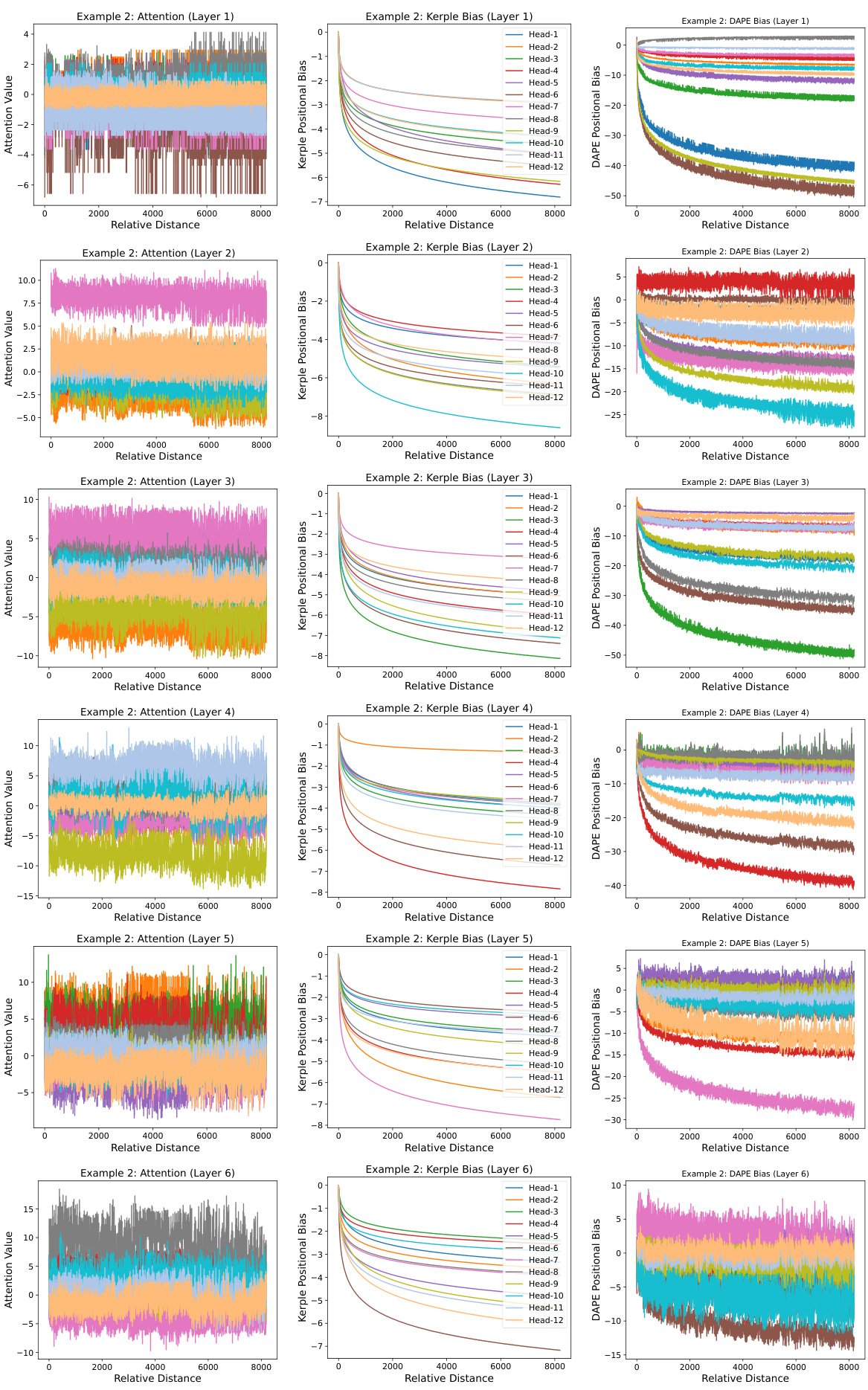

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the DAPE model for the 8192th query position, considering key positions from 1 to 8192 during training with a sequence length of 512. It demonstrates that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, unlike static methods. The figure displays attention values, Kerple bias (a static method), and DAPE bias for comparison, highlighting the adaptive nature of DAPE. More examples are available in the appendix.

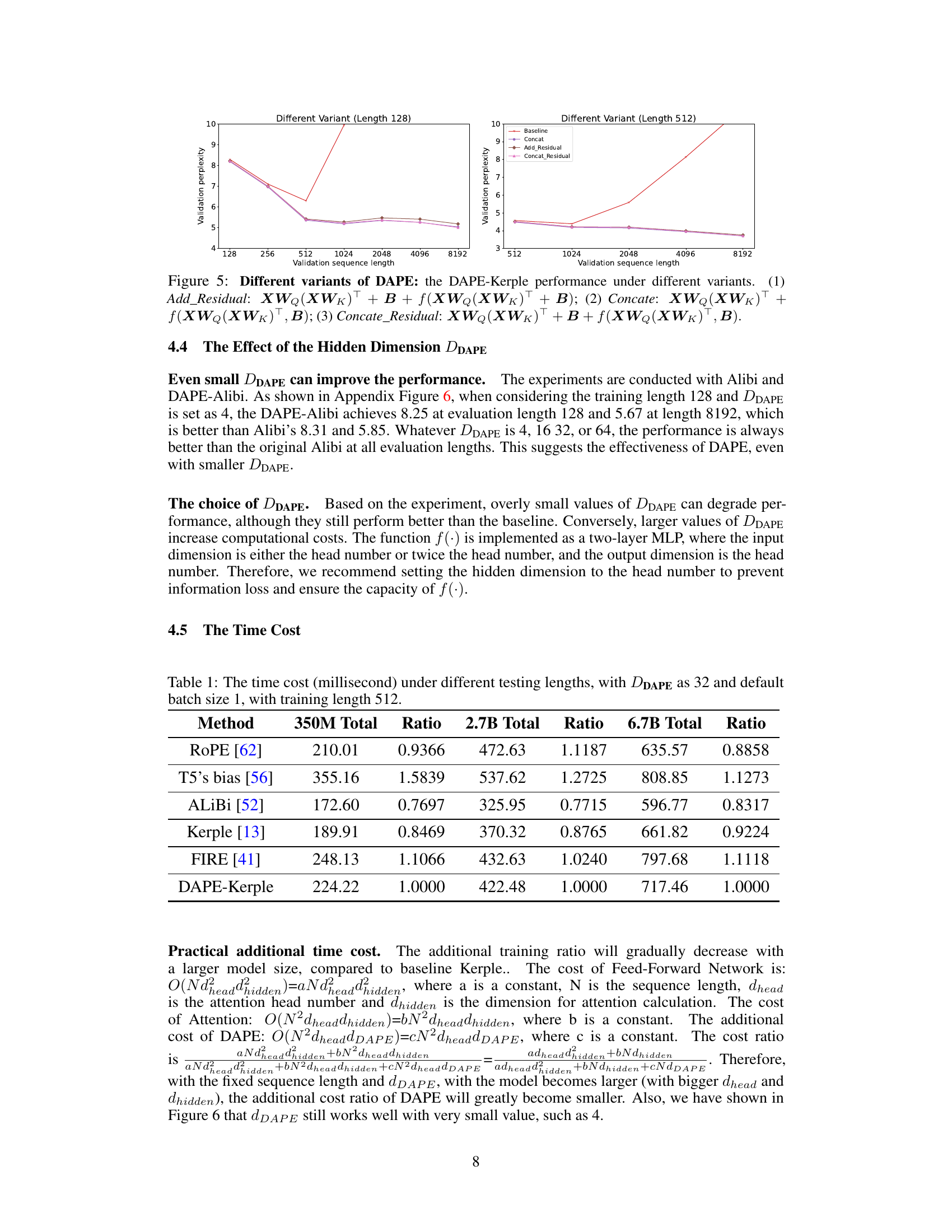

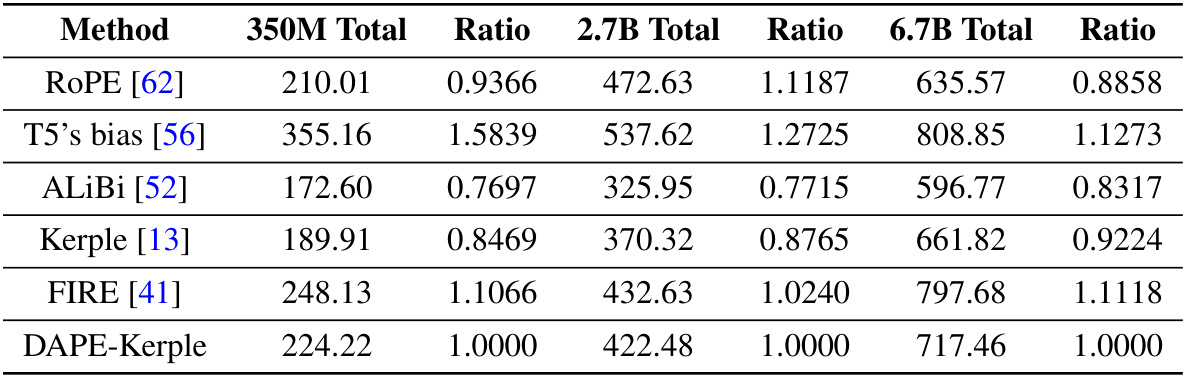

This table presents the computational time, in milliseconds, required for different methods (ROPE, T5’s bias, Alibi, Kerple, FIRE, and DAPE-Kerple) across various sequence lengths (512, 1024, 2048, 4096, and 8192) for three different model sizes (350M, 2.7B, and 6.7B). The ‘Ratio’ column normalizes the time cost relative to DAPE-Kerple for each model size and sequence length. This allows for a direct comparison of the computational efficiency of each method relative to DAPE-Kerple. The training length is fixed at 512 for all experiments.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive Positional Encoding#

Adaptive positional encodings aim to overcome limitations of static methods like Absolute Positional Encoding (APE) and Relative Positional Encoding (RPE) by dynamically adjusting to the input context. Unlike static methods which remain fixed after training, adaptive methods leverage input data and learned priors to modify positional information. This enhances model performance and length generalization, especially crucial for longer sequences beyond training length. Key benefits include improved adaptability to various input lengths and contexts, providing better handling of long-range dependencies. A data-adaptive approach can capture implicit relationships between tokens more effectively, facilitating improved attention mechanisms and, consequently, more accurate predictions. Model visualizations often show that adaptive methods learn both local and anti-local positional relationships, highlighting enhanced expressiveness compared to static techniques. While offering significant advantages, adaptive methods require more computational resources than static alternatives, which is a crucial consideration for implementation.

Length Extrapolation#

Length extrapolation in transformer models addresses the challenge of applying models trained on shorter sequences to significantly longer ones. Existing positional encodings (PEs), crucial for maintaining sequential order, often fail to generalize effectively beyond their training lengths. This limitation stems from their static nature; PEs are fixed during training, irrespective of the input sequence’s actual length. Data-adaptive positional encoding (DAPE) methods aim to mitigate this by dynamically adjusting PEs based on the input context, allowing for better length extrapolation. This adaptive approach is superior to static PEs, which rely on fixed inductive biases and often underperform when encountering longer sequences. DAPE leverages the semantic information inherent in attention mechanisms to dynamically adjust positional information. This enhances the model’s ability to handle longer inputs effectively while also improving overall performance and demonstrating statistical significance in experiments. The key benefit is enhanced adaptability and generalization capabilities, ultimately leading to more robust and efficient transformer models capable of processing longer sequences than those seen during training.

Multi-head DAPE#

The extension of DAPE to a multi-head architecture is a crucial aspect of the paper. It leverages the inherent parallelism of multi-head attention. Instead of sequentially processing each head, the multi-head DAPE processes key-query similarities and bias matrices from all heads simultaneously. This parallel processing significantly improves computational efficiency. A two-layer LeakyReLU neural network parameterizes the function, allowing the model to learn intricate relationships between semantic and positional information across all heads. The integrated approach capitalizes on richer semantic information from the combined attention heads, making positional encoding more robust and contextually relevant compared to single-head approaches. This demonstrates a thoughtful design choice to increase model capacity and performance, reflecting a deep understanding of the transformer architecture and the challenges of long-sequence processing.

Computational Cost#

The computational cost analysis section is crucial for evaluating the practicality of the proposed Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method. The authors acknowledge the inherent quadratic complexity of self-attention mechanisms and the additional overhead of DAPE. However, a key insight is the comparison of DAPE’s added cost with existing methods. By demonstrating that the additional computational cost of DAPE (O(hN²DDAPE)) is significantly less than the quadratic cost of self-attention (O(hN²d + hNd²)) when the hidden dimension of DAPE (DDAPE) is much smaller than the hidden dimension of the attention layer (d), the authors successfully argue for its practicality. This comparison highlights the tradeoff between improved model performance and computational cost, showing that DAPE offers a valuable enhancement without introducing excessive computational burden. Further analysis showing minimal incremental cost when the model scales to larger sizes strengthens this argument. The analysis provides valuable insights into the practical feasibility of deploying the proposed method in real-world applications.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method could explore several promising avenues. Extending DAPE’s adaptability to various transformer architectures beyond the specific models tested is crucial. Investigating the interaction between DAPE and other advanced techniques, such as those designed for efficient long-context processing or improved length generalization, could yield significant performance enhancements. A more thorough exploration of the hyperparameter space for DAPE, and a systematic investigation into their impact on performance across diverse datasets and tasks would further enhance its robustness. Finally, applying DAPE to other modalities beyond natural language processing (NLP), such as computer vision or time-series analysis, presents an exciting opportunity to assess its broader applicability and potential for solving challenging problems in these domains.

More visual insights#

More on figures

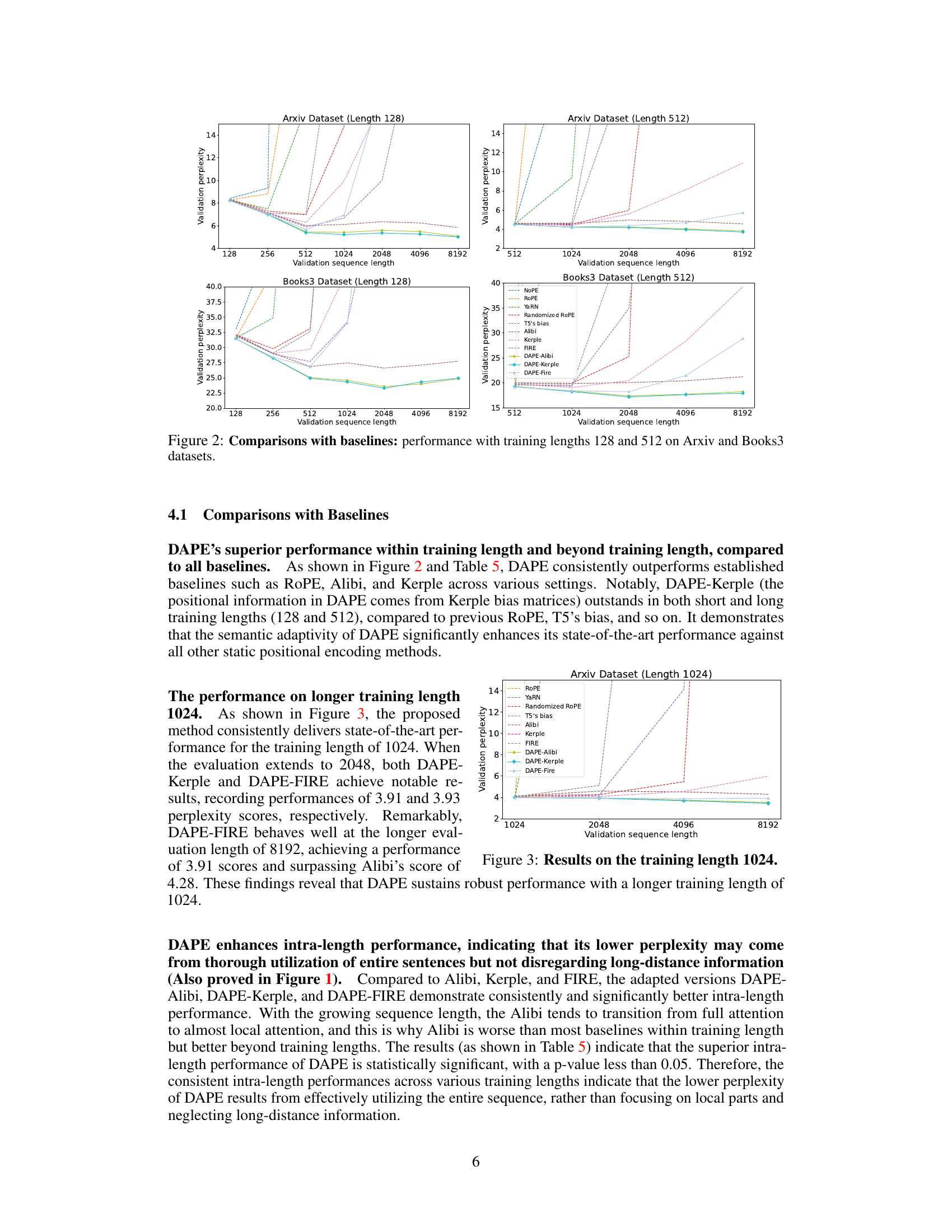

This figure compares the performance of DAPE against several baselines (NoPE, ROPE, YaRN, Randomized ROPE, T5’s bias, Alibi, Kerple, FIRE) across different training lengths (128 and 512) on two datasets (Arxiv and Books3). The x-axis represents the validation sequence length, while the y-axis shows the validation perplexity. The figure demonstrates that DAPE consistently outperforms the baselines, particularly at longer validation sequence lengths.

This figure compares the performance of DAPE against various baselines (ROPE, YaRN, Randomized ROPE, T5’s bias, Alibi, Kerple, FIRE) across different validation sequence lengths (128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192) for two datasets: Arxiv and Books3. The training lengths used are 128 and 512. The results are shown as validation perplexity scores. It visually demonstrates the consistent superior performance of DAPE, particularly DAPE-Kerple, especially in scenarios where the evaluation length exceeds the training length (extrapolation).

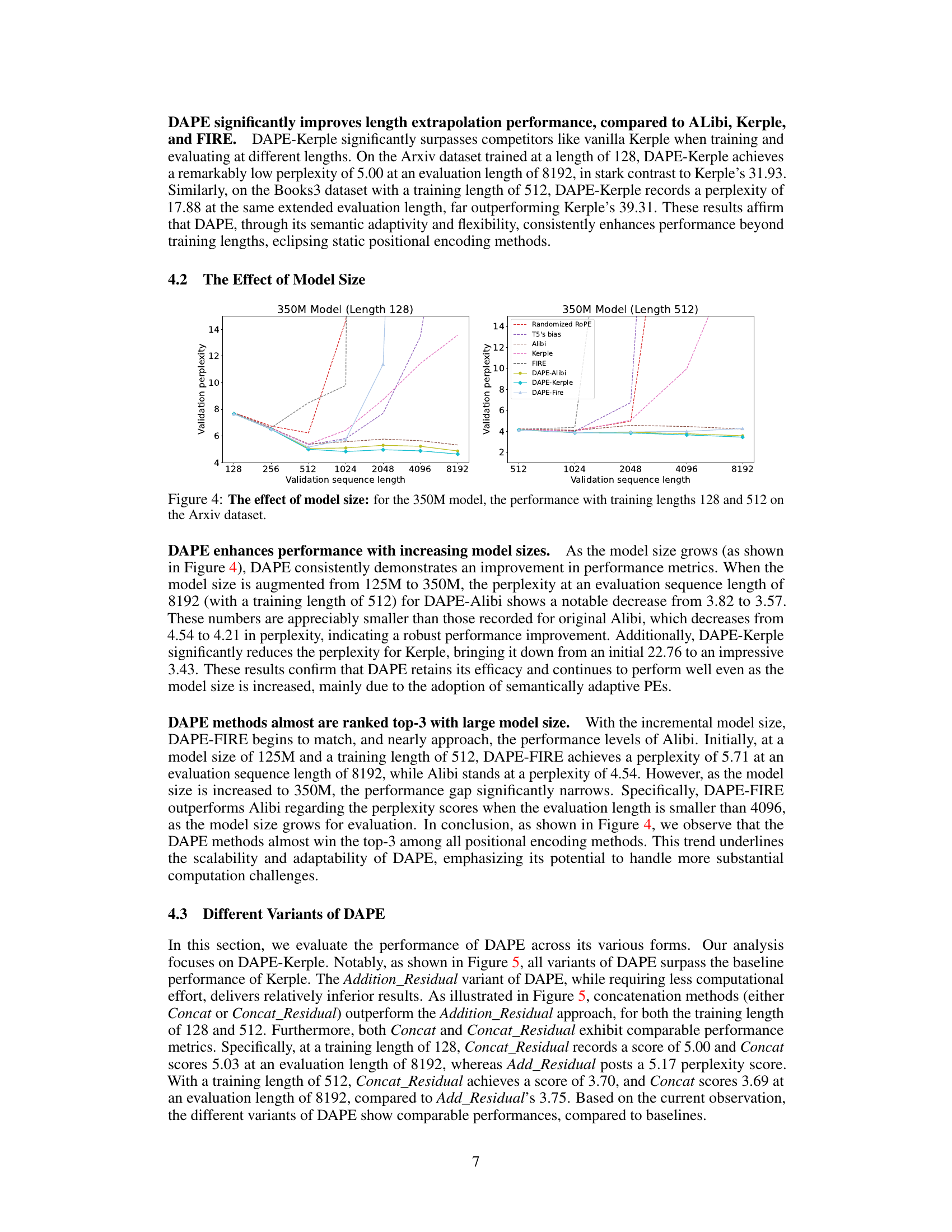

This figure shows how the performance of the 350M model varies with different training lengths (128 and 512) on the Arxiv dataset, as the validation sequence length increases. It compares the perplexity scores of various positional encoding methods. This visualization helps understand the impact of model size on the length generalization capability of different positional encoding methods.

This figure compares the performance of different DAPE variants (Add_Residual, Concat, Concat_Residual) against the baseline (Kerple) method on two different training lengths (128 and 512). It shows the validation perplexity for each method across varying sequence lengths (from 128 to 8192). The results highlight the performance differences between the DAPE variants, illustrating the impact of residual connections and concatenation strategies on the overall model performance.

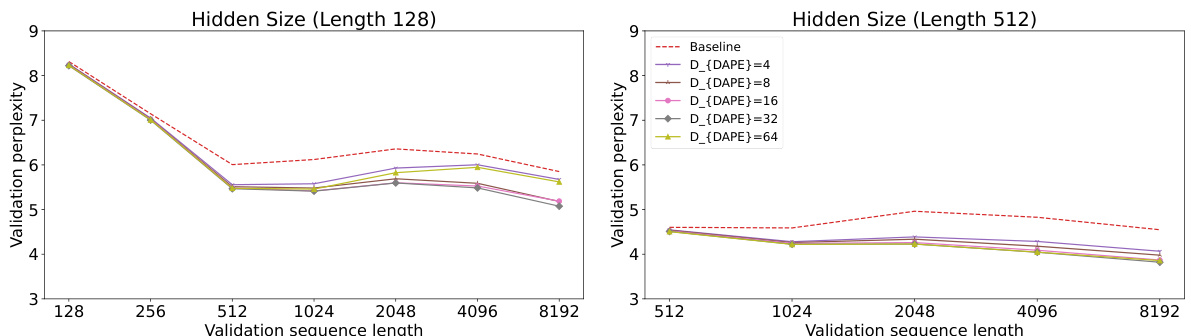

This figure shows the impact of the hidden dimension (DDAPE) in the data-adaptive positional encoding (DAPE) model on the Arxiv dataset. Two training lengths (128 and 512) are shown. The perplexity, a measure of model performance, is plotted against different validation sequence lengths. Multiple lines representing different DDAPE values are compared to a baseline (Alibi) to show how the hidden dimension affects the model’s ability to generalize to longer sequences.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the DAPE model for the 8192th query position. It shows how DAPE (Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding) dynamically adjusts its positional bias based on the input context and learned priors. The figure highlights that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, unlike static methods. Three components are shown for comparison: the attention values, Kerple bias, and the DAPE bias, demonstrating how DAPE modifies the Kerple bias to incorporate both semantic and positional information.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method for the 8192th query position. The training length was 512. The visualization demonstrates that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, unlike traditional static methods. The figure illustrates the attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias, showcasing how DAPE dynamically adjusts the positional encoding based on attention values and fixed priors.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method for a specific query position (8192th) with key positions ranging from 1 to 8192. The training length was 512. The visualization shows that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, indicating its ability to capture both short-range and long-range dependencies between tokens. The figure highlights the difference between the attention values, the Kerple bias, and the DAPE bias, showing how DAPE adjusts positional information based on the context. Additional examples are available in the appendix.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method for a specific query position (8192th) when the training sequence length is 512. It demonstrates that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns by showing the attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias for different key positions. The figure highlights DAPE’s ability to capture both short-range and long-range dependencies in the input sequence.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method. It shows the attention weights for the 8192nd query token against all key tokens (1-8192) when trained with a sequence length of 512. The visualization demonstrates that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, indicating its ability to capture both short-range and long-range dependencies. Three components are shown: attention weights, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias. The DAPE bias is a function of both attention weights and the Kerple bias.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method for a specific query position (8192th) with key positions ranging from 1 to 8192 during training with a sequence length of 512. The visualization reveals that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, indicating its ability to capture both short-range and long-range dependencies in the input sequences. The three subplots show the attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias, respectively, illustrating how DAPE modifies the positional bias based on the attention mechanism and learned priors.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method. It shows the attention weights for the 8192th query token against all key positions (1-8192) when the training sequence length was only 512. The plot demonstrates DAPE’s ability to capture both local and long-range dependencies in the input sequences, a key aspect of its adaptive nature. Three components are shown: The attention values of the model, the Kerple bias (a type of relative positional encoding), and finally, the DAPE bias (the combination of the attention and Kerple bias after being processed by an MLP). The visualization highlights the DAPE’s ability to learn and adjust positional information based on the input context, in contrast to static positional encodings.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the DAPE model for a specific query position (8192th) with different key positions (1-8192). The training sequence length was 512. The visualization shows that DAPE captures both local and long-range relationships between positions, unlike traditional static methods. The three subplots show the attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias, respectively, demonstrating how DAPE adjusts positional biases based on both learned priors and the current attention values. The equations used to train the model are included, and more examples are available in Appendix I.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method. It shows how DAPE, when trained on sequences of length 512, learns positional biases for a query token at position 8192, considering key positions from 1 to 8192. The key takeaway is that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, unlike static positional encodings. The visualization uses three subplots: Attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias. Each subplot shows the bias for each of the twelve attention heads of the model, displaying the learned interaction between the query and key positions. The appendix contains additional examples of these learned biases.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method. It shows the attention biases for the 8192nd query token interacting with key tokens from positions 1 to 8192, while the model was trained with a sequence length of only 512. The visualization demonstrates that DAPE successfully learns both local and anti-local positional relationships, showcasing its adaptability to longer sequences than those seen during training. The three panels show the attention values, the Kerple bias (a baseline positional encoding method), and the DAPE bias, respectively. The DAPE bias is generated by an MLP that takes as input both the attention values and the Kerple bias. The appendix contains additional examples of learned positional biases.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the DAPE model. It shows the attention weights between the 8192th query token and all other key tokens (1-8192) during training with a sequence length of 512. The visualization demonstrates that DAPE learns both short-range (local) and long-range (anti-local) relationships between tokens, a key aspect of its adaptability. The three subplots represent the attention weights, Kerple bias, and the DAPE bias respectively. More detailed examples are provided in the appendix.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method for a specific query position (8192th) within a sequence. The training length was 512, but the key positions range from 1 to 8192 to assess length extrapolation capabilities. The visualization shows that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional relationships, which means it considers the relative positions of tokens both close to and far from the query token. This is in contrast to traditional methods that mostly rely on local information. The figure also illustrates the attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias. Appendix I contains additional examples.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the Data-Adaptive Positional Encoding (DAPE) method for a specific query position (8192th) and its corresponding key positions (1 to 8192) during training with a sequence length of 512. The visualization shows that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, indicating its ability to capture both short-range and long-range dependencies. The three panels illustrate the attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias, respectively, highlighting how DAPE incorporates the Kerple bias to learn adaptive positional information. Additional examples are available in the appendix.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the DAPE model. It shows the attention weights between the 8192th query position and all key positions (1-8192) when the model is trained with a sequence length of 512. The visualization demonstrates that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns, which is different from traditional static positional encodings. The three panels display the attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias respectively. This adaptive learning of positional biases allows DAPE to generalize better to longer sequences.

This figure visualizes the learned positional biases of the DAPE model for the 8192th query position when the training length is 512. It demonstrates that DAPE learns both local and anti-local positional patterns by showing the attention values, Kerple bias, and DAPE bias for different head numbers. The model is trained using Equation 2 which includes attention, Kerple bias, and a function of both. More visualization examples are available in Appendix I.

More on tables

This table presents the results of experiments conducted on the CHE benchmark. The models were trained on sequences of length 40 for 200,000 steps and then tested on sequences ranging from length 41 to 500. The table shows the accuracy achieved by various models, including different positional encoding methods (learned sinusoidal, ROPE, Relative, ALiBi, Kerple, FIRE, and DAPE), on several tasks. The random accuracy is 50% for most tasks, except for specific tasks noted in the caption.

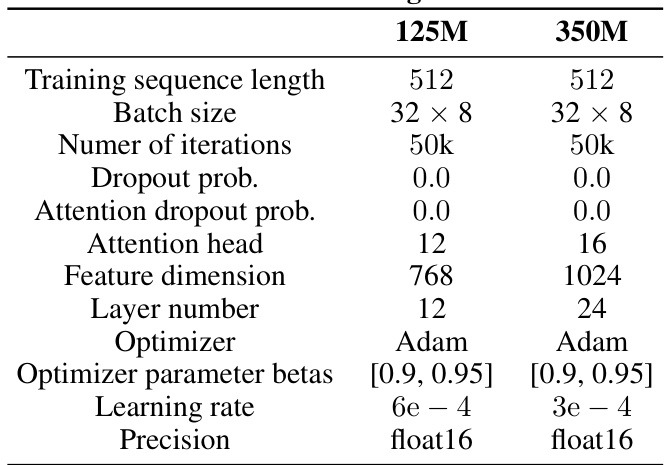

This table details the configurations used for the 125M and 350M transformer models in the experiments. The configurations include training sequence length, batch size, number of iterations, dropout probability, attention dropout probability, number of attention heads, feature dimension, number of layers, optimizer, optimizer parameter betas, learning rate, and precision. These parameters are crucial for reproducibility and understanding the experimental setup.

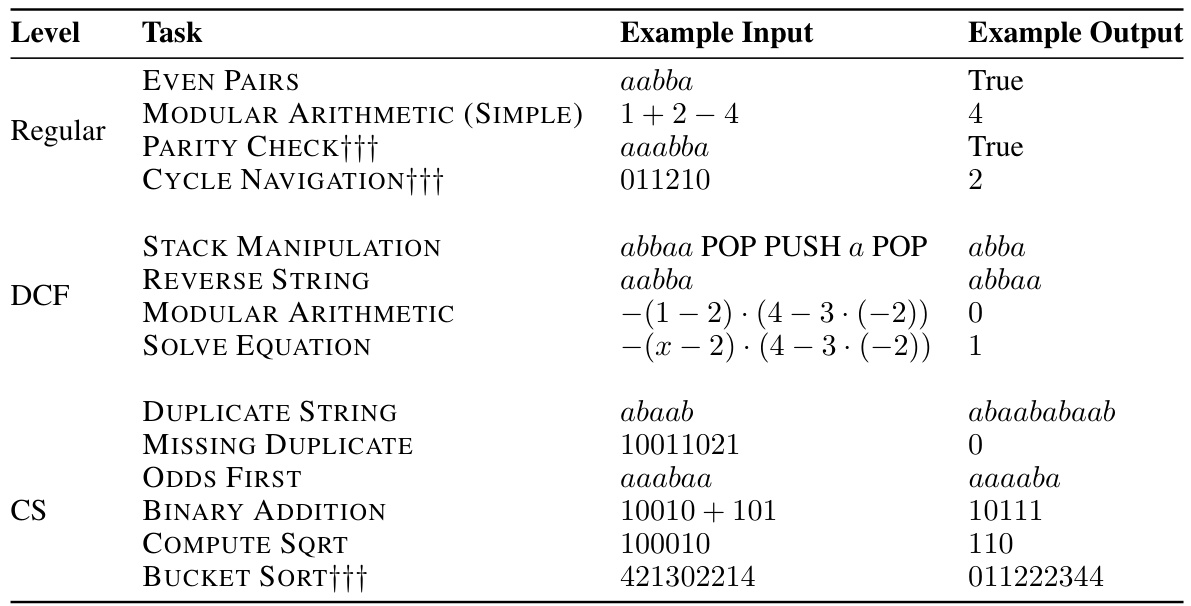

This table presents examples of tasks from the Chomsky Hierarchy Evaluation Benchmark (CHE) used to evaluate the model’s performance. It categorizes tasks into levels based on their complexity according to the Chomsky Hierarchy (Regular, Context-Free, Context-Sensitive, and Recursively Enumerable). Each task demonstrates a different type of language processing challenge, with examples provided for input and expected output. Permutation-invariant tasks (marked with †††) are those where the order of input elements does not affect the outcome.

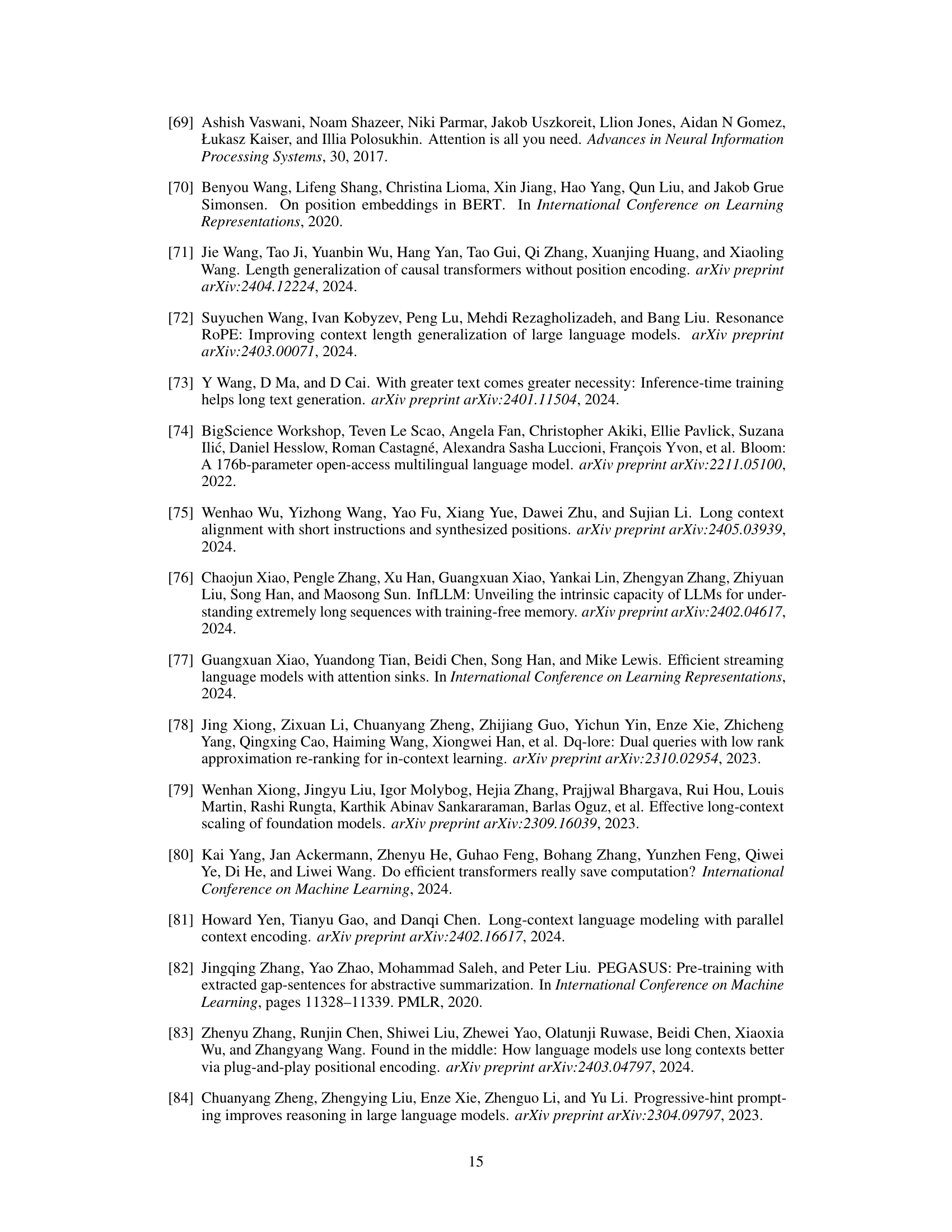

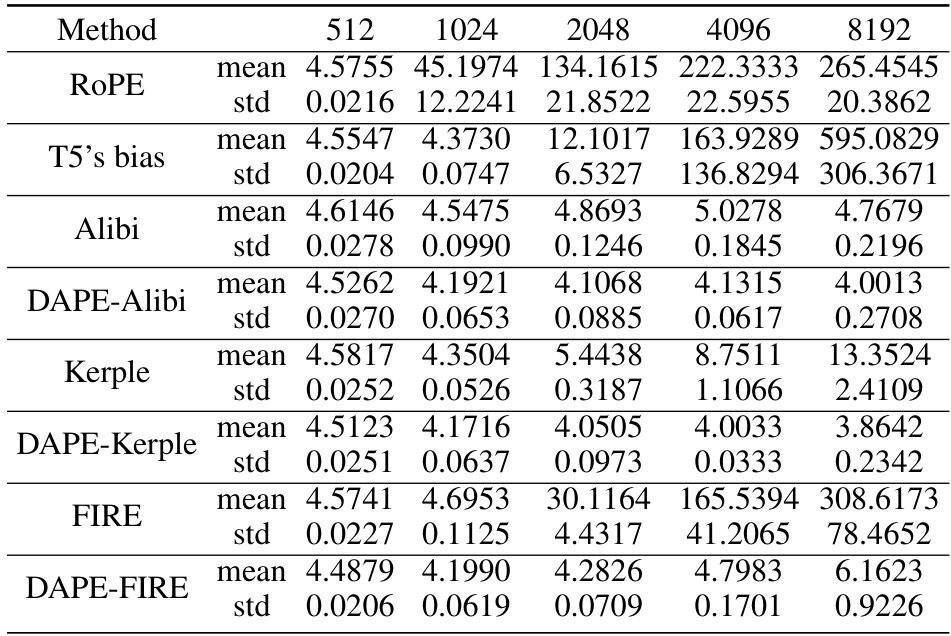

This table presents the perplexity scores obtained using various methods (ROPE, T5’s bias, Alibi, DAPE-Alibi, Kerple, DAPE-Kerple, FIRE, DAPE-FIRE) on the Arxiv dataset. The training length was 512, and the results are averaged across three random seeds for various evaluation sequence lengths (512, 1024, 2048, 4096, and 8192). The standard deviation is also provided to indicate variability.

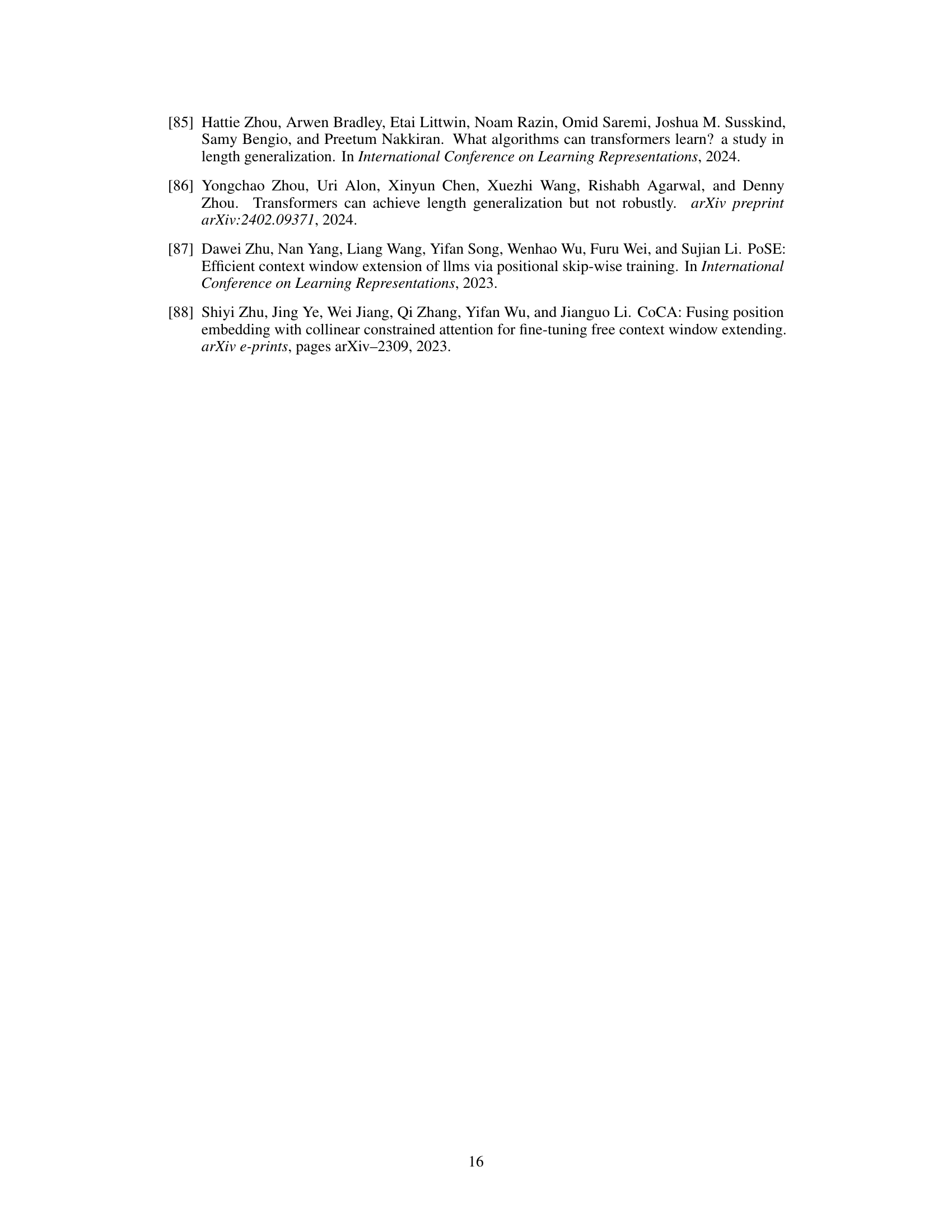

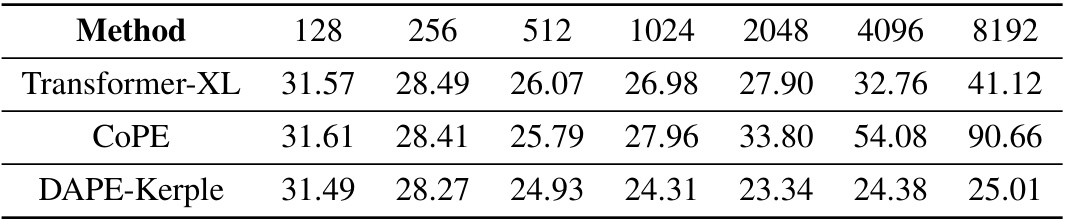

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different positional encoding methods, specifically Transformer-XL, CoPE, and DAPE-Kerple, on the Books3 dataset. The comparison is based on the performance at different sequence lengths (128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096, and 8192), all using a training sequence length of 128. The values represent a performance metric (likely perplexity or a similar measure of model performance on the task).

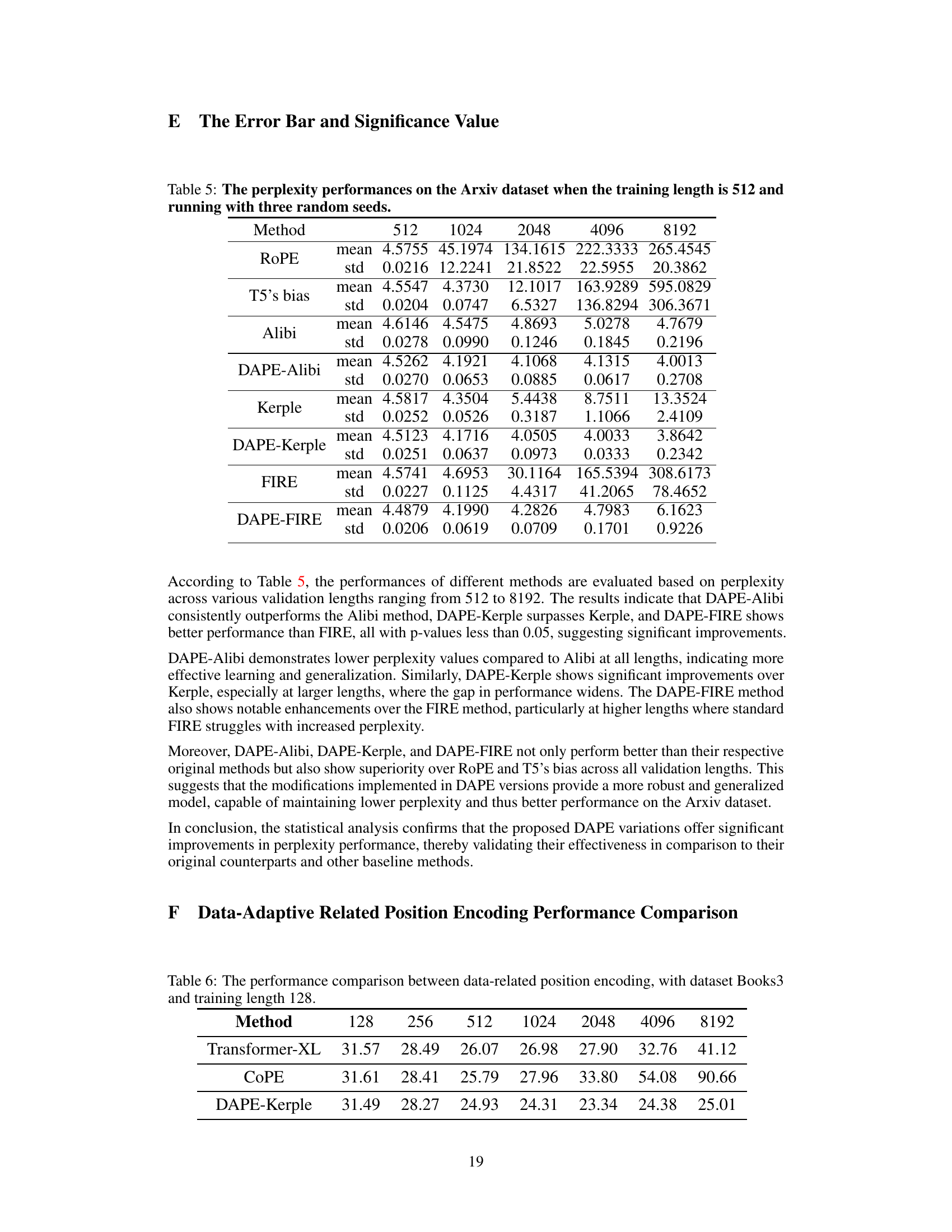

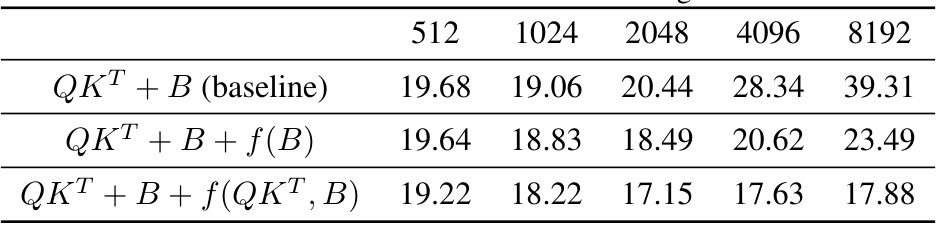

This table presents the perplexity results on the Books3 dataset for different sequence lengths (512, 1024, 2048, 4096, 8192) using three different methods. The baseline method uses the standard query-key multiplication with bias (QKT + B). The second method adds a function f(B) of the bias matrix to improve the model’s performance. The third and improved method further incorporates a function f(QKT,B) of the query-key multiplication and bias to adapt positional encoding dynamically, enhancing performance further.

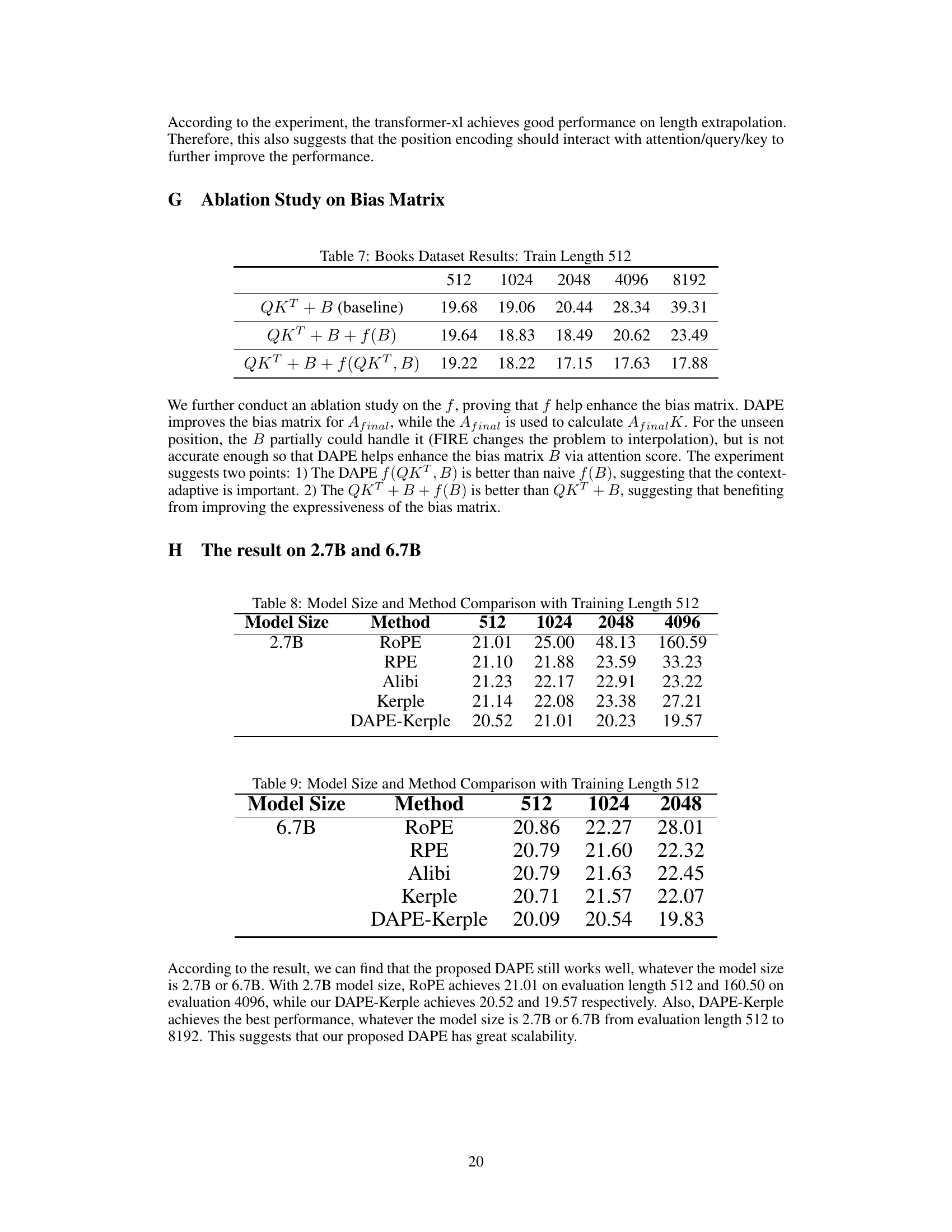

This table compares the performance of different positional encoding methods (ROPE, RPE, Alibi, Kerple, and DAPE-Kerple) across various sequence lengths (512, 1024, 2048, and 4096) using a 2.7B parameter model. The results demonstrate the performance of each method on longer sequences than those used during training, highlighting how well the positional encoding methods extrapolate to unseen sequence lengths.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of various positional encoding methods (ROPE, RPE, Alibi, Kerple, and DAPE-Kerple) using different model sizes (6.7B parameters). The performance is evaluated based on perplexity scores across various sequence lengths (512, 1024, and 2048 tokens). The results highlight the relative performance of each method for different model sizes and sequence lengths, demonstrating their scalability and effectiveness in handling longer contexts.

Full paper#