↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Domain generalization (DG) aims to build models that perform well on unseen data distributions. Existing DG methods often struggle to consistently outperform simple baselines. This is a challenge because real-world data is rarely perfectly consistent across different environments.

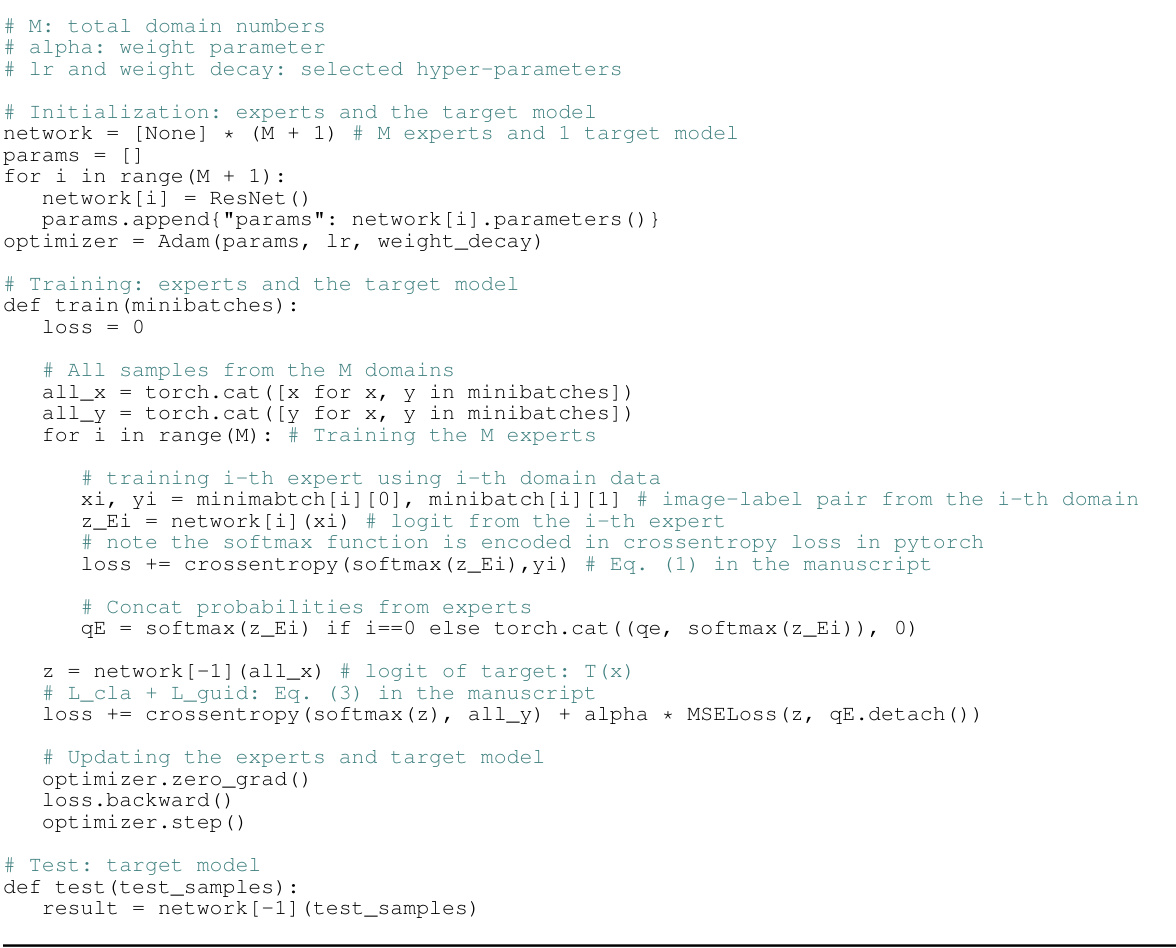

LFME tackles this issue by training multiple expert models, each specialized in a different source domain, to guide the training of a central target model. The guidance is implemented using a novel logit regularization term that enforces similarity between the target model’s logits and the experts’ probability distributions. Experiments show that LFME consistently improves upon existing methods, demonstrating the value of its approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a simple yet effective framework for domain generalization (DG), a crucial problem in machine learning. The proposed method, LFME, consistently improves baseline performance and achieves results comparable to state-of-the-art techniques. Its simplicity and effectiveness make it a valuable contribution to the field, opening new avenues for research in DG.

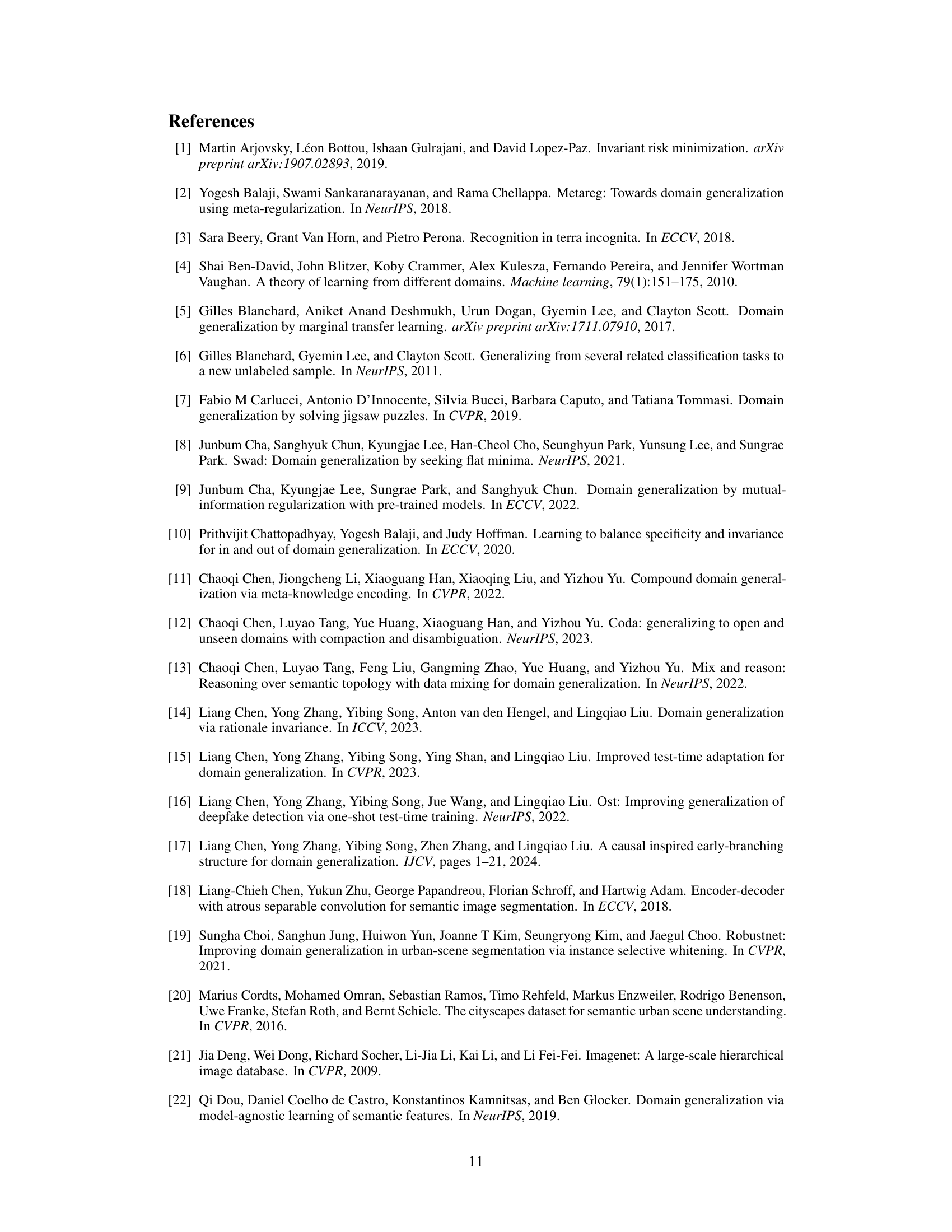

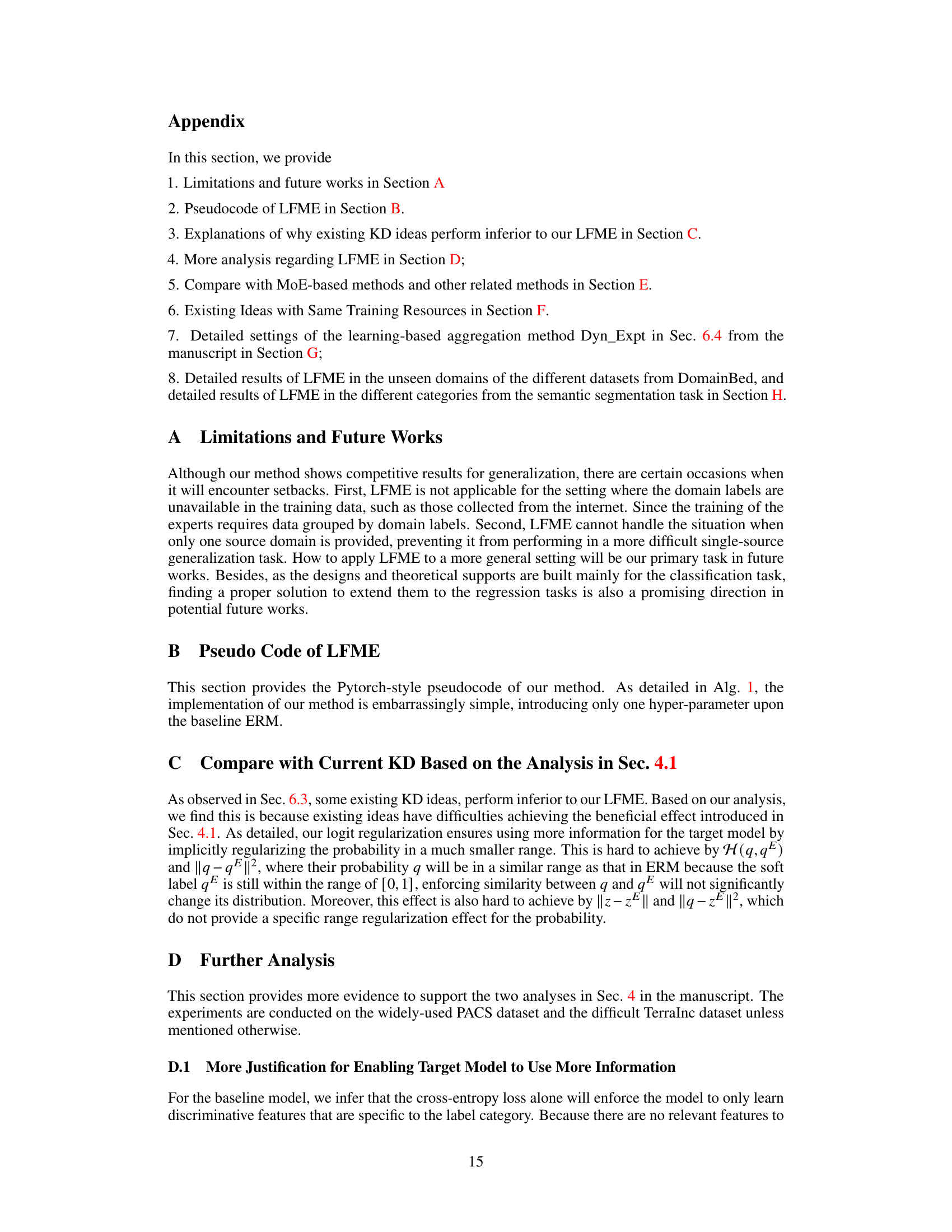

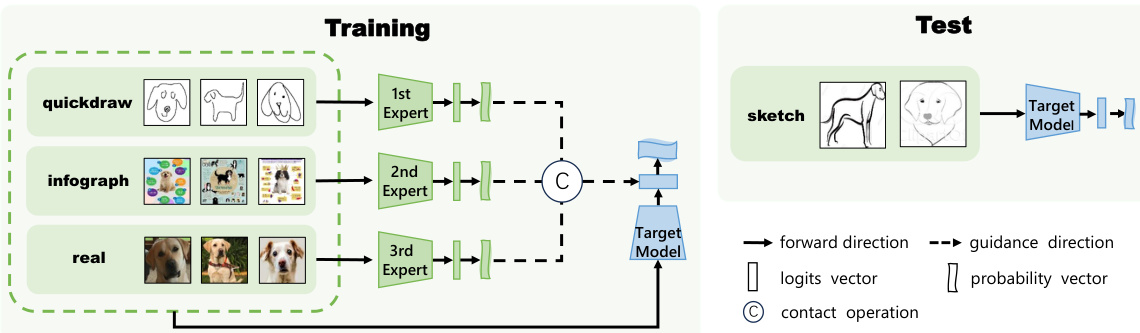

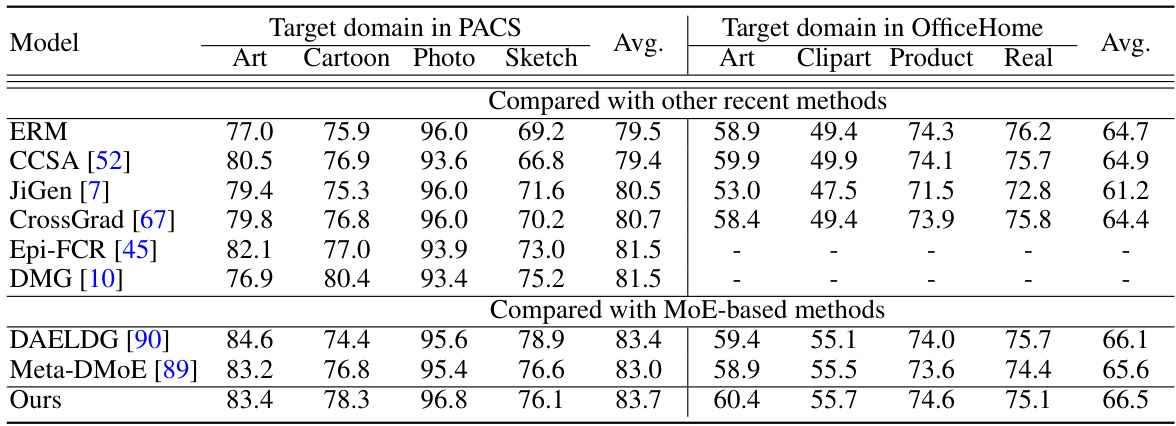

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the training and testing pipeline of the LFME framework. During training, multiple expert models are trained on different source domains, each specializing in a particular domain. Simultaneously, a target model is trained, receiving guidance from the expert models via a logit regularization term. This term enforces similarity between the logits of the target model and the probability outputs of the corresponding expert models. In the testing phase, only the target model is used to make predictions on unseen data. The figure highlights the flow of data and guidance between the expert models, the target model, and the test data.

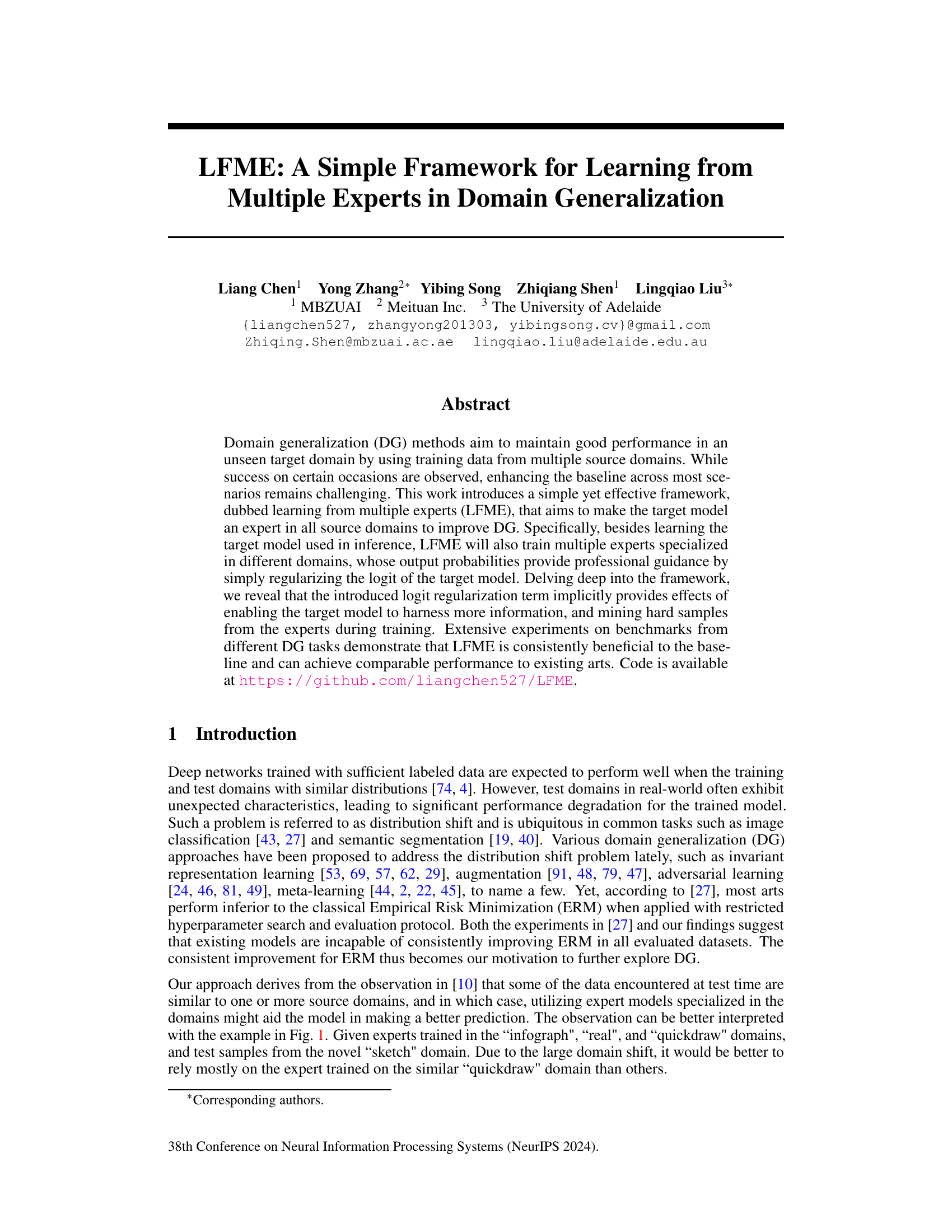

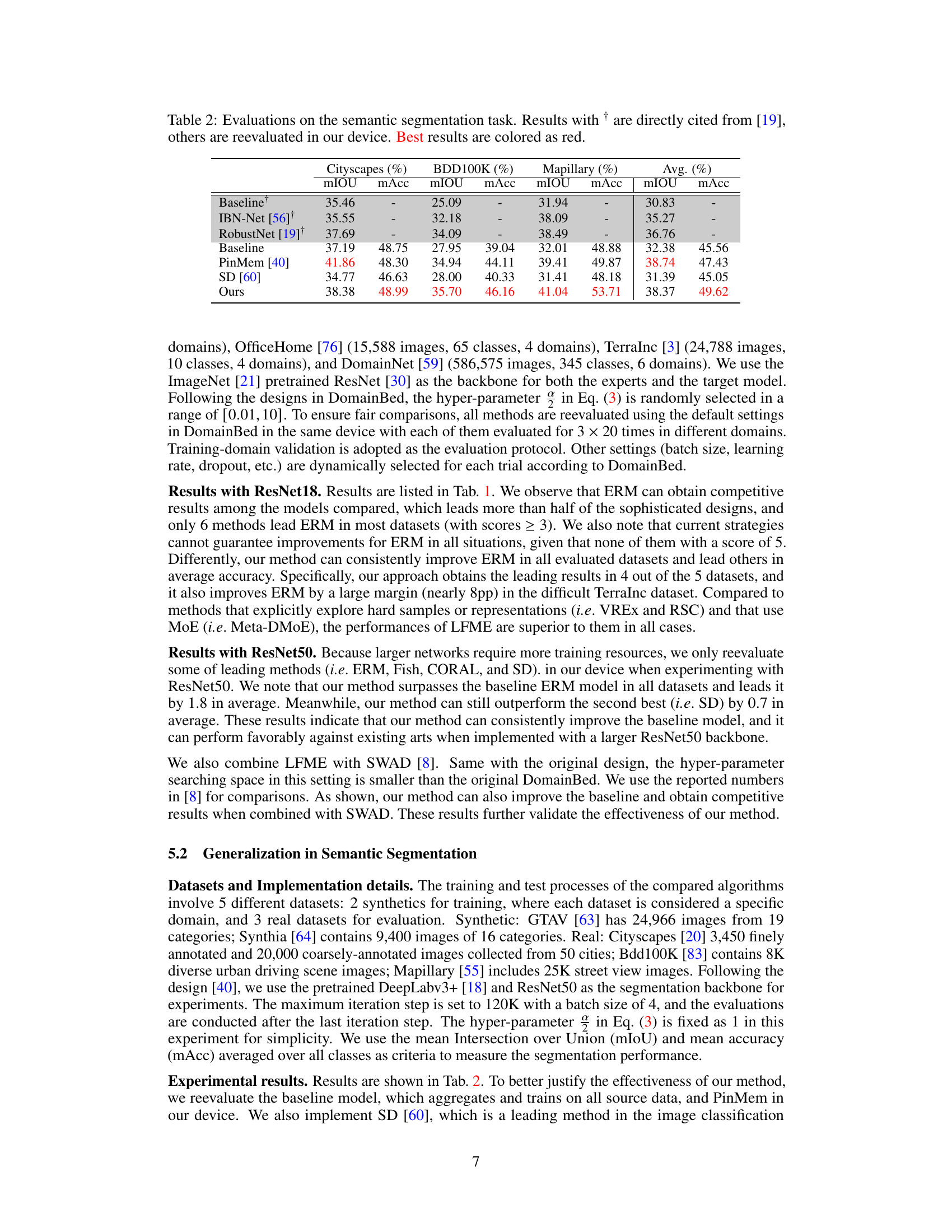

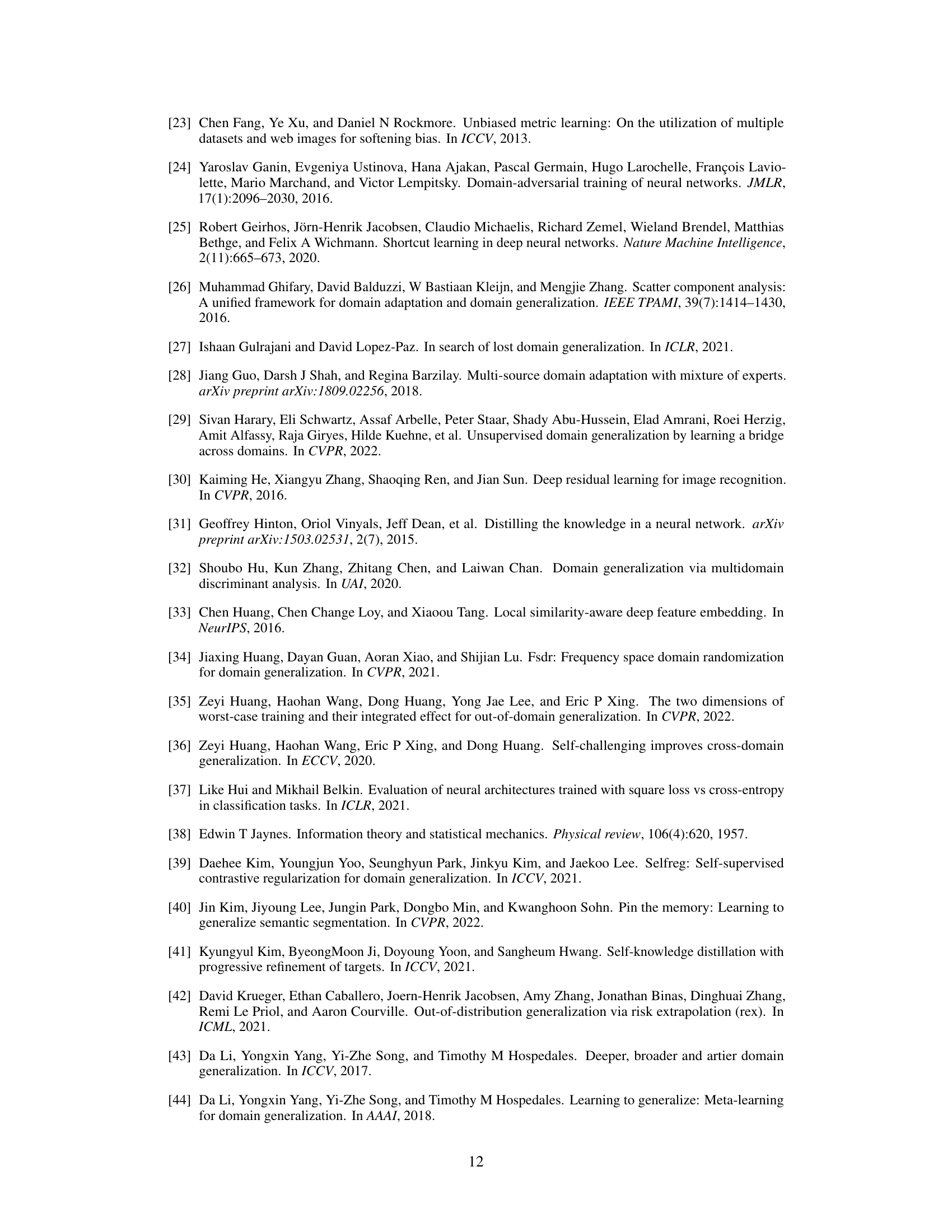

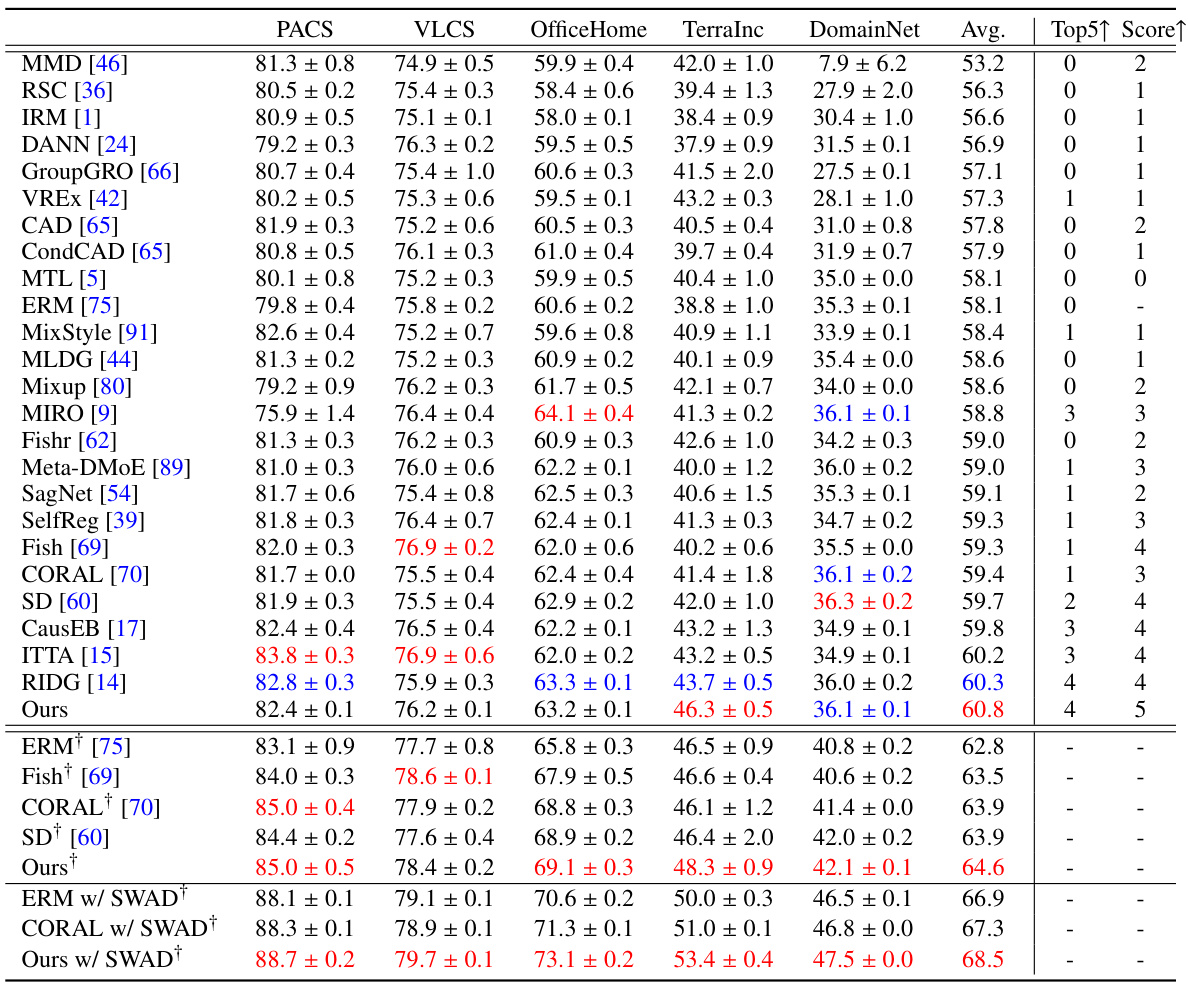

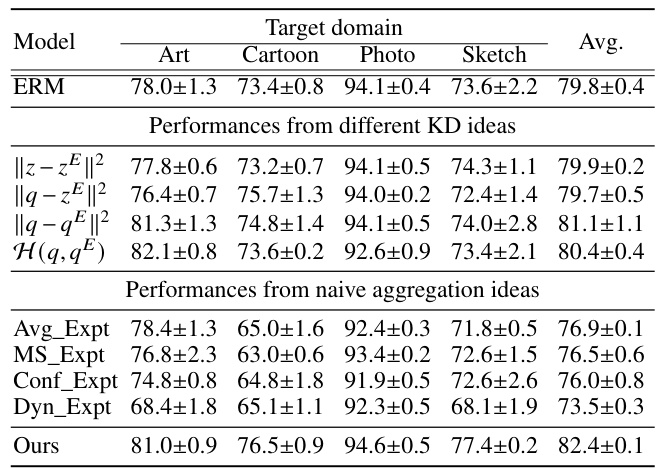

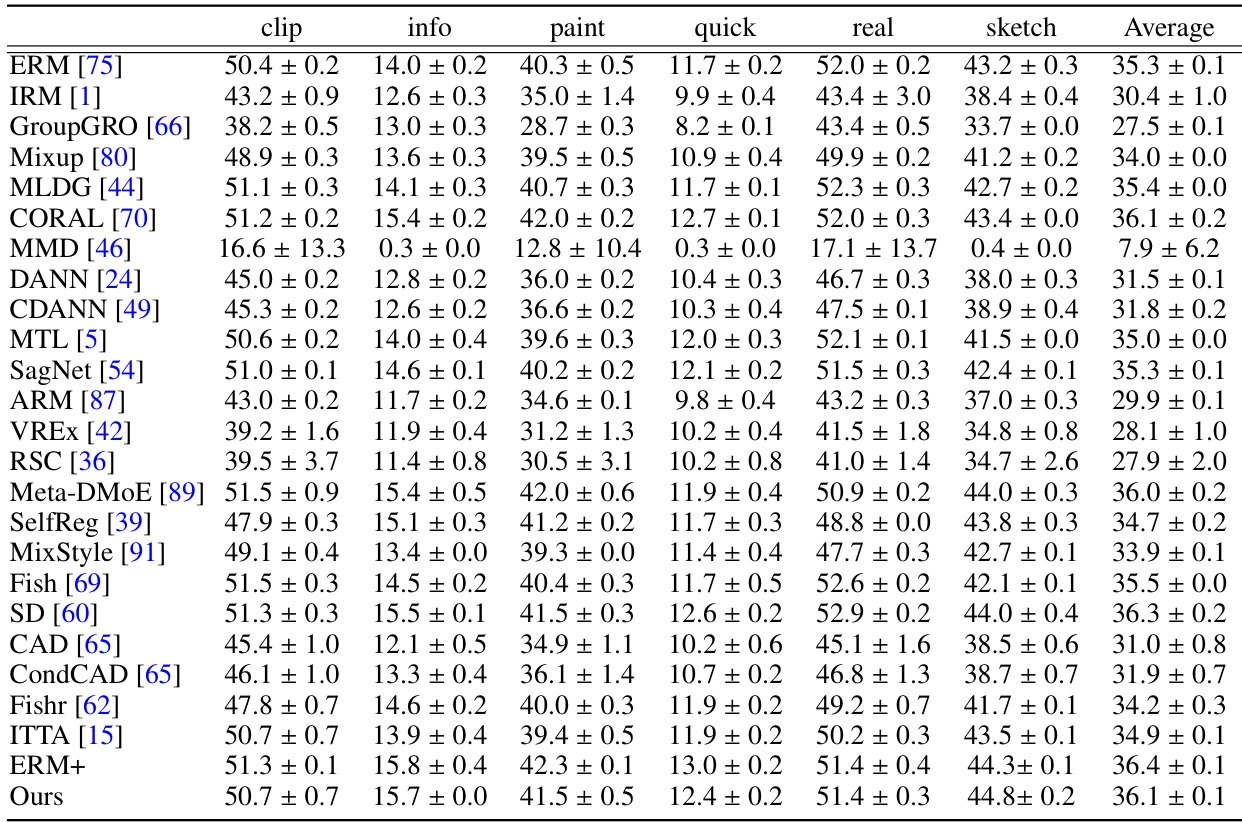

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments on the DomainBed benchmark using ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones. It compares various domain generalization methods (MMD, IRM, DANN, etc.) against the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. The table shows the average accuracy across five datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, DomainNet) for each method, along with the number of times each method achieved a top-5 performance and outperformed ERM. Results using SWAD (Stochastic Weight Averaging) are also included for comparison.

In-depth insights#

LFME Framework#

The LFME framework, designed for domain generalization, presents a novel approach to leverage multiple expert models for improved performance. Instead of complex aggregation techniques, LFME employs a simple logit regularization, guiding a universal target model toward expertise in all source domains. This implicit regularization enhances information utilization and facilitates hard sample mining from experts. The framework is computationally efficient at test time, using only the target model. Unlike traditional knowledge distillation, LFME’s regression-based approach using the expert logits rather than probabilities, offers a unique and effective method for knowledge transfer. Experimental results show consistent improvement over baselines, highlighting the effectiveness and simplicity of the LFME approach for domain generalization. The logit regularization is a key innovation, offering both improved information utilization and hard sample mining, ultimately leading to robust performance in unseen domains.

Logit Regularization#

Logit regularization, in the context of domain generalization, is a technique that refines the target model’s logits by leveraging the probability distributions produced by multiple domain-expert models. This approach implicitly encourages the target model to utilize more information during training, preventing overconfidence in simplistic patterns and promoting robustness. The regularization term acts as a form of knowledge distillation, guiding the target model toward a more balanced probability distribution, similar to soft label training, but acting on logits instead of probabilities. Furthermore, this method effectively facilitates hard sample mining, focusing the target model’s attention on challenging instances identified by the expert models. This leads to improved generalization performance, as the model is less likely to overfit the training data and better equipped to handle unseen data. By implicitly calibrating the target model’s probabilities without explicit parameter tuning, as seen in other techniques, logit regularization offers a simple yet effective way to boost domain generalization capabilities.

Expert Knowledge#

The concept of ‘Expert Knowledge’ in a domain generalization (DG) context centers on leveraging specialized models trained on individual source domains to enhance the performance of a general-purpose target model. These ’expert’ models offer valuable guidance, providing insights into specific domain characteristics that a single, universally trained model may miss. The integration of this knowledge can be achieved through techniques such as logit regularization, which implicitly refines the target model’s probability distribution and enables it to learn from the diverse expertise available. This approach allows for implicit hard sample mining, enhancing generalization by emphasizing less confidently predicted samples from the experts’ perspectives. A key advantage is the avoidance of explicit aggregation mechanisms during inference, maintaining efficiency and reducing computational demands. The efficacy of this approach highlights the potential of incorporating diverse, domain-specific information for more robust and generalized model performance in unseen target domains. Furthermore, it underscores the implicit advantages of transferring knowledge through logit adjustments over other knowledge distillation methods. Future research might explore more sophisticated methods for combining expert knowledge while optimizing the balance between specificity and generality.

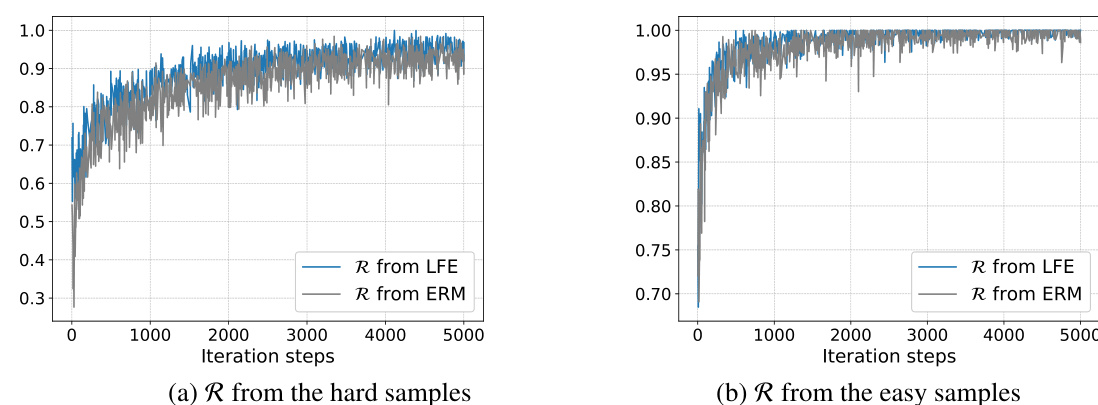

Hard Sample Mining#

Hard sample mining is a crucial technique in machine learning, especially in the context of domain generalization, where the goal is to train models that generalize well to unseen data distributions. The core idea is to focus on the most challenging samples during training, as these samples often contain the most discriminative information. This differs from traditional methods that treat all samples equally. In domain generalization, where data comes from multiple sources with varying distributions, hard samples are those that are least aligned with the model’s current understanding. Effectively identifying and utilizing these hard samples improves model robustness and generalization ability. The challenge lies in defining what constitutes a ‘hard sample’ and developing efficient algorithms to identify and weigh them appropriately. Different methods exist for hard sample mining, and each may have strengths and weaknesses regarding computational cost and effectiveness. Logit regularization, as used in LFME, implicitly performs hard sample mining. By focusing on samples where the expert models are less certain, the target model is indirectly guided toward addressing the most challenging aspects of the data distributions, leading to improved generalization performance. Therefore, hard sample mining is essential to domain generalization and should be considered a vital component of any robust DG approach.

Future of LFME#

The future of LFME (Learning from Multiple Experts) in domain generalization appears promising, given its strong performance and simplicity. Extending LFME to handle scenarios with limited or no domain labels during training is crucial, as it would broaden applicability to real-world situations where such information might be scarce or unavailable. Further research should investigate more sophisticated expert aggregation mechanisms beyond simple logit regularization to potentially improve performance and efficiency, especially for a larger number of source domains. Exploring the theoretical underpinnings of LFME’s effectiveness more deeply could lead to more principled design choices and improved generalization capabilities. Finally, empirical evaluations across a wider range of domain generalization tasks and benchmarks will be important in validating LFME’s robustness and identifying potential limitations.

More visual insights#

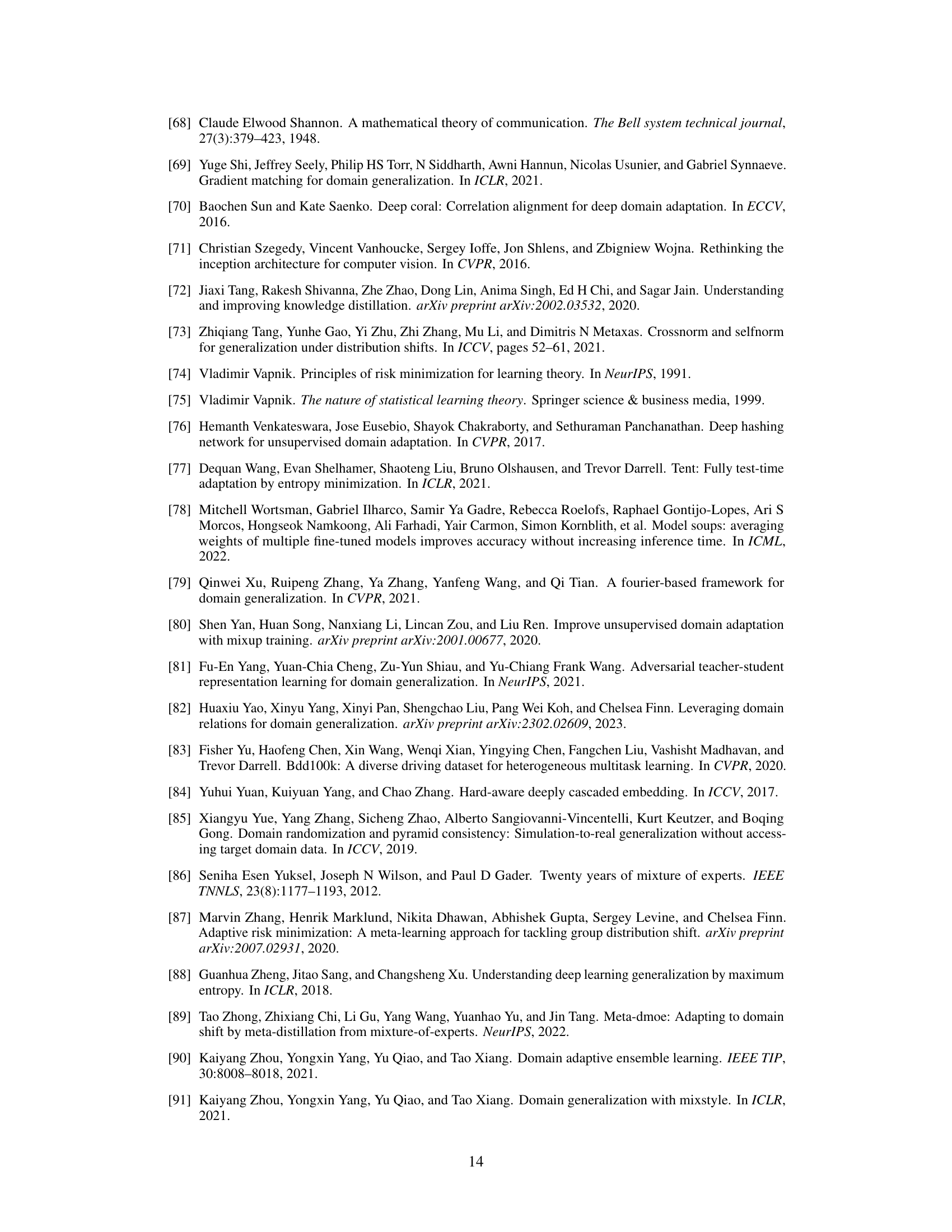

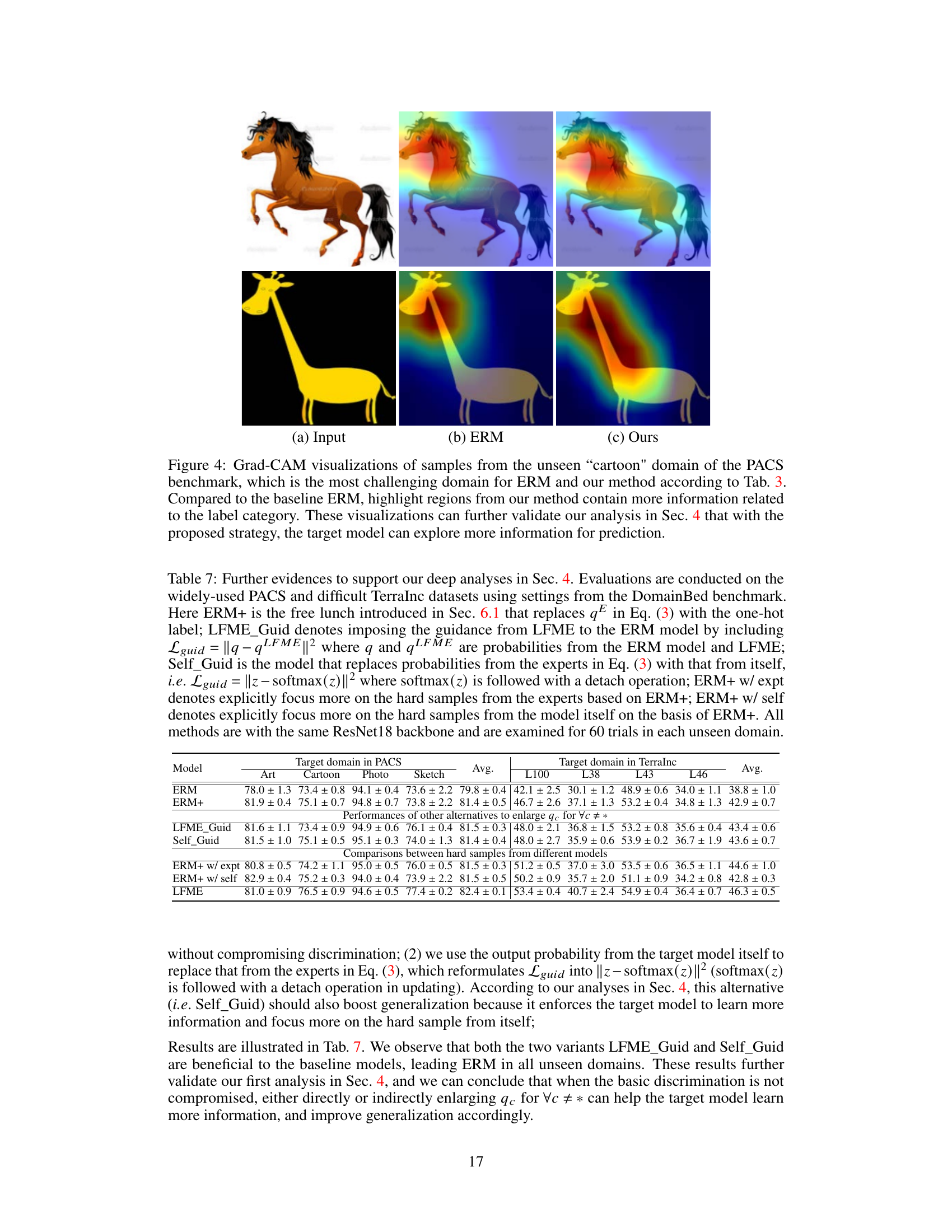

More on figures

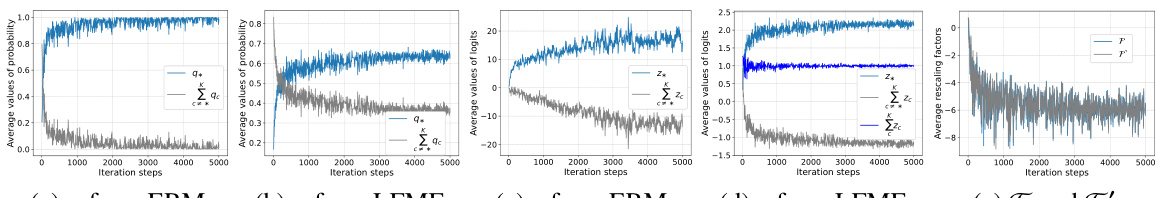

The figure shows the average values of probabilities, logits and rescaling factors obtained from ERM and LFME models trained on three source domains from PACS dataset. The plots visualize the changes in probability distributions (q), logits (z), and rescaling factors (F and F’) over training iterations. It illustrates how LFME regularizes logits and results in smoother probability distributions compared to ERM. This difference is further analyzed to explain why LFME improves Domain Generalization.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of semantic segmentation results from different methods on real-world images. The results from the baseline, SD, PinMem, and the proposed LFME method are shown alongside the ground truth. The figure highlights how the LFME method produces more accurate segmentations, especially for challenging objects such as those partially obscured or with unusual shapes or lighting conditions.

This figure illustrates the training and testing pipeline of the LFME framework. During training, multiple expert models are trained simultaneously, each specializing in a different source domain. The target model, which will be used for inference, also trains concurrently. The experts guide the target model by regularizing its logits to be similar to the probability distribution from the corresponding expert. During testing, only the target model is used, resulting in a efficient, single model deployment.

This figure shows qualitative comparisons of the proposed LFME method against baseline and other state-of-the-art methods on the semantic segmentation task. It highlights the superior performance of LFME in handling challenging scenarios with significant domain shifts, such as variations in object shapes, presence of shadows, and unusual background contexts. The results visually demonstrate LFME’s ability to generate more accurate and comprehensive segmentations compared to other methods.

The figure shows the changes in probabilities (q), logits (z), and rescaling factors (F, F’) during the training process of both ERM and LFME models. The models were trained on three source domains from the PACS dataset using identical settings. The plots illustrate how LFME, through its logit regularization, leads to a smoother probability distribution and a more balanced logit range compared to the ERM model. These differences are linked to the ability of LFME to incorporate more information and focus on more challenging samples during training, ultimately improving generalization performance.

This figure illustrates the training and testing pipeline of the proposed LFME framework. During training, multiple experts are trained simultaneously with the target model. Each expert specializes in a different source domain. The experts guide the target model by regularizing its logits using the experts’ output probabilities, ensuring the target model learns from the expertise of each domain. During testing, only the target model is used for inference.

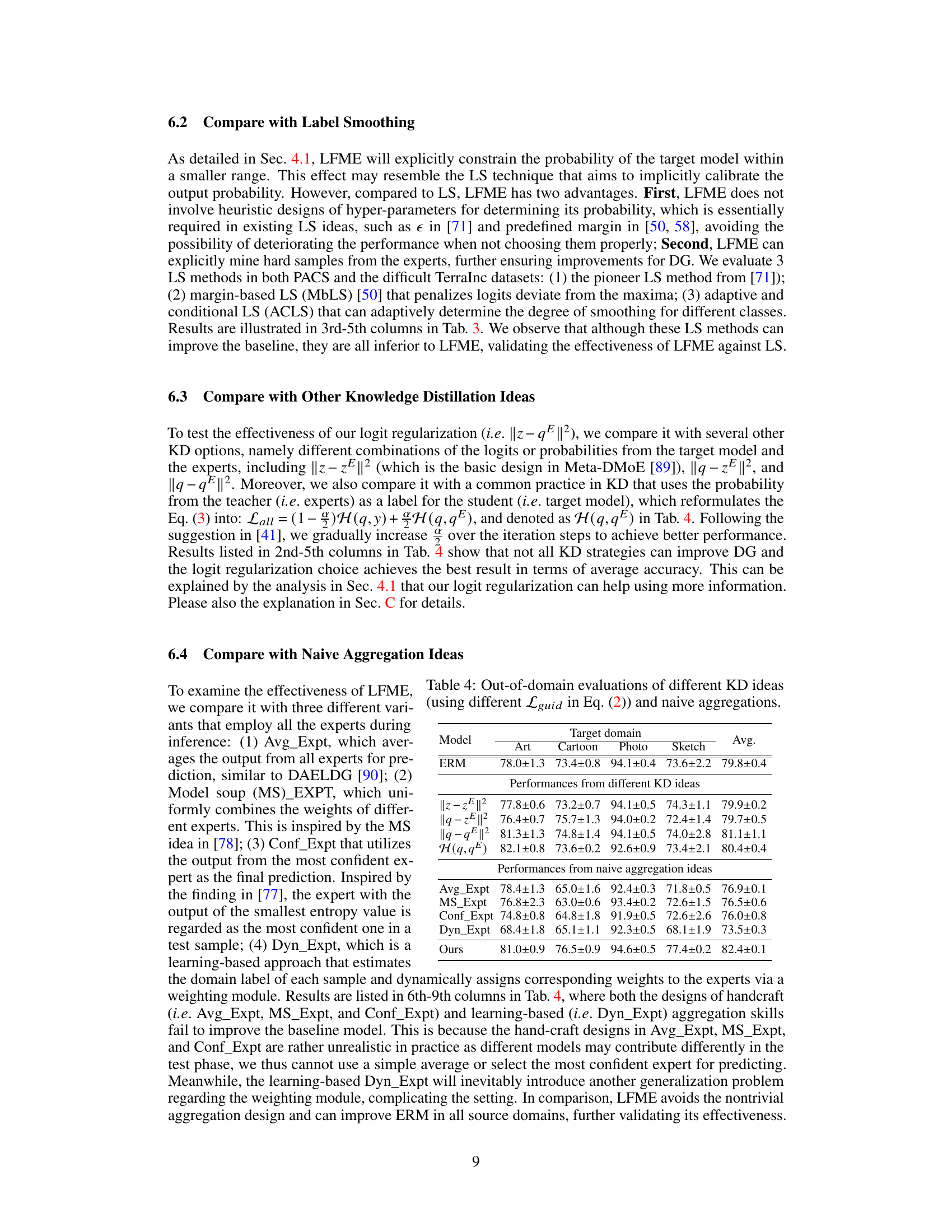

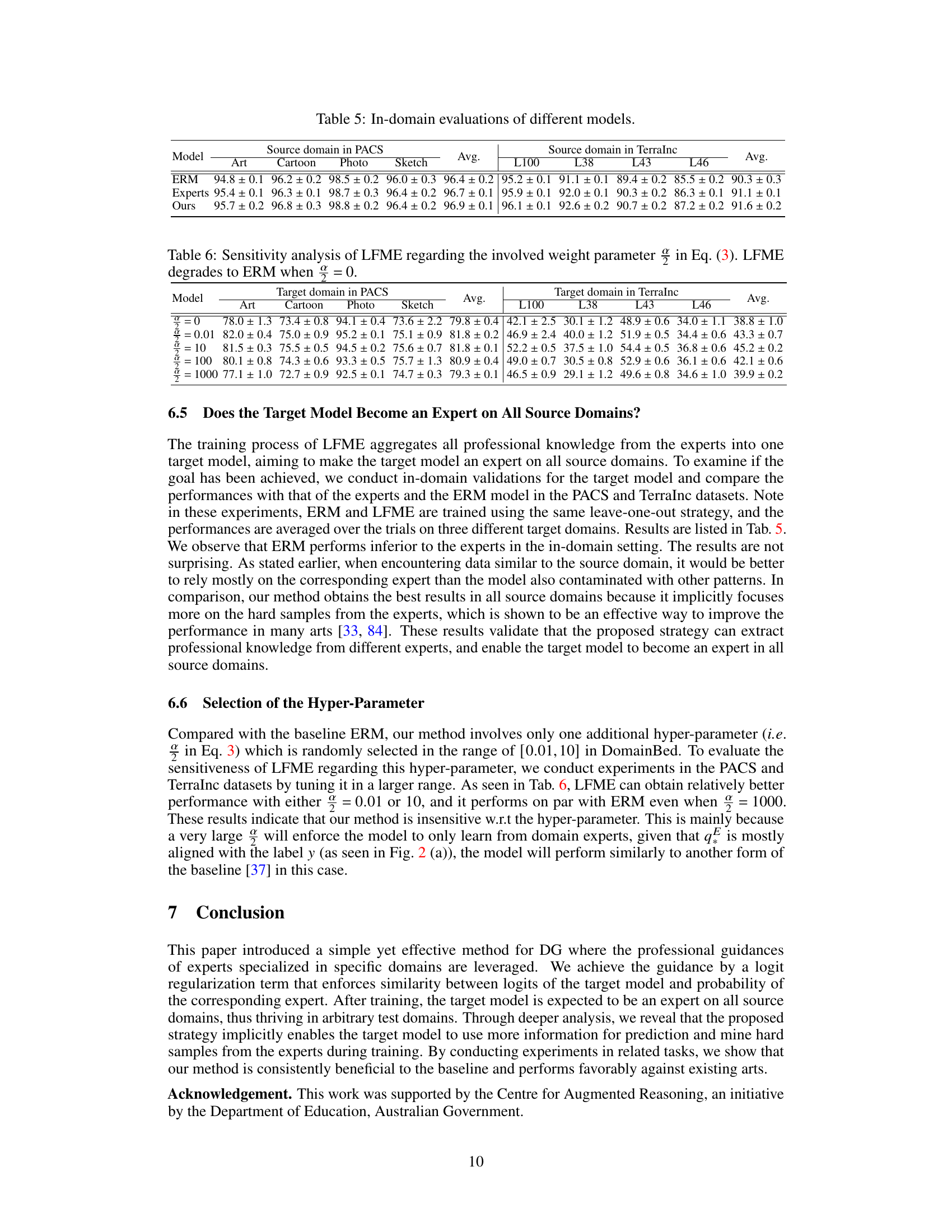

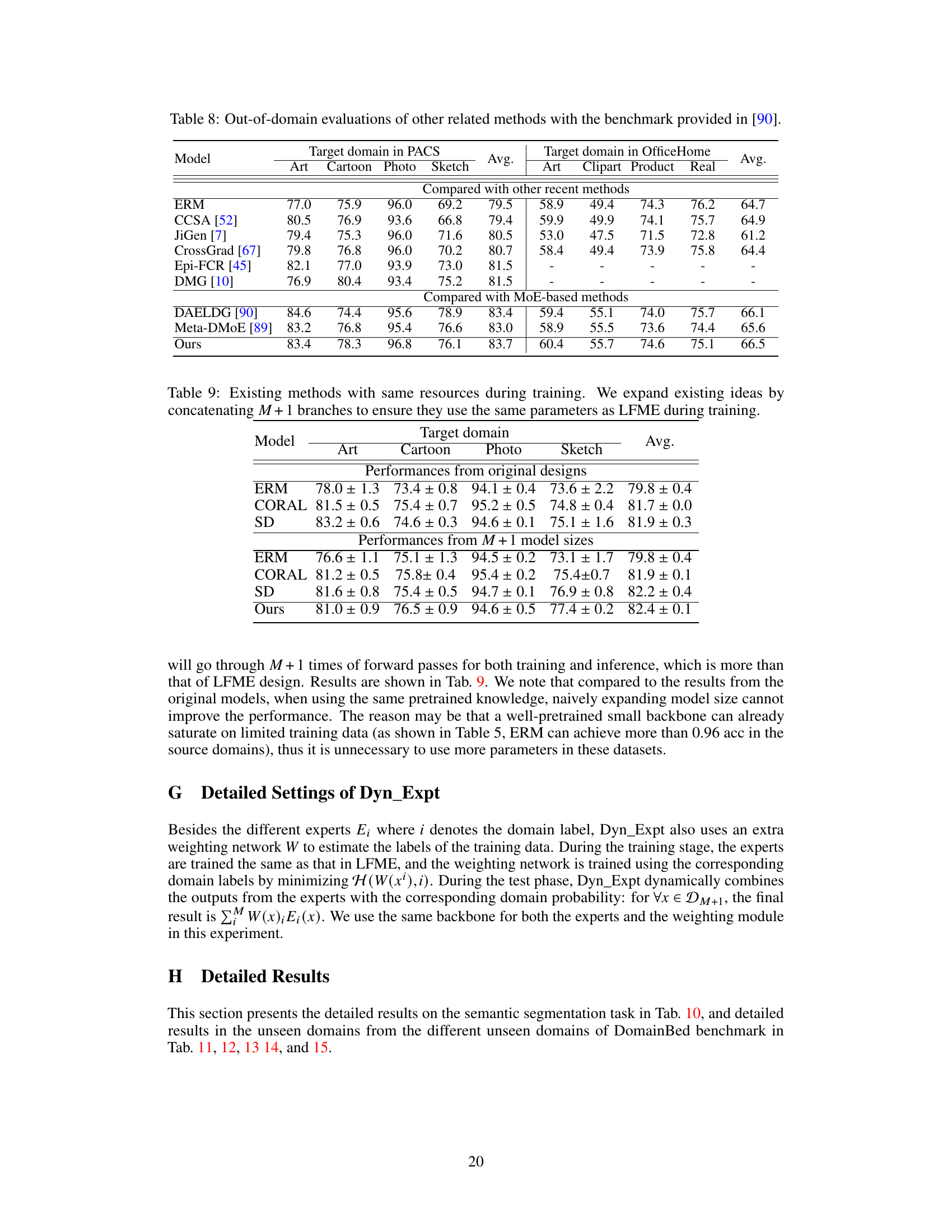

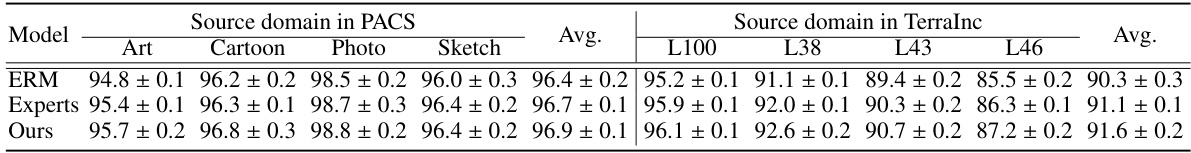

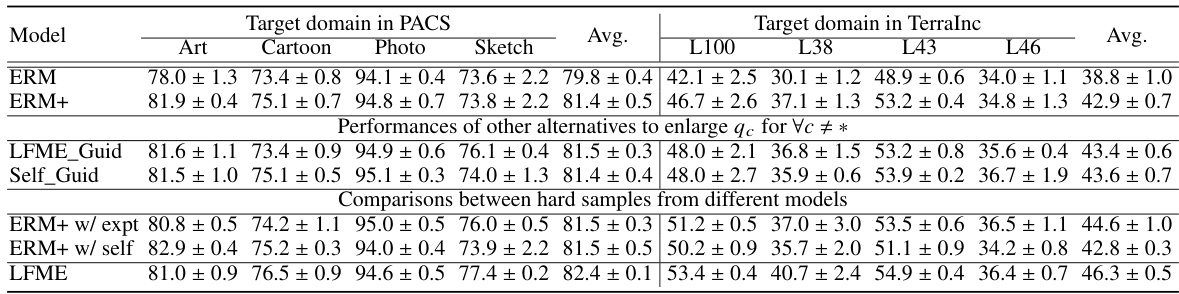

More on tables

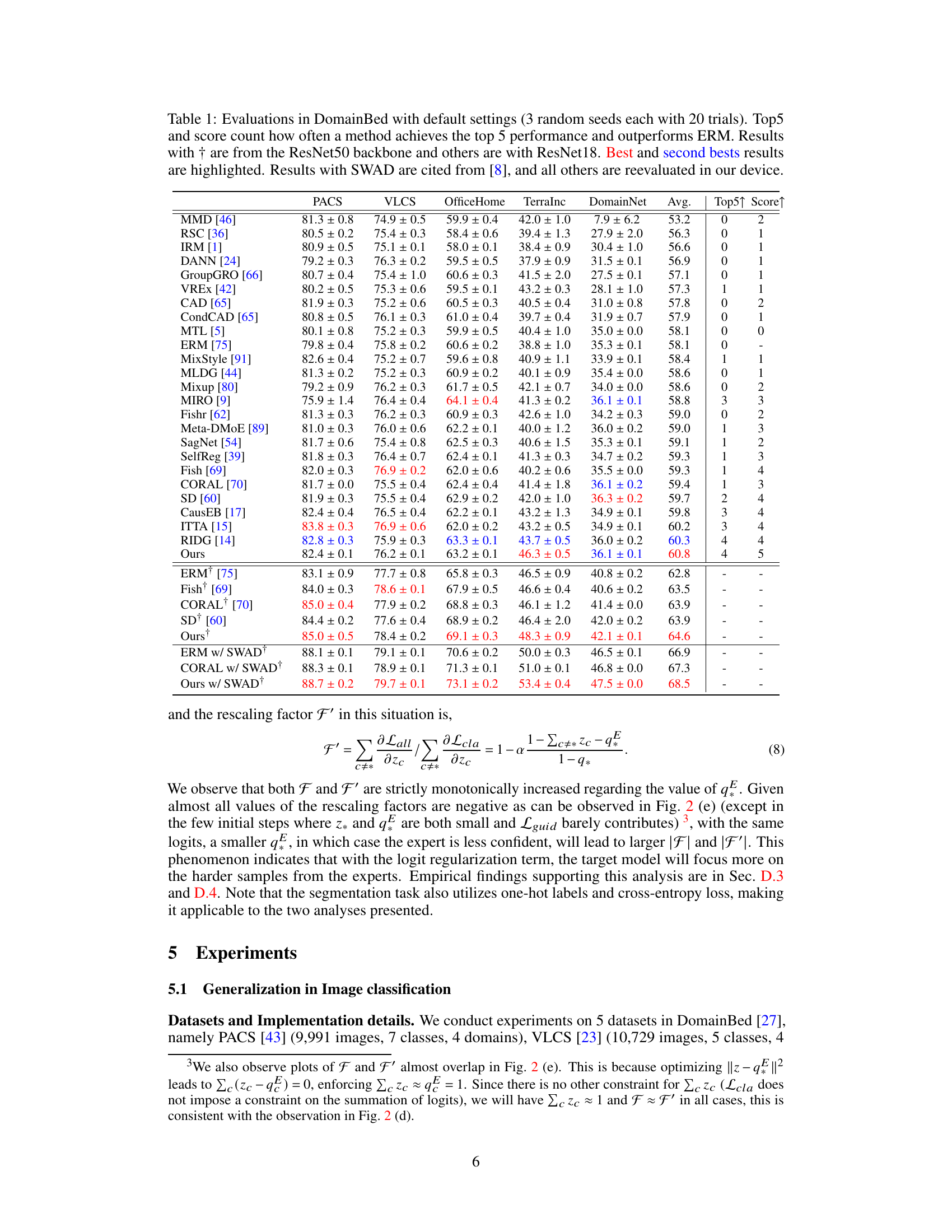

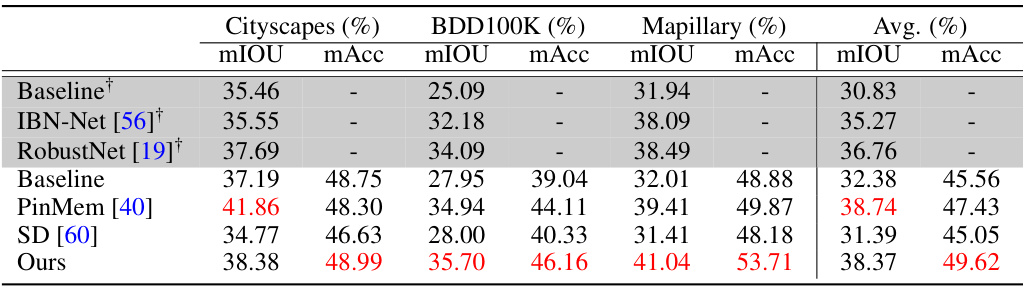

This table presents the results of semantic segmentation experiments. It compares the performance of different methods (Baseline, IBN-Net, RobustNet, PinMem, SD, and the proposed method, Ours) on three datasets: Cityscapes, BDD100K, and Mapillary. The metrics used are mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) and mean accuracy (mAcc). Results marked with † were taken directly from source [19], while others were re-evaluated on the authors’ device. The best results for each metric and dataset are highlighted in red.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments conducted using the DomainBed benchmark. It compares the performance of LFME against several state-of-the-art domain generalization methods across five different datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, and DomainNet). The table shows average accuracy, the number of times each method ranked among the top 5 performing methods, and whether it outperformed the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. Different backbone networks (ResNet18 and ResNet50) were used for some methods.

This table presents the results of several domain generalization (DG) methods on the DomainBed benchmark. The table compares the average accuracy of various methods across five different datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, DomainNet), using ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones. The ‘Top5’ and ‘Score’ columns indicate how frequently a given method achieved a top-five ranking and outperformed the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline, respectively. Results using SWAD (Stochastic Weight Averaging) are referenced from prior work.

This table presents the results of the image classification task using the DomainBed benchmark with default settings. The results of several domain generalization methods are compared with the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. The table shows the average accuracy (± standard deviation) across five datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, and DomainNet) for each method using ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones (indicated by †). The ‘Top5’ column indicates how many times a method achieved top-5 performance across the five datasets, and the ‘Score’ column shows how many times each method outperformed the ERM baseline.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments conducted using the DomainBed benchmark. It compares the performance of the proposed LFME method against various state-of-the-art domain generalization techniques across five different datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, DomainNet). The table includes metrics such as average accuracy across all datasets, how often each method ranks within the top 5, and how often it outperforms the standard Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. Different backbone networks (ResNet18 and ResNet50) are used, and some results incorporating the SWAD optimizer are also reported for comparison.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments using the DomainBed benchmark. It compares the performance of LFME against various other domain generalization methods on four datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, and TerraIncog). The table shows average accuracy, how often a method ranks among the top 5, and how often it outperforms the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. Results are shown for both ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones, and some results using the SWAD optimizer are included for comparison.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments conducted using the DomainBed benchmark. It compares the performance of various domain generalization methods against the baseline Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) method across five different datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, and DomainNet). The table shows the average accuracy and indicates how frequently each method achieved top-5 performance and outperformed ERM. ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones were used in some experiments, and the results using SWAD (a specific optimization technique) are also included.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments on the DomainBed benchmark using different methods. The table shows the average accuracy of each method across five datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, and DomainNet) with three random seeds and 20 trials each. The ‘Top5’ column indicates how many times a method achieved top-5 accuracy, and ‘Score↑’ counts the instances where a method outperformed the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. Results are separated for ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones, with the latter indicated by †. SWAD results are cited from a reference paper, while other results were reevaluated on the author’s device.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments on the DomainBed benchmark using ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones. It compares the performance of the proposed LFME method against several other state-of-the-art domain generalization methods across five different datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, DomainNet). The table shows the average accuracy, the frequency of achieving top 5 performance, and the frequency of outperforming the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. The use of different backbones (ResNet18 vs. ResNet50) and the inclusion of SWAD (Stochastic Weight Averaging) are noted.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments conducted using the DomainBed benchmark. It compares the performance of various domain generalization methods against the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. The table shows the average accuracy across multiple trials for each method on four different datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraInc). It also indicates how frequently each method achieved top 5 performance and outperformed ERM. The results are categorized based on whether they used ResNet18 or ResNet50 as their backbone model and whether they included the SWAD optimization technique.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments on the DomainBed benchmark using different methods, including the proposed LFME approach. It compares the average performance across five datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, DomainNet) using ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones. The ‘Top5’ and ‘Score’ columns indicate how often each method ranks among the top five performers and surpasses the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline, respectively. Results are averaged over three random seeds, each with twenty trials, providing a comprehensive comparison of various domain generalization techniques.

This table presents the results of several domain generalization (DG) methods on the DomainBed benchmark. It compares the performance of various methods against the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline across five datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, and DomainNet). The table shows average accuracy, the frequency of achieving top-5 performance, and how often each method outperforms ERM. Results are presented for both ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones, with the latter indicated by a † symbol.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments using different methods on the DomainBed benchmark. The table shows the average accuracy (± standard deviation) of each method across five datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, DomainNet), using both ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones. The ‘Top5’ and ‘Score’ columns indicate how frequently a method achieved a top-five performance and outperformed the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline, respectively. Results using the SWAP algorithm are taken from prior work [8], and the remaining results were reproduced by the authors.

This table presents the results of domain generalization experiments on the DomainBed benchmark using ResNet18 and ResNet50 backbones. It compares the performance of LFME against various other domain generalization methods across five datasets (PACS, VLCS, OfficeHome, TerraIncognita, DomainNet). The table shows the average accuracy and indicates how often a method achieved top-5 performance and outperformed the Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM) baseline. The use of ResNet50 (marked with †) allows for a comparison with different backbone architectures.

Full paper#