↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current methods for automated planning using LLMs often struggle with the accuracy of translating natural language problem descriptions into the Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL). Inaccuracies in PDDL translation can lead to incorrect or infeasible plans, highlighting the need for a more robust approach. Existing techniques frequently require significant human intervention for accurate PDDL generation, limiting their scalability and applicability.

This paper introduces a novel fully automated method that uses LLMs and environment interaction to generate PDDL domain and problem files iteratively. It leverages the Exploration Walk (EW) metric to smoothly measure the similarity between generated and ground-truth PDDL domains. The EW-guided iterative refinement process enables the LLM to learn from environmental feedback, significantly improving the accuracy of PDDL translation. The proposed approach demonstrates promising results, achieving a 66% average solve rate on ten challenging benchmark environments, surpassing previous approaches that rely on human intervention.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI planning and Large Language Models (LLMs). It bridges the gap between LLM’s flexibility and classical planners’ accuracy by introducing a novel method that automates PDDL translation and planning using LLM and environment interaction. This work addresses a critical challenge in AI planning, paving the way for more robust and efficient automated planning systems and opening new research directions in LLM-based planning.

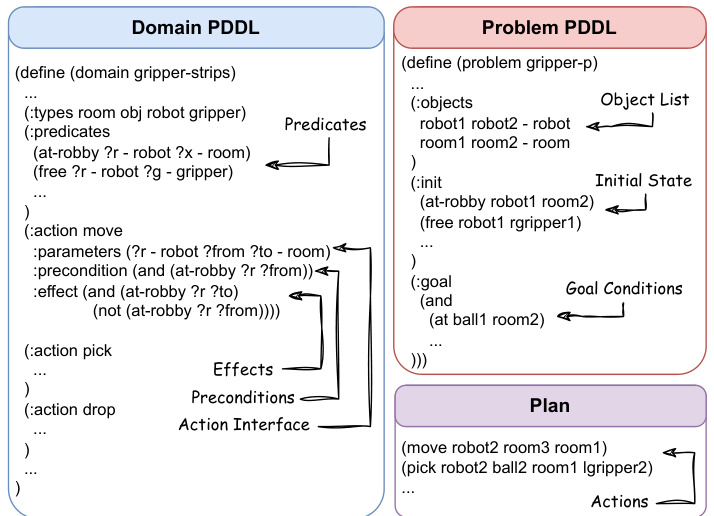

Visual Insights#

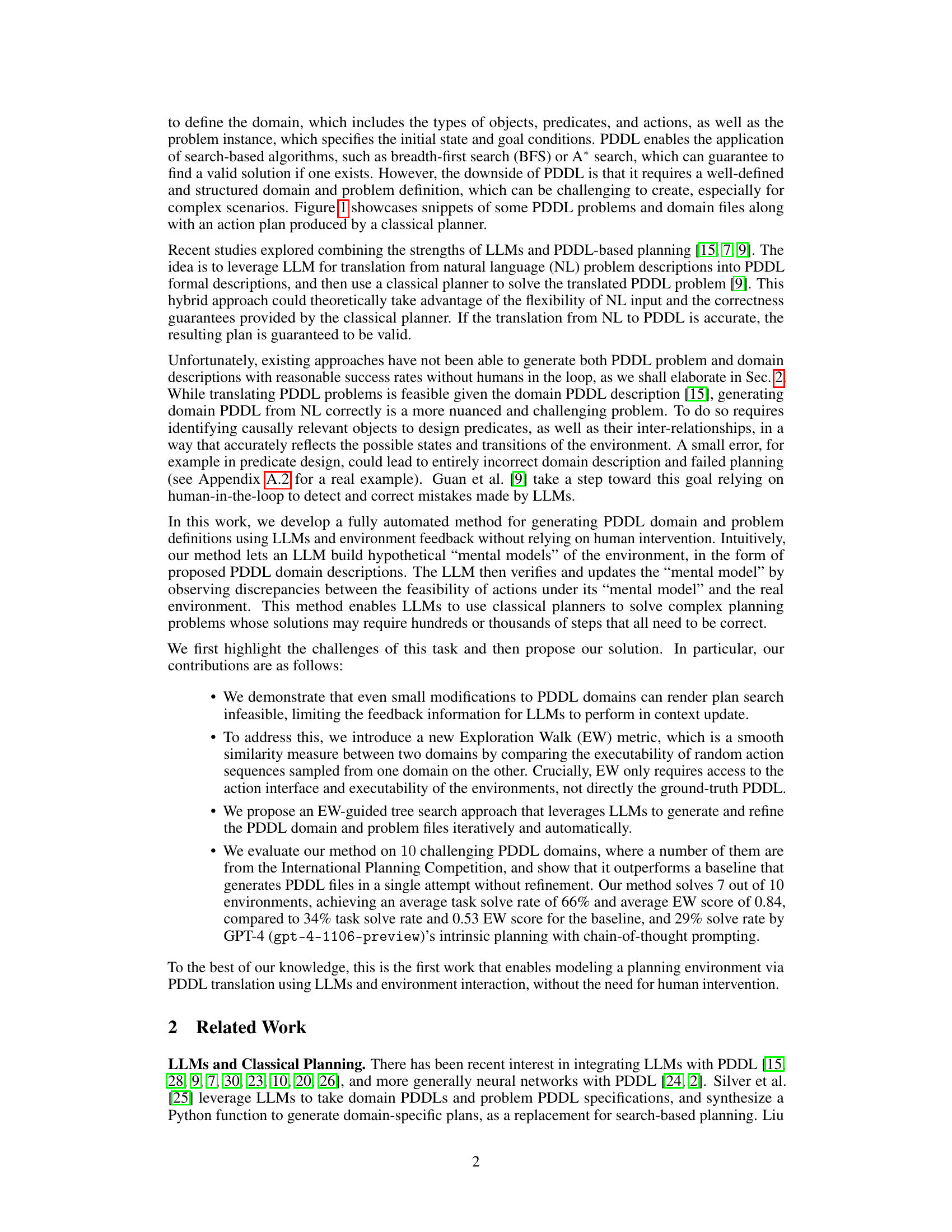

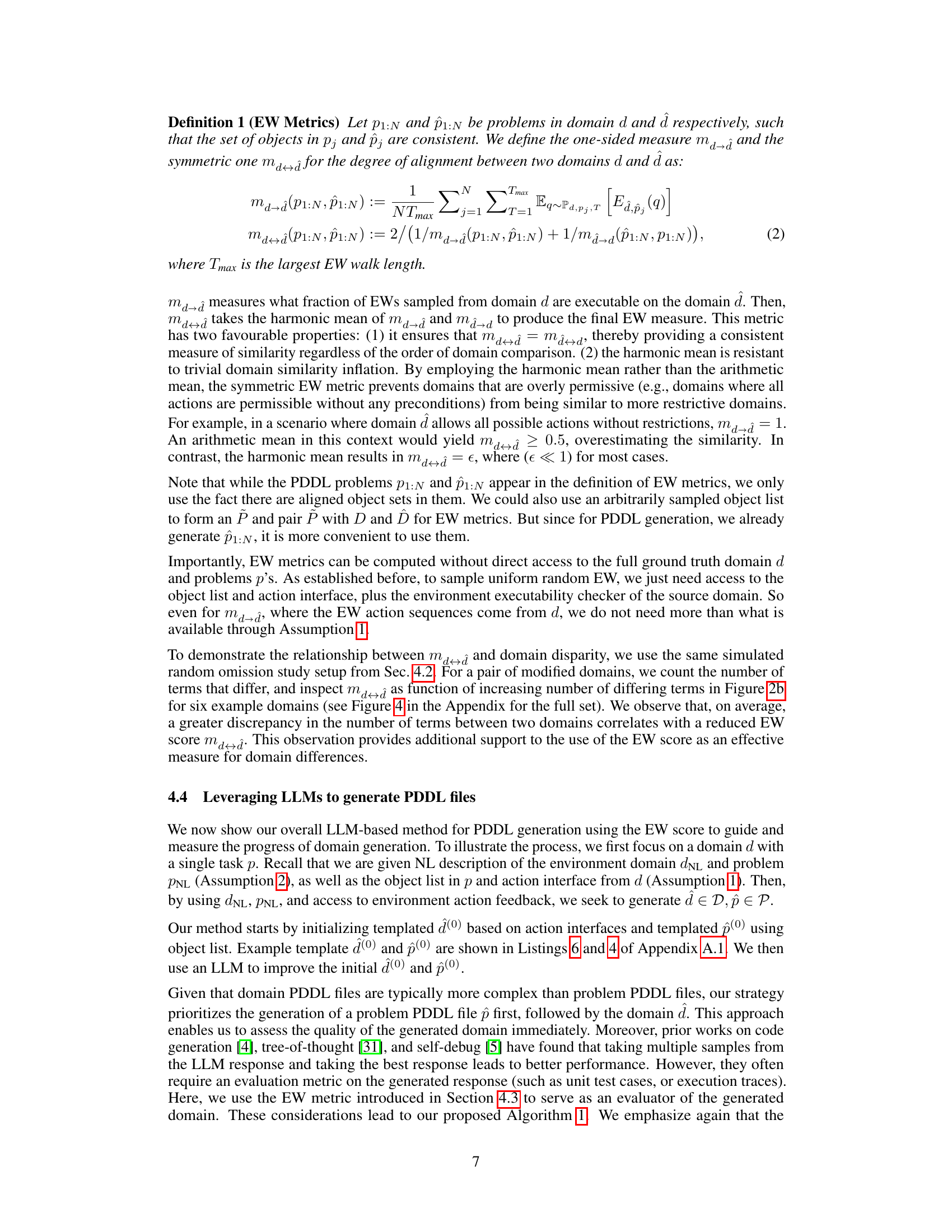

This figure shows example snippets of PDDL code for a domain, problem, and plan. The domain defines predicates (object properties), actions (operations), preconditions (requirements for actions), and effects (results of actions). The problem describes the initial state and goal state of a planning problem. Finally, the plan shows a sequence of actions that achieves the goal state, satisfying preconditions of each action.

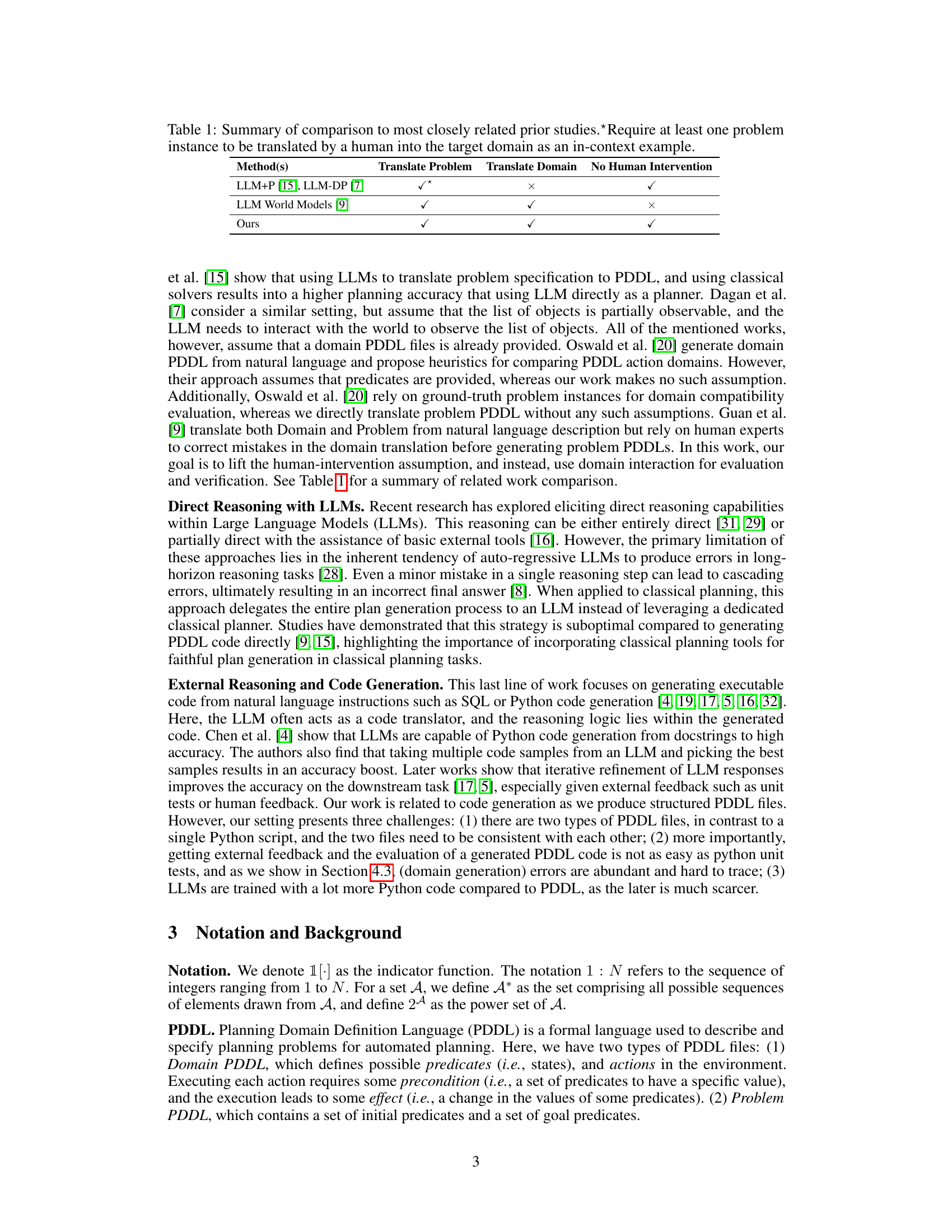

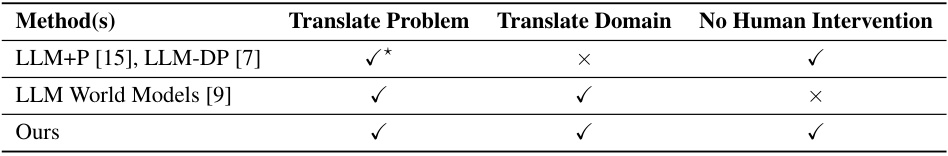

This table compares the proposed approach with three other related studies in terms of their ability to translate planning problems and domains from natural language into PDDL (Planning Domain Definition Language) and whether human intervention is required in the translation process. The table highlights that the proposed method is unique in its ability to achieve both problem and domain translation automatically without human intervention.

In-depth insights#

LLM Planning Limits#

LLMs demonstrate impressive capabilities in various natural language tasks, yet their application to planning reveals significant limitations. Their inherent lack of structured reasoning and reliance on pattern-matching often hinders their ability to solve complex planning problems that demand logical inference and long-horizon reasoning. While chain-of-thought prompting has shown some improvement, LLMs struggle with tasks requiring intricate state transitions, complex action dependencies, and robust error handling. The difficulty of accurately translating natural language planning problems into formal languages like PDDL, further exacerbates these challenges. LLMs’ susceptibility to generating hallucinated or nonsensical plans highlights the need for external verification mechanisms and reliable feedback loops during the planning process. Moreover, the lack of inherent world models within LLMs necessitates the integration of environmental interaction to ground LLM-based planning in reality. Overcoming these limitations requires advances in LLM architecture, prompting strategies, and the development of robust integration methods with external planners and environment simulators.

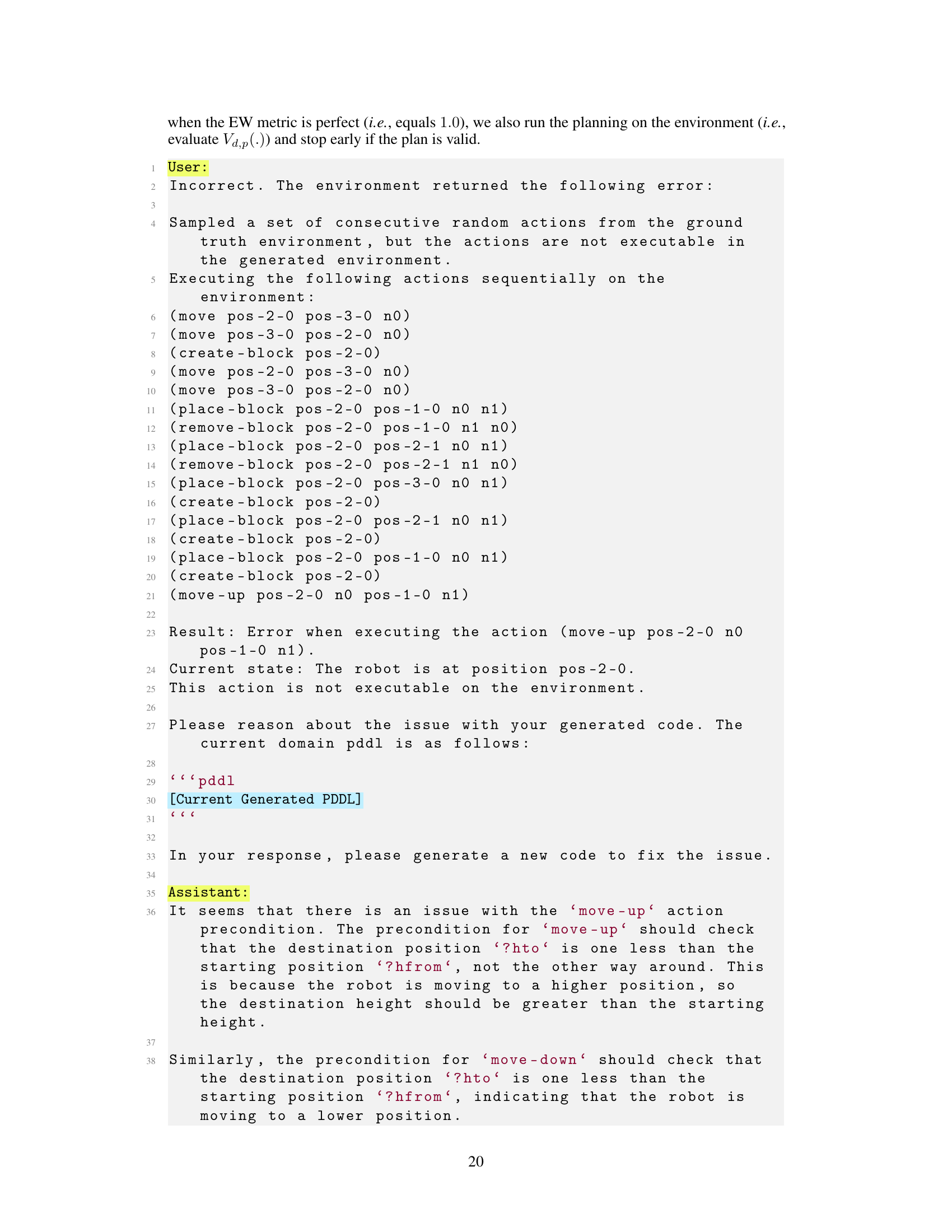

Environment Feedback#

The concept of ‘Environment Feedback’ in the context of automated PDDL translation and planning using LLMs is crucial. It bridges the gap between the LLM’s hypothetical model of the environment and the real-world dynamics. Instead of relying on potentially unreliable or unavailable human feedback, the system directly interacts with the environment. This interaction provides rich, actionable feedback, allowing the LLM to iteratively refine its PDDL representation. The iterative refinement process, guided by metrics such as Exploration Walk (EW), is a key strength, enabling the LLM to progressively correct inaccuracies and improve the model’s fidelity. This approach is particularly valuable because minor errors in PDDL can render plan search infeasible. Environment feedback provides a smooth and continuous mechanism for updating the model, leading to more robust and reliable automated planning, surpassing intrinsic LLM planning methods. The success hinges on the system’s ability to interpret environmental responses and translate them into meaningful updates to the PDDL. This technique has significant potential for automating planning tasks in complex environments where human input may be costly or impractical.

PDDL Auto-Gen#

The hypothetical heading ‘PDDL Auto-Gen’ suggests a research focus on automating the generation of Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL) files. This is a significant challenge in AI planning, as manually creating PDDL files is time-consuming and error-prone. An effective ‘PDDL Auto-Gen’ system would likely leverage techniques from Natural Language Processing (NLP) and machine learning to translate high-level descriptions of planning problems or domains into formal PDDL representations. Key considerations would include the accuracy of the generated PDDL, its completeness in capturing the problem’s constraints, and the efficiency of the generation process. The system’s robustness to noisy or incomplete inputs would also be crucial. Furthermore, a successful ‘PDDL Auto-Gen’ approach could dramatically improve the usability and scalability of AI planning techniques, enabling them to be applied to more complex real-world problems. A deeper dive into such a system may reveal insights into the interplay between symbolic AI planning and the power of large language models or other advanced NLP methods.

Exploration Walk#

The concept of “Exploration Walk” presents a novel approach to address the limitations of using Large Language Models (LLMs) for automated PDDL (Planning Domain Definition Language) generation. It cleverly leverages environment interaction to provide rich feedback signals for the LLM, overcoming the challenges posed by the brittleness of PDDL and the lack of informative feedback when planning fails. By introducing an iterative refinement process guided by an exploration walk metric that measures the similarity between two PDDL domains, the approach avoids the need for human intervention. The Exploration Walk metric itself is ingenious, providing a smooth similarity measure without requiring access to ground-truth PDDLs, making it particularly useful in scenarios where ground truth is unavailable or expensive to obtain. This iterative refinement process, coupled with a smooth similarity metric, shows considerable promise in improving the reliability and robustness of LLM-based planning agents, significantly advancing the automated PDDL translation process.

Future Work#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the Exploration Walk (EW) metric is crucial; a more sophisticated method, perhaps incorporating reinforcement learning techniques, could significantly enhance its efficiency and robustness. Extending the framework beyond PDDL environments would broaden its applicability to more diverse planning scenarios. Investigating more advanced LLM prompting strategies, such as chain-of-thought prompting or tree-of-thought prompting, could improve the quality of PDDL generation. Thorough investigation of different LLM architectures and their suitability for this task is needed. Finally, and importantly, addressing the challenges of scaling to more complex environments is crucial for real-world applications. The current approach’s scalability limits its utility in larger-scale applications. Addressing these limitations will unlock the full potential of this LLM-based automated planning approach.

More visual insights#

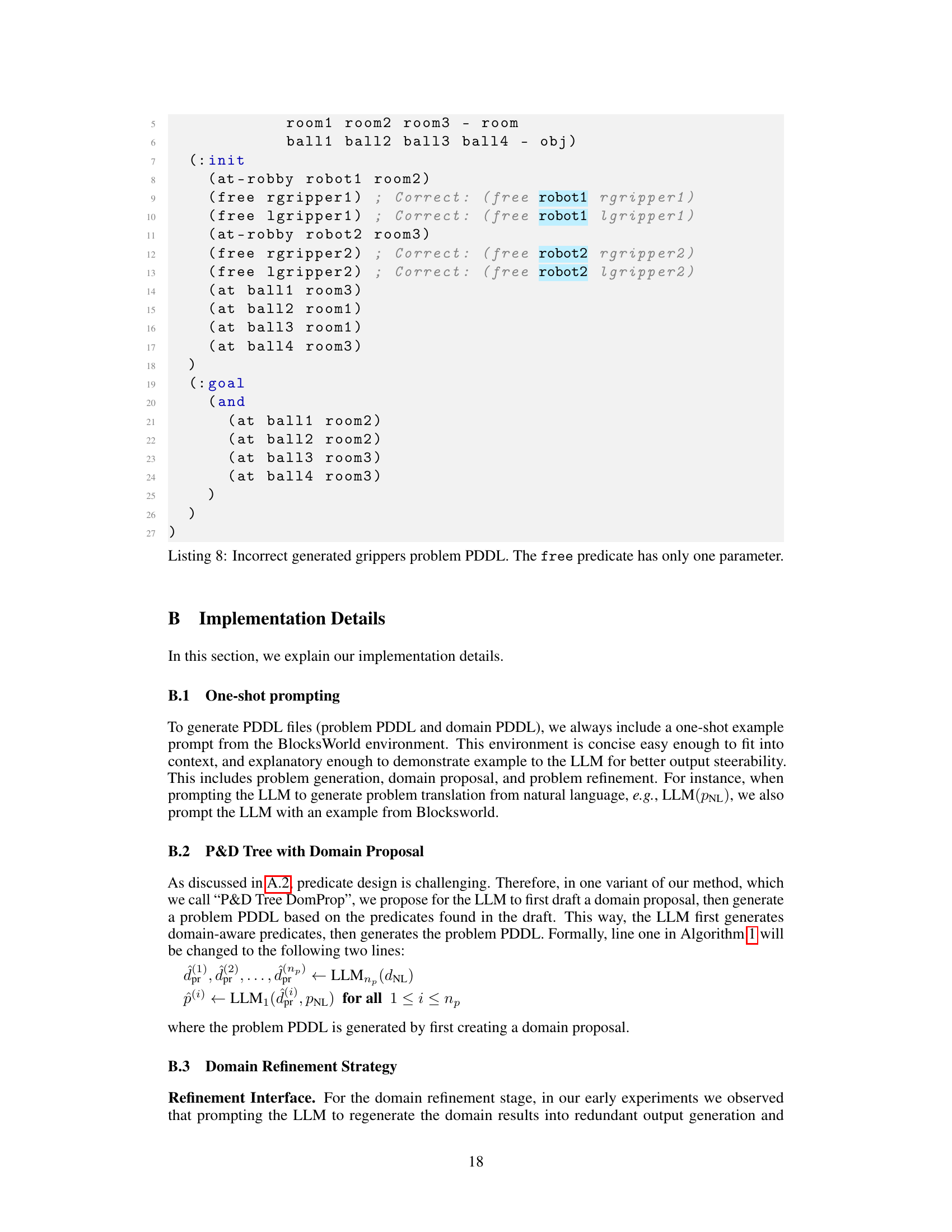

More on figures

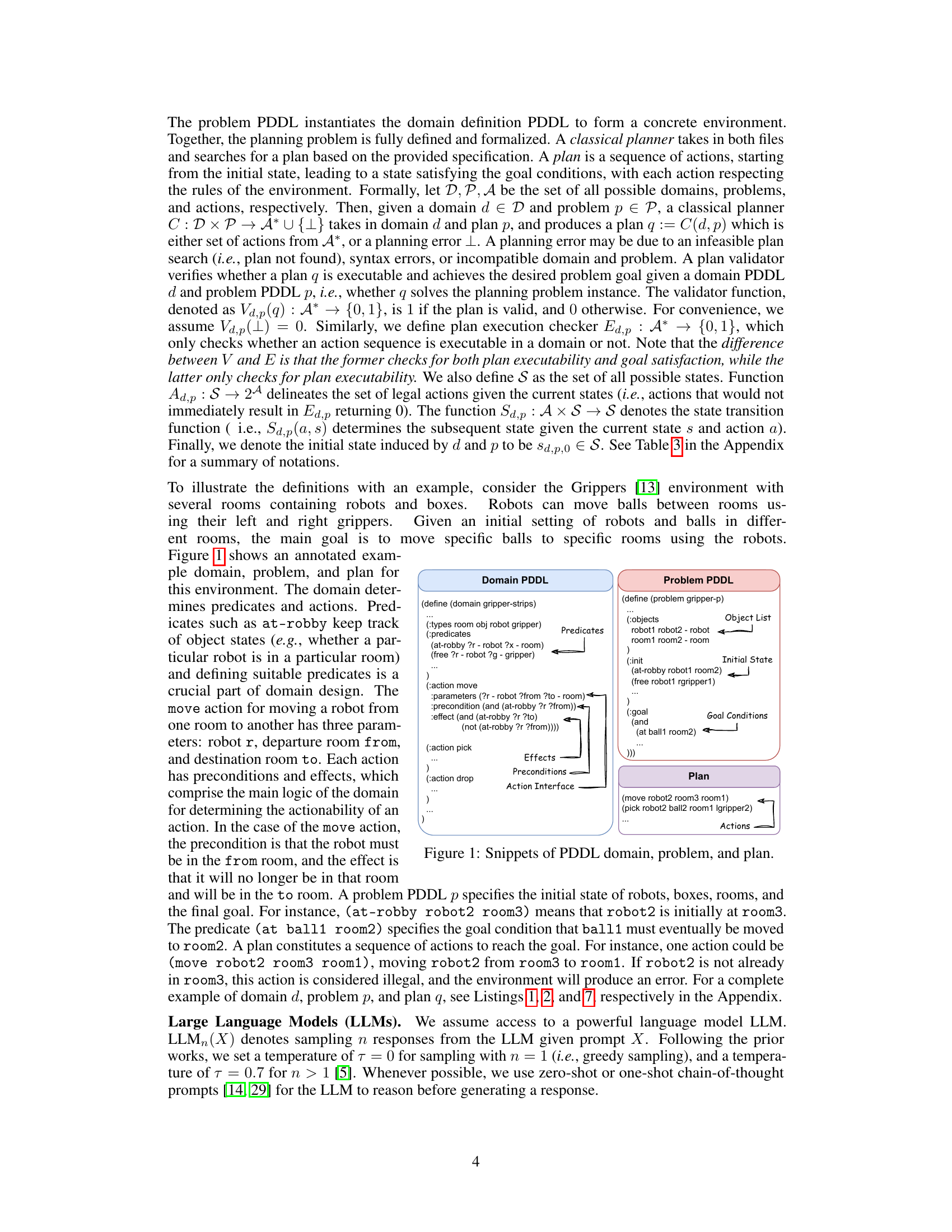

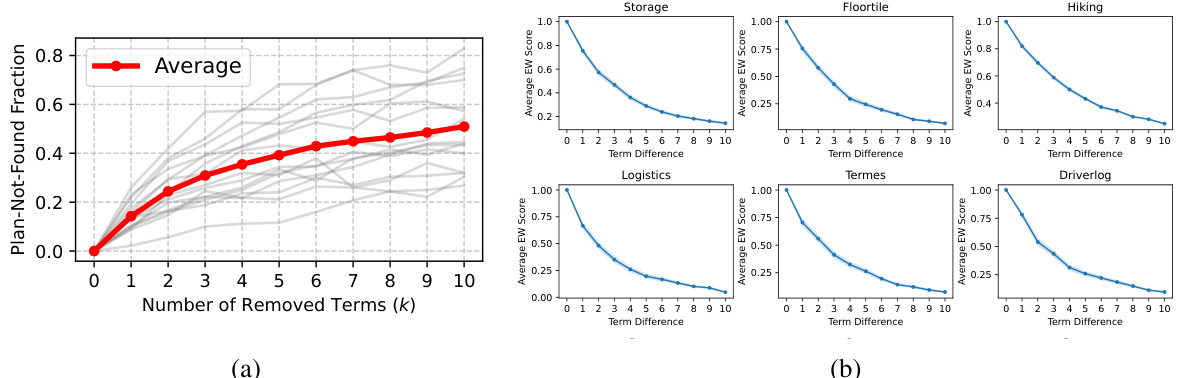

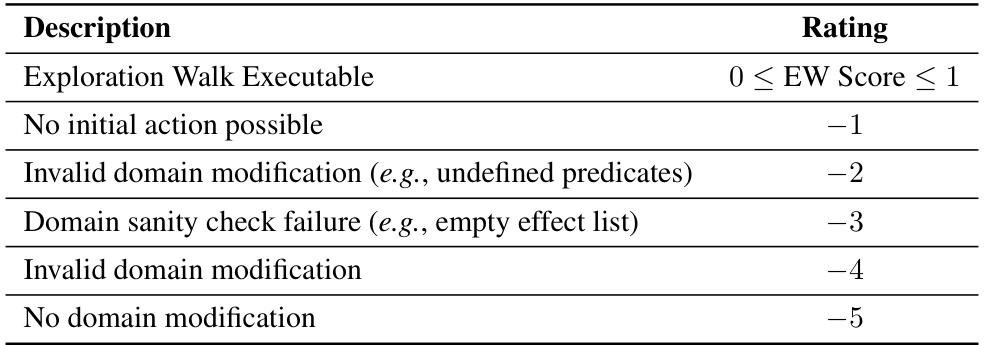

Figure 2(a) shows how sensitive the planning process is to small changes in the PDDL domain. Removing even a few terms significantly increases the likelihood of plan search failure. Figure 2(b) demonstrates the correlation between the Exploration Walk (EW) metric (measuring domain similarity) and the number of differing terms between two domains. The EW score consistently decreases as the number of differing terms increases, making EW a reliable measure of domain dissimilarity.

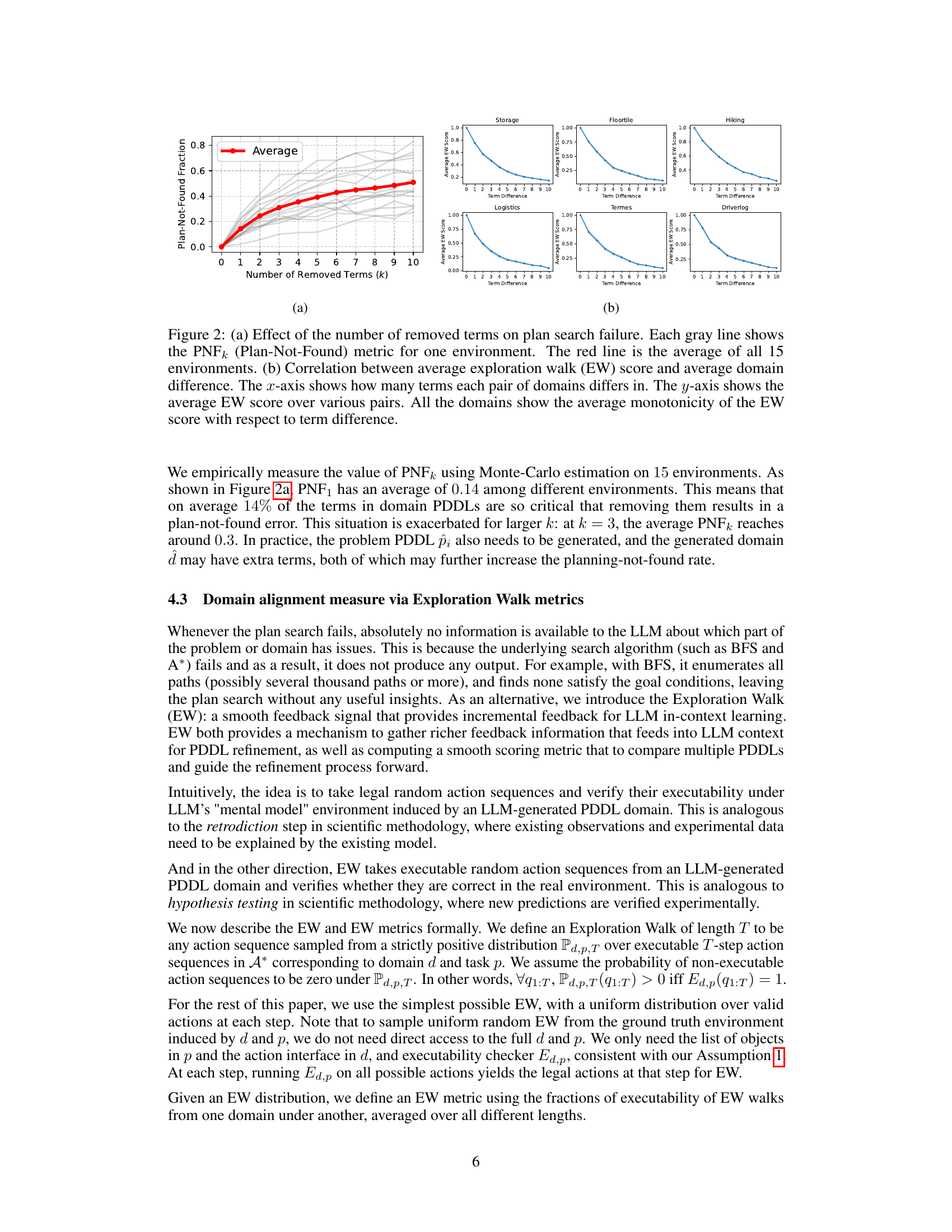

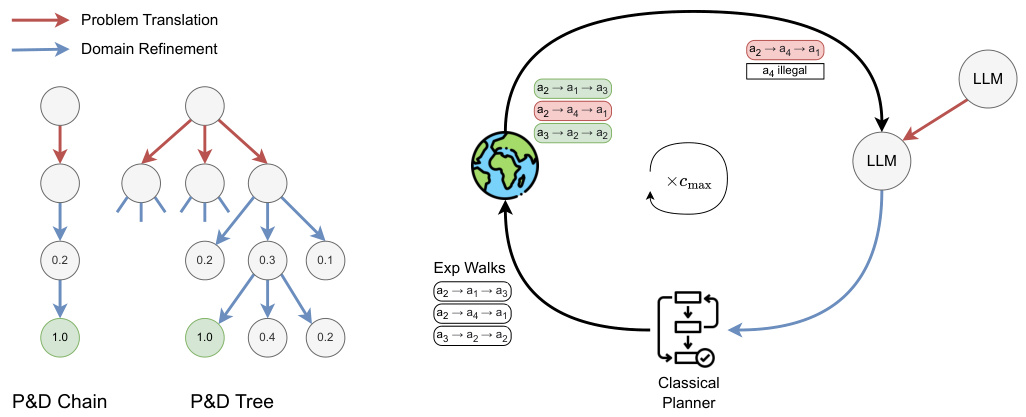

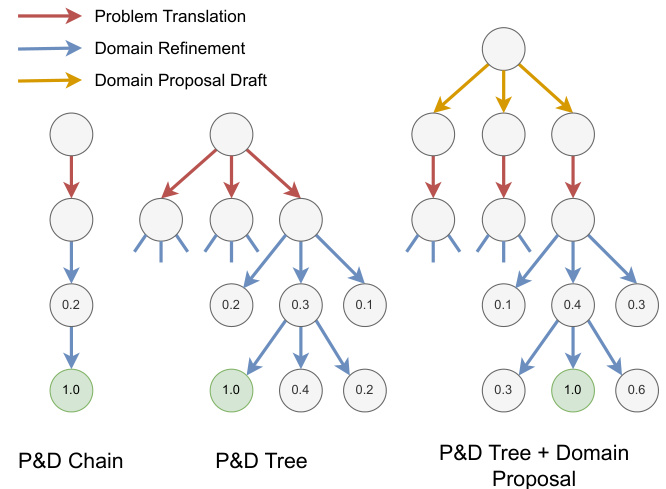

This figure illustrates the proposed method for automated PDDL translation and planning using LLMs and environment interaction. The right side shows the iterative refinement process, starting with natural language descriptions translated into problem PDDLs by an LLM. This is followed by domain generation and refinement through cycles of exploration walks, classical planning, and LLM feedback. The left side illustrates how the iterative refinement process on the right corresponds to single paths within the tree structures shown. Each node represents a state in the refinement process; red arrows denote problem translation while blue arrows indicate domain refinement.

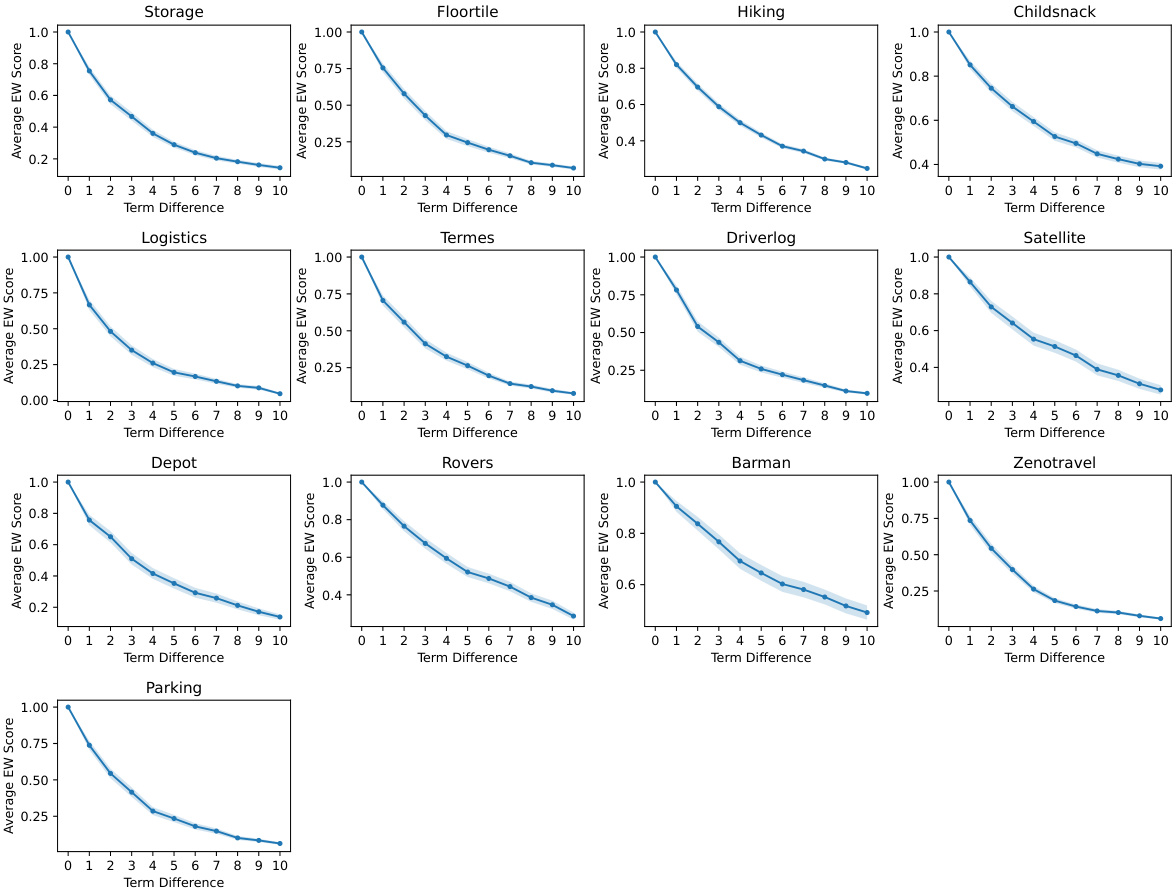

The figure shows the correlation between average exploration walk (EW) score and average domain difference across various PDDL domains. The x-axis represents the number of terms that differ between pairs of domains, while the y-axis represents the average EW score. Each line corresponds to a different domain, and the red line represents the average across all domains. The plot demonstrates that as the term difference increases, the average EW score decreases, indicating a strong negative correlation between the similarity of two domains and the number of terms that differ between them. This highlights the sensitivity of planning performance to even small changes in the domain description.

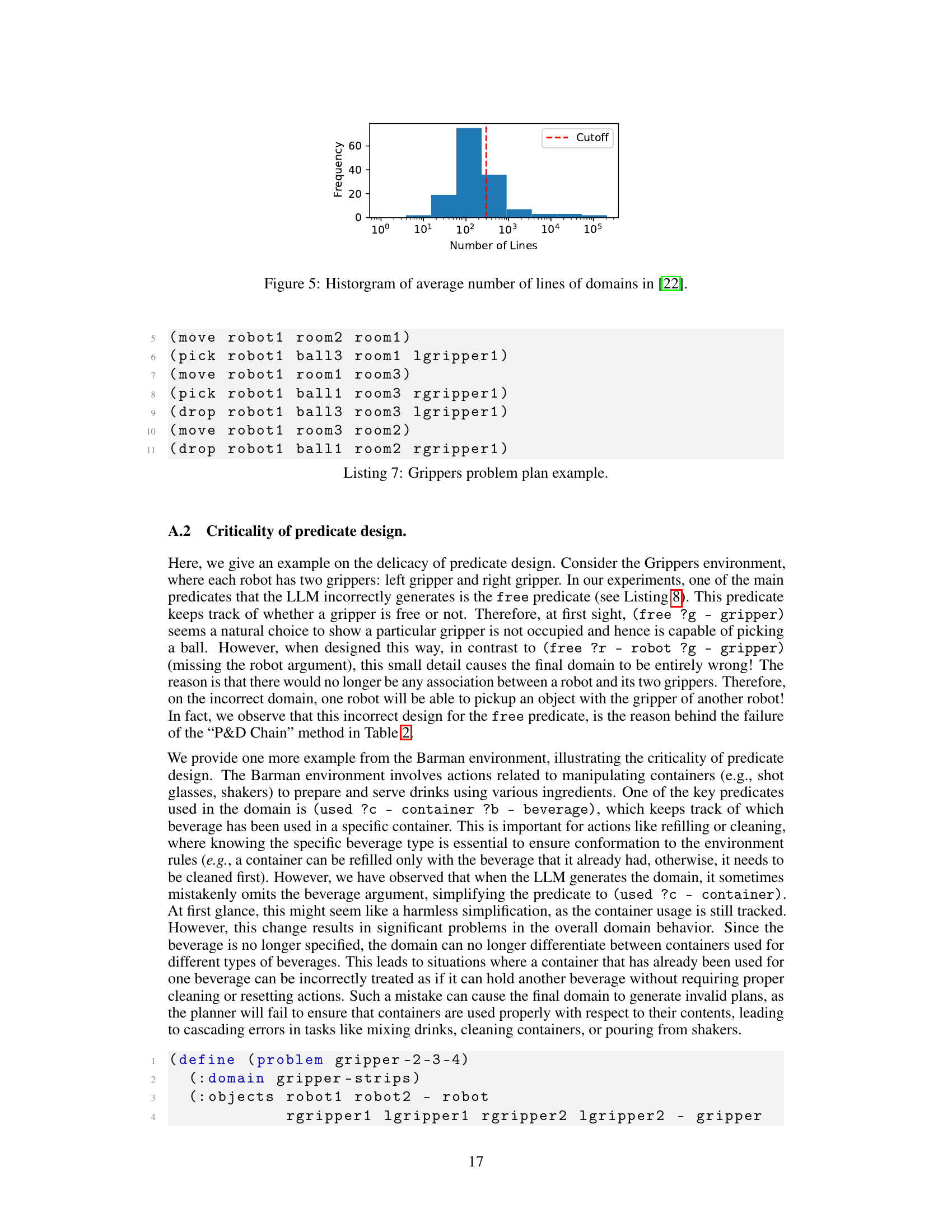

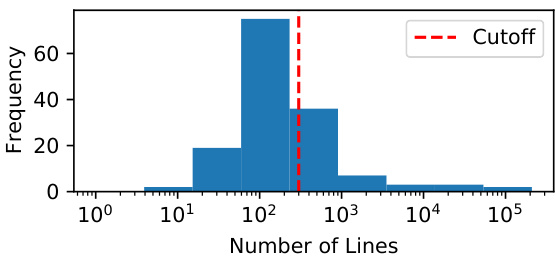

This histogram shows the distribution of the average number of lines across various PDDL domains from the International Planning Competition (IPC). The red dashed line indicates a cutoff point, likely highlighting a significant difference in complexity between smaller and larger domains. The distribution appears to be right-skewed, suggesting a larger number of smaller domains and a few significantly larger ones. This figure is relevant to understanding the challenges of automatically generating PDDL files, as the complexity of a domain directly impacts the difficulty of the task.

This figure illustrates the proposed method for automatically generating PDDL domain and problem files using LLMs and environment feedback. The right side shows the iterative refinement process using exploration walks, classical planners, and LLM feedback. The left side illustrates that the refinement process can be viewed as a tree search, with each node representing a state in the refinement process, and arrows showing problem translation and domain refinement.

More on tables

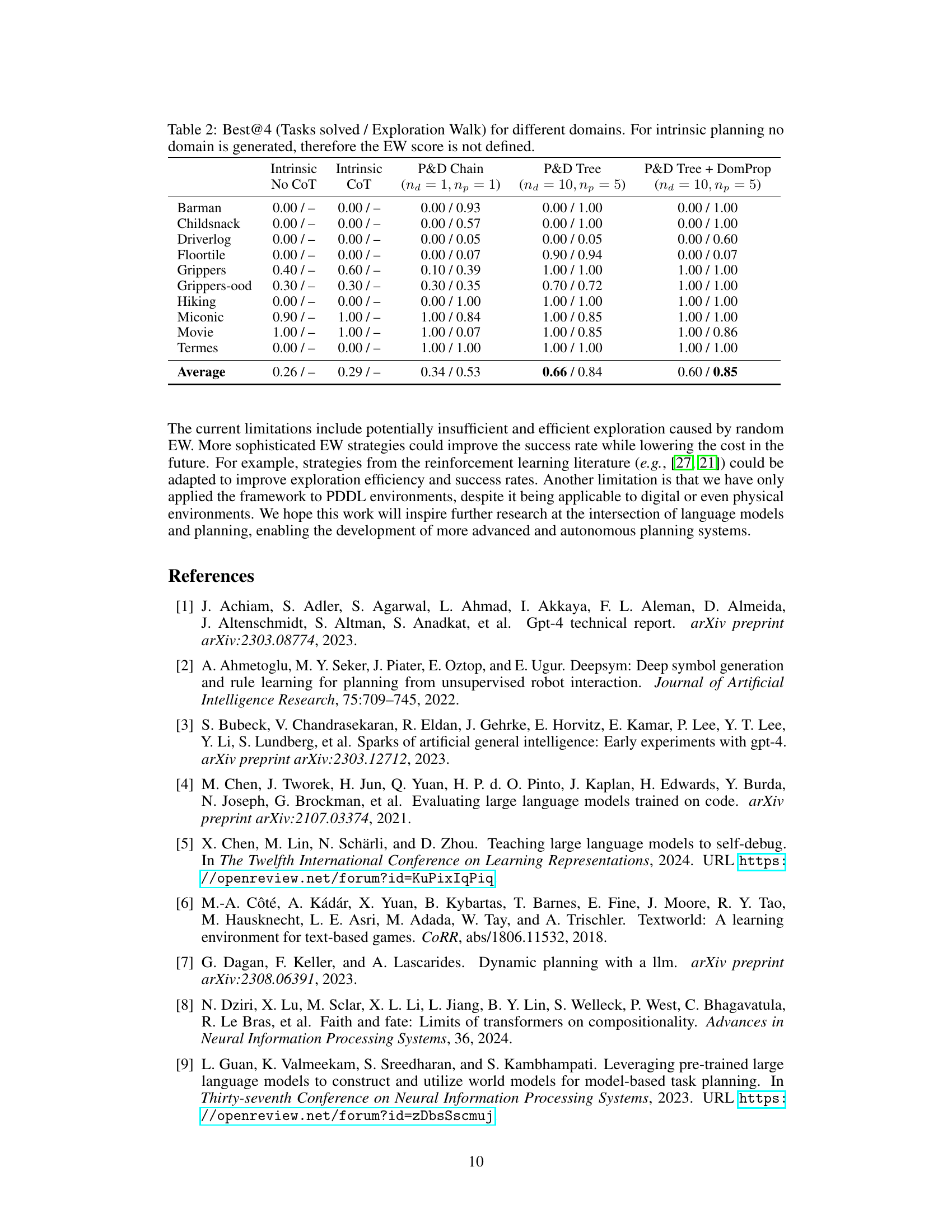

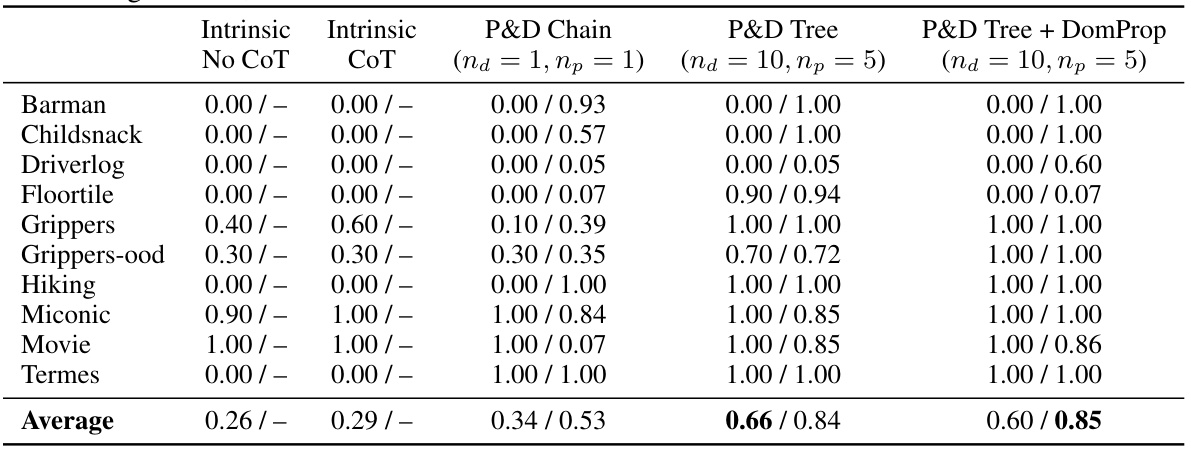

This table presents the results of experiments comparing different methods for automated PDDL translation and planning. The methods include intrinsic planning with and without chain-of-thought prompting, as well as the proposed methods (P&D Chain, P&D Tree, and P&D Tree + DomProp) with varying numbers of LLM calls. For each method and for each of ten environments, the table shows the percentage of tasks successfully solved and the average Exploration Walk (EW) score. The EW score measures the similarity between the generated domain PDDL and the ground truth domain PDDL.

This table presents the results of four different methods for solving planning problems across ten different domains. The methods include two intrinsic planning baselines (with and without chain-of-thought prompting) and two proposed methods (P&D Chain and P&D Tree, with a variation: P&D Tree + DomProp). The table shows the ‘Best@4’ performance for each domain, representing the best result out of four independent runs. The results are shown as a fraction of tasks successfully solved and the average Exploration Walk (EW) score which measures the similarity of the generated domain to the ground truth domain. The EW score is undefined for the intrinsic planning methods as they don’t generate a domain.

This table presents the results of four different methods for solving planning tasks across ten different domains. The methods are: Intrinsic Planning without Chain-of-Thought (No CoT), Intrinsic Planning with Chain-of-Thought (CoT), P&D Chain, P&D Tree, and P&D Tree + DomProp. For each method and domain, two metrics are reported: the ‘Best@4’ task solve rate (the highest solve rate out of four independent runs) and the average Exploration Walk (EW) score. The EW score measures the similarity between the generated domain PDDL and the ground truth domain. A higher EW score indicates greater similarity, and therefore, better performance. Note that the EW score is not defined for intrinsic planning methods because these methods do not generate a domain PDDL.

Full paper#