↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Adam, a popular optimization algorithm in deep learning, suffers from theoretical non-convergence issues unless a hyperparameter (β2) is carefully chosen. Many attempts to fix this, like AMSGrad, rely on impractical assumptions about uniformly bounded gradient noise. This lack of theoretical guarantees and practical limitations hinder Adam’s wider applicability and robustness.

The paper introduces ADOPT (Adaptive gradient method with OPTimal convergence rate), a novel algorithm that overcomes these limitations. ADOPT achieves the optimal convergence rate of O(1/√T) for any choice of β2 without the bounded noise assumption. This is achieved by removing the current gradient from the second moment estimate and reordering the momentum update and normalization steps. Extensive experiments across various machine learning tasks demonstrate ADOPT’s superior performance and robustness compared to existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because adaptive gradient methods like Adam are widely used in deep learning, yet their theoretical convergence properties have been unclear. This research provides a much-needed theoretical foundation and a practical solution by introducing ADOPT, offering a significant advancement in the field. The findings open new avenues for improving the robustness and efficiency of adaptive optimization algorithms.

Visual Insights#

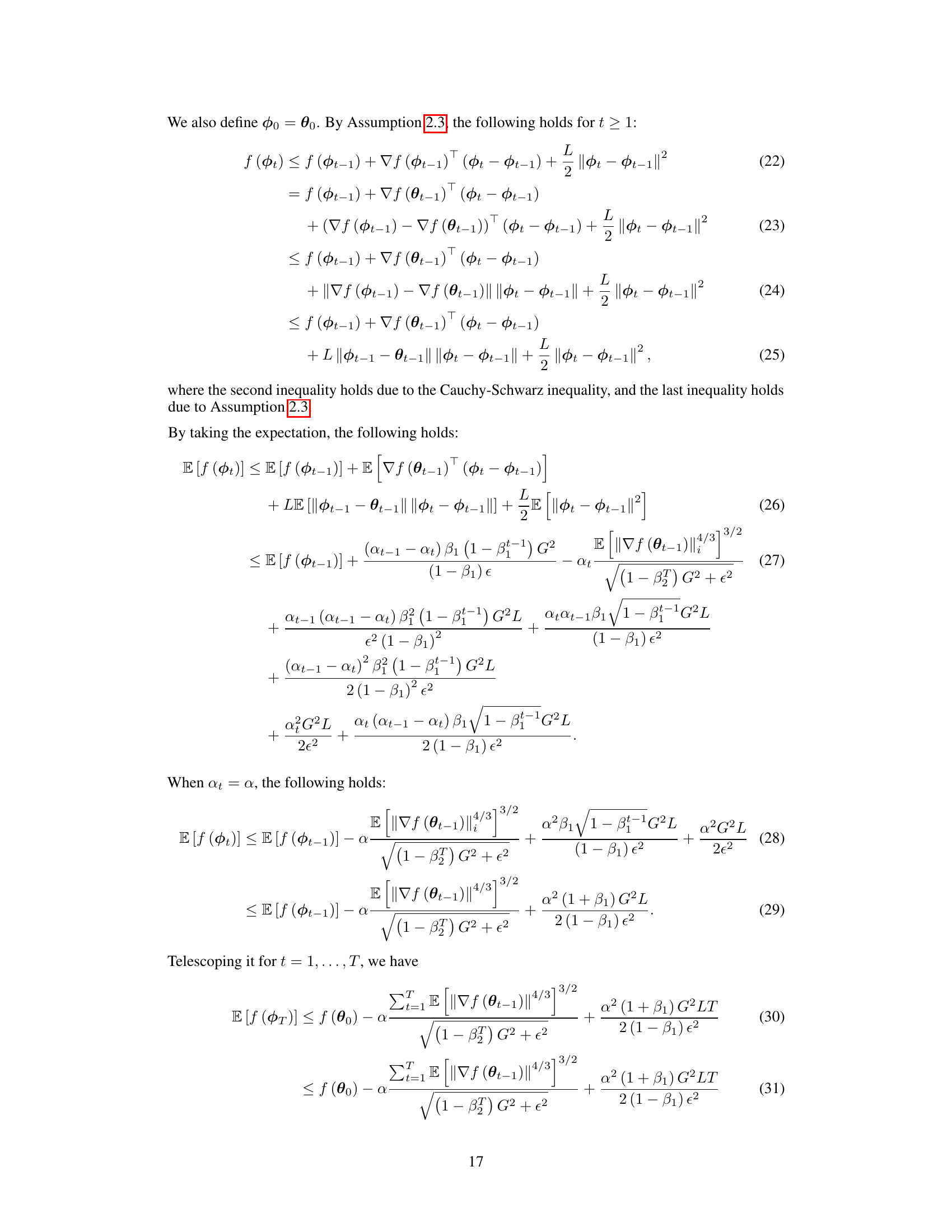

This figure compares the performance of three optimization algorithms (Adam, AMSGrad, and ADOPT) on a simple convex optimization problem where the goal is to find the parameter value that minimizes a function. The x-axis represents the optimization steps, and the y-axis represents the value of the parameter θ. The figure shows how each algorithm converges to the solution (θ = -1) over time for different values of hyperparameter β2 and illustrates how ADOPT is robust to different choices of β2 compared to Adam and AMSGrad.

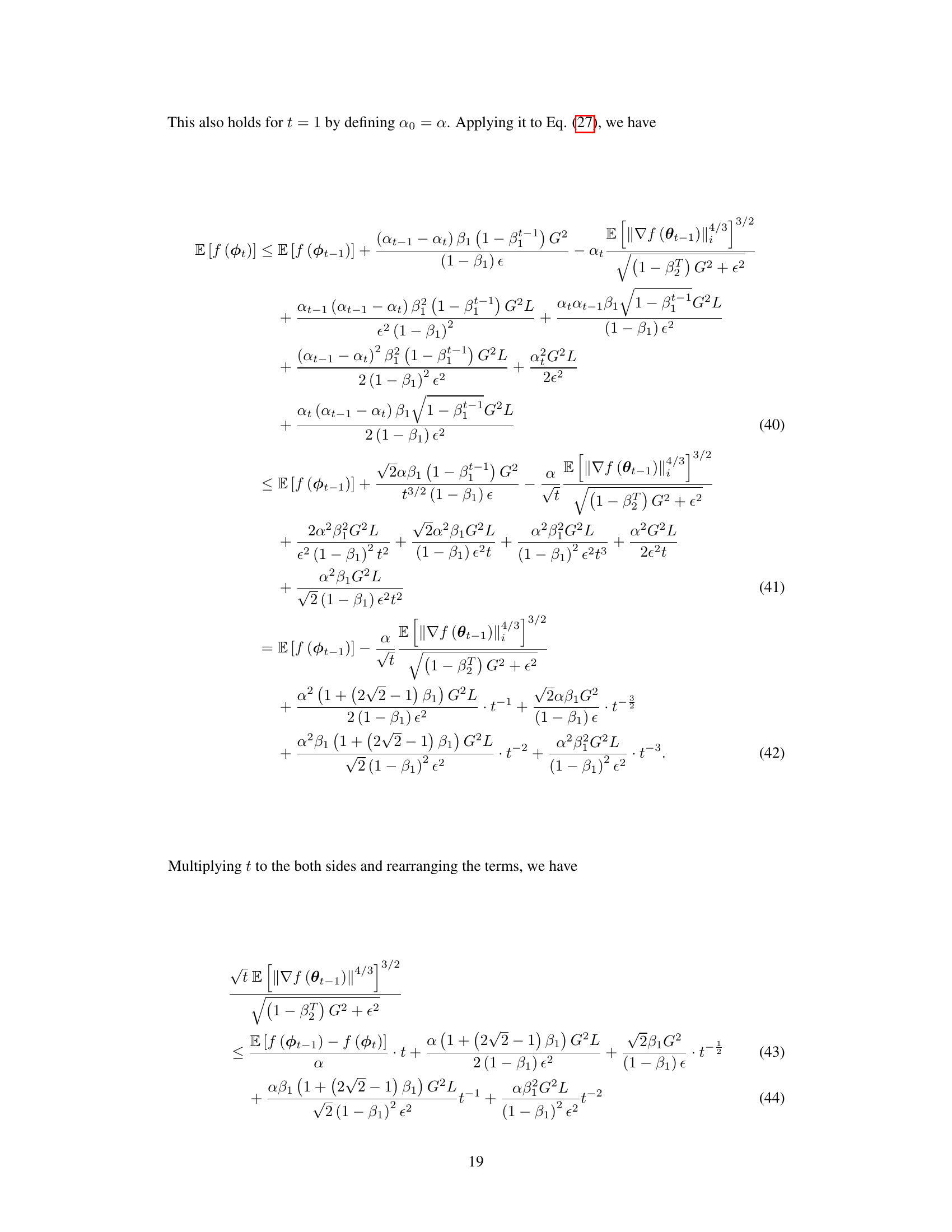

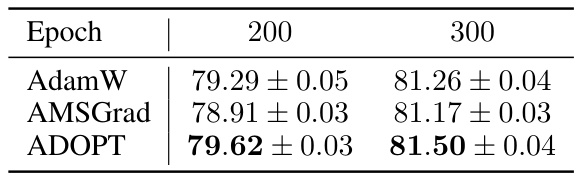

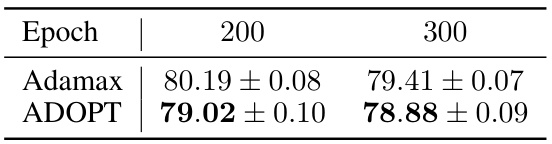

This table presents the top-1 accuracy results for ImageNet classification using the Swin Transformer model. The results are shown for two different epochs (200 and 300) and for three different optimizers: AdamW, AMSGrad, and ADOPT. The table highlights the superior performance of ADOPT compared to the other optimizers in achieving higher accuracy.

In-depth insights#

Adam’s Convergence#

The convergence behavior of the Adam optimizer in deep learning is a complex issue. While empirically successful, Adam lacks theoretical convergence guarantees for general non-convex problems, unlike stochastic gradient descent (SGD). Many attempts to address this shortcoming, such as AMSGrad, often rely on strong assumptions like uniformly bounded gradient noise which are often violated in practice. The core problem lies in the interaction between the second moment estimate and the current gradient. Novel approaches focus on removing the current gradient from the second moment calculation or modifying the update order, thereby mitigating the correlation and improving convergence. These modifications lead to adaptive methods with improved theoretical properties and superior empirical performance in various tasks across different neural architectures and datasets. The optimal convergence rate of O(1/√T) can be achieved under appropriate conditions, demonstrating significant progress in understanding and enhancing Adam’s practical capabilities. However, even with these improvements, some theoretical limitations remain, highlighting the ongoing research needed for complete convergence guarantees.

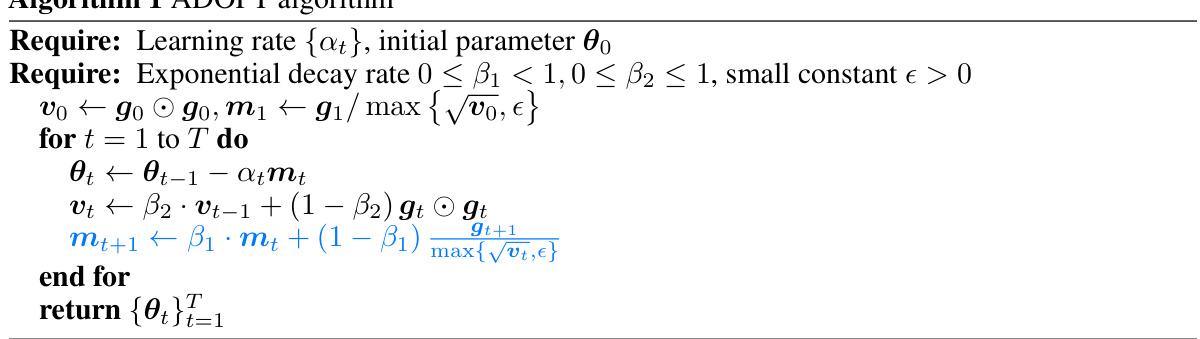

ADOPT Algorithm#

The ADOPT algorithm, a modified Adam optimizer, addresses Adam’s convergence issues by strategically altering the update order and removing the current gradient from the second moment estimate. This modification is theoretically significant, enabling ADOPT to achieve the optimal convergence rate of O(1/√T) for smooth non-convex optimization problems without the restrictive bounded noise assumption often required by Adam’s variants. Empirical evaluations demonstrate ADOPT’s superior performance across diverse machine learning tasks, including image classification, generative modeling, and natural language processing, showcasing its robustness and practical advantages over existing adaptive gradient methods like Adam and AMSGrad. The algorithm’s theoretical guarantees and empirical success suggest it is a powerful and reliable alternative for a broader range of optimization challenges in deep learning.

Empirical Analysis#

A robust empirical analysis section in a research paper would systematically evaluate the proposed method’s performance. It should start with a clear description of the experimental setup, including datasets, evaluation metrics, and baseline methods for comparison. A variety of experiments should be conducted to demonstrate the approach’s effectiveness across different scenarios. The results should be presented clearly, using tables and figures to visualize key findings. Statistical significance should be reported to ensure the observed results are not due to random chance. Furthermore, an in-depth discussion of the results is crucial, explaining any unexpected findings, comparing against baseline methods, and highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed method. The analysis should be thorough enough to support the claims made in the paper’s abstract and introduction. Finally, the analysis should be objective, avoiding overselling or underselling the results and acknowledging any limitations.

Theoretical Bounds#

Theoretical bounds in machine learning offer a crucial lens for understanding algorithm performance. They provide guarantees on the convergence rate, generalization error, or other key metrics, often expressed as a function of relevant parameters (e.g., sample size, dimensionality, learning rate). Tight bounds are highly desirable, as they offer stronger assurances, while loose bounds might still be valuable if they reveal important scaling relationships. Establishing theoretical bounds necessitates making assumptions—about the data distribution, model structure, or the optimization process—which must be carefully considered in assessing the applicability of the results. Assumptions too strong to hold in real-world scenarios limit the practical implications of such bounds. The process of deriving theoretical bounds often involves sophisticated mathematical tools and techniques from optimization, probability, and statistics, demanding careful analysis and rigorous proof. Ultimately, the value of theoretical bounds lies in their ability to provide insights into algorithm behavior, guide algorithm design, and inform the choice of hyperparameters leading to better practical performance.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could involve relaxing the bounded variance assumption on the stochastic gradient, a limitation of the current analysis. Investigating the convergence behavior under more general noise conditions is crucial for broader applicability. Another avenue is exploring the impact of different momentum schemes on the convergence rate and stability of ADOPT, potentially leading to enhanced performance. Furthermore, empirical evaluations on a wider range of complex tasks such as large language model training and advanced reinforcement learning problems are needed to validate the algorithm’s effectiveness and robustness. Finally, theoretical analysis focusing on the impact of hyperparameter choices could improve practical algorithm design and usage guidelines.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares the performance of three optimization algorithms (Adam, AMSGrad, and ADOPT) on a simple convex optimization problem where the goal is to find the parameter θ that minimizes a univariate function. The x-axis represents the number of optimization steps, and the y-axis represents the value of the parameter θ. Different lines correspond to different settings of the hyperparameter β₂ in each algorithm. The results illustrate that Adam’s convergence is highly dependent on the choice of β₂, often failing to converge to the correct solution (θ = -1). AMSGrad shows improvement in convergence but is still significantly slower than ADOPT, which consistently converges to the correct solution across all β₂ settings, showcasing its robustness and superior performance.

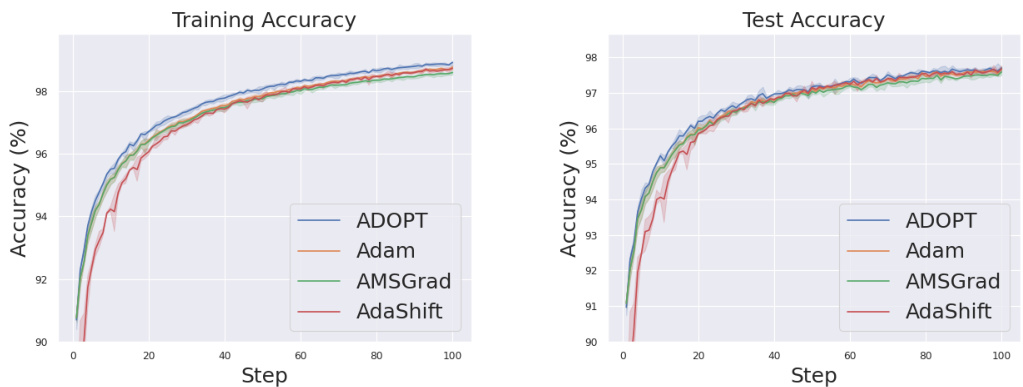

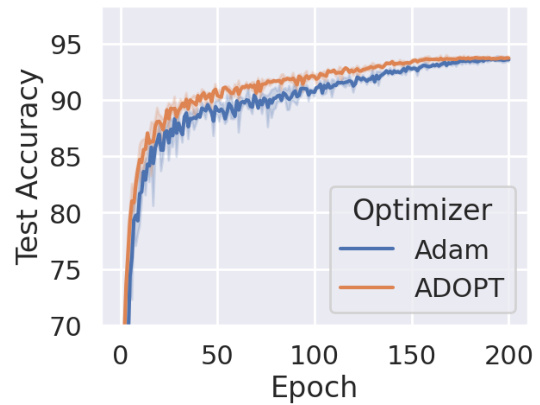

The figure shows the training and test accuracy curves for four different optimization algorithms (ADOPT, Adam, AMSGrad, and AdaShift) on the MNIST handwritten digit classification task. The left panel displays training accuracy, while the right panel shows test accuracy. The x-axis represents the training step, and the y-axis shows the accuracy percentage. Error bars, representing the 95% confidence intervals across three independent trials, are included to illustrate the variability of the results. The figure visually demonstrates the comparative performance of the different algorithms.

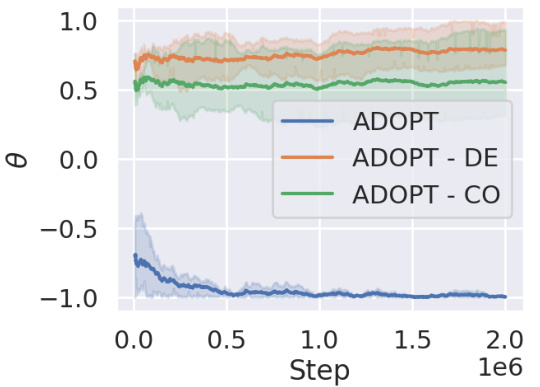

This figure shows the result of ablation study on how the two algorithmic changes from Adam to ADOPT affect the convergence. The two changes are (1) decorrelation between the second moment estimate and the current gradient, and (2) change of order of momentum update and normalization by the second moment estimate. Each change is removed from ADOPT separately, and its performance is compared with the original ADOPT in a simple univariate convex optimization problem. The result shows that both changes are essential for ADOPT to converge properly.

This figure compares the training and test accuracy of four different optimizers (ADOPT, Adam, AMSGrad, and AdaShift) on the MNIST handwritten digit classification task. The x-axis represents the training step, and the y-axis represents the accuracy. Error bars show the 95% confidence intervals, indicating the variability across three separate trials. The results show that ADOPT achieves the highest accuracy, highlighting its effectiveness in this non-convex optimization problem.

This figure shows the learning curves for training and validation losses during the GPT-2 pretraining process. Two different batch sizes (480 and 96) are used, and the performance of both Adam and ADOPT optimizers are compared. The results highlight ADOPT’s stability and improved convergence, especially with the smaller batch size (96). Adam exhibits loss spikes and instability with the smaller batch size but performs comparably to ADOPT with the larger batch size.

This figure displays the performance comparison between Adam and ADOPT optimizers in two deep reinforcement learning tasks: HalfCheetah-v4 and Ant-v4. The x-axis represents the number of steps in the training process, and the y-axis shows the cumulative reward (return) achieved by the agents. Each line represents the average performance across multiple trials, with shaded areas indicating the standard deviation. The figure visually demonstrates whether ADOPT shows any improvement over Adam in reinforcement learning.

This figure compares the performance of AdamW and ADOPT optimizers when fine-tuning a large language model (LLaMA-7B) using instruction-following data. The MMLU (Multi-task Language Understanding) benchmark is used to evaluate the performance across various tasks. The bar chart shows the scores for each task, allowing for a direct comparison of AdamW and ADOPT’s effectiveness in this specific fine-tuning scenario.

More on tables

This table presents the results of negative log-likelihood for training NVAE models on the MNIST dataset using two different optimizers: Adamax and ADOPT. The negative log-likelihood is a metric used to evaluate the performance of generative models, with lower values indicating better performance. The table shows the results at epochs 200 and 300, allowing for a comparison of performance over time.

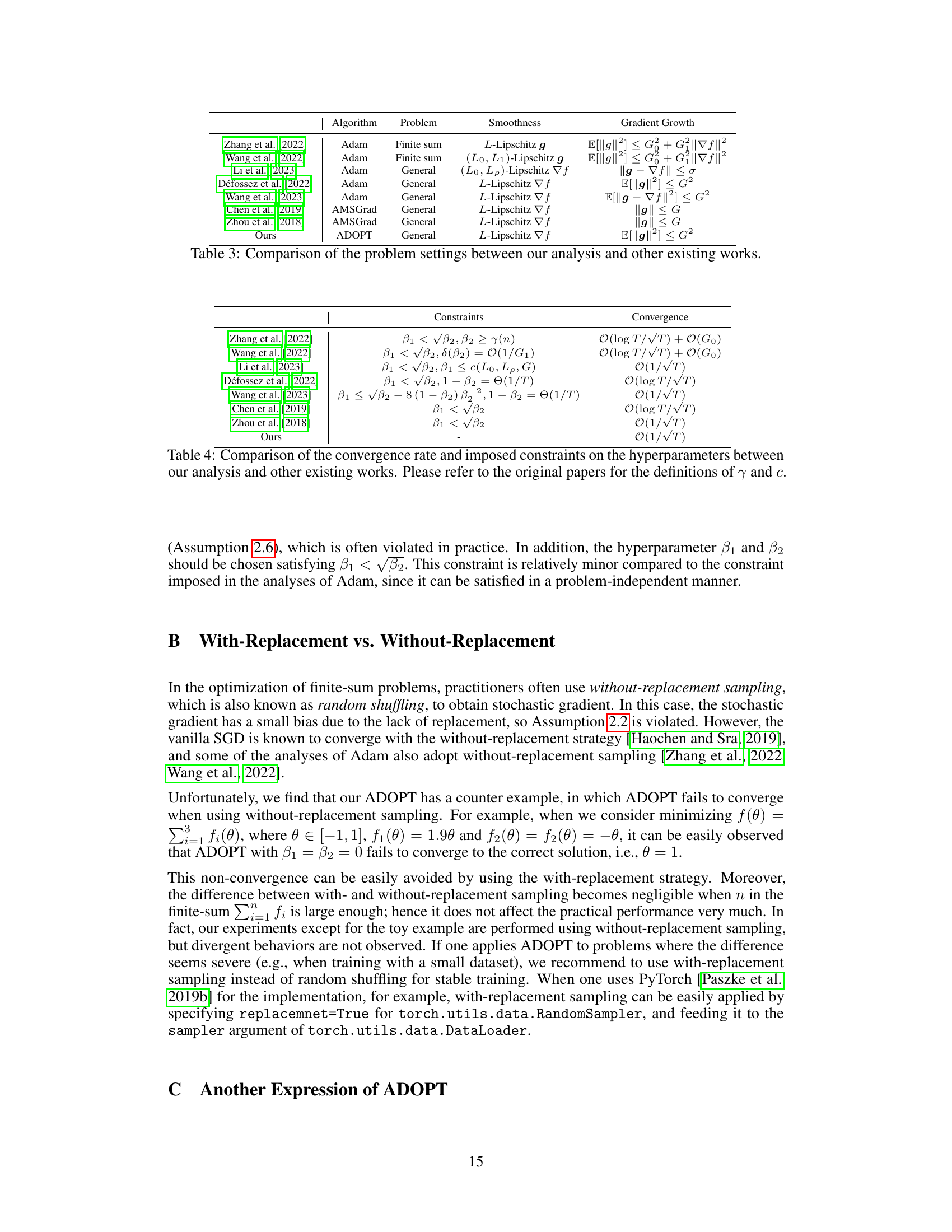

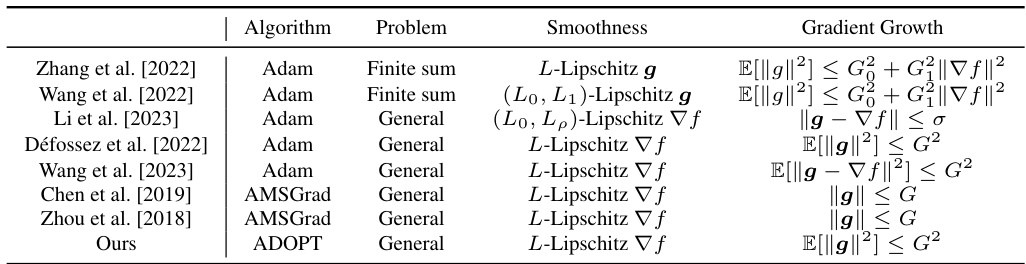

This table compares various optimization algorithms (Adam, AMSGrad, and ADOPT) across different papers, focusing on the problem type (finite sum or general), smoothness assumptions (Lipschitz conditions on the gradient or true gradient), and gradient growth conditions (bounds on the gradient norm or variance). The table highlights the differences in the assumptions used in each analysis, which can significantly influence the convergence results.

This table compares the convergence rates and hyperparameter constraints derived by different studies on Adam and related adaptive gradient methods. It contrasts the assumptions made (and their implications) for each analysis, highlighting the differences in convergence guarantees obtained under varying conditions and constraints on hyperparameters beta1 and beta2. The ‘Ours’ row represents the findings and constraints (or lack thereof) presented in this particular research paper.

This table presents the recommended hyperparameter settings for the ADOPT algorithm. It suggests using β₁ = 0.9, β₂ = 0.9999, and ε = 1 × 10⁻⁶. These values were experimentally determined to provide similar performance to Adam, but with a slightly larger ε value (1 × 10⁻⁶ vs. 1 × 10⁻⁸ for Adam) for better results.

Full paper#