↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional Neural Algorithmic Reasoning (NAR) models utilize recurrent neural networks mirroring the iterative nature of algorithms. This approach can be computationally expensive, especially for complex algorithms with many steps. Furthermore, the number of iterations is algorithm dependent and must be known beforehand. These limitations hinder the scalability and efficiency of NAR models.

This paper introduces Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoners (DEARs), a novel approach that directly solves for the algorithm’s equilibrium state using a deep equilibrium model. This method eliminates the need for iterative computations, making it significantly faster than existing NAR approaches and greatly reducing the computational cost. DEARs achieve comparable or even superior performance to traditional NAR models on benchmark algorithms, demonstrating its effectiveness and efficiency. The proposed method also introduces modifications to improve robustness and stability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it offers a faster and more efficient approach to neural algorithmic reasoning, a rapidly growing field. It challenges the conventional recurrent approach by focusing on the equilibrium state of algorithms. This not only improves performance but also opens up new avenues for research in model design, optimization techniques, and the application of equilibrium methods to broader AI problems. The proposed method, DEAR, shows promising results on benchmark problems and offers substantial improvements in inference speed. This work contributes significantly to the advancement of neural algorithmic reasoning and provides valuable insights for researchers in the field.

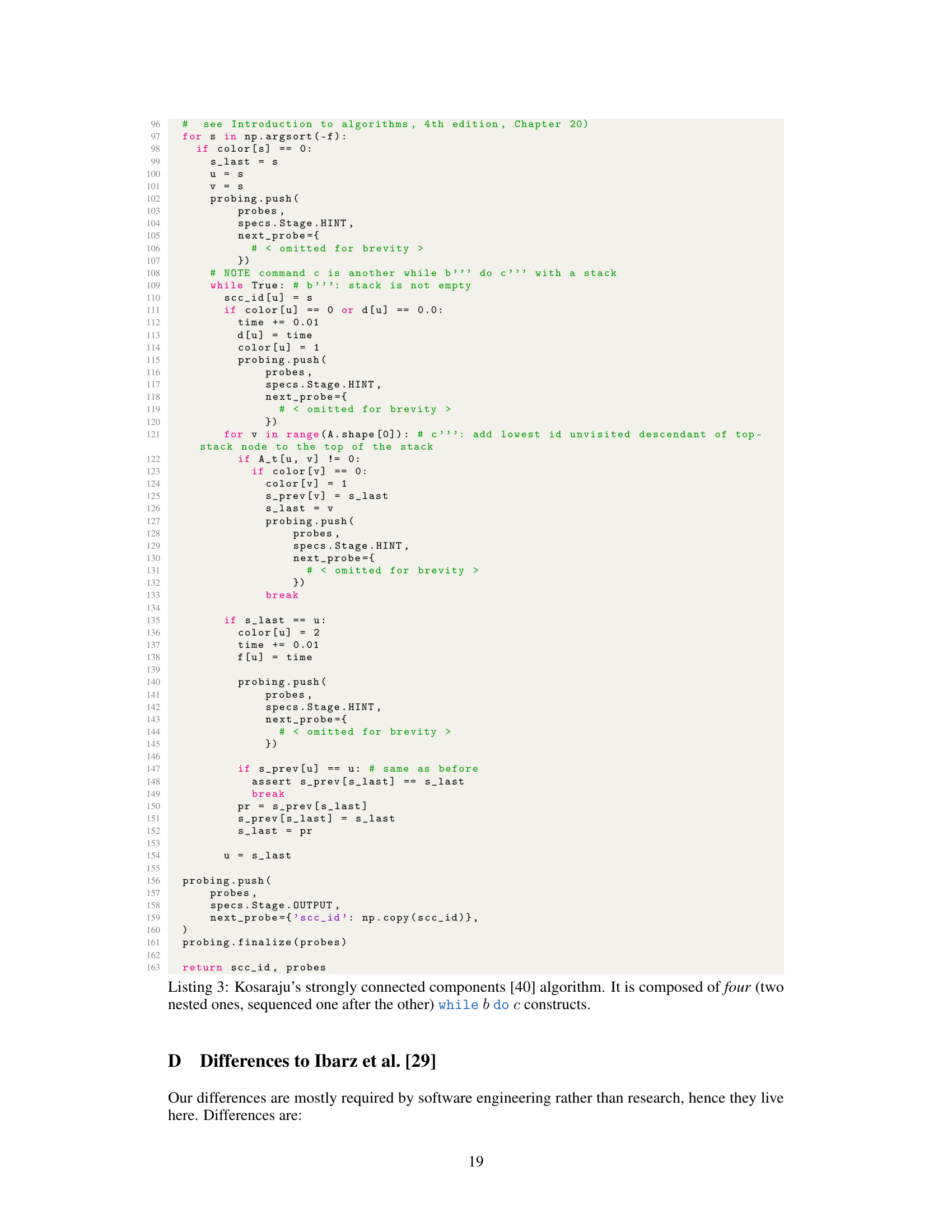

Visual Insights#

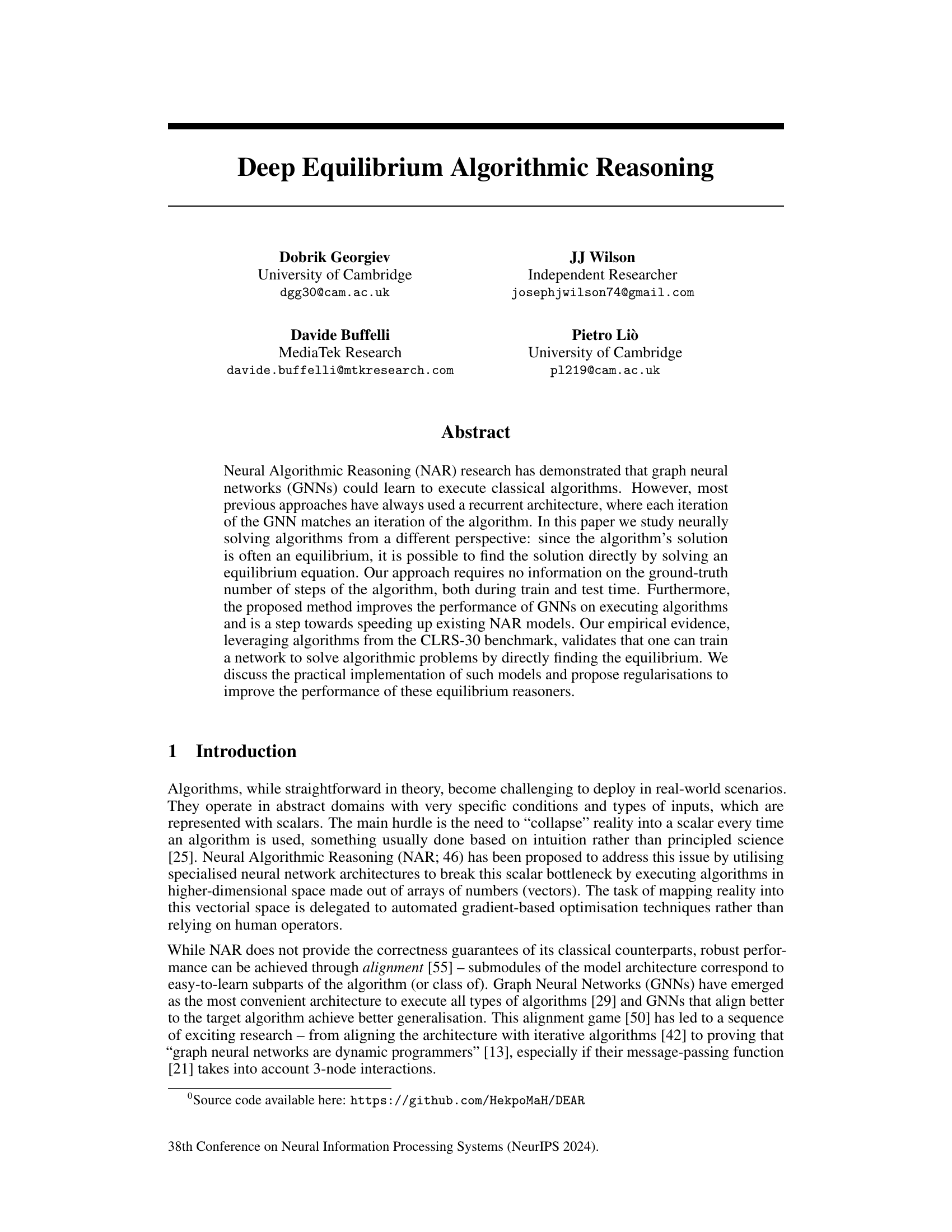

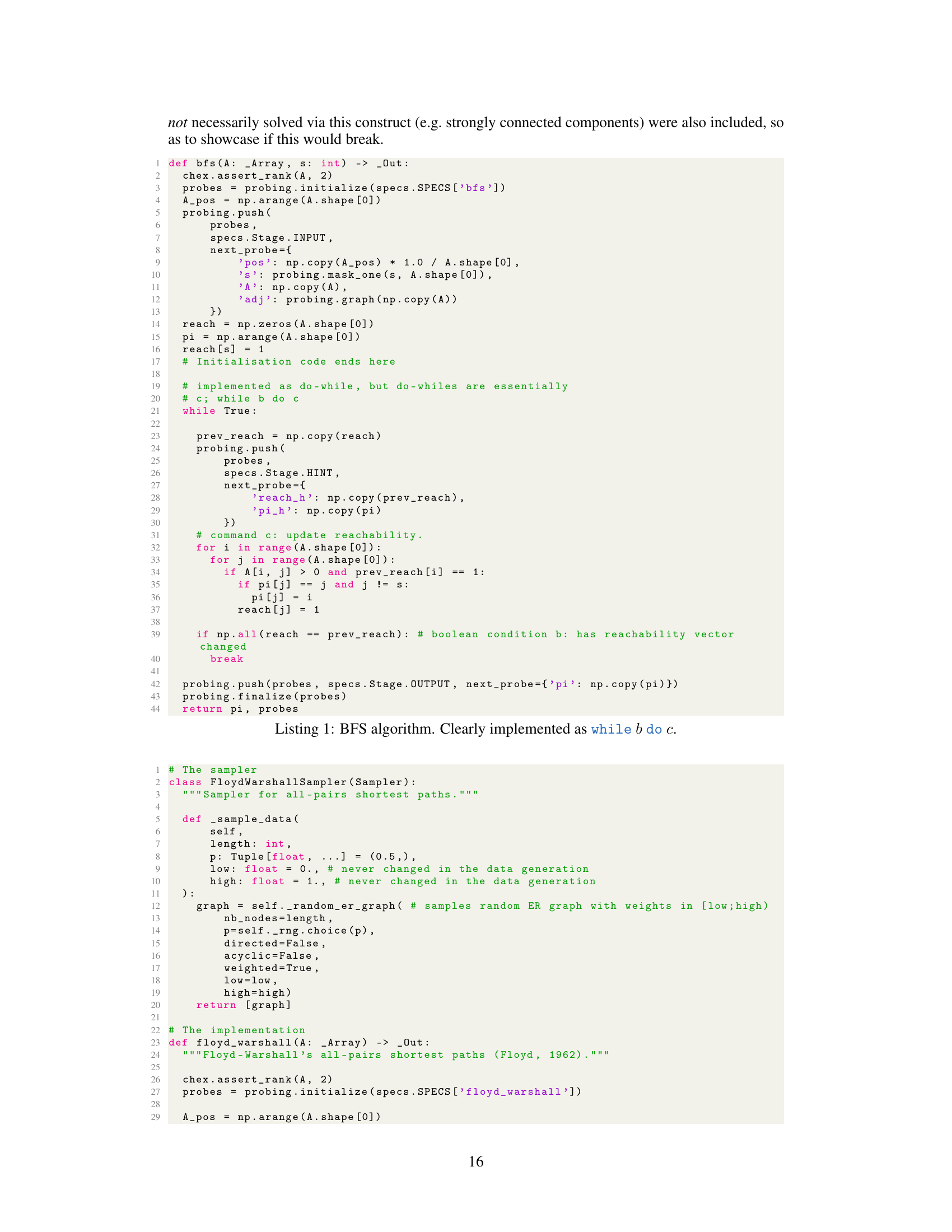

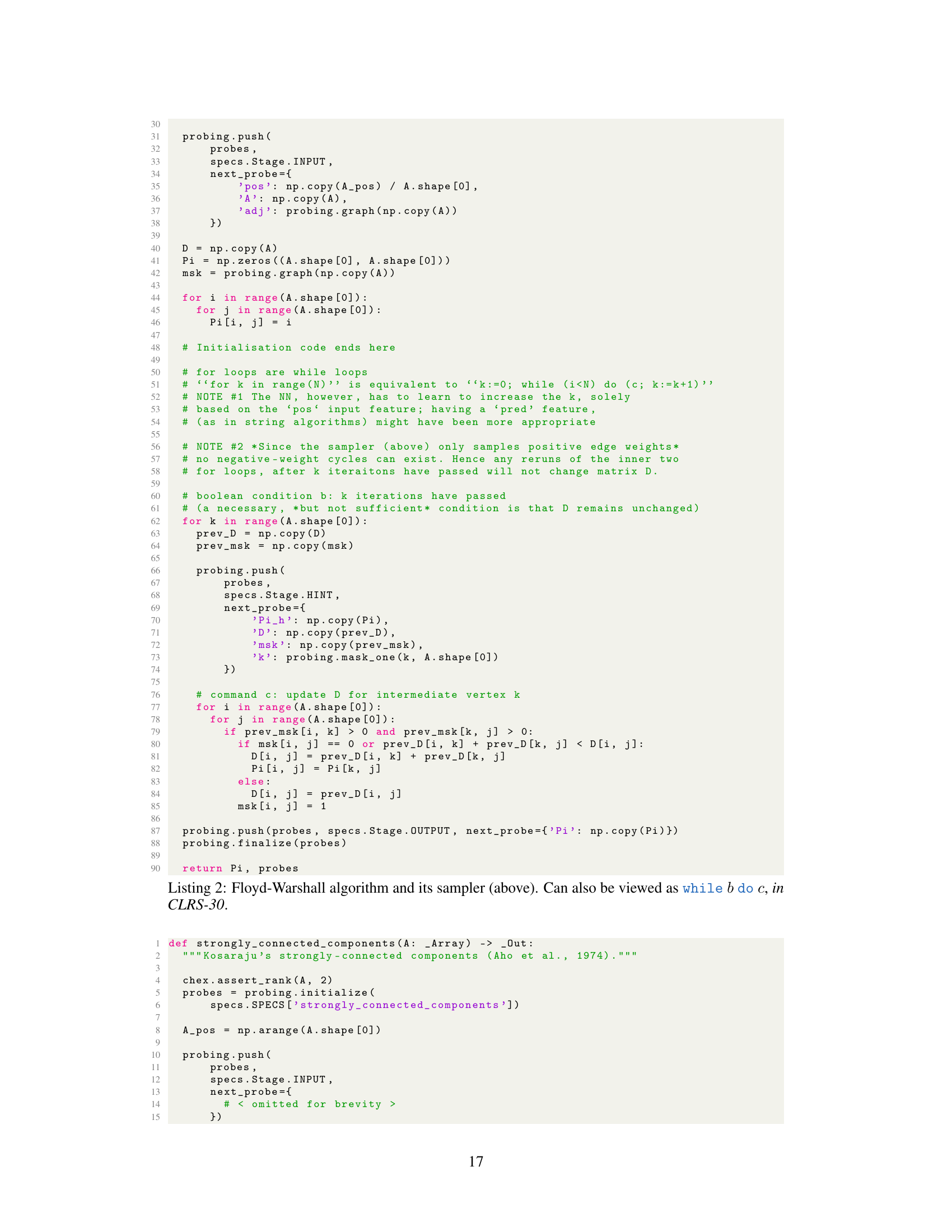

This figure illustrates the proposed alignment rule for Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoners (DEARs). The rule states that the sequence of states in the DEAR trajectory must always progress forward, never revisiting previously visited states (except for the start and end states which must align). This constraint helps to ensure that the DEAR model’s execution mirrors the forward progress of the algorithm it is emulating. The diagram uses arrows to represent the DEAR state transitions, as the direct equality between states may not always hold in the DEAR trajectory. The allowed and disallowed alignments of states are visually demonstrated, clarifying acceptable and unacceptable state mappings between the DEAR and GNN (Graph Neural Network) rollouts.

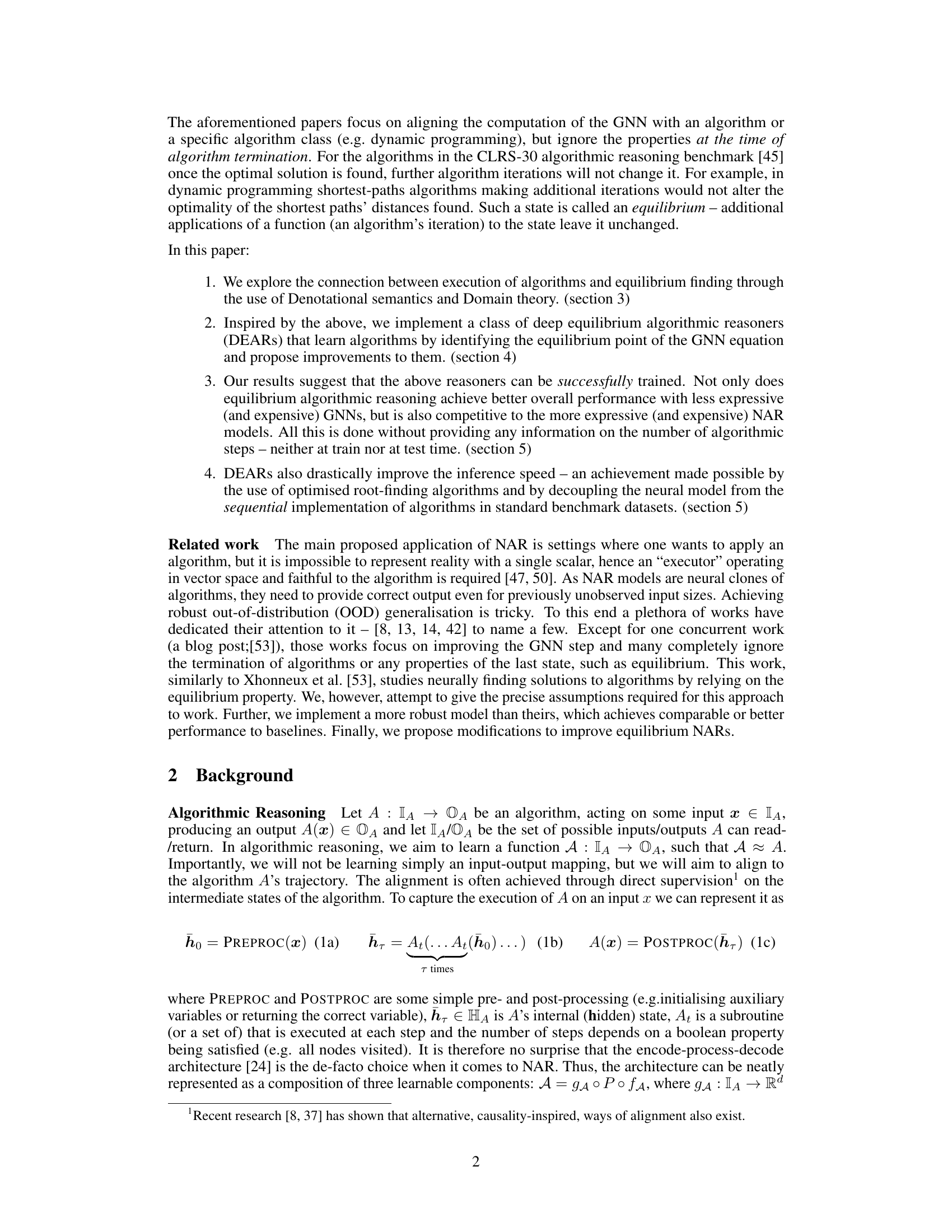

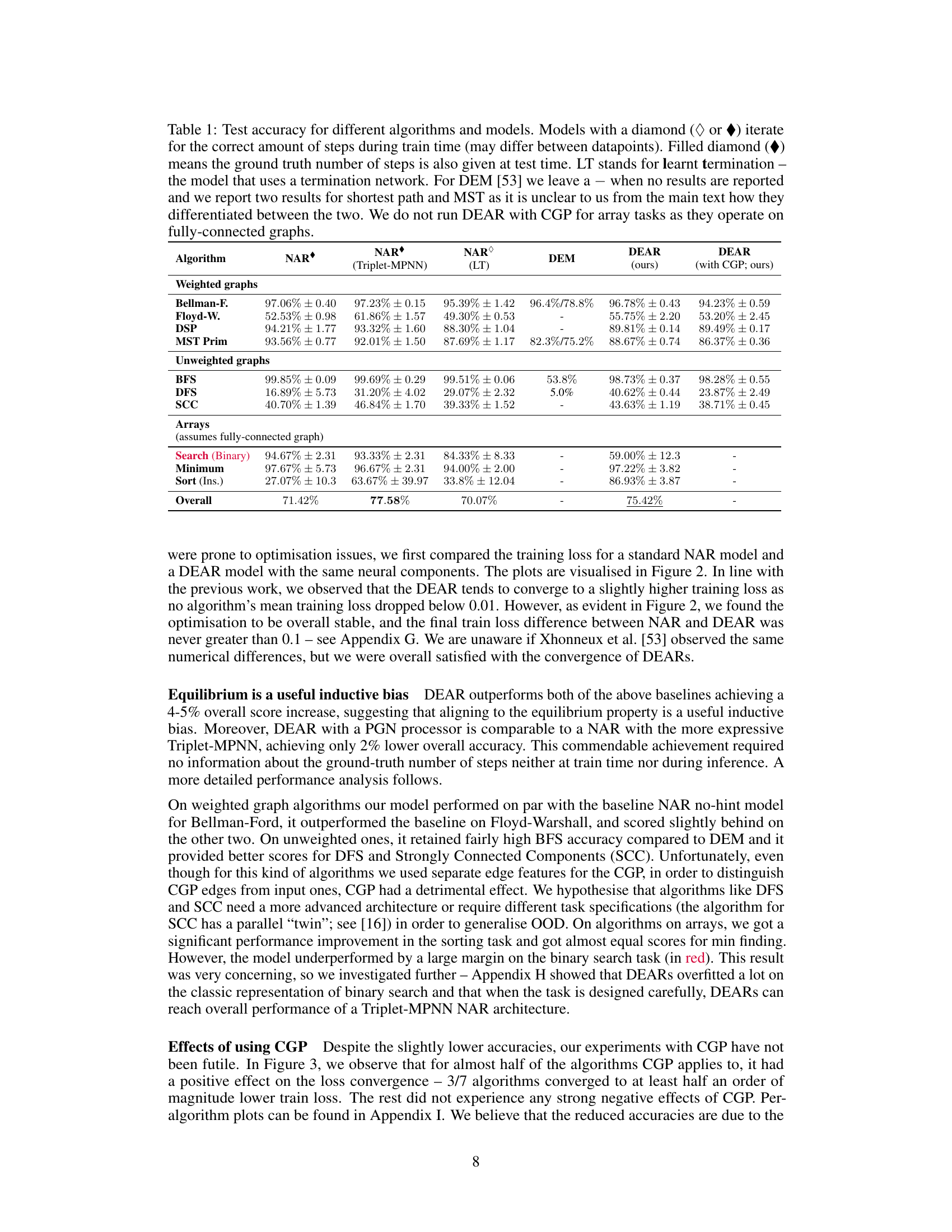

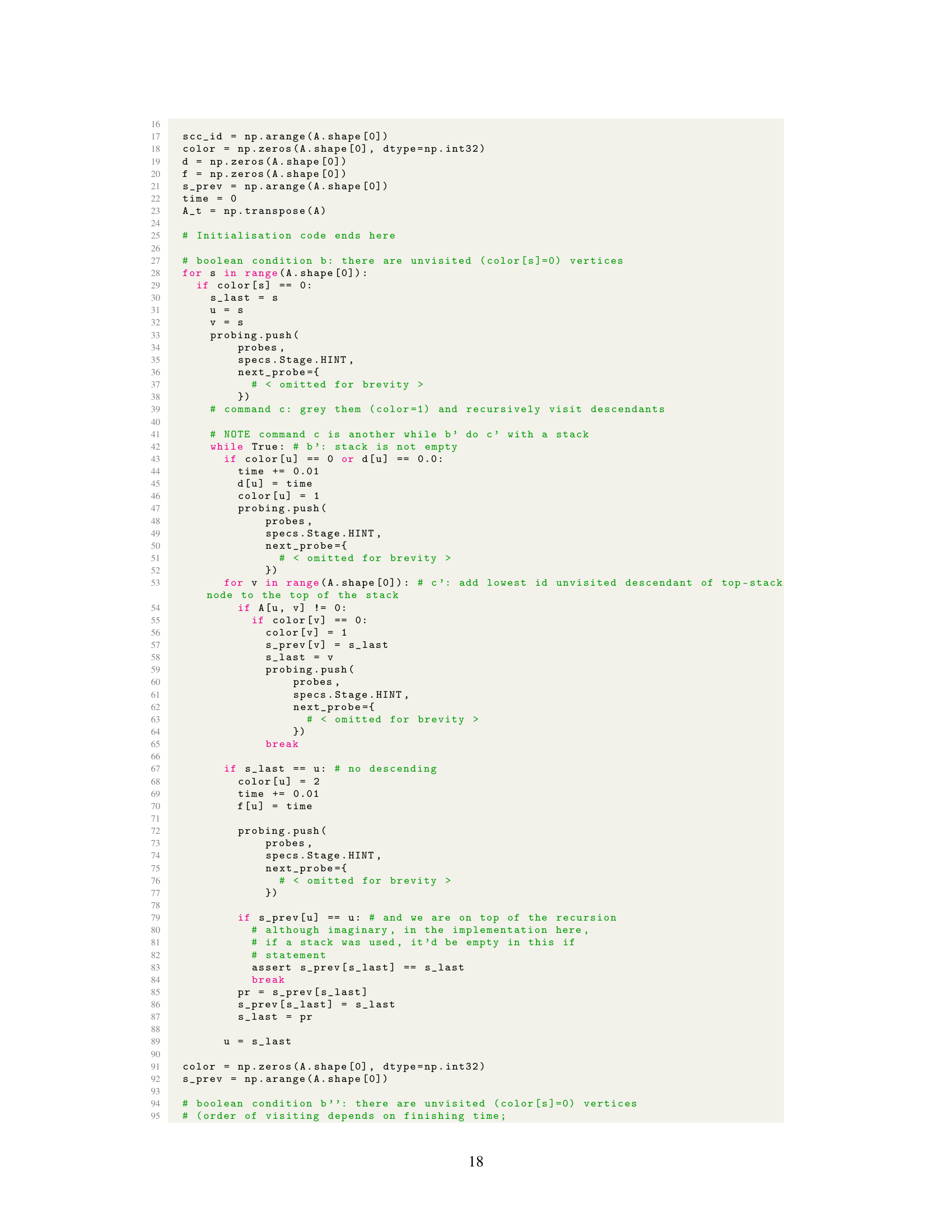

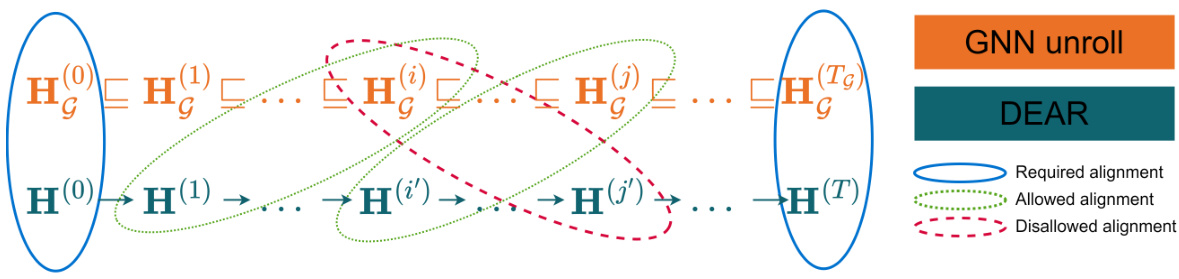

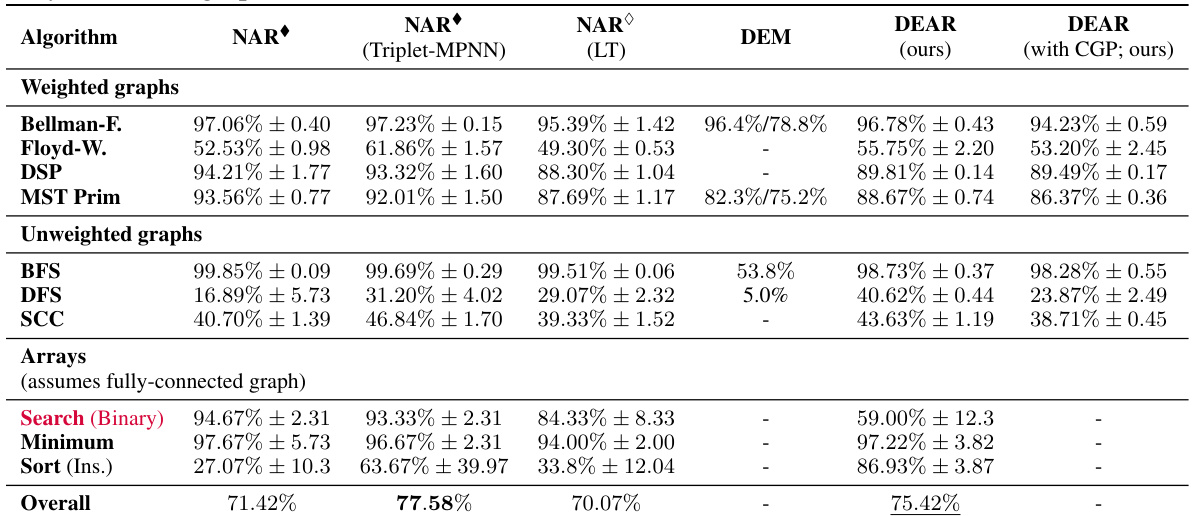

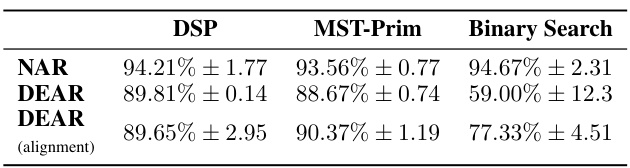

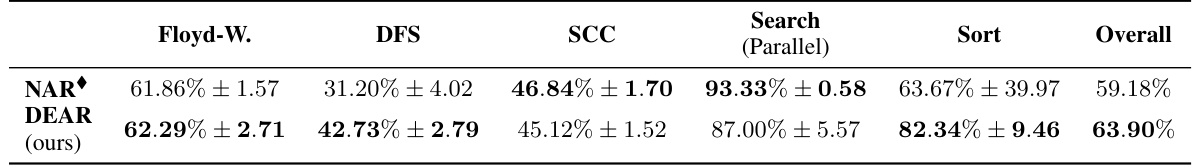

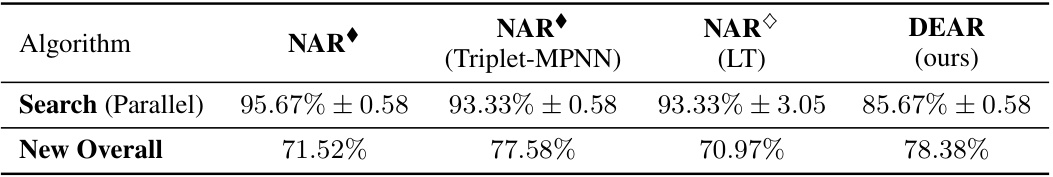

This table presents the test accuracy results for various algorithms across different models: NAR (with a standard and triplet-MPNN processor), NAR with learnt termination (LT), Deep Equilibrium Models (DEM), and the proposed Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoners (DEAR) with and without Cayley Graph Propagation (CGP). The table highlights the performance differences between these models, considering different algorithm categories (weighted graphs, unweighted graphs, and arrays). It also shows the impact of providing the ground truth number of steps during training and testing. The results allow for comparison of the proposed method with existing state-of-the-art techniques.

In-depth insights#

Equilibrium Reasoning#

The concept of ‘Equilibrium Reasoning’ in the context of algorithmic reasoning using neural networks centers on identifying the solution to an algorithm as a stable equilibrium point. Instead of explicitly simulating each step of an algorithm, this approach seeks to directly find the fixed point where further iterations do not alter the solution. This offers significant potential for increased efficiency because it avoids the iterative process inherent in traditional recurrent neural network approaches. The method’s effectiveness relies on the algorithm possessing an equilibrium property and the ability of the neural network to converge to it. Finding the equilibrium is often achieved through root-finding techniques, which may offer significant speed improvements over traditional step-by-step execution. However, the reliance on an equilibrium might restrict the applicability to specific algorithm classes. The work also highlights the importance of selecting suitable neural network architectures and regularization methods to achieve robust convergence and improve performance. Furthermore, the practical implementation and challenges of the equilibrium finding process are crucial considerations. This includes addressing issues like choosing appropriate solvers, defining convergence criteria, and handling cases where the algorithm lacks a well-defined equilibrium.

DEAR Architecture#

The DEAR (Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoning) architecture is a novel approach to neural algorithmic reasoning that leverages the power of deep equilibrium models (DEQs). Unlike traditional recurrent approaches that iteratively process information, DEAR directly solves for the equilibrium state of a system, significantly accelerating inference. The core of the architecture uses a processor, often a message-passing graph neural network (GNN), which operates on encoded node and edge features. This processor is implicitly defined by an equilibrium equation, enabling the model to learn algorithm execution without explicit iteration. The use of DEQs provides advantages in terms of memory efficiency and improved scalability, making DEAR particularly suitable for complex and large-scale algorithmic problems. DEAR’s key innovation lies in its implicit nature, allowing for efficient training and inference without explicit unrolling, a significant departure from previous NAR methods that required iterating over steps. Furthermore, the architecture’s flexibility permits the use of various GNN processors, adapting to different algorithm structures.

Alignment Strategy#

Aligning neural algorithmic reasoning (NAR) models with the execution trace of the algorithm they aim to emulate is crucial for performance. A well-defined alignment strategy is essential for successful training, ensuring the model learns the algorithm’s steps effectively and generalizes well to unseen inputs. The core challenge is to map the model’s internal states to specific steps in the algorithm’s execution path, accounting for potential variations in the number of steps and the model’s internal representation. Different alignment approaches exist, from explicit supervision at each step using intermediate states to implicit alignment guided by the algorithm’s inherent structure. The choice of alignment strategy depends on various factors, including the algorithm’s complexity, the model architecture, and available resources. A successful strategy must strike a balance between providing sufficient guidance for learning the correct execution flow and allowing the model the freedom to learn an optimal internal representation. Furthermore, robust alignment techniques should address out-of-distribution generalization, allowing the model to accurately execute the algorithm on inputs beyond the training distribution. The use of tools like dynamic programming or other optimization methods can refine alignment further, minimizing discrepancies between the model and the algorithm. Finally, a strong alignment strategy can enhance the interpretability of NAR models by highlighting the correspondence between the model’s internal workings and the algorithm’s logic.

CGP’s Impact#

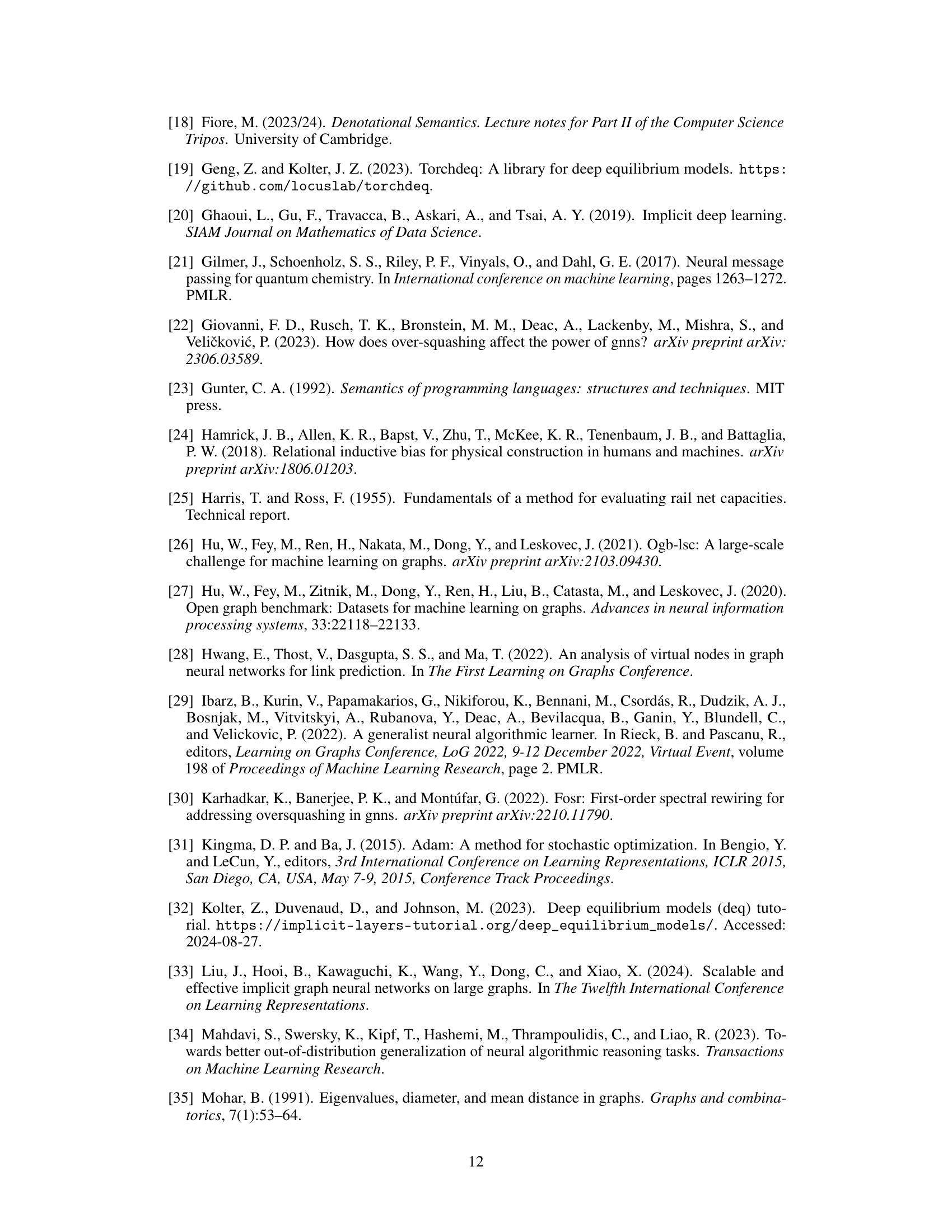

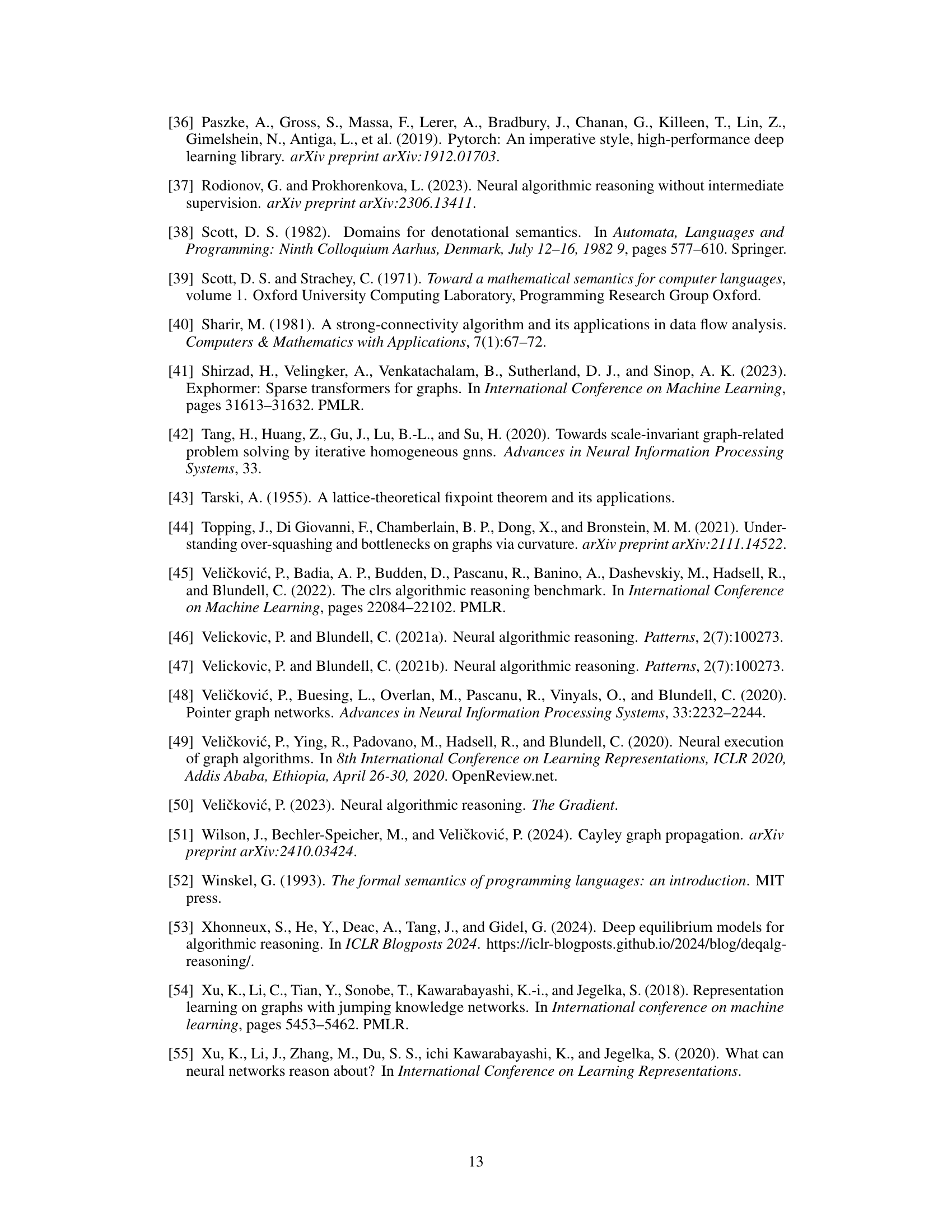

The research explored the impact of Cayley Graph Propagation (CGP) on deep equilibrium algorithmic reasoners (DEARs). Initial findings showed mixed results; while CGP sometimes improved convergence speed, it also occasionally led to reduced test accuracy. This suggests that CGP’s effectiveness is highly dependent on the specific algorithm and the graph structure. Further investigation is needed to fully understand the complex interplay between CGP, equilibrium finding, and the properties of different graph-based algorithms. The positive impact on convergence for some algorithms, however, highlights the potential of CGP as a method for enhancing the performance of equilibrium-based reasoning models. Future work could focus on refining CGP techniques to mitigate negative effects and better tailor them to specific algorithm classes. The nuanced results underscore the need for more in-depth analysis to fully realize the benefits of CGP in this emerging field.

Future Work#

The paper’s exploration of Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoning (DEAR) opens exciting avenues for future research. Improving the alignment algorithm is crucial; the current method, while showing promise, could benefit from more sophisticated techniques to better match DEAR and NAR trajectories, potentially integrating hints from intermediate algorithmic states. Investigating alternative graph structures beyond Cayley graphs for CGP is also important. While CGP demonstrated benefits, it also introduced challenges; exploring other graph augmentation methods to enhance long-range interactions within the GNN might yield better results. Finally, extending the applicability of DEAR to a wider range of algorithms, especially those not easily expressed as “while” loops, and addressing the issue of overfitting, particularly in tasks like binary search, remain key objectives. Further research into the theoretical underpinnings of DEAR, potentially using denotational semantics and domain theory to formalize its behavior, could provide valuable insights and pave the way for more robust and efficient equilibrium reasoners.

More visual insights#

More on figures

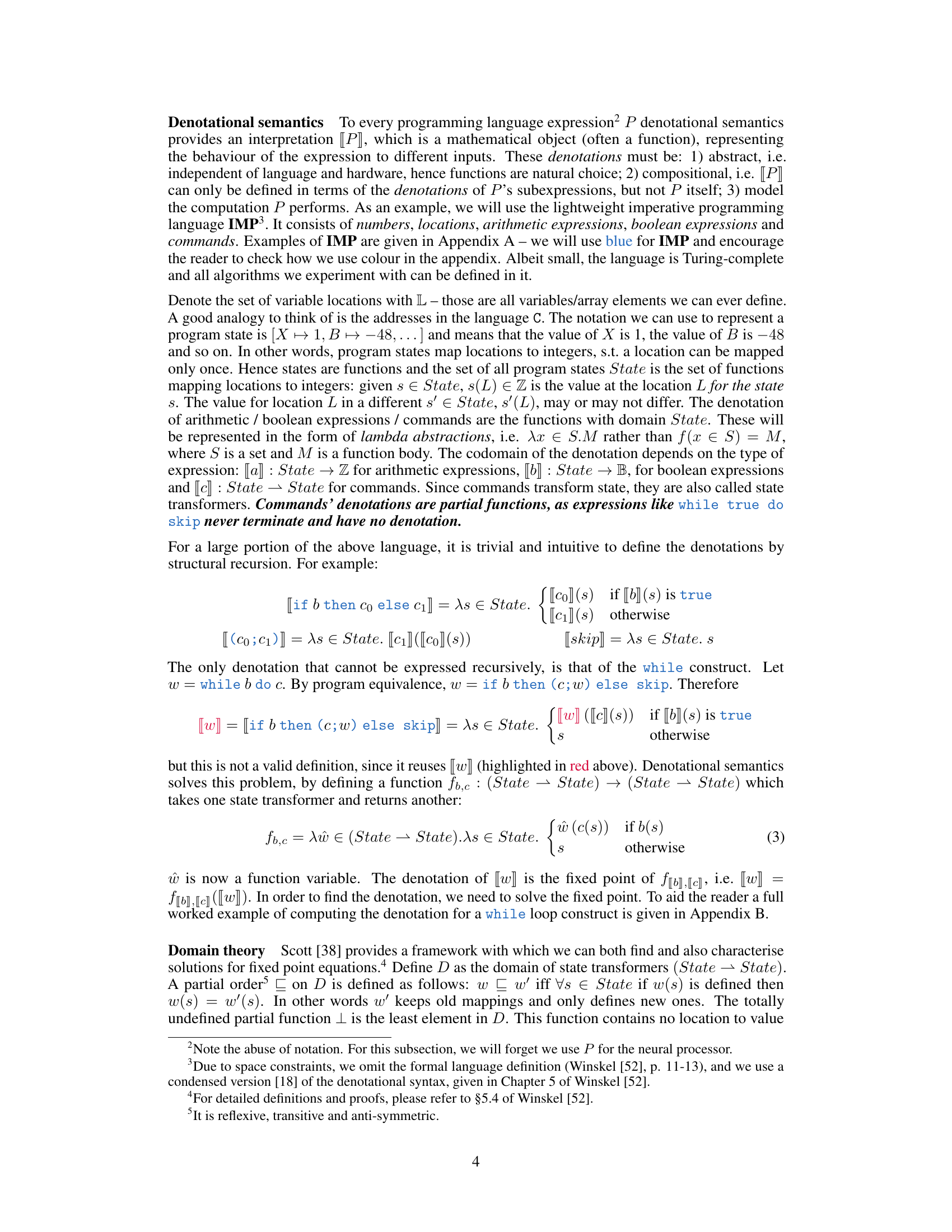

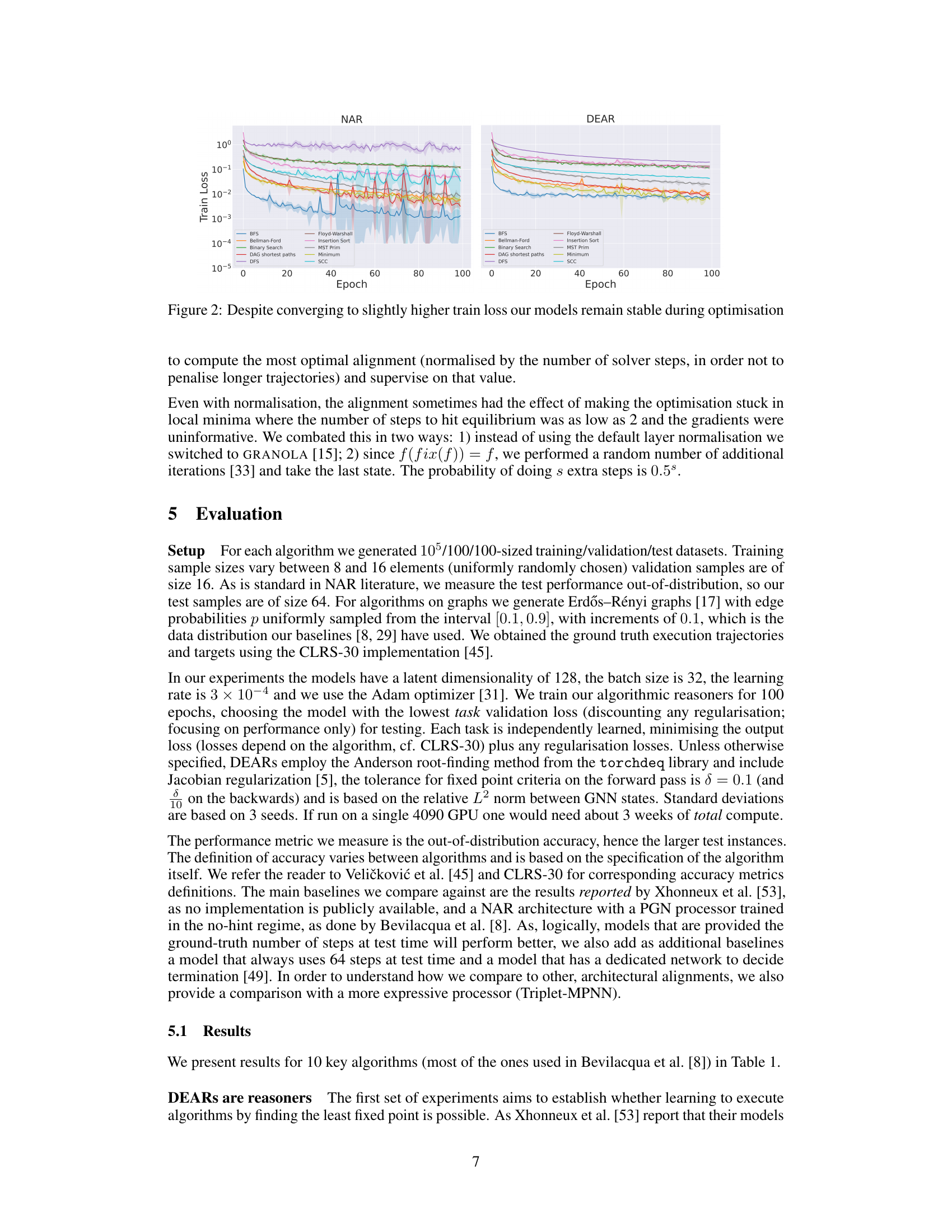

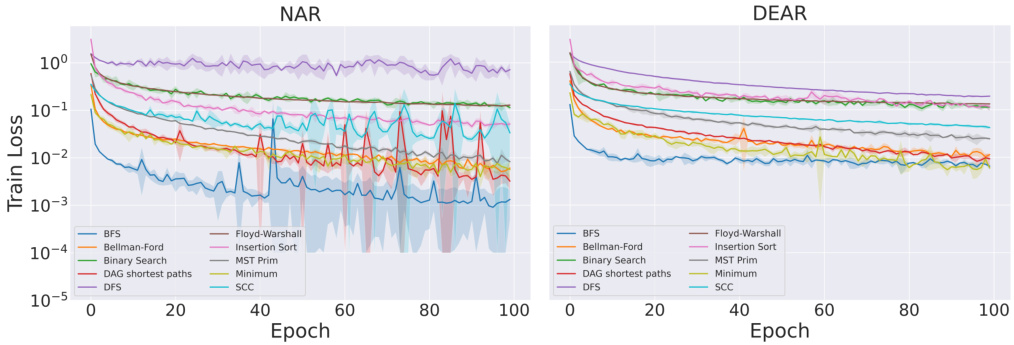

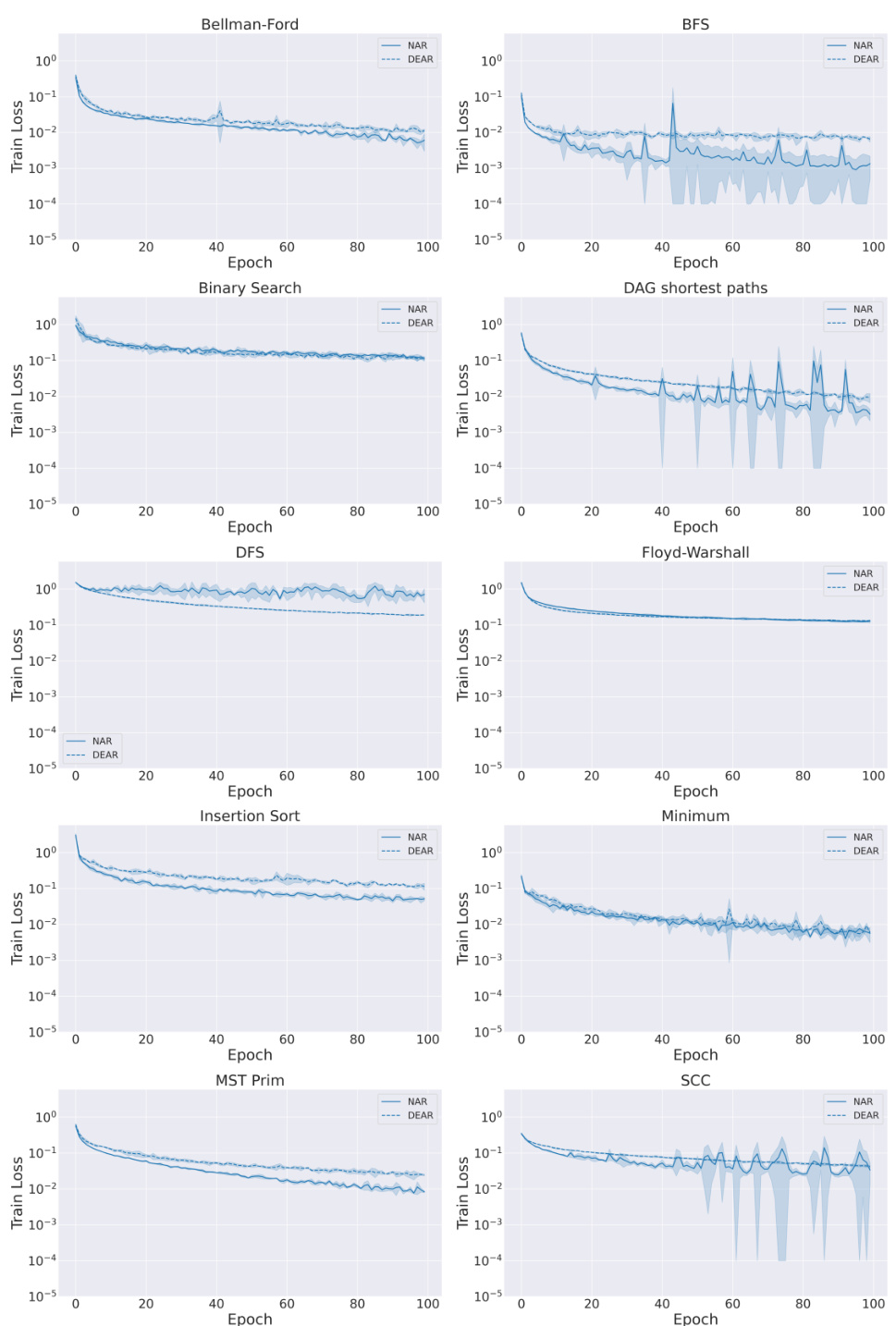

This figure shows a comparison of the training loss curves for NAR (Neural Algorithmic Reasoning) and DEAR (Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoners) models across ten different algorithms. The y-axis represents the training loss on a logarithmic scale, ranging from 10⁻⁵ to 10⁰. The x-axis represents the training epoch, from 0 to 100. For each algorithm, two lines are plotted, one for NAR and one for DEAR. The results indicate that the DEAR training loss consistently remains within one order of magnitude of the NAR training loss across all algorithms. This suggests that DEAR achieves comparable performance to NAR while having a different architecture and training approach.

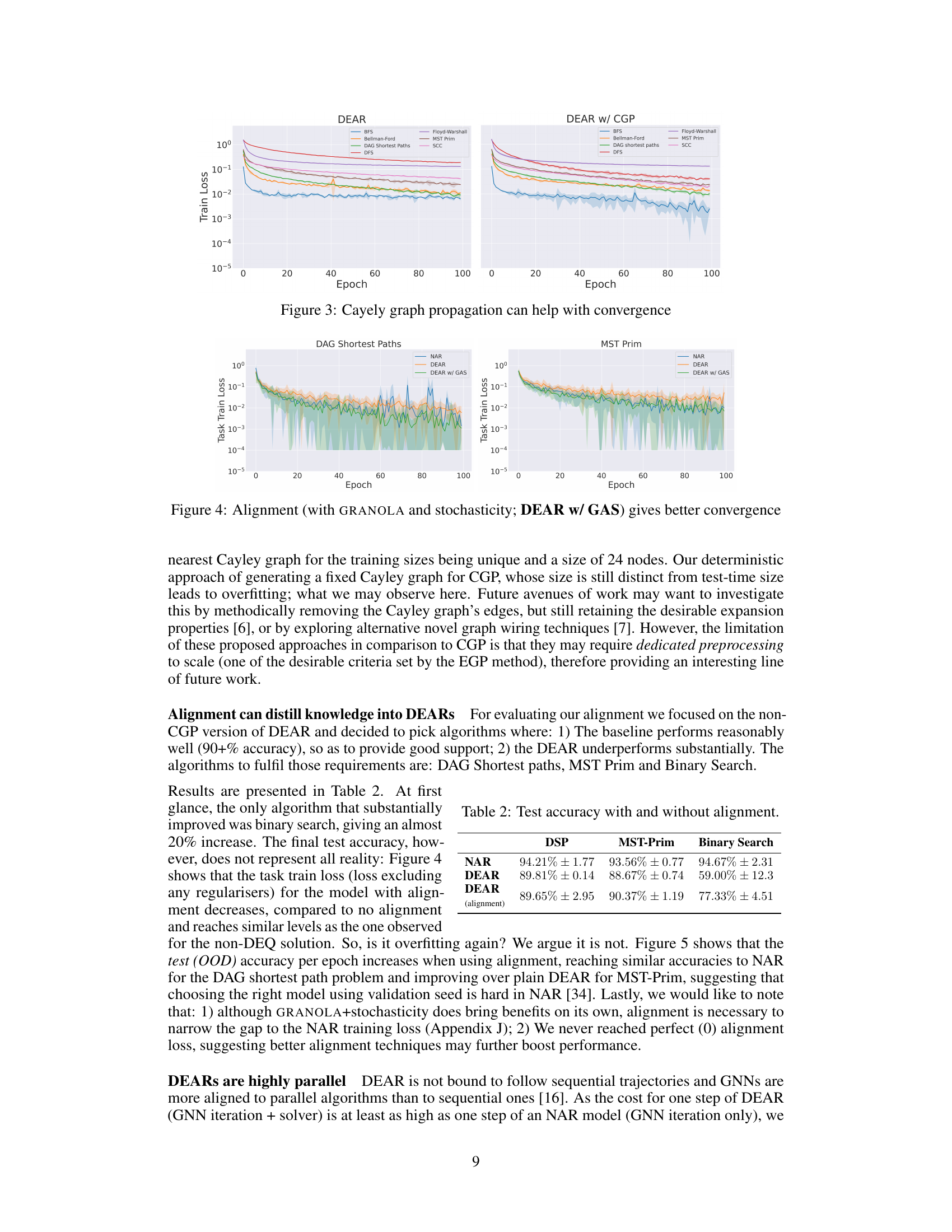

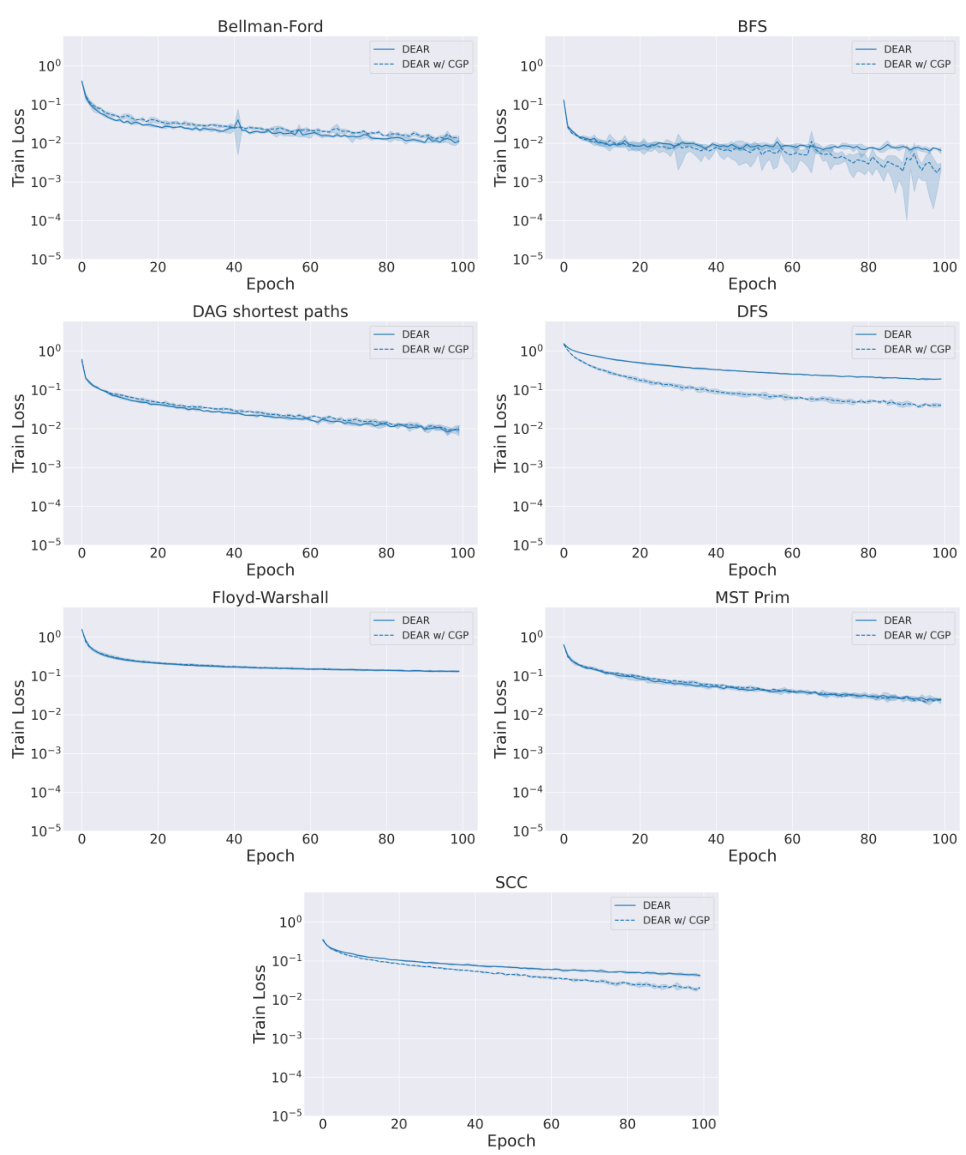

This figure shows a comparison of the training loss curves for DEAR models with and without Cayley Graph Propagation (CGP) across various algorithms. The plots show that for some algorithms, CGP led to lower loss, indicating potential benefit for convergence. For others, however, the effect was less pronounced or even slightly negative.

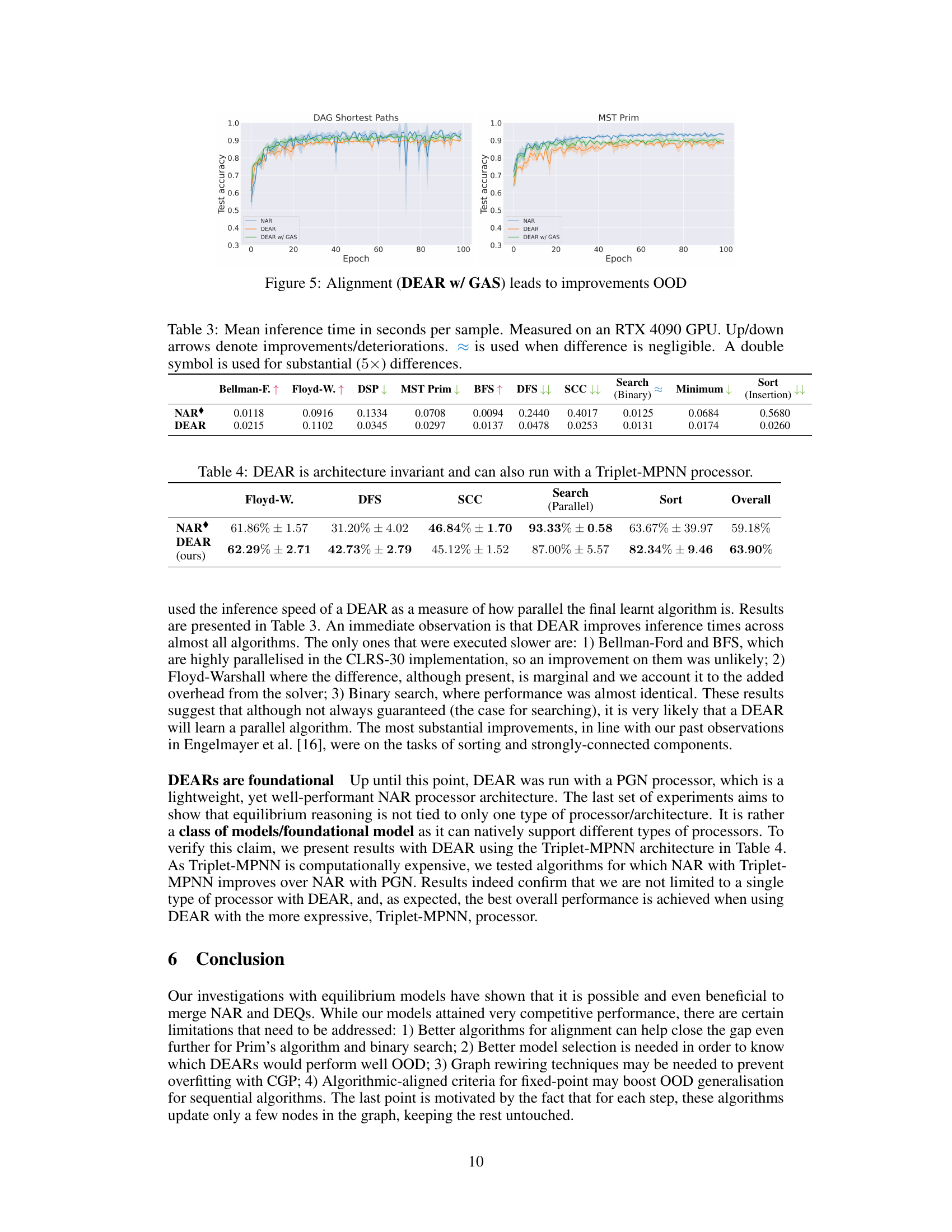

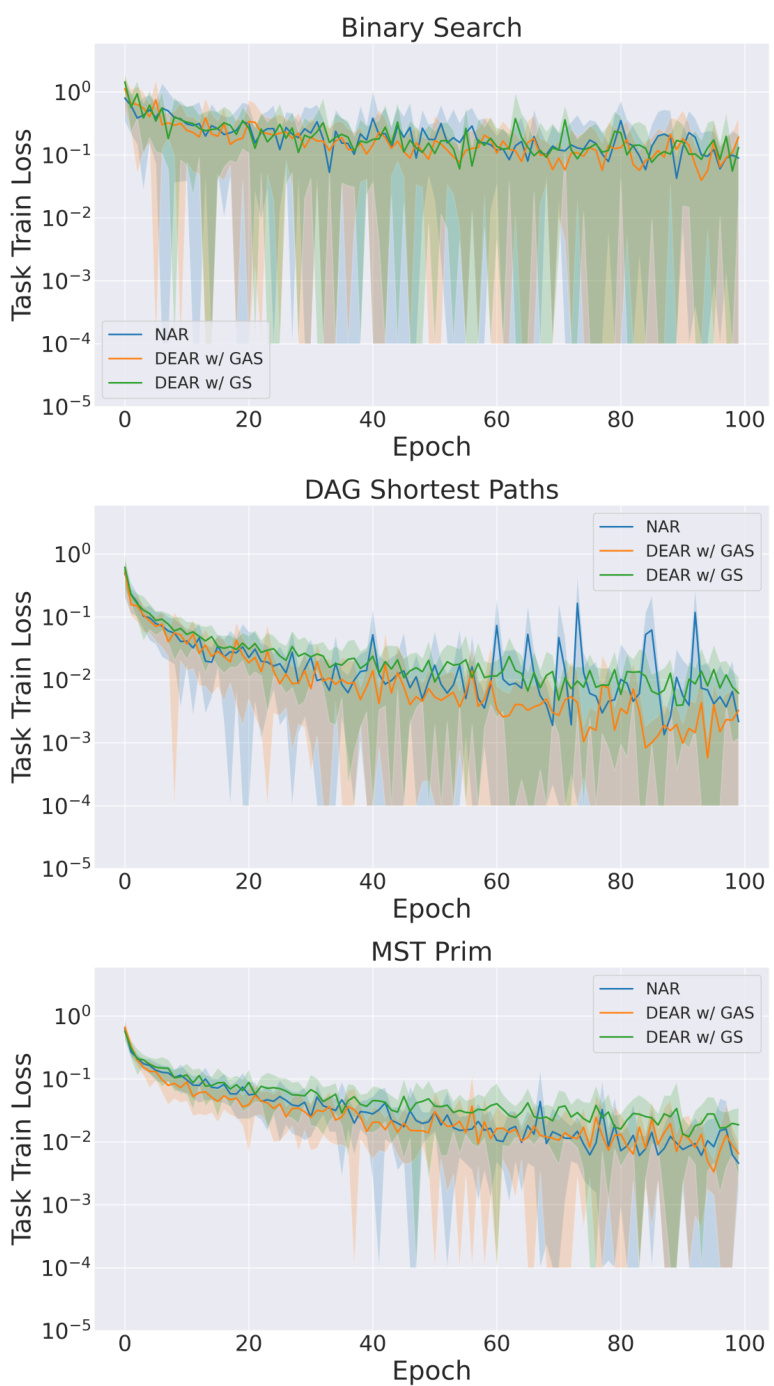

This figure shows a comparison of training loss curves for three different model variants across three algorithms: Binary Search, DAG Shortest Paths, and MST Prim. The ‘NAR’ line represents a standard Neural Algorithmic Reasoning (NAR) model. The ‘DEAR w/ GAS’ line represents a Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoner (DEAR) model with the addition of a Gating mechanism and stochasticity. The ‘DEAR w/ GS’ line represents a DEAR model with only stochasticity. The results suggest that using alignment (orange curves) leads to lower training loss compared to models without alignment (green), particularly for the DAG Shortest Paths and MST Prim algorithms. The use of stochasticity and GRANOLA (a type of layer normalization) further enhances the results, leading to closer convergence of the training loss.

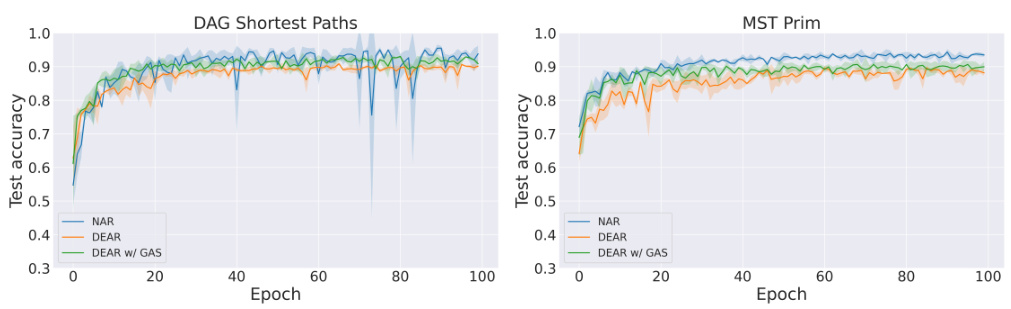

This figure displays the test accuracy over epochs for two algorithms: DAG Shortest Paths and MST Prim. Three model variations are compared: NAR (standard Neural Algorithmic Reasoning), DEAR (Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoner), and DEAR w/ GAS (DEAR with a Global Alignment Scheme). The graph shows that the alignment scheme (GAS) generally improves the test accuracy of the DEAR models, particularly in later epochs, suggesting it enhances out-of-distribution generalization performance.

This figure presents a detailed comparison of the training loss curves for both NAR (Neural Algorithmic Reasoning) and DEAR (Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoner) models across ten different algorithms. The y-axis represents the training loss on a logarithmic scale, highlighting the relative differences. The x-axis shows the number of training epochs. The key observation is that the training loss for DEAR consistently remains within one order of magnitude of the NAR loss across all algorithms, demonstrating comparable training performance. The log scale emphasizes the consistent proximity of the loss values between the two models, indicating that DEAR does not substantially deviate in terms of training loss compared to the more traditional NAR approach.

This figure shows the training loss curves for DEAR models both with and without Cayley Graph Propagation (CGP) across various algorithms from the CLRS-30 benchmark. The plot reveals that for some algorithms, CGP aids in achieving a lower training loss, suggesting that it can be beneficial for model convergence and overall performance. Conversely, for others, there’s no clear advantage or even a slight negative impact with CGP. This highlights that the effectiveness of CGP is algorithm-dependent and not universally beneficial for deep equilibrium algorithmic reasoning.

The figure shows the training loss curves for three different algorithms (Binary Search, DAG Shortest Paths, and MST Prim) using three different training methods: NAR (baseline), DEAR w/ GAS (DEAR with alignment, GRANOLA, and stochasticity), and DEAR w/ GS (DEAR with GRANOLA and stochasticity, but without alignment). The graphs clearly demonstrate that using alignment (DEAR w/ GAS) consistently results in lower training loss than using only GRANOLA and stochasticity without alignment (DEAR w/ GS), and often significantly lower training loss than the baseline NAR method. The use of both GRANOLA and stochasticity seems to help with the convergence of training loss.

More on tables

This table presents the test accuracy results for various algorithms and models, including NAR (with a Triplet-MPNN processor), NAR with learnt termination (LT), DEM (Deep Equilibrium Models), and the proposed DEAR (Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoners) with and without Cayley Graph Propagation (CGP). It highlights the performance differences between these models across various graph and array-based algorithms, indicating the impact of different model architectures and training strategies. The table also distinguishes between models trained with ground truth step information and those without, providing a comprehensive comparison of different approaches for Neural Algorithmic Reasoning (NAR).

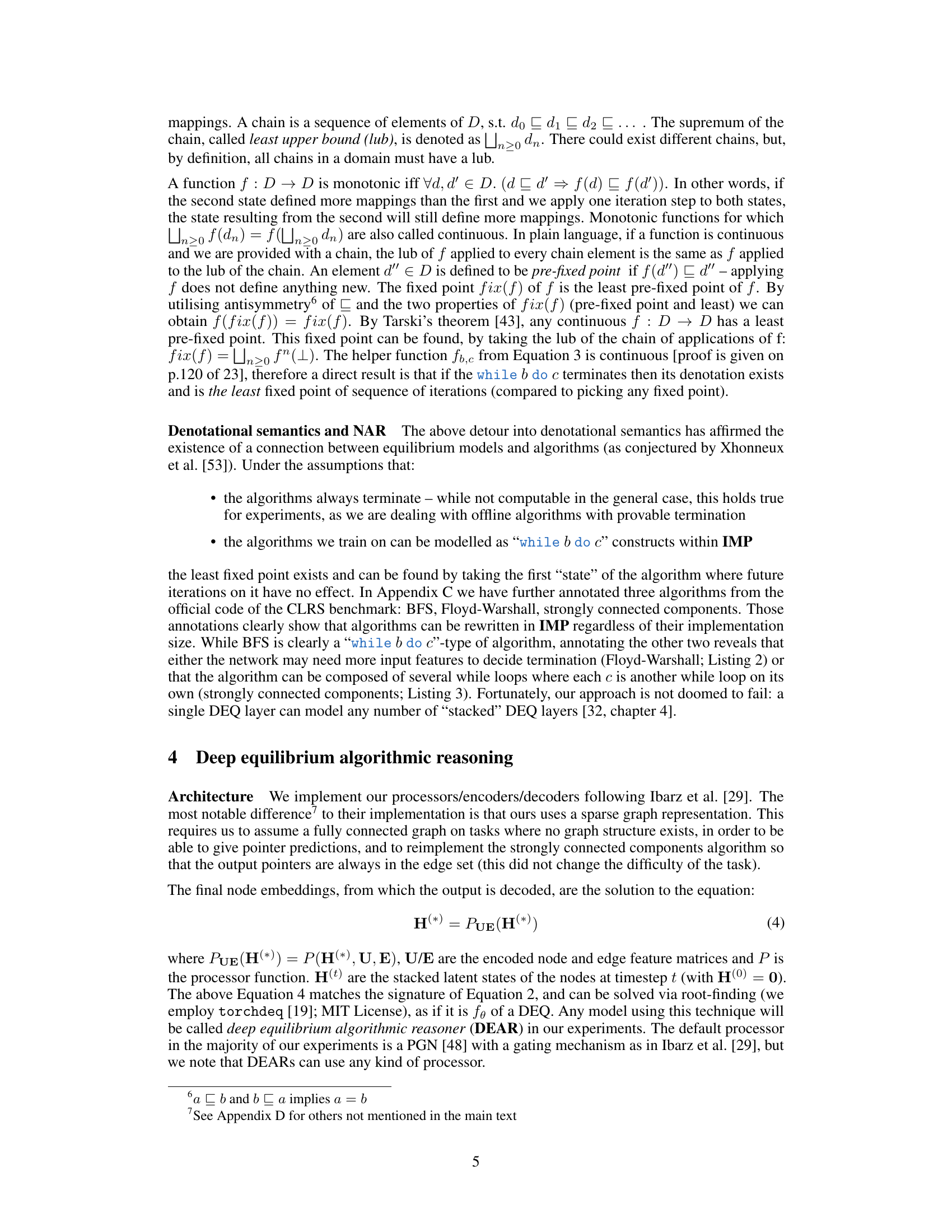

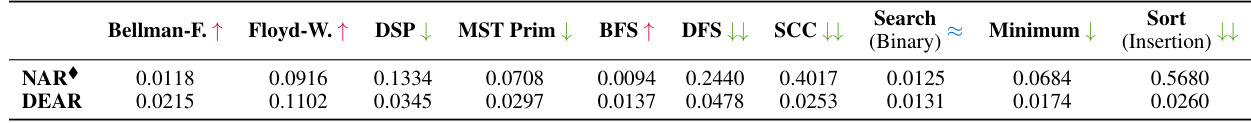

This table presents the mean inference time in seconds per sample for various algorithms using both NAR and DEAR models. The measurements were conducted on an RTX 4090 GPU. Upward-pointing arrows indicate that DEAR improved inference time compared to NAR; downward-pointing arrows indicate the opposite. The symbol ≈ denotes negligible differences in inference time, and a double symbol signifies substantial improvements (5x or greater).

This table presents the test accuracy results for various algorithms and models, comparing the performance of DEAR (Deep Equilibrium Algorithmic Reasoners) against other NAR (Neural Algorithmic Reasoning) models. It shows accuracy results for both weighted and unweighted graphs, as well as array-based tasks. The table includes different variations of DEAR and other methods for comparison. It highlights differences in performance based on providing ground truth step information at test time and whether the model learns to predict the termination condition itself.

This table presents the test accuracy results for different algorithms and models after addressing anomalies in the CLRS-30 binary search implementation. It compares the performance of four models: NAR, NAR with a Triplet-MPNN processor, NAR with learnt termination (LT), and the proposed DEAR model. The table shows improvements in the DEAR model’s overall accuracy after fixing the issues in the binary search algorithm. It highlights the improved competitiveness of the DEAR model compared to the Triplet-MPNN model.

Full paper#