↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Adapting large cloud models for specific tasks is a major challenge in computer vision. Existing domain adaptation methods often require access to source data or high domain similarity, which limits their practicality. This constraint is particularly relevant to the domain of object detection, where transferring knowledge from powerful, pre-trained cloud detectors to specific target domains is crucial but challenging. This paper addresses these issues by proposing a novel approach.

The proposed COIN method tackles this challenge by using a divide-and-conquer approach to integrate knowledge from both a large cloud model and a vision-language model (CLIP). It leverages consistent and private detections to effectively train a target detector. Inconsistent detections are handled using a novel gradient direction alignment technique, aligning the gradients of inconsistent detections with those of consistent ones. The method shows state-of-the-art performance across multiple datasets. This approach is significant because it allows for effective adaptation even when source data is unavailable and domain similarity is limited.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to cloud object detector adaptation (CODA), a significant challenge in domain adaptation. It presents a solution to train target detectors effectively using only knowledge from readily available large cloud models and a public vision-language model, potentially improving the efficiency of various real-world applications. Its divide-and-conquer strategy offers a new perspective on knowledge integration, which is highly valuable for researchers working on related domains.

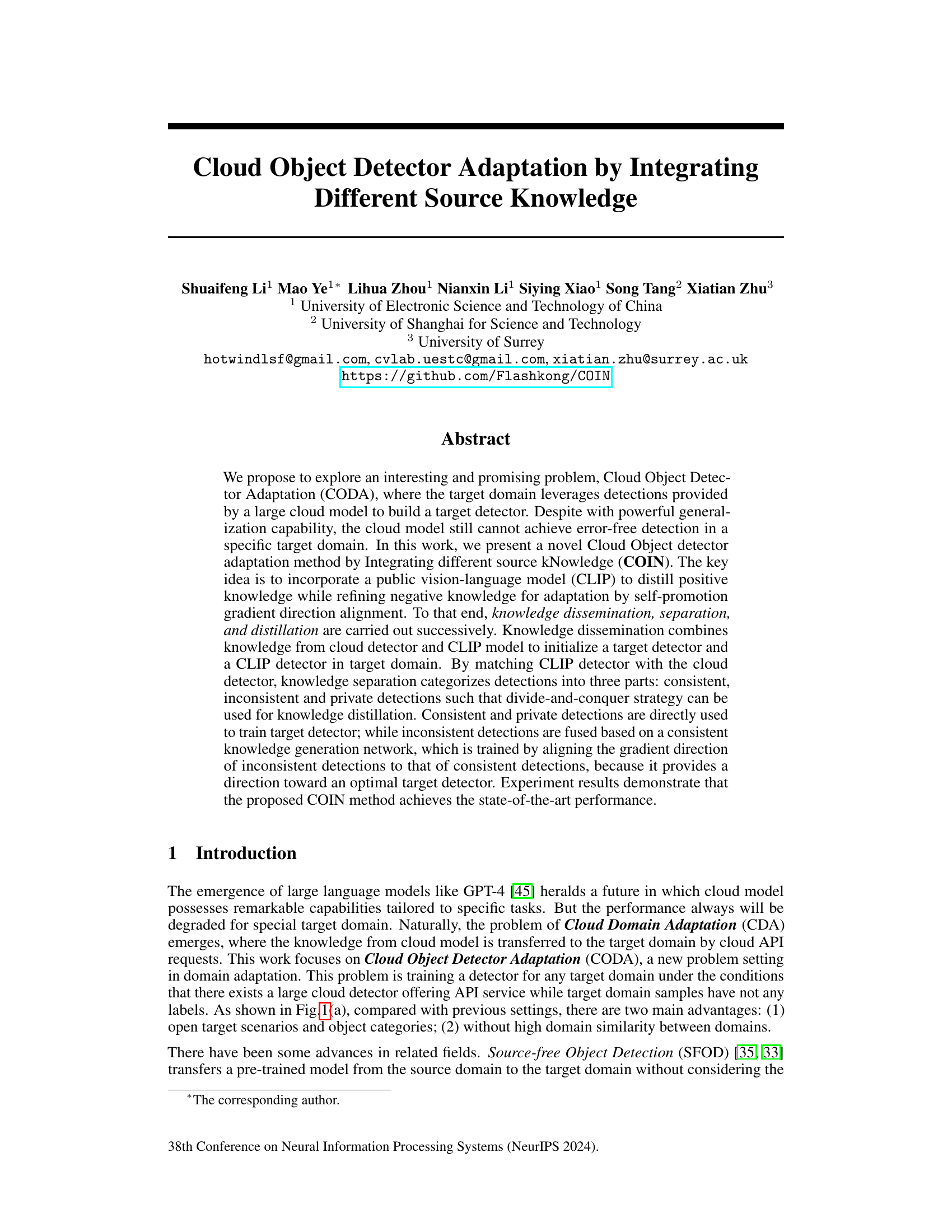

Visual Insights#

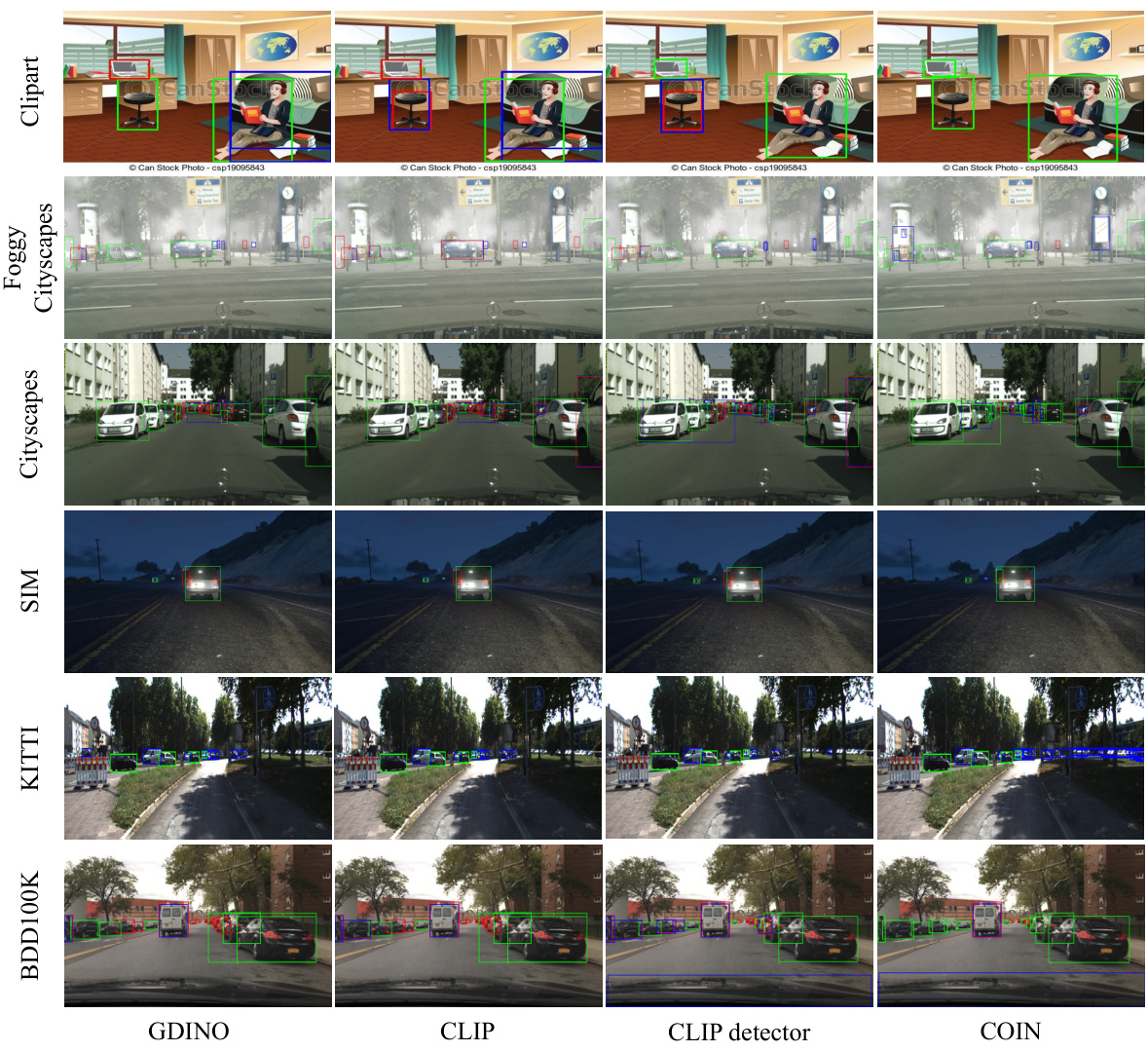

This figure compares the proposed Cloud Object Detector Adaptation (CODA) method with other existing domain adaptation methods such as UDAOD, SFOD, and Black-box DAOD. It also illustrates the three stages of the CODA method: knowledge dissemination, separation, and distillation. The knowledge dissemination stage initializes the cloud and target detectors, while the separation stage categorizes detections into consistent, inconsistent, and private parts. Finally, the distillation stage uses consistent detections to train the target detector and aligns the gradient direction of inconsistent detections to that of consistent detections.

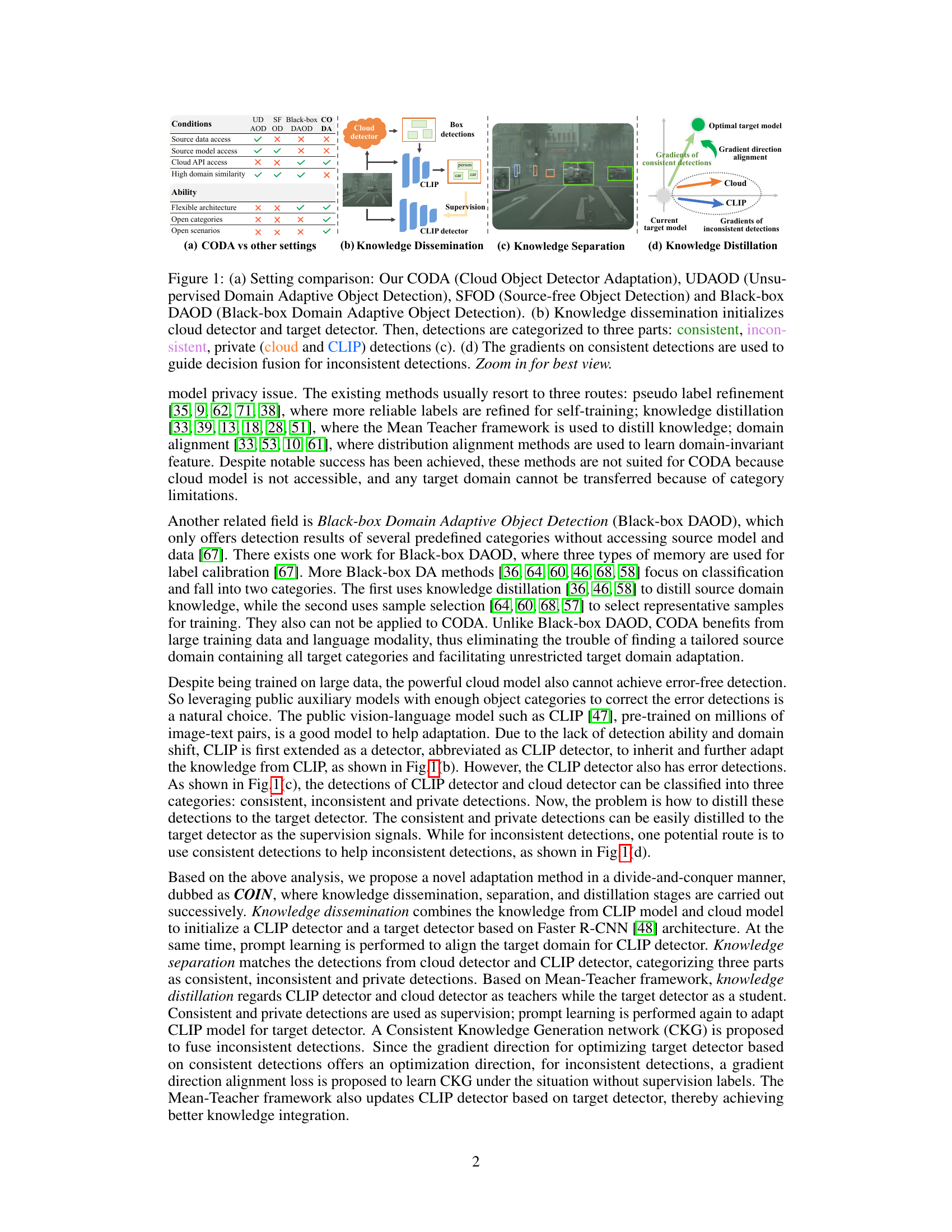

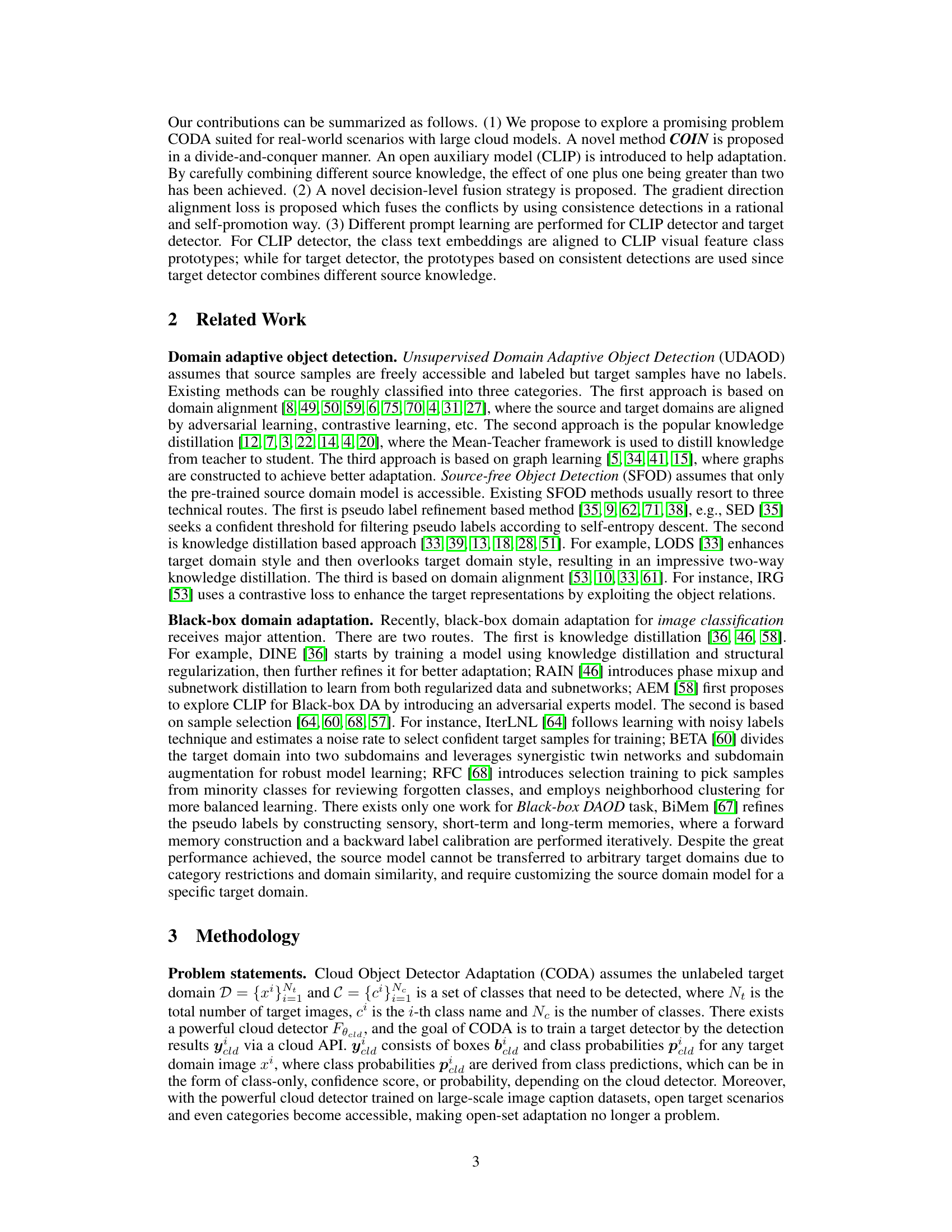

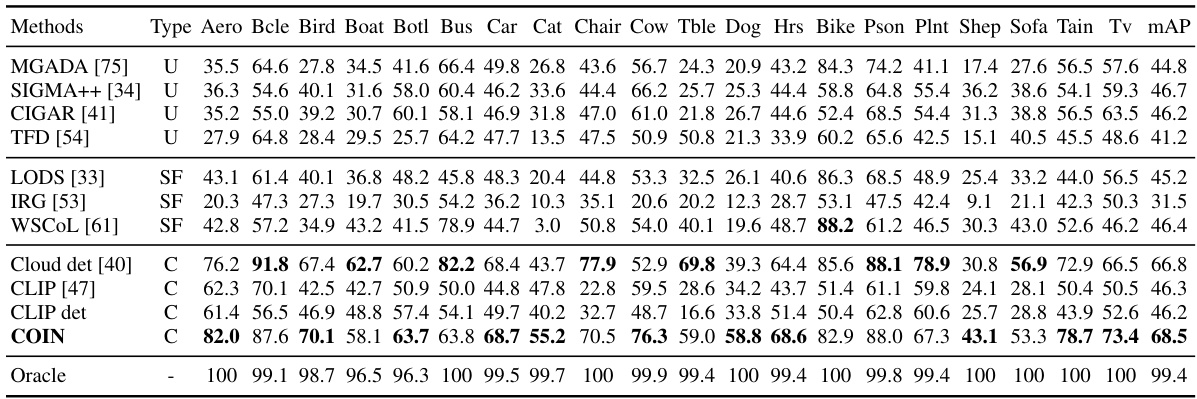

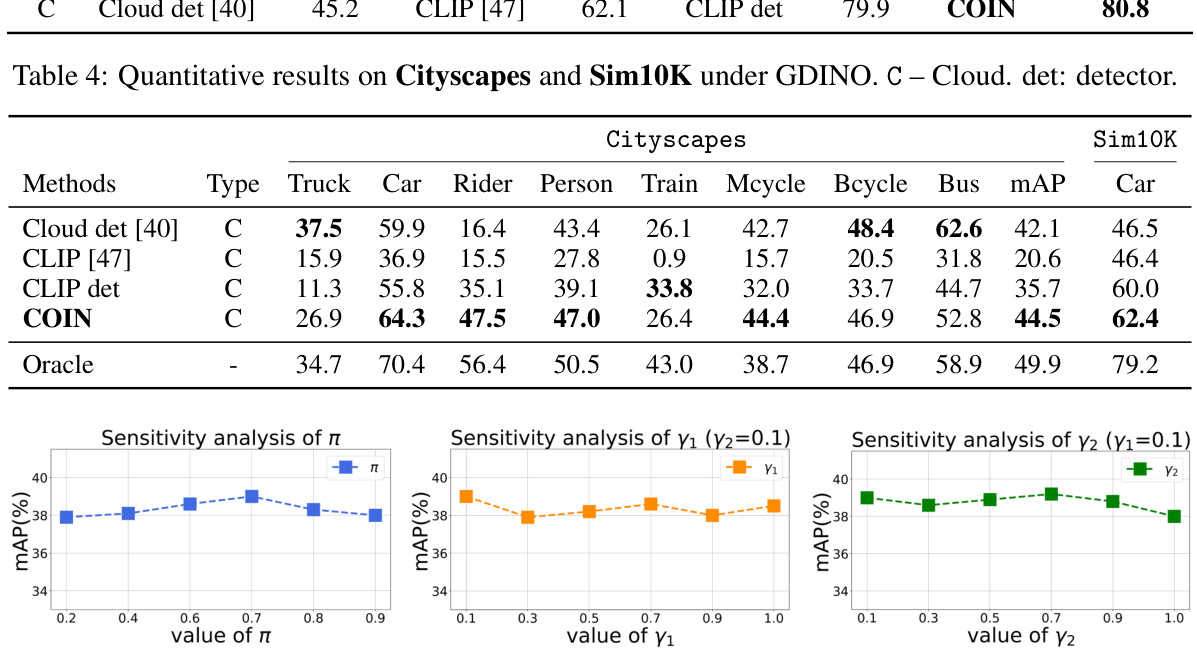

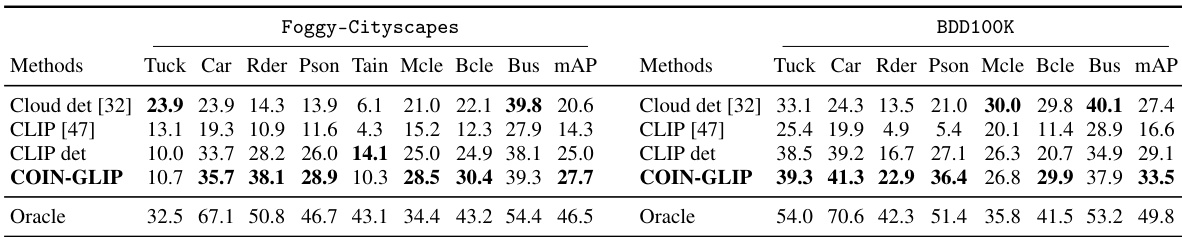

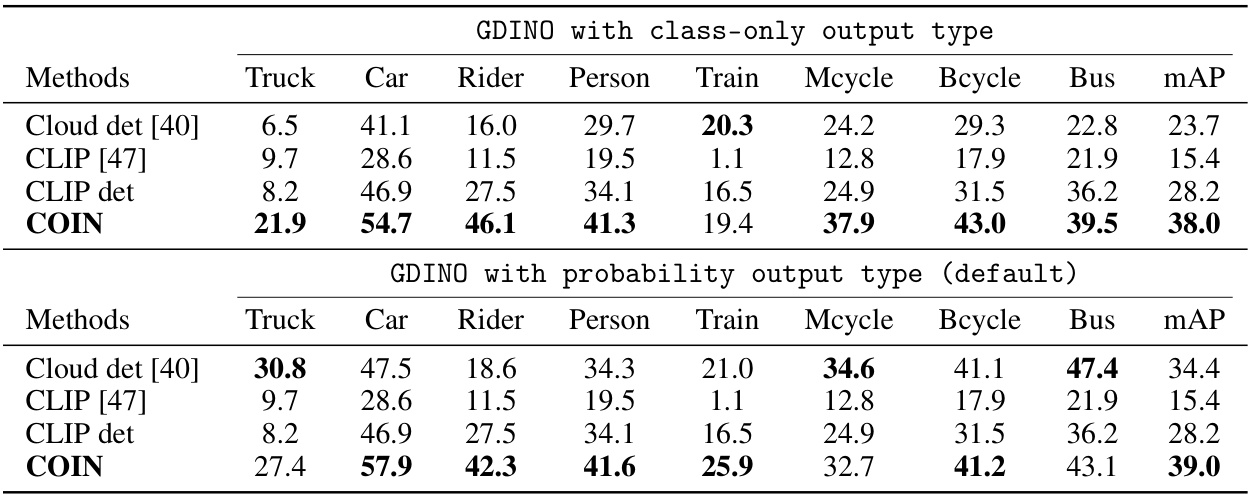

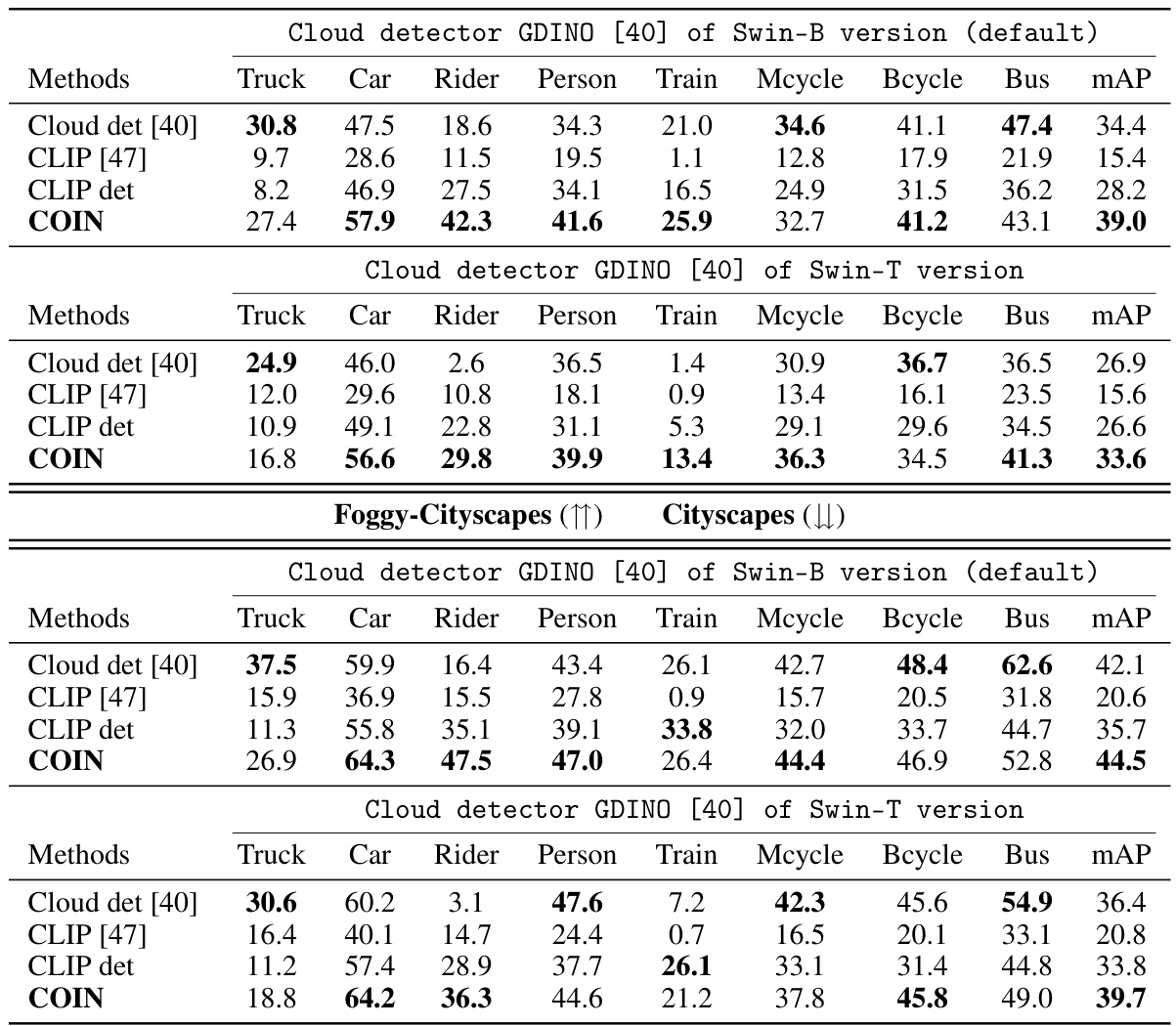

This table presents the results of object detection experiments on two datasets, Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K, using the GDINO model. It compares different object detection adaptation methods across four scenarios: unsupervised (U), source-free (SF), black-box (BB), and cloud (C). The table shows the mean average precision (mAP) achieved by each method for various object categories (Truck, Car, Rider, Person, Train, Motorcycle, Bicycle, Bus). The ‘Oracle’ row indicates the performance achievable with perfect labels for the target domain.

In-depth insights#

CODA Problem#

The CODA (Cloud Object Detector Adaptation) problem tackles the challenge of adapting a powerful cloud-based object detection model to a specific, limited target domain. The core issue is the discrepancy between the source (cloud) and target domains, leading to suboptimal performance in the target domain even with a well-generalizing cloud model. The problem’s novelty lies in leveraging readily available cloud detectors through APIs, without needing direct access to the source model or training data. This opens up new possibilities for adapting object detection to diverse scenarios with limited labeled data, making it particularly useful in specialized domains like medical imaging or robotics where acquiring large labeled datasets can be difficult. The challenge emphasizes the need for innovative techniques in transfer learning and domain adaptation, especially those focused on knowledge distillation and overcoming issues like domain shift and model privacy constraints. Solutions require creative methods to extract useful knowledge from the cloud detector’s outputs, adapt this knowledge to the target domain using potentially limited target domain data, and overcome the inherent limitations of black-box access to the source model.

COIN Method#

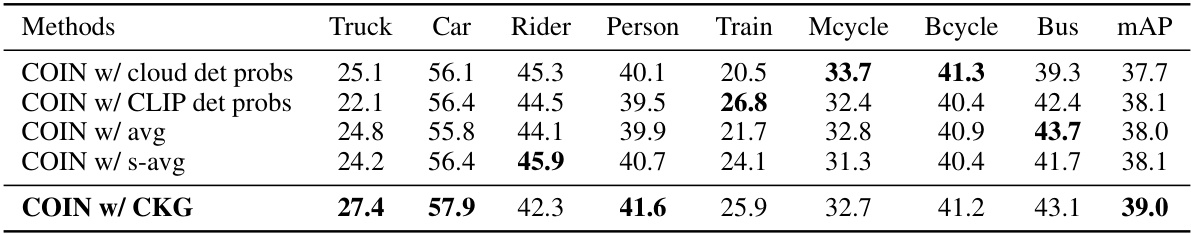

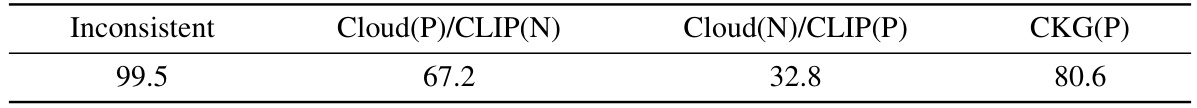

The COIN method, as described in the research paper, presents a novel approach to cloud object detector adaptation (CODA). It cleverly integrates diverse knowledge sources, primarily leveraging a large pre-trained cloud object detector and a vision-language model (CLIP), to build a robust target detector. The method’s core strength lies in its divide-and-conquer strategy, categorizing detections into consistent, inconsistent, and private sets. This allows for selective knowledge distillation, with consistent and private detections directly used to train the target detector. Inconsistent detections, often a source of error, are intelligently fused using a Consistent Knowledge Generation (CKG) network, guided by gradient direction alignment. This innovative alignment ensures that the inconsistent gradients move toward the optimal direction established by the consistent ones, leading to improved target detector performance. COIN also incorporates prompt learning to effectively adapt the CLIP model to the target domain, enhancing the synergy between knowledge sources. The overall approach is a significant advancement in CODA, addressing the challenges of limited labeled data and domain shift in specialized target scenarios. Experimental results strongly support COIN’s effectiveness.

Knowledge Distillation#

Knowledge distillation, in the context of this research paper, is a crucial technique for adapting a cloud object detector to a specific target domain. The core idea is to leverage knowledge from multiple sources, namely a pre-trained cloud detector and a vision-language model (CLIP), to effectively train a target detector. This process cleverly addresses the challenge of limited or nonexistent labeled data in the target domain. The approach involves dividing the detections into three categories: consistent, inconsistent, and private. This division enables a divide-and-conquer strategy, where consistent and private detections directly contribute to training the target detector. Inconsistent detections, which represent conflicts between the cloud and CLIP models, are handled via a consistent knowledge generation network (CKG). The CKG learns to align the gradient direction of inconsistent detections with consistent ones, pushing the learning towards an optimal target detector. This multi-source knowledge integration strategy is critical for superior performance as it combines the strengths of different models, thereby achieving a state-of-the-art result.

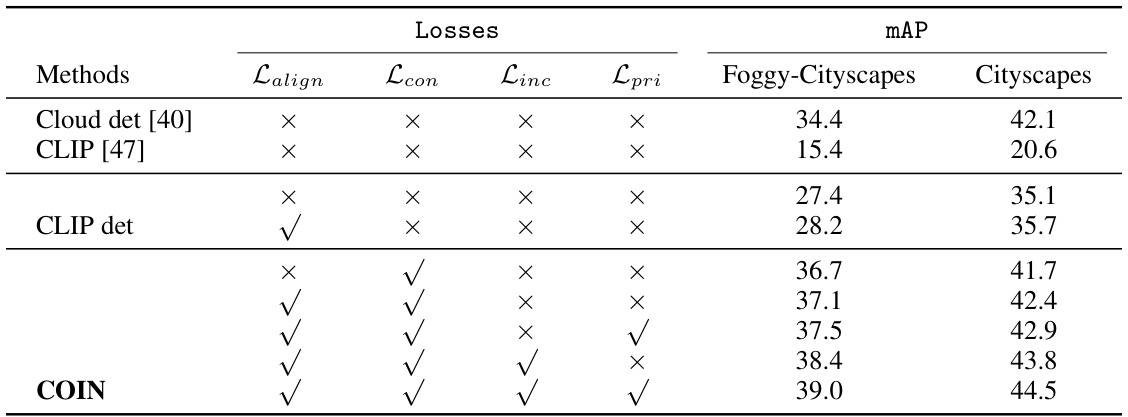

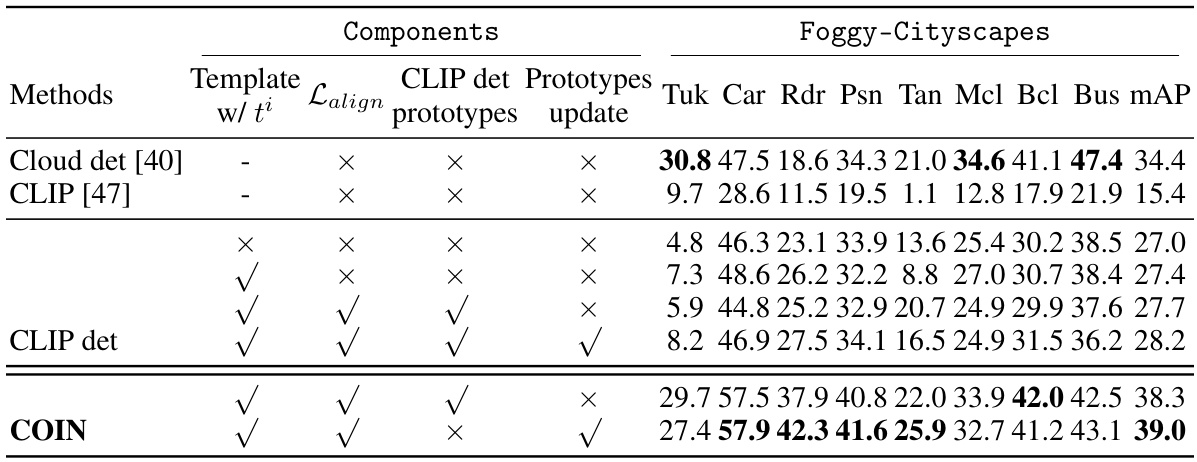

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In this context, it would likely involve removing or deactivating elements of the COIN architecture (knowledge dissemination, separation, distillation, the CKG network, prompt learning, etc.) to understand their impact on the overall performance. The results would show which components are crucial for the model’s success and which might be redundant or even detrimental. A well-executed ablation study should use a controlled experimental design, comparing the full model against multiple variants where individual components are ablated. By carefully analyzing the changes in performance, valuable insights can be gained into the design and workings of the COIN architecture, allowing for improvements and providing a better understanding of how each component contributes to the overall efficacy. For example, ablating the consistent knowledge generation network (CKG) might reveal whether fusing inconsistent detection signals significantly improves results, or if a simpler fusion method would be equally effective. The ablation study could also investigate the impact of hyperparameter settings, such as those determining the threshold for assigning consistent vs. inconsistent detections. It is crucial to quantify the effect of each ablation and to rigorously analyze the statistical significance of any observed differences. This would establish the reliability and robustness of the findings.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this Cloud Object Detector Adaptation (CODA) method could involve exploring alternative auxiliary models beyond CLIP, potentially leveraging models with inherent object detection capabilities for improved efficiency and accuracy. Investigating the impact of different cloud model architectures on CODA performance would also be valuable. Adapting COIN to handle more complex scenarios, such as those with significant variations in object appearance or challenging weather conditions, presents a promising avenue for future work. Furthermore, a thorough investigation into the generalizability of COIN across various object detection frameworks and exploring the potential for incorporating uncertainty estimation into the model to better handle noisy or ambiguous data are crucial next steps. Finally, studying the trade-offs between model accuracy and computational efficiency, especially in resource-constrained environments, remains a key area for advancement.

More visual insights#

More on figures

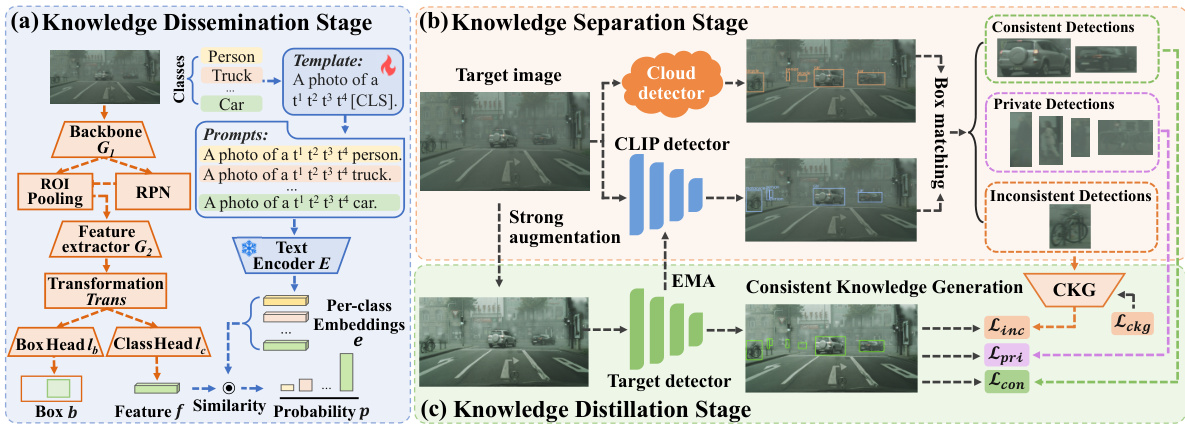

This figure illustrates the COIN method’s three stages: knowledge dissemination, separation, and distillation. The knowledge dissemination stage shows how a CLIP model and a cloud detector are combined to initialize a CLIP detector and a target detector. The knowledge separation stage shows how detections from these two detectors are categorized into consistent, inconsistent, and private detections. Finally, the knowledge distillation stage details how these three types of detections are used to train the target detector, with a focus on how the gradient direction alignment loss is used to fuse inconsistent detections.

The figure shows the architecture of the Consistent Knowledge Generation (CKG) network, a key component in the COIN method. The CKG network fuses inconsistent detections from the cloud detector and the CLIP detector. It uses cross-attention modules to compute adaptive weights for each detection based on its features and the class prototypes from both detectors. These weights are then used to generate refined probabilities that align with the consistent detections, thus improving the overall accuracy of the target detector. The use of cross-attention allows the network to learn relationships between the features of the inconsistent detections and the class prototypes of both detectors effectively handling conflicting information.

This figure illustrates the three main stages of the COIN method: knowledge dissemination, knowledge separation, and knowledge distillation. The knowledge dissemination stage shows how the cloud detector and CLIP model are combined to initialize a CLIP detector and a target detector. The knowledge separation stage demonstrates how detections from the cloud and CLIP detectors are categorized into three groups: consistent, inconsistent, and private detections. Finally, the knowledge distillation stage details how these three types of detections are used to train the target detector, with a focus on how inconsistent detections are handled using gradient direction alignment.

More on tables

This table presents the results of object detection adaptation experiments conducted on the Clipart dataset using the GDINO model. Different adaptation strategies are compared, including unsupervised (U), source-free (SF), and cloud-based (C) approaches. The table shows the mean Average Precision (mAP) achieved by each method across various object categories.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of object detection performance on the KITTI dataset using different methods. The results are broken down by the type of adaptation used (Unsupervised or Cloud-based), and specific methods are compared against each other. The key metric presented is the Average Precision (AP) for the ‘Car’ class.

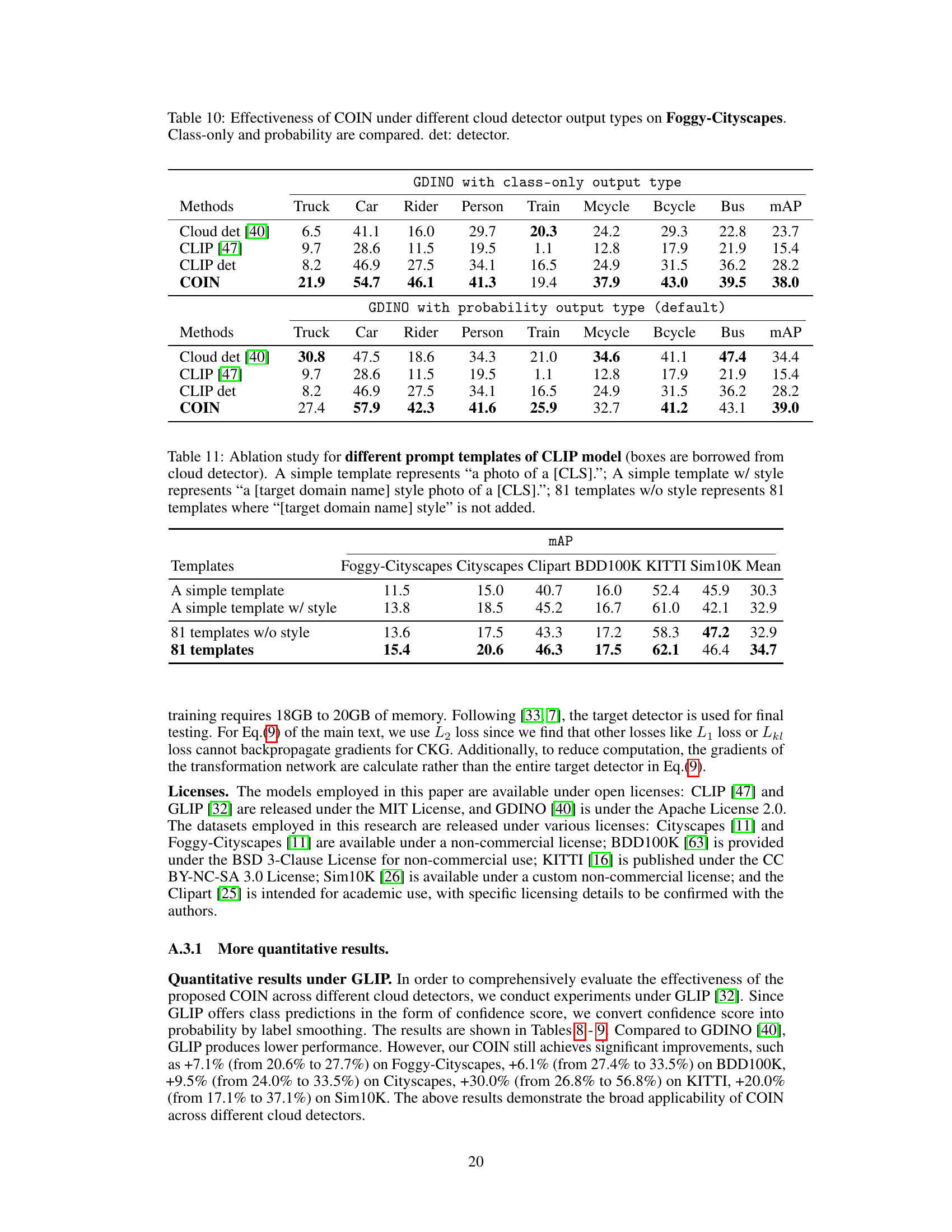

This table presents quantitative results for object detection on the Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K datasets using the GDINO model. It compares various domain adaptation methods, including unsupervised (U), source-free (SF), black-box (BB), and cloud-based (C) approaches. The results are broken down by object class (Truck, Car, Rider, Person, Train, Mcycle, Bcycle, Bus) and overall mean Average Precision (mAP). The table helps illustrate the performance improvements achieved by the COIN method in the context of different adaptation techniques.

This table presents the ablation study results for the proposed COIN method on two datasets, Foggy-Cityscapes and Cityscapes, using GDINO as the object detector. It shows the impact of different components of the COIN model (Lalign, Lcon, Linc, Lpri) on the mAP (mean Average Precision) performance. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of each component and show the improvements in mAP achieved by including each part of the COIN method. It provides a quantitative assessment of the importance of each loss function in the COIN framework for object detection.

This table presents the ablation study for decision-level fusion of inconsistent detections on the Foggy-Cityscapes dataset using the GDINO object detector. Different methods for fusing inconsistent detections are compared: using only cloud detector probabilities, using only CLIP detector probabilities, simple averaging, score-weighted averaging, and the proposed Consistent Knowledge Generation (CKG) network. The results are evaluated based on mAP and per-class AP scores for various object categories (Truck, Car, Rider, Person, Train, Mcycle, Bcycle, Bus). The filtering threshold (π) is set to 0.7 for consistent comparison across methods.

This table presents the quantitative results of various object detection methods on two datasets, Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K, using the GDINO model. The results are categorized by the type of domain adaptation used: Unsupervised (U), Source-free (SF), Black-box (BB), and Cloud (C). The table shows the mean Average Precision (mAP) and precision for different object categories (Truck, Car, Rider, Person, Train, Motorcycle, Bicycle, Bus) for each method and adaptation setting. It compares the performance of the proposed COIN method against existing unsupervised domain adaptation, source-free object detection, and black-box domain adaptive object detection methods, as well as a cloud detector and CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) baseline.

This table presents the quantitative results of various object detection methods on two datasets, Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K, using the GDINO model. The results are categorized by the type of domain adaptation setting used: Unsupervised (U), Source-free (SF), Black-box (BB), and Cloud (C). Each method’s performance is evaluated across multiple object categories (Truck, Car, Rider, Person, Train, Motorcycle, Bicycle, Bus) using the mean Average Precision (mAP) metric. The table allows for a comparison of different domain adaptation strategies and their impact on object detection accuracy.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of object detection performance across three different datasets (Cityscapes, KITTI, and Sim10K) using the GLIP model. The performance metrics include average precision (AP) for various object classes within each dataset. The table allows for a comparison of the baseline cloud detector, the CLIP model, the CLIP detector, and the COIN method to assess the effectiveness of the proposed COIN approach in improving the accuracy of object detection on diverse datasets and diverse object categories.

This table presents the quantitative results of different object detection methods on two datasets: Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K. The results are categorized by the type of domain adaptation setting used (Unsupervised, Source-free, Black-Box, Cloud) and the specific detector used. The table shows the mean Average Precision (mAP) and per-class performance for various object categories. The ‘Cloud det’ row represents the performance of a pre-trained cloud-based object detector used as a starting point for some adaptation techniques. The ‘Oracle’ row indicates the upper bound of performance achievable if true labels were available.

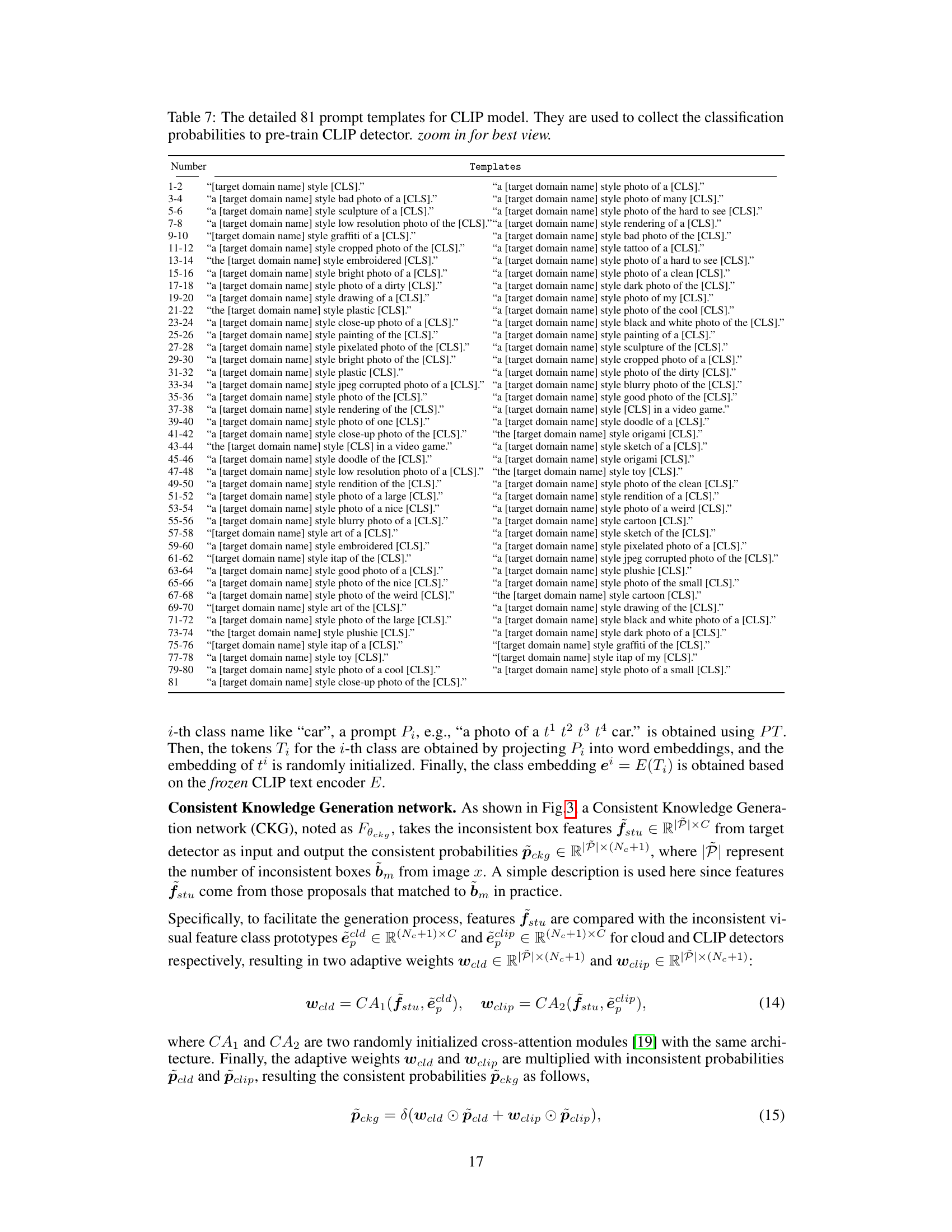

This ablation study investigates the effectiveness of different prompt templates for CLIP model across six datasets. It compares using a simple template, a simple template with added style information, 81 templates without style, and finally, all 81 templates. The results show the impact of incorporating style information and the number of prompts used on model performance across various datasets.

This ablation study investigates the impact of different prompt learning strategies on the performance of the proposed COIN method for object detection adaptation. It compares the effects of using simple prompts, more complex prompts with placeholders, and incorporating exponential moving averages to update prototypes. It also examines the impact of aligning to pre-trained CLIP detector prototypes versus collecting prototypes from consistent detections. The results show the effectiveness of the proposed dual prompt learning method.

This table presents the performance comparison of different object detection methods on two datasets (Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K) using the GDINO model. It shows the mean Average Precision (mAP) and per-class AP for various object categories under different adaptation settings: unsupervised, source-free, black-box, and cloud-based. The results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed COIN method in adapting to the target domains.

This table presents the results of object detection experiments on two datasets, Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K, using the GDINO model. The results are categorized by different domain adaptation settings: unsupervised (U), source-free (SF), black-box (BB), and cloud (C). Each setting uses a different approach to adapt the detector for the respective target domain. The table shows the mean average precision (mAP) and performance metrics for several object classes (Truck, Car, Rider, Person, Train, Motorcycle, Bicycle, Bus) on each dataset and adaptation setting.

This table presents the performance comparison of different object detection methods on two datasets (Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K) using the GDINO model. The methods are categorized by the type of domain adaptation they employ: Unsupervised (U), Source-Free (SF), Black-Box (BB), and Cloud (C). The table shows the mean Average Precision (mAP) and per-class Average Precision (AP) for various object categories like Truck, Car, Rider, Person, Train, Motorcycle, Bicycle, and Bus. The ‘Cloud det’ row represents the results achieved by using a large pre-trained cloud-based object detector. The ‘COIN’ row shows the results obtained using the proposed COIN method in this paper. The ‘Oracle’ row presents the upper bound results using ground truth labels. The table helps to evaluate the effectiveness of COIN compared to existing unsupervised, source-free, and black-box object detection adaptation methods.

This table shows the consistency between the cloud detector (GDINO) and the CLIP detector in identifying inconsistent object detections on the BDD100K dataset. It indicates how often both detectors agree or disagree on whether a detection is correct or incorrect. The numbers represent percentages across 1000 iterations.

This table presents a comparison of the model size and inference speed of the target detector (using ResNet50) and the cloud detector (Swin-B) on a 3090 GPU. The target detector’s size and speed are shown for different numbers of proposals (1000, 500, 300, and 100), reflecting the tradeoff between accuracy and real-time performance in deployment scenarios. The table highlights the significant reduction in model size and the increase in FPS of the target detector compared to the cloud detector, making it more suitable for deployment on resource-constrained devices.

This table presents the results of object detection experiments on two datasets, Foggy-Cityscapes and BDD100K, using the GDINO model. It compares different object detection adaptation methods (Unsupervised, Source-free, Black-box, and Cloud) across various object categories. The metrics include the mean Average Precision (mAP) and per-class precision values for each dataset and method. The table helps analyze how these methods perform in adapting to different levels of difficulty (Unsupervised vs. Source-free vs. Cloud) in object detection.

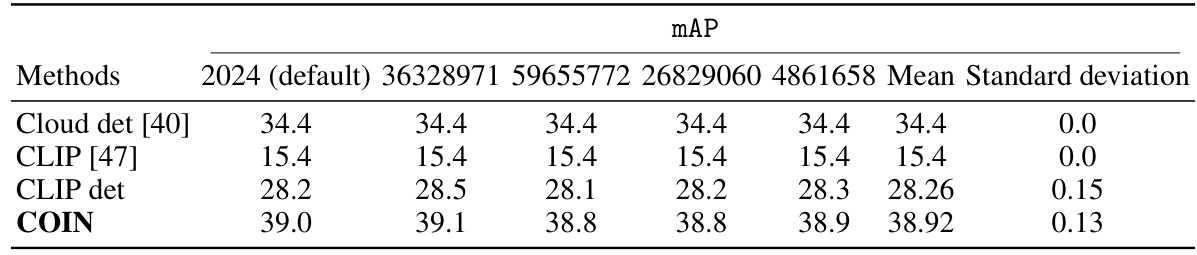

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the mAP scores for five different random seeds on the Foggy-Cityscapes dataset. The purpose is to show the stability and reproducibility of the COIN method. The results are compared for the Cloud detector, CLIP, CLIP detector and COIN methods.

Full paper#