↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current research on large language models (LLMs) primarily focuses on understanding information storage and transfer in text-based models. However, multi-modal LLMs (MLLMs), which process both text and images, are rapidly increasing in popularity. This paper bridges this gap by investigating how MLLMs handle factual information in a visual question answering task, identifying specific mechanisms and limitations.

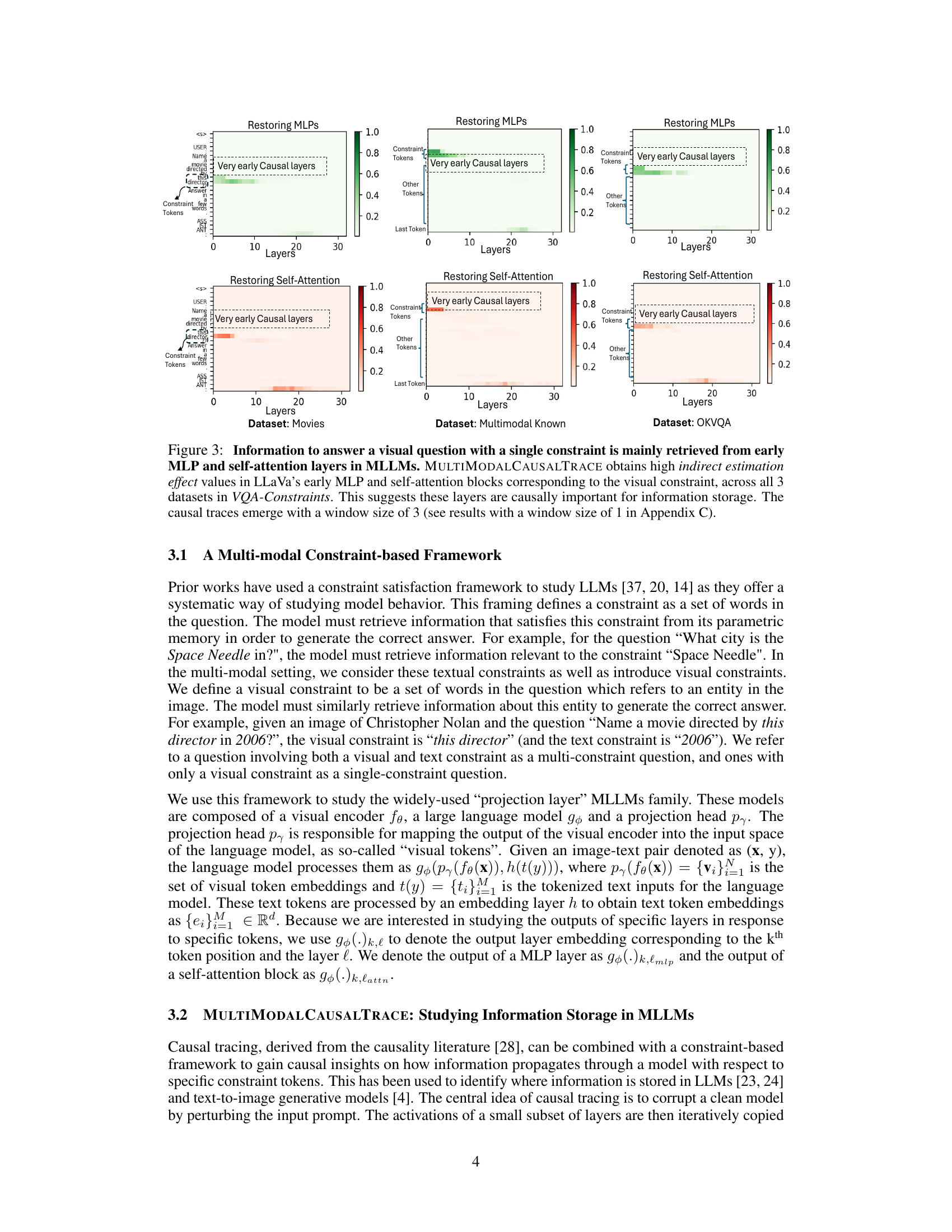

The researchers developed a constraint-based method called MULTIMODALCAUSALTRACE to trace information flow within MLLMs and also created a new dataset, VQA-Constraints, with questions annotated with constraints. They used these tools to study two MLLMs (LLaVa and multi-modal Phi-2) and discovered that, unlike LLMs, MLLMs rely on earlier layers for information storage and transfer. The team also developed MULTEDIT, an algorithm for correcting errors and adding information in MLLMs by directly modifying early causal layers.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with multi-modal large language models (MLLMs) as it offers novel insights into information storage and transfer mechanisms, introduces a new model-editing algorithm, and provides a valuable dataset for future research. It directly addresses the need for better understanding and control of these powerful models, opening up new avenues for improvement and responsible development.

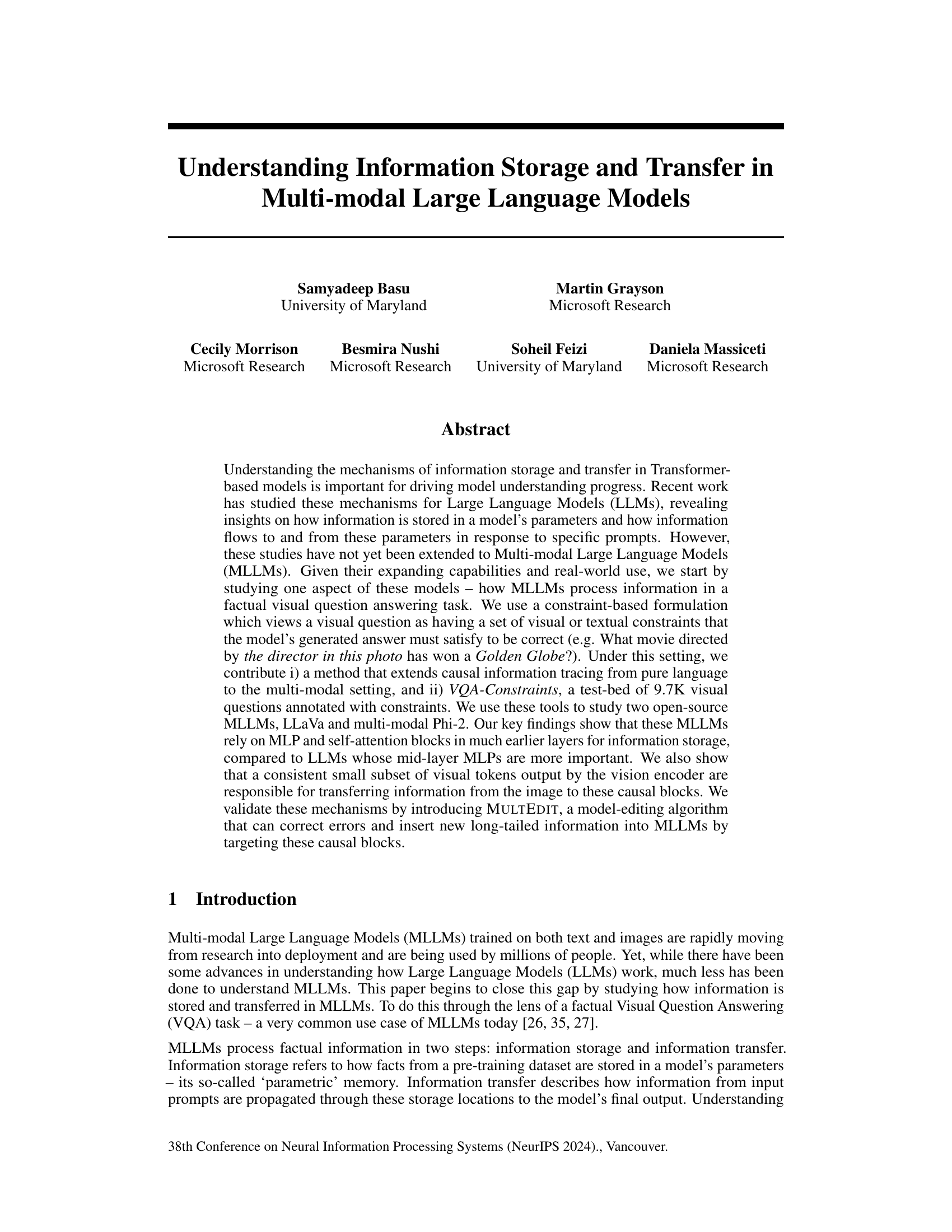

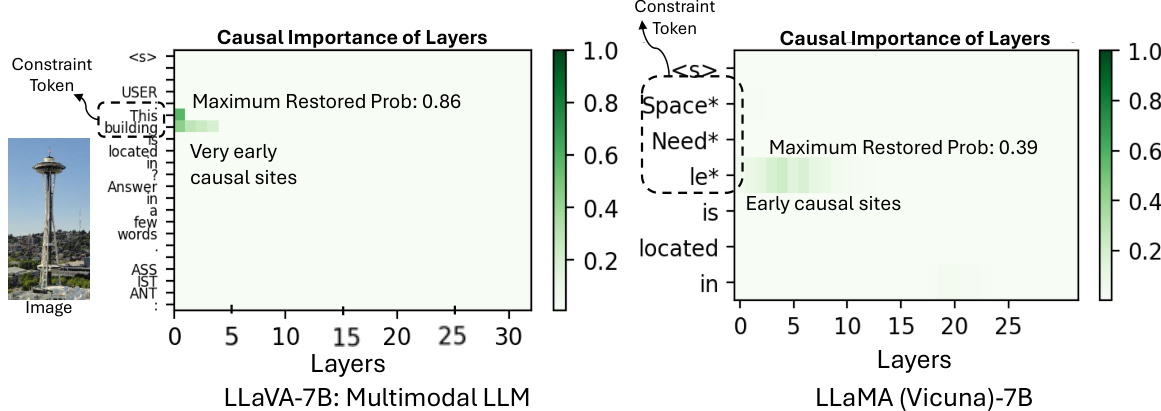

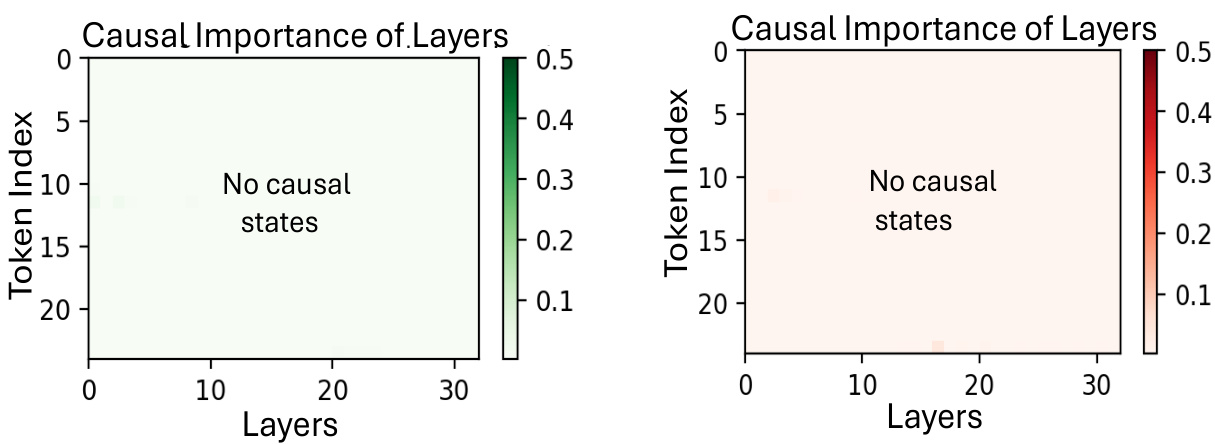

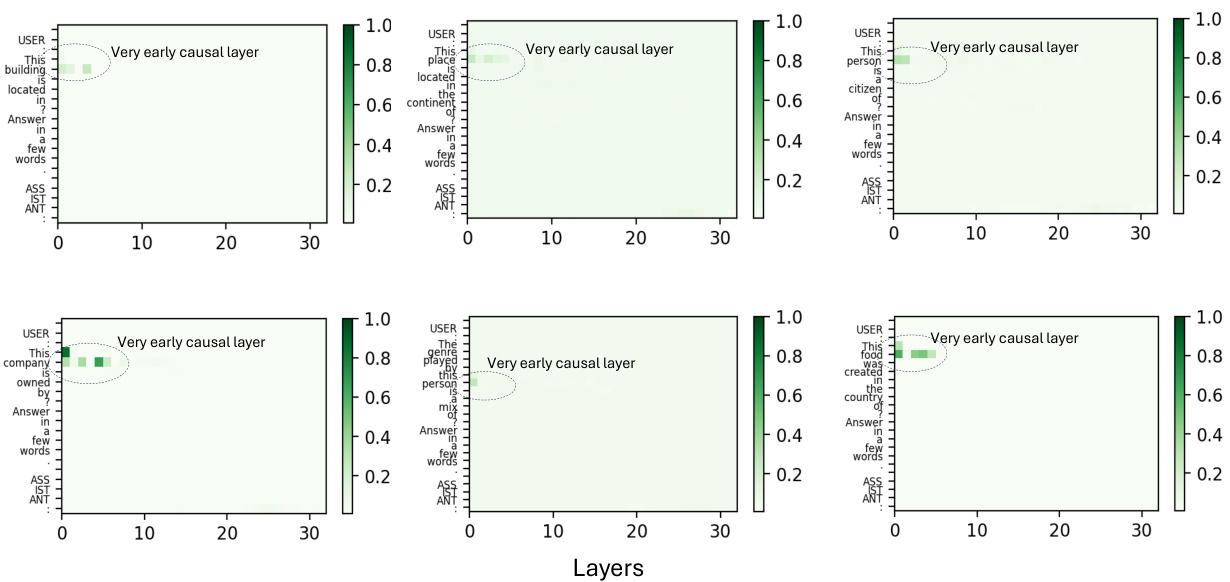

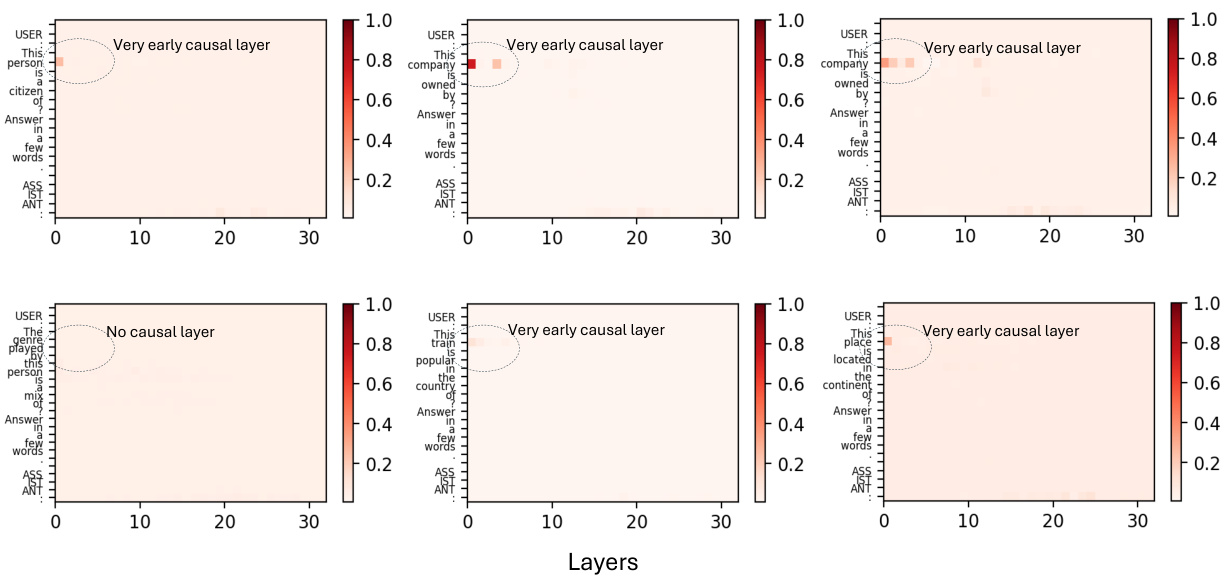

Visual Insights#

This figure compares the causal importance of different layers in two multi-modal large language models (MLLMs), LLaVA-7B and LLaMA (Vicuna)-7B, when performing a visual question answering task. The x-axis represents the layers of the model, and the y-axis represents the causal importance, indicating how much each layer contributes to the final output. The figure shows that MLLMs tend to retrieve information from much earlier layers (layers 1-4 for LLaVA-7B) compared to single-modal LLMs which use middle layers (layers 4-7 for LLaMA). The different window sizes needed to identify causal layers also highlight a difference in how these models utilize parametric memory. The plot visualizes this using heatmaps, showing the most influential layers for the given constraints within the question and corresponding image.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal Info Tracing#

Multimodal information tracing is a crucial area of research that seeks to understand how information flows within complex multi-modal models. It builds upon prior work in causal tracing for large language models (LLMs), extending the methods to handle inputs from multiple modalities, such as text and images. The fundamental challenge lies in disentangling the contributions of each modality and elucidating how information is stored and integrated across different layers of the model. By carefully tracing information flow, it becomes possible to identify crucial layers responsible for multimodal information storage and reveal how visual and textual cues interact. This approach offers a nuanced understanding of the model’s internal mechanisms, offering insights that could improve model interpretability, trustworthiness, and even lead to methods for correcting errors or introducing new information. Crucially, the development of new methodologies and datasets is required to effectively study the complexities of multimodal information processing, particularly concerning the interplay of vision and language. The insights generated from multimodal tracing could significantly advance the field, bridging the gap between model design and the fundamental principles of information processing.

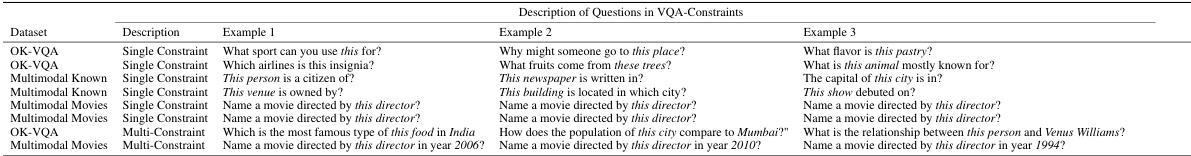

Constraint-Based VQA#

Constraint-Based Visual Question Answering (VQA) offers a novel approach to evaluating and understanding the capabilities of multi-modal large language models (MLLMs). Instead of relying solely on the accuracy of the final answer, this framework focuses on the model’s ability to satisfy a set of constraints derived from the question and the provided image. This constraint-based approach allows for a deeper analysis of how MLLMs process information, specifically highlighting how they retrieve and integrate visual and textual cues to produce factually correct answers. By dissecting the model’s reasoning process through the lens of constraints, we gain valuable insights into its internal mechanisms and can better identify areas for improvement. The ability to verify whether a model’s answer satisfies the specified constraints provides a more nuanced evaluation metric than simple accuracy, leading to a richer understanding of MLLM capabilities and limitations. This method opens avenues for advanced model analysis and facilitates the development of more robust and reliable MLLMs.

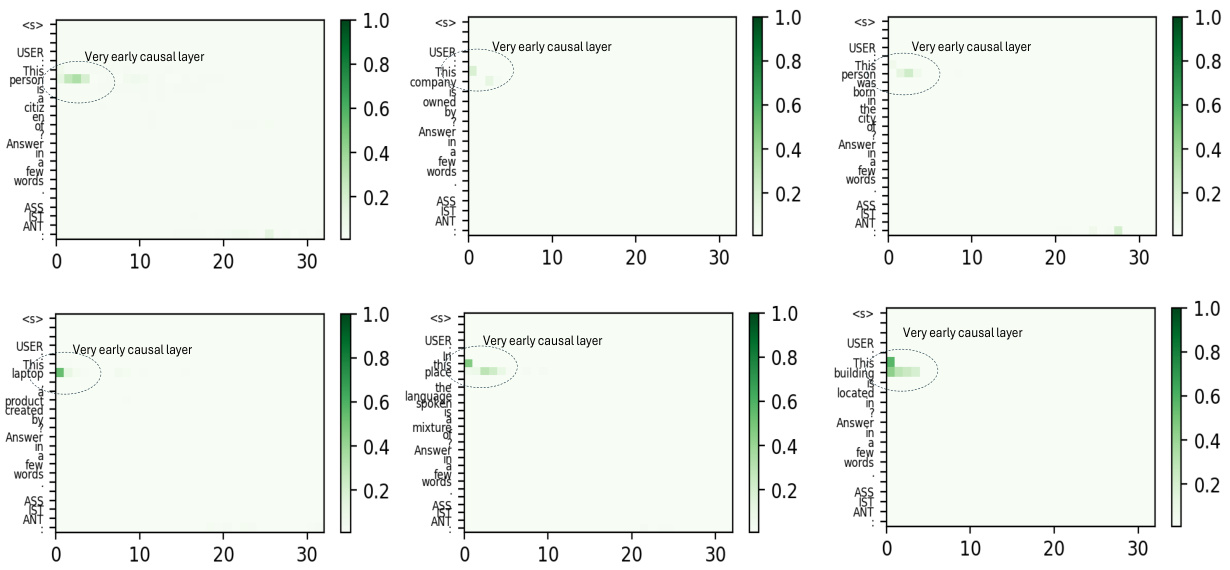

Early Layer Causality#

The research paper’s findings on “Early Layer Causality” challenge conventional wisdom in multi-modal large language models (MLLMs). Contrary to expectations that factual information is primarily stored in deeper layers, as seen in LLMs, the study reveals that MLLMs leverage early layers (1-4) significantly more for information storage and retrieval during visual question answering. This suggests a fundamental difference in how MLLMs process and store information compared to their text-only counterparts. The utilization of early MLP and self-attention blocks in these earlier layers highlights the models’ efficiency in processing multi-modal input and suggests a more direct and integrated approach to information access. The reliance on early layers, especially when processing visual constraints, points towards a more immediate and localized integration of visual information within the network, unlike the potentially more distributed storage patterns in LLMs. This discovery prompts exciting new research directions to better understand the unique architecture of MLLMs and refine model interpretability techniques.

Visual Token Transfer#

The concept of ‘Visual Token Transfer’ in multi-modal large language models (MLLMs) is crucial for understanding how visual information is integrated into the model’s textual processing. It involves investigating the mechanisms by which visual tokens, generated by an image encoder (like CLIP), are effectively incorporated into the language encoder’s processing. This transfer is not simply a concatenation; it likely involves sophisticated attention mechanisms and transformations that selectively integrate relevant visual features into the language representation. Efficient transfer is key to the success of MLLMs in visually-grounded tasks like VQA, where the model needs to connect image content with textual questions and answers. Analyzing this transfer process requires examining the flow of information between the visual and textual components, potentially identifying bottlenecks or critical pathways influencing the model’s comprehension and response generation. Further research in this area could involve visualizing attention weights, studying the impact of different visual token embedding strategies, and developing methods to improve the efficiency and accuracy of this information transfer for enhanced performance and interpretability.

MULTEDIT Algorithm#

The MULTEDIT algorithm, as described in the research paper, presents a novel approach for correcting errors and inserting new information into multi-modal large language models (MLLMs). Its core innovation lies in targeting specific causal blocks within the MLLM’s architecture, identified through causal tracing techniques. By editing the weight matrices of these early causal MLP layers, MULTEDIT introduces a closed-form update, efficiently modifying the model’s behavior without extensive retraining. This targeted approach offers significant advantages over full model fine-tuning, providing a more efficient and precise method for knowledge manipulation. The algorithm’s effectiveness is demonstrated in experiments involving both error correction and the insertion of long-tailed factual knowledge, showcasing its potential for enhancing MLLM capabilities and addressing limitations related to factual accuracy and knowledge coverage. Further research could explore the algorithm’s scalability and robustness across a wider variety of MLLMs and tasks, investigating potential limitations and exploring methods to prevent unintended consequences.

More visual insights#

More on figures

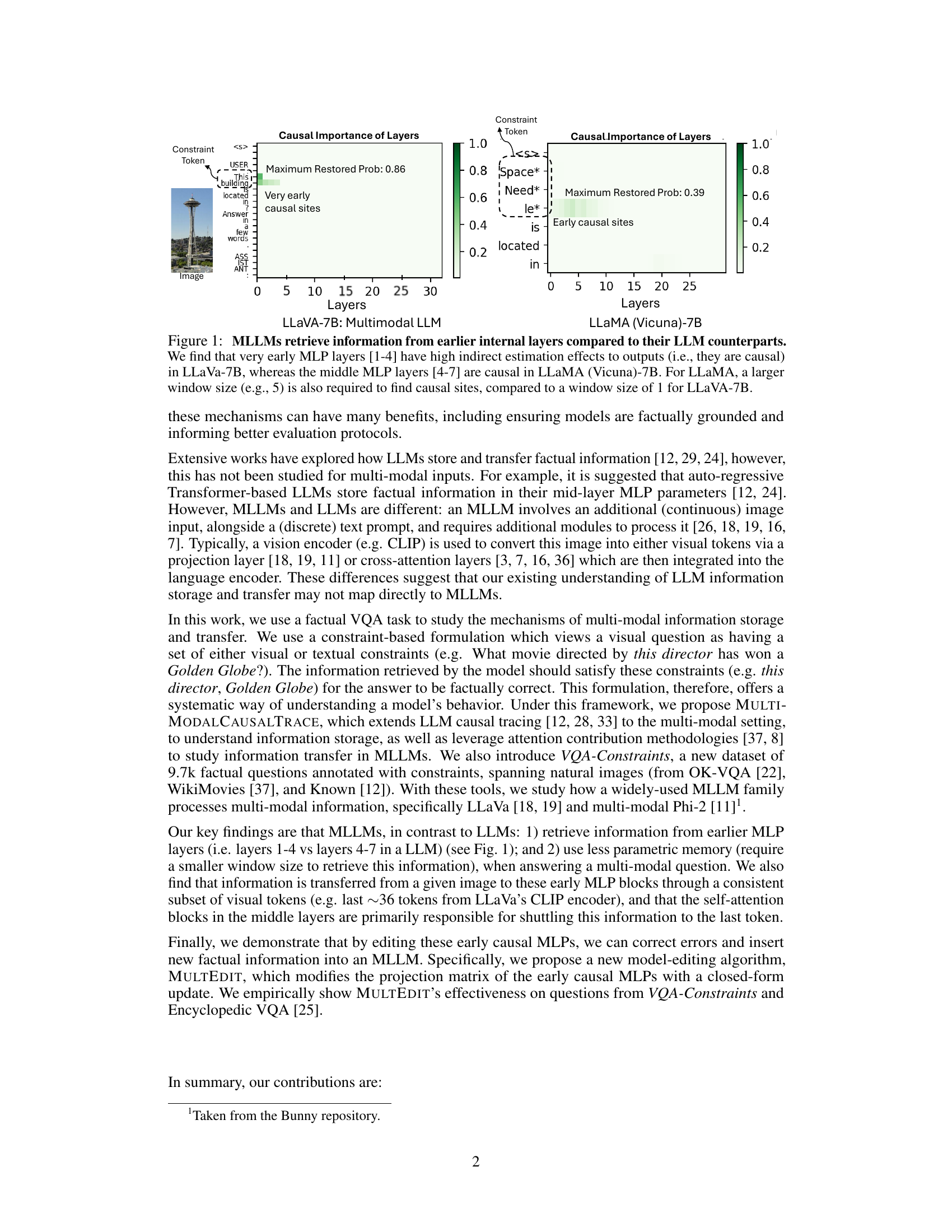

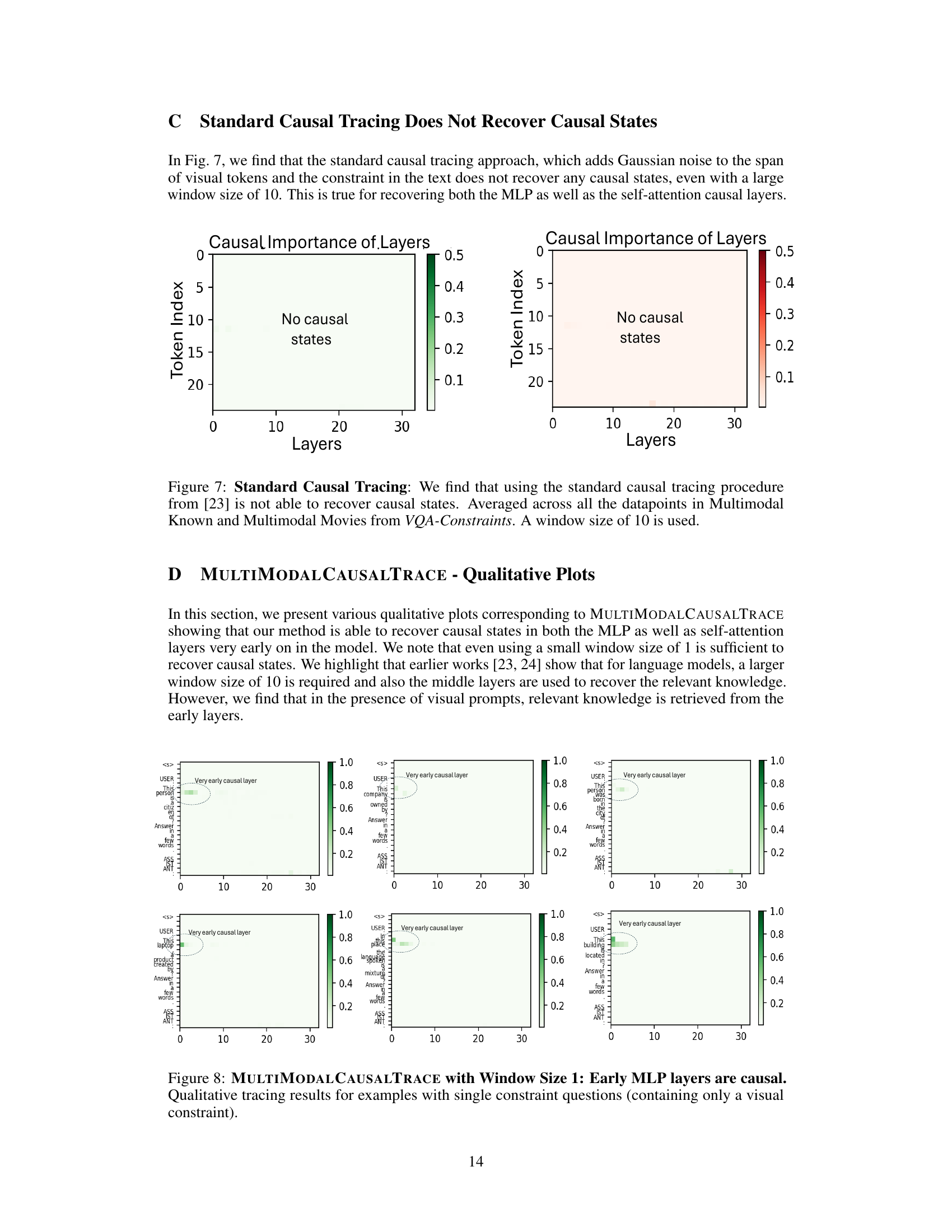

This figure illustrates the MULTIMODALCAUSALTRACE method. A clean model’s response to a question with a visual constraint is compared to a corrupted model where the constraint has been changed (e.g., ‘This place’ changed to ‘Paris City’). Iterative copying of layer activations from the clean model to the corrupted model helps identify the layers causally responsible for the correct answer. The plot shows the causal importance of layers for the clean model.

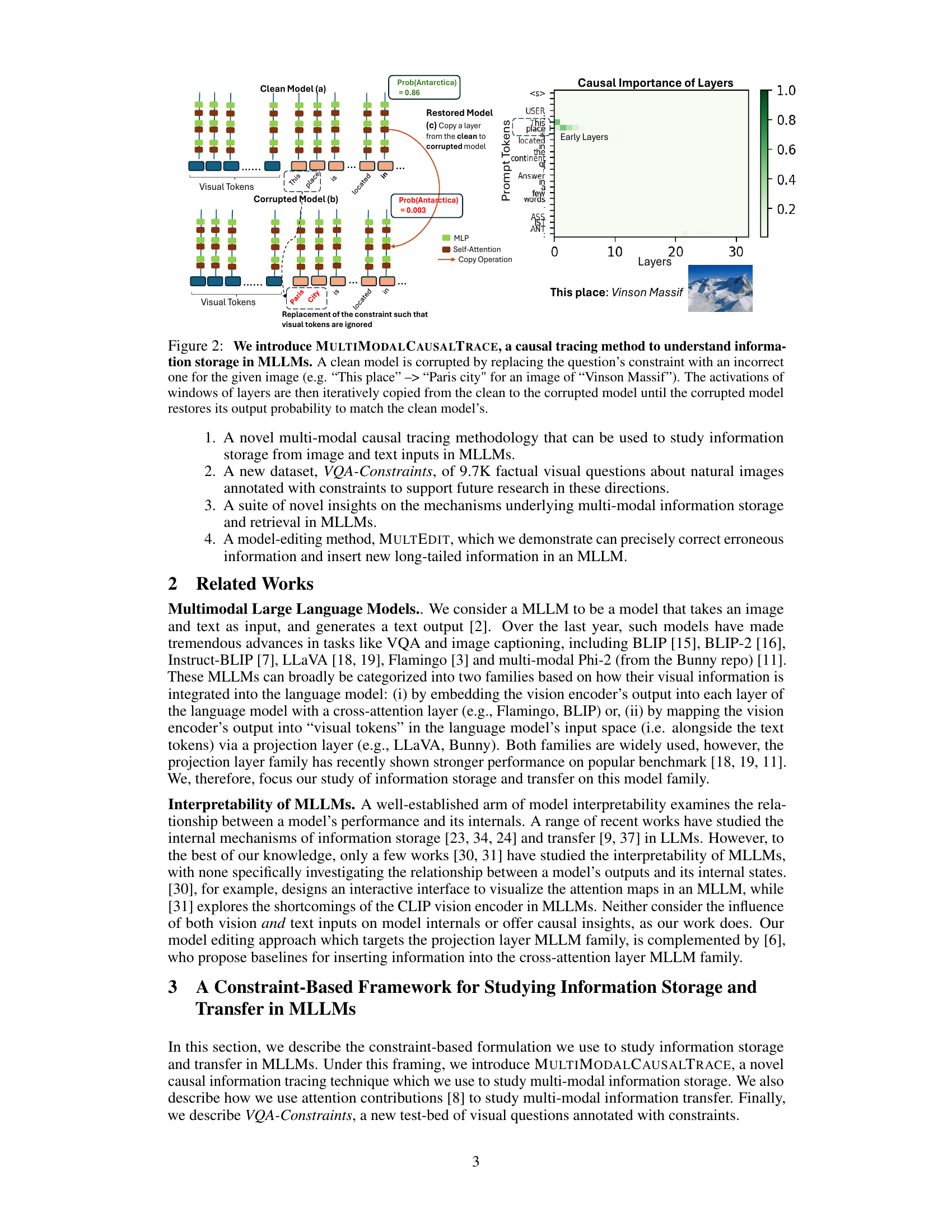

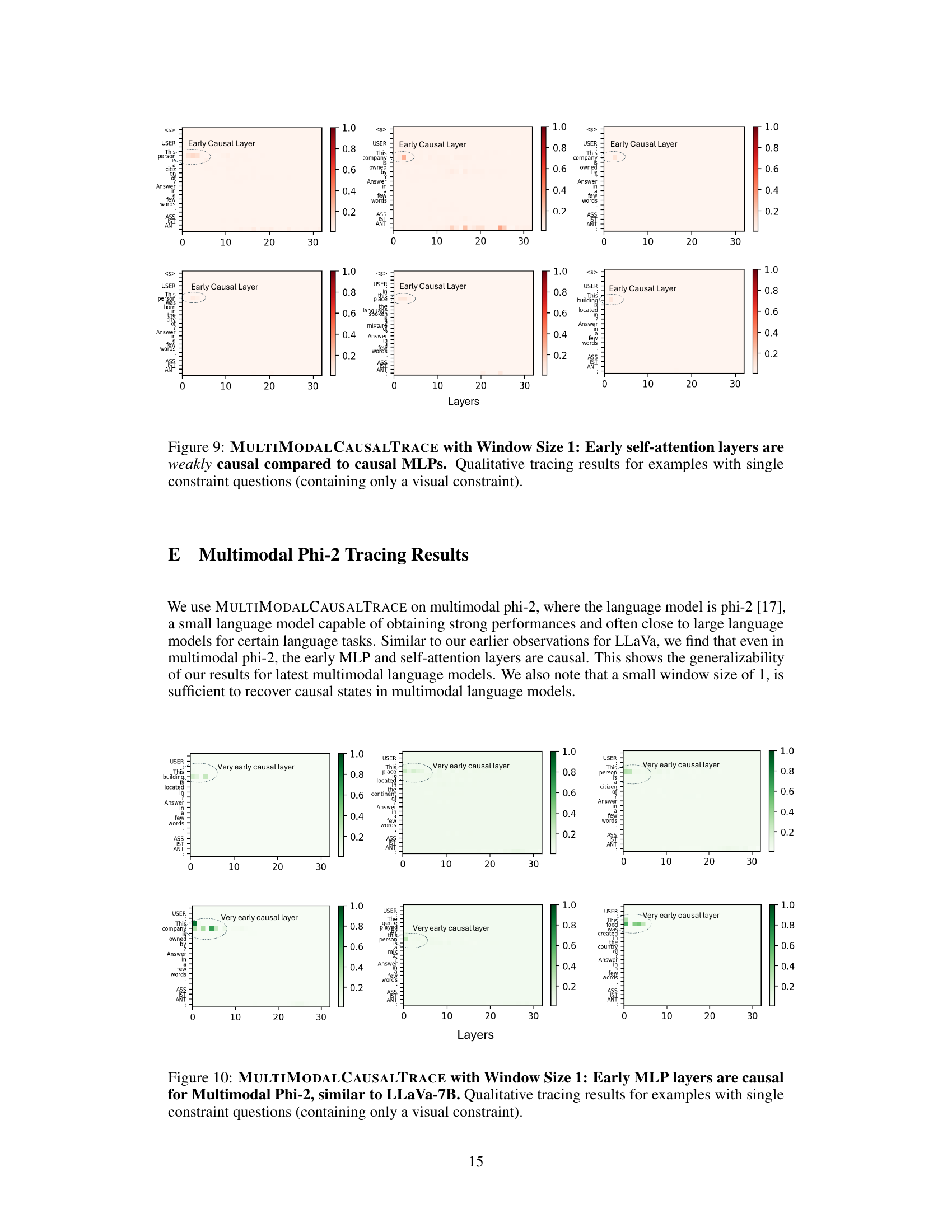

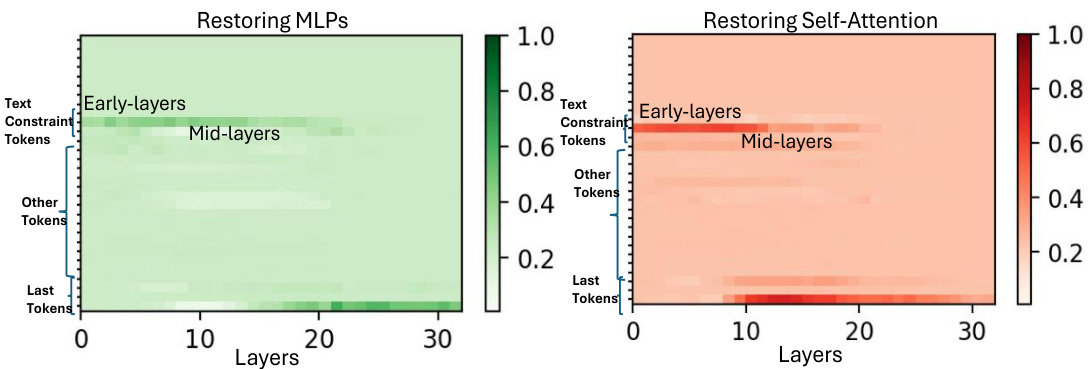

The figure shows the causal importance of different layers (MLP and self-attention) in two multi-modal large language models (MLLMs), LLaMA and LLaVA, when answering visual questions with single constraints. It uses the MULTIMODALCAUSALTRACE method, demonstrating that early layers are crucial for information storage in MLLMs, unlike LLMs which rely more on mid-layer MLPs. The results are consistent across three different datasets.

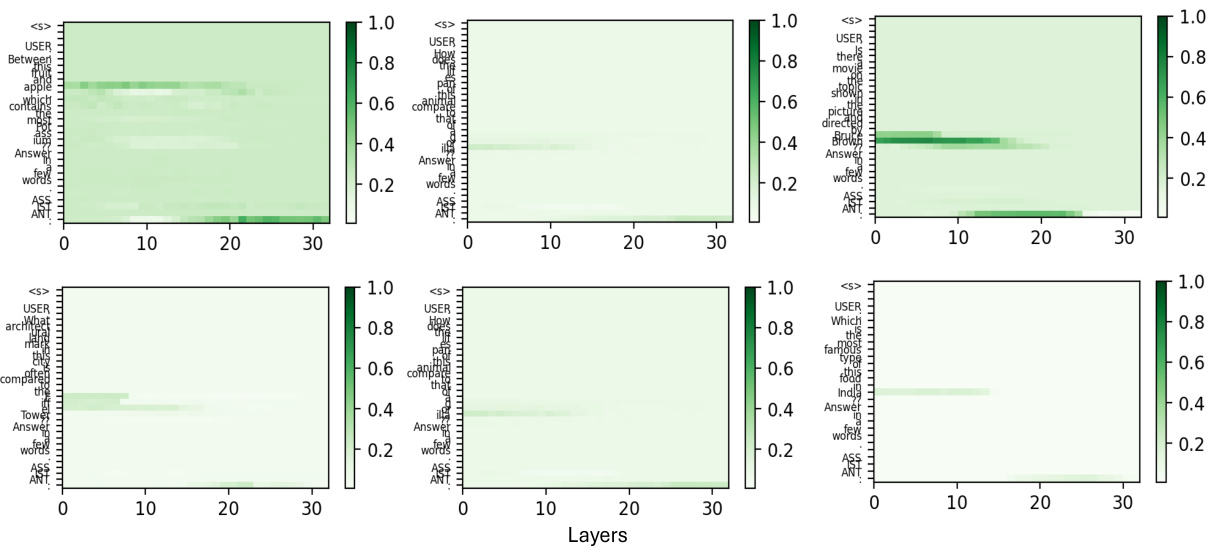

This figure visualizes the results of applying the MULTIMODALCAUSALTRACE method to visual questions that involve both visual and textual constraints. It shows that, unlike single-constraint questions where information retrieval happens mainly from early layers, multi-constraint questions require information from both early and middle MLP and self-attention layers. This difference indicates the necessity of more memory resources for processing questions with multiple constraints.

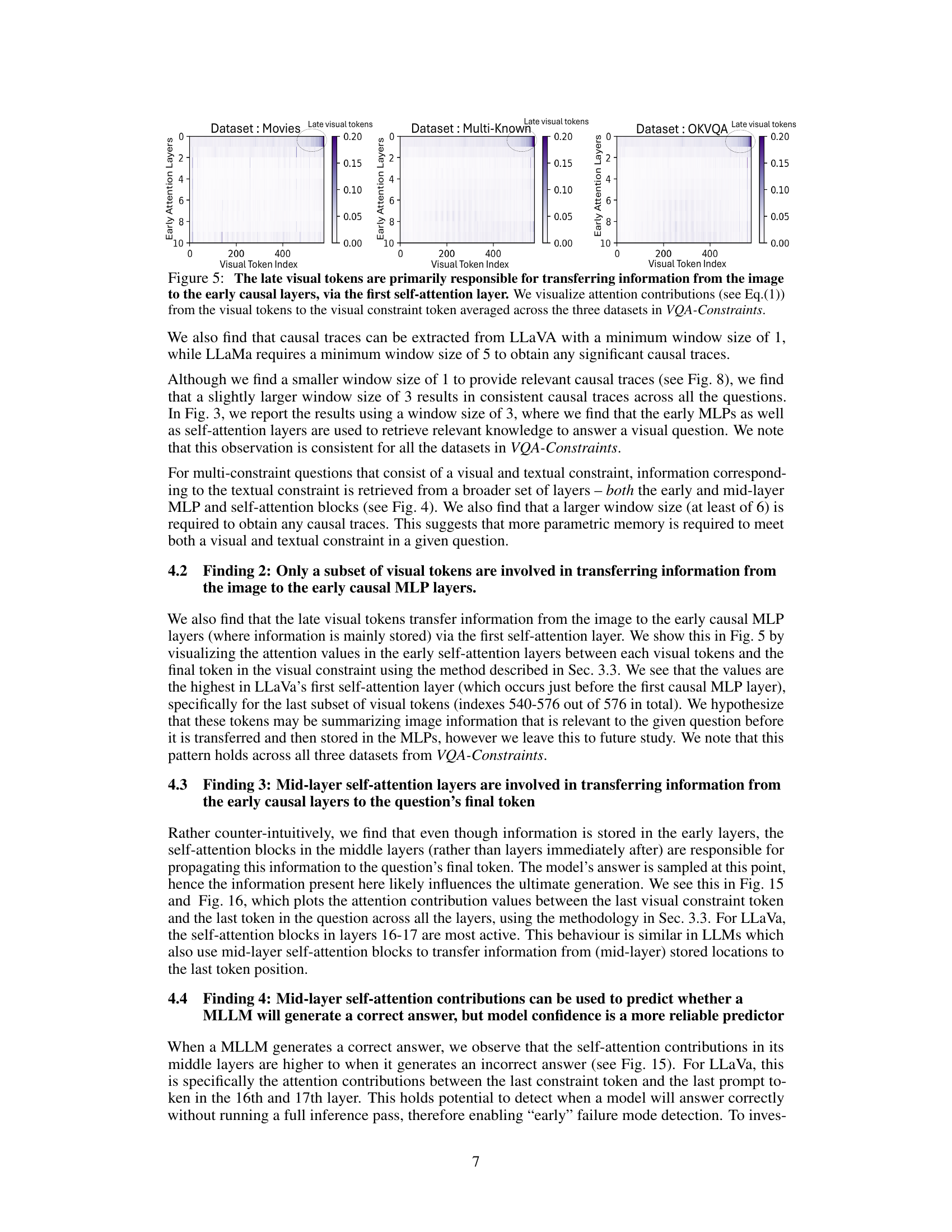

This figure visualizes attention contributions from visual tokens to the visual constraint token across three datasets (Movies, Multi-Known, OKVQA). It shows that the late visual tokens (indices 540-576 out of 576) are most influential in transferring information to early causal layers via the first self-attention layer. The difference in window size needed to extract causal traces between LLaVA (minimum 1) and LLaMA (minimum 5) is highlighted, suggesting a difference in how these models store information.

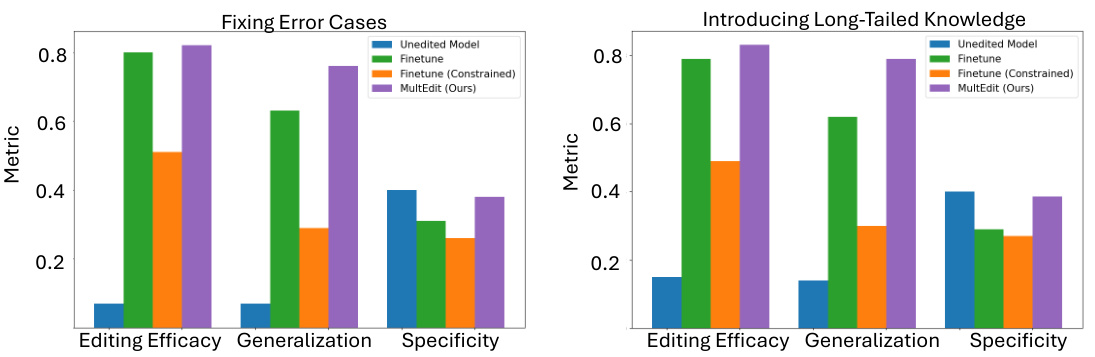

This figure compares the performance of MULTEDIT against fine-tuning baselines (with and without constraints) for correcting errors and inserting long-tailed knowledge. The results show MULTEDIT’s superiority across various metrics: Editing Efficacy (correcting errors), Generalization (applying corrections to similar but slightly different questions), and Specificity (maintaining the accuracy on unrelated questions). It highlights MULTEDIT’s ability to effectively edit a model’s causal layers for improved performance.

This figure compares the causal importance of different layers in two multi-modal large language models (MLLMs), LLaVA-7B and LLaMA (Vicuna)-7B, and contrasts them with their single-modal counterparts. It shows that MLLMs tend to retrieve information from much earlier layers (layers 1-4) compared to LLMs (layers 4-7). The window size needed to identify these causal sites is also smaller for MLLMs (window size of 1) than for LLMs (window size of 5). This suggests a difference in how MLLMs store and access factual information.

This figure compares the causal importance of different layers in two types of large language models (LLMs): Multimodal LLMs (MLLMs) and LLMs, using two specific models, LLaVa-7B and LLaMA (Vicuna)-7B respectively. The causal importance is represented by the probability that manipulating the activation of specific layers affects the model’s output. The figure shows that MLLMs (LLaVa-7B in this case) primarily use the early layers (layers 1-4) for information retrieval, whereas LLMs (LLaMA in this case) primarily utilize the middle layers (layers 4-7). Further, the figure highlights the varying window sizes required to identify causal layers in these two model types.

This figure compares the causal importance of different layers in two multi-modal large language models (MLLMs), LLaVA-7B and LLaMA (Vicuna)-7B, and contrasts them with a large language model (LLM), LLaMA. The causal importance is measured by the indirect estimation effect on the model’s output. It shows that MLLMs utilize earlier layers (layers 1-4) for information retrieval compared to LLMs which rely on mid-layer MLPs (layers 4-7). The size of the layer window considered to identify causal sites also differs between MLLMs and LLMs.

This figure compares the causal importance of different layers in two multi-modal large language models (MLLMs), LLaVa-7B and LLaMA (Vicuna)-7B, and contrasts them with a large language model (LLM). The causal importance is measured using a method called causal tracing. The figure shows that MLLMs tend to retrieve information from much earlier layers (layers 1-4) than LLMs (layers 4-7). The window size needed to identify causal sites also differs between the models, with LLaVa-7B requiring a smaller window size (1) than LLaMA (Vicuna)-7B (5). This suggests that the information storage and retrieval mechanisms may be different for MLLMs compared to LLMs.

This figure compares the causal importance of different layers in two multi-modal large language models (MLLMs), LLaVa-7B and LLaMA (Vicuna)-7B, and one large language model (LLM), LLaMA. The causal importance is measured using a causal tracing method, and it shows that MLLMs utilize information from much earlier layers than LLMs. LLaVa-7B, in particular, exhibits high causal importance in the very first MLP layers, whereas LLaMA relies more on mid-layer MLPs. The difference in window sizes needed to observe the effects is another notable point.

This figure compares the causal importance of different layers in two multi-modal large language models (MLLMs), LLaVA-7B and LLaMA (Vicuna)-7B, and contrasts them with a large language model (LLM). The causal importance is measured by assessing the impact of each layer on the final output. The figure shows that MLLMs rely on information stored in much earlier layers (layers 1-4 for LLaVA-7B), as opposed to LLMs, which typically use mid-layer MLPs. It highlights the difference in the extent of parameter memory required for the two model types.

This figure compares the causal importance of different layers in Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) and Large Language Models (LLMs). The causal importance is measured by how much the activation of a layer affects the model’s final output. The figure shows that MLLMs, specifically LLaVa-7B, rely on much earlier layers (MLP layers 1-4) for information storage compared to LLMs, which rely on mid-layer MLPs (layers 4-7). Furthermore, LLMs may require a larger window size to identify these causal sites, indicating a difference in how information is stored and processed across these model types.

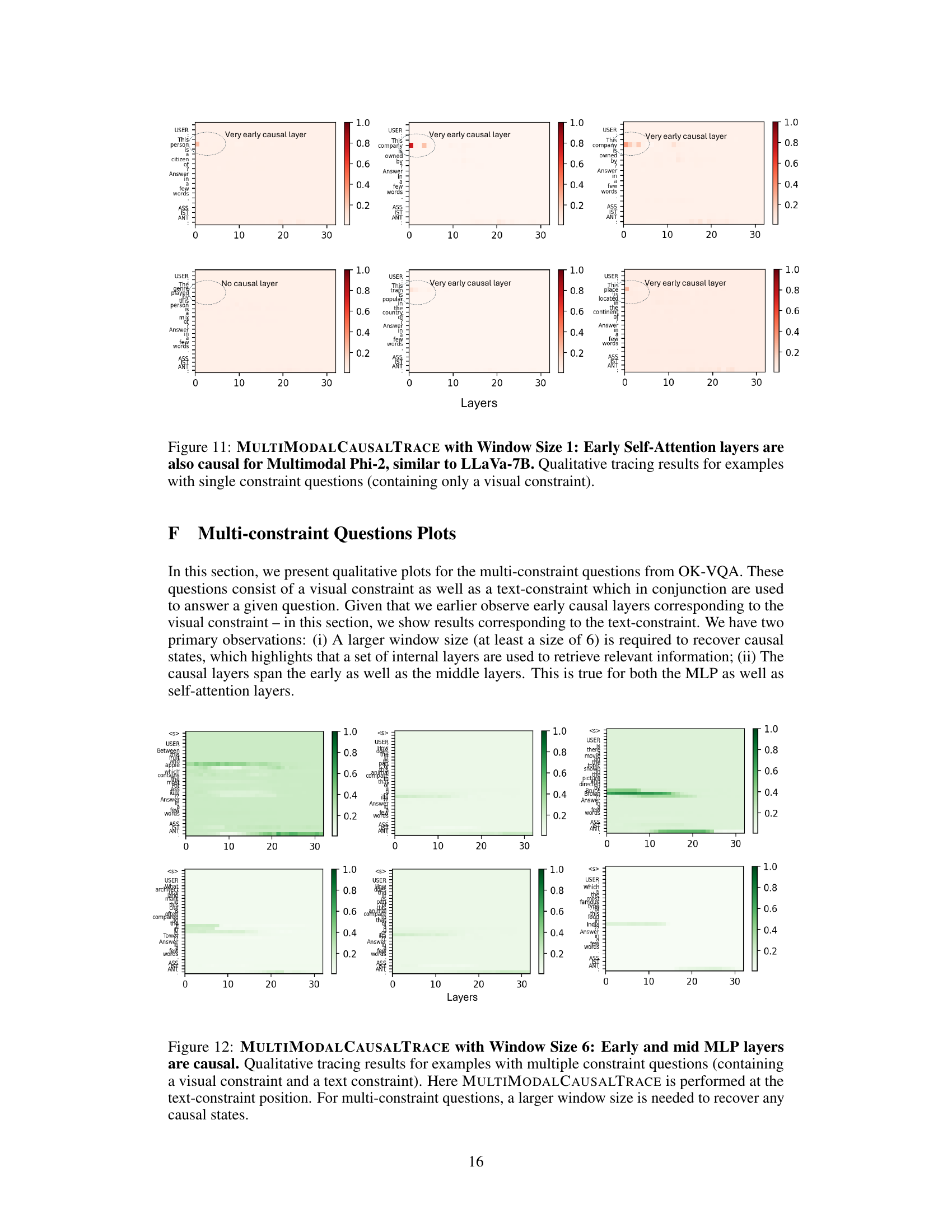

This figure shows the results of applying MULTIMODALCAUSALTRACE with a window size of 6 to examples with multiple constraints (visual and textual). Unlike single-constraint examples, where early layers were causal, multi-constraint examples show causality in both early and mid-layer MLPs and self-attention blocks. This suggests that more layers are involved in processing information when multiple constraints need to be satisfied.

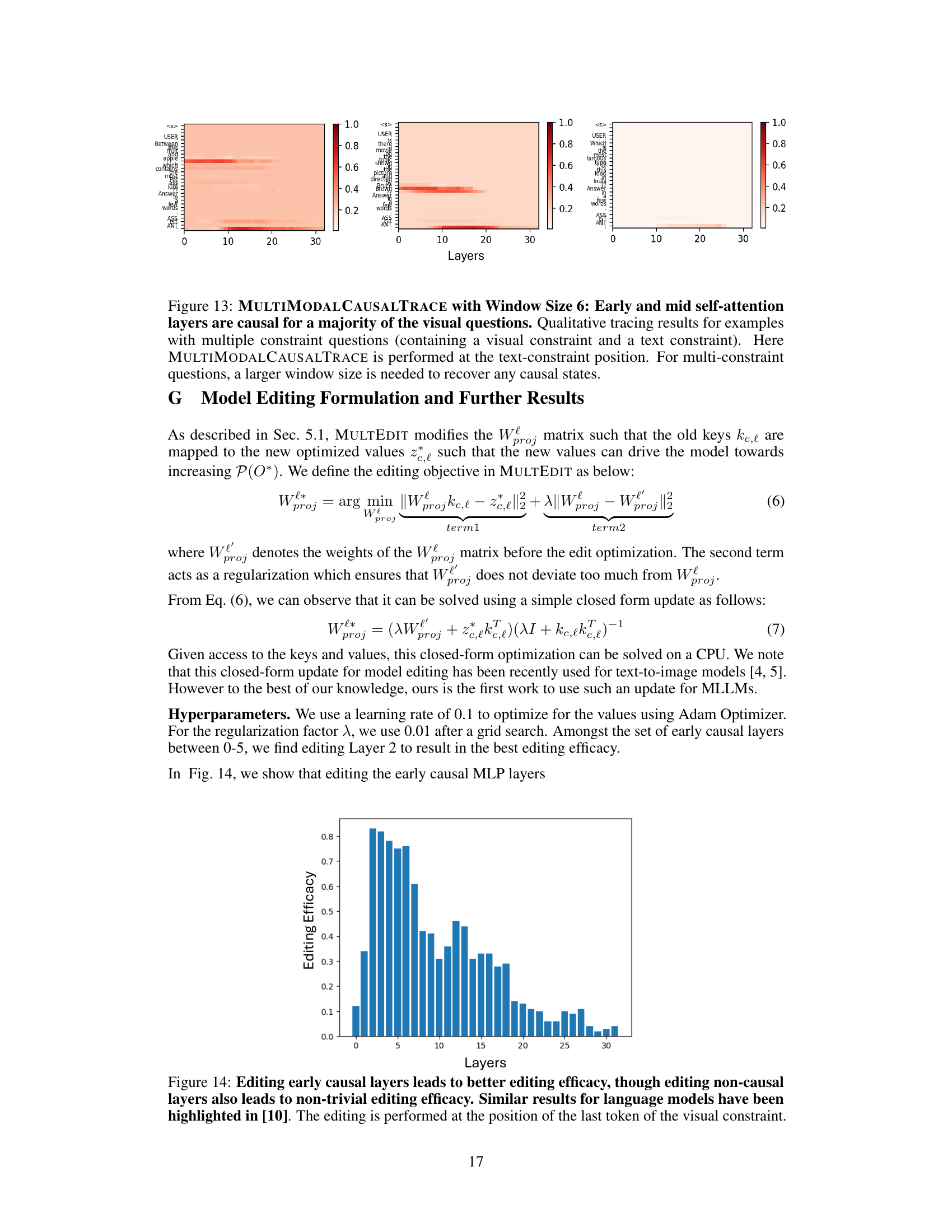

This figure shows the editing efficacy of MULTEDIT when applied to different layers of the model. The x-axis represents the layers of the model, and the y-axis represents the editing efficacy, which is a measure of how well the model is able to correct errors or insert new information. The figure shows that editing the early causal layers (layers 1-4) leads to the best editing efficacy. However, editing the middle or later layers can also lead to some improvement in editing efficacy, although it is less effective than editing the early causal layers. This suggests that the early causal layers play a crucial role in the model’s ability to store and retrieve information.

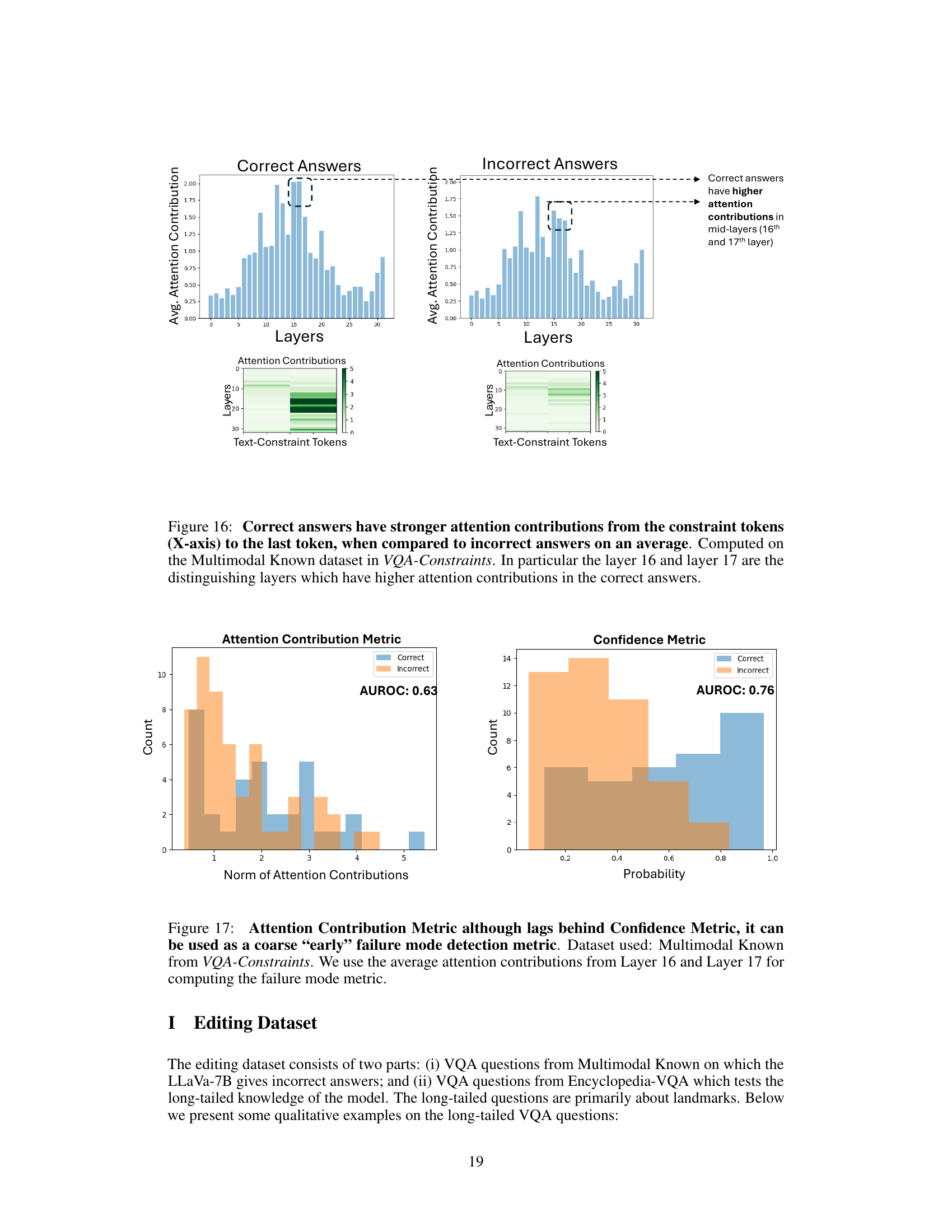

This figure visualizes the attention contributions from constraint tokens to the last token in different layers for both correct and incorrect answers. It shows that correct answers exhibit stronger attention contributions, particularly in layers 16 and 17, highlighting the role of these layers in distinguishing correct from incorrect responses.

The figure shows a comparison of attention contributions between correct and incorrect answers for a visual question answering task. The top plots display average attention contributions across layers for both correct and incorrect responses, highlighting significantly higher contributions in mid-layers (16 and 17) for correct answers. Below, heatmaps visualize attention contributions from constraint tokens (x-axis) to the final token (last token) across layers for both correct and incorrect cases. These heatmaps reinforce the observation of substantially stronger attention contributions in mid-layers (16 and 17) when the model generates correct answers.

This figure shows the performance of two metrics for predicting whether a model will generate a correct answer: the attention contribution metric and the confidence metric. The attention contribution metric uses the average attention contributions from layers 16 and 17, while the confidence metric uses the model’s confidence in its answer. The AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) is shown for both metrics, indicating that the confidence metric is a stronger predictor of correctness than the attention contribution metric, although the attention contribution metric can still provide a useful early indicator of model failure.

This figure shows six examples of images and questions from the Encyclopedia-VQA dataset used in the paper’s experiments on inserting long-tailed knowledge into the model. Each example contains an image of a landmark and a question asking for the landmark’s location. These examples represent the type of challenging questions that the model-editing technique was designed to handle.

This figure shows six example images from the Encyclopedia-VQA dataset used to test the MULTEDIT model’s ability to insert long-tailed knowledge. Each image is accompanied by a question about the location (country) of the landmark shown. The questions are designed to be challenging for large language models, as they involve less common geographic knowledge.

This figure shows six example images from the Encyclopedia-VQA dataset used in the paper’s long-tailed knowledge editing experiments. Each image is accompanied by a question asking for the country where the landmark is located. These examples highlight the challenge of handling less frequently seen landmarks (long-tailed data) that are not well represented in the typical training sets used for multi-modal large language models (MLLMs).

This figure shows six example images from the Encyclopedia-VQA dataset used in the paper’s long-tailed knowledge editing experiments. Each image is accompanied by a question about the location (country) of the landmark shown in the image. These examples illustrate the types of questions used to evaluate the model’s ability to handle less commonly seen factual information.

This figure shows six example images from the Encyclopedia-VQA dataset used in the paper’s experiments on inserting long-tailed knowledge into MLLMs. Each image is accompanied by a question asking the country where the landmark is located. These examples highlight the challenges of handling less common or rare landmarks during MLLM training and evaluation.

This figure shows six example images from the Encyclopedia-VQA dataset used in the paper’s long-tailed knowledge editing experiments. Each image is accompanied by a question about the location (country) of the landmark shown. These examples highlight the challenging nature of the long-tailed knowledge questions that the MULTEDIT algorithm was tested on.

Full paper#