↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many small devices lack the processing power to run modern, large neural networks efficiently, especially for real-time tasks. This poses a significant challenge to deploying state-of-the-art AI solutions in resource-constrained applications, such as smartwatches and AR glasses. Existing compression techniques often prove insufficient for achieving the necessary performance.

To overcome this issue, this research proposes a novel method called Scattered Online Inference (SOI). SOI reduces computational complexity by utilizing the continuity and seasonality of time-series data, allowing for efficient prediction of the model’s future states. This approach also incorporates data compression for further efficiency. Experiments demonstrate SOI’s effectiveness in speech separation and acoustic scene classification, achieving significant computational savings while preserving model accuracy. The method offers a flexible trade-off between computational cost and model performance, making it suitable for a variety of resource-constrained applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the critical need for efficient neural network inference on resource-constrained devices. By introducing a novel method called Scattered Online Inference (SOI), it significantly reduces the computational complexity of ANNs while maintaining acceptable performance. This has significant implications for deploying advanced AI models on low-power devices and expands the range of applications for AI, particularly in real-time systems. The research opens up exciting new avenues for optimizing inference efficiency across a variety of architectures and applications, particularly for time-sensitive applications such as speech separation and scene classification, showing potential in energy-efficient AI.

Visual Insights#

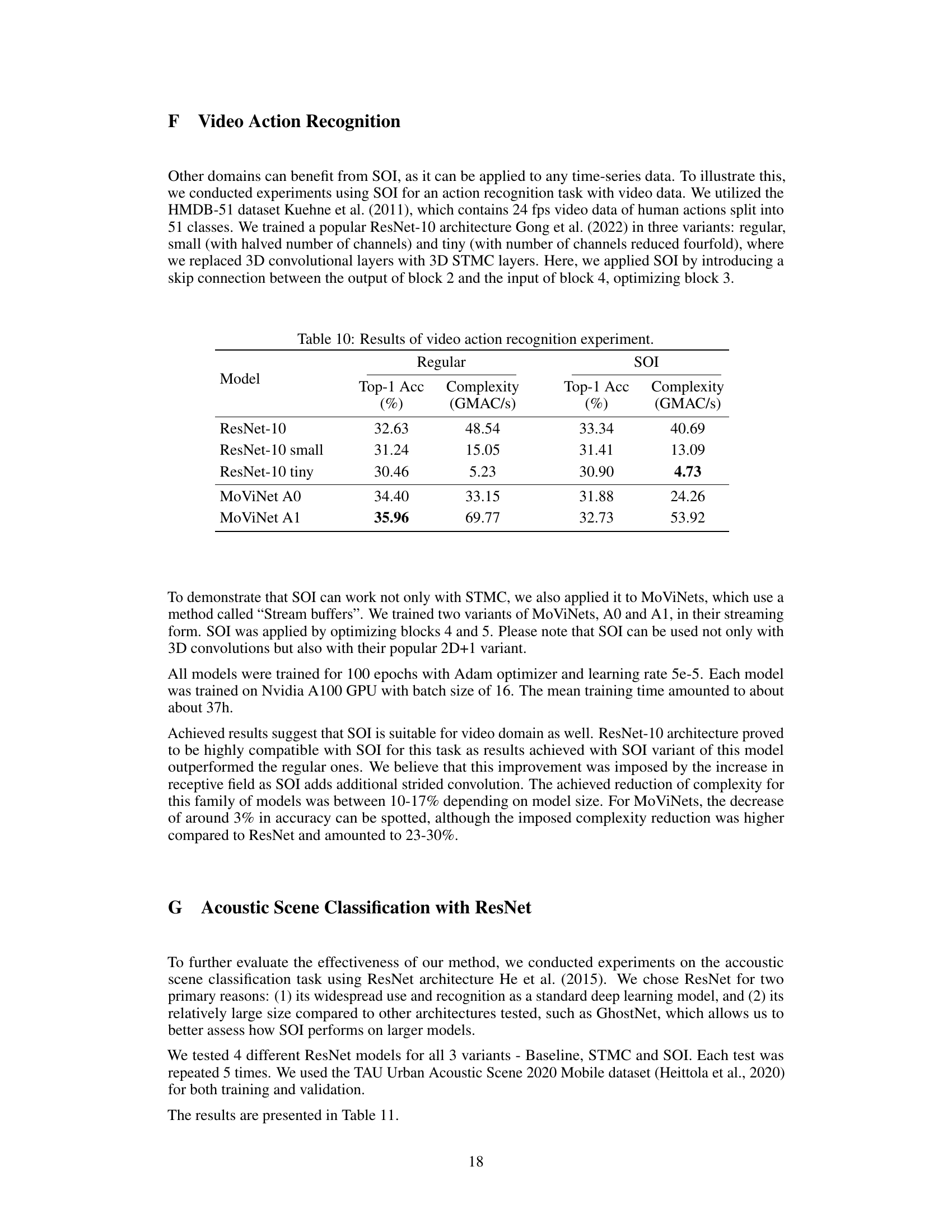

This figure illustrates five different convolutional operation patterns used in the Scattered Online Inference (SOI) method. It visually represents how SOI modifies standard and strided convolutions by incorporating cloning and shifting techniques to reduce computational complexity. Each sub-figure shows a different approach for optimizing convolutional operations within the SOI framework, leveraging data compression and extrapolation strategies in the time domain to skip redundant computations.

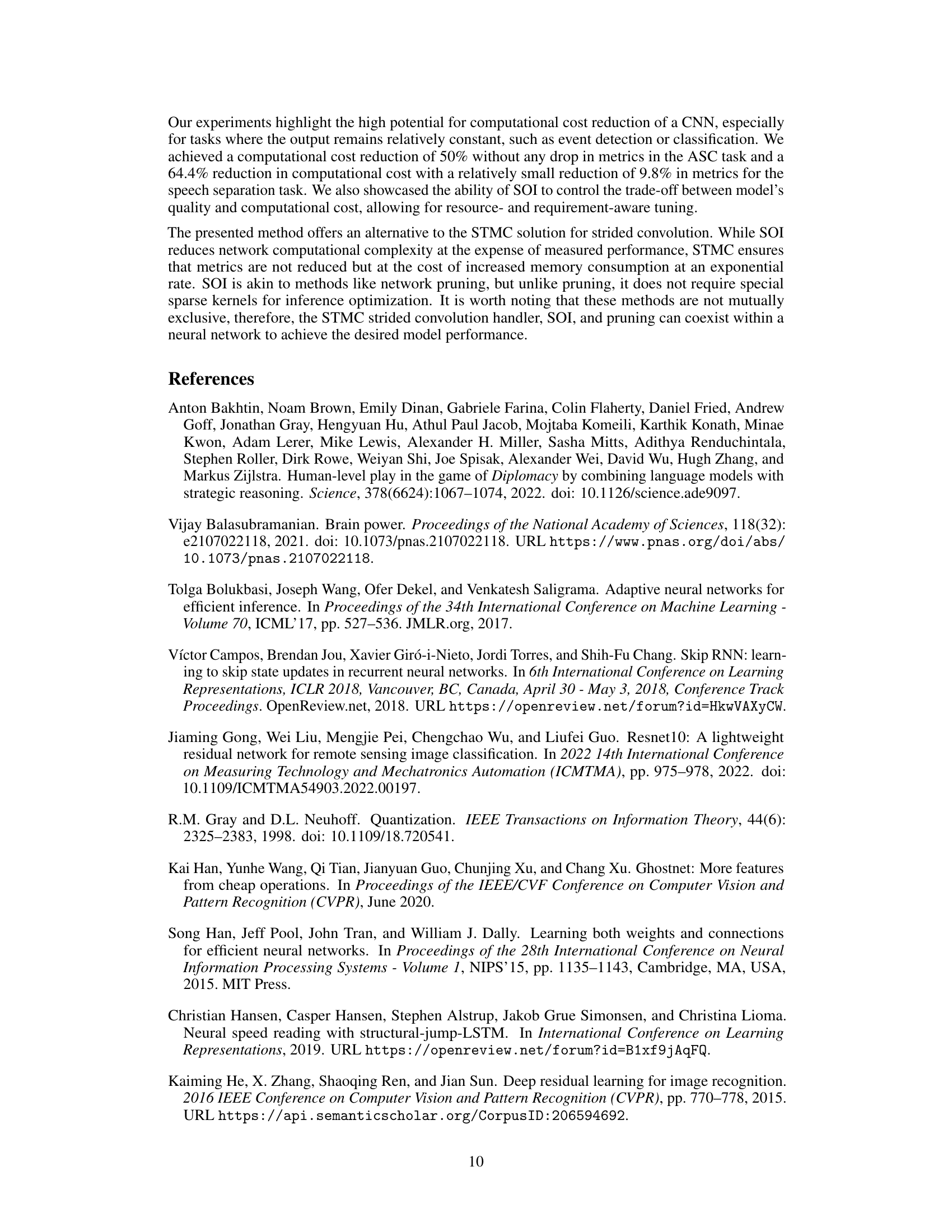

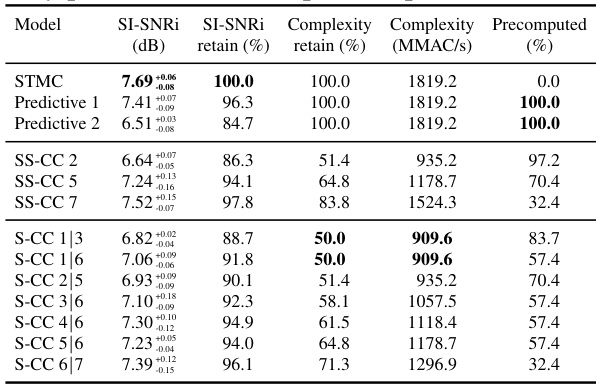

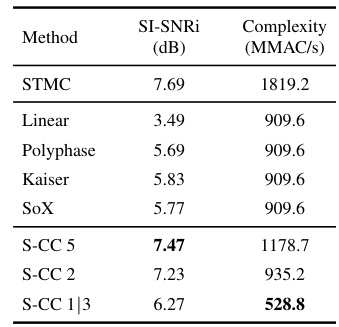

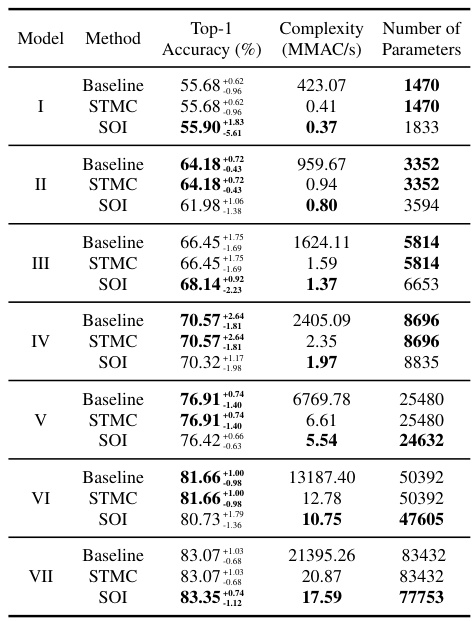

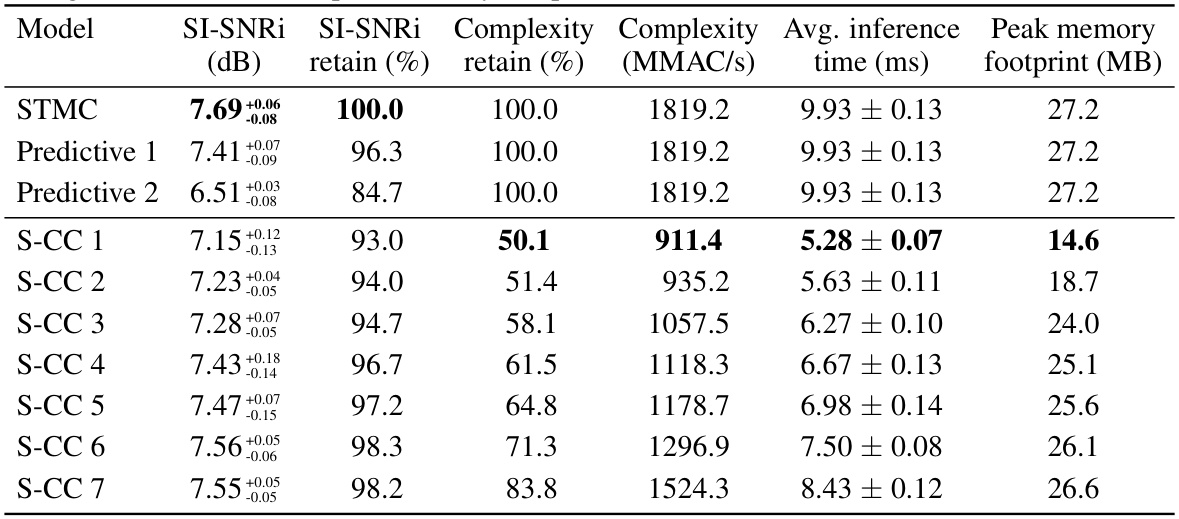

This table presents a subset of the results obtained from experiments using partially predictive SOI (Scattered Online Inference) for a speech separation task. It shows the performance metrics (SI-SNRi in dB) achieved by several different model variations, each differing in the placement and number of S-CC (Strided-Cloned Convolution) layers. The table also indicates the percentage of retained SI-SNRi and complexity (MMAC/s) relative to a baseline model (STMC). This allows for a comparison of the trade-off between model accuracy and computational efficiency achieved by the various SOI configurations.

In-depth insights#

SOI: Efficiency Gains#

The heading ‘SOI: Efficiency Gains’ suggests an examination of the computational efficiency improvements achieved by the Scattered Online Inference (SOI) method. A thorough analysis would detail how SOI reduces computational complexity compared to standard methods. Key aspects to cover include the mechanisms by which SOI achieves efficiency (e.g., partial state estimation, data compression, extrapolation). Quantifiable metrics, such as reductions in FLOPS, memory usage, and inference time, should be presented and compared against baselines. The discussion should also consider the trade-off between efficiency and accuracy, exploring any performance degradation resulting from SOI’s approximations. Finally, the analysis should assess the generalizability of SOI’s efficiency gains across different network architectures, datasets, and application domains, highlighting both its strengths and limitations.

Partial State Inference#

Partial state inference is a novel method for optimizing neural network computations by strategically skipping full model recalculations during inference. This approach leverages the inherent continuity and seasonality often found in time-series data and model predictions. By employing compression techniques, partial states of the network’s inner workings are generated, allowing the model to extrapolate and bypass unnecessary computations. This results in significant speed improvements, particularly beneficial for real-time applications on resource-constrained devices. Although this method is particularly effective for certain architectures and data types, it requires careful consideration of potential cumulative errors over longer time sequences. Furthermore, the optimal balance between computational cost reduction and model accuracy necessitates careful tuning and selection of appropriate extrapolation or interpolation methods. Despite these limitations, partial state inference offers a powerful mechanism for enhancing efficiency and real-time performance in various neural network applications.

U-Net Architecture#

The U-Net architecture is a powerful convolutional neural network (CNN) designed for biomedical image segmentation. Its characteristic U-shape arises from its symmetrical encoder-decoder structure. The encoder progressively downsamples the input image using convolutional and max pooling layers, capturing increasingly abstract features. The decoder then upsamples the feature maps from the encoder using transposed convolutions, gradually restoring spatial resolution. Crucially, skip connections link corresponding layers in the encoder and decoder, concatenating encoder features with the upsampled decoder outputs. This allows the decoder to recover fine-grained spatial details lost during downsampling, leading to highly accurate and detailed segmentations. The architecture’s effectiveness stems from its ability to integrate both context and detail, making it particularly well-suited for tasks with limited training data, a common challenge in medical imaging. Further modifications and adaptations of U-Net, such as 3D U-Net for volumetric data, demonstrate its adaptability to a range of segmentation problems.

SOI Limitations#

The heading ‘SOI Limitations’ invites a critical examination of the Scattered Online Inference method’s shortcomings. A thoughtful analysis would reveal that while SOI offers significant computational advantages by strategically skipping calculations and leveraging data continuity, several limitations exist. Accuracy may suffer in applications demanding the highest precision, as SOI’s prediction mechanisms introduce potential cumulative errors. The method’s flexibility in balancing computational cost and accuracy, while beneficial, also necessitates careful tuning and validation, potentially increasing the resource intensity of training. Temporal dependencies within data significantly influence the method’s success, suggesting a limitation in its generalizability to datasets where such dependencies are not prevalent. Finally, SOI’s demonstrated efficacy is presently focused on specific network architectures; its effectiveness across a broader range of models remains to be thoroughly explored. Addressing these limitations is crucial for establishing SOI’s overall utility and robustness.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on Scattered Online Inference (SOI) for neural networks could focus on several key areas. Extending SOI’s applicability to a wider range of network architectures beyond the tested CNNs and U-Nets is crucial. Investigating the impact of different data compression techniques and extrapolation methods, beyond the basic methods explored here, would improve accuracy and efficiency. A deeper exploration of the trade-offs between accuracy and computational savings across various applications and data types is also warranted. Further work should examine the cumulative error accumulation over time in long sequences, potentially mitigating these errors with advanced error correction mechanisms. Finally, developing more sophisticated methods for balancing computational cost and model performance would make SOI more practical for resource-constrained settings, such as edge devices. Integrating SOI with other model optimization techniques, like pruning and quantization, could lead to significant improvements in overall efficiency and performance. Thorough benchmarking across a broader set of tasks would further validate SOI’s effectiveness and identify areas for optimization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

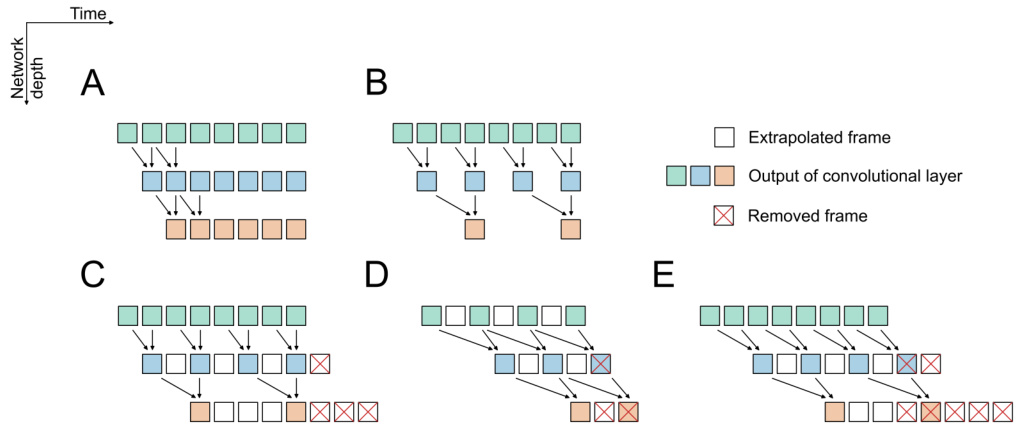

This figure illustrates different inference patterns of Scattered Online Inference (SOI) applied to a U-Net architecture. It showcases how SOI modifies the network’s inference process by selectively skipping computations and using prediction based on the partially predictive (PP) or fully predictive (FP) schemes. The figure depicts how different SOI configurations affect the flow of information within the U-Net during the odd and even inference steps.

This figure illustrates the different types of convolutional operations used in the Scattered Online Inference (SOI) method. It shows how standard convolutions are modified with striding and cloning to compress data, and how shifting is added to create predicted network states. The different operations are labeled (A-E) and visually represented using a time-series data diagram, emphasizing how SOI manipulates convolutions to skip redundant computations.

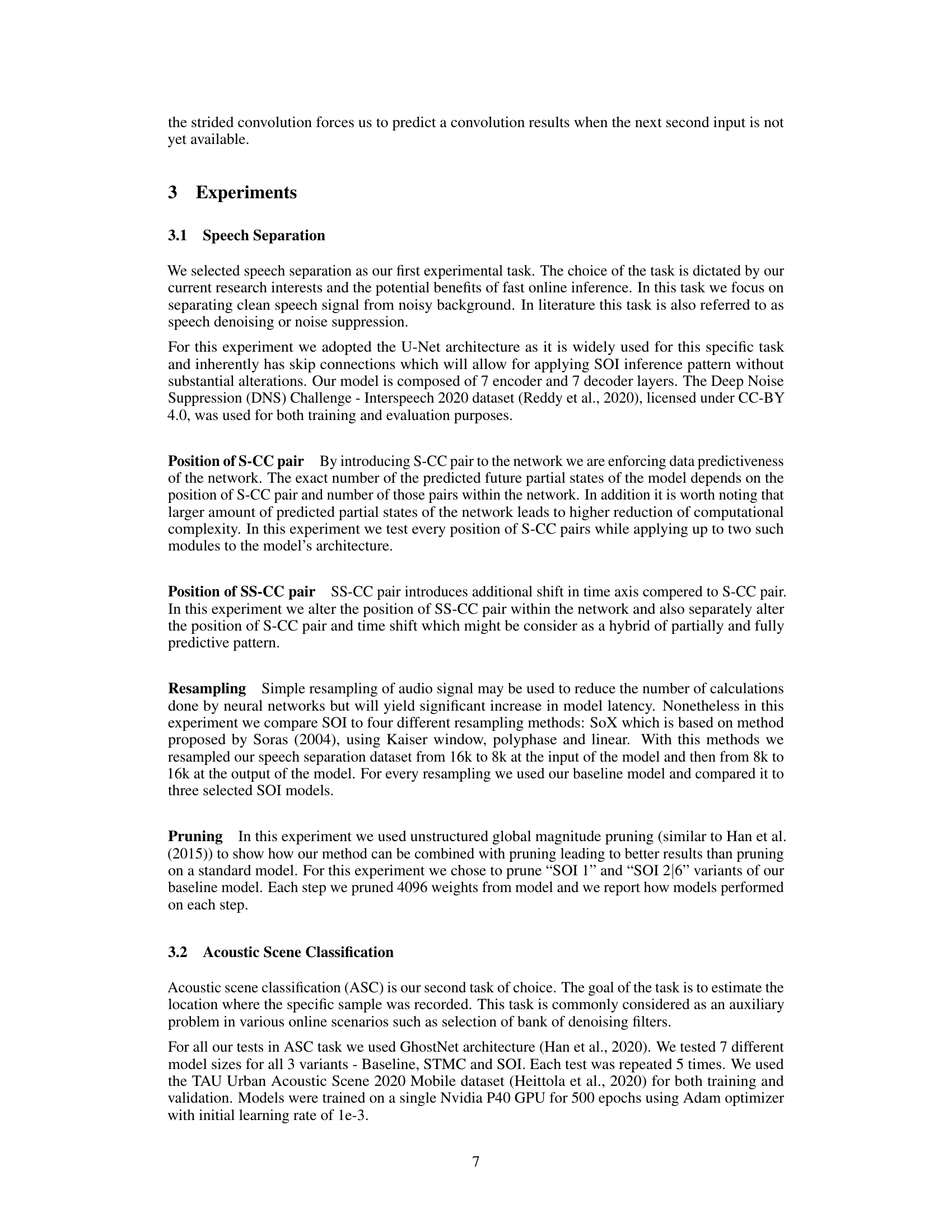

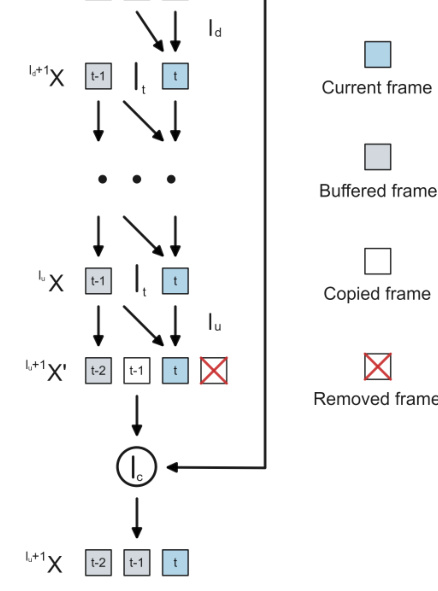

The figure shows the results of a speech separation experiment using Partially Predictive SOI (PP SOI). It plots the SI-SNRi (Scale-Invariant Signal-to-Noise Ratio Improvement) metric against the complexity reduction factor. Different lines represent various PP SOI configurations with one or two S-CC (Strided-Cloned Convolution) layers at different positions within the network. The horizontal dashed lines represent the baseline SI-SNRi values for comparison. The error bars indicate the standard deviation across multiple runs of each model.

The figure shows the results of speech separation experiments using Partially Predictive SOI (PP SOI). Different lines represent different PP SOI model configurations, varying the number and position of S-CC (Strided-Cloned Convolution) layers within the network. The x-axis represents the precomputed MMAC/s (Millions of Multiply-Accumulate operations per second), an indicator of computational complexity reduction. The y-axis represents the SI-SNRi (Scale-Invariant Signal-to-Noise Ratio Improvement), a metric for speech separation performance. The results demonstrate a trade-off between computational complexity reduction and SI-SNRi, with earlier introduction of S-CC layers leading to greater reduction in complexity but also a decrease in performance. Error bars show standard deviations.

This figure shows the results of the speech separation experiment using the Partially Predictive SOI (PP SOI) method. It displays the relationship between the Signal-to-Distortion Ratio Improvement (SI-SNRi) in dB and the peak complexity reduction factor for three different SOI configurations: a single S-CC layer, two S-CC layers (2xS-CC), and a standard STMC (Short-Term Memory Convolution) model. The x-axis represents the peak complexity reduction factor, which is a measure of the reduction in computation achieved by SOI relative to the standard method. The y-axis represents the SI-SNRi, a measure of the quality of the speech separation achieved. The graph visually demonstrates how PP SOI affects both computational cost and the quality of speech separation, with different configurations offering varying trade-offs between the two.

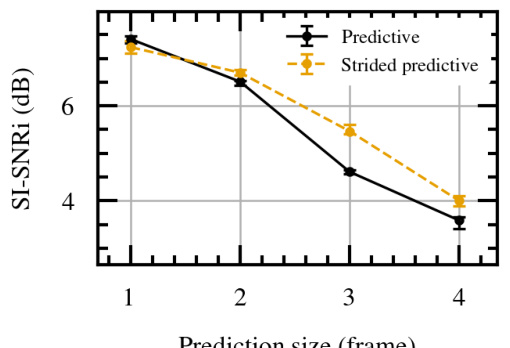

The figure compares the performance of standard convolutions and strided convolutions in predictive inference. It shows that strided convolutions generally perform better, particularly as the prediction size (number of frames) increases. This suggests that strided convolutions, which inherently incorporate a form of data compression, are more effective at generalizing to longer prediction horizons.

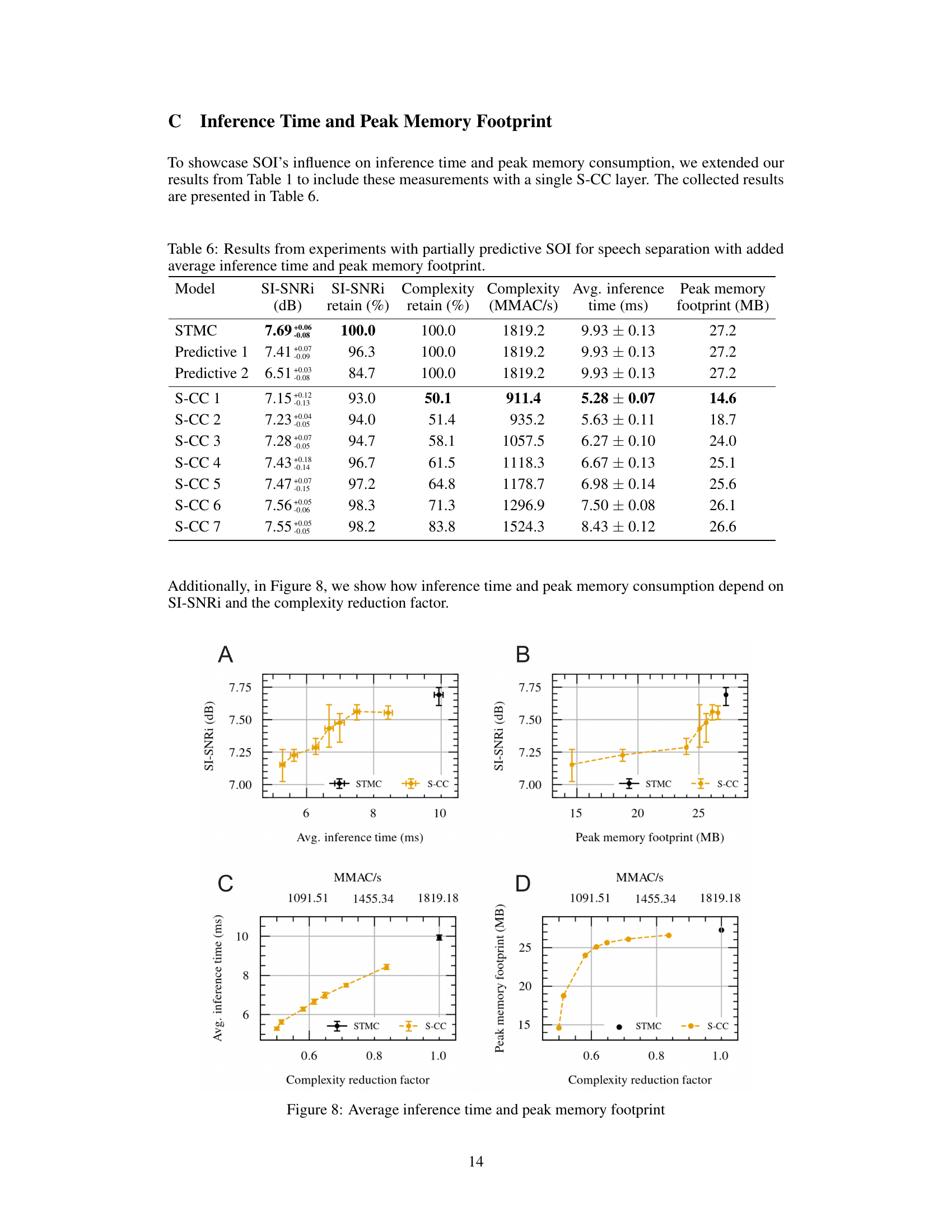

This figure shows how inference time and peak memory consumption depend on SI-SNRI and the complexity reduction factor. Subfigure A shows the relationship between SI-SNRi and average inference time, while subfigure B shows the relationship between SI-SNRi and peak memory footprint. Subfigures C and D show how average inference time and peak memory footprint change with different complexity reduction factors, respectively. The results suggest a linear relationship between inference time and both SI-SNRi and the complexity reduction factor. Peak memory consumption shows a more complex relationship, initially increasing rapidly with increasing complexity reduction before leveling off. These relationships suggest a trade-off between computational efficiency and model performance.

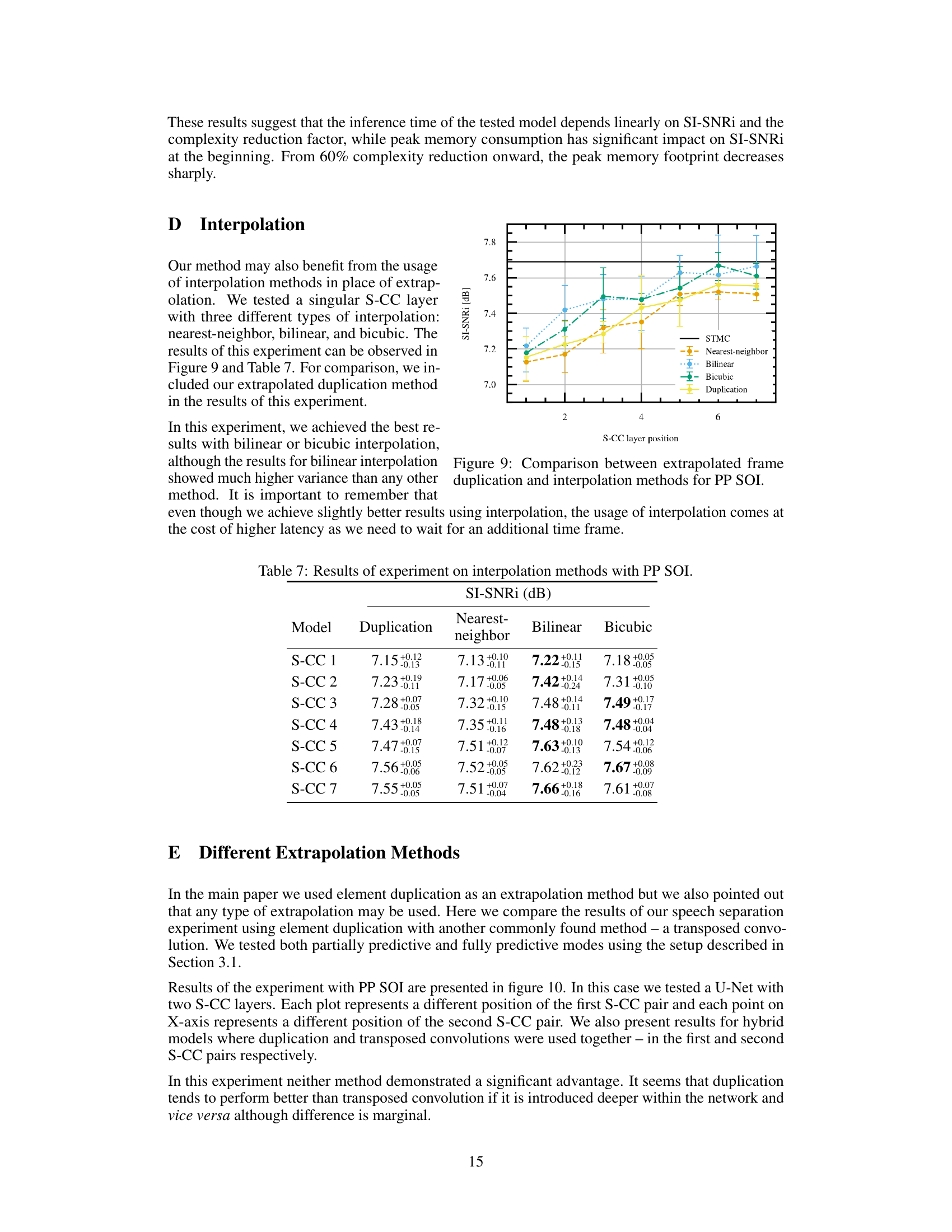

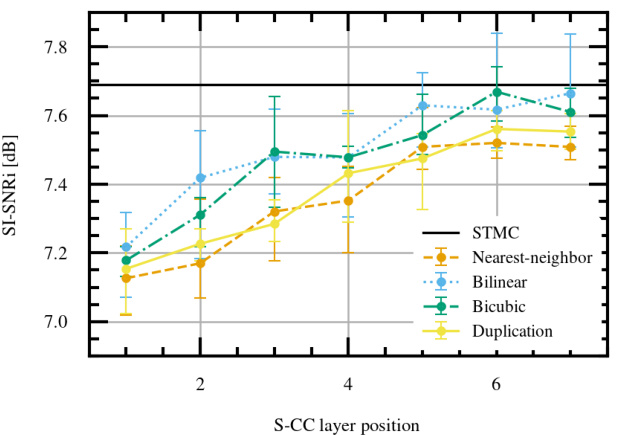

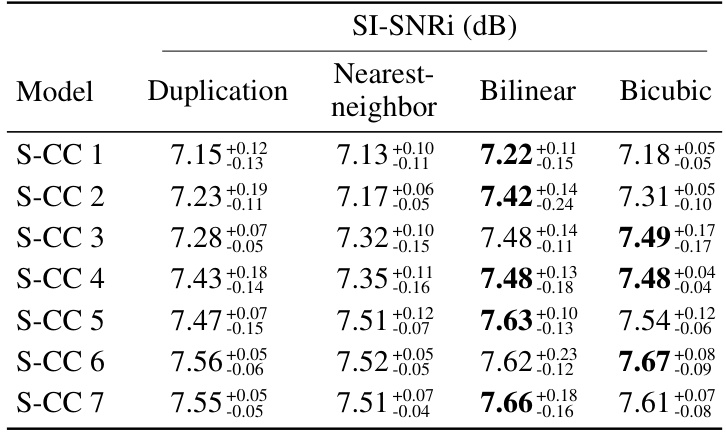

This figure compares the performance of different interpolation methods (nearest-neighbor, bilinear, bicubic) against the extrapolation method (duplication) used in Partially Predictive SOI (PP SOI). The x-axis represents the position of the single S-CC layer in the network, and the y-axis shows the resulting SI-SNRi (Scale-Invariant Signal-to-Noise Ratio), a metric for evaluating speech separation quality. The results indicate that bilinear and bicubic interpolation achieve better SI-SNRi than duplication, but bilinear shows higher variance.

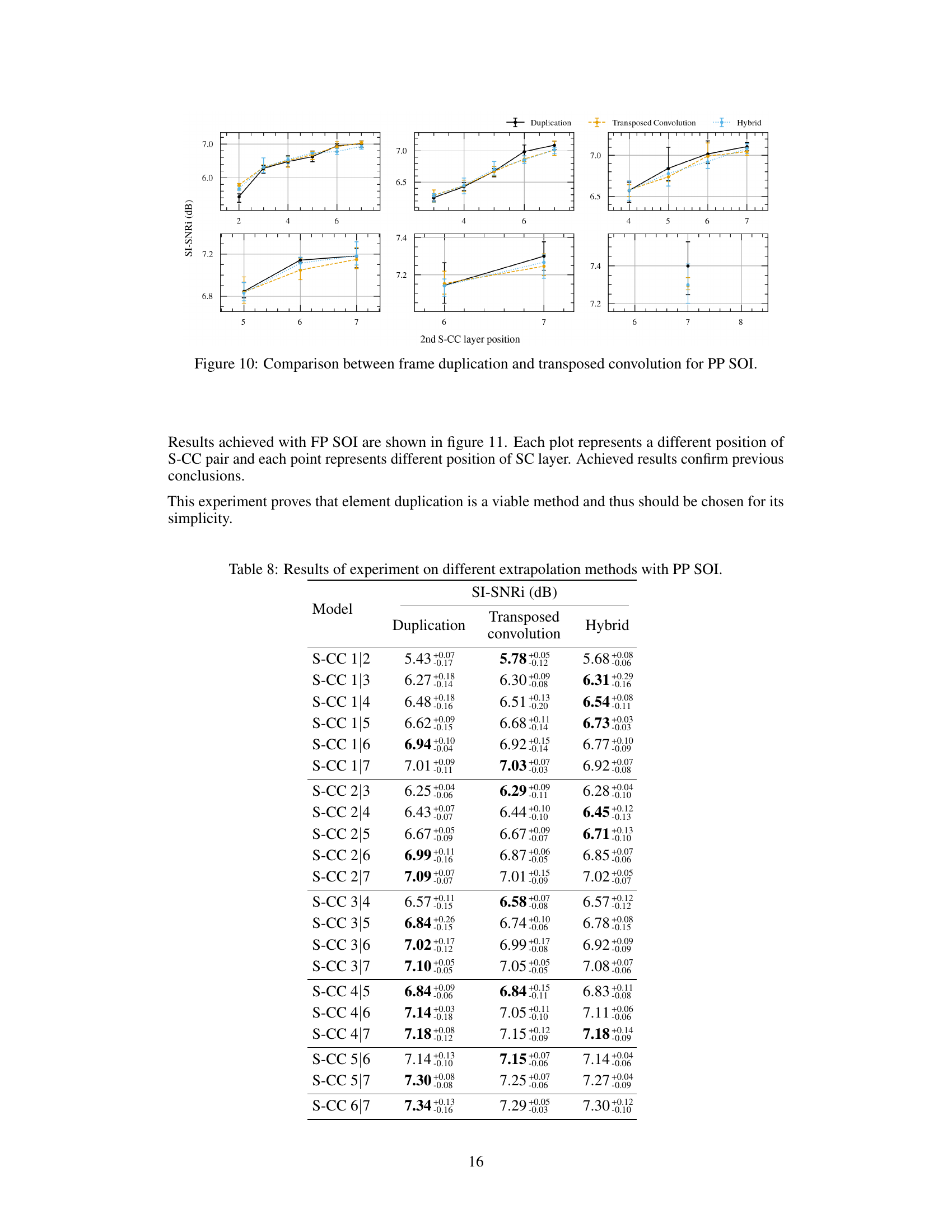

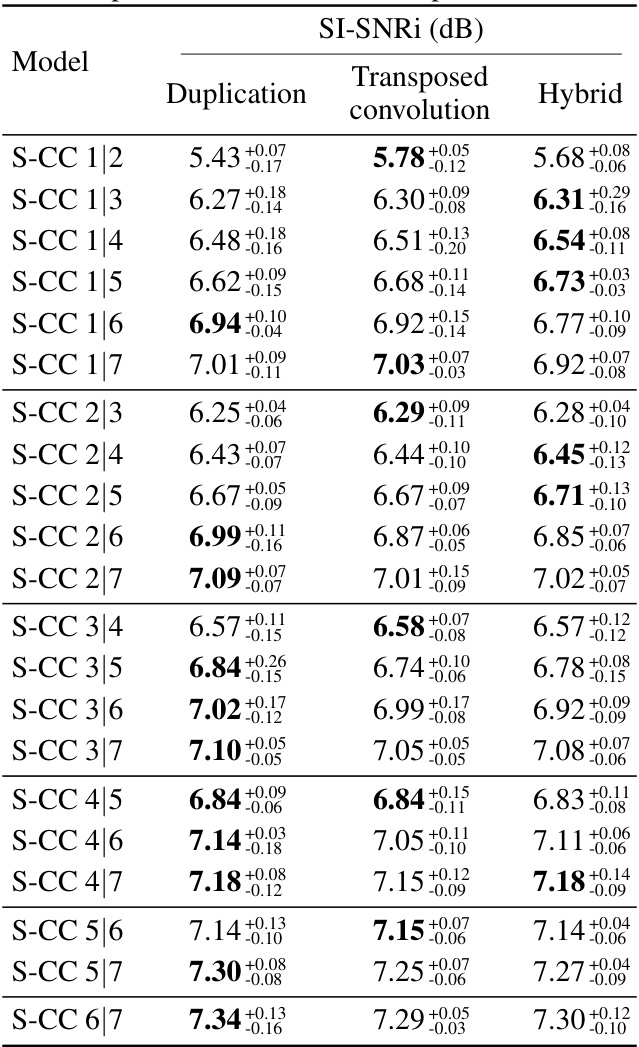

This figure compares the performance of frame duplication and transposed convolution as extrapolation methods within the Partially Predictive (PP) Scattered Online Inference (SOI) framework. The x-axis represents the position of the second S-CC (Strided-Cloned Convolution) layer, while the y-axis shows the SI-SNRi (Scale-Invariant Signal-to-Noise Ratio) metric. The results indicate that both methods yield similar performance, but the choice of method might depend on the position of the S-CC layers. There are 3 different plots to show the performance under different S-CC positions.

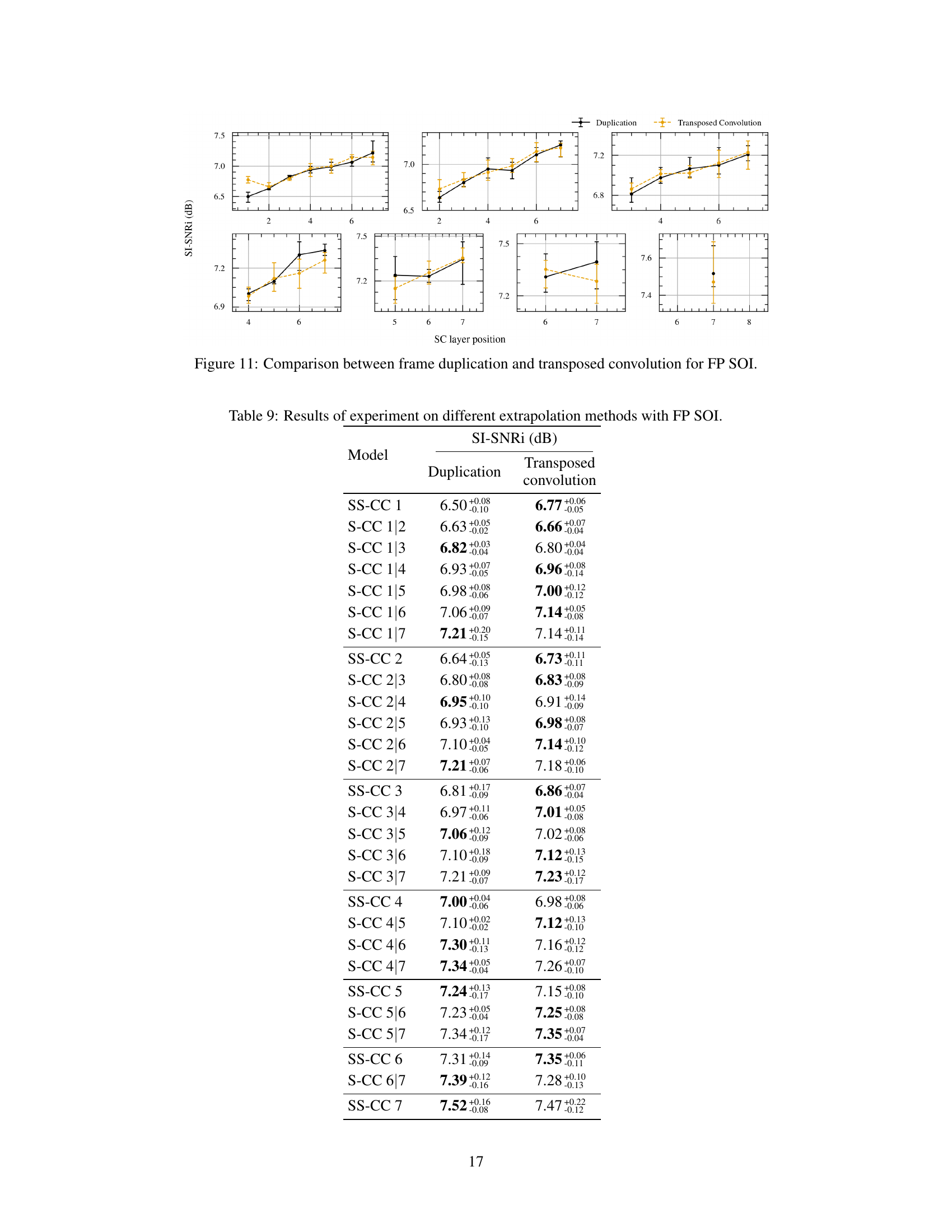

This figure compares the performance of using frame duplication versus transposed convolution as extrapolation methods within the Partially Predictive Scattered Online Inference (PP SOI) framework. The results are shown for different positions of the first and second strided-cloned convolution (S-CC) pairs within the network. Each plot represents a different placement of the first S-CC pair, and each point on the x-axis corresponds to a different position of the second S-CC pair. The plot illustrates the SI-SNRi (Signal-to-Interference Ratio plus Signal-to-Noise Ratio) metric, a common evaluation measure in speech separation. By comparing the SI-SNRi across different S-CC pair positions for both duplication and transposed convolution, the figure aims to determine which extrapolation method provides better performance in the PP SOI framework.

More on tables

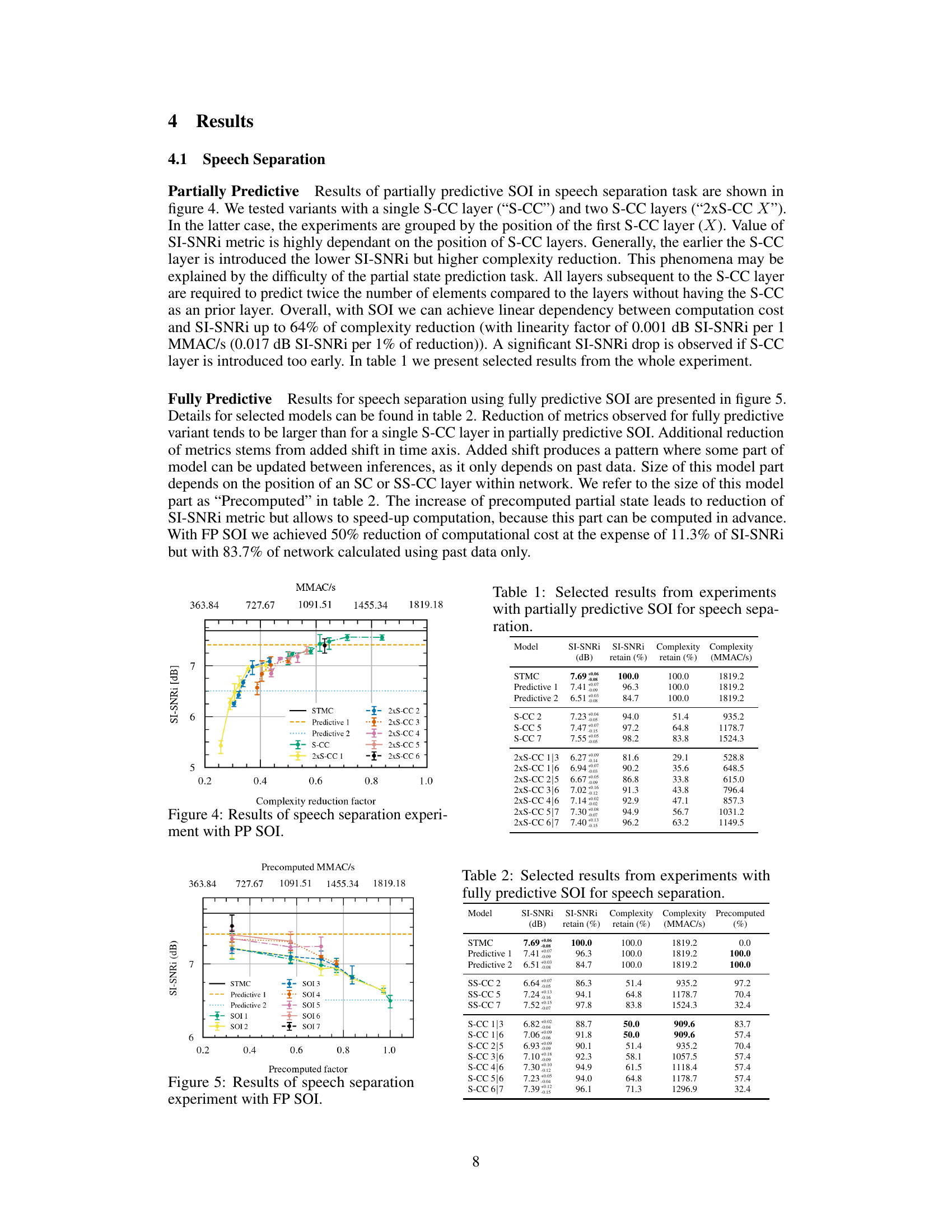

This table presents the results of speech separation experiments using fully predictive SOI. It shows the SI-SNRi (Signal-to-Interference plus Noise Ratio improvement), the percentage of SI-SNRi retained compared to the baseline STMC model, the percentage of computational complexity retained, the number of MMACs (Multiply-Accumulate operations) retained, and the percentage of the network calculated using precomputed data. The results highlight the tradeoff between complexity reduction and performance for different SOI configurations.

This table compares the performance of different resampling methods (Linear, Polyphase, Kaiser, SoX) against the proposed SOI method (specifically, SOI with S-CC 5, S-CC 2, and S-CC 1/3 configurations) in a speech separation task. It shows the achieved SI-SNRi (signal-to-noise ratio improvement) in dB and the corresponding computational complexity in MMAC/s (million multiply-accumulate operations per second). The results highlight the trade-off between model performance (SI-SNRi) and computational efficiency (complexity).

This table presents the results of acoustic scene classification (ASC) experiments using different ResNet models. It shows the top-1 accuracy, computational complexity (in GMAC/s), and the number of parameters for baseline, STMC, and SOI methods across various ResNet model sizes. The results demonstrate the impact of SOI on both accuracy and computational efficiency in the ASC task.

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing the performance of a predictive model with standard convolutions and a strided predictive model with strided convolutions. The experiment was conducted for different prediction lengths, ranging from 1 to 4 frames. The table shows the SI-SNRi (Scale-Invariant Signal-to-Noise Ratio) for each model and prediction length, indicating the model’s performance in terms of speech separation quality. The inclusion of error bars (+/- values) demonstrate the variability in the model’s performance across different training runs. The results suggest that strided convolutions might be advantageous for longer predictions, possibly due to their improved ability to generalize from limited contextual data.

This table presents the results of experiments using partially predictive Scattered Online Inference (SOI) for speech separation. It shows the Signal-to-Interference Ratio plus Noise (SI-SNRi) improvement, the percentage of complexity retained in the SOI model compared to the baseline STMC model, the average inference time in milliseconds, and the peak memory footprint in MB for different SOI configurations (varying the placement of the S-CC layer within the model). It provides a comprehensive analysis of the trade-off between computational efficiency and model performance. The results indicate that SOI achieves substantial computational savings at a relatively modest loss of SI-SNRi.

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing different interpolation methods (duplication, nearest-neighbor, bilinear, bicubic) with Partially Predictive SOI (PP SOI) for speech separation. The table shows the SI-SNRi (Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio in dB) achieved for each interpolation method across seven different positions of the S-CC (Strided-Cloned Convolution) layer in the network. Higher SI-SNRi values indicate better performance.

This table presents the results of an experiment comparing different extrapolation methods (Duplication, Transposed convolution, and Hybrid) for the Partially Predictive (PP) Scattered Online Inference (SOI) method. The experiment was conducted on a speech separation task using a U-Net architecture with two S-CC layers. Each row represents a different configuration of S-CC layer positions (e.g., S-CC 1/2 means the first S-CC layer is at position 1 and the second at position 2). The SI-SNRi metric is used to evaluate the performance of each configuration. The table shows that there is no significant difference in the performance among the methods. The hybrid method, which combines duplication and transposed convolution, shows results comparable to the individual methods.

This table presents the results of experiments using partially predictive SOI for speech separation. It shows the SI-SNRi (signal-to-noise ratio improvement), the percentage of complexity retained, the average inference time in milliseconds, and the peak memory footprint in MB for different configurations of SOI, including various placements of the S-CC layer. It allows comparison of the model’s performance with different levels of computational reduction. The STMC (baseline) results are also included for comparison.

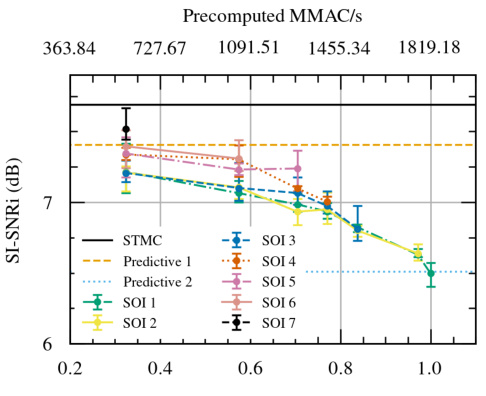

This table presents the results of applying SOI to video action recognition tasks using different model architectures (ResNet-10 and MoViNet). It shows the top-1 accuracy and computational complexity (in GMAC/s) for both regular models and models using the SOI method. The results demonstrate the impact of SOI on both accuracy and computational efficiency in this domain.

This table presents the results of acoustic scene classification (ASC) experiments using different ResNet models. It compares the top-1 accuracy, complexity (in GMAC/s), and the number of parameters for three different methods: Baseline (original ResNet), STMC (Short-Term Memory Convolution), and SOI (Scattered Online Inference). The results are shown for four different ResNet model sizes (18, 34, 50, and 101 layers). The table demonstrates the impact of SOI on improving accuracy while reducing computational complexity compared to both Baseline and STMC.

Full paper#