↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

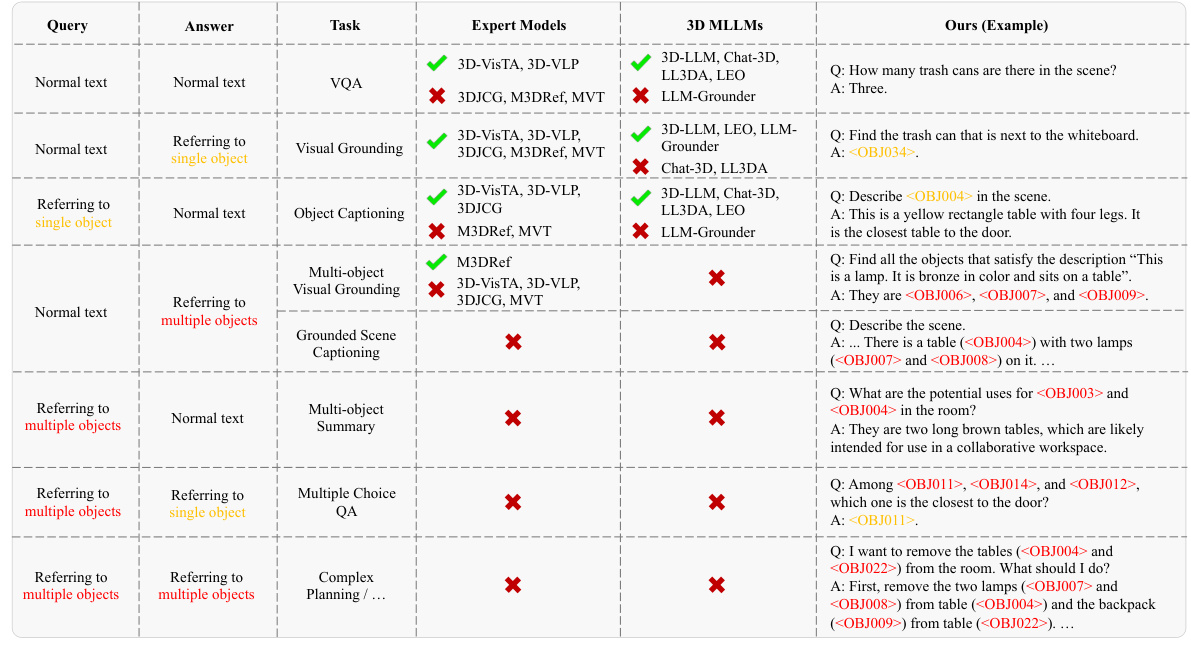

Current 3D Large Language Models (LLMs) struggle with complex scene understanding, particularly object referencing and grounding, due to limited data. Previous approaches often use location tokens or hidden scene embeddings which are inefficient for object-level interactions. This restricts generalizability and performance.

The proposed ‘Chat-Scene’ model tackles this by using object identifiers to represent 3D scenes as sequences of object-level embeddings derived from 2D and 3D representations. This unified question-answering format makes training more efficient, requiring only minimal fine-tuning on downstream tasks. The results show significant improvements across benchmarks, demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach in enhancing object-level interaction and overall scene comprehension.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it significantly improves 3D scene understanding by introducing object identifiers and object-centric representations. This approach addresses the limitations of existing methods, especially in handling complex scenes and mitigating data scarcity issues. The unified question-answering format and minimal fine-tuning requirements make it highly efficient and broadly applicable, paving the way for more advanced 3D scene-language models.

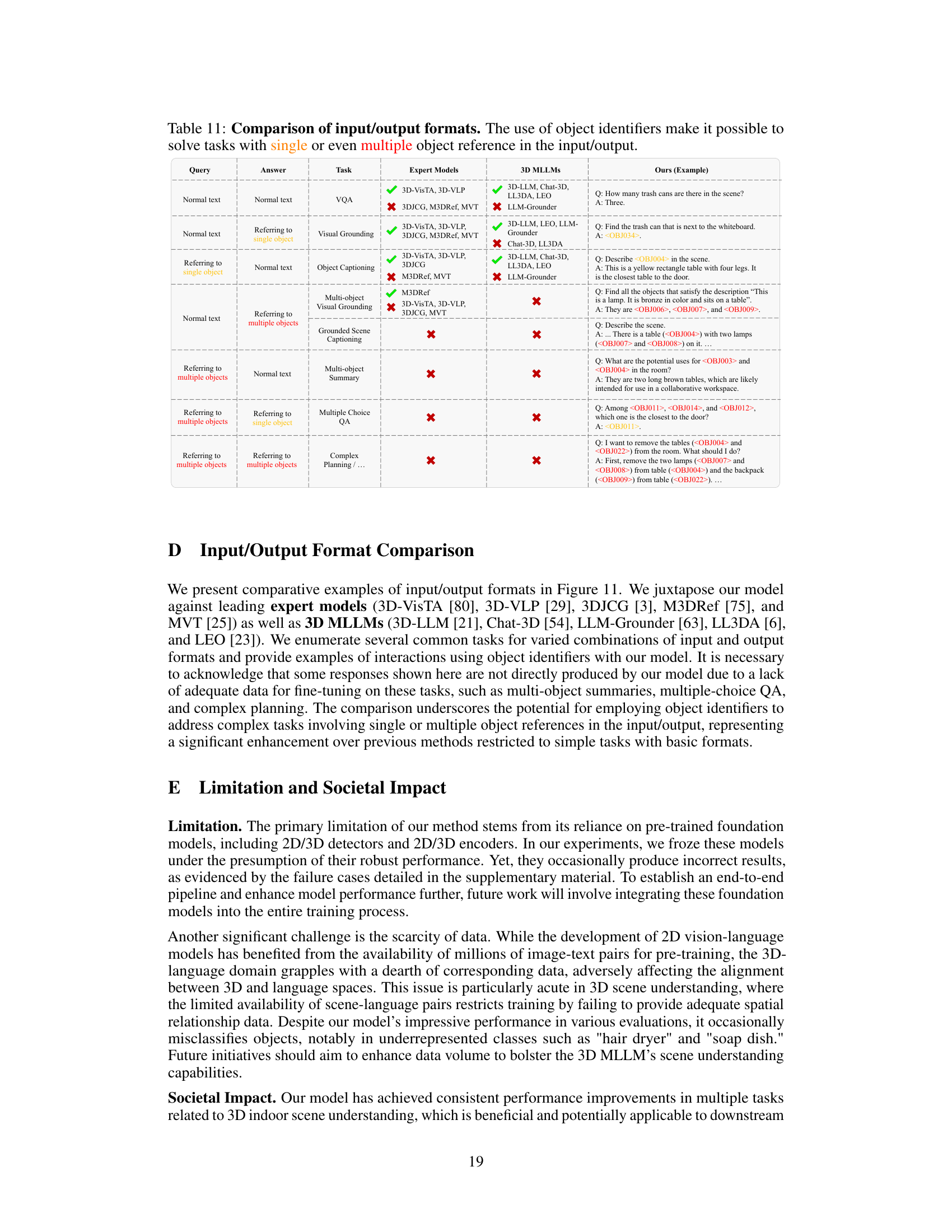

Visual Insights#

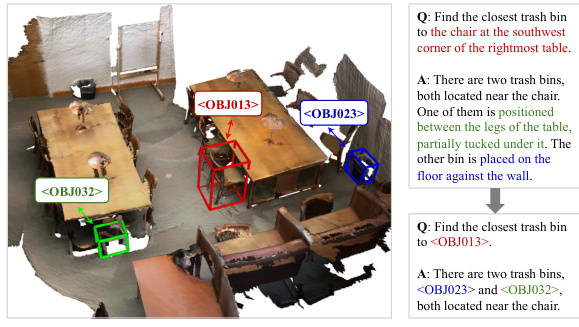

This figure shows a 3D scene with three objects detected and assigned unique identifiers:

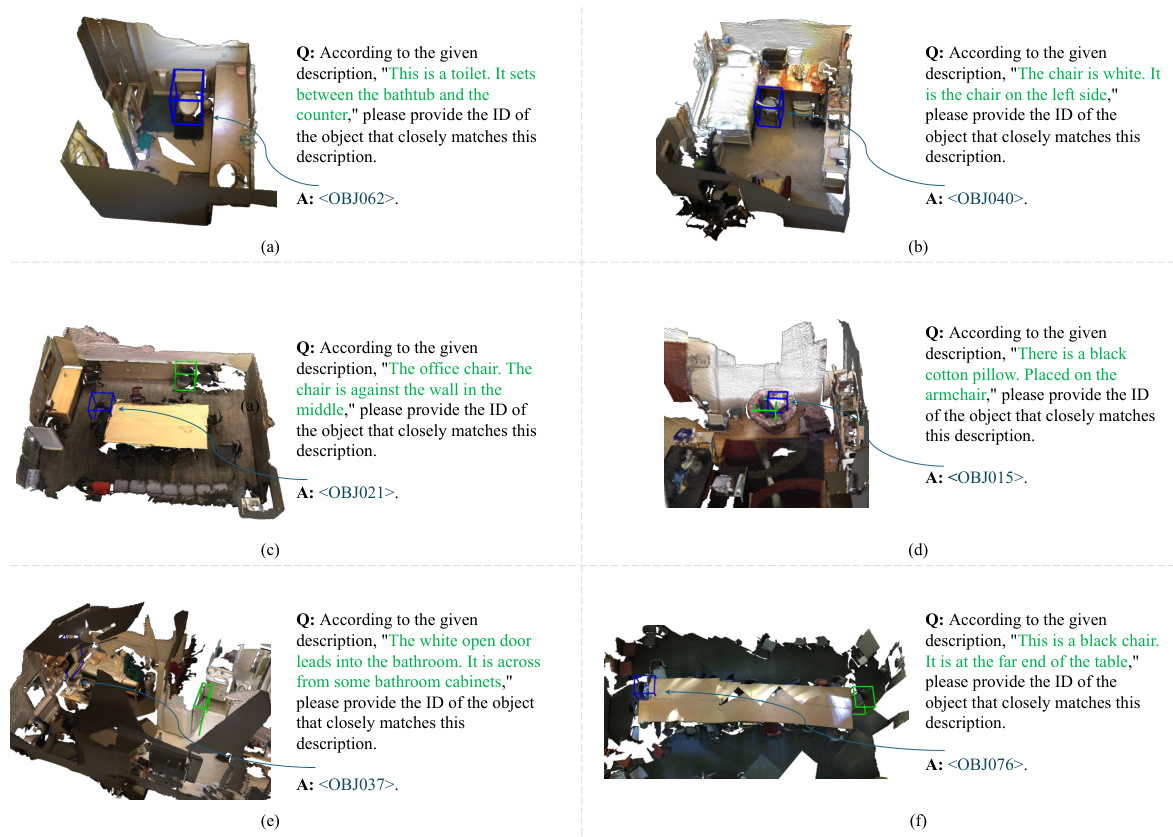

, , and . The example demonstrates how the model uses these identifiers to answer a question about the objects in the scene. The first question uses a more complex, descriptive phrasing to locate the trash bin, while the second question uses the object identifier for conciseness and accuracy.

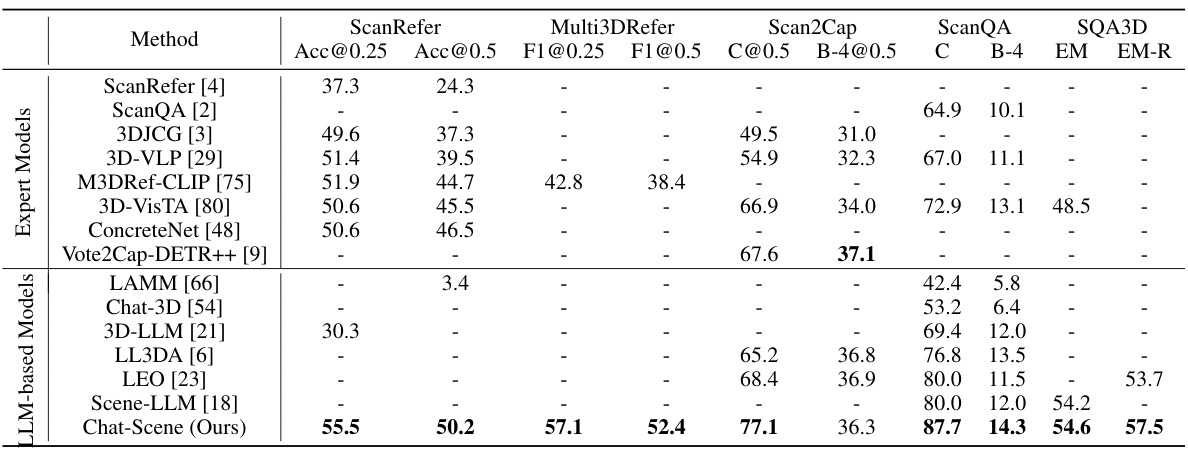

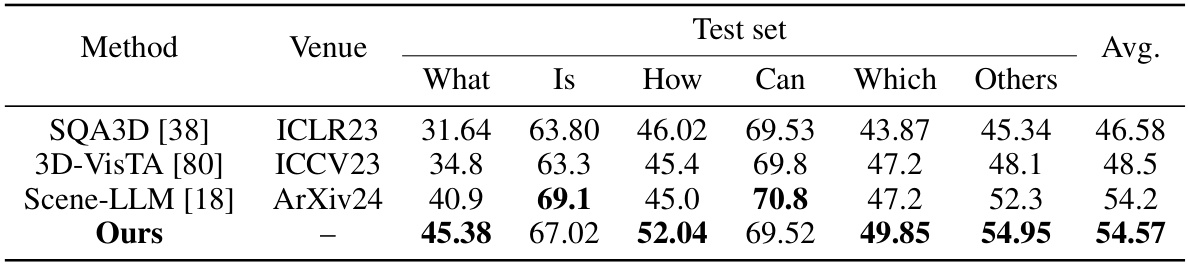

This table compares the performance of different models on five 3D scene understanding benchmarks: ScanRefer, Multi3DRefer, Scan2Cap, ScanQA, and SQA3D. It categorizes the models into two groups: expert models, which are specifically designed and trained for each task, and LLM-based models, which are general-purpose and can be adapted to different tasks with minimal fine-tuning. The results show that the proposed Chat-Scene model, an LLM-based model, outperforms existing methods across all benchmarks.

In-depth insights#

Object-centric 3D LLMs#

Object-centric 3D Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a significant advancement in 3D scene understanding. By focusing on objects as primary units of interaction, these models move beyond holistic scene representations. This object-centric approach enables more precise object referencing and grounding, crucial for complex tasks like visual question answering and visual grounding. The use of unique object identifiers facilitates efficient interactions with the scene at the object level, transforming diverse tasks into a unified question-answering format. Well-trained object-centric representations, derived from rich 2D or 3D data, further enhance performance, mitigating the impact of limited scene-language data. This paradigm shift allows for a more intuitive and flexible interaction with 3D environments, paving the way for more robust and generalizable 3D scene understanding capabilities. However, challenges remain in handling complex spatial relationships and overcoming data scarcity issues. Further research should explore methods to improve object detection and representation in challenging scenarios, expanding the potential of object-centric 3D LLMs for real-world applications.

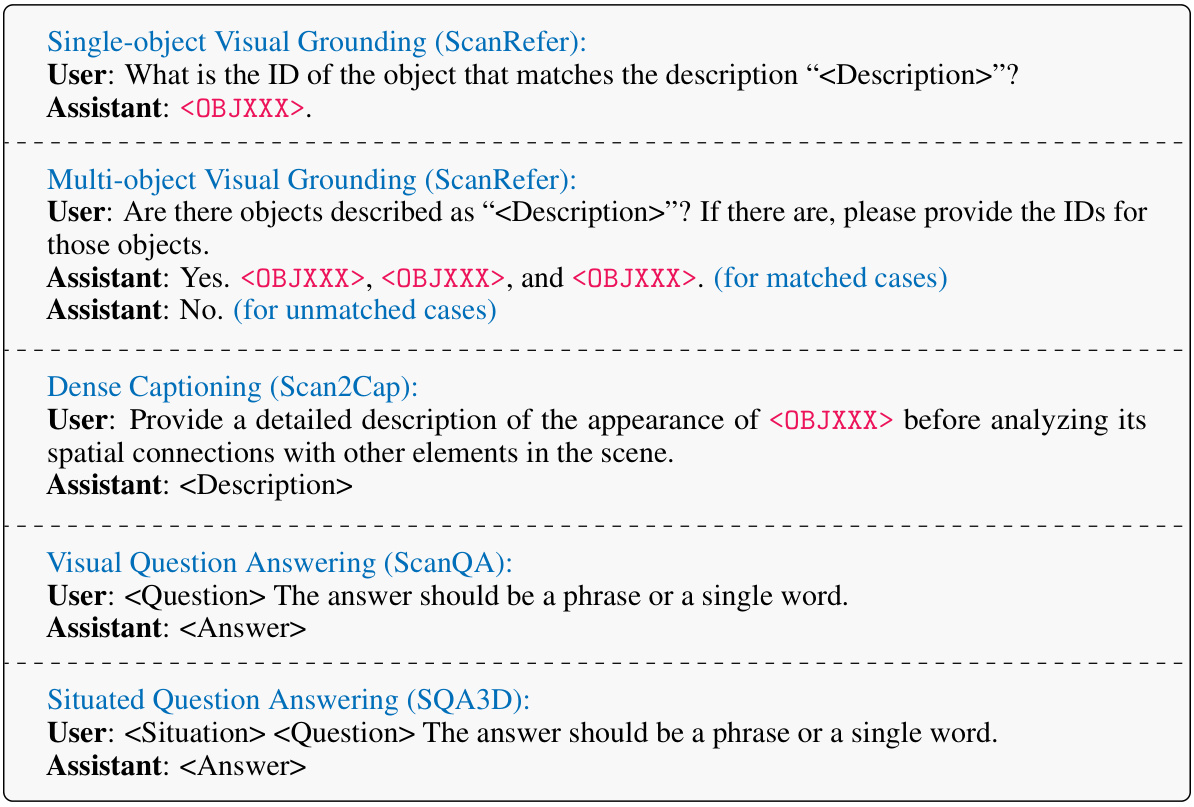

Unified Task Format#

The concept of a “Unified Task Format” in a 3D scene understanding research paper is crucial for efficient model training and improved generalization. By framing diverse tasks—like visual grounding, dense captioning, and visual question answering—within a single, consistent question-answering paradigm, the researchers elegantly address the challenge of limited 3D scene-language data. This approach allows for joint training, eliminating the need for task-specific heads and thus reducing model complexity. The key innovation is likely the use of object identifiers, which transform complex spatial reasoning into a more manageable sequence-to-sequence problem for the language model. This method is particularly effective because it enables efficient object referencing and grounding, even in intricate scenes, overcoming limitations of previously proposed methods that relied on less efficient location tokenization. The unified format simplifies both the training process and enables the model to learn more generalizable features, leading to enhanced performance across various benchmarks. This strategy represents a substantial advance in 3D scene understanding, effectively mitigating the impact of data scarcity and setting a new standard for future research.

Data Scarcity Mitigation#

The pervasive challenge of data scarcity in 3D scene understanding is directly addressed by the paper. The authors creatively circumvent this limitation by employing object-centric representations. Instead of relying on large, scene-level embeddings which require massive datasets, they leverage readily available and well-trained 2D and 3D object detectors to extract rich feature embeddings. This approach cleverly transforms the problem into a sequence of object-level embeddings, reducing the dependence on extensive scene-language paired data. The use of unique object identifiers further enhances efficiency, enabling seamless object referencing and grounding within the LLM framework and simplifying model training. This innovative approach significantly mitigates the effects of data scarcity, enabling robust performance across diverse downstream tasks and pushing the state-of-the-art on multiple benchmark datasets.

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In this context, it would involve analyzing the impact of removing or altering specific aspects of the 3D scene understanding model, such as the object identifiers, the multi-modal object-centric representations, and the fusion method. Key insights would emerge by comparing the performance of the full model against the simplified variants, revealing which elements are crucial for accuracy and efficiency. For instance, if removing object identifiers significantly degrades performance, then it strongly suggests their importance in enabling effective object referencing and grounding. Similarly, evaluating variants using different representation methods (single vs. multi-view, 2D vs. 3D) would highlight the best approach for capturing scene semantics. The findings of the ablation study would thus offer valuable insights into the architecture’s design choices and its relative strengths and weaknesses, guiding future model improvements and potentially simplifying the system while maintaining performance.

Video Input Adaptation#

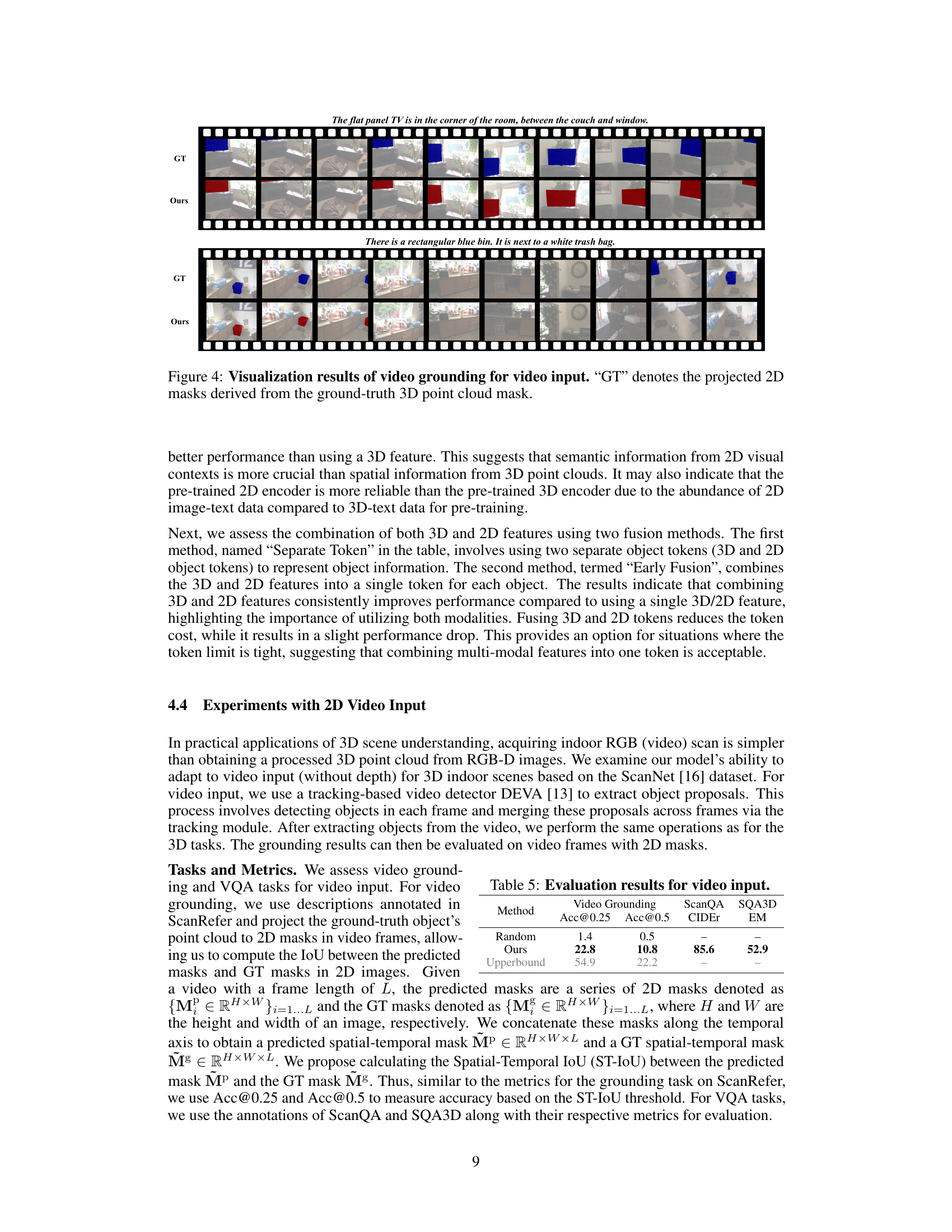

The adaptation of the model to handle video input is a significant extension, showcasing its robustness and potential real-world applicability. The use of a tracking-based video detector (DEVA) to extract object proposals from video frames is a practical choice, overcoming the absence of depth information typically present in 3D point cloud data. Merging object proposals across frames using a tracking module is crucial for maintaining object consistency across the video sequence. Evaluation on video grounding and VQA tasks demonstrates comparable performance to models trained solely on 3D point cloud data, highlighting the model’s versatility and ability to generalize across different data modalities. The inclusion of an upper bound in the performance evaluation is a rigorous approach, effectively isolating and quantifying the impact of the video detection stage. While the tracking-based approach may not be perfect, leading to some accuracy loss in comparison to the 3D upperbound, it demonstrates the model’s capacity to perform well despite potential noise and inaccuracies in the input. The successful transfer to video data underscores the model’s potential for broader real-world applications, such as video-based scene understanding and interactive virtual environments. Further research could focus on improving the video object detection stage for more robust and accurate object tracking in dynamic environments.

More visual insights#

More on figures

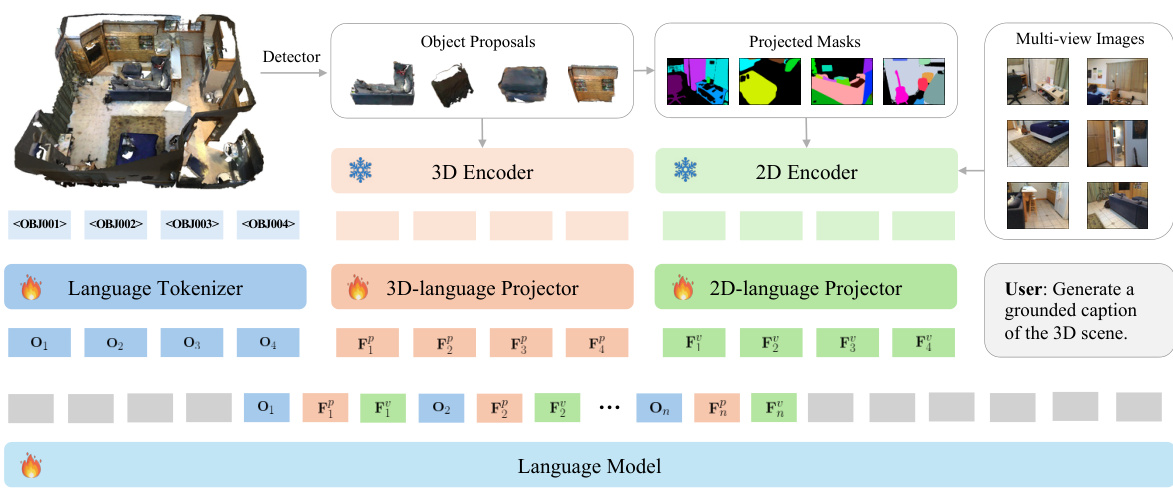

The figure illustrates the architecture of the Chat-Scene model. It starts with a 3D scene’s point cloud as input. A detector identifies individual objects within the scene, assigning each a unique object identifier. These objects are then processed by both 3D and 2D encoders to extract features, which are projected into a space compatible with the language model. The object identifiers and encoded features are combined and fed into the language model (LLM) to generate responses that can efficiently reference objects in the 3D scene.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed model, which processes a 3D scene’s point cloud. First, it uses a pre-trained detector to break the scene into object proposals. Then, 3D and 2D encoders extract object-centric representations from the point cloud and multi-view images, respectively. These representations are projected into the language model’s embedding space and combined with unique object identifiers, creating object-level embeddings. Finally, these embeddings are fed into a Large Language Model (LLM) for interaction and object referencing.

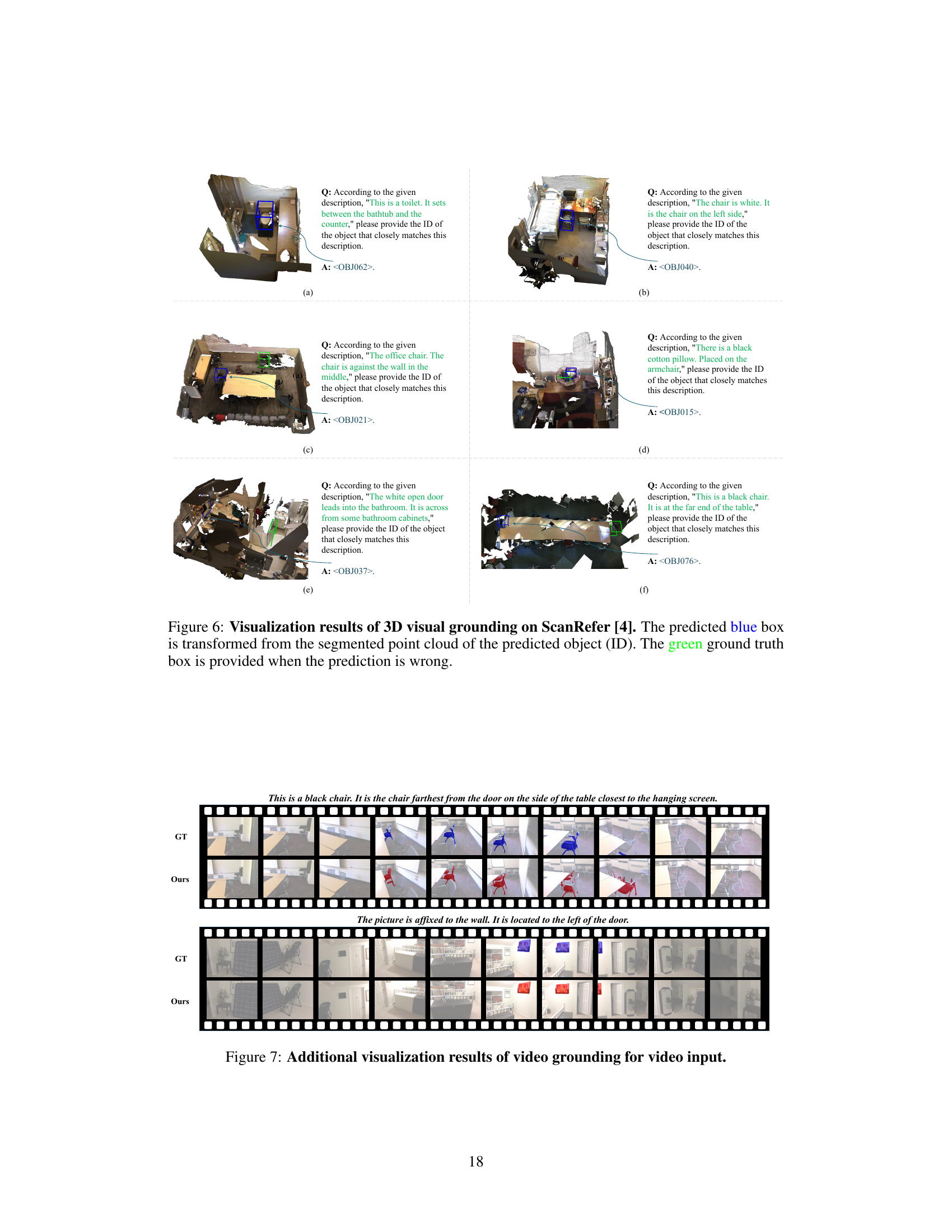

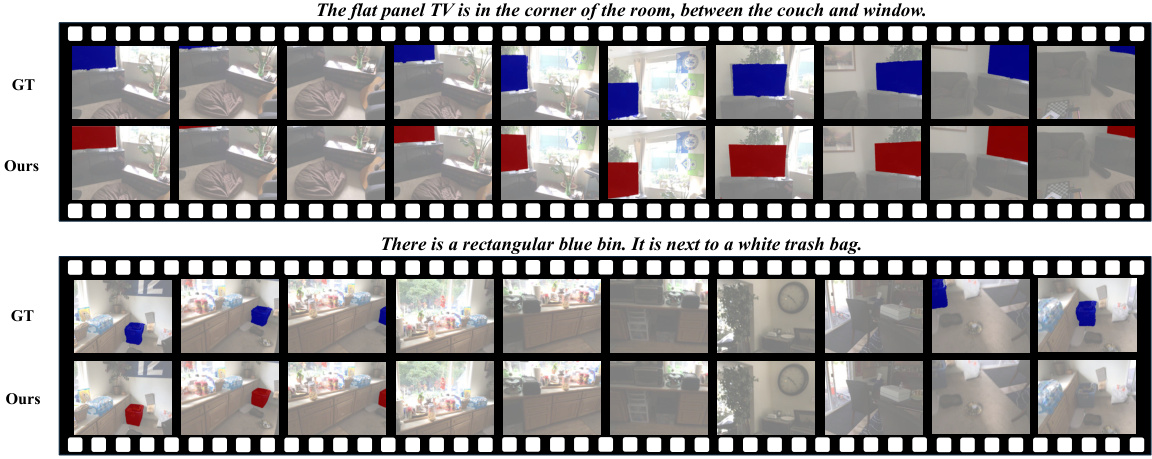

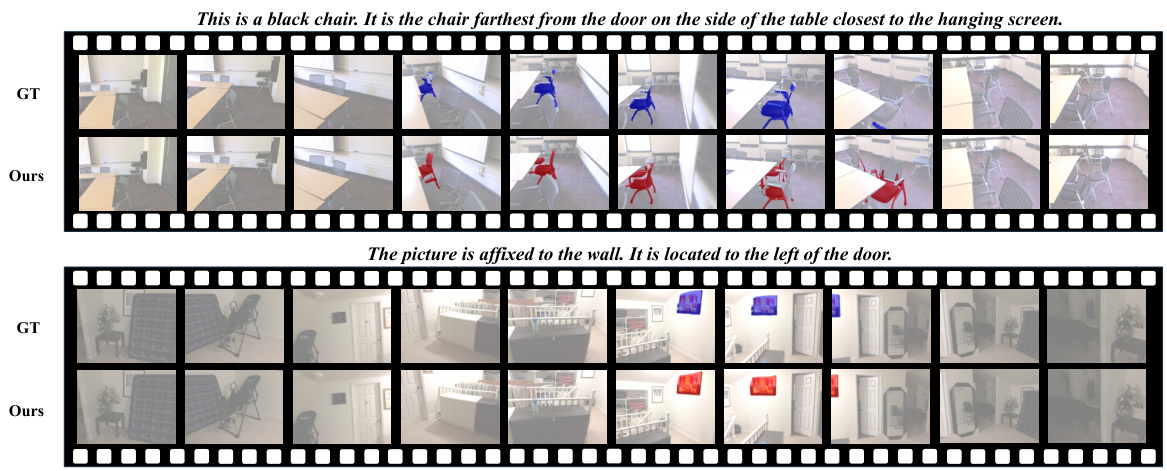

This figure visualizes the results of video grounding. It shows a comparison between the ground truth (GT) and the model’s predictions (‘Ours’) for localizing objects in video frames. The GT masks are projections of the ground truth 3D point cloud masks onto the 2D video frames. The model’s predictions are shown as red boxes, while the GT masks are shown as blue boxes. Two examples are provided showing the model’s performance at locating a TV and a blue rectangular bin.

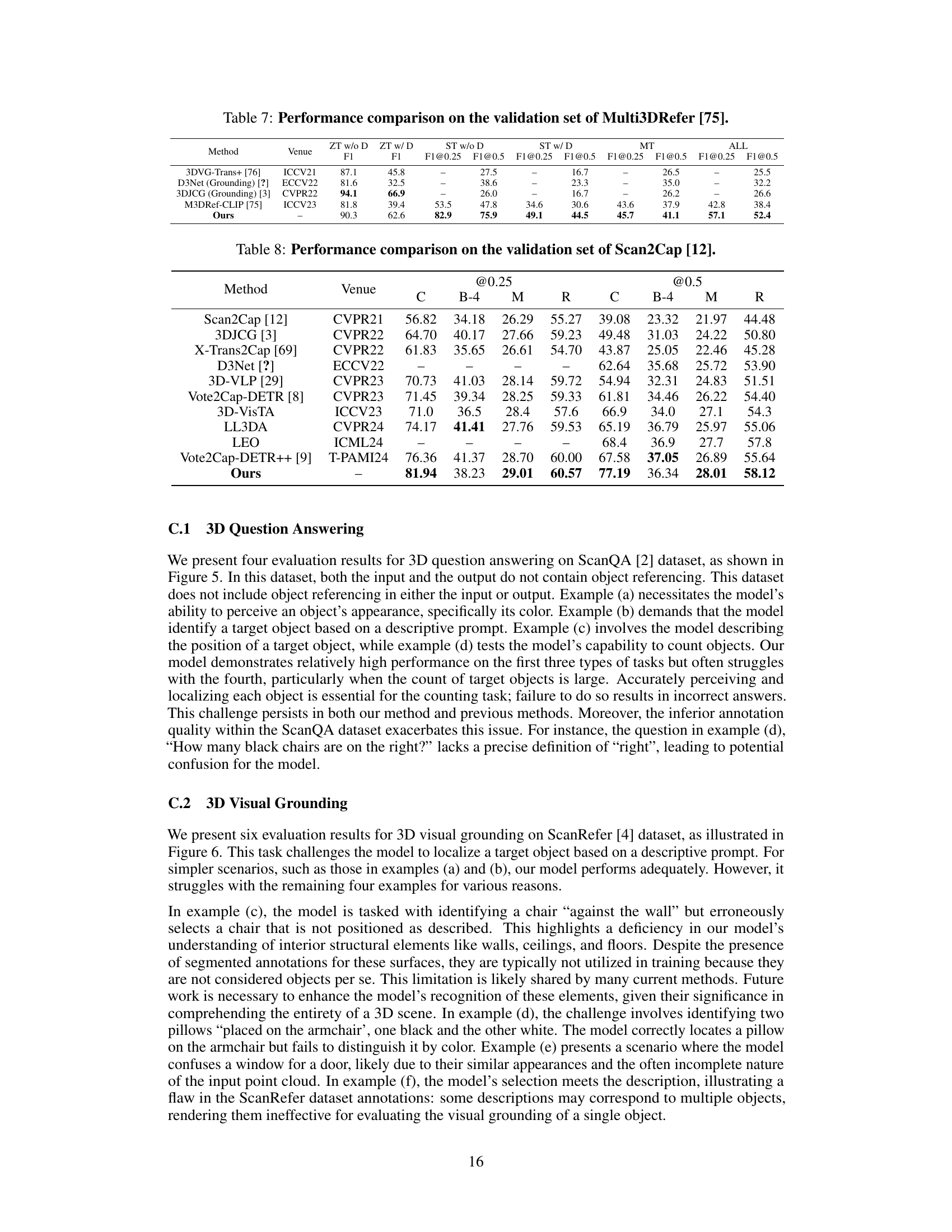

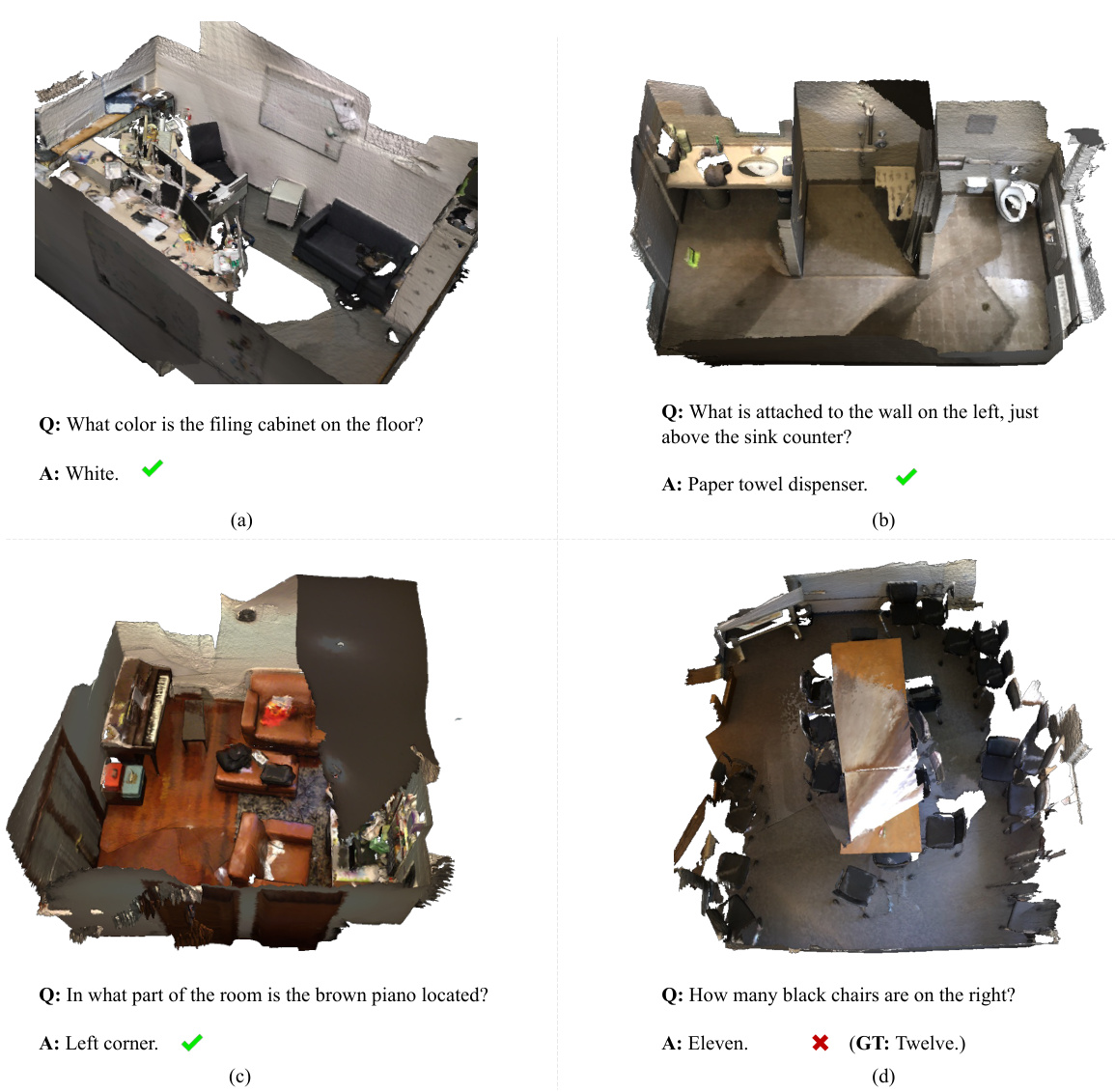

This figure visualizes four examples of 3D question answering on the ScanQA dataset. Each example shows a 3D scene with a question and the model’s answer. The green checkmarks indicate correct answers, while the red ‘x’ indicates an incorrect answer. The examples demonstrate the model’s ability to answer various types of questions related to object properties, location, and counting, highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of the model’s 3D scene understanding capabilities.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Chat-Scene model. It shows how a 3D point cloud is processed: first, a detector identifies objects; then, 3D and 2D encoders extract features for each object. These features, combined with unique object identifier tokens, are fed into a language model (LLM) as a sequence of object-level embeddings. This allows for efficient referencing and grounding of objects within the scene.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Chat-Scene model. The model takes a 3D point cloud as input, which is first processed by an object detector to identify individual objects. Each object is then encoded using both 3D and 2D encoders, which capture different aspects of the object’s appearance and spatial relationships. These object-centric representations are projected into the embedding space of a language model and concatenated with unique object identifier tokens. Finally, these combined embeddings are fed into a language model (LLM) for downstream tasks. The use of object identifiers enables efficient referencing and grounding of objects during interaction with the LLM.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Chat-Scene model, which processes 3D scene point cloud data. The process begins with object detection and proposal generation using a pre-trained detector. Object-centric representations are extracted from both 3D (using a 3D encoder) and 2D (multi-view images, using a 2D encoder) sources. These object representations are projected into the language model’s embedding space and combined with unique object identifiers. The resulting sequence of object-level embeddings is then input into the large language model (LLM) for scene understanding and interaction. The use of object identifiers allows for more efficient object referencing during interactions with the model.

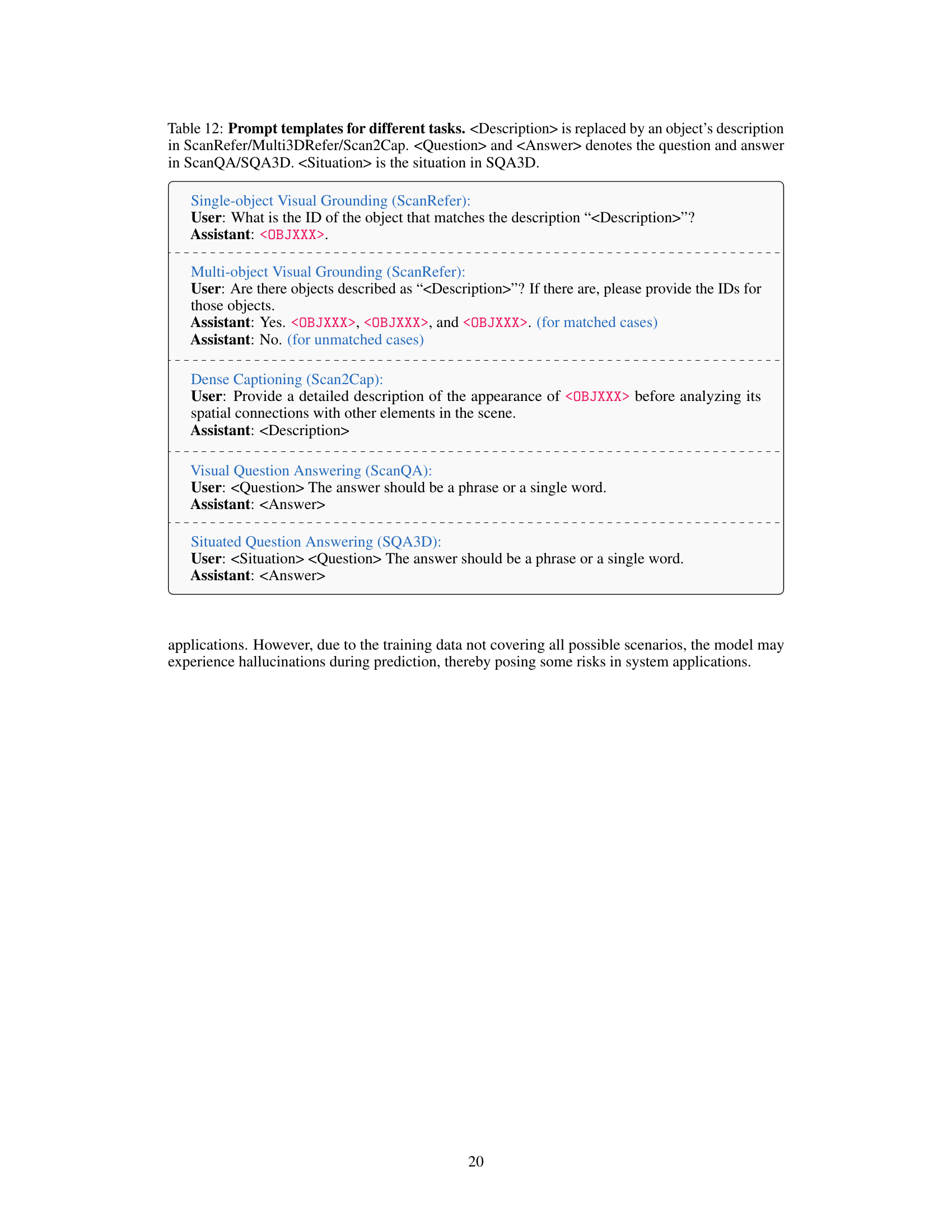

More on tables

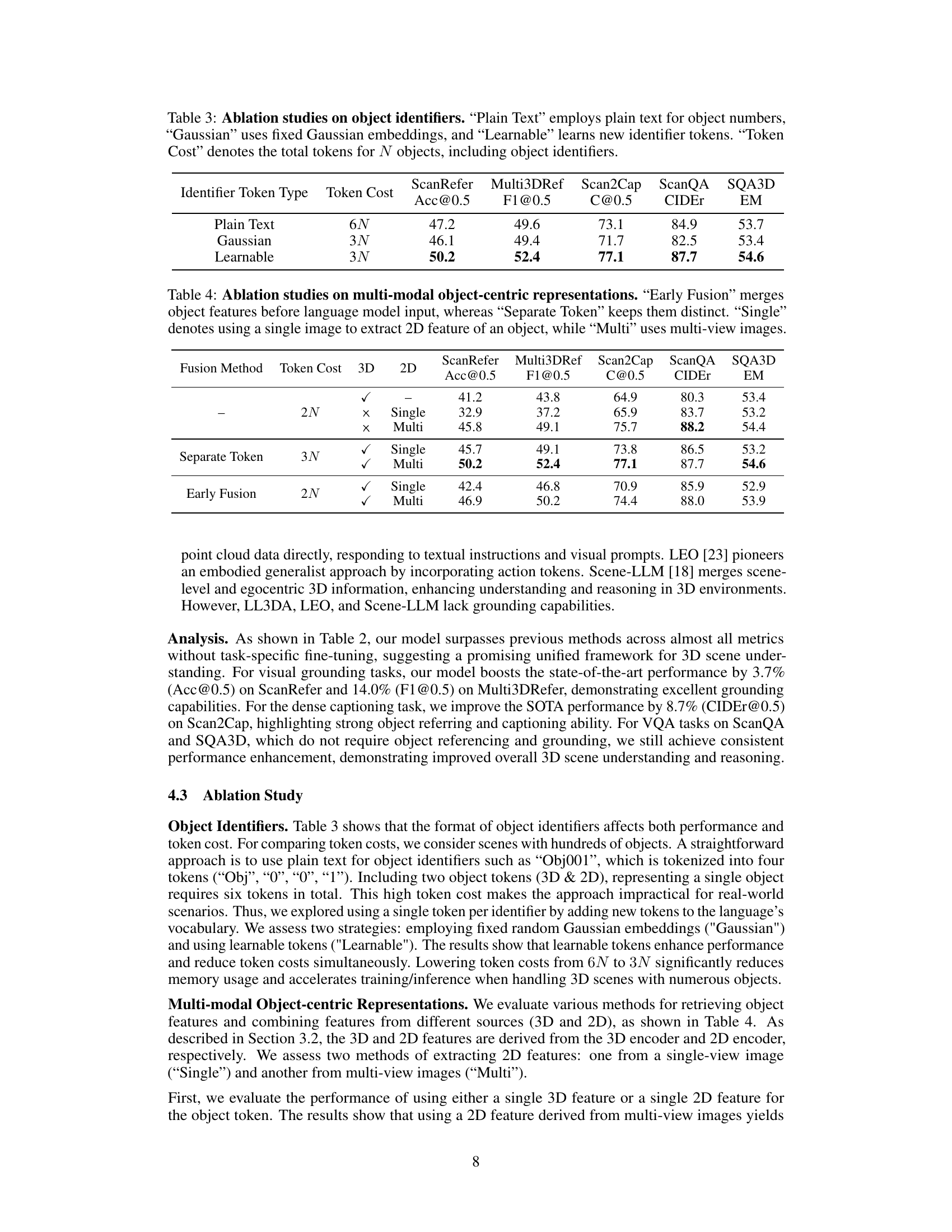

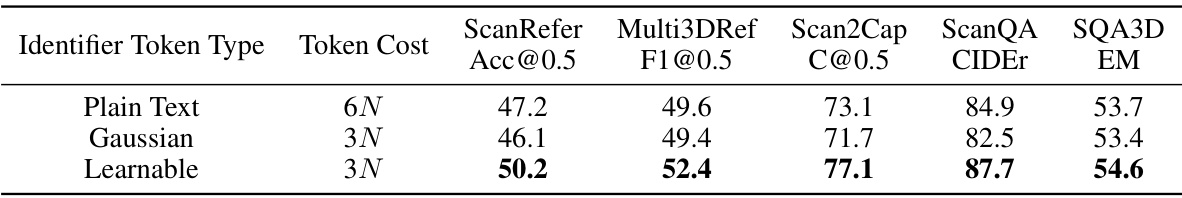

This table presents the results of ablation studies performed to evaluate the impact of different object identifier token types on the model’s performance across various downstream tasks. Three different identifier types were tested: ‘Plain Text’ (using numerical text for object IDs), ‘Gaussian’ (using fixed Gaussian embeddings), and ‘Learnable’ (learning new identifier tokens). The table shows the performance (accuracy and F1 scores) for each task and identifier type, along with the total number of tokens used for N objects.

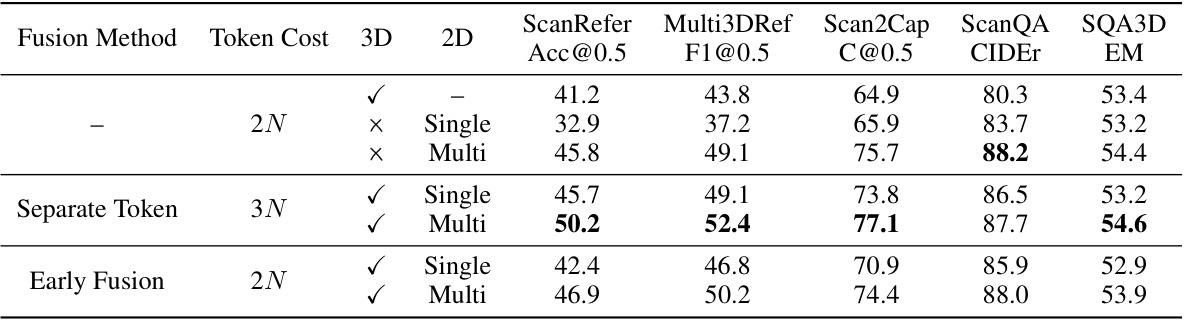

This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of different multi-modal object-centric representation methods on the model’s performance across various downstream tasks. It compares using a single modality (3D or 2D features from single or multiple views), early fusion of 3D and 2D features, or keeping them as separate tokens in the LLM. The results show performance improvements using multi-view features and keeping them as separate tokens, indicating that comprehensive object representation is crucial for optimal results.

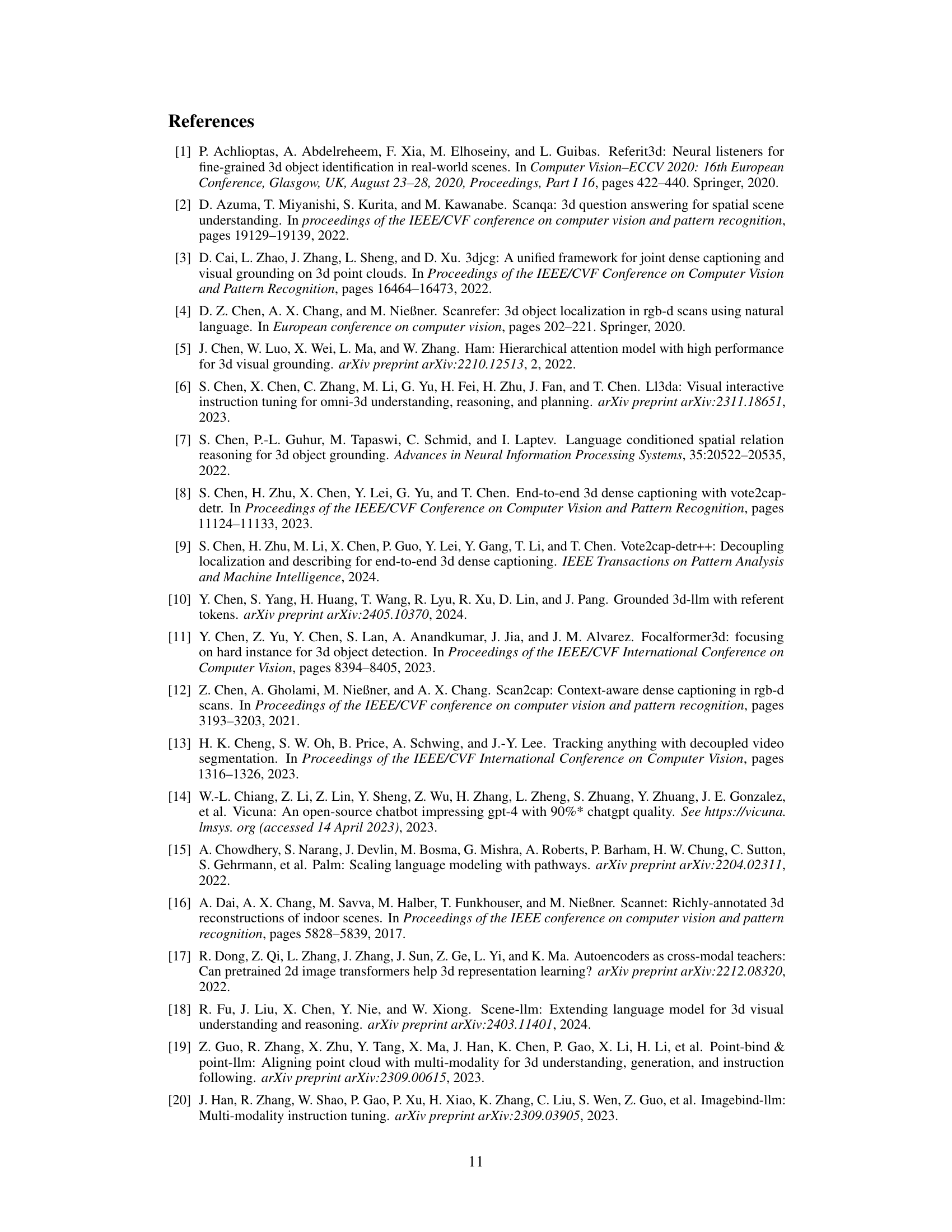

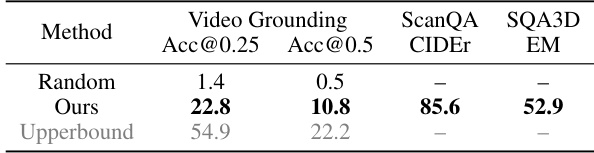

This table presents the quantitative results of experiments using video input. The model’s performance is evaluated on video grounding using Acc@0.25 and Acc@0.5, and on visual question answering tasks using CIDEr for ScanQA and EM for SQA3D. An upper bound is also provided for the video grounding task, showing the potential performance if the video object masks were perfect.

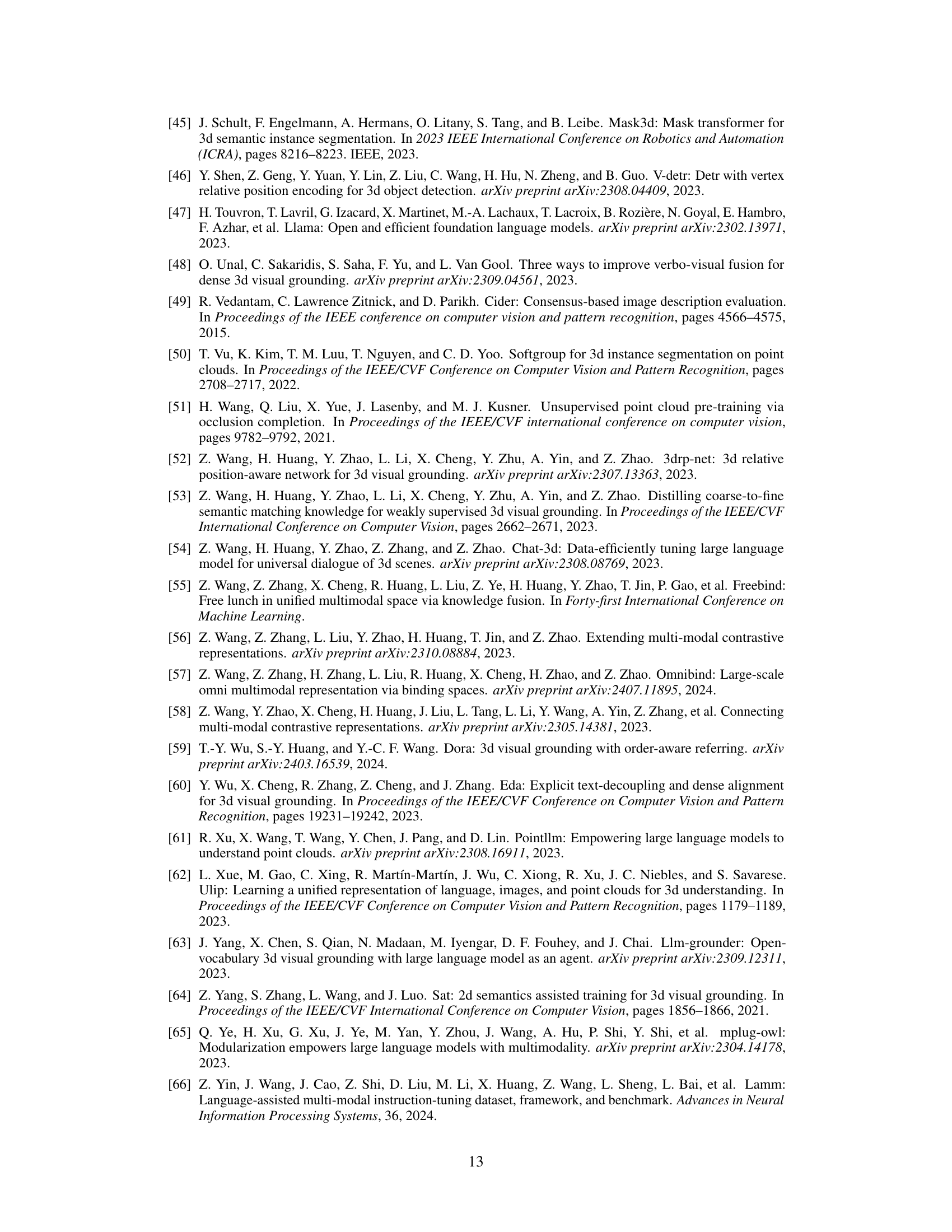

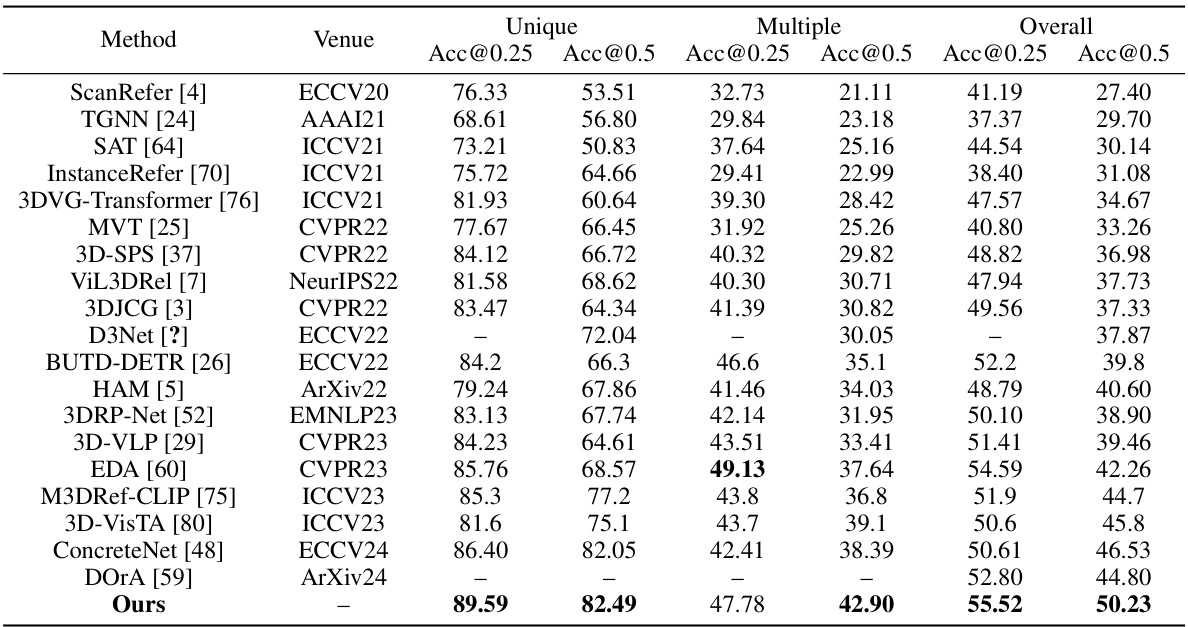

This table presents a performance comparison of different methods on the ScanRefer benchmark’s validation set. It breaks down the results into three categories: Unique (referencing a single object), Multiple (referencing multiple objects), and Overall accuracy. The table shows the accuracy at two different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds (0.25 and 0.5) for each category. This allows for a detailed comparison of the various models’ performance across different referencing scenarios.

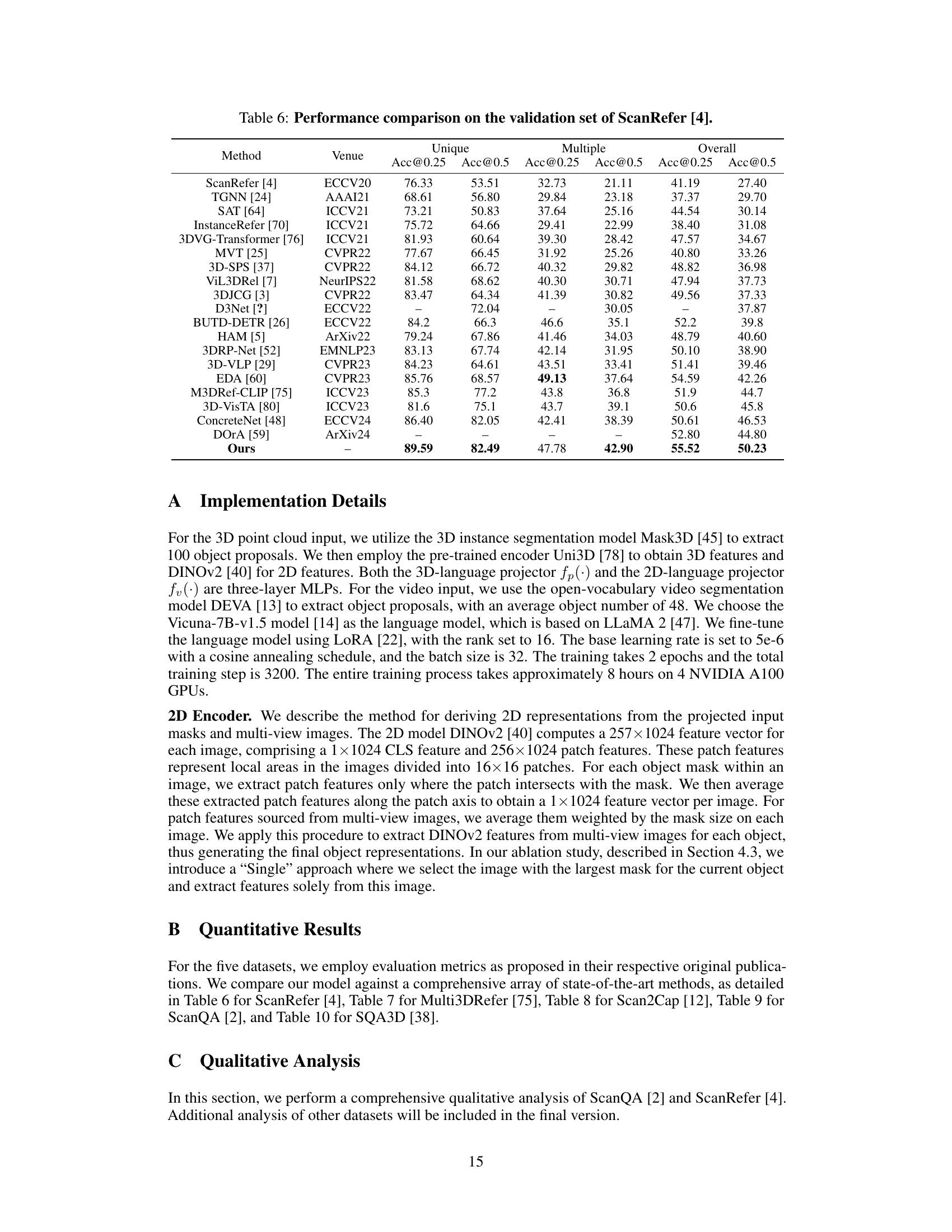

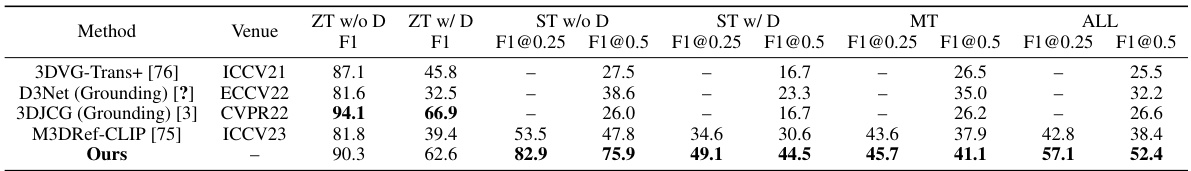

This table compares the performance of different methods on the Multi3DRefer dataset. It shows the F1 scores at IoU thresholds of 0.25 and 0.5 for various scenarios: ZT (Zero-shot Transfer), ST (Semi-supervised Training), MT (Multi-task), and ALL (all tasks). The results show how well each method performs on multi-object visual grounding.

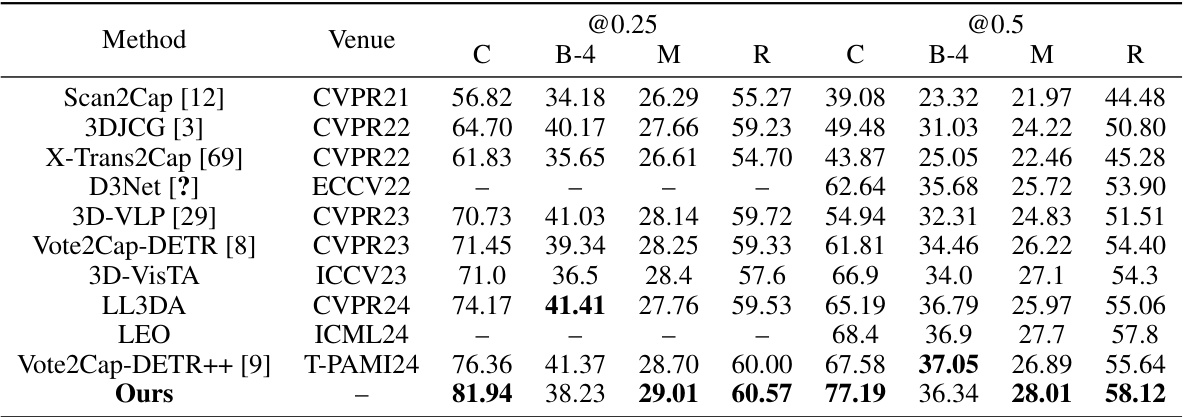

This table compares the performance of different methods on the Scan2Cap benchmark dataset. The metrics used for comparison are CIDEr, BLEU-4, METEOR, and ROUGE-L. The table shows the results for both unique and multiple object grounding tasks. The results suggest that the proposed method outperforms the existing state-of-the-art methods on this benchmark.

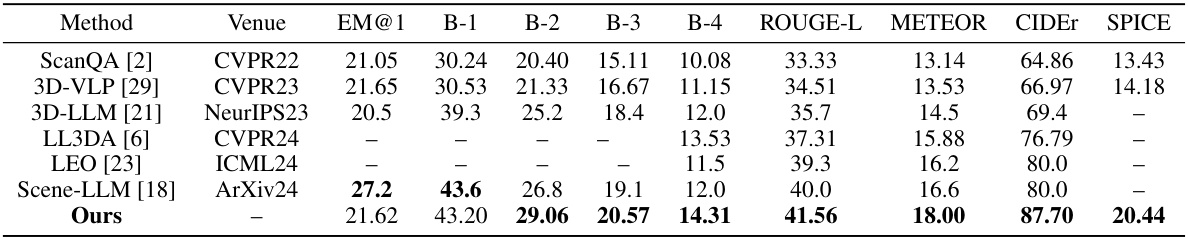

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different methods on the ScanQA dataset for visual question answering. The metrics used for evaluation include Exact Match (EM@1), BLEU scores (B-1, B-2, B-3, B-4), ROUGE-L, METEOR, CIDEr, and SPICE. The table shows that the proposed ‘Ours’ method outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods across multiple metrics, demonstrating improved performance in 3D visual question answering.

This table compares the performance of different methods on the SQA3D benchmark dataset. The benchmark focuses on visual question answering in 3D scenes and is broken down into different question types (What, Is, How, Can, Which, Others). The ‘Avg.’ column provides the average performance across all question types. The table shows that the proposed ‘Ours’ method outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods on this benchmark.

This table compares the performance of different models on five 3D scene understanding benchmarks: ScanRefer, Multi3DRefer, Scan2Cap, ScanQA, and SQA3D. It contrasts the performance of expert models (designed for specific tasks) and LLM-based models (designed for more general instructions). The table shows that the proposed Chat-Scene model outperforms prior state-of-the-art models on most benchmarks.

Full paper#