↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Linear stochastic approximation (LSA) is a cornerstone of many machine learning algorithms, yet constructing reliable confidence intervals for its estimates has been challenging. Existing methods primarily rely on asymptotic normality, which doesn’t offer finite-sample guarantees. This limits their practical use, especially in online learning scenarios where only a limited number of samples are available. Furthermore, the rate of convergence to normality wasn’t well understood for LSA.

This research tackles these issues head-on. The authors introduce a novel multiplier bootstrap method for constructing confidence intervals for Polyak-Ruppert averaged LSA iterates. They prove the non-asymptotic validity of this approach, demonstrating approximation accuracy of order n⁻¹/⁴ (where n is the number of samples). Their analysis provides a Berry-Esseen bound, quantifying the rate of convergence to normality, and addresses the crucial issue of finite-sample confidence intervals. The method is applied to the well-known temporal-difference learning algorithm, showing considerable improvement in the accuracy of statistical inference.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in stochastic approximation and reinforcement learning. It provides non-asymptotic guarantees for the accuracy of confidence intervals, a significant improvement over existing asymptotic results. This opens avenues for more reliable statistical inference in online learning algorithms and enables better analysis of temporal difference learning.

Visual Insights#

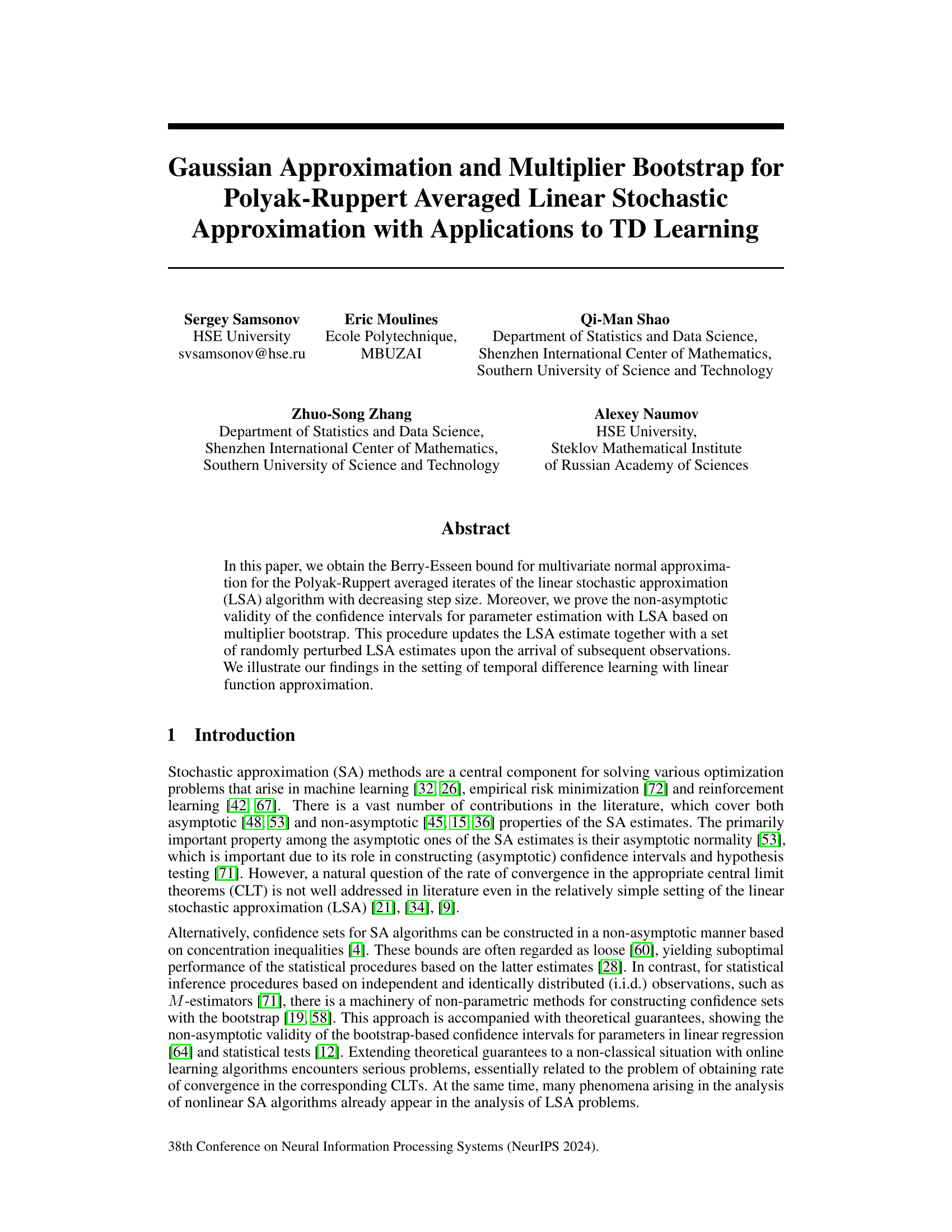

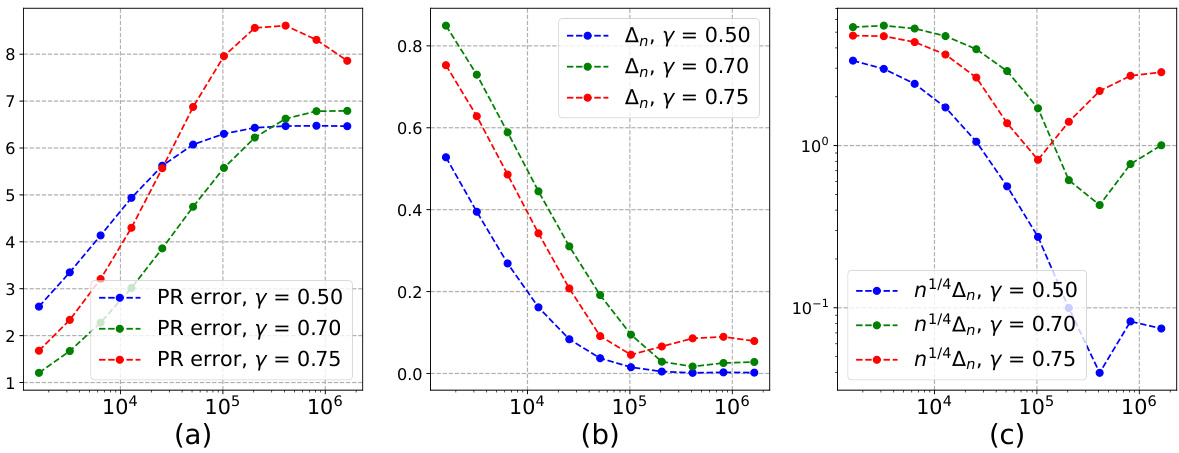

This figure presents the results of numerical experiments for the TD learning algorithm. Subfigure (a) shows the rescaled error of the Polyak-Ruppert averaged TD learning iterates for different trajectory lengths n and learning rates γ. Subfigure (b) shows the approximate quantity Δn, which measures the accuracy of the normal approximation of the TD learning iterates, for different powers γ and n. Subfigure (c) shows the same quantity Δn rescaled by a factor of n1/4. The results show that the accuracy of the normal approximation is of order n−1/4 for γ = 1/2, and slower for other learning rates. This is consistent with the theoretical findings of Theorem 2 in the paper.

In-depth insights#

LSA Normal Approx#

The heading ‘LSA Normal Approx’ likely refers to a section detailing the asymptotic normality of the linear stochastic approximation (LSA) algorithm. This is a crucial aspect of LSA analysis because it justifies using normal approximations for statistical inference, like constructing confidence intervals or hypothesis tests. The core of this section would involve proving a central limit theorem (CLT) for the LSA estimator. A key focus would be the rate of convergence to normality, quantifying how quickly the estimator’s distribution approaches the normal distribution as the number of samples increases. The paper likely establishes a Berry-Esseen bound, providing a non-asymptotic error bound for the normal approximation. This would offer a precise quantitative measure of the approximation’s accuracy, offering a more refined analysis compared to solely relying on asymptotic results. Furthermore, it might discuss the impact of algorithm parameters (like step sizes) on the rate of convergence, helping guide practical implementations. The mathematical techniques used would likely involve advanced probability and stochastic approximation theory, potentially employing concentration inequalities and martingale techniques for rigorous analysis.

Multiplier Bootstrap#

The heading ‘Multiplier Bootstrap’ suggests a resampling technique used to estimate confidence intervals for parameters derived from the Polyak-Ruppert averaged linear stochastic approximation (LSA) algorithm. This is particularly useful in online learning settings where traditional bootstrap methods are computationally infeasible. The multiplier bootstrap approach, by recursively updating LSA estimates alongside randomly perturbed estimates, offers a way to approximate the distribution of the LSA estimator. Its online nature avoids the limitations of storing previous iterates, making it suitable for large datasets and online applications. The paper likely provides theoretical guarantees for the accuracy of this approximation, establishing non-asymptotic bounds on its performance. This involves assessing how well the multiplier bootstrap’s quantiles approximate the true quantiles of the LSA estimator’s distribution. The theoretical analysis is expected to offer insights into the choice of parameters (e.g., step sizes, number of bootstrap samples) that control the accuracy of the bootstrap approximation. Ultimately, this section likely demonstrates the effectiveness of the method with applications to problems like reinforcement learning’s Temporal Difference (TD) learning algorithm.

TD Learning App#

The heading ‘TD Learning App’ suggests an application of Temporal Difference (TD) learning, a reinforcement learning algorithm. The paper likely details how TD learning is implemented in a specific application, potentially showing improvements or novel approaches to TD learning. This could involve adaptations for specific problem domains, optimization techniques for faster convergence, or the integration of TD learning with other machine learning methods. A key aspect might be the evaluation of the application’s performance using metrics appropriate for the chosen domain, demonstrating the algorithm’s effectiveness and efficiency. The application’s practical use case would be highlighted, illustrating the real-world implications of the research and potentially addressing challenges inherent in applying TD learning to the chosen problem. Comparative analysis with other methods might be included, showcasing the advantages of the proposed TD learning application. The focus likely lies on non-asymptotic analysis and bootstrap methodology, common themes in this paper’s broader focus.

Non-Asymptotic B-E#

The heading ‘Non-Asymptotic B-E’ likely refers to a section detailing non-asymptotic Berry-Esseen bounds. This is a significant contribution because Berry-Esseen theorems typically provide asymptotic results, describing the rate at which a normalized sum of random variables converges to a normal distribution as the number of terms approaches infinity. A non-asymptotic version would offer finite-sample guarantees, providing bounds on the approximation error for any given sample size. This is crucial for applications in machine learning and statistics where the number of data points is finite. The focus on the Polyak-Ruppert averaged linear stochastic approximation algorithm suggests the bounds likely pertain to the estimation error of this algorithm, quantifying the accuracy of the normal approximation of its output. The significance lies in enabling reliable confidence intervals and hypothesis testing in practical scenarios where only a limited number of observations are available. A key insight would be the dependence of the bound on the sample size, the algorithm’s parameters, and the properties of the random variables involved, offering a more precise understanding of the algorithm’s performance.

Future Research#

The paper’s conclusion highlights several promising avenues for future research. Extending the Berry-Esseen bounds and multiplier bootstrap validity to settings with Markovian noise or dependent observations is a crucial next step, moving beyond the i.i.d. assumption. This extension is nontrivial but would significantly enhance the practical applicability of the results. Further investigation into the optimal learning rate schedule, particularly regarding its relationship to convergence rates in different metrics (e.g., Wasserstein), warrants exploration. The paper suggests exploring the non-asymptotic validity of confidence intervals based on covariance matrix estimation, comparing it with the proposed bootstrap approach. Generalizing the findings to non-linear stochastic approximation and first-order gradient methods holds the potential for broader impact across various machine learning contexts, although this faces non-trivial challenges. Finally, a thorough examination of the impact of dimensionality and other instance-dependent quantities on the obtained bounds is recommended to further refine the theoretical guarantees.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the results of the temporal difference (TD) learning experiments. Subfigure (a) displays the rescaled error, showing how the error decreases as the number of trajectories (n) increases. The rescaling is done to make it easier to see differences between learning rates (y). Subfigure (b) shows the same error, but without rescaling, making it apparent how the error magnitude changes.

Figure 3 shows two plots that present the rescaled error ∆n n¹/⁴, which represents the accuracy of the normal approximation for the distribution of the Polyak-Ruppert averaged LSA iterates in the context of temporal difference (TD) learning. Subfigure (a) shows the rescaled error on a linear y-axis scale while Subfigure (b) uses a logarithmic y-axis for a clearer visualization of smaller error values. Different lines in the plots represent different step size decay rates (γ values) in the TD learning algorithm, illustrating how the choice of step size impacts the accuracy of the normal approximation. The figure aims to demonstrate the tightness of the theoretical bounds provided in Theorem 2, suggesting that the best approximation rate is achieved when γ = 1/2.

Full paper#