↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing on-the-fly category discovery methods struggle with accurately classifying fine-grained categories due to the ‘high sensitivity’ issue arising from directly mapping high-dimensional features into low-dimensional hash space. This often leads to misclassifications, especially when dealing with subtle inter-class variations. The challenge is further compounded by the need for real-time feedback, making offline methods impractical.

To overcome these limitations, this paper introduces Prototypical Hash Encoding (PHE), a novel framework that leverages multiple prototypes per category to capture intra-class diversity. PHE consists of two stages: Category-aware Prototype Generation (CPG) and Discriminative Category Encoding (DCE). CPG generates category-specific prototypes, while DCE encodes them as hash centers to generate discriminative hash codes. Extensive experiments demonstrate PHE’s significant performance improvements over existing methods across various fine-grained datasets, showcasing its effectiveness in addressing the ‘high sensitivity’ issue and improving overall accuracy.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it tackles the challenging problem of on-the-fly fine-grained category discovery, a crucial task for real-world applications dealing with streaming data and evolving categories. Its proposed solution, using prototypical hash encoding, offers significant improvements in accuracy and efficiency, especially relevant in scenarios with high dimensionality and subtle inter-class variations. The findings open avenues for research into more robust and scalable category discovery methods.

Visual Insights#

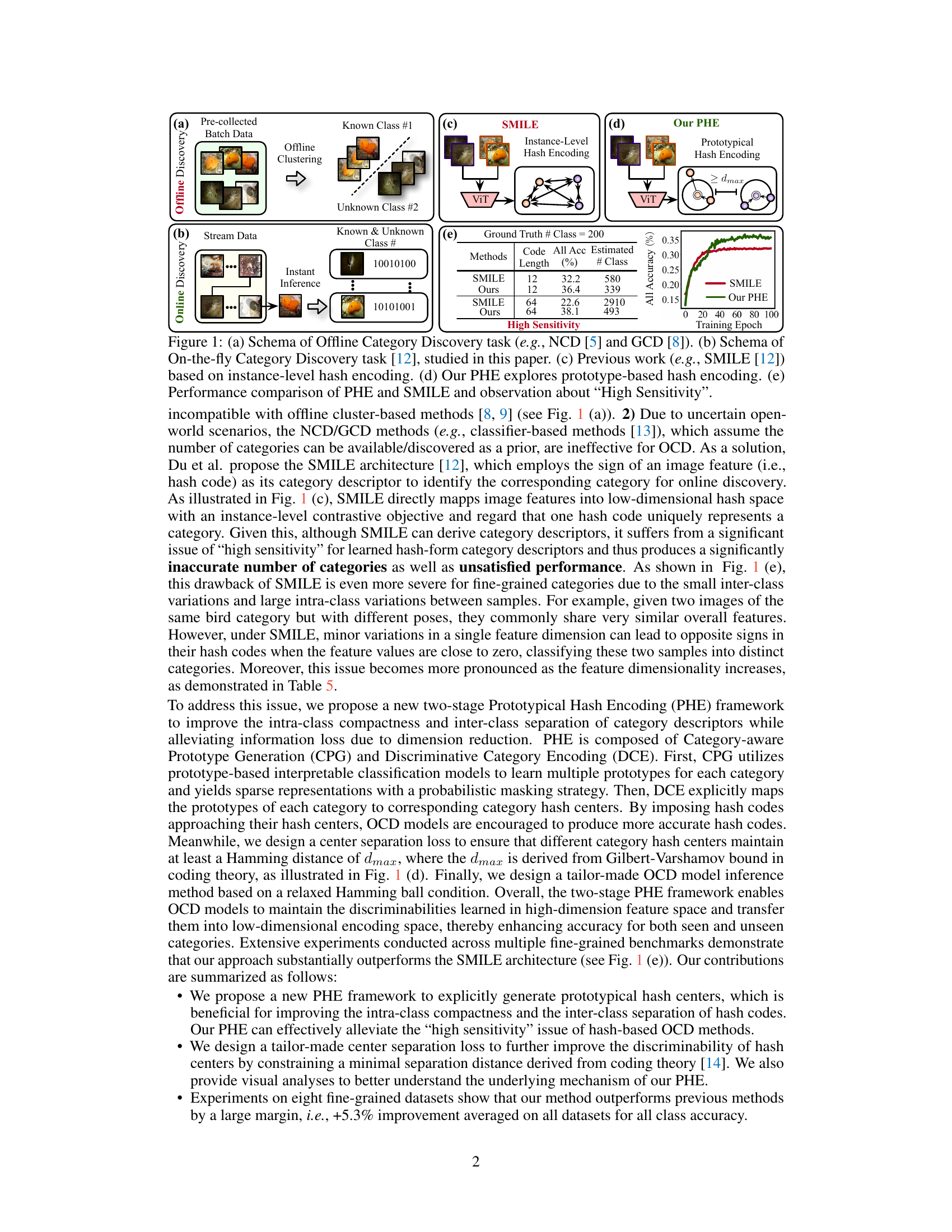

This figure illustrates the difference between offline and online category discovery. (a) and (b) show the schematic of Offline and Online Category Discovery, respectively. (c) shows the SMILE method’s instance-level hash encoding approach. In contrast, (d) presents the proposed PHE method utilizing prototype-based hash encoding. (e) compares the performance of PHE and SMILE, highlighting SMILE’s high sensitivity issue, particularly in fine-grained scenarios.

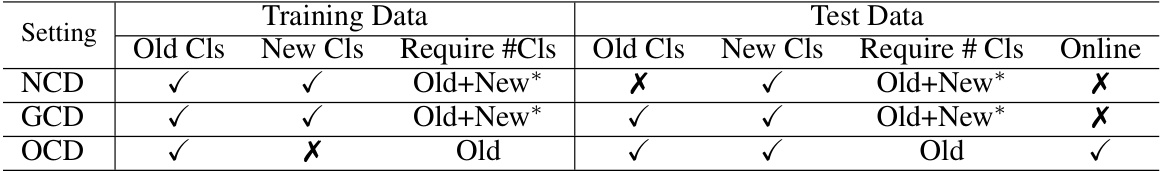

The table compares three different settings for category discovery: Novel Category Discovery (NCD), Generalized Category Discovery (GCD), and On-the-fly Category Discovery (OCD). It shows whether the training data includes samples from old and/or new categories, whether the test data includes samples from old and/or new categories, whether the number of new classes needs to be known a priori, and whether the setting requires online inference. The OCD setting is unique in that it only uses old categories in training and does not require the number of new classes to be known beforehand, with the need for online feedback during inference.

In-depth insights#

Prototypical Hashing#

Prototypical hashing is a technique that leverages the power of prototypes to improve the accuracy and efficiency of hashing. Instead of directly mapping data points to hash codes, prototypical hashing first generates representative prototypes for each category or cluster. These prototypes capture the essential characteristics of their respective groups. Subsequently, data points are mapped to hash codes based on their similarity to these prototypes. This approach offers several advantages. First, it reduces the sensitivity to noise and minor variations within a category, as the mapping relies on the overall representation of the prototype rather than individual feature values. Second, it improves the discriminative power of the hash codes, as prototypes are designed to be well-separated in the feature space. Third, prototypical hashing provides a degree of interpretability, as the prototypes themselves can be analyzed to understand the underlying structure of the data and how categories are defined. However, generating effective prototypes can be computationally expensive and require careful design of the prototype generation process. Furthermore, the effectiveness of prototypical hashing heavily relies on the quality of the prototypes; poorly chosen prototypes can lead to poor hashing performance. The choice of distance metric for comparing data points to prototypes also significantly affects the performance.

Fine-Grained OCD#

Fine-grained On-the-fly Category Discovery (OCD) presents a unique challenge in machine learning, demanding the ability to identify and classify new categories from a continuous stream of data, especially when those categories exhibit subtle differences. Existing OCD methods often struggle in fine-grained scenarios due to high sensitivity in hash-based techniques. This means small variations in input data can lead to drastically different classifications. To address this, novel approaches that incorporate techniques like prototype-based representations are crucial. By representing each category with multiple prototypes that encapsulate intra-class variations, these methods can mitigate the sensitivity issue and improve the accuracy of classifying fine-grained data. Furthermore, developing discriminative encoding techniques that maintain large separation distances between category prototypes in the hash space is key to resolving the challenges of fine-grained OCD. This approach emphasizes the need for methods that are not only efficient in processing data streams, but also robust enough to handle the complexities inherent in distinguishing subtle differences between fine-grained categories.

PHE Framework#

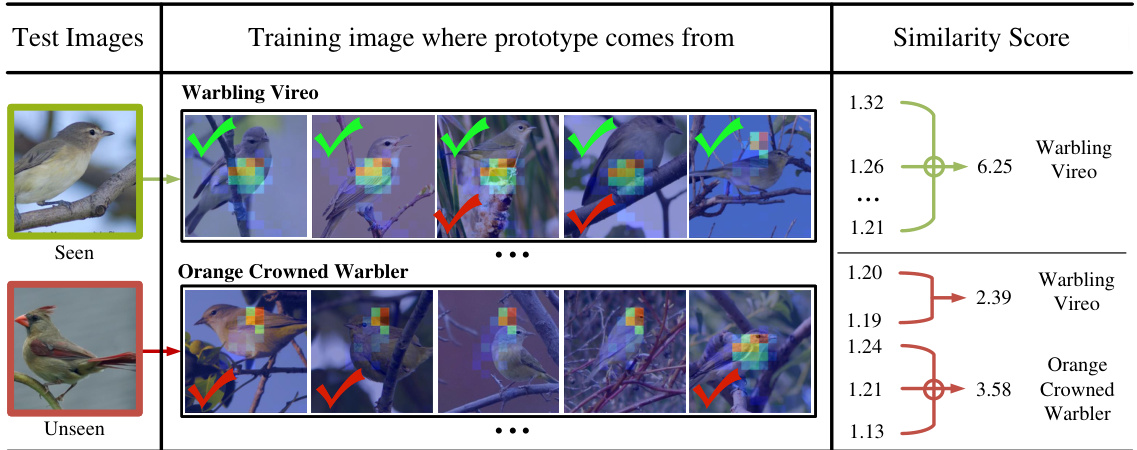

The Prototypical Hash Encoding (PHE) framework represents a novel approach to on-the-fly fine-grained category discovery. Its two-stage design, encompassing Category-aware Prototype Generation (CPG) and Discriminative Category Encoding (DCE), directly addresses the limitations of prior hash-based methods. CPG cleverly generates multiple prototypes per category, capturing intra-class diversity and enabling more robust representation, especially beneficial for fine-grained classes. DCE, using these prototypes, optimizes discriminative hash codes, ensuring maximum separation between categories. The joint optimization of CPG and DCE is crucial, demonstrating a synergistic relationship in improving overall accuracy. The framework’s utilization of Hamming balls further enhances the robustness of the approach by mitigating the “high sensitivity” issue present in direct hash mapping. This is a significant advance, enabling more reliable identification of both known and novel categories in real-time. The framework’s interpretable prototypes allow for insightful visual analysis, providing further understanding of the model’s decision-making process. This aspect is particularly valuable in fine-grained categorization where subtle differences are crucial for accurate identification.

Sensitivity Issue#

The “sensitivity issue” in high-dimensional hash-based category discovery methods arises from the fragility of low-dimensional hash codes in representing high-dimensional data. A small change in the input feature vector can lead to a large change in the hash code, resulting in misclassification, especially pronounced in fine-grained categories with subtle differences. This sensitivity stems from the loss of information inherent in dimensionality reduction; crucial distinguishing features might be lost, leading to hash collisions and inaccurate assignments. Directly mapping features into a low-dimensional hash space without addressing this information loss results in poor performance. Therefore, innovative approaches are needed to mitigate this problem, such as employing more robust encoding techniques that preserve discriminative information or using methods that are less sensitive to small perturbations in the input space. The effectiveness of any solution hinges on its ability to balance dimensionality reduction with the retention of crucial discriminative information.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this prototypical hash encoding (PHE) framework for on-the-fly fine-grained category discovery could involve several key areas. Improving robustness to noisy or incomplete data is crucial, as real-world data often deviates from ideal conditions. Exploring alternative prototype generation methods, such as those leveraging unsupervised or semi-supervised learning, could enhance the model’s ability to learn meaningful representations with limited labeled data. Investigating the use of larger and more diverse datasets would validate PHE’s generalization capability across a broader range of fine-grained categories. Furthermore, in-depth analysis of the Hamming distance and its influence on classification accuracy merits further study, potentially leading to more efficient and accurate hash-based encoding techniques. The interplay between hash code length and classification performance remains an open question, requiring deeper investigation. Finally, exploring the integration of external knowledge sources, such as semantic knowledge bases or visual ontologies, could enhance the model’s understanding of category relationships and improve its ability to discover novel categories effectively.

More visual insights#

More on figures

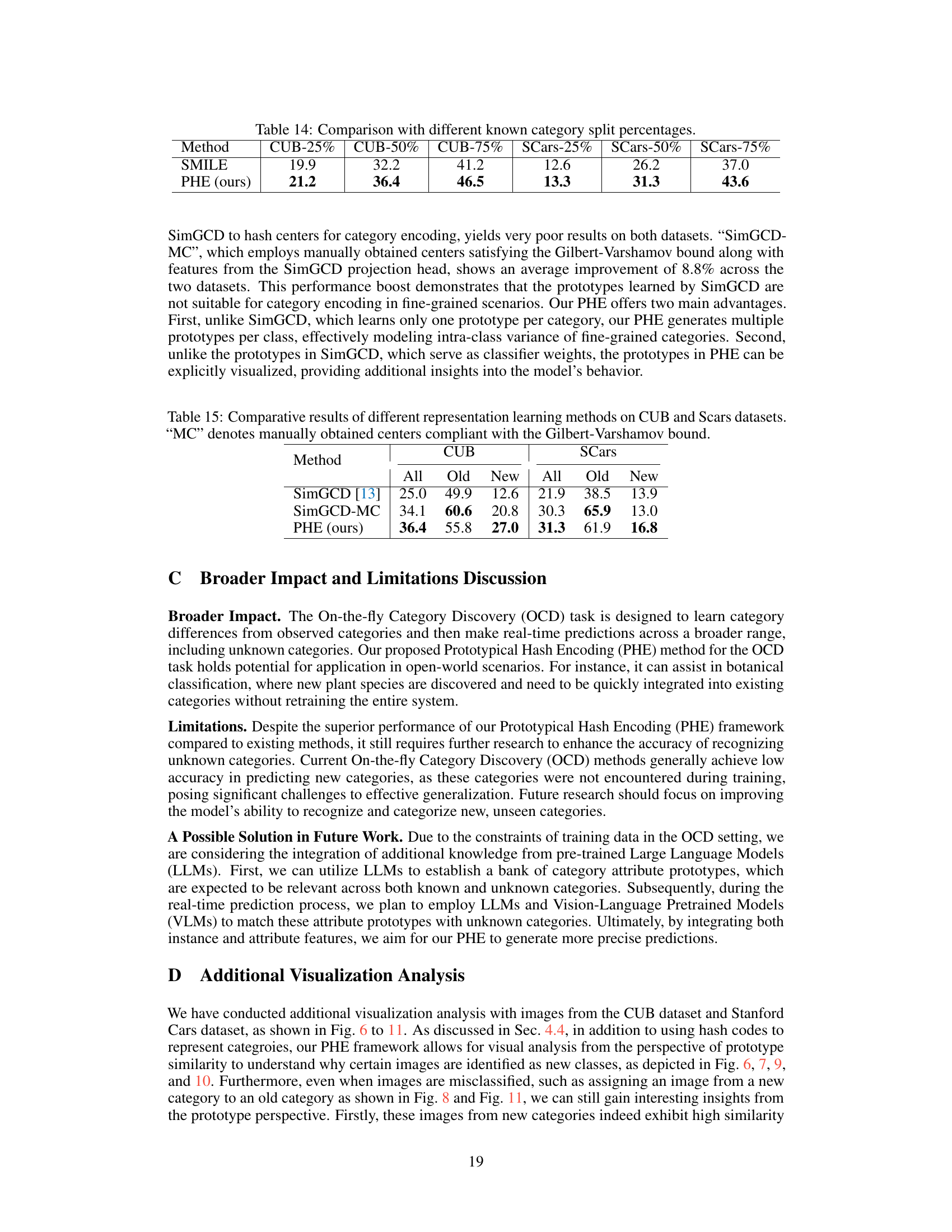

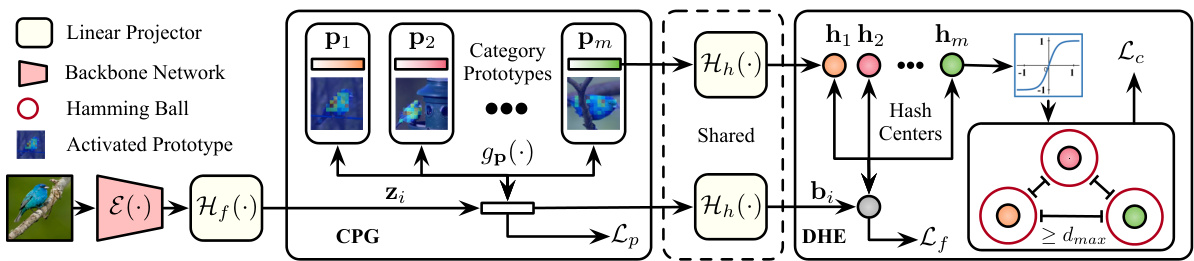

This figure illustrates the proposed Prototypical Hash Encoding (PHE) framework, which consists of two main modules: Category-aware Prototype Generation (CPG) and Discriminative Hash Encoding (DHE). The CPG module generates category-specific prototypes and their corresponding instance representations. These prototypes are then encoded as hash centers by the DHE module, which aims to learn discriminative instance hash codes. The Hamming distance between the instance hash codes and hash centers determines whether the instance belongs to a known or unknown category, enabling on-the-fly category discovery and online feedback.

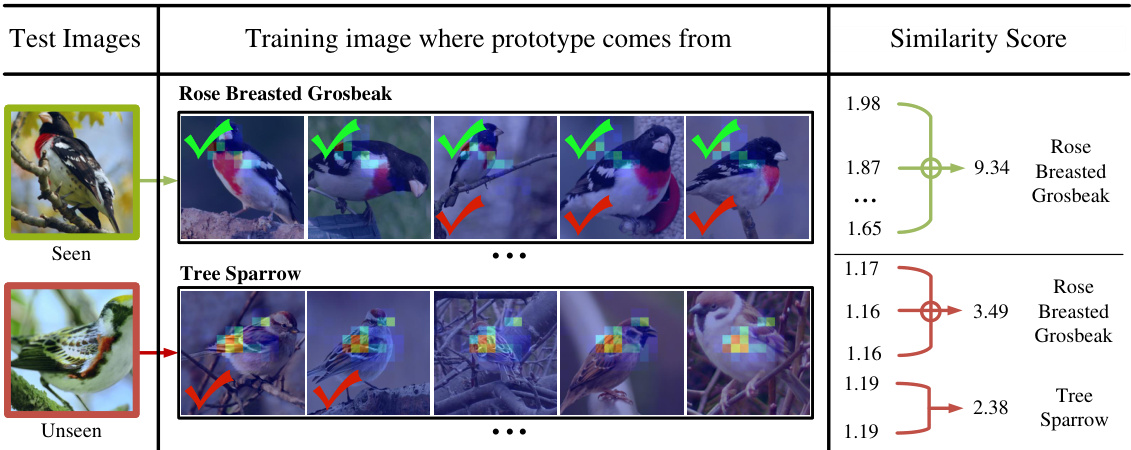

This figure provides a case study illustrating how the PHE model classifies a Grasshopper Sparrow as a new category. It visually demonstrates the similarity scores between the test image and the prototypes of known categories. The high similarity to multiple known categories, rather than a single one, leads to its classification as a new category, showcasing the model’s ability to handle unseen categories.

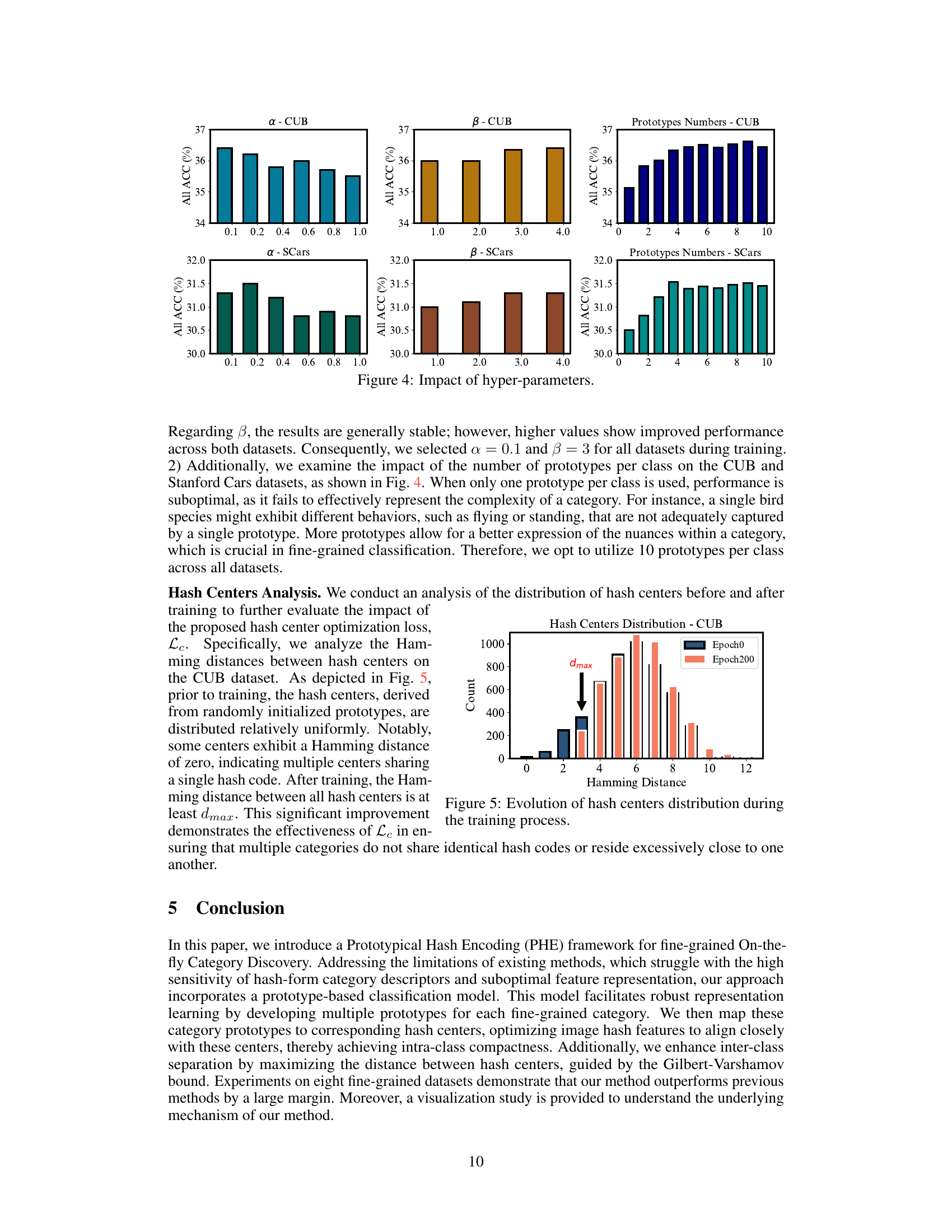

This figure shows the impact of hyperparameters α and β on the overall accuracy of the model, as well as the impact of the number of prototypes per class. The left two plots show that α should be kept relatively small and that β should be relatively large for optimal performance. The rightmost plot demonstrates that using more than a single prototype per class significantly improves performance.

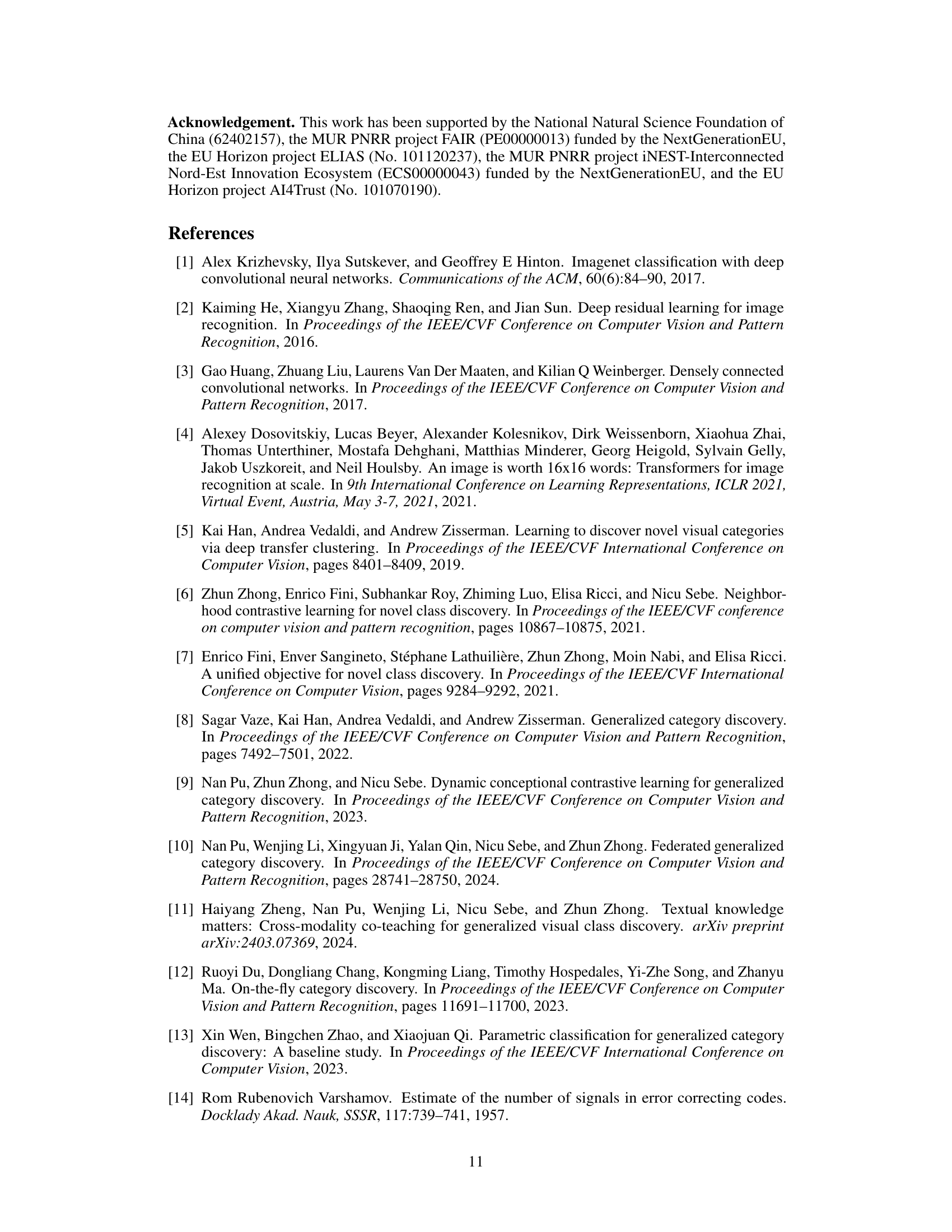

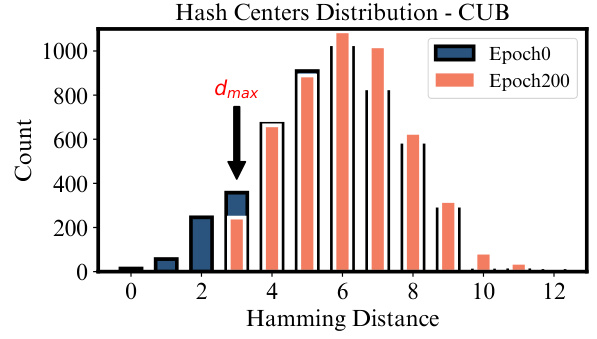

This figure shows the distribution of Hamming distances between hash centers before training (Epoch0) and after training (Epoch200) on the CUB dataset. Before training, the hash centers are distributed relatively uniformly, with some centers having a Hamming distance of zero (meaning multiple centers share the same hash code). After training, the Hamming distance between all hash centers is at least dmax, demonstrating the effectiveness of the center separation loss in ensuring that multiple categories do not share identical hash codes or reside excessively close to one another.

This figure shows a case study of how the PHE model classifies a Grasshopper Sparrow, which was not in the training set, as a new category. It visualizes the similarity scores between the test image and prototypes from known categories. The high similarity scores to multiple known categories, rather than a single category, suggest the reason for classifying it as new.

This figure provides a case study illustrating how the PHE framework classifies a Grasshopper Sparrow as a new category. It shows the similarity scores between the test image (Grasshopper Sparrow) and the prototypes of known categories (Le Conte Sparrow and Horned Lark). The high similarity scores to multiple known categories indicate that the model correctly identifies the Grasshopper Sparrow as a new category because it shares visual features with multiple known categories.

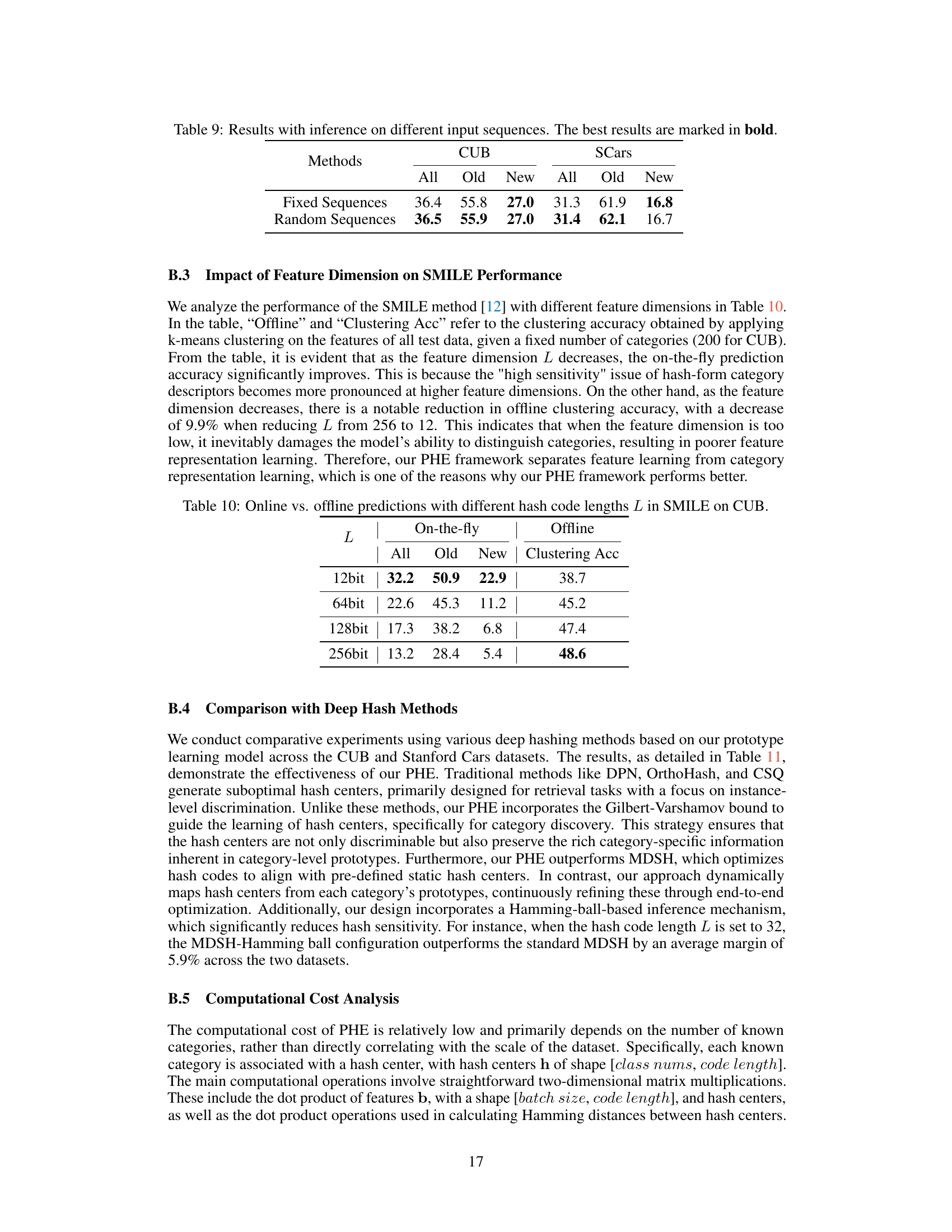

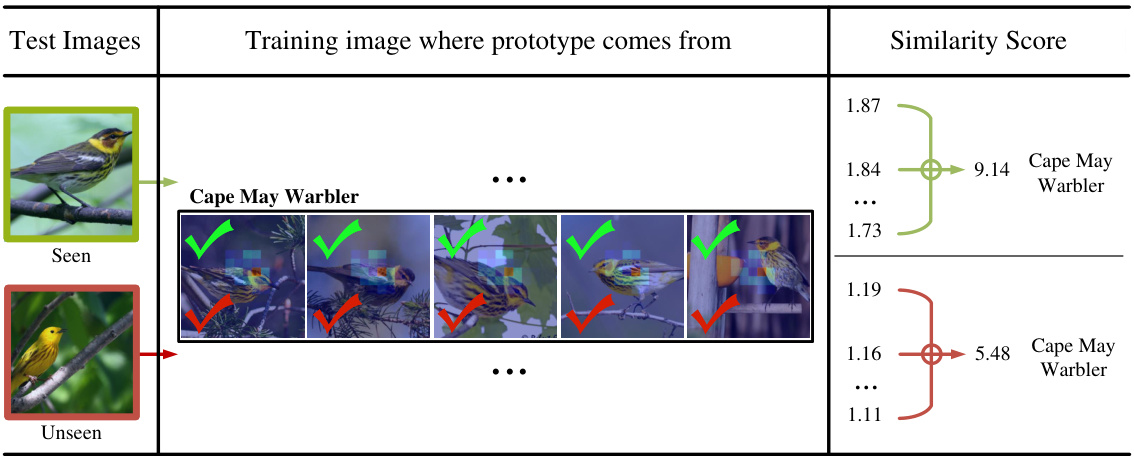

This figure presents a case study to illustrate how the PHE model classifies images. It shows the similarity scores between test images (a Yellow Warbler and a Cape May Warbler) and the prototypes generated for known categories. The Yellow Warbler, which belongs to an unseen category, shows higher similarity scores to the Cape May Warbler prototypes than to the prototypes of other known categories. This indicates that the model identifies the subtle differences between similar species, facilitating the discovery of novel categories.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed Prototypical Hash Encoding (PHE) framework. It consists of two main modules: Category-aware Prototype Generation (CPG) and Discriminative Hash Encoding (DHE). CPG generates category prototypes and instance representations, while DHE maps these prototypes to hash centers. The Hamming distance between instance hash codes and these centers determines category assignment (known or unknown).

This figure compares the proposed Prototypical Hash Encoding (PHE) method with the SMILE method for on-the-fly category discovery. It shows the schemas of offline and online category discovery, illustrating the differences in data handling and inference. It highlights the ‘high sensitivity’ issue of SMILE, especially for fine-grained categories, and demonstrates the improvement achieved by PHE in terms of accuracy.

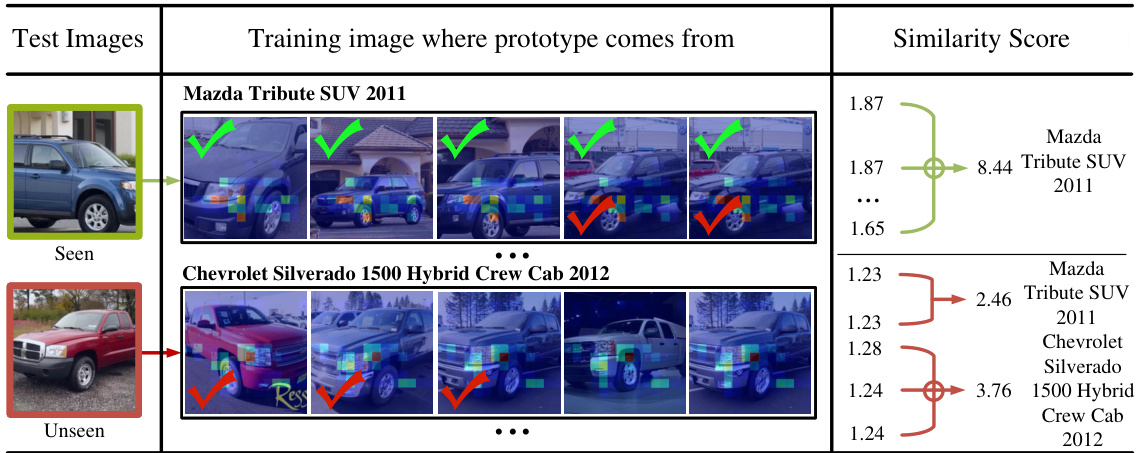

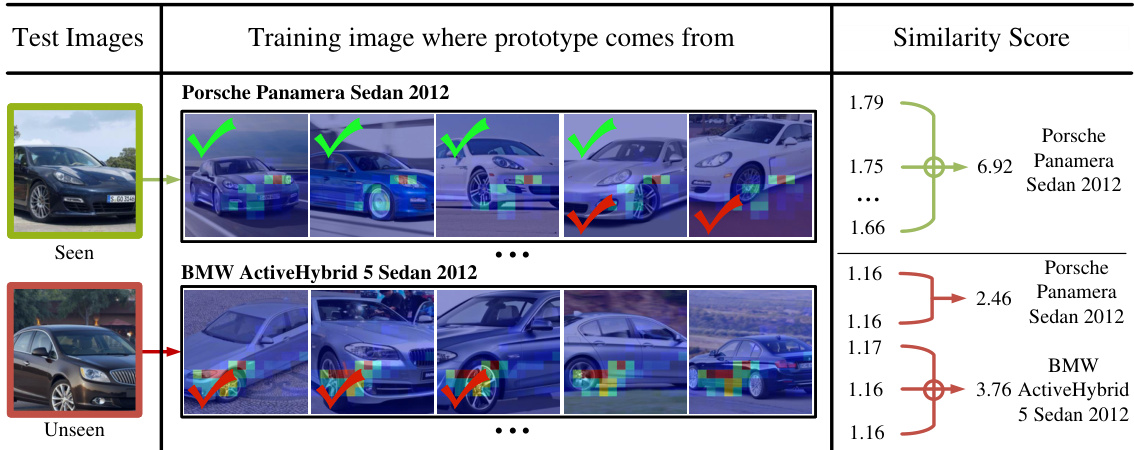

This figure shows a case study comparing a Dodge Challenger SRT8 2011 (unseen) and a Volvo C30 Hatchback 2012 (seen). It visualizes the similarity scores between the test images and the prototypes of the known categories. The high similarity score between the unseen image and the prototypes of the Volvo C30 Hatchback 2012 category suggests the model’s ability to associate similar features across different car models. This example is presented to illustrate how the PHE helps group certain samples into known or unknown categories based on the similarity between prototypes and their feature vectors.

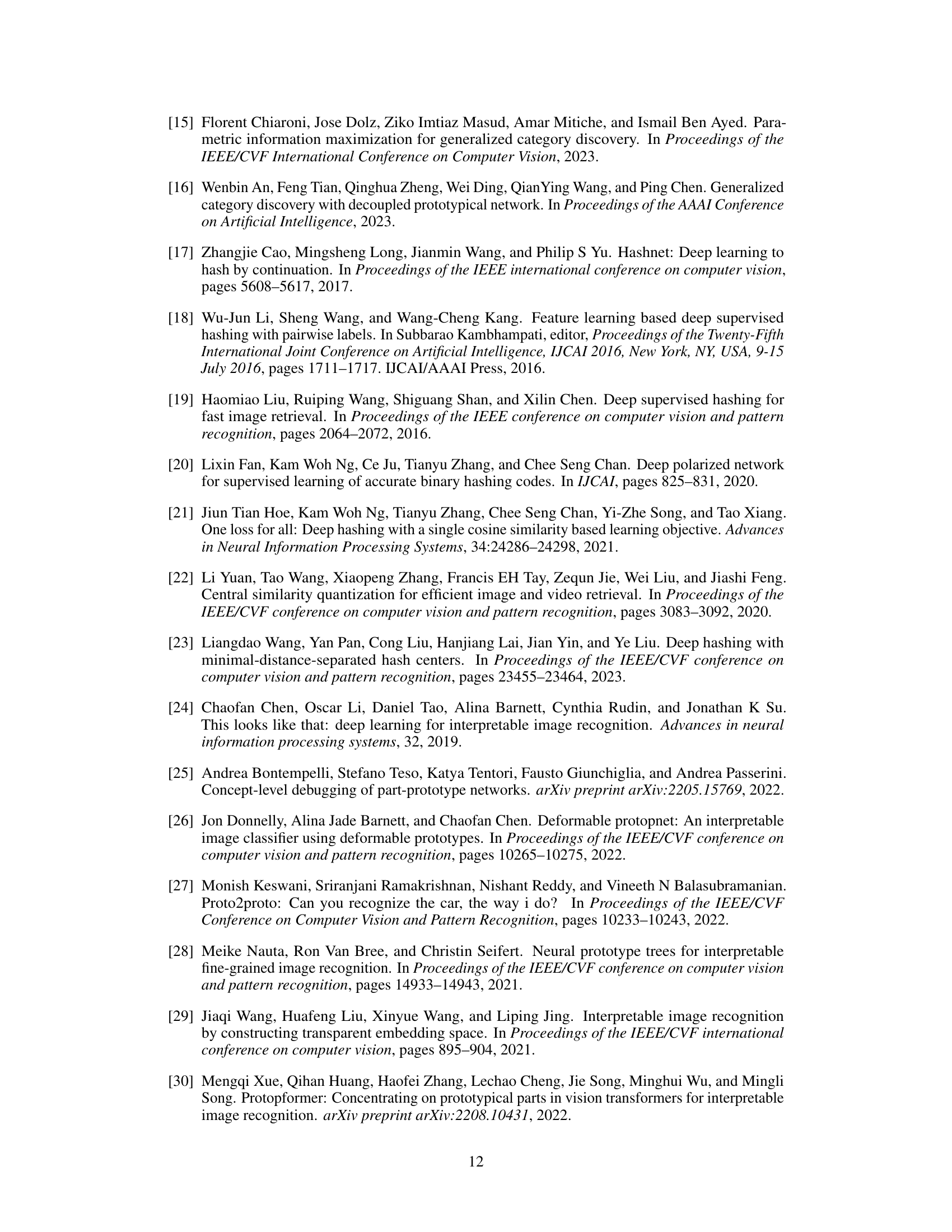

More on tables

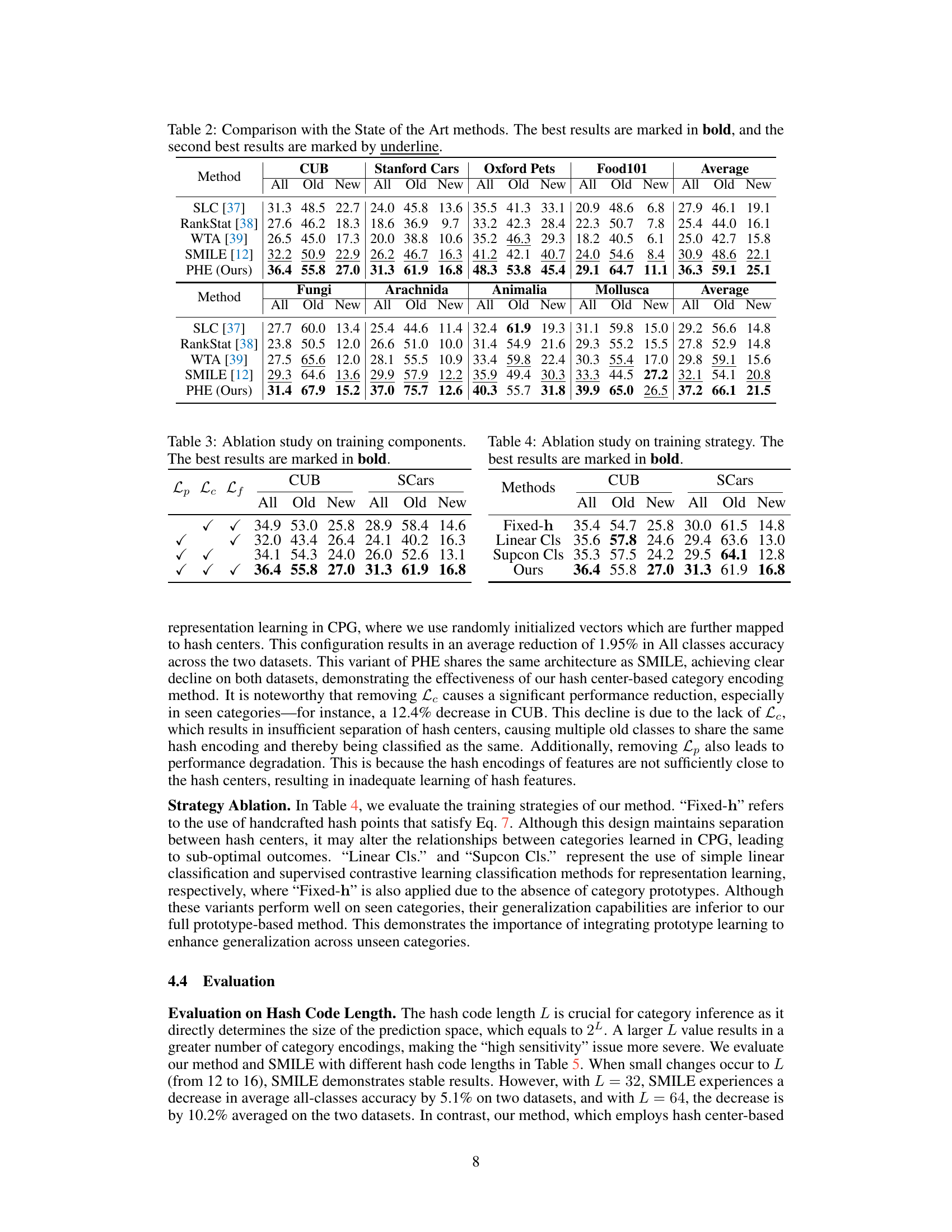

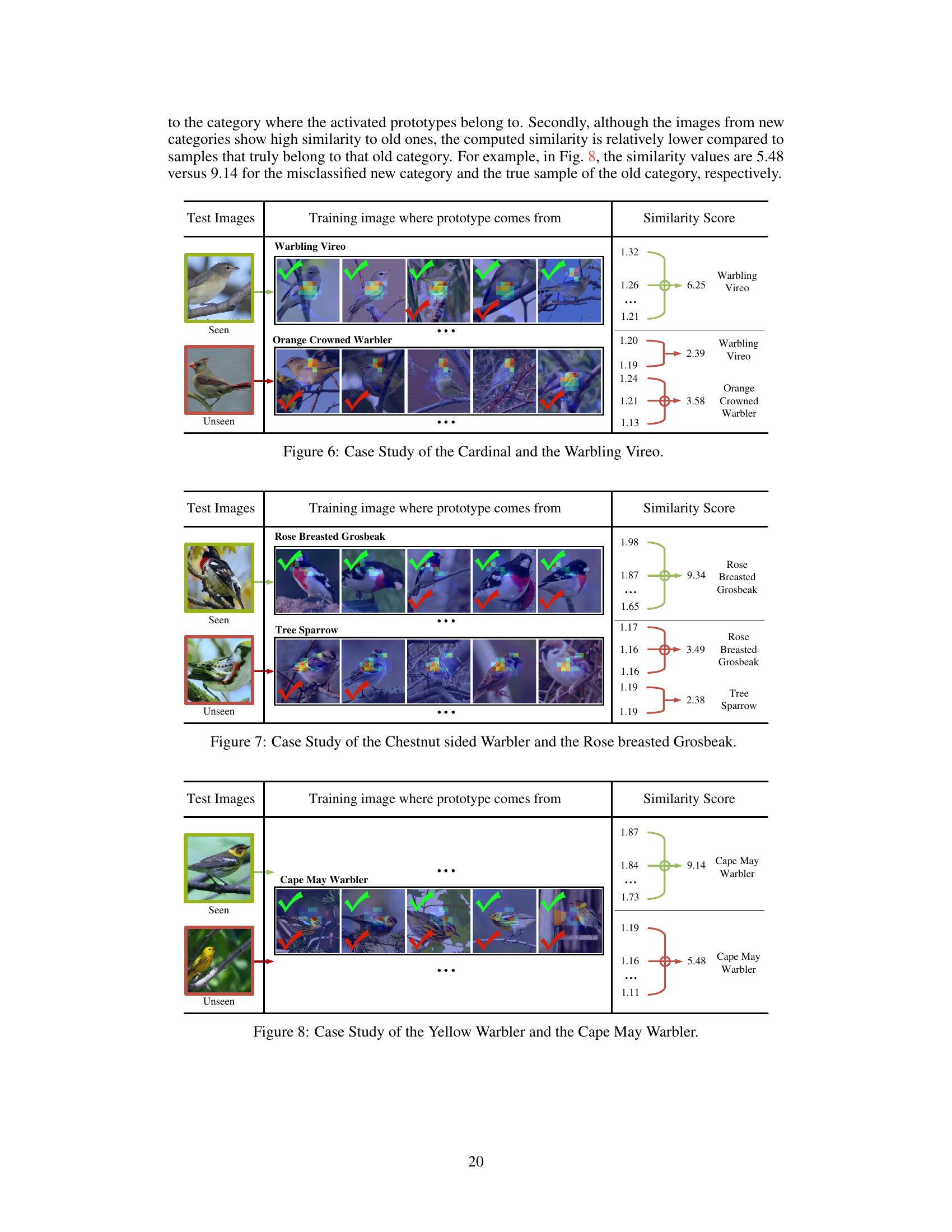

This table presents a comparison of the proposed PHE method against several state-of-the-art methods for on-the-fly category discovery across eight fine-grained datasets. For each dataset and each method, the table shows the ‘All’, ‘Old’, and ‘New’ class accuracies. ‘All’ refers to the overall accuracy, ‘Old’ refers to the accuracy on known categories, and ‘New’ represents the accuracy on newly discovered categories. The best results for each metric are highlighted in bold, while the second-best results are underlined. The average accuracy across all datasets is also provided for each method.

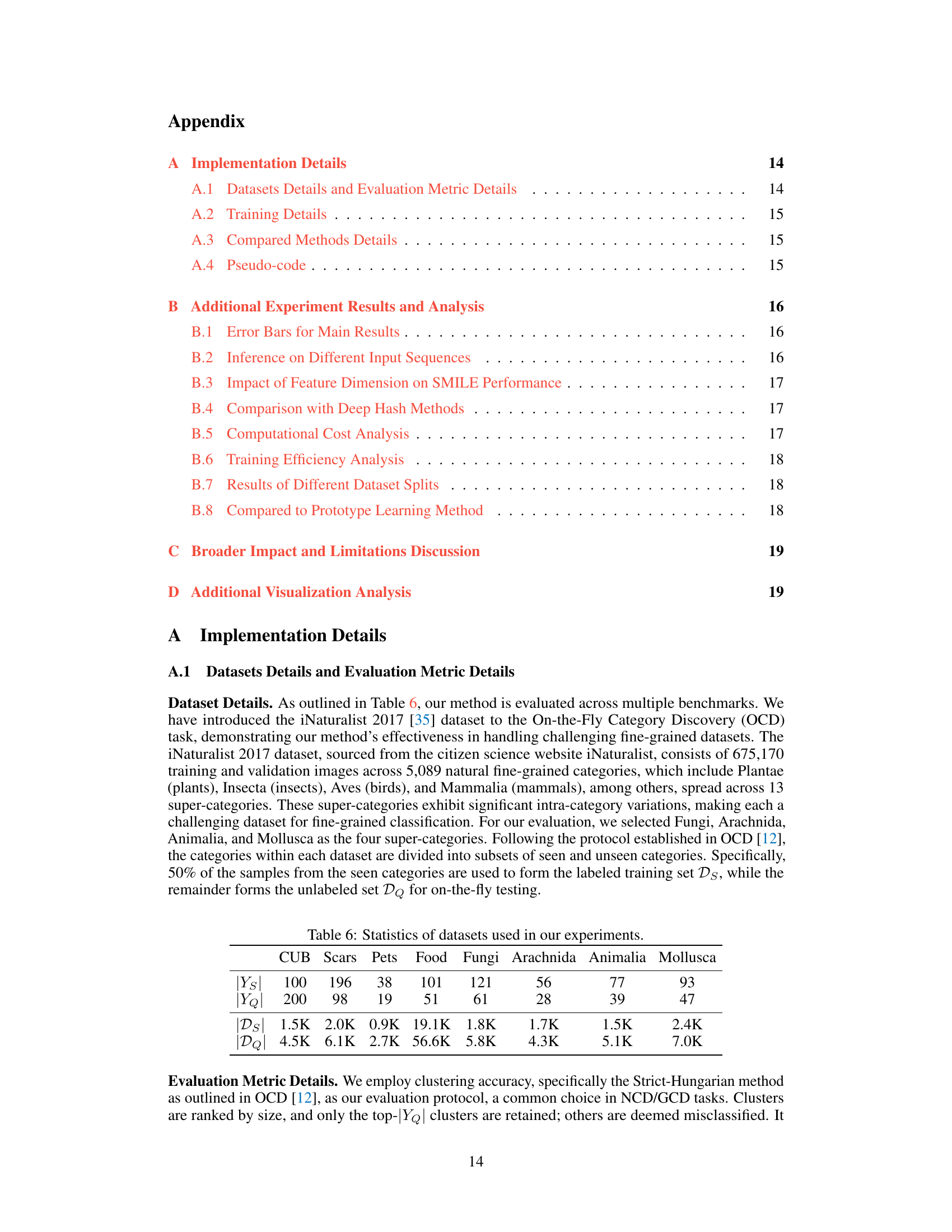

This table presents the ablation study results focusing on the three loss functions used in the Prototypical Hash Encoding (PHE) framework: Lp (prototype generation loss), Lc (category encoding loss), and Lf (hash feature loss). The table shows the performance results for CUB and SCars datasets in terms of overall accuracy (All), accuracy on known categories (Old), and accuracy on new categories (New). Each row represents a different combination of the three loss functions, indicating which were used and which were excluded during training. The results demonstrate the importance of each loss function in achieving optimal performance.

This table presents the ablation study on different training strategies used in the Prototypical Hash Encoding (PHE) framework. It shows the performance of the model with various components removed or modified: 1) using fixed-h (handcrafted hash points); 2) using only linear classification; 3) using supervised contrastive learning classification; and 4) the full PHE model (Ours). The results are presented in terms of overall accuracy (All), accuracy for known categories (Old), and accuracy for new categories (New), on CUB and SCars datasets. The goal is to demonstrate the contribution of each component to the overall performance of the model.

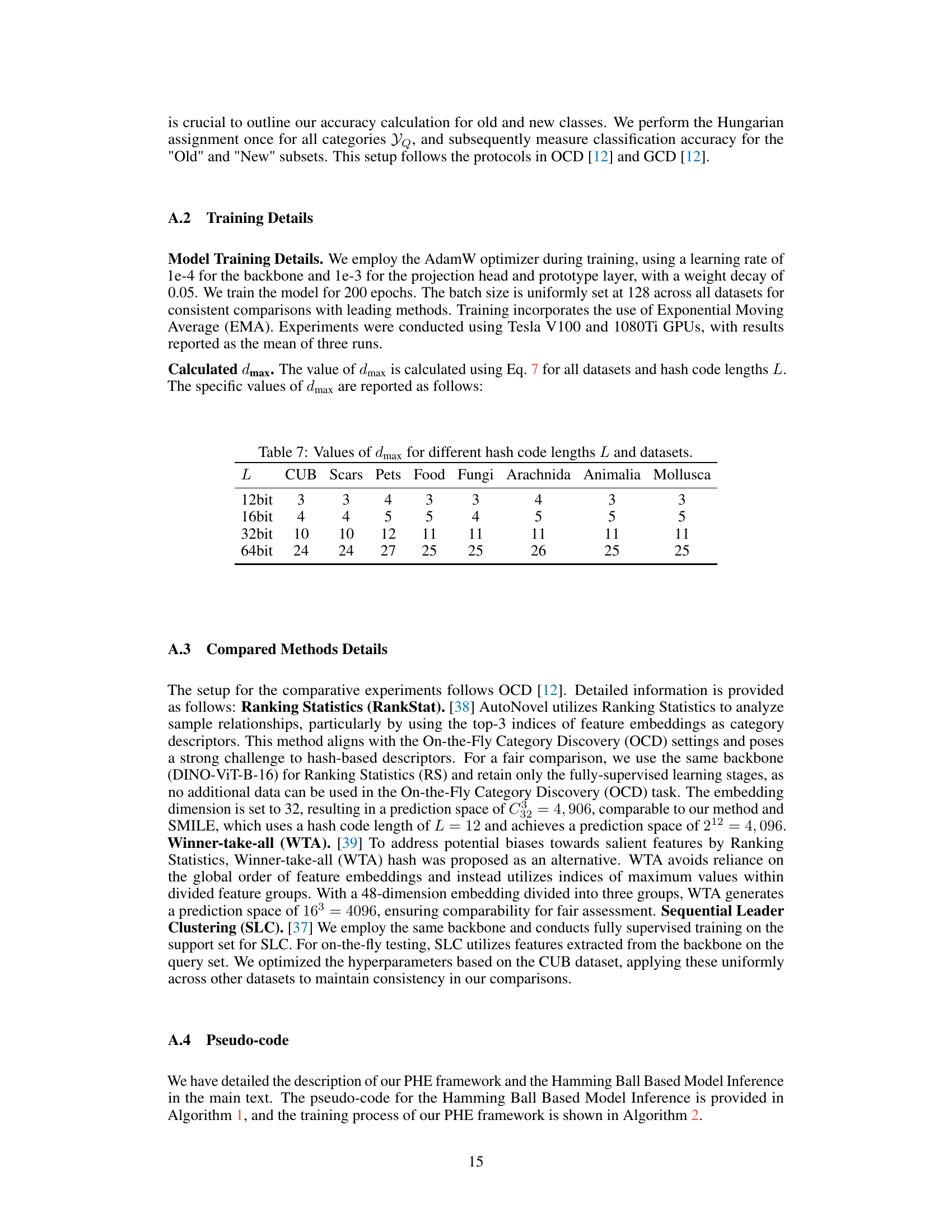

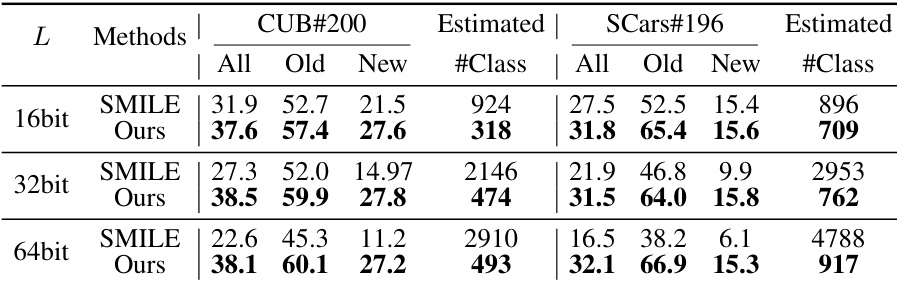

This table presents the performance comparison of SMILE and PHE methods with varying hash code lengths (L). The results are shown for CUB-200 and SCars-196 datasets, including overall accuracy, accuracy on old and new categories, and the estimated number of categories. The table highlights the impact of hash code length on the performance of both methods, especially SMILE, which shows a significant decrease in accuracy as the hash code length increases. PHE demonstrates more stability across different hash code lengths.

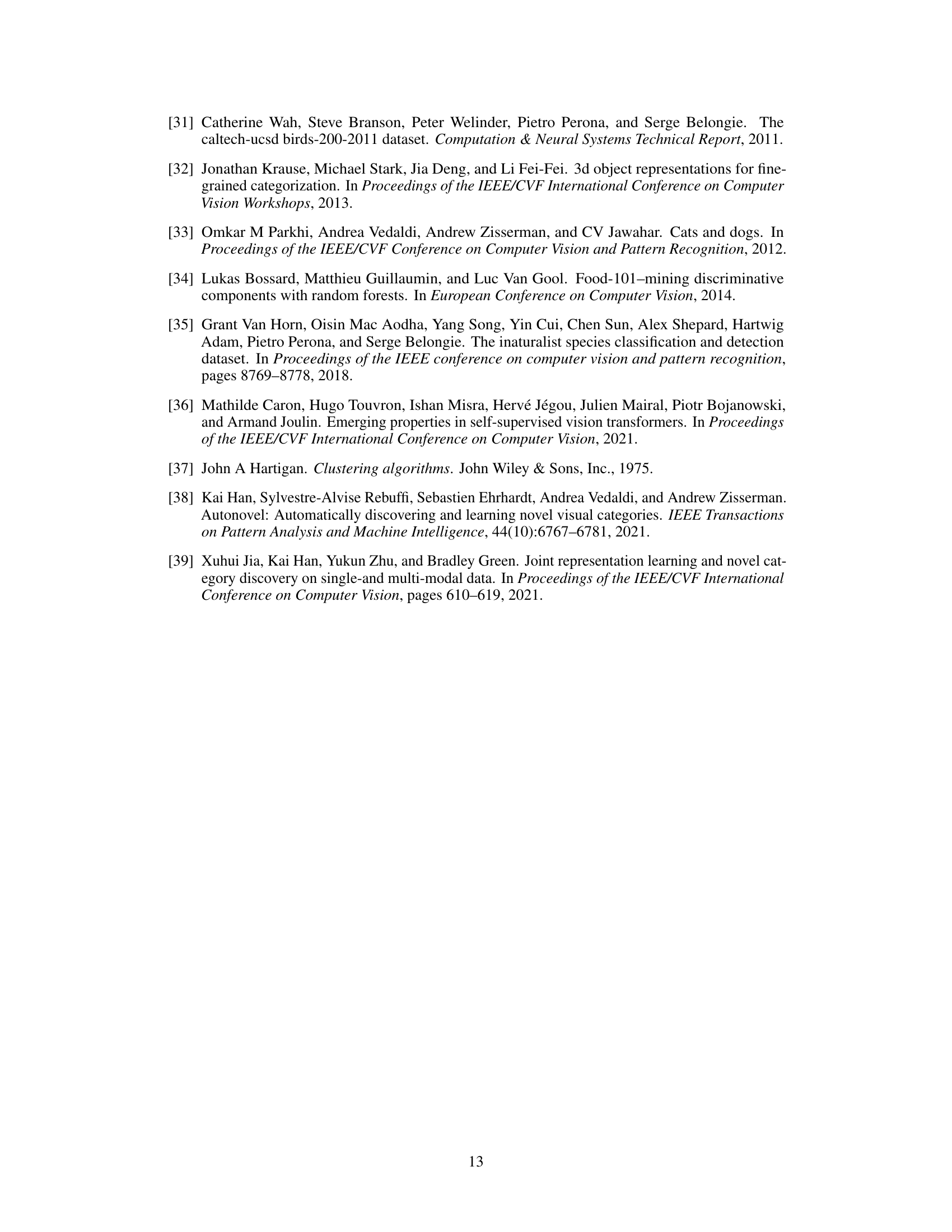

This table presents the statistics of eight datasets used in the experiments. For each dataset, it shows the number of seen classes (|Ys|), the number of seen and unseen classes (|YQ|), the number of samples in the training set (|Ds|), and the number of samples in the testing set (|DQ|). The datasets include CUB-200, Stanford Cars, Oxford-IIIT Pet, Food-101, and four sub-categories from iNaturalist (Fungi, Arachnida, Animalia, and Mollusca).

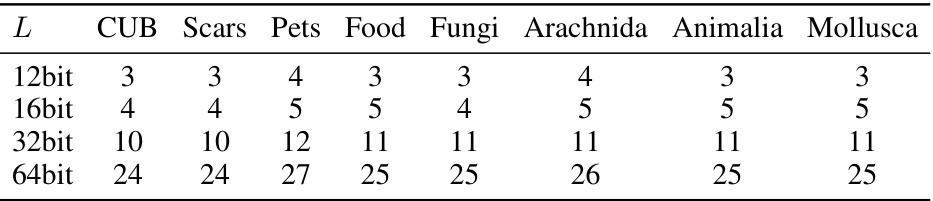

This table shows the calculated values of the maximum Hamming distance (dmax) between hash centers for different hash code lengths (L=12, 16, 32, 64 bits) and eight datasets (CUB, Stanford Cars, Oxford Pets, Food-101, Fungi, Arachnida, Animalia, Mollusca). The dmax values are determined using the Gilbert-Varshamov bound, ensuring sufficient separation between hash centers for effective category discrimination. These values are crucial hyperparameters in the Discriminative Hash Encoding (DHE) module of the Prototypical Hash Encoding (PHE) framework, influencing the training process and the overall performance of the OCD task.

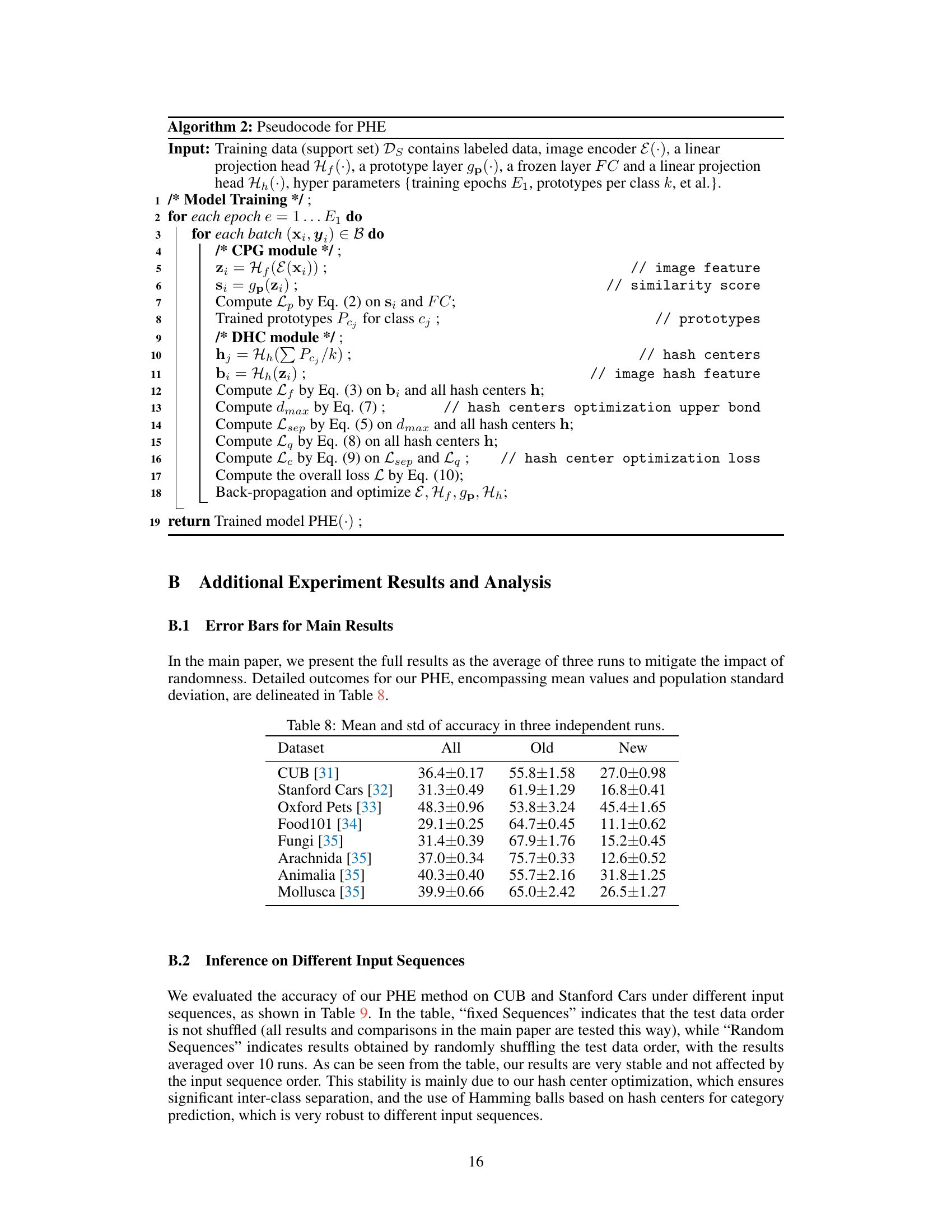

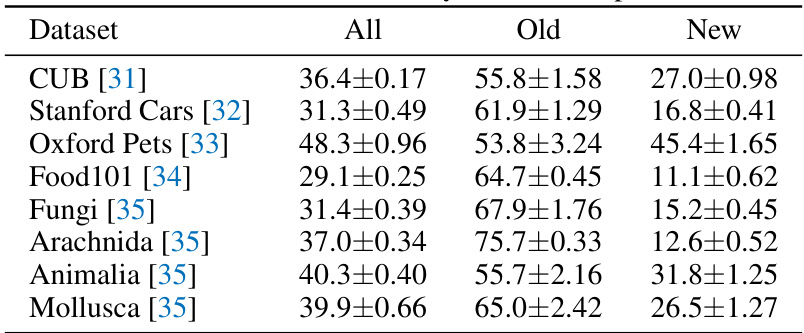

This table presents the mean and standard deviation of the accuracy results across three independent runs for each dataset. The accuracy is broken down into three categories: ‘All’, ‘Old’, and ‘New’. ‘All’ represents the overall accuracy, ‘Old’ represents the accuracy for known categories, and ‘New’ represents the accuracy for newly discovered categories. The standard deviation provides a measure of the variability of the results.

This table presents the results of the proposed PHE method and compares its performance on two datasets (CUB and SCars) under two different input scenarios: fixed sequences and random sequences. The ‘All’, ‘Old’, and ‘New’ columns represent the overall accuracy, accuracy on known classes, and accuracy on novel classes, respectively. The results show the robustness of the PHE method to different input orders.

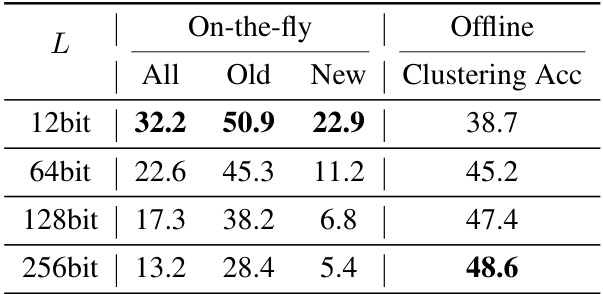

This table compares the performance of SMILE in on-the-fly and offline settings with various hash code lengths (L). The ‘On-the-fly’ columns show the All, Old, and New class accuracy when SMILE is used for online category discovery. The ‘Offline Clustering Acc’ column indicates the clustering accuracy achieved by applying k-means clustering to the high-dimensional features before hashing, representing the upper bound of performance achievable without the constraints of online inference. The results show a trade-off; shorter hash lengths improve on-the-fly performance but reduce offline clustering accuracy, highlighting the sensitivity issue of hash-based methods.

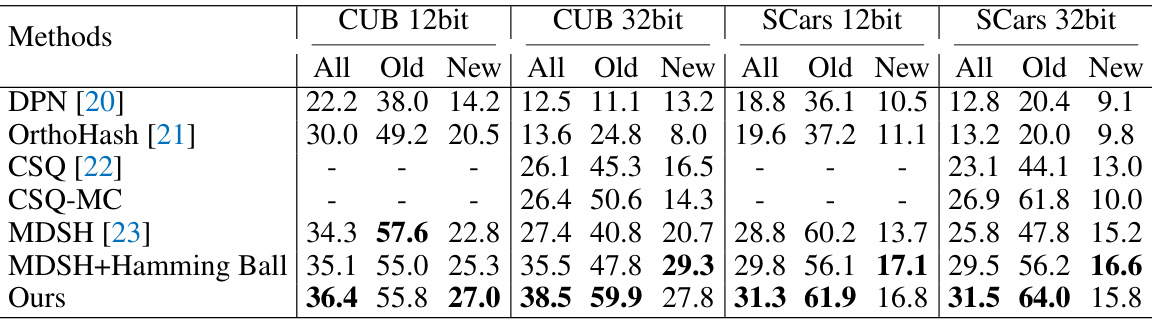

This table compares the performance of different deep hashing methods on CUB and Stanford Cars datasets. The methods are evaluated using 12-bit and 32-bit hash code lengths, and results show all class accuracy, old class accuracy, and new class accuracy. The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed method (Ours) compared to other state-of-the-art hashing techniques, particularly in terms of achieving higher accuracies on unseen (‘New’) categories.

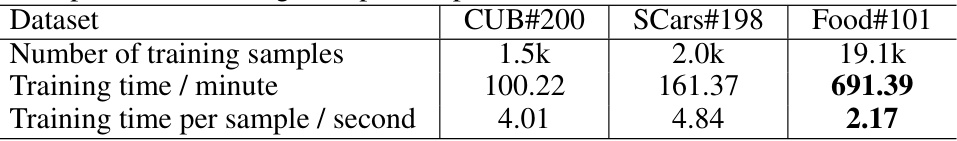

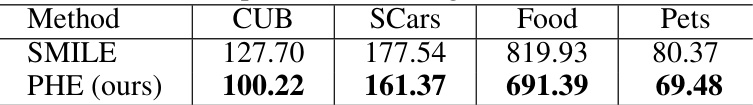

This table compares the training time per sample for three different datasets: CUB-200, Stanford Cars, and Food-101. The number of training samples and the total training time (in minutes) are shown for each dataset. The final column calculates the training time per sample (in seconds), which provides a useful metric for comparing training efficiency across datasets of varying sizes. The significant difference in training time per sample suggests that dataset size affects training efficiency, although the smaller number of categories in Food-101 is likely a contributing factor.

This table compares the training times of the proposed PHE method and the SMILE method on four datasets: CUB, SCars, Food, and Pets. The results show that PHE requires significantly less training time than SMILE across all four datasets. This difference in training time is attributed to the higher computational demands of SMILE’s supervised contrastive learning approach.

This table compares the performance of the proposed PHE method with several state-of-the-art methods on eight fine-grained datasets. The datasets include CUB-200, Stanford Cars, Oxford-IIIT Pet, Food-101, and four super-categories from iNaturalist (Fungi, Arachnida, Animalia, and Mollusca). The results are presented as All (overall accuracy), Old (accuracy on seen categories), and New (accuracy on unseen categories). The table shows that PHE consistently outperforms other methods across all datasets and metrics, particularly demonstrating significant improvements in accuracy on unseen categories.

This table presents a comparison of the proposed PHE method with several state-of-the-art methods on eight fine-grained datasets. The performance is evaluated using clustering accuracy, separately for all classes, old (known) classes, and new (unknown) classes. The table shows that PHE significantly outperforms existing methods on all metrics and datasets, especially for new classes.

Full paper#