↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Long-horizon robotic tasks, involving sequences of sub-tasks, are challenging due to error accumulation from imperfect skill learning or execution disturbances. Existing skill chaining methods often struggle with these issues, leading to unstable and unreliable task completion.

The paper introduces Skill Chaining via Dual Regularization (SCaR) to address these challenges. SCaR uses dual regularization during sub-task skill pre-training and fine-tuning to enhance both intra-skill (within each sub-task) and inter-skill (between sequential sub-tasks) dependencies. Experiments on various benchmarks show that SCaR significantly outperforms existing methods, achieving higher success rates and demonstrating greater robustness to perturbations. This is a valuable contribution to the field of long-horizon robotic manipulation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on long-horizon robotic manipulation. It addresses the critical challenge of error accumulation in skill chaining, a common approach for complex tasks. The proposed framework, SCaR, offers a significant improvement in robustness and success rate, paving the way for more reliable and adaptable robots in real-world applications. This work also opens new avenues for research in adaptive skill learning and dual regularization techniques.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates three scenarios related to stool assembly using a robot. The top row (a) shows the failure that can result from poorly trained sub-task skills where the robot drops a leg. The middle row (b) shows how a disturbance, such as bumping into a cushion, can cause the skill chaining to fail, even if the individual skills were well-trained. The bottom row (c) depicts the successful execution of the task using the proposed Skill Chaining via Dual Regularization (SCaR) method, which enhances both intra-skill and inter-skill dependencies, resulting in stable and smooth assembly.

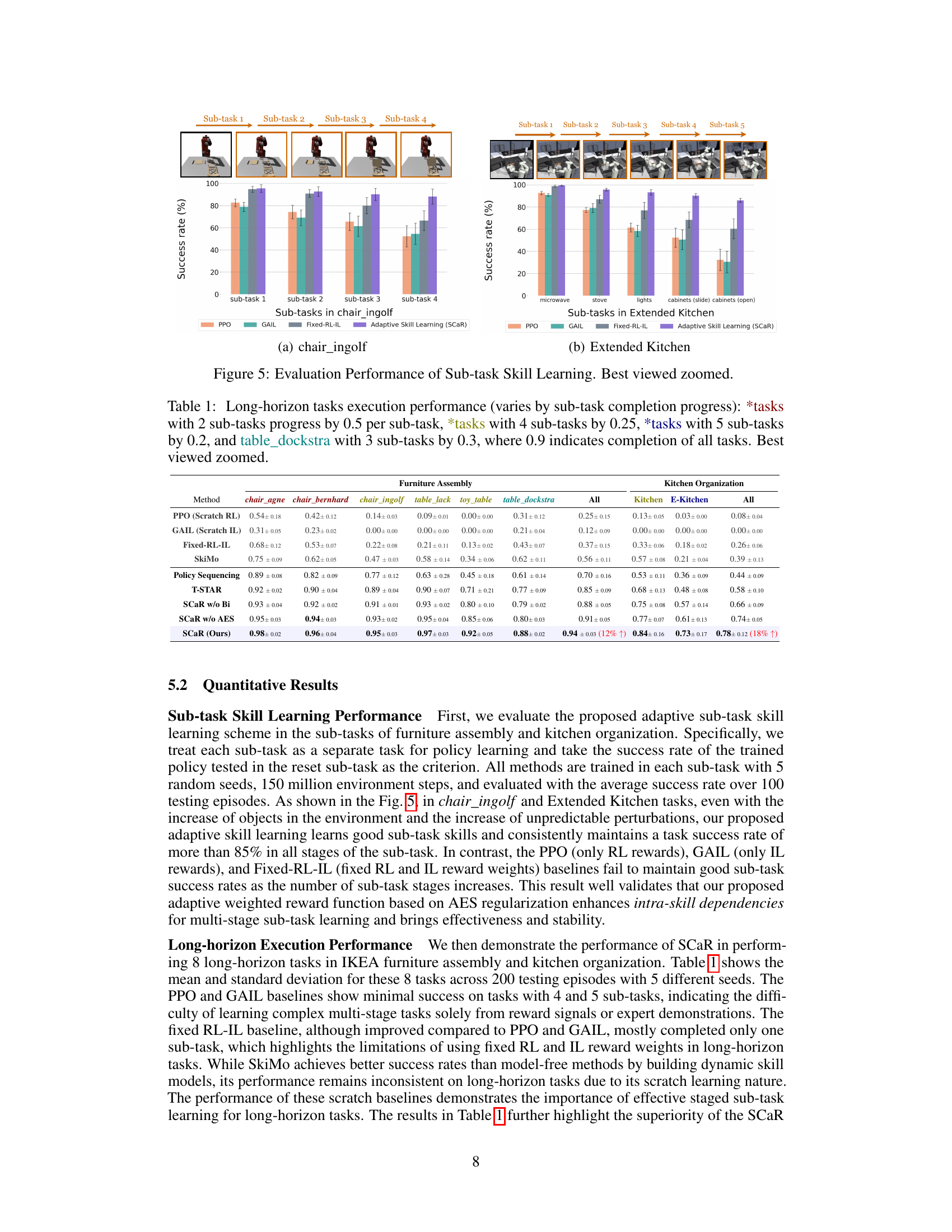

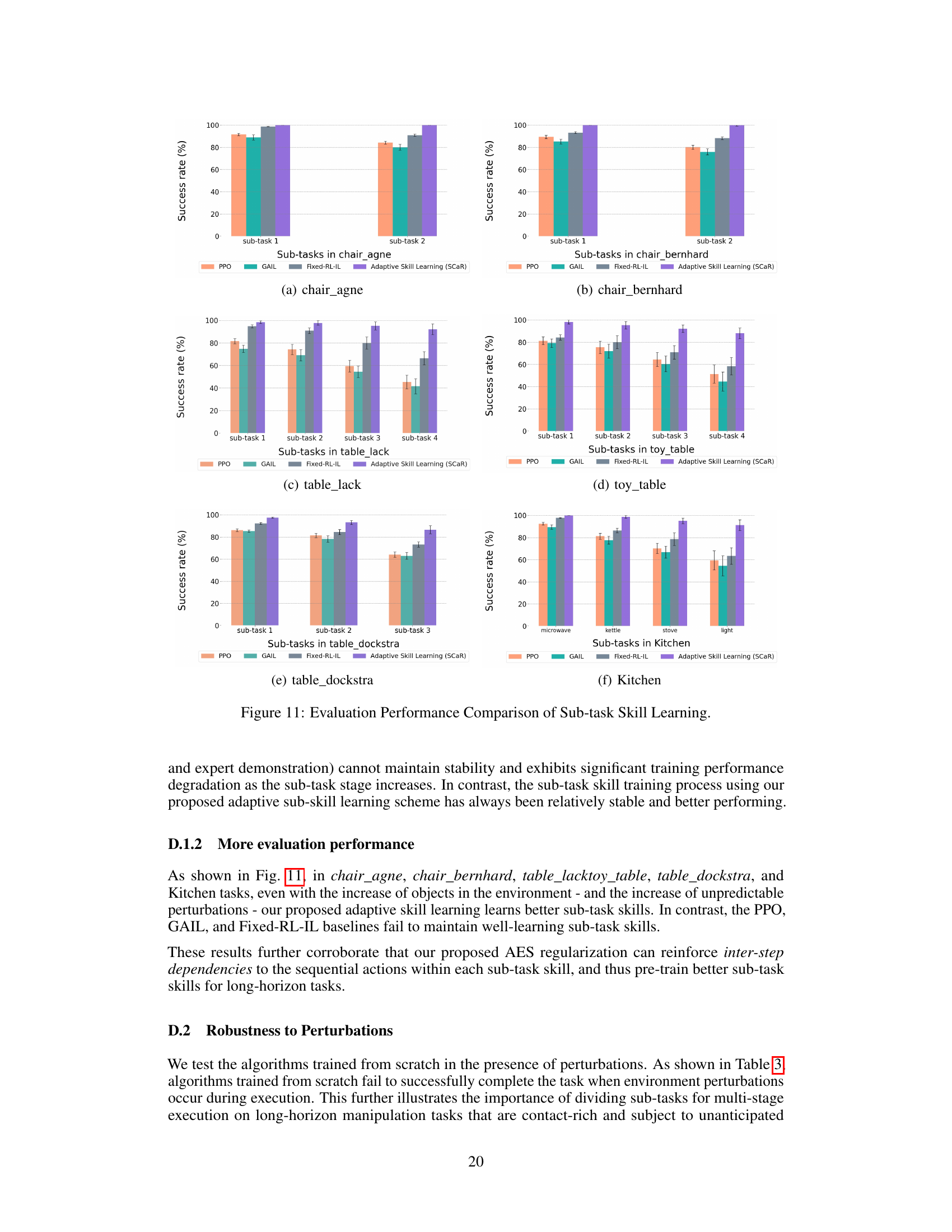

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of different methods (PPO, GAIL, Fixed-RL-IL, SkiMo, Policy Sequencing, T-STAR, SCaR w/o Bi, SCaR w/o AES, and SCaR) across various long-horizon robotic manipulation tasks (six IKEA furniture assembly tasks and two kitchen organization tasks). The success rate for each method is shown as the average completion rate across multiple trials and reflects the proportion of times the robot successfully completes all subtasks in the long-horizon task. The table also indicates how the success rate is calculated for different numbers of subtasks.

In-depth insights#

Dual Regularization#

The concept of “Dual Regularization” in the context of skill chaining for long-horizon robotic manipulation is a powerful technique to enhance both intra-skill and inter-skill dependencies. Intra-skill regularization focuses on strengthening the connections between sequential actions within a single sub-task, ensuring smooth and reliable execution of that individual skill. Inter-skill regularization, on the other hand, aims to improve the transitions between consecutive sub-tasks, creating a seamless flow from one skill to the next. This dual approach is crucial because imperfections in individual skill learning or environmental disturbances can lead to error accumulation; dual regularization mitigates these issues by promoting both internal consistency within each skill and robust coordination between skills. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated through improved success rates in complex, long-horizon tasks compared to baselines that only address one type of dependency. The adaptive nature of the regularization, where the emphasis shifts between intra and inter-skill aspects during training, further enhances robustness and overall performance.

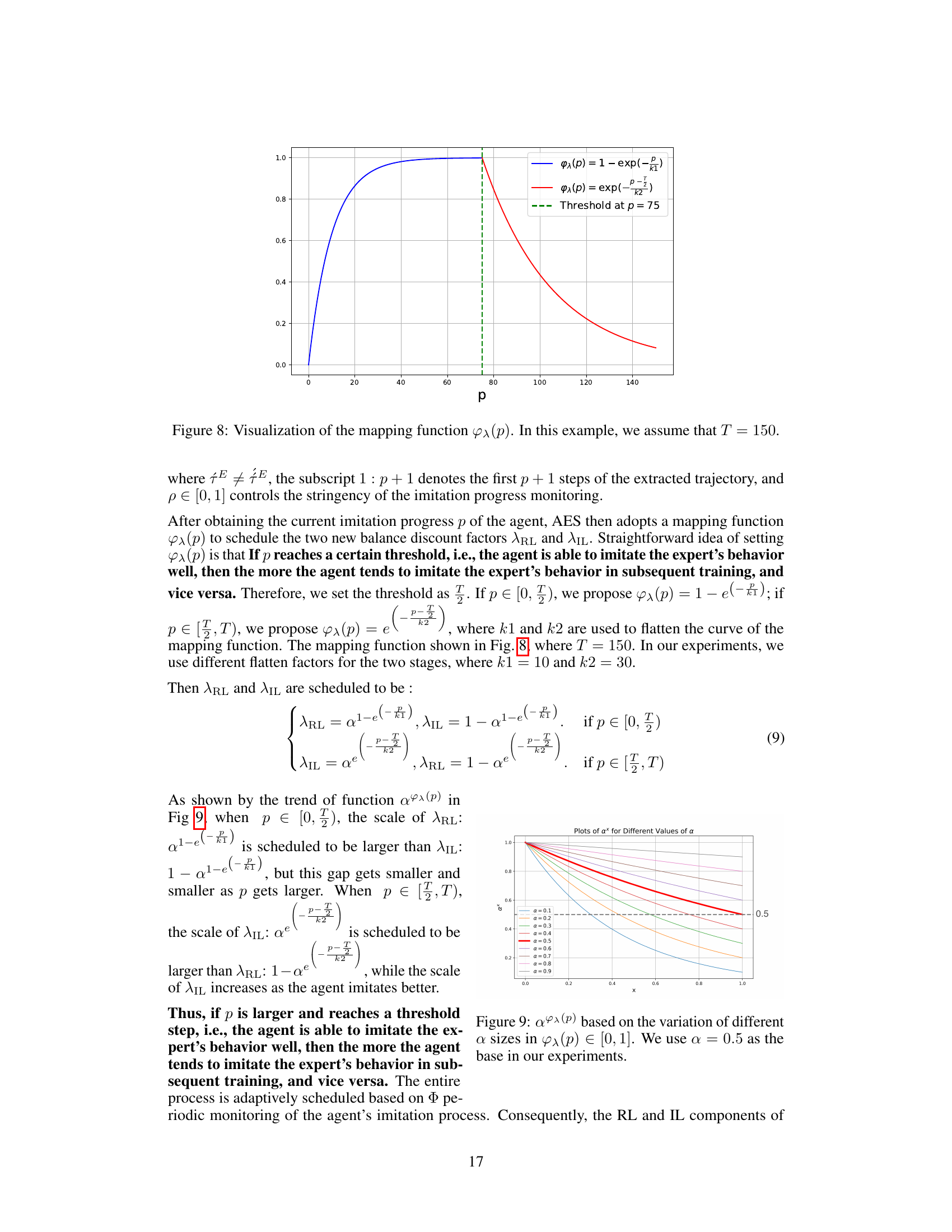

Adaptive Skill Learning#

Adaptive skill learning, in the context of long-horizon robotic manipulation, focuses on dynamically adjusting the learning process to better handle the complexities of diverse and interdependent sub-tasks. It addresses the limitations of traditional methods by balancing reinforcement learning (RL) and imitation learning (IL). The core idea is to leverage environmental feedback and expert demonstrations to guide the robot’s learning. Adaptive equilibrium scheduling (AES) is a crucial component, which dynamically adjusts the weights assigned to RL and IL, allowing the robot to prioritize either exploration or imitation based on its current progress. This adaptive approach is key to achieving robust and stable skill acquisition in challenging, real-world scenarios, making it particularly valuable for tasks that require contact-rich and long-horizon interactions.

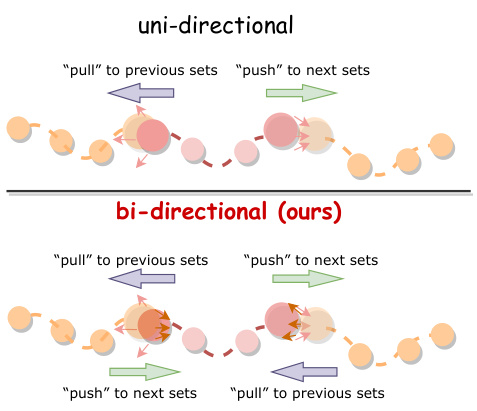

Bi-directional Learning#

Bi-directional learning, in the context of skill chaining for long-horizon robotic manipulation, is a technique to improve the coordination and smoothness of sequential actions. Instead of only considering the transition from one skill’s end state to the next skill’s start state (unidirectional), bi-directional learning considers the influence in both directions. This means that the terminal state of the current skill is guided to align with the initial state of the subsequent skill, and simultaneously the initial state of the subsequent skill is aligned towards the terminal state of the previous skill. This creates a stronger and more robust inter-skill dependency. It helps prevent error accumulation from imperfections in individual skill learning or unexpected disturbances during execution. Dual regularization is a key component. It ensures that this alignment happens not only through the reward function but also through an adversarial training process that strengthens the dependencies between sequential actions and avoids overfitting. Ultimately, this approach leads to more robust and stable long-horizon task completion by effectively managing the transitions between sub-tasks. The experimental results show that this dual regularization significantly improves performance in various long-horizon tasks compared to other methods.

Sim-to-Real Transfer#

Sim-to-real transfer in robotics aims to bridge the gap between simulated and real-world environments. A successful sim-to-real transfer approach reduces the need for extensive real-world data collection and robot interaction, which can be expensive and time-consuming. Domain randomization is a common technique that attempts to create a simulated environment that closely matches the real world by introducing variability in factors like lighting, object properties, and sensor noise. However, perfect sim-to-real transfer is exceptionally challenging, as the complexities of the physical world are often difficult to fully replicate in simulation. Careful consideration of factors that influence the reality gap is paramount, including the choice of simulator, the fidelity of the simulation model, and the selection of appropriate control algorithms. Despite the challenges, sim-to-real transfer holds significant potential for accelerating the development and deployment of robots, enabling faster prototyping and more efficient training of control policies. Careful validation in real-world settings is crucial to evaluate the efficacy of any sim-to-real transfer approach, ensuring that simulated performance translates to reliable real-world performance.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of discussion on future work presents a missed opportunity for insightful exploration. Extending the framework to handle longer-horizon visual manipulation tasks is crucial, suggesting the need for incorporating visual or semantic processing of objects. The current reliance on predefined sub-task divisions is a limitation; a more adaptive system leveraging foundational models or human-in-the-loop learning could address this. Addressing the challenge of smooth task transitions and handling noisy environments is also important; incorporating online reinforcement learning or methods to manage noise might improve the system’s adaptability. Finally, generalizing to real-world robotic scenarios beyond the simulated settings used would greatly enhance the system’s practical value and provide for more robust and transferable results. Investigating the impact of different robot designs and manipulating parameters of the algorithms is a key area to explore in future iterations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

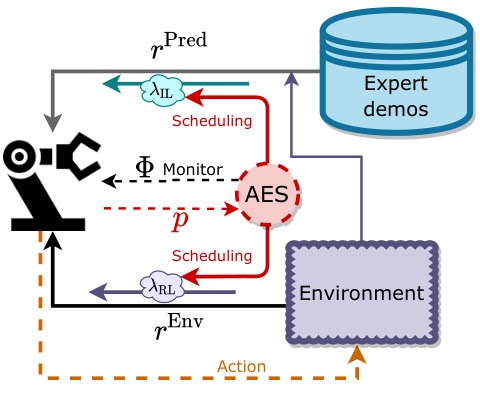

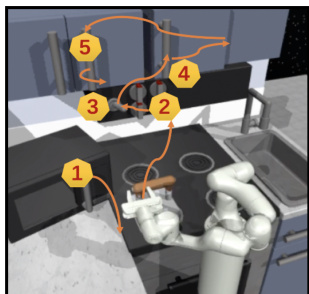

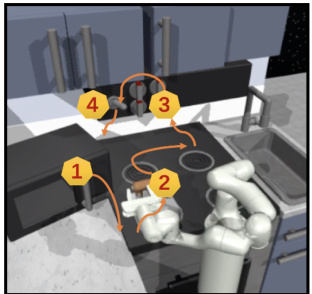

This figure illustrates the pipeline of the Skill Chaining via Dual Regularization (SCaR) framework. It shows the two main phases: (1) Adaptive Sub-task Skill Learning, which uses environmental feedback and expert demonstrations, combined with adaptive equilibrium scheduling (AES) to balance learning and improve both intra-skill (within a sub-task) and inter-skill (between sub-tasks) dependencies, and (2) Bi-directional Adversarial Learning, which further refines the skills using bi-directional discriminators to ensure smooth transitions between sub-tasks. The right side shows the evaluation process.

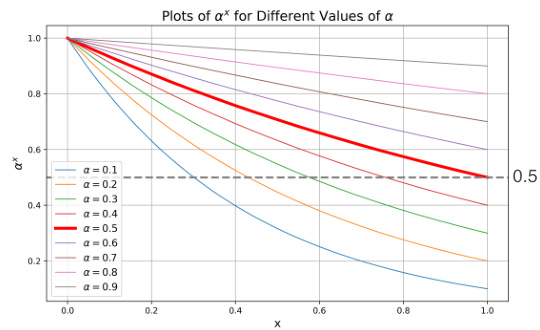

This figure illustrates the Adaptive Equilibrium Scheduling (AES) regularization mechanism used in the sub-task skill learning phase of the SCaR framework. The AES module dynamically adjusts the balance between reinforcement learning (RL) from environmental feedback (rEnv) and imitation learning (IL) from expert demonstrations (rPred). The imitation progress monitor (Φ) tracks the agent’s imitation performance, and based on this feedback, the AES module updates the balance factors (ARL and λIL) to guide the learning process. This adaptive scheduling ensures that the agent effectively balances exploration from the environment and imitation from the expert, resulting in more stable and robust sub-task skill learning.

This figure illustrates the difference between uni-directional and bi-directional regularization in sub-task skill chaining. Uni-directional regularization only considers either the influence of the previous skill’s terminal state on the current skill’s initial state (pull) or the influence of the current skill’s terminal state on the next skill’s initial state (push). Bi-directional regularization, however, considers both influences simultaneously, creating a more robust and coordinated chaining process. This results in a smoother and more stable transition between sequential skills in long-horizon tasks.

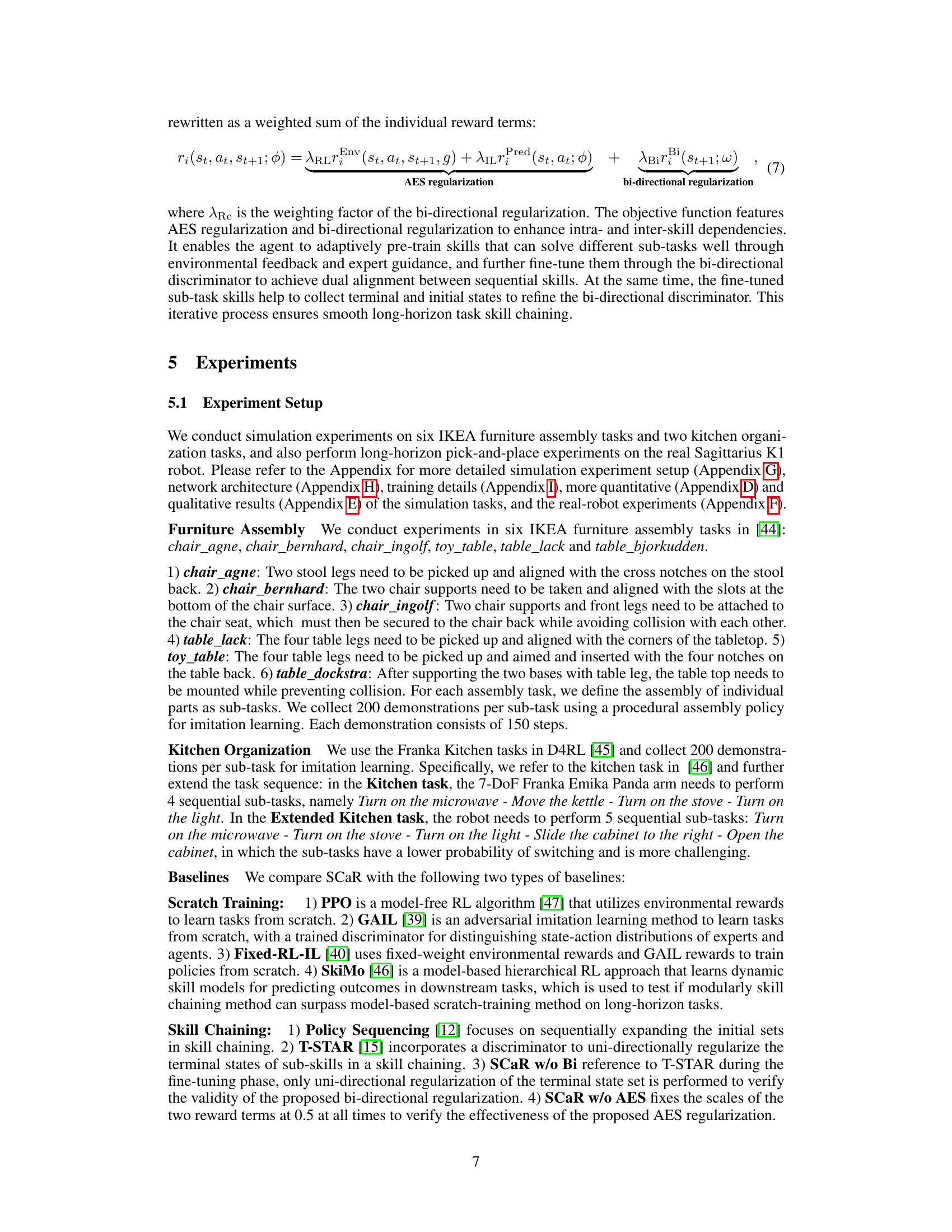

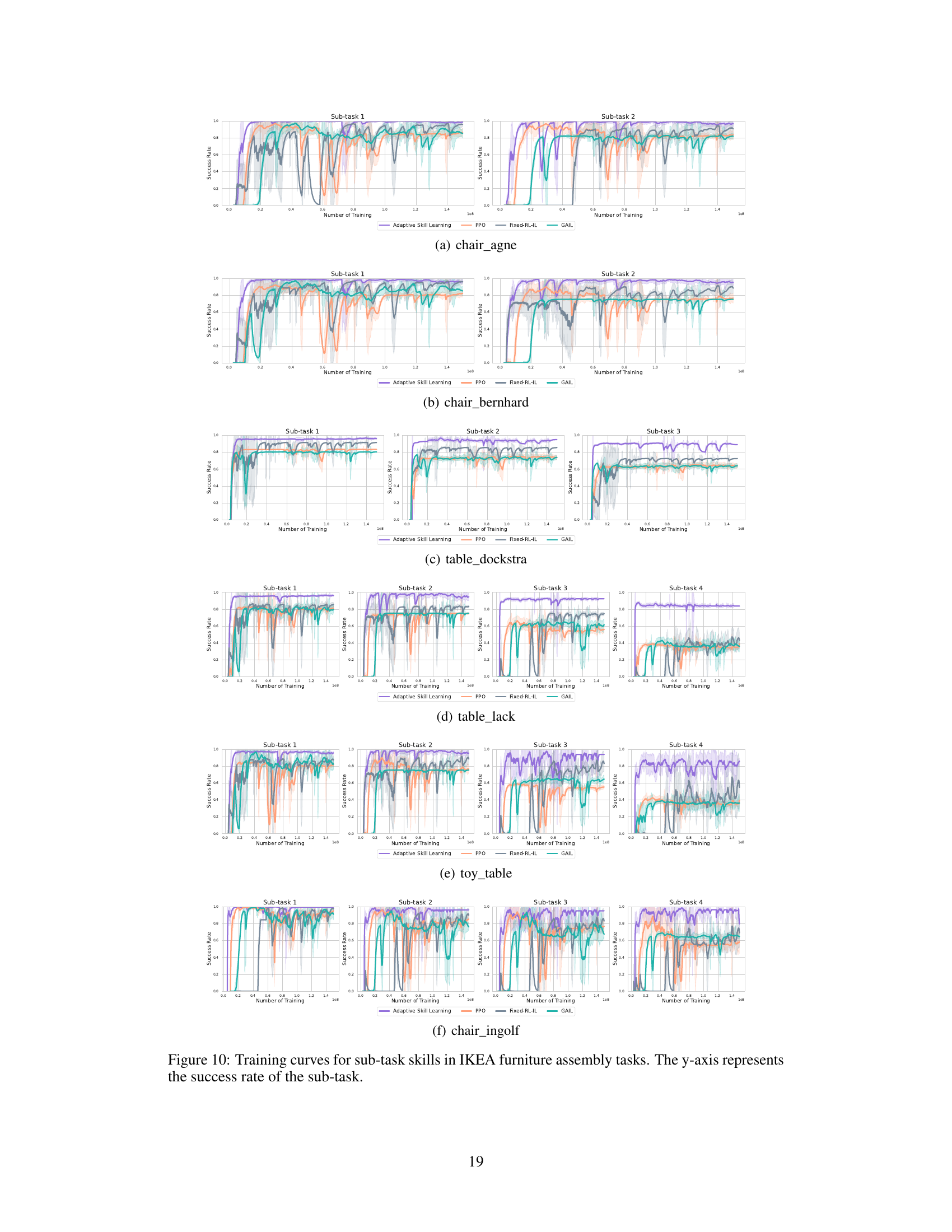

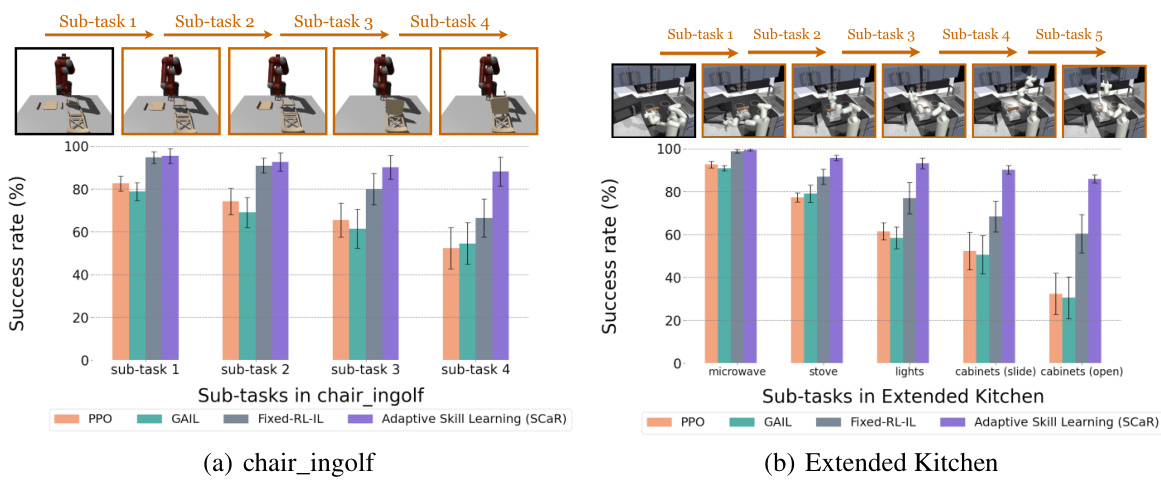

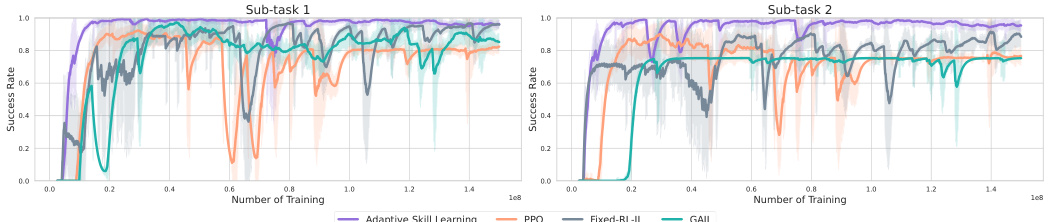

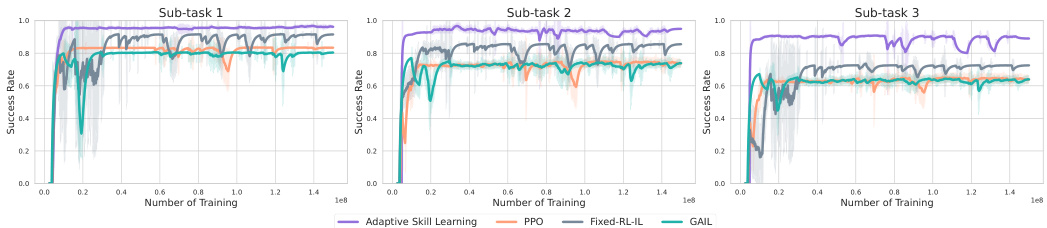

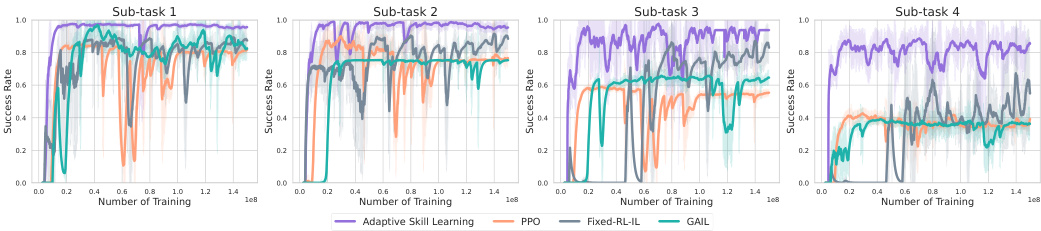

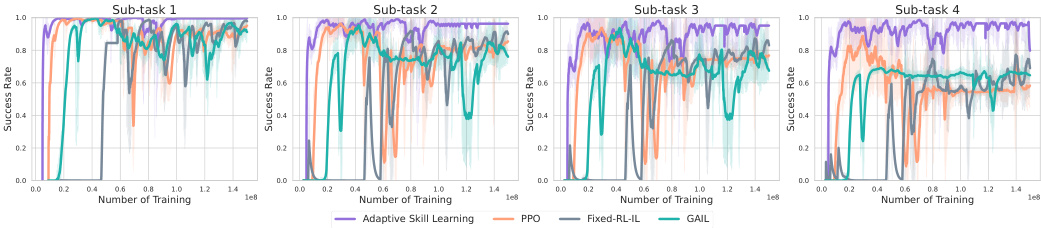

This figure presents a comparative analysis of sub-task skill learning performance across different methods. It shows success rates for individual sub-tasks within two complex tasks: assembling the chair_ingolf (a) and completing the Extended Kitchen (b) tasks. The results illustrate the relative effectiveness of different approaches, including PPO, GAIL, Fixed-RL-IL, and the proposed Adaptive Skill Learning (SCaR) method, in achieving successful sub-task completion.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the proposed Skill Chaining via Dual Regularization (SCaR) method and the T-STAR method for long-horizon robotic manipulation. It presents visual examples of successful stool assembly using SCaR, contrasting with failed attempts using T-STAR. The images illustrate the step-by-step progress in each attempt, highlighting the stability and smoothness achieved by SCaR compared to the instability and failures observed in T-STAR.

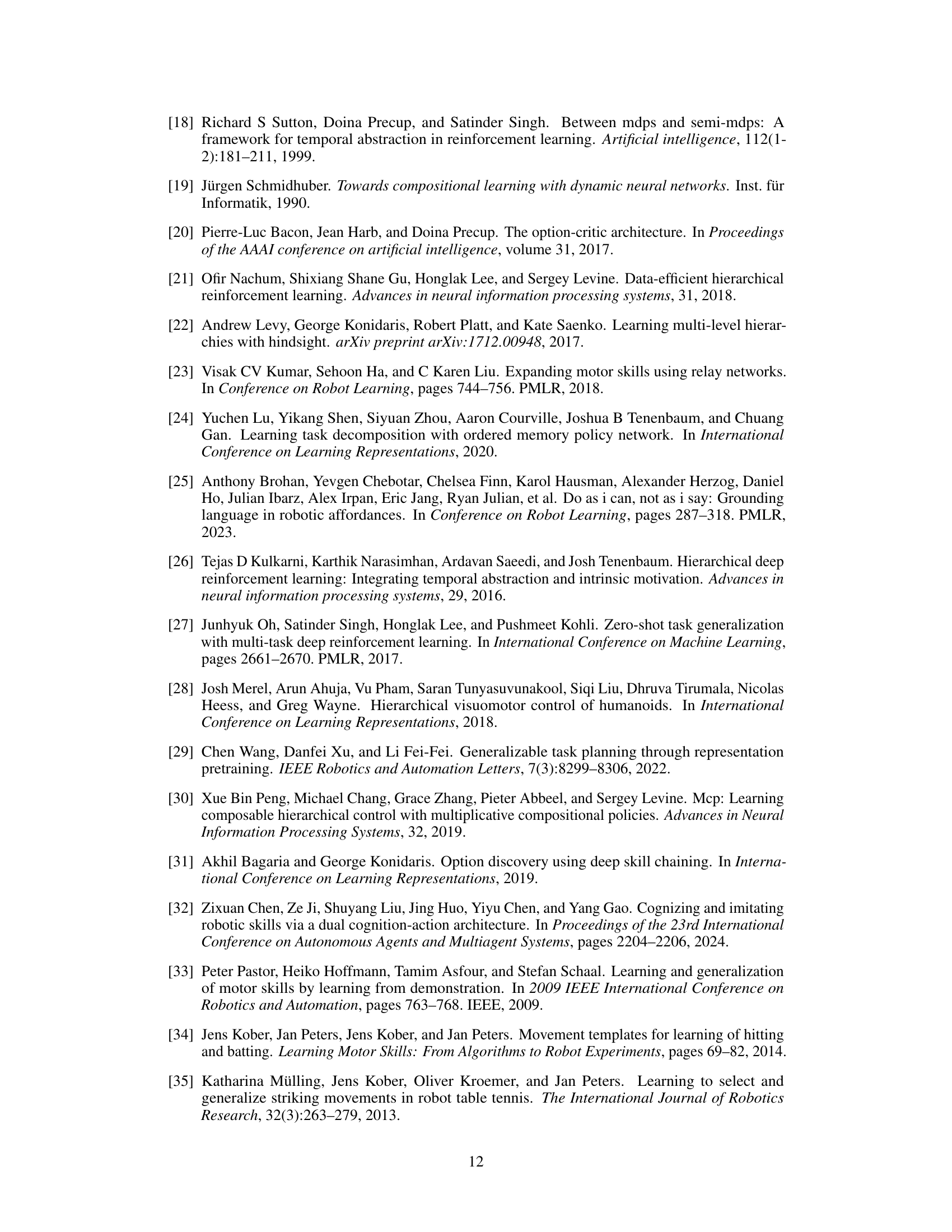

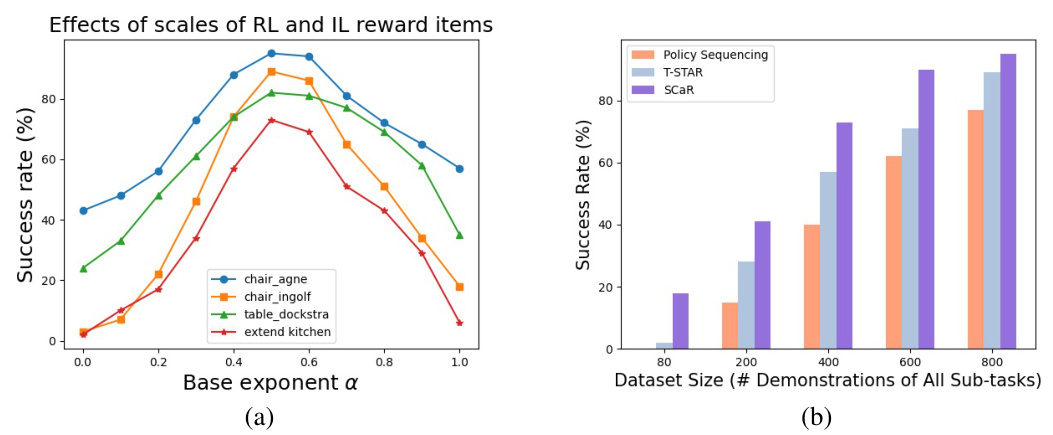

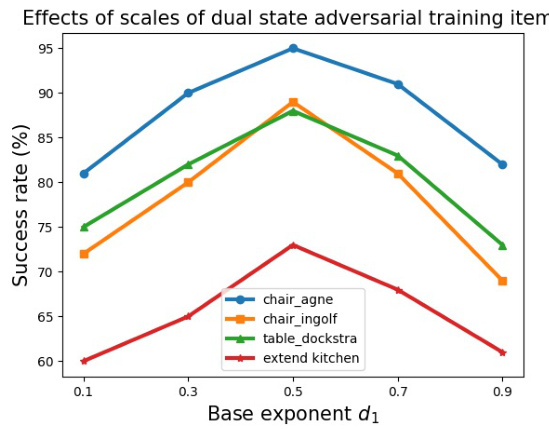

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted to investigate the impact of key factors on the performance of the SCaR framework. Panel (a) shows how varying the base exponent α (which balances the relative weights of RL and IL reward terms in sub-task skill learning) affects task success rates across four different tasks (chair_agne, chair_ingolf, table_dockstra, and extend_kitchen). Panel (b) illustrates the relationship between the size of the expert demonstration dataset and the success rate of the task for three different methods (Policy Sequencing, T-STAR, and SCaR).

This figure illustrates how the imitation progress is measured by calculating the longest increasing subsequence (LIS) in a sequence Q. The sequence Q is constructed by finding the nearest neighbor of each state in the agent’s trajectory to the expert’s trajectory using cosine similarity. (a) shows a scenario where the agent’s trajectory closely matches the expert’s trajectory, resulting in a strictly increasing sequence Q. (b) shows a scenario where there is less alignment, resulting in a non-strictly increasing sequence Q. The length of the LIS is used as a measure of imitation progress; a longer LIS indicates better imitation.

The figure shows the mapping function φλ(p) used in the Adaptive Equilibrium Scheduling (AES) to balance the RL and IL components of sub-task skill learning. The x-axis represents the imitation progress p, which is a measure of how well the agent imitates expert demonstrations. The y-axis represents the weight assigned to RL and IL in the reward function. The function is divided into two parts. When p is below 75, the function increases exponentially, favoring imitation learning (IL). When p is above 75, the function decreases exponentially, favoring reinforcement learning (RL). The threshold p = 75 represents a balance point between RL and IL.

This figure shows the success rates of different methods for learning sub-task skills in two example tasks: assembling the chair_ingolf (a) and the extended kitchen task (b). Each bar represents the average success rate over multiple trials. The results demonstrate that the proposed adaptive skill learning method (SCaR) significantly outperforms the baseline methods (PPO, GAIL, Fixed-RL-IL) in terms of achieving high success rates on all subtasks.

This figure shows the success rates of different methods for sub-task skill learning in two tasks: (a) chair_ingolf (IKEA furniture assembly) with 4 sub-tasks and (b) Extended Kitchen with 5 sub-tasks. The x-axis represents the sub-task number, while the y-axis indicates the success rate. Adaptive Skill Learning (SCaR) consistently maintains high success rates across all sub-tasks, while other methods, such as PPO, GAIL, and Fixed-RL-IL, show declining performance as the number of sub-tasks increases.

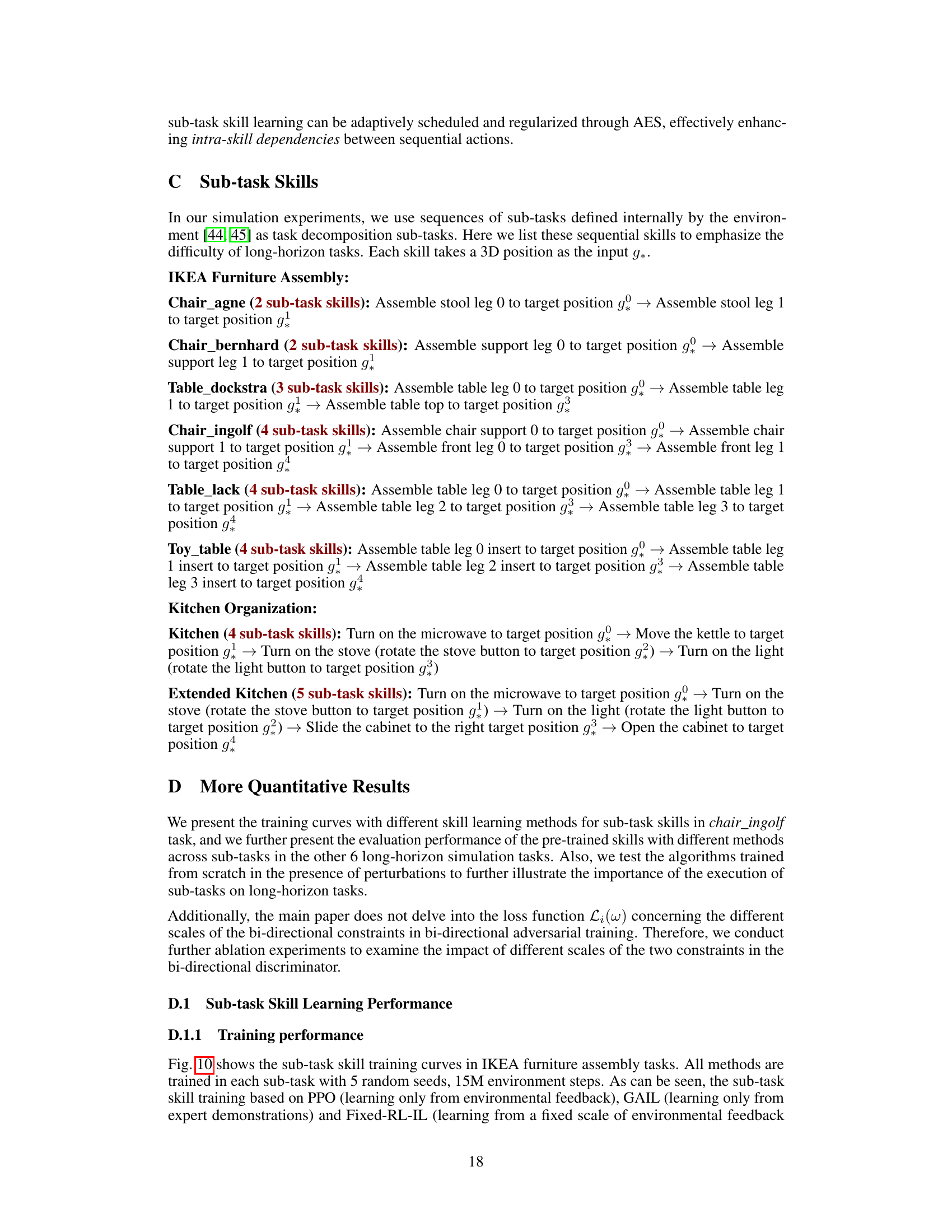

This figure shows the training performance curves for various methods across different sub-tasks in six IKEA furniture assembly tasks. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis shows the success rate achieved. The curves illustrate the performance of different learning approaches, including Adaptive Skill Learning, PPO, Fixed-RL-IL, and GAIL. This visualization helps to compare how these different methods converge during training for each individual sub-task. The shaded areas represent the standard deviation across multiple training runs for each method.

This figure displays the training curves for different methods in learning sub-task skills for six IKEA furniture assembly tasks. The y-axis represents the success rate of each sub-task, and the x-axis shows the number of training steps. The methods compared include Adaptive Skill Learning (the proposed method), PPO, Fixed-RL-IL, and GAIL. Each line represents the average success rate across five random seeds. The figure aims to demonstrate that the Adaptive Skill Learning method consistently achieves higher and more stable success rates compared to baseline methods.

This figure shows the training curves for the sub-task skills across six different IKEA furniture assembly tasks. The training curves illustrate the success rate of each sub-task skill over the course of training, using four different methods: Adaptive Skill Learning, PPO, Fixed-RL-IL and GAIL. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis represents the success rate, which is a value between 0 and 1.

This figure displays the training curves for sub-task skills across various methods in the IKEA furniture assembly tasks. The y-axis represents the success rate achieved by each method in each sub-task, while the x-axis shows the number of training steps. The different colored lines represent different learning methods: Adaptive Skill Learning, PPO, Fixed-RL-IL, and GAIL. The figure is broken into four sub-figures, one for each sub-task, allowing for a comparison of the learning performance of each method across each step of the overall task.

This figure shows the training performance curves for different sub-task skills in six IKEA furniture assembly tasks. The x-axis represents the number of training steps, and the y-axis represents the success rate achieved during training. Multiple lines are shown for each subtask, representing different training methods: Adaptive Skill Learning (the proposed method), PPO, Fixed-RL-IL, and GAIL. The figure allows a comparison of the training efficiency and effectiveness of these different approaches for achieving high success rates in the sub-tasks.

This figure shows the success rates of different methods in learning sub-task skills for two example tasks: (a) shows the results for the chair_ingolf task from IKEA furniture assembly, which has four sub-tasks. (b) shows the results for the Extended Kitchen task, which has five sub-tasks. The results demonstrate that the proposed adaptive skill learning method (SCaR) consistently achieves high success rates across all sub-tasks, outperforming baseline methods (PPO, GAIL, Fixed-RL-IL) which struggle to maintain high success rates as the number of sub-tasks increases. This highlights the effectiveness of SCaR’s approach in learning robust and stable sub-task skills.

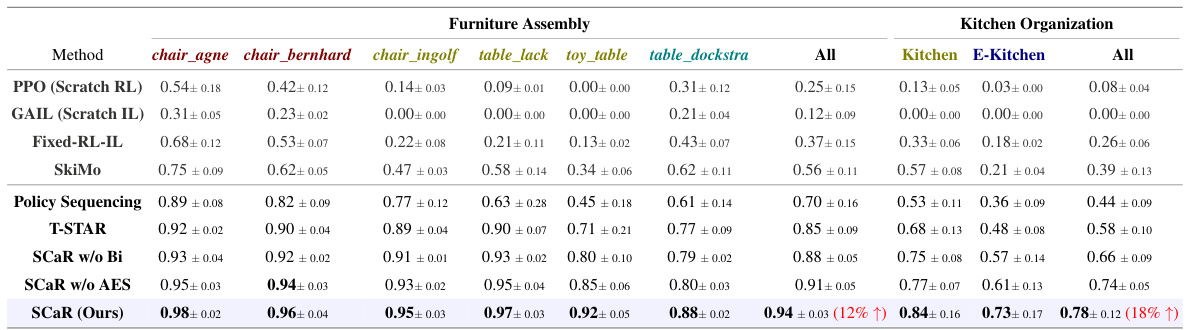

This figure shows the ablation study on the impact of different scales of bi-directional constraints (C1 and C2) in the SCaR framework on skill chaining performance. The x-axis represents the base exponent d1, which determines the scales of the two constraints. The y-axis represents the success rate (%). The results show that when the scales of the two constraints are balanced (around d1 = 0.5), the skill chaining performance is best for most tasks. As the scales become more imbalanced (d1 approaches 0.1 or 0.9), the performance decreases, suggesting the importance of balancing the dual constraints for robust and effective skill chaining.

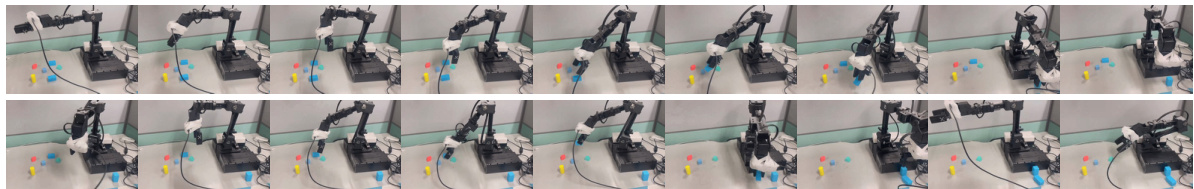

This figure shows a visual comparison of the proposed Skill Chaining via Dual Regularization (SCaR) method and T-STAR on a stool assembly task. The top row displays SCaR successfully completing the task. The bottom row shows T-STAR failing to do so. The images illustrate the state of the robot and stool at different points in each method’s execution. This illustrates SCaR’s enhanced robustness and smoother skill chaining compared to T-STAR.

This figure showcases a qualitative comparison of the proposed SCaR method and the T-STAR baseline, highlighting the superior performance of SCaR in successful skill chaining. It visually demonstrates the differences in the robot’s actions (and their success or failure) during the task execution, primarily focusing on the smoothness and stability. More detailed qualitative results are available on the project website.

This figure showcases a qualitative comparison of the proposed SCaR method and the T-STAR baseline for long-horizon robotic manipulation tasks. It visually demonstrates the improved performance of SCaR in successfully executing sequential sub-tasks, while T-STAR encounters failures due to the accumulation of errors in the process. The images highlight the smoother and more stable execution achieved by SCaR compared to T-STAR.

This figure shows the six different IKEA furniture assembly environments used in the experiments of the paper. Each environment shows a different furniture piece (chair_agne, chair_bernhard, chair_ingolf, table_lack, toy_table, and table_dockstra) with its components scattered on a table. A robotic arm is also present in each environment, indicating the robotic manipulation tasks involved.

This figure illustrates the challenges of skill chaining in long-horizon robotic manipulation tasks and introduces the proposed Skill Chaining via Dual Regularization (SCaR) framework. It shows three scenarios: (a) Failure during the pre-training of sub-task skills due to insufficient intra-skill dependencies, (b) Failure during skill chaining caused by external disturbances affecting inter-skill dependencies, and (c) Successful skill chaining using the SCaR framework which effectively addresses both intra- and inter-skill dependencies, leading to stable and smooth stool assembly. The figure uses a stool assembly task as a visual example to highlight the advantages of SCaR over traditional methods.

This figure illustrates the challenges of skill chaining in long-horizon robotic manipulation and introduces the motivation behind the proposed method, SCaR. It shows three scenarios: (a) Failed Pre-training of Sub-task Skills: Demonstrates that insufficient training of individual sub-tasks (assembling stool legs) leads to failures. (b) Failed Skill Chaining due to Disturbance: Shows how external disturbances during execution can cause a chain of failures, even if individual skills are well-trained. (c) Skill Chaining via Dual Regularization (SCaR): Highlights the success of the proposed SCaR framework in ensuring stable and smooth skill chaining despite potential errors or disturbances. It achieves this by improving intra-skill and inter-skill dependencies. The example used is a stool assembly task.

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods’ performance on eight long-horizon robotic manipulation tasks. The tasks include IKEA furniture assembly tasks and kitchen organization tasks, with varying numbers of sub-tasks. The table shows the average success rate (with standard deviation) for each method on each task. A higher success rate indicates better performance in completing the long-horizon tasks.

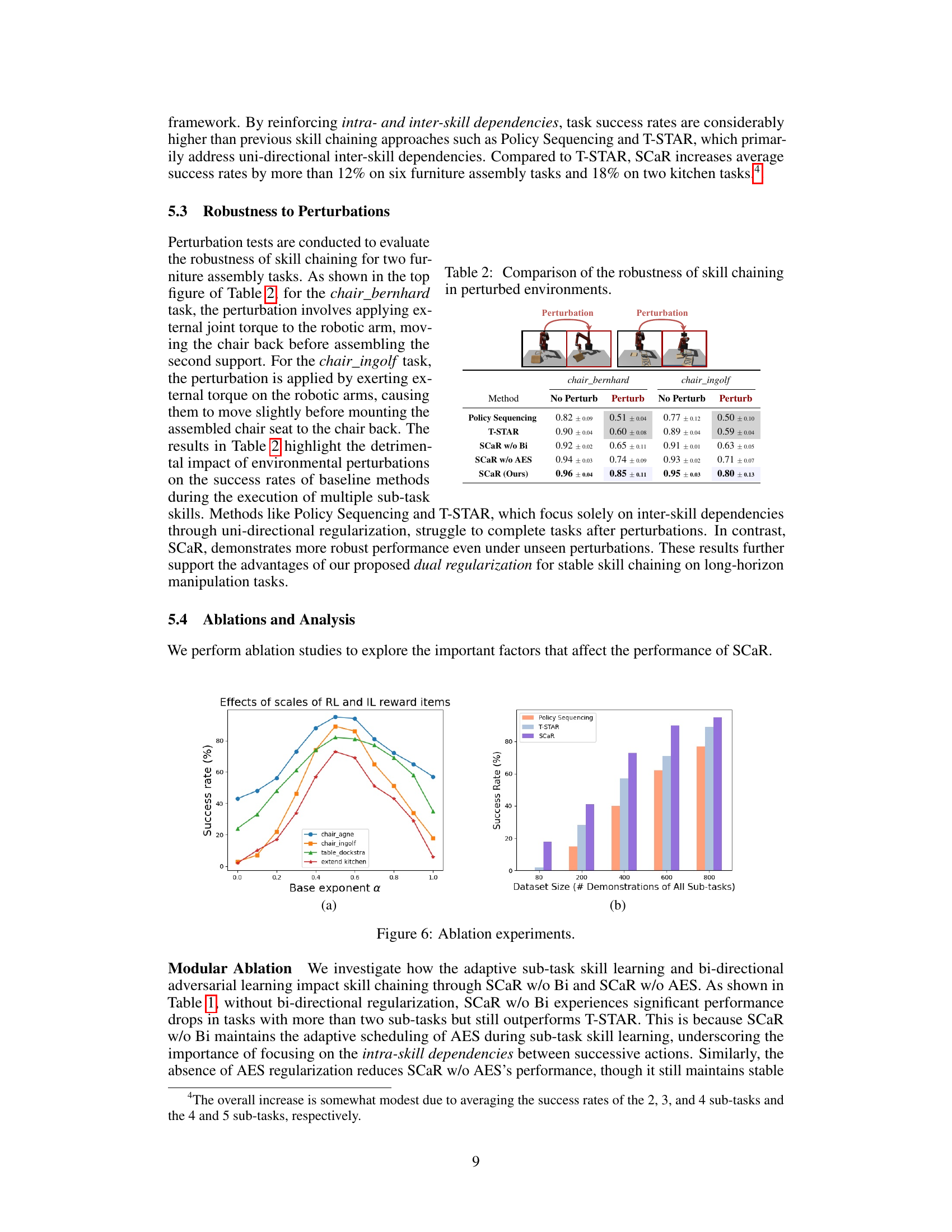

This table compares the success rates of different skill chaining methods (Policy Sequencing, T-STAR, SCaR variants) on two furniture assembly tasks (chair_bernhard and chair_ingolf) under both stationary and perturbed conditions. The perturbation involves applying external torque to the robot arm during task execution. The results show how well each method maintains performance in the face of unexpected disturbances.

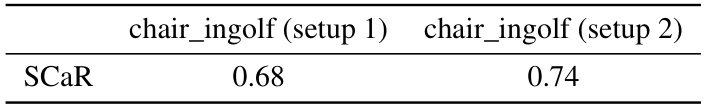

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to investigate how different sub-task divisions affect the performance of the SCaR model. Two different setups are evaluated for the chair_ingolf task: setup 1 combines two sub-tasks and setup 2 combines two other sub-tasks. The results show the success rate of the SCaR model in each setup. The study aims to determine the impact of sub-task granularity on the SCaR’s overall success rate.

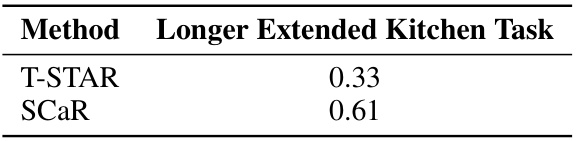

This table compares the performance of T-STAR and SCaR on the Longer Extended Kitchen task, which involves six sequential sub-tasks. The results show that SCaR achieves a significantly higher success rate than T-STAR, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling more complex, long-horizon manipulation tasks.

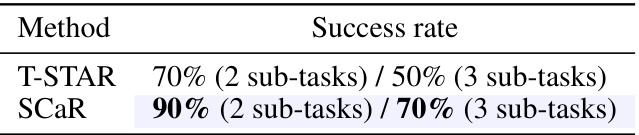

This table presents the success rates achieved by T-STAR and SCaR on real-world long-horizon robotic manipulation tasks involving pick-and-place operations with 2 and 3 blue squares. The success rates reflect the percentage of successful task completions out of multiple trials.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the performance of different methods (including the proposed SCaR and baselines) on various long-horizon robotic manipulation tasks. The performance is measured by the success rate of completing all sub-tasks within each task. The table highlights the varying complexity of the tasks by showing different numbers of sub-tasks and the progress rate for each sub-task, making it easier to interpret the results.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods’ performance on eight long-horizon robotic manipulation tasks. The tasks include IKEA furniture assembly and kitchen organization tasks, varying in the number of sub-tasks (2, 3, 4, or 5). The success rate is shown for each method, reflecting the average completion progress across multiple trials and random seeds. The table highlights the differences in performance and success rates across various approaches, reflecting factors such as the number of sub-tasks, method type (scratch RL, scratch IL, skill chaining, etc.), and the impact of dual regularization strategies.

Full paper#