↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current 3D human pose and shape estimation methods face challenges due to the diverse formats of available data and the high cost of re-annotation. This makes it difficult to create robust and generalizable models that perform well across different datasets. Additionally, existing methods often output a specific format (pre-defined joints, keypoints, or meshes), limiting flexibility for downstream applications.

The proposed Neural Localizer Fields (NLF) method addresses these challenges by learning a continuous field of point localizer functions. This allows the model to query any arbitrary point within the human volume and obtain its estimated location in 3D. NLF outperforms state-of-the-art methods on several benchmarks by efficiently unifying diverse data sources and easily handling various annotation formats, including meshes, 2D/3D skeletons, and dense pose, demonstrating the model’s scalability and versatility.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it presents a novel and efficient method for 3D human pose and shape estimation, overcoming the limitations of existing methods that struggle with diverse data formats and scalability. Its flexible and generalizable approach enables large-scale training from heterogeneous data sources, paving the way for more robust and accurate models in various applications, including virtual reality, animation, and human-computer interaction. This work is significant because of its potential to advance research in large-scale multi-dataset learning and improve downstream applications requiring versatile human pose and shape representations.

Visual Insights#

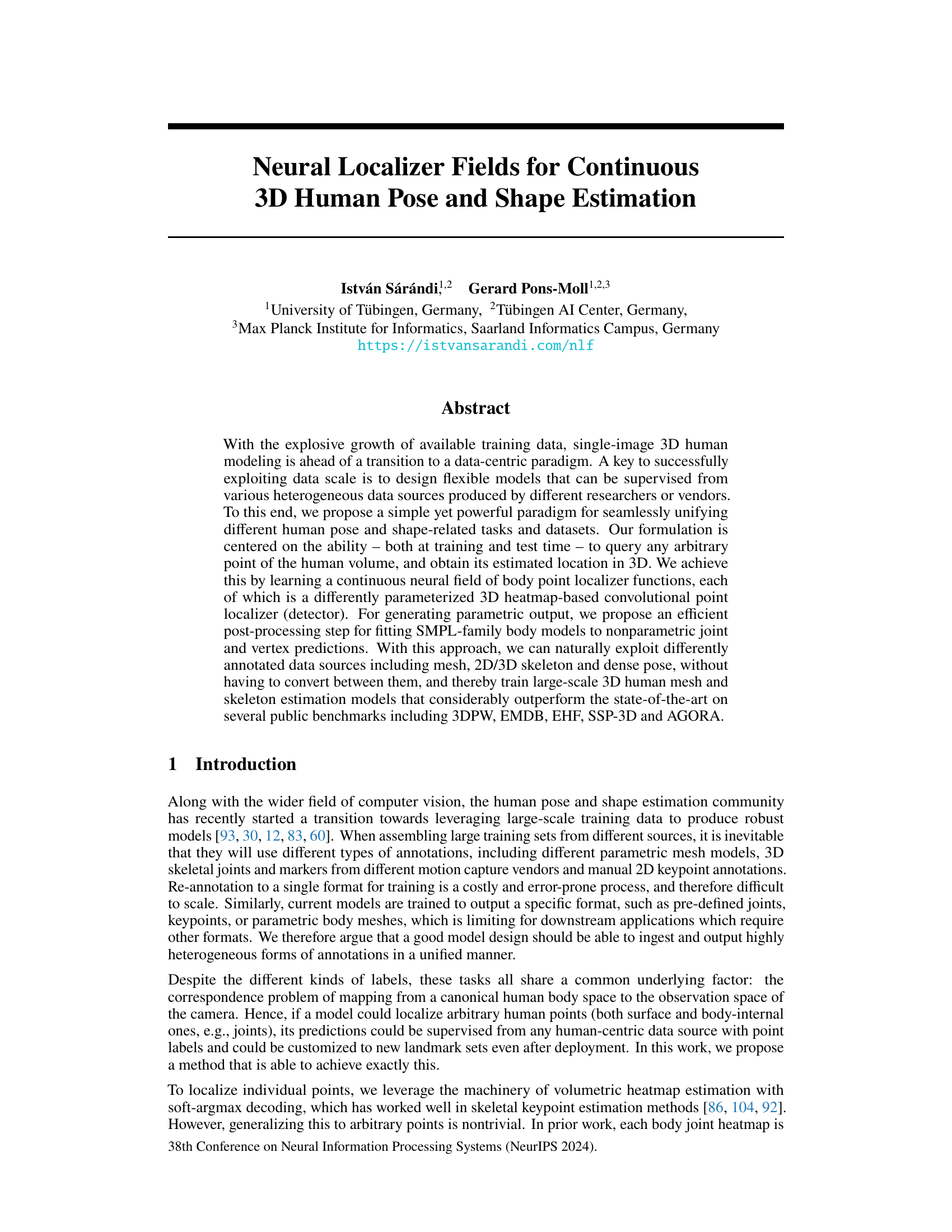

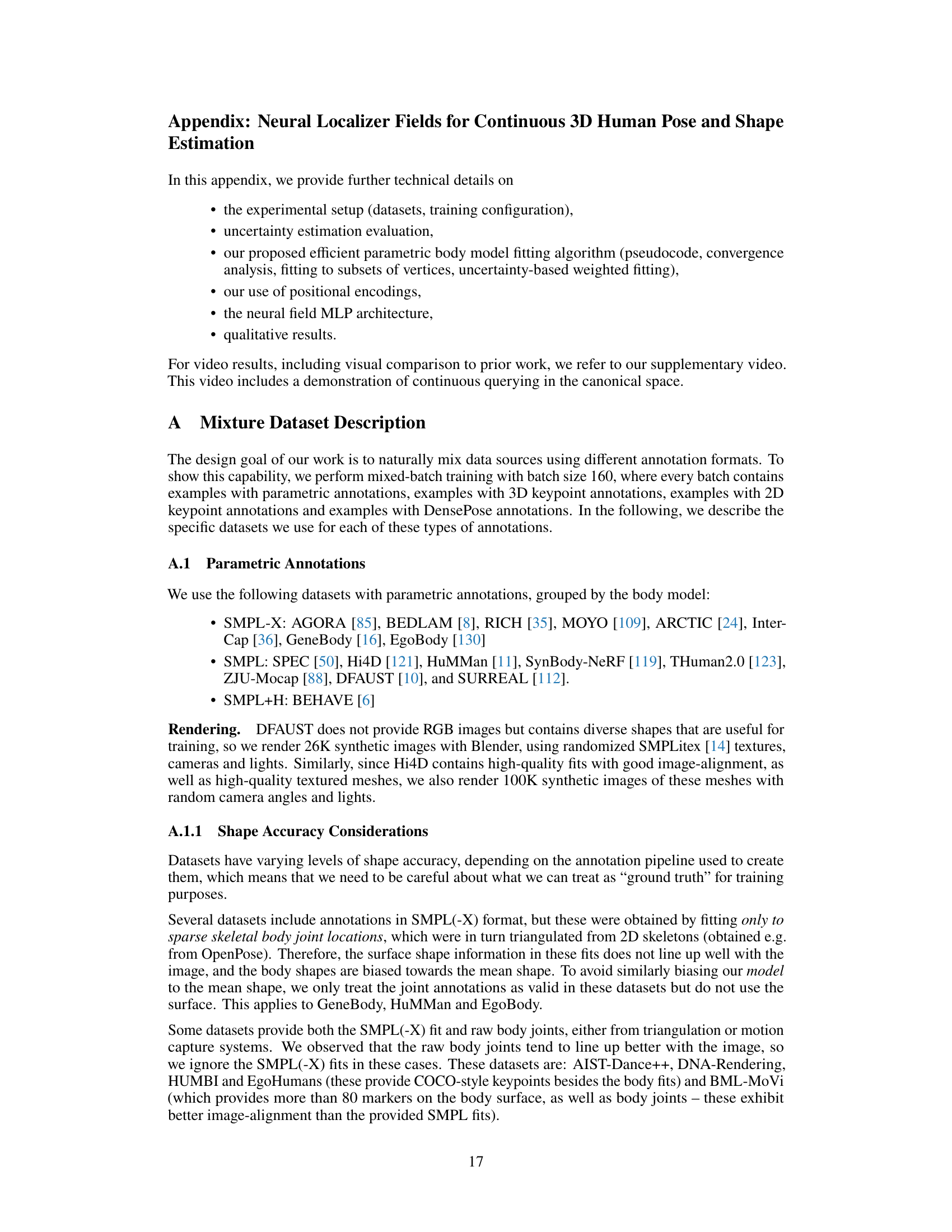

This figure illustrates the core idea of the Neural Localizer Field (NLF) method proposed in the paper. The NLF aims to learn a single model capable of localizing any point on the human body from a single RGB image, regardless of the type of annotation used during training (mesh, 2D/3D skeleton, dense pose). The model achieves this by learning a continuous neural field that stores all localization functions, allowing for flexibility at test time to query and predict the 3D coordinates of any user-specified point. This approach allows the model to handle diverse data sources seamlessly, avoiding the need for re-annotation or conversion between different formats.

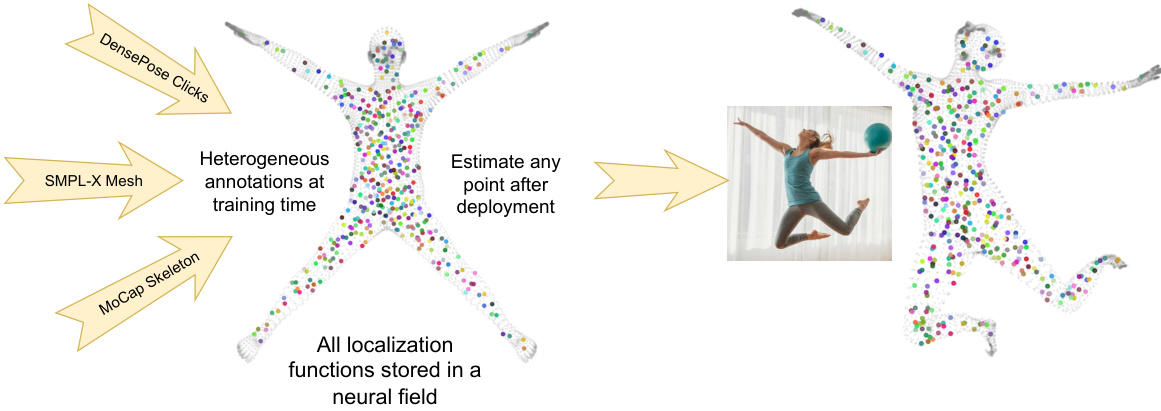

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the positional encoding methods used in the Neural Localizer Field (NLF) model. Four different methods are compared: using plain XYZ coordinates, using a global point signature (GPS) derived from the Laplacian, using learnable Fourier features, and using learnable Fourier features initialized with the GPS. The table shows the impact of each method on several metrics, including SSP3D mIoU, 3DPW P-MVE, EMDB P-MVE, and 3DPW MPJAE, demonstrating that using learnable Fourier features, especially when initialized with the GPS, yields the best performance.

In-depth insights#

Neural Localizer Field#

The core concept of “Neural Localizer Fields” is to learn a continuous function that maps any 3D point in a canonical human body representation to its corresponding 2D or 3D location in an image or world coordinate system. This is achieved by training a neural network to predict the parameters of a convolutional layer, making it a hypernetwork. The input to this hypernetwork is the 3D point’s location, and the output modifies the convolution to predict the heatmap from which the 2D/3D location of the point is determined. This allows for flexible and efficient localization of any arbitrary point on or within the body, eliminating the need for specialized networks for different point sets (e.g., skeleton joints vs. mesh vertices). The approach’s strengths lie in its ability to unify diverse data sources, handling heterogeneous annotations seamlessly during training, and outputting customized point sets at test time. This paradigm shifts the paradigm towards a data-centric approach and enables large-scale training, overcoming limitations of previous methods constrained to specific point annotations.

Multi-Dataset Training#

Multi-dataset training is a powerful technique for enhancing the robustness and generalizability of machine learning models, especially in domains with limited data. By leveraging data from diverse sources, models can learn to handle a broader range of variations and avoid overfitting to the idiosyncrasies of a single dataset. This approach is particularly crucial in the field of 3D human pose and shape estimation where obtaining large, consistent datasets is expensive and challenging. Careful consideration of data preprocessing and normalization is essential to harmonize diverse data formats and annotation styles. The success of multi-dataset training hinges on the ability to effectively align and integrate data from various sources, often requiring sophisticated techniques for handling heterogeneity and inconsistencies. Furthermore, the choice of training methodology, such as appropriate loss functions and training strategies, is critical for achieving optimal performance with multi-dataset training. While this approach offers significant benefits, it also introduces increased complexity and computational costs. Proper evaluation across multiple datasets is crucial to verify the improved generalization and robustness of the model.

Efficient Body Fitting#

The section on “Efficient Body Fitting” details a novel algorithm for efficiently fitting SMPL body models to the non-parametric mesh predictions generated by the Neural Localizer Field (NLF). This is crucial because while NLF excels at non-parametric point localization, parametric representations are often preferred for downstream applications. The method cleverly alternates between optimizing global body part orientations using the Kabsch algorithm and solving for shape coefficients via regularized linear least squares, converging quickly within 2-4 iterations. This iterative approach is significantly faster than traditional methods. The key innovation is the direct geometry-based solution, avoiding the slower and less generalizable alternatives such as training an MLP. This efficiency is further enhanced by leveraging the per-point uncertainty estimates from NLF for weighted fitting and by fitting only to a subset of vertices, greatly improving computational speed without sacrificing accuracy. The algorithm’s speed and accuracy make it ideally suited for GPU acceleration, showcasing the practical impact of this contribution to the field of 3D human pose and shape estimation.

Positional Encoding#

The effectiveness of positional encoding in neural fields is explored, comparing various techniques. Plain XYZ coordinates provide a simple baseline. Global Point Signatures (GPS), derived from the Laplacian operator, capture high-frequency information. Learnable Fourier features, trained end-to-end, further improve performance, particularly when initialized with GPS. The results demonstrate that the choice of positional encoding significantly impacts model accuracy and robustness. The use of GPS or learnable Fourier features (especially when initialized) significantly outperforms plain coordinates, highlighting the importance of capturing high-frequency information within the canonical human body volume for accurate and robust pose and shape estimation. This suggests that careful selection of positional encodings is crucial for optimal performance in neural localizer fields.

Uncertainty Estimation#

The section on ‘Uncertainty Estimation’ explores the crucial aspect of quantifying the confidence of the model’s predictions. The authors acknowledge that naively incorporating uncertainty into the loss function using negative log-likelihood (NLL) can negatively impact prediction accuracy. They propose a solution using the β-NLL loss, which addresses the limitations of NLL. This modified loss function helps maintain high accuracy and improves the correlation between predicted uncertainty and actual error. Results show a significant enhancement in uncertainty quality when using the improved loss function. The analysis of uncertainty is not merely a technical exercise but contributes to the overall robustness and reliability of the 3D human pose and shape estimation model, making it a valuable contribution to the field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

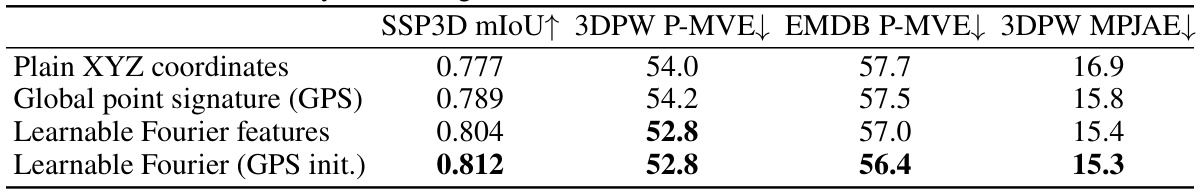

This figure illustrates the Neural Localizer Field (NLF) method. Image features are processed through a vision backbone and fed into a 1x1 convolutional layer. The key innovation is a dynamic modulation of this layer by a neural field, which takes a 3D query point (p) as input and outputs the weights (W(p)) for the convolutional layer. This allows the model to localize any arbitrary point within the human body volume by generating a heatmap that, after a soft-argmax operation, provides the 3D observation-space coordinates (p’). The process allows for flexible training with diverse data sources and flexible estimation of any point during inference.

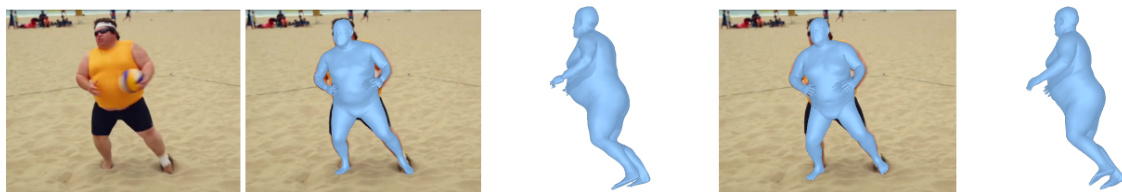

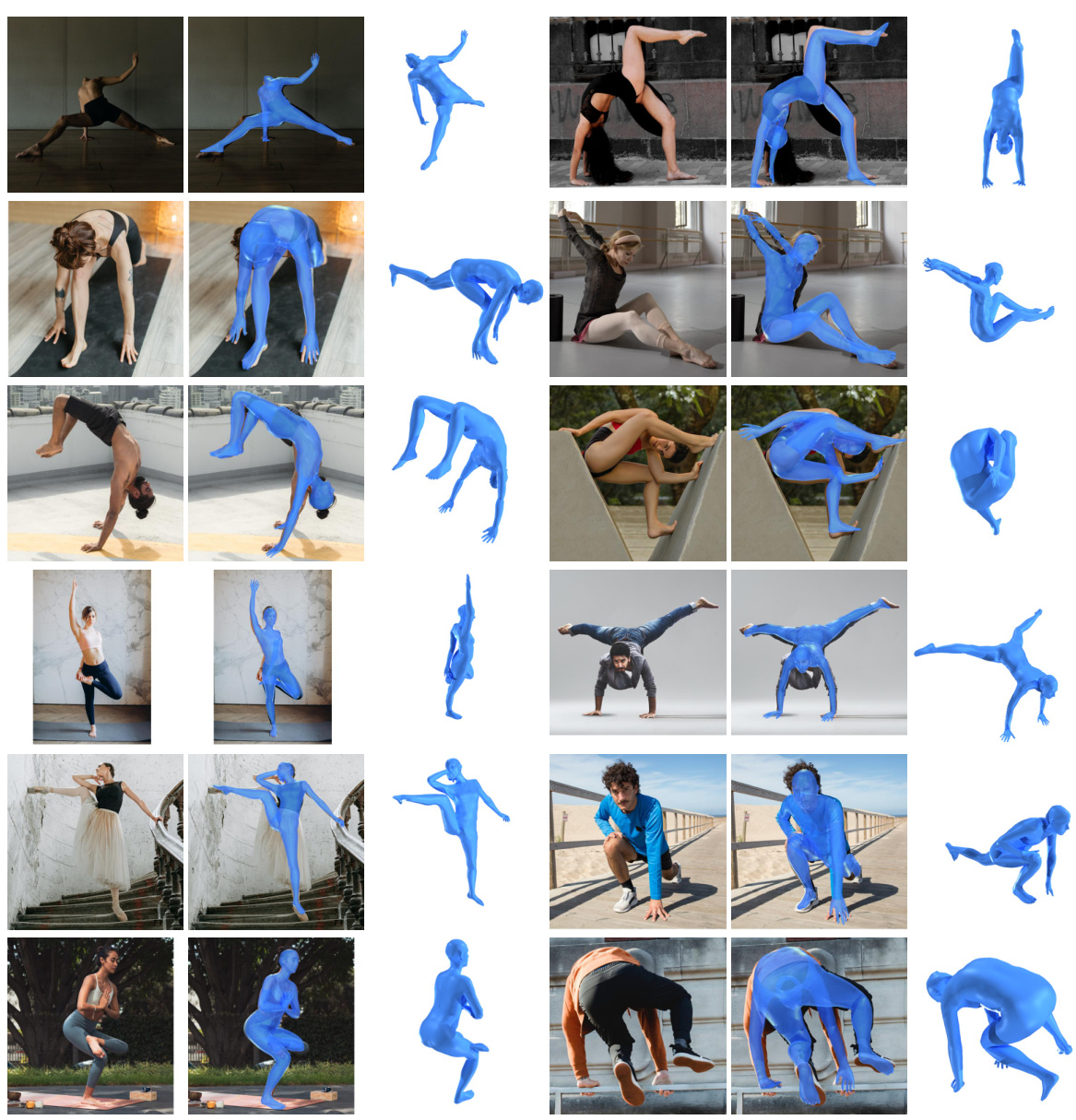

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the results obtained using the proposed Neural Localizer Field (NLF) method for 3D human pose and shape estimation. The left side displays the nonparametric output of the NLF, which provides a high-quality prediction without the constraints of a parametric model. The right side shows the output obtained after applying a fast SMPL fitting algorithm to the nonparametric output. This demonstrates the method’s ability to produce both nonparametric and parametric representations, allowing flexibility and efficiency in applications. The results are shown on SSP-3D (Shape and Pose estimation from a Single image)

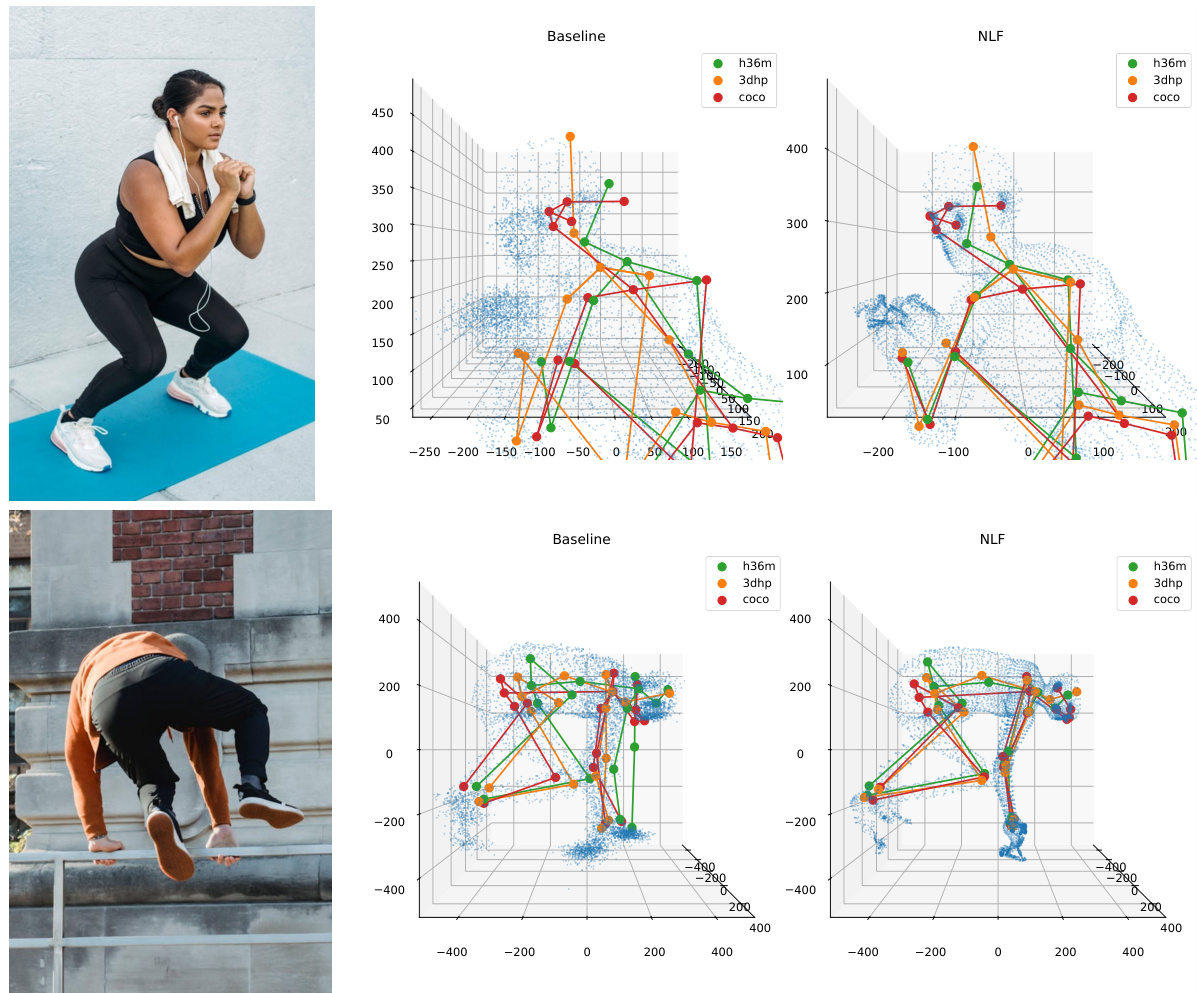

This figure demonstrates the flexibility of the Neural Localizer Field (NLF) model in localizing any point in the human body. It shows that the model can predict various landmark sets (SMPL, SMPL-X, COCO, Human3.6M) as well as arbitrary points sampled within the canonical human volume. The results show that the model is capable of estimating points on both the surface and inside the volume of the body, and that it can be customized to output any user-defined landmark set.

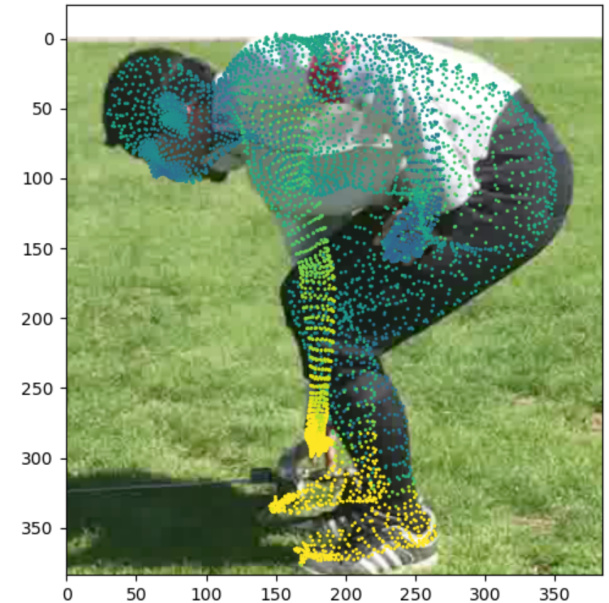

This figure shows the uncertainty estimation results of the Neural Localizer Field (NLF) method. The color coding represents the level of uncertainty for each estimated 3D point, with yellow indicating high uncertainty and blue indicating low uncertainty. The figure illustrates that occluded body parts tend to have higher uncertainty estimates, as expected. This demonstrates the NLF’s ability to provide uncertainty information, which is valuable for downstream tasks and applications.

This figure demonstrates the Neural Localizer Field’s (NLF) ability to localize any point in the 3D human body from a single RGB image. The model can estimate any user-defined points at test time, including SMPL/SMPL-X joints and vertices, COCO and Human3.6M joints, as well as arbitrary internal points. The figure shows examples of these various point localizations, illustrating the model’s flexibility and generalizability.

The figure shows the convergence properties of the iterative SMPL fitting algorithm. The algorithm iteratively refines the SMPL body model parameters to fit the non-parametric predictions. The plot shows that the error (PVE-T-SC) decreases and the IoU increases with each iteration, converging within approximately three iterations to the state-of-the-art results.

This figure illustrates the Neural Localizer Field (NLF) architecture. It shows how image features are processed through a vision backbone to obtain feature maps. These maps are then used by a dynamically modulated convolutional layer to generate heatmaps which are decoded to obtain 3D point coordinates. The key component is the Neural Localizer Field, which modulates the convolutional layer based on a query point, allowing the network to localize any point in the human body volume, both during training and testing. This flexibility enables the model to seamlessly handle various data formats and annotations.

The figure shows the architecture of the neural network that parameterizes the point localizer network. The neural field has an MLP-like structure, starting with learnable Fourier features (fully connected layer followed by sine and cosine activations). After two further fully connected layers with a GELU activation in between, we arrive at the layer whose output is initially trained to approximate the global point signature (GPS) derived from the volumetric Laplacian. Further two FC layers with GELU in between yield the parameters to modulate the convolutional layer of the point localizer network.

This figure illustrates the core idea of the Neural Localizer Fields (NLF) method. It shows that the model can learn to localize any point on a human body from a single RGB image, regardless of the annotation type used during training (mesh, 2D/3D skeleton, dense pose). This flexibility allows for training on diverse, heterogeneous datasets without the need for re-annotation, leading to a more general and robust human pose and shape estimation model.

This figure demonstrates the Neural Localizer Field’s ability to localize arbitrary points in the 3D human body. It shows examples of localizing different types of points (SMPL/SMPL-X joints and vertices, COCO keypoints, Human3.6M keypoints) and arbitrary points from within the human volume, showcasing the flexibility and generality of the proposed method.

More on tables

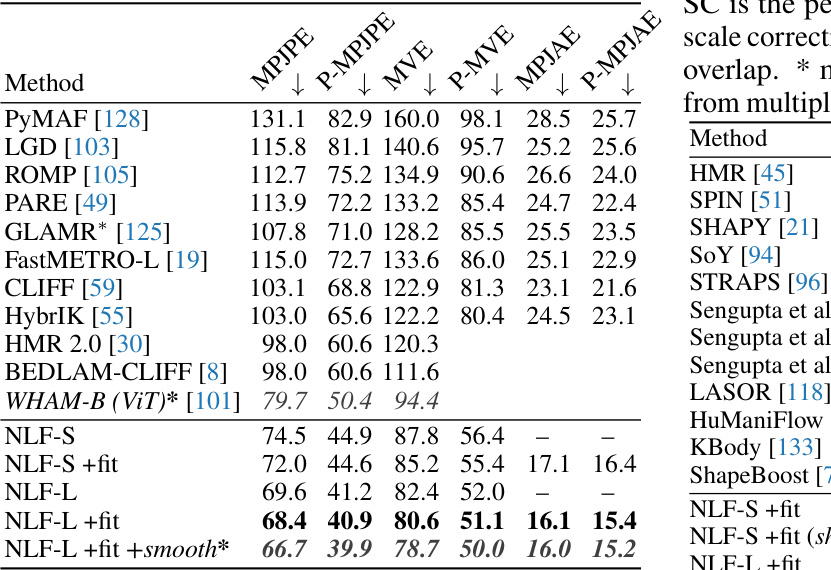

This table presents the results of the proposed Neural Localizer Fields (NLF) method and several baseline methods on the 3DPW dataset for 14 joints. The results are separated into two groups: models trained without the 3DPW training data and models trained with 3DPW training data. The metrics used for evaluation include MPJPE (Mean Per-Joint Position Error), P-MPJPE (Procrustes-aligned MPJPE), MVE (Mean per-Vertex Error), and P-MVE (Procrustes-aligned MVE). The asterisk (*) indicates that the method uses temporal information (multiple frames) for its predictions. The table shows that NLF outperforms existing methods.

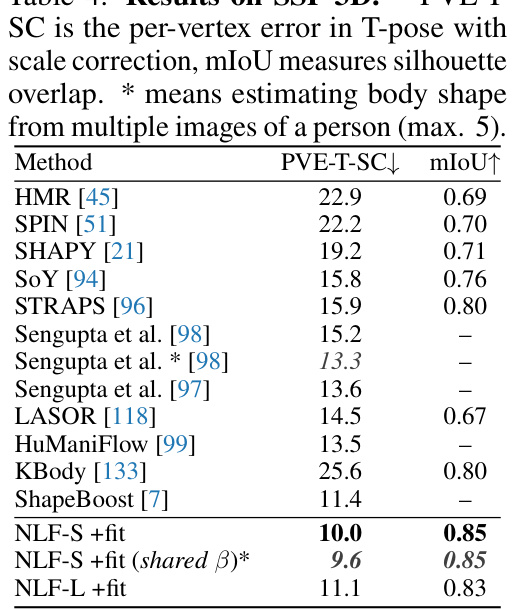

This table presents the results of the proposed Neural Localizer Field (NLF) method on the SSP-3D benchmark, which focuses on evaluating shape prediction performance. The table compares NLF against various state-of-the-art methods using two metrics: PVE-T-SC (per-vertex error in T-pose with scale correction) and mIoU (mean Intersection over Union, a measure of silhouette overlap). The results show that NLF significantly outperforms existing methods, particularly when considering shape estimation from multiple images of the same person.

This table presents the results of the proposed Neural Localizer Field (NLF) method on the SSP-3D benchmark dataset. It compares the performance of NLF against several state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods for 3D human shape estimation. The evaluation metrics used are PVE-T-SC (per-vertex error in T-pose with scale correction) and mIoU (mean Intersection over Union for silhouette overlap). The results show that NLF achieves SOTA performance, especially when using multiple images of the same person for shape estimation.

This table presents the quantitative results of the proposed Neural Localizer Field (NLF) method on the AGORA benchmark. The results are broken down by various metrics (MVE, MPJPE, NMVE, NMJE) for the whole body and body parts such as face, left hand, and right hand. It compares the NLF model’s performance with other state-of-the-art methods. The model is fine-tuned on the AGORA dataset, which focuses on SMPL-X models.

This table presents the results of the proposed Neural Localizer Field (NLF) model on three commonly used skeleton estimation benchmarks: Human3.6M, MPI-INF-3DHP, and MuPoTS-3D. The metrics used are MPJPE (Mean Per Joint Position Error), P-MPJPE (Procrustes aligned MPJPE), PCK (Percentage of Correct Keypoints), AUC (Area Under Curve), and PCK-detected (Percentage of Correct Keypoints for detected joints). The results are compared against the MeTRAbs-ACAE model, which serves as the baseline. Lower MPJPE and higher PCK scores indicate better performance. The NLF model demonstrates competitive performance across all three benchmarks.

This table presents the quantitative results of the proposed Neural Localizer Field (NLF) method on the EMDB benchmark. It compares the performance of NLF against several state-of-the-art methods across various metrics, including MVE (Mean per-vertex error) and P-MPJPE (Procrustes-aligned Mean per-joint position error), for the full body, hands, and face. The results showcase NLF’s superior performance, highlighting its ability to accurately estimate the 3D shape and pose of humans, especially in challenging scenarios involving significant self-occlusions or body part truncation.

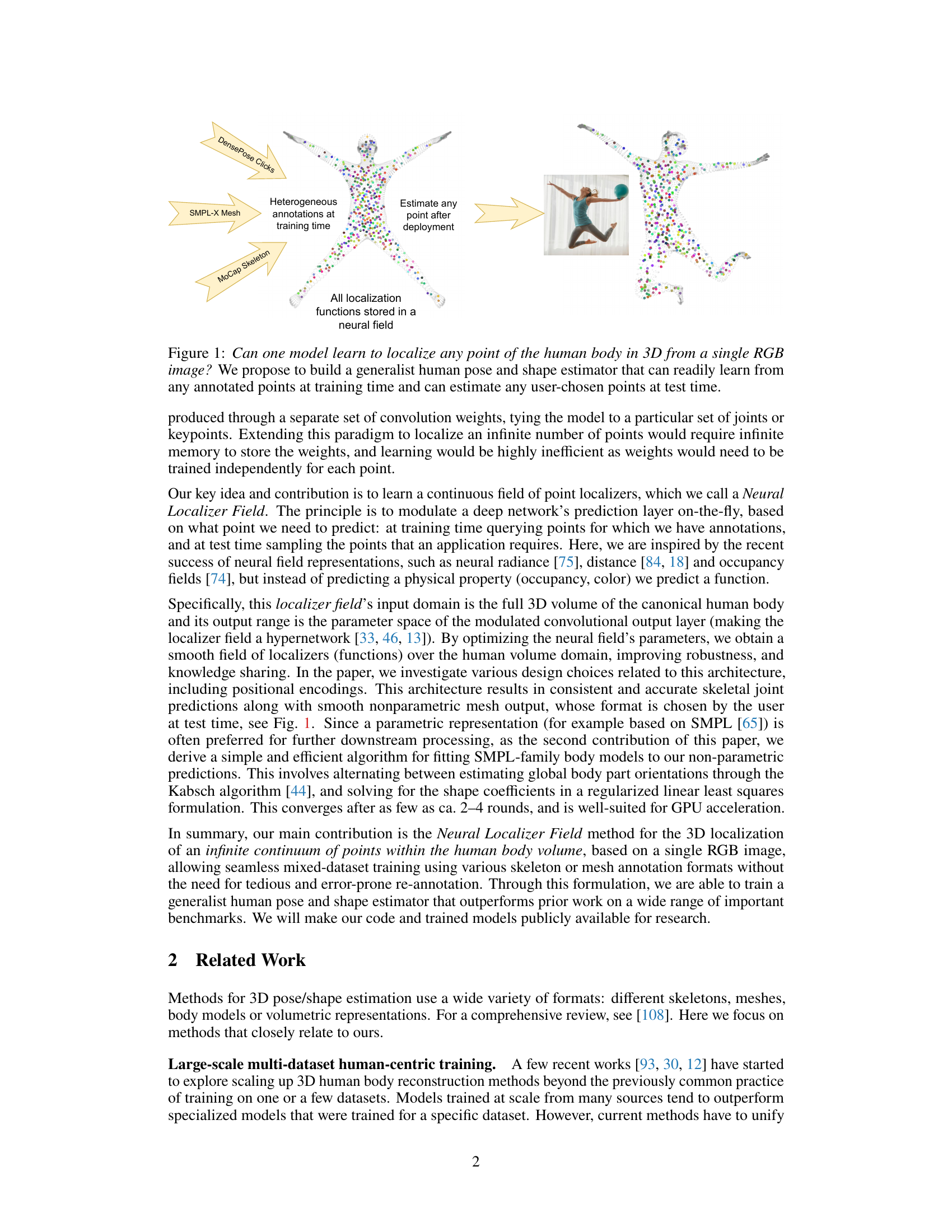

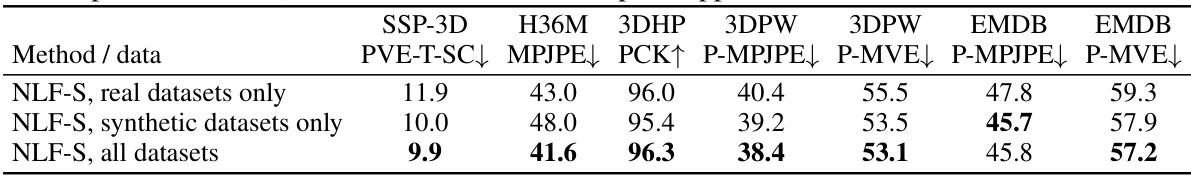

This table shows the ablation study of training data on the NLF model. It compares the model’s performance when trained on only real datasets, only synthetic datasets, and all datasets combined. The results demonstrate that using all available data leads to superior performance, highlighting the benefit of diverse and large-scale training data for this model.

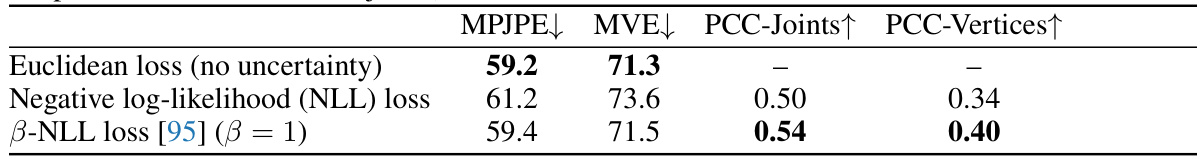

This table presents an ablation study on the uncertainty estimation method used in the Neural Localizer Field (NLF) model. It compares three different loss functions: Euclidean loss (without uncertainty), negative log-likelihood (NLL) loss, and the β-NLL loss proposed by Seitzer et al. [95]. The results show the MPJPE and MVE (mean per-joint and mean per-vertex position errors) for each loss function, as well as the Pearson correlation coefficients between the predicted uncertainties and true errors for both joints and vertices. The β-NLL loss shows a balance between good uncertainty correlation and low prediction error.

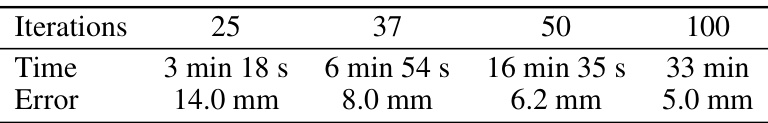

This table compares the performance of the official SMPL-to-SMPLX converter with the proposed efficient body model fitter. It shows the time taken and average error for different numbers of iterations. The proposed method is significantly faster and achieves comparable accuracy.

This table presents the ablation study of using uncertainty-based weights in the body model fitting process. The results show that weighting points by their uncertainty estimates leads to marginal improvements in the evaluation metrics (MPJPE, P-MPJPE, MVE, and P-MVE) on both the 3DPW and EMDB datasets when using the NLF-L model. The improvement is modest suggesting that the impact of this approach is minor.

This table compares the performance of different methods on the 3DPW dataset using 24 joints. It contrasts results from the main paper, where only the test subset of 3DPW was used for evaluation. The table shows MPJPE, P-MPJPE, MVE, and P-MVE metrics for MeTRAbs-ACAE-S, MeTRAbs-ACAE-L, NLF-S, and NLF-L methods, both with and without post-processing SMPL fitting.

Full paper#