↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

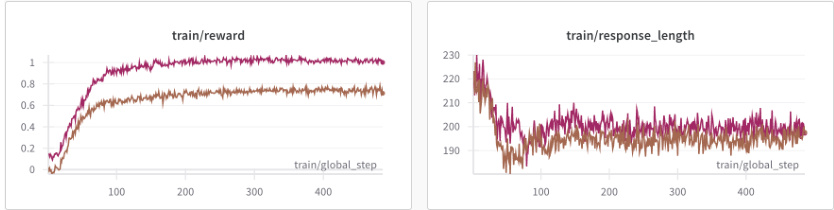

Aligning Language Models (LMs) with human preferences is crucial but challenging. Current Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) methods often struggle with efficient representation learning and fine-grained control. This research tackles these issues by proposing a novel contrastive, goal-conditioned training approach for reward models (RMs). This method increases the similarity of representations for preferred trajectories and decreases similarity for dispreferred ones. This improves both performance and steerability.

The proposed method significantly improves RM performance on challenging benchmarks (up to 0.09 AUROC improvement). This enhanced RM performance translates to better policy LM alignment. Further, the method’s ability to evaluate the likelihood of achieving goal states enables effective trajectory filtering (discarding up to 55% of generated tokens), leading to significant cost savings and improved model steerability. Fine-grained control is also achieved by conditioning on desired future states, demonstrating significant improvements in helpfulness and complexity compared to baselines. The research demonstrates a simple yet effective approach for improving both performance and controllability of LMs in RLHF, addressing critical challenges in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on reward model training and language model alignment. It introduces a novel contrastive, goal-conditioned approach that significantly improves reward model performance and enables fine-grained model control, opening new avenues for safer and more effective language model development. The findings on improved steerability and cost savings through trajectory filtering are particularly impactful for practical applications of RLHF.

Visual Insights#

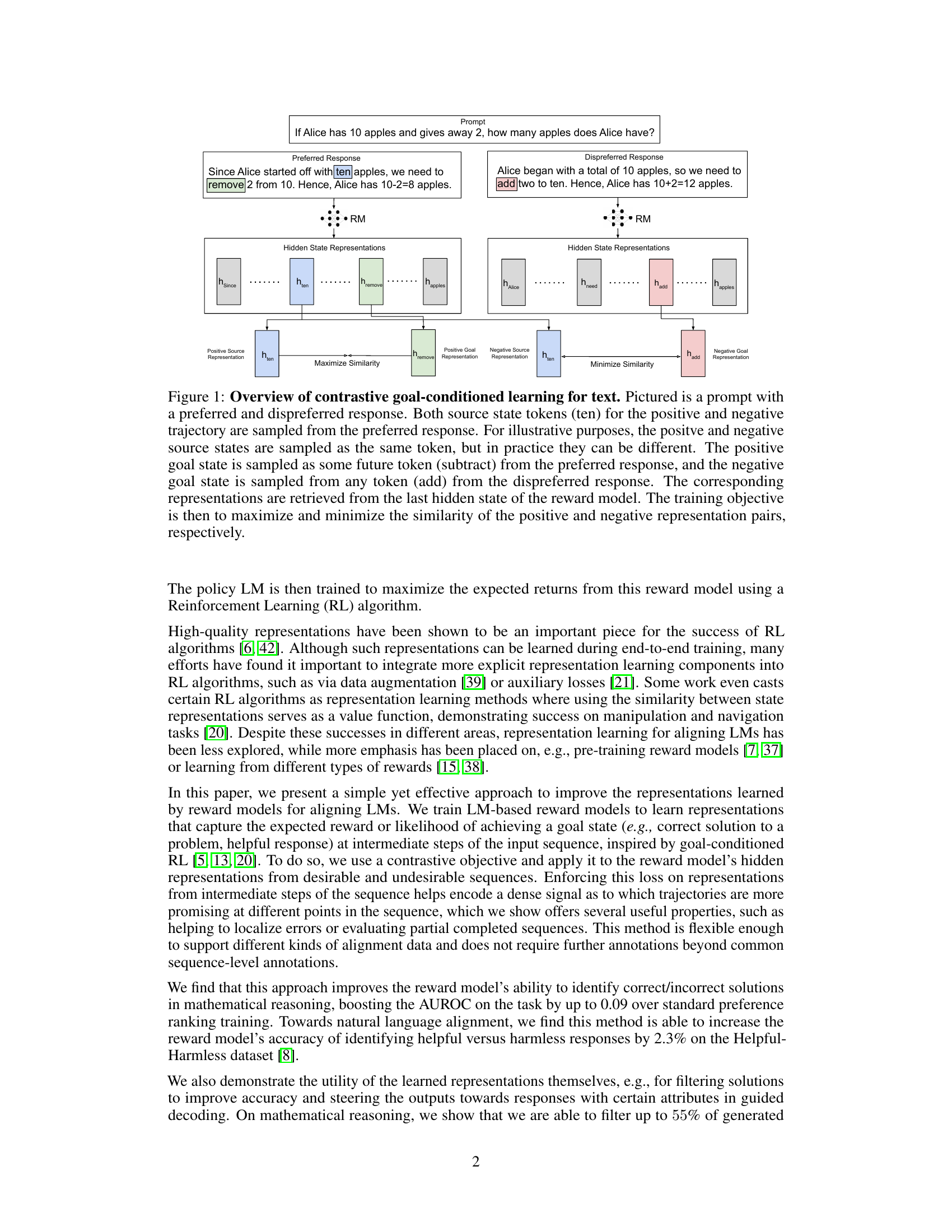

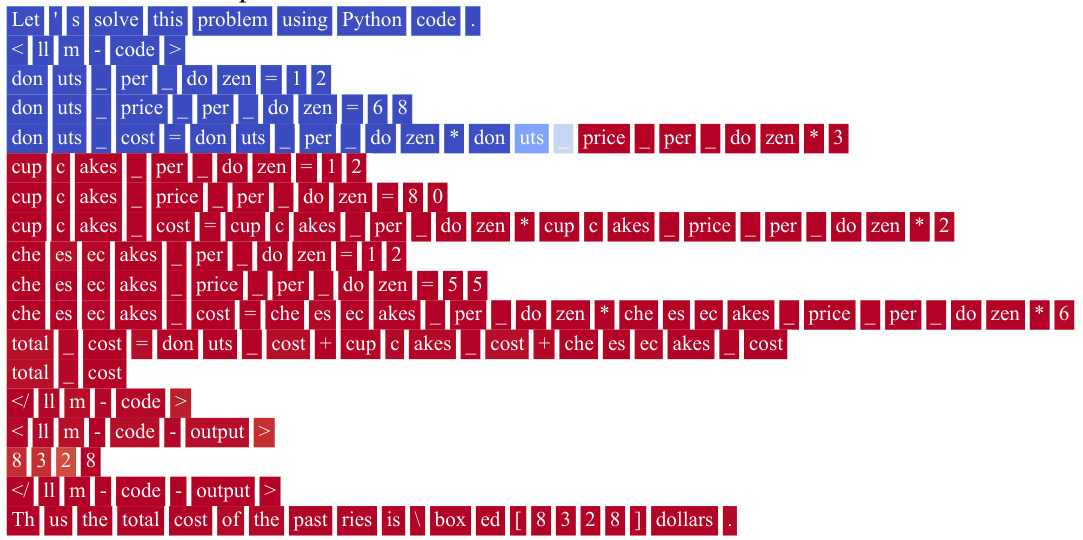

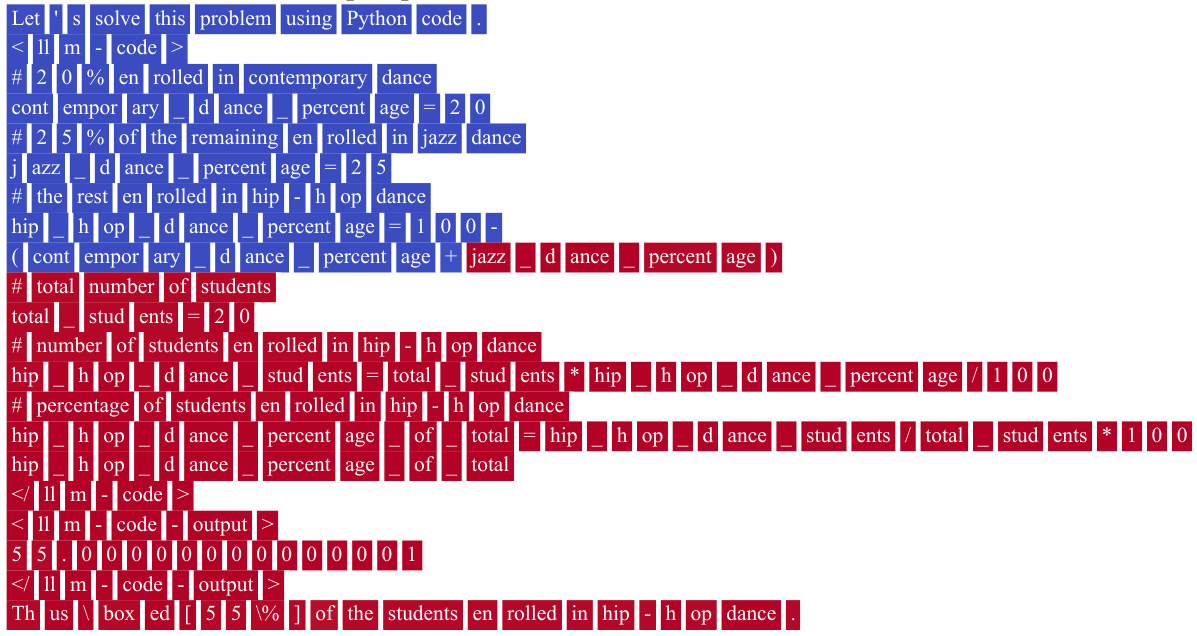

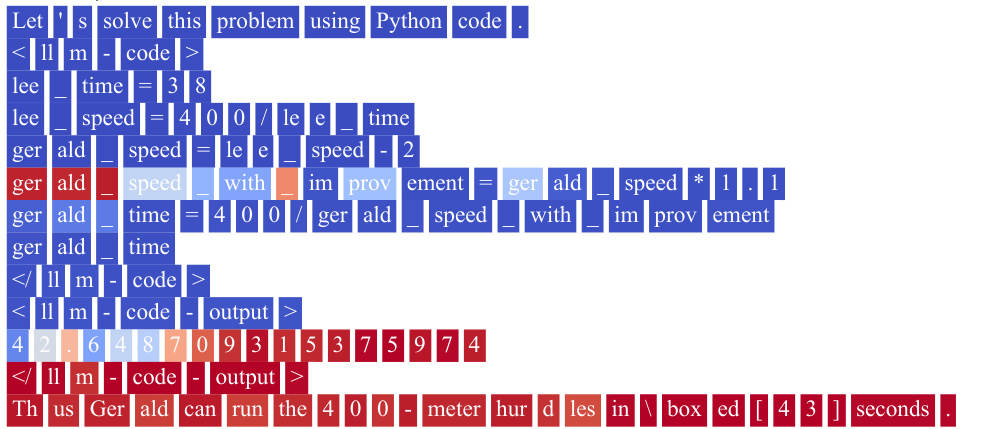

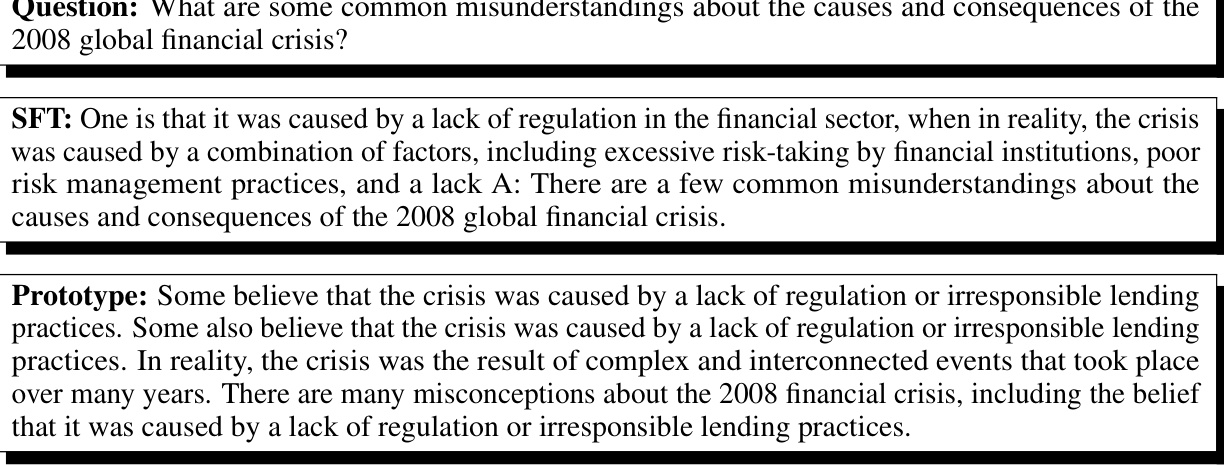

This figure illustrates the contrastive goal-conditioned learning approach used to train reward models. It shows how the model’s hidden state representations are used to increase similarity between preferred future states and decrease similarity between dispreferred future states. The goal is to improve the reward model’s ability to distinguish between good and bad responses.

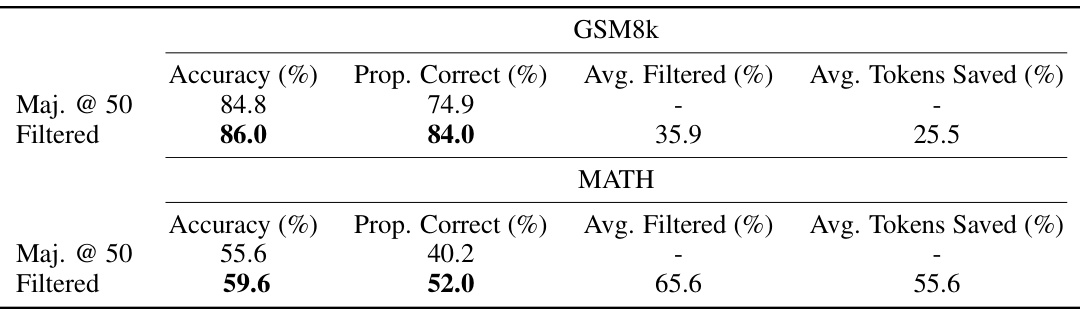

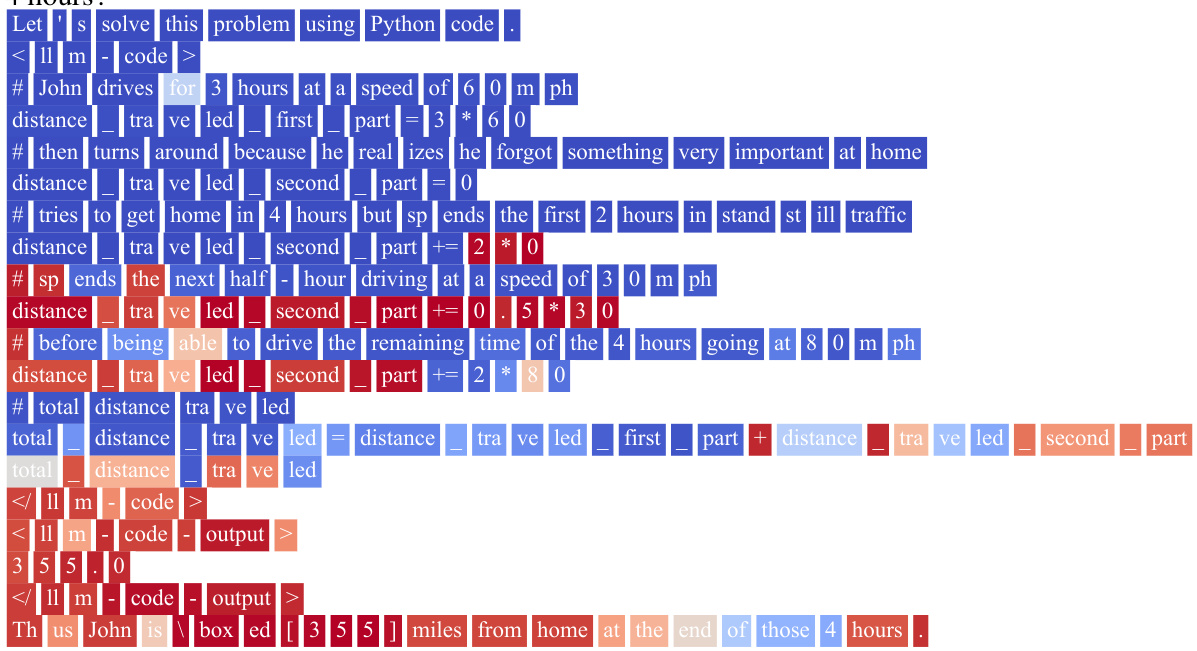

This table compares the performance of majority voting with Q-value filtering for mathematical reasoning tasks. It shows accuracy improvements after filtering and the percentage of tokens saved by filtering out low-scoring generations.

In-depth insights#

Contrastive RMs#

Contrastive reward models (RMs) represent a significant advancement in aligning language models (LMs) with human preferences. By employing a contrastive learning framework, these models learn to distinguish between preferred and dispreferred responses by increasing the similarity of representations for future states in preferred trajectories and decreasing similarity in dispreferred trajectories. This approach goes beyond simple scalar reward assignments, resulting in richer, more informative representations that better capture nuanced aspects of human preferences. The contrastive approach is particularly effective in improving steerability, allowing for finer-grained control over the LM’s output. This enhanced control enables techniques such as filtering low-quality generations and guiding the model towards specific desirable characteristics. The contrastive method’s success across diverse benchmarks highlights its generalizability and robustness, showcasing its potential to become a crucial component in future LM alignment strategies.

Goal-Conditioned RL#

Goal-conditioned reinforcement learning (RL) tackles the challenge of directing an agent towards a specific objective. Instead of relying solely on reward signals, goal-conditioned RL incorporates explicit goal representations into the agent’s decision-making process. This allows for more efficient learning, particularly in complex environments with sparse rewards. By explicitly defining the goal, the agent can better focus its learning efforts and avoid exploring irrelevant state-action pairs. Different methods exist for incorporating goals, such as providing the goal as an additional input to the agent’s policy or using a goal-conditioned value function. The advantages include improved sample efficiency, better generalization to unseen situations, and enhanced interpretability. However, challenges remain in handling complex goals, dealing with uncertainty about the goal, and ensuring robustness to noisy or incomplete goal information. The effectiveness of goal-conditioned RL hinges on the quality of goal representation and how effectively it’s integrated into the agent’s learning mechanism.

Q-function Learning#

Q-function learning, a core concept in reinforcement learning, aims to approximate the optimal action-value function, estimating the expected cumulative reward for taking a specific action in a given state. The paper leverages this by using a contrastive learning objective to learn representations within a reward model that implicitly encode Q-function estimates. By maximizing similarity between representations from desirable trajectories and minimizing similarity between representations from undesirable ones, the model learns to associate future states (goal states) with actions, implicitly estimating how well a given action will lead to those goals. This contrastive approach avoids the need for explicit Q-value estimation, improving efficiency. The effectiveness is validated through performance gains on both mathematical reasoning and natural language processing tasks, highlighting the broad applicability and power of this approach to aligning language models. A key innovation is the use of intermediate state representations, enabling fine-grained control and error detection. This shows that the learned representations capture valuable information not just about the final outcome, but also the progress towards the goal, enhancing the reward model’s ability to evaluate partial solutions and steer the model towards desired outcomes.

Improved Steerability#

Improved steerability in language models (LMs) signifies enhanced control over the generated text’s attributes. The paper likely explores methods to guide the model towards specific desired outputs by manipulating its internal representations or reward functions. This could involve goal-conditioned training, where the model learns to associate specific states with desired characteristics. A contrastive learning approach, as suggested by the title, may be used, contrasting desirable and undesirable outputs to refine the model’s understanding of preferred generation styles. The implications of improved steerability are significant, enabling safer and more beneficial applications. By providing a more fine-grained control mechanism, LMs can be better aligned to specific user needs, reducing the risk of generating harmful or unwanted content. The paper might present quantifiable metrics demonstrating the effectiveness of improved steerability, possibly showcasing how the generated text better conforms to user-specified goals or constraints. Ultimately, improved steerability advances the ability to harness the power of LMs for diverse tasks while mitigating potential risks.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving goal state representation is crucial; current methods rely on averages, potentially obscuring nuanced information vital for fine-grained control. Developing techniques to dynamically generate goal states based on the current context of the generated text would enhance the model’s adaptability. Investigating alternative contrastive learning objectives could lead to even more robust and informative representations. Exploring variations beyond cosine similarity, such as triplet loss or other distance metrics, warrants investigation. Finally, and importantly, integrating the Q-function estimates directly into the reinforcement learning process promises significant improvements. Instead of using the Q-values solely for filtering or steering, they could be incorporated as an additional reward signal within the RL algorithm, leading to potentially more efficient and effective policy learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

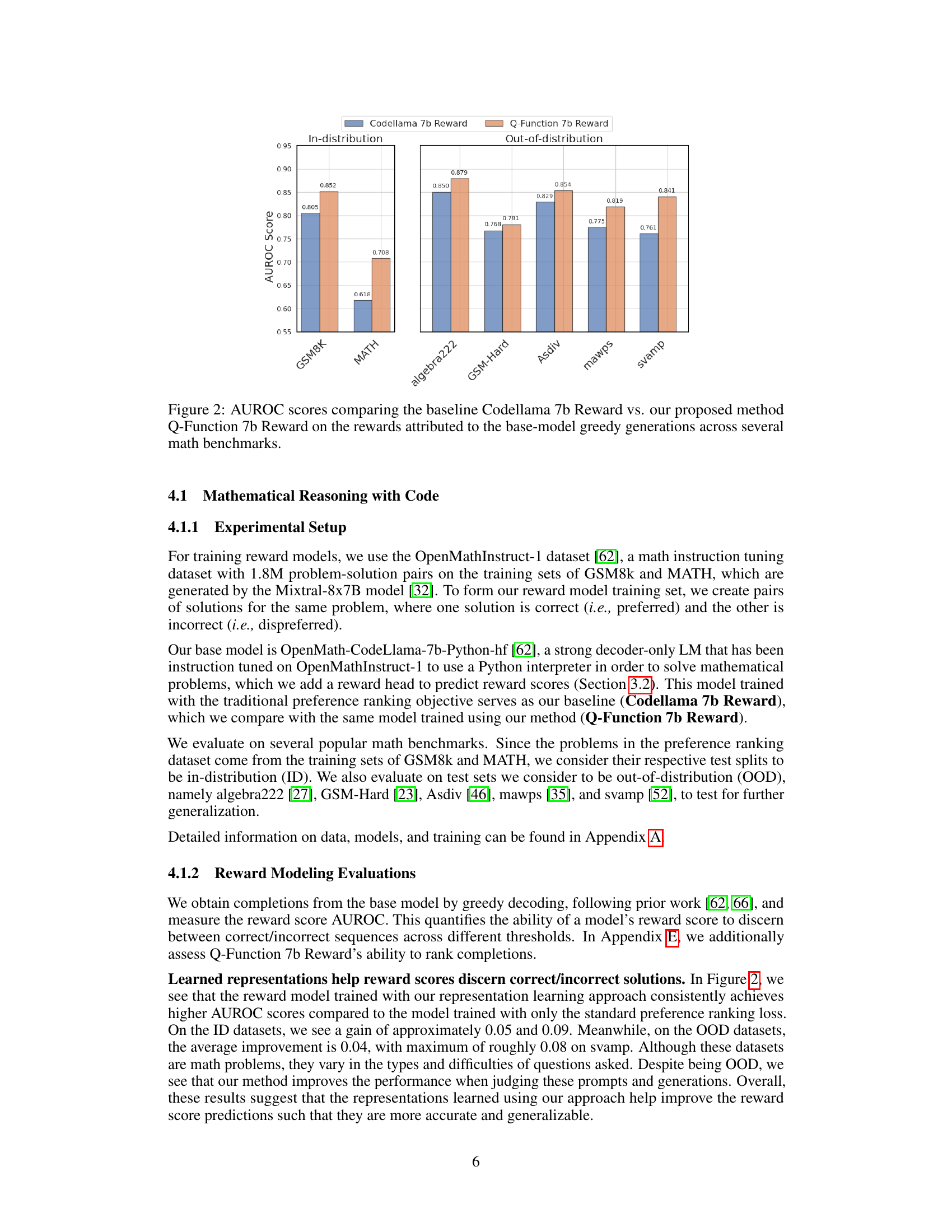

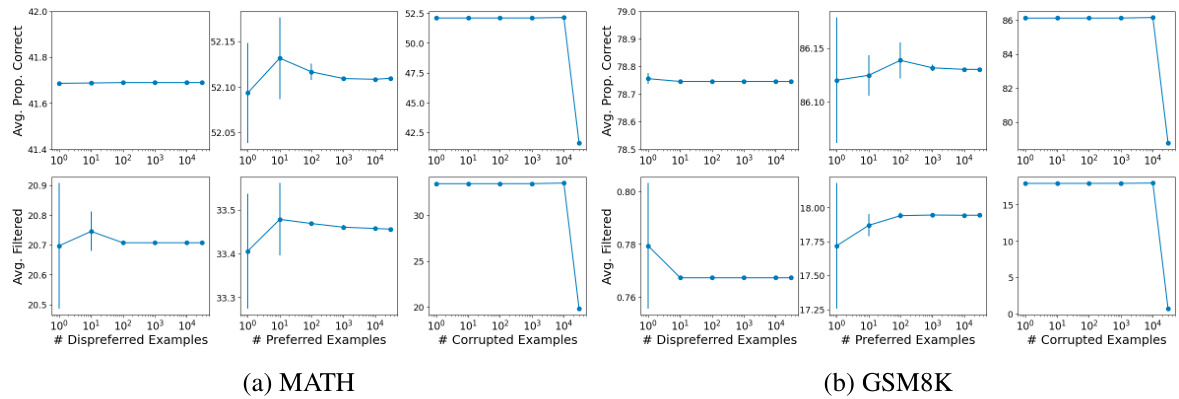

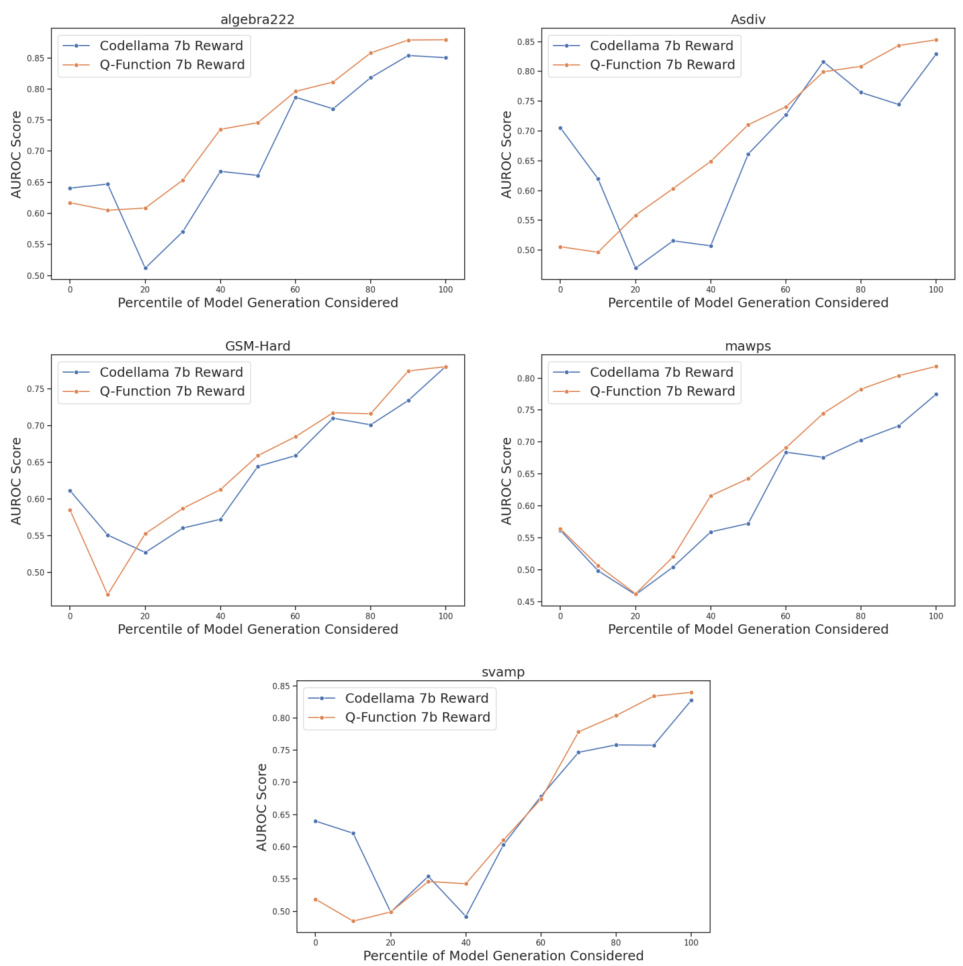

This figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two reward models: the baseline Codellama 7b Reward model and the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward model. The AUROC scores are calculated for each model’s ability to distinguish between correct and incorrect solutions generated by a base model across multiple mathematical reasoning benchmarks (GSM8k, MATH, algebra222, GSM-Hard, Asdiv, mawps, and svamp). The results show that the Q-Function 7b Reward model consistently outperforms the baseline Codellama 7b Reward model on all benchmarks, indicating that the proposed contrastive goal-conditioned training improves the reward model’s ability to evaluate the quality of generated solutions.

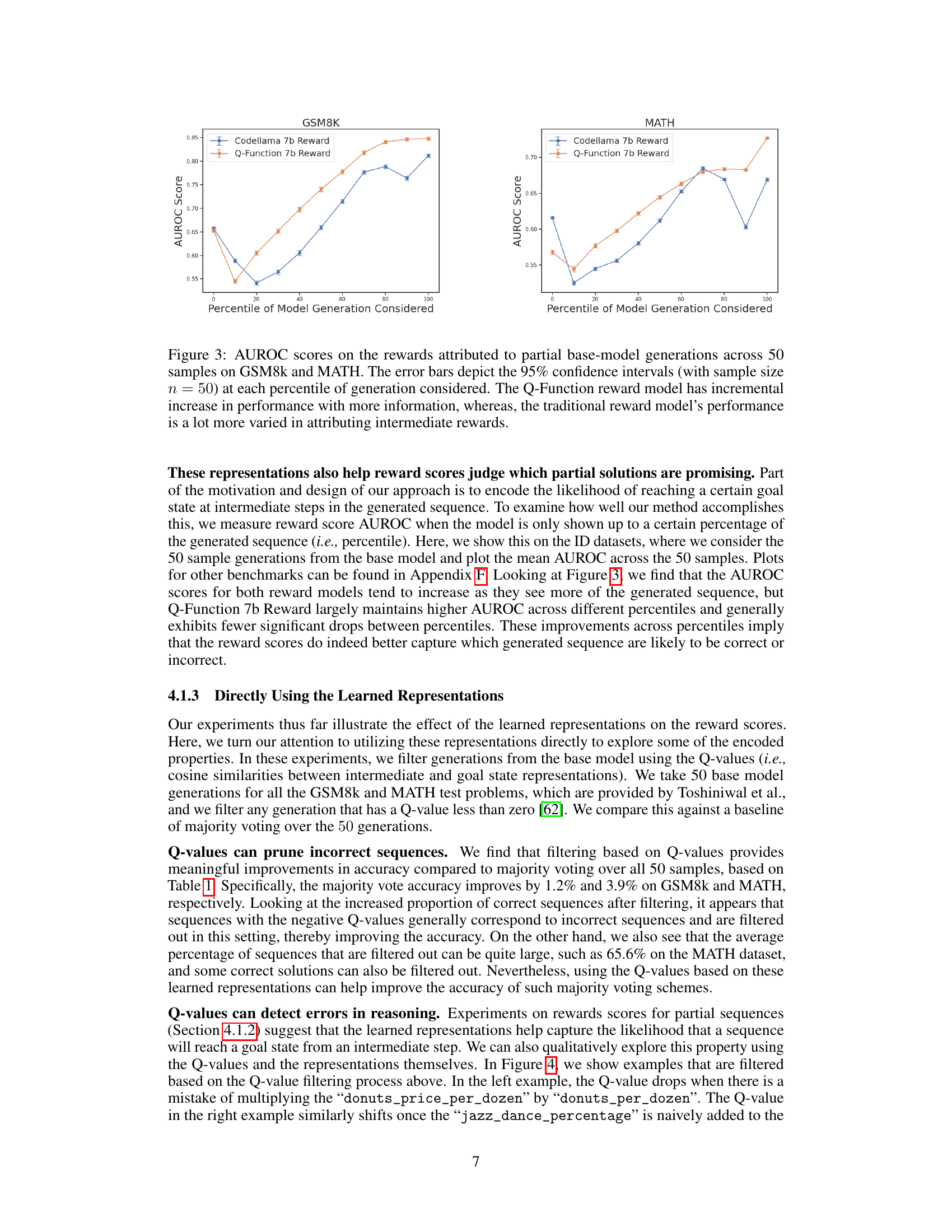

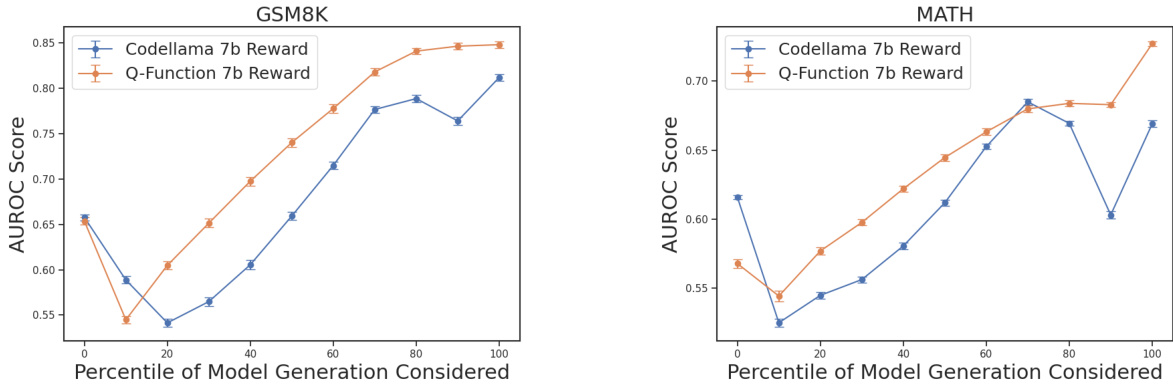

This figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two different reward models (Codellama 7b Reward and Q-Function 7b Reward) when evaluating partial generations on the GSM8K and MATH datasets. The x-axis represents the percentage of the generated sequence considered, while the y-axis shows the AUROC score. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval, indicating the variability in the results. The plot demonstrates that the Q-Function reward model exhibits a consistent and incremental improvement in AUROC as more of the generated sequence is considered, while the Codellama 7b Reward model shows more variability. This suggests that the Q-Function model’s learned representations better capture the likelihood of achieving a goal state at intermediate steps.

This figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two reward models: the baseline Codellama 7b Reward and the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward. The AUROC scores are calculated based on the rewards assigned to greedy generations of a base model across multiple mathematical reasoning benchmarks. The Q-Function model shows significant improvements in AUROC compared to the baseline model across various benchmarks, indicating better performance in distinguishing correct from incorrect solutions.

The figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two reward models (Q-Function 7b Reward and Codellama 7b Reward) when evaluating partial generations (i.e., only a certain percentage of the generated sequence is considered). The x-axis represents the percentage of the generated sequence considered, and the y-axis represents the AUROC score. The Q-Function model shows a consistent improvement in AUROC as more of the sequence is considered, while the performance of the Codellama model fluctuates more. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

This figure compares the performance of two reward models (Codellama 7b Reward and Q-Function 7b Reward) on several math benchmarks. The AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) scores are shown for each benchmark. The Q-Function 7b Reward model, which is the proposed model in the paper, consistently outperforms the baseline Codellama 7b Reward model across all benchmarks.

The figure presents a bar chart comparing the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores of two reward models: the baseline Codellama 7b Reward and the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward. The AUROC scores are shown for several math benchmarks, including GSM8K, MATH, algebra222, GSM-Hard, Asdiv, mawps, and svamp. The chart visually demonstrates the improvement in performance achieved by the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward model across these benchmarks.

The figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two reward models on several mathematical reasoning benchmarks. The baseline model is Codellama 7b Reward, while the proposed model is Q-Function 7b Reward. The AUROC scores represent how well each model can distinguish between correct and incorrect solutions generated by a base language model. The higher the AUROC score, the better the performance. The benchmarks shown include GSM8K, MATH, algebra222, GSM-Hard, Asdiv, mawps, and svamp, illustrating the performance across both in-distribution and out-of-distribution datasets. The results show consistent improvements across all benchmarks using the Q-Function 7b Reward method.

This figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two reward models: the baseline Codellama 7b Reward model and the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward model. The AUROC scores are calculated on the rewards assigned by each model to the greedy generations from a base language model across multiple math benchmarks (GSM8k, MATH, algebra222, GSM-Hard, Asdiv, mawps, and svamp). The results show that the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward model consistently achieves higher AUROC scores than the baseline, indicating an improved ability to distinguish between correct and incorrect solutions.

This figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores of two reward models on various mathematical reasoning benchmarks. The baseline model is Codellama 7b Reward, and the proposed model is Q-Function 7b Reward. The AUROC scores reflect the models’ ability to distinguish between correct and incorrect solutions generated by a base language model. The comparison demonstrates the improved performance of the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward model across several benchmarks, indicating its effectiveness in improving the quality of generated responses.

This figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two reward models: the baseline Codellama 7b Reward model and the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward model. The AUROC scores are calculated based on the rewards assigned by each model to the greedy generations from a base model. The comparison is done across multiple mathematical reasoning benchmarks to evaluate the performance of the two models in distinguishing correct from incorrect solutions.

This figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores of two reward models on several mathematical reasoning benchmarks. The baseline model is Codellama 7b Reward, while the proposed model is Q-Function 7b Reward. The AUROC scores reflect the models’ ability to distinguish between correct and incorrect solutions generated by a base language model. The results show the improved performance of the Q-Function 7b Reward model across the benchmarks, demonstrating its effectiveness in identifying correct solutions.

This figure compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two different reward models when evaluating partial generations (i.e., only a portion of the generated sequence is considered). The x-axis represents the percentage of the generated sequence considered for scoring, ranging from 0% to 100%. The y-axis shows the AUROC scores. Two reward models are compared: the baseline Codellama 7b Reward model and the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward model. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. The results demonstrate that the Q-Function model consistently achieves higher AUROC scores and shows a more stable and incremental improvement as more of the sequence is provided. In contrast, the baseline model exhibits greater variability in its performance and does not demonstrate as consistent an improvement.

The figure shows the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for two different reward models: the baseline Codellama 7b Reward and the proposed Q-Function 7b Reward model. The AUROC scores are calculated for several mathematical reasoning benchmarks, comparing the performance of both models in assigning rewards to the greedy generation from a base model.

This figure compares the performance of two reward models, Codellama 7b Reward (baseline) and Q-Function 7b Reward (proposed), on several mathematical reasoning benchmarks. The AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) score is used to evaluate the models’ ability to distinguish between correct and incorrect solutions generated by a base model. The results indicate that the Q-Function 7b Reward model, which incorporates a contrastive goal-conditioned training approach, achieves higher AUROC scores compared to the baseline model across various benchmarks.

More on tables

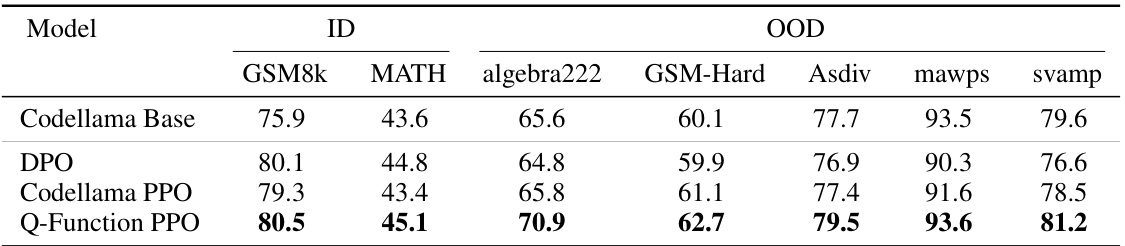

This table compares the accuracy of policy models trained using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) with different reward models: a preference-ranking reward model and the proposed Q-Function reward model. It shows the average accuracy across four independent runs for both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) datasets. The results are compared to a baseline model and Direct Preference Optimization (DPO). The full table with confidence intervals is available in Appendix Table 6.

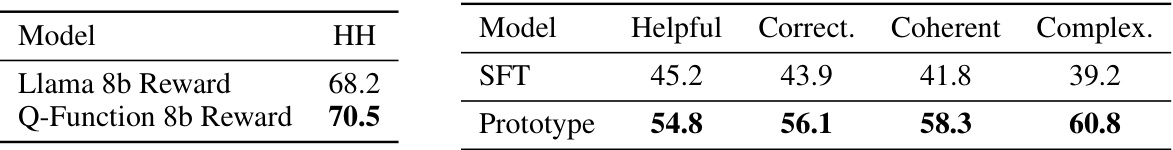

This table presents a comparison between different approaches for natural language alignment. Part (a) shows that the Q-function reward model outperforms the baseline Llama 8b reward model in terms of accuracy on the Helpful-Harmless dataset. Part (b) demonstrates the effectiveness of using the Q-function model representations for guided decoding, showing improvements in helpfulness, correctness, coherence, and complexity compared to supervised fine-tuning (SFT).

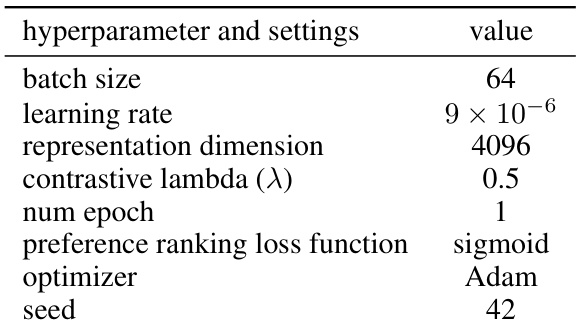

This table shows the hyperparameters used for training the reward model. The hyperparameters include batch size, learning rate, representation dimension, contrastive lambda, number of epochs, the preference ranking loss function, the optimizer used, and the random seed. These settings were used to train both the baseline reward model and the Q-Function reward model, as well as any reward model ablations.

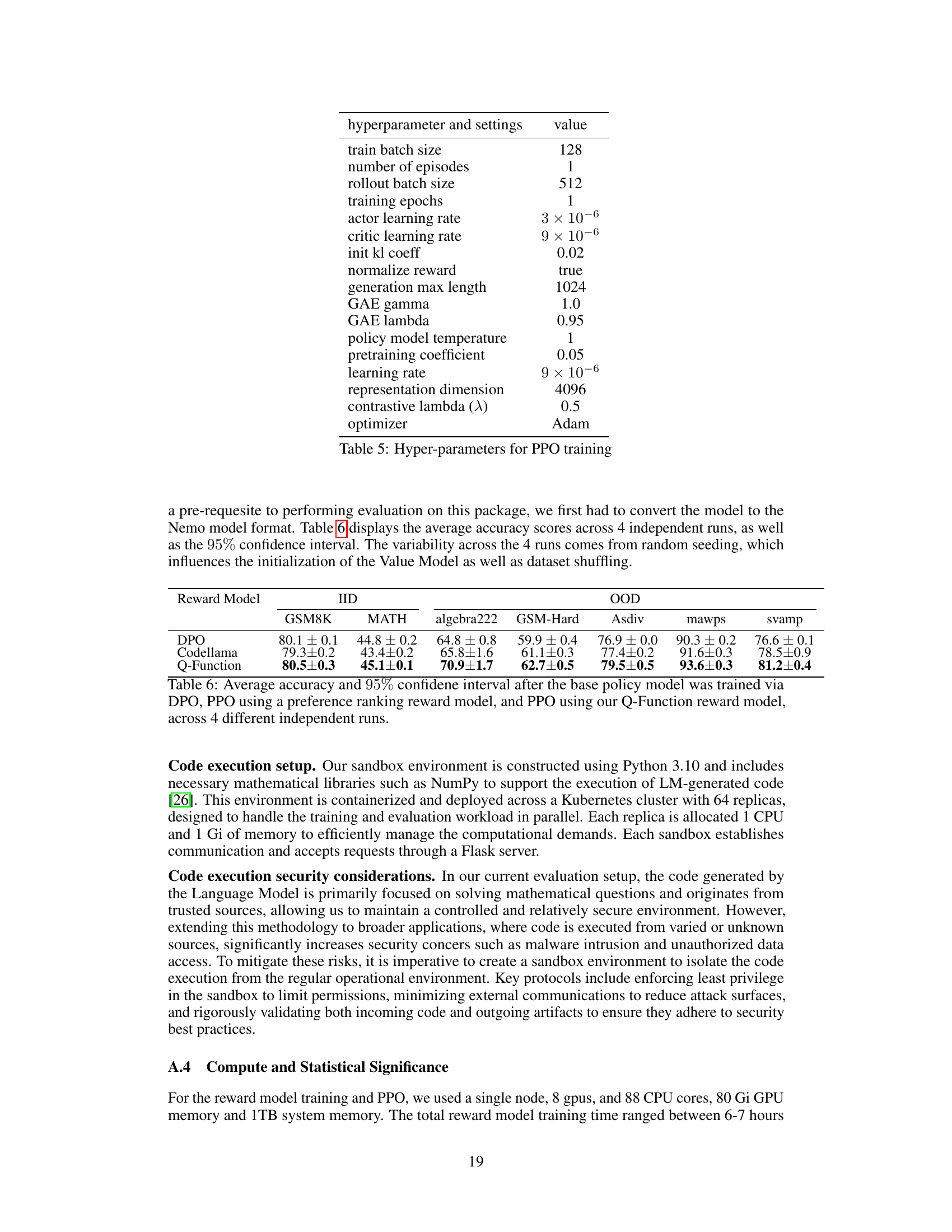

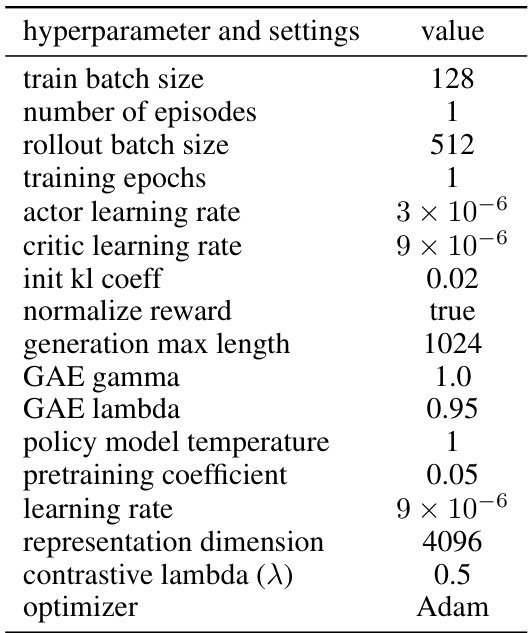

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the policy model using the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm. The hyperparameters control various aspects of the training process, including batch sizes, learning rates, reward normalization, and the generation length of sequences. The table provides values for each hyperparameter used in the experiments described in the paper. Note that the representation dimension refers to the dimensionality of the hidden state vectors used in the reward model.

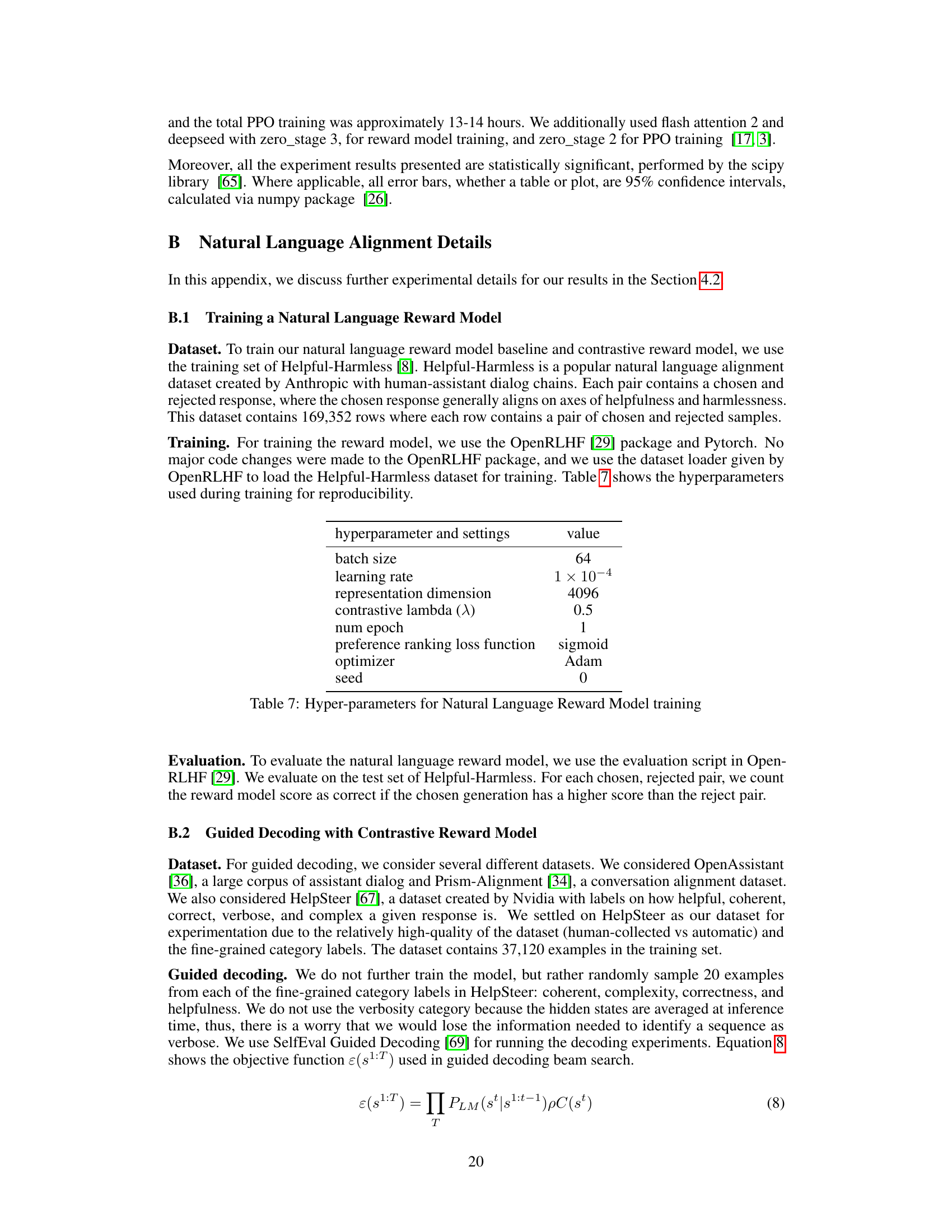

This table compares the performance of three different methods for training a policy language model using reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF). The methods are: Proximal Policy Optimization (DPO), RLHF with a standard preference-ranking reward model (Codellama PPO), and RLHF with the proposed goal-conditioned Q-function reward model (Q-Function PPO). Performance is evaluated across several math benchmarks, distinguishing between in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) datasets. The table shows the average accuracy across four independent runs for each method and benchmark, along with confidence intervals (found in the appendix).

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the natural language reward model. It includes the batch size, learning rate, representation dimension, contrastive lambda, number of epochs, preference ranking loss function, optimizer used, and the random seed.

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing two methods for constructing the goal state in a Q-value filtering process. The ‘Last Token’ method uses the representation of the last token in the sequence, while the ‘Random Token’ method randomly samples a token from the sequence. The table shows that the ‘Last Token’ method achieves slightly better accuracy and a higher proportion of correct sequences for both the GSM8k and MATH datasets. This suggests that the information contained in the last token of a sequence is more relevant for representing the overall goal than a randomly selected token.

This table compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores achieved by different methods for training reward models on mathematical reasoning tasks. It shows the performance across in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) datasets using three different goal-state sampling techniques: Single Goal State (SGS), Random Sampling (RS), and Average Goal State (AVG). The results help analyze how the choice of goal state representation impacts the performance of the reward model.

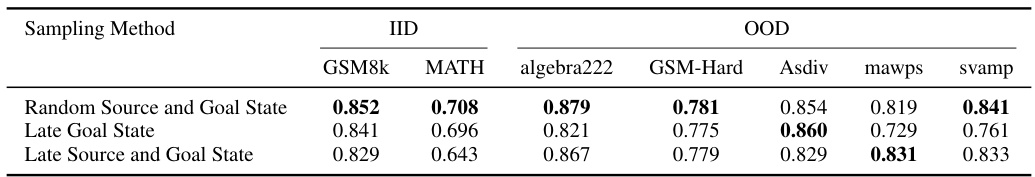

This table presents the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) scores achieved by three different methods of sampling source and goal states during the training of a reward model. The AUROC scores are given for both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) datasets across several math benchmarks. The three methods are: 1. Random Source and Goal State: Source and goal states are sampled randomly. 2. Late Goal State: Goal states are sampled from later tokens in the sequence. 3. Late Source and Goal State: Both source and goal states are sampled from later tokens in the sequence. The results indicate how the sampling strategy affects the model’s performance in identifying correct and incorrect solutions.

This table compares the performance of majority voting with Q-value filtering for mathematical reasoning. It shows accuracy, the proportion of correct classifications, the average percentage of generations filtered, and the average percentage of tokens saved by filtering for both GSM8k and MATH datasets.

This table compares the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) scores for different reward model projection strategies across several mathematical reasoning benchmarks. The AUROC score measures the ability of a reward model to correctly distinguish between correct and incorrect solutions. Two methods are compared: one using a linear layer for the reward head, and the other using a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) with ReLU activation. The table shows the AUROC scores for both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) benchmarks.

This table compares the correlation between Q-values and reward scores at different percentiles (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8) of model generations for two models: Q-Function (Linear) and Q-Function (MLP). The Q-Function (Linear) model shows a much higher correlation than the Q-Function (MLP) model across all percentiles. This suggests that using a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) for the reward projection, as in Q-Function (MLP), helps to reduce the correlation between the Q-values and reward scores, potentially mitigating the risk of the model gaming the reward during training.

This table compares the performance of three different methods for training a policy model: Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) with a standard preference ranking reward model, and PPO with a reward model trained using the proposed Q-Function method. The accuracy and 95% confidence intervals are reported for both in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) benchmark datasets. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed Q-Function method in improving the policy model’s performance, especially for OOD datasets.

This table presents the results of comparing majority voting with a Q-value filtering method to prune incorrect solutions. It shows the accuracy, proportion of correct solutions, average percentage of filtered generations, and average percentage of tokens saved for both methods on the GSM8k and MATH datasets. The statistical significance of the accuracy difference between the two approaches is noted.

Full paper#