↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Evaluating the quality of sparse autoencoders (SAEs) for language model interpretability is challenging due to the lack of ground truth for interpretable features. Existing methods rely on proxies like sparsity and reconstruction fidelity, which may not fully capture the essence of disentanglement. This paper tackles this issue by focusing on language models trained on board games (chess and Othello), which offer naturally occurring interpretable features.

The paper introduces two new metrics: board reconstruction (measuring how well the SAE can reconstruct the board state from its features) and coverage (assessing how many of the pre-defined interpretable features are captured by the SAE). Furthermore, a new training technique, called p-annealing, is presented to improve SAE performance. This method gradually reduces the sparsity penalty during training, leading to improved feature disentanglement. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of both the new metrics and p-annealing, significantly improving upon existing unsupervised approaches.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces novel methods for evaluating the quality of sparse autoencoders (SAEs) used in language model interpretability. It also proposes p-annealing, a new SAE training technique, offering improvements over existing methods. This work is relevant to researchers focusing on mechanistic interpretability and advancements in disentangled representation learning.

Visual Insights#

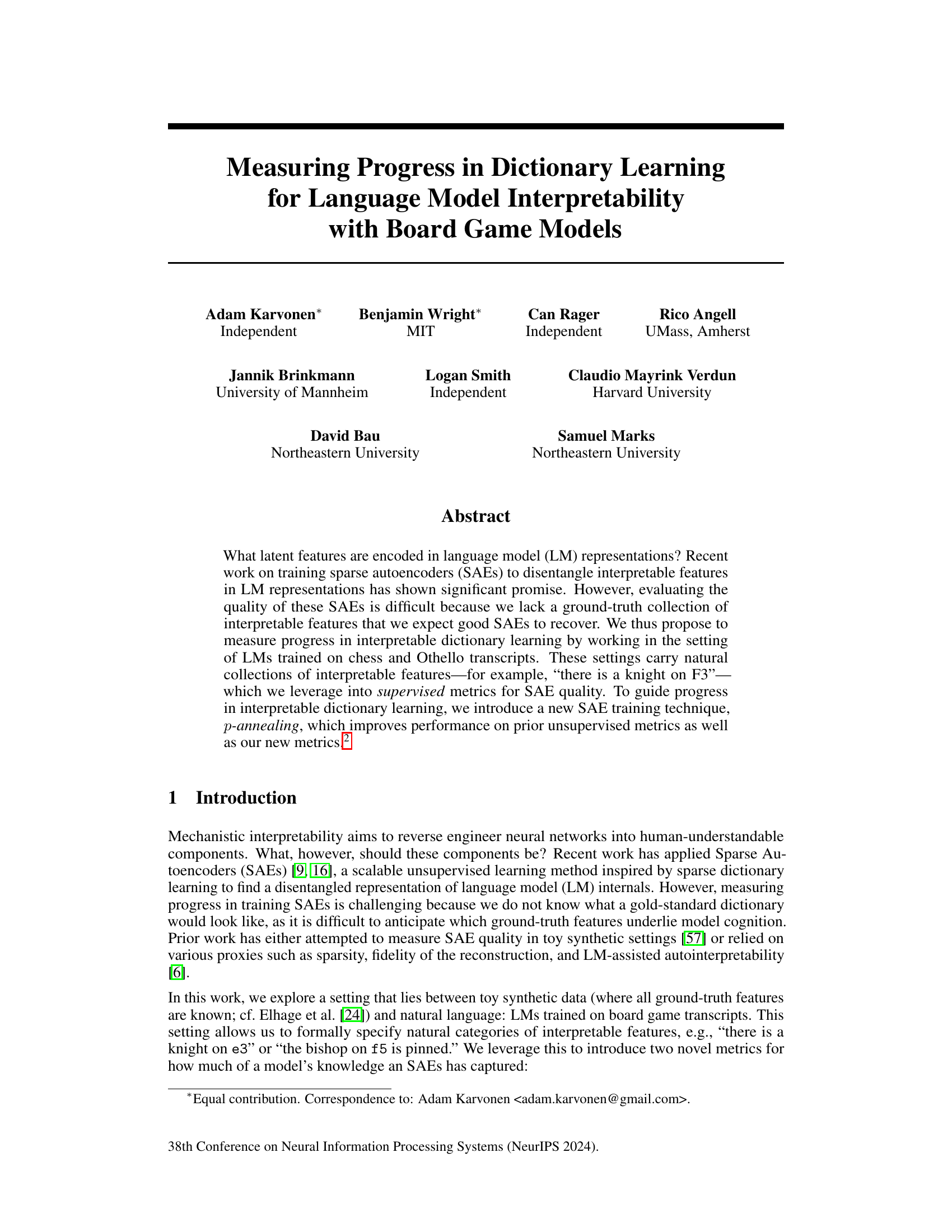

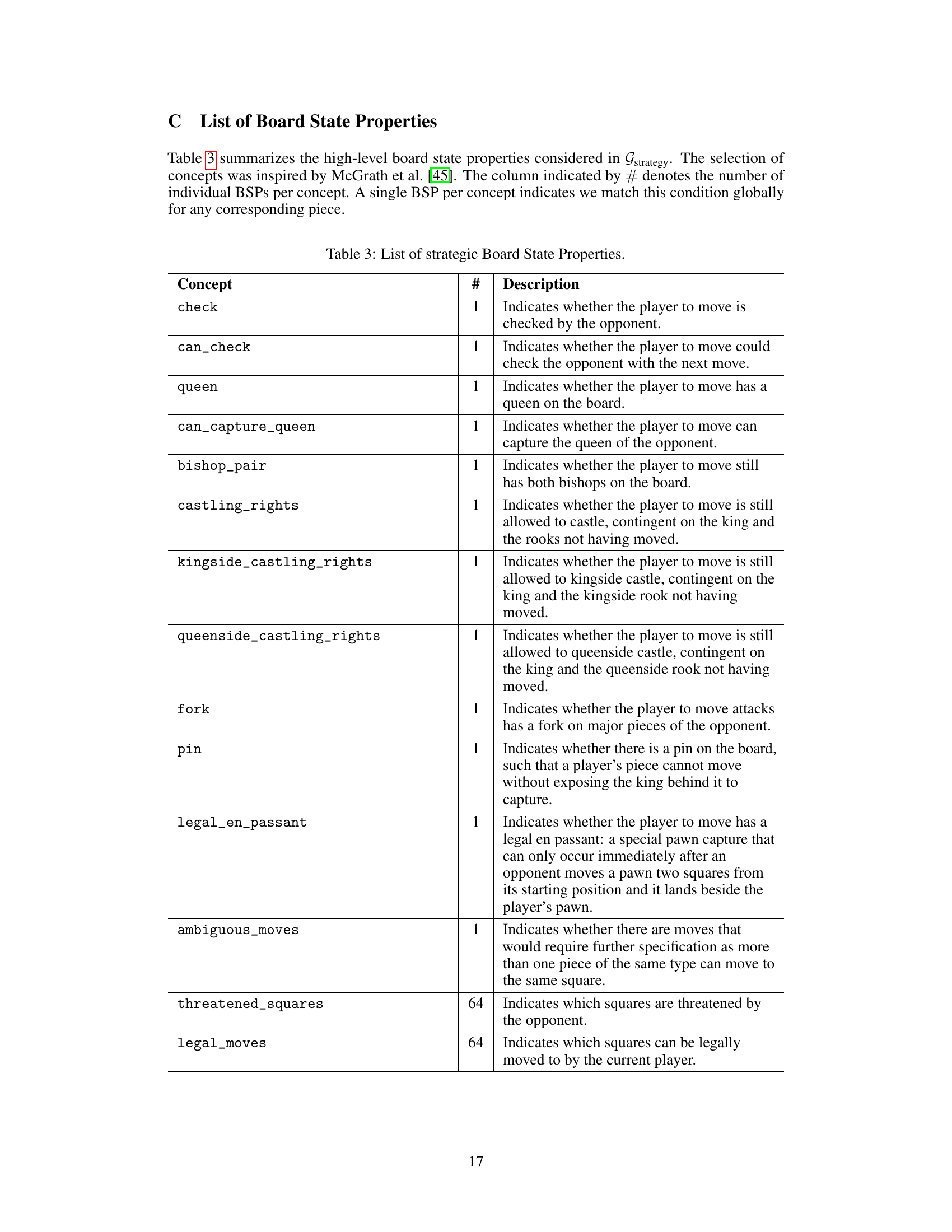

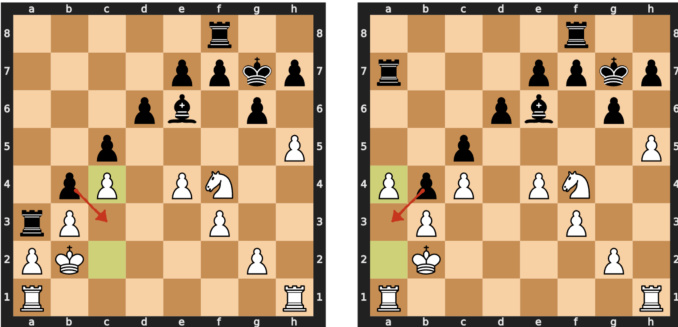

This figure shows three examples of chessboard states, each illustrating a different board state property (BSP) detected by a sparse autoencoder (SAE) feature. The left panel shows a BSP detector identifying a knight on F3. The middle panel shows a rook threat detector recognizing an immediate threat to a queen. The right panel shows a pin detector identifying a move that resolves a check by creating a pin. These examples highlight the SAE’s ability to learn interpretable features related to chess strategy.

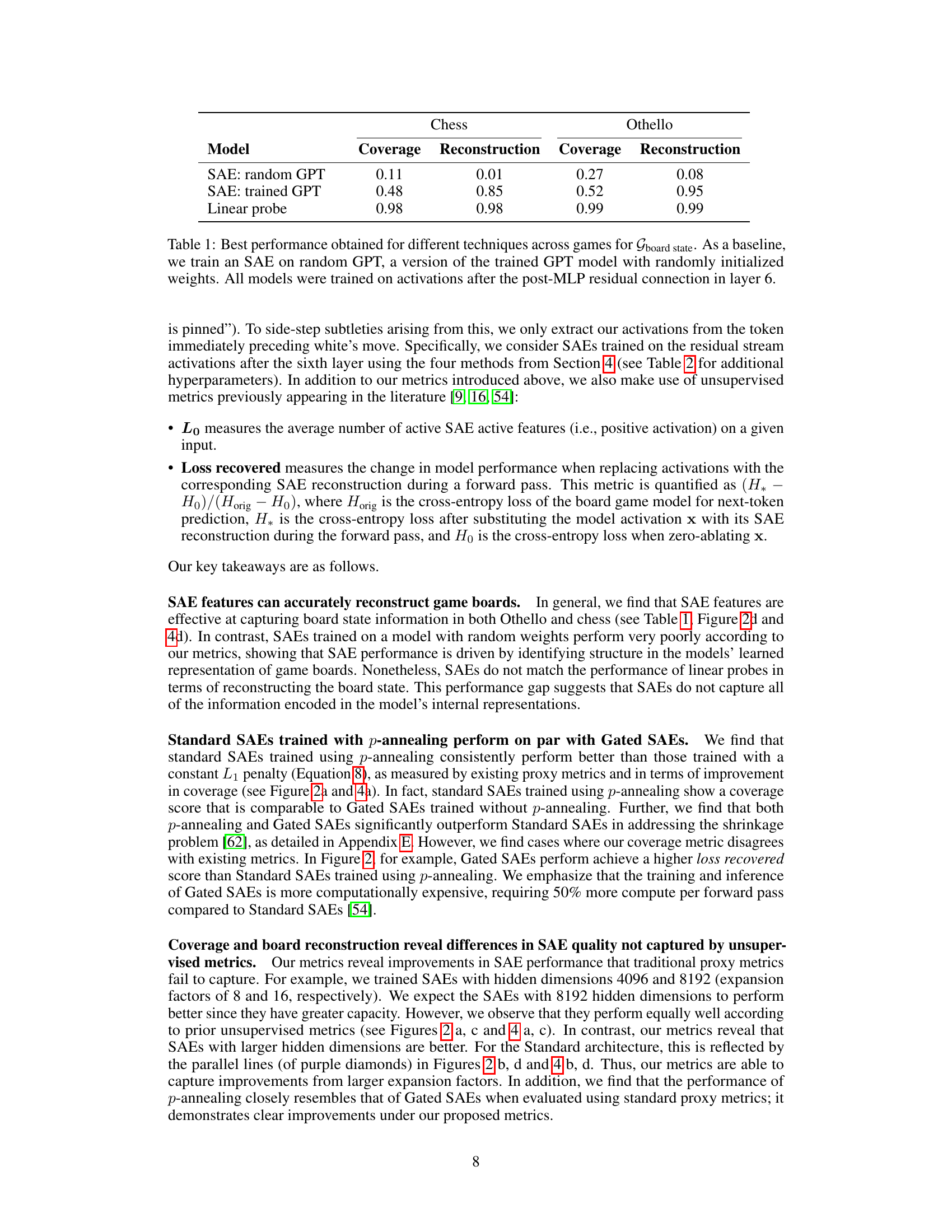

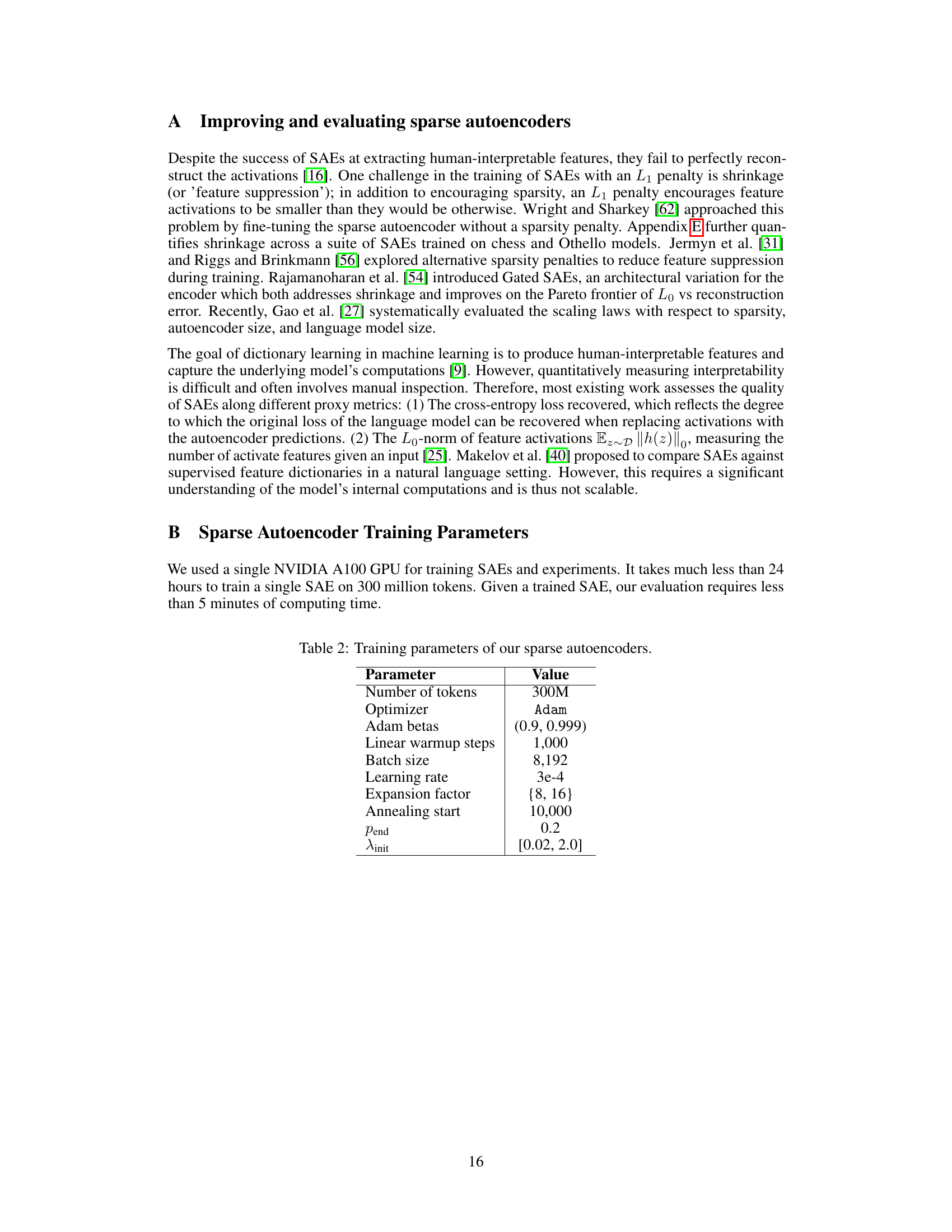

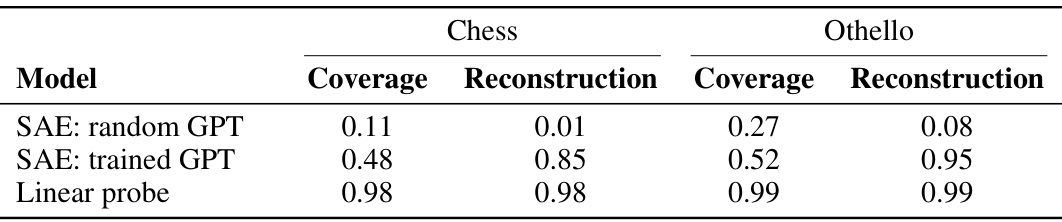

This table presents the best performance achieved by different methods (SAE with random GPT, SAE with trained GPT, and linear probe) in reconstructing board states using Gboard properties for both chess and Othello games. The SAE models used activations from after the post-MLP residual connection in layer 6. The random GPT SAE serves as a baseline, demonstrating the importance of training on actual game data.

In-depth insights#

Interpretable SAEs#

Sparse autoencoders (SAEs) are a promising approach to enhance the interpretability of complex language models (LMs). By training SAEs to disentangle interpretable features within LM representations, researchers aim to gain a better understanding of how these models function. A key challenge is the lack of a ground truth for evaluating the quality of these interpretable SAEs. The paper introduces a novel approach to tackle this challenge. Instead of relying on generic metrics, it uses LMs trained on board game data (chess and Othello) where interpretable features are naturally present. This allows them to define and evaluate more intuitive metrics. The use of board games provides a controlled setting with easily definable interpretable features. Another key contribution is the introduction of a new SAE training technique called p-annealing, which improves the performance of SAEs on both new and established metrics. Overall, the work bridges a critical gap in the evaluation of interpretable SAEs by providing concrete methods and demonstrating their effectiveness in uncovering interpretable features in LMs.

Board Game Tests#

The use of board games like chess and Othello as testbeds for language model interpretability offers a novel approach with several advantages. The structured nature of these games provides a readily available ground truth for evaluating the quality of sparse autoencoders (SAEs) used to disentangle interpretable features. Unlike natural language, where ground truth is hard to define, board game transcripts provide clear, verifiable features (e.g., ‘knight on F3’). This allows for the creation of supervised metrics, improving assessment over previous unsupervised methods that relied on proxies. The clear interpretable features also enable a new evaluation metric, board reconstruction, supplementing existing coverage metrics and providing a more complete picture of SAE performance. However, it is important to consider the limitations. The metrics’ sensitivity to researcher preconceptions remains a significant caveat, potentially limiting generalizability to other domains. Despite this, the board game approach represents a valuable step towards a more robust and objective evaluation framework for language model interpretability.

p-Annealing Method#

The proposed p-annealing method offers a novel approach to training sparse autoencoders (SAEs) by dynamically adjusting the L_p norm penalty during training. Starting with a convex L1 penalty (p=1) ensures initial training stability, the approach gradually decreases p towards a non-convex L0 penalty (p→0). This gradual transition helps avoid getting stuck in poor local optima, which is a common issue with directly employing the non-convex L0 penalty for sparsity. The method’s effectiveness is demonstrated through improved performance on existing unsupervised metrics, such as loss recovered and L0, and the newly introduced supervised metrics for board reconstruction and coverage. The combination of convex and non-convex optimization during training suggests a potential advantage in finding sparser and potentially more interpretable representations than existing methods. Furthermore, p-annealing’s compatibility with other SAE architectures, like Gated SAEs, suggests its flexibility and potential for broader impact within mechanistic interpretability research. The adaptive coefficient adjustment further enhances its practical applicability and robustness.

Novel Metrics#

The paper introduces novel metrics to evaluate the quality of Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) in the context of language model interpretability. Instead of relying on proxy metrics like reconstruction error or sparsity, which don’t directly capture the human-understandable aspects of the learned features, the proposed metrics assess the ability of SAEs to recover interpretable features related to the game board state. This is achieved by training LMs on chess and Othello game transcripts. The board state provides a rich ground truth for evaluating the learned features. Specifically, the metrics measure coverage, quantifying how many of the predefined interpretable features are captured by the SAE, and board reconstruction, assessing how well the state of the game board can be reconstructed using only the SAE’s learned features. The use of game transcripts as training data is a clever way to leverage readily available ground truth information for evaluating the SAEs. These metrics directly address the core goal of mechanistic interpretability: creating human-understandable components from complex neural networks. While they are specific to board games, this approach could inspire similar methods for other domains where a well-defined ground truth is accessible.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending these novel metrics beyond board games to other domains with naturally interpretable features, potentially using simulations or carefully constructed synthetic datasets. This would involve identifying suitable tasks where ground truth features are known or readily inferable and adapting the metrics to capture these features effectively. Investigating the impact of different autoencoder architectures and training techniques on the performance of the proposed metrics in diverse contexts is also crucial for establishing their robustness and generalizability. A deeper investigation into the relationship between these new metrics and existing, less interpretable metrics would yield valuable insights into the nature of disentanglement in SAE’s and LM’s. Finally, exploring the utility of these metrics in guiding the development of new SAE training methods that explicitly promote disentanglement of interpretable features is a promising area for future work. This could include exploring alternative loss functions or regularization strategies specifically designed to maximize the coverage and reconstruction scores.

More visual insights#

More on figures

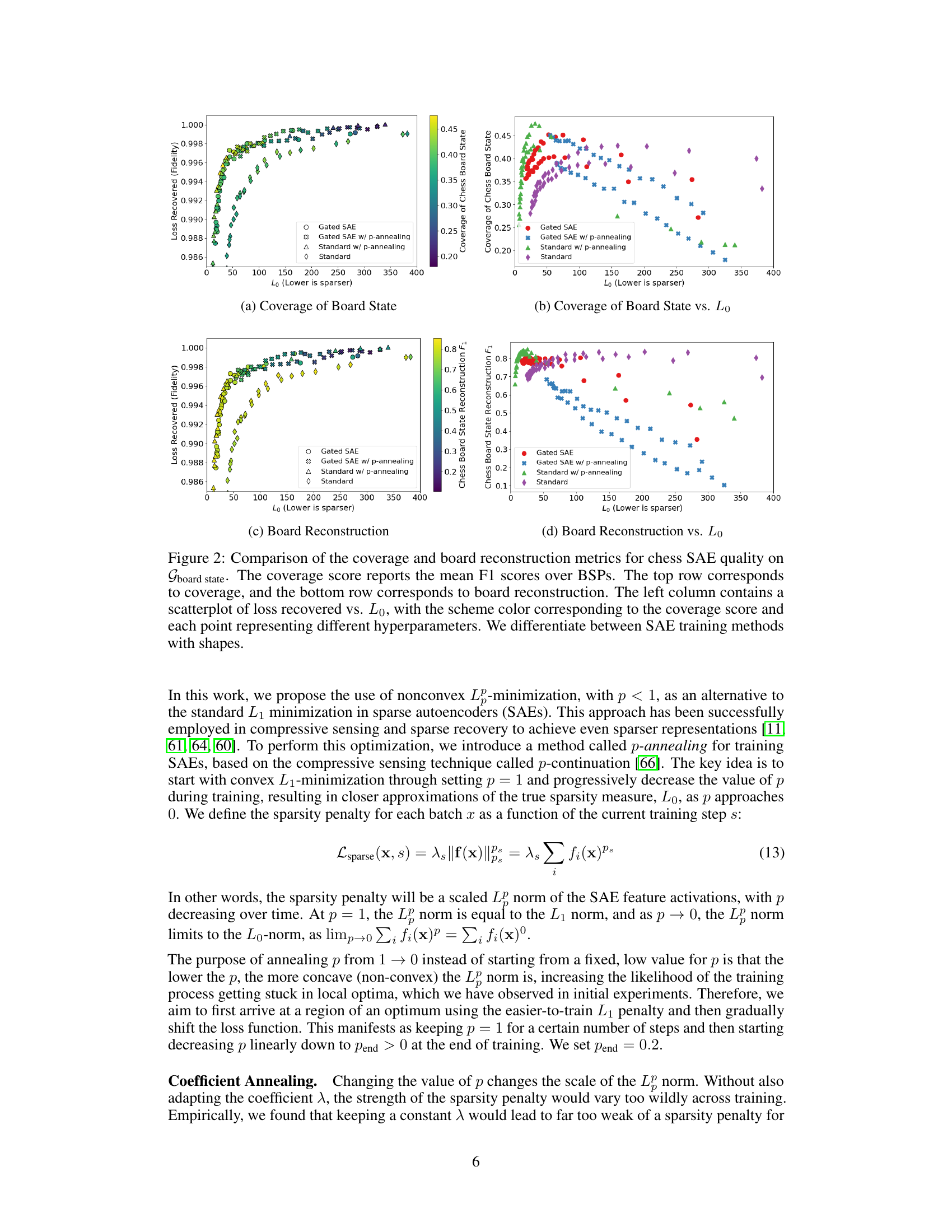

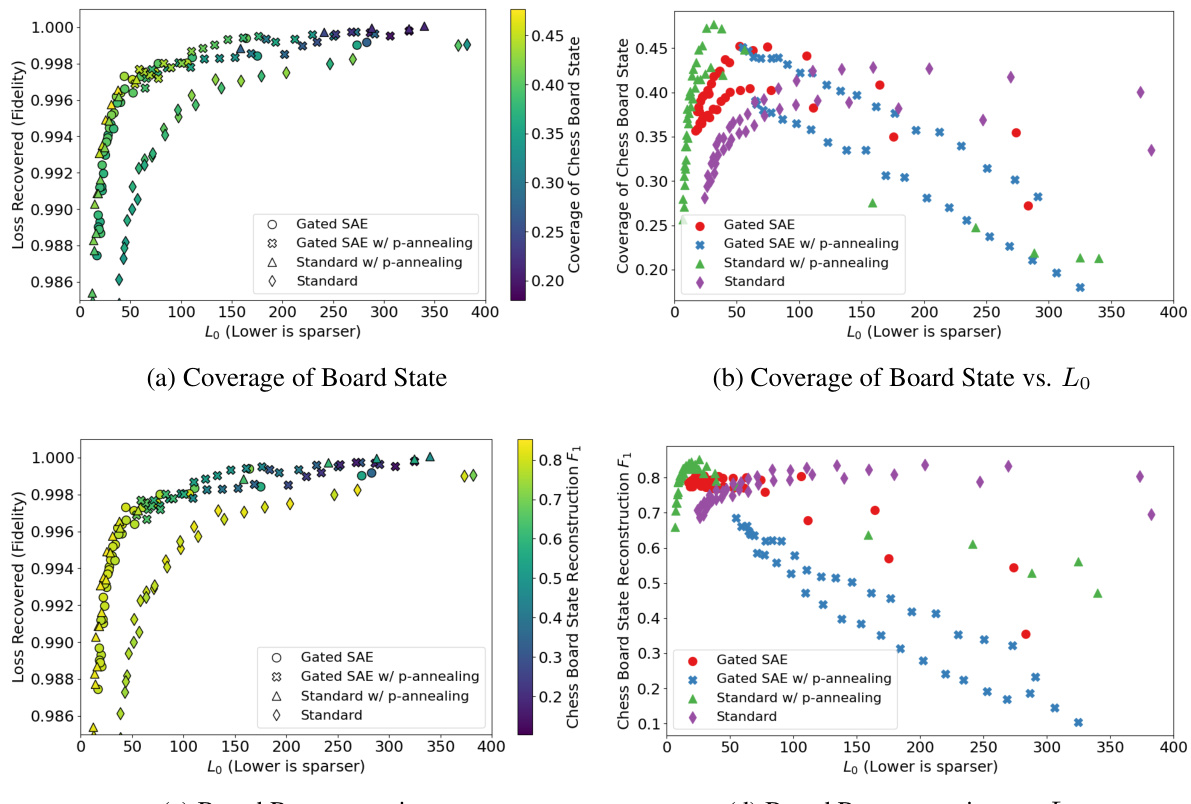

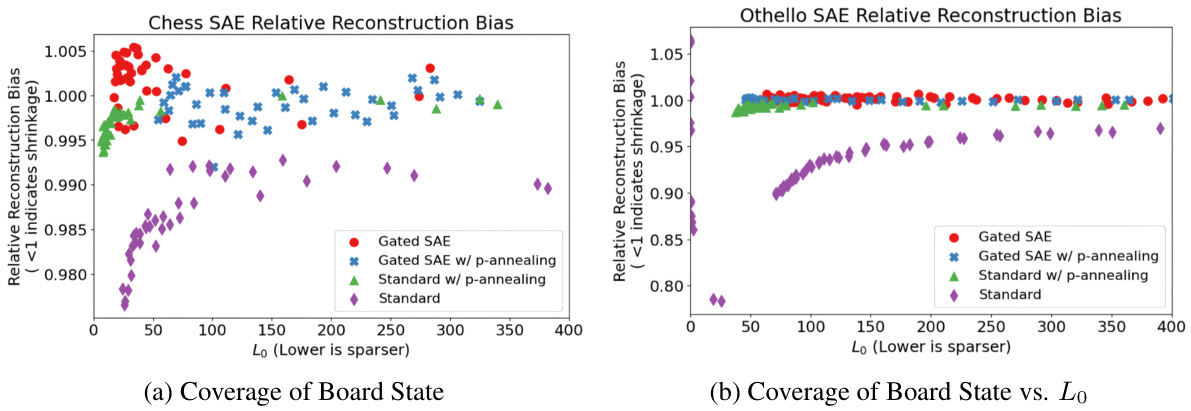

This figure compares the performance of four different SAE training methods (Standard, Standard w/ p-annealing, Gated SAE, Gated SAE w/ p-annealing) on two metrics: coverage and board reconstruction. The x-axis represents the L0 norm (sparsity), while the y-axis shows the performance on each metric. The plots show how the coverage and reconstruction performance change with increasing sparsity for each training method. Different shapes represent different hyperparameter settings for each method. The figure helps to understand the tradeoff between sparsity and performance for various SAE training strategies on the Gboard state properties.

This figure compares different methods for training sparse autoencoders (SAEs) on chess game data, evaluating their performance using two new metrics: coverage and board reconstruction. The graphs show how these metrics (as well as existing metrics like loss recovered and L0 norm) relate to the sparsity of the SAE features (lower L0 means more sparse). Different shapes represent different training methods, allowing for a comparison of their effectiveness across multiple measures of performance.

This figure compares the performance of different SAE training methods on chess data using two metrics: coverage and board reconstruction. The plots show how these metrics change with the L0 norm (sparsity) of the SAE features. The color-coding helps to understand how the two metrics relate to one another, and the different shapes indicate the different SAE training methods. It demonstrates that p-annealing generally improves performance compared to standard SAE training.

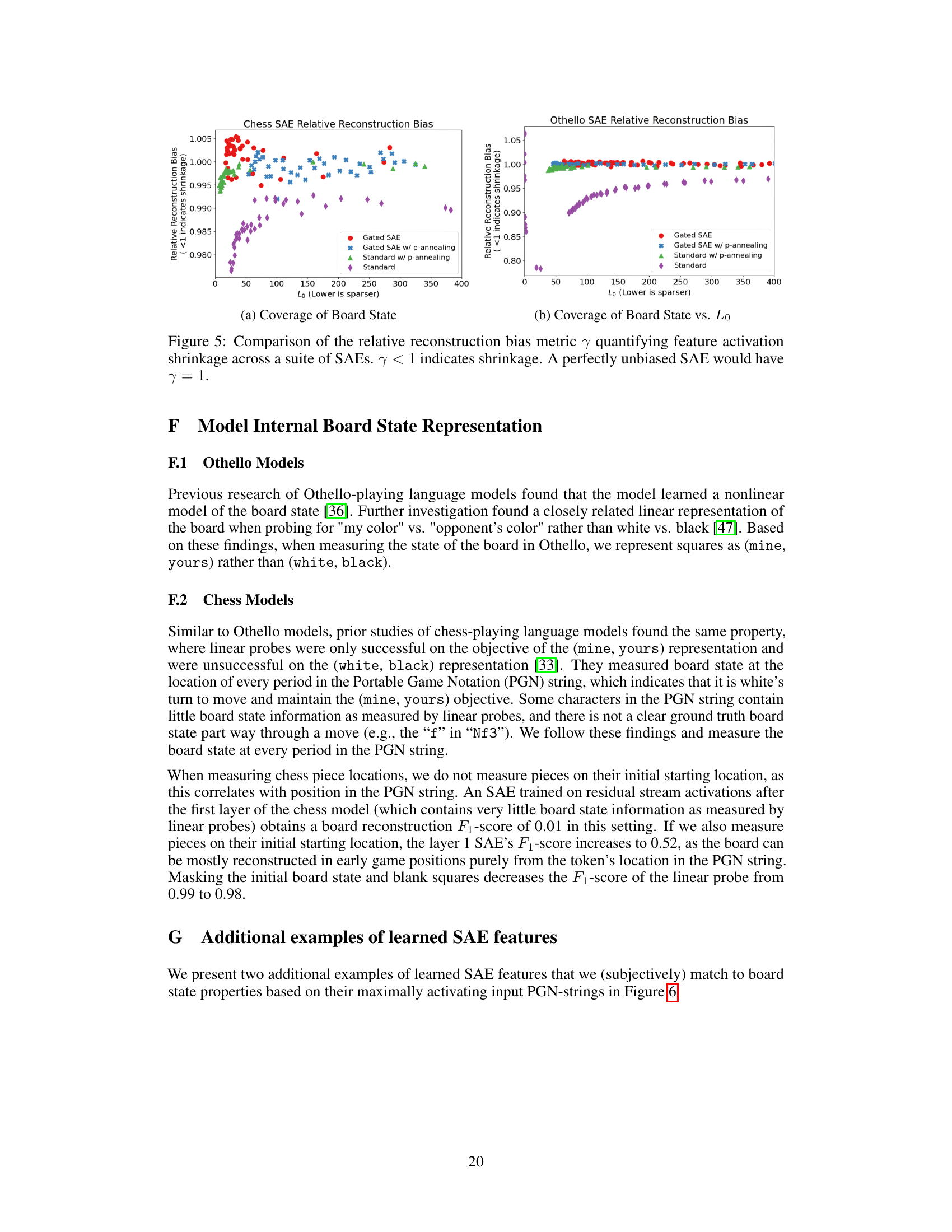

This figure compares the relative reconstruction bias (γ) for different SAE training methods across various levels of sparsity (L₀). The relative reconstruction bias measures how much the SAE underestimates (shrinkage) or overestimates the feature activations. The lower the γ value, the more shrinkage is observed. The figure shows that p-annealing and Gated SAEs achieve similar levels of improved relative reconstruction bias compared to the Standard SAE, particularly in the case of Othello, while chess shows less difference.

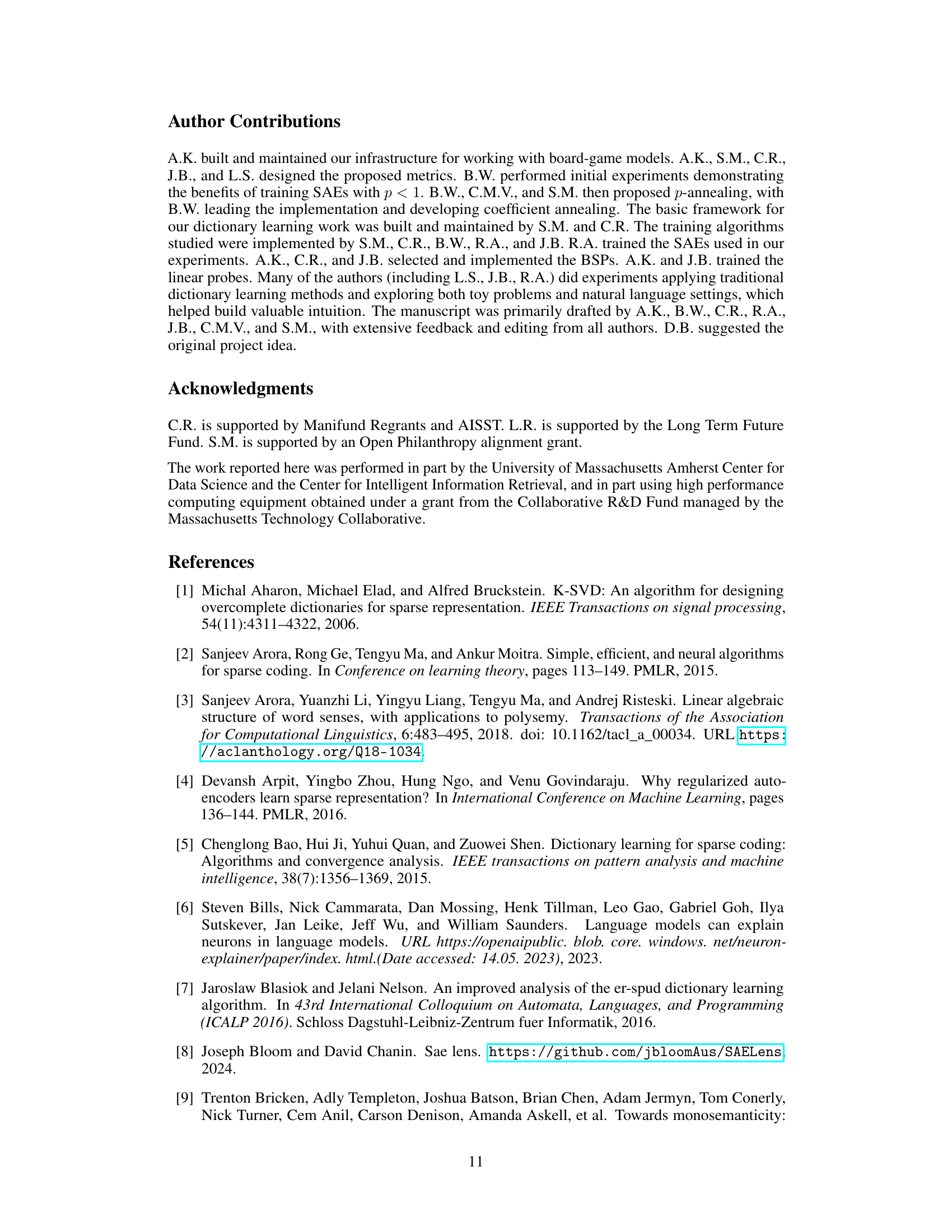

This figure shows three examples of chess board states and their corresponding PGN strings, highlighting tokens that trigger specific SAE features. The intensity of the blue color indicates the strength of the feature activation, demonstrating how these features correspond to specific board configurations or game states.

This figure shows three examples of chess board states where specific SAE features have high activation. Each example illustrates a different interpretable board property (BSP), such as the availability of an en passant move, the presence of a knight on a particular square, and a mirrored knight position. The PGN sequences leading to each state are also displayed, highlighting the relevant moves.

This figure shows three examples of chessboard states, each highlighting a different interpretable board state property (BSP) detected by a sparse autoencoder (SAE). The left panel shows a BSP detector identifying a knight on square f3. The middle panel shows a BSP detector indicating a rook’s threat to a queen. The right panel shows a BSP detector identifying a pin that resolves a check.

More on tables

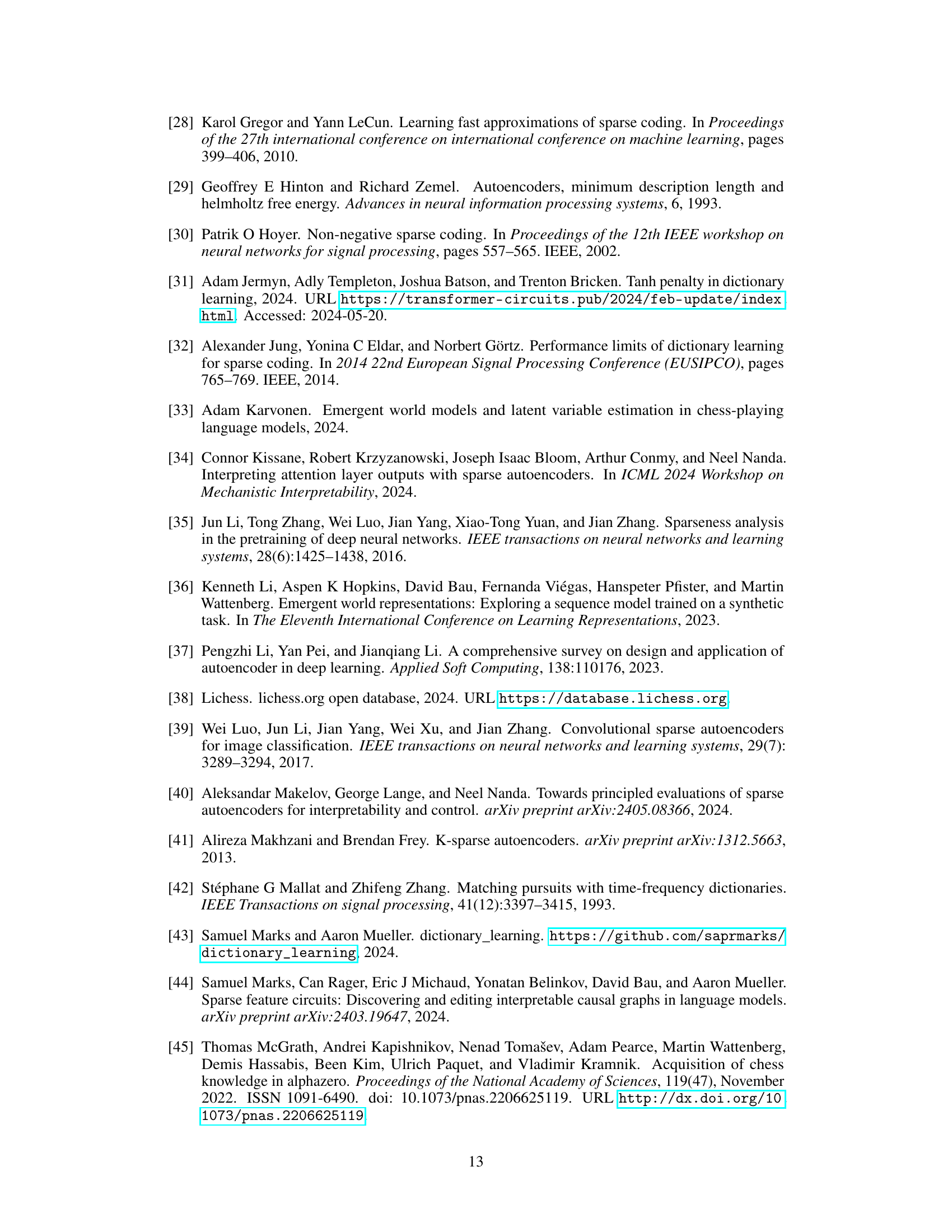

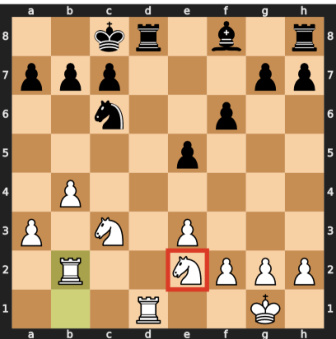

This table lists the hyperparameters used during the training of sparse autoencoders (SAEs). The parameters include the number of tokens processed, the optimizer used (Adam), the Adam beta values, the number of linear warmup steps, the batch size, the learning rate, the expansion factor (which determines the size of the hidden layer relative to the input layer), the annealing start point (the training step at which the p-annealing process begins), the final value of p (Pend) in the p-annealing process, and the initial value of lambda (λinit) used for the sparsity penalty.

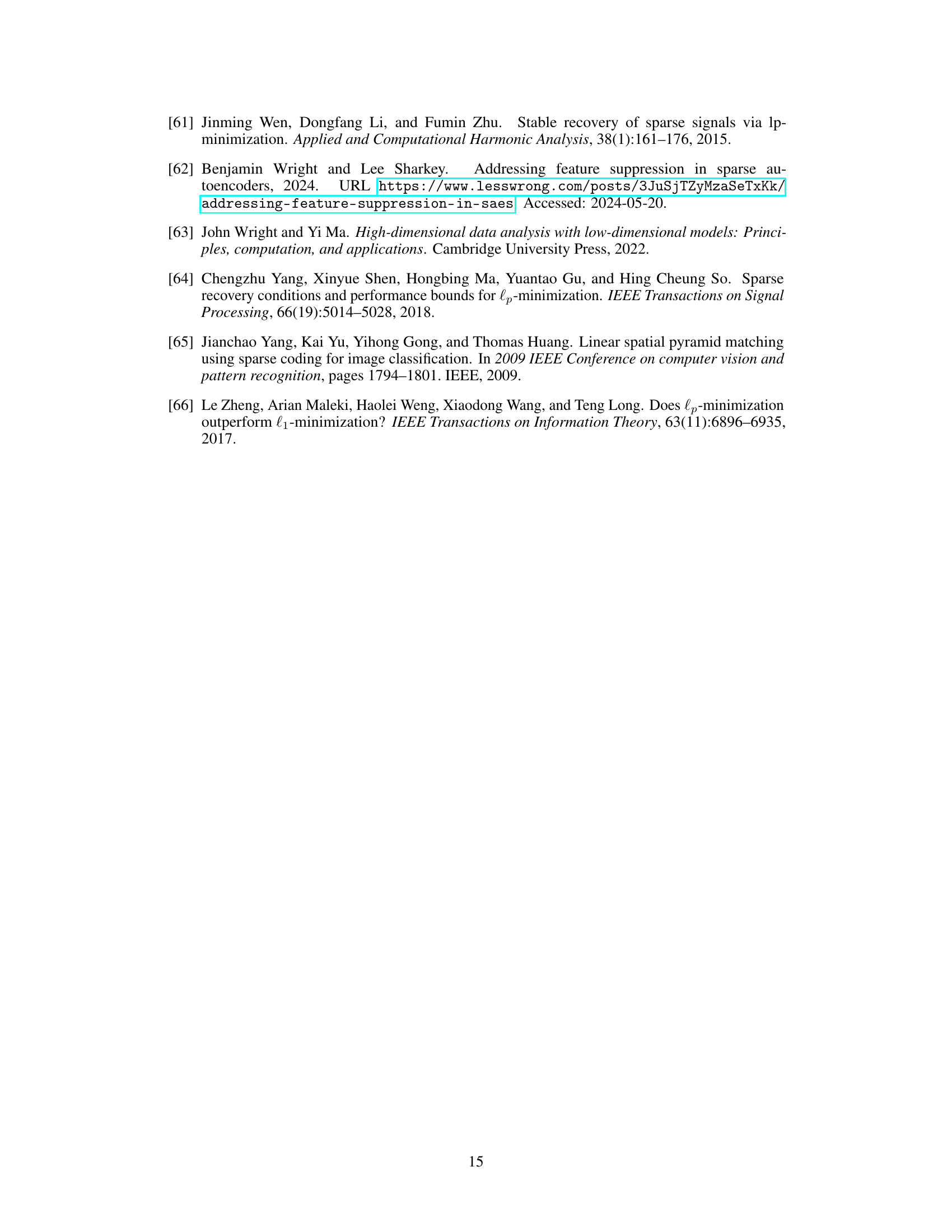

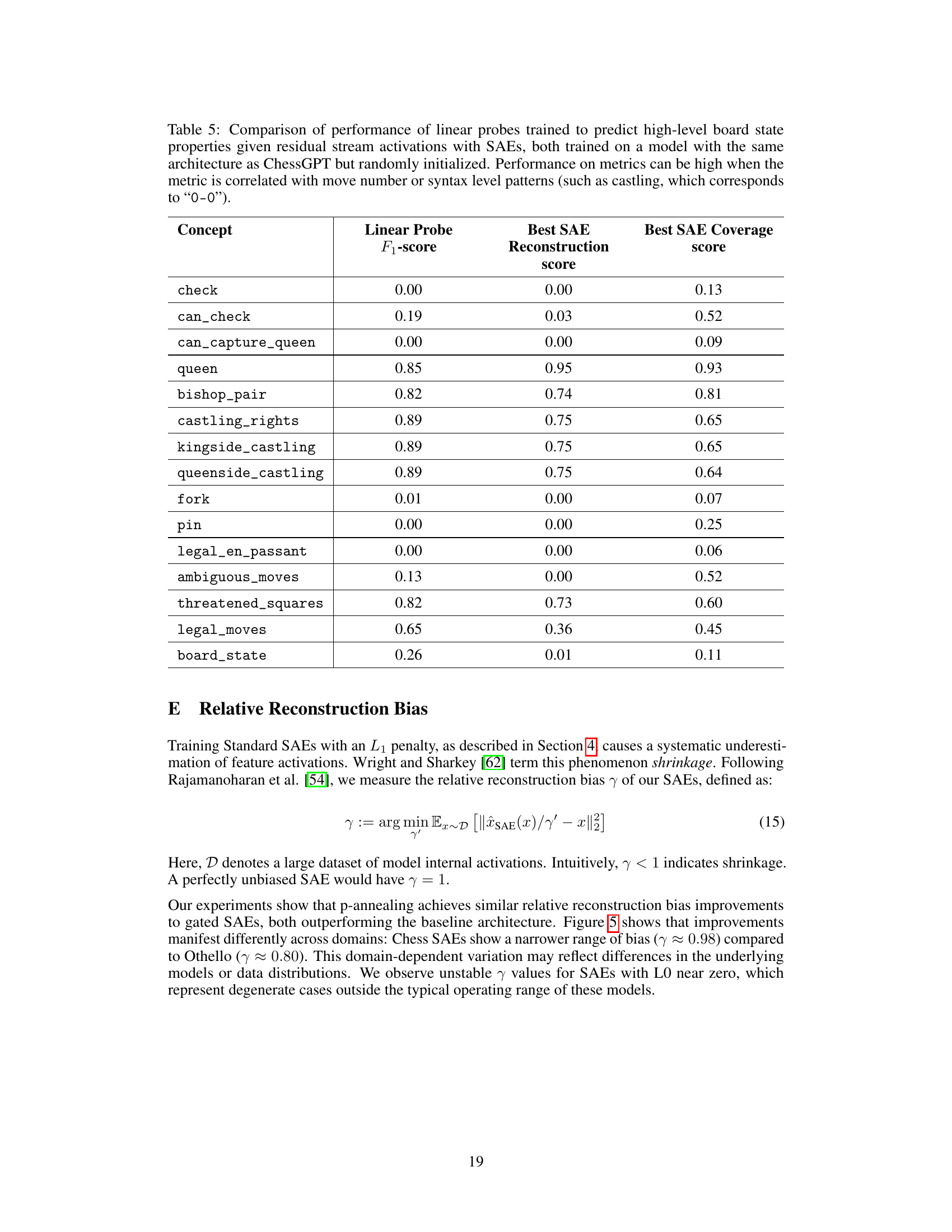

This table compares the performance of linear probes and sparse autoencoders (SAEs) in predicting various board state properties in chess. It shows the F1-score for linear probes, the reconstruction score for SAEs, and the best SAE coverage score for each property. The properties range from simple ones (like checking the king) to more complex ones (like detecting forks or pins). The table highlights the relative strengths and weaknesses of linear probes and SAEs in capturing different aspects of the game state.

This table compares the performance of linear probes and Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) in predicting various board state properties in chess. Linear probes are simpler models that directly predict properties from the neural network activations. SAEs, on the other hand, create a lower-dimensional representation of the activations and then use that representation to predict the board state properties. The table shows the F1-score for linear probes, the reconstruction score for SAEs (how well the SAE can reconstruct the original board state), and the coverage score for SAEs (how many board state properties the SAE is able to capture). The results show that while linear probes perform better overall, SAEs are capable of capturing and reconstructing several key properties.

This table compares the performance of linear probes and sparse autoencoders (SAEs) in predicting various board state properties. The linear probes use the residual stream activations from ChessGPT after the 6th layer as input. The SAEs are evaluated based on two new metrics introduced in the paper: coverage and board reconstruction. The table shows the F1-score for each linear probe and the reconstruction score and coverage score for the best-performing SAE for each property.

Full paper#