↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current research on scaling large language models (LLMs) primarily focuses on model parameters and training data, often overlooking the crucial role of vocabulary size. This leads to a significant variability in vocabulary sizes across different LLMs, potentially hindering their performance and efficiency. The paper identifies this as a major limitation and emphasizes the need for a more comprehensive understanding of the LLM scaling laws that consider vocabulary size.

This paper introduces three novel approaches for predicting the optimal vocabulary size for LLMs based on compute budget, loss function analysis, and derivative estimation. These methods are validated empirically, demonstrating that larger models indeed benefit from larger vocabularies. The study highlights that many existing LLMs use insufficient vocabulary sizes, leading to suboptimal performance. By jointly considering tokenization, model size and training data, the research improves downstream performance and offers valuable insights for optimizing LLM training and deployment.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the common practice of neglecting vocabulary size in large language model (LLM) scaling laws. By demonstrating that optimal vocabulary size scales with model size and compute, it significantly improves LLM efficiency and performance, offering important insights and a new direction for future research. It also highlights the need for joint consideration of tokenization, model parameters, and training data.

Visual Insights#

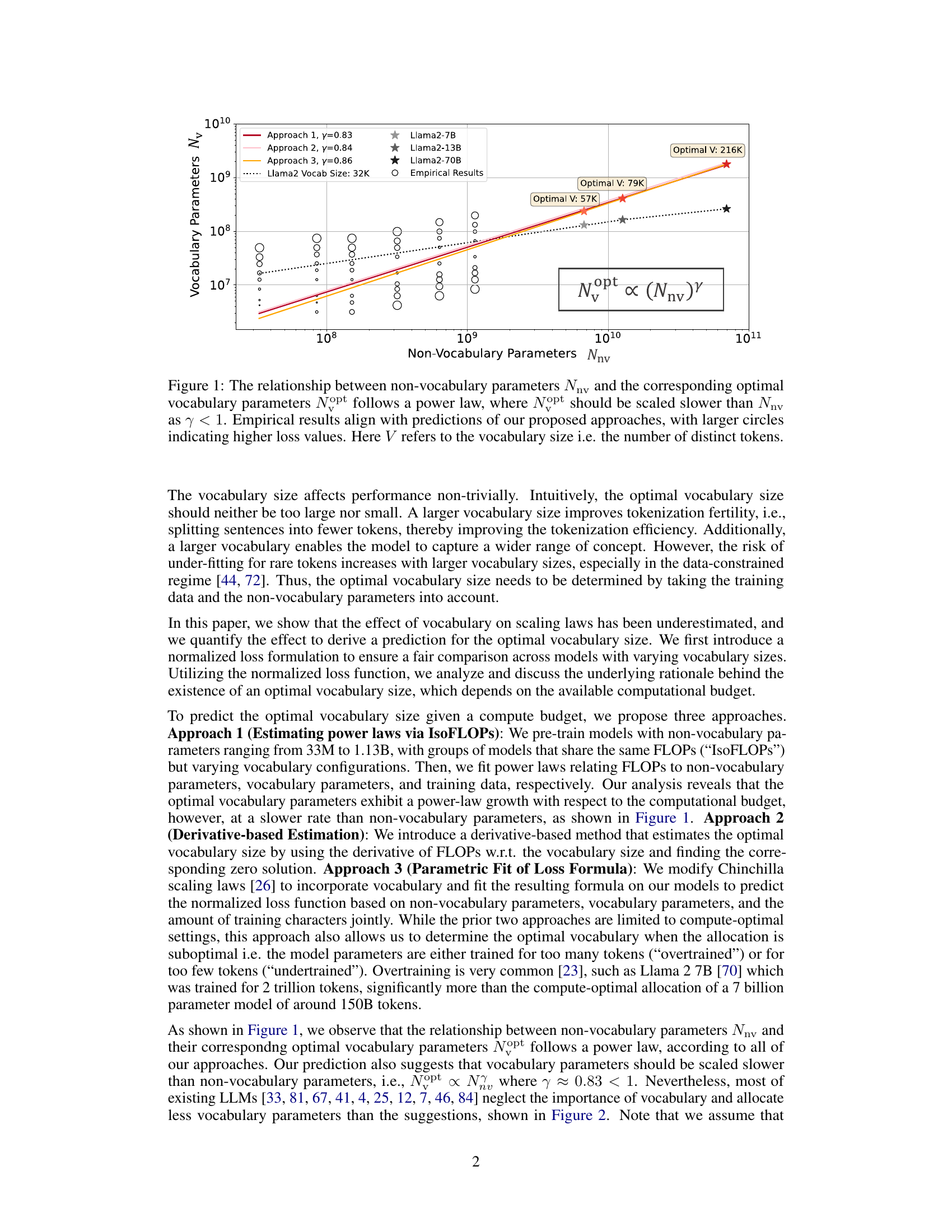

This figure illustrates the relationship between the number of non-vocabulary parameters (Nnv) in a language model and the corresponding optimal number of vocabulary parameters (Nopt). The data suggests a power-law relationship, where Nopt scales slower than Nnv (y < 1). The plot shows empirical results from model training, which generally align with the predictions made using three different approaches proposed in the paper. Larger circles represent higher loss values during training.

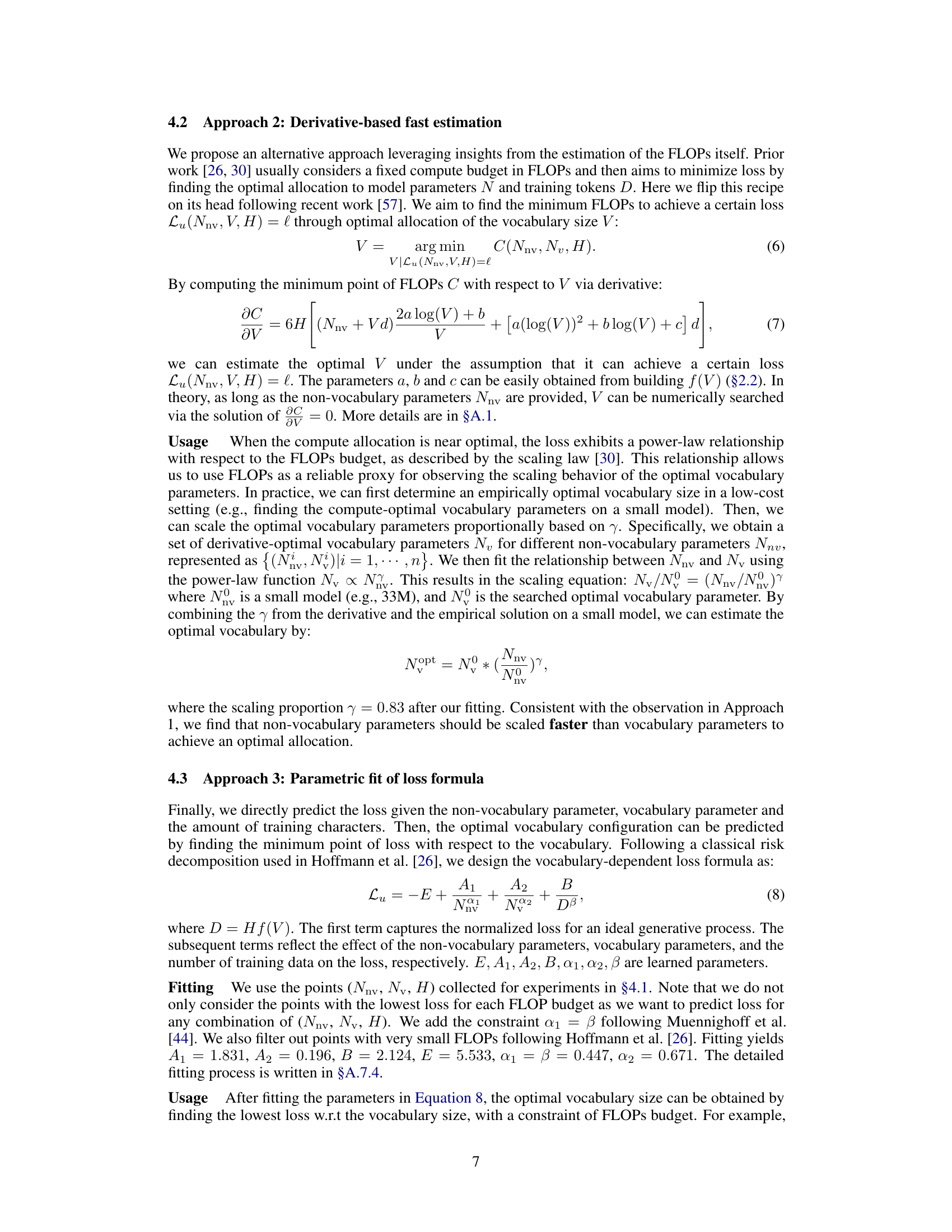

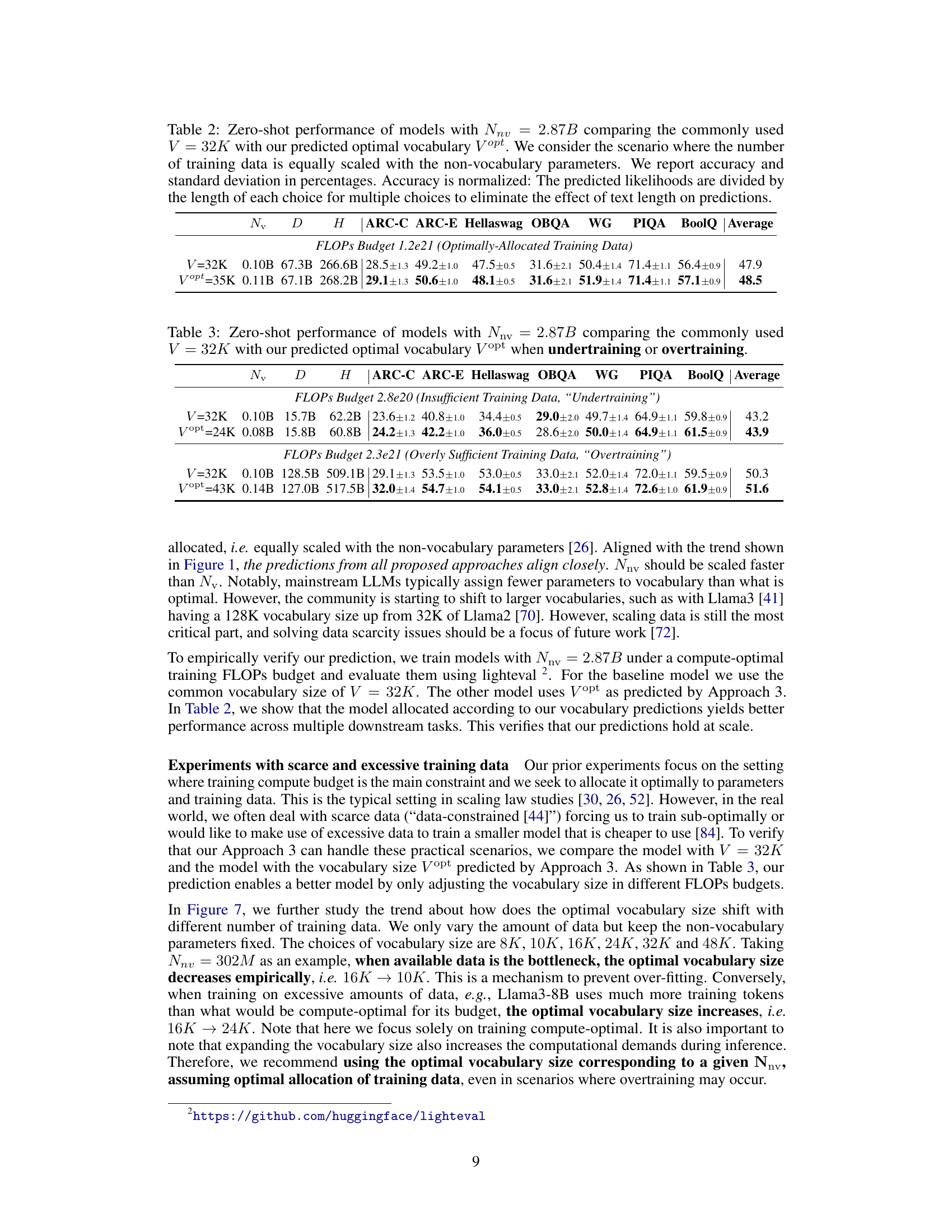

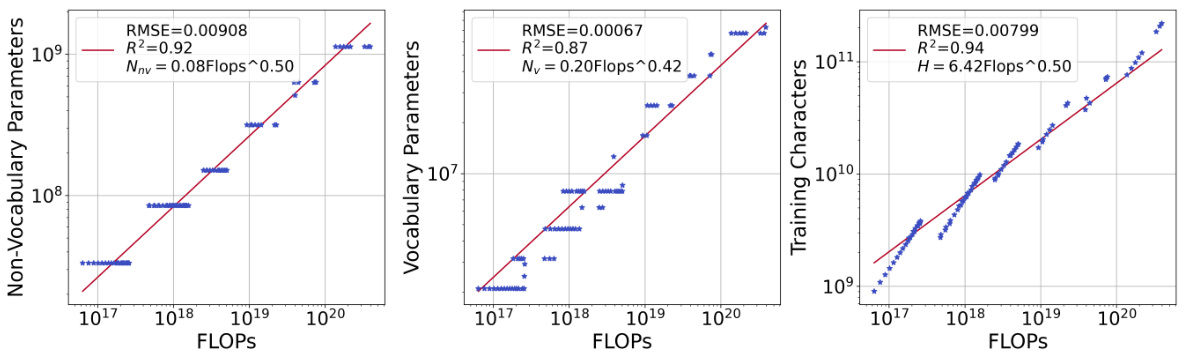

This table presents the predicted optimal vocabulary parameters (Nv) and vocabulary sizes (V) for different model sizes (Nnv) based on three different approaches (App1, App2, App3). The predictions are made under the assumption that the training FLOPs are optimally allocated and that the non-vocabulary parameters and training data are scaled equally. The table shows the optimal vocabulary size according to each approach and the corresponding FLOPs budget.

In-depth insights#

Vocab Scaling Laws#

The concept of ‘Vocab Scaling Laws’ explores how the size of a language model’s vocabulary affects its performance and scaling behavior. Research suggests that larger models benefit from significantly larger vocabularies than conventionally used. This is because an insufficient vocabulary can limit the model’s ability to capture nuances of language, hindering both training efficiency and downstream performance. However, increasing vocabulary size also comes with computational costs. Therefore, finding the optimal vocabulary size, which scales with model size and compute budget, is a crucial aspect of efficient LLM training. This research highlights the need to move beyond simplistic scaling laws focusing solely on parameters and data, and instead consider the intricate interplay between vocabulary, model size, compute resources, and data quantity for efficient and effective large language model development.

Optimal Vocab Size#

The concept of ‘optimal vocabulary size’ in large language models (LLMs) is explored in depth, challenging the conventional wisdom of using fixed vocabulary sizes. Research reveals a strong correlation between optimal vocabulary size and the model’s computational budget, suggesting larger models benefit from significantly larger vocabularies than currently implemented. Three complementary approaches, IsoFLOPs analysis, derivative estimation, and parametric loss fitting, are utilized to predict this optimal size. The findings consistently indicate that most LLMs underutilize their vocabulary capacity, hindering potential performance gains. Empirically, increasing the vocabulary size demonstrably improves downstream task performance within the same computational constraints. However, the research also highlights the non-trivial trade-offs involved, acknowledging that excessively large vocabularies can negatively impact performance due to undertraining and data sparsity issues. This highlights the importance of carefully balancing vocabulary size with both the model’s capacity and the amount of training data.

IsoFLOPs Analysis#

IsoFLOPs analysis, short for Isofunctional FLOPs analysis, is a crucial methodology in evaluating the scaling laws of large language models (LLMs). It involves training multiple LLMs with varying model parameters (such as vocabulary size and number of non-vocabulary parameters), but maintaining a constant computational budget (measured in FLOPs). By holding FLOPs constant, IsoFLOPs analysis isolates the effect of individual parameters on model performance, allowing researchers to determine optimal parameter configurations for a given compute budget. This approach is particularly insightful for analyzing the relationship between vocabulary size and overall LLM performance, shedding light on whether larger models benefit from larger vocabularies and how this scales with computational constraints. The results from IsoFLOPs analysis are often visualized as power laws, demonstrating how the optimal vocabulary size changes as the computational budget varies. This methodology provides a systematic way to optimize LLM development by identifying compute-optimal vocabulary sizes, maximizing the performance gains for a given level of computational resources. By carefully considering the impact of individual parameters within a fixed FLOPs budget, IsoFLOPs analysis helps researchers make better-informed decisions about LLM architecture and resource allocation.

Derivative Method#

A derivative-based method offers a computationally efficient approach to estimating the optimal vocabulary size for large language models. It leverages the concept of finding the minimum FLOPs (floating-point operations) required to achieve a certain loss by calculating the derivative of FLOPs with respect to vocabulary size. This approach cleverly sidesteps the need for extensive experimentation across various vocabulary configurations. However, its accuracy relies heavily on the precision of the FLOPs equation and the pre-existing relationship between FLOPs and other model attributes. While it provides a fast estimation, it doesn’t independently optimize the allocation of other crucial resources like model parameters and training data, instead relying on pre-existing knowledge about their relationships with FLOPs. This reliance on empirically derived relationships limits its generalizability and makes it less suitable for scenarios beyond compute-optimal settings. Despite these limitations, the method’s speed and simplicity make it useful for quick estimations during preliminary model configurations.

Future Directions#

Future research directions in large language model (LLM) scaling should prioritize a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between vocabulary size, model architecture, and training data. Extending current scaling laws to encompass diverse model architectures (beyond transformers) and multilingual settings is crucial. Furthermore, investigating the optimal vocabulary size in the context of specific downstream tasks and data scarcity is needed. The impact of different tokenization strategies and their effects on scaling laws should be explored. Finally, developing more sophisticated loss functions that accurately capture the influence of vocabulary size on model performance across various compute budgets will pave the way for more efficient and effective LLM training. Addressing these areas will unlock the full potential of LLMs and improve the overall efficiency and effectiveness of their development.

More visual insights#

More on figures

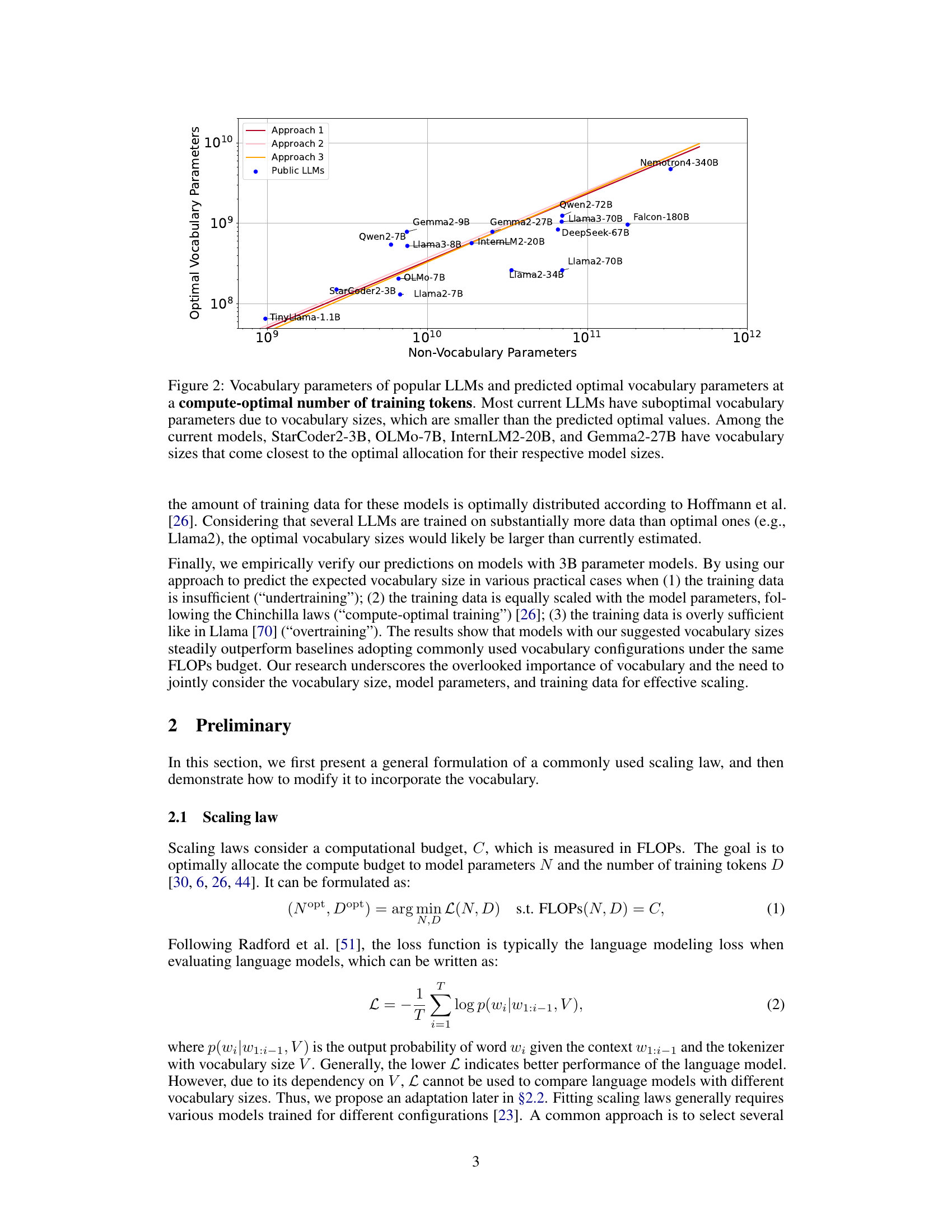

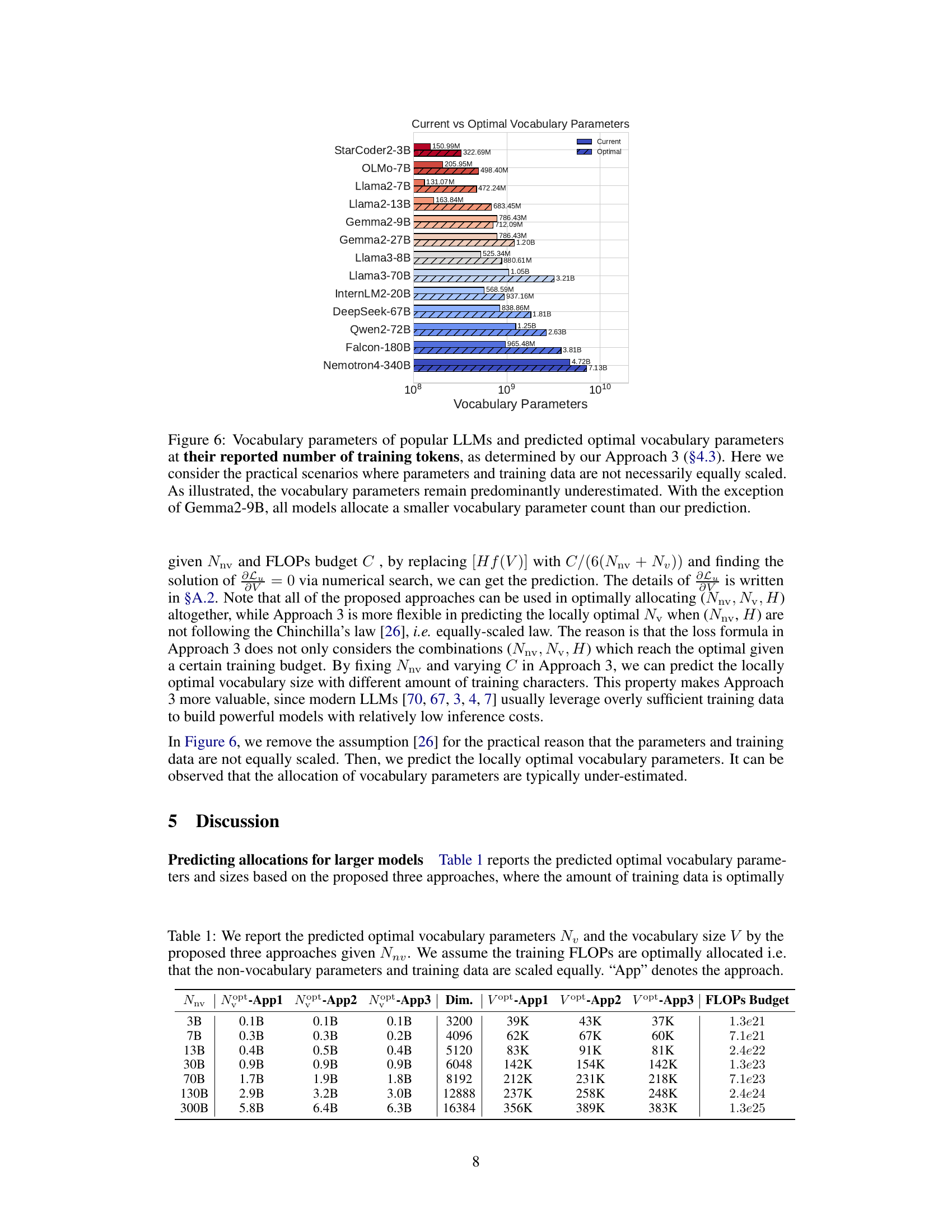

This figure compares the vocabulary parameters used in several popular LLMs against the optimal vocabulary parameters predicted by the authors’ proposed methods. It shows that most existing LLMs significantly underutilize their vocabulary size compared to what is predicted to be optimal given their computational budget and model size. Only a few models come close to the predicted optimal allocation. The x-axis represents the non-vocabulary parameters, and the y-axis represents the optimal vocabulary parameters.

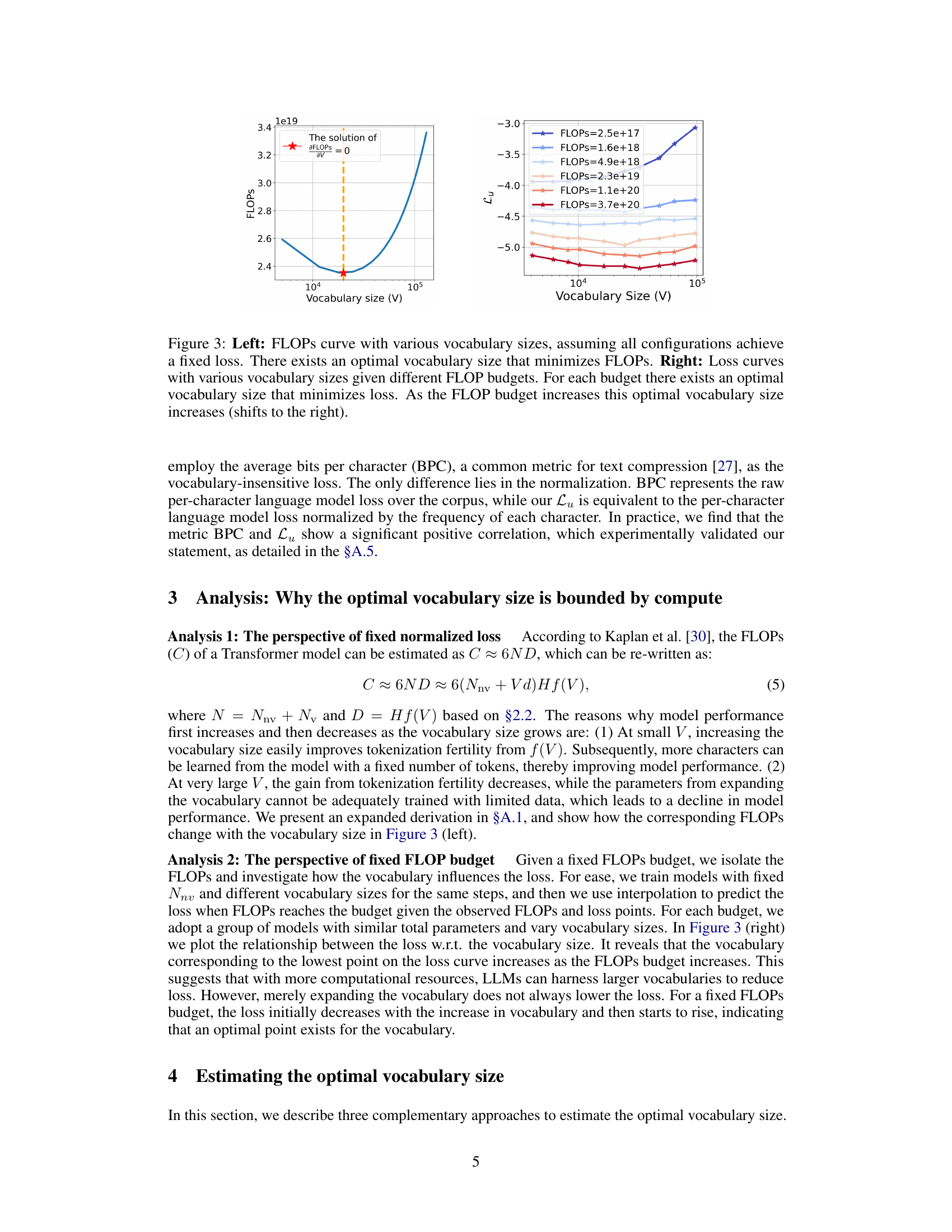

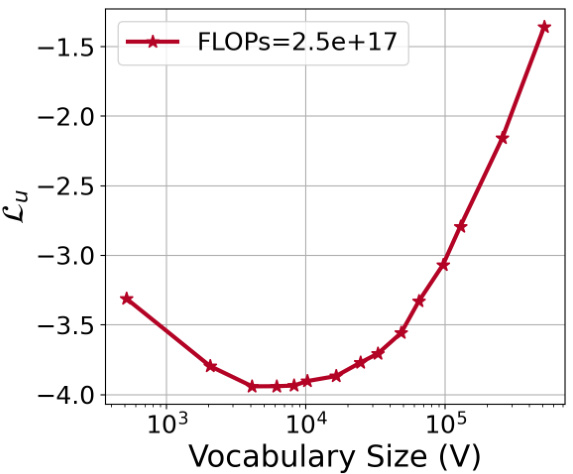

The left panel shows that for a fixed loss, there is an optimal vocabulary size that minimizes the FLOPs. The right panel shows that for various FLOPs budgets, there is an optimal vocabulary size that minimizes loss, and that this optimal size increases with increasing FLOPs budget.

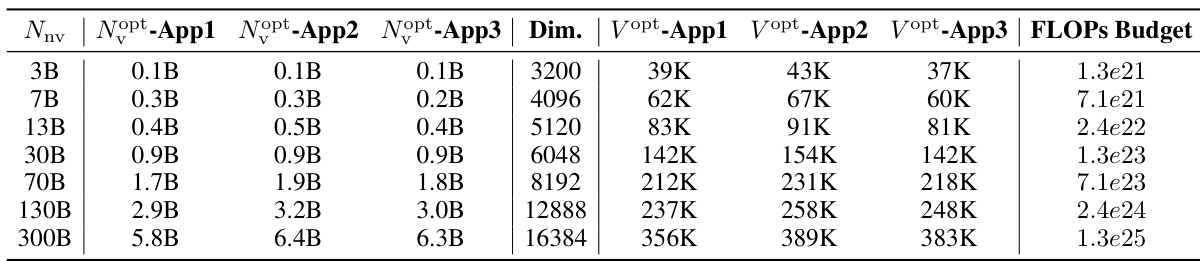

This figure displays training curves for models with varying vocabulary sizes (4K to 96K) but fixed non-vocabulary parameters, showing the relationship between FLOPs and the normalized loss (Lu). The data points represent the compute-optimal allocation of resources for different FLOPs budgets. This data is used in Approach 1 to fit power laws and in Approach 3 to parametrically fit the loss function.

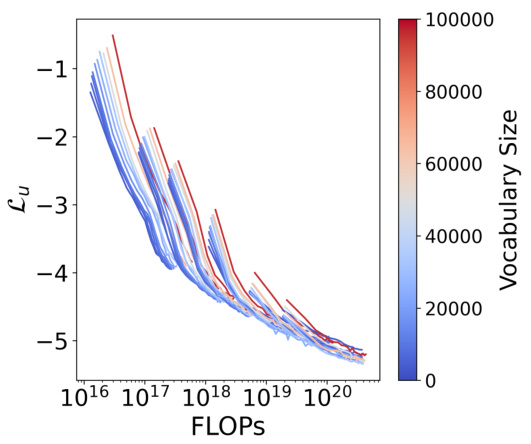

This figure shows the results of fitting power laws to the relationship between FLOPs and the optimal allocation of non-vocabulary parameters, vocabulary parameters, and training data. The blue stars represent the data points where the lowest loss was achieved for each FLOPs budget. Three separate power laws are fitted to show the scaling relationships for each of these parameters.

This figure compares the vocabulary parameters used in several popular large language models (LLMs) with the predicted optimal vocabulary parameters based on the compute-optimal number of training tokens. The authors’ research suggests that most current LLMs underutilize their vocabulary size, resulting in suboptimal performance. The chart highlights the discrepancy between the actual vocabulary sizes and the authors’ predicted optimal sizes, indicating a potential area for improvement in LLM design and training.

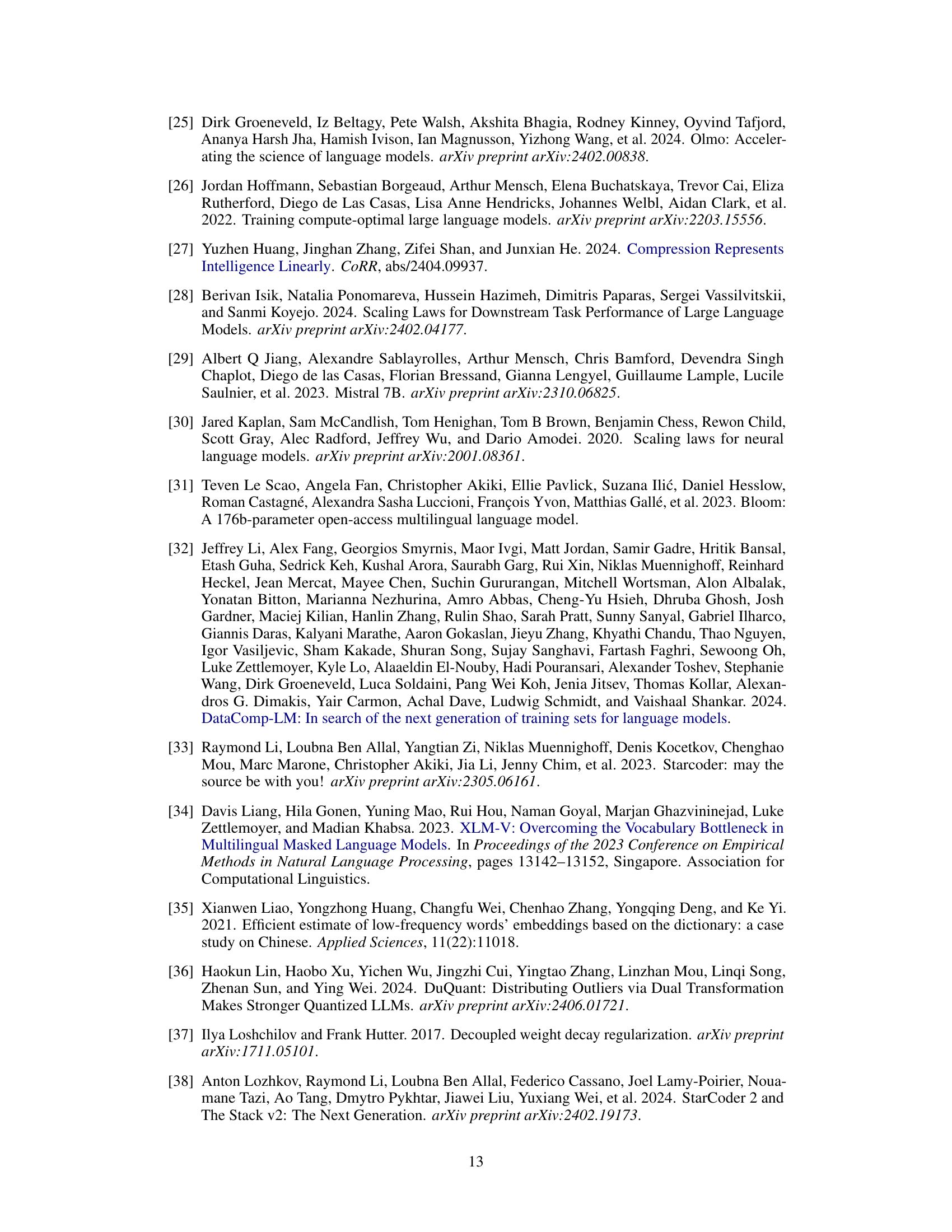

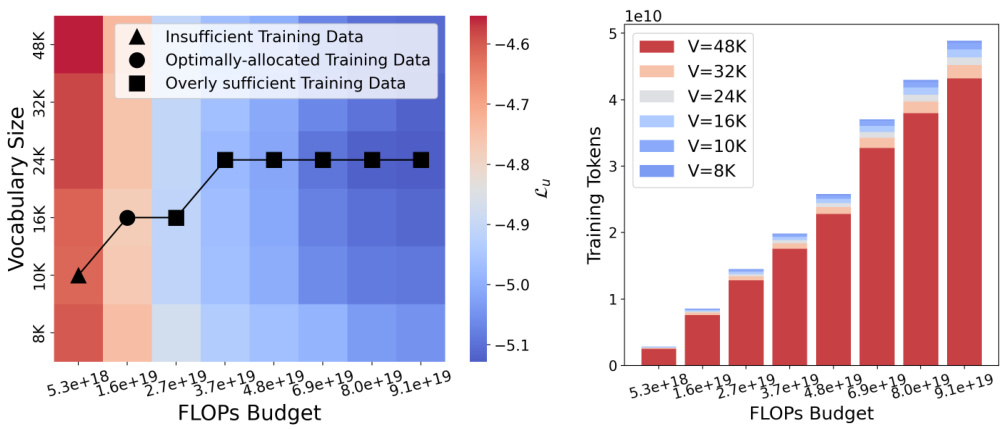

The figure shows how the optimal vocabulary size changes depending on the amount of training data used and the FLOPs budget. The left panel is a heatmap showing the loss for different vocabulary sizes and FLOPs budgets, with different markers indicating different data regimes. The right panel shows the number of training tokens for different vocabulary sizes under a fixed FLOPs budget. In short, more data and compute allow for a larger optimal vocabulary size.

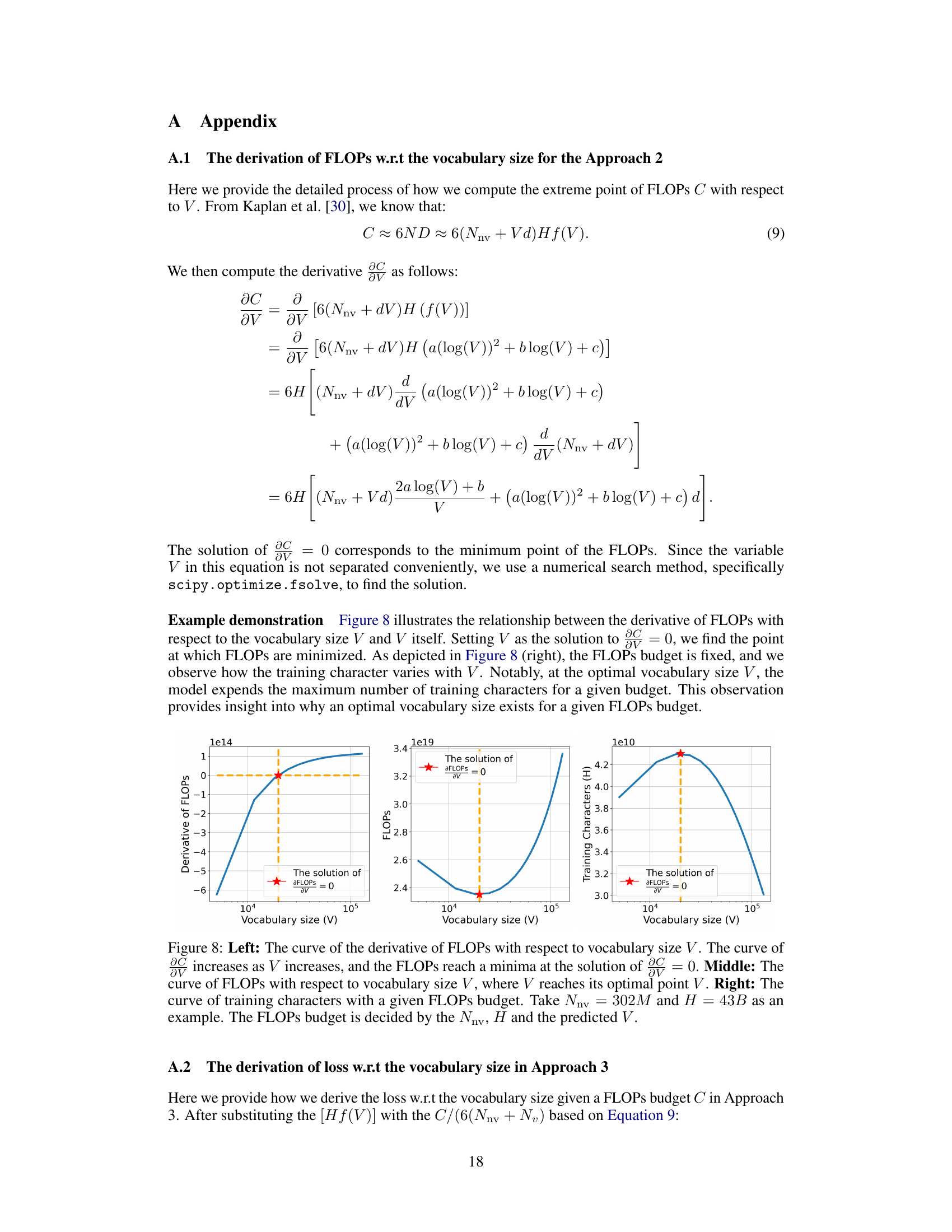

This figure shows three plots illustrating the relationship between the derivative of FLOPs, FLOPs, and training characters with respect to vocabulary size (V). The left plot shows that the derivative of FLOPs increases with increasing vocabulary size, reaching a minimum at the optimal vocabulary size. The middle plot shows that FLOPs decrease with increasing vocabulary size, reaching a minimum at the optimal vocabulary size. The right plot shows that the number of training characters increase with increasing vocabulary size, reaching a maximum at the optimal vocabulary size. These plots together illustrate that there is an optimal vocabulary size for a given FLOPs budget, where performance is maximized.

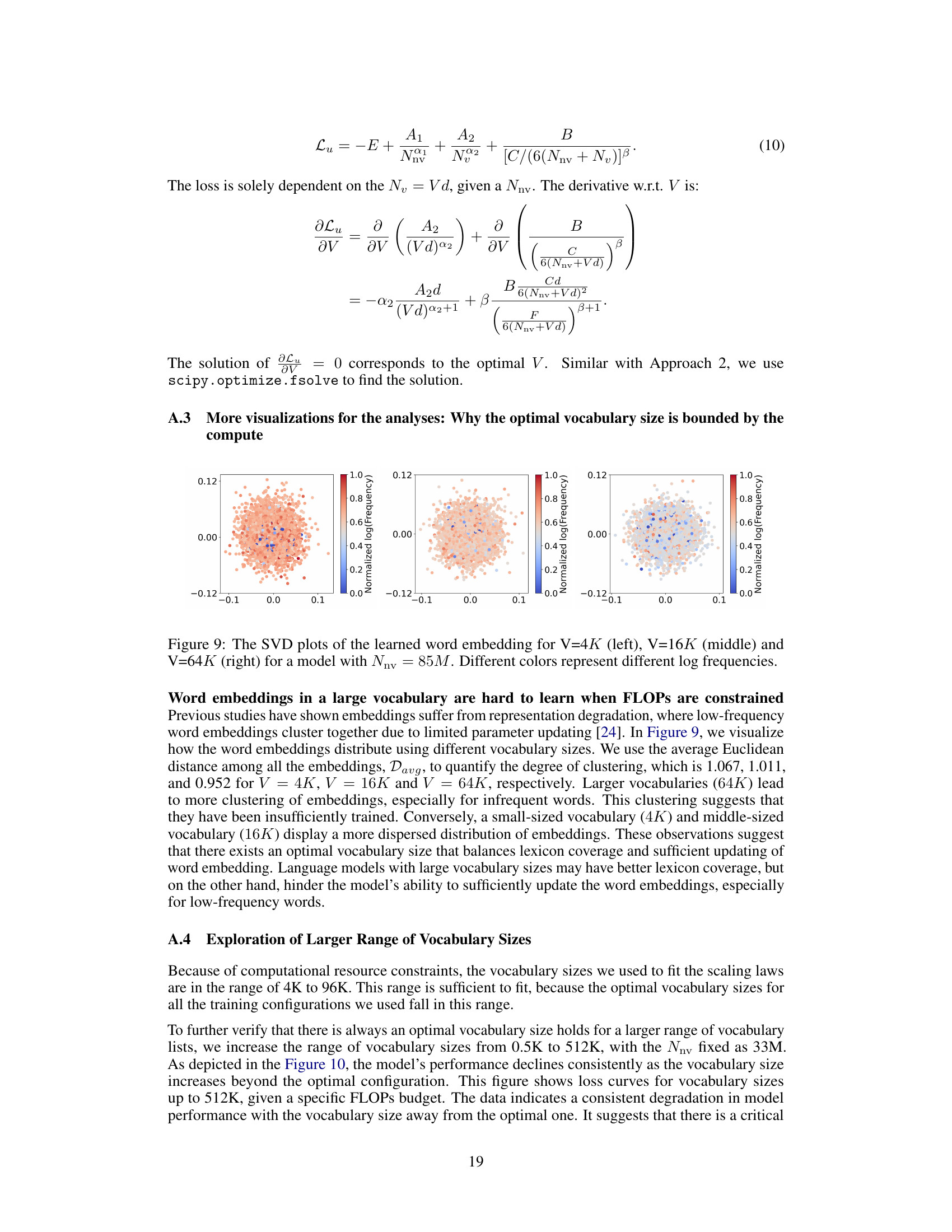

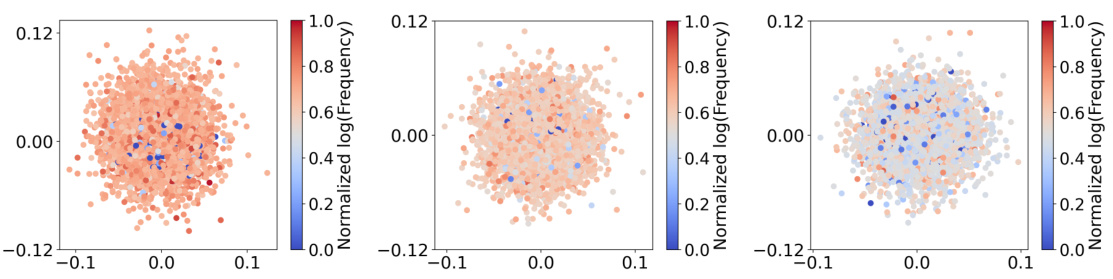

This figure visualizes the distribution of word embeddings learned by models with different vocabulary sizes (4K, 16K, and 64K) using singular value decomposition (SVD). The color intensity represents the log frequency of words. The figure shows that smaller vocabularies lead to a more dispersed distribution of embeddings, while larger vocabularies show more clustering, especially for low-frequency words, indicating insufficient training for those embeddings. This suggests an optimal vocabulary size exists that balances adequate representation of words with sufficient training for all embeddings.

The figure shows two plots related to the optimal vocabulary size for language models. The left plot shows that there is an optimal vocabulary size that minimizes the FLOPs (floating point operations) for a fixed loss. The right plot shows that there is an optimal vocabulary size that minimizes the loss for each FLOPs budget, and that this optimal vocabulary size increases as the FLOPs budget increases.

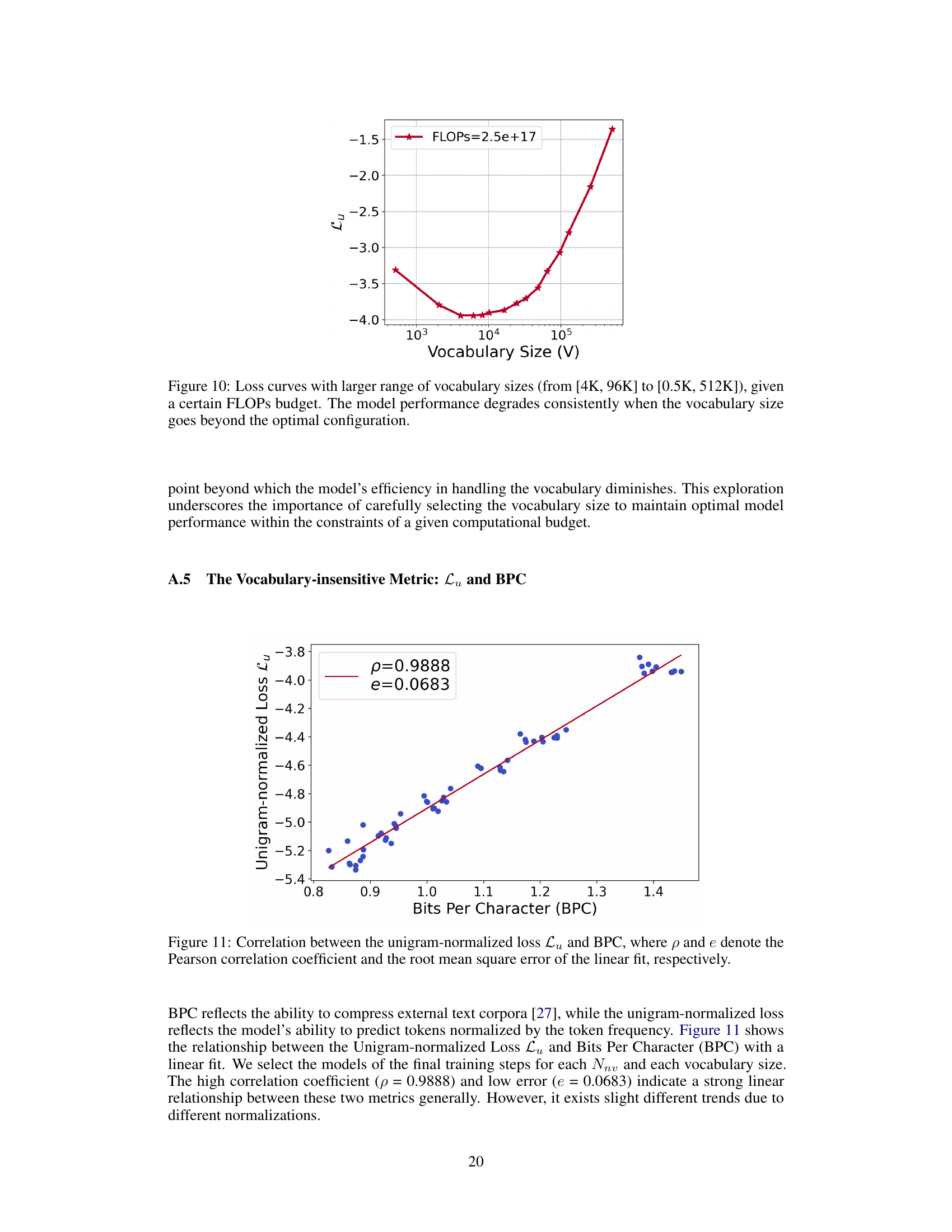

This figure shows the strong positive correlation between the unigram-normalized loss (Lu) and bits per character (BPC). The unigram-normalized loss is a vocabulary-insensitive metric used to compare language models with different vocabulary sizes fairly. BPC measures the average number of bits needed to represent each character in the text corpus. The high correlation (p=0.9888) and low error (e=0.0683) indicate that these two metrics are highly related, demonstrating the effectiveness of Lu as a metric for comparing language models with different vocabulary sizes.

The figure shows two plots. The left plot shows the relationship between FLOPs and vocabulary size when the loss is fixed. There is an optimal vocabulary size that minimizes the FLOPs required. The right plot shows the relationship between loss and vocabulary size for different FLOPs budgets. For each budget, there is an optimal vocabulary size that minimizes the loss. As the budget increases, the optimal vocabulary size also increases.

This figure empirically validates the fairness of the unigram-normalized loss (Lu) used in the paper to compare models with different vocabulary sizes. It shows a strong negative correlation between the unigram-normalized loss and the average normalized accuracy across seven downstream tasks. This confirms that Lu is a suitable metric for comparing models with varying vocabulary sizes, as it avoids the bias introduced by the raw language modeling loss, which increases with vocabulary size.

This figure empirically validates the use of the unigram-normalized loss (Lu) by showing the relationship between the commonly used language modeling loss and the unigram-normalized loss with the performance on seven downstream tasks. It demonstrates that Lu is a fair metric to compare language models with different vocabulary sizes as it shows a negative correlation with downstream performance.

This figure shows the relationship between the number of non-vocabulary parameters (Nnv) in a language model and the corresponding optimal number of vocabulary parameters (Nopt). The relationship follows a power law, meaning Nopt scales slower than Nnv (y < 1). The plot includes empirical results from model training, which generally align with the predictions from three different methods proposed in the paper for estimating optimal vocabulary size. Larger circles represent higher loss values, indicating that deviations from the optimal relationship lead to worse model performance. The figure demonstrates the importance of carefully scaling the vocabulary size relative to other model parameters.

More on tables

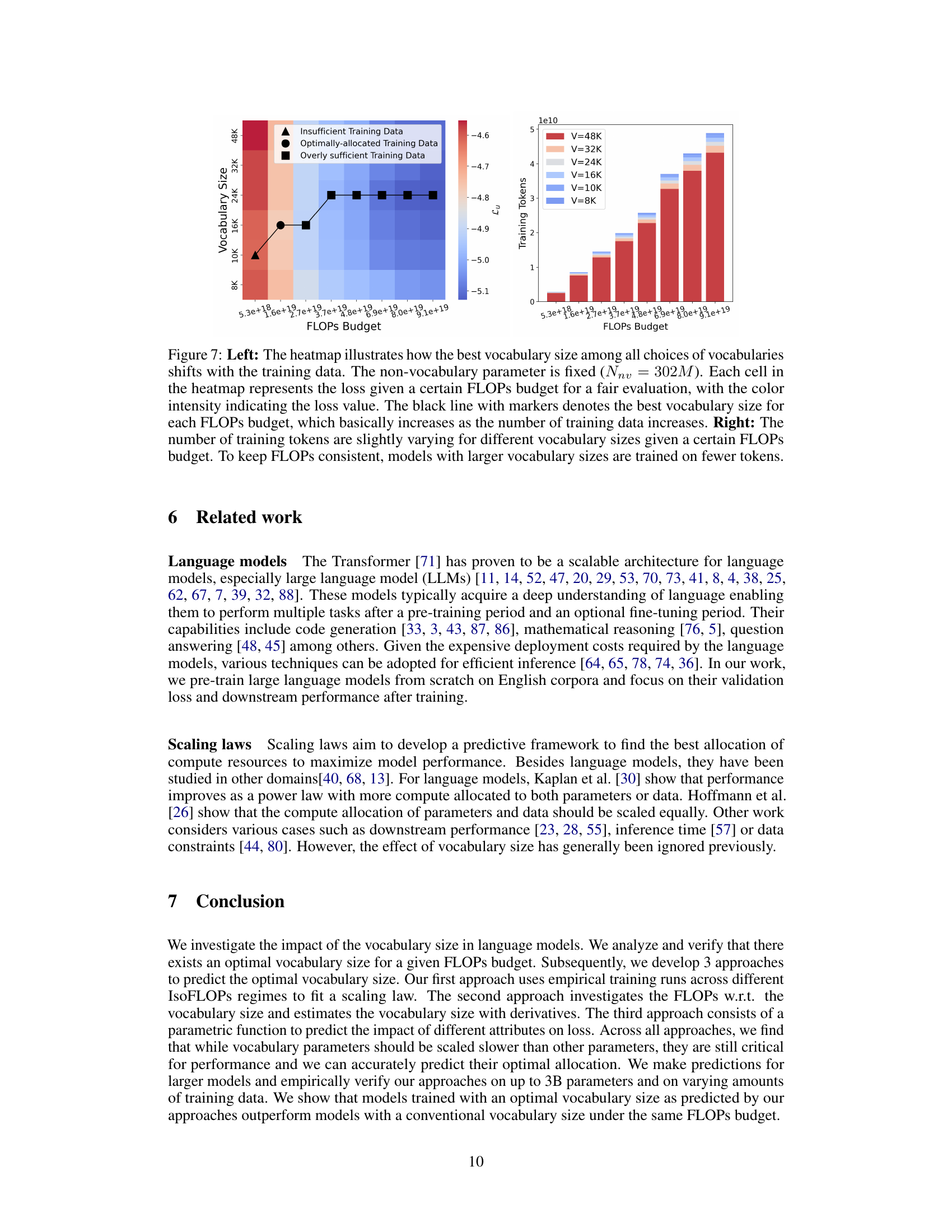

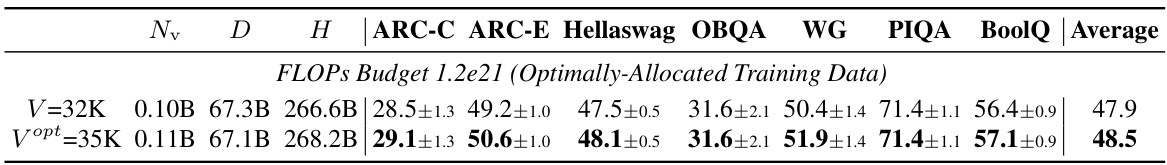

This table presents the zero-shot performance results of language models with 2.87 billion non-vocabulary parameters (Nnv). It compares the performance using a commonly used vocabulary size of 32K against the predicted optimal vocabulary size (Vopt) determined by the authors’ method. The models were trained with an optimal amount of training data, meaning the data size scaled equally with the number of non-vocabulary parameters. The results show accuracy and standard deviation across several downstream tasks (ARC-C, ARC-E, Hellaswag, OBQA, WG, PIQA, BoolQ), and an average score across all tasks.

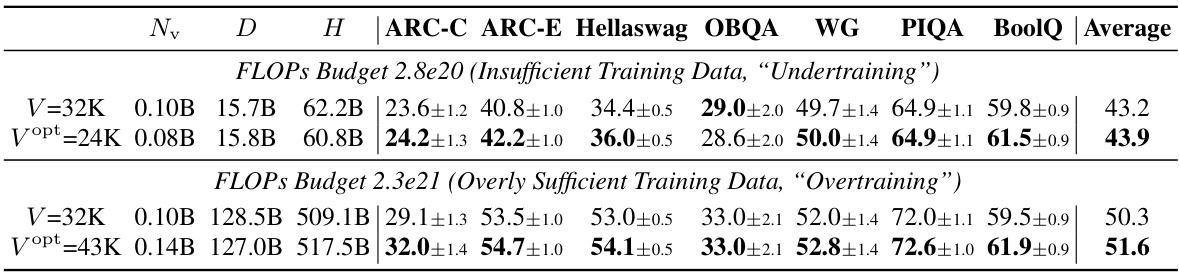

This table presents the zero-shot performance results on eight downstream tasks (ARC-C, ARC-E, Hellaswag, OBQA, WG, PIQA, BoolQ, and Average) for two different vocabulary sizes (V=32K and Vopt) under two training data conditions (insufficient and overly sufficient). The non-vocabulary parameters (Nnv) are kept constant at 2.87B across all experiments. The results show the impact of using the predicted optimal vocabulary size (Vopt) compared to a commonly used size (32K) under different data conditions. The optimal vocabulary size varies depending on whether the model is undertrained or overtrained.

This table lists the architecture details for the language models used in the experiments. For each model, it shows the non-vocabulary parameters (in millions), sequence length, number of layers, number of heads, embedding dimension, intermediate size, and the total number of training characters (in billions). The table provides a clear overview of the model configurations employed throughout the study, enabling reproducibility and facilitating a better understanding of the results presented.

This table shows the predicted optimal vocabulary parameters (Nv) and vocabulary size (V) for different non-vocabulary parameter (Nnv) values using three different approaches (App1, App2, App3). The prediction is based on the assumption that training FLOPs are optimally allocated, meaning the non-vocabulary parameters and training data are scaled equally. The table helps illustrate how the optimal vocabulary size increases with larger models.

Full paper#