↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Designing and updating complex AI systems (like coding assistants or robots) is a challenge because current methods struggle with non-differentiable workflows and rich feedback. This paper introduces a novel approach to automate this process.

The paper proposes a new framework called “Trace” which uses execution traces of a workflow and LLMs for optimization. Trace converts workflow optimization problems to OPTO problems. Experimental results showcase its effectiveness in several domains like numerical optimization, prompt engineering, and robot control, often outperforming specialized optimizers. This approach makes the design and update of AI systems more efficient and scalable.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on generative optimization, large language models (LLMs), and AI workflow automation. It introduces a novel framework, Trace, and a general-purpose optimizer, OptoPrime, enabling end-to-end optimization of complex, heterogeneous AI workflows, significantly improving efficiency and scalability compared to existing methods. The work opens new avenues for research on LLM-based optimization and the development of next-generation interactive learning agents.

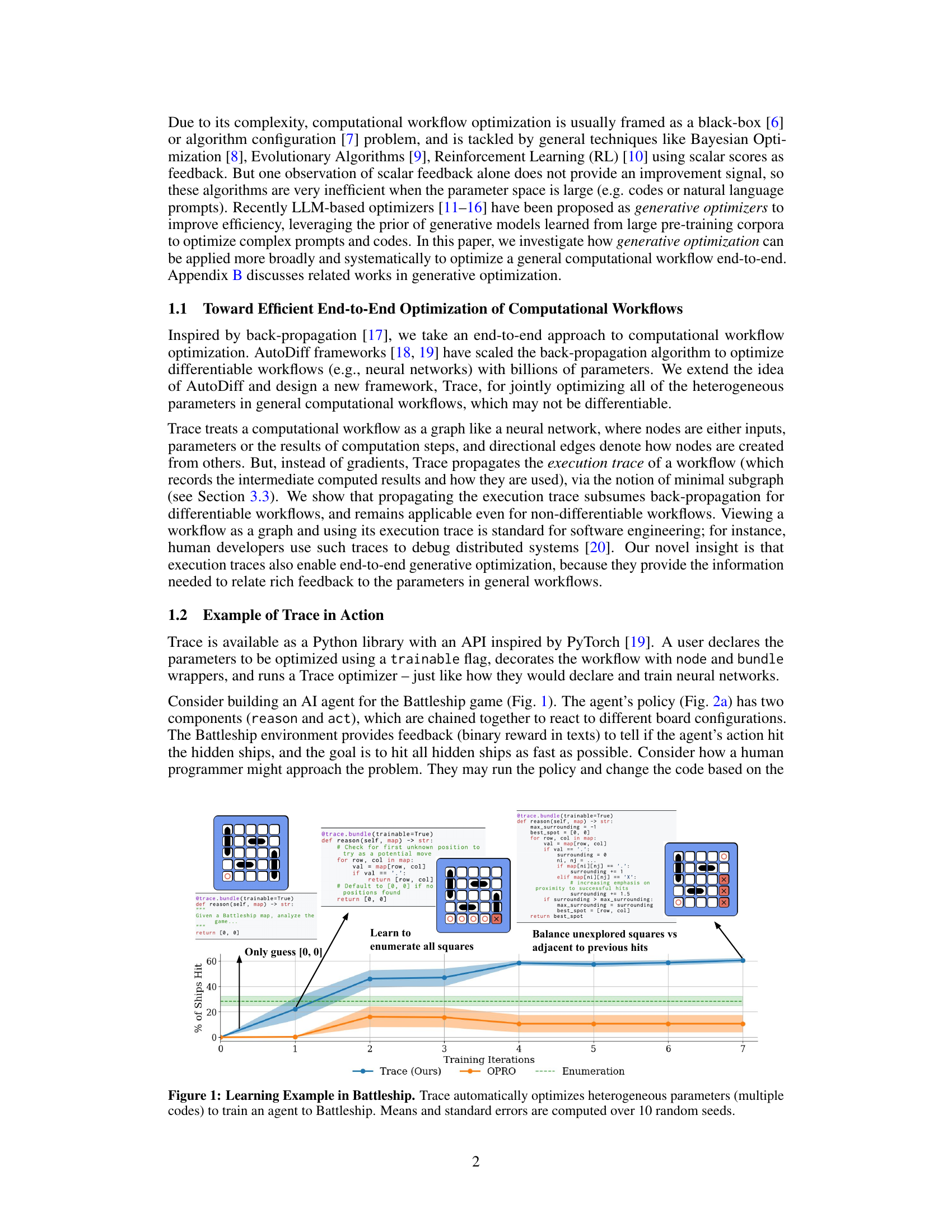

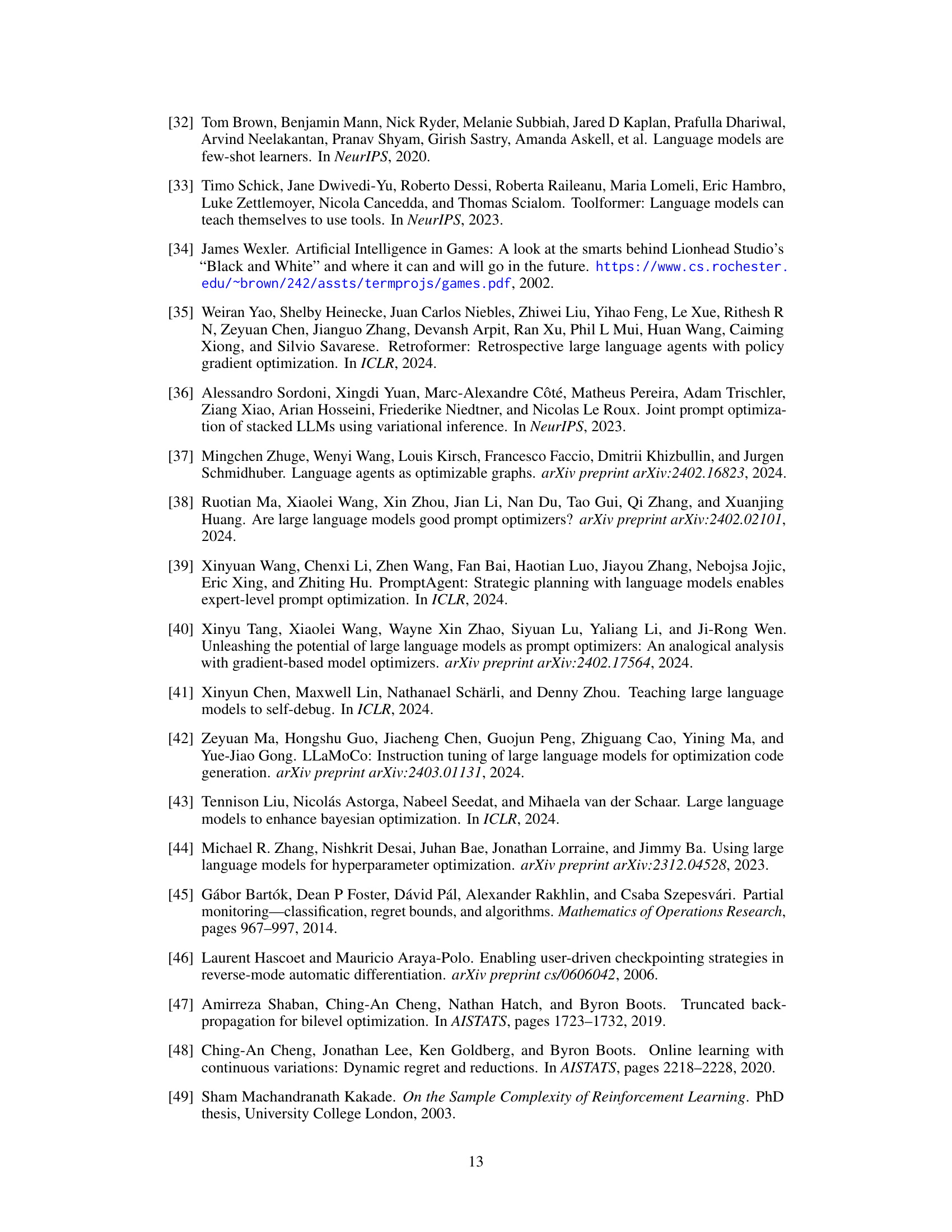

Visual Insights#

This figure shows an example of using Trace to optimize a Battleship-playing agent. The agent’s policy consists of two parts: a reasoning component that analyzes the game board, and an action component that selects a target coordinate. Trace automatically optimizes both the code for the reasoning and action components. The graph shows that Trace outperforms OPRO (a state-of-the-art LLM-based optimizer) and a simple enumeration baseline by learning to effectively enumerate all squares and balance exploration and exploitation. The results are averaged over 10 different random seeds.

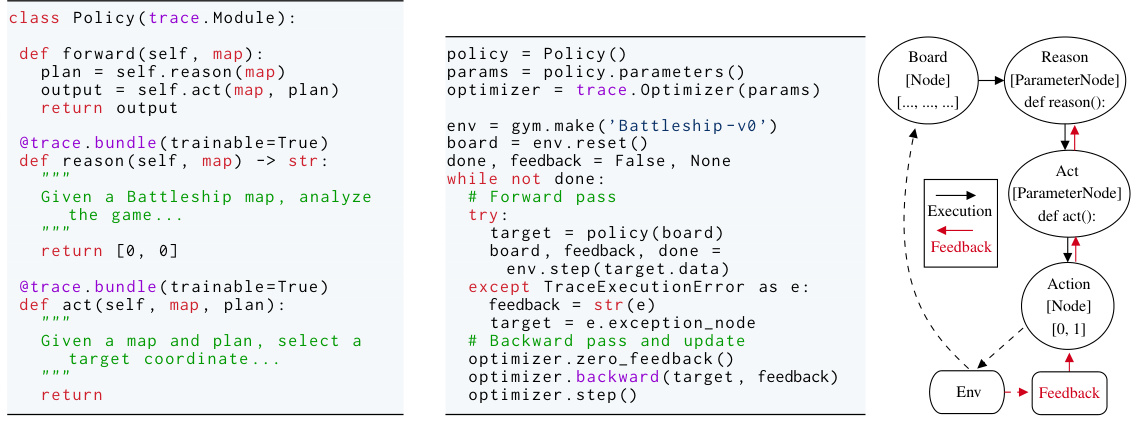

This table presents the number of tokens used by OPRO and OptoPrime during the first iteration of optimization for different tasks. It highlights the significantly higher token usage of OptoPrime compared to OPRO. However, the paper notes that even with significantly more iterations of OPRO to equalize token costs, OptoPrime still outperforms OPRO, indicating that OptoPrime’s superior performance isn’t solely due to increased computational resources but rather its utilization of additional information from the execution trace.

In-depth insights#

OPTO Framework#

The OPTO framework, as presented in the research paper, introduces a novel paradigm for optimizing computational workflows. It moves beyond the limitations of traditional AutoDiff by handling non-differentiable systems and incorporating rich feedback, which is not limited to scalar scores. The core of OPTO is its ability to leverage workflow execution traces, akin to back-propagated gradients, to effectively interpret feedback and update parameters iteratively. This approach makes OPTO applicable to a wide range of optimization problems that go beyond traditional differentiable systems. The framework’s strength lies in its ability to connect heterogeneous parameters (codes, prompts, hyperparameters) and feedback (console output, user responses) within a unified mathematical setup. Trace, a Python library, facilitates the efficient conversion of workflow optimization problems into OPTO instances, providing a practical implementation for this novel approach. This allows for the development of general-purpose generative optimizers, demonstrating the framework’s potential for end-to-end optimization of complex AI systems.

LLM-based OPTO#

LLM-based OPTO represents a novel approach to optimization problems, particularly those arising in complex computational workflows. By integrating large language models (LLMs) within the Optimization with Trace Oracle (OPTO) framework, this method addresses the limitations of traditional AutoDiff approaches. The core idea is leveraging LLMs’ ability to interpret rich feedback, going beyond simple scalar scores, and utilize execution traces to guide parameter updates. This contrasts with traditional gradient-based methods that struggle with non-differentiable components and heterogeneous parameters. The use of execution traces as a form of ‘back-propagated information’ allows for effective optimization in non-differentiable scenarios, providing a powerful mechanism to connect high-level feedback to low-level parameter adjustments. While the approach is promising, further research is needed to address scalability issues, particularly concerning the computational cost and memory requirements of LLMs.

Trace Oracle#

The concept of a ‘Trace Oracle’ presents a novel approach to optimization, particularly within the context of complex, non-differentiable computational workflows. Instead of relying solely on scalar feedback like traditional methods, a Trace Oracle provides rich feedback in the form of execution traces. These traces, essentially logs of the workflow’s execution path, are akin to gradients in traditional AutoDiff, providing valuable information for understanding the workflow’s behavior. The Trace Oracle’s key innovation lies in its ability to interpret heterogeneous data, which could include text, numerical values, and program states, providing a holistic view for parameter optimization. This richer feedback enables the Trace Oracle to guide the update of diverse parameters in a computational workflow, enabling a more efficient and adaptable optimization process compared to traditional black-box optimization techniques. The ability to handle non-differentiable processes makes the Trace Oracle especially powerful for tasks such as prompt optimization, where the impact of subtle parameter changes can be difficult to assess with traditional methods. The fundamental power of the Trace Oracle lies in its ability to provide contextual information, going beyond simple scalar rewards. By incorporating execution traces, the optimizer gains an understanding of the system’s internal workings, leading to more effective updates and potentially faster convergence.

Empirical Studies#

An Empirical Studies section in a research paper would detail the experiments conducted to validate the proposed approach. It would present the experimental setup, including datasets used, evaluation metrics, and baselines for comparison. Results would be presented with statistical significance measures (e.g., confidence intervals or p-values). The discussion should highlight key findings, emphasizing whether the proposed method outperforms baselines and to what extent. Limitations of the experiments (e.g., dataset size, specific settings) and their potential impact on the generalizability of results should be acknowledged. A robust empirical study section is crucial to establishing the validity and practical relevance of the research, providing strong evidence to support the claims made in the introduction. Visualizations such as graphs and tables are vital to clearly present complex results and aid in understanding the findings. The section should provide sufficient detail to allow readers to understand the experiments, reproduce the results, and draw informed conclusions.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper on Trace, a novel framework for computational workflow optimization, presents exciting avenues for enhancing its capabilities and addressing limitations. Improving LLM reasoning through techniques like Chain-of-Thought prompting, few-shot learning, and tool use is crucial for OptoPrime’s efficiency. Developing a hybrid workflow that combines LLMs and search algorithms could lead to a truly general-purpose optimizer. Addressing scalability challenges remains paramount; OptoPrime’s current reliance on LLM queries limits its capacity for very large-scale problems. Investigating alternative propagators for efficient handling of immense computational graphs is essential, along with exploring techniques for hierarchical graph representations. Finally, expanding Trace’s functionality to encompass richer feedback mechanisms, beyond text and scalar values, is a priority for future research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

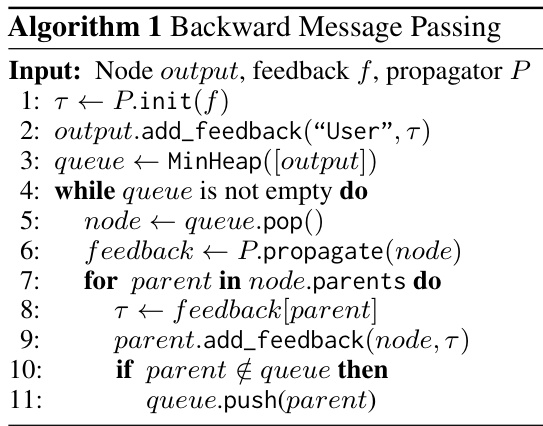

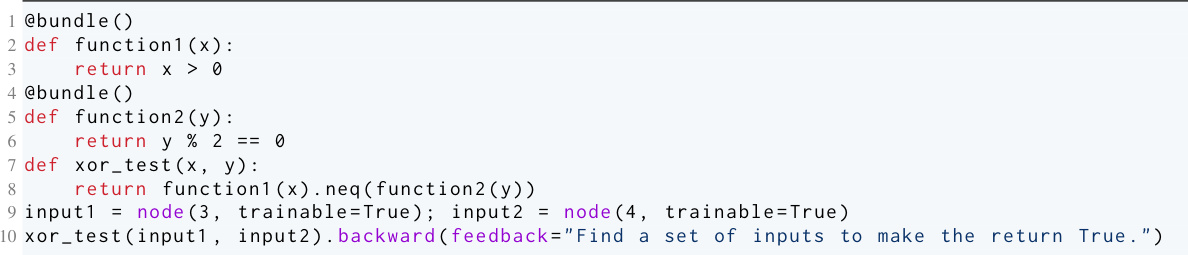

This figure shows the Python code for a Battleship example using the Trace library. It demonstrates how to define a trainable policy using Trace operators (node and bundle), setting up an optimizer with PyTorch-like syntax, and how Trace automatically records the workflow execution as a directed acyclic graph (DAG). The figure highlights the simplicity and ease of use of the Trace framework for building self-adapting agents, requiring only minimal code annotations.

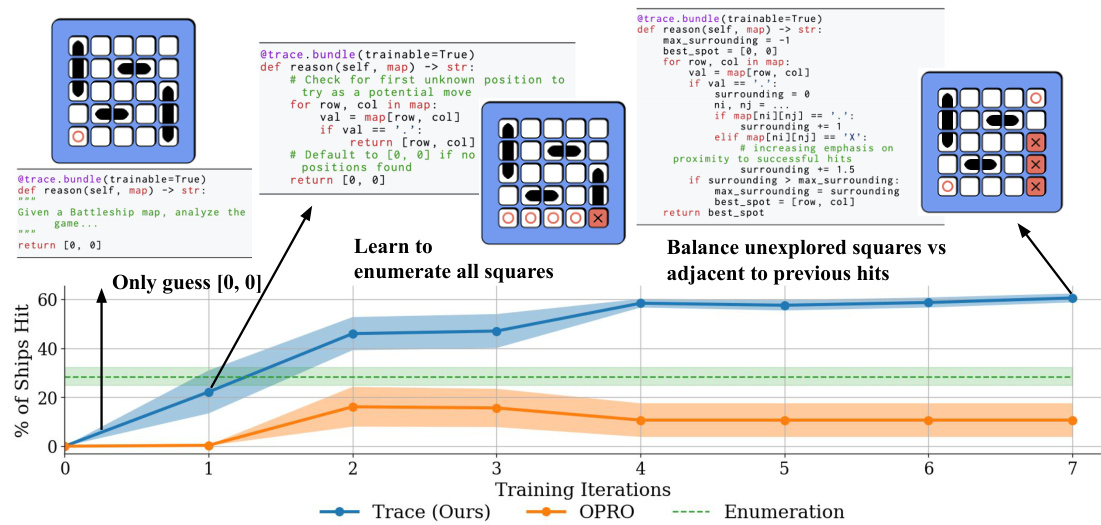

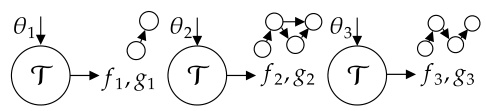

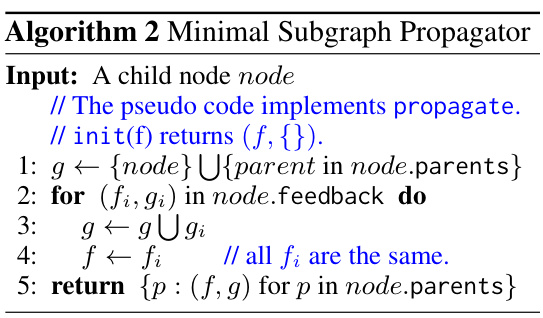

This figure illustrates the iterative process of Optimization with Trace Oracle (OPTO). In each iteration, the optimizer chooses a parameter θ from the parameter space Θ. The Trace Oracle T then provides feedback τ, consisting of a computational graph g (which uses θ as input) and feedback f (provided to the output of g). This feedback is used by the optimizer to update the parameter and proceed to the next iteration. The figure visually depicts this iterative process across three iterations, showcasing the evolving structure of the computational graph g and associated feedback f.

This figure shows an example of pseudo-code that Trace automatically generates to represent a program’s computational graph for an LLM. It includes the code, operator definitions, inputs, intermediate values, output, and feedback. The LLM uses this information to optimize the program’s parameters (here, x) to maximize z.

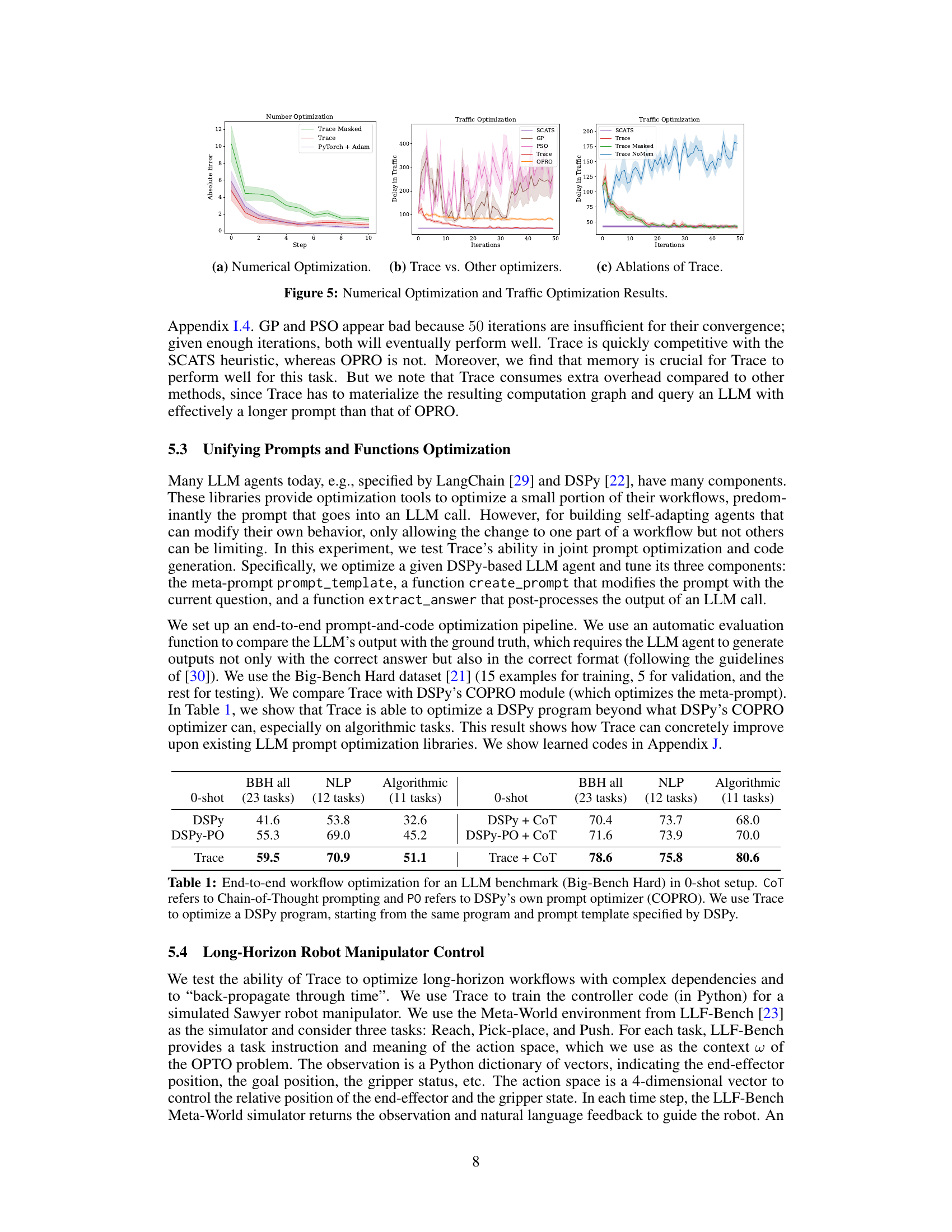

This figure presents the results of three experiments comparing Trace with other optimization methods. (a) Numerical Optimization: Shows the absolute error of numerical optimization problems solved using Trace, Trace Masked (without access to the computation graph), and Adam. Trace achieves similar performance to Adam, while Trace Masked struggles. (b) Trace vs. Other optimizers: Compares Trace’s performance in a traffic optimization task with other optimizers such as SCATS, GP, PSO, and OPRO. Trace quickly converges to a better solution than others. (c) Ablations of Trace: Demonstrates the impact of memory and access to the computational graph on Trace’s performance. OptoPrime with memory and access to the graph performs best.

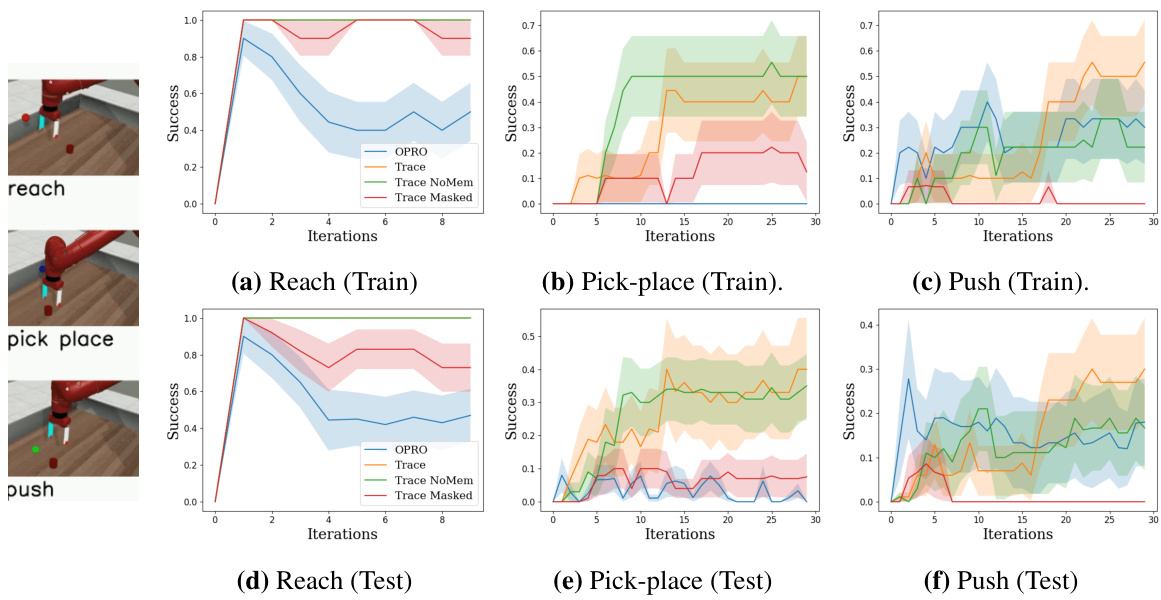

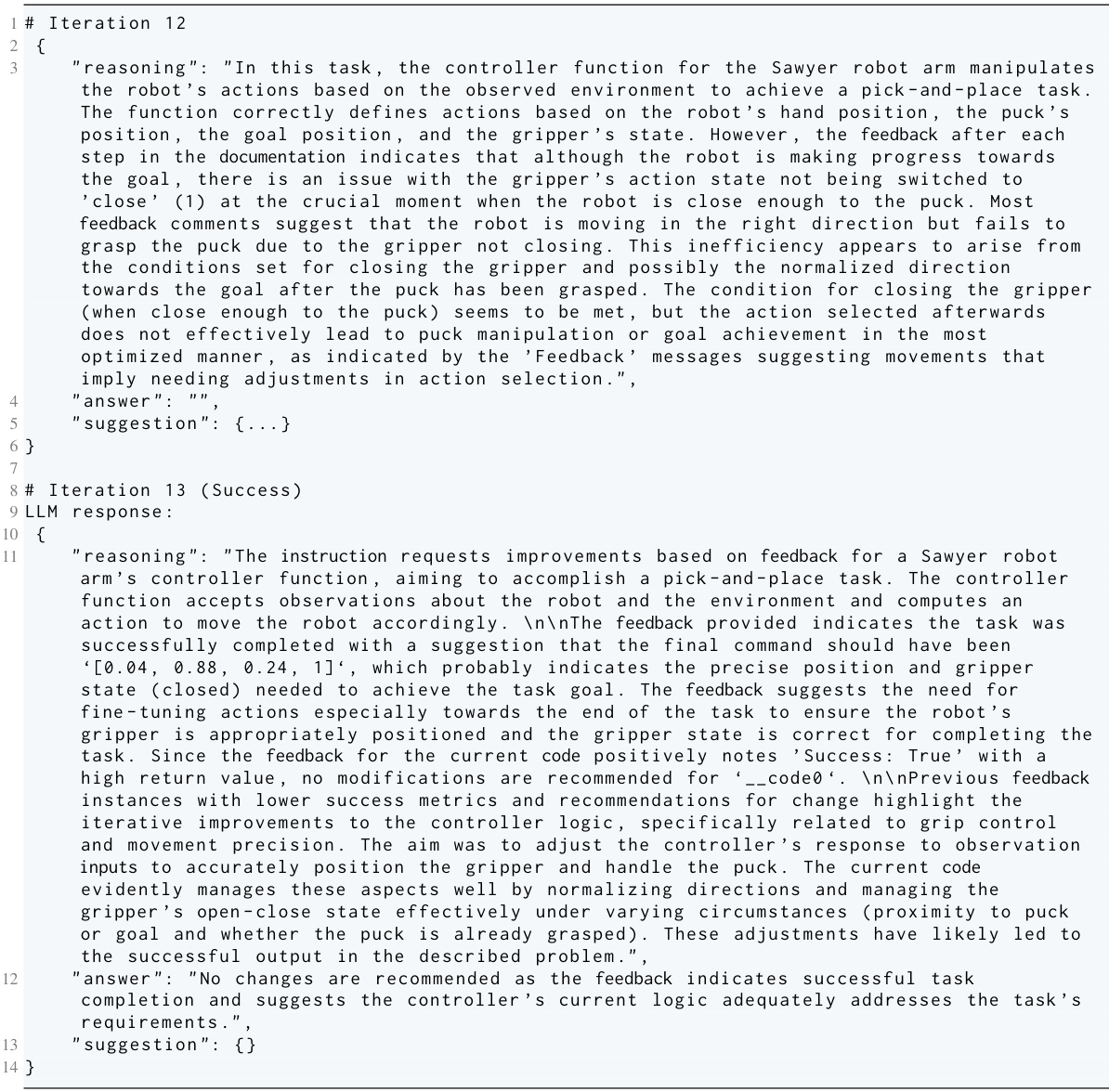

This figure displays the success rates for three different tasks (Reach, Pick-place, and Push) in a simulated robotic manipulation environment. The x-axis represents training iterations, and the y-axis shows the success rate, averaged over 10 random seeds with error bars representing the standard error. The graph compares the performance of different optimization methods (OPRO, Trace, Trace NoMem, Trace Masked). Each iteration involves running a 10-step episode and updating the robot control policy. The results illustrate how Trace, especially with memory, learns more effectively than other approaches.

This figure illustrates how Trace represents the computational workflow as a pseudo-algorithm problem. The subgraph is shown as code execution with information about computed values and operator descriptions. The LLM uses this information to update the parameters based on feedback given to the output. It highlights that while the code representation looks like a real program, it’s actually a representation of the computational graph.

This figure shows the results of training a Battleship-playing AI agent using the Trace framework. The x-axis represents training iterations, and the y-axis shows the percentage of ships hit. The figure demonstrates that Trace successfully optimizes multiple code components (heterogeneous parameters) of the AI agent to achieve improved performance in the game. Error bars represent the standard error over 10 different random seeds, showcasing the stability of the results.

This figure shows an example of using Trace to optimize a Battleship-playing AI agent. The agent’s policy consists of multiple code components that are optimized simultaneously by Trace. The x-axis represents training iterations, while the y-axis shows the percentage of ships hit. The plot demonstrates how Trace improves the agent’s performance over time by optimizing the different code components, ultimately leading to a higher success rate in hitting the ships.

This figure shows the result of applying the Trace optimizer to a Battleship game. The x-axis represents the number of training iterations, and the y-axis shows the percentage of ships hit. The plot shows that the Trace optimizer successfully learns to improve the agent’s policy (represented by multiple codes which are automatically updated) over time, leading to a higher percentage of ships hit. Error bars indicating standard deviation are included in the plot.

This figure shows an example of how Trace optimizes a Battleship-playing agent. The agent’s policy consists of multiple code components (‘reason’ and ‘act’) which are optimized by Trace. The x-axis shows the number of training iterations, and the y-axis shows the percentage of ships hit. The graph demonstrates how Trace improves the agent’s performance over time by automatically adjusting the agent’s code, resulting in a higher percentage of ships hit.

This figure shows the results of training an AI agent to play the game Battleship using the Trace framework. The x-axis represents the number of training iterations, and the y-axis shows the percentage of ships hit. The graph demonstrates that the Trace optimizer successfully learns to improve the agent’s performance over time by automatically optimizing different code variations (heterogeneous parameters) for the agent’s reasoning and action components. Error bars represent the standard error across 10 different random seeds, illustrating the consistency and reliability of the learning process.

This figure shows the results of using Trace to train an AI agent to play the game Battleship. The agent’s policy is composed of multiple code components that are treated as heterogeneous parameters and are optimized by Trace. The graph displays the percentage of ships hit by the agent over the course of training iterations. The mean and standard deviation of this success rate over 10 independent runs are presented, illustrating the effectiveness of Trace in optimizing the code to learn an effective Battleship strategy.

This figure shows the results of training a Battleship-playing AI agent using the Trace framework. The x-axis represents the number of training iterations, and the y-axis represents the percentage of ships hit. The figure demonstrates that Trace effectively optimizes multiple code snippets (heterogeneous parameters) to improve the agent’s performance over time. The error bars indicate standard errors calculated across 10 different random seeds.

This figure demonstrates the results of applying Trace, a novel optimization framework, to a Battleship game. The goal is to train an AI agent to play Battleship effectively. The key point is that Trace optimizes multiple heterogeneous parameters simultaneously: in this case, different versions of the agent’s ‘reason’ and ‘act’ code. The graph shows how the percentage of ships hit improves over training iterations. Each point represents the mean performance across 10 different random seeds, illustrating the robustness and efficiency of Trace.

More on tables

This table presents the number of tokens used by OPRO and OptoPrime in different optimization tasks, including numerical optimization, BigBench-Hard, traffic optimization, Meta-World, and Battleship. The token count reflects the input prompt length given to the respective LLMs, revealing that OptoPrime consistently uses more tokens than OPRO. This difference is attributed to OptoPrime’s reliance on the more information-rich execution trace feedback, which is not used in OPRO.

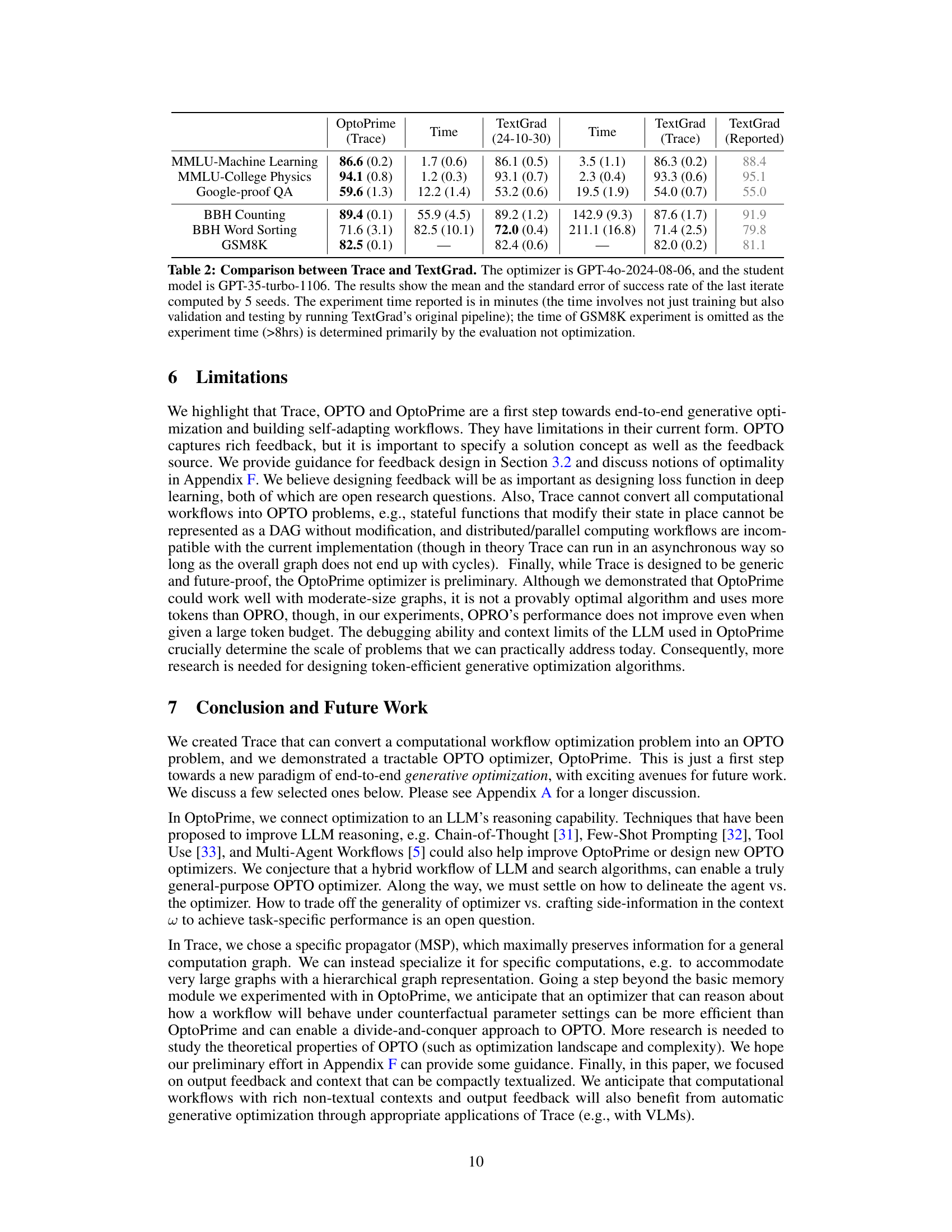

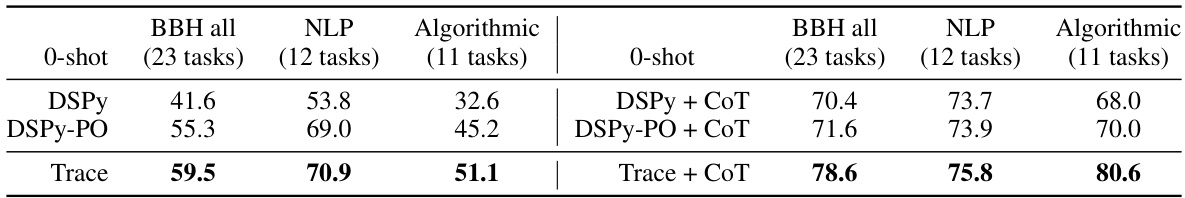

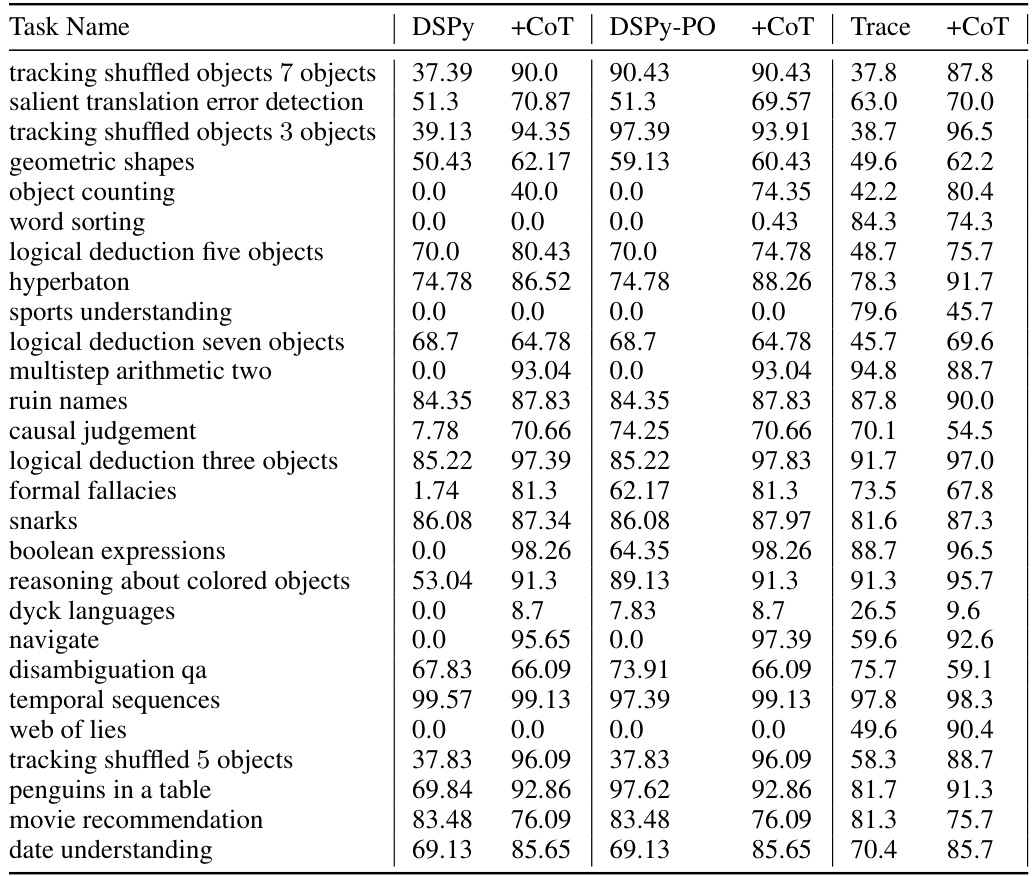

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing different methods for optimizing large language model (LLM) workflows using the Big-Bench Hard benchmark. It shows the performance (accuracy) of three methods (DSPy, DSPy with Chain-of-Thought prompting, and Trace) in three categories of tasks (all tasks, natural language processing tasks, and algorithmic tasks). The results demonstrate that the Trace method, which uses the novel optimization approach introduced in the paper, achieves superior performance compared to the other methods, especially on algorithmic tasks.

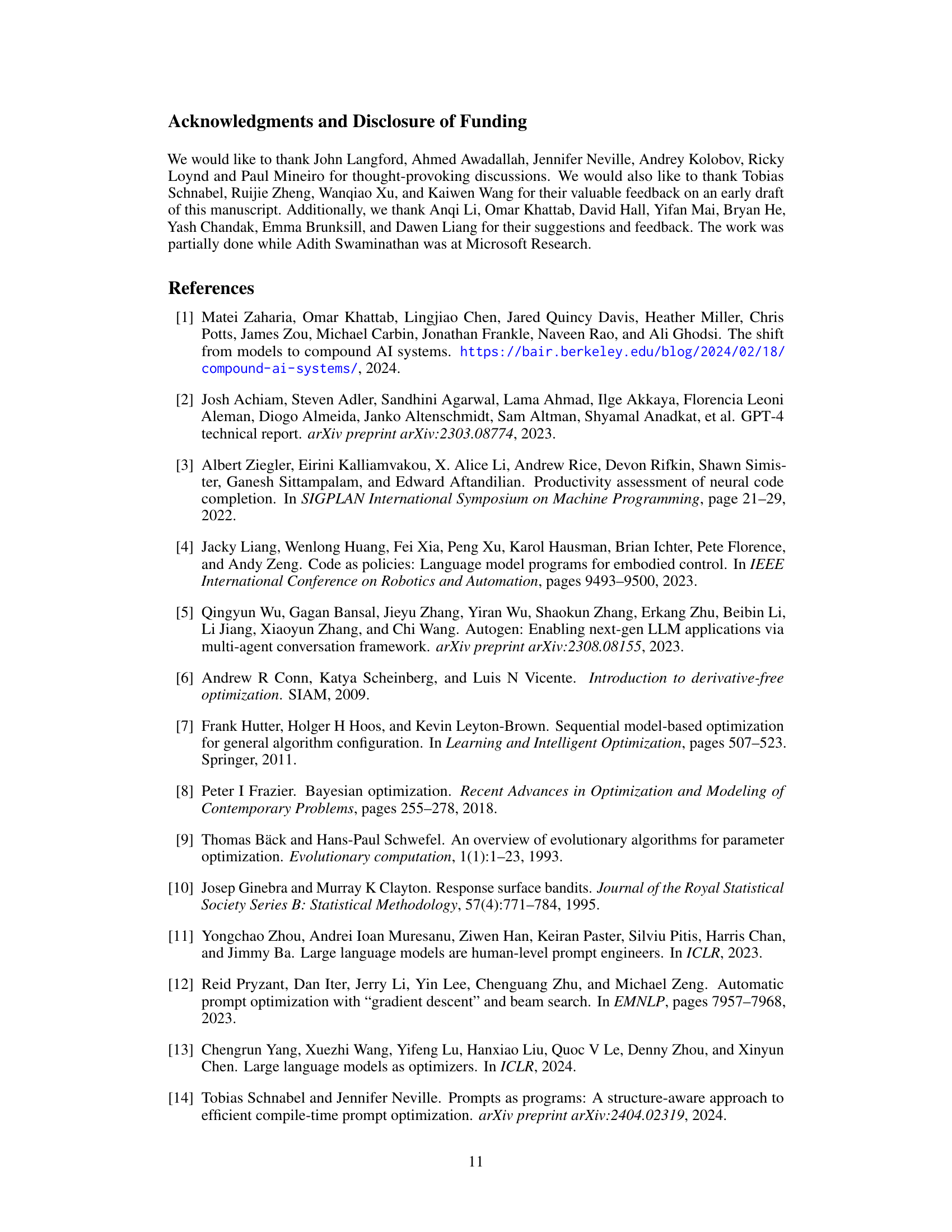

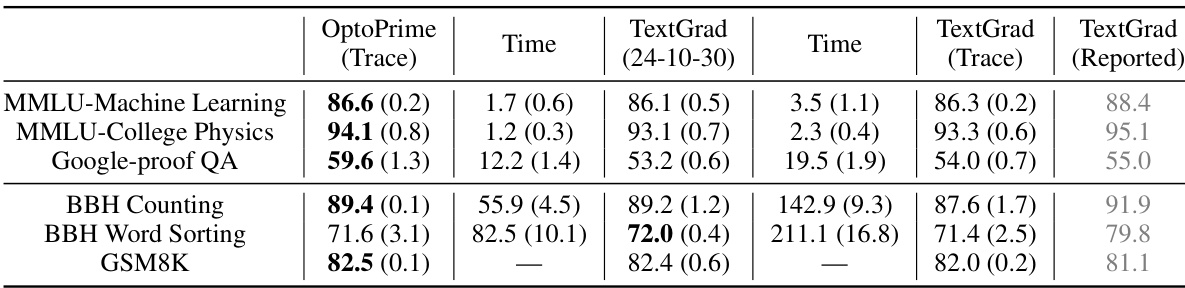

This table compares the performance of Trace and TextGrad on several tasks. It shows the mean and standard error of success rates, along with the time taken for optimization. Note that TextGrad’s time includes validation and testing.

This table shows the number of tokens used in the prompts for OPRO and OptoPrime in different experiments. It highlights the significantly higher token usage of OptoPrime compared to OPRO, but emphasizes that despite this higher token cost, OptoPrime’s performance surpasses OPRO’s even when OPRO is allowed many more iterations (thus equalizing the overall token expenditure). The difference is attributed to OptoPrime’s more informative use of the Trace oracle.

This table shows the number of tokens consumed by the OPRO and OptoPrime prompts across different experimental domains. OptoPrime consistently uses more tokens than OPRO, but achieves superior performance even when OPRO is given many more iterations to use a comparable number of tokens.

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing different methods for optimizing an LLM workflow on the Big-Bench Hard dataset. It shows the performance (accuracy) achieved by various methods: DSPy, DSPy with Chain-of-Thought prompting (CoT), DSPy-PO (DSPy’s own prompt optimizer), DSPy-PO with CoT, Trace, and Trace with CoT. The results are broken down by task type (NLP, algorithmic, and overall) to provide more granular insights into how different approaches perform across various complexities.

This table compares the performance of different optimization methods on the Big-Bench Hard benchmark, a dataset of challenging tasks for large language models. It specifically looks at optimizing a workflow implemented using the DSPy library. The methods compared include DSPy’s own prompt optimizer (COPRO), DSPy with Chain-of-Thought prompting, and Trace (the proposed method in the paper) with and without Chain-of-Thought prompting. The results show the accuracy achieved by each method on different categories of tasks within the benchmark: NLP, algorithmic, and a combined set of all tasks.

Full paper#