↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) are powerful but often generate inaccurate or unreliable information, a significant issue hindering their practical applications. Current methods to address this often involve costly techniques, such as fine-tuning with external knowledge bases or extensive retraining. This is both time and resource-intensive, limiting their widespread use.

This research paper introduces Self Logits Evolution Decoding (SLED), a novel decoding method that significantly enhances LLM factuality. SLED cleverly leverages the LLM’s inherent knowledge by comparing the output logits from the final layer with those from earlier layers, effectively using this internal knowledge for self-correction. The method’s strength lies in its efficiency and flexibility: it doesn’t require external data or fine-tuning, and it seamlessly integrates with other existing techniques. Extensive experiments across diverse LLMs and tasks demonstrate consistent improvements in factuality with minimal latency overhead.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on large language models (LLMs) because it introduces a novel decoding method that significantly improves factuality without requiring external knowledge bases or further fine-tuning. This addresses a major challenge in the field and opens new avenues for improving LLM reliability and trustworthiness. The flexible nature of the proposed method, allowing for combination with other techniques, further broadens its potential impact. The findings are significant for advancing the state-of-the-art in LLM factuality and generating more reliable and trustworthy outputs.

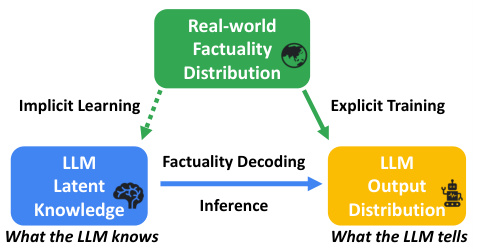

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the overview of factuality decoding. The left side shows implicit learning where the LLM acquires latent knowledge (what the LLM knows) from training data. This latent knowledge is then leveraged during inference through factuality decoding, which aims to align the LLM’s output distribution (what the LLM tells) with the real-world factuality distribution. The right side highlights the explicit training process where the LLM is explicitly trained on real-world factuality, resulting in an output distribution optimized to reflect factual correctness. The dotted lines show that the real-world distribution is only indirectly incorporated through the LLM’s implicit learning.

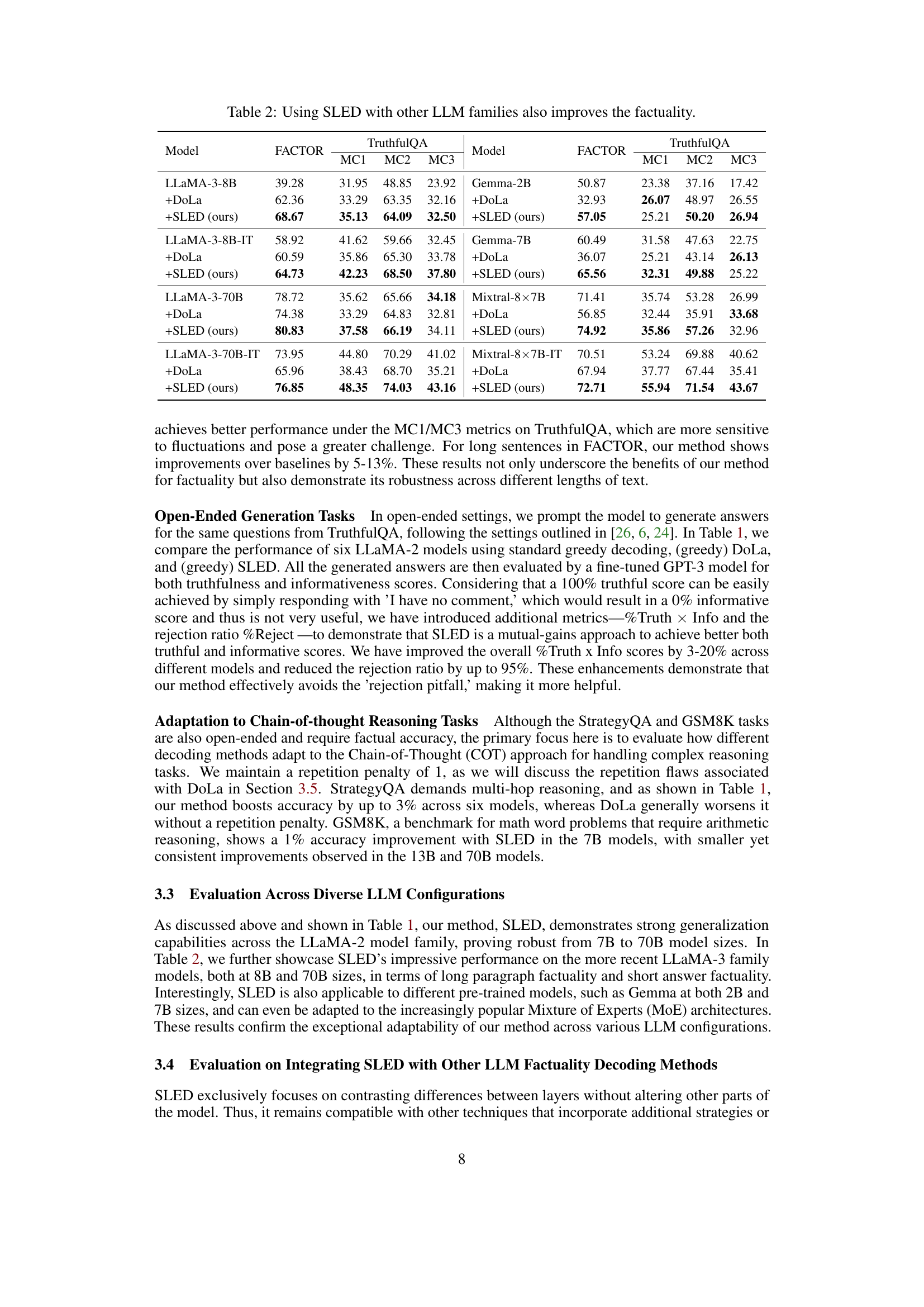

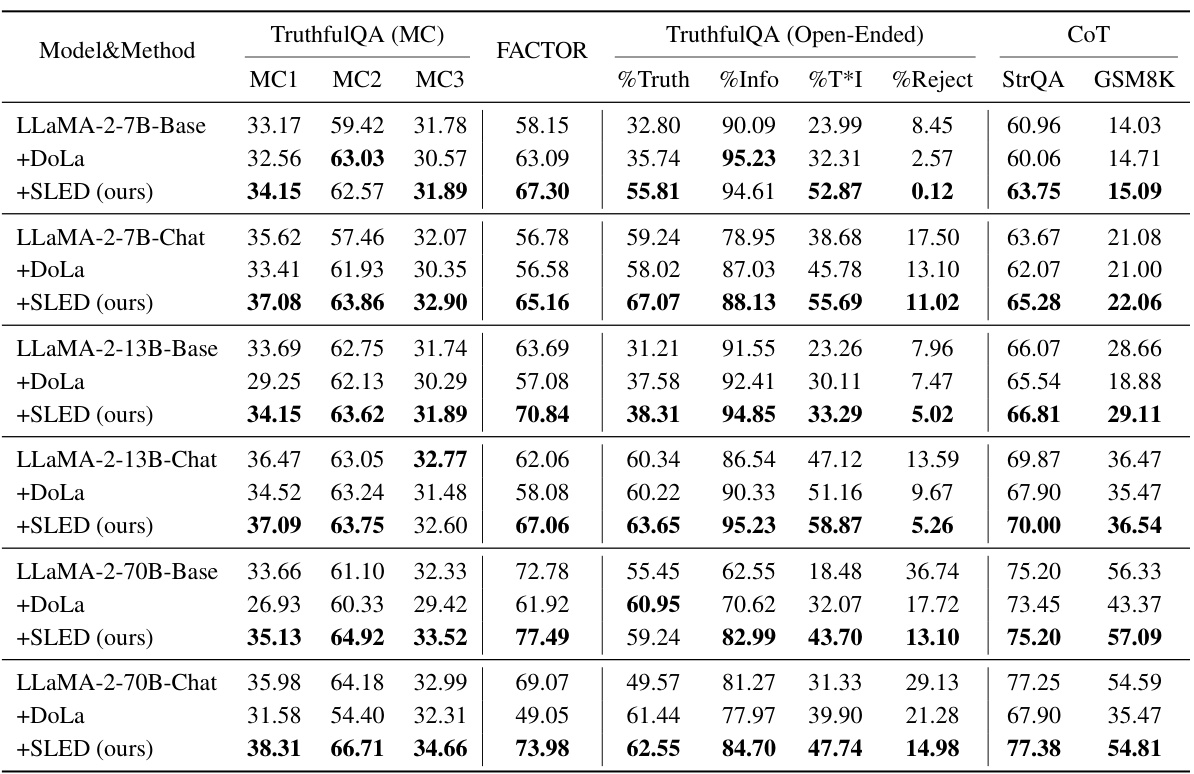

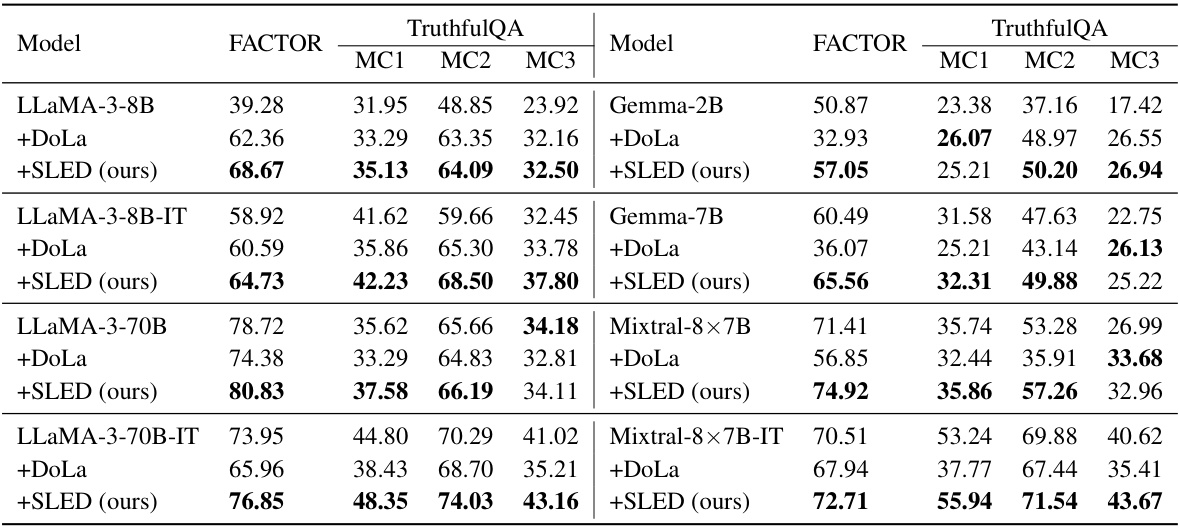

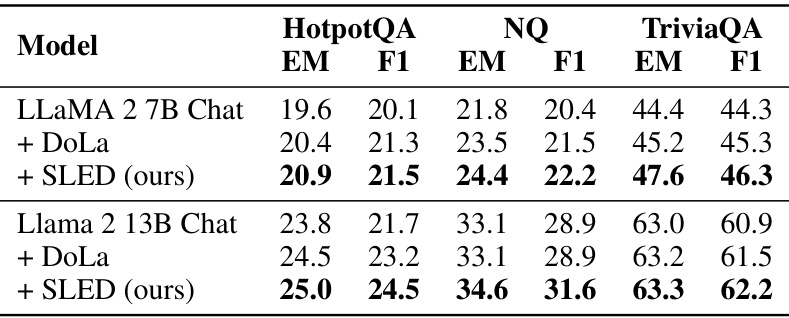

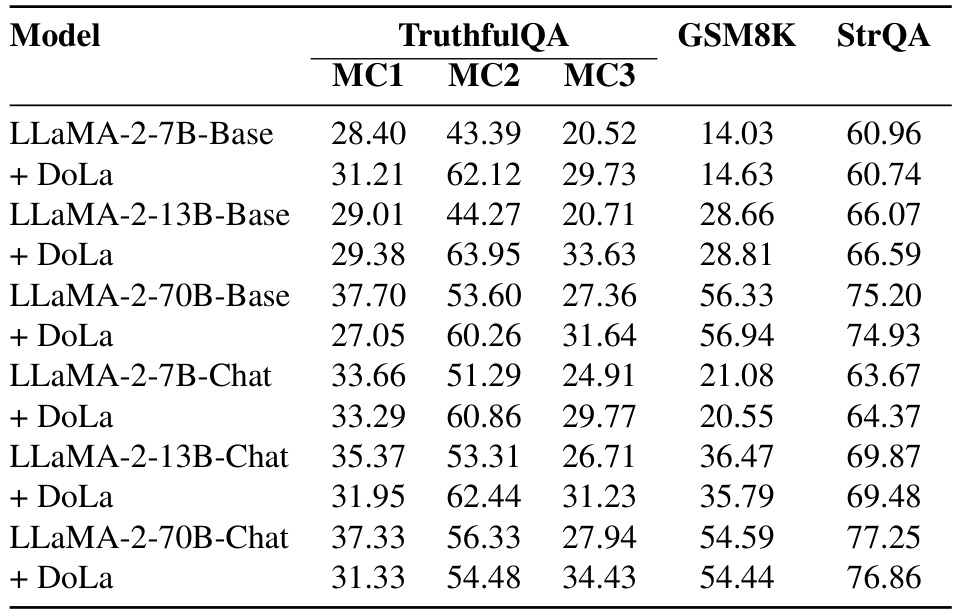

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three decoding methods (greedy decoding, DoLa, and SLED) on several benchmark datasets using three different sizes of LLaMA 2 models. The metrics used include accuracy on multiple-choice questions (MC1, MC2, MC3), accuracy on a factual accuracy dataset (FACTOR), and metrics measuring truthfulness, informativeness, rejection rate, and accuracy on various open-ended generation tasks (TruthfulQA, StrategyQA, and GSM8K). The results show that SLED consistently outperforms both greedy decoding and DoLa across multiple metrics and datasets.

In-depth insights#

LLM Factuality Issue#

Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities but suffer from a significant factuality issue. Hallucinations, where the model generates factually incorrect information, are a major concern, undermining trust and reliability. This problem stems from the way LLMs are trained; they learn statistical relationships in data rather than true factual knowledge. Consequently, they may confidently assert false statements. Addressing this requires moving beyond simple statistical associations and incorporating methods that enhance factual accuracy during the decoding process. This could involve leveraging external knowledge bases, refining decoding strategies, or using techniques to contrast and refine internal model representations to better align output with reality. The challenge lies in finding methods that are both effective and computationally efficient, maintaining the fluency and speed of LLM generation. Solutions may involve a combination of approaches, as there is no single perfect fix for the complex nature of this issue.

SLED Framework#

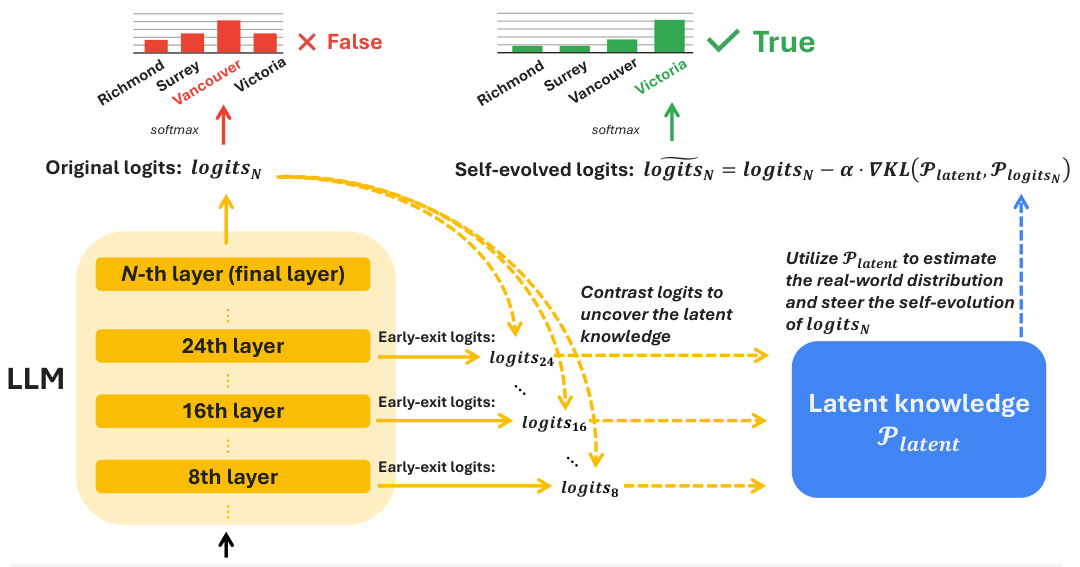

The Self Logits Evolution Decoding (SLED) framework offers a novel approach to enhancing the factuality of Large Language Models (LLMs) by leveraging their internal knowledge. It contrasts output logits from the final layer with those from earlier layers, identifying discrepancies that indicate factual inaccuracies. This comparison is used to guide a self-refinement process, improving factual correctness without requiring external knowledge bases or further fine-tuning. SLED’s approximate gradient approach enables the latent knowledge embedded within the LLM to directly influence output refinement. The framework’s flexibility allows for integration with other decoding methods, potentially further enhancing their performance. Key to SLED’s success is its ability to harness the implicit knowledge learned during LLM training, which is often underutilized in standard decoding methods. Experimentation across diverse model families and scales demonstrates consistent factual accuracy improvements, highlighting the efficacy and broad applicability of this innovative approach.

Layer-wise Contrast#

Layer-wise contrast, in the context of large language models (LLMs), is a technique that leverages the inherent information progression across different layers of the model’s architecture. Early layers often capture basic linguistic features, while later layers integrate contextual information and higher-level semantic understanding. By comparing the output representations (logits) from various layers, we can discern how factual information evolves and potentially identify discrepancies between early intuitions and final predictions. This approach is valuable because it provides insights into the model’s internal reasoning processes, revealing when and why factual inaccuracies might emerge. Furthermore, a layer-wise contrast approach can inform the design of novel decoding strategies. For example, it could guide the selective integration of early layer information to refine the final output, enhancing factual accuracy while maintaining fluency. The methodology can be used to identify layers that contribute most significantly to factual correctness or error which can then be used for designing better decoding methods.

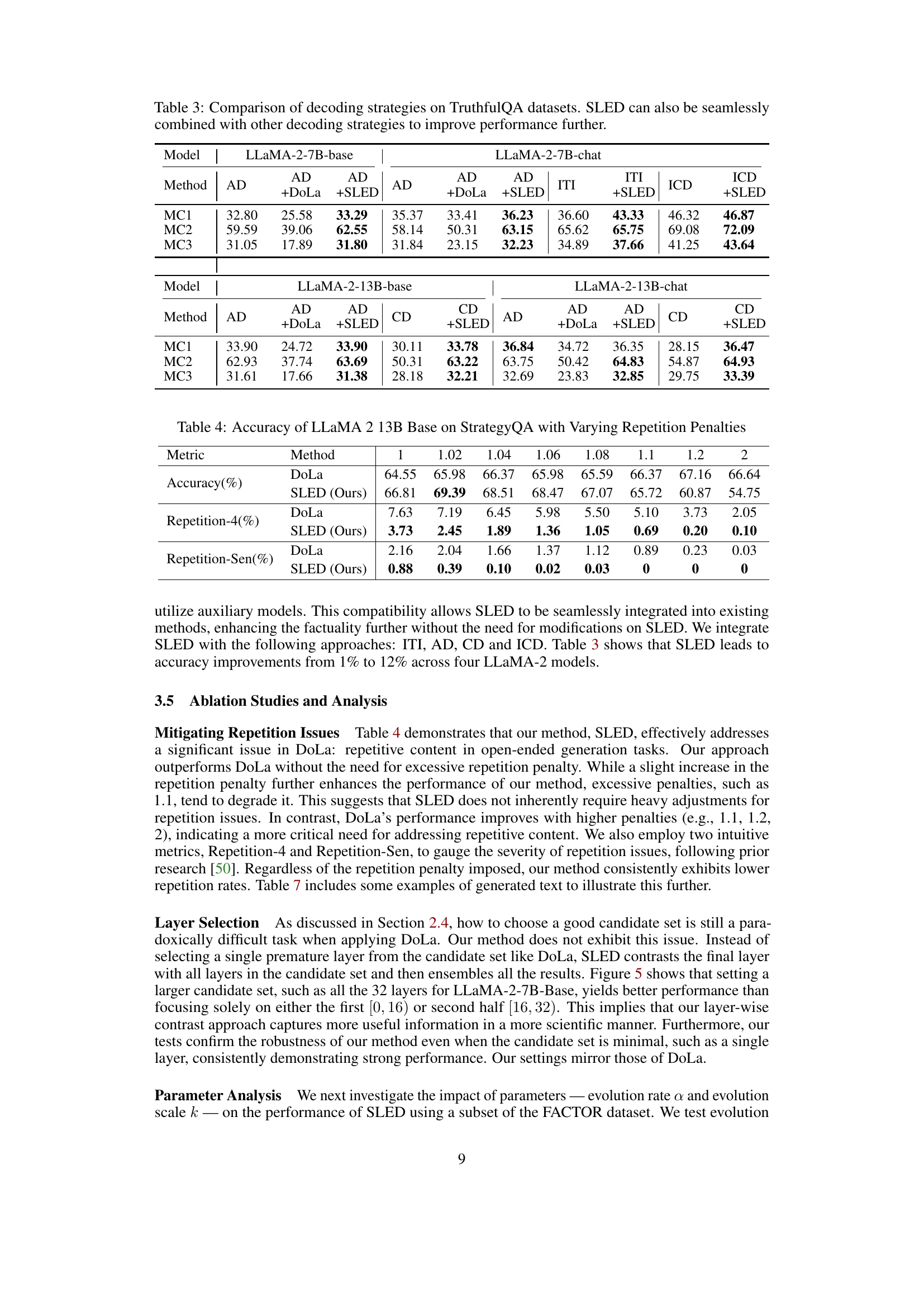

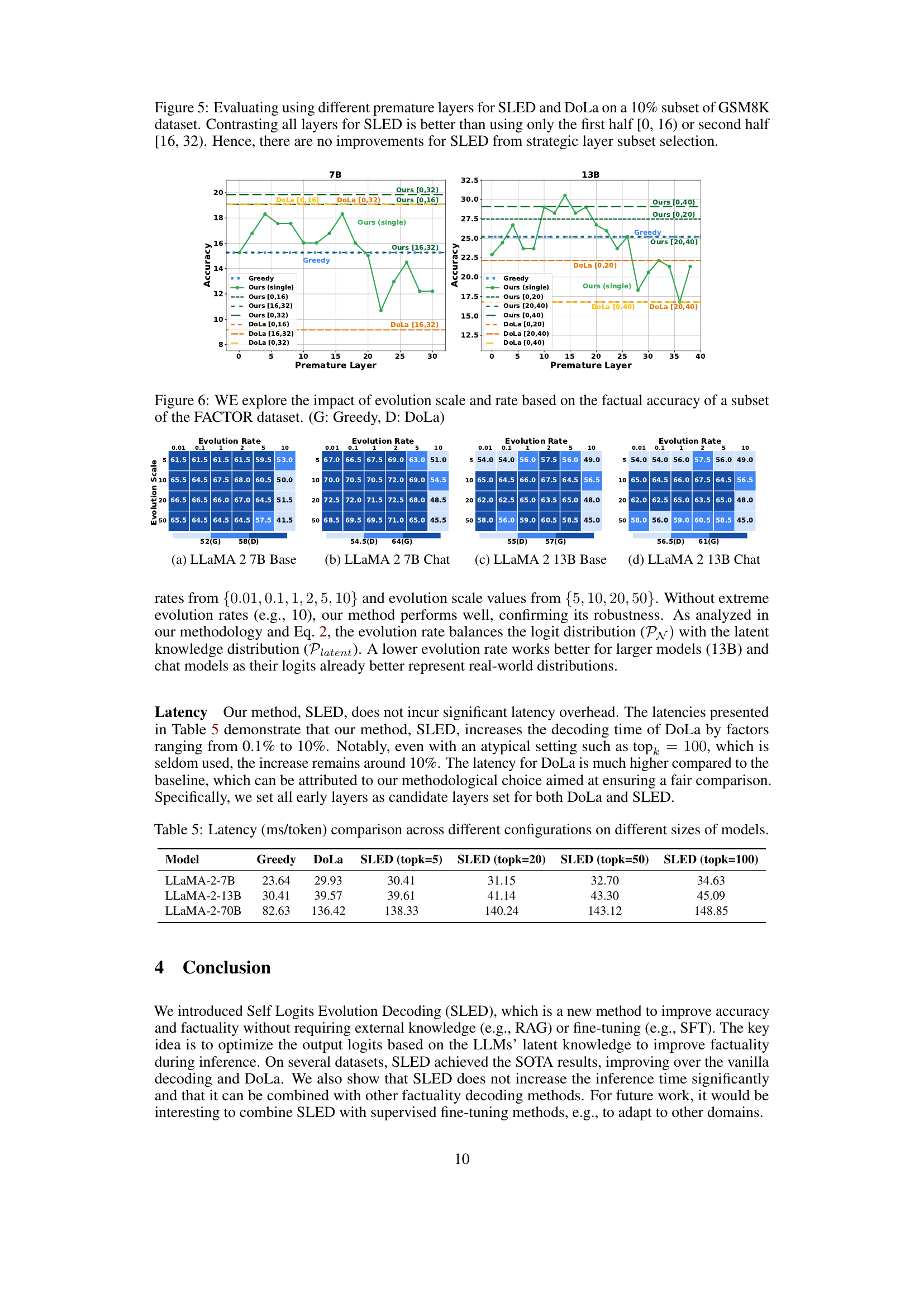

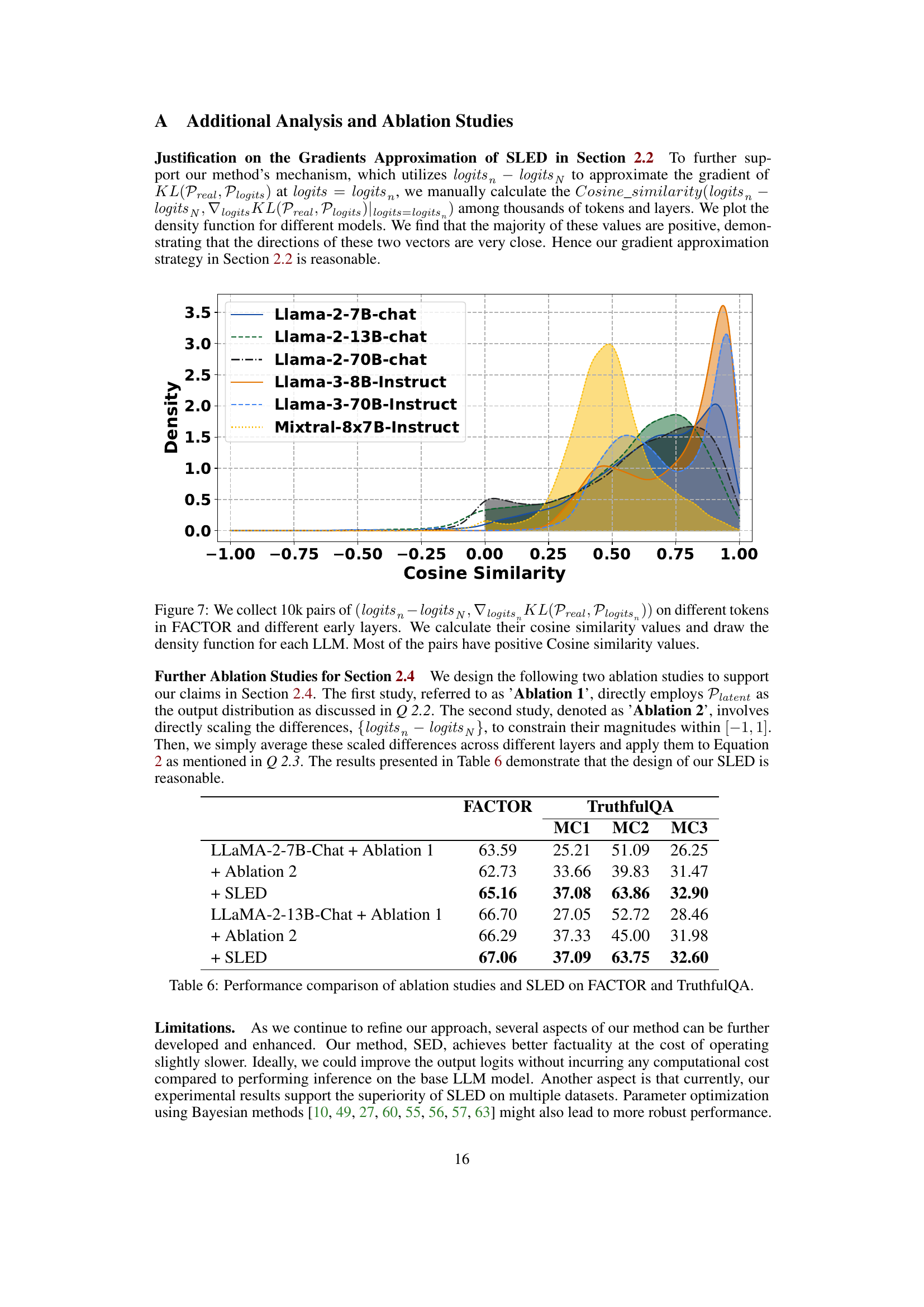

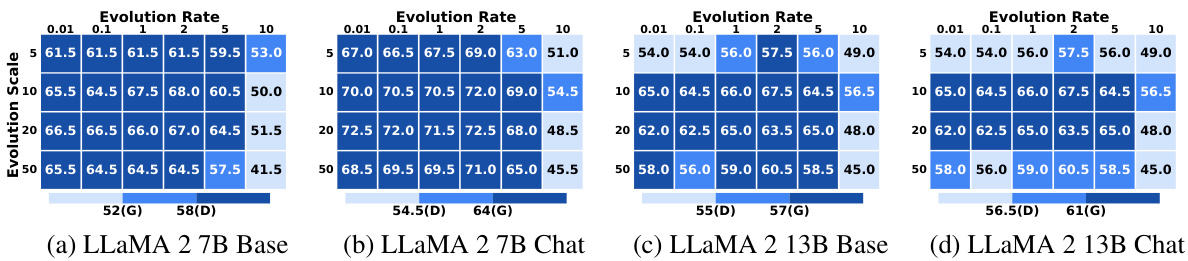

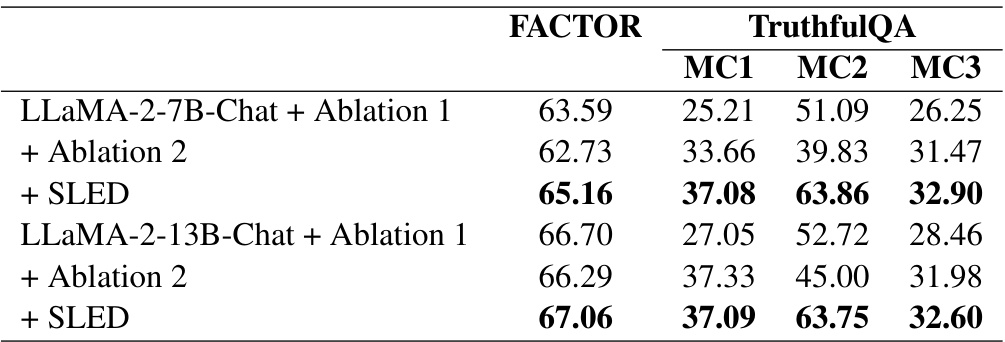

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove or modify components of a model to understand their individual contributions. In this context, the authors likely performed ablation studies on their Self Logits Evolution Decoding (SLED) method to understand the impact of various components on the model’s performance. This might involve removing or altering the early layer comparison, changing the ensemble method for latent knowledge estimation, altering the evolution rate, or adjusting the evolution scale. The results of these experiments would help isolate the importance of specific elements of the SLED approach and validate the proposed design choices. For instance, they could demonstrate that contrasting with early layers is crucial, or that a particular ensemble method for combining the knowledge from different layers outperforms alternatives. Furthermore, an analysis of the impact of the evolution rate and scale parameters is vital to ensure the method is robust and not overly sensitive to hyperparameter tuning. By carefully analyzing these results, the authors strengthen the validity of their method, demonstrating its effectiveness and the significance of its individual elements. Such studies help in isolating the contributions of different parts of the proposed methodology which provides valuable insights into the model’s workings and aids in refining future improvements.

Future of SLED#

The future of Self Logits Evolution Decoding (SLED) looks promising. Improved gradient approximation techniques could lead to more accurate estimations of the real-world factuality distribution, enhancing SLED’s effectiveness. Exploring different ways to combine SLED with other decoding methods and exploring other architectural configurations (beyond MoE) would further advance its capabilities. Integrating SLED into the training process rather than solely using it for inference is another avenue of exploration. This could potentially lead to models that are inherently more factual from the outset. Finally, research into quantifying the latent knowledge within LLMs could provide a deeper understanding of how SLED functions and lead to the development of even more sophisticated factual decoding methods. Addressing the limitations of current gradient approximations and exploring alternative optimization strategies would also be beneficial. The development of a more robust and interpretable framework would make SLED a more accessible and useful tool for improving factuality in LLMs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

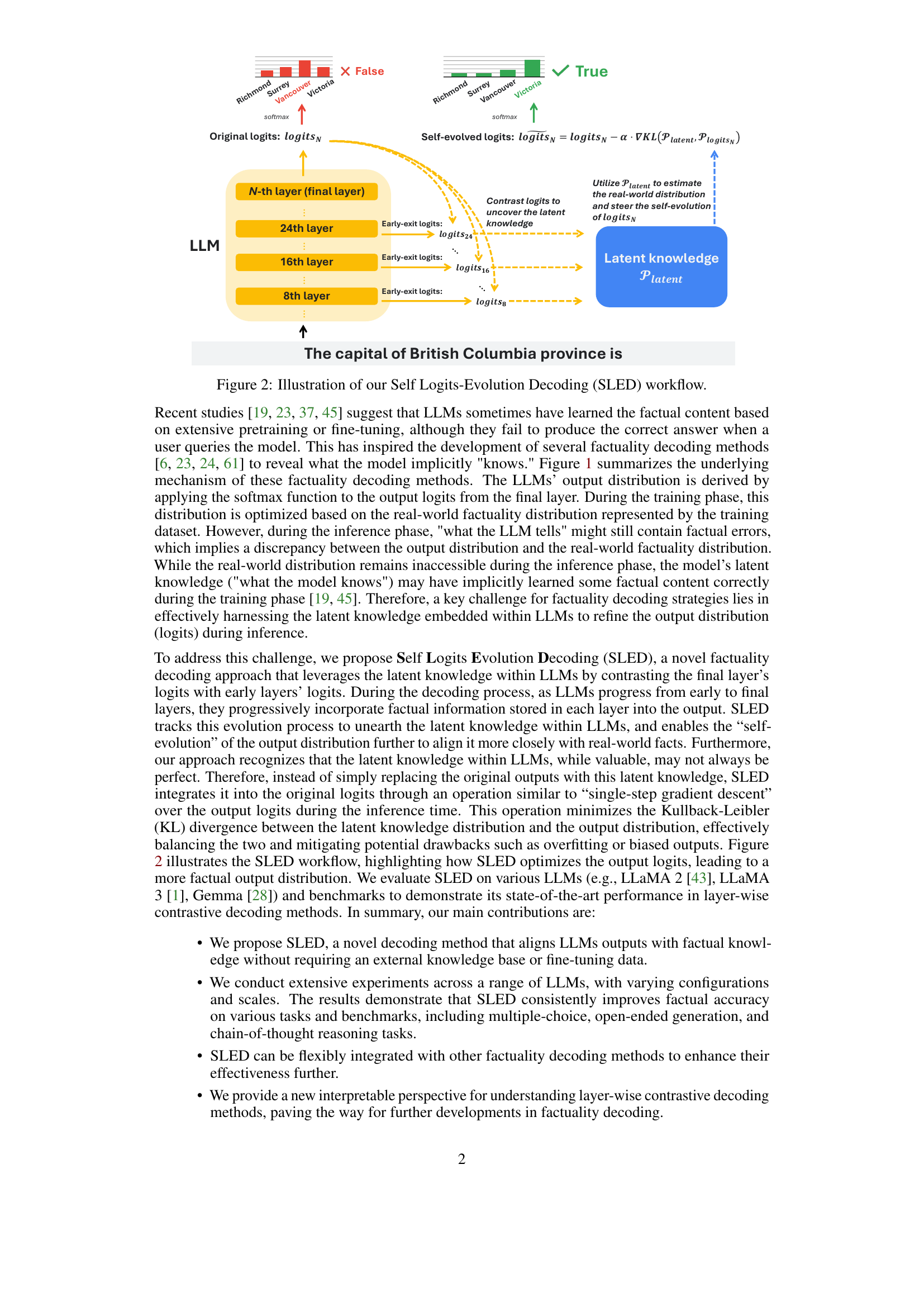

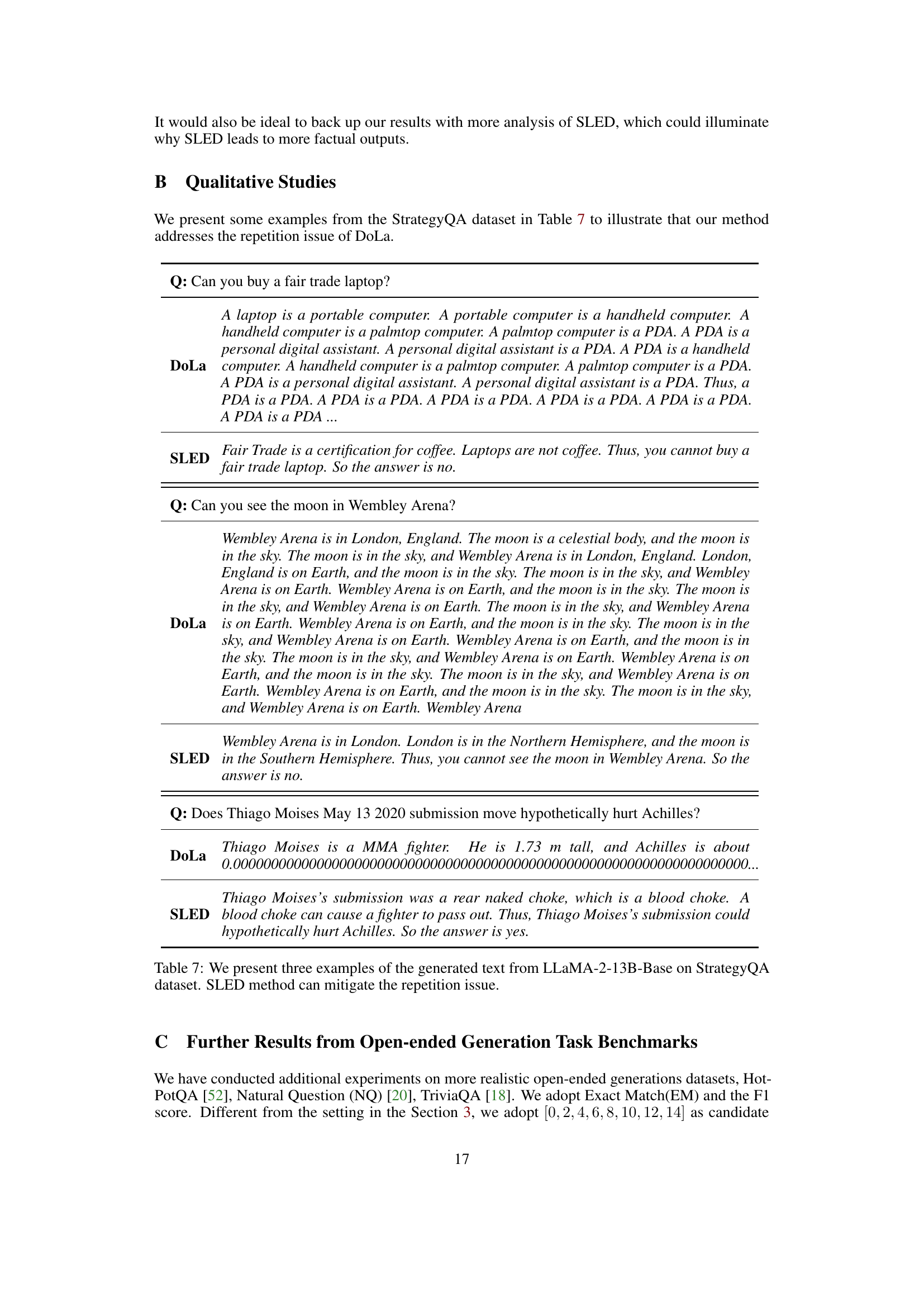

This figure illustrates the Self Logits Evolution Decoding (SLED) workflow. The process starts by contrasting the output logits from the final layer of an LLM with those from earlier layers (8th, 16th, and 24th layers shown). This comparison helps uncover the latent knowledge within the LLM. A latent knowledge distribution (Platent) is then estimated, which represents the model’s implicit understanding of the real-world factuality distribution. Finally, this latent knowledge is used to refine the final layer’s logits through a self-evolution process, aiming to align the model’s output distribution more closely with real-world facts, resulting in improved factual accuracy.

This figure shows the KL divergence between the logits distribution of each layer and the real-world factuality distribution for three different sizes of LLaMA-2 base models. The x-axis represents the layer index, and the y-axis represents the KL divergence. The results show that the KL divergence decreases as the layer index increases, indicating that the final layer’s logits distribution is closer to the real-world distribution than those of the early layers.

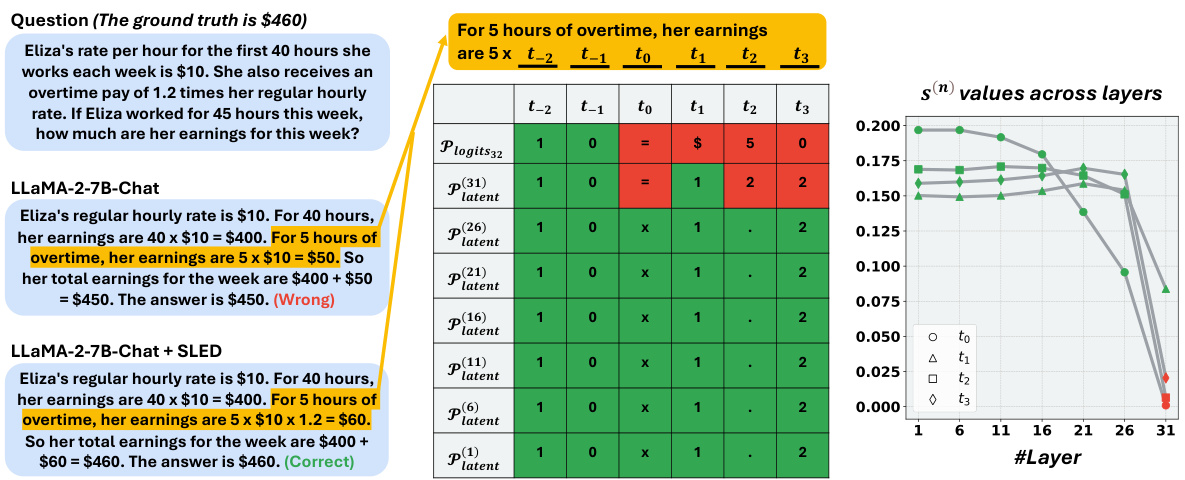

This figure shows an example of how SLED works using the GSM8K dataset. It illustrates the core concept of SLED: contrasting the logits (predicted probabilities) from the final layer of the LLM with those from earlier layers to identify and correct factual errors. The figure highlights how SLED assigns weights to the probability distributions from each layer, giving higher weights to layers where the prediction is more accurate (closer to the ground truth) and lower weights to layers with inaccurate predictions, effectively guiding the model towards a more factual output. The example shows how this process leads to the correct answer.

This figure displays the KL divergence between the logits distribution of each layer and the real-world distribution for three different sized LLAMA-2 models. The results show that the KL divergence is consistently lower for the final layer than for any of the earlier layers, indicating that the final layer’s logits distribution is a better approximation of the real-world distribution.

This figure shows the KL divergence between the logits distribution of each layer in three different sized LLAMA-2 base models and the real-world distribution. The x-axis represents the layer index, and the y-axis shows the KL divergence. The results demonstrate that as the model processes through more layers (moving towards the final layer), the output logits distribution increasingly aligns with the real-world factuality distribution. This suggests the model progressively incorporates factual knowledge stored within its layers during decoding.

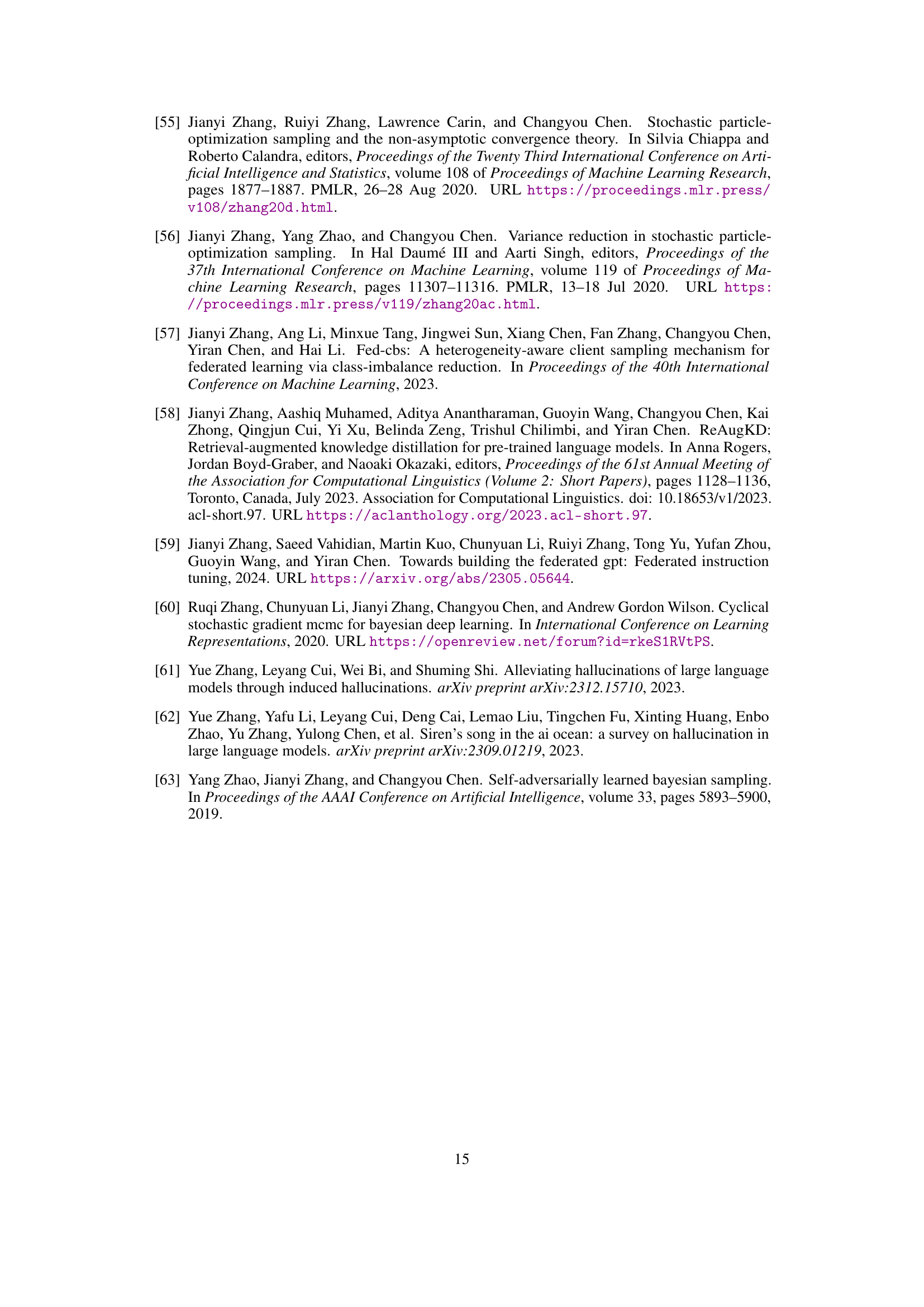

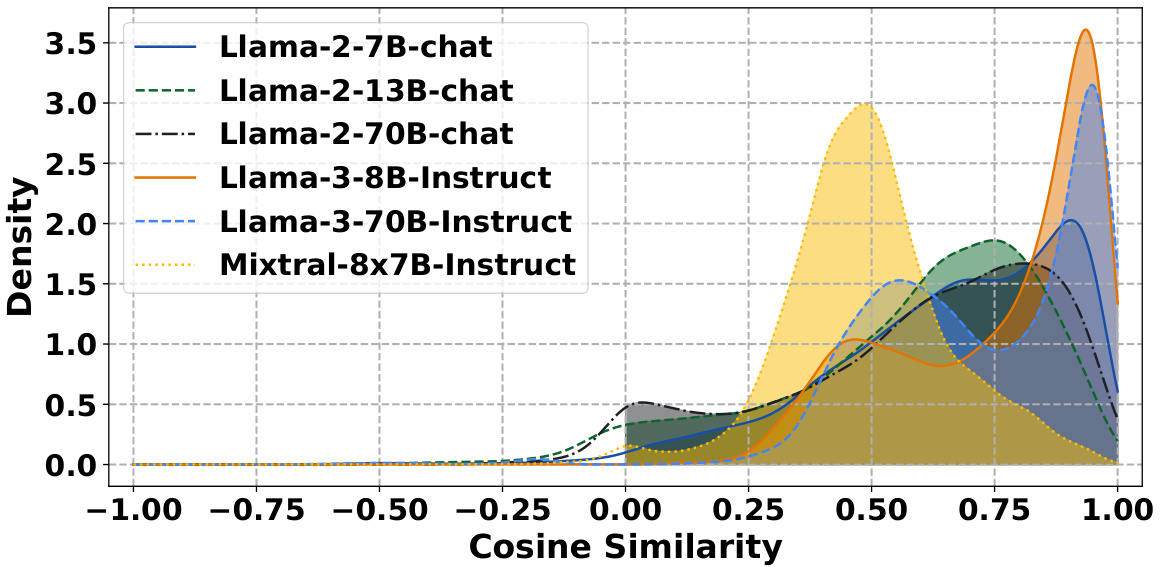

This figure shows the distribution of cosine similarity between the difference of early layer logits and final layer logits (logitsn - logitsN) and the gradient of KL divergence between the real-world distribution and the output distribution at early layer logits (∇logitsnKL(Preal, Plogitsn)). A positive cosine similarity indicates that the direction of logitsn - logitsN approximates the gradient, supporting the paper’s claim that this difference can be used to estimate the gradient during the self-logits evolution process.

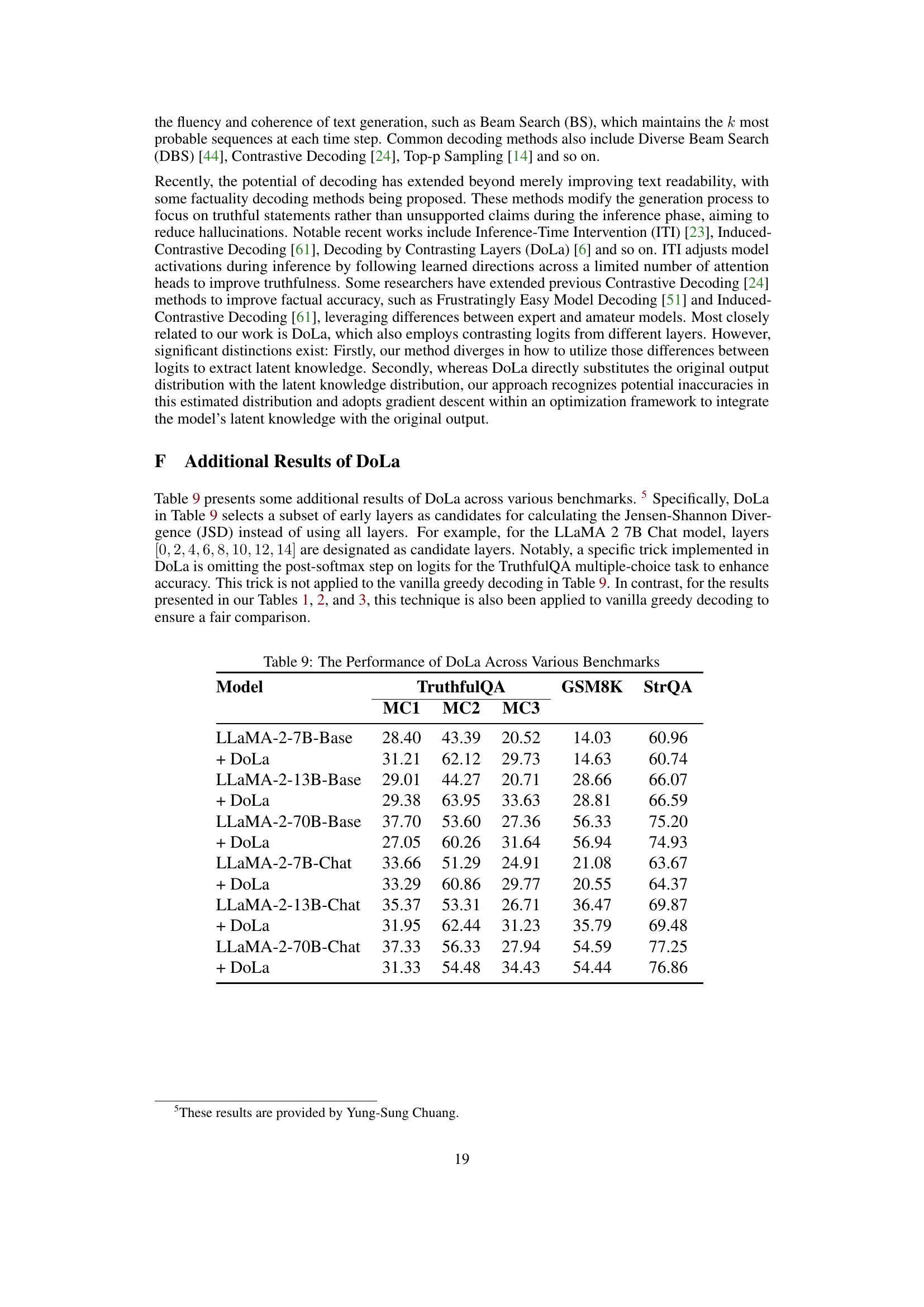

More on tables

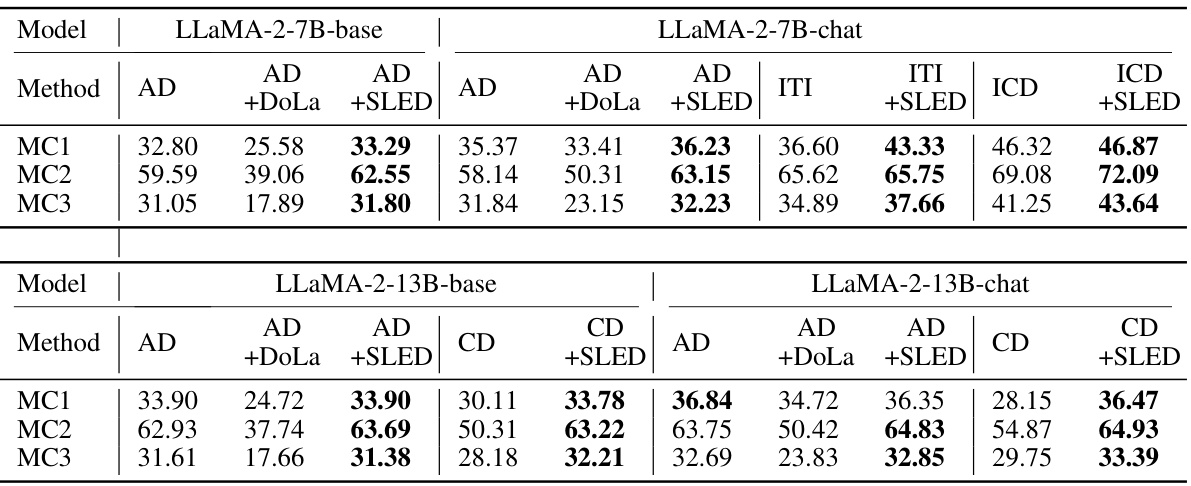

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of SLED, DoLa, and vanilla greedy decoding on various datasets and metrics using the LLaMA 2 model family. It shows the accuracy in multiple-choice questions (MC1, MC2, MC3) for the FACTOR dataset, and various metrics (%Truth, %Info, %T*I, %Reject) for the TruthfulQA dataset. The best results for each metric are highlighted in bold, demonstrating SLED’s superior performance compared to the baselines.

This table presents a comparison of different decoding methods (greedy decoding, DoLa, and SLED) on various metrics across three different sizes of LLaMA 2 models (7B, 13B, and 70B). Each model is tested on several datasets (FACTOR, TruthfulQA (MC), TruthfulQA (Open-Ended), StrategyQA, GSM8K) using multiple metrics (accuracy, truthfulness, information, rejection). The table demonstrates that SLED consistently outperforms both DoLa and the baseline greedy decoding method across most datasets and metrics.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three decoding methods (greedy decoding, DoLa, and SLED) on various tasks and metrics using different sizes of LLaMA 2 models. The metrics evaluated include accuracy on multiple-choice questions (MC) across three different datasets (FACTOR, MC1, MC2, MC3), percentage of truthful and informative answers, rejection rate, and accuracy on open-ended question answering and chain-of-thought tasks across datasets like StrategyQA and GSM8K. The table highlights the superior performance of SLED compared to both DoLa and the standard greedy approach.

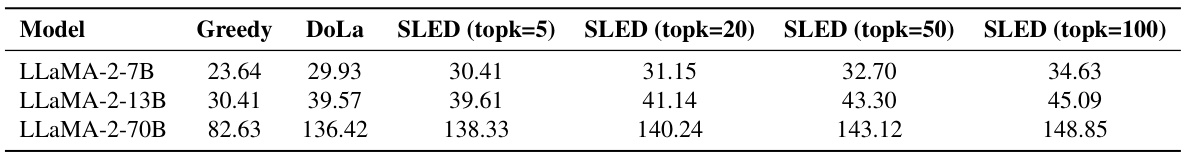

This table presents the latency in milliseconds per token for various model sizes (LLaMA-2-7B, LLaMA-2-13B, LLaMA-2-70B) under different decoding methods. It compares the latency of greedy decoding, DoLa, and SLED with varying evolution scales (topk). The results show the added latency overhead of different decoding methods and different evolution scales.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three decoding methods (greedy decoding, DoLa, and SLED) on the LLaMA 2 model family across multiple datasets and metrics. The datasets used include FACTOR, TruthfulQA (for both multiple-choice and open-ended questions), and Chain-of-Thought (COT) reasoning tasks (StrategyQA and GSM8K). The metrics evaluated include accuracy (%Truth, %Info, %T*I, %Reject) and rejection rate. The table highlights that SLED consistently outperforms DoLa and greedy decoding across various models and evaluation criteria, demonstrating its effectiveness in enhancing factual accuracy.

This table presents a comparison of different decoding methods (greedy, DoLa, and SLED) on various metrics across three sizes of LLaMA 2 models (7B, 13B, and 70B), both base and chat versions. The metrics used include accuracy on multiple choice question tasks (FACTOR, TruthfulQA) and performance on open-ended generation tasks (TruthfulQA, StrategyQA, GSM8K), considering aspects like truthfulness, information, and rejection rate. The results demonstrate that SLED consistently outperforms DoLa and the greedy decoding baseline, highlighting its effectiveness in improving the factuality of LLMs.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of three decoding methods (greedy decoding, DoLa, and SLED) on various metrics across three different sizes of LLaMA 2 models. The metrics evaluated include accuracy on multiple-choice questions (MC1, MC2, MC3) and the percentage of truthful, informative, and truthful-and-informative answers on open-ended questions. The table also includes rejection rate and various other metrics on different datasets (FACTOR, TruthfulQA, StrategyQA, GSM8K). The results demonstrate that SLED consistently outperforms both DoLa and greedy decoding across most metrics and datasets.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of three decoding methods (greedy decoding, DoLa, and SLED) on various tasks using three sizes of LLaMA 2 models. The tasks assess factuality using metrics such as accuracy, information content, and rejection rate across benchmarks like TruthfulQA (multiple choice and open-ended), FACTOR, StrQA, and GSM8K. The bolded numbers highlight the best performance achieved for each metric and benchmark.

Full paper#