↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Neural Functional Networks (NFNs) show promise in various applications, but existing designs often overlook crucial weight scaling and sign-flipping symmetries present in ReLU and sin/tanh networks, respectively. This limitation leads to inefficient models with numerous trainable parameters. Furthermore, existing NFNs primarily focus on permutation symmetries, neglecting other significant weight space symmetries.

This paper introduces Monomial-NFNs, a novel family of NFNs that address these limitations. By incorporating both permutation and scaling/sign-flipping symmetries through equivariant and invariant layers, Monomial-NFNs achieve significantly improved efficiency. The authors theoretically prove that the symmetries exploited are maximal for fully connected and convolutional networks, and empirically demonstrate Monomial-NFNs’ competitive performance and efficiency on several tasks, including predicting network generalization and classifying implicit neural representations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with neural functional networks (NFNs). It significantly improves NFN efficiency by incorporating weight scaling and sign-flipping symmetries, previously ignored. This opens new avenues for building more efficient and generalizable NFNs for various deep learning applications, especially those dealing with large-scale networks. The theoretical grounding provided further solidifies its significance in the field.

Visual Insights#

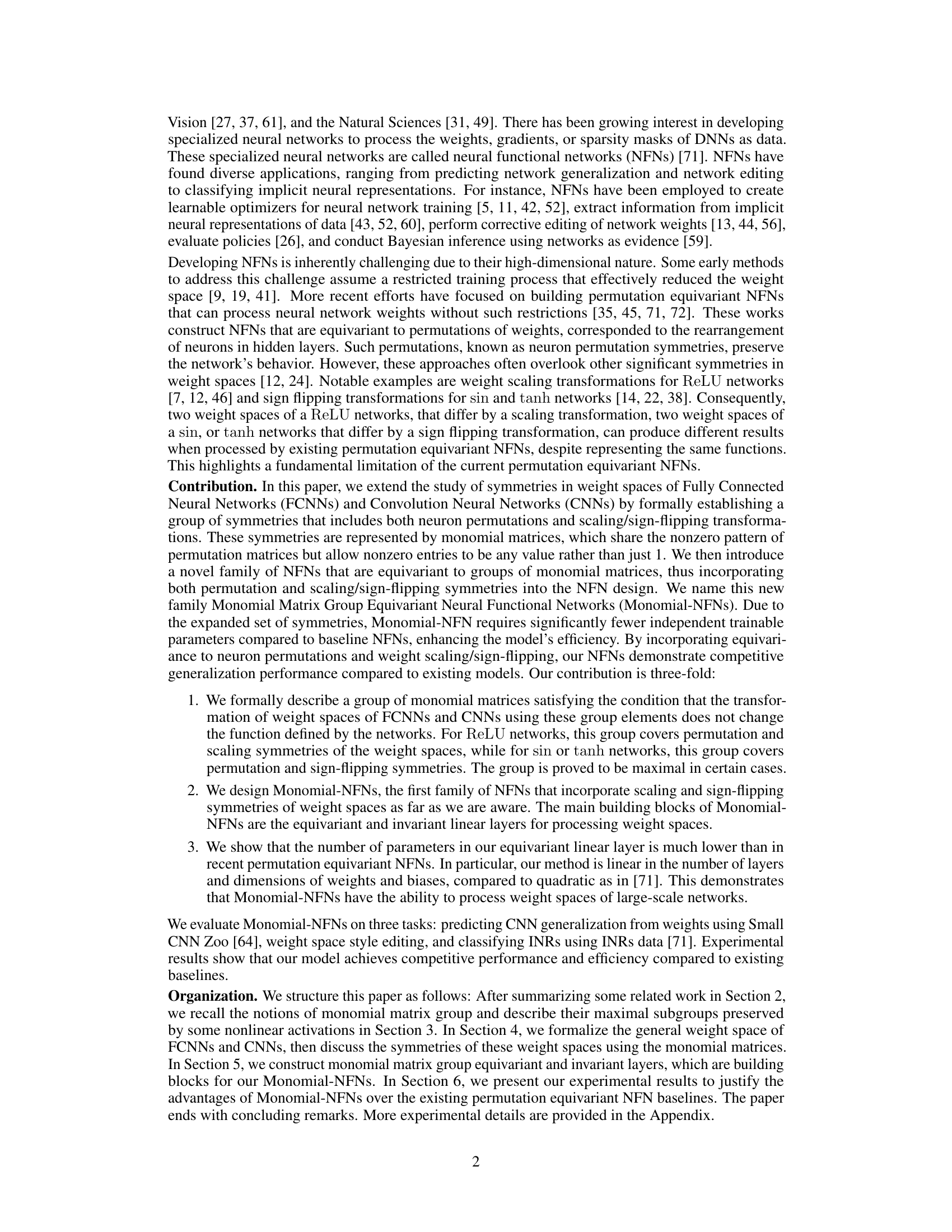

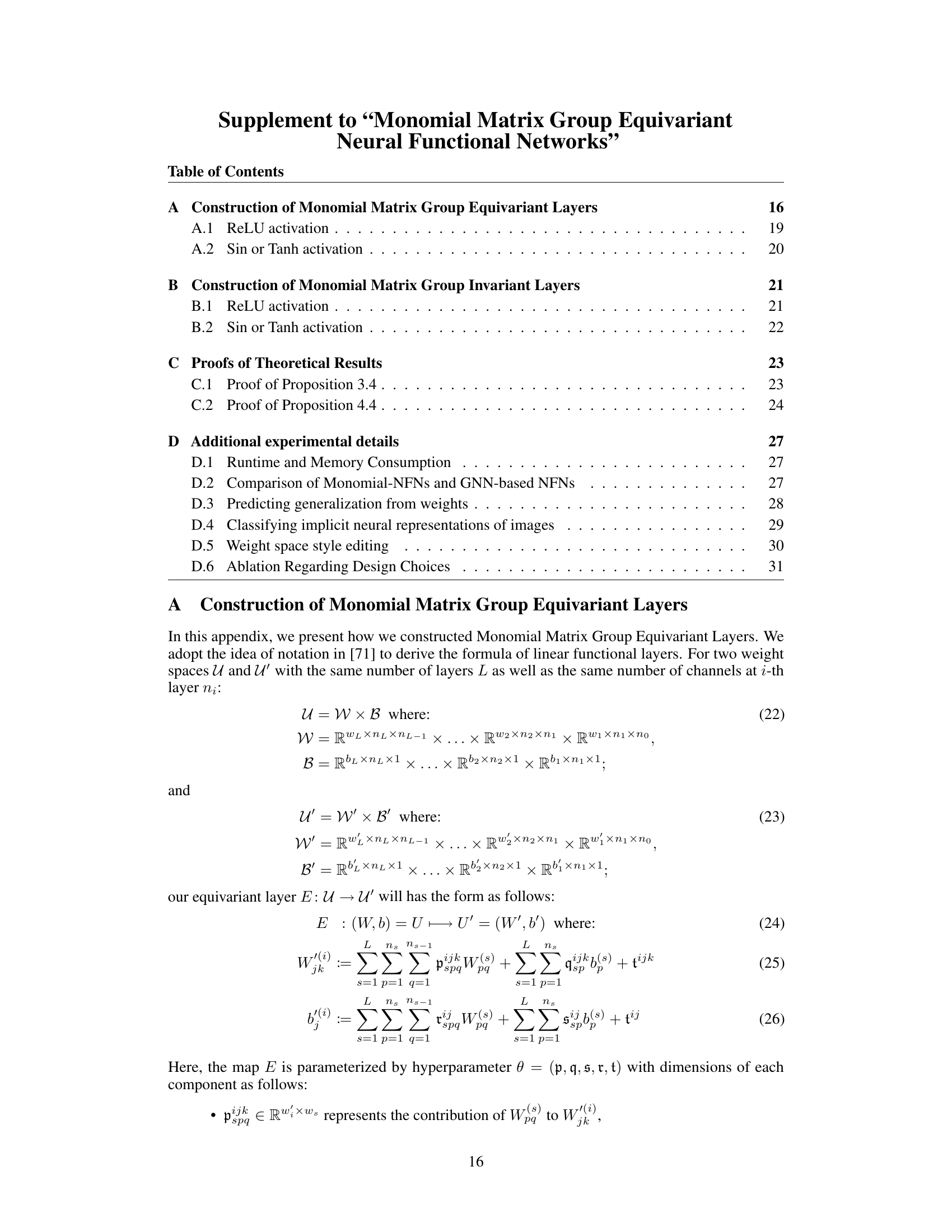

This figure shows the performance of Monomial-NFN and other baseline models (NP, HNP, and STATNN) on the task of predicting CNN generalization using the ReLU subset of the Small CNN Zoo dataset. The x-axis represents the upper bound of scaling augmentation applied to the weights (log scale), and the y-axis represents Kendall’s Tau correlation, a measure of rank correlation between predicted and actual generalization performance. The figure demonstrates that the Monomial-NFN model maintains relatively stable performance across different levels of augmentation, while the other models show a significant drop in performance with increased augmentation.

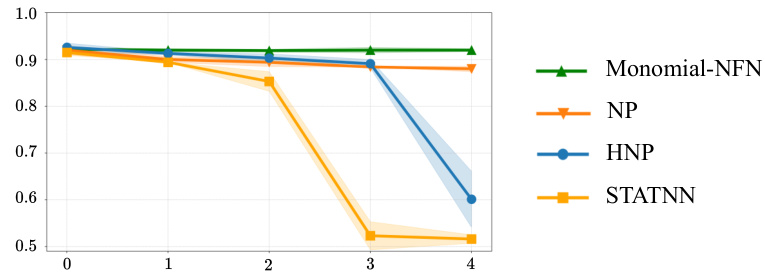

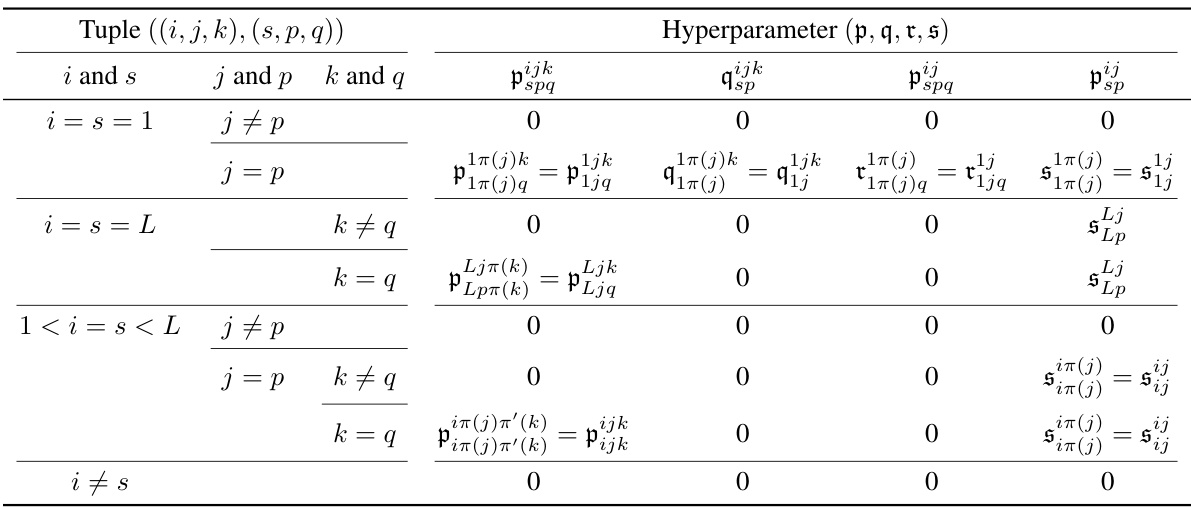

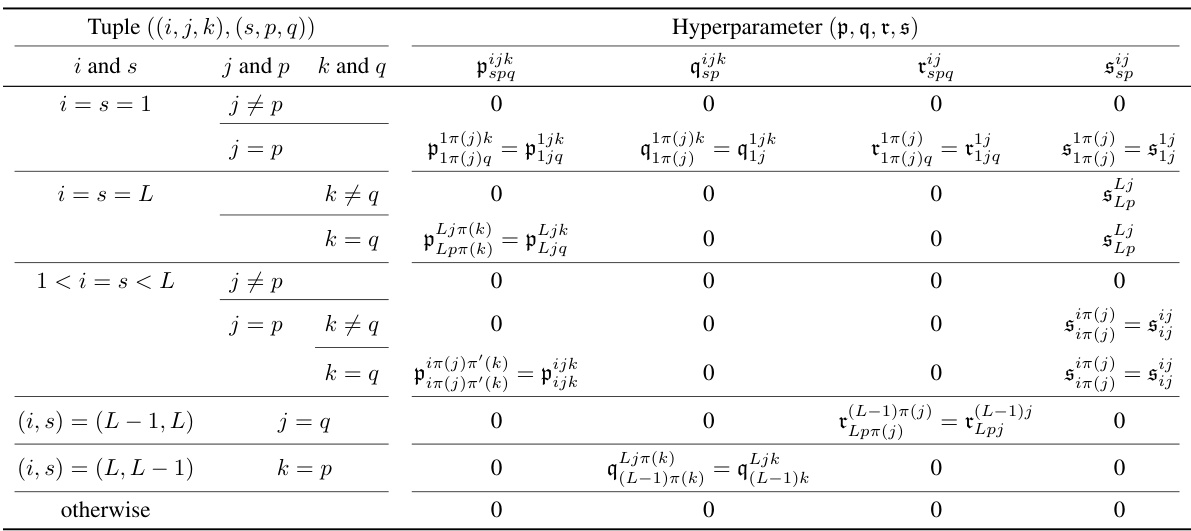

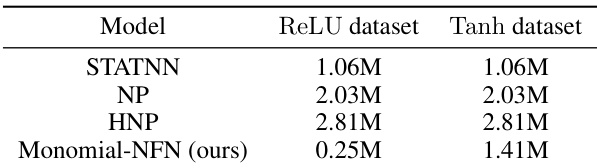

This table compares the number of parameters required for a linear equivariant layer in neural functional networks when using different subgroups of the monomial matrix group. It shows that using the full monomial matrix group (ours), which incorporates scaling and sign-flipping symmetries in addition to permutations, significantly reduces the number of parameters compared to methods that only consider permutation symmetries ([71]). The notation ‘O(…)’ indicates the order of complexity.

In-depth insights#

NFN Symmetries#

Neural Functional Networks (NFNs) leverage the inherent symmetries within deep neural network weight spaces to enhance efficiency and generalization. A core concept is the exploitation of permutation symmetries, arising from the order-invariance of neurons within layers. However, the paper argues that focusing solely on permutation symmetries is limiting. It introduces the novel concept of incorporating scaling and sign-flipping symmetries prevalent in activation functions like ReLU and tanh, respectively. This leads to a more comprehensive understanding of NFN symmetries, represented by the Monomial Matrix Group. This broader perspective significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters, leading to improved efficiency. The theoretical foundation demonstrates that the identified symmetries are maximal for specific activation functions, making the approach rigorous. Empirical results showcase the advantages of considering these expanded symmetries over traditional permutation-based methods, highlighting the improved model performance and generalization capability of the proposed Monomial-NFN architecture.

Monomial-NFNs#

The proposed Monomial-NFNs architecture presents a significant advancement in Neural Functional Networks (NFNs) by addressing limitations of previous permutation-equivariant models. Monomial-NFNs explicitly incorporate scaling and sign-flipping symmetries alongside permutation symmetries, leading to a more comprehensive representation of weight spaces in deep neural networks. This results in fewer trainable parameters and potentially improved efficiency, as confirmed by the experimental results. The theoretical grounding, demonstrating the maximality of the monomial matrix group under certain conditions, strengthens the approach. However, future exploration is needed to investigate the maximality of the group in all cases and further analyze the impact of the activation function on the group’s properties. Moreover, the generalizability and scalability of the model to diverse architectures and datasets warrant further investigation. Despite this, the core idea of enhancing symmetry considerations in NFNs is a promising direction for future research.

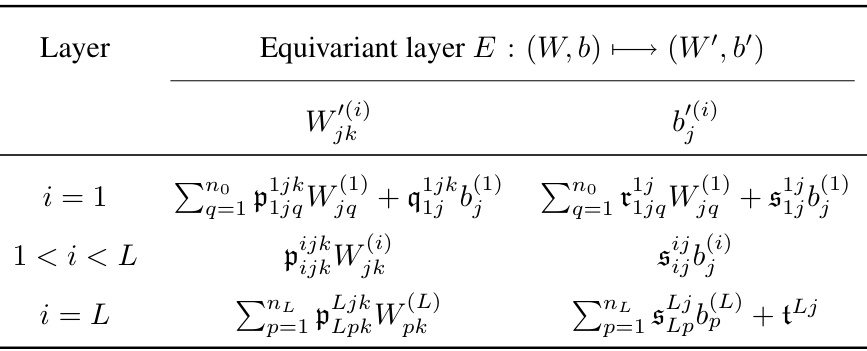

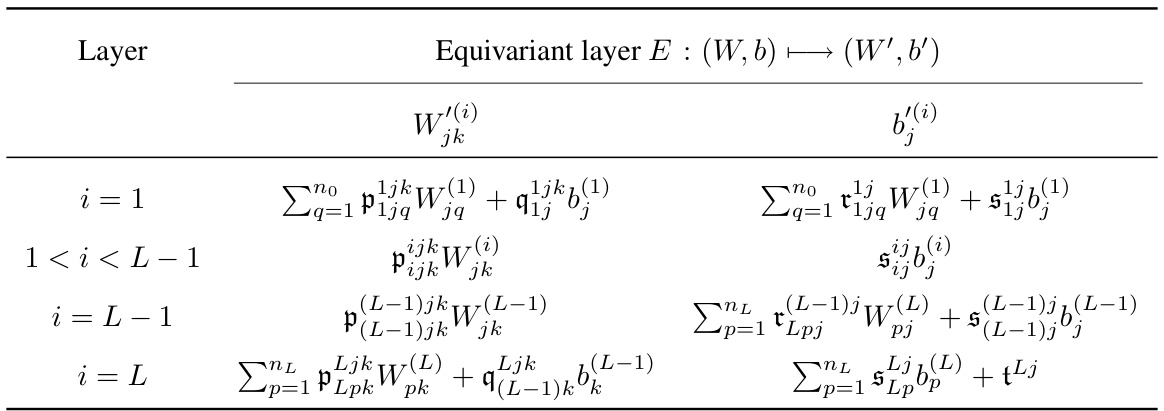

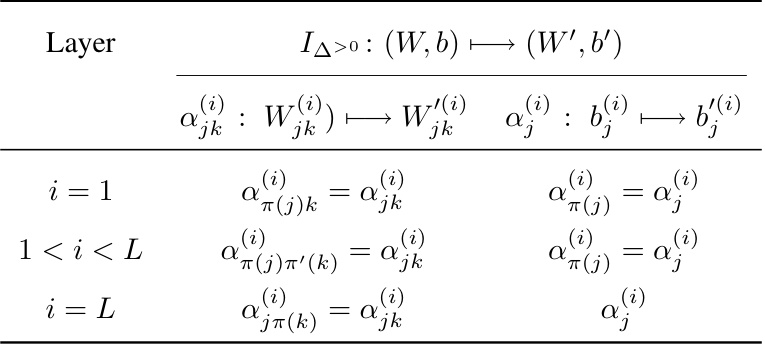

Equivariant Layers#

The concept of “Equivariant Layers” in the context of neural networks signifies a crucial advancement in building models that are robust to various transformations of their input data. These layers are designed to maintain a specific relationship between the input and output representations when subjected to group actions, like rotations or permutations. This equivariance property is a significant advantage because it reduces the number of trainable parameters and improves generalization, particularly when dealing with symmetries in the data. The creation of these layers involves carefully crafting the layer’s weights and biases such that the output transformation mirrors the input transformation, ensuring consistent results across different perspectives. This technique is especially beneficial when dealing with data like images or graphs where symmetries are prevalent. The authors likely demonstrate the practical implications of equivariant layers by comparing them to traditional layers on a benchmark, showing enhanced performance, such as higher accuracy with fewer parameters. A key challenge in designing equivariant layers lies in efficiently encoding the group actions and ensuring computational feasibility. The paper’s contribution likely includes the novel architecture of these layers and a theoretical justification of their properties.

Experimental Results#

The “Experimental Results” section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims made in the introduction and theoretical sections. A strong “Experimental Results” section will demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed methodology, typically through quantitative metrics and comparisons against existing state-of-the-art approaches. Clear visualization of results, such as graphs and tables, is essential for easy interpretation. The experimental setup, including datasets, hyperparameters and evaluation protocols, should be meticulously documented to ensure reproducibility. Any limitations or unexpected findings should be transparently discussed, enhancing the paper’s credibility. A thoughtful analysis of the results, going beyond simple reporting of numbers, is vital to draw meaningful conclusions and contribute to the broader field. A robust experimental design and rigorous statistical analysis strengthens the overall impact and trustworthiness of the research. The inclusion of both successful and less-successful experiments contributes to a more balanced and insightful analysis. The discussion of these results should tie back directly to the claims presented in the introduction, demonstrating clear evidence of progress and validation.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on Monomial Matrix Group Equivariant Neural Functional Networks could explore expanding the types of symmetries considered beyond scaling and sign-flipping, potentially encompassing other transformations that leave network behavior invariant. Investigating the maximal subgroups preserved by different activation functions beyond ReLU, sin, and tanh would enhance the theoretical understanding. Empirically, extending the applications of Monomial-NFNs to larger-scale networks and more complex tasks is crucial to solidify their practical impact. A key area is developing more sophisticated invariant and equivariant layers, possibly incorporating techniques from other fields like group theory and representation theory to further enhance efficiency and expressivity. Finally, a detailed investigation into the model’s robustness to various types of noise and adversarial attacks would be valuable, along with clarifying the model’s generalization capabilities to unseen data distributions.

More visual insights#

More on tables

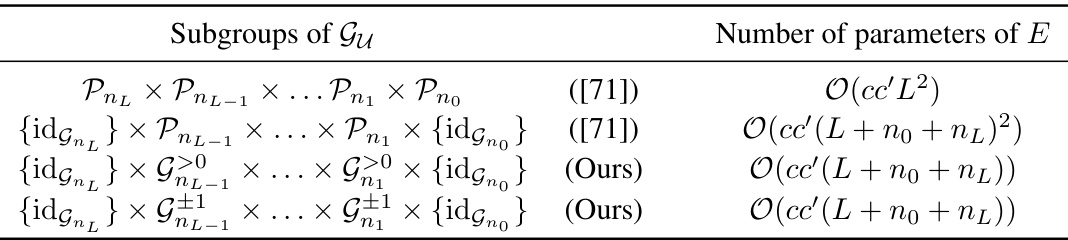

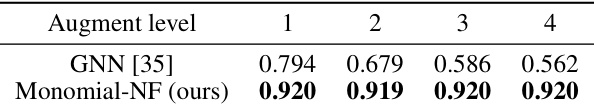

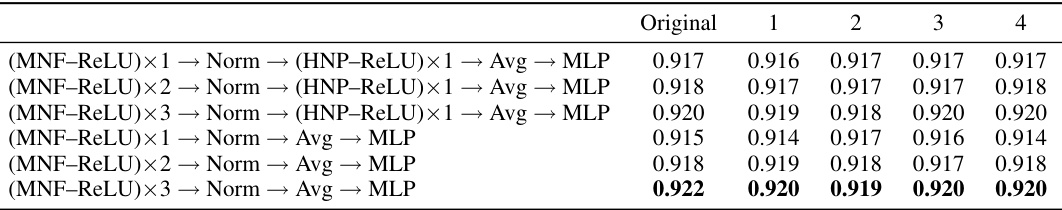

This table presents the CNN prediction results on the Tanh subset of the Small CNN Zoo dataset. It compares the performance of four different models (STATNN, NP, HNP, and Monomial-NFN) using both original and augmented data. The ‘Gap’ column shows the performance difference between the Monomial-NFN model and the next best performing model. Augmented data refers to data that has undergone random hidden vector permutation and scaling based on their monomial matrix group.

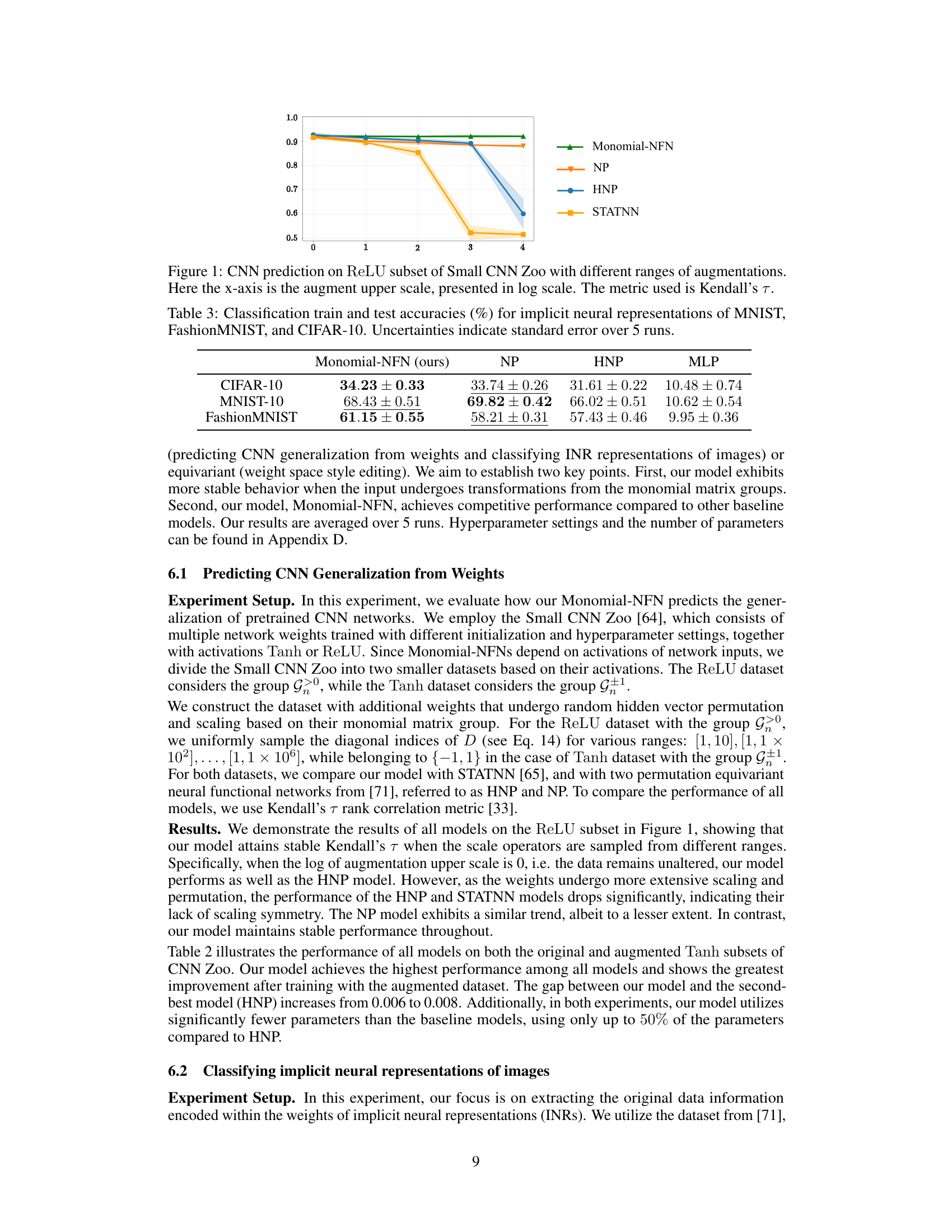

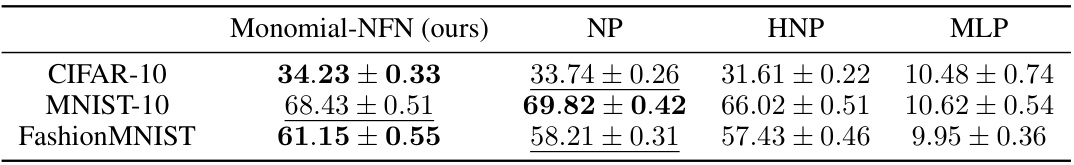

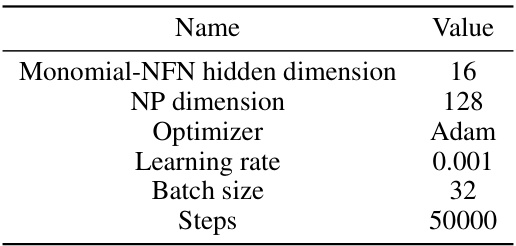

This table presents the classification accuracy results for three different datasets (MNIST, FashionMNIST, and CIFAR-10) using four different methods: Monomial-NFN (the proposed method), NP, HNP, and MLP. The accuracy is reported as a percentage, with standard error over 5 runs indicating variability. The results show a comparison of the proposed method’s performance against existing techniques for classifying implicit neural representations.

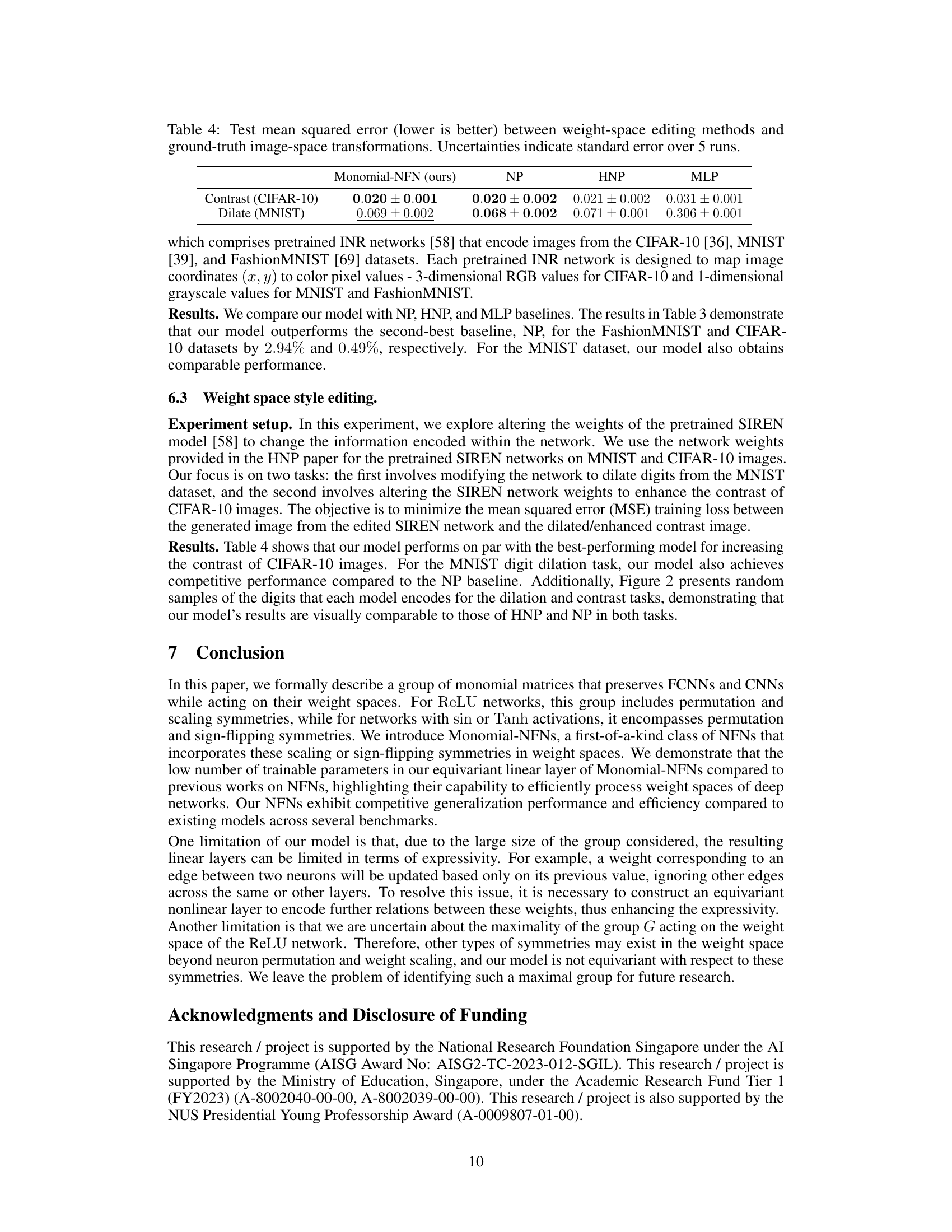

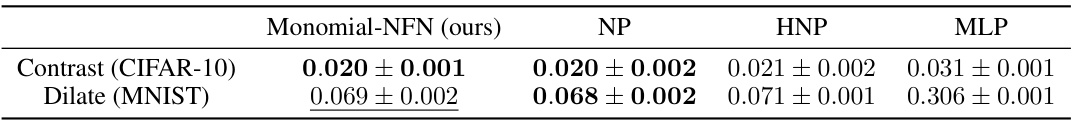

This table presents the mean squared error (MSE) for two weight-space style editing tasks: contrast enhancement on CIFAR-10 images and dilation on MNIST digits. The MSE is a measure of the difference between the edited image generated using the neural network weights and the ground truth (desired) transformation of the image. Lower MSE values indicate better performance. The results are reported for four methods: Monomial-NFN (the proposed method), NP and HNP (baseline methods from prior work), and MLP (a simple multi-layer perceptron). Standard errors are included to show the variability of the results.

This table compares the number of parameters required for a linear equivariant layer in different scenarios. The comparison is made between the use of permutation matrix groups (as in a previous work [71]) and monomial matrix groups (as proposed in this paper). The number of parameters is shown to be significantly reduced when using monomial matrix groups, especially for deep networks. The notation ‘c’ represents the maximum of the weight and bias dimensions for the input layer, and ‘c’’ represents the same for the output layer. ‘L’ represents the number of layers.

This table compares the number of parameters required for a linear equivariant layer in different scenarios. It contrasts the parameter counts when using permutation matrix groups (as in previous work cited as [71]) against the use of monomial matrix groups (the approach proposed in this paper). The number of parameters is shown to be significantly reduced when using the monomial matrix groups, improving model efficiency. The notation ‘c’ represents the maximum of weight and bias dimensions in the input layer, while ‘c’’ is the same for the output layer.

This table compares the number of parameters required for a linear equivariant layer in different neural network architectures. It contrasts the parameter count when using permutation matrix groups (as in prior work [71]) versus monomial matrix groups (the approach introduced in this paper). The key takeaway is that the proposed method using monomial matrix groups significantly reduces the number of parameters, making it more efficient, especially for larger networks. The notation ‘c’ represents the maximum of the weight (w) and bias (b) dimensions.

This table compares the number of parameters required for a linear equivariant layer in different neural network architectures. It contrasts the parameter counts for models using permutation matrix groups (as in a previous work) against those using monomial matrix groups (as proposed by the authors). The key takeaway is that the monomial matrix group approach results in a significantly smaller number of parameters (linear vs. quadratic in L, no, nL). This improved efficiency is a key advantage of the authors’ method, especially when dealing with large-scale networks.

This table compares the number of parameters required for a linear equivariant layer in different scenarios. It contrasts the parameter count for layers using permutation matrix groups (as in a previous work cited as [71]) against layers utilizing monomial matrix groups (the proposed method). The parameter counts are expressed using Big O notation, highlighting the order of growth with respect to various factors such as the number of layers (L) and the maximum dimensions of weights and biases (c and c’). The results show that the proposed method using monomial matrix groups leads to a significantly smaller number of parameters compared to the prior work.

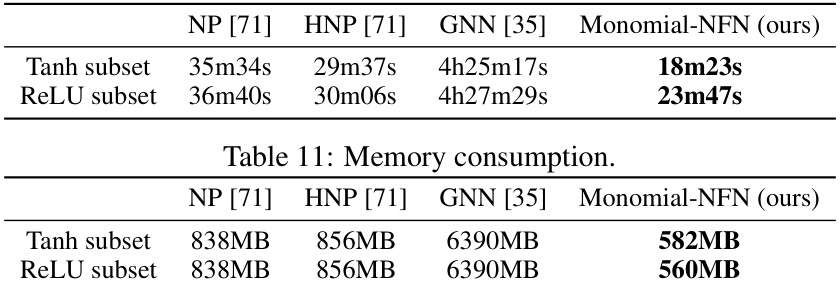

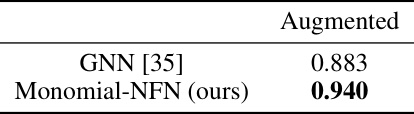

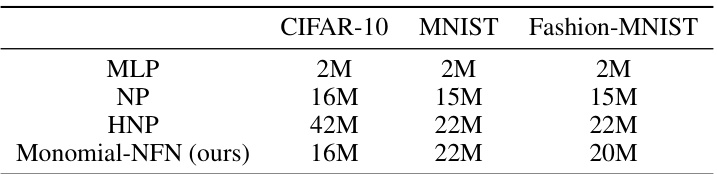

This table compares the memory usage of different neural functional network models (NP, HNP, GNN, and Monomial-NFN) on two subsets of the Small CNN Zoo dataset: Tanh and ReLU. The results show that the Monomial-NFN model has significantly lower memory consumption than the other models.

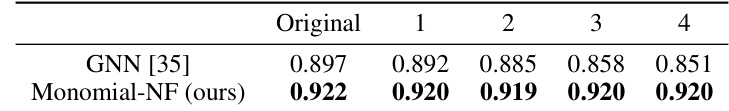

This table presents the results of predicting CNN generalization on the ReLU subset of the Small CNN Zoo dataset using augmented training data. It compares the performance of the GNN [35] method and the Monomial-NFN (the authors’ model) across different levels of augmentation (1, 2, 3, and 4), which correspond to different scaling ranges. The metric used is Kendall’s tau, a rank correlation measure.

This table presents the results of predicting CNN generalization on the ReLU subset of the Small CNN Zoo dataset using the original train data. The performance of the GNN model from [35] and the proposed Monomial-NFN are compared across four different augmentation levels (1-4). Each augmentation level represents a different range of scaling applied to the weights. The metric used is Kendall’s Tau, a measure of rank correlation.

This table presents the performance comparison of different neural functional networks (NFNs) on the task of predicting CNN generalization. The models are evaluated on the Tanh subset of the Small CNN Zoo dataset, both with original and augmented data. The augmented data includes weight scaling and permutation. The table shows the performance of each model using Kendall’s Tau, a measure of rank correlation. The results demonstrate that the proposed Monomial-NFN model outperforms other baselines.

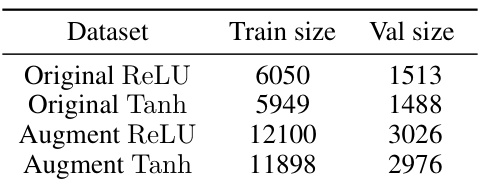

This table presents the number of training and validation instances for four different datasets used in the CNN generalization prediction task. The datasets are categorized by activation function (ReLU or Tanh) and whether or not they have been augmented. Augmented datasets are created by doubling the size of the original datasets with additional weight samples.

This table compares the number of parameters required for a linear equivariant layer in different neural network models. It contrasts the parameter counts for models using permutation matrix groups (as in a previous work) and monomial matrix groups (as proposed in this paper). The number of parameters is shown to scale differently with the number of layers (L) and the maximum dimensions of weights and biases (c and c’). The proposed method using monomial matrix groups shows a significant reduction in the number of parameters compared to methods based on permutation groups.

This table compares the performance of four different models (STATNN, NP, HNP, and Monomial-NFN) on the task of predicting the generalization performance of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The models are evaluated on a subset of the Small CNN Zoo dataset, using both the original dataset and an augmented version of the dataset. The augmented dataset includes additional samples generated by applying random hidden vector permutation and scaling transformations. The results are presented as the accuracy of the CNN prediction, along with the difference (gap) between Monomial-NFN’s performance and the second-best performing model (HNP).

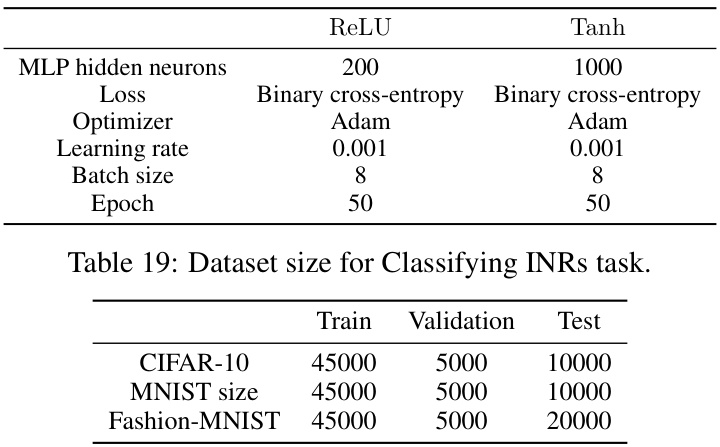

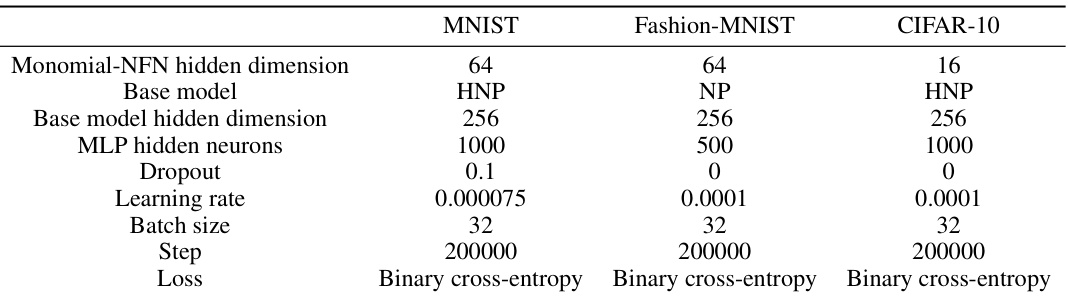

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Monomial-NFN model when classifying Implicit Neural Representations (INRs) for three different datasets: MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, and CIFAR-10. The hyperparameters include the hidden layer dimension of the Monomial-NFN, the base model used (either HNP or NP), the base model’s hidden dimension, the number of neurons in the MLP layers, the dropout rate, the learning rate, the batch size, the number of training steps, and the loss function employed (Binary cross-entropy). The values vary for each dataset, indicating dataset-specific optimizations.

This table shows the classification accuracy results of four different neural network models (Monomial-NFN, NP, HNP, MLP) on three different datasets (MNIST, FashionMNIST, CIFAR-10). The results are shown as the mean accuracy and the standard error across five runs. The table highlights the performance of Monomial-NFN compared to traditional methods and other state-of-the-art approaches.

This table presents the performance comparison of different neural functional network models (STATNN, NP, HNP, and Monomial-NFN) on a CNN prediction task using the Tanh subset of the Small CNN Zoo dataset. The results are shown for both original and augmented data, indicating the performance improvement of Monomial-NFN with data augmentation. The ‘Gap’ column represents the performance difference between Monomial-NFN and the second-best model. The results demonstrate that Monomial-NFN outperforms all other models, especially when using augmented data.

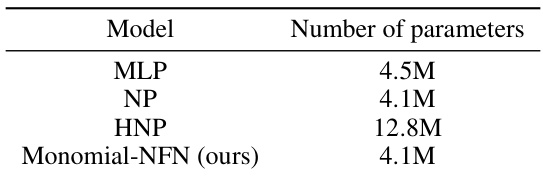

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Monomial-NFN model during the weight space style editing experiments. It shows the values chosen for the model’s hidden dimension, NP dimension (referencing another model), optimizer, learning rate, batch size, and the number of training steps.

This table presents the CNN prediction results on the Tanh subset of the Small CNN Zoo dataset. It compares the performance of four different neural functional network models (STATNN, NP, HNP, and Monomial-NFN) using both original and augmented data. The ‘Gap’ column indicates the performance difference between the best-performing model (Monomial-NFN) and the second-best performing model for each dataset. The results highlight the superior performance and stability of the Monomial-NFN model, particularly when using augmented data, showcasing its ability to generalize effectively to variations within the weight space.

Full paper#