↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reconstructing 3D scenes from a single image is a very challenging task in computer vision because of limited information. Existing methods often rely on extensive training data with paired images and 3D models, which restricts generalization to unseen scenarios. This limits their practical application in open-world scenarios.

This research proposes ‘Deep Prior Assembly’, a novel framework addressing the limitations of existing approaches. Instead of data-driven training, it leverages pre-trained large models capable of object segmentation, inpainting, and 3D model generation. These models are combined with novel methods for pose, scale, and occlusion estimation, leading to a robust and efficient zero-shot 3D scene reconstruction. This approach demonstrates superior performance to existing methods on multiple datasets and across diverse scene types, significantly advancing the field of 3D scene reconstruction.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel zero-shot approach to 3D scene reconstruction, a challenging problem in computer vision. It leverages the power of pre-trained large language and vision models, eliminating the need for extensive task-specific training data. This offers a significant advancement, particularly for open-world applications where diverse and unseen data is common. The proposed method’s efficiency and superior performance open new avenues for research in 3D scene understanding and generation.

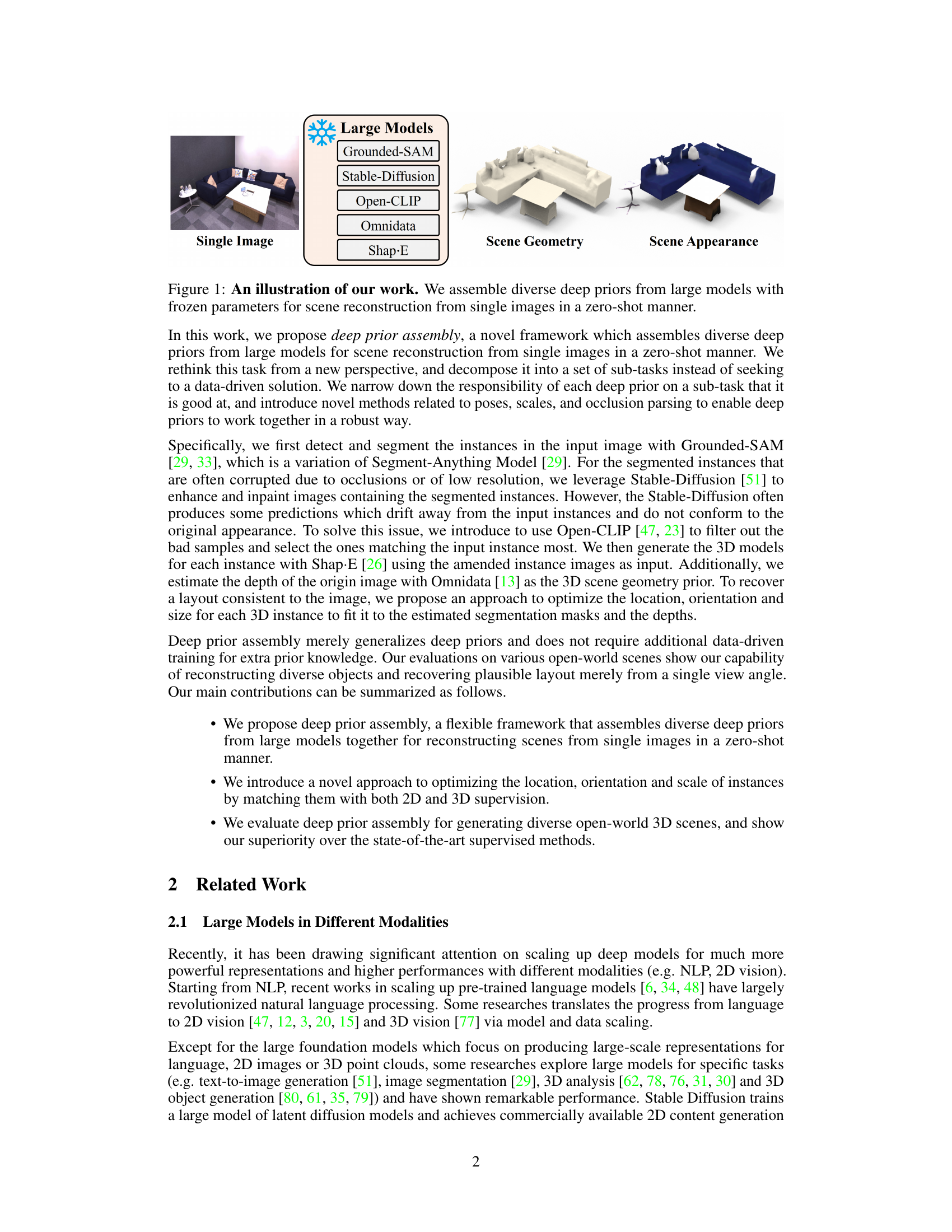

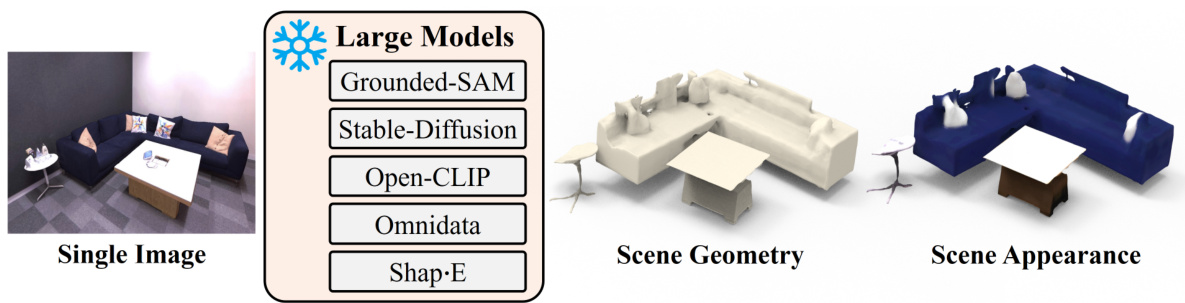

Visual Insights#

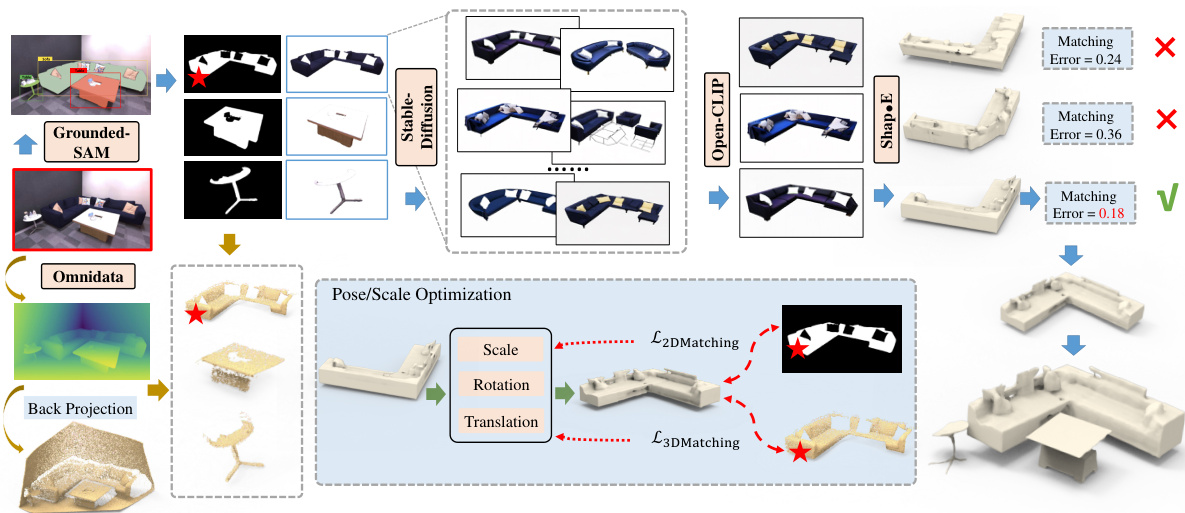

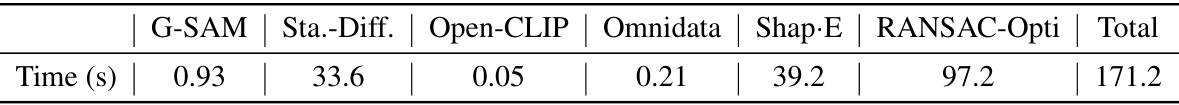

This figure illustrates the overall workflow of the proposed Deep Prior Assembly method. A single image is input to the system, where several large pre-trained models are used to extract different aspects of the scene. Grounded-SAM segments the image into individual objects. Stable Diffusion enhances and inpaints the segmented objects. Open-CLIP filters out poor results from Stable Diffusion, ensuring that only high-quality results proceed. Omnidata estimates depth information, providing geometric context. Finally, Shap-E generates 3D models of the objects. The result is a complete 3D scene reconstruction assembled from these individual components.

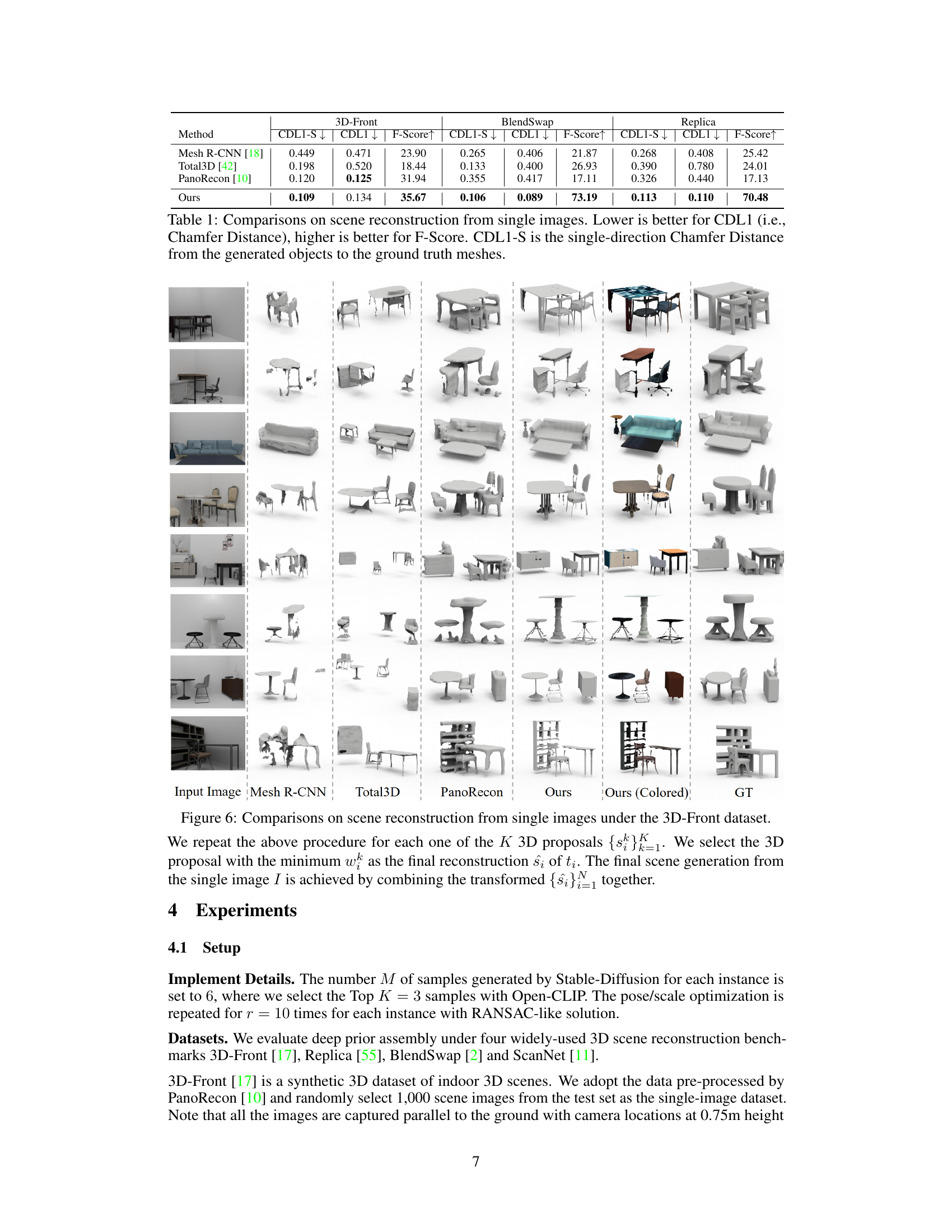

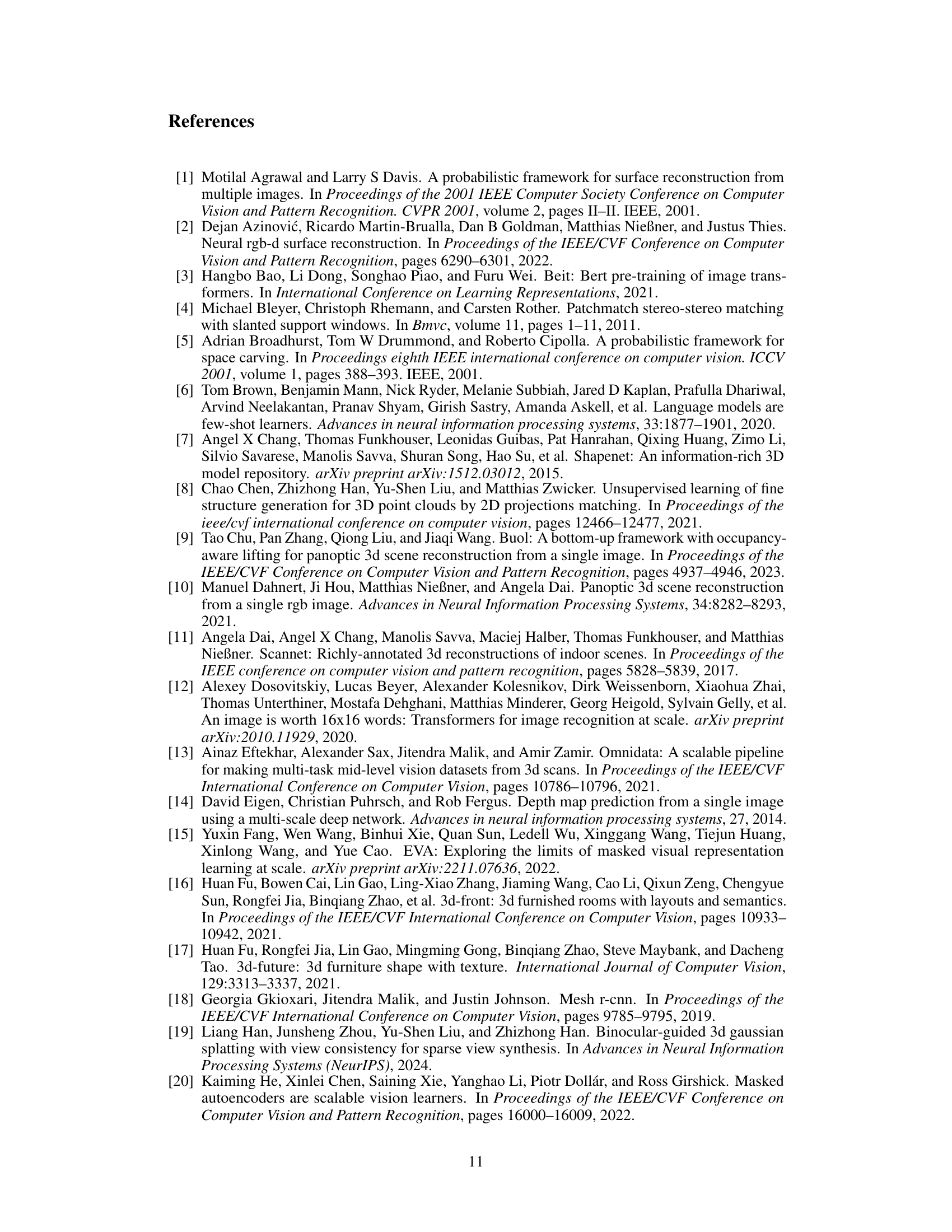

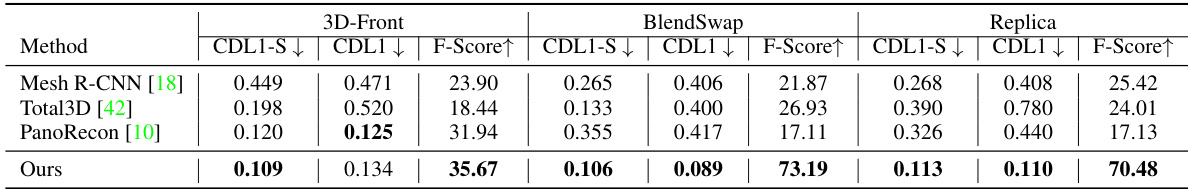

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed Deep Prior Assembly method against three state-of-the-art scene reconstruction methods (Mesh R-CNN, Total3D, and PanoRecon) on three different datasets (3D-Front, Replica, and BlendSwap). The evaluation metrics used are Chamfer Distance (CDL1), a single-direction Chamfer Distance (CDL1-S) measuring the distance from generated objects to ground truth, and F-Score, a measure of reconstruction accuracy. Lower CDL1 and CDL1-S values indicate better performance, while higher F-Score values indicate better performance. The results show that Deep Prior Assembly achieves superior performance across all three datasets compared to the existing methods.

In-depth insights#

Deep Prior Assembly#

The concept of “Deep Prior Assembly” presents a novel approach to zero-shot scene reconstruction by leveraging the power of pre-trained large language and vision models. Instead of training a model from scratch on a specific task, this method cleverly assembles diverse deep priors from various models, each specialized for a sub-task within the overall reconstruction process. This strategy allows for the exploitation of existing knowledge embedded within these models, thereby eliminating the need for extensive task-specific training data. The core idea involves decomposing the complex scene reconstruction problem into smaller, manageable sub-tasks such as object detection, segmentation, inpainting, 3D model generation, and layout optimization. Each sub-task is then entrusted to a specialized model, creating a synergistic pipeline where the output of one stage informs the next. This modularity and reliance on pre-trained models represents a significant departure from traditional data-driven methods, potentially leading to improved generalization to unseen data and enhanced robustness. A key advantage is the capability to generalize across a wide range of open-world scenarios without extensive task-specific fine-tuning, thereby pushing the boundaries of zero-shot learning in 3D scene reconstruction. However, the success of this approach hinges critically on the selection of appropriate models and the careful design of the inter-stage interaction mechanisms. Further research should focus on addressing challenges such as robust error handling, improved layout optimization, and efficient handling of complex scenes with numerous objects and occlusions.

Zero-Shot Learning#

Zero-shot learning (ZSL) aims to predict novel classes not seen during training, a significant advancement over traditional machine learning. This is achieved by leveraging auxiliary information, such as semantic embeddings or visual attributes, to bridge the gap between seen and unseen classes. A key challenge lies in the domain adaptation problem: effectively transferring knowledge from the seen to the unseen domain. Deep learning models have significantly advanced ZSL, enabling more complex representations and knowledge transfer mechanisms. However, generalization to truly unseen classes and real-world applications remains a hurdle, necessitating further research into more robust feature representations, more effective knowledge transfer techniques, and addressing biases inherent in available data. Future directions involve exploring more comprehensive auxiliary information, incorporating more sophisticated attention mechanisms and enhancing the robustness to noisy or limited data for improved real-world performance.

3D Scene Synthesis#

3D scene synthesis aims to generate realistic and coherent three-dimensional scenes from various input modalities, such as images, point clouds, or textual descriptions. A key challenge lies in balancing photorealism with scene consistency, ensuring that the generated 3D model accurately reflects the input data and exhibits physically plausible properties. This often requires integrating multiple sources of information and employing advanced techniques to address issues like occlusion reasoning, geometry reconstruction, and material assignment. Deep learning models, particularly generative adversarial networks (GANs) and diffusion models, have emerged as powerful tools for 3D scene synthesis, capable of creating highly detailed and intricate virtual environments. However, limitations remain, including computational cost, difficulty in controlling specific aspects of the generated scene, and potential artifacts. Further research focuses on developing more efficient and controllable methods, incorporating physical simulation for improved realism, and exploring new applications such as virtual reality, augmented reality, and robotics simulation.

Model Limitations#

A crucial aspect often overlooked in evaluating AI models is a thorough examination of their limitations. While the paper might showcase impressive results, a critical analysis of the model’s shortcomings is necessary for a comprehensive understanding. Data limitations, such as biased or insufficient training data, directly impact the model’s ability to generalize and make accurate predictions, leading to skewed outputs and unfair outcomes. Similarly, architectural limitations inherent in the model’s design might hinder its capacity to capture complex relationships or adapt to unseen patterns. These structural constraints directly affect the model’s performance ceiling. Furthermore, computational limitations pose practical challenges in deploying and scaling the model for real-world use. This includes factors such as high resource requirements, long processing times, and dependence on powerful hardware. The interpretability of the model’s internal processes and decision-making is another critical area needing discussion. If the model’s workings are opaque and not easily understood, it becomes difficult to identify and correct errors or biases in its output, which can have far-reaching consequences. Finally, the model’s generalizability and robustness in handling unexpected or adversarial inputs must be rigorously assessed. Robustness to noisy data and adaptability to different environments are crucial considerations when determining real-world applicability.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the robustness and generalization capabilities of the deep prior assembly framework is crucial, particularly for handling complex, real-world scenes with significant variations in lighting, occlusion, and object diversity. Developing more sophisticated methods for handling occlusions is essential to accurately reconstruct occluded regions. Investigating the use of alternative 3D representation methods beyond meshes and point clouds, such as signed distance functions, could potentially improve accuracy and efficiency. Furthermore, exploring incorporation of other modalities, like depth information or semantic labels, could enhance scene understanding and reconstruction accuracy. Finally, assessing the effectiveness of the deep prior assembly approach on different datasets and tasks is necessary to demonstrate its true potential and limitations. Further work should focus on scaling the approach to handle larger scenes and improving computational efficiency. Addressing these challenges could pave the way for the development of more practical and versatile scene reconstruction methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the Deep Prior Assembly pipeline. It starts with a single image as input and uses several large pre-trained models sequentially to generate a 3D scene reconstruction. Grounded-SAM segments objects, Stable Diffusion enhances images, OpenCLIP filters results, Shap-E generates 3D models, and Omnidata provides depth information for layout optimization. The process iteratively refines the reconstruction until the optimal 3D scene is produced.

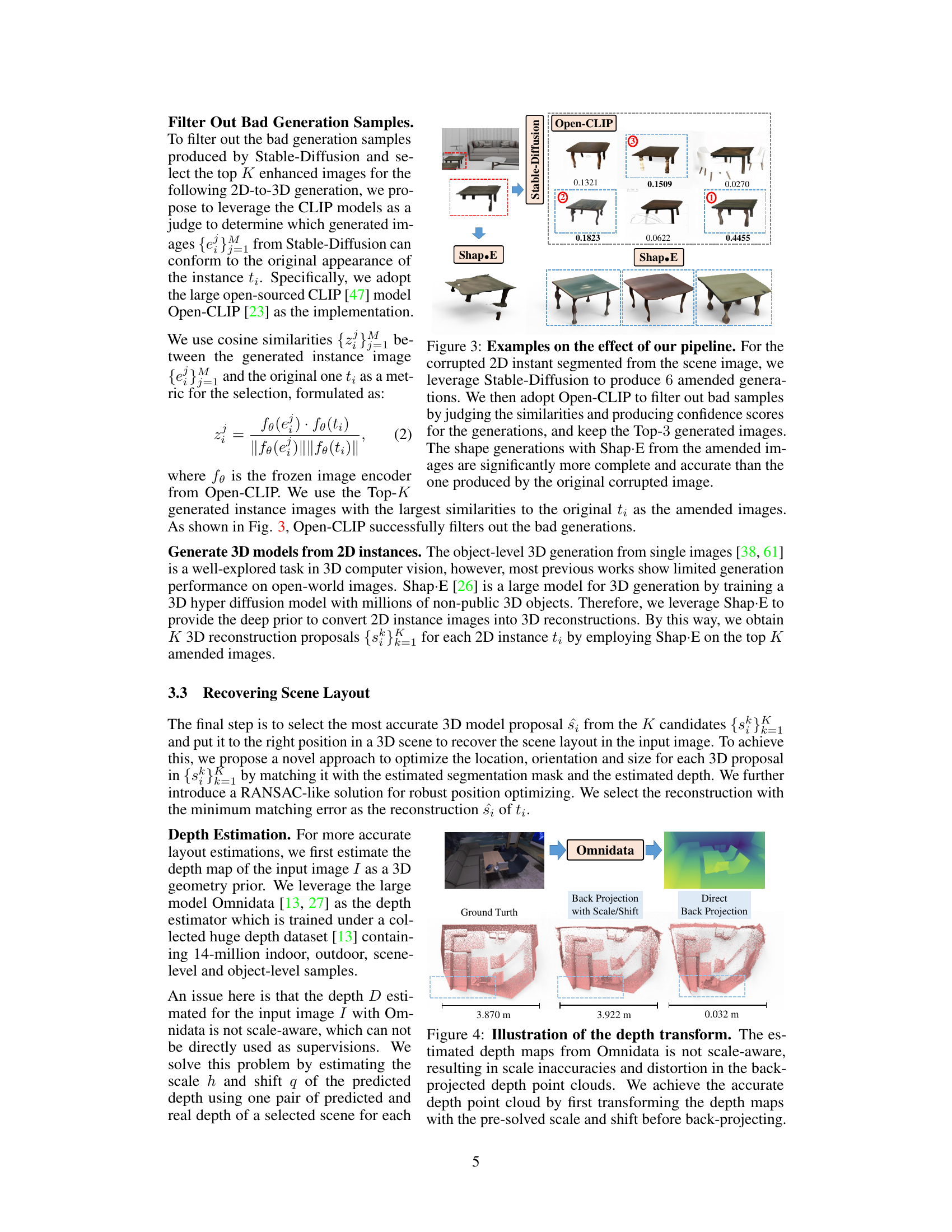

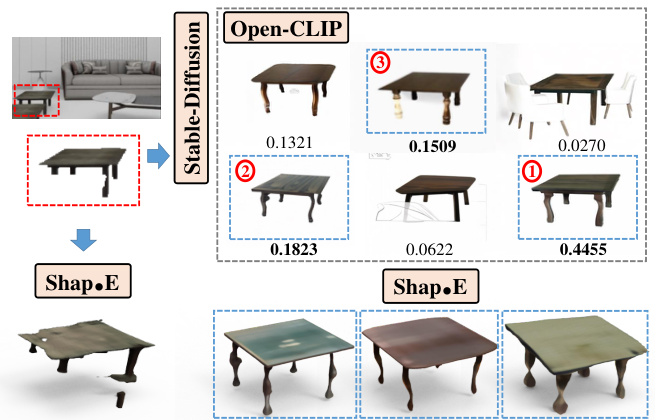

This figure demonstrates the pipeline’s ability to enhance and inpaint corrupted 2D instances before 3D model generation. It highlights the use of Stable Diffusion for generating multiple versions of an image, OpenCLIP to select the most suitable versions based on similarity to the original, and finally Shap-E to generate the 3D models. The results show that using this pipeline significantly improves the quality and completeness of the final 3D model compared to using the original, corrupted instance.

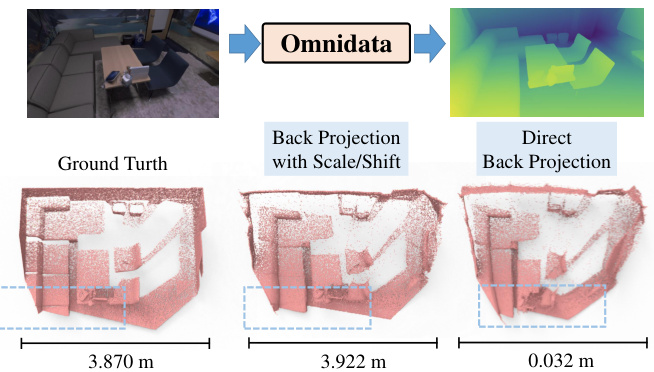

The figure shows the depth map estimation and back projection results from Omnidata. The leftmost image shows the ground truth depth. The middle image shows the depth map estimated by Omnidata, which is not scale-aware and produces distorted results after direct back projection (rightmost image). However, after applying a scale and shift transformation to correct for this, the back-projected point cloud (middle image) accurately matches the ground truth.

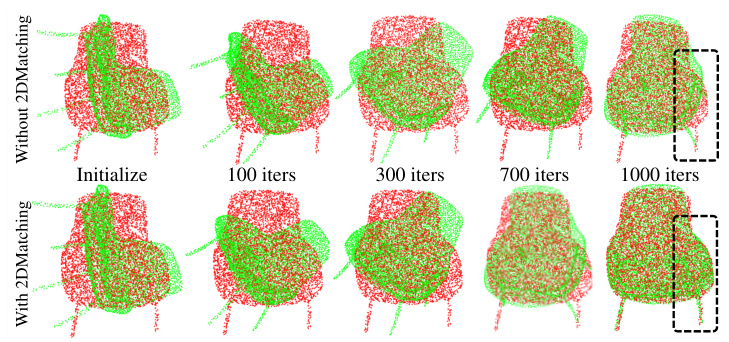

This figure demonstrates the impact of using 2D matching in addition to 3D matching during the pose and scale optimization step for 3D object placement in a scene. The top row shows the optimization process without 2D matching, revealing instability and drift. The bottom row, with 2D matching added, illustrates a more robust and accurate registration process, leading to better alignment between the generated 3D model and the 2D mask from the input image. The visualization clearly shows how the green (projected 3D points) and red (sampled 2D points) converge more effectively with 2D matching, resulting in more accurate placement of the 3D chair model in the final scene.

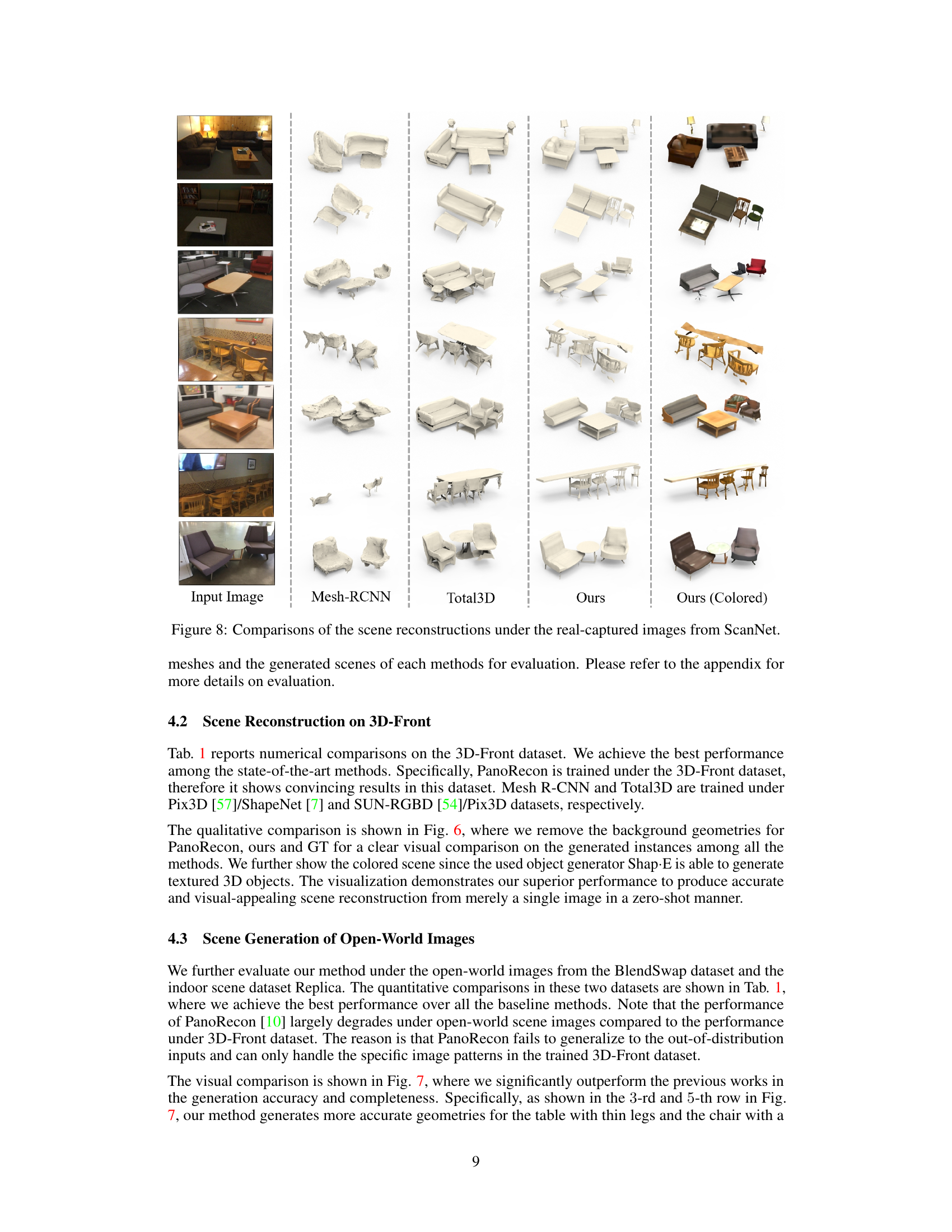

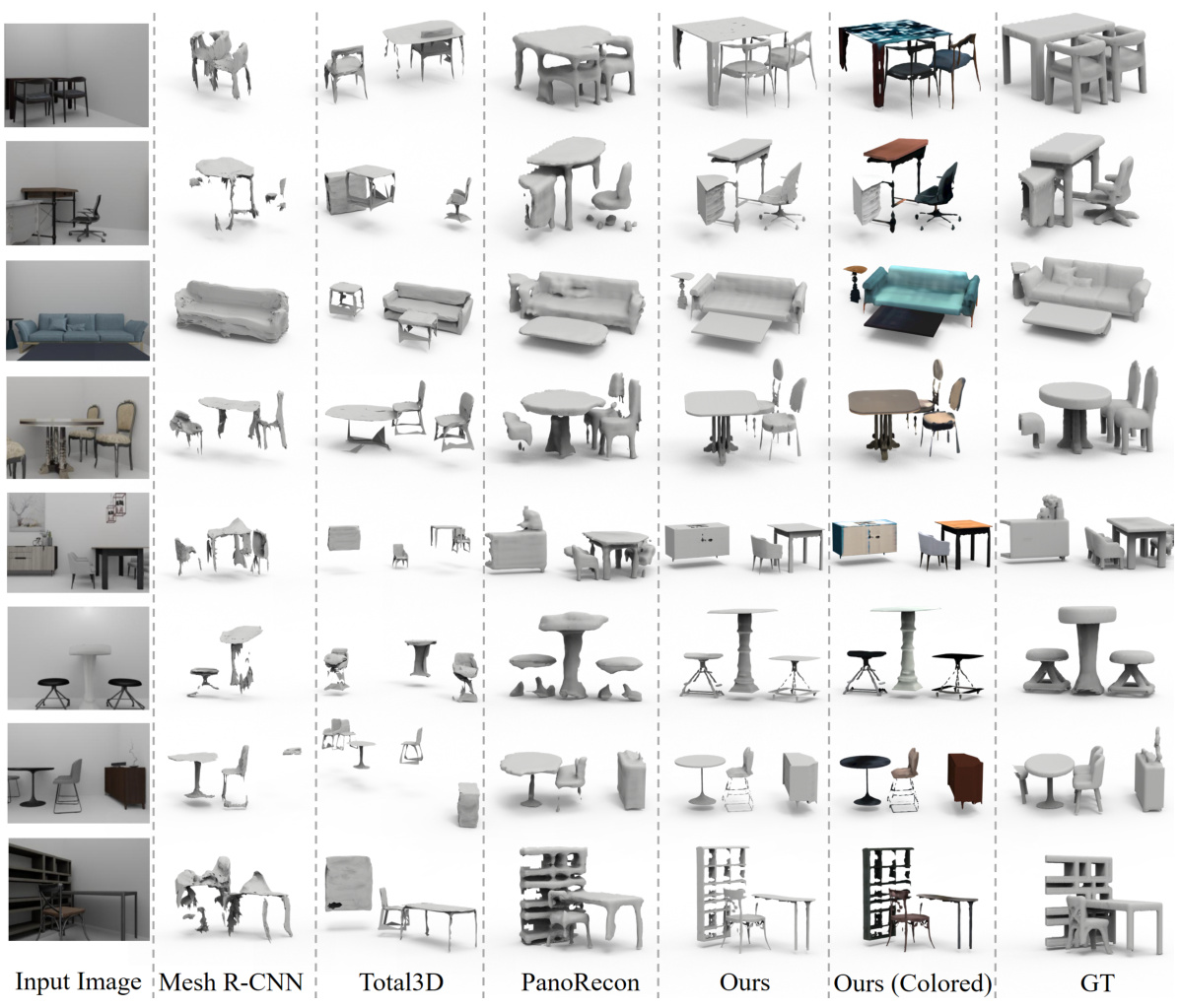

This figure compares the results of scene reconstruction from single images using four different methods: Mesh R-CNN, Total3D, PanoRecon, and the authors’ proposed method. The ground truth (GT) is also shown for comparison. Each row represents a different input image, and the corresponding reconstructions generated by each method are displayed side-by-side. The figure demonstrates the superior performance of the authors’ method in terms of accuracy and completeness of the generated scene geometries. The colored version of the authors’ results is also presented to showcase the model’s ability to generate textured 3D objects.

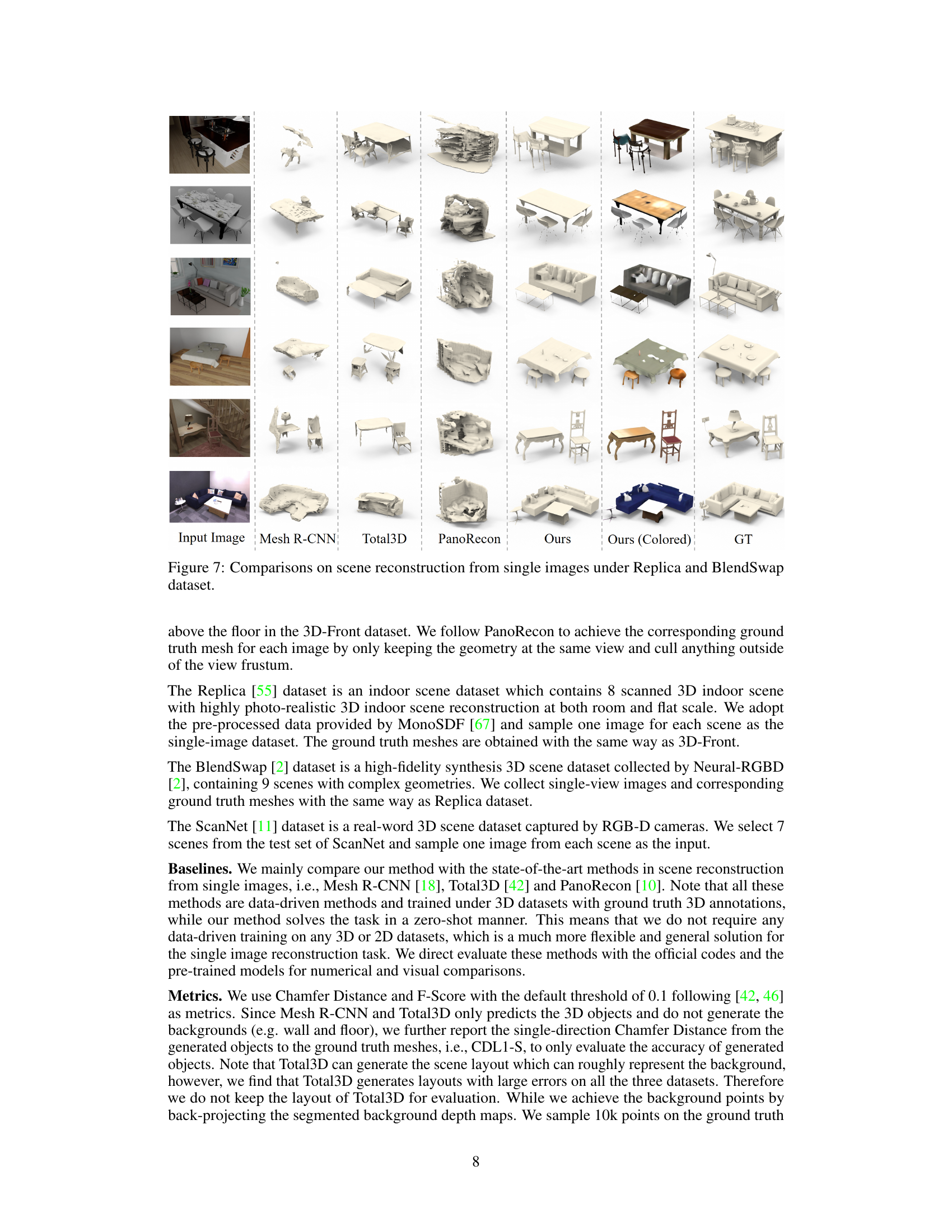

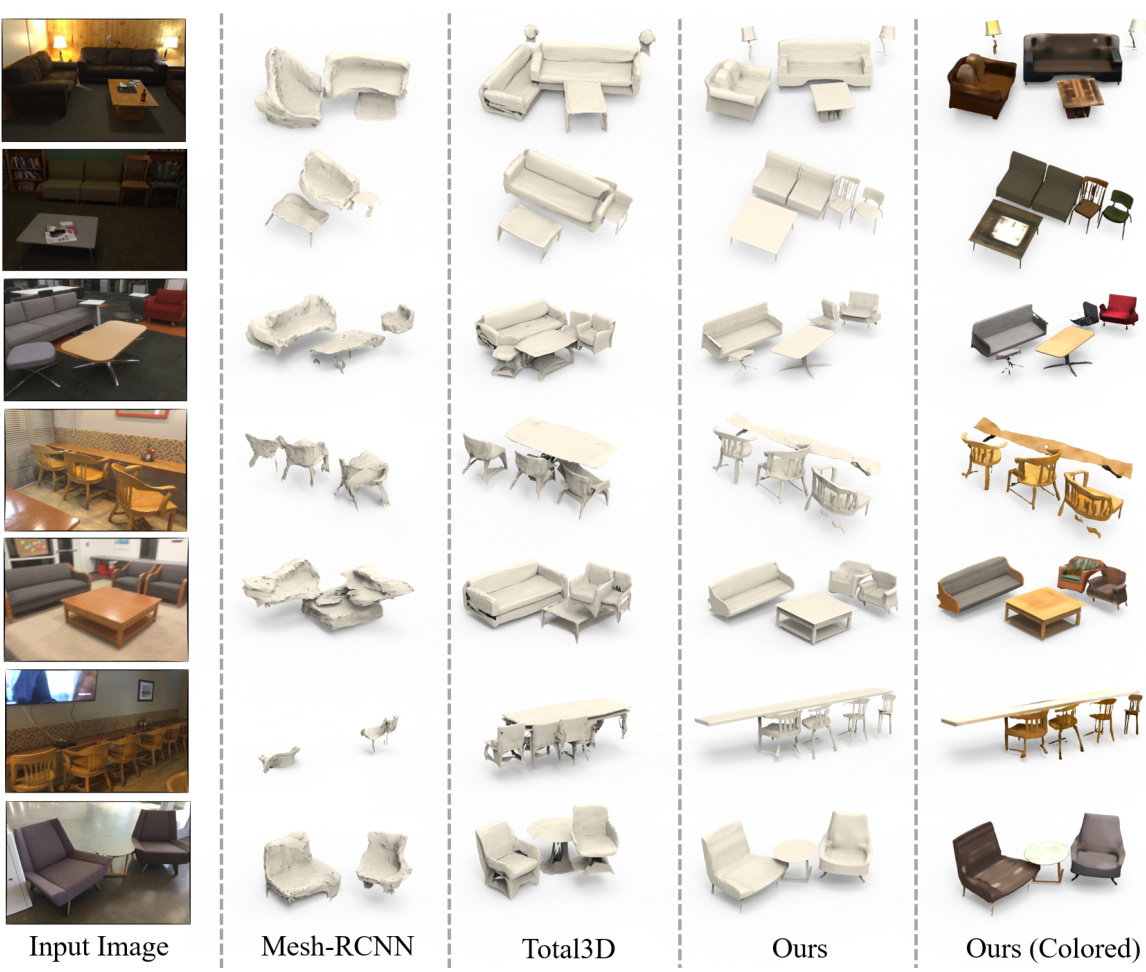

This figure compares the scene reconstruction results from four different methods: Mesh R-CNN, Total3D, PanoRecon, and the proposed ‘Ours’ method. Each column shows the input image, the reconstruction from each method, and the ground truth. The ‘Ours (Colored)’ column shows a colored version of the proposed method’s reconstruction. The figure demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed method in generating accurate and detailed 3D scene reconstructions from single images, especially when compared to the other methods which tend to produce incomplete or less accurate results.

This figure compares the scene reconstruction results from different methods (Mesh R-CNN, Total3D, PanoRecon, and the proposed Deep Prior Assembly) on the 3D-Front dataset. Each row shows the input image, followed by the 3D reconstructions generated by each method, and finally the ground truth 3D model. The figure visually demonstrates the superior performance of the proposed method in accurately reconstructing the scene, especially in terms of detail and completeness.

This figure shows an example of how the proposed pipeline improves the quality of 2D instance images before generating 3D models. A corrupted 2D instance is first enhanced and inpainted using Stable Diffusion, generating multiple versions. OpenCLIP then filters these, selecting the top three most similar to the original. Finally, Shap-E generates 3D models from these improved images, resulting in significantly better and more complete models than those generated from the original, low-quality image.

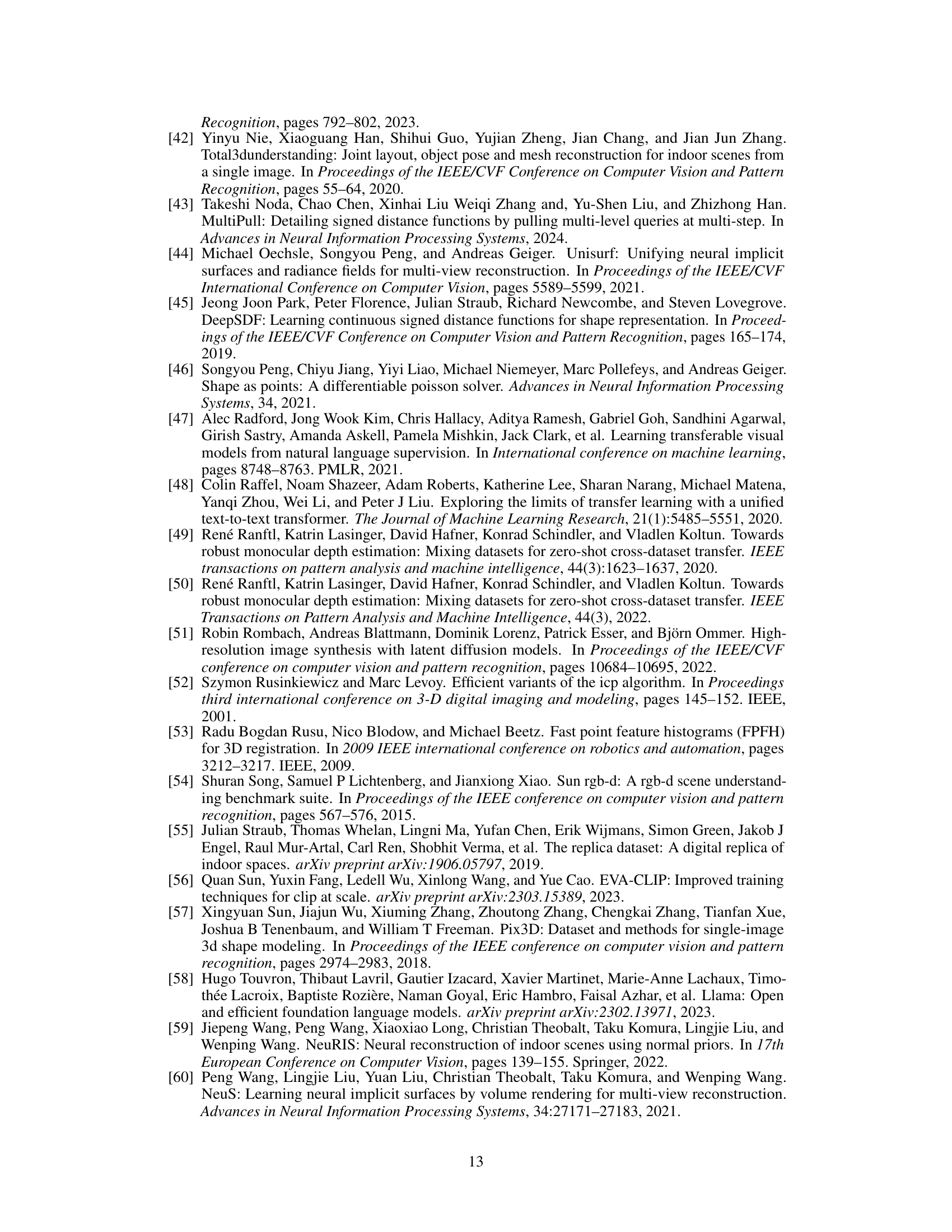

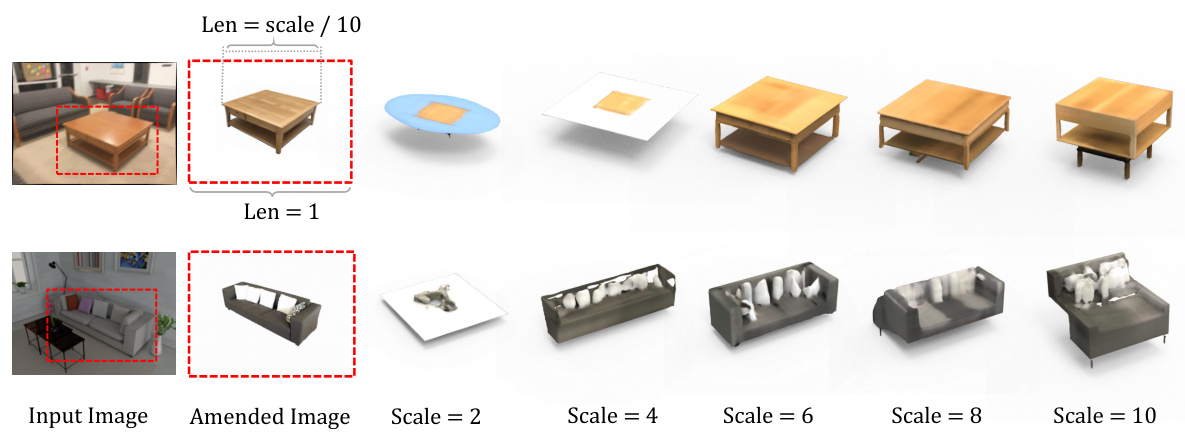

This figure shows an ablation study on how the scale of an instance in an image affects the quality of 3D model generation using the Shap-E model. Two examples are shown: a coffee table and a sofa. For each, the original image segment is shown, along with the results of enhancing/inpainting that segment, and then multiple 3D generations using different scales for the input instance image. This demonstrates the model’s sensitivity to input scale and highlights the optimal scaling used in the paper.

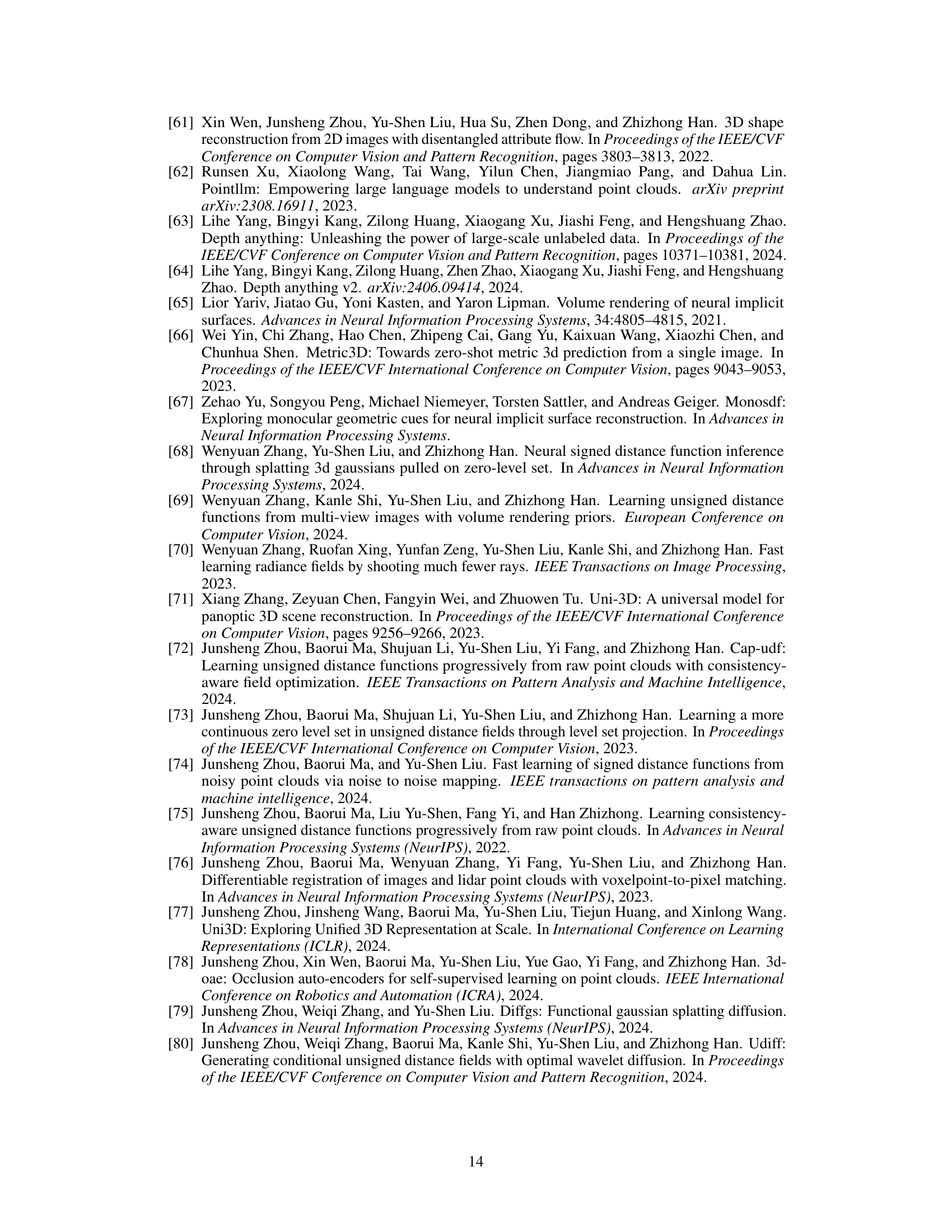

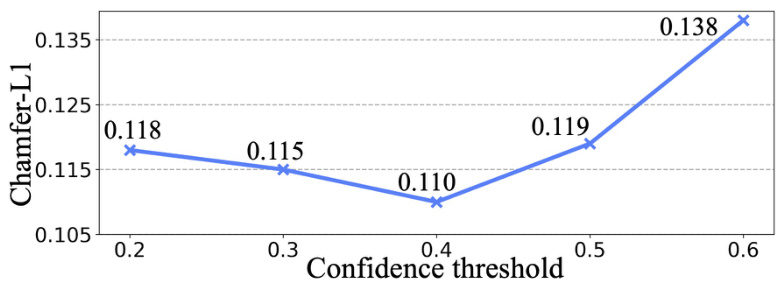

The figure shows the ablation study on the confidence threshold (σ) used in the ‘Detect and Segment 2D instances’ step of the deep prior assembly framework. The x-axis represents different confidence thresholds, and the y-axis shows the corresponding Chamfer-L1 distance, a metric used to evaluate the accuracy of 3D scene reconstruction. The plot indicates that selecting an appropriate threshold is crucial for optimal performance. A threshold that is too high may discard many instances, leading to incomplete scene reconstructions, while a threshold that is too low might include inaccurate instances, causing errors in the final reconstruction.

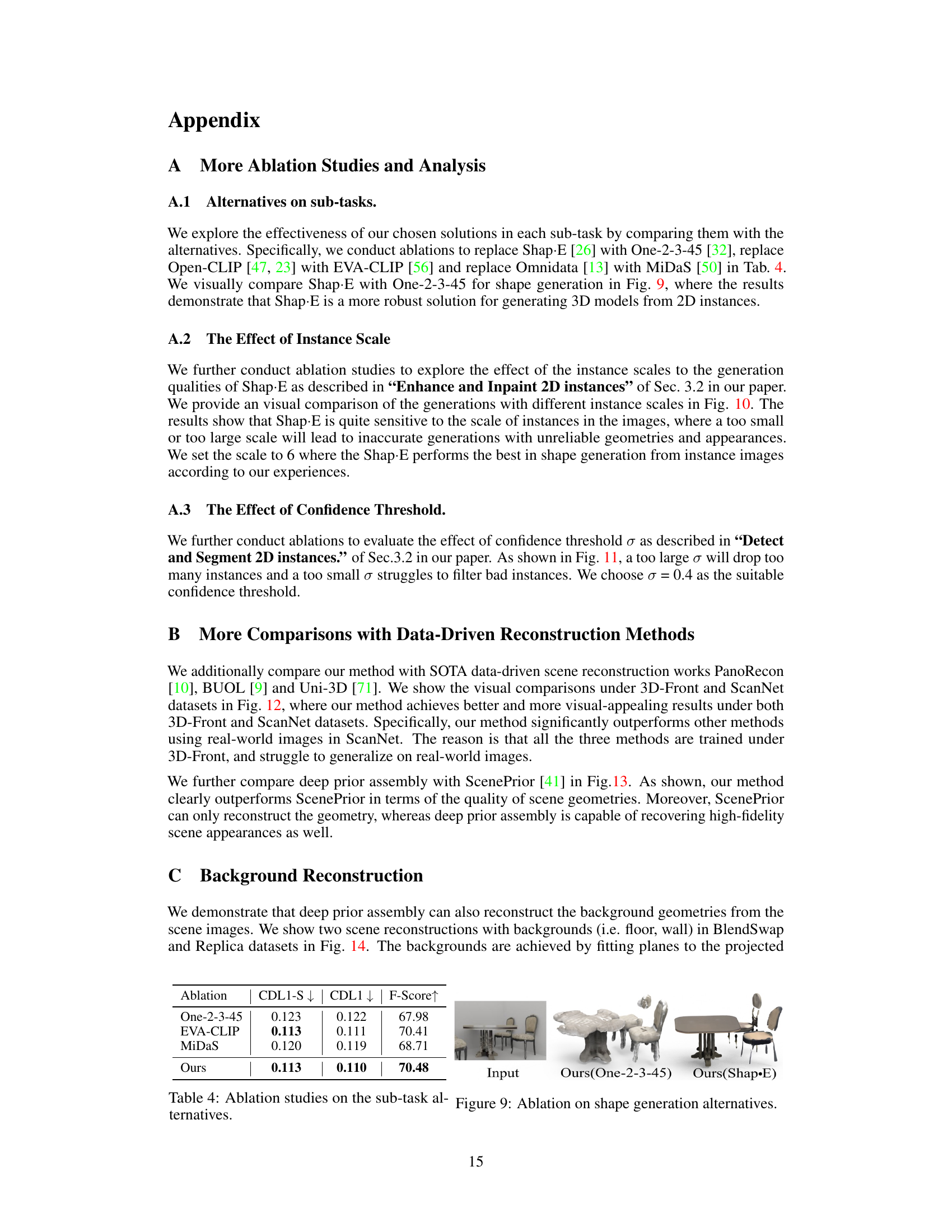

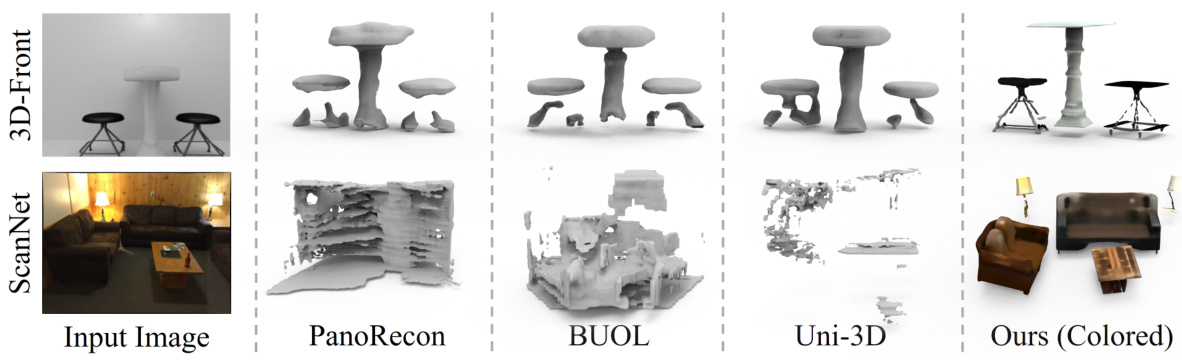

This figure compares the results of scene reconstruction from single images using different methods including PanoRecon, BUOL, Uni-3D, and the proposed method. The top row shows the results on the 3D-Front dataset, and the bottom row shows the results on the ScanNet dataset. For each dataset, it shows the input image, and then reconstruction results from the three comparison methods, followed by the results of the proposed method (colored). The comparison highlights the superior performance of the proposed method in terms of accuracy and visual quality.

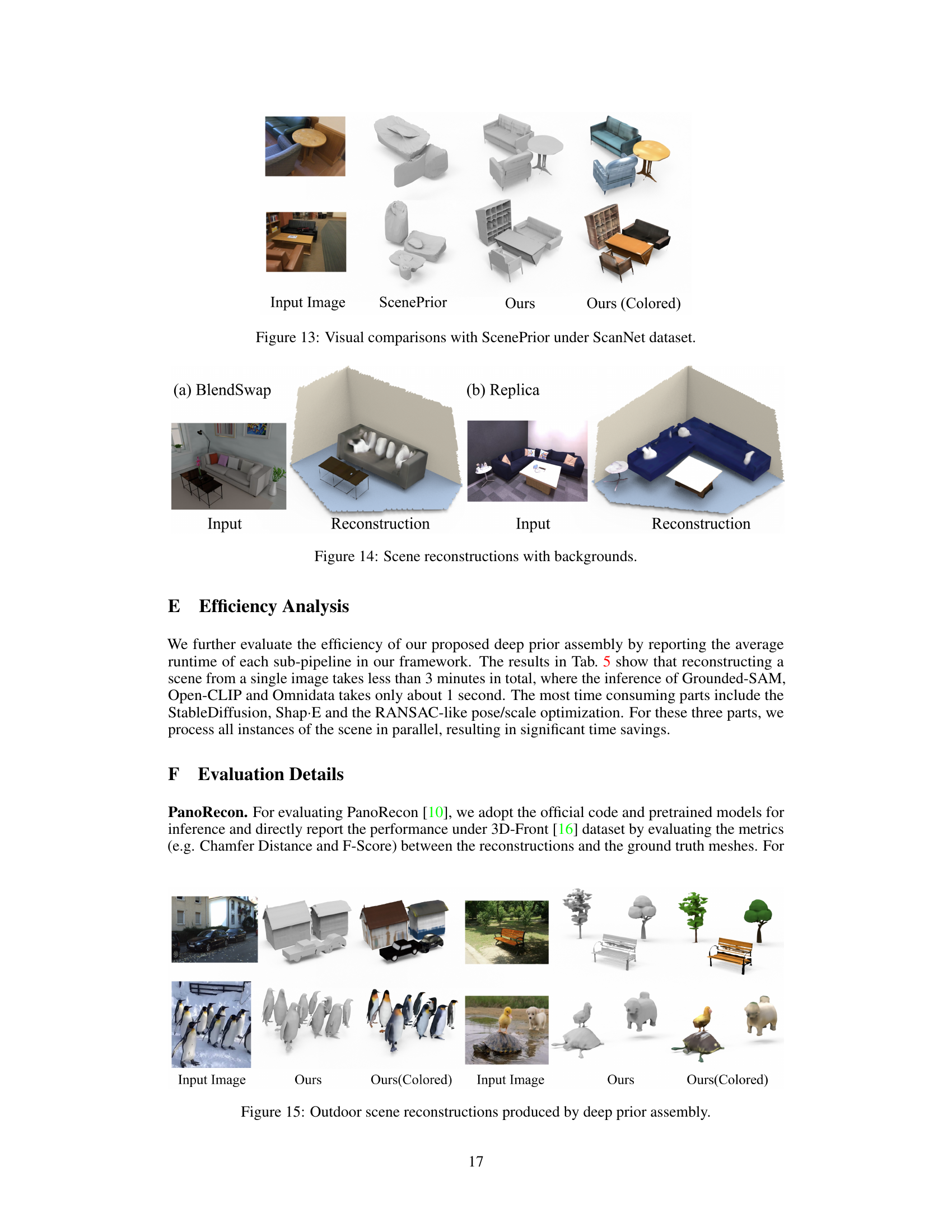

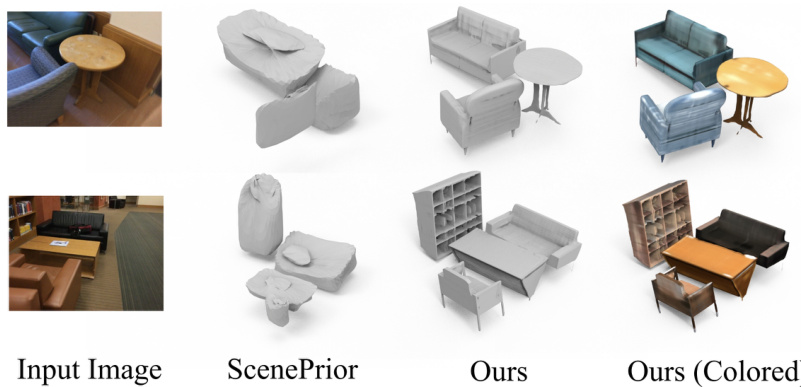

This figure compares the results of scene reconstruction using the proposed deep prior assembly method and the ScenePrior method on the ScanNet dataset. It showcases example images from the dataset, along with the 3D reconstructions generated by each approach. The visual comparison allows for an assessment of the relative accuracy and detail achieved by each method. The ‘Ours (Colored)’ column shows textured 3D models generated by the proposed method.

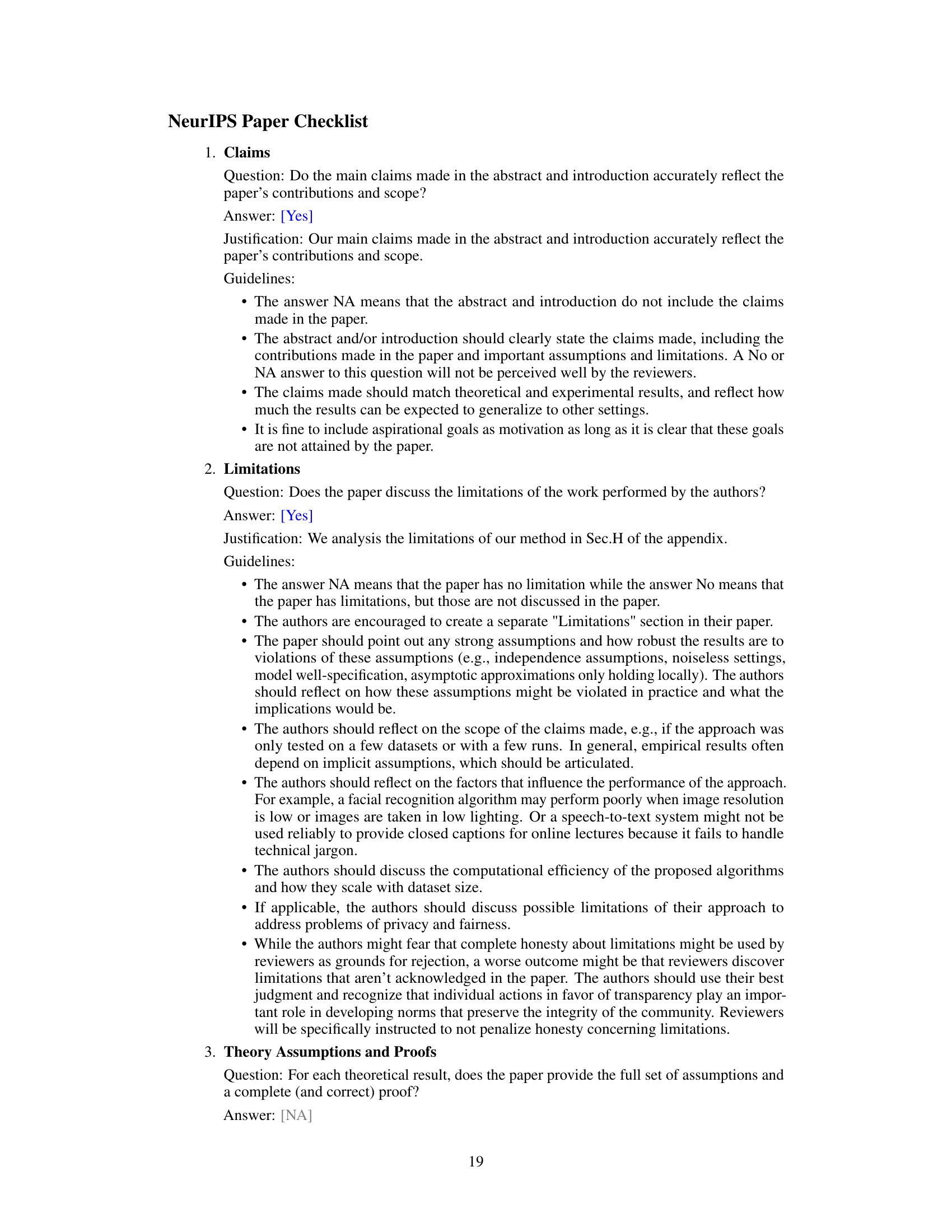

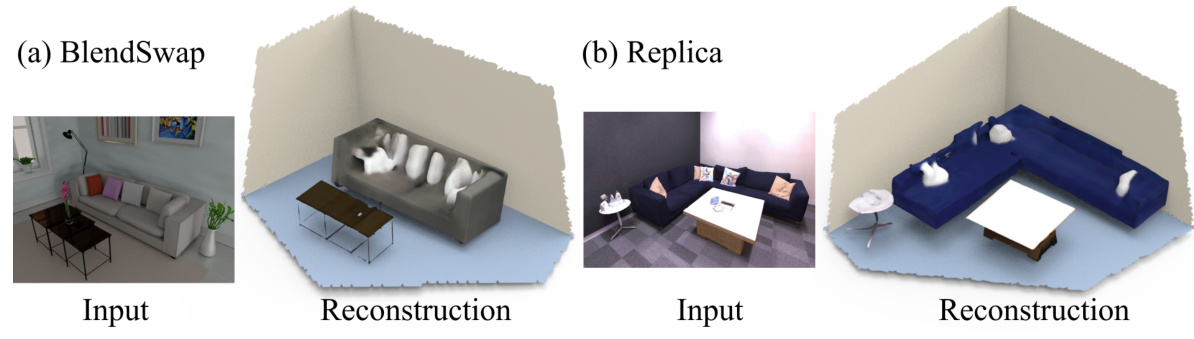

This figure shows two examples of scene reconstruction results by the proposed deep prior assembly method. The figure contains two subfigures: (a) BlendSwap and (b) Replica. Each subfigure shows the input image, and the corresponding reconstructed 3D scene with backgrounds (e.g., walls and floors). The reconstructions demonstrate the method’s ability to recover not just the main objects in the scene but also the background geometry, creating more complete and realistic 3D models.

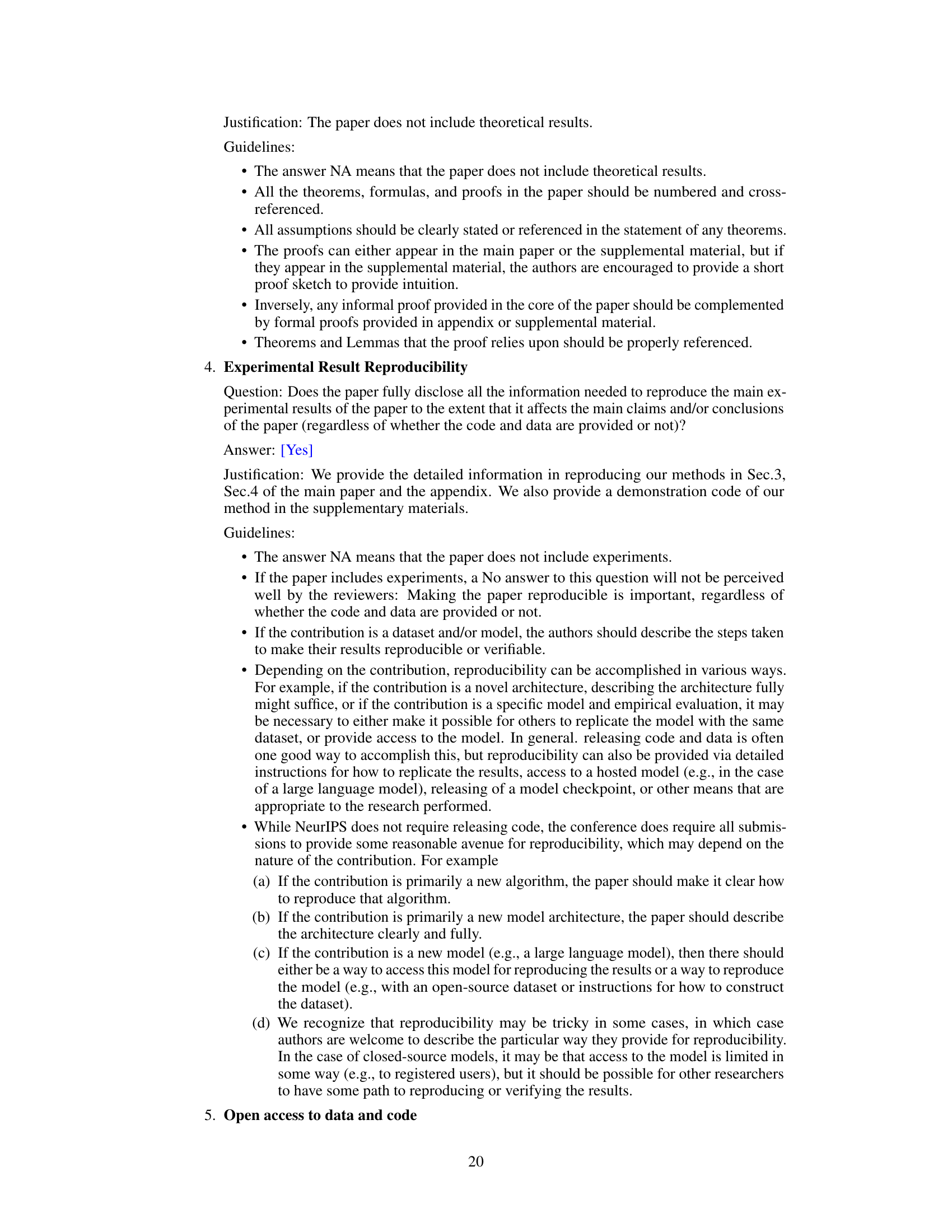

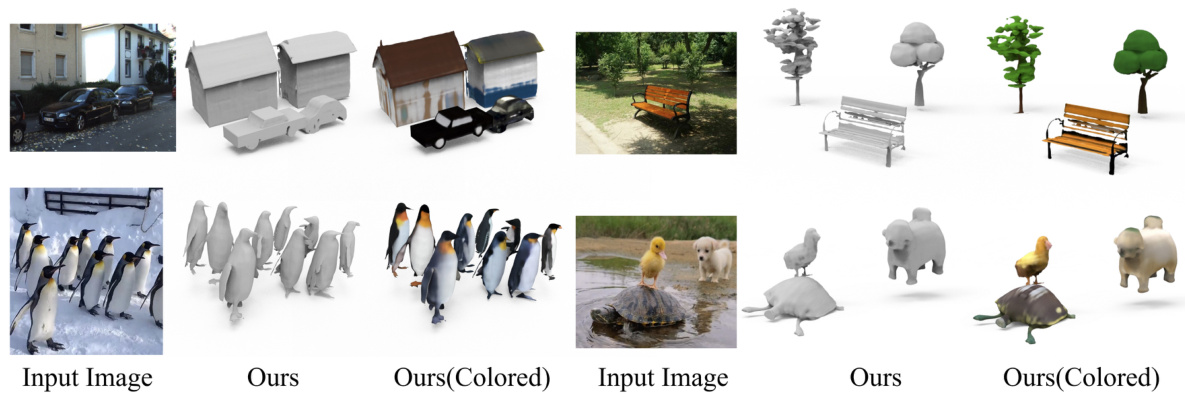

This figure showcases the results of the proposed Deep Prior Assembly method on several outdoor scenes containing complex objects and animals. The figure is divided into two rows, each showing an input image followed by the corresponding reconstruction in grayscale and then color. The results demonstrate the method’s ability to reconstruct diverse outdoor scenes, including a street scene with cars and buildings, a park scene with a bench and trees, and a scene with penguins and a dog sitting on a turtle.

More on tables

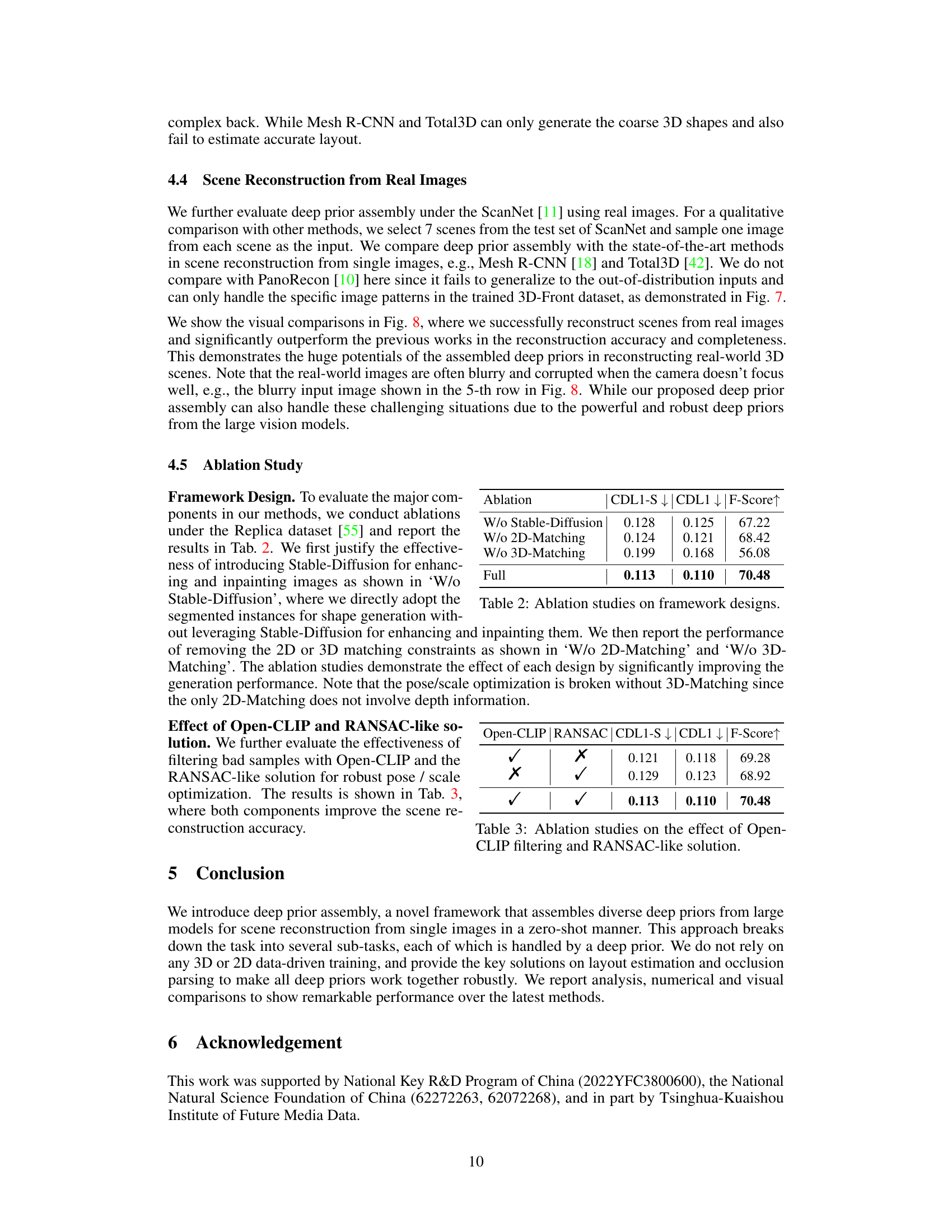

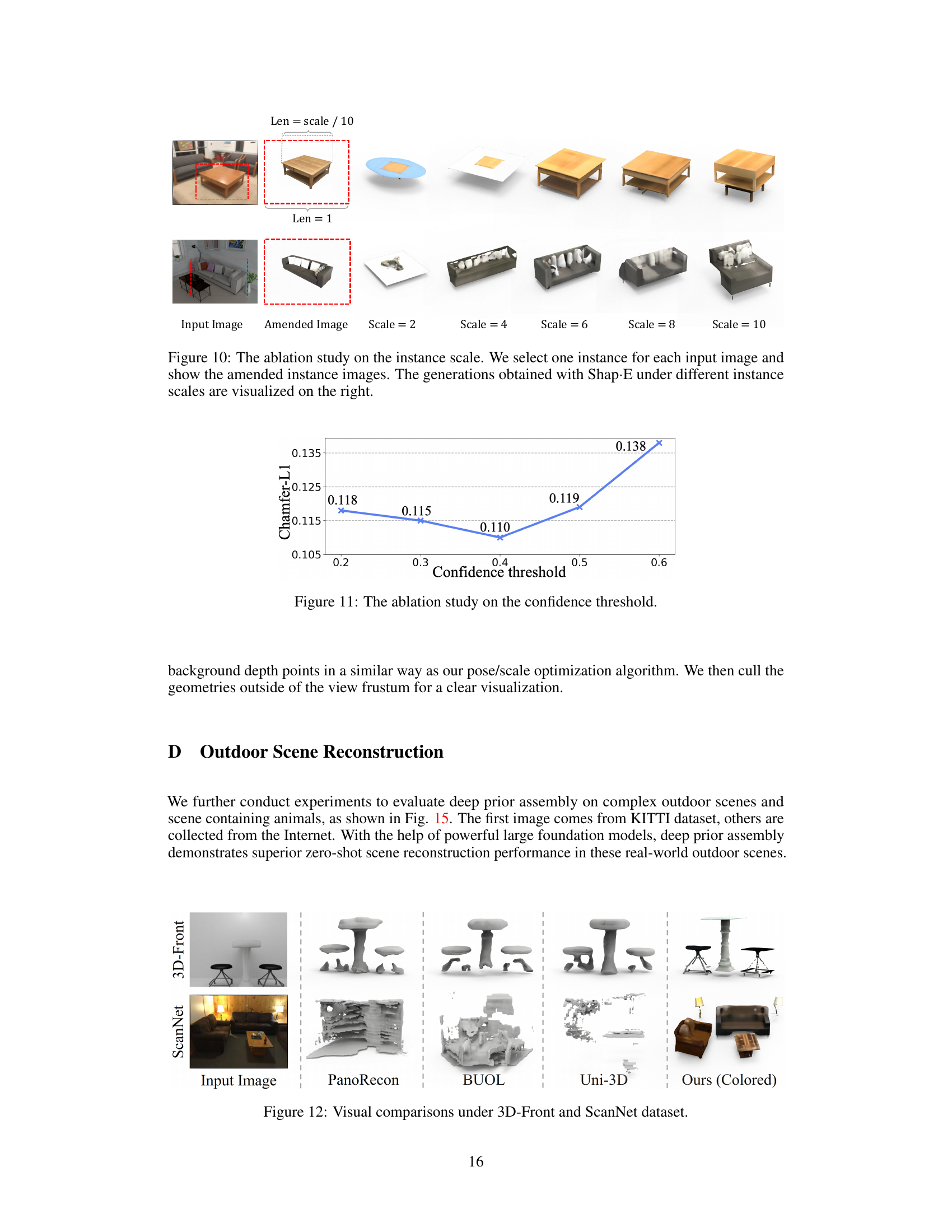

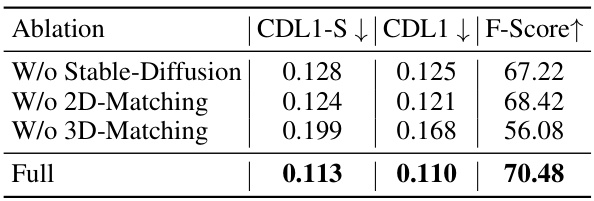

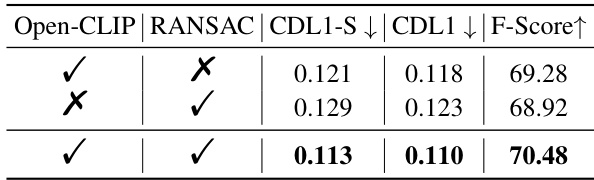

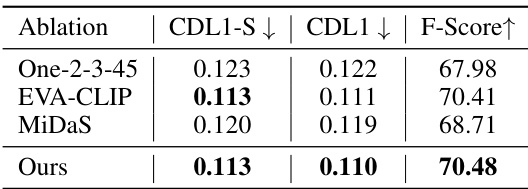

This table presents the ablation study on the framework designs, comparing the performance of the model with different components removed. Specifically, it shows the impact of removing Stable-Diffusion, 2D-Matching, and 3D-Matching on the key evaluation metrics: CDL1-S (single-direction Chamfer Distance), CDL1 (Chamfer Distance), and F-Score. Lower values are better for CDL1-S and CDL1, while higher values are better for F-Score. The ‘Full’ row represents the performance of the complete model.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method against three other state-of-the-art methods (Mesh R-CNN, Total3D, and PanoRecon) on the task of 3D scene reconstruction from a single image. The evaluation metrics used are Chamfer Distance (CDL1), single-direction Chamfer Distance (CDL1-S), and F-Score. Lower CDL1 and CDL1-S values indicate better performance (closer reconstruction to the ground truth), while a higher F-Score indicates better performance. The results are presented for three different datasets (3D-Front, BlendSwap, Replica).

This table presents a comparison of different methods for scene reconstruction from single images. The methods are evaluated using three metrics: CDL1-S (single-direction Chamfer Distance from generated to ground truth), CDL1 (Chamfer Distance), and F-Score. Lower CDL1 and CDL1-S values indicate better performance, while higher F-Score values indicate better performance. The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed method, ‘Ours’, compared to existing state-of-the-art techniques (Mesh R-CNN, Total3D, and PanoRecon).

This table compares the performance of the proposed Deep Prior Assembly method against other state-of-the-art scene reconstruction methods on three different datasets (3D-Front, Replica, and BlendSwap). The comparison is based on three metrics: CDL1-S (single-direction Chamfer Distance from generated to ground truth), CDL1 (Chamfer Distance), and F-Score. Lower CDL1 and CDL1-S values indicate better accuracy, while a higher F-Score suggests better overall performance. The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed method across all datasets and metrics.

Full paper#