↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reconstructing dynamical systems from data is crucial across diverse scientific fields, but existing methods often result in complex, hard-to-interpret models. Piecewise linear (PWL) models offer improved mathematical tractability and interpretability, but creating them manually is tedious and often yields overly complex structures. This paper tackles these issues.

This research introduces Almost-Linear Recurrent Neural Networks (AL-RNNs), a novel approach to DSR. AL-RNNs automatically generate highly interpretable PWL models using as few nonlinearities as possible, resulting in minimal representations that effectively capture crucial topological properties. The AL-RNN method’s efficiency and interpretability were showcased through applications to standard chaotic systems (Lorenz and Rössler) and challenging real-world datasets (ECG and fMRI).

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents AL-RNNs, a novel approach for dynamical systems reconstruction (DSR) that yields highly interpretable symbolic codes. This method is significant due to its ability to handle complex, high-dimensional data and its capacity to provide easily understandable symbolic representations, facilitating both mathematical and computational analysis. The findings of this study could significantly improve the analysis of complex systems across various scientific domains and pave the way for developing more advanced and interpretable machine learning models for DSR.

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the architecture of the Almost-Linear Recurrent Neural Network (AL-RNN). It shows three types of neurons: N linear readout neurons that directly receive input from the time series data, L linear non-readout neurons that are fully connected to the other neurons, and P piecewise linear (PWL) neurons that introduce nonlinearities into the network. The figure also shows how the activation of the PWL neurons is represented symbolically, using a binary code that represents the activation pattern in each of the 2^P subregions.

This table compares the performance of the Almost-Linear Recurrent Neural Networks (AL-RNN) model to other state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods for dynamical systems reconstruction (DSR) across several datasets. The metrics used for comparison are the state-space divergence (Dstsp), the Hellinger distance (DH), and the number of time steps ( 0). The table highlights AL-RNN’s competitive performance and its ability to achieve comparable or better results with fewer parameters. The abbreviations id-TF and GTF represent identity teacher forcing and generalized teacher forcing, respectively.

In-depth insights#

AL-RNN Model#

The AL-RNN model, a novel neural network architecture, offers a powerful approach to dynamical systems reconstruction (DSR). It cleverly combines the strengths of linear and non-linear units, using a minimal number of ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) non-linearities to achieve a parsimonious piecewise linear representation of complex dynamics. This sparsity is crucial; it enhances interpretability by reducing the number of linear subregions in the model, thus simplifying mathematical analysis. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on a large number of linear regions to approximate non-linear systems, AL-RNN efficiently captures essential topological features using only a few non-linearities. This parsimony directly translates to a symbolic encoding of the dynamics, making the model highly interpretable and facilitating the application of symbolic dynamics tools for system analysis. The inherent structure of AL-RNNs lends itself to robust and efficient training, even with challenging data. The model’s design elegantly bridges the gap between the mathematical elegance of piecewise-linear models and the practical power of deep learning techniques for DSR, demonstrating the capacity to find highly interpretable and minimal representations of complex systems from raw time series data.

Symbolic Dynamics#

Symbolic dynamics offers a powerful framework for analyzing dynamical systems by representing their continuous state space evolution as discrete symbolic sequences. This approach is particularly useful for understanding chaotic systems, where traditional methods often struggle. By partitioning the state space into a finite number of regions and assigning a unique symbol to each region, continuous trajectories are translated into symbolic sequences. The resulting symbolic dynamics often reveal fundamental properties of the system, such as topological entropy, periodic orbits, and invariant measures. A key advantage is its ability to reduce the complexity of high-dimensional, nonlinear systems to a more manageable representation. The choice of partition significantly impacts the richness and accuracy of the symbolic representation. Finding optimal partitions that capture essential dynamical features remains a key challenge. The connection between the symbolic representation and the underlying geometrical structure of the system’s attractor is crucial for interpreting results and extracting meaningful insights. This makes symbolic dynamics a powerful tool for combining mathematical analysis with computational methods for studying dynamical systems.

Minimal PWL Models#

The concept of ‘Minimal PWL Models’ within the context of dynamical systems reconstruction suggests a pursuit of parsimony and interpretability. It implies finding the simplest piecewise linear (PWL) representation that accurately captures the essential dynamics of a complex system. This is crucial because while PWL models offer a balance between mathematical tractability and the ability to represent nonlinearity, overly complex PWL models with numerous linear regions become unwieldy and lose their interpretative advantage. The quest for minimality often involves a trade-off: a model could be highly accurate but excessively complicated, or it could be simple but less precise. Therefore, finding the optimal balance is key. The value lies in the ability to extract meaningful insights from the simplified structure, enabling better understanding of the system’s underlying mechanisms and facilitating further analysis such as topological characterization and symbolic dynamics. A minimal model, if discovered, could serve as a compact and easily understandable summary of the system’s behavior, shedding light on its fundamental properties and possibly revealing hidden structures. The challenge lies in developing effective data-driven techniques to discover these minimal models robustly, given that handcrafting them is often infeasible for high-dimensional systems.

Real-World Results#

A dedicated ‘Real-World Results’ section would significantly enhance the paper’s impact by showcasing the applicability of the proposed AL-RNN approach beyond synthetic datasets. The inclusion of diverse real-world datasets, such as ECG and fMRI data, demonstrates its potential for practical applications. A detailed analysis of the results on these real-world datasets should include a discussion of challenges encountered (e.g. noise, missing data), and the robustness of the algorithm in overcoming these challenges. Direct comparisons to existing methods applied to the same real-world data are crucial to establish the AL-RNN’s efficacy. Furthermore, a qualitative assessment of the interpretability of the symbolic codes generated from the real-world data is needed, demonstrating the insights gained into the underlying dynamics. For example, detailing how the model identifies specific physiological events in the ECG data or discernable cognitive states in the fMRI data would provide strong evidence of its practical use. By meticulously addressing these points, this section could transform a promising theoretical algorithm into a validated tool for real-world dynamical system analysis. The current presentation touches on real-world data but lacks a dedicated, comprehensive analysis section to show the actual impact and benefit of the model.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the AL-RNN’s ability to automatically determine the optimal number of PWL units is crucial for broader applicability. Investigating alternative training techniques beyond sparse teacher forcing could enhance performance and efficiency. Extending the theoretical framework to non-hyperbolic systems would significantly expand the AL-RNN’s capabilities. Applying the AL-RNN to higher-dimensional and more complex real-world datasets would further validate its robustness and usefulness. Finally, developing methods for more effectively visualizing and interpreting the symbolic representations generated by the AL-RNN would greatly enhance its practical utility and facilitate deeper insights into underlying dynamics.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the symbolic dynamics approach and its geometrical representation. The left side demonstrates the process of symbolic coding, starting with a partitioning of the state space into linear subregions (2P possible subregions, given P piecewise linear neurons). A trajectory is represented as a sequence of symbols (000, 100, 110, 011, etc.), where each symbol corresponds to a subregion. The permitted transitions between symbols are shown using a symbolic graph (a topological graph representation), and the relative frequency of transitions between subregions are shown in a weighted transition graph (a geometrical graph representation). The geometrical graph uses a weighted adjacency matrix to reflect transition frequencies in the dynamics.

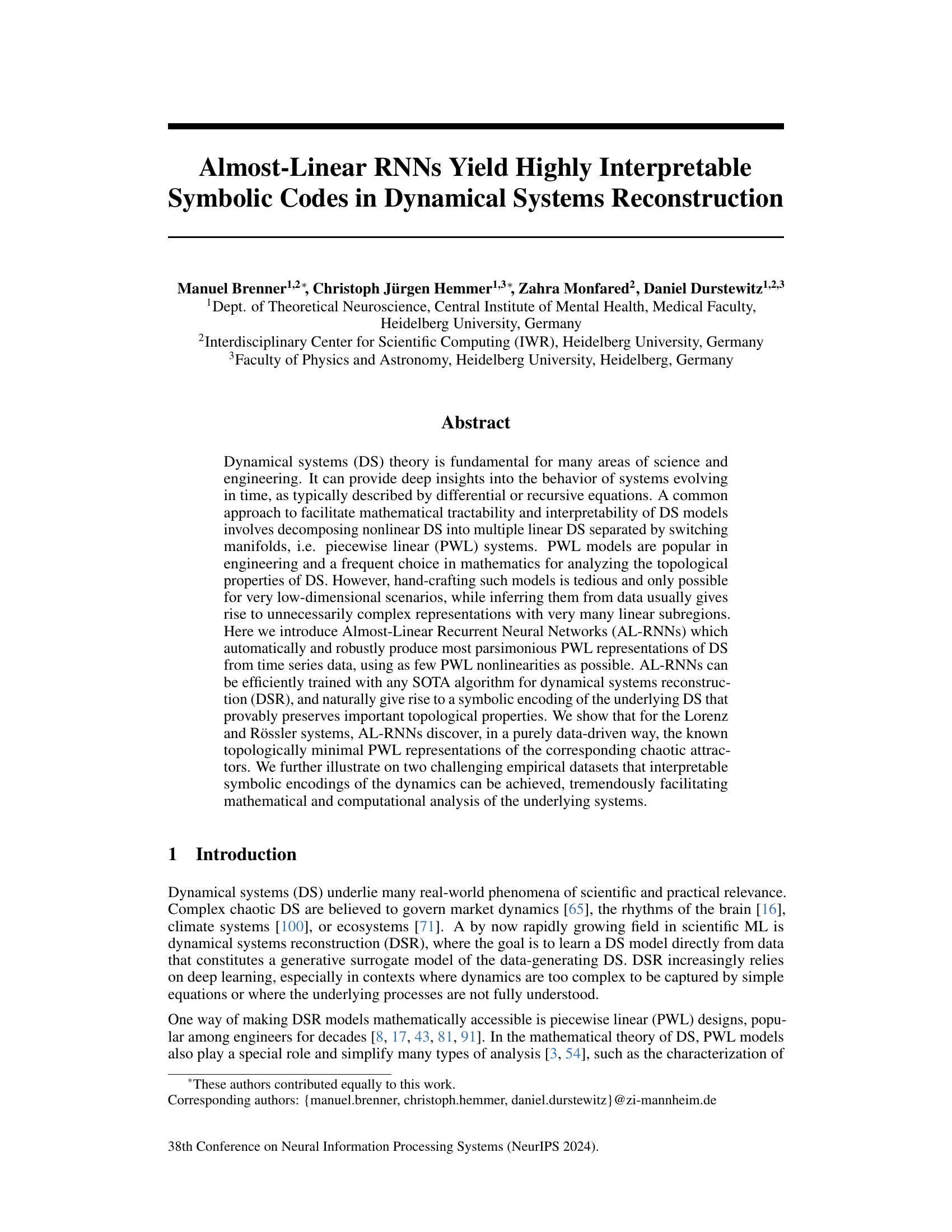

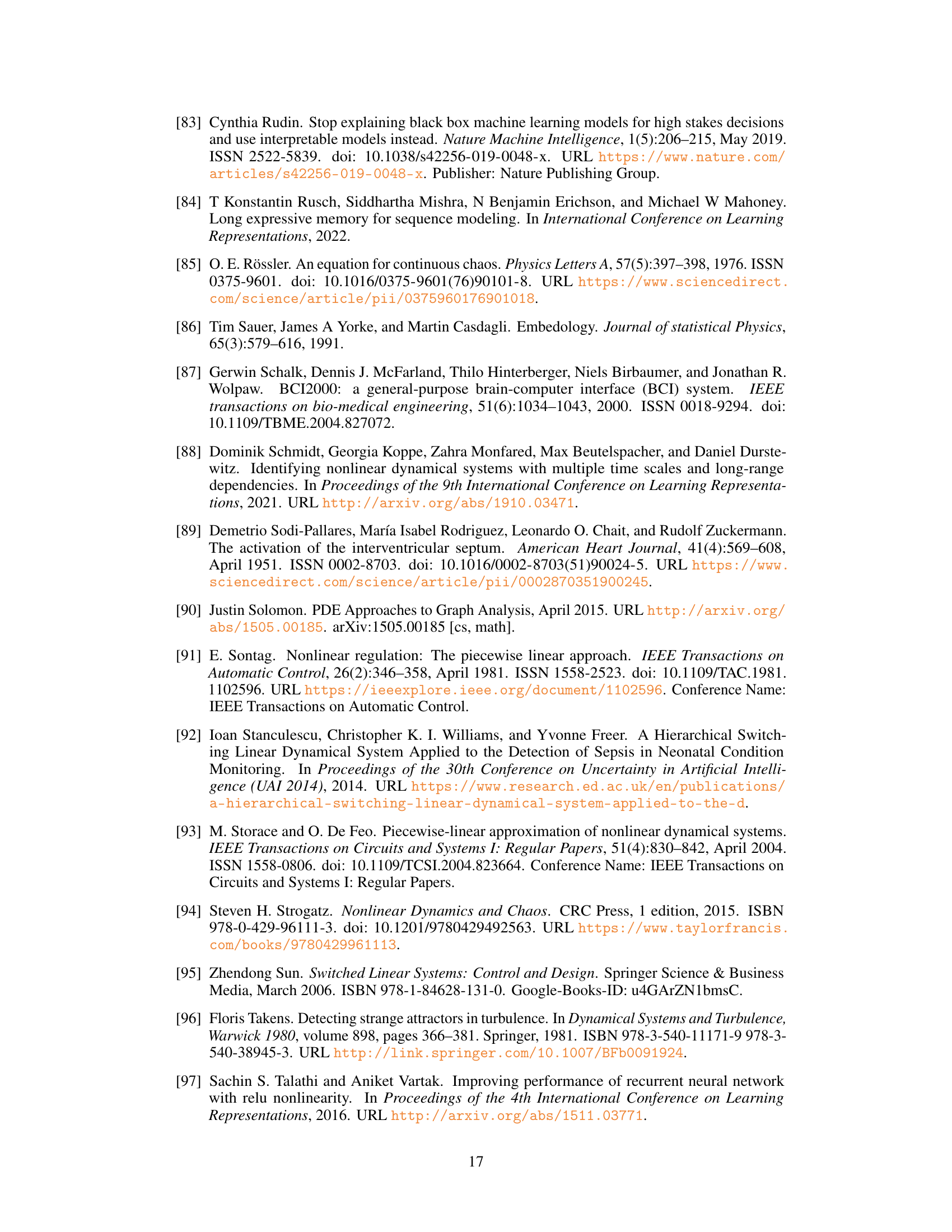

This figure displays the DSR quality (geometry and temporal structure disagreement) for the AL-RNN model across four datasets (Rössler, Lorenz-63, ECG, fMRI) as the number of ReLU (PWL) units increases. It shows that performance generally improves with more ReLU units, but the optimal number of units varies between datasets, with some datasets showing initial performance degradation before improvement.

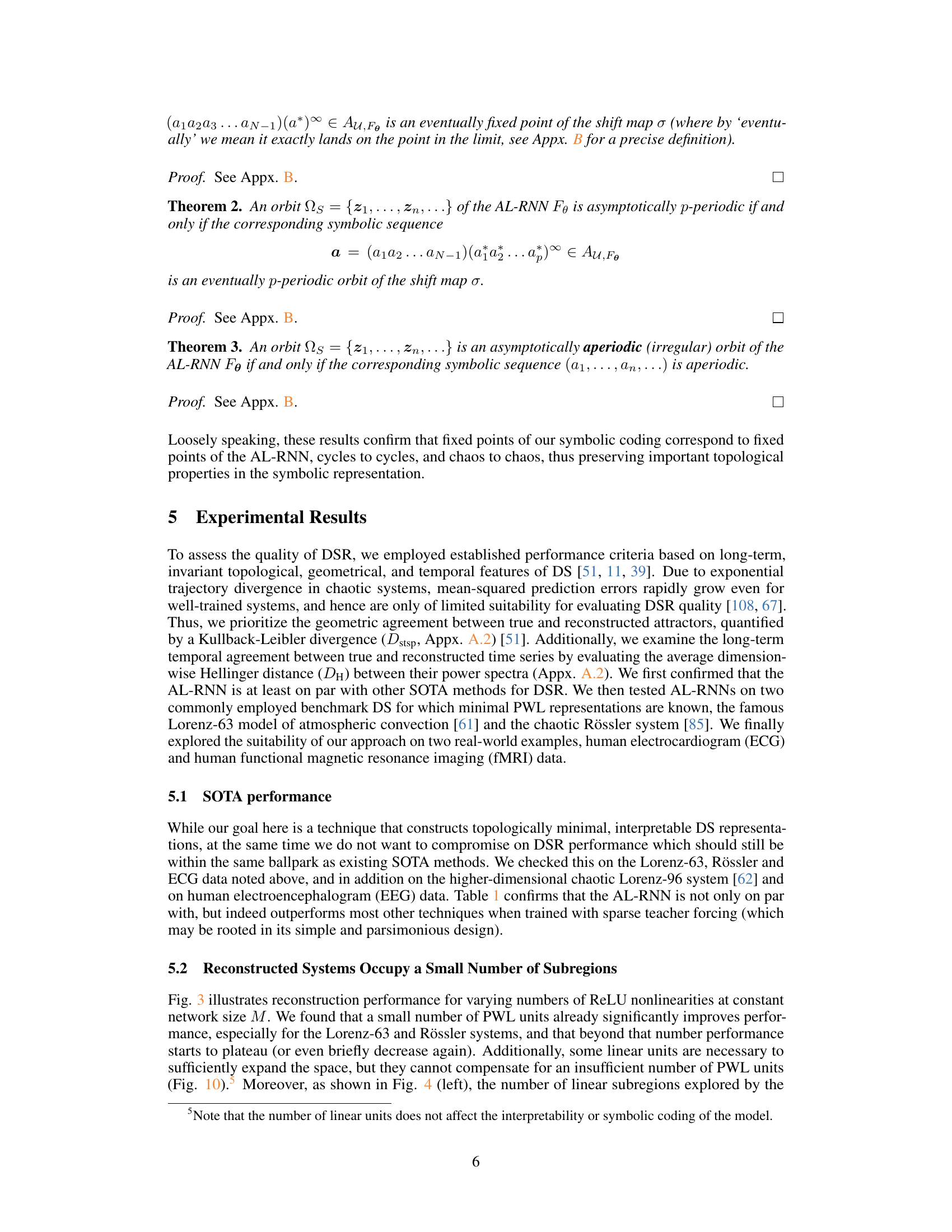

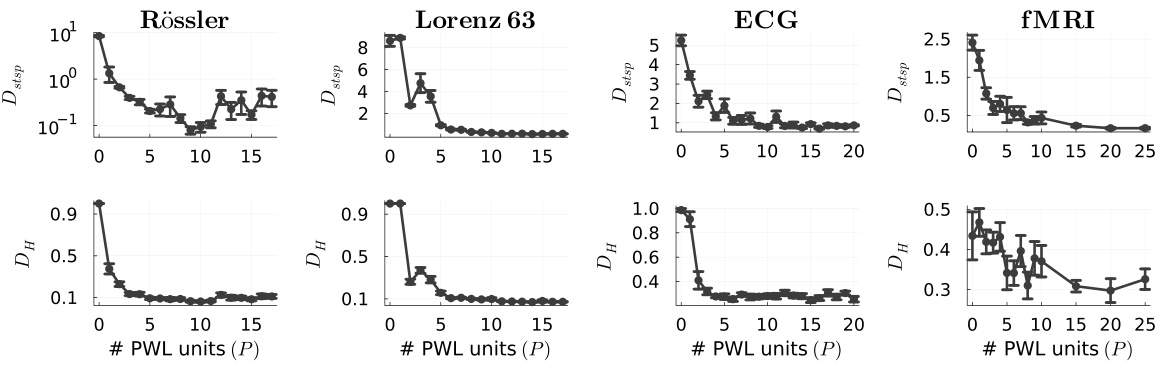

The left panel of the figure shows the number of linear subregions traversed by the AL-RNN model as a function of the number of piecewise linear (PWL) units (P) used in the model. The theoretical upper limit of 2P is shown in red. The right panel shows the cumulative percentage of data points covered by the linear subregions as the number of PWL units increases. The figure demonstrates that, even for complex systems, a majority of the data points tend to reside within a relatively small number of linear subregions.

This figure shows the topologically minimal piecewise linear (PWL) representations discovered by the AL-RNN for the Rössler and Lorenz systems. Panel (a) displays the color-coded linear subregions of the minimal AL-RNNs. Panel (b) illustrates how the AL-RNN generates chaotic dynamics in these systems. Panel (c) presents the topological graphs of the symbolic coding for both systems. Panels (d)-(f) show the robustness of these minimal representations across multiple training runs, demonstrating their topological consistency.

This figure shows the geometrically minimal reconstruction of the Rössler attractor using an AL-RNN with 10 piecewise linear units. Panel (a) displays the attractor, color-coded by the frequency of visits to each subregion. Panel (b) shows a graph representation of the attractor, where nodes represent subregions and edges represent transitions between them. The thickness of the edges reflects the frequency of transitions. Panel (c) is a connectome, visualizing the relative transition frequencies between subregions.

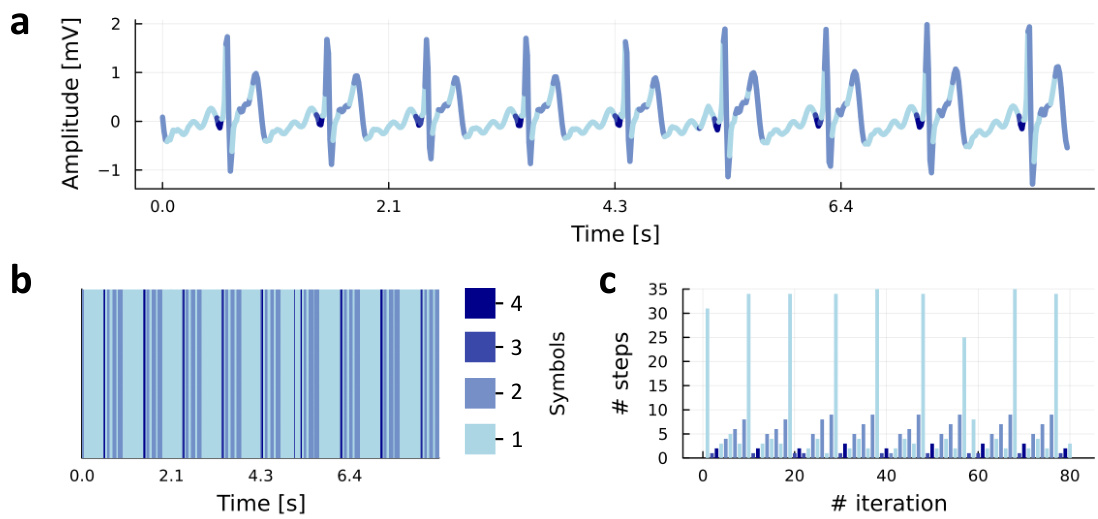

This figure shows the results of applying an AL-RNN model to generate ECG data. Panel (a) compares the generated ECG signal (colored lines) with the real ECG data (black line). The model accurately captures the main characteristics of the ECG signal, such as the QRS complex and T wave. Panel (b) illustrates the model’s ability to capture the underlying physiological processes. The strong dip in the second PWL unit after the Q wave is consistent with the known physiological mechanism of depolarization and repolarization of the interventricular septum. Panel (c) provides a visual representation of the model as a graph where each node represents a linear subregion and edges represent transitions between subregions.

This figure shows the results of applying an AL-RNN to fMRI data. Panel (a) displays the mean generated BOLD activity, with colors representing different linear subregions discovered by the AL-RNN. The background shading indicates the task stage (Rest and Instruction, CRT, CDRT, CMT). Panel (b) shows the generated activity in the latent space of the piecewise linear (PWL) units, again with colors representing the task stage. This visualization demonstrates the AL-RNN’s ability to capture the relationship between task phase and the underlying dynamics of the fMRI data.

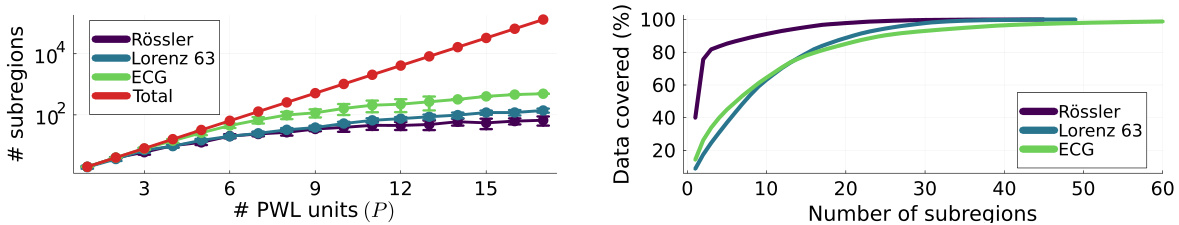

This figure shows the effect of regularization on the number of piecewise linear units used in the AL-RNN model. The top panel shows the DSR quality (Dstsp) as a function of the regularization strength (λlin), demonstrating that an optimal performance is achieved with a small number (around 2) of piecewise linear units. The bottom panel shows the number of selected piecewise linear units (P) as a function of the regularization strength, indicating that regularization effectively selects a minimal number of piecewise linear units for optimal performance. A leaky ReLU activation function was used in this experiment to control the linearity of units.

This figure examines the effect of varying the number of linear units in an AL-RNN model on its ability to reconstruct the Lorenz-63 system. It shows that the performance (measured by Dstsp and DH) plateaus or slightly decreases beyond a certain number of linear units when the number of piecewise-linear units (PWL) is insufficient to capture the system’s topology (P=1). However, when a sufficient number of PWL units is used (P=2), increasing linear units improves reconstruction up to a saturation point, demonstrating the importance of both linear and PWL units in the model’s architecture and their interplay in achieving good reconstruction performance.

This figure shows that with enough linear subregions, the AL-RNN can accurately reconstruct the geometry of the Rössler attractor. Panel (a) displays the attractor with subregions color-coded by visitation frequency. Panel (b) shows the geometrical graph representation of this reconstruction. Finally, panel (c) and (d) provide a connectome representation and matrix showing the relative transition frequencies between subregions.

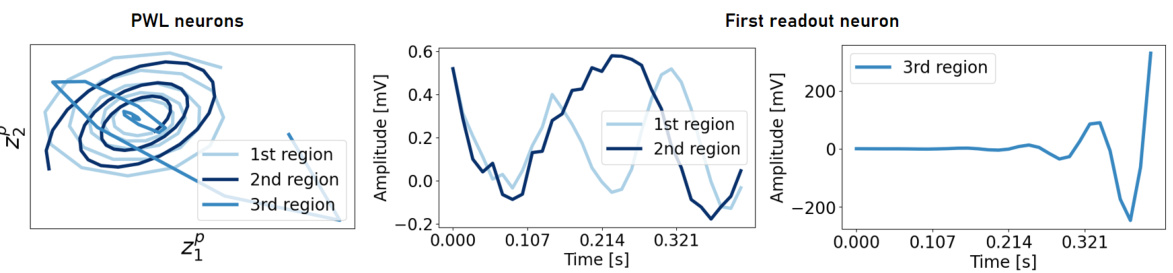

This figure shows the ’linearized’ dynamics within the three linear subregions of the AL-RNN trained on ECG data. The first two subregions show weakly unstable spirals with phase shifts representing the excitatory and inhibitory phases of the ECG. The third subregion displays strongly divergent activity that triggers the Q wave.

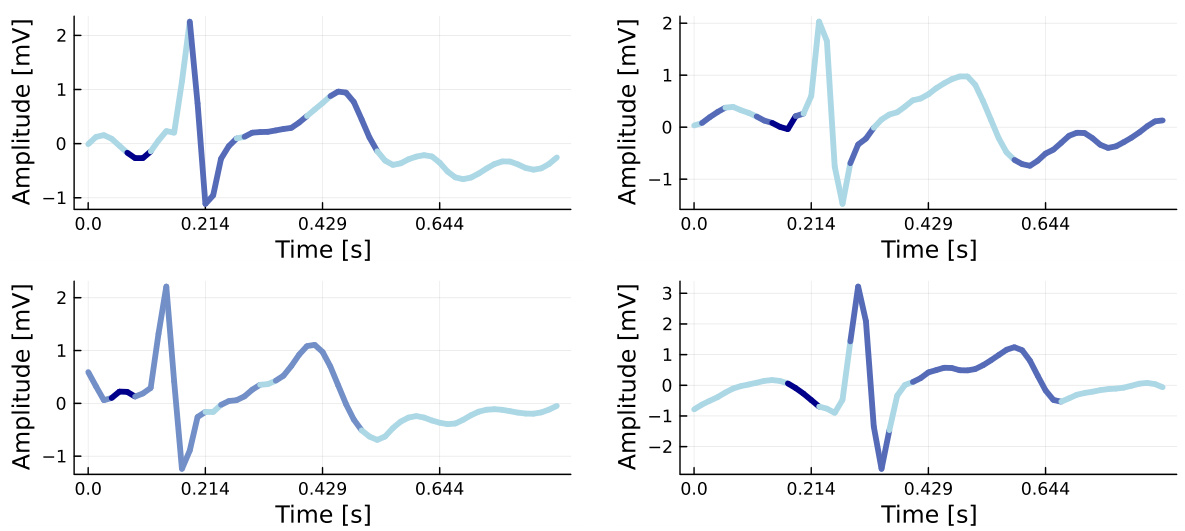

This figure shows four examples of freely generated ECG activity using an AL-RNN with three linear subregions. Each subregion is color-coded differently, and the Q wave is consistently assigned to the same subregion across the different reconstructions. This demonstrates the robustness of the AL-RNN model in capturing the critical transition initiated by the Q wave.

This figure shows the results of using an Almost-Linear Recurrent Neural Network (AL-RNN) to generate ECG activity. The AL-RNN uses three linear subregions, each represented by a different color. The Q wave, a significant feature of ECG signals, is consistently assigned to a specific subregion across multiple successful model runs. This consistency demonstrates the robustness and reliability of the AL-RNN in capturing essential features of the ECG signal.

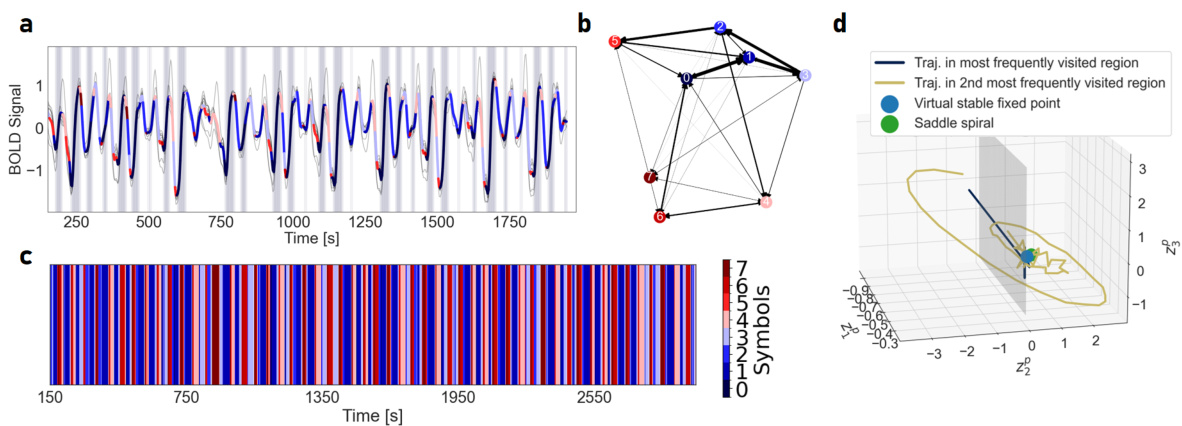

This figure shows the results of applying the AL-RNN model to fMRI data. Panel (a) displays the generated fMRI activity, color-coded by the linear subregions identified by the model. Panel (b) provides a graphical representation of the transitions between these subregions. Panel (c) shows the symbolic representation of the dynamics. Panel (d) illustrates the dynamics within the two most frequently visited subregions, highlighting the presence of a virtual stable fixed point and a saddle spiral, characteristic of chaotic systems. The overall figure demonstrates how the AL-RNN captures the complex dynamics of the fMRI data and represents them using a low-dimensional symbolic encoding.

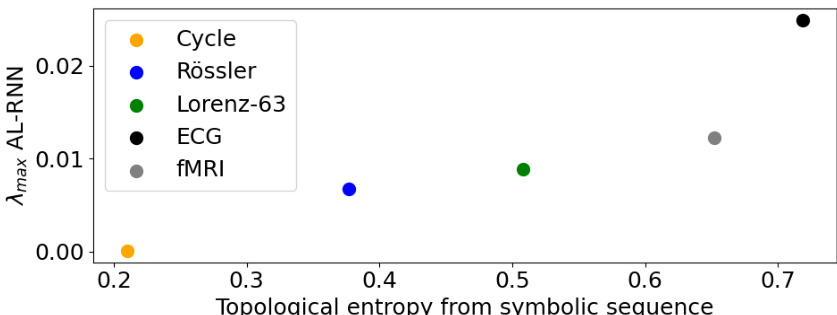

This figure shows a comparison between the topological entropy (calculated from symbolic sequences representing the dynamics of the AL-RNNs) and the maximum Lyapunov exponent (λmax). The topological entropy quantifies the complexity of the system’s dynamics, while the maximum Lyapunov exponent measures the rate of separation of nearby trajectories. The data points correspond to different systems: Rössler, Lorenz-63, ECG, and fMRI. The figure suggests that there might be a correlation between the topological entropy and the maximum Lyapunov exponent; systems with higher topological entropy tend to have higher maximum Lyapunov exponents.

This figure shows a comparison between the ground truth fMRI BOLD signal and the BOLD signal generated by an AL-RNN model. The AL-RNN used 100 total units with 2 piecewise linear (PWL) units. To help the AL-RNN learn, the readout unit states were replaced with observations every 7 time steps. The figure demonstrates the AL-RNN’s ability to generate fMRI activity that closely resembles the ground truth data, suggesting its effectiveness in modeling complex brain dynamics.

This figure shows the weights of a trained AL-RNN, broken down by unit type (readout, piecewise linear, and linear). Panel (a) visualizes the weight matrices for each unit type as heatmaps. Panel (b) provides a histogram of the absolute weight magnitudes for all units, highlighting the generally larger magnitude of the piecewise linear units. Finally, panel (c) demonstrates a high correlation (r ≈ 0.76) between the correlation matrix of the readout unit weights and the correlation matrix of the data itself.

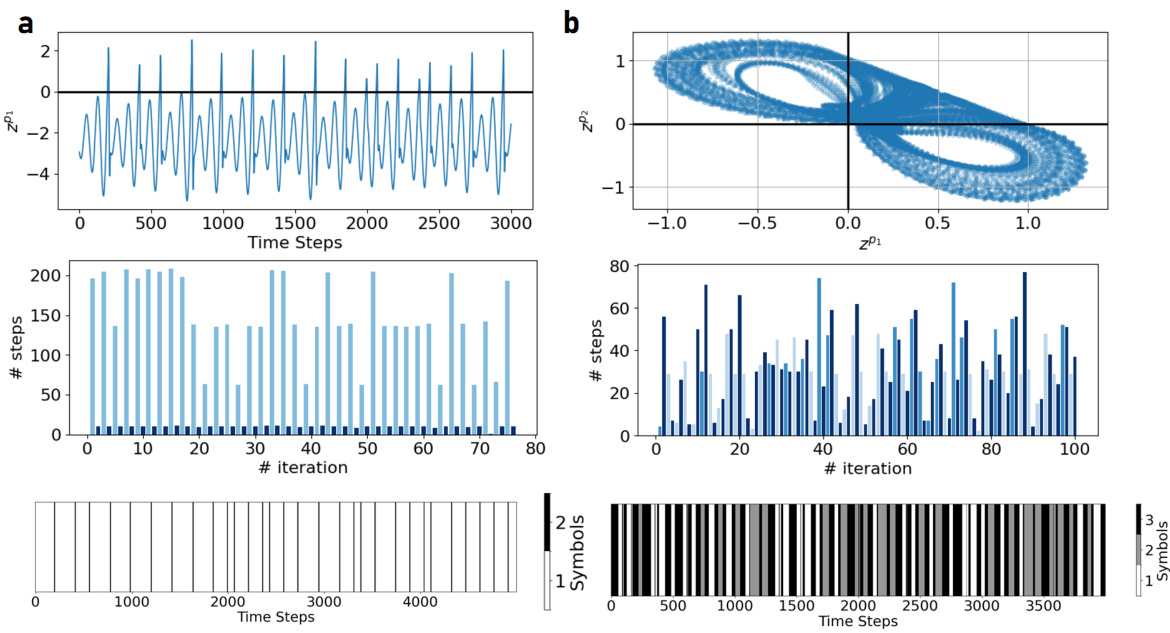

This figure shows the activity of the piecewise linear (PWL) units for the topologically minimal representations of the Rössler and Lorenz-63 attractors. The top row displays the time series of the PWL units’ activity. The center row shows the time histogram of the discrete symbols, representing the symbolic trajectory. The bottom row shows the time series of the symbolic trajectory itself. This visualization helps to understand how the minimal PWL representations capture the dynamics of these chaotic systems and how they relate to the symbolic representations.

This figure shows the effect of the number of linear units on the performance of the AL-RNN in reconstructing the Lorenz-63 system. The top panels show the results when the number of piecewise-linear (PWL) units is insufficient (P=1), while the bottom panels show the results when the number of PWL units is sufficient (P=2). The results indicate that adding more linear units does not improve performance when the number of PWL units is too small, but it can improve performance up to a certain saturation level when the number of PWL units is sufficient. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

This figure shows the results of reconstructing the Lorenz-63 attractor using an AL-RNN with 8 piecewise linear (PWL) units. The left panel displays a color-coded representation of the attractor, where color intensity corresponds to the frequency of visits to each subregion. The center panel shows a geometrical graph representation, where nodes represent subregions and edges represent transitions between them, with edge thickness representing transition frequency. The right panel shows a connectome representing the relative transition frequencies between subregions. The figure demonstrates that AL-RNNs capture the topological structure of the attractor with only a small number of PWL units.

This figure displays the performance of the AL-RNN model on four datasets (Rössler, Lorenz-63, ECG, fMRI) as the number of piecewise linear (PWL) units increases. The performance metrics used are the Kullback-Leibler divergence (Dstsp) for geometric agreement between the reconstructed and true attractors and the Hellinger distance (DH) for temporal agreement (comparing power spectra). The graphs show that performance generally improves with more PWL units, particularly for the Lorenz-63, suggesting the importance of a sufficient number of PWL units for accurate representation. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

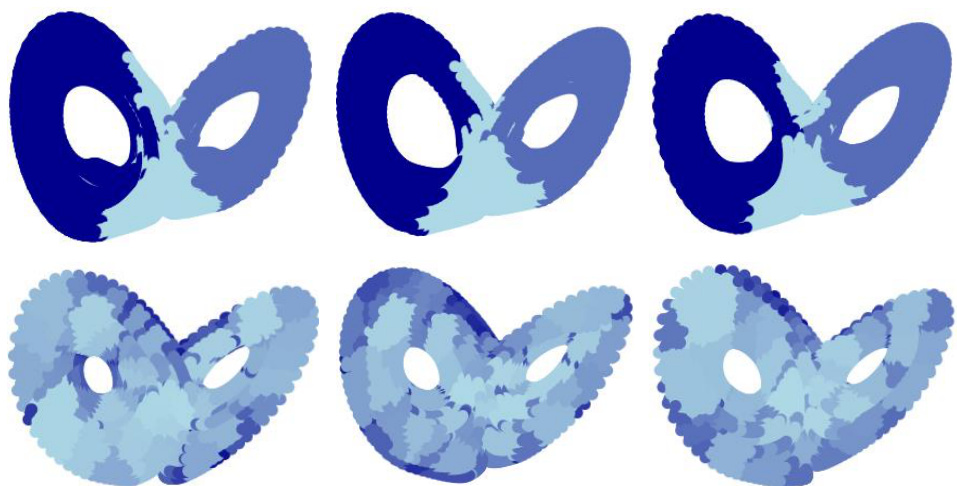

This figure compares the consistency of the AL-RNN and PLRNN models across multiple training runs. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic was used to quantify the differences between cumulative trajectory point distributions in different linear subregions. The results demonstrate that AL-RNN exhibits substantially higher consistency across training runs compared to PLRNN.

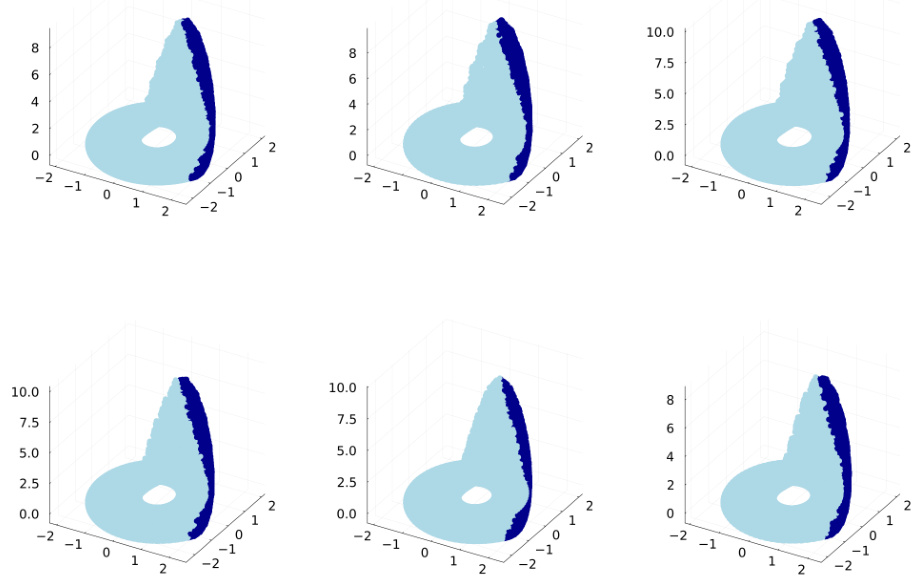

This figure shows the minimal piecewise linear (PWL) representation of the Rössler and Lorenz attractors discovered by AL-RNNs. It illustrates how the AL-RNN captures chaotic dynamics using only a few linear subregions, and the topological and geometrical agreement of this representation with known minimal PWL designs. The figure also displays the symbolic coding of these dynamics and shows the robustness of this minimal representation across multiple training runs.

The figure shows the robustness of the AL-RNN in assigning linear subregions to the observation space across multiple training runs. The top row displays AL-RNN results, demonstrating consistent subregion placement. The bottom row contrasts this with PLRNN results, showing inconsistent subregion assignments across runs.

Full paper#