↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many learning rate tuners aim for immediate loss reduction but struggle in the long run. This paper investigates why, focusing on the interplay between learning rates and the ‘sharpness’ of the loss landscape (related to curvature). It finds that these tuners often destabilize the training process, leading to worse results than a simple constant learning rate.

The researchers introduce a new method, called Curvature Dynamics Aware Tuning (CDAT), which changes the learning rate to maintain a balance in the sharpness dynamics. CDAT significantly improves long-term performance, demonstrating behavior similar to carefully designed warm-up schedules. The findings highlight the importance of considering the joint dynamics of learning rates and curvature for better adaptive learning rate tuners. The effects of stochasticity are also discussed, explaining why some methods are better at specific batch sizes.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the conventional wisdom in adaptive learning rate tuning by revealing the limitations of existing greedy approaches and proposing a novel method that prioritizes long-term stability. This work is relevant to ongoing research on optimization in deep learning and offers a new perspective on designing effective adaptive learning rate tuners, potentially impacting various applications.

Visual Insights#

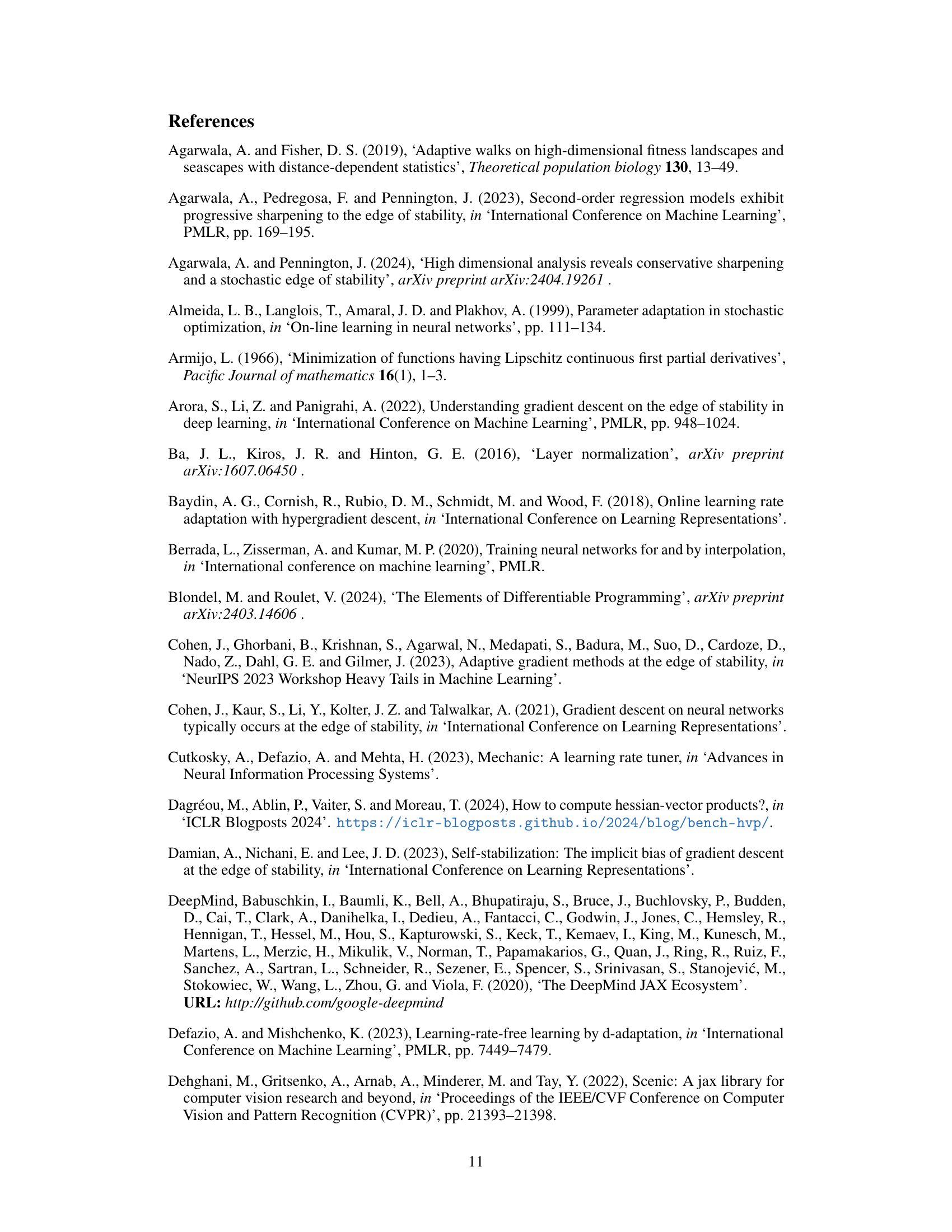

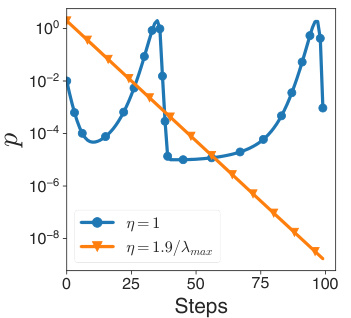

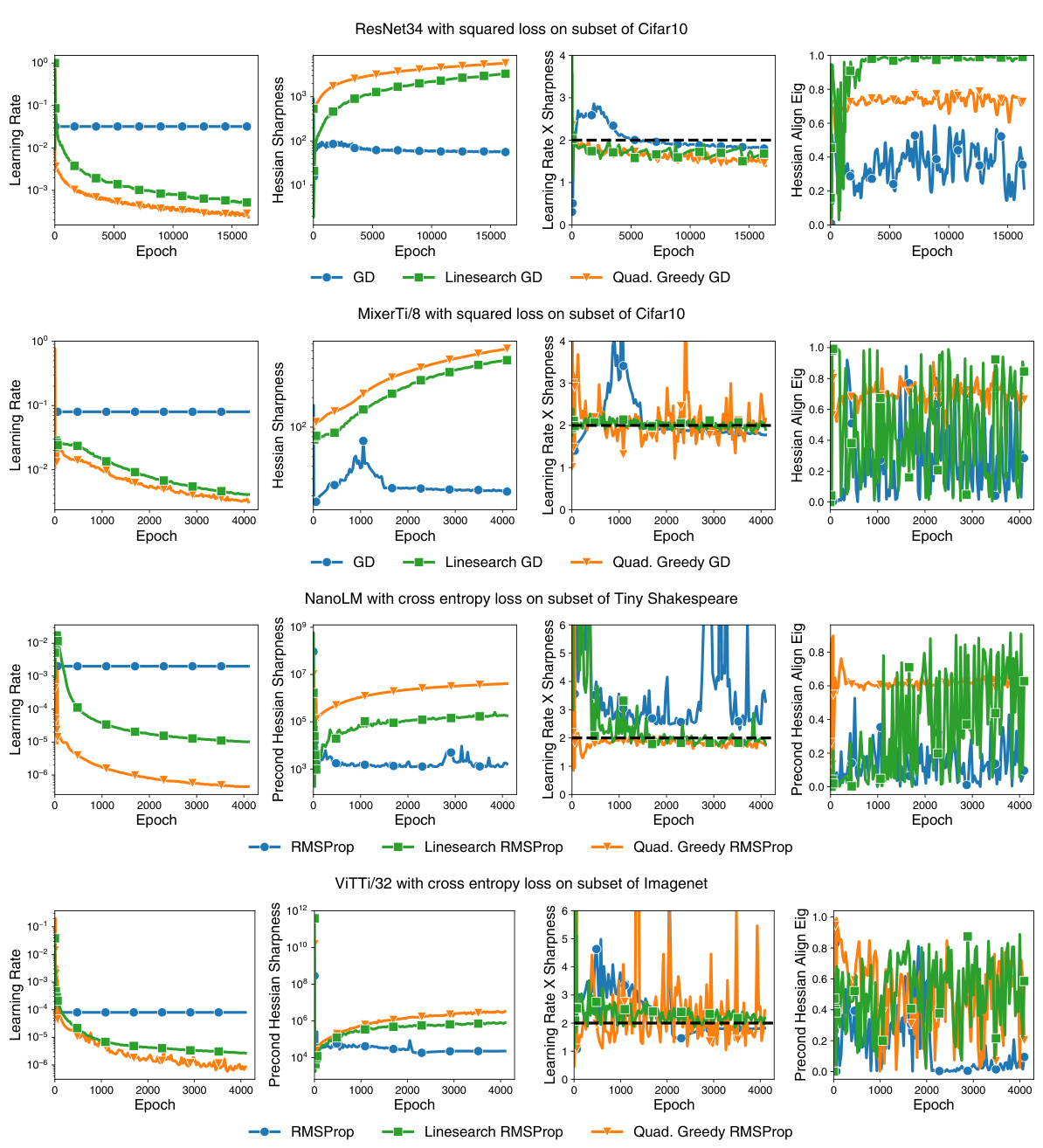

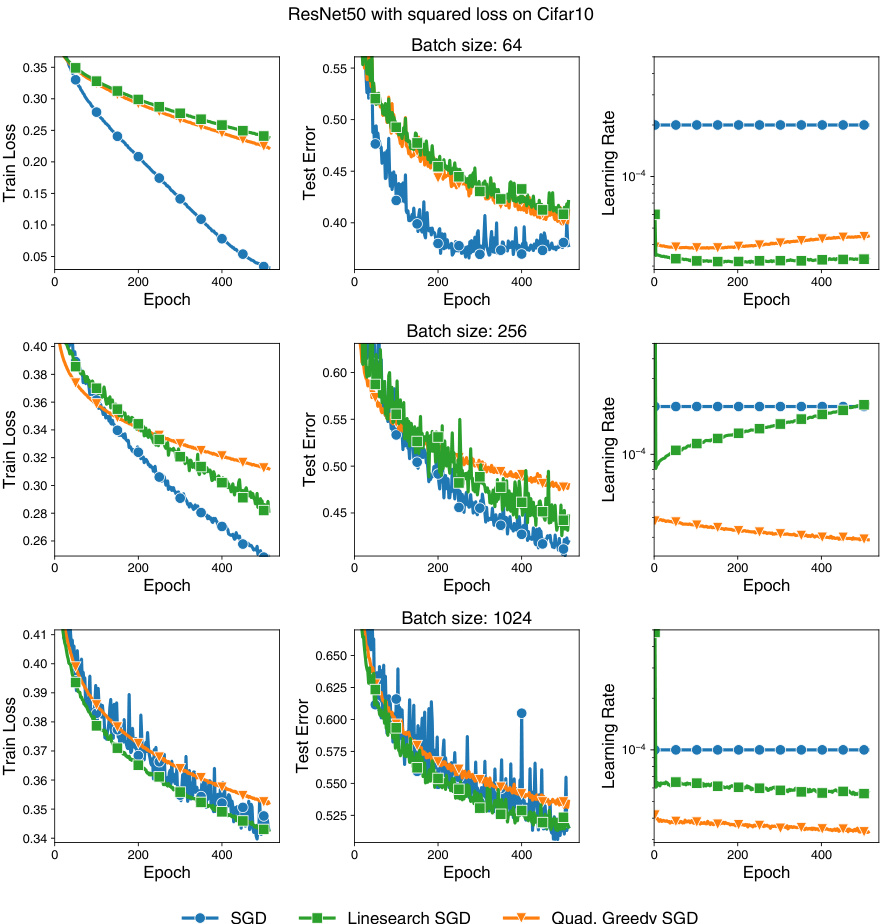

This figure compares the performance of simple learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) against constant learning rate methods (Gradient Descent and RMSProp) across various datasets and network architectures. The results show that while the tuners may initially achieve better one-step loss reduction, they ultimately underperform constant learning rates in the long term, particularly in the full batch setting. The linesearch method sometimes shows an initial advantage but fails to maintain progress over time.

In-depth insights#

LR Tuner Failure#

The paper investigates the failure modes of classical learning rate tuners (LRTs) in deep learning. A key finding is that while LRTs might show initially better one-step loss reduction compared to constant learning rates, they ultimately underperform in the long run. This underperformance is attributed to a disruption of the natural stabilization of loss curvature during training. Classical LRTs often undershoot the edge of stability (EOS), leading to a snowball effect where sharpness increases and learning rates decrease, resulting in slow training progress. The closed-loop interaction between LRTs and curvature dynamics is critical. The authors introduce Curvature Dynamics Aware Tuning (CDAT) which aims to stabilize curvature near the EOS, effectively emulating a warm-up schedule. CDAT demonstrates superior long-term performance in the full-batch setting, suggesting that curvature stabilization is more important than short-term greedy loss minimization for effective deep learning. Stochasticity in the mini-batch setting introduces additional challenges, as demonstrated by empirical observations, which warrants further study to improve the design of adaptive LRTs.

Curvature Dynamics#

The concept of ‘Curvature Dynamics’ in the context of deep learning refers to the evolution of the loss function’s curvature during the training process. It’s not static; instead, it changes significantly, often transitioning from a phase of increasing sharpness (largest eigenvalue of the Hessian) to a state of relative stabilization. This dynamic interplay between curvature and learning rate is crucial. Classical learning rate tuners, aiming for immediate loss reduction, often disrupt this stabilization, leading to long-term underperformance compared to constant learning rates. Understanding these dynamics is key to designing effective adaptive learning rate tuners, moving beyond a purely greedy minimization approach and towards strategies that prioritize long-term curvature stabilization. The edge of stability (EOS), a critical point where sharpness stabilizes, is a key element of this analysis. The paper suggests that maintaining proximity to the EOS is beneficial for training stability, a concept further explored by introducing the Curvature Dynamics Aware Tuning (CDAT) method.

CDAT Method#

The CDAT (Curvature Dynamics Aware Tuning) method is a novel learning rate tuner that prioritizes long-term curvature stabilization over immediate loss reduction. Unlike traditional tuners that focus on short-term greedy minimization, CDAT dynamically adjusts the learning rate to maintain the optimizer near the edge of stability (EOS). This approach is crucial because classical methods often undershoot the EOS, leading to a snowball effect of decreasing learning rates and increasing sharpness. By focusing on stability, CDAT empirically outperforms tuned constant learning rates in the full-batch setting, exhibiting behavior similar to prefixed warm-up schedules. However, the effectiveness of CDAT in the mini-batch setting is less consistent due to the increased stochasticity, highlighting the importance of considering the interplay between learning rate and curvature dynamics for effective adaptive learning rate tuning.

Stochastic Effects#

Stochasticity, inherent in mini-batch training, significantly impacts the dynamics observed in full-batch settings. The success of classical learning rate tuners in mini-batch regimes is not solely attributable to their inherent design but also influenced by the reduced and attenuated sharpness dynamics present in stochastic optimization. The analysis suggests that the stochastic nature of mini-batch gradient descent introduces confounding effects, masking the true behavior of learning rate tuners and the sharpness. Consequently, simply translating full-batch observations to mini-batch training can be misleading. Furthermore, the optimal scaling factor for techniques like Curvature Dynamics Aware Tuning (CDAT) is heavily dependent on batch size, further highlighting the need to consider stochastic effects when designing and analyzing learning rate tuners. Understanding and modeling these effects is critical for developing robust and effective adaptive learning rate methods applicable across various batch sizes.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several key areas. Extending the theoretical model to more accurately capture the complexities of stochastic optimization and higher-order effects is crucial. This might involve incorporating techniques from control theory to design learning rate tuners that ensure greater stability and efficiency, particularly in mini-batch settings. Investigating alternative metrics for sharpness beyond the largest eigenvalue of the Hessian, such as the trace of the Hessian, might reveal more robust ways to gauge curvature dynamics. Further work could focus on developing methods to estimate these metrics efficiently and reliably, especially in stochastic regimes. A detailed empirical investigation into how different optimizers interact with CDAT and how CDAT’s performance changes in relation to architectural choices is needed. It would be beneficial to explore the application of CDAT to more complex architectures and larger-scale models. Finally, it’s important to develop more comprehensive models that capture the joint dynamics of the learning rate and curvature in stochastic settings, to better understand the success of various learning rate tuners at different batch sizes.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure compares the performance of simple learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) against constant learning rate methods (Gradient Descent and RMSProp) across various datasets and model architectures in a full-batch setting. It shows that while the tuners might initially show faster loss reduction, they eventually underperform constant learning rates in the long run.

This figure compares the performance of simple learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) against a constant learning rate for various deep learning models in a full-batch setting. It shows that while the tuners might offer better loss reduction initially, they eventually underperform the constant learning rate in the long run.

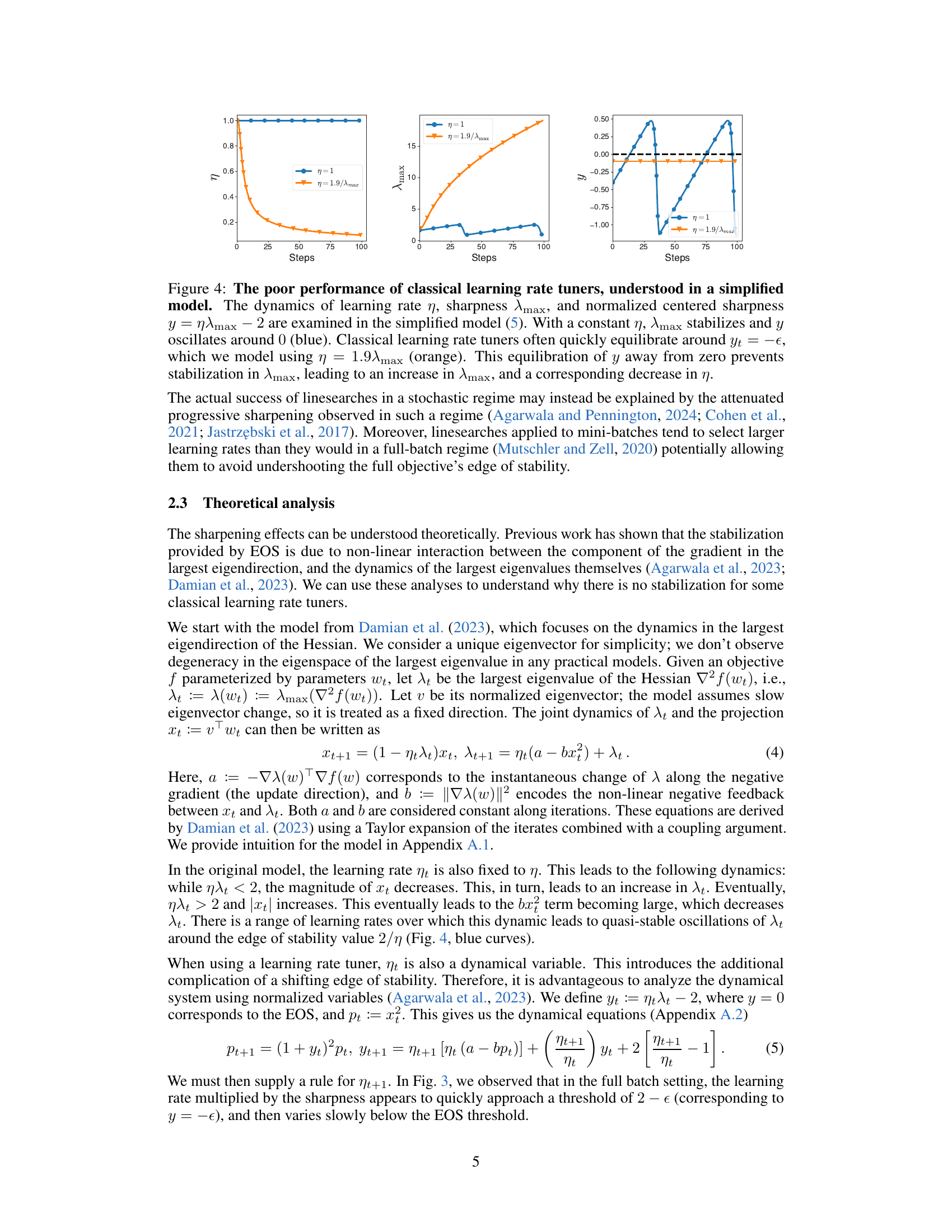

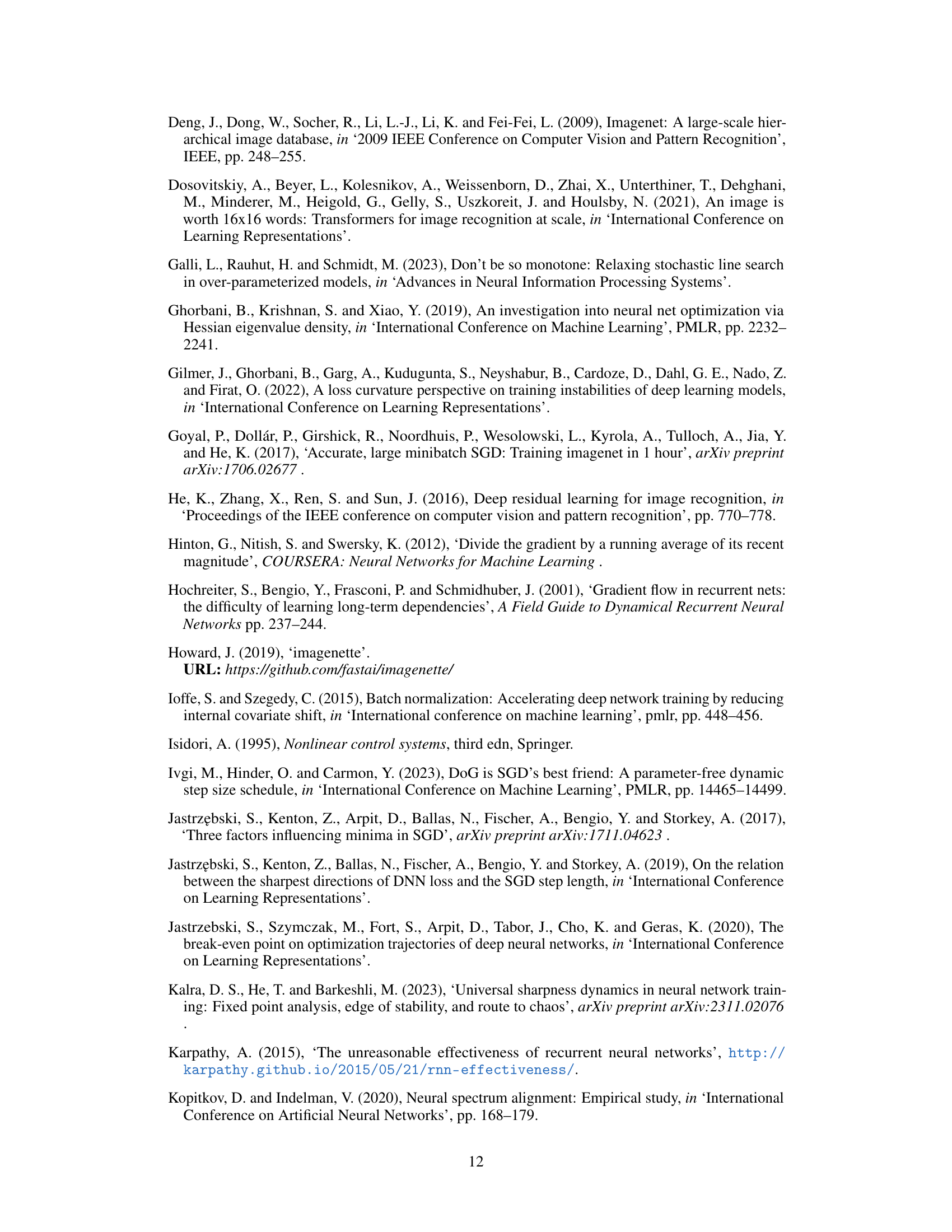

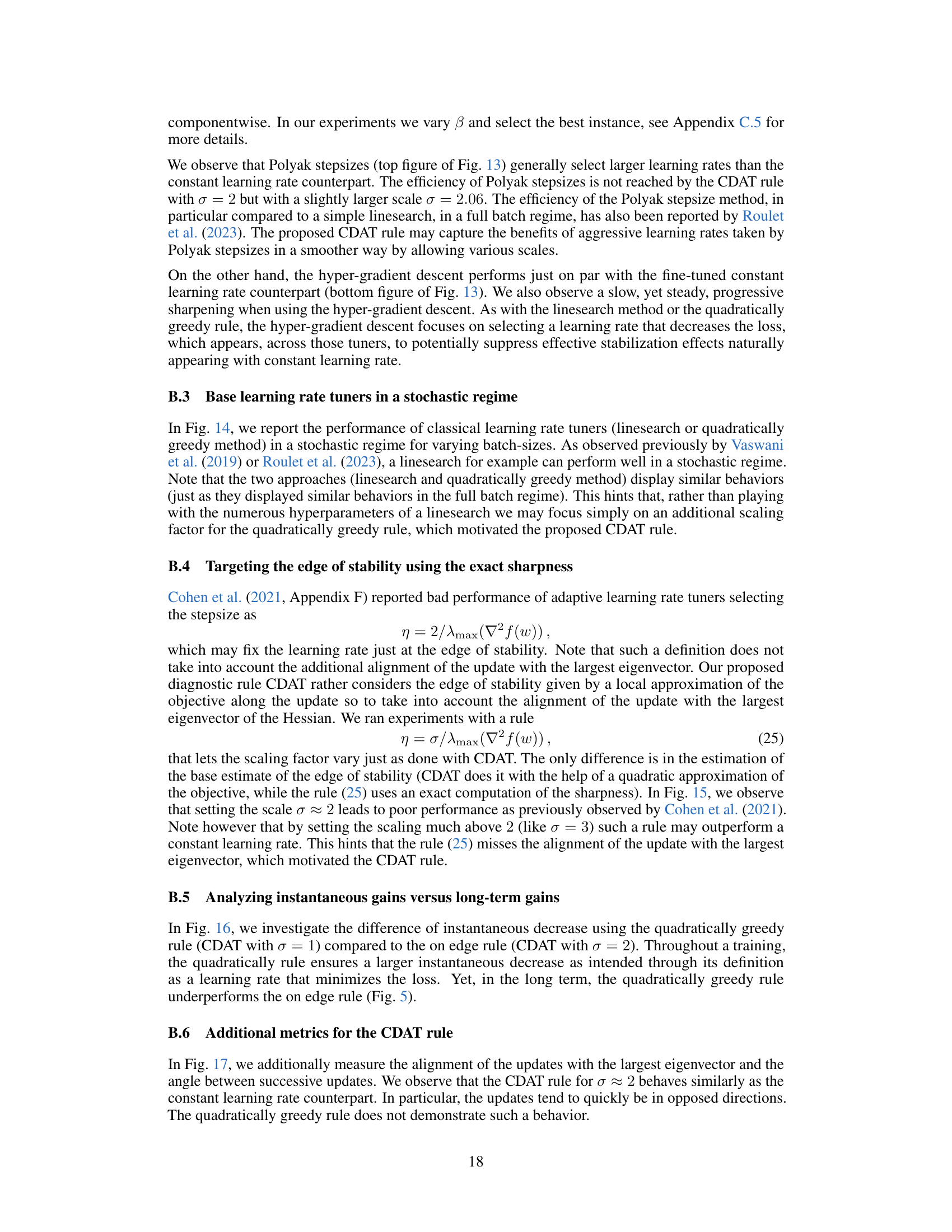

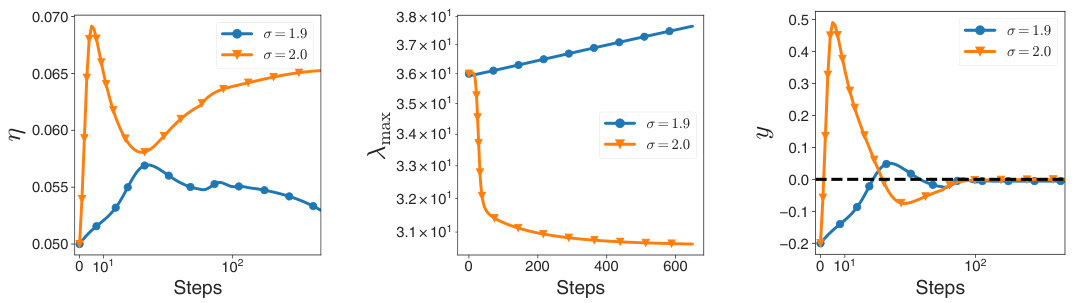

This figure shows the results of a simplified model to explain why classical learning rate tuners fail in deep learning. The model considers the dynamics of the learning rate (η), sharpness (λmax), and normalized centered sharpness (y). With a constant learning rate, the sharpness stabilizes, and the normalized centered sharpness oscillates around zero. However, classical learning rate tuners quickly reach an equilibrium where y is negative, preventing the stabilization of sharpness and leading to a decrease in the learning rate.

The figure compares the performance of simple learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) against constant learning rate methods (Gradient Descent and RMSProp) across various deep learning tasks. It shows that while the tuners might achieve better short-term loss reduction, they ultimately underperform constant learning rates in the long run, especially in full-batch settings. This underperformance is attributed to the tuners’ failure to maintain long-term curvature stabilization.

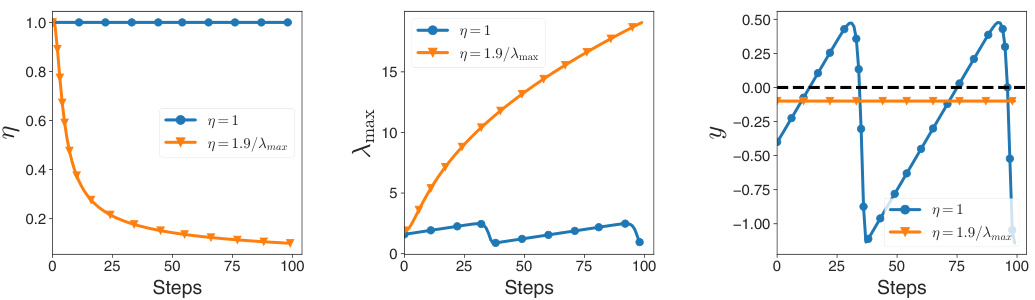

This figure shows that classical learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) do not perform as well as a constant learning rate in the long run. The learning rate decreases significantly, while the sharpness (largest eigenvalue of the Hessian) increases. Their product remains relatively constant, but below the edge of stability. This contrasts with a constant learning rate where both sharpness and learning rate stabilize. The gradient norm also indicates slower training for the learning rate tuners.

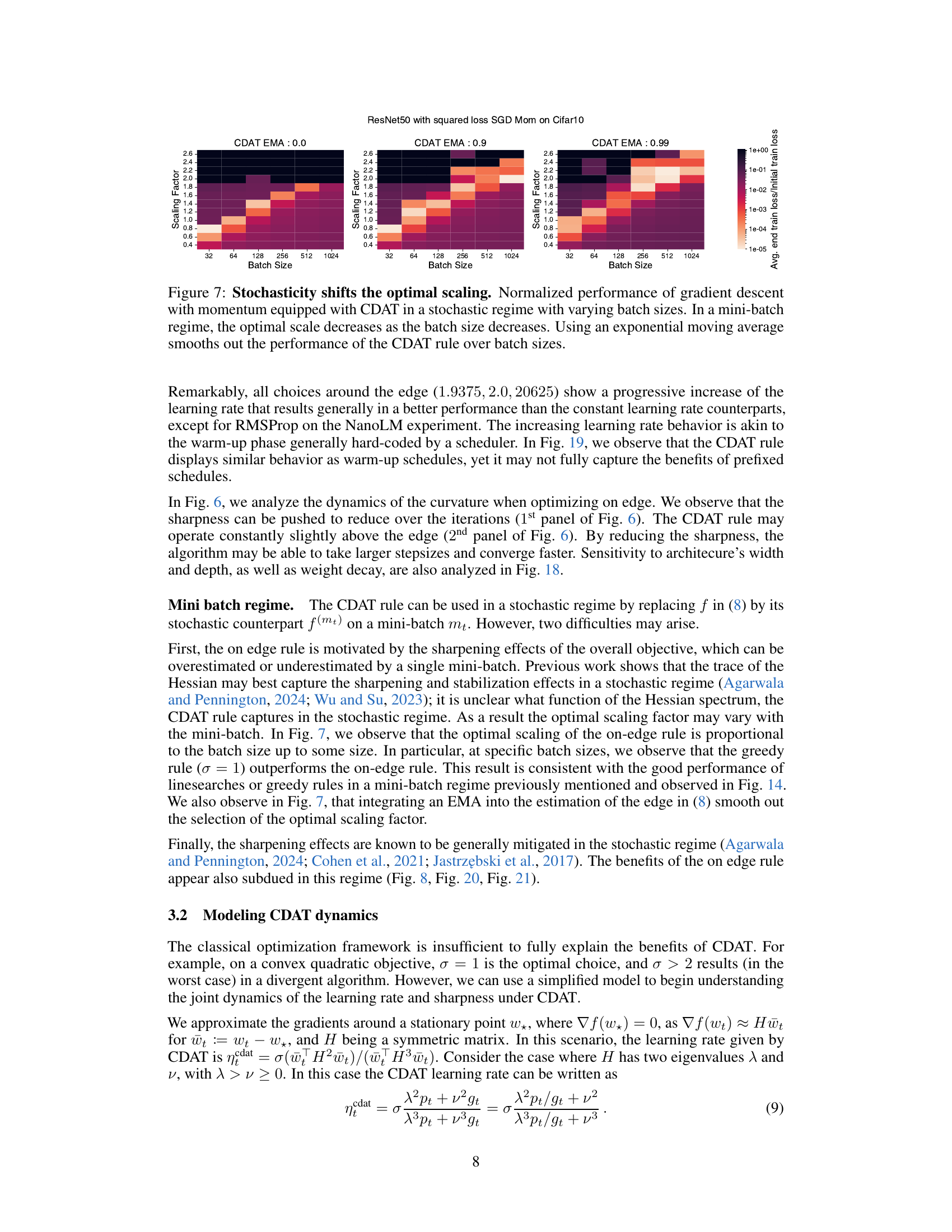

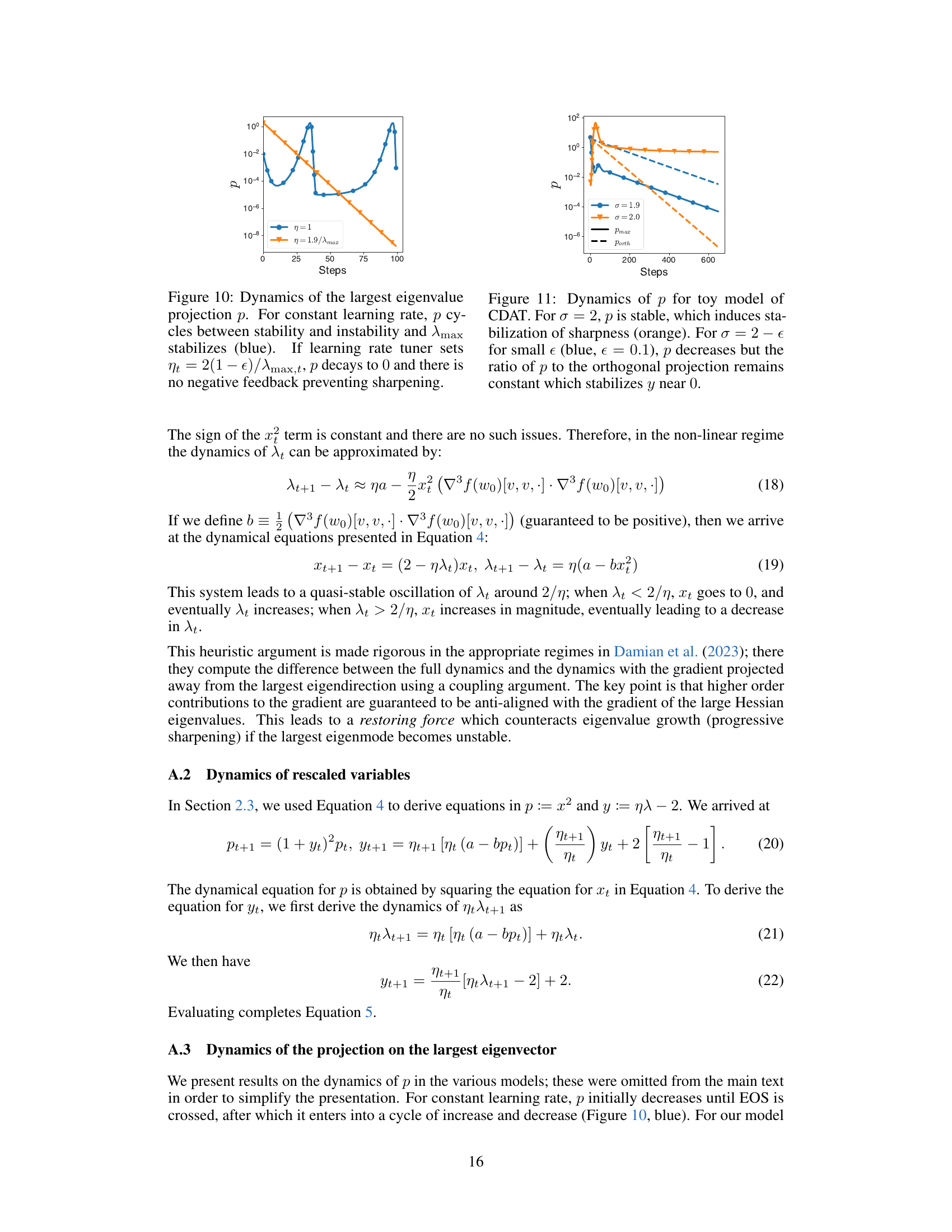

This figure shows the impact of batch size on the performance of the CDAT learning rate tuning method in a stochastic setting (mini-batch). The heatmaps illustrate the normalized performance (average end train loss divided by initial train loss) for different CDAT scaling factors and batch sizes. The results indicate that the optimal scaling factor for CDAT decreases as the batch size decreases. Applying an exponential moving average to the CDAT estimates mitigates the effect of batch size variations.

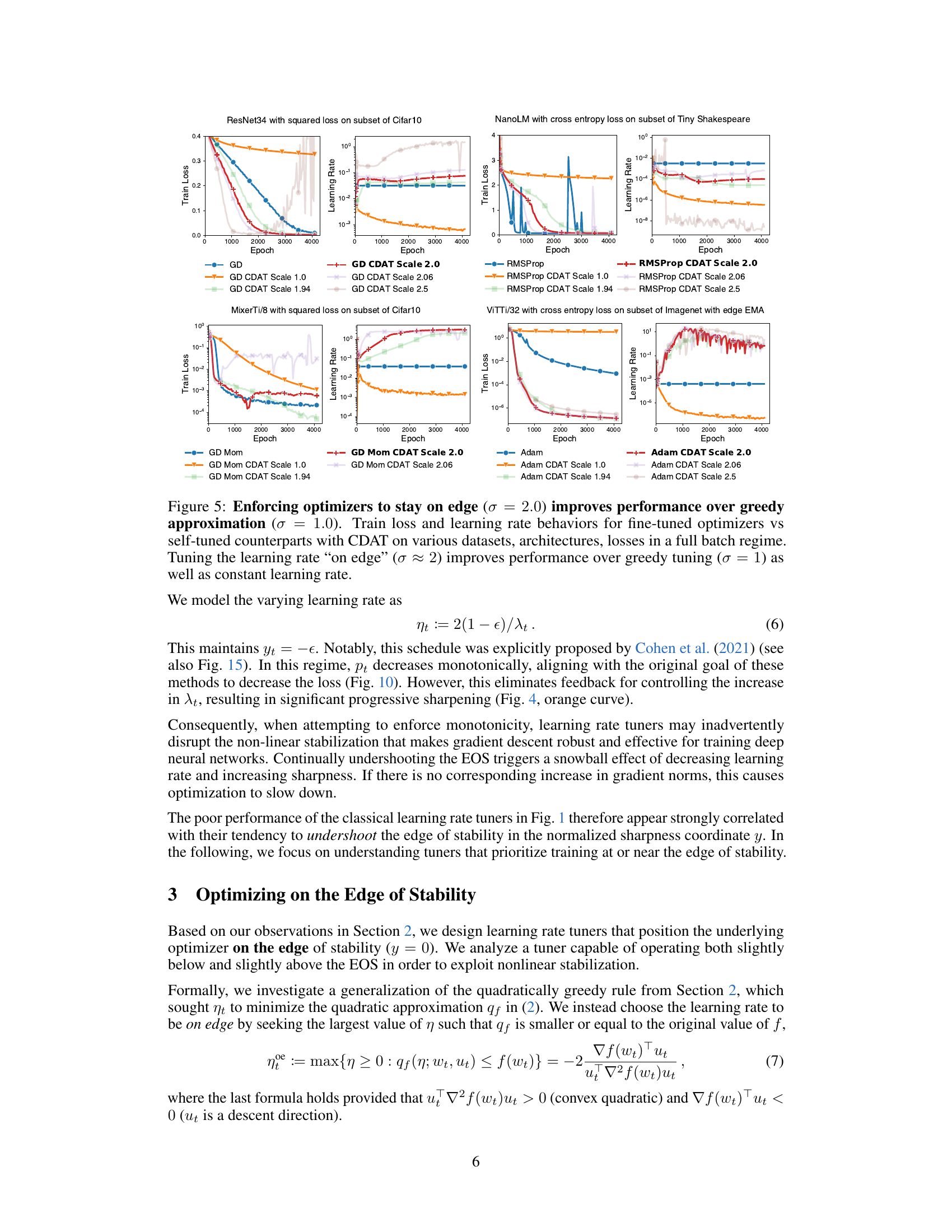

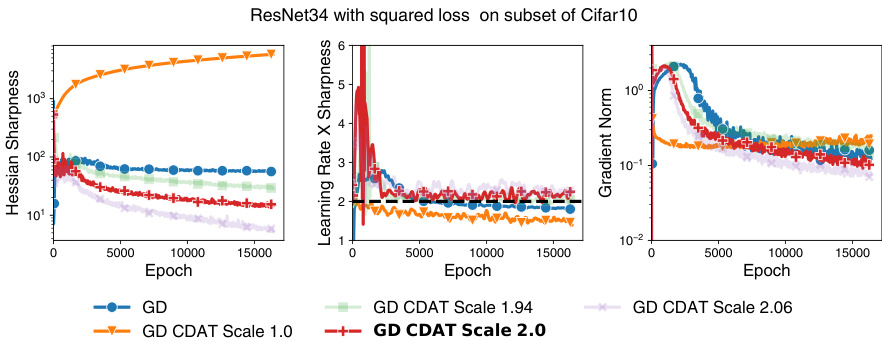

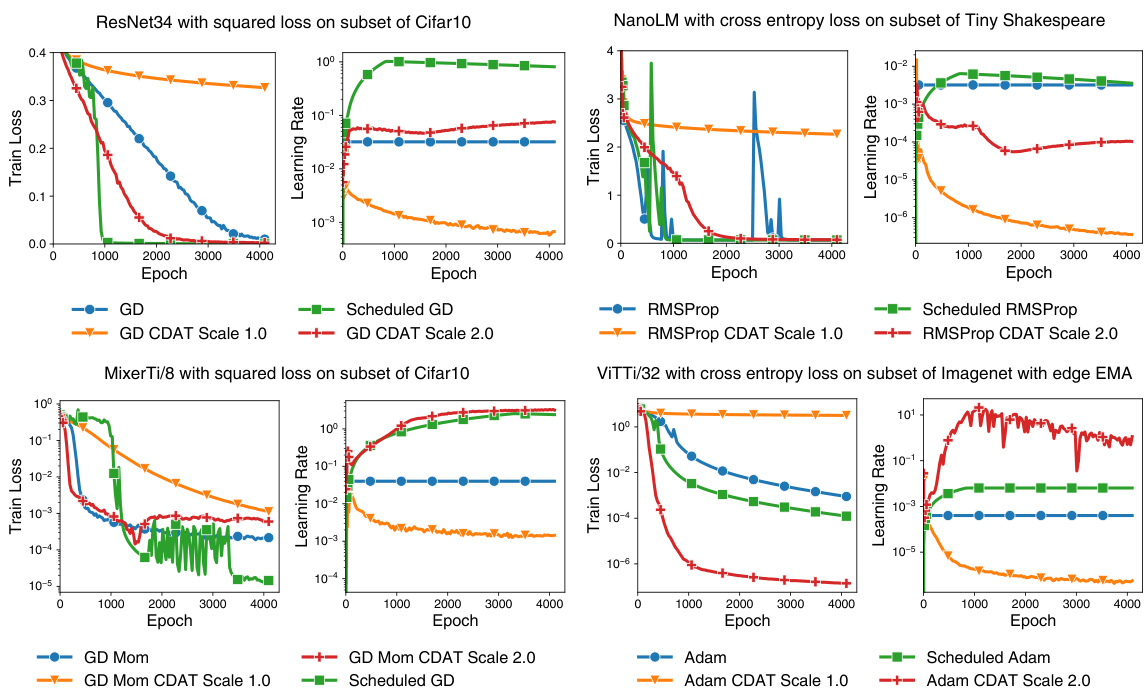

This figure displays the training loss and learning rate curves for different optimizers (GD, RMSProp, Adam with momentum) using both a constant learning rate, a scheduled learning rate, and the proposed CDAT method with scaling factors σ=1.0 and σ=2.0. The results demonstrate that tuning the learning rate to be near the ’edge of stability’ (σ≈2) yields significantly better results than using a constant learning rate or a greedy approach (σ=1.0) across various architectures and datasets. This supports the paper’s claim that focusing on curvature stabilization is key for successful adaptive learning rate tuning.

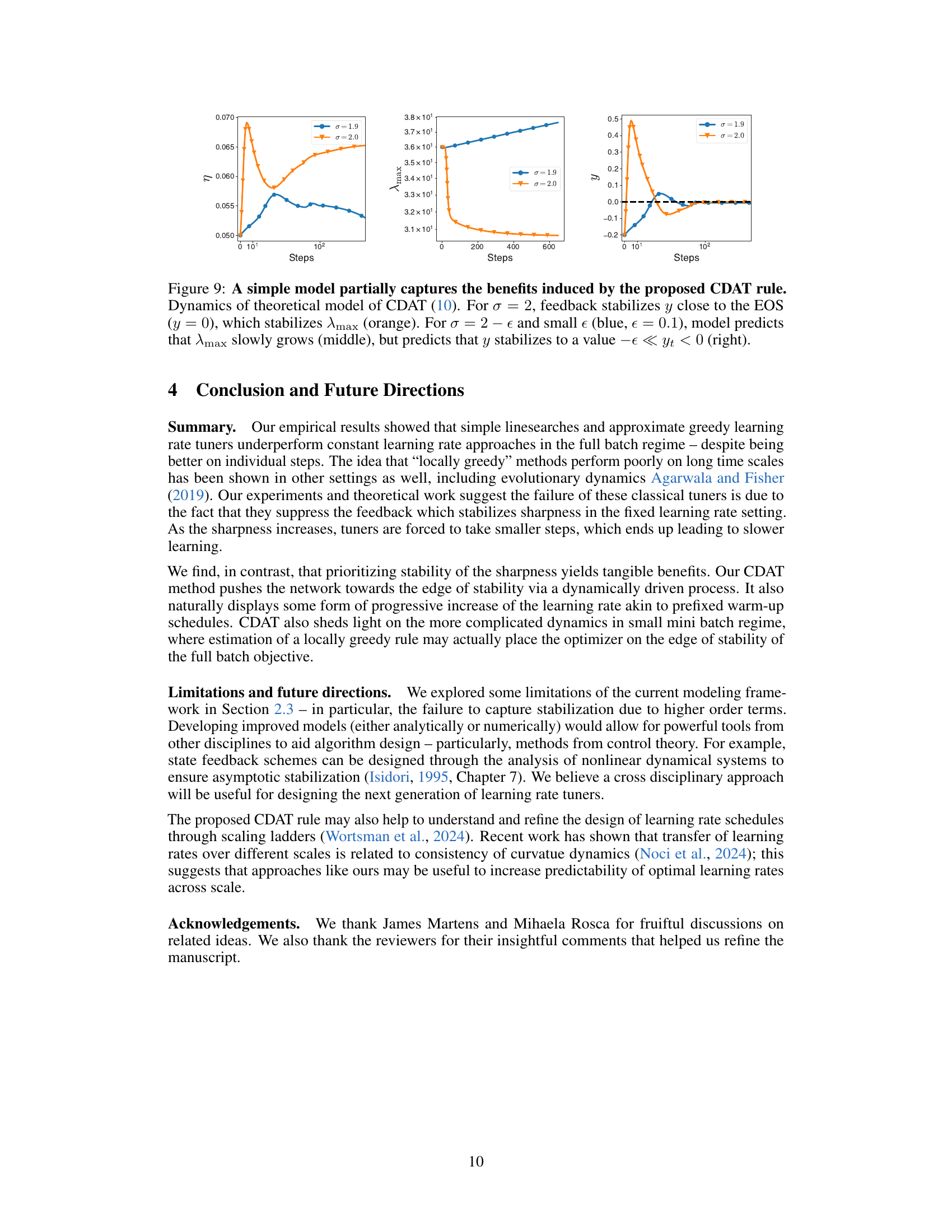

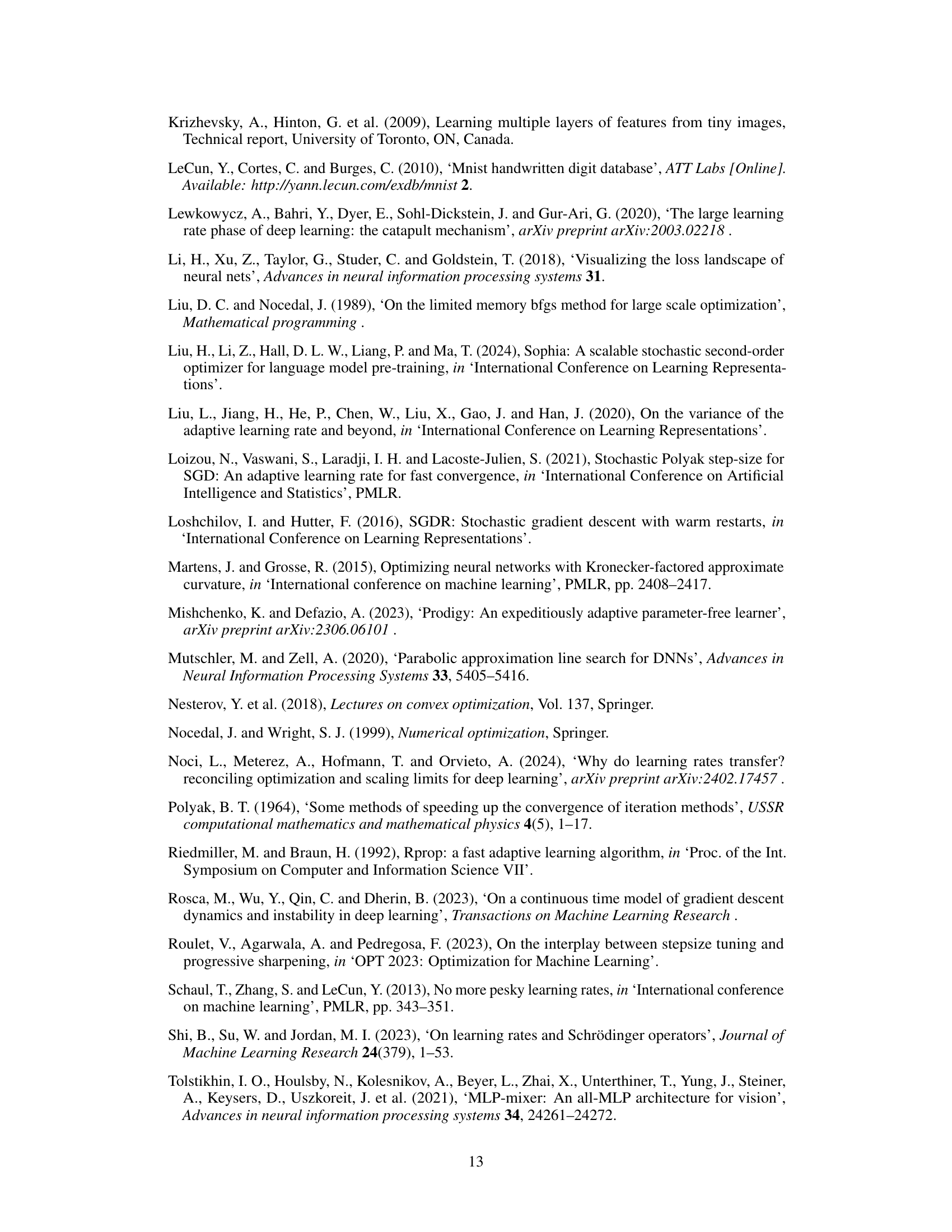

This figure shows the results of a simplified theoretical model used to understand the dynamics of the proposed CDAT learning rate tuner. The model simulates the interaction between the learning rate (η), sharpness (λmax), and a normalized centered sharpness (y). The results for σ = 2 demonstrate that CDAT stabilizes y near the EOS (y=0), leading to a stable λmax. However, when σ is slightly less than 2, the model predicts that λmax will slowly increase while y stabilizes to a small negative value, indicating a less stable regime.

This figure shows the dynamics of learning rate (η), sharpness (λmax), and normalized centered sharpness (y) using a simplified model. A constant learning rate leads to stable sharpness and oscillating y around 0. However, classical learning rate tuners cause y to stabilize away from 0, preventing sharpness stabilization and leading to increased sharpness and decreased learning rate.

This figure shows the results of a simplified model used to explain the behavior of classical learning rate tuners. The model simulates the interaction between the learning rate (η), sharpness (λmax), and a normalized measure of sharpness (y). It demonstrates that constant learning rates lead to a stable sharpness, while classical tuners cause the sharpness to increase and the learning rate to decrease.

This figure compares the performance of simple learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) against constant learning rate methods (Gradient Descent and RMSProp) across different datasets and model architectures. The results show that while the tuners might exhibit better performance initially, they ultimately underperform the constant learning rate methods in the long run, especially in a full-batch setting.

This figure displays the learning rate, sharpness (largest eigenvalue of the Hessian), the product of the learning rate and sharpness, and the alignment of the update with the largest eigenvector of the Hessian for three different learning rate tuning methods and a baseline of constant learning rate. It shows that classical learning rate tuners tend to undershoot the edge of stability, leading to decreasing learning rates and increasing sharpness.

This figure compares the performance of simple learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) against constant learning rate approaches (Gradient Descent and RMSProp) on various datasets and architectures. The experiment is performed in a full-batch setting. The results show that while the linesearch method might show better performance initially, the constant learning rate methods ultimately outperform the tuners in the long run, highlighting the limitations of greedy, single-step optimization approaches in deep learning.

This figure compares the performance of simple learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) against constant learning rate methods (Gradient Descent and RMSProp) across various datasets, architectures, and loss functions in a full-batch setting. The results show that while the tuners might initially achieve better one-step loss reduction, they ultimately underperform tuned constant learning rates in the long run. The linesearch method shows initial improvement but eventually plateaus, highlighting the limitations of these classical approaches in deep learning.

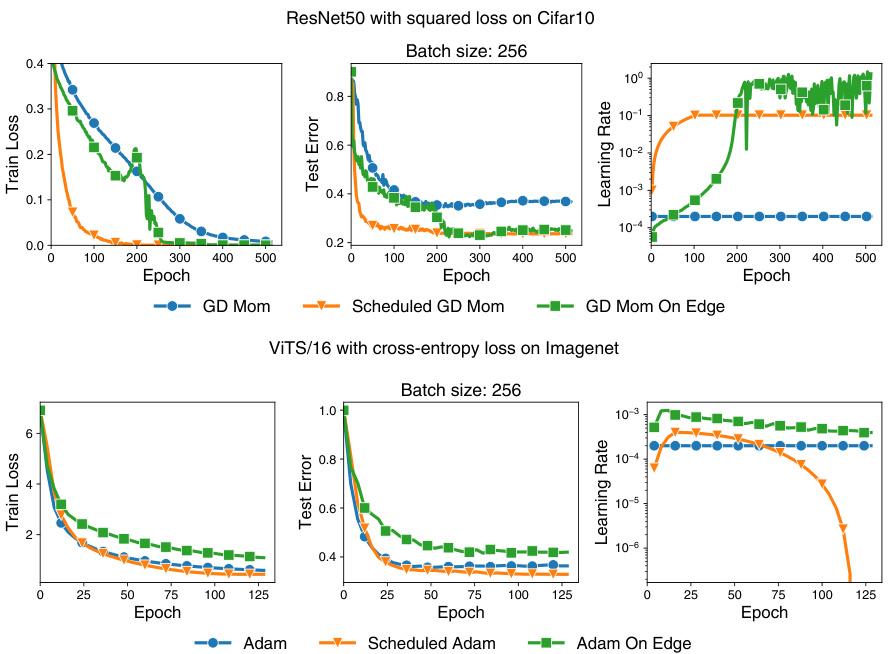

This figure compares the instantaneous and long-term performance of the quadratically greedy rule (CDAT scale 1.0) versus the on-edge rule (CDAT scale 2.0). While the quadratically greedy rule shows larger decreases in loss per step, the on-edge rule demonstrates better overall performance. The experiment uses an MLP on CIFAR100 dataset.

This figure compares the behavior of classical learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy) against a constant learning rate, using full-batch gradient descent. It shows that while the tuners initially achieve better one-step loss reduction, they ultimately underperform the constant learning rate in the long term. The analysis reveals that the tuners undershoot the edge of stability, leading to a snowball effect where sharpness increases, learning rates decrease, and progress slows.

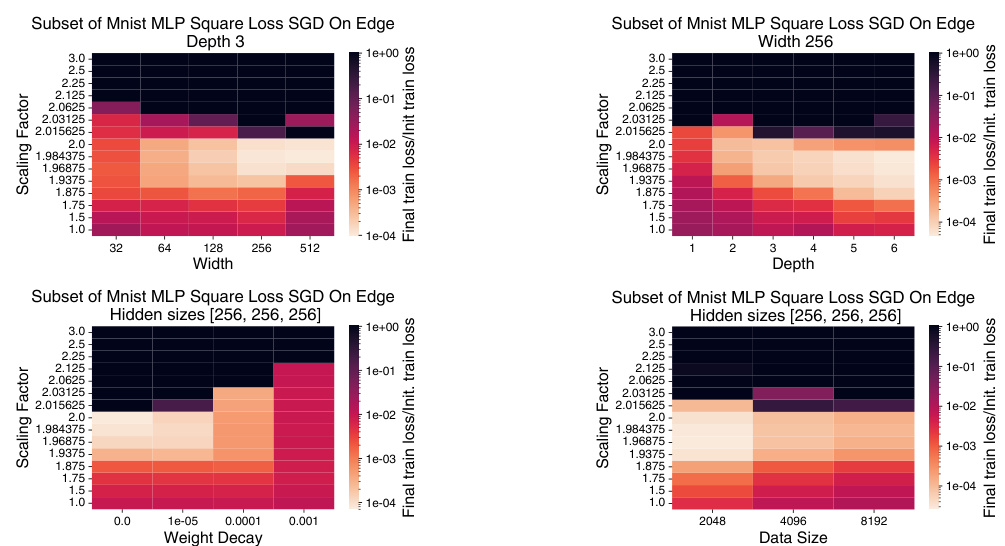

This figure shows the impact of varying hyperparameters (width, depth, weight decay, and data size) on the performance of the CDAT rule for a simple MLP model. The results demonstrate that CDAT generally performs better with larger model widths and depths. Weight decay has a significant effect, with minimal improvement seen at larger values. Changes to dataset size show marginal benefits with larger datasets.

This figure compares the performance of simple learning rate tuners (linesearch and quadratically greedy methods) against constant learning rate methods (Gradient Descent and RMSProp) across different datasets and model architectures. The results show that while the tuners may initially perform better, they eventually underperform the constant learning rate baselines, especially in the long term, within a full-batch training setting.

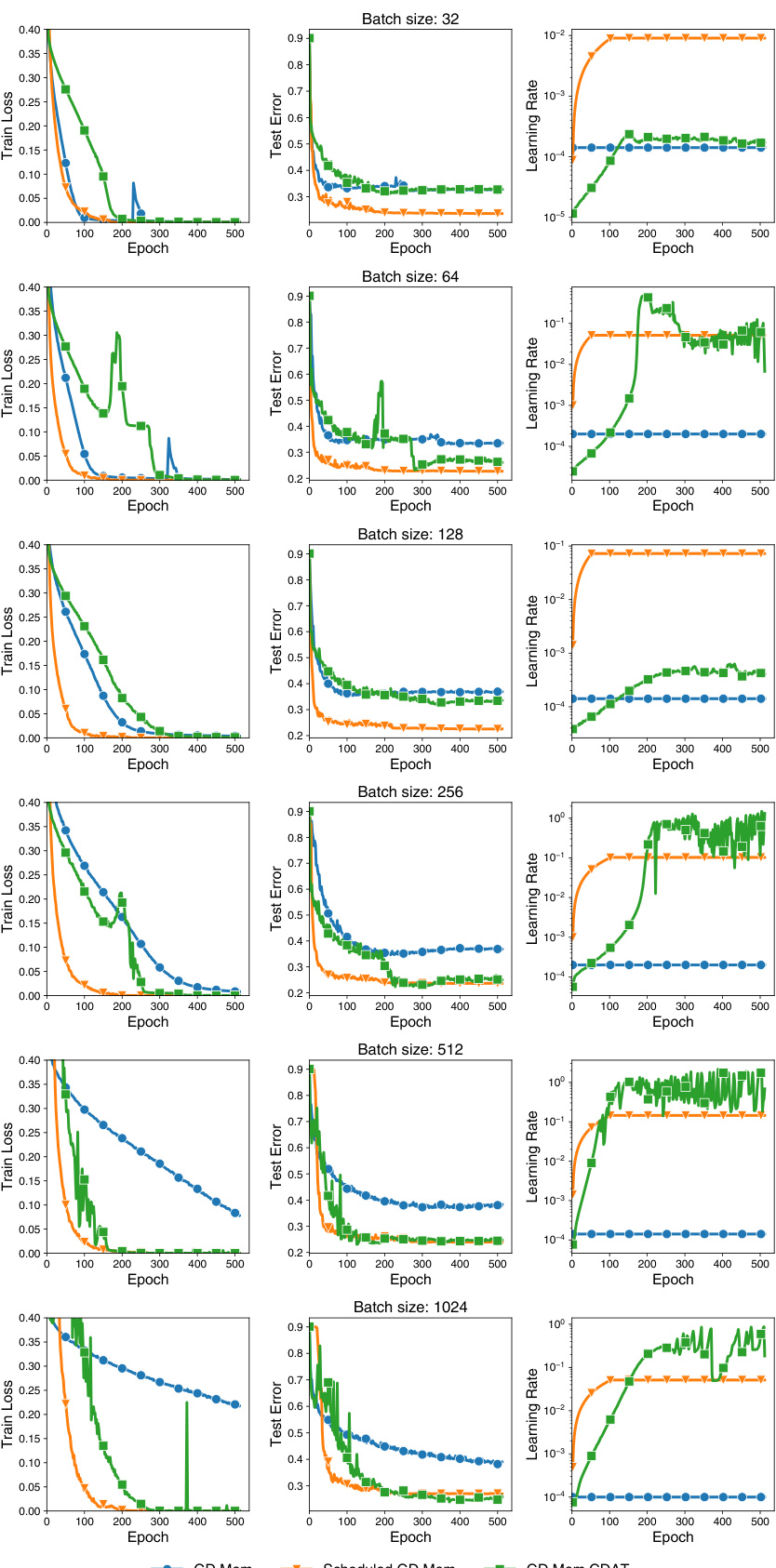

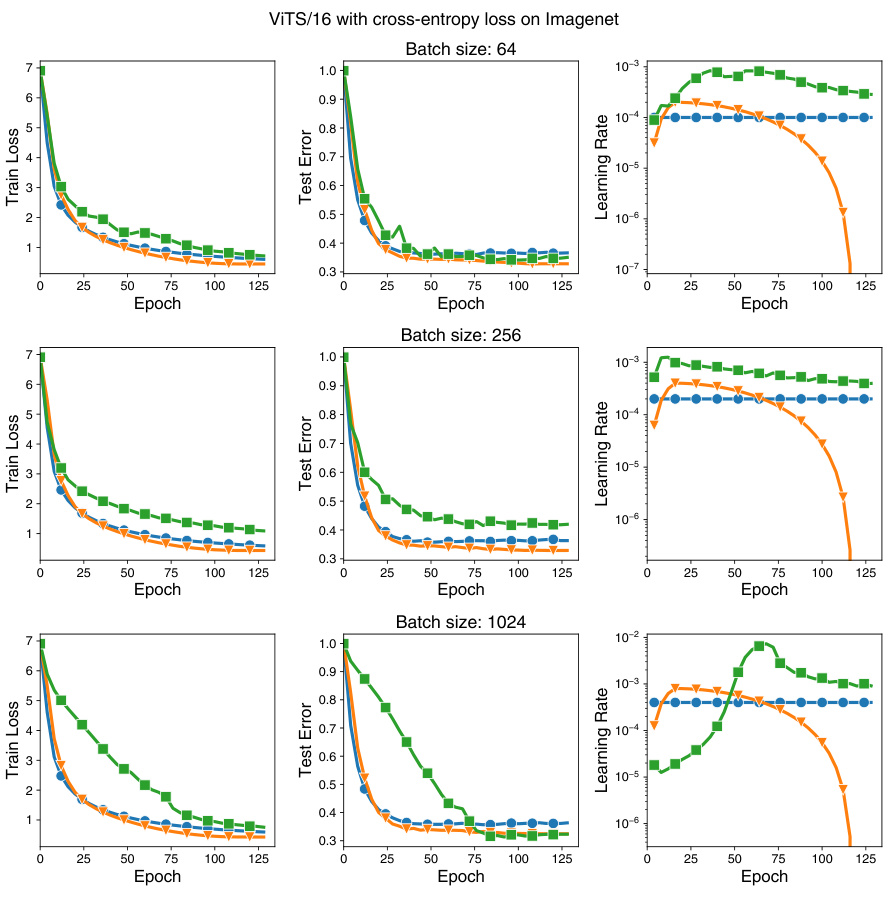

This figure shows the impact of batch size on the performance of the CDAT learning rate tuning method. The results indicate that the optimal scaling factor for CDAT decreases as the batch size decreases. This is in contrast to the full batch setting, where the optimal scaling factor remains relatively constant. The use of an exponential moving average helps to smooth out the performance fluctuations across different batch sizes, highlighting the complex interaction between stochasticity and the CDAT method.

This figure shows the impact of batch size on the performance of CDAT in a stochastic setting. The optimal scaling factor (σ) for CDAT, which aims to keep the learning rate at the edge of stability, changes with varying batch size. Smaller batch sizes result in a smaller optimal scaling factor. The use of an exponential moving average (EMA) helps stabilize the performance of CDAT across different batch sizes, smoothing out variations.

Full paper#