↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Domain-specific languages (DSLs) improve code readability and maintainability but require developers to rewrite code. While Large Language Models (LLMs) have shown promise in automatic code transpilation, they lack functional correctness guarantees. Existing verified lifting tools, which rely on program synthesis to find functionally equivalent programs in the target language, are often specialized for specific source-target languages or require significant domain expertise to be efficient.

This paper introduces LLMLIFT, an LLM-based approach for building verified lifting tools. LLMLIFT uses LLMs to translate programs into an intermediate representation (Python) and generate proofs of functional equivalence. The approach demonstrates improved performance compared to existing symbolic tools for four different DSLs, significantly reducing development effort and achieving higher benchmark success rates. The key contribution is a novel application of LLMs that leverages their reasoning capabilities to automate the verified lifting process, which was previously a complex and manual task.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with domain-specific languages (DSLs). It demonstrates a novel approach to building verified lifting tools using large language models (LLMs), a significant advancement that addresses existing challenges in code transpilation. The findings have implications for compiler design, program synthesis, and formal verification, opening up new research directions and offering a potentially more efficient and scalable method for building DSL compilers.

Visual Insights#

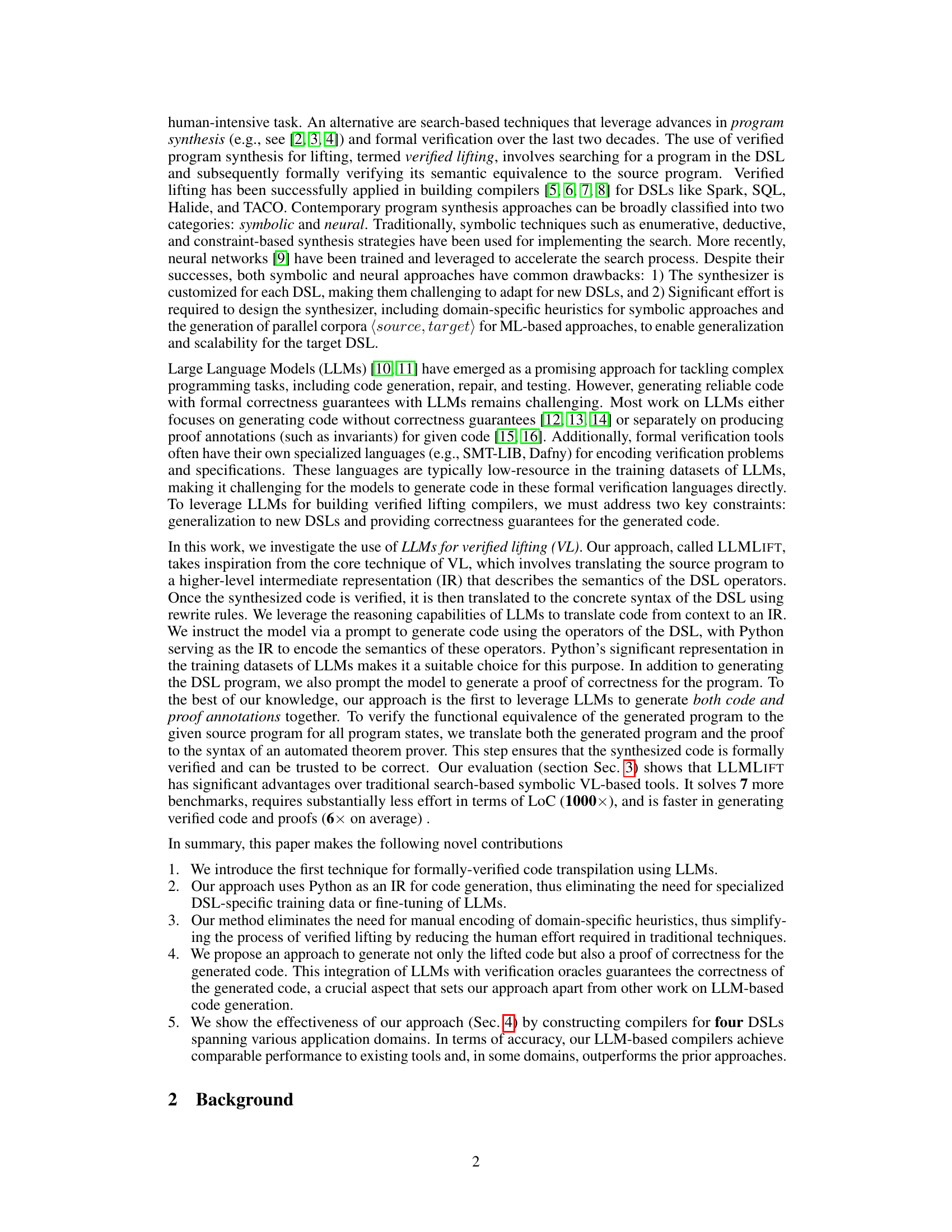

This figure shows an example of verified lifting (VL). The left side (a) presents sequential C++ code for a matrix addition operation. The right side (b) shows the equivalent representation in an intermediate representation (IR), which uses a Domain-Specific Language (DSL) to represent the operations in a higher-level, more abstract way, ignoring implementation details. This IR serves as a bridge between the source code and the target DSL, enabling more efficient compilation and verification.

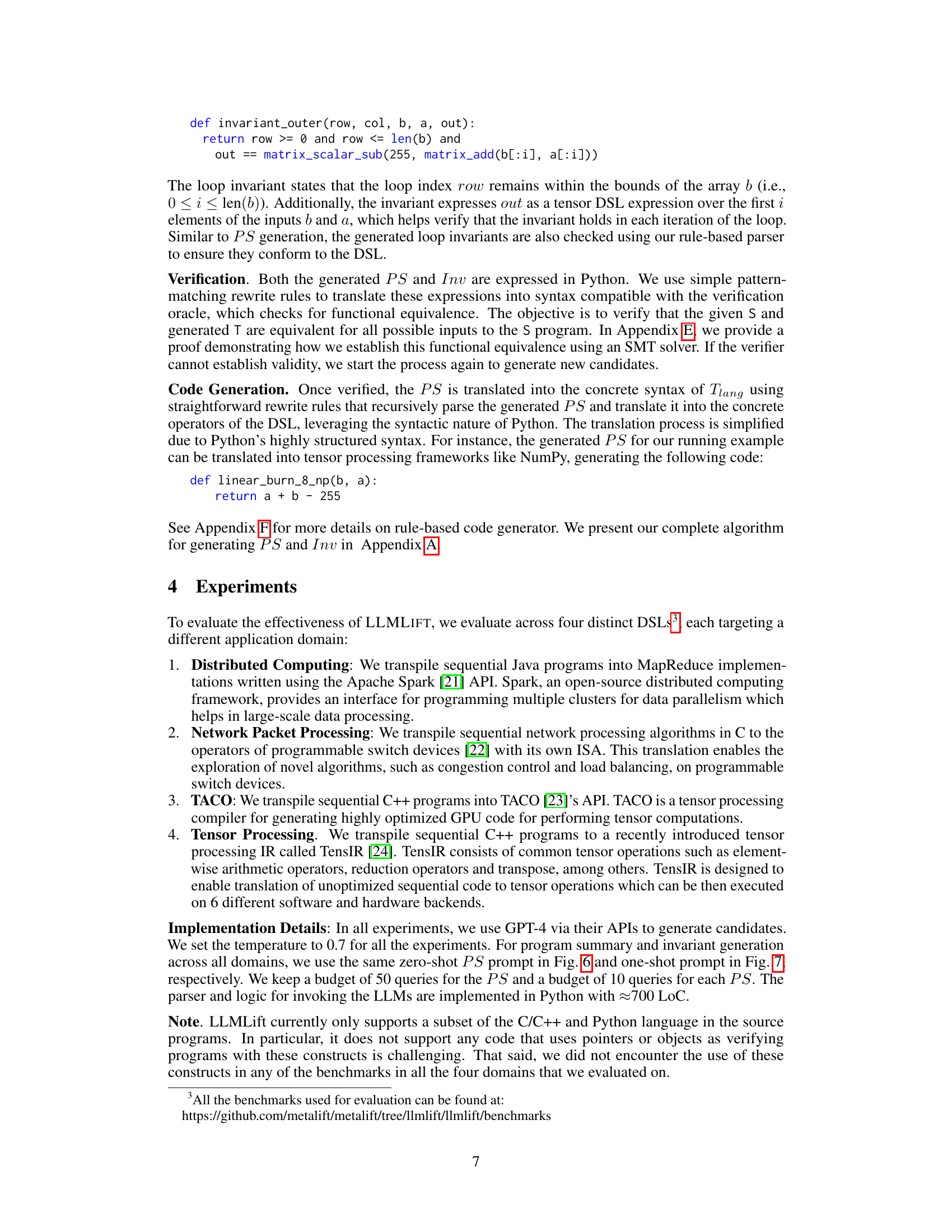

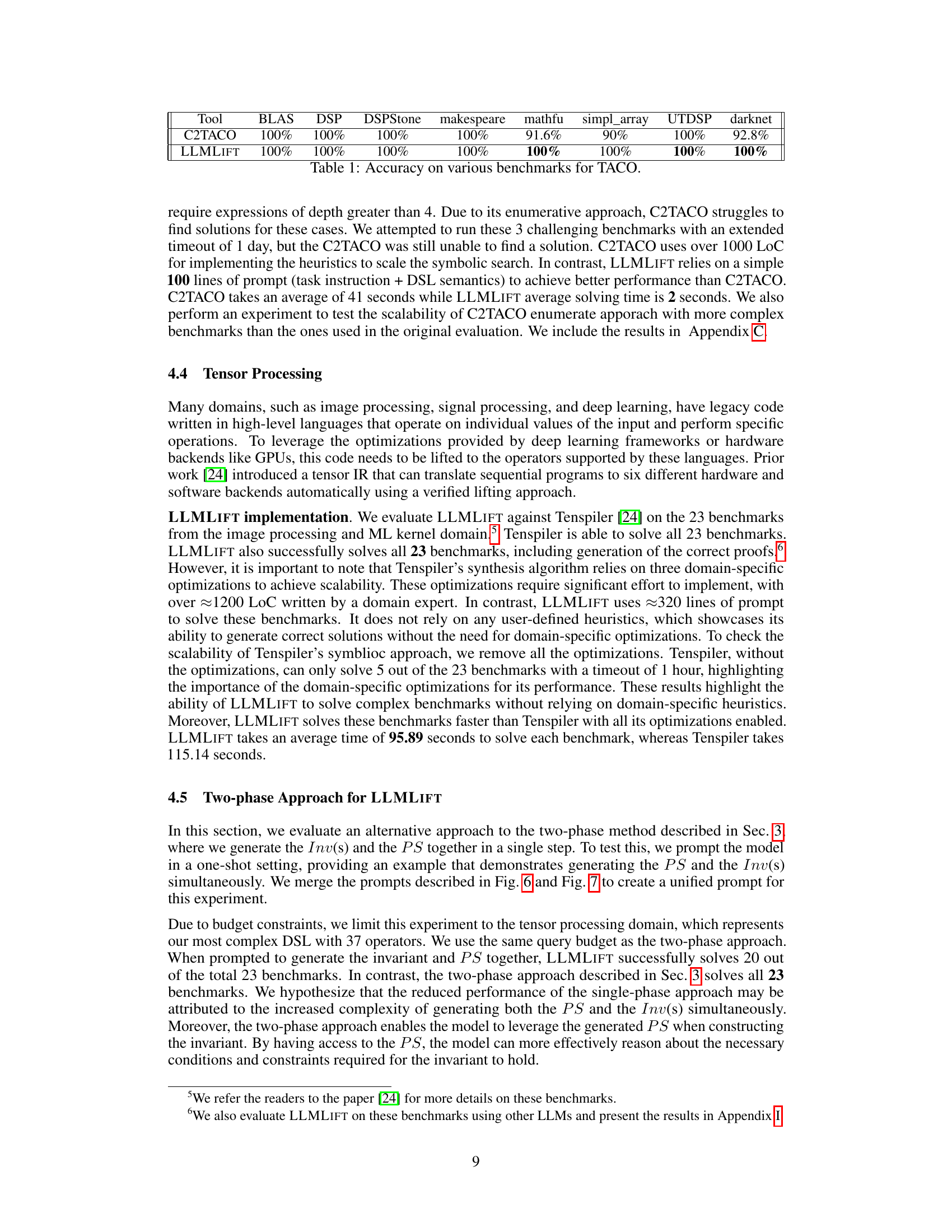

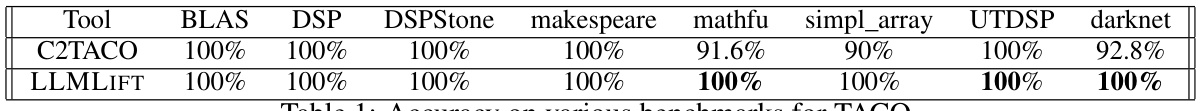

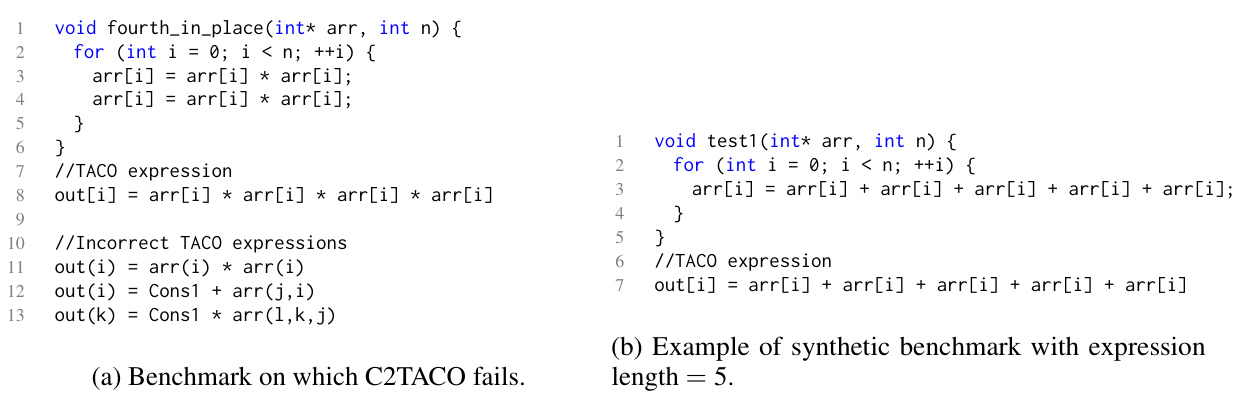

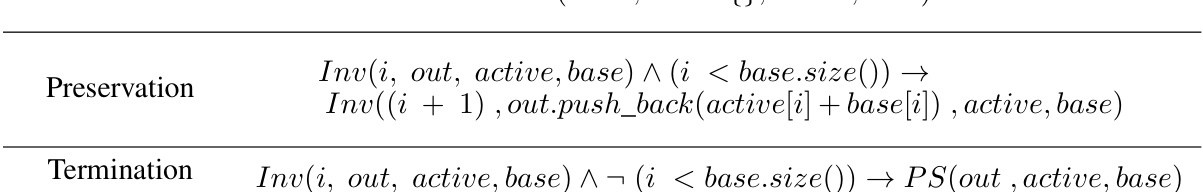

This table presents the accuracy results of two different tools, C2TACO and LLMLIFT, when applied to various benchmarks designed for the TACO tensor processing compiler. Each benchmark tests different aspects of the compiler’s capabilities. The accuracy is shown as a percentage for each benchmark, indicating the successful rate of each tool in solving the task. The results demonstrate the performance comparison between the existing tool (C2TACO) and the proposed LLM-based approach (LLMLIFT).

In-depth insights#

LLM-based VL#

The section on “LLM-based VL” likely details a novel approach to verified lifting (VL) using large language models (LLMs). Instead of traditional symbolic or neural methods for program synthesis in VL, this approach leverages an LLM’s ability to reason about programs. The core idea is to use the LLM to translate source code into an intermediate representation (IR), such as Python, which is then used to generate equivalent code in the target domain-specific language (DSL). This approach addresses limitations of existing VL methods, such as the need for DSL-specific training data or significant domain expertise. A key advantage is the LLM’s capacity to generalize across different DSLs, reducing the effort required to build verified lifting tools for new domains. The method likely involves prompting the LLM to not only generate the DSL code but also provide formal proofs of functional equivalence, possibly leveraging the LLM’s ability to generate proof annotations directly. This addresses the critical issue of correctness guarantees, a major limitation of previous LLM-based code transpilation methods. The evaluation likely shows that this LLM-based approach outperforms previous methods in speed, scalability, and requires significantly less manual effort for construction. The use of a high-level IR like Python, extensively used in LLM training data, contributes to improved generalization and efficiency.

Python as IR#

The choice of Python as an intermediate representation (IR) in the LLMLIFT framework is a strategic decision driven by several factors. First, Python’s widespread use and prevalence in large language model (LLM) training datasets makes it an ideal choice for code generation. LLMs are significantly more proficient at generating syntactically correct Python code compared to domain-specific languages (DSLs), which often lack the substantial datasets needed for effective LLM training. This reduces the need for specialized fine-tuning or training data for each DSL, significantly simplifying the process and increasing the approach’s scalability. Second, Python’s relatively clear and expressive syntax simplifies both the generation of code (program summary, PS) and the verification process. The use of Python as IR allows for easier translation to the target DSL syntax through relatively straightforward pattern-matching and rewrite rules, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of the transpilation process. This makes the system significantly less reliant on complex heuristics, a major advantage over traditional symbolic methods. However, this reliance on Python as a universal IR does present limitations. The Python IR needs to faithfully represent all the nuances of the target DSL operators. Furthermore, this choice might limit the direct applicability to DSLs that don’t naturally map to Python’s semantic structure. Therefore, while highly beneficial for enhancing efficiency and scalability, the choice of Python as IR is a design decision that involves a trade-off between generalization capabilities and direct applicability to specific DSLs.

Few-shot Learning#

The concept of few-shot learning in the context of verified code transpilation using LLMs is crucial. It addresses the challenge of adapting large language models to various domain-specific languages (DSLs) without extensive fine-tuning, which is often impractical due to limited training data for niche DSLs. The approach leverages the ability of LLMs to generalize from a small set of examples, providing the model with the semantics of DSL operators via an intermediate representation (IR), such as Python, which is rich in training data for LLMs. This approach facilitates the generation of program summaries (PS) and invariants (Inv) within the IR by presenting few examples to the model. By successfully demonstrating how this approach can generate PS and Invs for diverse DSLs (Spark, SQL, TACO, etc.), this study highlights the potential of few-shot learning to significantly reduce the effort and time required to build verified lifting tools, improving overall code transpilation efficiency while maintaining correctness guarantees.

Benchmark Results#

A thorough analysis of benchmark results in a research paper necessitates a multifaceted approach. Firstly, it’s crucial to understand the selection criteria for the benchmarks: were they chosen to represent typical real-world scenarios, or were they more focused on highlighting specific strengths of the proposed method? The diversity of the benchmarks is also critical; if the benchmarks are too similar or narrowly focused, the results may not generalize well. Then, the metrics used to evaluate performance should be carefully examined. Were these metrics appropriate for the task, and were they interpreted correctly? A comparison with existing state-of-the-art methods is vital to determine the significance of any improvements achieved, along with error bars to indicate the level of statistical confidence. Finally, the discussion of limitations is crucial for a balanced interpretation: What factors influenced the results, and how might these factors limit generalizability? Reproducibility is also essential; clear descriptions of experimental setups are necessary to allow readers to replicate the results.

Future Work#

The paper’s core contribution is an LLM-based approach to verified code transpilation, showcasing promising results. Future work should prioritize expanding the range of supported DSLs, moving beyond the four explored in this study to encompass a broader array of application domains. Investigating the scalability of the approach to larger programs and more complex DSLs is crucial. Addressing the current limitations, such as the reliance on Python as the IR, is also important. While Python’s wide representation in LLM training data proved beneficial, exploring other more suitable intermediate representations might enhance performance and compatibility. Further research should involve evaluating the approach’s robustness to noisy or incomplete source code, better handling of more complex language constructs beyond side-effect-free functions, and incorporating more sophisticated verification techniques. Finally, a thorough analysis of the computational efficiency and resource usage of the LLM-based method compared to traditional symbolic techniques is warranted, ensuring its practical applicability beyond the tested benchmarks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

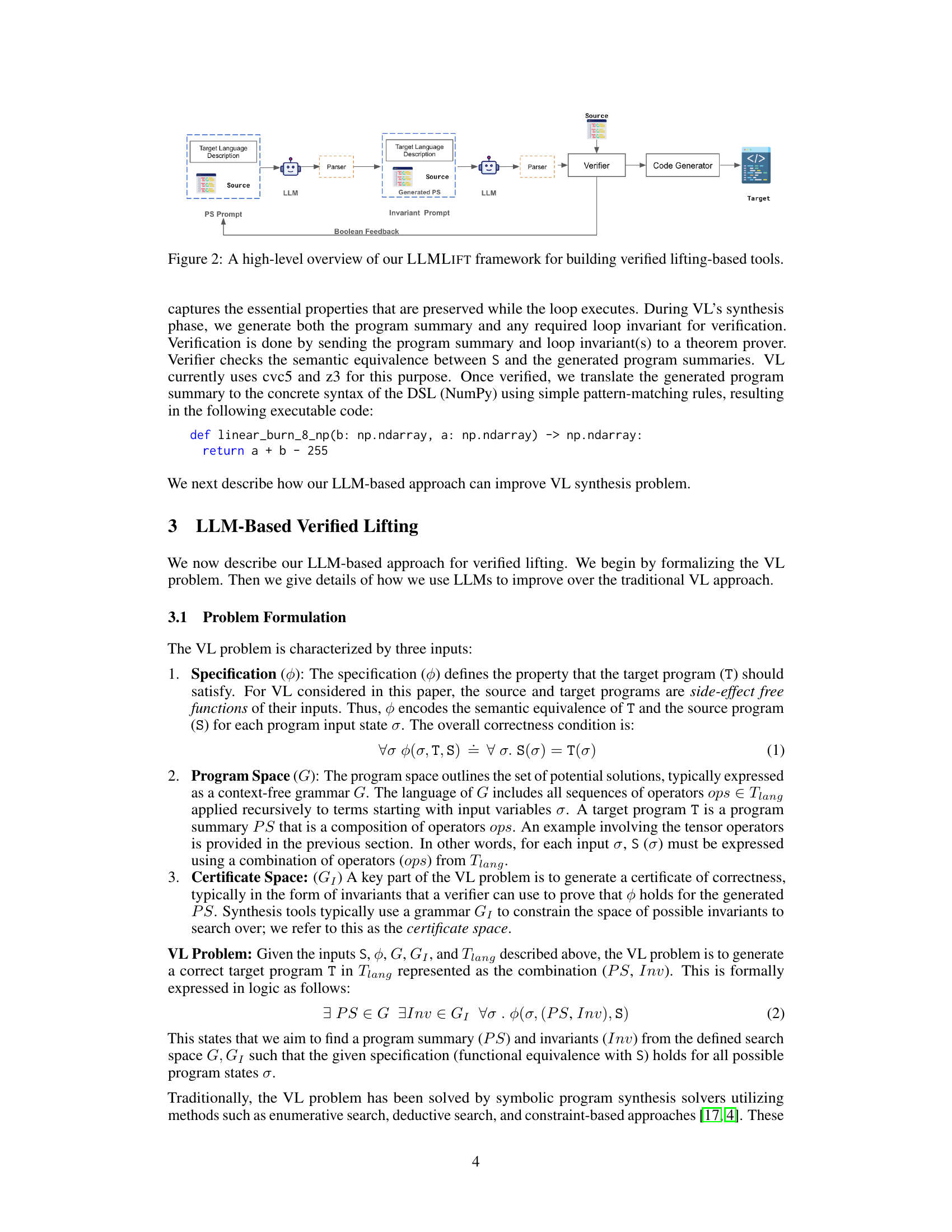

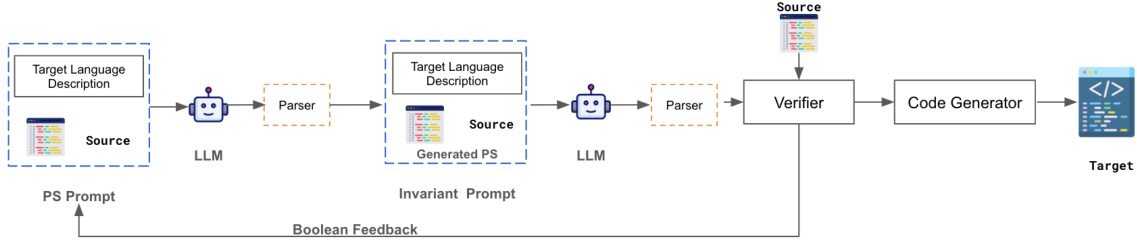

The figure illustrates the LLMLIFT framework, an LLM-based approach for building verified lifting tools. It shows the workflow from source code to a verified target DSL code. The process includes prompting an LLM to generate both program summaries (PS) and loop invariants, verifying the equivalence using a theorem prover, and generating the final target code. The framework incorporates a parser for checking the syntactic correctness of the LLM’s output, as well as a feedback loop for iterative refinement.

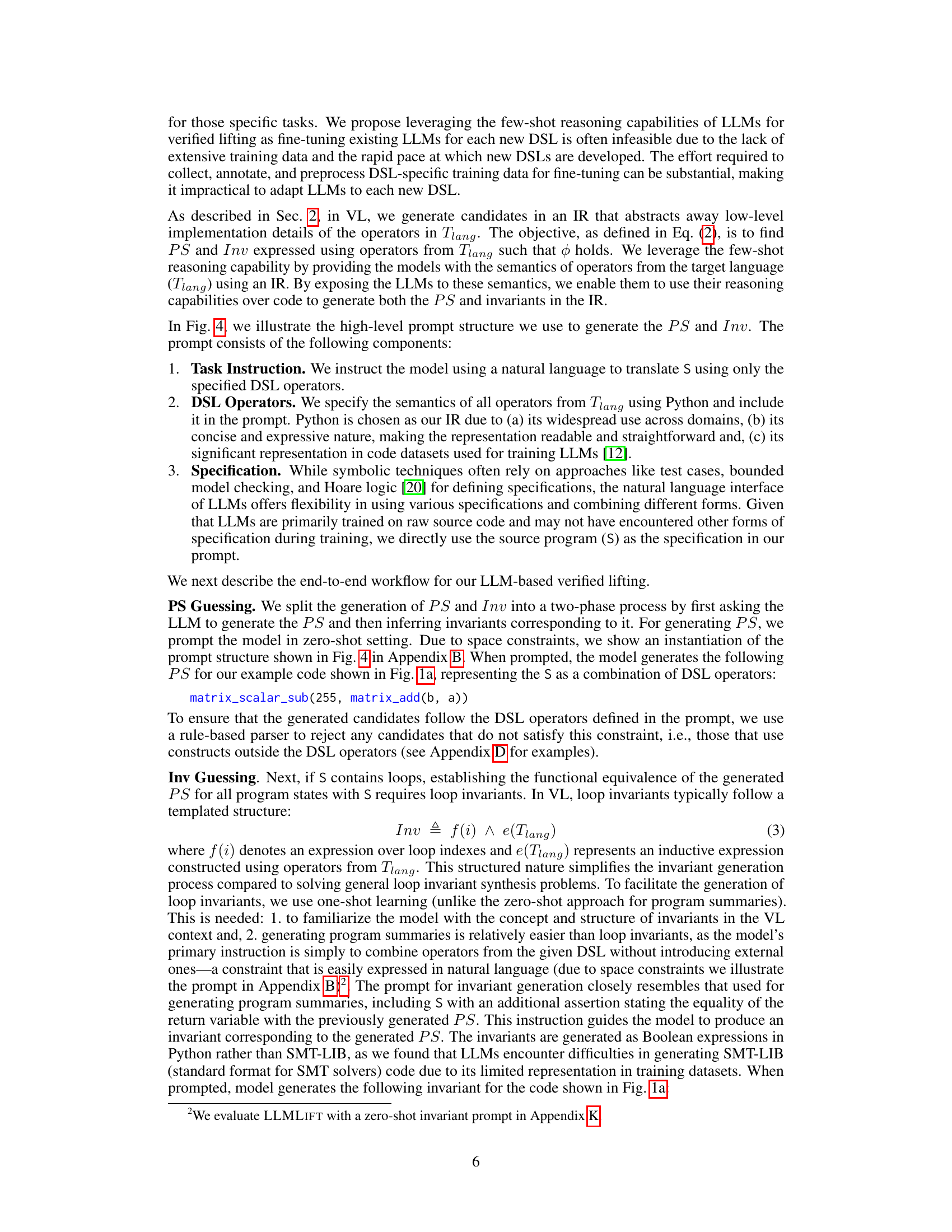

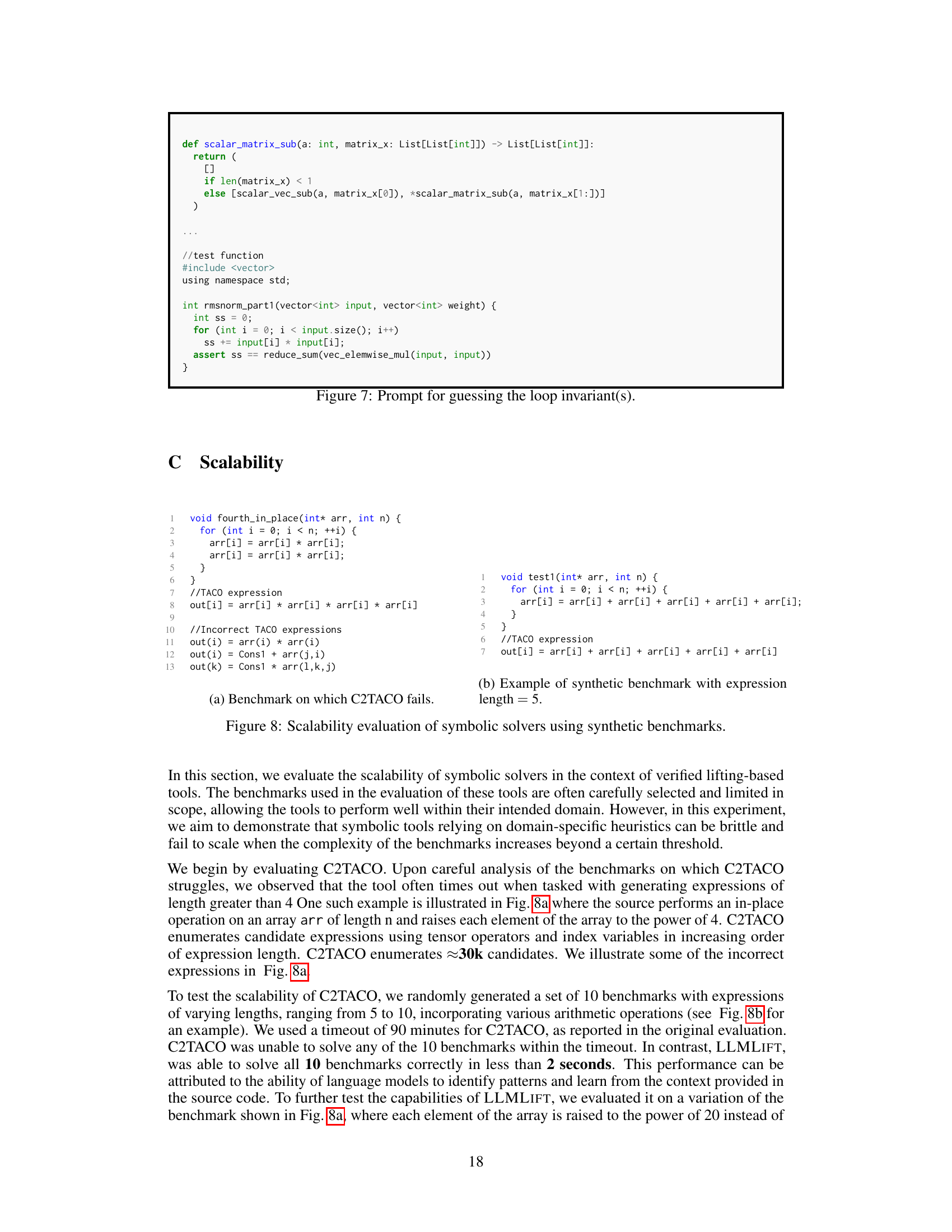

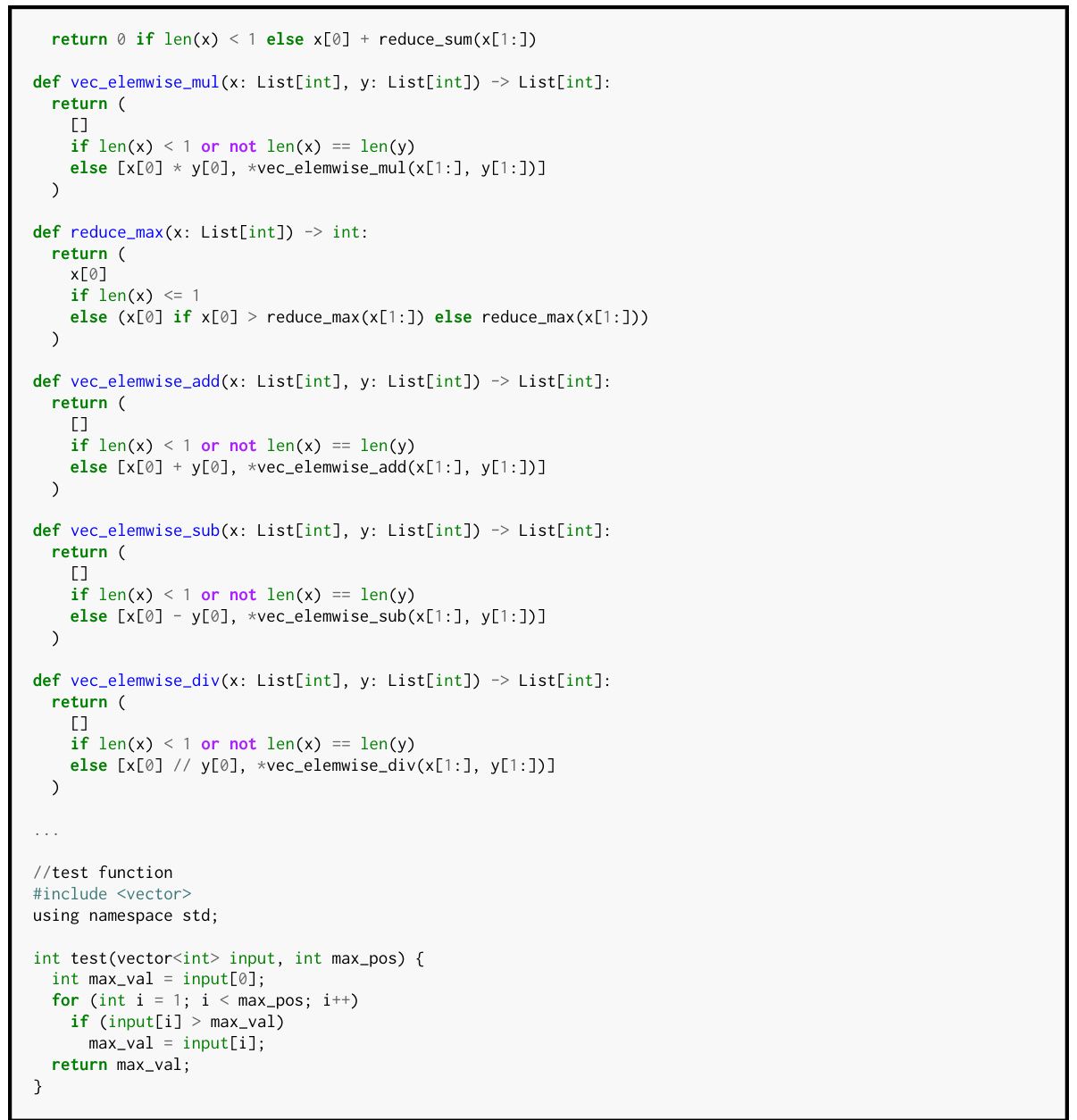

The figure shows the prompt structure used by the authors in their experiments. The prompt consists of four main components: 1. Instructions: providing a high-level task description for the model. 2. DSL Semantics: specifying the semantics of the operators in the target DSL using Python as the intermediate representation (IR). 3. Specification: providing the source code as a specification for the desired outcome. 4. Source Program: providing the source code that needs to be translated to the target language.

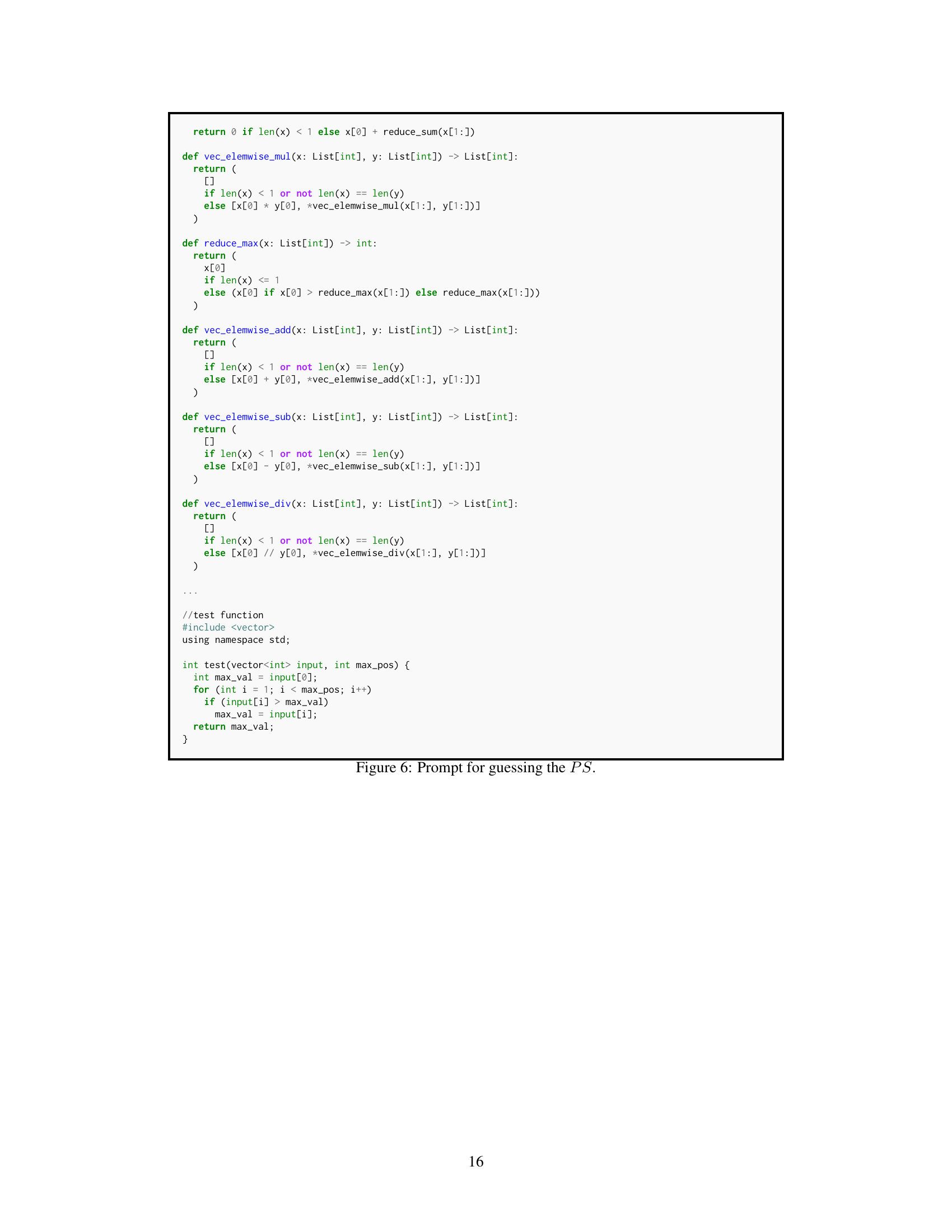

This figure shows the structure of the prompt used to generate the program summary (PS) and invariants (Inv). The prompt includes a task description, the semantics of DSL operators (expressed in Python), and the source program. This structure is designed to guide the language model in generating code that is both syntactically correct and semantically equivalent to the source code.

This figure demonstrates an example of verified lifting (VL) where a sequential C++ code is transpiled into a tensor processing framework’s DSL (like PyTorch or NumPy). It shows the original sequential C++ code (a) and the equivalent code written using the DSL’s operators, represented in a higher-level intermediate representation (IR) using Python (b). The IR serves as a functional description of the DSL, abstracting away implementation details and simplifying the translation process. The process involves lifting the C++ code to Python operators and then translating the Python code to the DSL’s syntax.

This figure shows a sequential C++ code (on the left) which performs element-wise addition of two matrices followed by scalar subtraction. The corresponding code (on the right) in an intermediate representation (IR) using a domain-specific language (DSL) is shown. The IR is an intermediate step in verified lifting, which is used to translate code from one language to another while ensuring functional equivalence. Python is used as the IR language in the paper’s approach, and the figure illustrates how the source code’s functionality is expressed using the DSL operators represented in the IR. This allows for verifying semantic equivalence during the translation process.

This figure shows an example of how LLMLIFT works. It takes a C++ function as input, translates it into an intermediate representation (IR) using Python, generates a program summary (PS) and invariants (Inv) using LLMs, verifies that the PS is functionally equivalent to the source code using a theorem prover, and finally translates the PS into the target language (Apple MLX in this case).

The figure shows the structure of the prompt used in the LLMLIFT framework. It’s designed to guide LLMs in generating program summaries (PS) and loop invariants (Inv). The prompt includes several components: a task description, a section for DSL semantics and operators, the source program, and instructions.

More on tables

This table presents the accuracy results of LLMLIFT and C2TACO on various benchmarks for the TACO tensor compiler. It shows that both tools achieve high accuracy (100%) on most benchmarks, highlighting their effectiveness in generating correct TACO code from C++. However, there are a few benchmarks where C2TACO’s accuracy is lower, which are likely more challenging for its enumerative approach. LLMLIFT achieves comparable or better accuracy compared to C2TACO even in these more challenging benchmarks.

This table presents the accuracy results of LLMLIFT and C2TACO on various benchmarks for the TACO tensor processing compiler. It shows that both methods achieve 100% accuracy on most benchmarks, indicating strong performance in generating equivalent TACO code. However, C2TACO struggles with a small number of more complex benchmarks, whereas LLMLIFT consistently achieves high accuracy even on those challenging tasks.

Full paper#