↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Monocular Depth Estimation (MDE) is crucial for autonomous driving, enabling vehicles to perceive their surroundings. However, current MDE models are vulnerable to adversarial attacks, where attackers attach optimized patches to obstacles, causing misjudgments in depth perception. These existing attacks are limited in scope; relying on specific obstacles and having a limited impact.

This paper introduces Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM), a new attack that overcomes the limitations of existing methods. AdvRM deploys patches on roads, disguised as ordinary road markings, making the attack more effective, stealthy, and robust against various MDE models. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrated through simulations and real-world experiments, highlighting the significant threat AdvRM poses to autonomous driving systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer vision and autonomous driving because it highlights a significant vulnerability in monocular depth estimation (MDE) models. By demonstrating a novel adversarial attack that is effective, stealthy, and robust, it underscores the need for more secure and reliable MDE systems. The findings stimulate further research into developing more robust and secure MDE models, and methods to defend against adversarial attacks. This research has practical implications for ensuring the safety and reliability of autonomous vehicles.

Visual Insights#

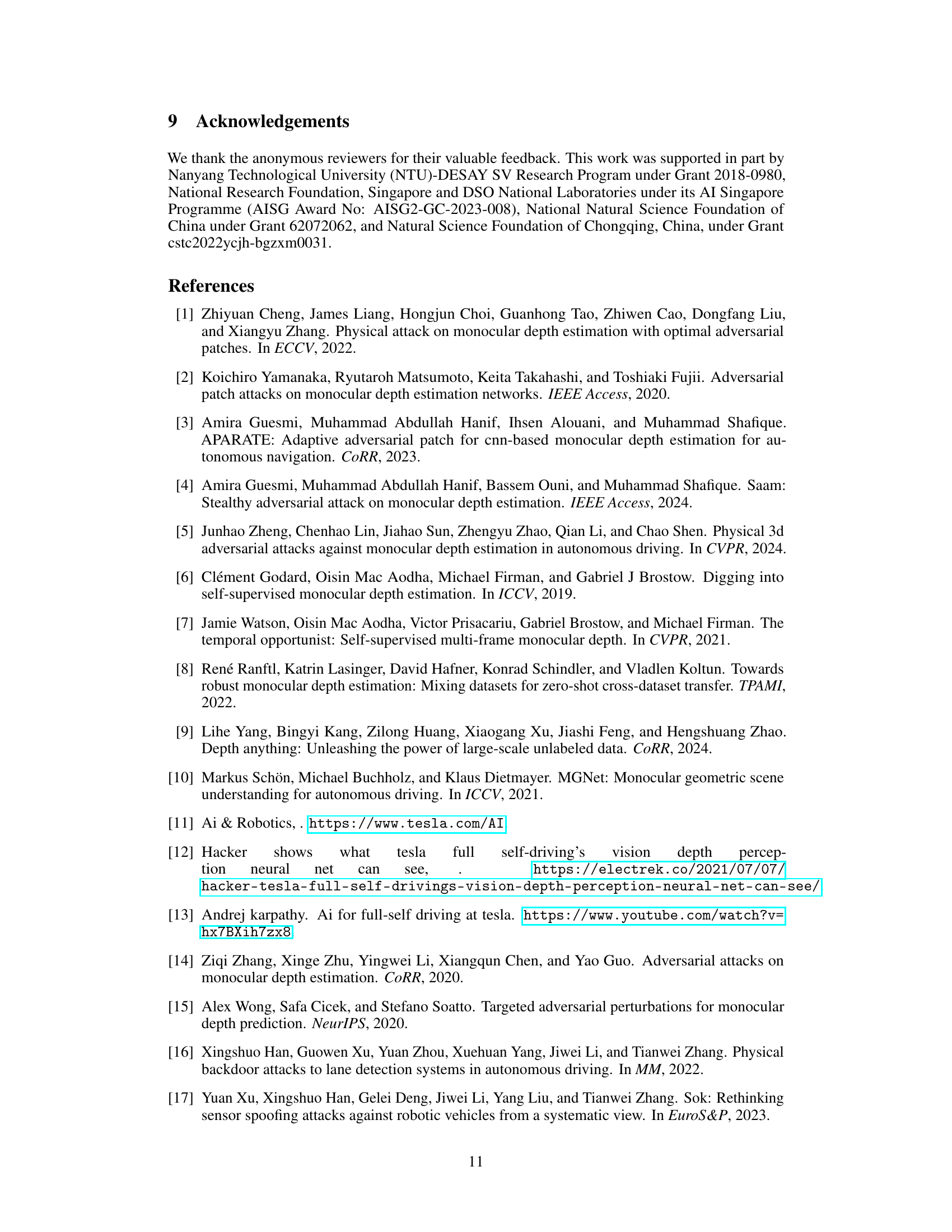

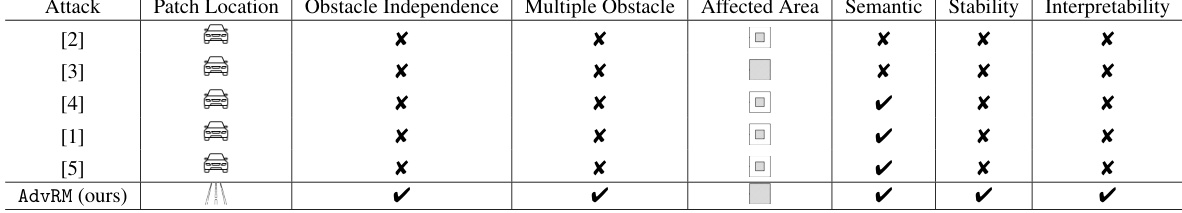

This figure compares the proposed Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack with previous patch-based attacks on Monocular Depth Estimation (MDE) models. The top half shows that previous methods are limited to single obstacles and rely on obstacle-specific patches, which limits their effectiveness and robustness in real-world scenarios. The bottom half illustrates how AdvRM leverages the road dependency of MDE models, placing patches on roads that affect the depth perception of any obstacle within the lane, making it more effective and robust against various MDE models.

This table compares different patch attacks on monocular depth estimation models across several key aspects. It shows whether each attack is independent of specific obstacles, whether it effectively affects multiple obstacles, the size of the affected area, whether the patch blends semantically with the scene, the stability of the attack over time, and whether the rationale behind patch placement is explained. The table highlights the unique advantages of AdvRM (the authors’ proposed attack) compared to previous methods.

In-depth insights#

AdvRM: Patch Attack#

The proposed AdvRM (Adversarial Road Marking) patch attack represents a significant advancement in adversarial attacks against monocular depth estimation (MDE) models. Unlike previous methods that focus on attaching patches to specific obstacles, AdvRM cleverly deploys patches on roads, making the attack obstacle-agnostic and more robust. This approach leverages the discovery that MDE models heavily rely on road regions for depth prediction, which is a fundamental vulnerability. The camouflaging of patches as ordinary road markings adds a layer of stealth, increasing their effectiveness and lifespan in real-world scenarios. The research demonstrates the efficacy of AdvRM across various MDE models, highlighting its potential impact on the safety and reliability of autonomous driving systems. Real-world experiments further validate its robustness and effectiveness, underscoring the need for improved MDE model robustness against such attacks.

Road Dependency#

The concept of “Road Dependency” in the context of monocular depth estimation (MDE) models reveals a crucial vulnerability. MDE models, trained primarily on road-centric datasets, exhibit a strong reliance on road features when estimating depth. This over-reliance means that the models’ predictions are heavily influenced by the presence and characteristics of roads, even when estimating the depth of objects far removed from the road itself. This dependence becomes an exploitable weakness, as adversarial patches strategically placed on or near roads can significantly influence depth estimations for any obstacle within the model’s field of view. The impact is not limited to specific obstacles, but extends to all objects within the affected region. This discovery highlights the importance of considering environmental context and potential biases in MDE training data to improve the robustness and security of autonomous driving systems.

Robustness Analysis#

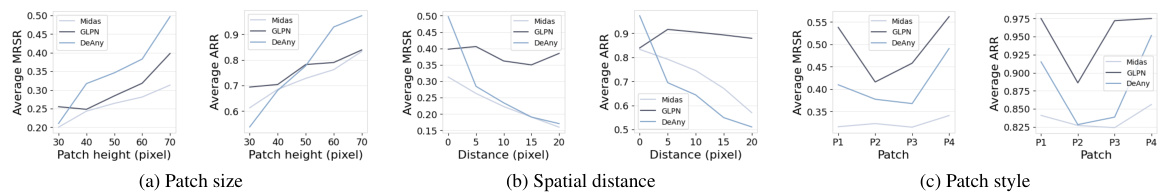

A robust model should maintain accuracy across various conditions. For an adversarial patch attack against monocular depth estimation, robustness analysis would examine how well the attack performs under various conditions. This could include variations in: lighting conditions (day vs. night, shadows), weather (rain, fog), road surface types (asphalt, concrete, dirt), presence of other objects near the patch (cars, pedestrians), and patch placement accuracy. Ideally, a truly robust attack would be successful irrespective of these factors. The analysis needs to quantify the effectiveness of the attack under each condition and assess the model’s resilience against the perturbation. Statistical measures, such as mean relative shift ratio (MRSR) and affect region ratio (ARR), calculated across various conditions, can help provide quantitative evidence of the attack’s robustness. Qualitative assessment through visualization of depth maps across varied scenarios is essential for a comprehensive analysis. Examining the scenarios where the attack fails and exploring potential reasons behind such failures is equally important for both enhancing the attack itself and designing more robust MDE models.

Real-World Tests#

A robust research paper should include a dedicated section on real-world tests to validate its findings beyond simulations. This section’s value lies in bridging the gap between theoretical models and practical applications. Real-world testing demonstrates the effectiveness and limitations of the proposed method under realistic conditions, offering insights that simulations might miss. In the context of this research, real-world tests would likely involve deploying the adversarial patches in actual traffic environments and evaluating their impact on various monocular depth estimation models. This could involve carefully controlled experiments with diverse obstacles and environmental factors, while ensuring safety. The results would reveal the robustness of the attacks in real-world scenarios, including their effectiveness against different weather conditions, lighting, road conditions, and types of obstacles. Furthermore, a crucial aspect of real-world testing is addressing the ethical considerations of deploying adversarial patches. This includes potential safety risks, impact on autonomous vehicle performance, and countermeasures. Finally, real-world results must be analyzed comprehensively, highlighting both successful and failed attacks, thereby providing a comprehensive evaluation and contributing significantly to the understanding of adversarial robustness in monocular depth estimation.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the robustness of MDE models against adversarial attacks is crucial, potentially through developing more resilient architectures or employing advanced defensive techniques. Investigating the transferability of adversarial patches across different MDE models and driving scenarios would enhance the understanding of vulnerabilities and inform the development of more generalizable defenses. Research into more sophisticated camouflage techniques for adversarial patches is needed to improve their stealthiness and effectiveness in real-world settings. Finally, expanding the scope of adversarial attacks to consider other critical perception tasks in autonomous driving, such as object detection and lane recognition, would provide a more comprehensive security assessment. These future directions will be vital in paving the way for secure and reliable autonomous driving systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

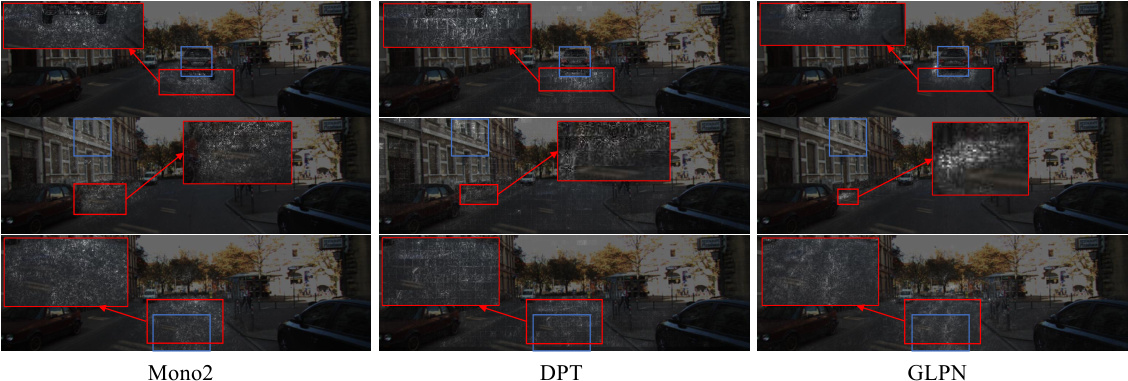

This figure displays saliency maps for three different monocular depth estimation (MDE) models: Mono2, DPT, and GLPN. Each row shows a different input image. The blue boxes highlight areas of interest (objects) in each image. The superimposed saliency maps use white points to indicate the pixels that most strongly influence the model’s depth prediction for the corresponding objects. The red boxes show the areas on the road that appear to significantly affect depth estimation for the objects in the blue boxes, showcasing a strong road-dependency in these MDE models.

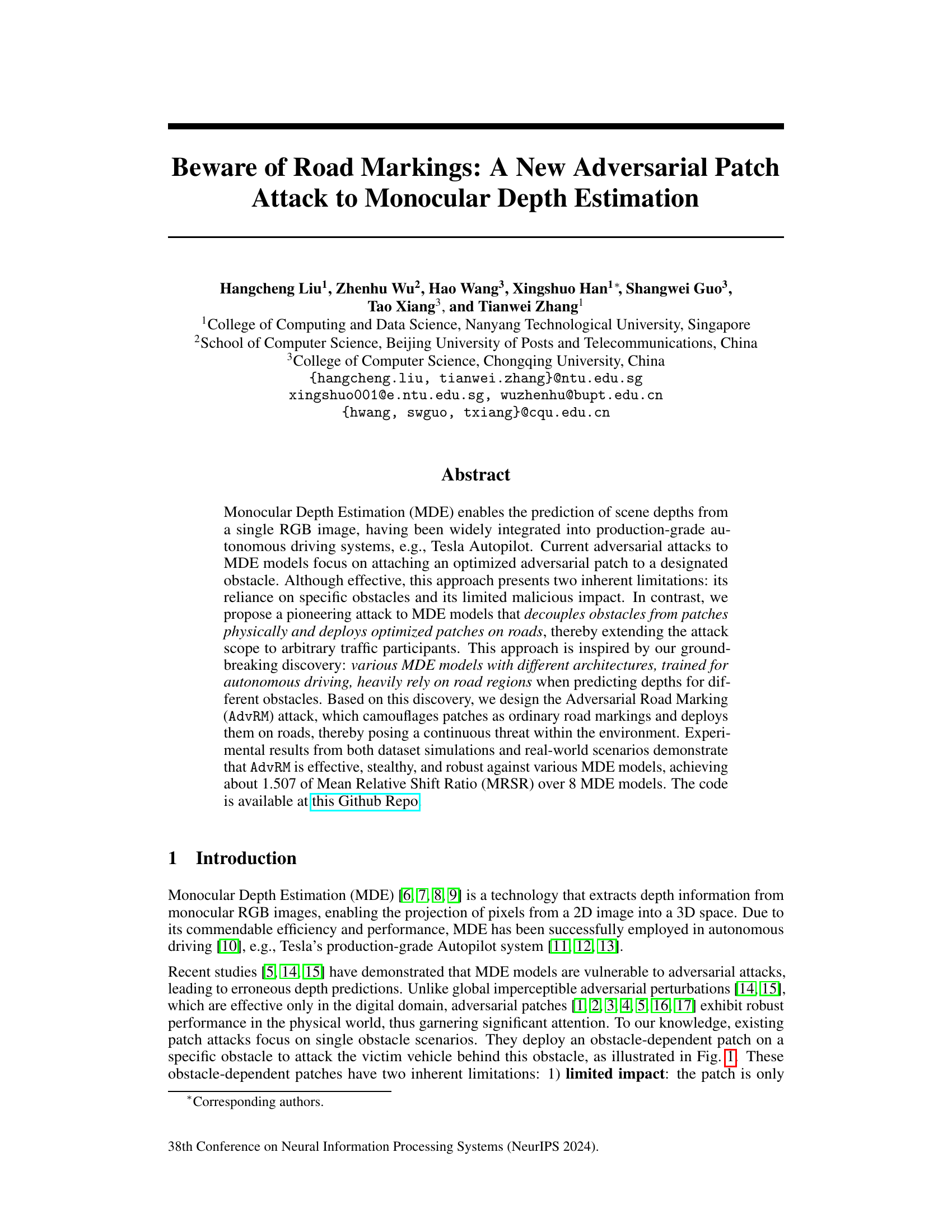

This figure illustrates the three main steps of the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack: patch insertion, obstacle insertion, and patch optimization. Step 1 shows how an adversarial patch (δ) is inserted into a background image (b) using parameters (θs). Step 2 shows how an obstacle (o) is inserted into the image using parameters (θo). Step 3 shows the iterative optimization process using a weighted sum of adversarial loss (La) and stealthiness loss (Lst) to refine the adversarial patch (δ). The green dashed lines indicate that multiple obstacles can be inserted in step 2.

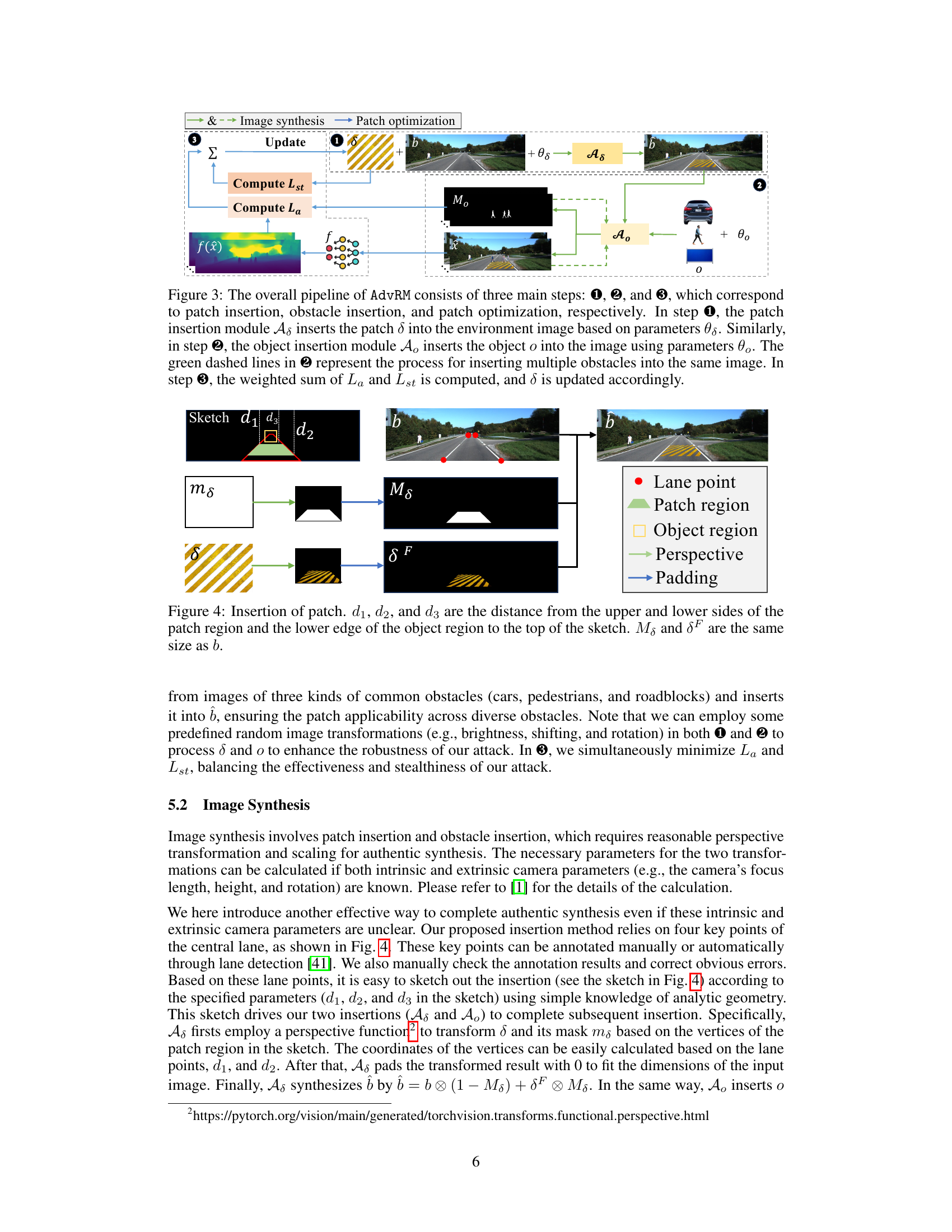

This figure illustrates the process of inserting an adversarial patch into a road scene image. It shows how the patch (δ) is integrated into the background image (b) using a perspective transformation based on lane points and distances (d1, d2, d3) calculated from the object’s position. The mask (mδ) guides the patch insertion. The resulting image (δF) shows the camouflaged patch seamlessly blended into the road markings. This process ensures the patch appears natural within the scene.

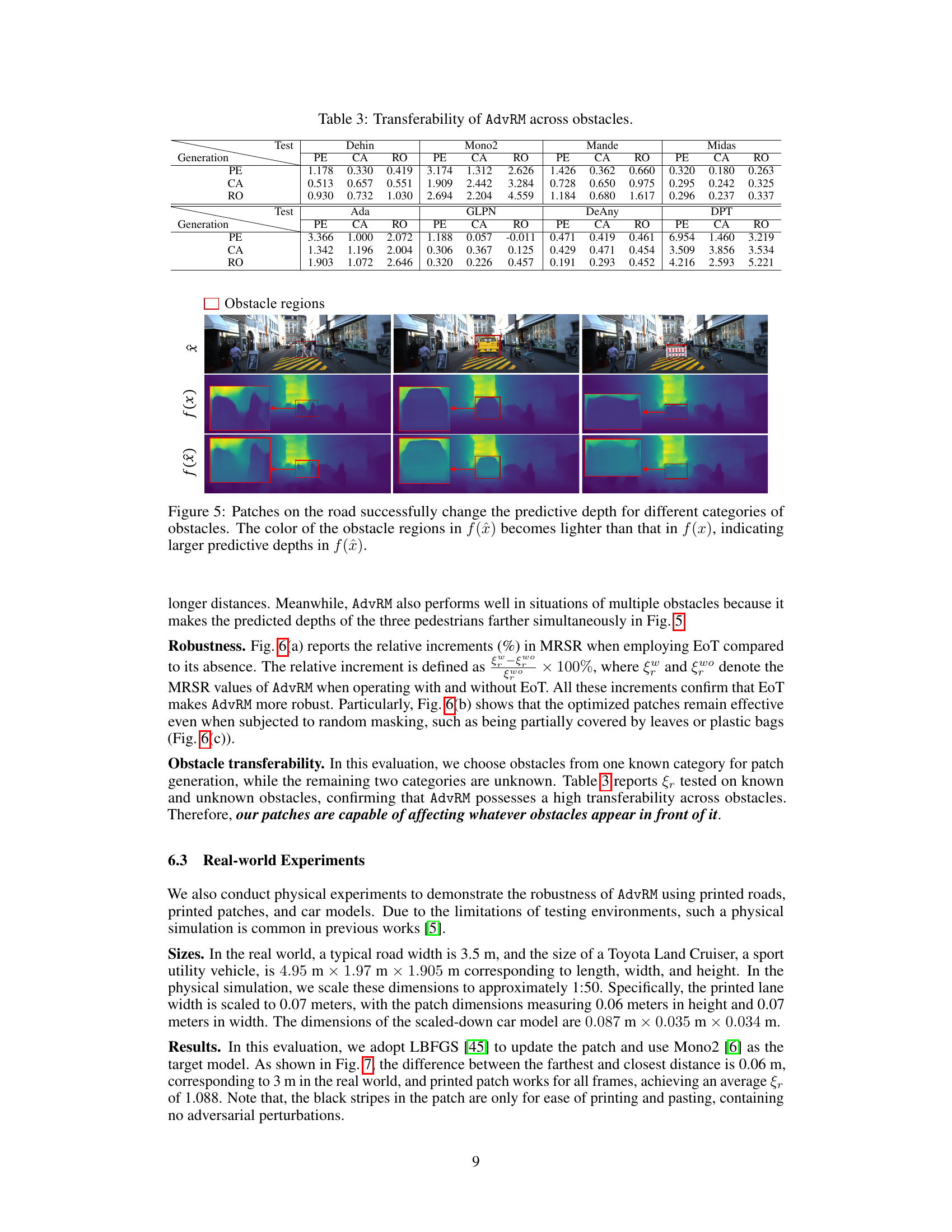

This figure shows the effectiveness of the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack in altering depth estimations of various obstacles. It presents three scenarios with different types of obstacles (pedestrian, car, and barrier) and demonstrates how deploying the adversarial patch on the road misleads the depth prediction model. The heatmaps illustrate the depth predictions, with warmer colors representing closer distances and cooler colors farther distances. The figure highlights how AdvRM consistently increases the estimated depth of the obstacles compared to the original depth map, regardless of obstacle type.

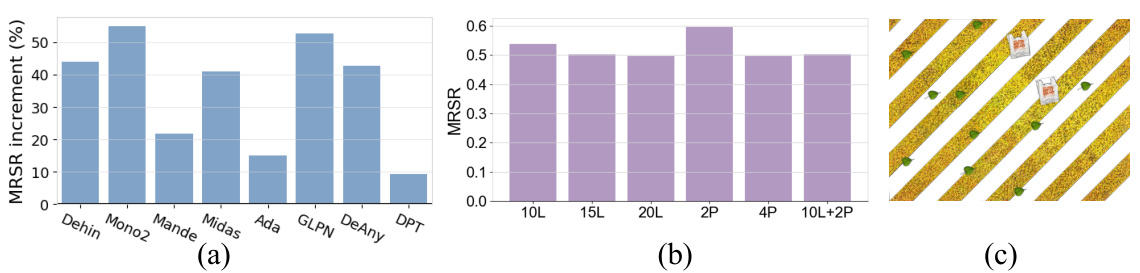

This figure shows the results of experiments evaluating the robustness of the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack against environmental factors such as leaves and plastic bags. The plots demonstrate the effect of Expectation of Transformation (EoT) on the attack’s Mean Relative Shift Ratio (MRSR) and how well the attack performs under partial occlusion by leaves and plastic bags. Specifically, (a) shows the percentage increase in MRSR when using EoT compared to not using it for various models; (b) displays average MRSR across different models when varying the number of leaves (10L, 15L, 20L) and plastic bags (2P, 4P, 10L+2P) covering the patch; and (c) provides a visual representation of the patch partially covered by leaves and plastic bags.

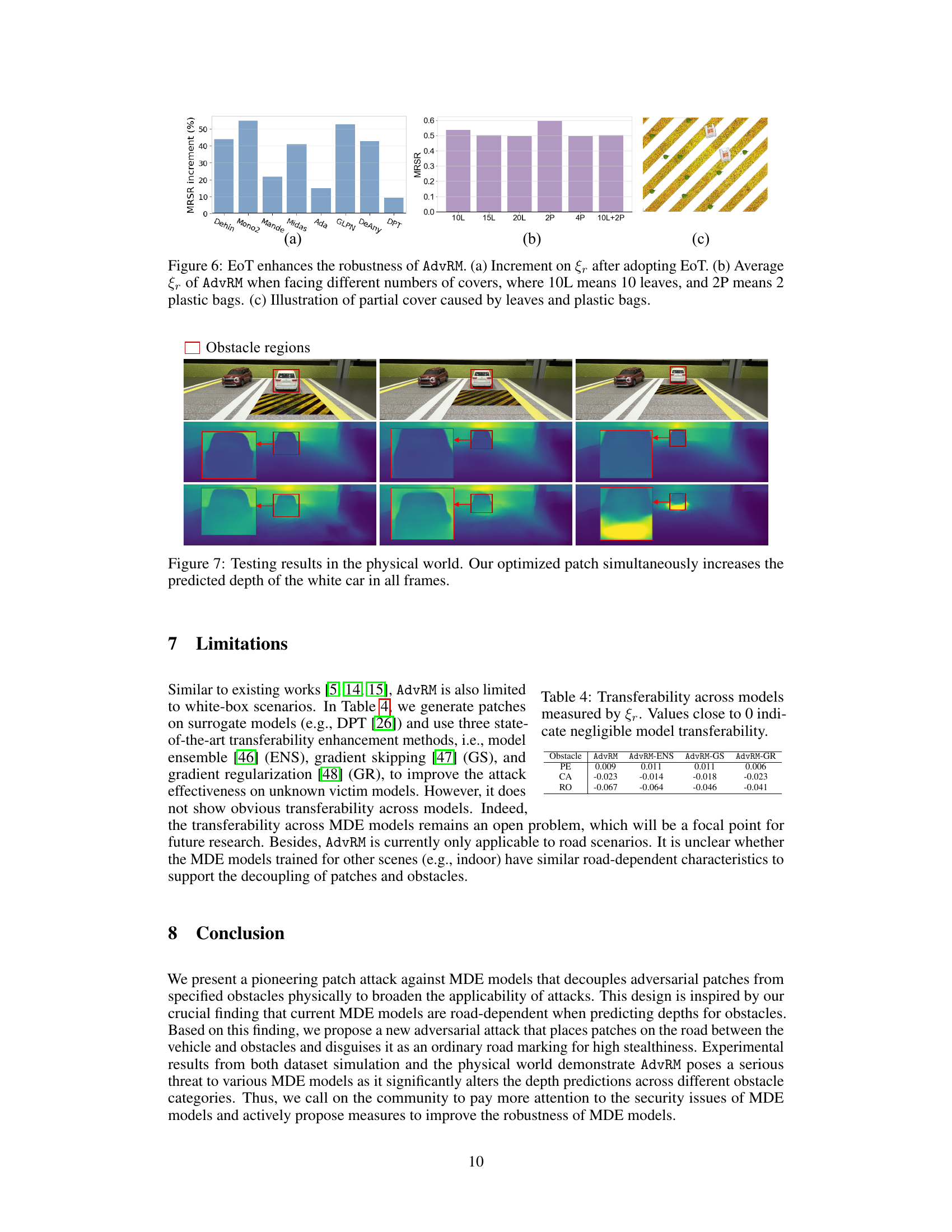

This figure presents the results of a real-world experiment to validate the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack. Three images in the top row show the physical setup: a model car approaching a patch on the road designed to fool depth estimation. The middle and bottom rows show the depth maps predicted by a Monocular Depth Estimation (MDE) model before and after the patch is introduced, respectively. The red boxes highlight the areas where the patch impacts depth perception. The results demonstrate that the AdvRM patch effectively and consistently increases the perceived depth of the obstacle (model car), making it appear significantly further away than it actually is.

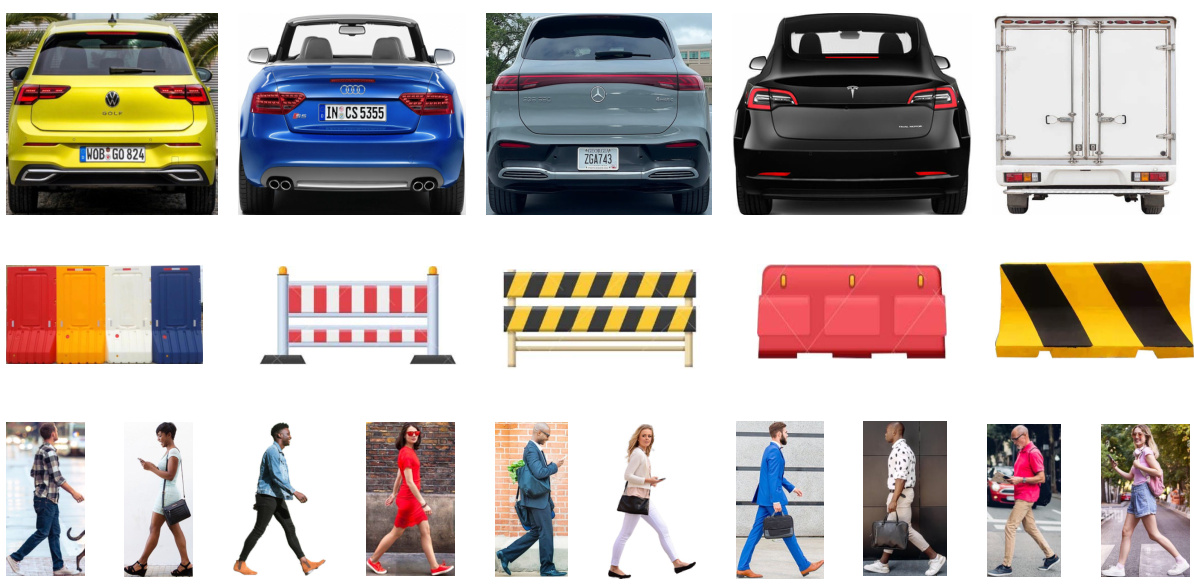

This figure shows a collection of images used as obstacles in the experiments. The images are categorized into three types: cars, roadblocks, and pedestrians. The car images show a variety of makes, models, and colors. The roadblock images show different types of barriers. The pedestrian images show individuals walking in various poses and attire.

This figure displays saliency maps for various monocular depth estimation (MDE) models. Saliency maps highlight the areas of an input image that most strongly influence the model’s depth prediction. For each model, a region of interest (blue box) is selected, and the corresponding saliency map (white points) shows which parts of the image are most influential in determining the depth of that region. Notably, in all cases, road regions near the region of interest strongly influence the model’s depth predictions, highlighting the road dependency of these MDE models.

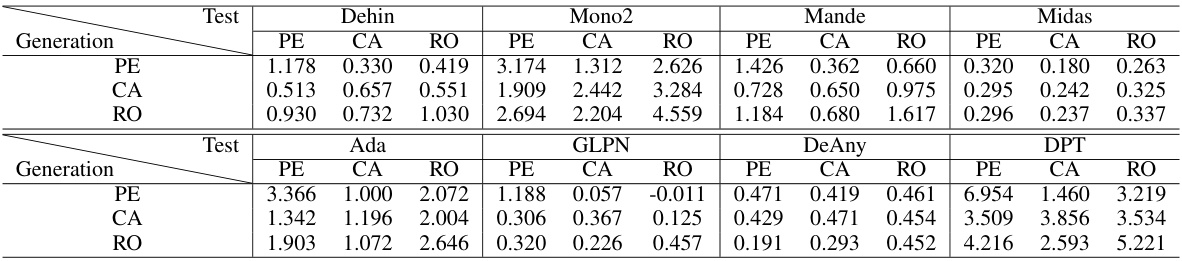

This figure displays four different examples of patch styles that could be used in the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack. These styles range from simple, common road markings (P1, P2, and P3) to a more complex and visually distinct pattern (P4, graffiti-style zebra crossing). The variety in styles is intended to increase the stealthiness and effectiveness of the attack by making it more difficult to detect the malicious patch.

More on tables

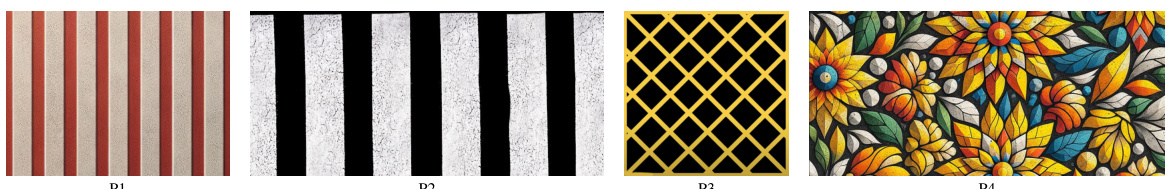

This table presents the results of the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack against eight different monocular depth estimation (MDE) models. The models are categorized into Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) based and Vision Transformer (ViT) based models. The table shows the Mean Relative Shift Ratio (MRSR) (ξr) and Affect Region Ratio (ARR) (ξα) for each model and for three different obstacle types (pedestrians, cars, and roadblocks). Higher values of ξr indicate more effective attacks, while higher values of ξα indicate a more global impact on depth prediction. The ‘Average’ row provides an overall performance summary for each metric across the different obstacle types.

This table presents the performance of the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack against eight different monocular depth estimation (MDE) models. The models are categorized into CNN-based and ViT-based architectures. The table shows the Mean Relative Shift Ratio (MRSR) and Affect Region Ratio (ARR) for each model under the AdvRM attack. These metrics quantify the effectiveness of the attack in altering depth predictions for various obstacle types (pedestrians, cars, roadblocks). Higher values for MRSR and ARR indicate more effective attacks.

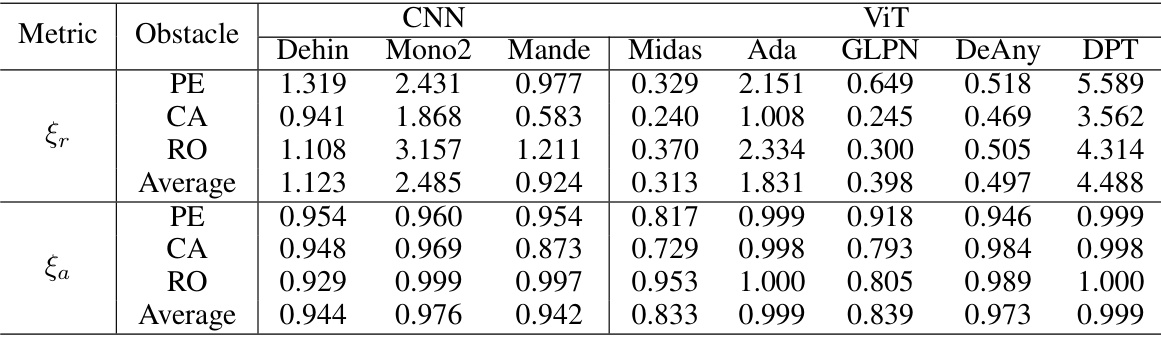

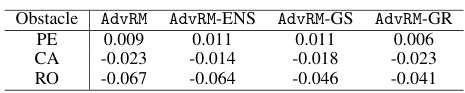

This table presents the results of the transferability experiment for the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack. It shows the Mean Relative Shift Ratio (MRSR) values achieved when the patches generated for one obstacle category (pedestrians, cars, or roadblocks) are tested on other obstacle categories. Positive MRSR values indicate successful depth manipulation, while negative values suggest failure. The results demonstrate that the attack generalizes well across different obstacle types.

This table compares the performance of the proposed adversarial attack method, AdvRM, against a previous state-of-the-art method ([1]) in scenarios with single and multiple obstacles. The metrics used for comparison are Mean Relative Shift Ratio (MRSR) and Affect Region Ratio (ARR). MRSR measures the average change in the predicted depth of obstacles after the attack, while ARR indicates the proportion of obstacle pixels affected by the attack. Higher values for both metrics indicate a more effective attack. The results demonstrate that AdvRM is superior to the previous method, achieving significantly higher MRSR and ARR values in both single and multiple obstacle scenarios.

This table compares the effectiveness of adversarial patches placed in three different locations relative to an obstacle: above the obstacle (Top), to the right of the obstacle (Right), and on the road surface (Road). The MRSR (Mean Relative Shift Ratio) values indicate the average relative change in depth prediction for each obstacle type (Pedestrians - PE, Cars - CA, and Roadblocks - RO) caused by the patch. Higher MRSR values mean that the attack was more effective at altering the depth prediction. The results show that the road-placed patches are far more effective across all obstacle types, supporting the paper’s claim that MDE models heavily rely on road regions for depth estimation.

This table presents the results of the Adversarial Road Marking (AdvRM) attack against eight different monocular depth estimation (MDE) models. It shows the effectiveness of the attack across various models with different architectures (CNN and ViT-based), and using three metrics: Percentage of Enhancement (PE), Correctly Affected Area (CA), and Relative Shift Ratio (RO). Higher values generally indicate a more successful attack.

Full paper#