↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Mixture-of-Expert (MoE) models, while powerful, suffer from slow inference due to high communication overhead and complex communication patterns. This paper tackles this issue by analyzing MoE workloads and proposing novel optimization strategies. The inherent inefficiency stems from the gating function and imbalanced load distribution across experts, leading to underutilized resources and excessive memory consumption.

The researchers propose three optimization techniques: Dynamic gating adapts expert capacity to the number of tokens assigned, reducing communication and computation overheads. Expert buffering utilizes CPU memory to buffer inactive experts, freeing up precious GPU memory. Load balancing addresses the uneven distribution of workloads across experts and GPUs, ensuring optimal resource utilization. These optimizations significantly improve token throughput, reduce memory usage, and enhance the stability and performance of MoE inference.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with Mixture-of-Expert (MoE) models, particularly those dealing with large-scale deployments. It directly addresses the significant challenges of inefficiency and resource constraints during inference, offering practical optimizations that can greatly improve model performance and scalability. By providing a comprehensive analysis of MoE inference bottlenecks and introducing novel optimization techniques like dynamic gating and expert buffering, this work paves the way for more efficient and practical applications of MoE models in various domains, including natural language processing and machine translation. The results and open-sourced code will be particularly valuable to researchers seeking to deploy and improve the performance of their own MoE models.

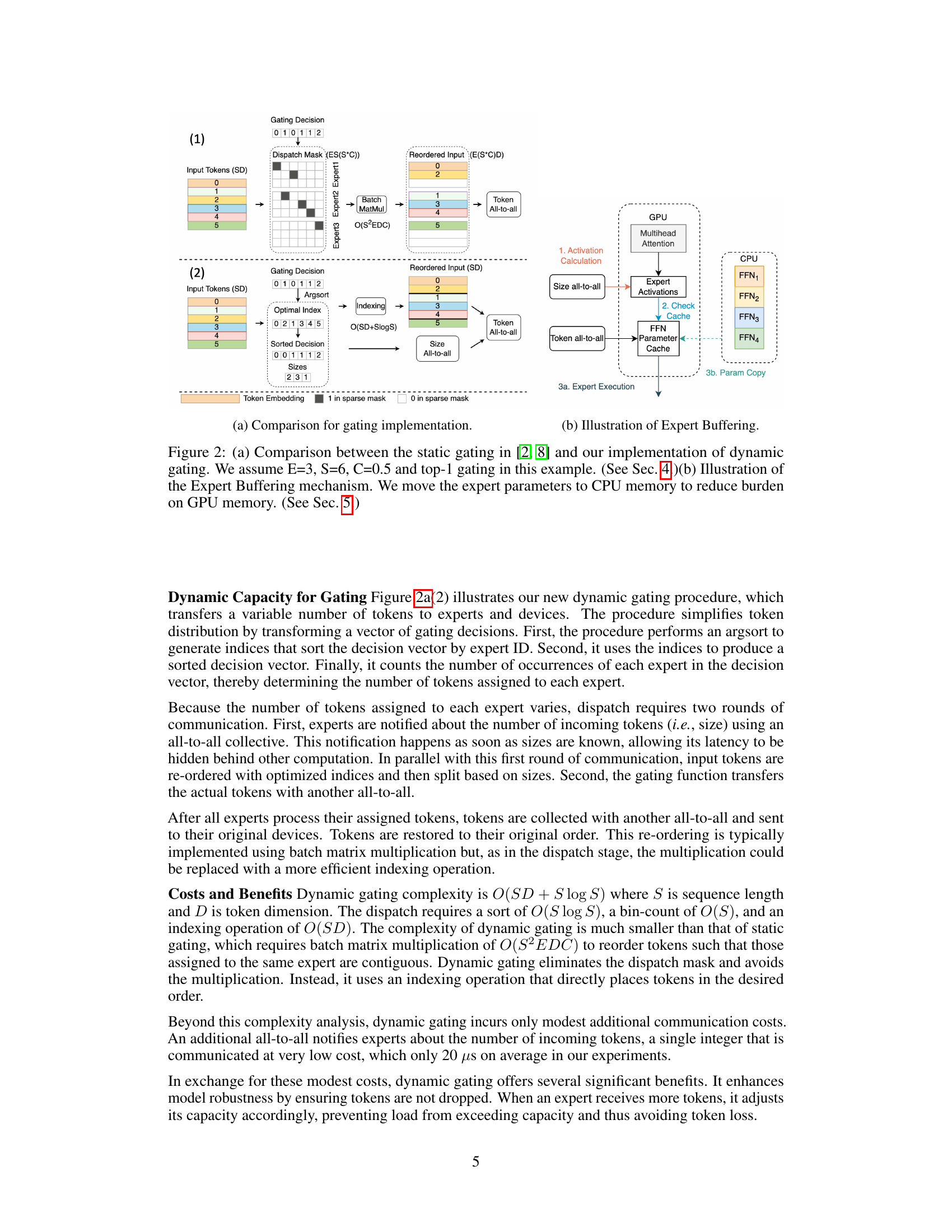

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the architecture of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models. Panel (a) shows a basic MoE module, where a gating network determines which expert networks to activate for a given input. Panels (b), (c), and (d) progressively show how MoE layers are incorporated into a Transformer architecture, increasing complexity and parallelization. Panel (b) shows a standard Transformer decoder layer. Panel (c) replaces the FFN (feed-forward network) with multiple expert FFNs. Finally, Panel (d) shows a distributed MoE Transformer with expert parallelism, where each expert is hosted on a different device, demonstrating the complex communication required in practical MoE deployments.

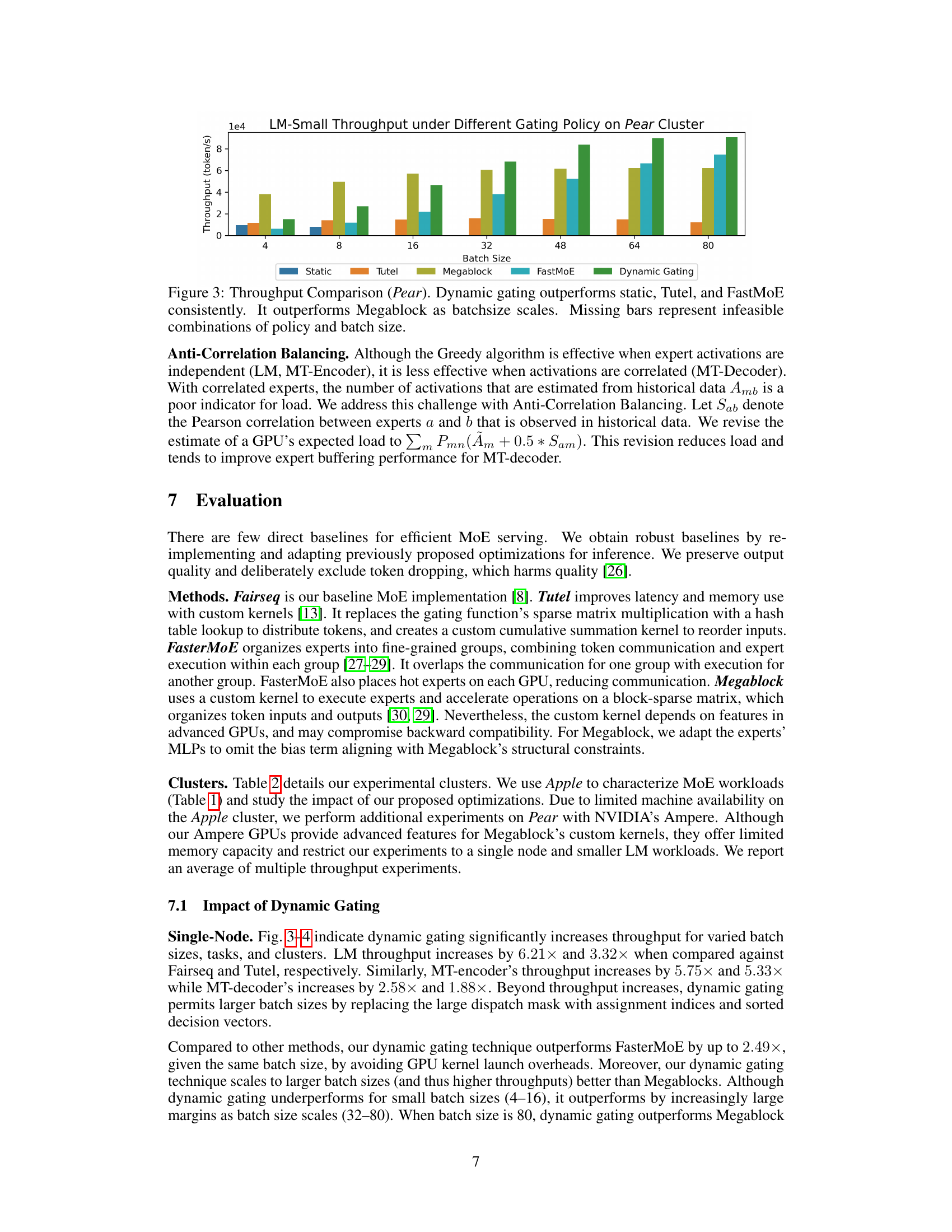

This table presents the architecture details and hyperparameters for three different language modeling tasks: LM-Small, LM, and MT. For each task, it shows the model type (Dense or MoE), the total number of parameters (Size), the number of experts (E) and the interval between MoE layers (M) for the MoE models. Capacity fraction (C) specifies the portion of total capacity used by each expert. Finally, it also lists architecture parameters such as token dimension (TD), hidden dimension (HD) and vocabulary size.

In-depth insights#

MoE Inference#

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models, while powerful, present significant challenges for inference. High latency and excessive memory consumption are major hurdles, stemming from the complex communication patterns inherent in routing tokens to sparsely activated experts. The paper addresses these challenges by characterizing MoE workloads, identifying key sources of inefficiency (e.g., the gating function, load imbalance), and proposing innovative optimization strategies. Dynamic gating is key, adapting expert capacity to actual token assignments, thereby improving throughput and reducing memory use. Expert buffering efficiently manages GPU memory by caching frequently accessed experts, while load balancing techniques further enhance performance and robustness. The results show substantial improvements in speed and resource efficiency across various tasks and hardware configurations, proving the effectiveness of these tailored optimizations for MoE inference deployment.

Dynamic Gating#

The core idea behind Dynamic Gating is to improve the efficiency of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models by addressing the inefficiency caused by static gating policies. Static gating often leads to significant waste due to capacity mismatches, where experts are given a fixed capacity, irrespective of the actual number of tokens assigned. Dynamic gating solves this by adapting expert capacity to the number of incoming tokens in real-time. This dynamic adjustment reduces communication and computation overheads, as experts only process what is necessary, leading to reduced latency and memory consumption. This approach is particularly effective in handling scenarios with highly imbalanced expert loads, making MoE inference significantly more efficient and robust. Expert Buffering is another optimization strategy that can complement Dynamic Gating by optimizing memory usage and improving GPU utilization. By combining Dynamic Gating with other optimizations, the paper achieves notable improvements in throughput and resource efficiency, showcasing the promise of this dynamic approach for deploying large-scale MoE models in real-world applications.

Expert Buffering#

The proposed Expert Buffering optimization directly addresses the memory limitations inherent in Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models, particularly during inference. By strategically caching only the “hot,” frequently accessed experts in GPU memory while storing less-frequently used experts in CPU memory, it significantly reduces the static memory allocation requirement. This approach cleverly leverages the temporal locality often observed in expert activations, leading to improved memory efficiency without substantially compromising performance. The mechanism elegantly manages GPU memory through an eviction policy, prioritizing active experts and leveraging CPU memory as a buffer, ensuring efficient resource utilization. Expert Buffering’s orthogonality to other optimization techniques like offloading makes it a valuable addition to existing memory management strategies. Its practicality is further enhanced by its seamless integration with other proposed optimizations such as Dynamic Gating and Load Balancing, highlighting its potential as a key component in achieving efficient and robust MoE inference.

Load Balancing#

The research paper section on load balancing addresses the crucial inefficiency in Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models stemming from uneven token distribution across experts. Uneven expert workloads lead to underutilized resources and potential out-of-memory errors. The authors recognize that while training might encourage balanced allocation, inference patterns often deviate significantly. To mitigate this, a greedy load balancing algorithm is proposed that dynamically assigns experts to GPUs based on historical activation data, aiming to minimize maximum GPU load. A further refinement is introduced to account for correlation between expert activations in specific tasks, demonstrating robustness. This highlights that load balancing is not a static problem but one that requires dynamic adjustment during inference to ensure optimal performance and resource utilization. The approach’s effectiveness is empirically validated, showing improved throughput and robustness, particularly in multi-node settings, illustrating its practical value in deploying large-scale MoE models.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending dynamic gating to handle even more complex scenarios such as extremely large models or diverse activation patterns across experts is crucial. Investigating alternative expert buffering strategies beyond LIFO, possibly employing more sophisticated caching mechanisms informed by detailed analysis of expert access patterns, warrants further investigation. Addressing the inherent limitations of greedy load balancing, perhaps through the development of more sophisticated, potentially machine learning-based approaches, could lead to better resource utilization and more robust performance. Exploring the interaction between dynamic gating, expert buffering, and load balancing in more depth, potentially through rigorous simulation studies, may reveal novel synergies and optimality points. Finally, integrating these optimizations with other recent advances in MoE model design and inference optimization, like heterogeneous experts and advanced communication primitives, represents a fertile area for future research.

More visual insights#

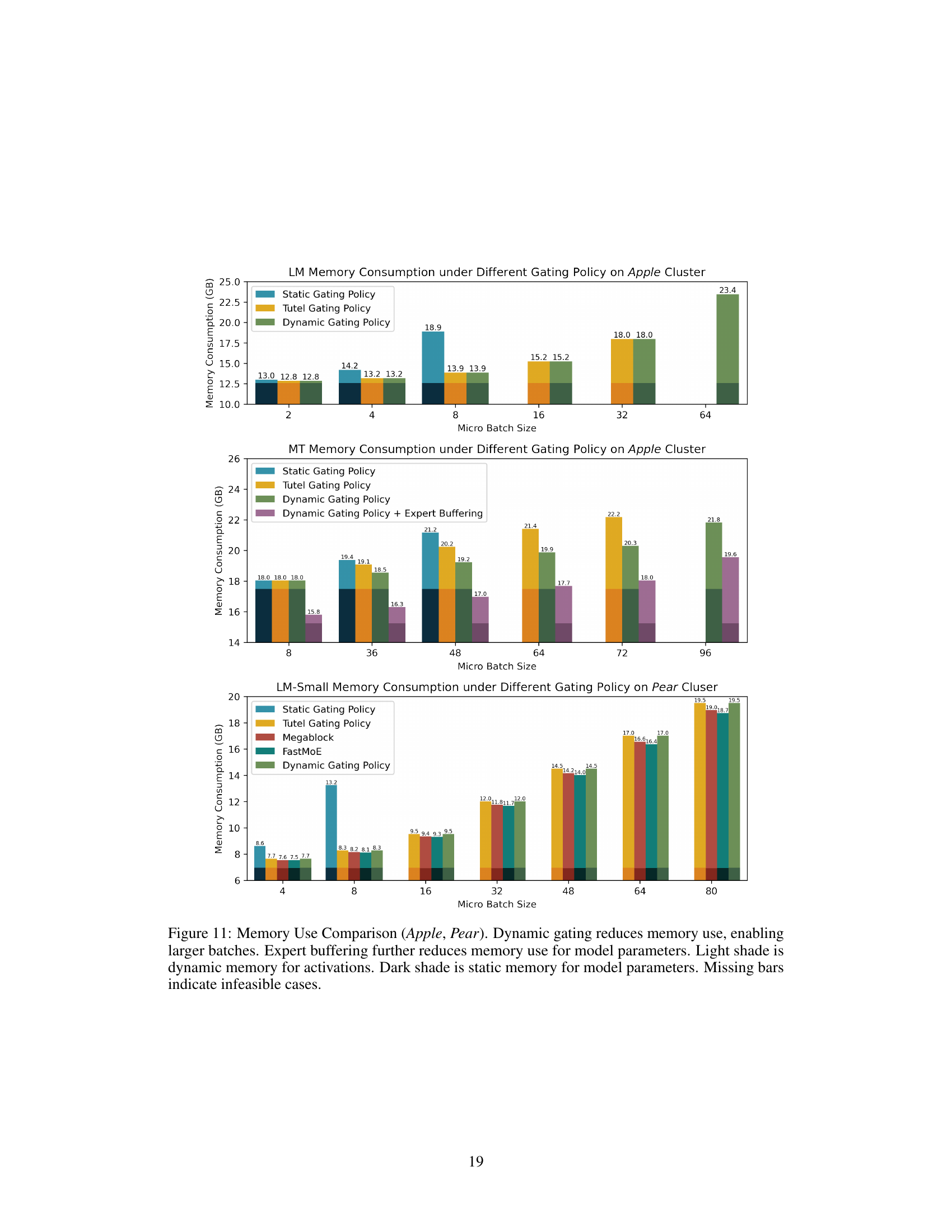

More on figures

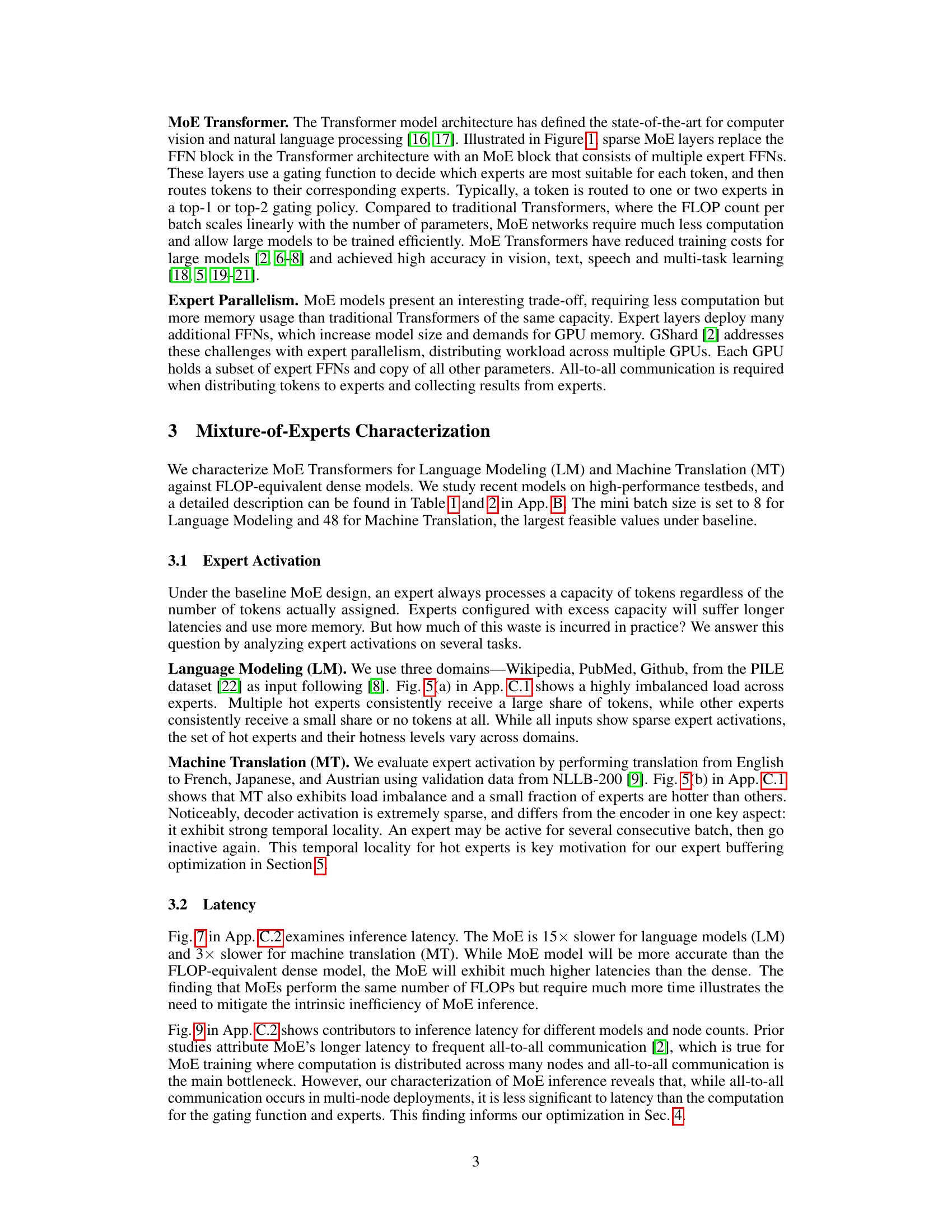

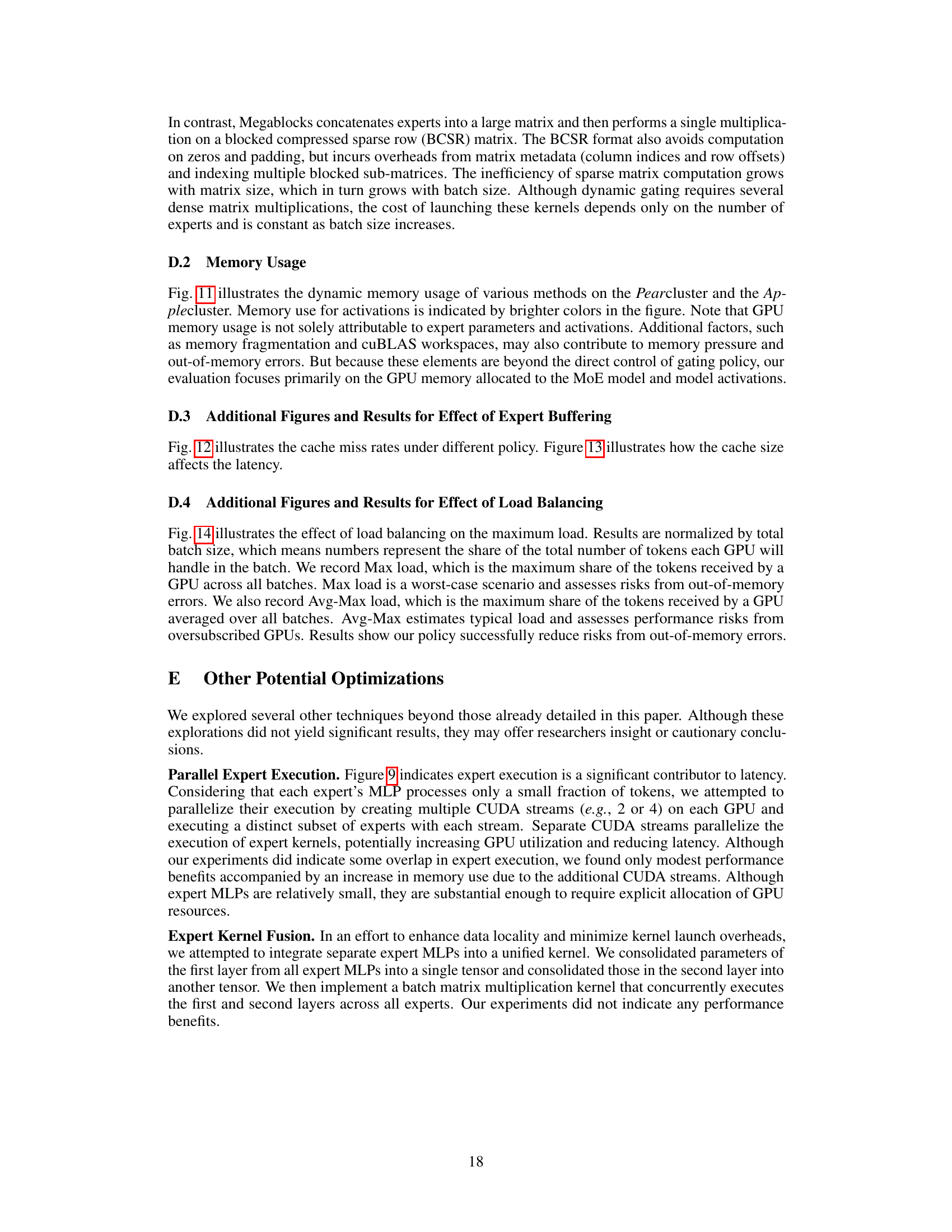

This figure compares static and dynamic gating methods in MoE models, illustrating the process of token assignment to experts and the impact on computational efficiency. It also shows the Expert Buffering optimization, which offloads less frequently used expert parameters from GPU memory to CPU memory to improve GPU resource utilization and enable larger batch sizes.

This figure illustrates two optimization techniques for Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) inference. (a) compares static and dynamic gating, highlighting how dynamic gating improves efficiency by adapting to varying expert loads. (b) shows the Expert Buffering mechanism, which moves less frequently used expert parameters from GPU to CPU memory to reduce GPU memory pressure and improve performance.

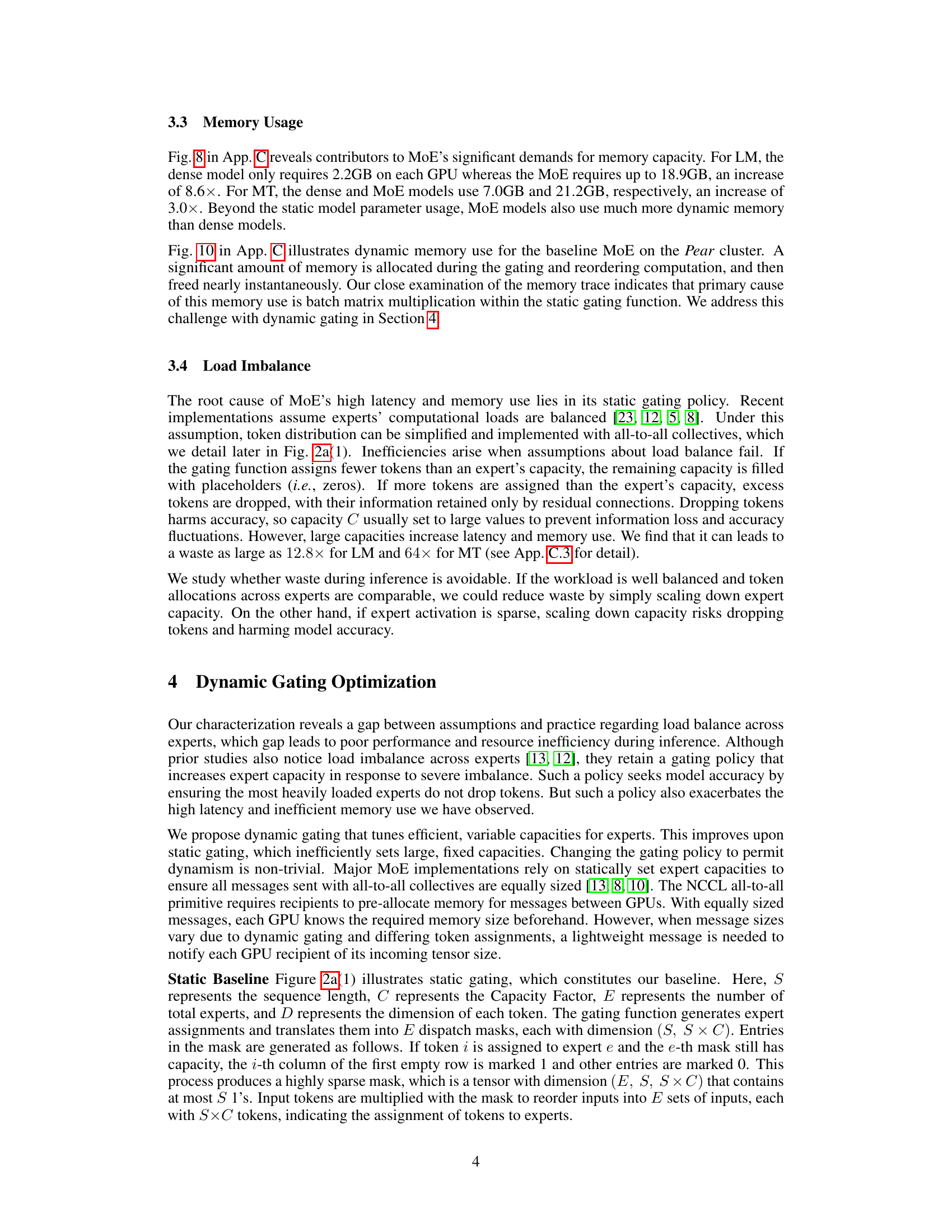

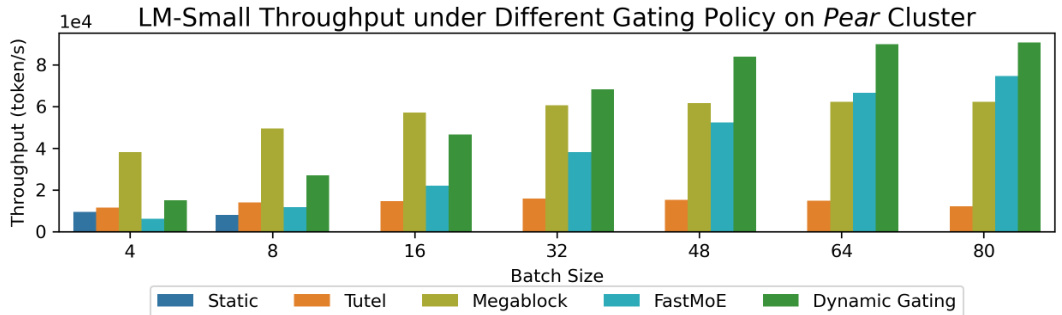

This figure compares the throughput of different gating policies (static, Tutel, Megablock, FastMoE, and dynamic gating) for LM-Small model on the Pear cluster. The x-axis represents different batch sizes, and the y-axis represents the throughput in tokens per second. The figure shows that dynamic gating consistently outperforms other methods across various batch sizes, particularly showing significant improvement as the batch size increases. Missing bars indicate that certain combinations of gating policy and batch size were not feasible to test.

This figure compares the throughput of different gating policies (static, Tutel, FastMoE, Megablock, and dynamic gating) for language modeling (LM) and machine translation (MT) tasks on the Pear cluster. The x-axis represents the batch size, and the y-axis represents the throughput (tokens per second). Dynamic gating consistently outperforms the other methods across different batch sizes and tasks, especially for larger batch sizes. The missing bars in the chart indicate that some combinations of gating policies and batch sizes were not feasible due to resource constraints.

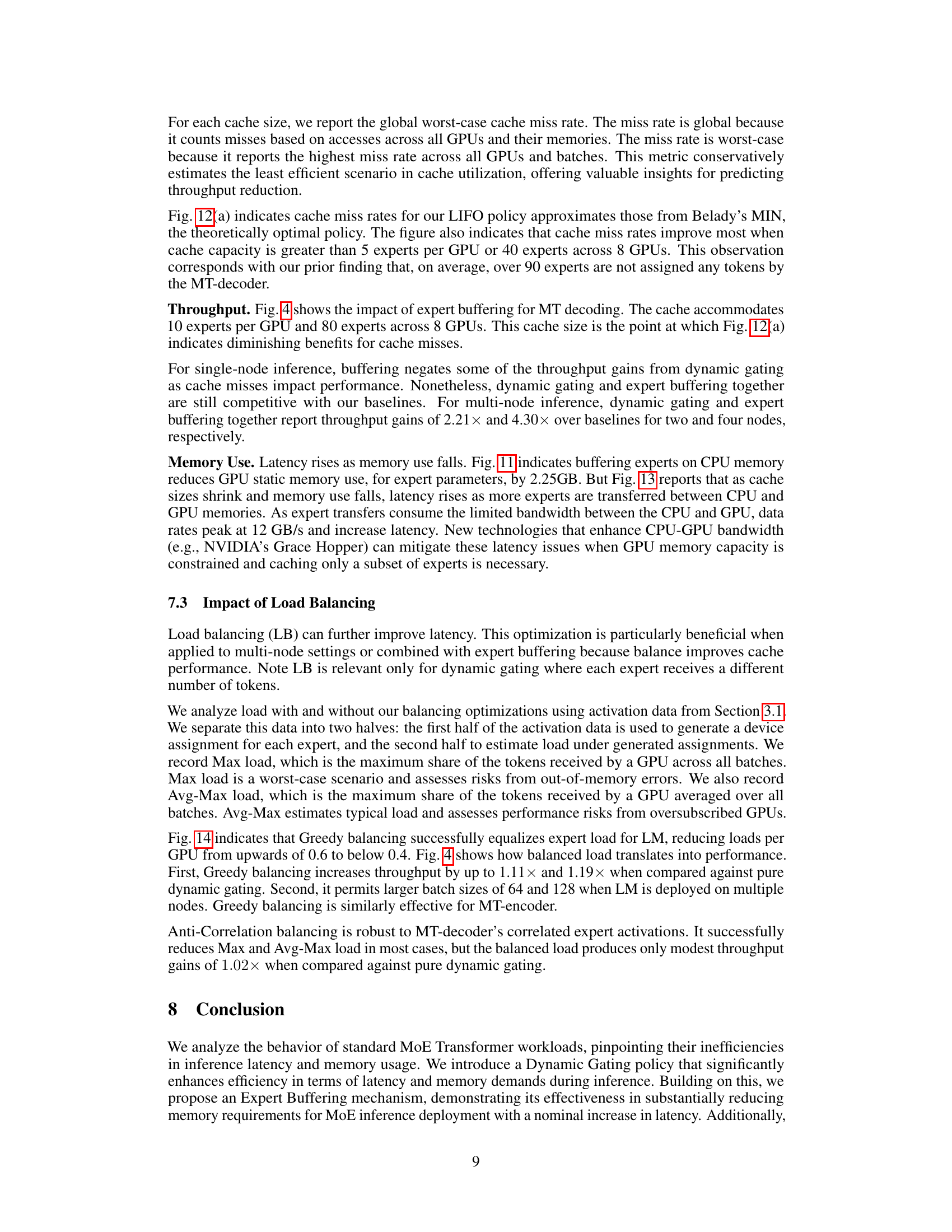

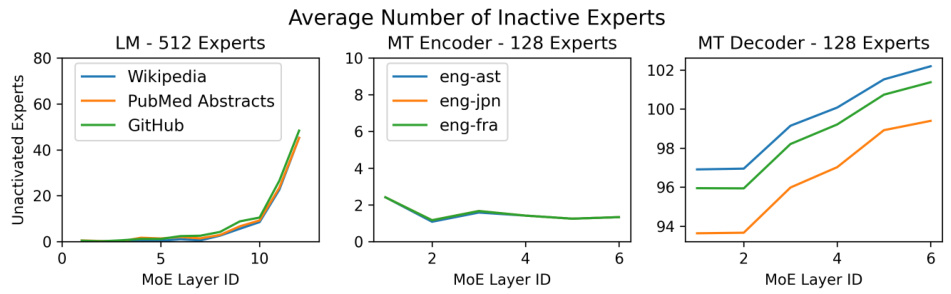

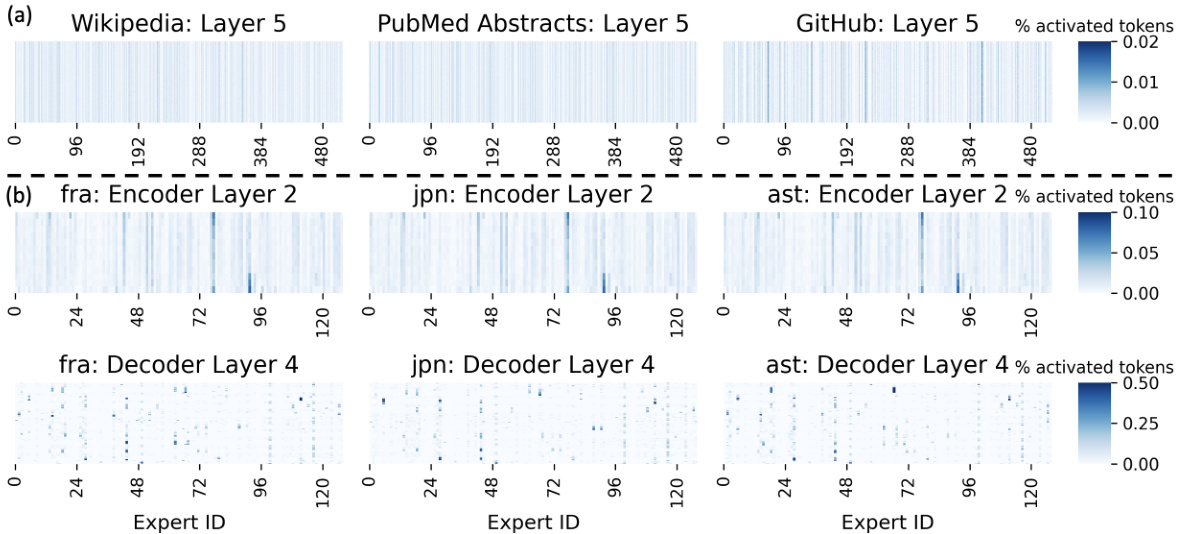

This figure shows the average number of inactive experts across different MoE layers for three different tasks: Language Modeling (LM), Machine Translation encoder (MT Encoder), and Machine Translation decoder (MT Decoder). The key observation is the significant difference in expert activation patterns between the encoder and decoder. LM and the encoder exhibit high activation levels (most experts are active), while the decoder shows extremely sparse activation (a large number of experts remain inactive). This difference highlights a key characteristic of MoE models, particularly for machine translation where some experts may be heavily used while others remain unused across many layers. This is an important finding because it informs optimization strategies for MoE inference.

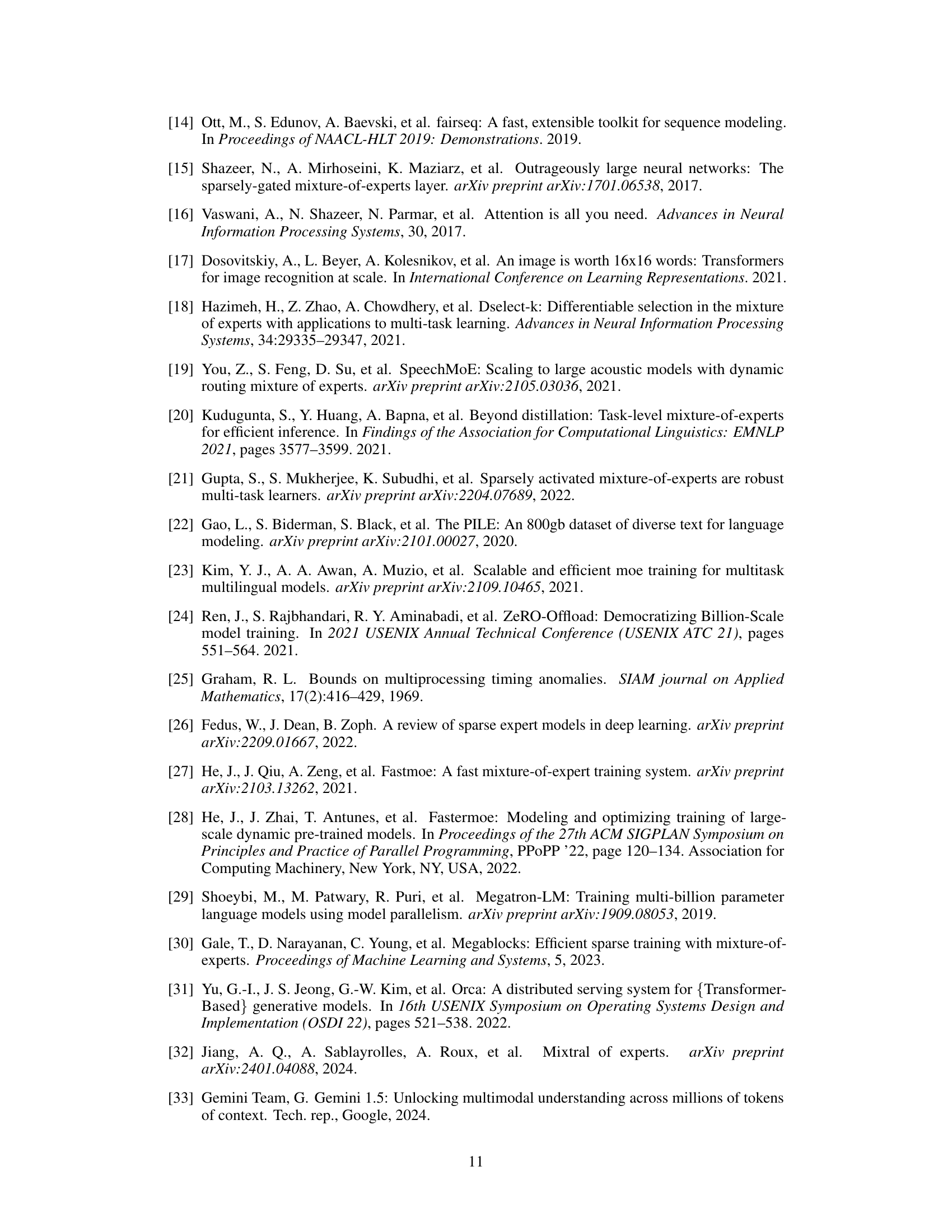

This figure compares the inference latency of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models and their corresponding dense model counterparts across three tasks: Language Modeling (LM), Machine Translation Encoder (MT Encoder), and Machine Translation Decoder (MT Decoder). The results reveal that MoE models exhibit significantly higher latency compared to their dense counterparts. Specifically, MoE models are 15 times slower for the LM task, 22 times slower for MT encoding, and 3 times slower for MT decoding. This highlights a critical performance challenge associated with MoE models during inference.

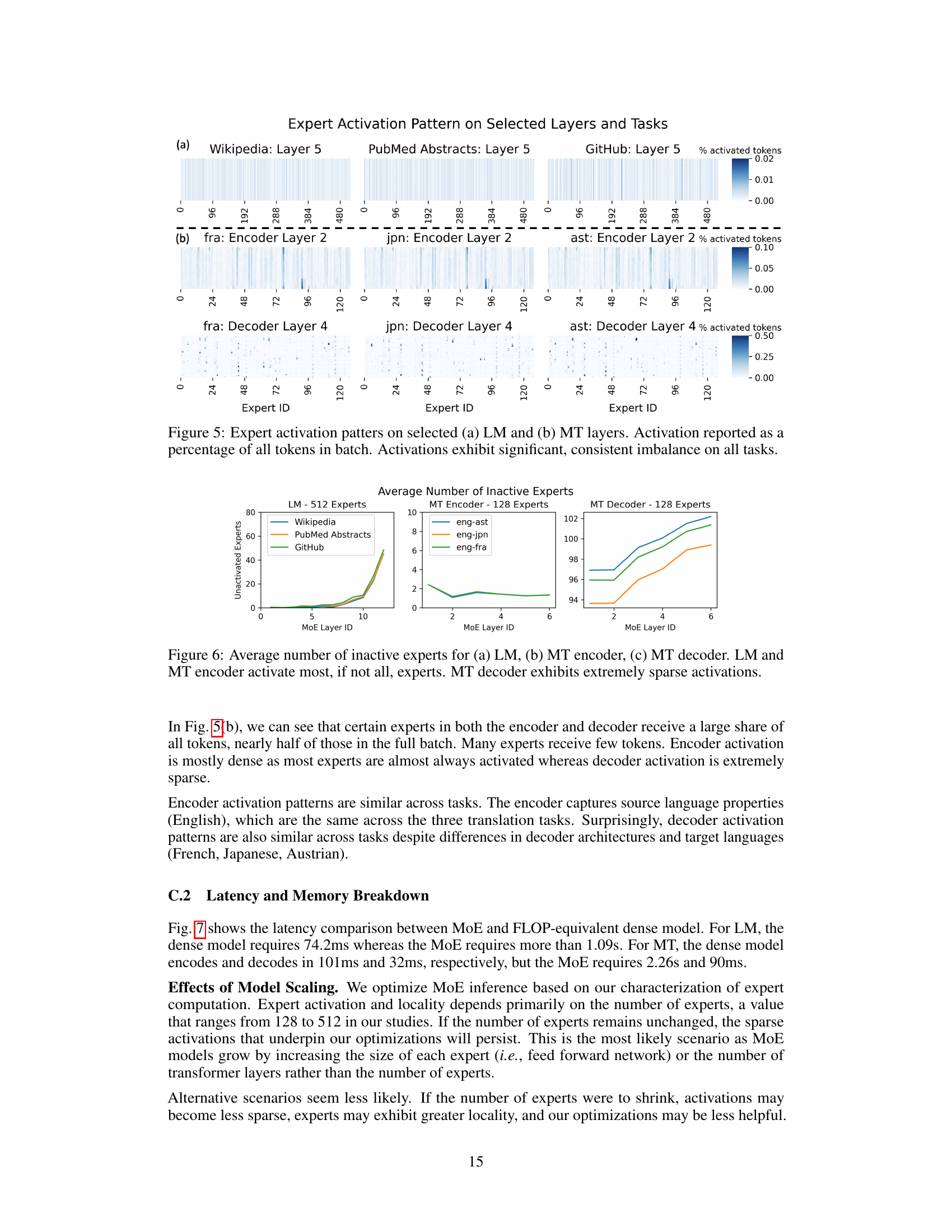

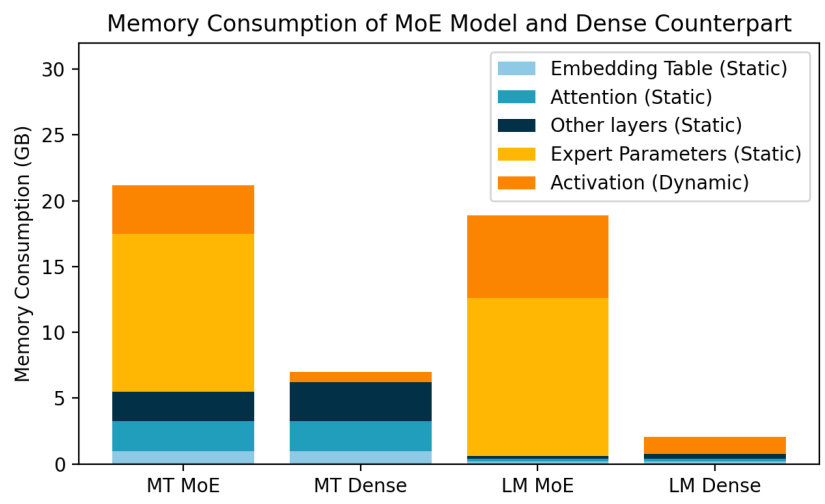

This figure compares the memory usage between MoE models and their dense counterparts for both Language Modeling (LM) and Machine Translation (MT) tasks. It shows a breakdown of memory consumption into different components: embedding table, attention mechanism, other layers, expert parameters, and dynamic activations. The key takeaway is that MoE models, while computationally more efficient during training, consume significantly more memory due to the larger number of parameters and the dynamic nature of expert activation during inference.

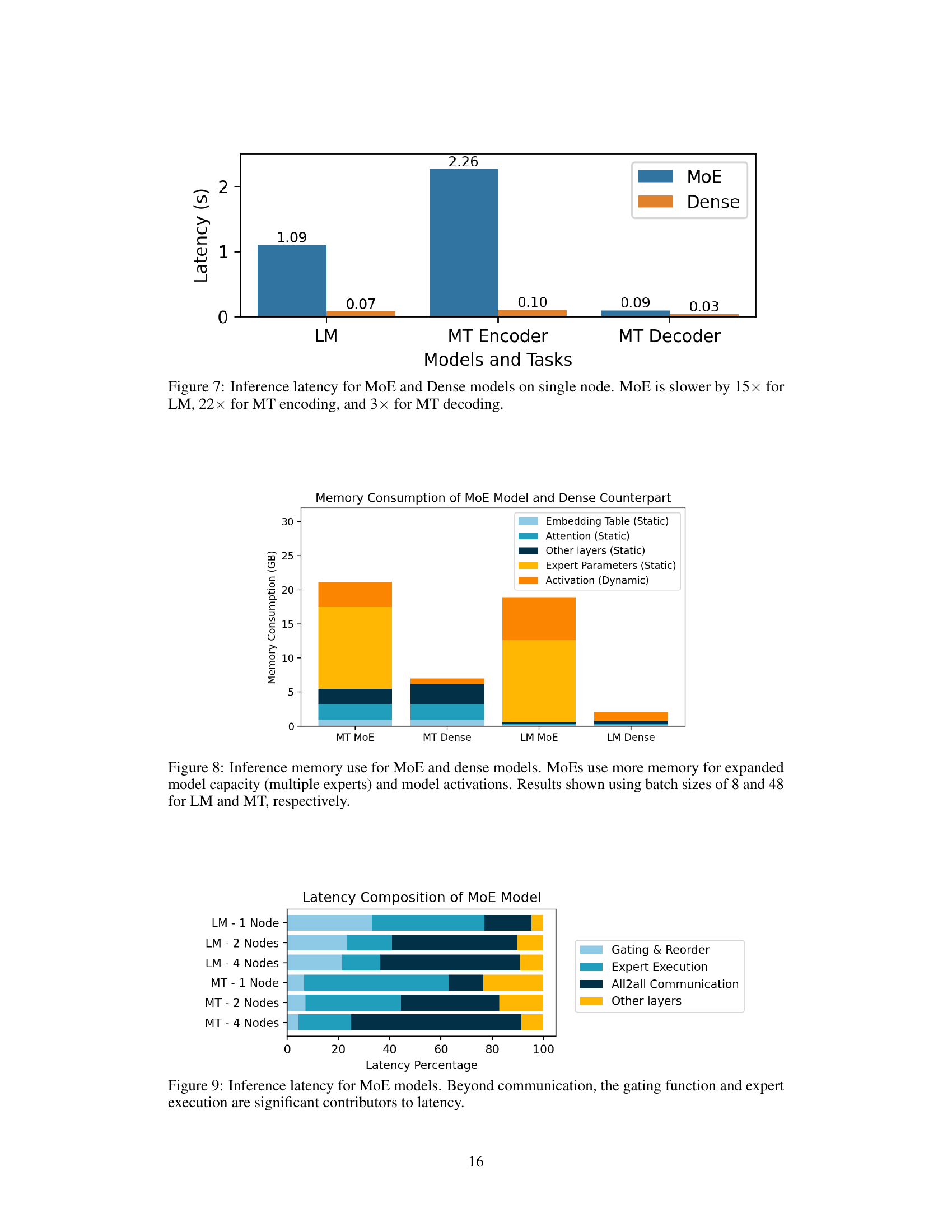

This figure shows a breakdown of latency for Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models across different tasks (language modeling and machine translation) and numbers of nodes. It demonstrates that while inter-node communication contributes to latency, the gating function (which determines which expert handles which token) and the expert execution time itself are major components of the overall latency. This visualization helps to understand where optimization efforts should focus to improve the inference speed of MoE models.

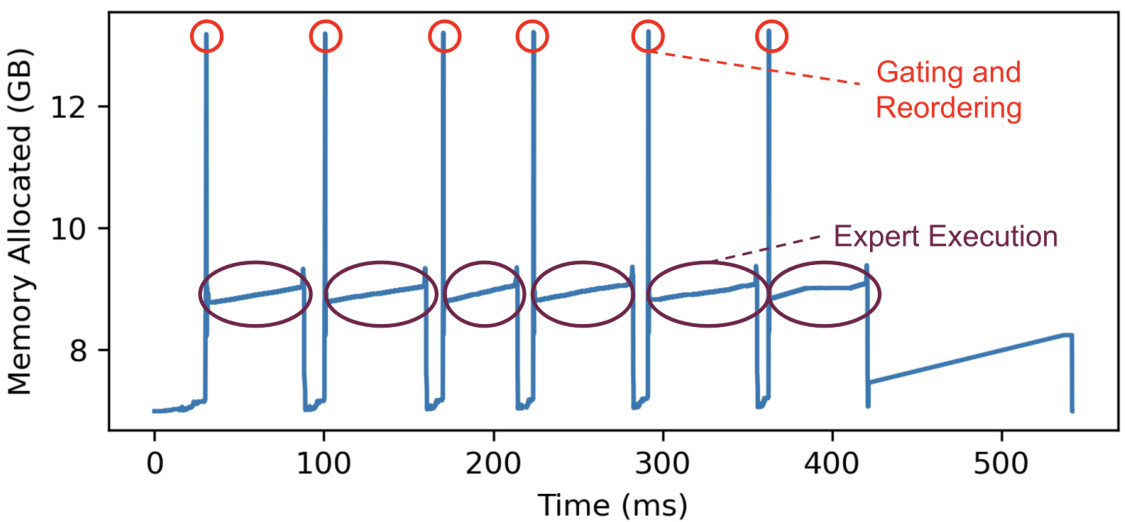

This figure shows the memory usage over time for a baseline Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) model during inference on the Pear cluster. The blue line represents the total memory allocated, while the red dashed line highlights the memory usage specifically for the gating and reordering phase. The purple dashed line highlights the memory usage for the expert execution phase. The spikes in memory allocation during the gating and reordering phases are significant, indicating inefficiencies in the baseline MoE’s memory management. These spikes demonstrate the large amount of temporary memory required for this stage and then immediately released afterward, suggesting that optimizations in this area could significantly reduce the overall memory footprint of the model.

This figure shows the throughput comparison of different gating policies on the Pear cluster for LM-Small. The x-axis represents the batch size, and the y-axis represents the throughput (tokens/second). The bars represent the throughput achieved by different gating policies: static, Tutel, FastMoE, Megablock, and dynamic gating. Dynamic gating consistently outperforms all other methods. The performance advantage is more pronounced at larger batch sizes. Missing bars indicate that some combinations of gating policy and batch size were not feasible.

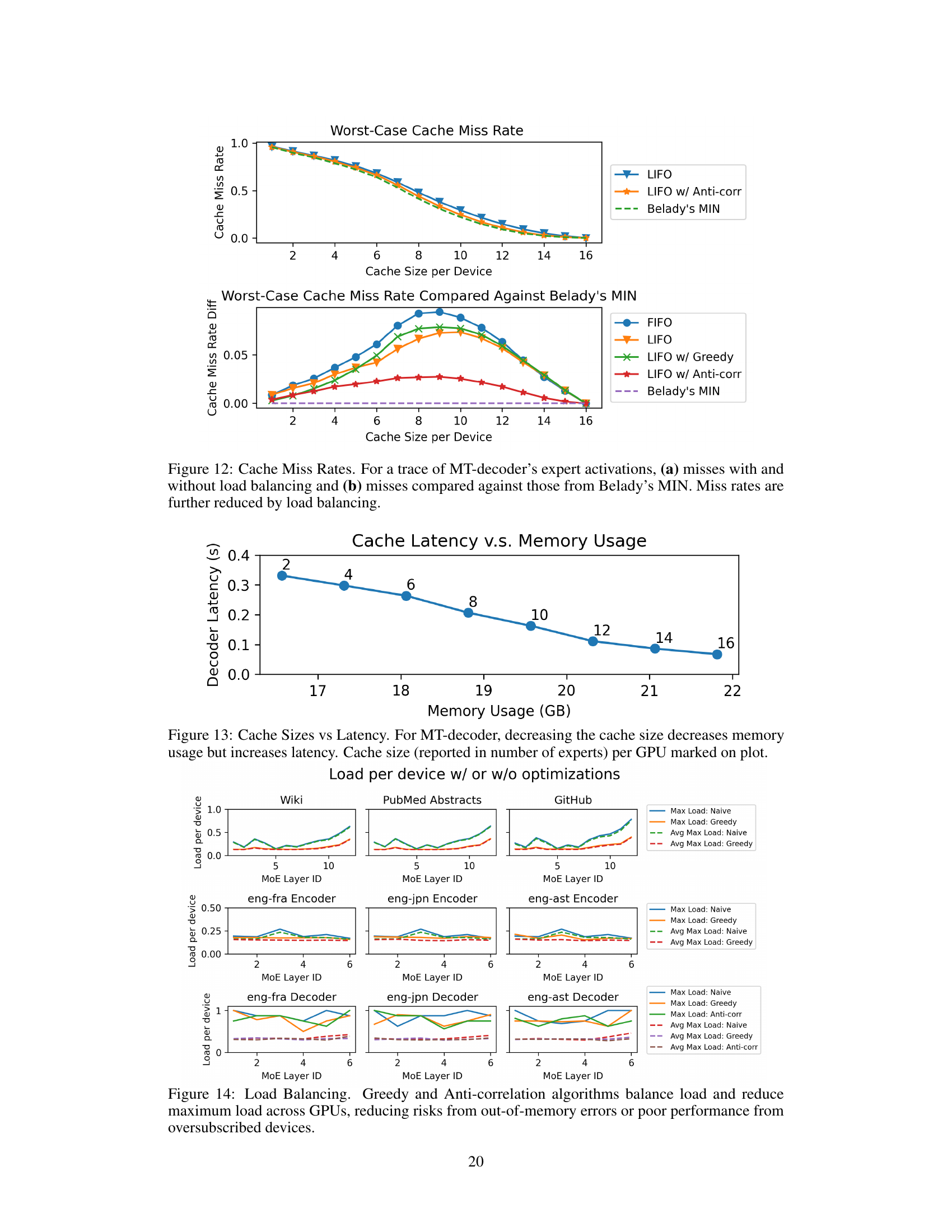

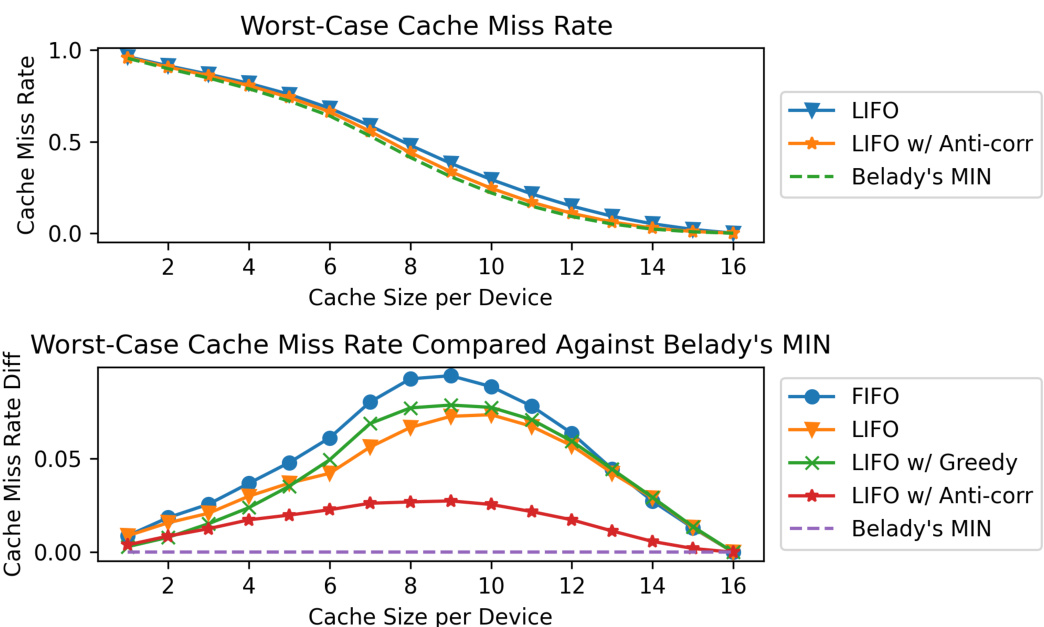

This figure shows the cache miss rates for different cache sizes and load balancing strategies in the context of machine translation decoder tasks. The top graph displays the worst-case cache miss rates for LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) policy, LIFO with anti-correlation, and Belady’s MIN (optimal replacement algorithm). The bottom graph compares the miss rate differences of various policies against Belady’s MIN, highlighting the effectiveness of the LIFO policy, particularly when combined with anti-correlation, in minimizing cache misses.

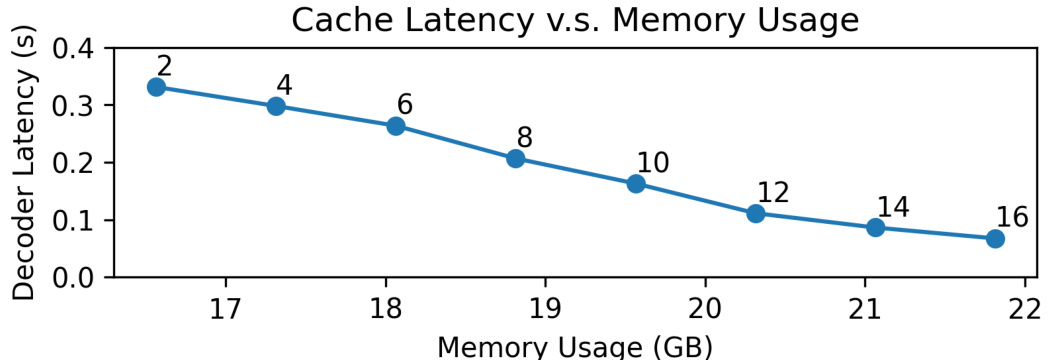

This figure shows the relationship between cache size (measured in the number of experts per GPU) and decoder latency and memory usage for machine translation decoder tasks. As expected, decreasing the cache size reduces memory usage. However, this also leads to increased latency because the system has to transfer more frequently accessed experts from CPU memory to GPU memory. The plot visually represents this trade-off.

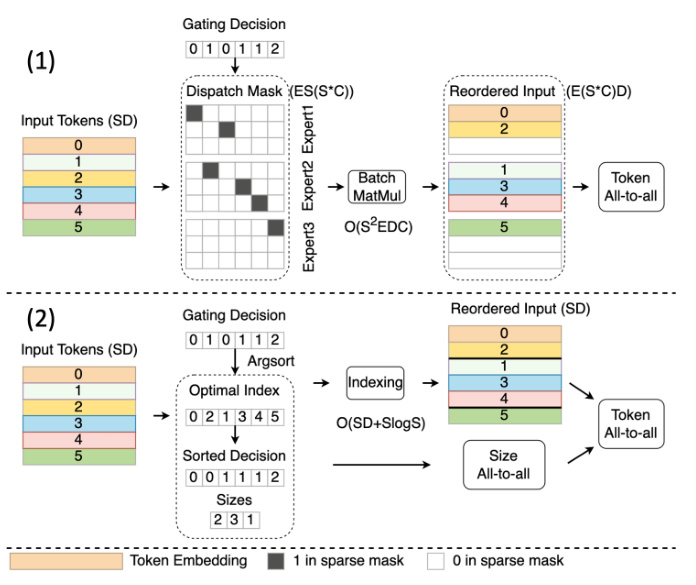

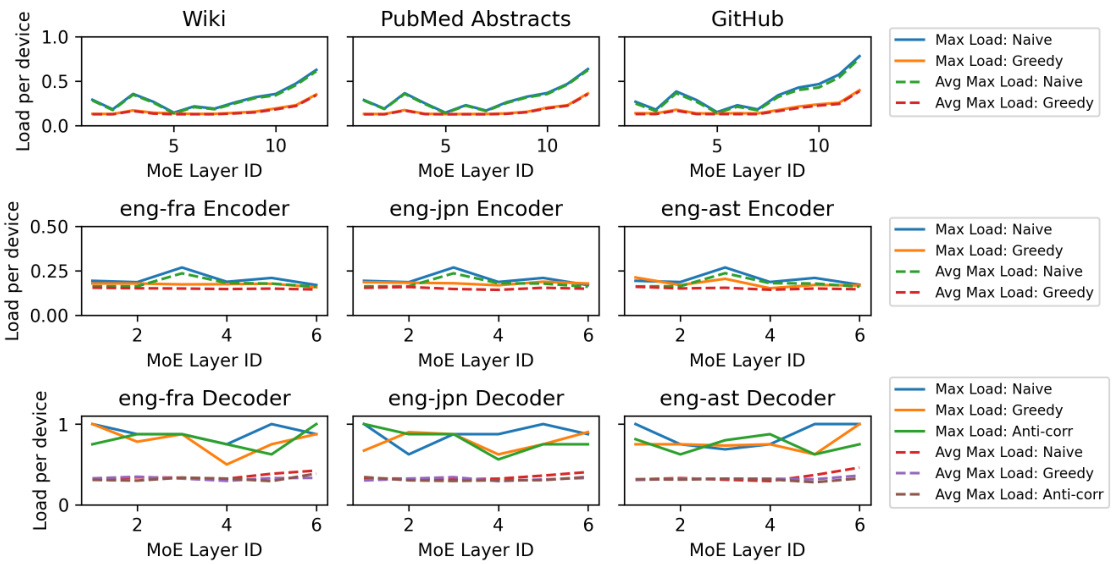

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed load balancing techniques (Greedy and Anti-correlation) in mitigating load imbalances across GPUs. It shows the maximum and average maximum load per GPU for various tasks (Language Modeling with three different datasets and Machine Translation into three different languages), comparing the results with and without the load balancing optimizations. The results indicate that the load balancing techniques successfully reduce the maximum load per GPU, thereby improving performance and reducing the risk of out-of-memory errors or poor performance caused by oversubscribed GPUs. The Anti-correlation method appears particularly effective for Machine Translation decoding tasks where expert activations are highly correlated.

More on tables

This table provides detailed information about the models used in the experiments. It includes the model type (dense or MoE), the model size, the number of experts (E), the MoE layer interval (M), the expert capacity fraction (C), and various model parameters such as token dimension (TD), hidden dimension (HD), and vocabulary size. These specifications are crucial for understanding and replicating the experimental setup and results.

This table provides detailed information about the model configurations used in the experiments for Language Modeling-Small (LM-Small), Language Modeling (LM), and Machine Translation (MT). It lists key hyperparameters such as the number of experts (E), how often a feed-forward network (FFN) block is replaced by a mixture-of-experts (MoE) block (M), and the capacity fraction of each expert (C). It also shows the model parameters including the token dimension (TD), hidden dimension (HD), and vocabulary size. These parameters are crucial for understanding the experimental setup and replicating the results.

Full paper#